The 1950 publication of Face of a Hero generated attention in several major newspapers, as well as journals of opinion.

Subsequent to a pre-release announcement about the novel in The New York Times on July 7, 1950, reviews of the novel first appeared in The Pittsburgh Press (on July 23), and then in the New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, New York Post, and Philadelphia Inquirer. Subsequently, reviews appeared in The Jackson Sun (Florida), Los Angeles Times, and Washington Post. Within the New York Times, the novel was significant enough to merit attention in the weekly “Books of the Times” column in a piece by William DuBois, and, in the Sunday Book Review, by Herbert F. West.

In the world of magazines, reviews of Falstein’s novel were published between August and September of 1950, with one last hold-out appearing in March of 1951. These publications comprised the Saturday Review of Literature, The Commonweal, The New Yorker, The New Republic, Time, and, Commentary.

Reviewers opinions were positive among all but two of these publications, with similar themes emerging. There were a few criticisms, too, but these were outweighed in number and emphasis by the book’s strengths, especially considering that the book was Falstein’s first novel. The two negative reviews (intensely negative!) appeared in Commentary and Time.

What aspects of Face of a Hero did reviewers focus upon?

The clarity of Falstein’s description of how his novel’s protagonist, Sergeant Ben Isaacs, confronted, endured, and overcame physical fear and, intellectual, or emotional challenges, and emerged intact, emotionally as much as physically.

The characterizations of the foibles and idiosyncrasies of Isaacs’ fellow airmen, soldiers, and officers. While their ethnic and social backgrounds are utterly different from the Sergeant’s, and (inevitably, given the novel’s length) these men are nowhere near as well-“molded” as is Isaacs, as noted by Joe Dever in The Commonweal, these men do emerge as distinct individuals.

The way in which boredom and ennui between combat missions, living conditions at the Tigertails’ base, and, the lives of Italian civilians in the nearby town of “Mandia”, while not the “center” of the novel, are crafted. These events, situations, and people are portrayed with a realism that’s sometimes leavened by humor, sometimes by irony, and other times by quiet anger.

The sense of time that permeates the novel. As suggested by Hollis Alpert in the Saturday Review of Literature, “time” in novel doesn’t underlie the tale in the conventional, taken-for-granted sense of daily life with which we’re familiar. Rather, time – and all significant events in the story – is measured by the irregularly-spaced tick of each combat sortie. Life and its continuation are signified by the passage of completed missions on an allegorical clock with gradations from 1 to 50.

The use of words: Some reviewers remarked about the frank, coarse, and uninhibited language spoken by the novel’s characters, which – I suppose by the standards of public acceptability during the mid-twentieth century?, was – then – rather shocking. In 2022, alas, it’s not shocking at all, or enough.

The two negative reviews of the novel are interesting in their own ways, albeit neither reviewers’ comments – that of Nathan Halper of Commentary, and, that of Time magazine’s anonymous critic – seem to actually focus on the novel as a novel; as a story; as fiction inspired by fact; as a tale with an underlying theme and a beginning, middle, and conclusion. Rather, their criticisms are motivated by highly specific and deeply-held political and social beliefs. There’s nothing wrong with a critique from such a perspective. There is, however, something wrong with a critique from only such a perspective.

In Commentary, Nathan Halper’s understanding of Falstein’s novel seems to be limited to the perspective of his own experiences in the military. He views Face of a Hero as a long, elaborate, and “hypersensitive” gripe about life in the armed forces, casting Ben Isaacs – who throughout the novel is a refreshingly unselfconsciously identified Jew – as a “victim spokesmen”.

The comments of Time’s unknown reviewer strangely parallel those of Halper, but this person is more vehement in criticisms of Falstein’s novel, which seem to have an air of resentment: He deems the book a “grouser’s eye view of the war in the air,” with toss-away-dismissive-comments that Falstein received the Air Medal and “added a couple of clusters to it.” And, in not-so-oblique language obviously referring to Ben Isaac’s identity as a Jew, deems the protagonist “a congenital soul searcher, as much at war with his neurotic self as with Nazi Germany.”

Jumping ahead sixty-four years to 2015, we come to David Margolick’s 2015 Wall Street Journal essay “Inventing the War Novel,” a review of Leah Garrett’s 2015 study Young Lions: How Jewish Authors Reinvented the American War Novel. In Mr. Margolick’s thoughtful and pithy discussion of Dr. Garrett’s work (Louis Falstein is mentioned only in passing) he touches upon Louis Falstein’s novel in the cultural and historical context of the late 1940s. The Second World War having ended only a few short years before, those postwar years represented a literary interlude when a group of war novels featuring identifiably Jewish protagonists and characters in a proud, positive (or, at least neutral) context emerged into public consciousness. These works reflected such themes as Jews in American society as a whole, and, Jewish service in the military in particular, and, the Shoah (though the term wasn’t used at the time). Of course, given the tenor of the times, it’s unsurprising that some of the novels mentioned in Mr. Margolick’s essay (such as Irwin Shaw’s The Young Lions – the film’s ending is astonishingly different from the novel’s bitter conclusion) also openly focus on antisemitism in the military, while others convey a sense of uncertainty and ambivalence about the “place” of Jews in the United States. Which, in 2022, is incrementally returning.

While I fully appreciate the strength of Mr. Margolick’s insights, I strongly take issue with his statement suggesting that the military service of American Jews in the Second World War was motivated in equal parts by the desire to serve their country, and, “…to save the Jews of Europe.”

With the latter I do not agree.

While this assertion might seem strangely incongruous in a blog about Jewish military service – thus far primarily focused on the Second World War (!) – alas, I’ve come to believe this was so. While nominal awareness of the predicament and fate of the Jews of Europe surely existed – to a greater or lesser degree among American Jewish soldiers – for the very great majority this was never the central or animating force for their military service, a take-away I’ve arrived at from extensive historical research, correspondence, and many interviews. (On the other hand, while it’s impolitic to say in late 2022, this was certainly a major motivation for the military service of Jews in the Soviet Army, on a level typically direct and personal. Enough said for now.) It would be very comforting to think otherwise, but to believe so this would entail perceiving and romanticizing the past – a then imaginary past – through the eyes of the present.

And so, “this” post: It’s comprised of reviews of Face of a Hero, some of which are accompanied by images of the original “print” review itself. Each review is headed by a line or two (or three?) from the review itself, to give a quick literary “flavor” of the piece. The reviews are presented chronologically, the first being the New York Times’ announcement of the publication of Face of a Hero, and the last Nathan Halper’s review from Commentary.

The reviews are:

July 7, 1950, The New York Times, Books – Authors (news item)

July 23, 1950, The Pittsburgh Press, John D. Paulus, Books in Review, “Soldiers of Different Nationalities Write Three Similar Books – Reveal That Men In Battle Fight Each Other and Themselves at Same Time“

August 17, 1950, The New York Times, William DuBois, Books of The Times

August 19, 1950, Saturday Review of Literature, Hollis Alpert, “Fifty Missions“, FACE OF A HERO. By Louis Falstein. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co. 312 pp; $3

August 20, 1950, The New York Times Book Review, Herbert F. West, “With Death As a Co-Pilot“, FACE OF A HERO. By Louis Falstein. 312 pp. New York, Harcourt, Brace & Co. $3

August 20, 1950, Chicago Daily Tribune, Victor P. Hass, “A Good Novel in Spite of Its Obscenities“, FACE OF A HERO,” by Louis Falstein. [Harcourt, Brace. $3.]

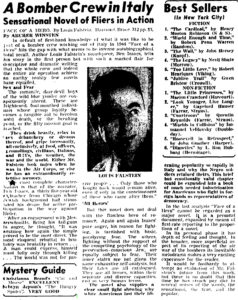

August 20, 1950, New York Post, Archer Winsten, “A Bomber Crew in Italy – Sensational Novel of Fliers in Action“, FACE OF A HERO. By Louis Falstein. Harcourt, Brace. 312 pp. $3

August 20, 1950, The Philadelphia Inquirer, “Saga of Warplane Crew“

August 21, 1950, Time, “Off the Target“, FACE OF A HERO (312 pp.) Louis Falstein – Harcourt, Brace ($3).

August 25, 1950, The Commonweal, Joe Dever, Books, “Face of the Hero“, Louis Falstein. Harcourt. $3.

August 27, 1950, The Jackson Sun, W.G. Rogers (The Associated Press), “10 Men In Liberator Live Furious Life“, FACE OF A HERO. By Louis Falstein. Harcourt, Brace and Co.; $3.00.

