[This post, created on December 1, 2020, has been updated: Lots of new stuff here. Specifically, the post now includes: 1) An area map that provides a more accurate and clearer representation of the nature of the 55th Fighter Group’s encounter with the Luftwaffe on November 29, 1943, and 2) New biographical information about Lieutenants Albino, Garvin, and Gilbride, 3) New Oogle maps that more accurately pinpoint the locations where Lieutenants Carroll, Garvin, and Gilbride were lost. Specific information about Lt. Garvin’s is from his IDPF, which I recently received from the U.S. Army Human Resources Command. Where necessary, many parts of this post have been corrected, updated, clarified, and otherwise fixified.

This post is really, really (did I say really?) long. Scroll on down for a look…!]

Part VIII: A Postwar Search: The Missing of November

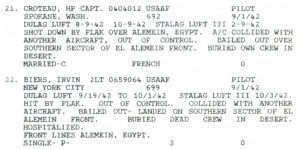

Seven 8th Air Force P-38s were lost on the mission of November 29. These aircraft were piloted by Lieutenants Albino, Carroll, Gavrin, Gilbride, Hascall, Suiter, and, Major Joel.

Information about the fates of Lieutenants Garvin, Gilbride, and Hascall probably reached their families by the end of 1944, if not months earlier. Lieutenants Carroll and Suiter, who survived their “shoot-downs” to be captured, spent the remainder of the war as POWs at Stalag Luft I, in Barth, Germany. And, at least for official purposes, the deaths of Lieutenant Albino and Major Joel were confirmed in the context of Public Law 490.

The fate of these lost pilots is described in detail below, based on information in Missing Air Crew Reports, and to an equal if not greater extent, from the following sources:

12 O’Clock High Forum (Index Item 45307)

Studiegroep Luchtoorlog 1939-1945 (SGLO)

Aircrew Remembered Kracker Luftwaffe Archive (Luftwaffe Victories by Name and Date for November 29, 1943)

Station 131

ZZ Air War

…these two (no longer accessible…?) links…

Army Air Forces Forum (Message 92115)

P088 EZBoard

…and various other websites, like FindAGrave.com…

…plus (for Lieutenant Carroll) Robert Littlefield’s book Double Nickel, Double Trouble.

Lastly and most importantly, some of these accounts include information from Luftgaukommando Reports, and (for Lieutenants Albino, Garvin, and Gilbride, as well as Major Joel) documents in their Individual Deceased Personnel Files. (I received a copy of Lieutenant Garvin’s IDPF from the Army a couple of weeks ago.)

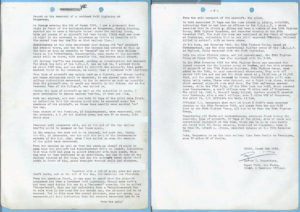

First, once again for reference, is my revised Oogle Map of the area where the 55th Fighter Group’s encounter with the Luftwaffe took place. Updates to this map from its initial version include the following: 1) The crash locations of three Me-109G-6s of the Seventh Staffel of Jagdgeschwader 1, lost (directly or indirectly) as a result of III./JG 1’s engagement with the 55th Fighter Group’s Lightnings, 2) An adjustment to the easternmost “leg” of the 55th Fighter Group’s intended course into Germany (ironically, the 55th never entered Germany!), 3) The crash locations, as much as they can be pinpointed on this ultra-small-scale digital map, of 38th Fighter Squadron pilots Lieutenants Carroll and Gilbride, 4) The serial numbers of the lost P-38s and the three above-mentioned Me-109G-6s. Information about the three 7./JG 1 losses, and the crash locations of Lieutenants Carroll and Gilbride comes from Part 2 of Teunis Schuurman’s WW II – Research by PATS blog.]

Maps symbols and colors indicate the following:

Maps symbols and colors indicate the following:

Bright blue line extending west to east across the Netherlands to a point near the Dutch-German border indicates the approximate or intended course of the 55th Fighter Group for a rendezvous with 8th Air Force bombers.

Black triangle shows the approximate area where the Luftwaffe initially assumed it would intercept the 55th Fighter Group’s P-38s, as explained in the book Jagdgeschwader 1 und 11: Einsatz in der Reichsverteidigung von 1939 bis 1945 (Jagdgeschwader 1 and 11: Used in the Defense of the Reich from 1939 to 1945).

Blue ovals with names adjacent indicate the last reported or assumed location of P-38 losses, based on information in Missing Air Crew Reports.

Red ovals with names adjacent indicate the actual locations where the P-38s were lost. Notice that there’s no blue oval for Lt. Hascall, because his P-38 was last sighted over the North Sea, at a point “west” of (to the left of) this map view, and Lieutenant Garvin, Major Joel’s wingman, because he definitely crashed at Hondschoote, France (again, well “off the map”). More information will be presented about Lt. Garvin’s fate in subsequent posts.

The location of Major Joel’s loss remains unknown. Some sources suggest the crash location was Marken Island in the Markermeer, indicated by a yellow oval.

In subsequent posts, I’ll discuss why I believe this location is incorrect.

Black ovals with names adjacent indicate the loss locations of three Me-109G-6s of 7/JG 1. (More about this below.)

________________________________________

As I researched the events of this day, something soon became apparent: The disparity between the last reported locations of Lieutenants Albino, Carroll, and Suiter as described in the Missing Air Crew Reports, and the actual (general) locations where their aircraft crashed. Major Joel and Lieutenant Garvin were reported to have been lost in the same general location as those three lieutenants. Major Joel’s wingman is now known, with certainty, to have crashed in France. As for the Major himself? The most likely location of where the “flying wolf” fell to earth will be a topic of discussion in the next post.

Albino, Carroll, and Gilbride’s planes crashed approximately 65 miles west-southwest of their last reported position as reported in their MACRs (over Saterland, Germany), while Suiter’s aircraft was downed 43 miles west-southwest of his last sighting (northeast of Ter Apel, Netherlands).

These inconsistencies can be partly attributed to the intensity, speed, confusion, and stress of the engagement between the aircraft of JG 1 and the P-38s. But, I think the primary factor was the weather: As attested to in American and German records, the continent was completely overcast above 25,000 feet throughout this area, rendering it impossible for the American pilots to know their locations with a great degree of accuracy. The locations of the victory claims lby the German pilots, though not precisely corresponding to the specific locations of the lost P-38s, are more accurate, all being in the Netherlands, north and west of Hoogeveen.

________________________________________

To start, Lieutenants Garvin, Gilbride, and Hascall.

________________________________________

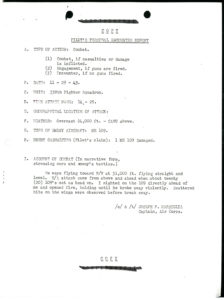

2 Lt. James Michael Garvin, P-38H 42-67046, MACR 1427

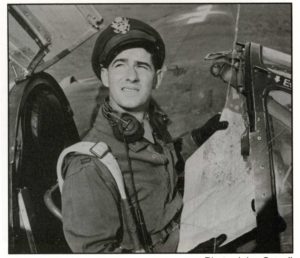

Photo of James M. Garvin from Double Nickel, Double Trouble

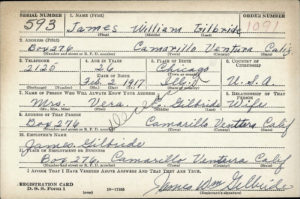

Here’s Lt. Garvin’s WW II Draft Registration Card. What is immediately apparent is Lieutenant Garvin’s age: Born in 1915, at the age of 28 he was even older than Major Joel, and likewise – probably – most of the pilots he served with.

Here’s Lt. Garvin’s WW II Draft Registration Card. What is immediately apparent is Lieutenant Garvin’s age: Born in 1915, at the age of 28 he was even older than Major Joel, and likewise – probably – most of the pilots he served with.

The “first” version of this post described my (then) uncertainty about what befell Lieutenant Garvin, specifically in terms of the location where his plane actually crashed. The MACR indicates that his last position – like that of Major Joel, and Lieutenants Albino and Carroll – was near Saterland, Germany, as shown in the “big” map above, while comments at the 12 O’Clock High Forum suggest a variety of other locations. As I originally wrote:

The “first” version of this post described my (then) uncertainty about what befell Lieutenant Garvin, specifically in terms of the location where his plane actually crashed. The MACR indicates that his last position – like that of Major Joel, and Lieutenants Albino and Carroll – was near Saterland, Germany, as shown in the “big” map above, while comments at the 12 O’Clock High Forum suggest a variety of other locations. As I originally wrote:

Though I have no definitive information thus far about Lt. Garvin’s crash site, some web references suggest that his plane fell to earth somewhere in the vicinity of the Leda Canal, east of the city of Leer, Germany. (That I seriously doubt.) But, in any event, here’s an Oogle map of the area east of Leer.

My skepticism about the Leda Canal being the area where Lt. Garvin crashed arises from English-language translations of the Luftgaukommando Report (AV 513/44) in which appears Lt. Garvin’s name. These documents suggest something very different: Lt. Garvin’s crash location is listed as Handschoote (Nord, France), which is nearly 200 miles southwest of the cities of Meppel and Hoogeveen, in Holland! If accurate, this would mean that after the engagement with Me-109s of III/JG1, Lt. Garvin managed to fly over 190 miles in the general direction of England. Would this have been possible? I don’t know. Well, Captain Franklin did suggest that as he and Lt. Gilbride came to the aid of the 38th Fighter Squadron, an unidentified 38th FS P-38 flew away from the other American fighters.

