The Names of Others…

Having focused so closely on Monday, November 29, 1943 – in terms of the loss of Major Milton Joel during the encounter of the 38th Fighter Squadron (55th Fighter Group), with the Luftwaffe over the Netherlands – “this” post is a follow-up to the events of that day: Here – paralleling much the same “template” as my ongoing series of posts (about 30, thus far) focusing on Jewish soldiers in The New York Times – are brief accounts about some other Jewish airmen and soldiers lost or involved in combat on that Monday in November.

________________________________________

But first, “something completely different”. Well, somewhat different. Well, at least kind’a different… An “artifact” direct from November of 1943: The cover of that month’s issue Astounding Science Fiction, featuring art by William Timmins, illustrating the story “Recoil” by George O. Smith.

You can view similar – let alone unsimilar – images, and many more at my brother blog, WordsEnvisioned.

Now, back to the topic at hand…

________________________________________

Some other Jewish military casualties on Monday, November 29, 1943 (2 Kislev 5704) include…

– .ת. נ. צ. ב. ה –

תהא

נפשו

צרורה

בצרור

החיים

United States Army (Ground Forces)

Bernstein, Samuel M., Cpl., 33034466 (in Ireland)

314th Ordnance Maintenance Company

Mr. William Bernstein (father), 807 Carson St., Pittsburgh, Pa.

Born Pittsburgh, Pa., 10/29/16

Jewish Criterion (Pittsburgh) 9/7/45

Cambridge American Cemetery, Cambridge, England – Plot F, Row 5, Grave 4

American Jews in World War II – 511

Fine, Benjamin, Pvt., 33100225, Purple Heart (at Venefro, Italy)

179th Infantry Regiment, 45th Infantry Division

Mr. and Mrs. Abe and Goldy Fine (parents), 705 Washington Blvd., Williamsport, Pa.

Born Grodek Molodetzna, Russia, 8/30/13

Place of Burial unknown

American Jews in World War II – 520

Horwich, Irving I., 2 Lt., 0-1307017, Purple Heart (at Mount Pantano, Italy)

A Company, 168th Infantry Regiment, 34th Infantry Division

Graduate of University of Notre Dame

Mr. and Mrs. Phillip and Anna Horwich (parents) ((or, Mrs. David Goldstein (mother?)), 805 West Marion St., Elkhart, In.

Mrs. Adeline Levine (sister), Elkhart, In.

Born 6/12/13

Hebrew Orthodox Cemetery, Mishawaka, In.

Jewish Post (Indianapolis) 12/31/43

The American Hebrew 3/10/44

American Jews in World War II – 123

United States Army Air Force

8th Air Force

Gladstone, Stanley, 2 Lt., 0-750137, Bombardier, Air Medal, Purple Heart

338th Bomb Squadron, 96th Bomb Group

B-17G 42-37811, Pilot: 2 Lt. Herbert O. Meuli, 10 crewmen – no survivors

MACR 1391

Mrs. Yetta Gladstone (mother), 3822 Surf Ave., Brooklyn, N.Y.

Aviation Cadet Jasin J. Gladstone (brother)

Tablets of the Missing at Cambridge American Cemetery, Cambridge, England

Casualty List 1/1/44

Brooklyn Eagle 12/31/43

American Jews in World War II – 321

____________________

“I would love to go over seas again just for the purpose of finding those graves. I will do all I can to help. Thanking you for having interested in my crew. I still worship the lot of them and I would to God that their bodies are found.” – Edgar E. Schooley, summer, 1945

Gorn, Lion A., S/Sgt., 32411565, Gunner (Right Waist), Air Medal, Purple Heart, 4 missions

525th Bomb Squadron, 379th Bomb Group

B-17F 42-29787, “FR * E”, “”Wilder Nell” II”, Pilot: 2 Lt. Charles H. LeFevre, 10 crewmen – one survivor: S/Sgt. Edgar E. Schooley, Jr, Tail Gunner

MACR 1332

Mrs. Janice L. Gorn (wife), 255 East 176th St., New York, N.Y.

Mr. and Mrs. Nathan [?-10/50] and Fannie Rebecca (Widoff) [8/29/92-10/64] Gorn (parents)

Mildred E. Gorn (sister)

Name commemorated at Tablets of the Missing at Netherlands American Cemetery, Margraten, Holland

Casualty Lists 1/1/44, 12/24/45

P.M. (…the newspaper P.M., that is…) 11/2/46

American Jews in World War II – 331

Based on comments by Fold3 contributor patootie63, the image below, Army Air Force photo A-71044AC (A-11535) captioned, “A crew of the 379th Bomb Group poses beside B-17 Flying Fortress “Wilder Nell II” at an 8th Air Force base in England, 11 November 1943,” presumably shows Lt. LeFevre’s crew posed before the nose of their simply nicknamed bomber.

Though (except in one case – see below!) names cannot be attached to faces on an individual cases, assuming that this is the LeFevre crew, then the men would be:

Le Fevre, Charles H., 2 Lt. – Pilot (rear, far left)

Miller, John R., 2 Lt., Co-Pilot (rear, second from left)

Spurgiasz, Jan, T/Sgt. – Navigator

Valsecchi, Alfred, 2 Lt. – Bombardier (rear, third from left)

Mulligan, James C., T/Sgt. – Flight Engineer

Dixon, Leonard, T/Sgt. – Radio Operator

Hunter, Robert W., S/Sgt. – Gunner (Ball Turret)

Laird, Wesley W., S/Sgt. – Gunner (Right Waist)

Schooley, Edgar E.. S/Sgt. – Gunner (Tail) (probably front row, far left)

…and Sgt. Lion A. Gorn

…of whom the only survivor would be S/Sgt. Schooley.

S/Sgt. Schooley’s postwar account of the loss of the crew of Wilder Nell II, in the Individual Casualty Questionnaires in Missing Air Crew Report 1332, recounts that the aircraft was damaged by both flak and fighters, with Lt. LeFevre giving orders to ditch while the aircraft was still over land. With the exception of Lieutenants LeFevre and Miller, the entire crew – standard for B-17 ditching procedure – was soon gathered in the aircraft’s radio room.

