Prior to researching Jewish military service in the French Army during the Great War, the story of Chief Rabbi Abraham Bloch was entirely unknown to me. Through a variety of digital and text sources, I soon learned more about his life, and in a larger context, the relationship of his story to the experience of French Jewry during that conflict, and beyond.

One excellent source of information about Rabbi Bloch appears within Philippe-E. Landau’s monograph, Les Juifs de France et la Grande Guerre (The Jews of France in the Great War). His chapter on the Rabbi is presented below, translated from the French.

Myth and Reality: The Death of Chief Rabbi Abraham Bloch

Les Juifs de France et la Grande Guerre / The Jews of France in the Great War (front cover)

Les Juifs de France et la Grande Guerre / The Jews of France in the Great War (front cover)

From 1915 to the defeat of 1940, Chief Rabbi Abraham Bloch’s death on the field of honor symbolizes the community’s communion of body and spirit with the nation. As much for Jewish youth as for the generations having lived the Great War, the image of Epinal represents the patriotic fidelity of French Judaism.

This pious picture, where the chief rabbi, then chaplain and stretcher-bearer, dies from his wounds in a shower of enemy fire after bringing a crucifix to a dying Catholic soldier, remains in the collective memory as “an image that will not perish” according to Maurice Barrés. (1)

Israelitism retained this event to claim its sacrifice during the ordeal. The death of the chief rabbi has also benefited from important publicity, if only by the enthusiastic article that Maurice Barres has given him. The information is then disseminated by the entire national press. Also, it is not just an episode limited to community history. By far, it goes beyond the denominational context because it is the very image of the Sacred Union. We cannot gauge the impact of this death on the post-war mentality, anxious to perpetuate the fraternity of the trenches.

The first simple fact of the day at the end of the year 1914, the event is growing in the pen of the nationalist writer who awakens more the patriotic ardor of Israelitism. The rabbis and the notables salute the glorious death of Abraham Bloch, but are however discreet on his famous gesture. Did he really bring a crucifix?

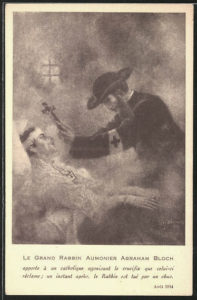

But enthusiasm prevails over reason. In 1917, once the press took hold of the story and the painter Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer fixed for eternity the gesture of the chief rabbi, the rabbinate agrees. Here is Abraham Bloch becoming a “martyr” for his co-religionists and “saint” for the nation.

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer‘s painting of Rabbi Abraham Bloch holding a crucifix before a dying soldier

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer‘s painting of Rabbi Abraham Bloch holding a crucifix before a dying soldier

Far from perishing, the image spreads in all Jewish families in the form of postcards and the memory of the Chief Rabbi is recounted in all the patriotic demonstrations that the community celebrates.

If, in the twenties, this episode comforts the Judaism which sees there the consecration, from the thirties, the death of the chief rabbi becomes the object of political recovery and patriotic outbidding. Veterans, especially those of the Patriotic Union of French Jews, use this symbolic image to better revive the memory of the Sacred Union.

A GREAT RABBI PATRIOT

Born in Paris in 1859, Abraham Bloch is 55 when war is declared. Despite his advanced age, he plans to become a chaplain and is assigned to the 14th Army Corps.

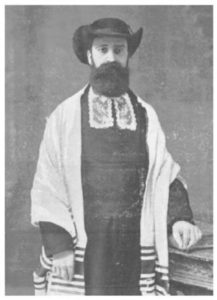

Chief Rabbi Abraham Bloch (image from Judaica Algeria)

Coming from a pious Alsatian family, he has a strictly rabbinic background. After studying at the Jewish seminary in Paris, he was sent to Remiremont (1884-1897) where he demonstrated a particular zeal that earned him the esteem of the faithful. He then became chief rabbi of Algiers from 1897 to 1908. The anti-Semitic maneuvers generated by the Dreyfus affair forced him to look after community interests and to support the republican cause. The chief rabbi of France, satisfied with his action, decided to promote him by offering him the responsibility of the chief rabbinate of Lyon and his region, a position he held from 1908 until mobilization. (2)

Rabbi Israel Levi, in an article he devotes to him in January 1915, testifies to his patriotic ardor while Abraham Bloch is of fragile health: “When the mobilization was decreed, the military authority asked the Chief Rabbi of Lyon to appoint the chaplain to follow the 14th Army Corps. Deaf to the objurgations of his friends and relatives, Abraham Bloch did not hesitate to claim for himself the honor of serving his country.” (3)

The latter adapts quickly to the new situation. If he notes with irony and pleasure in his notebook that he is the “Jewish priest”, because his outfit hardly distinguishes him from other chaplains, he welcomes the Sacred Union: “… I am the dean of the band. The officers are charming with us all.” (4)

If, for the moment, the chief rabbi has few Jews to comfort, he takes the opportunity to visit fellow Jews in the Vosges region where he had already established lasting relations during his first pastorate.

