[I recently re-posted information about Jewish military casualties on July 12, 1945, based on a news item about Captain Edmond Joseph Arbib – killed in a flying accident on that date – which was published in The New York Times on July 18, 1945.

Akin to that updated post is this similarly updated post, pertaining to Jewish military casualties on January 11, 1945. When originally created, on May 11, 2017, this post was limited to information about two members of the United States Army Air Force (Cpl. Philip Arkuss and Lt. Edward Heiss), based on a news item about Corporal Philip Arkuss – in particular – which appeared in the Times on March 8, 1945. Paralleling my recent post about Captain Arbib, “this” revised post is of a much larger scope, and presents information about some other Jewish military casualties on the day in question: January 11, 1945.]

______________________________

Corporal Philip Arkuss

Thursday, January 11, 1945 – 27 Tevet 5705

Tehé Nafshó Tzrurá Bitzrór Haḥayím

May his soul be bound up in the bond of everlasting life.

Corporal Philip Arkuss (32802439) served in the 100th Bomb Squadron of the 42nd Bomb Group, a B-25 Mitchell equipped combat group of the 13th Air Force, then stationed at Sansapor, New Guinea. His name appeared in a Casualty List published in the Times on March 8, 1945, and his photograph and obituary were published in that newspaper twelve days later, on March 20.

Cpl. Arkuss’ aircraft, B-25J 43-27979, piloted by 2 Lt. John W. Magnum, was shot down by anti-aircraft fire during a low-level bombing and strafing mission to Kendari, Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. (Formerly the Netherlands East Indies.) The plane was at too low an altitude for the crew to escape by parachute, though their chance of survival if captured would have been miniscule, at best.

Mangum, John Wesley, 2 Lt. – Pilot (0-751383) – Dallas, Tx.

Acker, Clarence Ward “Buck”, 2 Lt. – Co-Pilot (0-765211) – Dallas, Tx.

Quinn, Thomas F., 1 Lt. – Navigator (0-569858) – Chicago, Il.

Snyder, Carl V.E., Sgt. – Flight Engineer (35867076) – Franklin County, Oh.

Hough, Wallace E., Cpl. – Gunner (12199927) – St. Lawrence County, N.Y.

“The strafers RON’d [rendezvoused] at Morotai, and repeated the performance the following day. Capt. J.W. Thomason was the leader of the 69th; Capt. R.J. Weston, the 70th; Lieut. John M. Erdman, the 75th; Lieut. Tom J. Brown, the 100th; and Capt. Gordon M. Dana, the 390th. It was another knockout punch; 300-pound demos exploded inside at least two buildings, sending debris up to the level of the planes, and tracers went everywhere, wiping out AA gun crews and personnel who had run to cover. But still the AA did its damage. Lieut. J.R. Sathern was hit and had to crash-land wheels-up at Morotai. All the crew walked away. Hit in the right engine just after releasing, Lieut. John W. Mangum of the 100th crashed into a 6000 foot ridge west of the target, with no possibility of escape for the crew.”

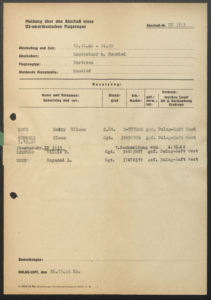

The MACR (Missing Air Crew Report) covering the loss of this plane and crew is presented below. The number of this MACR – 15661 – indicates that the document is a “fill-in” MACR, filed after the war ended.

Course: Off Marr on Cannal through Dampier Strait to Cape Waka at the southern tip of Sanana Island to Mono_i Island to the initial point of Sampara River mouth, then direct to the target on a true heading of 210 degrees. Retirement right divert to Morotai. From Morotai direct to home base.

It is believed that Aircraft B-25, 43-27979 was hit in the right engine just after dropping its bombs in the target area. The plane was observed to slowly settle while on fire. It crashed and exploded on a ridge 6,000 feet west of the target area P-1 at Kendari. The bomb doors were still open when the plane exploded. There was no chance for any of the crew to escape alive. (Ref. Mission Report #245).

According to American Jews in World War Two, Philip received the Purple Heart, but, no other military awards are listed for him. If this is correct, it would suggest that he had flown less than five combat missions at the time of his death.