A particularly poignant and haunting aspect of Sgt. Schooley’s account is his mention that Sergeants Schooley, Gorn and radio operator Hunter said “good-bye” to one another just before the the plane struck the sea, with Sgt. Dixon remaining in his seat (transmitting the plane’s position?) even as the plane struck the water.

When the plane impacted, the bottom of the radio room burst open, and “Everything happened so fast that nobody could think very much. I was just tossed by some one.” Sergeants Laird and Mulligan were probably pinned in the sinking plane, while Sgt. Gorn – who stood up just after the B-17 first struck the water (there were typically two impacts when an aircraft ditched, the first moderate in force and the second almost always far more severe) – was thrown forward, and did not survive the ditching. Dixon, Miller, Spurgiasz, and Valsecchi managed to escape the sinking plane. Sadly, though Lt. LeFevre survived the ditching, he became jammed in the co-pilot’s side (right side) window as he attempted to escape the sinking Wilder Nell II. In Sergeant Schooley’s words, “I know he was stuck in the window because I tried to get to him to help, but the sea was too rough. If you will look up the weather on that day, you will know better than I can write.”

Then, “Dixon, Valsecchi and Spurgiasz were hanging on an uninflated dinghy in the water. About 100 ft behind me. Dixon saw me and spoke my name. Then an Me-109 came down and opened up his guns and then I passed out from the cold”.

As described at ZZAirWar, Wilder Nell II ditched one mile off the Dutch coast, near Petten.

While Sgt. Schooley attributed the deaths of those men who had survived the ditching to a strafing Me-109, ZZAirWar suggests a different explanation: machine gun fire from a coastal gun emplacement: “A German officer came running towards the machine gun nest and stopped the shooting [this was a heavy defended coast line, part of the anti-invasion Atlantic Wall]. “Schooley floated unconscious against a wave breaker and was dragged onto the beach. Also Lefevre and Valsecchi washed ashore that day.”

“They were all three brought to the nearest hospital, which was the German Navy Hospital in village Heiloo (‘Hialo’ and ‘Halio’ writes Schooley). This was the to us well known Dutch Mental Hospital ‘St. Willibrordus’, of which the Germans had confiscated a large part and made it their Kriegsmarine Lazeret. Lefevre and Valsecchi were dead and later buried in Heiloo on the General Cemetery. Schooley regained consciousness after 4 days.”

Finally (but there seems not to have been a “finally”…) the following is a transcript of a handwritten letter that Sgt. Schooley included along with his crewman’s completed Individual Casualty Questionnaires:

Dear Sir:

While in the German Hospital at Hialo [actually, Heiloo] Holland, the German people would not tell me any thing.

When I got well and was sent to Amsterdam they told me that they had a body or two. Then they showed me the name of a man and it was Valsecchi 2nd Lt. Then they told me that he was buried some where in Holland, and that Somebody else was there also but they couldn’t describe him to me and he had no identification. That is all I know.

I would love to go over seas again just for the purpose of finding those graves. I will do all I can to help. Thanking you for having interested in my crew. I still worship the lot of them and I would to God that their bodies are found.

Mr. Edgar E. Schooley, Jr.

Edgar Schooley died on March 12, 2015. His obituary can be found at Legacy.com, where appears his portrait (below). And so, in the above crew photo of Wilder Nell II, he appears to be in the front row, at far left.

Lion Gorn’s wife Janice – Dr. Janice L. Gorn, affiliated with New York University – never remarried. Born March 23, 1915, she died on December 18, 2002. The Honoree Page for her husband can be found at the website of the National WW II Memorial: “Arrived in England in October. Forty three bombing kills. He and eight others on B-17 were killed on the way home over North Sea. Tail gunner was rescued and imprisoned until end of war. There were no fighter escorts at the time.”

____________________

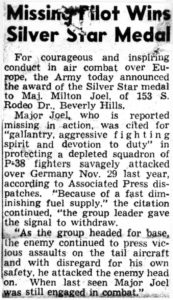

Though Army Air Force navigator Second Lieutenant Ralph Victor Guinzberg, Jr. (0-797311), was killed in action on the 29th of November, as a member of the 334th Bomb Squadron of the 95th Bomb Group, he had participated in two particularly significant combat missions prior to that dat, during neither of which was he injured. Born in 1916, he was a 1938 graduate of the University of Wisconsin. His family resided at 485 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, while his uncle Frederick lived in Chappaqua, N.Y.

The photo below was published in The Daily Argus (Mount Vernon) on August 27, 1943 (via FultonHistory)

The “first” of the two incidents was a mission to Kassel, Germany, on July 30, 1943, during which his aircraft, B-17F 42-30192 “OE * Y“, “Jutzi“, was struck by flak while about 10 miles from Knocke, Holland, knocking out the hydraulic and oxygen systems, and disabling three engines. Control of the bomber being temporarily lost, Lt. Jutzi ordered the crew to bail out. The plane’s four gunners and radio operator did so, but the radio operator and tail gunner did not survive. Realizing that the plane could be kept under control, Lt. Jutzi countermanded his bailout order, and ditched Jutzi six miles from Dover. Injured by flak during the mission, Lt. Guinzberg saved the life of S/Sgt. Harold R. Knotts, after the latter had been knocked unconscious during the ditching.

Lt. Jutzi, his three fellow officers and the flight engineer were rescued. Thus, a total of eight men eventually survived the mission, the incident being covered in MACR 217.

The crew roster for the mission comprised:

Robert B. Jutzi, Pilot (POW 9/16/43 while piloting Terry and the Pirates, 42-30276)

Robert D. Patterson, Co-Pilot (Completed 25 missions)

Wilbur W. Collins, Navigator (POW 9/16/43 aboard Terry and the Pirates, 42-30276, with Lt. Jutzi)

Harold R. Knotts, Flight Engineer (POW 11/29/43 aboard Blondie III)

Parachuted:

T/Sgt. Robert Randall, Radio Operator (KIA)

S/Sgt. Warren W. Wylie, Left Waist Gunner (POW)

S/Sgt. Philbert A. Comeau, Right Waist Gunner (POW)

S/Sgt. Leland M. Bernhardt, Ball Turret Gunner (POW)

S/Sgt. Harold W. Jordan, Tail Gunner (KIA)

The mission eventuated in Lt. Guinzberg’s receipt of a Commendation, the text of which appears below, in this article from the New Castle Tribune of August 27, 1943.