But the German offensive interrupts friendly visits. After Fraize and Provenchères, on the 25th of August the battalions are in front of Saint-Dié. Two days later, the chief rabbi notes for the last time in his notebook: “We are waiting for the order of departure to look for wounded. Meanwhile, it is said that it was on the side of Saint-Dié that one would have bombed…” (5)

Here ends the impressions of Abraham Bloch. From now on, the 14th Corps the journal of marches and operations tells us about the evolution of the fighting and the conditions of its death.

On August 28, the Chief Rabbi has neither the time nor the leisure to write, because the attack has resumed and is very violent. The troops, including the 58th Division, have been specifically ordered to “retake the offensive at all costs on Taintrux and Anozel.” (6) During the night of August 28 to 29, relief workers must evacuate more than 600 wounded and recover 150 soldiers on the battlefield. Despite the losses suffered, the French troops intend to remain masters of the place while the German artillery is unleashed. The Anozel pass becomes the stake of the fight, because the enemy wants to take this position which would then allow him to reach the small town of Saint-Dié.

The fighting is still raging. The daily newspaper mentions the tenacity of the troops: “During this day, which was very hard for our regiment, the personnel showed the greatest calm under the fire of the German howitzers. On August 29, around noon, stretcher bearers including Abraham Bloch were to transfer 450 wounded from Taintrux while they were still facing “enemy artillery fire.” Abbé Dubodel, Catholic chaplain and eyewitness, confirms the extreme violence of the fighting during this day: “Then the fire recommences, more violent than ever; the wounded lying pell-mell on the earth; stretcher bearers; ambulance cars. On arrival at the aid station, 5 or 6 missing, a wounded military chaplain, a Jewish rabbi wounded.” (7)

Can a rabbi be anything but Jewish? The expression of Father Dubodel, who knows the chief rabbi since the beginning of August, makes us smile. Be that as it may, it is certain that for several hours, between noon and six o’clock, the French troops suffered the repeated assaults of the German forces and are then obliged to retreat and “descend towards the Meuse in order to maintain it.”

It would be around 5 pm that the chief rabbi was killed in the conditions described by Major-General Raymond in the journal of the march of the stretcher-bearer group of the 68th Infantry Division:

“… It (the stretcher-bearer service) first evacuates the wounded of the 229th installed at the school of Anozel (about thirty), the closest to the line of fire, then those of the aid station of the 30th infantry located in the village barn. At this moment the bomging begins. A shell falls on the emergency station that the group is evacuating, without hurting anyone but starting to burn the barn.

This second post evacuated, the group took care of the third organized by the 229th and located in the last house of the village. At this moment, the bombing is in full swing, a shell falls on the first aid post, another on the neighboring house that it burns. (…) The shells continue to fall around the station and beat the road.

One of them kills a stretcher-bearer of the corps and violently throws the stretcher of the Dubodel group on the ground; this violent fall causes him a fracture at the base of the skull. Evacuated, quoted to the order of the army.

The rabbi (Mr. Bloch, rabbi in Lyon, section of the femoral, died in a few moments) of the stretcher bearers who carried a wounded man is also killed…” (8)

The battle is calm in the evening. At about 9:45 p.m., the chief of staff sent this note to the commander-in-chief: “Heavy fighting today on the entire front of the 14th Corps, great fatigue, large incalculable losses, again because of the extent of the front: 20 kilometers in the forests.” (9) The next day, there are more than 1,000 wounded. According to the military authorities, it is clearly admitted that Chief Rabbi Abraham Bloch was killed “by a shell that took away his left thigh and a bullet in his chest. In Taintrux, evacuating a wounded man.” (10) This is a trivial case on this Saturday, August 29, 1914.

“PARTIE À REMPLIR PAR LE CORPS” card for Rabbi Abraham Bloch

THE PRESS MAKES THE EVENT

As early as September 17, Les Archives israélites announce to its readers the disappearance of the Chief Rabbi, who became the first rabbinic victim in this context where one strives to celebrate with force the Sacred Union. In an article on page 2, the editor is content to mention the conditions of his death:

“The war has made a victim in the French rabbinate and it has chosen for its prey, one of its most worthy, most pious and most respected members: Chief Rabbi Abraham Bloch.

