[This post, created on November 20, 2020 and updated on December 1, has been updated yet again. The post now includes: 1) An area map and formation diagrams that provide a more accurate and clearer representation of the nature of the 55th Fighter Group’s encounter with the Luftwaffe on November 29, 1943, and 2) Specific information about what befell three pilots of 7./JG 1, one of the four Luftwaffe Gruppen that intercepted the 55th. Where necessary, other parts of the account have been corrected, updated, or otherwise fixified. Scroll on down for a look…!]

Part VII: A Battle in The Air

What befell the 38th Fighter Squadron and 55th Fighter Group on the mission of November 29, 1943?

For this question, there is an answer.

What happened to Major Joel on that date?

For this question, there is conjecture.

And, for both questions, the best approach lies in understanding the day’s events through information in Squadron Mission Reports, and, Missing Air Crew Reports. By correlating and arranging information from these two sets of documents, it’s possible to create a chronology – that does not exist within any single document – of the Lightning pilots’ encounter with the Luftwaffe, which is presented, below. On reading it, you might want to refer to the post covering the account of the 55th Fighter Group’s bomber escort mission of November 29, 1943.

But first, a digression about the performance of the P-38 Lightning…

Why?

This comes by way of postwar recollections of Major Joel from three people who either knew him “in person” or indirectly: two family friends, and, a relative:

From Sara F. Markham, the best friend of Milton’s wife Elaine (Ebenstein) Joel…

“I want to thank you for all the material you sent, especially the MACR report. All these years later [writing in 1990s], I still find it disquieting to read this sort of thing. Funny, the report I had from the Joels at the time … and from Elaine Friedlich (Elaine’s surname after she remarried) was that Milton, heading back from his mission, saw one of his Lightnings being strafed by two German fighters and he turned back to help that plane.”

From Milton’s friend, Arthur Kamsky…

“He had the bad luck of flying a plane so badly designed that no amount of skill could be of much use.”

From Bettie J. Jacob, Milton’s cousin…

“Milton lived and breathed as a fighter pilot. … We were told after he was declared missing in action that most of the planes in the squadrons broke ranks and fled the scene when the nearly 100 German planes attacked. There were only four planes left to fight, and one of the pilots states he saw Milton get hit. He felt that Milton was killed outright, as he felt Milton could have bailed out otherwise. No trace of Milton was ever found.”

A central “take-away” from the above comments, especially in light of the events of the 29th of November, is the number of P-38s that aborted the mission. This raises a question about the P-38’s very quality as a fighter plane in general, and its use in the European Theater of War – specifically as a bomber escort fighter by the Eighth Air Force – in particular.

To address this issue, fitting answers can be found in Bert Kinzey’s two Detail & Scale volumes on the aircraft (both published in 1998), which summarize the design, technical development, and combat use of the Lighting. The most relevant comments from these books are given below, with the most pertinent passages italicized:

Part 1: XP-38 Through P-38H

“In England, General Ira Eaker did not want fighters escorting his bombers, and they were left with little to do. Within a few short months, the 1st, 14th, and 82nd Fighter Groups were sent to North Africa to support the Allied forces battling Rommel’s Afrika Corps. The 78th Fighter Group arrived in England in January 1943, but it too was sent to North Africa, mostly to replace combat losses in the first three groups. Initial fighting in North Africa was against some of the best pilots and equipment in the Luftwaffe, and the unseasoned Lightning pilots initially suffered heavy losses as they gained valuable experience in combat. Finally, they began to turn the tide and provide an excellent account of themselves. Later, the 1st, 14th, and 82nd Fighter Groups would be relocated near Foggia in southern Italy and reassigned as part of the Fifteenth Air Force when the Allies moved from Sicily on to the Italian mainland.

“Back in England, it became evident that the USAAF was losing bombers at an unacceptable rate. Early P-47 Thunderbolts simply did not have the range to escort the B-17s and B-24s all the way to their targets and back. As a result, the Luftwaffe’s fighter pilots simply waited until the Thunderbolts had to turn back to their bases, then they attacked the unescorted bombers with devastating results.

“In October 1943, the 55th Fighter Group became the first Lightning unit to enter combat with the Eighth Air Force. The 20th, 364th, and 479th Fighter Groups were also assigned to the Eighth Air Force while flying Lightnings, and in the Ninth Air Force, the 474th, 367th and 370th Fighter Groups flew P-38s. At the height of its deployment to the ETO, thirty fighter squadrons and twelve reconnaissance squadrons flew Lightnings at one time or another.

“In England, the Lightning proved to be a very capable aircraft, and in the hands of a skilled pilot, it was as good or better than the Luftwaffe fighters it encountered. But it was also plagued with mechanical difficulties. The cockpit heating and defrosting were inadequate on early versions, and there were digestive problems with the engines at high altitudes. It has been argued by other authors that this was due to the cold damp European weather conditions, but temperatures and humidity are generally the same around the world at altitudes greater than 25,000 feet where these problems occurred. In the Pacific, Lightnings established a great record for reliability regardless of altitude and temperature. Based on all the facts, it is evident that the poor quality British fuels were to blame, because they proved unsuitable for use in turbo-supercharged inline engines. Power-plants with two-speed, two-stage, mechanical superchargers, and even radial engines with turbo-superchargers did not have the same ingestive problems with the British fuels, but the combination of an inline engine and a turbo-supercharger always did. To correct the problem in Europe, Kelly Johnson proposed replacing the turbo-supercharged Allisons with Merlins and mechanical supercharging. While this undoubtedly would have resulted in a fighter of superior performance, the Merlins were considered more valuable for other fighters.”

Perhaps Mr. Kinsey’s comments were addressing the following statement, which appears in Roger Freeman’s 1970 The Mighty Eighth.