LT. GUINZBURG DECORATED FOR HEROIC ACTION

Lt. Ralph V. Guinzburg, Jr. Awarded Purple Heart and Air Medal

SAVED FELLOW FLYER

Although Wounded When His fortress Was Shot Down, He Rescued Engineer

Lt. Ralph Victor Guinzburg. Jr., 27, of New York City and Chappaqua has been awarded the Purple Heart and the Air Medal and has been recommended for the Silver Star for saving a fellow flyer although himself wounded when his B-17 was shot down over the British channel late in July.

According to word received by Lt. Guinzburg’s family, the Fortress was hit by anti-aircraft shells as it headed home from a mission over the continent.

The last entry in the plane’s log, which was kept by Lt. Guinzburg, navigator, was “Ack-ack inaccurate, low and to the left.” A few minutes later the Fortress was struck three times, with Lt. Guinzburg receiving shrapnel wounds in the ankle. Five of the crew bailed out as the B-17 began to lose altitude at the rate of 1000 feet a minute. Lt. Guinzburg and three other officers remained in the plane, trying to get it back to the coast of England.

Seven miles from the British coast, the Fortress crashed into the sea. One man was knocked unconscious and Lt. Guinzburg was thrown violently against the roof of the ship. He suffered a deep cut on the forehead but remained conscious. As the Fortress began to sink, he remained inside to push the unconscious man through the hatch, while the others helped from the outside.

The plane’s automatically inflated life-rafts were already floating on the water as the plane went down. Carrying their unconscious comrade between them, the three men swam to the rafts and were shortly rescued.

Lt. Guinzburg attended the Fieldstone School in Westchester and is a graduate of Wisconsin University. Before his overseas assignment, he was on anti-submarine patrol here. He is the son of Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Guinzburg.

Complete citation of Lt. Ralph Victor Guinzburg, Jr.

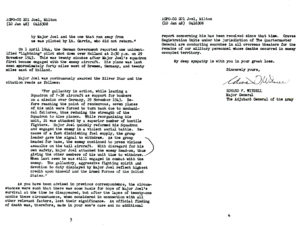

Through the Commanding Officer:

“1. As a result of enemy anti- aircraft fire on a mission over Germany on July 30. 1943, the airplane on which you were the navigator was seriously damaged. Three engines, the oxygen system, and the hydraulic system were rendered unopperative. After making a forced landing in the open sea, the plane began to sink rapidly. Observing, when about to leave the aircraft, that the aerial engineer was missing you searched and found him in the radio room. He was unconscious, his foot pinned by equipment. You brought him through the plane safely into the dinghy. For a few minutes you were securely in the dinghy when the stabilizer of the sinking aircraft brushed by causing another member of the crew to jump into the water. Though physically weakened by injuries, you, with unfailing determination, paddled to him and helped him to climb into the boat. You are commended for extraordinary courage.

“2. A copy of this commendation will be filed in your official file and made a part of your next efficiency report.”

ALFRED A. KESSLER. Jr.

Colonel Air Corps, Commanding.

“1. I desire to add my commendation to the above for your extreme coolness and courage in your action during the damaging of your airplane.

“You have been an inspiration to the entire command.”

JOHN K. GERHEART

Colonel Air Corps, Commanding.

“1. Your actions under duress reflect the spirit which we like to consider symbolic of Americanism.

“2. My heartiest congratulations.”

DAVID T. MACKNIGHT

Major Air Corps, Commanding.

Likewise, the story was reported upon in the New York City-based German refugee newspaper Aufbau, on September 24, 1943, in an unsigned article that oddly was in English, not German. (? – !)

More Medals for Guinzberg

The navigator of a Flying Fortress returning home from a bombing mission over Europe made an entry in the plane’s log. “Ack-ack inaccurate,” he wrote, “low and to the left.” It was the last sentence in that log. A few minutes later the Fortress was struck three times. The navigator suffered a shrapnel wound in the ankle. Five of the crew bailed out as the plane began to lose altitude at the rate of 1,000 feet a minute. The navigator and three officers remained in the plane. They tried to get the B-17 back to the English coast.

Seven miles from the coast of Britain the Fortress crashed. It plunged into the sea, and in the rush of its downward flight one man was knocked unconscious and the navigator was hurled violently against the roof of the ship. There was a deep cut on his forehead, but he was still conscious.

The Fortress was beginning to sink. The navigator stayed inside. He did not leave until he had helped push the unconscious man through the hatch, while the third man helped from the outside.

By this time the plane’s automatically inflated life-rafts were already floating on the water. Carrying their unconscious comrade between them, the three men swam to the rafts and were shortly rescued.

The navigator who stayed in that sinking Fortress to save a fellow-officer is a 27-year old New Yorker named Lt. Ralph Victor Guinzberg. He has been awarded the Purple Heart and was recommended for the Silver Star for his heroism on that mission. The incident took place in July.

Lt. Guinzberg, who holds the Air Medal for an earlier exploit, is the nephew of Ralph Guinzberg of the Jewish Welfare Board’s Greater New York Committee. He is the grandson of Mrs. Henrietta Kleinert Guinzberg, of Westchester, who founded the Red Cross Chapter of Westchester more than a quarter of a century ago.

Lt. Guinzberg attended the Fieldston School in Westchester and is a graduate of Wisconsin University.

__________

On September 7, 1943, Lt. Guinzberg was wounded in the leg by flak while flying aboard B-17F 42-30233 (“QW * X”, “Rhapsody in Flak”) with the 412th Bomb Squadron, during a mission to Watten, France. (By definition there’s no MACR for this incident.) The plane was piloted by Lt. Edmund L. Barraclough. The image below, dated September 24, 1943 (coincidentally the same date as the above Aufbau article) shows his receipt of an award (I’m not sure which). Note that he’s using a cane to support himself.