My skepticism about the Leda Canal being the area where Lt. Garvin crashed arises from English-language translations of the Luftgaukommando Report (AV 513/44) in which appears Lt. Garvin’s name. These documents suggest something very different: Lt. Garvin’s crash location is listed as Handschoote (Nord, France), which is nearly 200 miles southwest of the cities of Meppel and Hoogeveen, in Holland! If accurate, this would mean that after the engagement with Me-109s of III/JG1, Lt. Garvin managed to fly over 190 miles in the general direction of England. Would this have been possible? I don’t know. Well, Captain Franklin did suggest that as he and Lt. Gilbride came to the aid of the 38th Fighter Squadron, an unidentified 38th FS P-38 flew away from the other American fighters.

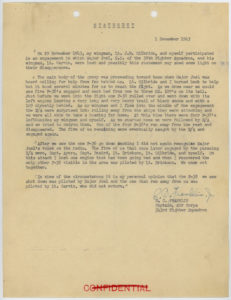

Note that the succession of documents list “Garvin’s” initials as “V.M.” and gives the cause of the crash as a “collision” (with what?), but gives no definitive answer to the International Red Cross’ request for verification of the identity of the missing pilot.

A check of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission database reveals that no Commonwealth airman with the surname “Garvin” was killed on this date. So, this “Garvin” must indeed be Lt. Garvin of the 38th Fighter Squadron. If and when I receive Lt. Garvin’s IDPF and resolve this puzzle, I hope to update this post.

And, here’s the update…

In early December, I was fortunate to have received from the U.S. Army Human Resources Command a digital copy of Lieutenant Garvin’s Individual Deceased Personnel File (IDPF). And so, the mystery is solved: In an effort to return to England, Lieutenant Garvin made a remarkable flight of nearly 200 miles, alone, roughly paralleling the coasts of the Netherlands and Belgium, only to crash in France.

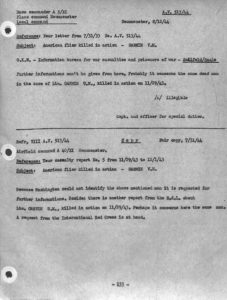

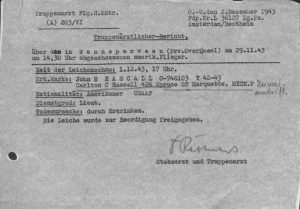

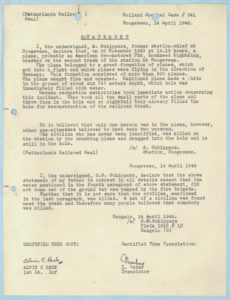

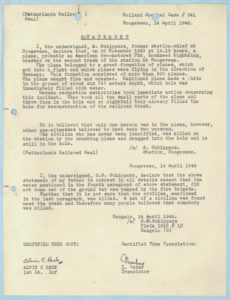

First, two sets of German documents from his IDPF.

Though intended to record information about POWs (note the word “Gefangenenlager” in the upper left corner, as well as data fields for a variety of biographical details), these cards instead cover – in very sparse and enigmatic detail – information about Lt. Garvin’s death. The upper set lists the location (Hondschoote), incorrectly recording the date as December 1, with Garvin having been a “Flg” (flieger (flyer)) and lists his place of burial. The lower set lists the aircraft type as a “Masch. Lightning” (machine Lightning), and includes a note referring to Luftgaukommando Report AV 513/44.

Both cards include English-language translations (in pencil) of the original German, obviously written post-war.

So, it turns out that Luftgaukommando Report AV 513/44 – below – was absolutely correct. “V.M. Garvin” was indeed “J.M. Garvin”. This explains the ambiguity and confusion in the three documents comprising Luftgaukommando Report A.V. 513/44, which are transcribed below:

So, it turns out that Luftgaukommando Report AV 513/44 – below – was absolutely correct. “V.M. Garvin” was indeed “J.M. Garvin”. This explains the ambiguity and confusion in the three documents comprising Luftgaukommando Report A.V. 513/44, which are transcribed below:

A.V. 513/44

Airfield command A 40/XI

Air-force garrison battalion XI Neumuenster

Personal Casualty Report No. 5 – Period: 11/29/ to 12/1/43 – Distributor: As usual.

On 11/29/43 crashed by collision at Handschoote [sic] – Pas de Calais

GARWIN V.M. Grave N. 165

Roster 16/79-83

Distributor: As usual.

Date 12/8/43

/s/ Schwach

____________________

A.V. 513/44

Geneva 5/2/44

International Red Cross

Central Agency for POWs

Serv. USA – MS / cjw – DUS 1460

TO:

O.K.W. – Army information bureau Berlin W.30

In your telegram from 3/6/44 No. 1635 and in your additional roster from 2/25/44 you reported to us the death of Lt. U.M. GARWIN

Otherwise you report to us in your roster of dead men No. 20 from 3/16/44 the death of V.M. GARWIN.

Washington could not establish which flier is concerned by this report, and we request you to go into this statement and if possible to report further informations which can help to his identification.

Thanking you in advance for your endeavours, we are, Yours sincerely

/s/ illegible

International Red Cross

Central Agency for POWs.

Refr. VIII A.V. 513/44

Fair copy, 9/13/44

International Red Cross Geneva.

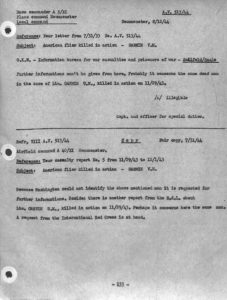

Reference; Your letter from 5/2/44 Serv. USA MS /ojw – DUS 1460

Subject: American flier killed in action.

It is possible that it concerns the same man in the case of Ltn. GARVIN U.M. killed in action on 11/29/43 and GARWIN V.M. Further information can’t be made unfortunately.

/s/ illegible

____________________

____________________

A.V. 513/44

Base Commander A 5/XI

Place command Neumuenster

Local command

Neumuenster, 8/12/44

Reference: Your letter from 7/31/33 No. A.V. 513/44

Subject: American flier killed in action – GARWIN V.M.

O.K.W. – Information bureau for war casualties and prisoners of war – Saalfeld / Saale

Further informations can’t be given from here. Probably it concerns the same dead man in the case of Ltn. GARWIN U.M., killed in action on 11/29/43.

/s/ illegible

Capt. and officer for special duties.

Refr. VIII A.V. 513/44

COPY

Fair Copy, 7/31/44

Airfield command A 40/XI Neumeunster.

Reference: Your casualty report No. 5 from 11/29/43 to 12/1/43

Subject: American flier killed in action – GARWIN V.M.

Because Washington could not identify the above mentioned man it is requested for further informations. Besides there is another report from the R.d.L. about Ltv. GARVIN U.M., killed in action on 11/29/43. Perhaps it concerns here the same man. A request from the International Red Cross is at hand.

____________________

So, the central question: What happened to Lieutenant Garvin? A definitive answer will forever remain unknown, but a reasonable conjecture can still be made.

To start, a statement – filed by the Communications Officer of the 55th Fighter Group – accompanies the reports by Captains Ayers and Franklin in MACR 1427. This document is a record of radio communication between a pilot with radio call sign “Swindle 48”, immediately followed by a similar call from “Swindle 38” (surmised to have been one and the same person) with “Rockcreek”, the radio call sign of the 55th Fighter Group. Note that: 1) The call was repeated and appears to have been clearly and coherently spoken, suggesting (?) that the pilot was uninjured, and 2) There is no acknowledgement of Rockcreek’s transmission actually having been received by Swindle 38 / 48.

A transcript of the Receivers Log follows:

Extract from VHF Ground Receivers Log of November 29, 1843:

To Rockcreek From Swindle 48: Request homing, 1-2-3-4-5 Over

To Swindle 48 From Rockcreek: Steer 332, Over

To Rockcreek From Swindle 38: Request Homing, etc.

The Homing Station log also shows the transmission of another “steer” of 340 [degrees] to Swindle 48. However, an acknowledgement of the receipt of either of these transmissions by Swindle 48 does not appear. It will be noted that immediately following the communication Swindle 38 initiated his call for “Homing”. It is possible that Swindle 38 had called previously and the call was mistaken to be Swindle 48.

____________________

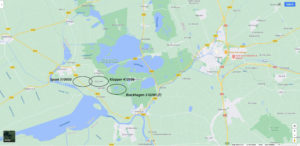

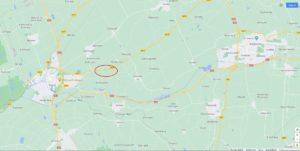

Here are some maps based on the transcript of the radio communication.

Map1 ) Using my handy-dandy 360-degree Staedtler protractor (not manufactured in the United States – but, I digress…!), and by setting Nuthampstead as a point of origin with “0” degrees at due east, I created this Oogle map showing steer plots of 332 and 340 degrees to Nuthampstead, from continental Europe. Projecting these plots southeast towards continental Europe shows that both intersect the Belgian coast: The first near Nieuwpoort, and the latter north of Bruges. Note the time for “332” is 15:17, while no time is recorded for “340”. Assuming that “340” was transmitted first and “332” later (for which there is no certainty) suggests that the transmissions are directed towards an aircraft flying along the Belgian and French coastline and travelling southwest. (This map does not address the question of magnetic declination.)

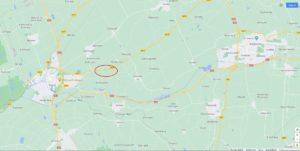

Map 2) This Oogle map shows a straight-line course between Hoogeveen in the Netherlands and Hondschoote in France, which I think would approximate the direction of flight taken by Lt. Garvin. The steer plots broadcast by Rockcreek to Swindle 38 / 48 can be seen to intersect the projected flight path in Belgium.

