“As I said, it was not spectacular work. It was not marked by any act of exceptional heroism. It was simply physical and spiritual sacrifice, the incessant labor that required heart and endurance to the highest degree.”

________________________________________

The past – whether the past of an individual or the past of a nation – can be a little like a Russian Matryoshka doll: As one figurine is concealed within another, within another (within yet another…), so too can historical records and human memory lead from one facet of history to another.

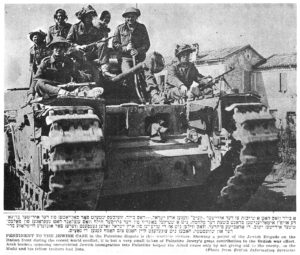

And so, the story of the Jewish Infantry Brigade – in the context of Jewish military history during the Second World War might – leads to and reveals another aspect of the military service of the Jews of the Yishuv: The participation of Jewish volunteers in service and support units of the British Eighth Army in North African and Italy. Though by nature less dramatic and perhaps of far less symbolic portent than the story of the Jewish Brigade, the service of these soldiers, in units engaged in camouflage, construction, stevedore work, supply, and transportation (often unheralded in most armies) was nonetheless absolutely essential to the Allied victory in the Mediterranean Theater.

____________________

To place this article in a larger context, here’s a diagrammatic map of the war in North Africa, from Lukasz Hirsowicz’s The Third Reich and the Arab East. The map is very cleverly designed in showing geographic boundaries, the locations of principal cities, routes and destinations of naval convoys, air activity, and above all, the timing and furthest geographic extent of Allied and Axis military offensives in Libya and Egypt. Note that the closest approach of Axis forces to Cairo, the Suez Canal, and the Yishuv – during the battle of El Alamein – was attained on July 1, 1942, after which offensive momentum finally and completely (but not easily) switched to the Allies.

____________________

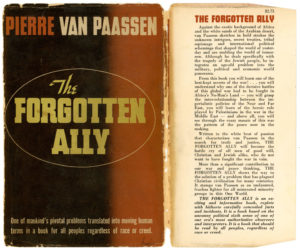

During the war, the topic was prominently covered in two books: Israel Cohen’s short but substantive Britain’s Nameless Ally (1942), and Pierre Van Paassen’s inspiring, insightful, and disillusioning The Forgotten Ally (1943). In the former, in Chapter IV – “The Best-Kept Secret of the War” – pp. 175-236; in the latter, in Chapter II – “The Rallying of Jewish Volunteers” – pp. 10-17, and, Chapter III – “At the Battle-Fronts” – pp. 18-28.

The image below shows the front cover of the 1943 (first) edition of The Forgotten Ally…

…and, here’s the back cover.

I found my copy at a used bookstore (remember book stores?) on June 2, 2001. The book is exceptional in terms of Van Paassen’s writing style, his perspective on Jewish history, Jewish peoplehood, Jewish nationalism, and geopolitics, with insights relevant well beyond the world of 1943.

The story was also reported in the print media, but aside from one article in The Jewish Exponent (“Jews Fight For Egypt” by Jesse Z. Lurie, on July 24, 1942), but this news coverage of the topic seems to have been largely the focus of Jewish newspapers published outside of the United States, specifically the Yishuv, England (The Jewish Chronicle), and elsewhere.

And example of this – an extremely informative example, at that – from elsewhere – from Egypt, to be specific – follows below.

On April 5, 1944, La Tribune Juive (translated title: The Jewish Tribune), a “French language weekly published in Cairo and Alexandria between the years 1936-1948,” published an article by Major L. Rabinovitz (Chaplain to the Forces, attached to the 8th Army) entitled “Les troupes juives dans la victoire du Désert” (“Jewish Troops in the Victory of the Desert”). The piece – lengthy, detailed, specific (very specific!) in terms of revealing the designations of military units (such as the 462nd General Transport Company, the subject of the very first posts at this blog) – provides fascinating insight into this story.

This is the article as it appears on La Tribune Juive’s front page; it extends several pages into the body of the newspaper.

Major Rabinovitz’s article is presented in its entirety below: First in the original French, and then, an English-language translation.

________________________________________

Une glorieuse épopée

Les troupes juives dans la victoire du Désert

par le Major L. RABINOVITZ, CF.,

Ancien Aumônier Juif en chef, attaché à la 8ème Armée.

LE Général Commandant en Chef désire mettre en relief les actes de bravoure accomplis par les suivants:

Lieutenant H.A.T. Rosser (Royal Engineers), Sergent-Major E. Silberman, Caporal Y. Filar, Lance-Caporal S. Reiser, Lance-Caporal B. Klioth, Sapeur S. Trebitsch et Sapeur S. Gesusdheit faisant lous partie de la Compagnie Palestinienne chargée d’opérations de Port.

«Vers 14 heures, le 14 Avril 1943, l’alarme fut donnée à la suite d’un incendie qui avait éclaité à bord du navire «Océan Strength» transportant des bidons de benzine destinas à être déchargés. Le Lieutenant Rosser s’élance immédiatement vers l’écoutille avec son extincteur d’incendie, ordonnant à ses hommes de le suivre. Sans aucune hésitation, ils le suivirent vers ce qui paraissait être une mort certaine. On pouvait apercevoir la fumée s’échappant du fond de la cale. Le Lieutenant Rosser se fit un chemin à travers cette fumée, levant des planches de bois et des bidons de benzine afin d’arriver au foyer de l’incendie. Ayant donné ordre aux hommes qui le suivirent vers cette partie de la cale d’actionner les extincteurs d’incendie en cet endroit, il s’approcha encore pour connaître exactement l’emplacement du feu. Les flammes atteignirent l’arrière du navire. Le Lieutenant Rosser demanda alors à l’équipage d’un chaland amarré aux côtés du navire de passer le manche de son tuyau d’incendie. L’embarcation avait déjà pris le large, mais agissant d’après les instructions formelles du Lieutenant Rosser, l’équipage ramena celle-ci aux côtés du bateau et le manche d’incendie, passant de main à main fut amené jusqu’à la chambre des machines.