September 3, 1950, Los Angeles Times, “Hero’ Finds Triumph in Losing Fear“, FACE OF A HERO. By Louis Falstein. Harcourt, Brace: $3.

September 3, 1950, The Washington Post, “War in the Air“, FACE OF A HERO. By Louis Falstein. Harcourt, Brace. 312 pp. $3.

September 16, 1950, The New Yorker, BRIEFLY NOTED – FICTION, FACE OF A HERO, by Louis Falstein

October 2, 1950, The New Republic, David Davidson, “FIFTY MISSIONS“, FACE OF A HERO, by Leo [sic!] Falstein (Harcourt, Brace; $3).

March, 1951, Commentary, Nathan Halper, “The Army Stereotype Again“, FACE OF A HERO. By LOUIS FALSTEIN – HARCOURT, BRACE. 312 pp. $3.00.

And:

December 24, 2015, Wall Street Journal (Online), David Margolick, “Inventing the War Novel“

________________________________________

Books – Authors

The New York Times

July 7, 1950

A first novel by Louis Falstein, dealing with the 15th Air Force in Italy,

will be issued by Harcourt, Brace on Aug. 17. …

Only three books are being issued today. Dorrance & Co. of Philadelphia is issuing at $2.50 “The Doctor Takes a Farm,” by Jeff Minckler, M.D., a collection of humorous poems about farm life. The book is illustrated by Jack Fruitt. Columbia University Press has at $5.50 “Dramatic Essays of the Neoclassic Age,” which is edited by Henry Hitch Adams and Baxter Hathaway. It is a collection of forty-four essays dealing with the drama. Also from Columbia, there is a second edition of “Psychiatry for Social Workers,” by Lawson G. Lowrey, M.D. It sells for $4.50.

Lionel Gelber, author of “Peace’ by Power” and “The Rise of Anglo-American Friendship,” has a new book on Macmillan’s list scheduled for July 25 publication. “Reprieve From War – A Manual for Realists” presents a summing up of relations between East and West and of current conditions in the Western bloc and what to do about them.

“The Star of Glass,” a novel by Ann Birstein, will be published on Sept. 5 by Dodd, Mead. It is a story about a Brooklyn girl who takes a job as secretary in a synagogue. The manuscript, submitted while Miss Birstein was a senior at Queens College, was unanimously chosen as the winner of the 1948 Dodd, Mead Intercollegiate Literary Fellowship Contest.

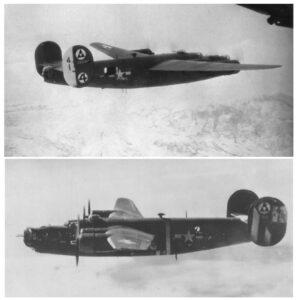

A first novel by Louis Falstein, dealing with the 15th Air Force in Italy, will be issued by Harcourt, Brace on Aug. 17. Entitled “Face of a Hero,” the story presents the crew of a B-24 as they work toward their fiftieth mission.

________________________________________

BOOKS IN REVIEW

Soldiers of Different Nationalities Write Three Similar Books

Reveal That Men In Battle Fight Each Other and Themselves at Same Time

By JOHN D. PAULUS

The Pittsburgh Press

July 23, 1950

… Ben’s reasons lay in his racial background,

in the six million Jews that the Nazis had killed,

in the years of torture his people had endured.

At the end – just three of the “dream crew” are left to fly a mission.

Their dreary role in the war is done.

Theirs is the fight against weariness, boredom, fear, and panic.

Theirs is a life of raw courage, primitive instinct, and constant remorse.

If a Third World War should engulf us millions of men and women in all parts of the globe will be taking part in terrible and perhaps hopeless battle.

If a Third World War should engulf us millions of men and women in all parts of the globe will be taking part in terrible and perhaps hopeless battle.

While fighting against each other they will also be fighting inside themselves, for this seems to be characteristic of all soldiers in all periods of time, judging by three interesting, vital and timely books I have just read.

One is written by an American soldier, one by a German and a third by a Japanese.

They are remarkable in many ways and I wish it were possible for all of you to read these books together.

However, only one is available to the public: now, “Beyond Defeat,” by Hans Werner Richter.

The other two. “Face of a Hero,” by Mr. Louis Falstein, and “Long The Imperial Way,” by Hanama Tasaki. will not be released until mid-August, but advance copies we have received enable us to bring you combined reviews, which follow:

FACE OF A HERO, by Louis Falstein

This is the book by the American. The hero is Ben Isaacs, a gunner in a bomber that attacked Ploesti. Vienna, and other “prime targets” in the war against the Nazis in Europe.

It is a rough, rugged, naked book. It is shocking and startling. It rocks your senses and your emotions. It makes you hate war and everything about it.

Ben was sent to Italy as a member of the crew of a B-24. a bomber that helped shower the enemy with fire and explosive. There was Pennington, the dream pilot who wanted to be a fighter-pilot: Kowalski, the handsome co-pilot who was really no flier at all; Dula, the half-Polish, half-Irish boy from Pittsburgh who wanted to be ALL-Irish; Poat, the fat one; Martin, Kyle, Trent, Ginn, and Fidanza.

The last-named was a tiny man – a ball-turret runner who went back to the land of his forefathers to die.

These 10 men started out together, hoping to remain “the dream crew” of the Air Force. They would complete their 50 missions in victory and would return home for the medals, parades, and bond-selling tours.

But war takes its ghastly toll.

The horrors of the air war are told by Author Falstein without false drama, without sentimental camouflage, without any trace of bitterness or remorse.

This is what the fliers did, he says. and he tells us their story with honesty fidelity – yes, sometime with cruelty, naked horror, and painful defeat.

Kowalski was washed out after Pennington was forced from the ship for being too much of a prima donna. Fidanza was killed by a ricocheting piece of shrapnel. Poat was lost somewhere over Rumania. Others of the “dream crew” went off with “battle fatigue,” “shot nerves,” and terrible injuries as the result of landing a giant bomber on her belly when the engineer miscalculated the gas supply.

Ben Isaacs tells the story of 10 Americans who flew bombers over Hitler’s Europe. Each had his reason for doing so; Ben’s reasons lay in his racial background, in the six million Jews that the Nazis had killed, in the years of torture his people had endured.

At the end – just three of the “dream crew” are left to fly a mission. Their dreary role in the war is done. Theirs is the fight against weariness, boredom, fear, and panic. Theirs is a life of raw courage, primitive instinct, and constant remorse.

Hardly a page goes by which does not contain a dirty word – and for this reason, we warn you to keep the book out of the hands of youngsters.

It will be published Aug. 17 by Harcourt Brace.

________________________________________

Books of The Times

By WILLIAM DU BOIS

The New York Times

August 17, 1950

… “Face of a Hero,” by Louis Falstein,

a novel of the Fifteenth Air Force in World War II,

might well have been one of the finest explorations of that, by now,

faintly tarnished conflict,

if Mr. Falstein had remembered his audience.

**********

… At times (when Ben is sympathizing with refugees in an Italian concentration camp,

or cursing discrimination within his own army)

one feels that the author is trying to write two novels at once, and muddling his effects. …

There have been few war novels that were more deeply felt than this.

There have been many that were better planned,

many that identified the reader more closely with both cast and background.

STEVENSON, in one of his many essays on the art of fiction, remarked that the successful novelist does more than affect his reader – he affects him precisely as he wishes. Stevenson himself (as George Moore remarked, in one of his many essays on writing) was one of the most accomplished technicians of his day; but; (in Mr. M.’s opinion, at least) he never really wrote a book – unless it was “Treasure Island.” … Obviously, the two points of view are poles apart: on the one hand, the careful craftsman who spends a morning establishing an attack, polishing a page of significant dialogue, setting the signboards for a climax to come; on the other, the composer who strikes his keyboard at random and lets the melody seek its own level. The two volumes up for discussion today are both cases in point.

STEVENSON, in one of his many essays on the art of fiction, remarked that the successful novelist does more than affect his reader – he affects him precisely as he wishes. Stevenson himself (as George Moore remarked, in one of his many essays on writing) was one of the most accomplished technicians of his day; but; (in Mr. M.’s opinion, at least) he never really wrote a book – unless it was “Treasure Island.” … Obviously, the two points of view are poles apart: on the one hand, the careful craftsman who spends a morning establishing an attack, polishing a page of significant dialogue, setting the signboards for a climax to come; on the other, the composer who strikes his keyboard at random and lets the melody seek its own level. The two volumes up for discussion today are both cases in point.