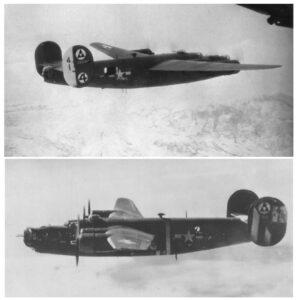

This photo from The Crusaders provides a representative view of a 42nd Bomb Group B-25J “solid nose” Mitchell bomber in natural metal (that is, uncamouflaged aluminum), unlike most of the Group’s bombers, which were finished in olive drab and neutral gray. This example sports the 42nd Bomb Group’s simple markings comprised of the Group’s insignia of a Crusader shield painted on the center of the fin and rudder, and the top of the vertical tails trimmed in yellow. Interestingly, the plane’s serial number (44-30285) appears twice: Upper in the original factory-painted location, and lower in repainted stylized numbers. Crusader B-25s carried no plane-in-squadron identification numbers or letters.

B-25J 44-30285 survived the war.

Here’s the emblem of the 13th Air Force…

…while this excellent image of the 42nd Bomb Group’s insignia with repainted serial number, characteristic of late-war Crusader Mitchells, is from World War Photos. This B-25J (44-29775) also survived WW II.

This image of the insignia of the 100th Bomb Squadron – crossed lion paws on a blue field – is from Maurer and Maurer’s Combat Squadrons of the Air Force – World War Two. Images or scans of the original insignia do not (as of 2022) appear on the Internet.

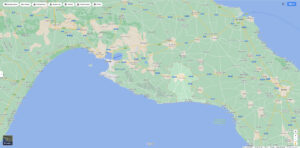

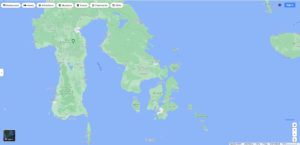

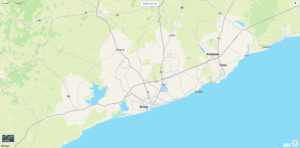

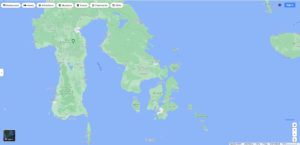

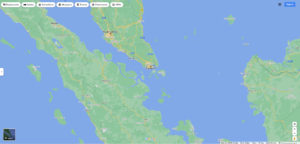

This small-scale Oogle map shows the general location of the city of Kendari, in Southeast Sulawesi, in the Celebes Islands. The city lies in the very center of this image.

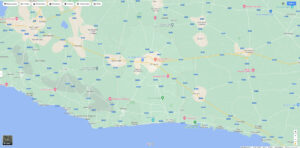

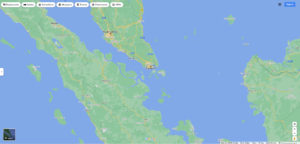

Oogling in for a closer look, this map shows the location of the 42nd Bomb Group’s destination and target for the January 11 mission: Kendari Airfield (or Kendari II), now known as the Bandara Haluoleo airport, southwest of Kendari. The red oval designates the general location of the crash site of 43-27979, based on latitude and longitude coordinates in MACR 15661.

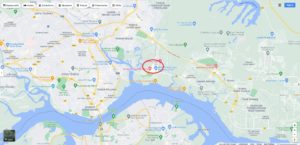

Oogling yet closer… The Mangum crew’s Mitchell crashed into a ridge west of Kendari II, not actually at the airfield itself.

This Oogle air photo – at the same scale as the above map – shows the plane’s probable crash location, again indicated by a red oval. The precise location of the crash would presumably be available in IDPFs (Individual Deceased Personnel Files) for any and all of the plane’s six crewmen.

The plane’s entire crew was buried in a collective grave in Section E (plot 145-146) of Zachary Taylor National Cemetery, in Louisville, Kentucky on August 16, 1949. An image of the crew’s collective grave marker, taken by FindAGrave contributors John and Kim Galloway, is shown below:

Here is Cpl. Arkuss’ obituary, as it appeared in the Times on March 20:

Former New Opera Player Dies on Celebes Mission

On Christmas Day Corp. Philip Arkuss of 170 Claremont Ave. entertained several thousand servicemen at his base by playing a violin he had purchased from a “buddy” after he went overseas. Before entering the service he had been with the New Opera Company and with “Porgy and Bess,” and had won a Philharmonic scholarship. He was 23 years old.