__________

Lt. Guinzberg’s last mission: The incident is covered in MACR 1560 (extremely poor reproduction by Fold3…) and recorded in the very “early” Luftgaukommando Report KU 462 (probably destroyed or lost, as it never became part of NARA’s holdings).

He was killed during the Bremen mission while aboard B-17F 42-6039 (“BG * H“, “Blondie III“) piloted by 1 Lt. Leslie B. Palmer. The bomber was last seen in the vicinity of Bremen, losing speed but under control, but there were no specific witnesses to Blondie III’s loss, or at least none whose names appeared in MACR 1560.

Postwar Casualty Questionnaires revealed that shortly after Lt. Guinzberg informed the crew, via intercom, that their plane had entered Germany territory, it (and presumably, other 95th Bomb Group B-17s) was attacked by Me-109s. Immediately after, Lt. Guinzberg was killed by enemy fire – the crew’s sole casualty – and the plane sustained such damage that they was forced to parachute. All did so successfully, with the crew landing and being captured in the vicinity of Oldenburg. According to David Osborne’s “B-17 Master Log”, the aircraft crashed at Aumhle Bosel, four miles southeast of Friesoythe. Blondie III was the only 95th Bomb Group aircraft lost that day.

Lt. Guinzberg received the Air Medal, 4 Oak Leaf Cluster, Soldier’s Medal, and Purple Heart. He completed between 14 and 17 missions. He is buried at the Ardennes American Cemetery, at Neupre, Belgium. (Plot B, Row 25, Grave 2)

Lt. Ralph Guiznberg’s name appears in the following sources:

War Department Casualty Lists 10/10/43, 1/1/44

The Daily Argus (Mount Vernon) 8/27/43, 2/9/44, 1/17/45

New Castle Tribune (N.Y.) 8/27/43

Aufbau 9/24/43

American Jews in World War II – 338

________________________________________

Weider, Norman L., 1 Lt., 0-795530, Co-Pilot, Air Medal, 2 Oak Leaf Clusters, Purple Heart, 15 missions

548th Bomb Squadron, 385th Bomb Group

B-17G 42-37874, “WHO DAT – DING BAT”, Pilot: 1 Lt. William Lawrence Swope, 10 crewmen – no survivors; MACR 1532

Born 12/24/19

Mrs. May Weider (mother), 107-55 123rd St., Richmond Hill, N.Y.

2 Lt. Arthur Weider (brother)

Tablets of the Missing at Cambridge American Cemetery, Cambridge, England

Casualty List 1/1/44

Brooklyn Eagle 12/31/43

Long Island Daily Press 1/16/43, 12/31/43

The Record (Richmond Hill) 11/4/43

American Jews in World War II– 466

According to The Record (Richmond Hill) 11/4/43, wounded by flak on Munster raid, in “week prior to 11/4/43” – probably 10/10/43

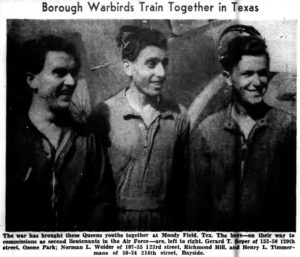

The photo below was published in the Long Island Daily Press on January, 16, 1943. Caption? “The war has brought these youths together at Moody Field, Tx. The boys – on their way to commissions as second lieutenants in the Air Force – are, left to right, Gerard T. Soper of 152-50 129th Street, Ozone Park; Norman L. Weider of 107-55 123rd Street, Richmond Hill, and Henry L. Timmermans of 50-24 214th Street, Bayside.” A review of various databases (WW II Memorial, NARA, Fold3, etc.) reveals that Soper and Timmerman – assuming they eventually served in combat – survived the war, and were never POWs.

A little over a month before the November 29 mission, Lt. Swope’s crew posed in front of B-17F 42-30094 “Belle of the Blue” at Great Ashfield, Suffolk, England, for a photo that would become Army Air Force image C-59116AC / A9135. Caption?: “1st Lt. W.L. Swope’s crew of the 548th Squadron of the 385th Bomb Group based in England, standing by their B-17 Flying Fortress. 22 October 1943.”

The four officers in the front row have been identified by Fold3 researcher Patootie63 as:

Far Left: 2 Lt. Robert Charles H. Prolow, navigator

2nd from left: Lt. Weider

3rd from left: Lt. Swope

Far right: 2 Lt. Douglas H. Baker, bombardier

The six crew members in the rear, albeit without names correlated to faces, are probably:

T/Sgt. Stanley Robinson – Flight Engineer

S/Sgt. Richard E. Street – Radio Operator

S/Sgt. James W. Harbison – Gunner (Ball Turret)

S/Sgt. Francis J. Magner – Gunner (Tail)

S/Sgt. Earl R. Robinson – Gunner (Left Waist)

S/Sgt. Elmer J. Congdon – Gunner (Right Waist)

Nearly one month later, the December 31, 1943, issue of the Brooklyn Eagle, in its daily back page column “With Our Fighters”, reported that Norman and his brother Arthur spent Thanksgiving together at Great Ashfield. The brief news item closes with Arthur’s hope that, “But he [Norman] was positive he’d get back home, and I’m pretty confident myself that he’s safe somewhere.”

BROTHER MET WEIDER BEFORE LAST FLIGHT

Second Lt. Arthur Weider, a navigator in the ferry command, delivered a B-17 to Scotland last November. While there he visited his brother, 1st Lt. Norman L. Weider, a pilot and flight commander in the A.A.F. at an air base near London.

They spent the 24th and 25th together and then Arthur returned home. On November 29 Norman went on his 15th mission and didn’t return.

“I phoned him long distance on the 27th,” Arthur said today – he’s home for a few days. “At that time he was out on the Bremen raid. The next day was a raid on Berlin and since that date he has been listed as missing.

“But he was positive he’d get back home, and I’m pretty confident myself that he’s safe somewhere.”

The 24-year-old pilot enlisted the day Germany declared war on the United States and has been in England since last August.

The Weiders live at 107-55 123rd St., Richmond Hill.