One, “Face of a Hero,” by Louis Falstein, a novel of the Fifteenth Air Force in World War II, might well have been one of the finest explorations of that, by now, faintly tarnished conflict, if Mr. Falstein had remembered his audience. The other, “Night Without Sleep,” by Elick Moll, a straightaway movie scenario backhanded into novel form, is a made-to-order guignol that keeps the audience in mind from the first breathless paragraph. Moore would have given Mr. Falstein an A for effort, at the very least Stevenson would certainly have tapped Mr. Moll for Bones, without more ado. Both novels are recommended highly by the present observer – with reservations noted below.

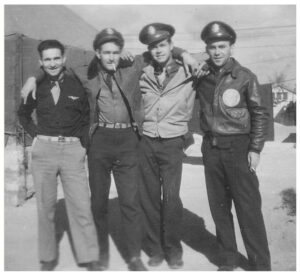

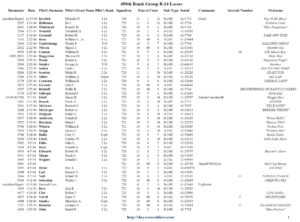

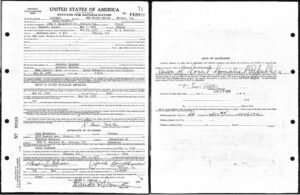

“Face of a Hero,” like so many books that have preceded it, is written from the heart out. Like his narrator-hero, Mr. Falstein has poured his own bitter knowledge into each page. Like Ben, the 35-year-old tail-gunner who sweats out his fifty missions and comes out alive and reasonably whole, he served with a bomber group on that same front in Italy, earning that knowledge the hard way. Like other war novels of World War II vintage, he has concentrated on a cog in the juggernaut – in this case, the ten-man crew that brings the Flying Foxhole from the States to an airstrip at the tip of the Italian peninsula. Just how that ten-man team is welded into a single unit in the crucible of conflict, just how it maintains its unity until bad luck overtakes and demolishes it, and just how the surviving members are destroyed one by one (until only Ben and one half-crazed navigator remain) make up the substance of the novel.

Meditations on War

“War,” says Ben, “contrary to the notions of some doddering old fools, was not a normal pursuit of man. It was the most degrading, unnatural and abnormal pursuit ever foisted upon man. And yet, there was Hitler, and you had to fight. I felt guilty because I too became a victim of the survival cult so prevalent among men who flew missions. Survival, fifty missions, was the goal – not the winning of the war. But survival for its own sake was a corrupt thing, like living only for the sake of living.” Ben, in many ways (including the thoughts just quoted) is an odd sort of protagonist – though he is a fluent enough mouthpiece for Mr. Falstein’s ideas, and ideals.

Because of his age, he is “Pop” to his crew-mates; because of his race, he is the butt of the anti-Semitism that is by now de rigueur in every other problem novel, war or non-war. Unable to control his fear once he is over a target, he is virtually useless as a gunner on his early missions – though he describes these strikes (from Vienna to Ploesti, with side-trips to Genoa, Munich and Yugoslavia) in a hard, stinging prose that few readers will forget. And yet, as he hardens to his job, Ben learns to pull his weight. As the book ends he has found himself, in more ways than one. He has risen above blind terror and futility alike – and, though he has no easy answers for the future, one feels sure that he will face that future unafraid.

It is unfortunate that Mr. Falstein’s pattern is self-defeating. After he has described the Flying Foxhole’s first, breath-taking mission in such merciless detail (that chapter alone makes the novel well worth the price of admission) he must repeat a theme with variations – and he lacks the bravura touch to keep his novel from stuttering here and there. Also, he has chosen to wander too far from his air-strip. At times (when Ben is sympathizing with refugees in an Italian concentration camp, or cursing discrimination within his own army) one feels that the author is trying to write two novels at once, and muddling his effects. Finally, it’s plain too bad that “Face of a Hero” is bound to suffer from the law of diminishing returns – which operates in the literary market-place even more predictably than in other markets. There have been few war novels that were more deeply felt than this. There have been many that were better planned, many that identified the reader more closely with both cast and background.

Story of a Drunkard’s Morning-After

Mr. Moll’s “Night Without Sleep” is the sort of novel that will always find a public, no matter what’s happening in Asia, Washington or Moscow. Dealing with a drunkard’s morning-after (in this case, a take-it-or-leave-it-alone drunkard who begins his day after a hundred per cent blackout) it explores, and explains, a dilemma that is all too familiar to many citizens in this age of jitter-and-fritter. The reconstruction of the hours, and the lifetime, preceding that epic blackout give the author an excuse to dance a rigadoon on a story-line as taut as Ringling Brothers’ high wire.

The results are just as spine-tingling, as Mr. Moll’s hero-heel threatens to take a header at every other page. When murder crawls into the act, and rides his shoulders like an antic clown, the suspense is, at times, unbearable.

It should be noted, of course, that all this is the stuff of which good pictures are made – and no more. Mr. Falstein’s novel (which comes from the heart) is literature – when its author is at the top of his form. It is unfortunate that the scenarist could not have traded a little of his know-how for a little of the airman’s experience.

FACE OF A HERO. By Louis Falstein. 312 pages. Harcourt, Brace. $3.

NIGHT WITHOUT SLEEP. By Elick Moll. 212 pages. Little, Brown. $2.75.

________________________________________

With Death As a Co-Pilot

FACE OF A HERO. By Louis Falstein. 312 pp. New York, Harcourt, Brace & Co. $3

By HERBERT F. WEST

The New York Times

August 20, 1950

… “Face of a Hero” is, in my opinion,

the most mature novel about the Air Force that has yet appeared.

**********

… Mr. Falstein makes them more human, and so more interesting;

here one will learn, if he really wants to know,

what the term “fifty missions” really meant.

WRITTEN from the enlisted man’s point of view, “Face of a Hero” is, in my opinion, the most mature novel about the Air Force that has yet appeared. The author, and aerial gunner with the Fifteenth Air Force in Italy, has told his apparently autobiographical story dispassionately and honestly. He has produced a book that is both exciting and important.

WRITTEN from the enlisted man’s point of view, “Face of a Hero” is, in my opinion, the most mature novel about the Air Force that has yet appeared. The author, and aerial gunner with the Fifteenth Air Force in Italy, has told his apparently autobiographical story dispassionately and honestly. He has produced a book that is both exciting and important.

The focus of the novel is a ten-man crew, “a little universe revolving in its narrow orbit,” flying its fifty missions from an Italian field in a B-24. It is not a watch-perfect crew. Under normal conditions it sometimes acts unsmoothly, makes mistakes. It is no more than the sum of its human parts.

Perhaps the most effective chapter in the novel describes the crew’s first mission over Vienna, one of the most deadly assignments of the war. The reader has a spine-tingling sense of participation, from the first airborne moment to its flak-ridden return.

At the end of that mission, says the narrator, “all ten of us piled from the ship. We scrambled down and without looking back we ran in our heavy clothing away from the ship in all directions. Then, when we felt safely distanced from our plane, several of us fell down and kissed the barren, parched soil and then got up and ran again.”

THE crew’s missions include bomber runs to Regensburg, Munich, Brod, Ploesti, Innsbruck, the Brenner Pass, Ora, Miskolc, the Po Valley and Osijek (names not exactly nostalgic to thousands of air veterans). The crew gets frostbitten at 20,000 feet, flies blind in deadly fog, blunders with its guns and bombs, sweats with fear, suffers wounds and deaths. Incidents include a crash-landing, a suicide in the air, the burial of a comrade, and madness, but the men stick it out until only two of the original ten are left.

Dooley, the flight engineer, and Ben Isaacs, the narrator of the story, who is called “Pop” because he is 35 years old.

Ben, the Jewish gunner, is fighting a personal war. An old man in Italy reminded him: “Do you know, son, six million of your brothers and sisters are slain. Remember that, my son, when you drop those bombs on him.” The other thing that keeps him going is his fight with fear. On his fiftieth mission, with which the book ends, he wants to shout, “You did not quit, you did not quit, you did not quit.”

**********

Entombed

I caught a glimpse of a bomber exploding; the front half of the ship nosed down and spiralled slowly earthward, turning crazily, like a long piece of paper dropped from a tall building. The other half of the fuselage appeared settled in space momentarily. Then it too floated down in a slow spiral. No chutes came out of that ship. No man. – Louis Falstein in “Face of a Hero”.