His widow, Olga Bayrack Arkuss, has received a War Department telegram reporting that he was killed on Jan. 11 in action over the Celebes Islands. He was a radio operator – gunner in a B-25 bomber that was shot down by Japanese anti-aircraft while flying low and crashed into a mountainside.

He had entered the service in February, 1943, training in Florida, South Dakota and South Carolina and went overseas in October of last year. Before entering the service he had been concert master of a United Service Organization’s Symphony Orchestra that toured the country.

Besides his widow he is survived by his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Arkuss, and a brother, Albert.

This 2017 Oogle Street view shows the location of the Arkuss family’s WW II home: 170 Claremont Ave., in the Morningside Heights section of Manhattan…

…while this street scene of 170 Claremont Ave. is from streeteasy.com.

__________

Other Jewish casualties in the 100th Bomb Squadron include Sergeant James Edward Levin (14065044; Flight Engineer; MACR 15979; B-25J 43-36015), from Charleston, S.C., whose crew was lost on April 8, 1945; Second Lieutenant Joseph B. Rosenberg (0-685730; Navigator; MACR 13501; B-25J 43-27976), from New York, N.Y., whose aircraft was lost on March 10, 1945; and Flight Officer Ralph E. Roth (T-128789; Navigator; B-25J; MACR 14132; 43-27848) from South Bend, In., whose Mitchell crashed on April 14, 1945.

______________________________

Some other Jewish military casualties on January 11, 1945 (27 Tevet 5705) were…

Tehé Nafshó Tzrurá Bitzrór Haḥayím

May his soul be bound up in the bond of everlasting life.

On the 11th of January, 1945, two bombers were lost from the twenty-five Calcutta based 58th Bomb Wing B-29 Superfortresses that struck dry-dock facilities at Singapore.

One of these aircraft was B-29 42-24704, piloted by Lt. Col. Donald J. Humphrey. There were eight survivors from the eleven crew members in this 793rd Bomb Squadron, 468th Bomb Group plane, the loss of which is covered in Missing Air Crew Report 10879, and at Pacific Wrecks. Of the eight, four survived as POWs.

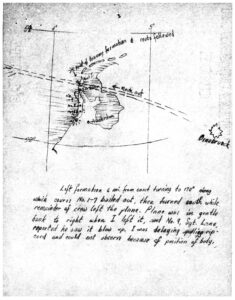

In total, the crew of the other B-29, 42-65226 (the loss of which is covered in MACR 10878), plane-in-squadron number 54, did not fare so well: Of the eleven men in this plane, only three would survive the war. While two minutes from the target and on its bomb-run, the aircraft, piloted by Major Joseph H. Wilson, Jr., was either directly struck by anti-aircraft fire, or (as later speculated by Major Wilson himself) an aerial bomb, and exploded.

As described in Missing Air Crew Report…

About 5 miles NE of primary target, time 0203Z, 4 objects believed to be chutes were seen in air close together, at 14,000’. No B-29 was seen in immediate vicinity.

While on Bomb Run, about 20-25 miles N of primary target, pilot of a/c 580 saw an a/c explode directly over target. The explosion emitted large orange flame, then the a/c seemed to disintegrate. Observers could not be sure that this a/c was a B-29.

Contact with a/c 226 of this Squadron was last made in the vicinity of the IP. Up to this point, 3 other aircraft had voice radio contact with 226; during this time between Assembly Point and IP, 226 was talking with these a/c , all of them attempting to get together for formation bomb run. After leaving IP no one had any contact with 226, and subsequent efforts to call him from the local ground station were unsuccessful.

01 15 N – 103 53 E was approximate position of a/c 226 when last contacted by voice radio.

Plane 54’s crew comprised:

Wilson, Joseph H., Jr., Major – Aircraft Commander (0-413209) – Gainesville, Ga. – Survived (Evaded)

Fitzgerald, Russell G., 1 Lt. – Co-Pilot (0-808350) – West Medway, Ma. – Survived (Evaded)

Osterdahl, Carroll Nels, 1 Lt. – Navigator (0-739573) – Santa Barbara, Ca. – Captured; Murdered 2/10/45