Map 2) This Oogle map shows a straight-line course between Hoogeveen in the Netherlands and Hondschoote in France, which I think would approximate the direction of flight taken by Lt. Garvin. The steer plots broadcast by Rockcreek to Swindle 38 / 48 can be seen to intersect the projected flight path in Belgium.

Map 3) Hondschoote, in relation to Dunkirk.

Map 3) Hondschoote, in relation to Dunkirk.

Map 4) Hondschoote, in relation to Lt. Garvin’s place of burial at Saint Omer. He was interred in an isolated grave (Grave 165) at the Longuenesse (Saint Omer) Souvenir Cemetery, where are interred nearly 3,400 Commonwealth war dead from the Great War.

Map 4) Hondschoote, in relation to Lt. Garvin’s place of burial at Saint Omer. He was interred in an isolated grave (Grave 165) at the Longuenesse (Saint Omer) Souvenir Cemetery, where are interred nearly 3,400 Commonwealth war dead from the Great War.

Thus for James Michael Garvin, fighter pilot.

Thus for James Michael Garvin, fighter pilot.

More importantly, what of James Michael Garvin, the man?

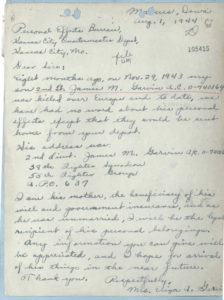

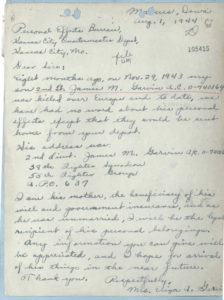

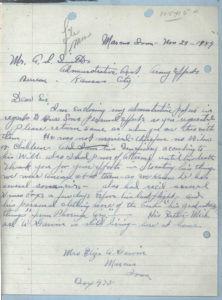

In partial answer, here are his mother’s letters in his IDPF:

Marcus, Iowa

Aug. 1, 1944

Personal Effects Bureau,

Kansas City, Quartermaster Depot,

Kansas City, Mo.

Dear Sirs:

Eight months ago, on Nov. 29. 1943 my son 2nd Lt. James M. Garvin A.C. 0-740164 was killed over Europe and to date, we have had no word about his personal effects except that they would be sent home from your depot.

His address was:

2nd Lieut. James M. Garvin A/C. 0-740164

38th Fighter Squadron

55th Fighter Group

A.P.O. 637

I am his mother, the beneficiary of his will and government insurance, and as he was unmarried, I will be the legal recipient of his personal belongings.

Any information you can give will be appreciated, and I hope for arrival of his things in the near future.

Thank you.

Respectfully,

Mrs. Eliza A. Garvin

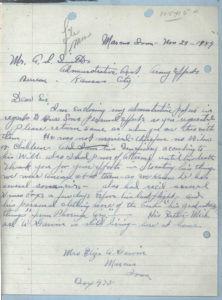

Marcus Iowa – Nov 29 – 1944

Marcus Iowa – Nov 29 – 1944

Mr. A.S. Smith

Administrative Asst. Army Effects Bureau

Kansas City.

Dear Sir,

I am enclosing my administrative papers in response our son’s personal effects as you requested. Please return same as when you are thru with them. He was not married – therefore no widow or children. And I am his beneficiary according to his Will. Also I had Power of Attorney until his death. Thank you for your efforts in locating his things. We were anxious about them – as we know he has several souvenirs – also had rec’d several Xmas boxes a few days before his last flight – and his personal clothing were of the best – “his graduation things” from Phoenix Ariz. His father – Michael A. Garvin is still living here at home.

Mrs. Eliza A. Garvin

Marcus

Iowa

Box 475

In the context of the past century – and even today in 2021 – James M. Garvin was a child born quite late in the lives of his parents, Eliza and Michael Garvin. They were 44 and 52, respectively, during the year of his 1915 birth. They died in 1951 and 1947.

Lieutenant Garvin is buried at Holy Name Cemetery, in Marcus, Iowa.

This was his seventh mission.

________________________________________

2 Lt. James William Gilbride (bailed out – did not survive), P-38H 42-67097, MACR 1272

Photo of James Gilbride from Double Nickel, Double Trouble

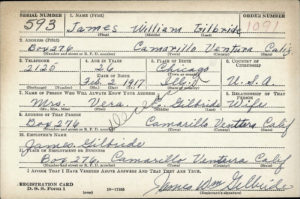

Here’s Lieutenant Gilbride’s Draft Registration Card.

Here’s Lieutenant Gilbride’s Draft Registration Card.

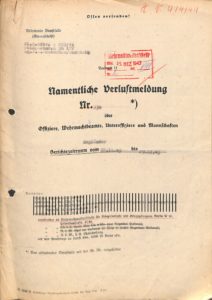

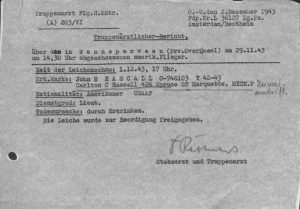

Here’s the cover page of the composite Luftgaukommando Report (number AV 414/44) for Lieutenants Gilbride and Hascall (see more about Hascall below).

Here’s the cover page of the composite Luftgaukommando Report (number AV 414/44) for Lieutenants Gilbride and Hascall (see more about Hascall below).

As you can see from the below image, the document is actually a single 11″ x 17″ sheet having twenty information fields, with two binder holes in the center. Since Lieutenants Gilbride and Hascall did not survive, many of the information fields remain blank by default.

As you can see from the below image, the document is actually a single 11″ x 17″ sheet having twenty information fields, with two binder holes in the center. Since Lieutenants Gilbride and Hascall did not survive, many of the information fields remain blank by default.

According to his biographical profile at FindAGrave, and confirmed in the Lutfgaukommando Report and IDPF, Lt. Gilbride managed to escape from his fighter, but his parachute failed.

According to his biographical profile at FindAGrave, and confirmed in the Lutfgaukommando Report and IDPF, Lt. Gilbride managed to escape from his fighter, but his parachute failed.

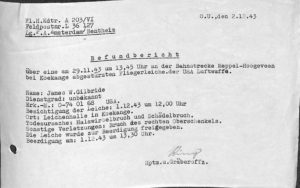

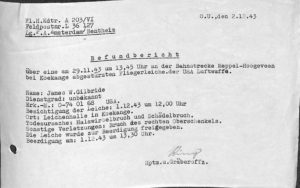

Here’s the German form reporting his death, which when searching NARA’s database is “pulled up” with the digitized images of Luftgaukommando Report AV 414/44.

The following correspondence, among the many pages in Lt. Gilbride’s lengthy IDPF, add a dimension to this story (and so very many other stories like it) wholly different from topics like tactics and technology; aerial victory claims (Lt. Gilbride didn’t have any – he simply did his duty); camouflage and markings; serial numbers; mission schedules. (Albeit those facets of history are – well, yes – essential.)

The following correspondence, among the many pages in Lt. Gilbride’s lengthy IDPF, add a dimension to this story (and so very many other stories like it) wholly different from topics like tactics and technology; aerial victory claims (Lt. Gilbride didn’t have any – he simply did his duty); camouflage and markings; serial numbers; mission schedules. (Albeit those facets of history are – well, yes – essential.)

The words within these letters represent a side and consequence of war that, while not necessarily “making it into the history books” – in terms of that hackneyed expression – quietly persists, in its own way, as an echo that over times becomes inaudible. But hopefully, never silent.

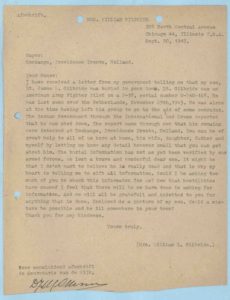

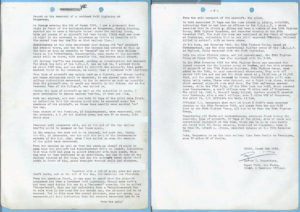

The following three documents are communications between Lt. Gilbride’s mother, and Mr. H. Solt, mayor of De Wijk, Holland. Note that the letters appearing below are not Mrs. Gilbride’s original correspondence. Instead, they’re English-language transcripts of letters received by Mayor Solt, which were incorporated into Lt. Gilbride’s DPF.

This is Mrs. Gilbride’s letter of September 20, 1945.

“You can be of great help to all of us here at home, his wife, daughter, father and myself by letting us know any detail however small that you can get about him. The burial information has not as yet been verified by our armed forces. We lost a brave and wonderful dear one. It might be that I don’t want to believe he is really dead and that is why my heart is telling me to sift all information.”

Afschrift.

Afschrift.

MRS. WILLIAM GILBRIDE

308 North Central Avenue

Chicago 44, Illinois U.S.A.

Sept. 20, 1945.

Mayor:

Koekange, Providence Drente, Holland.

Your Honor:

I have received a letter from my government telling me that my son, Lt. James Gilbride was buried in your town. Lt. Gilbride was an American Army Fighter Pilot on a P-38, serial number 0-740-168. He was last seen over the Netherlands, November 29th, 1943. He was alone at the time having left his group to go to the aid of some comrades. The German Government through the International Red Cross reported that he was shot down. The report came through now that his remains were interred at Koekange, Providence Drente, Holland. You can be of great help to all of us here at home, his wife, daughter, father and myself by letting us know any detail however small that you can get about him. The burial information has not as yet been verified by our armed forces. We lost a brave and wonderful dear one. It might be that I don’t want to believe he is really dead and that is why my heart is telling me to sift all information. Would I be asking too much of you to check this information for us? Now that hostilities have ceased I feel that there will be no harm done in asking for information. And we will all be grateful and indebted to you for anything that is done. Enclosed is a picture of my son. Could a mistake be possible and he [be] ill somewhere in your town? Thank you for any kindness.