**********

He had won the battle of self: “The will had triumphed over emotion, which was represented by vacillation and cowardice.” Ben Isaacs had come to know the ultimate experience, the terrible solitude of a man facing death, and for the first time in his life he was unafraid.

If some readers are offended by the language, which at times is certainly low, Louis Falstein can argue rightly, I think, that this is the way the men in the air force talked, and these are the things they talked about.

The author was also well aware of the way the Army conducted itself in Italy, and says, “What shame could be greater than for a grown-up to stare into the face of a child whose eyes had grown evil and corrupt and all-knowing. Our guilt was so enormous that we could never expiate it.”

This book shows that the wild-blue-yonder boys were not quite as the war-time publicists for the Air Force made them out to be. Mr. Falstein makes them more human, and so more interesting; here one will learn, if he really wants to know, what the term “fifty missions” really meant.

________________________________________

Fifty Missions

FACE OF A HERO. By Louis Falstein. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co. 312 pp; $3

By HOLLIS ALPERT

Saturday Review of Literature

August 19, 1950

… and yet there is a freshness that runs through the book,

a quality that makes the familiar material seem new once more.

**********

…He has written as though he alone knows the truth and the actuality;

his narration is compelling, and he writes narrative with grace and simplicity.

**********

…Time is fifty missions, too, and time halts until fifty missions are completed.

And time spent in the air above flak-dotted areas

leaves scars that to be scars do not need to show upon the flesh.

This Mr. Falstein communicates, and since he communicates it honestly and well

he is a writer to be taken seriously.

IT IS five years since the end of World War II and already our novelistic returns on the conflict seem to be about in. The books have had varying fates from a long tenure on best-seller indexes to almost complete neglect. It is no help for a novel that comes along now to have run the gauntlet of comparison with a handsome list of others: the names of Hegen, Calmer, Mailer, and Shaw (to take a handy few) stand for well-covered areas of war subject matter and terrain. Only five years, and yet the accolade of “best” war novel has been handed out a dozen times. No need any longer to read another, so the feeling seems to be, as though we are to have only one to remember and recreate the awesome time for us. That no novelist has “caught it all” is made amply clear by Louis Falstein’s “Face of a Hero”. His subject is war, his characters are much the same sort of GI’s we’ve met before, their speech and their thoughts are not startlingly fresh to us, and yet there is a freshness that runs through the book, a quality that makes the familiar material seem new once more.

IT IS five years since the end of World War II and already our novelistic returns on the conflict seem to be about in. The books have had varying fates from a long tenure on best-seller indexes to almost complete neglect. It is no help for a novel that comes along now to have run the gauntlet of comparison with a handsome list of others: the names of Hegen, Calmer, Mailer, and Shaw (to take a handy few) stand for well-covered areas of war subject matter and terrain. Only five years, and yet the accolade of “best” war novel has been handed out a dozen times. No need any longer to read another, so the feeling seems to be, as though we are to have only one to remember and recreate the awesome time for us. That no novelist has “caught it all” is made amply clear by Louis Falstein’s “Face of a Hero”. His subject is war, his characters are much the same sort of GI’s we’ve met before, their speech and their thoughts are not startlingly fresh to us, and yet there is a freshness that runs through the book, a quality that makes the familiar material seem new once more.

Not that it should be a book without fault, or that it should necessarily cause a new flurry of “best” recommendations. Even the hero, Ben Isaacs, we seem to have met before: self-conscious about his “Jewishness”, broodingly aware of why he fights, and set apart a little from the others because of this double awareness. The others in the crew of ten who flew in a B-24 to a base in Southern Italy are hardly distinctive enough for remembering them as individuals, once the book has been put down. Nevertheless “Face of a Hero” remains haunting and powerful.

I think this is primarily due to the richness of feeling with which air war has been rendered by Mr. Falstein. He has written as though he alone knows the truth and the actuality; his narration is compelling, and he writes narrative with grace and simplicity.

The story is sharply limited in outline. This crew of ten must complete fifty bombing missions before their combat duties are over and they can be returned to the United States. What is involved in the term “fifty missions”? The answer is the scope and the meaning of the book; an age, an agony, life in a universe reflecting little but death. Ten men flew the missions to Ploesti, Vienna, and the Riviera beaches; two were able to reach the seemingly impossible number. Along this path of fifty missions are strewn the loss of the other eight. Flak, failure of engines and fuel supply, mental crack-ups, enemy fighter action account for the empty cots in the barracks. It was a dream crew that started out, so they all passionately believed or tried to believe. And when Ben flew his fiftieth he was a stranger, manning a tail gun among nine men whose faces were hardly more than oxygen masks to him.

To make up for the lack of sharp characterization (and it is likely that Mr. Falstein had this for his purpose) there is a universalization of the experience. They must face it in common, the menace cannot be conquered, and they do not shape, they rather are shaped by it, so that after a while even Ben cannot see them as entities other than flight engineers, tail gunners, and navigators. Time looms all important in this kind of existence, and I think the management of this time factor gives Mr. Falstein an affinity with a time-obsessed writer like Virginia Woolf (although their methods are entirely dissimilar, and no comparison, is intended). For time unrolls like a scroll here, and the emotions of a lifetime can be crowded into six hours spent 20,000 feet above the earth. Time is fifty missions, too, and time halts until fifty missions are completed. And time spent in the air above flak-dotted areas leaves scars that to be scars do not need to show upon the flesh. This Mr. Falstein communicates, and since he communicates it honestly and well he is a writer to be taken seriously.

________________________________________

A Good Novel in Spite of Its Obscenities

“FACE OF A HERO,” by Louis Falstein. [Harcourt, Brace. $3.]

Reviewed by Victor P. Hass

Chicago Daily Tribune

August 20, 1950

It is real; it is worth reading. But brace yourself; it is appallingly strong meat.

Anybody who has read almost any of the torrent of World War II combat novels knows that it was fought with men, weapons, and four letter words. Being a reviewer and having read dozens of those novels I had thought that I was pretty much insulated against foul language. “Face of a Hero,” however, rocked me like a medium bomber dancing on flak. Eighty per cent of this novel is made up of the dirtiest, filthiest, most shockingly foul language I have ever seen in print. To me, it is incredible that it ever got into print in the first place and I am leagues from being a prude.

And yet I believe that Mr. Falstein’s novel belongs well up on the list of World War II novels because it is a rather amazing account of what it meant to be an enlisted man in the American air forces during World War II. That it is authentic I do not doubt because Mr. Falstein experienced everything that the men in his story experienced. That makes his novel an important contribution to the literature of the war.

***

But it doesn’t alter the fact that it is studded with dialog so obscene that I hesitate to recommend it to any save the hardiest of readers, while warning even them to keep it under cover if there are children around the house.

That, I think, is a pity because the story of how Ben Isaacs, who had to pull strings to get into combat with the 15th air force in Italy, and who somehow survived 50 missions (many of them over terrible Vienna) is a gripping one. With Ben you watch the men of his crew crack up, become crazed with fear, conjure up a whole catalog of odd complexes, curse, careen drunkenly thru the streets of dirty Italian towns, sleep with a succession of girls, force down acrid coffee and lousy chow in bleak dawns, ride out storms of anti-aircraft fire over dozens of cities with curious names, hate, love, shoot the breeze in endless bull sessions in barracks, perform feats of bravery and still not think of themselves as heroes.

***

It is real; it is worth reading. But brace yourself; it is appallingly strong meat.

________________________________________

A Bomber Crew in Italy

Sensational Novel of Fliers in Action

FACE OF A HERO. By Louis Falstein. Harcourt, Brace. 312 pp. $3

By ARCHER WINSTEN

New York Post

August 20, 1950

… such a marked flair for descriptive and dramatic writing

that the whole crew and indeed the entire air operation

achieve an earthy reality few novels have equaled.

**********

They drink heavily,

relax in sex debauchery or dreams thereof,

and gripe incessantly,

all exclusively,

at food,

officers,

groundlings,

civilians,

Italians,

and B-24s,

the weather,

the war and the world.

Either Mr. Falstein took notes when he was in the Air Corps,

or else he has an extraordinarily retentive memory.

**********

It is a personal document,

expanded by means of first-rate reporting to the proportions of a novel.

In default of firsthand knowledge of what it was like to be part of a bomber crew working out of Italy In 1944 “Face of a Hero” fills the gap with what seems to for intense autobiographical total recall. Author Louis Falstein’s mouthpiece, Ben Isaacs, tells his story in the first person but with such a marked flair for descriptive and dramatic writing that the whole crew and indeed the entire air operation achieve an earthy reality few novels have equaled.