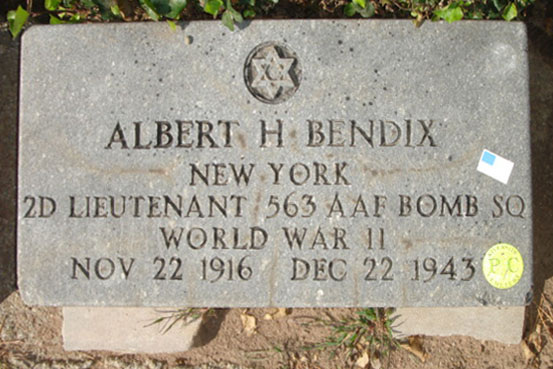

Heiss, Edward, 1 Lt. – Bombardier, 0-688085, Brooklyn, N.Y. – Captured; Murdered 2/10/45

Vail, Charles E., 1 Lt. – Flight Engineer (0-860970) – What Cheer, Iowa – KIA

Yowell, Robert William, 1 Lt. – Radar Operator (0-862033) – Peola Mills, Va. – Captured; Murdered 2/10/45

Roberts, Jerry D., S/Sgt. – Radio Operator (18226784) – Jacksonville, Tx. – Survived (Evaded)

Wolk, Philip, Sgt., 32805025 – Gunner (Central), Bronx, N.Y. – KIA

Gumbert, Boyd Morris, S/Sgt. – Gunner (Right Blister) (13131774) – New Kensington, Pa. – KIA

Ellis, Samuel Burton, Jr., S/Sgt. – Gunner (Left Blister) (34687577) – Pitts, Ga. – Captured; Murdered 2/10/45

Holt, Alarick Arnold, T/Sgt. – Gunner (Tail) (37160988) – Lindstrom, Mn. – KIA

_____

Here’s the emblem of he 20th Air Force…

…while this example of the emblem of the 677th Bomb Squadron is from Military Aviation Artifacts.

_____

As highlighted above, only three of the plane’s crew would eventually return: Besides Major Wilson, the other two survivors were co-pilot 1 Lt. Russell G. Fitzgerald and radio operator S/Sgt. Jerry D. Roberts.

Sgt. Wolk, Flight Engineer 1 Lt. Charles E. Vail, aerial gunner (right blister) S/Sgt. Boyd M. Gumbert, and, tail gunner T/Sgt. Alerick A. Holt presumably died in the explosion or crash of the aircraft.

Lt. Heiss, navigator 1 Lt. Carroll N. Osterdahl, radar operator 1 Lt. Robert W. Yowell, and aerial gunner (left) S/Sgt. Samuel B. Ellis, Jr. all survived the explosion and – like Wilson, Fitzgerald, and Roberts – parachuted to safety.

But… According to postwar statements by Major Wilson and Sgt. Roberts, Heiss and Yowell were captured by the Japanese while attempting to reach the headquarters of a local Chinese guerilla unit, possibly with the connivance of a certain Manuel Fernandez, a “plantation worker who may have been playing both ends of the game for his own personal enrichment”. Other (web) sources suggest that Lt. Osterdahl and Sgt. Ellis were also captured.

In any event, these four men were killed murdered by their captors (specifically, a “Sub-Lieut. Koayashi” and a “W/O Toyama” of the 10th Special Base Unit) on February 10, almost a month after they were shot down.

A copy of the Detail of the Trial Record of members of the 10th Special Base Unit is available via ocf.berkeley.edu. I’ve transcribed and edited the document, which you can access here.

_____

Akin to the loss of B-17G 44-6861, the loss of B-29 42-65226 marks an incident (well, there were a few) where a missing aircraft had earlier been photographically captured in an official Army Air Force photograph. This image, Army Air Force photo A-55427AC / A1014, taken a little less than two months before the loss of the Wilson / Fitzgerald crew, is captioned: “Boeing B-29 Superfortress of the 20th Bomber Command fly [sic] over the Himalaya Mountain range in an area now commonly referred to as “The Hump”. Photo was taken enroute to target at Omura, Japan, 11/21/44. In this photo cloud formations obscure the mountainous background. [penciled in…] “444th Bomb Group.“

_____

MACR 10878 includes postwar affidavit by Sgt. Roberts and an interview of Major Wilson.

Here’s Sergeant Wilson’s affidavit, taken on June 18, 1946 at Barksdale Field, Louisiana, while he was serving in Squadron A-1 of the 2621st Army Air Force Base Unit.