“The P-38, supposedly a proven fighter, had been dogged with mechanical failure on these first missions. The extremely low temperatures encountered at altitudes above 20,000 ft was the primary cause of the engine trouble. At -50° lubricating oil became sluggish and the sudden application of full power, particularly in a climb, could cause piston rod bearings to break up with dire consequences. Above 22,000 ft the Allison engines would also begin to throw oil, in fact, oil consumption rose from an average 1 to 2 quarts an hour at lower altitudes, to 4 to 8 above 22,000 ft. This reduced engine life to average 80 odd hours – almost half normal operating time at lower altitudes. Turbo-supercharger regulators also gave trouble, eventually traced to moisture from the vapour trail, gathering behind the engine exhaust stubs, getting into the balance lines and freezing. The vapour trails were also a tactical handicap for they marked the passage of a Lightning through the upper air by distinctive twin trails, that could be discerned up to 4 miles away. Whereas Luftwaffe pilots could not distinguish between the single trails made by Spitfires or Thunderbolts, or their own 109s and 190s, they were able to recognise Lightning formations in this way.”

Part 2: P-38J Through P-38M

“… the Lightnings did a good job in Europe, and because of their distinctive design, they were easily distinguishable from other aircraft. This feature made them excellent escorts, because gunners in the bombers could easily tell them from the enemy fighters. On June 6, 1944, when the invasion of France began, P-38s were assigned to provide air protection over the fleet and beaches, so that the sailors on the ships and the soldiers on the ground could quickly recognize them as friendly.

“Once Jimmy Doolittle relieved Ira Eaker as commander of the Eighth Air Force, he openly stated his desire that all fighter groups transition to the P-51 Mustang. The P-51B, C, and D versions of the Mustang were equipped with a Packard Merlin engine with a two-stage, two-speed supercharger that did not have a problem with British fuels. These Mustangs also offered the necessary range capabilities to escort the bombers to targets that only the P-38 could reach previously. At war’s end, only the 56th Fighter Group was still flying P-47 Thunderbolts in the Eighth Air Force, and no P-38s remained. In the Ninth Air Force, only the 474th Fighter Group was still flying Lightnings on VE day.

“In the Pacific, it was a completely different story. General George Kenney demanded more and more P-38s at the exclusion of all other fighters, much as General Doolittle did with the P-51 in the 8th Air Force. The Lightning, with its significant range capabilities, was ideally suited as a land-based fighter throughout the Pacific from Australia to the Aleutians. Its heavy firepower could knock down a Japanese aircraft in a matter of a few seconds, and as a result, the P-38 scored more aerial victories in the Pacific than any other USAAF fighter. Using high grade American fuels, its performance and reliability were exceptional.”

Want to learn more about the P-38 in combat in the European Theater of War? For a deeper technical and historical analysis of the Lightning in combat, with particular coverage of the aircraft’s unappreciated service as a bomber escort fighter in the 8th Air Force – with particular attention to the plane’s service in the 55th and 20th Fighter Groups, much more than can be presented “here” – I very (very!) highly recommended Dr. Carlo Kopp’s Der Gabelschwanz Teufel – Assessing the Lockheed P-38 Lightning, at Air Power Australia. (Technical Report APA-TR-2010-1201.)

________________________________________

And so, to return to the mission…

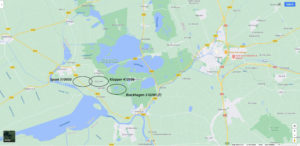

[Updates to this map from its initial version include the following: 1) The crash locations of three Me-109G-6s of the Seventh Staffel of Jagdgeschwader 1, lost (directly or indirectly) as a result of III./JG 1’s engagement with the 55th Fighter Group’s Lightnings, 2) An adjustment to the easternmost “leg” of the 55th Fighter Group’s intended course into Germany (the 55th Fighter Group never actually entered Germany), 3) The crash locations, as much as they can be pinpointed on this ultra-small-scale digital map, of 38th Fighter Squadron pilots Lieutenants Carroll and Gilbride, 4) The serial numbers of the lost P-38s and the three above-mentioned Me-109G-6s. Information about the three 7./JG 1 losses, and the crash locations of Lieutenants Carroll and Gilbride, comes from Part 2 of Teunis Schuurman’s WW II – Research by PATS blog.]

Maps symbols and colors indicate the following:

Maps symbols and colors indicate the following:

Bright blue line extending west to east across the Netherlands to a point near the Dutch-German border indicates the approximate or intended course of the 55th Fighter Group for a rendezvous with 8th Air Force bombers.

Black triangle shows the approximate area where the Luftwaffe initially assumed it would intercept the 55th Fighter Group’s P-38s, as explained in the book Jagdgeschwader 1 und 11: Einsatz in der Reichsverteidigung von 1939 bis 1945 (Jagdgeschwader 1 and 11: Used in the Defense of the Reich from 1939 to 1945).

Blue ovals with names adjacent indicate the last reported or assumed location of P-38 losses, based on information in Missing Air Crew Reports.

Red ovals with names adjacent indicate the actual locations where the P-38s were lost. Notice that there’s no blue oval for Lt. Hascall, because his P-38 was last sighted over the North Sea, at a point “west” of (to the left of) this map view, and Lieutenant Garvin, Major Joel’s wingman, because he definitely crashed at Hondschoote, France (again, well “off the map”). More information will be presented about Lt. Garvin’s fate in subsequent posts.

The location of Major Joel’s loss remains unknown. Some sources suggest the crash location was Marken Island in the Markermeer, indicated by a yellow oval.

In subsequent posts, I’ll discuss why I believe this location is incorrect.