In default of firsthand knowledge of what it was like to be part of a bomber crew working out of Italy In 1944 “Face of a Hero” fills the gap with what seems to for intense autobiographical total recall. Author Louis Falstein’s mouthpiece, Ben Isaacs, tells his story in the first person but with such a marked flair for descriptive and dramatic writing that the whole crew and indeed the entire air operation achieve an earthy reality few novels have equaled.

Sex and Fear

The romantic, daredevil boys of the wild blue yonder are conspicuously absent. These are frightened, foul-mouthed individuals whose group loyalty becomes a tangible aid to heroism until death, or the breaking point, of the fifty mission goal is reached.

They drink heavily, relax in sex debauchery or dreams thereof, and gripe incessantly, all exclusively, at food, officers, groundlings, civilians, Italians, and B-24s, the weather, the war and the world. Either Mr. Falstein took notes when he was in the Air Corps, or else he has an extraordinarily retentive memory.

The most complete characterization is that of the narrator, Ben Isaacs, a thirty five-year old ex-teacher’ from Chicago whose Jewish background had stimulated his desire for active participation in the war against Hitler.

After an engagement with Messerschmitts, firing his tail guns in anger, he thought, “It was amazing how again the simple proved to be the most direct. The most eloquent rebuttal to brutality was brutality in return … A man could express himself most fully only through killing … The world was not for passive people … Only those who fought back would remain alive, even if only in the consciousness of those who came after them.”

‘All Heroes’

But this novel does not deal with the flawless hero of romance. Again and again Isaacs’ pure anger, his reason for fighting, is tarnished with basic, paralyzing fear. The others, fighting without the support of the compelling psychology of the persecution-conscious Jew, are equally subject to fear. Their inner states are not given the same exhaustive self-analysis, but their fates are all catalogued. They are all heroes, within their separate and diverse capacities, and in very human terms.

The novel also supplies a clear small light allowing why white Americans lost their liberating popularity so rapidly In Italy and why the Negro soldiers retained theirs. This brief but emotionally valid chapter could be expanded into a book of much needed indoctrination for Americans who fight in foreign lands as representatives of democracy.

In the last analysis “Face of a Hero” cannot be regarded as a major novel. It is a personal document, expanded by means of first-rate reporting to the proportions of a novel.

In Its personal phase it has depth of feeling and thought. In the broader, more superficial aspect of its reporting of the air war of the bombers its inevitable melodrama makes a very exciting experience for the reader.

It would be foolhardy to attempt an evaluation of Mr. Falstein’s future from his work, but there is no doubt that this time he has struck pay dirt in several senses of the the words, the sensational, the true, and the popular.

________________________________________

Saga of Warplane Crew

The Philadelphia Inquirer

August 20, 1950

… he reaches a new high in his descriptions of the actual bombing missions,

which are made so real that the reader seems to be flying along.

LOUIS FALSTEIN was an aerial gunner during World War Two and was awarded the Air Medal four times and the Purple Heart. Now, in Fare of a Hero, with a natural writing skill and an unusual imagination, he has distilled his experiences and observations into one of the outstanding war novels.

LOUIS FALSTEIN was an aerial gunner during World War Two and was awarded the Air Medal four times and the Purple Heart. Now, in Fare of a Hero, with a natural writing skill and an unusual imagination, he has distilled his experiences and observations into one of the outstanding war novels.

Swift-paced, powerful and vividly realistic, Falstein’s initial effort in the field is the story of a group of fliers – principally the crew of one “fat-bellied Liberator” – in the 15th Air Force in Italy.

The men tire, they crack up, they are killed or commit suicide, until there are only a few of the original crew members remaining. This was the war to the airmen, and Falstein reveals their emotions and feelings and reasoning a, completely as any novelist thus far. Further, he reaches a new high in his descriptions of the actual bombing missions, which are made so real that the reader seems to be flying along. (Harcourt, Brace & Co. 312 pp $3.) F.B.

________________________________________

Off the Target

Time

August 21, 1950

FACE OF A HERO (312 pp.) Louis Falstein – Harcourt, Brace ($3).

… Face of a Hero is less a novel than a first-person recital of discontent;

Ben’s buddies didn’t know what they were fighting for,

the B-24s weren’t fit to fly,

some of the officers were deadweights,

the G.I.s behaved crudely with Italian civilians,

the Red Cross girls dated officers only.

**********

… It would be hard to guess from Face of a Hero that the war was won,

that Hitler was rubbed out,

that millions of G.I.s knew very well, beneath their gripes, what the score was.

(This image of Time’s book review is from the Magazine Project.)

Face of a Hero is called by its publishers “one of the most powerful and truthful novels to come out of World War II”. It is powerful only if a mixture of bitterness and resentment can be called power, and it is not so much a novel as one grouser’s-eye view of the war in the air. The author is First Novelist Louis Falstein, a gunner who completed 50 missions, won the Air Medal and added a couple of clusters to it. His hero and narrator is Gunner Ben Isaacs, a congenital soul searcher, as much at war with his neurotic self as with Nazi Germany.

When Ben’s B-24 crew arrived in Italy, he was 34, small, thin-fingered and a wearer of glasses. He knew himself to be only a fifth-rate gunner, and because he was a Jew, he felt that the rest of the boys had never accepted him. At 15, he had come from the Ukraine, where he had seen pogroms with his own eyes. Ben had become a gunner because he hated Hitler and understood the necessity for defeating him. He was nonetheless scared to death of combat – and honest enough to admit that, while it had been easy to hate fascism, “the difficulty had been in bridging the distance between belief and action.” His self-knowledge was accurate. Ben on his first mission was a praying, vomiting passenger.

Like millions of other civilians-turned-soldiers, Ben Isaacs became hardened to combat and began to pull his weight. But his ingrown, slit-focus view of life kept him on sour emotional rations. Face of a Hero is less a novel than a first-person recital of discontent; Ben’s buddies didn’t know what they were fighting for, the B-24s weren’t fit to fly, some of the officers were deadweights, the G.I.s behaved crudely with Italian civilians, the Red Cross girls dated officers only.

It seems fairly clear that not only Ben but Author Falstein, too, is out to handpick an ugly side of the war and call it the whole picture. It would be hard to guess from Face of a Hero that the war was won, that Hitler was rubbed out, that millions of G.I.s knew very well, beneath their gripes, what the score was.

________________________________________

Books

Face of the Hero. Louis Falstein. Harcourt. $3.

Joe Dever

The Commonweal

August 25, 1950

Ernest Hemingway excepted,

only an aerial combat man could write this story as it must be written –

out of the looseness of his bowels and the stutter of his teeth.

And only a writer with some kind of spiritual insight could hold it all together.

**********

… Because they were, most of them, undedicated, not knowing why they fought, not caring why,

Ben Isaacs knew their courage was exceedingly admirable.

Their courage had to feed on the vaguenes of drive-in theatres,

cokes and hamburgers and some wisp of a girl wearing their silver wings at the USO.

**********

… As Falstein puts it: “…a man does not weep like a child.

A man’s sobs are the sounds of anguish and despair.

They come to the surface with the difficulty of dry heaves.”

If Hell has a center it could be at the Laredo aerial gunnery school in mid-summer. If Heaven is on earth at times, it could have been at Laredo when the gunners wore their wings and sauntered around the field in their jaunty green flying suits.

You too can be an aviation cadet, providing you do not wash out and go to gunnery school at Laredo, Texas; Tyndall Field, Florida; Kingman, Arizona; Las Vegas, Nevada.

In all these places you get to know incessant heat, the clack of skeet-shot, the chatter of thirties, the thunder of fifties, the relentless moan of the bombers approaching, circling or dwindling.

You too could fly, if you were not a camp reporter gathering news in the air-conditioned bowling alley at Laredo – seeing the gunners come and go, writing little releases which appeared in the Kansas City Star or the Charlestown News.

Sgt. Fred Cluney pinned on his bright new gunner’s wings today after graduation ceremonies at Laredo, Texas. “This is the day I’ve been waiting for,” he declared, before joining an operational training unit in El Paso.

Sgt. Cluney, who hopes to slash at the Nazis from a ball turret, is the son of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Cluney of 1740 Bunker Hill St. His brother Edward is a Petty Officer serving with the Navy, somewhere in the South Pacific.”