«Le Sergent-Major Silberman, le Caporal Filar et les autres memtionnés ci-haut demeurèrent dans la cale jusqu’à ce que les éjecteurs à vapeur eussent été mis en action; c’est alors seulement qu’ils reçurent l’ordre de quitter les lieux. Le Lance-Caporal Reiser fat le dernier homme à sortir de la cale à un moment où les nuages de vapeur et la fumée qui s’élevaient de la cale empêchaient de distinguer à l’intérieur les formes humaines.

«Le Sergent-Major Silberman et le Caporal Filar se distinguèrent tout particulièrement, montrant ainsi un bel exemple. Après avoir quitté la cale, ils travaillèrent à la remise en place des poutres enlevées et à recouvrir les panneaux des écoutilles. La conduite du Lieutenant Rosser fut une haute démonstration du courage. Par son exemple, il incita ses hommes à le suivre dans une entreprise hasardeuse et réussit ainsi à maîtriser le feu.

«Le Général Commandant en Chef donne ordre que mention en soit faite dans les «Records de Service» du Lieutenant Rosser et dans les certificats de conduite des autres militaires mentionnés, en vertu des articles 171 et 1818 (b) des Règlements du Roi, 1940.»

Ce qui précède est un extrait des Ordres du Jour de la Huitième Armée, signés par le Général Sir Bernand Law Montgomery, K.C.B., D.S.O., et se réfère évidemment à une des Unités Juives qui prirent part à sa campagne victorieuse. On pourrait probablement et sans grande difficulté retrouver des actes aussi louables de bravoure dans les annales de guerre des autres unités palestiniennes qui participèrent aux glorieux exploits de cette célèbre armée.

Cependant on donnerait une idée entièrement fausse et déformée du travail essentiel exécuté par ces unités qui acquirent l’honneur et la gloire, donnèrent «le sang, la sueur, les larmes et les peines» qui ont forgé la victoire. J’espère ardemment que l’historien futur des volontaires Juifs Palestiniens pour la Guerre de la Liberté résistera à la tentation de représenter ces actes isolés (qui ne sont seulement possibles que lorsque d’extraordinaires opportunités se présentent) comme typiques ou caractéristiques. J’espère qu’il s’abstiendra de représenter celle besogne comme une succession d’actes de bravoure et d’exploits héroïques des «unités des lignes du front» dans «l’avance sous une véritable rafale de bombes et de feu d’artillerie» ou d’avenIures au caractère élevé. Non seulement ce serait faux, mais ce serait un mauvais service rendu h l’histoire moins spectaculaire mais non moins impressionnante de leurs réalisations pratiques.

La «Première» Huitième Armée

La Huitième Armée n’est pas née avec le Général Montgomery et aucune histoire de cette force redoutable et des Unités Juives qui en firent partie ne peuvent être complètes sans une référence à la Huitième Armée d’avant «Monty». Ses avances ne doivent pas être rappelées avec dédain, et ses revers ont simplement servi à la forger en l’instrument puissant qu’elle devint entre ses mains. Mais il y a des raisons spéciales pour mentionner, les Unités Juives qui y prirent part, 1o.) Dans un but de comparaison, 2o.) parce que deux des trois unités ont cessé d’exister. Elles ont passé hors de l’histoire sans recevoir des honneurs ni être chantées. Honorées, elles doivent l’être et si on ne peut les chanter, ce serait une erreur de laisser la muse absolument silencieuse à leur égard.

Passons donc grièvement en revue la Huitième Armée de Cunningham et de Ritchie, de Novembre 1941 à Juillet 1942, de l’avance de Sidi Barrani à El Agheila et de la retraite par étapes de Gazala à El Alamein.

Sans même essayer de faire une comparaison ridicule et déplacée avec la Huitième Armée qui lui succéda, il est nécessaire de souligner que la technique de la guerre du désert était beaucoup plus caractéristique chez cette Force que dans celle qui lui a succédé. Solloum, la Passe de Halfaya et Bardia étaient solidement tenus par les Allemands jusqu’à la mi-Janvier 1942 et une attaque le long de la route cotière était impraticable. Sur n’importe quel point entre le kilomètre 62 après Marsa Matrouh et Sidi Barrani, c’était dans une direction sud le désert complet et toute trace de cette route disparaissait. A travers les immensités désertiques sans chemins à l’exception des multitudes de pistes confuses créées par le passage des milliers de véhicules, on se «perdait dans le bleu». Un compas de navigation était le seul guide sûr, à condition que le détenteur fut un navigateur expérimenté. Une ligne ferrée était pour l’égaré comme un phare pour le marin à bord d’un navire naufragé, un fil télégraphique constituait pour lui fa meilleure des routes. Même après la levée du siège de Tobrouk et la chute conséquente de la Passe de Halfaya, alors que la route était ouverte, le trafic incessant et les tentatives continuelles quoique infruclueuses de déborder et d’intercepter l’ennemi, amenèrent la Huitième Armée à s’enfoncer profondément dans le désert en de vastes mouvements d’encerclement. L’eau était rare, la nourriture se confinait à des biscuits et à la viande en conserve, les boissons n’existaient point; les oeufs étaient un rêve du passé et les vitamines de table remplaçaient les légumes. Ce fut une époque de dure épreuve pour ce courage élevé qui se rit des plus grandes et inimaginables difficultés, et cette épreuve fut traversée par les Unités Juives avec l’étendard bien haut.