Yours truly.

(Mrs. William L. Gilbride.)

Voor eensluidend afschrift

De Secretaris van de Wijk

____________________

Here’s Mayor Slot’s reply of October 22, 1945.

Note the statement, “Eye-witnesses declared, that he left his group to go to the aid of some of his comrades.” Thus, it would seem that civilian observers of the November 29 air battle witnessed Captain Franklin and Lt. Gilbride’s attempt to aid the 38th Fighter Squadron. The distance of Lt. Gilbride’s body from his crashed P-38 – 6 kilometers (over 3.5 miles) when found by members of the Dutch Air-raid Precautions Service – suggests that he bailed out from his aircraft (an event not actually witnessed by his element leader, Captain Franklin) from an appreciable altitude.

GEMEENTE DE WIJK (D.)

GEMEENTE DE WIJK (D.)

AFSCHRIFT. DE WIJK (D), 22nd. October 1945.

No. 637

Antwoord op brief van

Onderwerp:

Mrs. William. L. Gilbride.

308 North Central Avenue

Chicago Illinois. U.S.A.

Dear Mrs. Gilbride,

I received yours of the 20th. of September, and, of course, I am quite willing to tell you all I know about your son.

On the 29th. of November 1943 an American Fighter plane was shot down during an air-fight. The pilot was your son, Lt. Gilbride. He fell down near the railway at Koekange in de Wijk, about 6 kilometers from his plane. When the men of the Air-raid Precautions Service arrived, he had already died. His body was not damaged and the men present at the spot immediately recognized him from the picture enclosed in your above letter. His mark of recognition contained the following inscription:

James W. Gilbride, 0-740-168 T 42/43/0 Ventura (California).

On the 30th. of November 1943 he was buried on the general cemetery at Koekange.

His possessions were seized by the Air-raid Precautions Service, but later overtaken by the Germans.

Mr. Hendriks, Commander of the Air-raid Precautions Service helped many allied pilots to flee from the Germans. Unfortunately it was too late for your son, as he had already died. Eye-witnesses declared, that he left his group to go to the aid of some of his comrades.

A committee has collected money to erect a monument on his grave, but the American Government intends to re-inter all soldiers, killed on central cemeteries so that the erecting of a monument has been postponed for the time being. I suppose I am allowed to keep the picture, that I can hand it to Mr. Hendriks, who rendered assistance at the time.

I console with you on the grievous loss of your dear son, one of the many, that offered up their life for the freedom of our country too.

Let us hope, that his sacrifice has not been in vain and that this terrible war has been the last one.

On the birthday of our Queen, the 31st of August, a service in commemoration of the heroes who fell in the battle for freedom was held near the grave of your son.

Many inhabitants were present. When playing the national hymns a wreath was laid on the grave. The service made a deep impression on the people.

I hope that knowing this, you will have a better remembrance of your dear son.

Yours truly

signed H. Slot.

Mayor of de Wikj

Drenthe – Holland.

Voor eensluidend afschrift,

De secretaris van de Wijk,

____________________

And, Mrs. Gilbride’s reply of November 26, 1945 to Mayor Slot.

“Day after day and always our hearts were heavy not knowing whether he was cold, hungry or tormented. He was glad to do his duty and if it were God’s will that he should die we were willing to accept that too. The thing that haunted us was not knowing what had happened to him. Your letter is something that we will always treasure and cherish.”

AFSCHRIFT. MRS. WILLIAM GILBRIDE

AFSCHRIFT. MRS. WILLIAM GILBRIDE

308 No. Central Avenue

Chicago44, Illinois, U.S.A.

November 26, 1945.

Mayor of de Wijk.

Drenthe – Holland.

Dear Sir,

There are no words to express our thanks and gratitude to you and the others of Drenthe for the kindness and care shown our son the late Lt. James Gilbride. Since he was reported missing, we have not only grieved but constantly wondered and worried as to his fate, what he suffered and into whose hands he fell. Day after day and always our hearts were heavy not knowing whether he was cold, hungry or tormented. He was glad to do his duty and if it were God’s will that he should die we were willing to accept that too. The thing that haunted us was not knowing what had happened to him. Your letter is something that we will always treasure and cherish. God has heard our prayers. In His mercy He let our son’s death be swift and merciful. He was watching over him even in death, for it was God who directed him to fall in your town where good and kind people laid him to rest. It touched us deeply to know that a monument was to be erected on his grave, that the service in memory of the war heroes, held on your Queen’s birthday, was held near the grave and a wreath placed there. I am sending our War Department a photographic copy of your letter. It is his father’s wish and mine that he might be left to rest in peace right there. This, of course rests with our War Department and as to whether your Queen would grant him that privilege and care for his grave. Do let Mr. Hendriks keep the picture. I know how busy you must be so I am going to ask if Mr. Hendriks could arrange to have a couple of snaps taken of the burial place and grave. Am enclosing three dollars to cover the expense. Have sent four packages with food and sweets. Will be sending more and clothing too. I know that nothing we do can repay what has been done. If there is anything that we can do please do not hesitate to ask us. Our son has been decorated for having gone back at different times to help his comrades. My husband’s maternal grandparents came from Utrech, in Holland. I put two American Flags in one of the boxes to be placed on the grave. My husband and I are going to try and visit the grave in the future. Again accept our thanks.

Sincerely yours,

signed. Bess Marie Gilbride.

Voor eensluidend afschrift,

de Secretaris van de Wijk,

____________________

If Lt. Gilbride has been remembered at all, this has probably been in association with his assigned P-38H, aircraft 42-67053, “CY * L“, the name of which – “Vivacious Vera” – was inspired by his wife’s own name.

The plane’s history was recorded on its port gun-bay access door (salvaged after its crash-landing on December 13, 1943 – seen link below), and states:

“This part of door cover retrieved from wreckage of P-38H 42-67053 with the squadron letters CYL. Flown first at Lockheed Liverpool Air Depot by C.H. Wilson, chief Test Pilot, Lockheed, 9-15-43. 1st ship to arrive at this field, 9-21-43. 1st person to fly plane on this field, Col. Frank B. James, 9-22-43. Originally assigned to Lt. Gilbride 10-10-43, who was missing in action 11-29-43. Ship was named after his wife. Reassigned to Lt. Goudelock 12-12-43.

“Lucky Ship”

Lt. Hiner returned safely from Zuyder Zee on single enine, distance 250 miles.

Lt. Stanton returned safely from Ruhr Valley on single engine, distance 250 miles.

Lt. Goudelock returned from Kiel on single engine, distance 375 miles 12-13-43, and crashed in village of Ludham, due to lack of gas. He was not seriously injured.

Ship completed 18 missions inclusive.

Well, the name and nose art are memorable, the latter I would think inspired by a pin-up by or in the style of Alberto Vargas. (Well, I’ve not yet been able to identify any work by Vargas that actually resembles this painting!)

Much more importantly, and perhaps inevitably – given the “way of the world” – forgotten over the past near-eight decades was the fact that the real “Vera”, Lt. Gilbride’s wife, was much more than simply a nickname on an aircraft.

Much more importantly, and perhaps inevitably – given the “way of the world” – forgotten over the past near-eight decades was the fact that the real “Vera”, Lt. Gilbride’s wife, was much more than simply a nickname on an aircraft.

Found within Lt. Gilbride’s IDPF, two of her letters, and one letter of her mother, appear below.

__________

This letter was typed on “SkyMail” stationary, back when when air-mail was still a “thing”, and physical letters were equally a taken-for-granted “thing”. Sent to the Army Effects Bureau in Kansas City, Vera E. Gilbride requests the property of her late husband.

Route 1, Box 203-B

Ventura, California

September 12, 1944

A.L. Smith, Administrative Assistant

Army Effects Bureau

Kansas City Quartermaster Depot

601 Hardesty Avenue

Kansas City 1, Missouri

No. 92228 D

Dear Mr. Smith

I am in receipt of your letter of September 9, 1944.

Will you please send me the personal property of my husband, Lieutenant James W. Gilbride to the above address.

I am Lieutenant Gilbride’s legal widow.

Sincerely,

Mrs. Vera E. Gilbride

__________

__________

This letter, penned by Vera’s mother over a year later – Mrs. Mortime Lyman Eddy (her actual name was Laurel Nelson Etta Edy) – was also addressed to the Army Effects Bureau. The impetus for her communication with the army was the family’s receipt of Lt. Gilbride’s wedding and signet rings which, remarkably and hauntingly, were received by the family exactly two years and one day after Lt. Gilbride’s death. Note that the family’s receipt of the Lieutenant’s rings has caused far more consternation and confusion than it did comfort: Other than having earlier been notified of the Lieutenant’s death, per se, it seems that absolutely no further information was received during the intervening two years. The letter concludes with Mrs. Eddy’s frank expression of worry about her daughter’s well-being.

Rt. 1 Bx 203-B

Ventura, Calif.

Nov. 30, 1945

War Department

Army Effects Bureau

Kansas City Quartermaster Depot

601 Hardesty Avenue

Kansas City 1, Missouri

Dear Sirs:

A package consisting of a wedding ring and a signet ring, received today, personal effects belonging to 2nd Lt. James W. Gilbride, 0-740168. Two years ago yesterday, Nov. 29, 1943, he was shot down, presumably. We have never received any authentic word, other than missing, then dead. Could you give me any direct information about his body, or direct me to some one that does know? He had these rings on, that we do know, for it was a pledge. Now we know the body was found, and evidently by friendly people, otherwise the rings would have been taken off. Was he alive when found and took to a hospital? My daughter is ill [and] if she could get something definite she could no doubt pull her self out of this – I’m terribly worried about her. This is our first attempt to try and find out something about him. Please tell us where the rings came from and has he been alive for a long time since going down?