Black ovals with names adjacent indicate the loss locations of three Me-109G-6s of 7./JG 1. (More about this below.)

________________________________________

To return to the story…

Let’s start with the central points from the records of the 38th and 338th Fighter Squadrons, and to a much lesser extent, the 343rd squadron history, for the November 29 mission:

38th Fighter Squadron…

1) The 38th Fighter Squadron was depleted to a little over half its strength – from sixteen to nine aircraft – by the time it was intercepted by Me-109s. The seven planes that left the squadron returned to Nuthampstead between 1344 and 1549;

2) The squadron was attacked head-on, from a higher altitude, by over forty enemy aircraft: a ratio of over four to one;

3) Interception by German fighters commenced at 1410, with the Squadron being engaged in combat through 1440 – at least a half-hour.

4) Major Joel was reportedly shot down at @ 1440. (Oddly, this is contradicted by Lt. Wyche’s account, which suggests that the Major was shot down at 14:15.);

5) There is no evidence – at least, nothing was recorded – to the effect that the 38th was ever able to rendezvous with the B-17s it had been assigned to escort;

6) The continent was overcast at 27,000 feet.

338th Fighter Squadron…

1) The 338th, comprised of fourteen aircraft, departed Nuthampstead after the 38th, at 1259 hours;

2) The squadron was depleted from fourteen aircraft to eight by the time it was intercepted, thus substantially reducing its strength;

3) Like the 38th, the 338th was intercepted by a large number of German fighters (in this case, over 30). The enemy planes attacked the squadron – flying at 31,500 feet – head-on, from the slightly higher altitude of 32,000 feet;

4) The 338th lost contact with the other “squadron” (squadrons?) of the 55th during combat with German fighters;

5) The squadron was unable to rendezvous with the B-17s it was assigned to escort;

6) A significant observation: “Enemy attack seemed definitely intended as interception of our squadron and other E/A were observed in distance to each side and above.” And, this, “One P-38 observed by several members of squadron going into overcast shortly after initial engagement apparently out of control.”;

7) Weather conditions ranged from half to nearly complete cloud cover over the English Channel, to complete overcast over the continent.

343rd Fighter Squadron (what is known…)

1) This squadron was unable to rendezvous with the B-17s;

2) The squadron was outnumbered by enemy planes.

All records combined: A chronological summary of the 55th Fighter Group’s mission of November 29, 1943…

Departure from England…

The 38th Fighter Squadron departed Nuthampstead first, followed by the 338th Fighter Squadron, and lastly the 343rd Fighter Squadron. The horizontal and vertical “spacing” between the three squadrons, and locations of the the squadrons relative to one another aren’t known, but the squadrons eventually arrived over continental Europe: specifically Northern Holland, in an area bounded by the cities of Groningen, Emmen, Zwolle, and Leeuwarden.

The 38th and 338th Fighter Squadrons are depleted by over half their strength…

Between 1344 and 1549, seven planes of the 38th returned to Nuthampstead.

Between 1351 and 1425, six 338th aircraft also returned.

As for the 343rd, based on Capt. Franklin’s statement in MACR 1272 (pertaining to his wingman, 2 Lt. James W. Gilbride), the Captain’s second element – comprising an unidentified pilot accompanied by 2 Lt. Harold M. Bauer – returned to England, diminishing the 343rd from fourteen to twelve aircraft.

In sum, though the 55th Fighter Group began this mission with 42 aircraft, by the time it was intercepted by German fighters, it had been diminished to 27 planes, or somewhat over 60% of its original strength, primarily – as far as is known – among the 38th and 338th Fighter Squadrons. This assumes that only two P-38s returned from the 343rd. This number does not include the 55th Fighter Group’s spares, or, Second Lieutenants John S. Hascall, Robert D. Frakes, and eight other pilots of the 77th Fighter Squadron (20th Fighter Group), the ten of whom tacked on to the 55th as spares for operational experience. It’s unknown if any of the latter eight 77th FS P-38s returned to England early.

The Luftwaffe intercepts the 38th and 338th Fighter Squadrons. This possibly (possibly) occurred over Borger, in the Netherlands (about halfway between Assen and Emmen, at the middle of the right leg of the “triangle” mapped above) based on a P-38 victory claimed by Oberleutnant Erich Buchholz of 9./JG 1 at 15:15. Thus, the vicinity of Borger may have marked the farthest “reach” of the 55th Fighter Group on this mission.

The 38th Fighter Squadron was intercepted by Me-109s between 1410 and 1415.

The 338th was similarly intercepted by Me-109s. The specific time of this event is not given, but is it known that the squadron was over the continent by 1347. So, the 338th’s interception occurred not long after, and probably at the same time as that of the 38th. As the 338th Mission report observed, “Enemy attack seemed definitely intended as interception of our squadron.”

The German fighters (Me-109Gs) attacked both squadrons head-on from a higher altitude, and in a general sense from the east: out of the sun. However, it’s notable that in the MACR for Lt. Albino, Capt. Thomas E. Beaird states that the German planes also attacked from “8 o’clock”. This would indicate a simultaneous attack – at least, against the 38th – from both front and rear.

The depleted and outnumbered 38th and 338th were engaged in combat with the Me-109s from this time on, with the 338th reportedly losing contact with the other “squadron” (the 38th, or, the 38th and 343rd both?) during the engagement.