The day he was waiting for. Yes, and if his aunt wore trousers, she would be his uncle.

Then at Lowry Field, later, where they pooled the returnee gunners, you took them to the Denver Press Club and helped them ease up with bourbon, gin, beer and all three mixed if necessary. (Obscenity the Air Corps, obscenity all officers and all civilians, obscenity everything but us and those we like because of a smile, a drink, an embrace in the hallway.)

“You’re a writer. For Christ’ sake write it all dawn. Tell our story, tell the whole obscenity story.”

But you’d have to be a combat gunner to tell that story, to get behind the too-many missions and the too many medals. To know the why of sobbing at midnight on the way back to the barracks – the tears and the profanity and the chambering – the vomiting at the Shirley-Savoy on Saturday night.

LOUIS FALSTEIN, an ex-combat gunner, has told this almost impossible story. Impossible, became it is difficult to make fictionally credible the feelings and the actions of men who flew the B-24’s – those whooshy boxcars – and all combat airplanes over the guns of the enemy in broad daylight. It is almost impossible to extract value and dedication out of men at whom the Nazi gunners have thrown everything but their chamber pots over incredible, nightmarish targets like Ploesti and Vienna.

Ernest Hemingway excepted, only an aerial combat man could write this story as it must be written – out of the looseness of his bowels and the stutter of his teeth. And only a writer with some kind of spiritual insight could hold it all together.

Those of us who have thought about writing a gunner’s novel further recognize the complex technical problems. Once you have done a vivid, powerful, comprehensive job on one aerial combat mission – say the first of 50 – what are you going to do with the other 49?

In Sergeant Ben Isaacs, the gentle, thirtyish American Jew with a steely dedication to the destruction of Fascism, we have Louis Falstein’s answer to the problem of the short story material that must be sustained in a novel of at least three hundred pages.

Through Ben’s eyes we see that the nightmare life of the heavy bombardment mission does not end with the screech of brakes after the flappy monsters have lumbered home empty to Italy, free of the Focke-Wulfs and the flak. The story of Ben’s sustained dedication – which might so easily have become corny – amid the desolation of the barracks and the fear-ridden, lust-ridden, homesick, tippling, brawling gunners, provides the t-bone of the story. The furious and too-familiar cinema of aerial combat is tossed salad.

Mr. Falstein writes with an artlessness which at first seems uninviting, as strangers in the middle of a conversation seem uninviting, until you’ve listened a while.

“It was still dark when all ten of us assembled near our ship in the dispersal area. The Flying Foxhole was all shiny and silvery with a taut, unblemished aluminum skin. Nevertheless I was struck by a change in her appearance. It was not a tangible change. The plane suddenly seemed angry, like a predatory bird.”

Falstein’s insight into the tortures, hopes and anxieties of the gunners is continually arresting. There is unfailingly – the Whitmanesque compassion: “I am the man, I suffered, I was there.”

If you’ve been in the Air Force, you’ll know how genuine Falstein’s air-ground world is. You’ll know it is all so genuine even if you’ve never left your mother’s lap. The speech:

“…even the birds are walking.”

“…you’re obscenity well told!”

“…rough as a cob.”

All the sulphurous wit, the glib cynicism, the swaggering disguises of gangling boys who had to become supermen over Ploesti, Vienna, Regensburg, Berlin. Because they were, most of them, undedicated, not knowing why they fought, not caring why, Ben Isaacs knew their courage was exceedingly admirable. Their courage had to feed on the vaguenes of drive-in theatres, cokes and hamburgers and some wisp of a girl wearing their silver wings at the USO.

If my name were Brentano or Harcourt Brace, I would give away many copies of this book to the returnee gunners I knew in Laredo, Denver, Phoenix. It would make them very happy to know that the whole monstrous business had been set down in a book – a book that explains why teen age gunner veterans beat up three waiters and sob in the darkness on the way up the barrack stairs. As Falstein puts it: “…a man does not weep like a child. A man’s sobs are the sounds of anguish and despair. They come to the surface with the difficulty of dry heaves.”

You close the book reluctantly, gratefully wanting to say: “never, never again.” But a wind is rising in Korea and already somebody way up top may be squinting at reactivation plans for Laredo, Tyndall, Kingman, Las Vegas.

Tail gunner to pilot. Over. All over again.

JOE DEVER.

________________________________________

10 Men In Liberator Live Furious Life

FACE OF A HERO. By Louis Falstein. Harcourt, Brace and Co.; $3.00.

Reviewed by W.G. ROGERS, the Associated Press.

The Jackson Sun

August 27, 1950

… These men live for us with a furious vitality;

where there is passion, it is grand passion,

whether in the awesome intimate sessions in which the flyers guess at the chances of survival,

in the blood-curdling moments when they battle to survive,

or in the quick rest periods when they take their wine and women

with a fierce and maybe final frenzy.

Passages like this, at which you laugh and weep,

are the finest World War II writing done so far by any American author.

Fifty missions … that’s the rugged prospect facing 10 men who fly a fat-bellied Liberator on bombing raids from their Italian base.

Fifty missions … that’s the rugged prospect facing 10 men who fly a fat-bellied Liberator on bombing raids from their Italian base.

Ben Isaacs, who as a youngster had fled to America from persecution in Europe, tells this stirring story. Almost 39, Ben is “Pop” to his fellows Poat, Fidanza, Ginn, Dula, Trent, Pennington and the rest. Oh, they’d be heroes, they joked while training; they’d show Hitler. Hitler had something to show them. On their first flight, they discovered flak, the soundless puffs that blossom blackly in the midst of the formation, jolting their “Flying Foxhole,” rattling a deadly rain along its shiny sides, punching a hole in the hydraulic system. They’re scared. One man is scared of his shadow, and it, too, is scared; they’re so scared they can’t work their fingers, they vomit their fear, one uses his gun on himself, one tries to jump out

They grow hardened, yet still later the awful fright returns as they drive off fighters or feel blindly through the clouds. The regulation assignment of 50 missions always hangs over them; though one counts on his Bible, another on his caul, and others on their lucky pieces, luck fails them one by one. Ben knows why he’s in it, but the others haven’t this consolation; as a native says, the Americans are “armed magnificently … but spiritually they are naked.”

There is, perhaps, some spiritual nakedness about the novel, too, but it is possessed of sterling virtues. These men live for us with a furious vitality; where there is passion, it is grand passion, whether in the awesome intimate sessions in which the flyers guess at the chances of survival, in the blood-curdling moments when they battle to survive, or in the quick rest periods when they take their wine and women with a fierce and maybe final frenzy. Passages like this, at which you laugh and weep, are the finest World War II writing done so far by any American author.

________________________________________

‘Hero’ Finds Triumph in Losing Fear

FACE OF A HERO. By Louis Falstein. Harcourt, Brace: $3.

Los Angeles Times

September 3, 1950

To Ben it was the youngsters in his barracks who were the real heroes

and “most of them fought on sheer guts,

with hardly any knowledge of the causes for the war.” …

**********

… It arrives fairly late in the succession of war novels,

but it is as powerful as the best,

for it gains in depth what it sacrifices in scope

and shows a portrait with the shadows and smudges and few highlights untouched.

Traditional heroes were always men of exceptional valor and fortitude, models of noble qualities, and often of divine descent. In our own time, the hero has become the typical man caught in the clutch of circumstance, altogether human in stature, capacity and ability.

Traditional heroes were always men of exceptional valor and fortitude, models of noble qualities, and often of divine descent. In our own time, the hero has become the typical man caught in the clutch of circumstance, altogether human in stature, capacity and ability.

The “heroes,” for instance, in Louis Falstein’s remarkable novel are men “huddled together momentarily against the unknown … bound ever so precariously only by mutual fears.” They make up the crew of a Liberator bomber stationed in Italy during the last half of 1944. Their story is told by Ben Isaacs, tail gunner, all of 35 and therefore Pop and Old Man to the rest of the bomber crew.

Survival Is Goal

“Survival, 50 missions, was the goal – not the winning of the war,” for these men, observes the narrator, who adds, “Survival for its own sake was a corrupt thing, like living only for the sake of living.” Ben’s case was somewhat different because he was a Jew, had endured persecution as a youth in Europe, and at least had a personal reason for fighting. But he, too, shared then: fears and fatalism, panic and fatigue, despair and cynicism, degradation and loneliness in the constant presence of death.