On January 11, 1945, we were scheduled for a mission to attack Singapore, Malaya. Upon going to briefing in the morning in question, our regular Engineer assigned our crew was attached to a rest camp, which caused a vacancy to exist on our crew. On this morning, First Lieutenant Charles E. Vail, 0-860971, was assigned to our crew as Aerial Engineer. My assigned position on the crew was radio operator, which placed me directly across from the engineer in the plane.

After briefing and take off about two minutes from the target, and while on the bomb run, there was an explosion, causing the ship to be blown to bits and six of us were blown out of the ship. This knowledge was gained from the other members of the crew, as I was rendered unconscious at the time of the explosion.

The first thing I can remember is that I came to in the air and my parachute was open. While descending, I noticed bits of the ship falling. To the best of my knowledge, the location was about two miles from the target outside of Singapore.

Upon reaching the ground, members of a guerilla band rescued me and on this same day at about sundown, I joined the bombardier, Lt. Heiss. Early the next morning about three o’clock, we joined two other members of our crew, the pilot, Major Wilson, and the radar man, 1st Lt. Yowell.

While enroute to guerilla headquarters, we approached a Japanese sentry post, at which time the leader of the guerilla band that we were with placed Major Wilson and myself under cover of bushes and surrounding trees, and made a statement that he was going to try to get Lt. Heiss and Lt. Yowell past the sentry post, since they were uninjured and we were classified as stretcher cases. He said if he could manage to get the two through without being caught, he would return for us. After a lapse of approximately four days, a member of the guerilla band returned, at which time he told us that Lt. Heiss and Lt. Yowell had been captured by the Japanese upon crossing the road. After a lapse of approximately two weeks, we received word that Lt. Heiss and Lt. Yowell had been executed, along with a third person whose identity is unknown to me, but it was believed by the guerilla band that he was captured immediately upon landing from bailing out of one of the airplanes in the formation. To the best of my knowledge, we were the only ship that had been hit at that particular time.

The guerilla leader made a statement while we were stationed with him that this third member who had been executed was taken down the main street of Singapore and that the Japs were flogging him and that the man who was being flogged kept crying out, “Good for me, bad for you,” buy which they determined that he was an American because of his language. According to the guerilla band’s information gathered from the Japs, they accounted for only four bodies in the plane, they captured three men, and the three of us made a total of ten men, which would leave another crew member still unaccounted for.

About five weeks after our accident, we joined the co-pilot of our crew, Lt. Fitzgerald, who had survived the crash and had joined natives. He had not seen any of the crew members until we joined him.

_____

Here’s a transcript of an interview of Major Wilson as recorded and transcribed by 1 Lt. H.P. Romanoff, the Assistant Post Intelligence Officer, Headquarters, at Army Air Force Overseas Replacement Depot and AAF Redistribution Station No. 5, Greensboro, North Carolina. The statement specifically concerns the fate of 1 Lt. Charles E. Vail, though Major Wilson’s statements are relevant to the fates of other crew members.

Wilson stated that he was the pilot of the B-29 and that Vail was not the regular flight engineer, this being his first assignment.

Wilson stated that take-off was from Duddkhundi, India, for target at the Salita Naval Base, Singapore, on 11 January 1945. While on the bomb run the aircraft was hit by either flak or an aerial bomb. The aircraft exploded. As a result of the explosion, a hole was blown in the plastic nose of the aircraft. While trying to regain control of the aircraft, Wilson saw several black objects going rapidly through the hole in the plastic nose. It seemed as if the objects were being thrown through as a result of the force of the explosion. Wilson’s safety belt was tight. This gave him an opportunity to look back just prior to being thrown himself. He noted that Vail’s seat was empty.

Prior to the above, Wilson last saw Vail just prior to the bomb run. On this occasion he had instructed Vail to check the fuel.

After being thrown from the aircraft, Wilson parachuted safely to the ground.

Upon receiving the ground, Wilson and four other members of his crew (1st Lt. Russell Fitzgerald, co-pilot; 1st Lt. Edward Heiss, bombardier; 1st Lt. Robert Yowell, radar operator, and S/Sgt. Jerry D. Roberts, radio operator) were gathered together that night by Chinese natives. The latter had information that another person had been captured by the Japanese and was quite badly beaten before being taken to Singapore. The identity of this person is unknown.

Later that night, 1st Lt. Heiss and 1st. Lt. Yowell were captured by the Japanese and taken to either Singapore or Johore, Bahru, India.