Les unités des sapeurs

Il n’y en avait que trois: les 601ème et 609ème «Pioneer Compagnies» et la 5ème Water Tank Coy (R.A.S.C.). Les deux premières n’existent plus pour des raisons qui sont à leur honneur mais leur oeuvre ne peut être oubliée. La première était constituée rie vétérans éprouvés. En tant que 401ème Compagnie A.M.P.C., elle fut la première Unité Palestinienne à être formée. Ses membres servirent en France et s’acquittèrent glorieusement de leur tâche à Saint-Malo. Au cours de la débâcle française, ils furent évacués en Angleterre. Retournant dans le Moyen-Orient, ils fournirent la plus grande partie du 51ême Grôupe du «Middle East Commando» et, autant que je le sache, forma la première Unité Palestinienne (bien que le terme «palestinien» n’ait jamais été mentionné) à figurer dans l’Histoire Officielle. El à l’ouverture de la campagne de la Huitième Armée, ils comptaient le plus long record de temps de service sans être relevés (14 mois) que n’importe quelle unité dans le désert. La 609ème compagnie avait été formée juste au moment de la défaite de Crète et évita donc le destin qui s’abattit sur ses compagnies-soeurs à l’exception de la 601ème.

Aussi singulier que cela puisse paraître pour d’humbles Sections de Sapeurs durant les semaines qui précédèrent l’ouverture de la campagne, il n’y avait, entre elles et un ennemi puissant et bien équipé, que des patrouilles blindées mobiles. J’étais avec eux en leur disant: «Depuis aujourd’hui, la Huitième Armée passera à l’Histoire. Aussi humbles que puissent paraître les missions qui vous auront été confiées, lorsque vous entendrez les exploits de cette armée, n’oubliez point ou ne manquez jamais de ressentir la fierté méritée du fait que vous en êtes une partie intégrante».

Dans la première poussée, la 601ème compagnie avança aussi loin que Tobrouk. Comme par miracle, elle fui évacuée quelques jours avant que la ville ne tombe, à une date historique pour elle, le 15 Juin. C’est en ce jour, en 1940, qu’elle fut évacuée de France. C’est en ce jour en 1941, qu’elle fut évacuée de Buk-Buk face à l’avance allemande. C’est en ce jour qu’elle fut évacuée aussi de Tobrouk pour quitter la Huitième Armée et, avec toutes les autres compagnies palestiniennes de sapeurs, elle fut dispersée pour être affectée à des tâches plus utiles.

La 5ème Water Tank Coy (R.A.S.C.), la seule unité palestinienne dans l’armée de Ritchie à avoir pris part aux deux campagnes et à la retraite intermédiaire, fut un signe avant-coureur des faits à venir. Ce fut le jour de Kippour, en 1941, qu’ils quittèrent leur base pour le Service Actif qu’ils effectuèrent sans une pause jusqu’au moment où j’écris ces lignes.

Ils transportèrent dé l’eau à des distances aussi éloignées que Benghazi et une de leurs sections fut presque isolée là-bas. Dans la retraite conséquente à la chute de Tobrouk ils se distinguèrent en devenant pratiquement la seule unité à ramener tous ses camions. En fait, si l’on veut dire toute la vérité, ils ramenèrent même quelques véhicules abandonnés. Ils devinrent un synonyme d’efficience pour la «bonne livraison des marchandises» et ils gagnèrent un surnom qui est le signe de l’efficience. Ils furent populairement connus sous le nom de la «Cinquième Volante» (Flying Fifth). Mais une chose était commune à toutes ces unités au début de la campagne: Leur Commandant, son second ainsi que gon Etat-Major étaient tous Britanniques. Les unités palestiniennes n’avaient pas encore gagné leurs chevrons et avaient encore à être commandées par des officiers britanniques. Ailleurs la remise du commandement à des officiers palestiniens avait eu lieu mais ici je me confine à parler de la Huitième Armée seulement. Ses unités juives formaient une quantité inconnue et leurs capacités avaient encore à être éprouvées.

Camouflage et transport

De ce début peu prometteur naquirent les groupes qui devaient former la contribution des unités juives à la campagne victorieuse du Général Montgomery. Après la chute de Tobrouk, la «Cinquième Volante» fut la seule à subsister des trois unités originaires. Durant les jours critiques d’El Alamein, deux autres unités se joignirent à elle et remplirent leur part: la 738ème Artisan Works (R.E.), première unité palestinienne des Royal Éngineers et la seule à devenir complètement palestinienne, et la 1ère Camouflage Coy, R.E., unité d’opérations et, comme son nom l’indique, la première de son genre. Lorsque, après la première percée victorieuse, Mr. Winston Churchill attribua cette victoire en partie au «brillant système de camouflage», il faisait allusion à l’oeuvre accomplie par cette unité. Le récit officiel de la Bataille de l’Egypte décrit plus complètement une partie de leur travail dans le passage suivant: «L’équilibre favorable a été assuré non pas par les nouvelles tactiques britanniques seulement mais aussi par des surprises lactiques complètes. Le 10ème corps consistant en deux divisions blindées et les divisions d’infanterie néo-zélandaises campant pour l’entraînement dans le Delta bien loin derrière les champs de bataille. Autant que les reconnaissances aériennes ennemies pouvaient le constater, ces forces armées étaient encore là pour l’ennemi jusqu’au 22 Octobre, la veille de l’attaque. Mais en fait, elles n’étaient plus là. Tout le corps d’armée laissant derrière lui un camp mort avait été transféré vers les lignes du front». Ces deux unités furent retirées: la 738ème Compagnie d’abord et la 1ère compagnie de camouflage après que la bataille eut été déclenchée; à part un petit détachement de cette dernière unité attaché durant la bataille au Quartier-Général de la 8ème Armée pour le camouflage et dont le personnel furent les premiers Palestiniens à porter l’insigne tant convoité de la 8ème Armée, elles ne prirent pas part à l’avance victorieuse. Une petite unité palestinienne des Royal Engineers fut représentée aussi, ainsi qu’une unité de topographie qui prépare et remet les Cartes jusqu’au front, et une autre qui mérite et doit avoir une mention spéciale.