Major Joel and his wingman (Lt. Garvin), and Lieutenants Wyche and Carroll break into the attack…

By this time, it appears that Major Joel was attempting to reform his nine remaining planes into two flights. Then, at the moment of III./JG1’s attack (14:15) from the 38th’s three o’clock position, the Major ordered a “break” into the Germans’ bounce, the Major and Lieutenant Garvin making a 90-degree turn to the right. They were followed by an element led by Lt. Wilton E. Wyche and his wingman, Lt. John J. Carroll, who were at first situated 300 yards to the right of Joel and Garvin. As the flight turned, Lt. Wyche wound up to the left of the Major and his wingman. Then – alone, after losing sight of Joel, Garvin, and Carroll – Wyche saw six Me-109s coming into attack from their rear (7 o’clock) position. He called a left break, but entered an accelerated stall and spun out of the ad-hoc formation, recovering below.

(Wikipedia’s definition of an aerial combat “break”? “Spotting an attacker approaching from behind, the defender will usually break. The maneuver consists of turning sharply across the attacker’s flight path, to increase AOT (angle off tail). The defender is exposed to the attacker’s guns for only a brief instant (snapshot). The maneuver works well because the slower moving defender has a smaller turn radius and bigger angular velocity, and a target with a high crossing speed (where the bearing to the target is changing rapidly) is very difficult to shoot. This can also help to force the attacker to overshoot, which may not be true had the turn been made away from the attacker’s flight path.”)

Captain Ayers has a last glimpse of Major Joel and Lt. Carroll, and then shoots down an attacking Me-109…

From a different vantage point, Captain Jerry Ayers reported that as his own flight followed Major Joel and Lt. Carroll in an effort to provide cover for them, his flight’s planes were, “bounced by units from a group of about 40 enemy aircraft from one or two o’clock out of the sun,” and he broke into the attack to engage the German planes. As stated in the MACR, “At the time of the first break was the last time that I saw Major Joel and his wingman, Lt. Garvin, that I could recognize them.”

This was the last moment when Lieutenant Garvin was witnessed with any certainty.

While defending the two P-38s, Captain Ayers shot down the leader of a pair of Me-109s which attempted to attack the Major and Lt. Carroll from their two to three o’clock position. As he closed from 350 to 250 yards and fired from approximately 90 to 45 degrees deflection, the German fighter caught fire and went into a spiral out of control, witnessed by Ayers’ wingman, Capt. Thomas E. Beaird, Jr. This was the only victory officially credited to the 55h Fighter Group that day, the other having gone to Captain Chester A. Patterson of the 338th Fighter Squadron.

Ayers was forced to break off his attack because of four Me-109s approaching from behind, thus losing sight of Major Joel.

Major Joel and Lieutenant Carroll form up and attempt to rejoin the rest of the 55th Fighter Group…

As Lt. Carroll wrote after the war, Joel, Garvin, and Wyche were “cut off by a gaggle of Me-109s and the group was headed away from us in a westerly direction”. Separated from other 38th Fighter Squadron planes, Major Joel and Lieutenant Carroll presumably flew west, gong into a defensive maneuver dubbed the “weave formation”. This refers to the Thach Weave, a nice explanation of which van be viewed in the video (below) from Brian Young’s YouTube channel, which pertains to the use of the Thach Weave by F4F Wildcats in defense against Mitsubishi Zeros.

Lt. Carroll witnesses the loss of Lt. Albino…

After the first weave maneuver “pass by”, Lt. Carroll witnessed a P-38 – pilot unknown; he surmised Lieutenant Albino or Garvin – descending, trailing smoke, “minus a section of tail”. (As I discovered while researching this battle, Lt. Carroll was correct in his assumption: The burning P-38 was Lt. Albino’s Spirit of Aberdeen. Based upon the location where the Spirit of Aberdeen crashed, this event definitely occurred directly over the city of Hoogeveen, evidence for this being presented in the next post.

The last sight of Major Joel…

At the crest of his third turn in their “weave”, at a point between Hoogeveen and the farm community of Zwartewatersklooster, Lt. Carroll witnessed a P-38 at a point in space where Major Joel’s “flying wolf” was to have been expected, “seemingly to disintegrate”.

A moment later, Lt. Carroll came under attack. His right engine aflame and instrument panel damaged, he rolled his badly damaged plane over, went into a vertical dive, and, recovering below, took a heading for England using his still operating magnetic compass.

Captain Rufus Franklin and his wingman, Lt. James Gilbride, as a team break formation from their Squadron (the 343rd) to go to the aid of the outnumbered remnants of 38th Fighter Squadron. They arrive just in time to disrupt the attack of III.JG/ 1, saving the lives of at least three (and almost four) 38th Fighter Squadron pilots…

Captain Rufus C. Franklin of the 343rd Fighter Squadron reported in detail about the loss of both Lt. Gilbride and Major Joel. (The following account is a composite from his statements in the MACRs for Major Joel and Lt. Gilbride.)

Captain Franklin reported that at 1210 (probably an error, the time likely having been 1410) “many bandits” were approaching from a lower altitude in the “target area”. At that point, Group Commander Col. Frank B. James started a turn to meet the German planes. The “main body of the group” (whether by this Capt. Franklin meant the 343rd alone, or, the 343rd and 338th both, is unspecified) then went into a right Lufbery Circle.

Though Captain Franklin had by this time lost his second element, Lt. Gilbride remained with him in an “excellent manner”. The main “group” remained in the Lufbery Circle, but Captain Franklin and Lt. Gilbride would “break out” from time to time to see if another attack was imminent.

After two complete turns, the “group” started back to England.

Captain Franklin and Lt. Gilbride followed, assuming that Colonel James was leading. However, the Colonel was not: Captain Franklin specifically mentions that from this moment on, Colonel James was no longer leading the group, which is consistent with the 338th’s Mission Report of the Colonel having returned to England alone.

Captain Franklin reported that as the main body of planes headed back to Nuthampstead, pilots were heard, “calling for help from “far behind us,” specifically including Major Joel. Later, Lt. Erickson, in his own Encounter Report, mentioned that Captain Ayers was also radioing for help.