To Ben it was the youngsters in his barracks who were the real heroes and “most of them fought on sheer guts, with hardly any knowledge of the causes for the war.” Ben wondered what made them persevere. Was it an innate courage? “But courage was a flower that blossomed slowly. One could learn and gather courage. What was it, then? Approval? Was it possible for men to go out and die because others died and because their environment approved of and demanded such acts?”

Triumph Achieved

Ben’s own personal triumph and jubilation stem from a self-conquest over vacillation and cowardice, over the fear of death. Realization only comes with the final mission and it comes with no sense of glory but simply of feeling that “it does not matter,” of becoming unafraid.

There are no spectacular men in this book, but they are all men seen at close range in their small, distorted, violent world of war, in barracks and airborne. All the elements of fiction are there – suspense, action, incident, characters – but the narrative seems carved straight from experience itself. It arrives fairly late in the succession of war novels, but it is as powerful as the best, for it gains in depth what it sacrifices in scope and shows a portrait with the shadows and smudges and few highlights untouched.

MILTON MERLIN

________________________________________

War in the Air

FACE OF A HERO. By Louis Falstein. Harcourt, Brace. 312 pp. $3.

The Washington Post

September 3, 1950

… This book tells it all with a vivid feeling of “being-there-ness”

that this reviewer has rarely come upon before.

The narrator is the tall-gunner, who, like the rest of the crew, is just an ordinary Joe.

All of them want only to complete 50 bombing missions from their station at Eboli

(where Christ is said to have stopped) and then so back to the States.

As it happened, the first of the 50 was almost the last, too,

and in Mr. Falstein’s hypnotic telling the reader goes through hell with the crew.

Mr. Falstein has written one of the strongest, truest and finest novels of World War II. …

ANYONE who wants to know what war is like for an airman has merely to read this book. It will tell him, as powerfully as the printed word can, what it felt like to be in a Liberator on a bombing mission, driven by duty but gripped by fear, elated when the bombs were away but seared to death when the flak began hitting, and limp with exhaustion when the plane came in on a wing and a prayer. This book tells it all with a vivid feeling of “being-there-ness” that this reviewer has rarely come upon before.

ANYONE who wants to know what war is like for an airman has merely to read this book. It will tell him, as powerfully as the printed word can, what it felt like to be in a Liberator on a bombing mission, driven by duty but gripped by fear, elated when the bombs were away but seared to death when the flak began hitting, and limp with exhaustion when the plane came in on a wing and a prayer. This book tells it all with a vivid feeling of “being-there-ness” that this reviewer has rarely come upon before.

The narrator is the tall-gunner, who, like the rest of the crew, is just an ordinary Joe. All of them want only to complete 50 bombing missions from their station at Eboli (where Christ is said to have stopped) and then so back to the States. As it happened, the first of the 50 was almost the last, too, and in Mr. Falstein’s hypnotic telling the reader goes through hell with the crew.

Mr. Falstein has written one of the strongest, truest and finest novels of World War II. His prose style is less experimental than Norman Mailer’s and his picture of men in action not as all-encompassing; but it has an emotional focus and tautness that Mailer’s book lacked.

________________________________________

BRIEFLY NOTED

FICTION

FACE OF A HERO, by Louis Falstein

The New Yorker

September 16, 1950

… he feels himself to be an outsider but which tends to reflect his spirit rather than his anger.

(Harcourt, Brace). A sincere account of the Second World War in Italy, written from the point of view of an American aerial gunner. Though the gunner, Ben, speaks with authority and emotion, he spoils his effect by a persistent air of peevish dignity, which comes mostly from the fact that he feels himself to be an outsider but which tends to reflect his spirit rather than his anger.

________________________________________

FIFTY MISSIONS

FACE OF A HERO, by Leo Falstein (Harcourt, Brace; $3).

David Davidson

The New Republic

October 2, 1950

… another war is on him before he has been able to get his own off the presses.

**********

…In its directness,

in its skill at drawing the reader into sharing the combat experience of the characters,

it is as successful an account of the sky-slogging airman

as Van Van Praag’s Day without End was of the mud-caked foot soldier.

**********

… On a documentary level, however, it is one of the best-told tales of air combat in World War II.

THERE WERE TIMES when a writer could count on his war novel staying current for at least a dozen years. Today, the war novelist who doesn’t want to become suddenly dated must bring out his War and Peace in a form something like an evening newspaper – with flashes, extras and replates. Otherwise, as in the case of Leo Falstein’s warmhearted, honestly-told tale of the Italy-based Fifteenth Air Force, another war is on him before he has been able to get his own off the presses.

THERE WERE TIMES when a writer could count on his war novel staying current for at least a dozen years. Today, the war novelist who doesn’t want to become suddenly dated must bring out his War and Peace in a form something like an evening newspaper – with flashes, extras and replates. Otherwise, as in the case of Leo Falstein’s warmhearted, honestly-told tale of the Italy-based Fifteenth Air Force, another war is on him before he has been able to get his own off the presses.

Where the New War plays a little hob with Face of a Hero is in Falstein’s pre-publication assumption that the dreadful sufferings of our flying men in World War II were to be made worthwhile by the peace, decency and brotherhood which were going to descend on mankind immediately after the last bomb bay was closed. It has not worked out quite that way.

But as a kind of documentary of what life was like in a bombing plane, as a revelation of the day-to-day agonies of the men whom the infantry dismissed as the “fly-boys,” Face of a Hero has a good deal still to tell us. In its directness, in its skill at drawing the reader into sharing the combat experience of the characters, it is as successful an account of the sky-slogging airman as Van Van Praag’s Day without End was of the mud-caked foot soldier.

Centering his story on the 50 missions to be sweated out by a 35-year-old tail gunner before he can go home (which was the author’s own war experience), Falstein shows us that those crews of ten inside the fragile aluminum skins were anything but the Fancy Dans they might have looked like before or after their 50 missions. They lived in desolate barracks in the midst of nowhere, with almost no contact with the native population except when they got drunk between missions, and were bound to show themselves at their worst. They rose to fight in the dark hours when most other men, at their weakest, were deep in sleep.

The most fervid travelers of all times, they roamed the skies of a continent, hopping over three and four countries on a single journey, but they knew the capital cities only by the density of their flak.

Ploesti, whose oil refineries were all too well guarded, they called a graveyard. And Vienna, with its 400 antiaircraft guns, evoked such frightful associations that they never mentioned its name if they could help it. Their favorite cities were those where the flak fell well short of bombing altitude these were “the milk runs,” and loved dearly.

What they envied most about the infantryman, ironically, was his foxhole. In the air, against flak, there was simply no place to hide as the monstrous black roses bloomed all about you. Either you got through or you didn’t; it was completely out of your hands. Against enemy fighting planes it was a little better: the gunners had something to answer with – but for the four officers of each crew it was the worst of all. Pilot, co-pilot, bombardier and navigator went unarmed and had to sweat through each such engagement in agonized impotence.

As a novel, Fare of a Hero does not perhaps go as deep as it might into the character of people as people (though the author has a keen ear for the varied configurations of their speech). On a documentary level, however, it is one of the best-told tales of air combat in World War II.

DAVID DAVIDSON

David Davidson is the author of “The Steeper Cliff” and “The Hour of Truth”; his new novel, “in Another Country,” will be published late in October.

________________________________________

The Army Stereotype Again

FACE OF A HERO. By LOUIS FALSTEIN

HARCOURT, BRACE. 312 pp. $3.00.

Reviewed by NATHAN HALPER

Commentary

March, 1951

In a book like Louis Falstein’s, the majority of the soldiers are merely historical pushovers.

ONE day, the first sergeant came out to watch us on the drill field. Being green, we were mortally afraid of non-coms. Especially top kicks. This one was tall, bony, with leather face, bull frog voice, and a large wad of tobacco working like a nervous tic in the middle of his cheek.

When it came to doing push-ups, many of us fell on our face. The sergeant stared at us with a succulent unbelief. “Jeez!” he said, “What in hell is the matter with you young guys? It’s no trouble. I can do it. And I was forty-three yesterday.” Whereupon, all the men, two hundred and sixty men, sang, “Happy Birthday to You.”

Happy birthday, dear sergeant

Happy birthday to you.

This is something I remember every time I read a war book. It’s a side of army life which our writers won’t discuss.

Writers did not like the army. They knew they shouldn’t and they wouldn’t before they even entered it. In a sense, their books were written before they ever were experienced. The time spent in the service only added local color.