Mais pendant que le Général Montgomery était engagé dans ses fiévreuses préparations, une autre sorte de préparation se déroulait parmi les unités palestiniennes. Les deux unités de Vétérans du R.A.S.C., les 5ème et 6ème Works Service Coy qui prirent part toutes deux à l’avance-éclair du Général Wavell, furent chacune divisée en deux et ces parts furent consolidées et transformées en compagnies de Transport général et devinrent complètement palestiniennes. La 6ème Work Service Coy forma les 179ème et 462ème compagnies et la 5ème Work Service Coy devint les 178ème et 468ème compagnies. Cette dernière reçut les personnes de grade médicalement inférieur et fut envoyée en Palestine. Les autres furent préparées et équipées pour devenir des unités d’opérations. Tout le cadre – Officier Commandant, son second et l’Etat-Major — était Palestinien.

La 5ème Water Tank Coy avait déjà subi ce changement. Une autre compagnie similaire, la 11ème, fut formée selon l’ancien système et ne reçut son propre Officier Commandant qu’au milieu de la campagne. La 1030èine Port Operating Coy, R.E., demeura avec son commandant britannique jusqu’à la fin de la bataille.

L’arrivée de la 462ème compagnie dans la Huitième Armée ne manqua pas de dramatique. Elle se trouvait en Syrie quand Tobrouk tomba. Elle transporta en nâte les Néo-Zélandais jusqu’aux voies ferrées, accourut en Egypte pour amener les Australiens en première ligne puis fut atachée à la 26ème Brigade Australienne. Ce furent les premiers Palestiniens à servir comme troupes de brigade. Là ils versèrent leur sang et connurent leurs premières pertes humaines, et non les dernières, et là, pour la première fois, contrairement aux stricts règlements militaires certains de leurs chauffeurs acceptèrent avec joie l’invitation des Australiens peu formalistes de se joindre à eux dans l’attaque.

Ainsi de gloire en gloire. Un matin de Yom Kippour, ils reçurent l’ordre d’avancer. L’aumonier à son réveil trouva comme plafond le ciel bleu et non sa tente, car les soldats le voyant endormi enlevèrent silencieusement la tente lorsqu’ils reçurent Tordre de transfert. La 462ème Coy avait rejoint le 10ème Corps établissant un record militaire palestinien.

Résumons ces mois de préparation.

La veille de la bataille, les unités juives suivantes se trouvaient avec la Huitième Armée:

La «Cinquième Volante», la 462ème General Transport Coy, la moitié de la 179ème exécutant une besogne dangereuse très avant des lignes; la 1ère Camouflage Cy R.E.; l’Unité Topographique R.E. Attendant les ordres du Centre des Mobilisations, se trouvaient la 178ème Compagnie, la 11ème Water Tank Coy et l’autre moitié de la 179ème Coy. La 1030ème Port Operating Cy, R.E., avait été rartîenée d’Akaba et se trouvait en Palestine dans l’attente.

Avec les Vainqueurs du Désert

ARTHUR Brejant correspondant permanent de l’Illustrated London News, commence ainsi sa revue de la Victoire Nord-Africaine:

“Honneur à ceux qui le méritent! Si jamais victoire fut remportée, c’est bien en Tunisie. Elle a été gagnée d’abord par cette merveilleuse Huitième Armée transformée, par un effort incessant, une expérience éprouvée et un brillant commandement, d’une compagnie d’amateurs héroïques, en une légion de vétérans professionnels capables d’être comparés et même de dépasser les troupes les plus brillantes du monde, une armée qui après toutes ses vicissitudes ouvrit les portes du désert, effectua une avance de 2000 milles environ et à l’extrême limite de sa fantastique ligne d’epprovisionnement força la puissante et apparemment infranchissable ligne du Mareth.

«Amateurs… transformés en «soldats professionnels» comme cette expression est exacte pour les diverses unités Palestiniennes qui furent appelées à remplir leur part dans la Victoire du Désert! Amateurs, ils l’étaient dans chaque sens du terme et devinrent sans aucun doute de soldats professionnels endurcis. Ils étaient amateurs infiniment plus que tout le reste de la Huitième Armée. On ne distinguait pas en eux l’étoffe du militaire professionnel, pas plus qu’ils ne possédaient une longue tradition militaire. A ces difficultés premières venaient s’ajouter d’autres non moins sérieuses: Les éléments fantastiquement hétérogènes que forme le Judaïsme Palestinien, citoyens et «Kibboutznik» (membres des «Kibboutzim» ou colonies collectivistes), originaires d’Allemagne et de Pologne, de Hongrie et de Roumanie, les Yéménites et les «Sabrés» (Juifs nés en Palestine); le caractère extrêmement individualiste du juif, tout particulièrement du Juif Libre de Palestine qui le rend moins volontairement apte à l’obéissance sans discussion et la discipline rigide; et enfin, le problème formidable des langues; mais en dépit de tous ces facteurs défavorables, ces amateurs devinrent des «soldats professionnels».

«C’était aussi, en vérité, une «ligne d’approvisionnement fantastique»; et pour maintenir cette ligne intacte on exigeait du «Transport général» l’adoption de mesures non moins «fantastiques». C’est dans cette branche d’activité que tes Palestiniens montrèrent leur bravoure.