The rest of “group” continued on its way.

Then, “Just as I had almost decided to go back and help the boys calling repeatedly, the Group started a turn and appeared to be going back but instead made a tight 360 degree turn and went away from the fight again. I could see the fight behind us as the Group made the turn and I broke out – Lt. Gilbride and I went back to help.”

It took Franklin and Gilbride “several minutes” to reach the fight.

As the pair neared the 38th Fighter Squadron’s P-38s, they saw, “five P-38’s engaged and each had from one to three ME 109s on its tail. Just before we went into the fight one P-38 rolled over and went down with its left engine leaving a very long and very heavy trail of black smoke and with a 109 directly behind.” (They had witnessed the fall of either Lt. Carroll or Lt. Albino.)

Franklin and Gilbride flew directly into the midst of the gaggle, the surprised German pilots rolling and climbing away from the P-38s.

The four surviving P-38s headed back to England, even as Franklin and Gilbride made a 180-degree turn to join them.

Then, a (then) unidentified 38th FS P-38 “ran away” from the other Lightnings. The other three P-38s, along with Capt. Franklin, and Lt. Gilbride, were given chase by five Me-109s as the little group of American planes headed west. As will be seen in the next post, the P-38 that pulled away was piloted by Lieutenant Garvin, Major Joel’s wingman.

Lieutenant Gilbride is shot down…

The P-38s attempted to outrun their pursuers, but could not.

Captain Franklin’s left turbosupercharger stopped working and his port engine began to lose oil, and, two of the other P-38s weren’t fast enough to pull away from the German planes. The five Me-109s closed upon Franklin and Gilbride to a distance of 800 yards while remaining to the side and above, with one particular Me-109 alternately latching onto the tail of the element leader and his wingman, moving laterally between the two, approaching to with 400 yards of each.

Eventually, all five Me-109s moved up abreast of Franklin, Lt. Erickson and Lt. Gilbride, and then turned into the American planes. These three P-38s then broke into the Luftwaffe fighters.

As Captain Franklin made a 100-degree turn into the German planes, his port engine quit. By the time he completed the turn, Lt. Gilbride had vanished. As will become evident in the next post, this happened over De Wijk and Koekange, in the Netherlands.

During this running battle, Captain Thomas E. Beaird, Jr., and Lt. Robert E. Erickson fire at and observe hits on two of the pursuing Me-109s, with the implication and possibility (albeit without any confirmation) that the pilots were injured or killed, and the enemy planes thus destroyed by strikes on or near their canopies…

As reported by Captain Beaird, “I looked over my left shoulder and saw one ME 109 right on the tail of the P-38 to my left and behind. I called for Major Joel’s wingman [Lt. Garvin] to break (I thought I had joined Major Joel’s flight). I broke left to meet the ME 109 head on. The P-38 ahead of me to my left also broke left. The ME 109 dove for the clouds. I continued in a left turn to take up my original heading and came out almost directly behind a ME 109 with one P-38 off to my right. I started closing on the ME 109 that seemed to be in a very steep climb for that altitude. I fired one fair burst; saw a flash on his canopy and observed him pull his nose straight up hang on his prop and then spin under my left wing. I turned to the left to clear my tail, looked back and saw him spin into the overcast. I believe this plane was destroyed by my strikes on the canopy.”

And, as recounted by Lt. Erickson, “Captain Ayers and myself were two of five P-38’s at the rear of the group. We observed three enemy aircraft catching us from the rear. At this time I was at 33,000 feet. Captain Ayers called for help and Captain Franklin and Lt. Gilbride of the 343rd came back. At this time one enemy aircraft came behind Captain Franklin and two behind me. We broke left, I completed my turn and came down on the second ME 109 and fired observing hits on wings and near canopy. These two immediately rolled and dove for the clouds.”

Unsurprisingly given the circumstances, there were no witnesses to the results of these two attacks, and the two accounts did not eventuate in officially credited victories for either pilot. USAF Study 85 gives Captain Beaird credit for one victory on February 5, 1944, and there are no official victories for Lt. Erickson.

Captain Franklin, Lieutenant Gilbride, and three surviving 38th Fighter Squadron P-38s are pursued by Me-109s to the Dutch Coast. The four surviving P-38s return to Nuthampstead…

Fortunately able to restart his engine and still pursued by Me-109s, Captain Franklin was rejoined by Lt. Erickson, the pair remaining abreast with the enemy planes following. The German fighters remained behind the P-38s until just beyond the Dutch coast. Then, they left.

Captain Franklin’s conjecture about the fate of Major Joel, and Lieutenants Gilbride and Garvin…

Captain Franklin surmised that Lt. Gilbride had been shot down by the particular “bait” Me-109 that followed himself and the lieutenant and moved laterally back and forth between them. (He put the time at 1240 hours, but I believe this to have been in error, probably having been 1440 or later.) The three surviving 38th FS P-38s which Captain Franklin and Lt. Gilbride aided returned, the two pilots besides Erickson having been Captains Ayers and Beaird. (Lt. Erickson’s Encounter Report places the altitude of this pursuit as between 31,000 and 35,000 feet.)

At the time the MACR was filed, the pilot of the P-38 that “ran away” remained unknown, as did the pilot of the plane that was seen burning and descending into the undercast. However, Captain Franklin did note that, “After we saw the one P-38 go down smoking I did not again recognize Major Joel’s voice on the radio. In view of the circumstances it is my personal opinion that the P-38 we saw shot down was piloted by Major Joel and the one that ran away from us was piloted by Lt. Garvin.” Captain Franklin was wrong about the burning plane having been Major Joel’s “flying wolf”, but this error was understandable given the circumstances. As mentioned above, the burning was P-38H was either Lt. Albino’s 42-67051 or Lt. Carroll’s 42-67090. However, the Captain’s other assumption was correct: The P-38 that “ran away” was piloted by Lt. Garvin.