HEARSAY INFORMATION: Later on, while assisting Major Wilson in evasive tactics, Chinese guerillas and an Indian dresser (one who works as a first-aid man on a rubber plantation), Manuel Fernandez (employed at S__gai, Plantation Esate, Massai Johore) stated that two First Lieutenants and one other person were publicly tortured to death at either Singapore or Johore. Major Wilson feel that Vail could have been one of the three persons. Ity is believed that Fernandez may be able to confirm this because of his close proximity to the Japs. However, it is further believed by Major Wilson that while anti-Jap, Fernandez may have been playing both ends of the game for his own personal enrichment. It is quite possible that Fernandez has been interrogated by the British.

Major Wilson further stated that he heard four men of his crew were found dead at the scene of the B-29 crash and that three others, in addition to Fitzgerald and Roberts, had been captured.

Major Wilson also stated that a good source of information is a Chinese guerilla named Chen Tien, alias Chai Chek. This person is one of the guerilla leaders from Singapore who could speak English. Chen Tien is known to British Intelligence, having worked for them while in the jungle.

_____

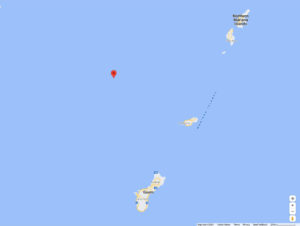

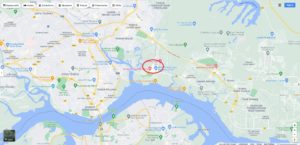

These three Oogle Maps show the general – presumed – location of the crash of B-29 42-65226. This first map shows the location of Singapore: Just off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula.

Oogling in for a closer look, the red oval shows the bomber’s probable crash location: Not in Singapore per se, but just beyond, between Plentong and Johor Bahru. This estimate is based on longitude and latitude coordinates in the Missing Air Crew Report, as well as statements by witnesses to the aircraft’s loss, and, accounts by the three survivors.

One more map, giving an even closer (!) view of the B-29’s likely crash location. If correct (I think correct…), the crash site is now an area of residential and commercial development. Including a shopping center.

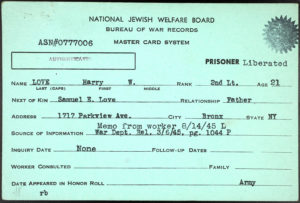

Life numerous American Jewish WW II servicemen, the name of Lieutenant Edward Heiss, the plane’s bombardier, is absent from the many-times-mentioned-at-this-blog book, American Jews in World War Two.

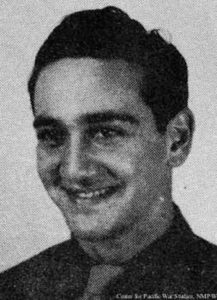

Born in New York in 1918, he was the son of Samuel (1887-10/3/60) and Pepi (Scherzer) (1/26/89-10/15/88) Heiss, and brother of Seymour and Sylvia, the family residing at 503 East 2nd St., in Brooklyn. The recipient of the Air Medal and Purple Heart, he flew 12 combat missions. A symbolic matzeva exists for him Mount Moriah Cemetery, in Fairview, New Jersey, and his name is Commemorated at the Tablets of the Missing in the Manila American Cemetery, Manila.

Several images of Lt. Heiss and his family members, as well as a photo of what I believe (?) to be his crew, can be found in the blogs posts “On Memorial Day, Remembrance of my Uncle Eddie is a blessing”, and “Memorial Day – In Honor of My Uncle Eddie,” created in his memory, at Divah World, from which these pictures have been taken.

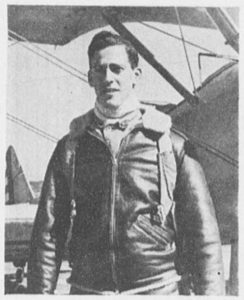

This portrait of Edward was probably taken during training…

…while this portrait was presumably taken upon his graduation from bombardier school.

_____

_____

_____

With his mother Pepi, and sister Sylvia?

_____

With his father Samuel and mother Pepi.

This image of Lt. Heiss’ symbolic / commemorative matzeva is by FindAGrave contributor dalya d. There’s a stone there. Someone visited. Perhaps they said kaddish?