«La Victoire du Désert se divise en deux phases clairement définies: Depuis l’ouverture de l’attaque le 23 Octobre jusqu’à la rupture du front ennemi le 2 Novembre ce fut une attaque frontale dans le sens de la véritable tradition classique militaire à laquelle vient s’ajouter cette tactique géniale qui la rendit historique. Depuis, et jusqu’à la fin, ce fut une poursuite incessante d’un ennemi battu mais non démoralisé, une tentative continue d’encerclement. Ceux qui prirent part à cette poursuite peuvent témoignei des énormes difficultés qu’il fallut surmonter. L’ennemi se retirait sur une route libre (à part les attaques aériennes) et unie — la fameuse Via Balbo — choisissant en fait des lignes de communication plus courtes encore. Dans sa retraite, il détruisait les ponts, minait lés chemins, posait partout des pièges utilisant toutes les méthodes de retardement qu’un ennemi avisé et résolu peut imaginer. A mesure qu’il reculait, nos lignes s’alongeaient sans cesse jusqu’à ce qu’il sembla qu’elles avaient atteint le maximum possible. Et s’il existe vraiment une plainte qu’un Aumônier puisse formuler à son Créateur, c’est pour les facteurs atmosphériques qui ne cessèrent de favoriser l’ennemi — ciel sans nuage en France durant l’avance hitlérienne en Mai-Juin 1940 comparé aux pluies tout à fait imprévues dans la région de Martuba Usus en Janvier 1943, sans lesquelles Rommel dans sa fuite se serait déjà trouvé «dans le sac».

«En d’autres termes, ce fut une bataille d’approvisionnements et si, comme il a été établi, nos éléments avancés ne perdirent jamais contact avec l’arrière-garde ennemie, aucun hommage ne sera assez grand envers l’organisation de nos lignes de communication el d’approvisionnements.»

Le maintien des lignes vitales.

Telle fut la tâche des unités Palestiennes. Las mais infatigables, épuisés mais inépuisables, farouches et déterminés ils apportaient à l’avant les vivres. A travers les tempêtes de sable et la poussière, la boue et la pluie, par la route, la piste désertique, durant le jour et la nuit ils volaient à l’avant, battant tous les records de temps et les horaires fixes, leur va-et-vient continuel s’intensifiant à mesure que les besoins augmentaient. Malgré l’immense supériorité aérienne de la R.A.F., la Luftwaffe n’était pas inactive. Chaque unité eut ses pertes, à la suite des bombardements, de l’explosion des mines, des pièges, des accidents, et cette longue rouie, comme les cimetières militaires qui l’accompagnent, est semée de «Maghen David», mais «notre marche se poursuit à jamais quoique nous tombons un à un».

Ainsi que je l’ai dit, ce ne fut pas une oeuvre spectaculaire. Elle ne l’ut marquée par aucun acte d’héroïsme exceptionnel. C’était simplement des sacrifices physiques et spirituels, le labeur incessant qui demandait du coeur et de l’endurance au plus haut degré. Une seule fois je vis une unité atteindre ce que je craignais être le point de rupture, mais une réunion, un chaleureux appel de l’Aumônier et du Commandant, une franche discussion d’homme à homme; et la crise fui surmontée.

Rommel décida de faire une halte à El Agheila. La décision fut presque une bénédiction, si on peut employer ce terme, à notre système d’approvisionnement, tellement mis à contribution, et donnant une période – le temps de respirer – pour accélérer renvoi dos fournitures et encore de provisions pour la nouvelle phase de l’avance. Cette période fut les beaux jours des unités palestiniennes. La 1039ème Compagnie avait été amenée à Tobrouk (incidemment elle y tut transportée par une autre unité palestinienne) et se mil rapidement en action de sorte que le port fut bientôt en mesure d’être utilisé. Ils déchargèrent ensuite les navires et la mission d’effectuer les chargements jusqu’à Benghazi fut confiée aux unites palestiniennes de transport. Chacune d’entre elles prit part à cette étonnante procession de 24 heures par jour. Des centaines de véhicules, conduits par des soldats juifs pouvaient être aperçus à n’importe quel moment du jour dans les deux directions de la «course» Tobrouk-Benghazi, transportant de la benzine, les rations d’eau, des hommes, munitions, tout en somme. Dans cette concentration, ils furent faciles à remarquer. C’est durant cette période qu’ils acquirent leur excellente réputation actuelle qui elevait être confirmée au cours des opérations suivantes. Durant les opérations futures, ils furent également là. De Benghazi, ils allèrent de l’avant jusqu’à Tripoli. Quelques unités atteignirent ce but; deux d’entre elles avant que la campagne Nord-Africaine eut élé terminée furent choisies «pour un important rôle opérationnel» et furent envoyées à Malte en préparation du victorieux assaut contre la Sicile. Un désastre s’abattit sur l’une d’elles qui eut à déplorer la perle de 140 d’entre ses hommes.

Mais en suivant les vicissitudes des diverses unités du R.A.S.C., on ne doit pas oublier l’honneur qui revint à la 1039ème Port Operating Company, R.E., la première unité palestinienne a atteindre Tripoli le 24 Janvier 1943, le lendemain de la capture de la ville par la victorieuse 8ème Armée.

________________________________________

A Glorious Epic

Jewish Troops in the Victory of the Desert

by Major L. RABINOVITZ, CF.,

Former Jewish Chaplain in Chief, Attached to the 8th Army.

The General Commander-in-Chief wishes to highlight the acts of bravery accomplished by the following:

Lieutenant H.A.T. Rosser (Royal Engineers), Sergeant Major E. Silberman, Corporal Y. Filar, Lance Corporal S. Reiser, Lance Corporal B. Klioth, Sapper S. Trebitsch and Sapper S. Gesusdheit forming part of the Palestinian Company in charge of Port operations.