On the tragic circumstances in which the Chief Rabbi Bloch of Lyons died on the battlefield, we have the following information provided by Father Debodel de Chateauroux, who was wounded in the same place …

At about two o’clock in the afternoon, the corps of stretcher-bearers of the 58th Reserve Division, of which he was a member, cared for him on a farm of about 150 wounded. A German battery could not get the better of an alpine battalion, and directed its fires on the farm. The wounded are being evacuated. But the fire of the enemy is raging, waving pell-mell wounded, chaplains and stretcher-bearers. It is at this moment that Chief Rabbi Bloch falls to no longer get up, while Father Debodel gets away with an injury.”

This short article remains faithful to the declaration of the doctor-major and is based on the testimony of abbot Debodel (in reality Dubodel) published in Le Salut of Lyon of September 8, 1914. The abbot is in fact the only witness ocular who was close to the chief rabbi during the bombing.

The journalists do not yet mention the crucifix that the chief rabbi would have brought to a dying soldier. This act would have been the cause of his death. In May 1915, during the Ordinary General Assembly of the Consistory of Paris, President Edouard Masse evoked the death of Abraham Bloch, but without describing the circumstances of his disappearance. Like so many others, he would have been killed by the enemy as a stretcher-bearer: “… The heroic end of Chief Rabbi Abraham Bloch showed, from the beginning of hostilities, how our chaplains know, when he it is necessary to die for their country, demonstrating not only the most admirable courage, but also a breadth of ideas of which public opinion, without distinction of cults or parties, has so unanimously emphasized beauty.” (11)

Does “breadth of ideas” refer to the famous rabbi’s famous gesture? Perhaps! In this case, Edouard Masse is very skeptical and doubts the new version of the death of Abraham Bloch appeared in November 1914. It is the same for the other members of the assembly, which do not fall under the assertion of the President.

Yet, early in the fall of 1914, information will profoundly modify this event which is already becoming a symbol of the Sacred Union. According to a letter from Father Jamin, Catholic Chaplain of the 14th Corps, addressed to Father Chauvin, then pastor in Lyon, the Chief Rabbi died by shrapnel but after having found and brought a crucifix to a seriously wounded soldier. Seized by this detail which further illustrates the Sacred Union, Father Chauvin immediately communicated the information to the widow of Abraham Bloch on September 24, 1914:

“… Before leaving the hamlet, a wounded man, taking him for a Catholic priest, asked to kiss a crucifix. Mr. Bloch found the requested crucifix and had it kissed. After completing this act of charity, he left the hamlet accompanying another wounded man to the nearest car. The shell hit him a few meters ahead of the car where the wounded man had climbed.

I thought that these details would comfort a pain that must be very lively.” (12)

The grand rabbi’s family informs Rabbi Israel Levi, who has been his friend since their studies at the rabbinical seminary. A great patriot, Israel Levi believes that this example perfectly illustrates the dedication of the Israelites during the war. Quoting Father Jamin’s letter, he writes a note specifying the conditions of death in Les Archives israélites. He concludes, “… the rabbi’s act to get a crucifix to give to a wounded man to kiss – while the shells [that were] fired at the ambulance required a quick evacuation and died almost immediately afterwards, did it not deserve to be relieved?” (13)

Les Archives Israélites do not pay much attention to this story, which is narrated in the column “Jewish Echoes of the War” between the promotion of combatants and the patriotic actions of Baron Edmond de Rothschild. However, the description caught the attention of journalists in the non-Jewish press, including Gerard Bauer who devotes a major article on the issue entitled “The death of a rabbi” and published in L’Echo de Paris November 7, 1914. The author, by pointing out the sacrifice of a chief rabbi, glorifies the Sacred Union:

“… One evening when he was busy with this brave mission, he heard among the complaints the call of a dying soldier. The poor boy, hit in a way that did not forgive [mortally wounded], had slightly stood on one elbow and in a weak voice, asked him for a crucifix…

The rabbi had no hesitation. A hundred meters away, a priest was leaning over the dying. He joined him in haste, asked him to lend him his crucifix, came back to the wounded man and kneeling at his side, [the wounded man] approached the image of the Redeemer [with his] lips. And the soldier expired in that kiss.

But next to him another dying person, who had seen the Rabbi’s gesture, asked him to renew it for him. This time the Israelite did not hesitate either. He got up, but when he got up a bullet – we had not stopped fighting – a bullet hit him on the forehead. He sank down, falling dead by the side of the dying man he was going to succor, holding in his clenched hand the crucifix, which for the first time he had used.”