Yours very truly

s/ Mrs M.L. Eddy.

__________

__________

Some time during the subsequent two and a half years, Vera Gilbride remarried, to become Vera E. Gilbride Olson: She symbolically retained Lt. Gilbride’s surname. In this letter, she notifies the Army of her request to have Lt. Gilbride buried at an American military cemetery.

March 3, 1947

The Quartermaster General

Attention: Memorial Division

Gentlemen:

I, Mrs Vera E. Gilbride Olson, widow of the late Lt. James W. Gilbride SN 0-740168 have remarried. My current address is Vera E. Olson, Rte 1 Box 376, Ventura, Calif. It is my request that the remains be left in an American Cemetery over-seas.

If I am not the authorized person will you please inform me that has been done so I will be able to tell the deceased minor daughter.

Very truly yours

Mrs. Vera E. Olson

The above is only a small portion of the correspondence within the IDPF for Lt. Gilbride, the majority of which pertains to the local of his final place of burial: Whether at an ABMC cemetery in Europe or the United States, and in case of the latter, where specifically within the United States. Sadly, the correspondence strongly suggests little to no communication, if not a near-complete lack of interaction, between Lt. Gilbride’s parents and their daughter-in-law.

The above is only a small portion of the correspondence within the IDPF for Lt. Gilbride, the majority of which pertains to the local of his final place of burial: Whether at an ABMC cemetery in Europe or the United States, and in case of the latter, where specifically within the United States. Sadly, the correspondence strongly suggests little to no communication, if not a near-complete lack of interaction, between Lt. Gilbride’s parents and their daughter-in-law.

Time passed.

After the construction of the National WW II Memorial and the creation of its associated website and database, Vera Etta Eddy Gilbride Olson created two Memorial pages in her late husband’s honor. You can view them here and here. One of the Memorial pages includes mention of the couple’s daughter having been born six weeks after her father was killed in action.

Born on November 28, 1916, Vera Olson died on November 1, 2004. She, her parents, and her siblings are buried at Ivy Lawn Memorial Park in Ventura, California.

The original version of this post displayed an Oogle map of the area between Hoogeveen and Meppel, albeit with no specifics about where Lt. Gilbride and his P-38 fell to earth. The caption was: “This Oogle map shows the general location where Lt. Gilbride and his plane fell to earth: In the vicinity of De Wijk and Koekange, near the railroad line connecting Meppel and Hoogeveen.”

This revised map, based on information at Teunis Schuurman’s WW II – Research by PATS blog, shows the location where Lieutenant Gilbride’s body was found: “He was found in Koekange near the Emsweg (former Municipality De Wijk). The aircraft did crash in the Oosterboer – location Binnenweg – (nowadays new housing).”

Born in 1917, James William Gilbride, whose parents resided in Chicago, is buried at Camp Butler National Cemetery, in Springfield, Il. (Plot C, Grave 128)

Born in 1917, James William Gilbride, whose parents resided in Chicago, is buried at Camp Butler National Cemetery, in Springfield, Il. (Plot C, Grave 128)

This was his tenth mission.

____________________

2 Lt. John Sherman Hascall, P-38H 42-67016, MACR 1424

20th Fighter Group, 77th Fighter Squadron

(“Spare”, with 2 Lt. Robert D. Frakes)

Photo of Lieutenant Hascall, from the Michigan Technological University Website.

Lieutenant Hascall’s Draft Registration Card…

Lieutenant Hascall’s Draft Registration Card…

Lt. Hascall was able to escape from his damaged P-38 and deploy his parachute successfully. Sadly, he had the awful misfortune of descending into the Schutsloterswidje, a small lake west of Meppel (shown in the Oogle map below). Ironically an accomplished athlete and excellent swimmer, he was unable to extricate himself from his parachute and was pulled underwater. Despite the concerted efforts of rescuers and a local physician, he did not survive.

Lt. Hascall was able to escape from his damaged P-38 and deploy his parachute successfully. Sadly, he had the awful misfortune of descending into the Schutsloterswidje, a small lake west of Meppel (shown in the Oogle map below). Ironically an accomplished athlete and excellent swimmer, he was unable to extricate himself from his parachute and was pulled underwater. Despite the concerted efforts of rescuers and a local physician, he did not survive.

Here is the German form reporting Lieutenant Hascall’s death, this document being associated (via searching NARA’s database) with Luftgaukommando Report AV 414/44.

An Oogle map view of Schutsloterswidje…

An Oogle map view of Schutsloterswidje…

Here’s a low-resolution view of the Schutsloterwijde (looking south), by Marco van Middelkoop, from AeroPhotoStock, an image bank for aerial photos of the Netherlands. You can view a (much) higher resolution image here.

Caption: “Schutsloterwijde, De Wieden, Nederland, 6 juni 2015. De Wieden vormt samen met de Weerribben het Nationaal Park Weerribben-Wieden, dit park is het grootste aaneengesloten laagveenmoeras van Noordwest-Europa. Het landschap is vooral ontstaan door vervening en rietteelt. De plassen zijn ontstaan doordat bij het opbaggeren van turf de trekgaten, waaruit de turf werd gebaggerd, te breed werden en de ribben waar de turf op werd gedroogd te smal. Tijdens de stormen van 17767 en 1825 werden de ribben weggeslagen en ontstonden onder andere de Beulakerwijde en Belterwijde.”

Translation: “Schutsloterwijde, De Wieden, The Netherlands, June 6, 2015. The Wieden, together with the Weerribben, form the Weerribben-Wieden National Park, this park is the largest continuous peat bog in northwestern Europe. The landscape was mainly created by dying and reed cultivation. The puddles were created because during the dredging of peat, the draft holes from which the peat was dredged became too wide and the ribs on which the peat was dried too narrow. During the storms of 17767 and 1825 the ribs were knocked away and the Beulakerwijde and Belterwijde, among others, were created.”

Lt. Hascall is buried at the Netherlands American Cemetery and Memorial (Plot H, Row 8, Grave 9), in Margraten, the Netherlands. His story and life are recounted at The Last Flight of John Hascall, at Michigan Technological University Magazine.

Lt. Hascall’s record at the ABMC website indicates that he was the recipient of one military award – the Purple Heart – implying that he flew less than five combat missions.

________________________________________

Two survivors: Lieutenants Carroll and Suiter

2 Lt. John Joseph Carroll (38th Fighter Squadron), MACR 1431

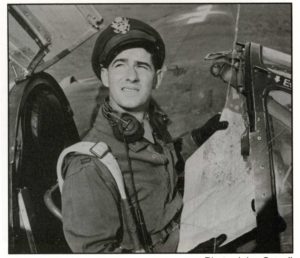

“Lt. Albert A. Albino of Aberdeen, Wash., and Lt. John J. Carroll [right] of Detroit, Mich., both members of the 38th Fighter Squadron stationed at Nuthampstead, England, discuss the map of a future target in the squadron pilot room.” (Army Air Force Photo B1 79830AC / A14145 1A)

Photo of John J. Carroll, from Double Nickel, Double Trouble

Photo of John J. Carroll, from Double Nickel, Double Trouble

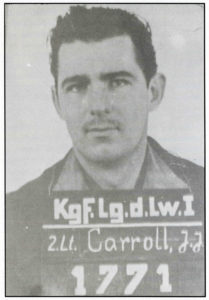

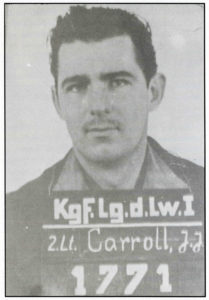

John Carroll’s POW identification photograph, also from Double Nickel, Double Trouble. He was imprisoned in the North Compound of Stalag Luft I.

John Carroll’s POW identification photograph, also from Double Nickel, Double Trouble. He was imprisoned in the North Compound of Stalag Luft I.

Here is John Carroll’s (no longer a Lieutenant when he wrote this!) account of the November 29 mission, from Double Nickel, Double Trouble. He titled his story: “The Saga of ‘A’ Flight, Lost November 29, 1943.”

Here is John Carroll’s (no longer a Lieutenant when he wrote this!) account of the November 29 mission, from Double Nickel, Double Trouble. He titled his story: “The Saga of ‘A’ Flight, Lost November 29, 1943.”

“This tabulate returns to the days of yesteryear when 20/20 vision was quite normal, coordination was automatic, briefings were at uncompassionate hours, each time respects were paid to “Festung Europe”; there were numerous more of them than there were of us. Such was the circumstance, November 29th, 1943.

“I was flying wing to our C.O., Major Milton Joel, when our flight was cut off by a gaggle of Me-109s and the group was headed away from us in a westerly direction. Joel and I went into the “weave formation”, which theoretically would protect one another’s tail. Directly after our first pass-by I caught a glimpse of a P-38 headed down trailing smoke and minus a section of tail (Albino or Garvin?). Following our third pass-by it became obvious that “the weave” does not perform without flaw. At the crest of my turn I glanced across the projected pattern and observed what should be Joel’s A/C seemingly to disintegrate.