“At about 14:00 hours, on April 14, 1943, the alarm was given following a fire that had broken out on board the vessel Ocean Strength carrying cans of benzine destined to be unloaded. Lieutenant Rosser immediately rushed to the hatch with his fire extinguisher, ordering his men to follow him. Without hesitation, they followed him to what appeared to be certain death. One could see the smoke escaping from the bottom of the hold. Lieutenant Rosser made his way through the smoke, lifting planks of wood and cans of benzine to reach the fire. Having ordered the men who followed him to this part of the hold to operate the fire extinguishers in this place, he again approached to know exactly the location of the fire. The flames reached the rear of the ship. Lieutenant Rosser then asked the crew of a barge moored alongside the ship to pass the handle of its fire hose. The boat had already sailed, but acting according to Lieutenant Rosser’s formal instructions, the crew brought it back to the sides of the boat and the fire hose, passing from hand to hand, was brought to the ship’s engine room.

“Sergeant-Major Silberman, Corporal Filar, and the other members above remained in the hold until the steam ejectors were put into action; it was only then that they received the order to leave the place. Lance Corporal Reiser was the last man to come out of the hold at a time when the clouds of steam and smoke rising from the hold made it impossible to distinguish the human forms inside.

“Sergeant-Major Silberman and Corporal Filar stood out in particular, showing a fine example. After leaving the hold, they worked to replace the removed beams and to cover the panels of the hatches. Lieutenant Rosser’s conduct was a great demonstration of courage. By his example, he incited his men to follow him in a hazardous enterprise and thus succeeded in controlling the fire.

“The General Commander-in-Chief orders that mention be made of this in Lieutenant Rosser’s “Service Records” and in the certificates of conduct of the other servicemen mentioned, pursuant to Articles 171 and 1818 (b) of the King’s Regulations, 1940.”

The above is an excerpt from the Eighth Army Orders of the Day, signed by General Sir Bernand Montgomery Law, K.C.B., D.S.O., and obviously refers to one of the Jewish Units that took part in his victorious campaign. One could probably and without much difficulty find such commendable acts of bravery in the annals of war of the other Palestinian units that participated in the glorious exploits of this famous army.

However, one would give an entirely false and distorted idea of the essential work performed by these units, which acquired honor and glory, and gave “the blood, the sweat, the tears and the sorrows” which forged the victory. I earnestly hope that the future historian of Palestinian Jewish volunteers for the War of Freedom will resist the temptation to represent these isolated acts (which are only possible when extraordinary opportunities arise) as typical or characteristic. I hope he will refrain from representing this task as a succession of acts of bravery and heroic exploits of “frontline units” in “advance under a veritable burst of bombs and artillery fire” or adventures of high character. Not only would it be wrong, but it would be a bad service to the less spectacular but no less impressive history of their practical achievements.

The “First” Eighth Army

The Eighth Army was not born with General Montgomery and no history of this formidable force and the Jewish Units that formed part of it can be complete without a reference to the Eighth Army before “Monty”. His advances should not be recalled with disdain, and his reverses simply served to forge it into the powerful instrument that it became in his hands. But there are special reasons for mentioning, the Jewish Units that took part in it, 1o.) For comparative purposes, 2o.) Because two of the three units ceased to exist. They have gone out of history without receiving honors or being sung. Honored, they must be and if we can not sing about them, it would be a mistake to leave the muse absolutely silent about them.

So let us review the Eighth Army of Cunningham and Ritchie, from November 1941 to July 1942, the advance of Sidi Barrani at El Agheila and the phased retirement from Gazala to El Alamein.

Without even trying to make a ridiculous and inappropriate comparison with the Eighth Army that succeeded it, it is necessary to emphasize that the technique of the desert war was much more characteristic of this Force than of that which succeeded it. Solloum, Halfaya Pass and Bardia were solidly held by the Germans until mid-January 1942 and an attack along the coastal road was impracticable. On any point between kilometer 62 after Mersa Matruh and Sidi Barrani, it was in a southerly direction [of] the complete desert and all trace of this road disappeared. Through the desertless vastnesses without paths except for the multitudes of confused tracks created by the passage of thousands of vehicles, one gets “lost in the blue”. A compass was the only safe guide, provided that the holder was an experienced navigator. A railroad was for the lost as a lighthouse for the sailor aboard a wrecked ship, a telegraph wire for him was better then roads. Even after the lifting of Tobruk’s siege and the consequent fall of the Halfaya Pass, while the road was open, the incessant traffic and the continual attempts, though subtle, to overflow and intercept the enemy, brought the Eighth Army to to sink deep into the desert in vast encirclement movements. Water was scarce, food was confined to biscuits and canned meat, drinks did not exist; eggs were a dream of the past and table vitamins replaced vegetables. It was a time of hardship for that high courage that laughs at the greatest and unimaginable difficulties, and this test was crossed by the Jewish Units with the high banner.

The Sapper Units

There were only three: the 601st and 609th “Pioneer Companies” and the 5th Water Tank Company (R.A.S.C.). The first two no longer exist for reasons that are to their credit but their work can not be forgotten. The first consisted of experienced veterans. As 401st Company A.M.P.C., it was the first Palestinian unit to be formed. Its members served in France and gloriously performed their task in Saint-Malo. During the French debacle, they were evacuated to England. Returning to the Middle East, they provided most of the 51st Group of the Middle East Commando and, as far as I know, formed the first Palestinian Unit (although the term “Palestinian” was never mentioned) to appear in the Official History. At the opening of the Eighth Army campaign, they had the longest record of service time without being relieved (14 months) than any unit in the desert. The 609th Company was formed just at the time of the defeat of Crete and therefore avoided the fate that fell on its sister companies with the exception of the 601st.