This article should receive our full attention because it is for the first time a fictionalized version of the death of Abraham Bloch. Where does Gerard Bauer hold his information, if not the note of Rabbi Israel Levi based on the letter of Father Chauvin? Moreover, he distorts the facts. The rabbi did this act only once and was killed by shrapnel, according to Father Jamin’s testimony. Several questions arise. Why is it not the Catholic priest who brings absolution to the dying soldier? Who is this chaplain who could have testified later on the action of the chief rabbi? Neither Pastor Rivet nor Father Jamin are with Abraham Bloch during the German offensive! Only Father Dubodel is not far from the chief rabbi, but he never mentioned the act.

For Gérard Bauer, one needs a heroic death in the image of the Sacred Union. Vulgar shrapnel is not dignified enough for such a gesture. Better a ball! Charitable action is not enough. We must renew the act.

This version makes its impression on the mentality of the time and even after. The rabbinate, if it doubts the gesture, does not question the information. After all, it serves the patriotism of Judaism. The community also needs heroes and martyrs and appropriates this story. On the occasion of the first anniversary of the death of Abraham Bloch, the chief rabbi of Lille, Édgard Sèches, salutes the sacrifice of his colleague: “… Martyr, he was, certainly. This word, you do not ignore, means WITNESS. Yes, he has witnessed our ardent love for France. Yes, he himself testified that this love can go to the complete sacrifice of life. (…) His death did more for Judaism and the French rabbinate than the most eloquent speeches. (14) Following the expression of Maurice Barrés, chief rabbi of France Alfred Lévy also pays tribute to Abraham Bloch, but does not mention the object: “… The name of this victim of duty will not perish; he will be the glory, the holy halo of his family, of the rabbinate, of French Judaism.” On this point, the rabbis are very discreet. Is it by religious conviction and disapproval of the gesture, or simply because they doubt the veracity of the act?

Preparing his study entitled The Diverse Spiritual Families of France, Maurice Barrés retains the fictionalized version in an article published in L’Echo de Paris on December 15, 1915 and included in his book. It is an opportunity for the nationalist man of letters to celebrate the virtues of the Sacred Union: “… From degree to degree, we have risen; here the fraternity spontaneously finds its perfect gesture: the old rabbi presenting to the soldier who dies the immortal sign of Christ on the cross is an image that will not perish.” (15)

From now on, from La Dépêche Algerienne to La Tribune de Genève, the national and international press has taken over this version, which has become almost official. This tragic, but symbolic end, also holds the attention of the political class and the poet Edmond Rostand who composes in March 1918 these few verses:

“A priest in a police cap

Wants to rush towards a dying person:

He falls. A rabbi replaces him,

The door to his Christian brother,

And on this dying person he attends

Falls and dies, wonderful deist,

For a God who is not his!” (16)

Inebriated by the Republican victory, Israelitism keeps in memory the death of Chief Rabbi Abraham Bloch, which has become a myth for the generation of veterans. No authority calls into question the gesture. The story is too beautiful and especially there has been too much ink and excited enthusiasm for the doubt [that] is now installed in the minds.

However, in 1921, Father Jamin returns to this episode in his book Advice to Young People of France, after the victory, in which he writes: “… I related in September 1914, in a private letter that was published the heroic death of Rabbi Bloch, military chaplain on the battlefield of Saulcy, near Saint-Die. I had not assisted myself, but I was telling the story of several eyewitnesses.” (17)

Father Jamin does not mention the witnesses whose information he keeps. Who are they? Father Dubodel, the closest person to the Chief Rabbi during the bombing, never confirmed the fact. The fighters present never appeared in the press and with the Bloch family. Is it Father Chauvin from Lyon who amplified the story? In this case, why is it not denied by Father Jamin? Did these two priests, intending to build an image of Epinal in the precious context of Sacred Union, no longer able to stop the anecdote that turned into a myth?

The death of Abraham Bloch immortalizes Sacred Union and Jewish participation during the conflict. The painter Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer reinforces the myth since 1917 with his canvas depicting the chief rabbi who brandished a crucifix on a dying wounded in the midst of the flames. In the twenties, the work is reproduced in the form of a postcard which is a work of pious image. At the same time, during the various patriotic celebrations, the rabbinate is careful to remind the public of the sacrifice of the chief rabbi.

The event, maintained by collective memory, resurfaced with more violence in the timid context of the thirties. The Patriotic Union of the French Jews tries to appropriate it to reproduce the Sacred Union so dear to veterans and that the news constantly denies.