____________________

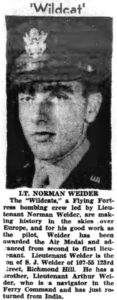

The below image of Lt. Weider, contributed by researcher “Anonymous“, is from his FindAGrave biographical profile. The original source of the clipping is unknown, but given its halftone printing, it’s probably from a newspaper.

____________________

As reported in Missing Air Crew Report 1532, three witnesses reported seeing WHO DAT – DING BAT drop out of the 385th Bomb Group’s formation over the Zuider Zee, with Lt. Swope or S/Sgt. Street radioing that the aircraft had only 30 minutes of fuel remaining and they would try to reach England. Last observed descending into clouds near “Tessel” (Texel) Island, Holland, the plane was never seen again.

Sixteen days later, on December 15, police at Whit Stable, Kent County, England, discovered the bodies of two men on the Whit Stable Bay mud flats. S/Sgt. Congdon, the plane’s right waist gunner, was found within one of the bomber’s two 5-man life-rafts, while 200 yards away was found the body of 2 Lt. Prolow, the plane’s navigator. According to the Squadron Flight Surgeon, indirectly quoted in MACR 1532, both men had survived until approximately December 14.

Lt. Prolow is buried at the Cambridge American Cemetery in Coton, England, while S/Sgt. Congdon is buried at Beaverdale Memorial Park, in New Haven, Ct. Notably, the date on both men’s tombstones is actually November 29, the date when WHO DAT – DING BAT was actually lost, suggesting a discrepancy in records, or, an error in the account as presented in the Missing Air Crew Report.

England

AC 2C Charles Goldberg and Gunner Abraham Yudkin

Died or Murdered While Prisoners of War

While researching records in Henry Morris’ We Will Remember Them – A Record of the Jews Who Died in the Armed Forces of the Crown 1939 – 1945, I came across the name of Gunner Abraham Yudkin, who served in the Royal Artillery and who the Commonwealth War Graves Commission records as having been killed on November 29, 1943. Further research at the CWGC database for that calendar date yields a record for Aircraftman Second Class Charles Goldberg, whose name is absent from Morris’ book. As well, neither man’s name ever appeared in any wartime issue of The Jewish Chronicle. Biographical information about the men follows…

Goldberg, Charles, AC 2C, 1061437, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

Mrs. Shirley Goldberg (wife), Leeds, Yorkshire, England

Mr. and Mrs. Louis and Cissie Goldberg (parents)

Singapore Memorial, Singapore – Column 429

We Will Remember Them – Not Listed

Yudkin, Abraham, Gunner, 1819219, England, Royal Artillery

2nd Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, 48th Battery

Born 1914

Mrs. Frances Yudkin (wife), Hackney, London, England

Mr. and Mrs. Sam and Anne Yudkin (parents)

Singapore Memorial, Singapore – Column 34

We Will Remember Them – An Addendum – 23

The date of “November 29, 1943” and commonality of the Singapore Memorial somehow seemed to link the two, and a web search (the mens’ serial numbers were the “key” here) revealed their story: They were both prisoners of war of the Japanese, and among the 548 British and Dutch POWs aboard the Japanese army cargo ship SS Suez Maru. I don’t know when they were captured, but given the place of their commemoration – the Singapore Memorial – perhaps they were taken captive on or about February 15, 1942, during the fall of Singapore.

As for the Suez Maru? On November 29, 1943, the Surabaya-bound ship was sunk by a torpedo attack from the submarine USS Bonefish, while 50 miles northeast of Kangean Island, north of Bali. Whether Goldberg and Yudkin (let alone any of the other 547 POWs, on a specific name basis) survived the vessel’s immediate sinking, or not, will never be known among men. But in any event, what transpired soon after has become known as the “Suez Maru Massacre”, and in some ways parallels and is representative of the horrors that befell American POWs aboard what are now known as the “Hell Ships” later in the war.

As described by Jan Lettens at WreckSite, Suez Maru Massacre, “Unbeknown to the submariners [of the USS Bonefish], Suez Maru had on board 415 British and 133 Dutch POWs. 69 Japanese were killed in action.

“Escorting Japanese minesweeper W-12 rescued some 200 Japanese and Korean survivors. Only after the war, the fate of the POWs was revealed: Kawano Usumu, commander of W-12 had instructed his gunners to kill all (200 – 250) survivors.

“At 14:15, the massacre began; the Japanese fired with their machine guns from a distance of 50 meters and continued until the sea around turned red with blood. More than 2 hours later, at 16:30, the W-12 moved away from the scene, having carefully verified that all were killed.”

Notes (2/24/19):

1. The W-12 was torpedoed and sunk on April 6th, 1945 by submarine USS Besugo (SS-321).

2. After the completion of the Japanese War Crimes Trials, no further action was taken to indict Kawano Usumu, Commander of Minesweeper W-12, for the killing of Allied Prisoners of War, neither Lt. Koshio for carrying out the orders on the Suez Maru.

Here’s a full list of the British and Dutch POWs aboard the Suez Maru.

__________

Lasky, Isaac, Pvt., 7368048, Royal Army Medical Corps

Born 1918

Mr. and Mrs. Abram and Lily Lasky (parents), Sheffield, England

Tel-el-Kebir War Memorial Cemetery, Egypt – 4,E,3

We Will Remember Them – 116

South Africa

Levin, Sam, Pvt., 187618, South African Medical Corps, Technical Service Corps

(wife), at 161 Jules St., Belgravia, Johannesburg, South Africa

Alamein Memorial, Egypt – Column 146

South African Jewish Times 1/15/43, 9/7/45

South African Jews in World War Two – xii

Previously MIA, @ 1/1/43 – Presumably escaped from captivity, or, evaded capture

From the Yishuv

Babahikian, Setrack Haji, Driver, PAL/31428, Royal Army Service Corps

Heliopolis War Cemetery, Heliopolis, Cairo, Egypt – 5,P,13

We Will Remember Them – An Addendum – 42

Prisoners of War

United States Army Air Force

8th Air Force

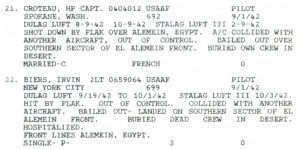

Breslau, Morton David, 2 Lt., 0-673470, Navigator

548th Bomb Squadron, 385th Bomb Group

POW, Stalag Luft I, North Compound I

B-17F 42-30204, “GX * H”, “Gremlin’s Buggy”, Pilot: 1 Lt. Richard Yoder, 10 crewmen – 5 survivors; MACR 1581, Luftgaukommando Report KU 465

Born July 22, 1916

Mrs. Bertha Breslau (mother), 2503 (2305?) University Ave., New York, N.Y.