“Almost immediately thereafter, I felt an instant yaw to starboard and noted the engine on fire, plexiglass everywhere, and the instrument panel badly damaged. I kicked rudder into the yaw and opened the port engine to the firewall, at the same time putting the nose straight down and headed for a cloud layer. On breaking out at the base of the layer, and utilizing it for top cover, I took a heading for England on the magnetic, which was still operable. After approximately 5 or 10 minutes, with the cross feed off (the prop would not completely feather), I determined the fire was getting out of hand. I realized I could not make the island without either exploding or crashing into the North Sea, which at that time of year had little in common with the Caribbean!

“When bailing out of a P-38 one must render considerable delicacy, lest one desire a speedy trip to eternal reward – or damnation as the case may be. At this point I found that the canopy release handle would not perform its assigned task. By raising the seat and using my head as a battering ram and with the aid of a reasonable slipstream I was able to dislodge the obnoxious piece of equipment. I then lowered the port wing, trimmed the A/C into a 45 degree climb, cut the engine, and climbed out onto the wing holding on to the corner of the canopy. At almost the peak of stall, I let go and missed the tail by about a foot. This was most fortunate, as going out feet first rather than on one’s belly, the counter-weight could proffer a rather serious problem.

“Now here is the period in which the individual obtains a morbid curiosity as to whether the chute is going to open. As a result of this dilemma I counted to ten, per instructions, faster than normal beings count to two. Upon reading this one may justly surmise as to its workability! May the Lord bless and keep all chute packers, past and present!

“The landing, if one may call it that, was on the roof of a barn-like building in Holland somewhere west of Meppel. Ignominiously the chute collapsed sending me on a Disney-like ride down the roof and ending, not unlike a ski-jump, on to some form of machinery. This display of dexterity lost me the use of my right leg for some months to come. It was also at this time that I came to realize that I had been wounded in the right hand and shoulder. Curiously, I felt neither until this time.

“The Wermacht arrived, having followed the chute down… One would have thought thay had caught John Dillinger rather than saintly John Carroll. “Luft gangster, Chicago, Roosevelt terror-flieger!” they greeted, plus a few chosen obscenities, which at this time I understood to a minor degree. (However, upon my release I was quite able to return curse for curse in fluent Kraut.)

“I was ultimately taken to Leewarden, Amsterdam, Dulag Luft, and finally to Stalg Luft I, Barth, Germany, in North Compound I, under Col. Byerly. I served as entertainment officer due to my background in broadcasting and the theater. This was a task of reasonable importance to the facilities at hand, and the substantial emphasis placed on morale. It even obtained a field promotion for me but I would be most remiss if credit for fortitude, versatility, and camaraderie to my compatriots were not acknowledged.

This revised map, based on information at Teunis Schuurman’s WW II – Research by PATS blog, shows the general location where Lieutenant Carroll’s plane – FOB Detroit – crashed: “…near the tiny farm community Zwartewatersklooster – just outside Zwartsluis.”

Born in 1919, John J. Carroll, Sr., died on June 11, 2003. He is buried next to his wife Catherine at Greenwood Cemetery, East Tawas, Michigan.

Born in 1919, John J. Carroll, Sr., died on June 11, 2003. He is buried next to his wife Catherine at Greenwood Cemetery, East Tawas, Michigan.

The mission of 29 November was his ninth.

________________________________________

2 Lt. Fleming W. Suiter (343rd Fighter Squadron), MACR 1273

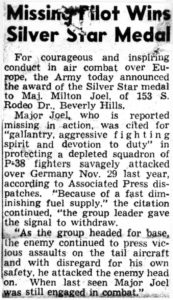

These news items about Lt. Suiter can be viewed at his FindAGrave biographical profile, where they have been provided by contributors Carl and Arthur Allen Moore III.

Along with Lt. Carroll, Lt. Suiter was the other survivor among the six 55th Fighter Group pilots shot down this day. Captured, he spent the remainder of the war as a POW the South Compound of Stalag Luft I. This was his seventh mission.

Along with Lt. Carroll, Lt. Suiter was the other survivor among the six 55th Fighter Group pilots shot down this day. Captured, he spent the remainder of the war as a POW the South Compound of Stalag Luft I. This was his seventh mission.

Remaining in the Army Air Force, he was – ironically – (how very inadequate a word) killed on military service in the United States nearly one year after the end of the Second World War: On August 10, 1946, his P-47N Thunderbolt (44-88653, of the 63rd Fighter Squadron, 56th Fighter Group, based at Selfridge Field, Michigan) crashed west of Antrim, New Hampshire.

An Oogle map view of Meppel, Holland, where Lt. Suiter came to earth.

The November 29 mission was his seventh.

Lt. Suiter is buried at Rome Proctorville Cemetery, in Proctorville, Ohio.

Lt. Suiter is buried at Rome Proctorville Cemetery, in Proctorville, Ohio.

________________________________________

The View from 1947: A search in Germany

At 1945’s end, Lieutenant Albino and Major Joel were still missing – albeit declared dead – their final fates unknown. In this regard, Major Joel’s Individual Deceased Personnel File includes a detailed report concerning the search for Lieutenant Albino, completed by T/4 John W. Johnson of the Army Graves Registration Command. The presence of this document in Major Joel’s IDPF is unsurprising, given that the circumstances under which both men vanished were in effect and reality parallel.

It is surprising that Major Joel’s name remains unmentioned in T/4 Johnson’s report, or was not the subject of an independent report. But, anyway…

In his effort to trace Lt. Albino’s fate, T/4 Johnson surveyed the German city of Oldenburg, and towns and villages to its south to southwest, in light of the Lieutenant’s last reported location in the Missing Air Crew Report. (The localities were Ahlhorn, Beverbruch, Cloppenburg, Edewecht, Falkenburg, Garrel, Molbergen, Nikolausdorf, and Petersfeld.) His conclusion, based on communication with public officials and clergy in those localities – that the Lieutenant did not crash in that vicinity – was entirely correct. But, the reason for its veracity would remain unknown until 1978, when Lt. Albino and his plane finally were confirmed to have fallen into the Dutch town of Hoogeveen, well to the southwest of those German towns and cities.

Here’s T/4 Johnson’s report.

ROTHWESTEN DETACHMENT

FIRST FIELD COMMAND

AMERICAN GRAVES REGISTRATION COMMAND

APO 171, US ARMY

13 December 1947

NARRATIVE REPORT OF

INVESTIGATION

I was dispatched on 23 October 1947 from this headquarters to Oldenburg, Germany (K-54/R-30) to investigate AGRC Case # 8632 pertaining to 2/Lt Albert A. Albino who was pilot of a P-38 and according to Operational Instructions # 41 was last sighted southwest by west of Oldenburg, Germany. Lt Albino failed to return from a bomber escort mission to Bremen, Germany. The date that the above mentioned flyer was last sighted near Oldenburg was 29 November 1943. The cause of death is not mentioned in MACR # 1428.

I first went to the administration office in Oldenburg to check their records. This office is in charge of the cemetery in Oldenburg and also has records of all Allied deceased in the county of Oldenburg. At this office I received a statement (see Incl # 1) that according to a notice left by the 611th QM GR Co., seventy deceased of American nationality who were buried in the Military section of the New Cemetery in Oldenburg were disinterred and evacuated to an unknown destination.

It was also stated that according to the records (see Incl. # 2) held by this office 2/Lt Albert A. Albino who died on 29 November 1943 was not buried in the Oldenburg Cemetery.

Edewecht, Germany (K54/R10) is about four (4) miles southwest by west of Oldenburg. I received a statement (see Incl. # 3) from the administration office of the community of Edewecht which covers all the surrounding villages in that vicinity. The statement reveals that they have no records pertaining to plane crashes. No one in this small town had any knowledge of any plane crashes so I then went to the county office in Cloppenburg, Germany (K53/R27) which is about 20 miles southwest by west of Oldenburg.

At the county office in Cloppenburg I received the only records they had (see Incl # 4) about American and English plane crashes.

There are two statements (see Incl’s # 5 and 6) received on 8 October 1947, and 9 October 1947 while I was investigating another case which mentioned a fighter plane which crashed in the village of Nutteln. The date of this plane crash is not the same as that of the plane crash in question.

At Ahlhorn, Germany (K53/W37) which is about 12 miles south of Oldenburg, I received a statement at the Police headquarters (see Incl. #7). The Police state that they have no records of any plane crashes, that all crashes were reported to the German Air Base in Ahlborn, and that the former Burgermeister may be able to give some information pertaining to plane crashes in this area.

Upon contacting Hans Roennen the former Burgermeister, I received a statement (see Incl. # 8) to the effect that all planes crashed in the vicinity and all deceased who were killed there in plane crashes were taken care of by the German soldiers of the Air Base in Ahlhorn, therefore there were no records kept by him.

I next went to the cemetery in Ahlhorn and contacted the cemetery caretaker. I received a statement (see Incl. # 9) that all Allied deceased were evacuated in July 1946 by a British Unit and that when an American team came there for American deceased they had discovered that two American deceased were removed by mistake probably by the British unit.

I learned while conducting this investigation that ninety (90) American deceased were buried in the New Cemetery at Bad Zwischenehn, Germany (K54/R10).

I first went to a Parson Bultermann in Bad Zwischenahn who kept the burial books in which all deceased were entered who were buried in the local cemetery. The Parson was not at home but I received a statement from his wife (see Incl. # 10) that no 2/Lt Albert A. Albino was entered in their burial books and one of the deceased buried in the cemetery in Bad Zwischenahn.

I next went to the community director’s office in the above mentioned city and received a statement (see Incl. # 11) that the name of Albert A. Albino 2/Lt does not appear on their records. I also received a copy from this office of a list of all Allied deceased who were buried in the local cemetery (see Incl. # 12). The notice of disinterment which was left by the 3048th QM GR Co who disinterred and evacuated the ninety American deceased in April and May of 1946 (see Incl. # 13) was also received.