A HISTORY THAT ARRANGES AND DERANGES

The death of Chief Rabbi Abraham Bloch is now history. Dead for the fatherland in the conditions we know, he becomes a martyr in the eyes of his contemporaries, anxious to defend the image of Judaism in a republican France. The disappearance of a private soldier in the same context may not have attracted the attention, but by the fact that it is a rabbi, known and respected by all, the anecdote then takes the extent.

The sacrifice of Abraham Bloch symbolizes the greatness of the Sacred Union and prides the collective memory since it meets all the necessary criteria, namely: the patriotic commitment with the voluntary service, the spiritual vocation with the chaplaincy, the fraternity with the help given to the dying soldier, tolerance with the crucifix.

If the chief rabbi becomes a martyr for the cause, the community does not make him a hero in the sense that we usually hear him, because he did not die fighting or resisting the enemy like the said young David Bloch.

The image of Epinal that holds the minds for several generations will however become suspect in the eyes of some historians. (18) The famous gesture causes doubt. Although they do not provide any proof for their claims, they consider the Chief Rabbi’s action to be implausible. Nevertheless, it is an opportunity for them to denigrate Judaism, for which they have only mistrust and to attack the role of the Patriotic Union of the French Jews in its appropriation of the event. But this story is only a brief episode for the Patriotic Union. Studying this case, Michel Abitbol concludes: “Like any good myth that respects itself, this story was never authenticated.” (19)

Also, the circumstances of this death challenge us. Since the debate is open and it will never be closed until the war logs (if they exist!) true witnesses will be untraceable, we will not know if the grand rabbi died [with] a crucifix in hand by rescuing a casualty.

Every war breeds myths. As proof, let us retain the story of the soldier Chauvin and that of the famous “trench of bayonets.” (20) French Judaism, like the Third Republic, needs myths to nourish its historical dimension. Already, on the eve of the Great War, Ernest Lavisse considered that teaching could not do without heroes and their legends. Memory succeeding history, it offers many possibilities as Pierre Nora recalls: “History is the always problematic and incomplete reconstruction of what is no more. Memory is an ever-present phenomenon, a bond lived in the eternal present; history a representation of the past. Because it is emotional and magical, memory only accommodates the details that comfort it; it feeds on vague memories, telescoping, global or floating, particular or symbolic, sensitive to all transfers, screens, censorship or projections.” (21)

After the war, Jean Norton-Cru is one of the first to doubt the authenticity of some testimonies relating to the Great War. His critical study of the phrase “The standing dead!” launched by Jacques Pericard must question us. According to Jean Norton-Cru, testimony is never perfect: “Each witness instinctively completes, and according to his own nature, the series of quick sentences, many of which have escaped him. He fills the blanks instantly and now forgets that they were blanks; voids. What he thought he saw, he sincerely believes he has seen. It is therefore almost impossible that on about thirty statements there are two that agree, even approximately.” (22)

The Great War, in the enthusiasm it provokes and through the French victory, gives birth to myths, situations that allow the imagination to reveal the greatness of the sacrifice made during the four years. Verdun, the heroism of fighters, bayonet charges are all examples that amplify a reality surely less ideal. The trauma of violence and suffering tends to accentuate the distortion of history in favor of memory.

We can understand that a simple anecdote can become a myth, especially when mystifiers seize it. In the present case, it is certain that Maurice Barrés, using Gérard Bauer’s article and Father Jamin’s letter, facilitated the diffusion of this myth.

It was from the summer of 1934 that the affair of Abraham Bloch resurfaced in the community when the Patriotic Union of French Jews led by Mr. Edmond Bloch uses the gesture of the Chief Rabbi to celebrate the fraternity of the trenches and, above all, to fight against anti-Semitism. Contrary to what Maurice Rajsfus thinks, the Patriotic Union did not invent the myth of Abraham Bloch. It has used it for its own sake, to revive unity among veterans as intolerance develops and the memory of Sacred Union is erased from the minds as the nation suffers social and economic crises. Admittedly, it is a political maneuver on the part of Edmond Bloch, who seizes the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of the death of the chief rabbi to demonstrate the action of his movement. But the members of the Patriotic Union as their co-religionists are convinced of the authenticity of the gesture. This symbol, while paying tribute to the rabbi, must popularize this association which has just been founded. Faced with the rise of the leagues and the involvement of many Jews in the progressive parties, Edmond Bloch and his friends consider it necessary to regroup patriotic Jews, viscerally attached to the maintenance of the republican order.

In this context, it is necessary to understand the role of the Patriotic Union when its president decides [upon] the erection of a stele in memory of the chief rabbi near the Anozel pass in September 1934, the place where Abraham Bloch fell. If there is not a political aspect here, this monument is part of the will to make a pious homage to a personality and to keep alive the collective memory.