Casualty Lists 1/7/44, 2/5/44

Returned POW List 6/16/45

Syracuse Herald-Journal 10/5/43

American Jews in World War II – Not Listed

________________________________________

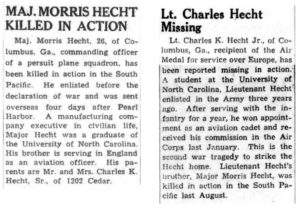

While my prior series of posts, concerning Major Milton Joel, focused on P-38 Lightning losses incurred by the 8th Air Force on November 29, 1943, the 8th Air Force actually lost a total of 16 fighters (seven P-38Hs and nine P-47Ds) that day. From this group of pilots there were seven survivors, among whom was Second Lieutenant Charles K. Hecht, Jr. (0-795955), a member of the 358th Fighter Squadron of the 355th Fighter Group. Flying P-47D 42-8631 (the un-nicknamed “YF * U“), he crash-landed in Holland and was captured, spending the rest of the war in Stalag Luft I (Barth), specifically in the POW camp’s South Compound. He was awarded the Air Medal and one Oak Leaf Cluster. Born on September 20, 1918, he was the son of Charles K. Hecht, Sr., and Sadie (Berg) Hecht), and resided at 1202 Cedar Avenue, in Columbus Georgia. He passed away on July 18, 2001.

Some years ago – specifically, in 1994 – I had the good fortune of interviewing Mr. Hecht about his wartime experiences. His words provide an interesting counterpoint to those of William S. Lyons, who served in the 357th Fighter Squadron of the 355th. You can listen to Mr. Hecht’s recollections and comments below, a “breakdown” of the topics discussed being listed below the sound-bar.

0:00 – 1:54: Entering the United States Army Air Force, from being an enlisted man in the Army ground forces.

1:55 – 2:46: Pilot training.

2:46 – 3:50: Becoming a fighter pilot, and, being assigned to the 355th Fighter Group.

__________

3:51 – 5:18: The death of his brother, Major Morris Hecht, commander of 67th Fighter Squadron, 347th Fighter Group, 13th Air Force. The two news items below, from November 5, 1943 about Major Hecht’s death, and, from January 28, 1944, about Charles’ MIA status, are from The Southern Israelite.

Major Morris “Mike” Hecht , 0-427727

Killed August 19, 1943 in crash of P-39K 42-4373 (structural failure of wing) – No MACR

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery, Manila, Philippines

__________

5:18 – 6:17: Service in the 358th Fighter Squadron; movement to England aboard HMS Queen Elizabeth. (At 5:40: “A cabin for two, and fourteen of us in it.”)

6:17 – 6:57: Arrival and experiences in England.

6:57 – 7:25: Thoughts about implications of being captured and identified as a Jew. (He didn’t think about it!)

7:25 – 8:30: Flying the P-47; flying combat missions.

8:30 – 10:30: Mission of November 29, 1943; possibly having shot down an “Me-210” (9:36). (Given the service history of the Me-210, the aircraft encountered was almost certainly an Me-410.)

10:30 – 11:40: Crash-landing in Holland. His wingman was probably 2 Lt. Richard Peery in 42-22484 (“YF * L“), who also survived.

11:40 – 12:23: Being captured.

12:23 – 13:05: During his interrogation, was there a focus upon his being a Jew? – (Answer: No.)

13:05 – 13:30: Arriving at Stalag Luft I (Barth). Comments about Captain Mozart Kaufman (494th FS, 48th FG, 9th AF).

__________

13:30 – 14:02: POWs remembered from Barth:

“Willie Yee” from Hawaii: 2 Lt. Wilbert Y.K. Yee, 0-735224, Bombardier, 546th Bomb Squadron, 384th Bomb Group, 8th Air Force, B-17F, 42-24507, Pilot: 2 Lt. James E. Armstrong, “JD * B”, “Yankee Raider”, MACR 772

“Wally Moses” (?) (Probably “Mo” Moses, from Vidalia, Ga.)

Other members of 358th Fighter Squadron remembered from Barth

“Kossack”: Capt. Walter H. Kossack (POW 11/7/43, P-47D 42-8477, “YF * X”, MACR 1282)

“Roach”: (2 Lt. William E. Roach (POW 11/7/43, P-47D 42-22490, “YF * U”, “Beetle” (In Luftwaffe service as “7 + 9”), MACR 1281)

“Carver”: 1 Lt. Harold I. Carver (POW 3/16/44, P-51B 43-6527, “YF * J”, “Indiana Clipper”, MACR 3391)

__________

14:02 – 14:35: Activities at Barth.

14:36 – 15:10: Segregation of Jewish POWs.

15:10 – 15:47: Liberation.

15:47 – 15:55: Did he keep a diary?

16:10 – 17:08: Return to United States and home at Columbus, Georgia.

17:10 – 17:26: Other aspects of his interrogation.

17:26 – 17:55: Memories of other Jewish aviators.

17:55 – 18:10: Service In Air Force Reserve.

18:11 – 18:40: Return visit to Steeple Morden in early 1990s.

__________

18:40 – 19:26: Other Jewish POWs remembered from Barth:

Capt. Leon Bernard Margolian, 0-420749, Fighter Pilot, 65th FS, 57th FG, 12th Air Force, POW 12/10/42, Shot down during dogfight with Me-109s at “Marble Arch” (near Ra’s Lanuf – a town on the Gulf of Sidra), Libya, while piloting P-40F (“Tiger Lil“, “5 * 4”?). Wounded during the incident.