At the town of Molbergen, Germany (K 53/W71) which is 25 miles southwest of Oldenburg I received a statement (see Incl # 14) from the community director that no American planes crashed there. Only one plane crashed which was a Canadian fighter plane.

At Garrel, Germany (K53/W18) which is 18 miles southwest of Oldenburg I received a statement from the former Burgermeister (see Incl. # 15) which gave information on four, 4 engine bombers that crashed in four near-by villages. He further states that all fighter planes that crashed in the community were those of German origin. I then proceeded to check two nearby villages that were mentioned in the statement above to determine whether an American fighter plane could have crashed in their areas.

Petersfeld was mentioned in the statement of the former Burgermeister of Garrel as the place where one 4-engine bomber had crashed. The community office of Varelbusch, Germany (K53/W71) is in charge of Petersfeld which is mostly swamp land. I received a statement from this office (see Incl. # 16) that all plane crashes were taken care of by the German Air Base of Ahlhorn and the deceased taken to Gloppenburg.

I then went to the Catholic Priest of Varelbusch who is in charge of the local cemetery. The statement received from the Priest (see Incl. # 17) states that there was no cemetery there during the war and that all deceased were buried in Cloppenburg.

At Falkenburg, Germany which is in the nearby vicinity of Garrel I received a statement (see Incl # 18) from a farmer who was the only one there who knew of a plane crash in the spring of 1943. This crash was a 4 engine American bomber and was all taken care of by German soldiers and the deceased and wreckage were taken to Cloppenburg.

At Beverbruch which is also in the vicinity of Garrel I received a statement from a farmer about another 4-engine bomber (see Incl # 19) which was also taken care of by the German Air Base of Ahlhorn. He had no knowledge of any fighter plane crashes.

I next-contacted a nearby farmer of the same village who stated (see Incl. # 20) that he only had knowledge of one plane crash which was of that mentioned in the statement above (Incl. # 19).

I then went to the town of Nikolausdorf which is also in the community of Garrel and contacted the Alderman who is in charge there. The statement I received from him (see Incl # 21) mentions three 4 engine bombers that crashed in the nearby vicinity which I already have received statements concerning.

CONCLUSION: It can be concluded that after investigating Oldenburg and community and all towns and villages south and southwest by west of Oldenburg down to Cloppenburg that the fighter-plane in question did not crash in the vicinity where it was last sighted as mentioned in Operational Instructions # 41.

/s/t/ JOHN W. JOHNSON

T/4 RA-20120960

Investigator

________________________________________

Time Moves On: A Postwar Memorandum

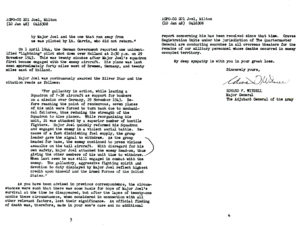

It is now 1949. Two years have passed since T/4 Johnson’s investigation into Lieutenant Albino’s fate. Major Joel’s IDPF now contains a memorandum to the Casualty Section of the Adjutant General’s Office dated May 2, 19494, which – by combining and reviewing information from: 1) Missing Air Crew Reports, 2) a German list of American Dead reported on April 1, 1944, 3) a tabulation of VIII Fighter Command P-38 pilots lost in combat lost on November 29, 1943, and 4) what is obviously a set of Luftgaukommando Reports (though the term isn’t used in this Memorandum) for VIII Fighter Command P-38 pilots lost that day – arrives at the unavoidable conclusion that, given the information in these records and the passage of five and a half years, no further hope could possibly held for the survival of either the Lieutenant or Major.

Here’s the Memorandum:

AG 704 DEAD (2 May 49) McG/sap/1B737/1263

2 May 1949

MEMORANDUM TO: Officer in Charge, Casualty Section

Personnel Actions Branch, AGO

SUBJECT: Report of Death

The following named officers, members of the 38th Fighter Squadron, 55th Fighter Group, were reported missing in action since 29 November 1943, over Germany, while in flying pay status, by a radio message from USSOS, London to WAR, dated 4 December 1943, casualty message number 339065-S:

Maj – Milton Joel – 0416308

2nd Lt – Albert A. Albino – 0743300

Missing air crew report number 1429, dated 1 December 1943, currently on file in the Office of the Quartermaster General, reports that Major Joel was the pilot and sole occupant of a P-38 type aircraft, number 42-67020, of the 38th Fighter Squadron, 55th Fighter Group, which departed its base on 29 November 1943, on an escort mission to Bremen, Germany. The report further states that Major Joel was last seen flying with his wingman, Lieutenant Garvin, “SW by W of Oldenburg”, at 1410 hours, that he was believed lost as the result of enemy aircraft, and that the weather conditions at the time wore “CAVU Above An Overcast.” Captain Jerry H. Ayers, 0659441, is shown as the person who last sighted Major Joel.

A statement by Captain Ayers, attached to the missing air crew report is as follows:

“We were on a B-17 escort mission to Bremen, Germany, when at 14:10, just prior to our R.V. point we were jumped by Hot Bandits.

“Major Joel was leading the first section of the Squadron composed of eight ships. Lt Wyche was leading the other Flight in the lead section.

Capt Hancock was leading the second section and I had the other flight. Due to abortive aircraft Major Joel had lost his second element also Lt Wyche had lost his. Capt Hancock and his wing-man returned. My second element had returned and we were trying to rejoin into two fair ship flights. Then we were successively bounced by units from a group of about 40 enemy aircraft from one or two o’clock, out of the sun. We turned right into the attack and were engaged for some time. At the time of the first break was the last time that I saw Major Joel and his wingman, Lt Garvin, that I could recognize them.”

Another statement attached to the missing air crew report submitted by Captain R. C. Franklin, Jr., which reveals further information concerning the disappearance of Major Joel, reads as follows:

On 29 November 1943, my wingman, Lt J.W. Gilbride, and myself participated in an engagement in which Major Joel, C.O. of the 38th Fighter Squadron, and his wingman, Lt Garvin, were lost and possibly this statement may shed some light on their disappearance.

The main body of the group was proceeding toward home when Major Joel was heard calling for help from far behind us. Lt Gilbride and I turned back to help but it took several minutes for us to reach the fight. As we drew near we could see five P-38s engaged and each had from one to three ME 109s on its tail. Just before we went into the fight one P-38 rolled over and went down with its left engine leaving a very long and very heavy trail of black smoke and with a 109 behind. As my wingman and I flew into the middle of the engagement the E/A were surprised into rolling away from the ships they wore attacking and we were all able to take a heading for home. At this time there were four P-38s left besides my wingman and myself. As we started home we were followed by E/A and we tried to outrun them. One of the four P-38s ran away from the rest and disappeared. The five of us remaining were eventually caught by the E/A and engaged again.

After we saw the one P-38 go down smoking I did not again recognize Major Joel’s voice on the radio. The five of us that were later engaged by the pursuing E/A were, Capt Ayers, Capt Beaird, Lt Erickson, Lt Gilbride, and myself. On this attack I lost one engine that had been going bad and when I recovered the only other P-38 visible in the area was piloted by Lt Erickson. We came out together.

In view of the circumstances it is my personal opinion that the P-38 we saw shot down was piloted by Major Joel and the one that ran away from us was piloted by Lt Garvin, who did not return.”

Missing Air Crew Report number 1428, dated 1 December 1943, on file in the Office of the Quartermaster General, reports that Second Lieutenant Albert A. Albino, 0743300, was the pilot and solo occupant of a P-38 type aircraft, number 42-67051, of the 38th Fighter Squadron, 55th Fighter Group, which departed its base on 29 November 1943 on an escort mission to Bremen, Germany. Captain Thomas E. Beaird, Jr., 0427117, is reported as the person who last sighted Lieutenant Albino at 1410 hours, southwest by west of Oldenburg. Lieutenant Albino’s ship is believed to have been lost as a result of enemy aircraft and the weather conditions at the time were reported as “CAVU Above an Overcast”.

Attached to the report is the following statement of Captain Thomas E. Beaird, Jr:

Our flight was slightly trailing the other three flights going to the rendezvous. Our flight leader had to fall out and called to me to take over. I acknowledge and called the flight to step up the mercury as I was going to catch up. At this time Lt Albino was 2nd in the flight, approximately 3 ship lengths behind me and approximately 4 ship lengths in front of Lt Peters. We were in the same relative position, but had closed considerably on the leading flights, when someone called, “Bogies coming down at three o’clock, get rid of your tanks”. I turned to the right dropped my tanks and looked to see if Lt Albino and Peters had gotten rid of theirs. This was the last time I was able to locate Lt Peters or Albino as almost immediately we were bounced from approximately 8 o’clock and the lead flights from I think, about 1 o’clock.

After we tangled there seemed to be nothing but individual ships that joined up to make flights as best they could.”

A statement by Second Lieutenant Edward P. Peters, also attached to the missing air crew report, is as follows:

I was flying #2 position in a flight lead by Capt Hancock. Capt Hancock started a turn to the right, leaving because of engine trouble, and as we were deep in enemy territory I started with him, however, he called and said I should turn back to accompany group. I started to return but by this time I had fallen way back, out of formation and as I increased manifold pressure my left engine cut out at 24” HG-. I continued trying to catch up and ahead of me about ½ a mile was Lt Albino and ahead of him was Capt Beaird. He, Lt Albino, was quite a distance behind Capt Beaird and I followed for about 4 or 5 minutes. At this time the group was bounced and the order give to drop ‘babies’. I looked behind and directly below saw six E/A which I called in. I looked above and behind and saw one E/A diving at me from about 7 o’clock. I broke into him and he fired at me as he passed over top. I looked for the group but as I could only see their contrails, and duo to the one faulty engine, I turned and came back alone.