As peculiar as it may seem to humble Sappers’ Sections during the weeks preceding the opening of the campaign, there was only a mobile armored patrol between them and a powerful and well-equipped enemy. I was with them saying: “Since today, the Eighth Army will go down in history. As humble as the missions that may be entrusted to you may be, when you hear the exploits of this army, remember or never miss feeling the pride you deserve because you are an integral part of it.”

In the first push, the 601st company advanced as far as Tobruk. Miraculously, it was evacuated a few days before the city fell, at a historic date for it, on June 15. It was on this day, in 1940, that it was evacuated from France. It was on this day in 1941 that it was evacuated from Buk-Buk in the face of the German advance. It was on that day that it was also evacuated from Tobruk to leave the Eighth Army and, along with all the other Palestinian sapper companies, it was dispersed to work on more useful tasks.

The 5th Water Tank Company (R.A.S.C.), the only Palestinian unit in Ritchie’s army to take part in the two campaigns and the intermediate retreat, was a harbinger of future events. It was on Yom Kippur in 1941 that they left their base for Active Service, which they did without a break until I wrote these lines.

They carried water from as far away as Benghazi and one of their sections was almost isolated there. In the retreat consequent to the fall of Tobruk they distinguished themselves by becoming practically the only unit to bring back all its trucks. In fact, if one wants to tell the whole truth, they even brought back some abandoned vehicles. They became synonymous with efficiency for the “good delivery of goods” and they earned a nickname that is a sign of efficiency. They were popularly known as the “Fifth Flying Fifth”. But one thing was common to all these units at the beginning of the campaign: Their Commander, his second as well as the General Staff were all British. Palestinian units had not yet won their chevrons and had yet to be commanded by British officers. Elsewhere the handing over of command to Palestinian officers had taken place but here I confine myself to talking about the Eighth Army only. Its Jewish units were an unknown quantity and their abilities still had to be tested.

Camouflage and Transport

From this unimportant beginning came the groups which were to form the contribution of the Jewish units to the victorious campaign of General Montgomery. After the fall of Tobruk, the “Flying Fifth” was the only surviving of the three original units. During the critical days of El Alamein, two other units joined it and filled their part: the 738th Artisan Works (R.E.), the first Palestinian unit of the Royal Engineers and the only one to become completely Palestinian, and the 1st Camouflage Company, R.E., unit of operations and, as its name suggests, the first of its kind. When, after the first successful breakthrough, Mr. Winston Churchill attributed this victory in part to the “brilliant camouflage system”, he was referring to the work accomplished by this unit. The official account of the Battle of Egypt describes more fully part of their work in the following passage: “The favorable equilibrium was secured not by the new British tactics only but also by complete lactic surprises. The 10th Corps consisting of two armored divisions and New Zealand infantry divisions camping for training in the Delta far behind the battlefields. As far as enemy air reconnaissance could see, these armed forces were still there for the enemy until 22 October, the day before the attack. But in fact, they were no longer there. All the corps leaving behind a dead camp had been transferred to the front lines. These two units were withdrawn: the 738th Company first and the 1st camouflage company after the battle had been triggered; apart from a small detachment of this last unit attached during the battle to the Headquarters of the 8th Army for camouflage and whose staff were the first Palestinians to wear the coveted badge of the 8th Army; they did not take part in the victorious advance. A small Palestinian unit of the Royal Engineers was also represented, as well as a surveying unit which prepares and delivers the Maps to the front, and another which deserves and must have a special mention.

But while General Montgomery was engaged in his feverish preparations, another kind of preparation was taking place among the Palestinian units. The two Veterans units of the R.A.S.C., the 5th and 6th Works Service Companies, both of which took part in General Wavell’s advance, were each divided in two and these parts were consolidated and transformed into General Transport companies and became completely Palestinian. The 6th Work Service Company formed the 179th and 462nd companies and the 5th Work Service Company became the 178th and 468th companies. The latter received the medically inferior people and was sent to Palestine.

The 5th Water Tank Company had already undergone this change. Another similar company, the 11th, was formed under the old system and only received its own commanding officer in the middle of the campaign. The 1030th Port Operating Coy, R.E., remained with its British commander until the end of the battle.

The arrival of the 462nd Company in the Eighth Army did not lack drama. It was in Syria when Tobruk fell. It transported the New Zealanders to the railroad, flocked to Egypt to bring the Australians to the front line and was then assigned to the 26th Australian Brigade. These were the first Palestinians to serve as brigade troops. There they shed their blood and suffered their first human losses, not the last, and there, for the first time, contrary to the strict military regulations some of their drivers gladly accepted the invitation of the uninformed Australians to join them in the attack.

Thus from glory to glory. One morning of Yom Kippur, they received the order to advance. The chaplain at his awakening found the blue sky as his ceiling, not his tent, for the soldiers, seeing him asleep, silently removed the tent when they received the order of transfer. The 462nd Company joined the 10th Corps establishing a Palestinian military record.

Let’s Summarize These Months of Preparation.

The day before the battle, the following Jewish units were with the Eighth Army:

The “Fifth Flying”, the 462nd General Transport Company, half of the 179th performing a dangerous job very much before the lines; the 1st Camouflage Company R.E .; the R.E. Topographic Unit Waiting for the orders of the Mobilization Center, were the 178th Company, the 11th Water Tank Company and the other half of the 179th Company. The 1030th Port Operating Company, R.E., had been separated from Akaba and was in Palestine in expectation.