The image below, a portrait of Captain Margolian from his POW diary, was sketched by “Smedley“. A review of various databases and websites reveals that “Smedley” was in all probability Captain Arthur A. Smedley, Jr., of either the 96th Fighter Squadron or Headquarters Squadron of the 82nd Fighter Group. He was captured on January 30, 1943.

This image, also from Captain Margolian’s diary, shows a sketch of “Tiger Lil” – “5 * 4“. The artwork is by “Llewellyn“, who was probably Captain Raymond A. Llewellyn, of the 66th Fighter Squadron, 57th Fighter Group, captured on November 1, 1943.

And, Captain Margolian’s POW “mug shot”…

_____

2 Lt. Milton Plattner, 0-736650, Navigator, 20th Bomb Squadron, 2nd Bomb Group, 15th Air Force, POW 12/19/43, B-17F 42-5427, Pilot: 2 Lt. John C. Williams, MACR 1530, 10 crew members – 8 survivors; Luftgaukommando Report ME 572

The video below, from Andy Kapeller’s YouTube channel Andrea ́s-living-history-hautnah, entitled “2017 Weerberg Nurpensalm“, shows the remnants of 42-5427 as they appeared four years ago (and probably still do today?). The video description is: “Wandern am Weerberg zur Alpe Obernurpens. Wrackteile an der Absturzstelle des amerikanischen Bombers B-17F Flying-Fortress (Nr. 42-5427) der 2nd Bomb Group, 20th Bomb Squadron der 15th USAAF aus Amendola (Italien) kommend, welche am 19.Dezember 1943 um ca. 12 Uhr dort zerschellte.”

Translation? “Hiking on the Weerberg to the Alpe Obernurpens. Wreckage at the crash site of the American B-17F Flying Fortress bomber (No. 42-5427) of the 2nd Bomb Group, 20th Bomb Squadron of the 15th USAAF, coming from Amendola (Italy), which crashed there on December 19, 1943 at around 12 noon.”

Though most of the debris is unrecognizable, from 2:50 to 3:00, Mr. Kapeller’s camera focuses upon an intact remnant of the plane: A cylindrical ring with protrusions. This object is an exhaust manifold assembly from one of the bomber’s four Wright Cyclone engines. A clearer view of the varied designs of exhaust manifolds for a B-17’s engines (notice that the design of the manifold differs depending upon the location – positions “one” through “four” – of the plane’s engines) appears in the illustration below, from the Illustrated Parts Breakdown for the B-17G (USAF TO 1B-17G-4).

_____

2 Lt. Arthur A. “Red” Carmel, 0-668893, Bombardier, 407th Bomb Squadron, 92nd Bomb Group, 8th Air Force, 11/16/43, B-17F 42-29996, “PY * R“, “Flagship“, Pilot: 2 Lt. Joseph F. Thornton, MACR 1384, 10 crew members – all survived; Luftgaukommando Report KU 429

_____

2 Lt. Milton Julius Caplan, 0-683250, Navigator, 511th Bomb Squadron, 351st Bomb Group, 8th Air Force, 1/30/44, B-17G 42-3509, “DS * Z“, “Crystal Ball“, Pilot: 1 Lt. Charles E. Robertson, “DS * Z”, “Crystal Ball”, MACR 2262, 10 crew members – 9 survivors; Luftgaukommando Report KU 771

_____

2 Lt. Isaac Sackman Marx, 0-735623, Bomber Pilot, 578th Bomb Squadron, 392nd Bomb Group, 8th Air Force, 11/13/43, B-24H 42-7483, “R-“, “Big Dog”, MACR 1553, 10 crew members – all survived; Luftgaukommando Report KU 414

__________

9th Air Force: A B-26 Returned – Two Crewmen Did Not

Among the over 16,000 Missing Air Crew Reports filed for WW II-era USAAF combat or operational losses at least 235 for aircraft which were not actually lost, and either returned to their own base of origin, or, returned to “other” air bases in England, Western Europe, the Mediterranean Theater, the Pacific, or Asia. MACRs in such circumstances – all for multi-place aircraft, typically bombersand in one case each, a P-61 and C-47 – generally pertain to incidents during which one or more aviators parachuted from their aircraft due to their immediate (very immediate!) perception and belief that the plane was about to crash, battle damage, loss of control by pilots, (very) sudden mechanical failure or fire, severe injury or wounds, bad weather, or, some some combination of these factors.

One such incident is epitomized in MACR 16096, a high-numbered post-war “fill-in” MACR pertaining to an incident that occurred on November 29, 1943. This involved to Martin B-26B Marauder 41-31679 – “Itsy Bitsy” / “FW * K” – of the 556th Bomb Squadron of the 387th Bomb Group, piloted by Major Walter J. Ives. (The MACR lists two serials for the aircraft: 41-31679 and 41-31697, but the correct number is the former, as 41-31697 was “Duck Butt” / “TQ * R“.) Two of the plane’s crewmen, co-pilot 1 Lt. Jess A. Watson, and flight engineer S/Sgt. Curtis L. Christley bailed out over the English Channel (at 50-14 N, 00-40 E; a little over half-way between Eastbourne, England and Dieppe, France – see the Oogle map below) when the bomber’s controls became frozen by ice and the plane appeared to go out of control. However, Major Ives managed to regain control of the plane, to land at an RAF Spitfire base with his four other crewmen. After refueling, he flew back to the 387th’s base at Chipping Ongar.

Lt. Watson and S/Sgt. Christley were never seen again.

MACR 16096 covers the incident in detail, and includes statements by T/Sgt. Andrew Smerek, the radio operator, and S/Sgt. Martin S. Cohen, the bomber’s tail gunner. These statements, both written nearly two years after the incident, convey the nature of the event in vivid and frightening clarity.

__________

Here’s S/Sgt. Cohen’s statement:

3831 Pennsgrove Street

Philadelphia 4, Pa.