Their ideas of what would happen, though they were far from being accurate, did contain a core of truth. The army had a lot of evils. The writer put them in his book. But, because of his preconceptions, the writer also managed to see many ills that were not there. He put these in his novel too. Nor was he at all restricted to thing which he though he had seen. Any rumor or surmise, just as long as it was hostile, had in it the ring of fact. It went into his novel too. If, after all this, he still had a memory of something that was pleasant, he knew it was proper to delete it.

Of a thousand meals a year, surely one or two were edible. Of a thousand mess halls, surely one or two were adequate. But, since it is dogma that the army food was bad, no soldier in a war book ever is allowed to get a single decent cup of coffee.

Give the author a kleptomaniac, a dope head, or a rapist. Or give him a poor fellow who murdered the children in Dusseldorf. He will drench them with compassion. He will show they’re not to blame. They are products of heredity, of environment, of these awful times we live in. Give the writer a lieutenant. He will show you and obscenity without the ghost of a redeeming trait.

The GIs, on the other hand, are the writer’s fellow victims. As such, they get his sympathy. But they also are a part of the writer’s army experience. As such he views them with distaste. They’re the people; little people. In a way, they are fine. Certainly, as opposed to the officers. At the same time, he himself as a sensitive, intellectual, and idealistic liberal. And, compared to that, they have such narrow minds, small perspectives, mean horizons.

Put him in the heart of China. He’ll respect their local customs. Give him a tribe of Solomon Islanders. He will try to feel at home.

Give him sailors, loggers, riveters, give him a couple of truck drivers, a few Cape Cod fishermen. He will turn a double cart wheel because they are so Rabelaisian. However, once these men put on an army uniform, their swearing, drinking, wenching suddenly become the marks of a tawdry poverty of spirit.

In his scenes of combat, he will show you farmers falling while the tanks lunge through the furrows. He will show you the civilians while the bombs fall over London. He will show you refugees caught between two hostile armies. Fire, blood, famine, fever, nothing has the strength to faze them. The people are indestructible.

Put these people in the army. They immediately lose their fiber. In a book like Louis Falstein’s, the majority of the soldiers are merely historical pushovers.

In his novel, he describes life in a bomber. Ben Isaacs, the narrator, is a fellow like the author. The members of the crew are the traditional samples of heterogenous men coming from every section of the country. It begins with their first mission. It ends with Sergeant Isaacs after he completes his fiftieth. In between, his colleagues suffer a wide assortment of disasters, both physical and psychological.

The life in a heavy bomber was not any kind of joy ride. Over proves it. He has one man blow his brains out. A second uses his parachute before he even reaches the target. A third one gets obsessive guilt. Something striking happens to every character.

I am sure that happened somewhere. He puts them in a single plane. It is like the Grand Guignol. Once you get the idea, you sit and wait for Lot’s curse to strike the next one.

It’s the same, same old book. This is strange for the writer, Louis Falstein, isn’t at all the usual writer.

He has neither guilt nor guile. He is gentle and judicious. The sort of a scholarly fellow who engages in meditation as he fingers his machine gun while they zoom above Ploesti.

But, instead of writing a book that he might have written, he has taken as his model the cliches of his predecessors. We still get a sense of a fair and thoughtful man. But this merely serves to add a rather incongruous touch to the immoderate proceedings.

Though he follows the precedent of using the Jewish soldier a his chief victim spokesman, one stereotype which Falstein forgoes is that of using anti-Semitism as the chief symbol and vehicle for the GI’s resentment at his fate. He does not close his eyes to it. But when he shows its presence, he does so without that querulous hypersensitivity which we find in so many war books. For this we can be grateful.

________________________________________

Inventing the War Novel

In 1948, five novels about World War II dominated the best-seller lists. They were all written by Jews.

It surely signified something about the progress that American Jews had made that,

when Heller wanted to make his hero an outsider, casting him as a Jew no longer worked.

So he turned him into an Assyrian, or Armenian, or something.

Only many years later did Heller admit that,

whatever his official ethnicity,

Yossarian was really “very Jewish.”

Margolick, David

Wall Street Journal (Online)

December 24, 2015

At the outset of this scholarly and provocative book, Leah Garrett points out a couple of remarkable facts. First, the five books about World War II that dominated the New York Times’s best-seller list in 1948, including Norman Mailer’s “The Naked and the Dead” and Irwin Shaw’s “The Young Lions,” were all written by Jews and had Jewish soldiers as protagonists. Second, four of the best-selling war novels from that year set in the European theater, again all written by Jews, culminated in the liberation of Dachau.

In perhaps the last era when novels were the primary form of civic instruction, books like Mailer’s and Shaw’s-as well as novels soon to come like Herman Wouk’s “The Caine Mutiny,” Leon Uris’s “Battle Cry” and Joseph Heller’s “Catch-22”-”created the template through which Americans saw World War II,” Ms. Garrett writes. All featured Jewish perspectives and Jewish (or Jewish-style) characters and, more than the works in any other medium, brought the catastrophe that had befallen European Jews into the American consciousness.

The war, and the literature it spawned, and the Jewish soldiers depicted in it, helped Jews enter the American mainstream. It also helped Jews overcome enduring wartime stereotypes as shirkers and weaklings, connivers and cowards.

The enormous audiences that these novels enjoyed-”The Caine Mutiny” sold more books than any novel had since “Gone With the Wind” – meant, Ms. Garrett argues, that Jews “became the popular literary representatives of what it meant to be a soldier.” Even widely read war novels by non-Jewish writers, like James Jones’s “From Here to Eternity,” featured sympathetic Jewish soldiers. In John Home Burns’s “The Gallery,” a Jewish Gl is practically the only likable soldier around.

Of the 16 million Americans who served in World War II, 500,000 were Jews. Jews (my father among them) volunteered in greater proportions than the general population, and 11,000 of them were killed. Their rate of service was three times that of Jews during World War I, and not surprisingly: Many in that earlier era had been newly arrived immigrants hardly eager to return to the benighted, blood-soaked continent from which they had only recently fled. Their roles in the literary depictions that followed the two wars varied correspondingly.

The authors of some of the most critically acclaimed American novels of World War I weren’t Jewish and, as their writings make amply clear, didn’t much like Jews either. In “Three Soldiers,” for instance, John Dos Passos describes Eisenstein as a “little man of thirty with an ash-colored face and a shiny Jewish nose,” whom his fellow soldiers dismiss as a “kike” and a kvetch. In E.E. Cummings’s “The Enormous Room,” a Jewish soldier is known as “The Fighting Sheeney.” Americans forever braying about their exceptionalism should compare these calumnies with Rosenthal, the deeply sympathetic Jewish soldier in “Grand Illusion,” the classic French film of the Great War.

But by the time the world went to war a second time, the composition of the armed forces had changed, and so too did the writing that ensued. More Americanized American Jews, most of them second-generation, participated eagerly in World War II, both to help their country and to save the Jews of Europe. (Mailer had an additional incentive. He believed that war, especially in the more dangerous Pacific Theater, would help him write the Great American Novel.)

The bumper crop of novels during and shortly after 1948 also offers a highly disconcerting portrait of the United States and the American military. Jewish soldiers faced prejudice, as did their families. In Ira Wolfert’s “An Act of Love,” a bereft Italian-American mother hysterically boards the train carrying her son off to war, but the hero’s Jewish mother, fearing embarrassment in front of the Gentiles, betrays no emotion at all. Jews, Wolfert explained, “felt they didn’t have the right to behave like people.” To Wolfert’s hero, bigoted country-club Americans “were stronger enemies of his than the Japanese ever could be.”

Ms. Garrett, a professor of Jewish life and culture at Monash University in Australia, writes that Shaw’s “The Young Lions” “is as much an exposition of anti-Semitism in Europe and America as it is a portrait of war.” In basic training its hero, Noah Ackerman, is called “Jew-boy,” “Christ killer” and “herring eater”; he is repeatedly beaten; and he is told that the Jews are why everyone’s fighting in the first place. In Miller’s “That Winter,” an enlisted man tells Lew Cole (ne “Colinsky”) that the Germans “had some pretty good ideas” about the Jew. No wonder Jewish characters in several of these novels undertake suicide missions; they’re desperate to prove, once and for all, that they’re not wimps.

These characters are almost uniformly sympathetic-sensitive but tough, courageous but intelligent. Still, judging from their almost-apologetic feelings about their background, plenty of the Christians around them remain unconvinced. Self-hatred suffuses their souls. They are invariably ignorant of their faith and eager to escape it, often by changing their names or finding themselves good Christian (even anti-Semitic) wives. Only Jew-hatred makes them Jews.