________________________________________

Taken as a whole, the one certainty that emerges from these Reports is a sense of uncertainty: Due to the nature of this aerial engagement – in terms of its suddenness, the great disparity in the number of P-38s versus Me-109s, the speed of the opposing fighters, the solid undercast, the inability to distinguish one P-38 from another amidst a series of fleeting combats (“…five P-38’s engaged and each had from one to three ME 109’s on its tail…”) let alone the impossibility of visually identifying and following each and every P-38 through the duration of the battle – whether the plane crashed to earth or returned to England – the fate of each and every missing plane and pilot was, at least when these accounts were compiled, uncertain.

But, with information available now, a clearer picture can be seen of events that occurred in the Dutch sky nearly eighty years ago. Some aspects of this “picture are presented above, and others will be presented later.

________________________________________

Such is the American perspective of the engagement. But, every battle has two (and sometimes more) sides, one of which is – by definition – that of the enemy. In this sense, an account of the Luftwaffe’s perspective of this aerial engagement can be found in Part 1 of the book Jagdgeschwader 1 und 11: Einsatz in der Reichsverteidigung von 1939 bis 1945.

But to start, here’s an illustration: This is a Messerschmitt 109 of III./JG 1 during the time period in question: late 1943. The fighter is “white 20”, the aircraft of Hauptmann (American equivalent of Captain) Friedrich Eberle, who commanded the Gruppe from October 9, 1943 through April 27, 1944. This image is actually box art for the Eduard model company’s 1/48 “Bf 109G-6 late series”, kit number 82111, by Shigeo Koike.

Notably, Koike’s painting shows a damaged P-38H of the 338th Fighter Squadron (squadron letters “CL”) in the background. (A minor quibble about the otherwise dramatic painting: Propeller spinners were painted red for 15th Air Force (Mediterranean Theater) P-38s, not those of the 8th Air Force.) As such, unlike plastic model “box art” which typically is visually arresting yet neither specific in time or place, the juxtaposition of a 338th Fighter Squadron Lightning and this particular Bf 109G is historically valid, and reflects two possible dates: November 13, 1943 – when the 338th lost six P-38s (three pilots survived as POWs), or December 22, 1943 – when the 338th lost two planes (neither pilot survived).

So here’s the book’s account (original German text) of the 55th Fighter Group’s interception by fighters of III./JG 1:

So here’s the book’s account (original German text) of the 55th Fighter Group’s interception by fighters of III./JG 1:

Bereits drei Tage später, am 29. November, erfolgte ein weiterer schwerer Tagesangriff auf Bremen; an diesem Tage waren 360 B-17 der 1 und 3 BD eingesetzt, die von 352 Begleit Jägern geschützt wurden. Das schlechte Wetter sorgte allerdings einmal mehr dafür, dass nur 154 Viermotorige ihr Zielgebiet überhaupt fanden, wo die rund 450 t verstreut abgeworfener Bomben kaum Schaden anzurichten vermochten.

Die deutsche Abwehr erfolgte durch den Einsatz von zehn Jagdgruppen sowie Teilen eines Zerstörergeschwaders und des Erprobungskommando [EKdo.] 25; die JG 1 und 11 waren wiederum mit allen sechs Gruppen zur Abwehr der Viermotorigen eingesetzt.

Nachdem der Einflug der Viermotorigen beizeiten erfasst worden war, erfolgte gegen 13.40 Uhr bei allen Gruppen der Alarmstart, nach dem sie an die feindlichen Verbände herangeführt wurden 3). Als erste bekam offenbar die III./JG 1 Feindberührung; sie wurde auf den amerikanischen Jagdschutz angesetzt und stieg nach dem Sammeln in nördlicher Richtung, wo sie um 14.00 Uhr auf die 38 Lightnings der 55 FG stiess. Über dem Westrand des Ijsselmeeres kam es daraufhin zu einer erbitterten Kurbelei, in die bald auch einige P-47 sowie auf deutscher Seite Teile der II./JG 3 eingriffen. In der Meldung der III./JG 1 hiess es dazu:

“Üm 14.00 ühr bekam die Gruppe Feindberührung in 9000 m mit 20 – 30 Lightnings im Dreieck Groningen / Leeuwarden / Meppel (genaue Angabe nicht möglich, da geschlossene Wolkendecke). Ende des Luftkampfes über Zuidersee. Die ausfliegende Spitze wurde vermutlich noch weiter in Richtung West durch eigene Kette unter Führung von Oberleutnant [Olt.] Klöpper verfolgt.” 1)

Acht Abschüsse meldete die III./JG 1 anschliessend 2), erlitt dabei jedoch selbst mit drei Gefallenen, die alle der 7. Staffel angehörten, empfindliche Verluste: Alle drei Messerschmitts der Führungskette mit Oberleutnant [Olt]. Heinrich Klöpper, dem Kapitän der 7./JG 1, seinem Rottenflieger Oberfähnrich [Ofhr.] Manfred Spork und Oberfeldwebel [Ofw.] Hermann Brackhagen stürzten bei der Rückkehr von diesem Einsatz ab – dazu noch einmal aus der Meldung der III./JG 1:

“Vermutliche Todesursache aller drei Flugzeugführer: Herausfallen aus niedriger Wolkenuntergrenze bzw. ausgedehnten Schauern infolge unkontrollierbaren Flugzustandes beim Durchgehen durch dicke Dunstschicht und Wolken ab 8.000 m. Diese Annahme wird erhärtet durch Aufschlag aller drei Flugzeuge mit grosser Geschwindigkeit und Durchdringen tief in den Boden. Flugzeug Oberfahnrich [Ofhr.] Spork aufgeschlagen in Rückenlage in FN 4/1.” 3)

Rund 50 Minuten nach dem Alarmstart kam es bei den anderen Gruppen über dem Raum nördlich Meppen zur Feindberührung mit mehreren grossen Boeing-Pulks und ihrem Begleitschutz. Dabei konnte die II./JG 1, die mit zwölf Fw 190 und zwei Bf 109 sowie 26 Bf 109 der II./JG 27 im Einsatz war 4), zwei B-17 ab- und eine weitere herausschiessen; dem gegenüber standen zwei Gefallene – …

…

Die Stabsstaffel und alle drei Gruppen des JG 11 trafen über dem Oldenburgischen Land auf die Viermotorigen; der amerikanische Jagdschutz verwickelte die deutschen Jäger in heftige Kurbeleien und verhinderte dadurch, dass sich die Guppen des JG 11 geschlossen an die Viermots heranmachen konnten. So gelangen am Ende nur zwei Viermot-Abschüsse sowie der Abschuss von zwei P-47, während das Geschwader selbst drei Gefallene und zwei Verwundete sowie fünf Totalverluste verzeichnen musste. …

…and, in English translation, my comments appearing in parenthesis “[…]”:

Just three days later, on November 29, another heavy day attack on Bremen took place; that day, 360 B-17s of the 1st and 3rd Bombardment Divisions were deployed, protected by 352 accompanying fighters. However, the bad weather once again ensured that only 154 four-engines (heavy bombers) found their target area at all, where the approximately 450 tons of bombs scattered could hardly do any damage.

The German defense was carried out through the use of ten hunting groups and parts of a destroyer squadron and Erprobungskommando [EKdo.] (EKdo: “special-purpose unit tasked with the testing of new aircraft and weaponry under operational conditions”) 25; JG 1 and 11 were again used with all six groups to defend against the four-engines.

After the arrival of the four-engines had been recorded in good time, all groups started the alarm at around 13:40 hours, after which they were introduced to the enemy units. III./JG 1 apparently got the first enemy contact; it was put on the American fighter protection and after collecting, it rose in a northerly direction, where at 14:00 hours it came across the 38 Lightnings of the 55th Fighter Group. As a result, there was a bitter dogfight over the western edge of the Ijsselmeer, which soon involved some P-47s and parts of II./JG 3 on the German side. In the report of III./JG 1 it said:

“At 14:00 hours the group got into enemy contact at 9000 m with 20 – 30 Lightnings in the Groningen / Leeuwarden / Meppel triangle (exact information not possible, because of closed cloud cover). The aerial battle ended over the Zuider Zee. The outgoing tip was presumably pursued further west by an outgoing chain [kette] under the command of Oberleutnant [Olt.] Klopper.” 1)

III./JG 1 subsequently reported eight kills 2), but suffered significant losses with even three fallen, who all belonged to the 7th Staffel: All three Messerschmitts in the leading chain [kette] with Oberleutant [Olt.] Heinrich Klopper, the Captain of 7./JG 1, his wingman Oberfahnrich [Ofhr.] Manfred Spork and

III./JG 1 subsequently reported eight kills, but suffered significant losses with even three fallen, who all belonged to the 7th Staffel: All three Messerschmitts … crashed on return from this mission – again from the report of III./JG 1:

“Probable cause of death of all three pilots: Falling out of a lower cloud base or extended showers due to uncontrollable flight conditions when passing through thick haze and clouds from 8,000 m. This assumption is confirmed by the impact of all three planes at high speed and penetration deep into the ground. …

[Ofw.] Hermann Brackhagen crashed on return from this mission – again from the report of III./JG 1:

“Probable cause of death of all three pilots: Falling out of a lower cloud base or extended showers due to uncontrollable flight conditions when passing through thick haze and clouds from 8,000 m. This assumption is confirmed by the impact of all three planes at high speed and penetration deep into the ground. The aircraft of Oberfahnrich [Ofhr.] Spork crashed upside down in FN 4/1.” 3)

Around 50 minutes after the alarm started, the other groups above the area north of Meppen came into contact with several large Boeing groups and their escort protection. II./JG 1, which was in use with twelve Fw 190s and two Bf 109s and 26 Bf 109s of II./JG 27, shot down two B-17s and once more, there were two fallen – …

I./JG 1 had meanwhile reached the four-engines above the area south-west of Bremen; two kills were then faced with four losses – …

The headquarters staffel and all three groups of JG 11 met the four-engines above the Oldenburg region; the American fighter protection involved the German fighters in violent dogfights and thereby prevented the groups of JG 11 from being able to approach the four-motors. In the end, there were only two four-engine and two P-47s kills and, while the squadron itself had three dead and two wounded and five total losses. …

Data in Jagdgeschwader 1 und 11: Einsatz in der Reichsverteidigung von 1939 bis 1945 reveals that in combat with VIII Fighter Command fighters and B-17s on November 29, 1943, JG 1 and JG 11 incurred the following losses:

JG 1

7 pilots killed; 3 wounded

Aircraft recorded as 100% losses:

FW-190 A-4 – two (both in aerial combat)

FW-190 A-6 – four (all in aerial combat)

Bf-109 G-6 – three (weather)

JG 11

3 pilots killed; 2 wounded

Aircraft recorded as 100% losses:

FW-190 A-5/Y-4 – one (aerial combat)

Bf-109 G-5 – one (belly landing)

Bf-109 G5/U-2 – one (aerial combat)

Bf-109 G-6 – one (aerial combat)

The following is a list of the enemy pilots who claimed victories against Eighth Air Force P-38s on this day. This information is derived (also) from Jagdgeschwader 1 und 11: Einsatz in der Reichsverteidigung von 1939 bis 1945, the Luftwaffe Victories by Name and Date database at Aircrew Remembered, and, 12 O’clock High Forum record number 45307, and, another document – which I copied some years ago, but which now seems to be unavailable (the title escapes me!) – which includes the clock (local) time at which the aerial victory occurred.