With the implicit support of the central and Paris presidencies, in the presence of numerous rabbinical authorities, including the chief rabbi of Nancy Paul Haguenauer, and politicians, such as Mathieu Prefect of the Vosges and Georges Rivollet Minister of Pensions, Edmond Bloch delivers a strong speech noticed that testifies to this patriotic mentality while bringing a new version of Abraham Bloch’s gesture:

“… He leaned over to a wounded man, who took him for a Catholic priest and asked him for absolution. – “I’m not a Catholic, my poor friend, I’m a rabbi.” – “Can you not at least get me a crucifix?”

A Catholic stretcher priest was passing nearby, carrying, with one of his comrades, a wounded man on a stretcher. The chief rabbi asked him if he possessed a crucifix: the priest had one, but on his chest, inside his cloak; without giving up his stretcher, he indicated it to Abraham Bloch who opened the garment, took the crucifix and brought it to the wounded…” (23)

Where and how was Edmond Bloch able to gather this new information? According to Rene Lisbon, a member of the Patriotic Union and friend of the lawyer, Father Jamin himself would have described the scene. (24) In this case, why is the priest who has become a witness not invited to the demonstration to make his own declaration? His testimony would certainly have had more impact on the public.

Also, [for] everyone – a lack of concrete and direct evidence – can give free rein to his imagination provided that it fits in the direction of the Sacred Union. The adherents of the Patriotic Union are sensitive to this idea, as their spokesperson always says: “… More than the other French, we owe it to our country. The natural, sentimental, affective bonds which unite all Frenchmen to the common mother are common to all. We add one more: gratitude.”

This event draws the attention of the community press, which sees in Edmond Bloch’s action only a veteran’s action which is part of the continuity of the Sacred Union.

Late 1937, the death of the chief rabbi is again reminded to the community. The consistory of Lyon proposes to erect a monument to the memory of its chief rabbi on a large square in the city. (25) Edouard Herriot, the radical mayor, is in favor of the project. In a letter of January 31, 1938, he informed the Chief Rabbi Bernard Schoenberg that the city council grants Antonin-Gourju Place for the construction of the monument.

From the beginning, the project raises reactions. The chief rabbi of Lyon, supported by his colleagues from the Central Consistory, including Israel Levi, oppose the erection of a statue representing the chief rabbi bringing a crucifix to the wounded. The religious objection is valid. The Chief Rabbi of France recalls the hostility of Judaism to any image carved according to the commandment “You shall not make a carved image, nor any figure of what is in the sky above or on the earth below or in the waters below the earth.“ (Exodus, 20). It should be noted that no community has made a work of this type in synagogue courts or Jewish cemeteries.

But the hostility is even stronger on the side of the local population. If the Israelites, as a whole, are in favor of the project because they see the recognition of the city, the anti-Semites refuse the construction of such a monument, as reported in a confidential note from Lucien Coquenheim, chairman of the committee of Lyon:

“… But this (religious) objection, which may not have been absolutely insurmountable, is today largely overtaken by the anti-Semitic objection, which has broken the non-Jewish unanimity, without which the initial project loses, singularly, of its meaning and scope. Since then, it is no longer a work of social peace that will continue the erection of the monument, but will cause a fight, during which a Chief Rabbi will be unjustly slandered, thus reaching all French Judaism.” (26)

In 1938, the city of the radical Herriot knows many antisemitic disturbances caused by members of the Action Française and local leagues. It is easy to speak of anti-Semitic coalition against the project, because the nationalists are organized and put pressure on the municipal council to abandon the idea of a monument dedicated to a Jew, moreover a great rabbi.

According to a confidential report from the Lyon committee, mention is made of threats to members of the community and doubts on the part of the population about the sacrifice of Abraham Bloch. Lucien Coquenheim is obliged to conduct an investigation into the actions of anti-Semites:

“The investigation pursued by the members of the Lyon committee, among survivors, in recent months, has allowed them to discover that emissaries have been sent to these witnesses to make sure of the meaning in which they will testify. So, the campaign is ready, it is waiting for a pretext to be triggered; the official announcement of the erection.

The thought of the Lyon committee is dominated by two principles:

– Do not provide our opponents the “pretext” that will trigger the campaign before being ready for the fight;

– Do not seem to give in to antisemitic blackmail.” (27)

L’Action Française, through its hawkers, is struggling to cancel the project. A real campaign is organized to which the Lyons committee does not intend to answer. Leaflets are distributed; posters pasted. The Lyon public remains suspicious. In this context, Albert Manuel suggests to Lucien Coquenheim to conduct a more thorough investigation into the conditions of the death of the Chief Rabbi. The Consistory of Paris finances the proceedings of the Lyon committee, responsible for finding and interviewing witnesses. From February to July 1938, the survivors of this time are contacted. Lucien Coquenheim meets the abbots Jamin, Guyetant and Rouchouze, the pastor Rivet, the doctor-major Raymond and the teacher of Taintrux, Mrs. Richard.