With the Desert Victors

ARTHUR Brejant permanent correspondent of the Illustrated London News, begins his review of the North African Victory:

“Honor to those who deserve it! If ever victory was won, it is in Tunisia. It was won first by this marvelous Eighth Army transformed, by an incessant effort, proven experience and a brilliant command, from a company of heroic amateurs, into a legion of professional veterans able to be compared and even to overcome the most brilliant troops in the world, an army that after all its vicissitudes opened the doors of the desert, made an advance of about 2,000 miles and at the extreme limit of its fantastic supply line forced the powerful and seemingly impassable line of the Mareth.

“Amateurs … turned into” professional soldiers” as this expression is accurate for the various Palestinian units that were called to fill their share in the Desert Victory! Amateurs, they were in every sense of the word and undoubtedly became hardened professional soldiers. They were amateurs much more than all the rest of the Eighth Army. They did not distinguish the professional soldier’s stuff, nor did they have a long military tradition. To these first difficulties were added others no less serious: The fantastically heterogeneous elements of Palestinian Judaism, citizens and “Kibbutznik” (members of “Kibbutzim” or collectivist colonies), originating in Germany and Poland, from Hungary and Romania, the Yemenis and the “Sabras” (Jews born in Palestine); the extremely individualistic character of the Jew, especially the Free Jew of Palestine who makes him less willingly able to obey without question and rigid discipline; and finally, the formidable problem of languages; but in spite of all these unfavorable factors, these amateurs became “professional soldiers”.

“It was also, in truth, a “fantastic supply line”; and in order to maintain this line intact the “General Transport” was required to adopt no less “fantastic” measures. It is in this branch of activity that the Palestinians showed their bravery.

“The Desert Victory is divided into two clearly defined phases: From the opening of the attack on October 23 until the rupture of the enemy front on November 2, it was a frontal attack in the sense of the true classical military tradition in which is added to this great tactic that made it historic. Since then, and until the end, it was a relentless pursuit of a defeated but undemoralized enemy, a continued attempt at encirclement. Those who took part in this pursuit can testify to the enormous difficulties that had to be overcome. The enemy withdrew on a free road (apart from air attacks) and united – the famous Via Balbo – choosing in fact shorter lines of communication. In his retirement, he destroyed bridges, mined paths, set traps everywhere using all the methods of delay that an informed and resolute enemy can imagine. As it receded, our lines were constantly lengthening until it seemed as if they had reached the maximum possible. And if there really is a complaint that a Chaplain can formulate to his Creator, it is for the atmospheric factors that did not cease to favor the enemy – clear sky in France during the Hitler’s advance in May-June 1940 compared to the unexpected rains in the region of Martuba Usus in January 1943, without which Rommel in his flight would have been “in the bag”.

“In other words, it was a battle of supplies and if, as it was established, our advanced elements never lost contact with the enemy rearguard, no tribute will be great enough to the organization of our lines of communication and supplies.”

Maintaining Vital Lines

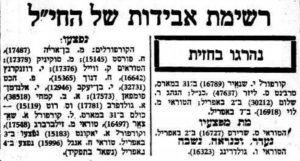

Such was the task of the Palestinian units. Weary but indefatigable, exhausted but inexhaustible, fierce and determined, they brought food to the front. Through sandstorms and dust, mud and rain, by the road, the desert track, during the day and the night they were flying in the front, beating all time records and fixed schedules, their going and continual increase as the needs increase. Despite the immense air superiority of the R.A.F., the Luftwaffe was not inactive. Each unit had its losses as a result of bombing, the explosion of mines, traps, accidents, and this long road, like the military cemeteries that accompany it, is strewn with “Magen David” but “our march goes on forever even though we fall one by one”.

As I said, it was not spectacular work. It was not marked by any act of exceptional heroism. It was simply physical and spiritual sacrifice, the incessant labor that required heart and endurance to the highest degree. Once I saw a unit reach what I feared to be the breaking point, but a meeting, a warm call from the Chaplain and the Commander, a frank discussion from man to man; and the crisis was overcome.

Rommel decided to stop at El Agheila. The decision was almost a blessing, if we can use that term, to our supply system, so much put to use, and giving a period – time to breathe – to speed up returning back of supplies and again provisions for the new phase of the advance. This period was the heyday of Palestinian units. The 1039th Company had been brought to Tobruk (incidentally it was transported there by another Palestinian unit) and moved quickly in action so that the port was soon able to be used. They then unloaded the ships and the mission to carry the loadings to Benghazi was entrusted to the Palestinian transport units. Each of them took part in this amazing procession of 24 hours a day. Hundreds of vehicles, driven by Jewish soldiers could be seen at any time of the day in both directions of the Tobruk-Benghazi “race”, carrying fuel, rations of water, men, ammunition, all in all. In this concentration, they were easy to notice. It was during this period that they acquired their excellent current reputation which could be confirmed during subsequent operations. During future operations, they were also there. From Benghazi they went on to Tripoli. Some units achieved this goal; two of them before the North African campaign was over were chosen “for an important operational role” and were sent to Malta in preparation for the victorious assault on Sicily. A disaster fell on one of them who had to bemoan the jewel of 140 of its men.

But by following the vicissitudes of the various units of the R.A.S.C., we must not forget the honor that went to the 1039th Port Operating Company, R.E., the first Palestinian unit to reach Tripoli on January 24, 1943, the day after the capture of the city by the victorious 8th Army.

References

Cohen, Israel, Britain’s Nameless Ally, W.H. Allen & Co., Ltd., Publishers, 43, Essex Street, Strand, London, W.C.2., 1942

Hirsowicz, Lukasz, The Third Reich and the Arab East (translated from the Polish), Routledge & K. Paul, London, England, 1966

van Paassen, Pierre, The Forgotten Ally, The Dial Press, New York, N.Y., 1943