It is possible that the E/A which attacked me or the six below could have continued on their way and caught Lt Albino as he was straggling.”

German List of American Dead #22, dated 1 April 1944 at Saalfeld / Saale, Germany contains the following entry:

58 – USA – UNKNOWN – Flier – Machine – Shot down – Place of burial

Lightning – 29 November 1943 – not yet reported

1430 hours Holland

Letter of inquiry, AG 704 (24 Jun 44), dated 24 June 1944, was dispatched from the Adjutant General’s Office to the Commanding General, United States Forces, European Theater of Operations, requesting that the names of all “Lightning” pilots who became missing in action in that Theater on 29 November 1943 be reported to this office. In reply, a 2nd Indorsement, dated 15 July 1944, from Hq. USSTAF, was received which reported the names of seven “Lightning” pilots who were missing in action on 29 November 1943. The time and place that these officers were last seen as reported by this 2nd Indorsement, and their present status are shown below:

Name – ASN – Grade

Time – Place Last Seen – Present Status

Hascall, John S. – 0746103 – 2d Lt

1315 – over mid-Channel – KIA

Albino, Albert A. – 0743300 – 2d Lt

1410 – SW by W of Oldenburg – PDD

Garvin, James M. – 0740164 – 2d Lt

1410 – SW by W of Oldenburg – KIA

Carroll, John J. – 0743313 – 2d Lt

1410 – SW by W of Oldenburg – POW-EUS

Joel, Milton – 0416308 – Maj

1410 – SW by W of Oldenburg – PDD

Gilbride, James W. – 0740168 – 2d Lt

1440 – 10-15 Mi. W of Meppel – KIA

Suiter, Fleming W. – 0743383 – 2d Lt

1300 – near Heede, Germany – POW-EUS

Following the cessation of hostilities in the European Area, a number of official German records were captured, and are currently on file in this office. Although these records are incomplete, they, nevertheless, have assisted materially in solving the status of a number of persons previously reported missing in action. Reports currently on hand pertaining to the disposition of persons listed above are as follows:

Reports J 304 and AV 414/44 pertains to the downing of Lt Hascall at Wanneparveen (Oberuezel) on 29 November 1943, with cause of death listed as ‘drowned’ and interment on 3 Docember 1943 at Wanneparveen Cemetery, grave No, 1, west side, middle section.

Reports J 338 and AV 513/44, pertain to the downing of Lt Garvin on 29 November 1943, crashed by collision at Handschoote – Pas de Calais, listed as dead and interred in Grave No. 165.

Report No. AV 414/44 pertains to the downing of Lt Gilbride, on 29 November 1943 at 1345 hours, at Railroad Meppel – Hoogeveen, near Koekange, death caused by fracture of skull and cervical vertebra. He was interred on 1 December 1943 at Koekange Cemetey, (Drente) in grave No. 33, Row 2.

Report No. J 305, pertains to the capture of Lt Suiter as the result of the downing of a Lightning plane on 29 November 1943.

Report No. J 302, pertains to the capture of Lt Carroll on 29 November 1943 as result of the doming of a Lightning plane.

Report No. J 307 pertains to the downing of a Lightning plane at 1430 hours in Holland, pilot listed as dead, identification unknown.

The foregoing facts show that seven P-38 Lightning fighter pilots were reported missing in action on a raid to Bremen, Germany, on 29 November 1943. Due to many abortive planes from the original group, several individual planes formed new flights and several were unable to join up and became stragglers. Just prior to reaching the rendezvous point, the flight was jumped by a superior number of enemy aircraft. It was at this time that Lieutenant Albino was last seen by any of the surviving pilots, and none have furnished any definite concrete information as to whether or not he was actually shot down at this time. However, in view of his failure to return and the complete absence of any word from or of him since, it is reasonable to assume that he was shot down at this time, especially since he was straggling along and made an easy target. On the return flight shortly after leaving the target area, Major Joel was heard over the radio to have called for help. Two pilots, Captain Franklin and Lieutenant Gilbride, returned and observed five P-38’s engaged in combat with the enemy and each P-38 had from one to three enemy planes on its tail. Just before they entered the combat area, one P-38 rolled over and went down with its left engine leaving a very long and very heavy trail of black smoke, pursued by an enemy plane. Following the loss of this plane, the voice of Major Joel was no longer heard over the radio, and it was the opinion of Captain Franklin that this plane was piloted by Major Joel. However, the exact location of this action, whether over Germany or Holland, is not stated. All of the other missing pilots from this mission, with the exception of subject personnel, arc accounted for in the available captured German records. No doubt, can exist, that the unknown dead recorded is either Major Joel or Lieutenant Albino. Nevertheless, in view of the events leading up to the disappearance of subject persons, and the accuracy of the available German records, no hope can be entertained for the survival of subject persons. No doubt, the information which would accurately describe the place and fate of each of subject persons is contained in enemy records which were destroyed or lost during the confusion and turmoil of final days of the war.

It is recommended, therefore, that pursuant to the provisions of Section 9, Missing Persons Act, the foregoing information be accepted as an official report of death, and that a casualty report be initiated stating that subject personnel, listed in paragraph 1 above, were killed in action on 29 November 1943 in the European Area, while in flying pay status. The systemat will be processed in accordance with Paragraph 2b, Operations Bulletin 35, 1945. The casualty report and official report of death will include the following statement:

Finding of Death has been issued previously under Section 5, Public Law 490, 7 March 1942, as amended, showing presumed date of death as 3 September 1945. This “Report of Death” based on information received since that date, is issued in accordance with Section 9 of said Act and its effect on prior payments and settlements is as provided in Section 9.

Station and place of death: European Theater.

JOHN J. McGUIRE CONCUR:

Investigator

T.J. COLLUM

Major, AGD

OIC, Determination Unit

APPROVED: Recommended action will be taken

BY ORDER OF THE ACTING SECRETARY OF.THE ARMY:

SYLVIO L. BOUSQUIN

Lt Col, AGD

OIC, Casualty Section

Personnel Actions Branch, AGO

Copy Furnished: Central Files

AG 201 and OQMG 293 file of each individual named in par 1.

________________________________________

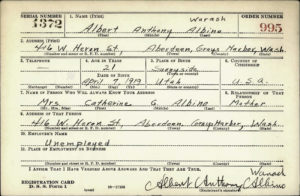

2 Lt. Albert Anthony Albino, P-38H 42-67051, MACR 1428

And so, based on a combination of Public Law 490, under which a Finding of Death had been issued in September of 1945, and Section 9 of the Missing Persons Act, Major Joel and Lieutenant Albino were officially determined to have been killed on the 29th of November, 1943.

The mystery of Lt. Albino’s fate would be definitively solved twenty-nine years later:

But first, some photographs.

Here’s a very pre-war photograph of Albert Albino before he became Lieutenant Albert A. Albino. From The Nine Pound Hammer – the blog of Lt. Albino’s nephew Bob Rini – the image shows his uncle hitchhiking between Aberdeen and Los Angeles during the late 30s or early 40s.

Interestingly, documents in Lt. Albino’s IDPF reveal that his original surname was Guarascio. Born in Sunnyside, Utah, in April of 1919, his parents (mother Catherina and father John) divorced, Catherina then marrying Frank Albino in Washington state. Albert Anthony would use his stepfather’s surname from that time forward.

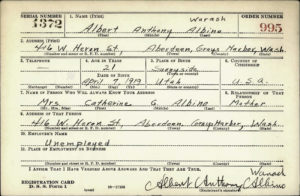

Lieutenant Albino’s Draft Registration Card.

This image from Mr. Rini’s blog shows his uncle by P-38F 43-2050, probably at Paine Field. This aircraft, assigned to the 331st Fighter Squadron of the 329th Fighter Group, was lost due to engine failure on November 26, 1943, 10 miles northwest of Whidbey Island, Washington; pilot 2 Lt. Walter F. Alberty parachuted to safety. Lt. Alberty was killed in action seven months later, when his plane was shot down by an FW-190.

This photo, taken by Sergeant Robert T. Sand, appears in Double Nickel, Double Trouble, and shows 38th Fighter Squadron ground crew members conversing with Lt. Albino (wearing Mae West and sunglasses) in front of his personal P-38 (“Spirit of Aberdeen”) as he describes a just-completed combat mission.

This photo, taken by Sergeant Robert T. Sand, appears in Double Nickel, Double Trouble, and shows 38th Fighter Squadron ground crew members conversing with Lt. Albino (wearing Mae West and sunglasses) in front of his personal P-38 (“Spirit of Aberdeen”) as he describes a just-completed combat mission.

Regarding Lt. Albino, note this entry (see above) in the German List of American Dead in the 1949 Memorandum:

Regarding Lt. Albino, note this entry (see above) in the German List of American Dead in the 1949 Memorandum:

58 – USA – UNKNOWN – Flier

Machine: Lightning

Shot down: 29 November 1943, 1430 hours, Holland

Place of burial: not yet reported

According to Albert Albino’s FindAGrave biographical profile and Traces Of War, his plane crashed at city of Hoogeveen, Holland, at a point adjacent to the station building of the town’s railroad station. Unlike the close attention typically accorded to Allied aircraft losses by the Germans, no efforts were made to investigate the crash site and identify the pilot, due to the depth of the crater from the plane’s impact, and (according to an article by Lydia Tuijnman) the Germans’ greater priority of returning the railroad station to operation to continue the deportation and murder of Dutch Jews.

Well, that’s the summary of the story. Here’s more…

__________