Each record comprises (first line): the name of the pilot, his rank, Staffel and Jagdgeschwader, and (second line), the location (place name, alpha-numeric Luftwaffe jagdtrapez map coordinates, altitude in meters) of his claimed victory, and local time of day.

Brett, _____ – Unteroffizier – III./JG 1

JK-9.1 (Netherlands – unknown location) / 9000m – 16:30

Buchholz, Erich – Obertleutnant – 9./JG 1

EO-3.4 / 9000m – Borger SW Oldenburg (Germany) – 15:15

Holz, Klaus – Feldwebel – 9./JG 1

FN-2.8 / 9500-10000m – Meppen-Ommen (37-mile straight-line distance somewhere between Germany and Netherlands) – 14:30

Klöpper, Heinrich – Oberleutnant – 7./JG 1

FN-4.5 – Hasselt [sic] S. Meppen (somewhere between Germany and Netherlands) – 14:15

Krauter, Wilhelm – Obergefreiter – 7./JG 1

GL-1.9 / 8500m – S. Ijsselmeer 135 heading (Netherlands) – 14:35

Lindenschmid, Albert – Fahnenjunker-Feldwebel – 9./JG 1

FN-7.6 / 10000m – Balkbrug-Zwolle (Netherlands) – 14:30

Miksch, Alfred – Feldwebel – 8./JG 1

FN-3.6 / 8600m – Smilde-Beilen (Netherlands) – 14:15

Münster, Leopold – Leutnant – 5./JG 3

1) FN-1.9 / 9000m – Giethoom-Ommen (Netherlands) – 14:28

2) GN-6.5 / 9000m – Nijverdal-Raalte (Netherlands) – 14:30

Some comments:

Numbers and geography…

The eight pilots listed above reported aerial victories as having occurred over the following countries / locations:

Netherlands: Six

Germany: One

Somewhere between Germany and Netherlands: Two

Seven Eighth Air Force P-38s were actually lost on November 29, not nine as claimed. Of the seven, six (Albino, Carroll, Gilbride, Hascall, Joel, and Suiter) were actually shot down in aerial combat. The loss of the seventh – 42-67046 piloted by Lt. Garvin – occurred in France, but this was not directly due to enemy action. You can read more about Lt. Garvin in the post The Missing of November.

Altitude..

All victories occurred at altitudes between 8500 and 10000 meters (roughly 28,000 to 31,000 feet), which is of a notably lower altitude than that given in the 38th’s and 338th’s Mission Reports.

“Where?”

The Oogle map below, based on information in from Part 2 of Teunis Schuurman’s WW II – Research by PATS blog, shows the approximate crash locations of the the three pilots reportedly lost while descending in bad weather. All flying Me-109G-6 aircraft, they were Oberfeldwebel Hermann Brackhagen (“white 5” – 510285; crash location unverified), Oberleutnant Klöpper (in “white 1” – 410106), and Oberfahnrich Manfred Spork (“white 3” – 510930).

A Double Ambiguity: Victories and Losses…

Typical of the nature of chronicles of aerial combat, there are both notable similarities and perplexing differences in American and German accounts of aerial combat between P-38 Lightnings and Me-109s on November 29, 1943.

First, Hauptmann Eberle attributed the loss of the three above-mentioned pilots to weather; specifically, descent through “extended showers due to uncontrollable flight conditions”. Perhaps this was thought so based on information available to Eberle at the time. In this interpretation, a relevant question would be: “Why would an experienced pilot like Klöpper lead two other pilots through undercast without knowing where the cloud base was? A sensible answer would be: Perhaps one or more of the group were running out of fuel, and needed to get under the clouds as quickly as possible to find a place to land.”

There is an alternative possibility, based on the post-battle accounts of Beaird and Erickson, and information at WW II – Research by PATS: Aerial combat.

The following statement concerns the crash of Klöpper’s Me-109G: “According to Mr. Van Benthem, the aircraft was shot and caught fire at a fairly low altitude, after which it fell down with the nose downwards straight from the sky. “He fell down perpendicularly, and not in a gliding flight.” And similarly for Spork, “Plane was on fire while it crashed, pilot in cockpit was burned.” This would suggest that the loss of these two pilots may indeed; may actually, have been attributable to the defensive attacks of Captain Beaird and Lt. Erickson. Albeit, given the fleeting nature and speed of the engagement, it would have been impossible for them to fully observe the eventual results of their strikes on the two Me-109s.

Second, Captain Ayer’s credited aerial victory occurred relatively “early” (as it were) in the course of this brief battle, certainly before the loss of Brackhegen (?), Klöpper, and Spork, who crashed relatively close to one another. Jagdgeschwader 1 und 11: Einsatz in der Reichsverteidigung von 1939 bis 1945 attributes the other Me-109 losses of JG 1 that day to combat with P-47s and B-17s, with JG 11 losing two Me-109s in combat with American planes (not P-38s) at locations quite some distance from Hoogeveen and Meppel. So, it is difficult to correlate the probable location of Captain Ayers’ confirmed victory with that of the three aforementioned pilots.

Next: Part VIII – A Postwar Search – The Missing of November