September 5, 1945

N.W. Reed, Major, Air Corps

Chief, Notification Section

Personal Affairs Branch

AC/AS-1

Dear Major Reed:

This is in reply to your letter of August 31, AFPPA-8-JH, concerning Staff Sergeant Curtis L. Christley, 33154439. As you had stated, I was the tail gunner of the air crew of which Sergeant Christley was engineer on November 29, 1943. According to your request the following is a report to the best of my knowledge of the circumstances concerning the mission:

We were flying lead ship for the group piloted by Major Walter Ives. The weather was very bad that day. As I remember many of us remarked that it was much too bad for flying. However, we took off, anyway.

We flew over a rather wide part of the Channel. As it was later estimated, about twenty miles from the French coast we received a recall from Wing. When we turned around I sat by the waist windows. The pilot tried to climb through the overcast which was very thick. When we reached approximately 16,000 feet (This was the approximate height at the time of the incident estimated upon our return.) the plane iced up and went out of control. I did not have my head-set on, so I could not say what conversation followed. However, I noticed the bomb-bay doors opening, and the bombs were salvoed.

My parachute was in back of me and upon seeing this I turned around to get it. When I looked forward again someone was standing on the catwalk, whom I later found out to have been our navigator. By this time we were about 10,000 feet, and the ship seemed to be under control. We were under the overcast as I could see the Channel.

Between the time that we were given the word to return and the time of the incident, the remainder of the ships in our group had left us. About a half hour later I went up front and found out that Lt. Watson, our acting co-pilot and Sgt. Christley, the engineer, had bailed out. This was done while my back was turned looking for my parachute, so that I did not see them jump.

As we neared the English coast two Spitfires, which were flying around, motioned for us to follow them, and we landed at their base. Major Ives called our field and reported the incident. Then we gassed up and left for our home field.

I would appreciate your advising me of any information concerning Lt. Watson and Sgt. Christley. I trust that this account will be of some help.

Sincerely,

Martin S. Cohen

__________

And, here’s T/Sgt. Smerek’s statement:

Sept. 9, 1945

In Regard to AFPPA-8-JH

Dear Sirs: –

A few days ago I received a letter in regard to a mission in which I participated on Nov 29, 1943, and asking me to give information about S/Sgt. Curtis L. Christley, who was engineer gunner on the same plane. It’s been a long time and I don’t remember very clearly just what happened. But here it is – as much as I remember.

We were flying lead ship in a formation of 18 planes. Major Ives was the pilot and my regular pilot Lt. Jesse Watson was flying as co-pilot because they were breaking him in as flight leader. Christley was the engineer and the other members of the crew were Lt. Neal bombardier; Lt. Arthur Newett navigator and Sgt. Martin Cohen as tail gunner.

We hit some bad weather over the Channel and it kept getting worse. We kept on climbing to get over the bad stuff and then I got the message over the radio that we were recalled back to our base. I called Maj Ives on interphone and he acknowledged. He gave the message to the rest of the formation and we started back. There was plenty of ice on the windows at this time and I noticed the altimeter as being over 15,000 ft. Then Maj Ives yelled over the inter phone to bail out. At that time I noticed the bomb bay doors opening and the bombs being salvoed. Lt Watson pulled his co pilot seat back and all in the same motion went through the radio room and jumped out the bomb bay. Sgt. Christley watched him go by and promptly put his chute on and followed him out.

I was busy sending out an S.O.S. and giving Lt. Neal a hand in fastening his individual dinghy to his ‘chute harness. Lt Newett sat on the door between the radio room and the bomb bay and wasn’t sure whether he wanted to go or not. At about that time Lt. Neal was motioned up front by the pilot and Maj Ives evidently had the plane under control again for no one else left the plane. It all happened just that quickly. When I noticed the altimeter again it read 700 feet.

I immediately contacted Air Sea Rescue and sent my message in the clear telling them that two men had bailed out and giving them the approximate position which I received from the navigator. I kept in constant contact with them until we landed at some base – which incidentally they directed us to.

That’s just about all that happened. I saw Christley and Watson go and I wasn’t too eager to go until I had to! I was questioned about this same matter when I was in France last November. I hope I have managed to help you in some small way. I never did hear anything about either one of the men and was hoping to hear that they were prisoners of war. I’d be glad to hear from you if you decide on anything definite.

Respectfully

Andy Smerek

__________

The photo below (discovered via Pinterest, and then flickr) shows Captain Thomas H. Wakeman, Jr., and his crew standing before B-26B Marauder “Lil Grim Reaper” (or, “Underground Farmer“) / “KX * K” (42-31640) of the 387th Bomb Group’s 558th Bomb Squadron. The plane was lost in an accident on June 8, 1944.

Captain Wakeman

2nd Lt. William N. Schreiber – Co-Pilot

1st Lt. Kenneth A. Omstead – Navigator / Bombardier

S/Sgt. Ferdinand P. Brabner, Jr. – Flight Engineer / Gunner

S/Sgt. Paul M. Tarrant – Radio Operator / Gunner

Martin S. Cohen – Tail Gunner (At the time, listed as a PFC)

Born on June 7, 1922, S/Sgt. Martin S. Cohen (13098524) survived the war. He as awarded the Air Medal, 11 Oak Leaf Clusters (thus implying between fifty-five and sixty missions), and Purple Heart.

The son of Harry T. Cohen, he was born on June 7, 1922, and lived 3831 Pennsgrove Street in Philadelphia. During the war, his name appeared in both the Philadelphia Inquirer and Philadelphia Record, on November 18, 1943. His name can also be found on page 516 of American Jews in World War II. He passed away on February 4, 2006.

References

Dublin, Louis I., and Kohs, Samuel C., American Jews in World War II – The Story of 550,000 Fighters for Freedom, The Dial Press, New York, N.Y., 1947

Morris, Henry, Edited by Gerald Smith, We Will Remember Them – A Record of the Jews Who Died in the Armed Forces of the Crown 1939 – 1945, Brassey’s, United Kingdom, London, 1989

Morris, Henry, Edited by Hilary Halter, We Will Remember Them – A Record of the Jews Who Died in the Armed Forces of the Crown 1939 – 1945 – An Addendum, AJEX, United Kingdom, London, 1994

South African Jews in World War Two, Eagle Press, South African Jewish Board of Deputies, Johannesburg, South Africa, 1950