The testimonies bring nothing concrete. On the contrary! Doubt persists about the act of the chief rabbi. No one is able to confirm whether the chief rabbi brought a crucifix to the soldier and died after this act.

Father Jamin and Pastor Rivet are content to explain their absence at this time. Confirming his letter of September 1914, Father Jamin asserts, however, that he keeps the information of a soldier who told him this story. But he is unable to mention the name of the witness in question.

Father Guyetant, not mentioned in the testimonies since 1914, but a former stretcher-bearer, confirms the fact that the rabbi had fallen to about twenty meters from him, but he does not mention his gesture. Worse, according to him, chief rabbi Abraham Bloch would have received absolution: “… Monsieur l’Abbe saw the rabbi fall 15 or 20 meters away from him. As he wore a cassock, Catholic priest stretcher-bearers mistook him for a Catholic chaplain gave him absolution.” (28)

Monsignor Rouchouze does not appear as an eyewitness either and considers that the medical officer is perhaps the only person to know the truth. But the latter’s statement addressed to Albert Manuel on April 14, 1938, confirms his statement mentioned in the march journal of the stretcher corps:

“… towards the end of the morning, we finished the evacuation of an emergency station located in Anozel, when this post was bombarded. There were only a few wounded left on stretchers and a number of stretcher-bearers insufficient to carry them. The chaplains then spontaneously joined the stretcher bearers to carry the last stretchers.

It was thus while carrying a wounded man that one of the chaplains whom I later learned, Rabbi Bloch was killed by shrapnel, at some distance from the village of Anozel.” (29)

Twenty years later, the memory of the doctor-major is intact, except that the chief rabbi died in the late afternoon.

Since, according to one version, Abraham Bloch was searching for the crucifix, he could have reached a house in the hope of finding one. Lucien Coquenheim contacted the village teacher, present at the time of the bombing and withdrawal of French troops. In a letter addressed to the grand rabbi’s daughter in June 1938, she is also unable to mention the circumstances of Abraham Bloch’s death: “… The Catholic chaplains and others immediately gave him all the responsibility. I was told that your father asked a Catholic confrere for a crucifix-so I do not know if he really went to get one from a house’ that’s a very accurate memory…” (30)

In full retreat and under a shower of shells, the urgency is above all the evacuation of the wounded. Can we imagine Abraham Bloch abandoning his duties as a stretcher bearer to fetch a crucifix when the battle is raging? Especially since the nearest house, where may be a crucifix, is more than 350 meters away. Could not the grand rabbi have the presence of mind to ask a soldier for a crucifix?

As for Father Dubodel, it is impossible to collect his testimony.

In the fall of 1938, for lack of sufficient evidence, the Lyon committee definitively abandoned the project. The chief rabbinate prefers this solution, considering that it is not useful to accentuate the discord between the French. With bitterness, Lucien Coquenheim writes: “… the presence of the chief Rabbi delegates, leaders of French Judaism seems to us indispensable. Because their absence, because of the protest raised by our opponents, would be interpreted in Lyon as a disavowal of the ceremony or gesture or both.” (31)

Even the chief rabbi of France, namely Israel Levi, no longer intervenes in the debate. Yet he was the friend of Abraham Bloch and the first to unveil Father Chauvin’s letter in the community press. Did he also doubt the famous gesture, while in full union sacred, he was convinced?

Doubt remains. Have there been mystifiers? For what purpose and for what profit?

Perhaps Father Jamin embellished the story, both out of sympathy for the chief rabbi and for the sake of magnifying the Sacred Union. The open-mindedness of Abraham Bloch and his cheerful and always voluntary attitude strongly impressed the coprs of the stretcher bearers. With the five priests, he showed another image of the Jew, thus breaking many prejudices. Here is a patriotic rabbi, devoted to the cause, and brave!

Father Dubodel never denied or confirmed the authenticity of the act. No doubt he did not wish to denigrate this alluring image which had already invaded the memory and which symbolized so well the Sacred Union … It is the same for the chief rabbi Israel Levi who, heir to the science of Judaism and professor at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes, preferred to maintain this myth rather than reduce it to a simple anecdote.

A symbol of the Sacred Union and glorification of Jewish patriotism, even after the Second World War, the image of the gesture of the Chief Rabbi is still present in the minds. The chief rabbi of France Jacob Kaplan, himself a veteran of the Great War, retains from this example the persistence of concord, fundamental to all nations:

“… It will not perish at last because it will always speak to the French soul which unites in a harmonious agreement the most diverse tendencies, in the manner of this splendid Vosges landscape … yes, it will always speak to the the soul of France so comprehensive and so liberal because France can not, not be in love with grandeur and heroism, humanity and generosity.

The gesture of Taintrux, an example of union on the battlefield is also a symbol of understanding during peace.” (32)

Raised to the level of national and community myth, the story of the death of Chief Rabbi Abraham Bloch is still not closed. The debate thus remains open…

(1) Maurice Barres, The Diverse Spiritual Families of France, Emile-Paul, 1917, p. 93.

(2) ACIP, Abraham Bloch file. SIF, Abraham Bloch fonds.

(3) L’Univers israélite, January 1, 1915.

(4) SIF, Abraham Bloch fonds, notebook, August 8, 1914.

(5) Ibid., August 27, 1914.

(6) SHAT, file 26 N.145. Journals of 14th Corps.

(7) Ibid.

(8) SHAT, file 26 N.154. Medical Service Journal, August 29, 1914.

(9) SHAT, file 22 N.1033. Operations of the stretcher-bearer group, August 29, 1914.

(10) SHAT, file 26 N.154.

(11) ACIP, PV series. General meeting of May 30, 1915.

(12) SIF, Abraham Bloch fonds. Letter from Father Jamin to Mrs. Bloch, September 24, 1914.

(13) Les Archives israélites, November 5, 1914.

(14) L’Univers israélite, October 8, 1915.

(15) Maurice Barrés, op. cit., p. 93.

(16) The Revue des Deux Mondes, March 1, 1916, p. 66.

(17) Fernand Jamin, Advice to Young People After the Victory, Perrin, 1921, p. 89.

(18) See David H. Weinberg, The Jews in Paris from 1933 to 1939, Calmann-Lévy, 1974, p. 107, Maurice Rajsfus, Be Jewish and Shut Up!, E.D.I, 1981, pp. 214-215, and Michel Abitbol, The Two Promised Lands – The Jews of France and Zionism, Olivier Orban, 1989, p. 281.

(19) Michel Abitbol, op. cit., p. 281.

(20) G. de Puymege, “The Soldier Chauvin” (pp. 45-80), and Antoine Prost, “The Trench of Bayonets” (pp. 111-141), Places of memory. The Nation, t. 2, under the direction of Pierre Nora, Gallimard, 1986.

(21) Pierre Nora, “Between memory and history”, Les Lieux de mémoire, t. 1, p. XIX.

(22) Jean Norton-Cru, From the Testimony, Éditions Allia, 1989, p. 25.

(23) L’Univers israélite, September 7, 1934.

(24) Ibid.

(25) ACIP, carton B.134. Year 1938, project of erection of a monument for Abraham Bloch.

(26) Ibid.

(27) Ibid.

(28) Ibid.

(29) ACIP, carton B.134. Year 1938, received letters.

(30) SIF, Abraham Bloch fonds. Letter from Mrs. Richard to Mrs. Netter (daughter of Chief Rabbi Abraham Bloch) of June 17, 1938.

(31) ACIP, carton B.134.

(32) Journal of Communities, No. 202, September 1958.

Abbreviations

ACIP: Association consistoriale israélite de Paris

SHAT: Service historique de l’armée de terre (SHAT Vincennes)

SIF: Séminiare israélite de France (Paris)

References

Landau, Philippe-E., Les Juifs de France et la Grande Guerre – Un patriotisme républicain, CNRS Editions, Paris, France, 1999

Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française (1914-1918) (Israelites [Jews] in the French Army), Angers, 1921 – Avant-Propos de la Deuxième Épreuve [Forward to the Second Edition], Albert Manuel, Paris, Juillet, 1921 – (Réédité par le Cercle de Généalogie juive [Reissued by the Circle for Jewish Genealogy], Paris, 2000)

Page listing Rabbi Abraham Bloch’s name in Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française (the notations and “doodles” (!) are my own)

Page listing Rabbi Abraham Bloch’s name in Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française (the notations and “doodles” (!) are my own)

Postcard of Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer’s painting of Rabbi Abraham Bloch holding a crucifix before a dying soldier (“Künstler-AK Le Grand Rabbin Aumonier Abraham Bloch, Rabbi als Feldgeistlicher”), at oldthing.de

Photograph of Rabbi Abraham Bloch, at Judaica Algeria