_____

Here’s – I think – Lt. Heiss’ crew – with Lt. Heiss circled. Since the aircraft serving as a backdrop is a B-17 Flying Fortress, this photo would definitely have been taken while the crew was undergoing training in the United States. The men standing to the right and left of Lt. Heiss would presumably have been the pilot, co-pilot, navigator, and flight engineer, while the enlisted personnel kneel in front. Judging by appearances – see photo below – I think the officer to Lt. Heiss’ right is 1 Lt. Robert W. Yowell.

_____

1 Lt. Robert William Yowell of Peola Mills, Va., (0-862033) was the B-29’s Radar Operator. This image of Lt. Yowell, from the Library of Virginia, was contributed to his FindAGrave profile by DebH.

_____

This image, from the Olson Family Tree at Ancestry.com, shows the bomber’s navigator, 1 Lt. Carroll Nels Osterdahl, Navigator (0-739573), of Santa Barbara, Ca.

_____

Sergeant Philip Wolk, the B-29’s central fire control gunner, is mentioned in American Jews in World War Two, where his name appears on page 475. He’s listed as having received only the Purple Heart, which would suggest that’d he completed less than five combat missions prior to his death on January 11.

Sergeant Wolk was married: His wife was Bette, whose address was listed as 2810 Wallace Avenue, in the Bronx; his mother was Bertha, who by 1940 married Jacob Kleinman, and his siblings Alice and Bernard. He was buried at Mount Zion Cemetery, Maspeth, N.Y. (Path 30 Right, Gate 2, Grave 1, Kadish Brooklyn Society) on June 21, 1950.

_____

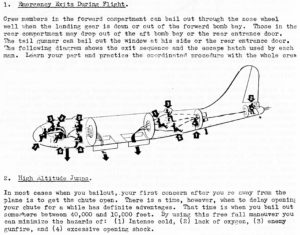

From Boeing’s B-29 Maintenance and Familiarization Manuel (HS1006A-HS1006D), this cutaway shows the interior details of a B-29’s aft pressurized compartment. The forward section of the compartment (to the left) has stations for the aircraft’s port and starboard gunners, and, an upper station with an elevated seat for the bomber’s central fire control gunner, who had the ability to selectively control any one (or any number, in combination) of the bomber’s gun turrets. Each of the three aerial gunner’s positions features a hemispherical plexiglass sighting / observation dome, with its own gunsight. The rear section of this compartment (to the right) contains the rear upper gun turret, and, a toilet and rest bunks, the latter two accommodations rather necessary (!) due to the duration of missions capable of being flown by B-29s.

__________

As the B-29’s central fire control gunner, Sgt. Wolk would have occupied the elevated seat in this compartment. This image, coincidentally from The Pictorial History of the 444th Bombardment Group, Very Heavy Special, shows a “CFC” gunner in his crew position, photographed from the vantage point of one of the two side gunner positions. As determined postwar, Sgt. Wolk never escaped the falling B-29.

United States Army (Ground Forces)

Killed in Action, Died of Wounds, or, Died While Prisoners of War

Axelrod, Seymour M., PFC, 42076821, Purple Heart, 1 Oak Leaf Cluster

78th Infantry Division, 309th Infantry Regiment, A Company

Mrs. Rose Axelrod (mother), 703 E. 5th St., New York, N.Y.

Born 1926

Place of burial unknown

American Jews in World War II – 268

____________________

Barr, Sidney Fred (Shlomo “Yidel” bar Yehiel), PFC, 33735600, Purple Heart

70th Infantry Division, 276th Infantry Regiment, L Company

Mr. Isaac Barr (father), 4950 Albany Ave., Chicago, Il.

Born Chicago, Il., 1925

Waldheim Jewish Cemetery, Forest Park, Chicago, Il. – Gate 203 (Proskover Society)

American Jews in World War II – 93

These two images of PFC Barr’s matzeva are by FindAGrave contributor Jim Craig.

____________________

____________________

Bellman, Alexander, PFC, 32312426, Purple Heart

63rd Infantry Division, 254th Infantry Regiment, K Company

Mr. Benny Bellman (father), 1725 Fulton Ave., Bronx, N.Y.

Born 8/8/18

Long Island National Cemetery, Farmingdale, N.Y. – Section H, Grave 9787

Casualty Lists 2/24/45, 3/24/45

American Jews in World War II – 272

____________________

Einhorn, Stanton Lewis Arthur (Shmuel Yehudah Asher bar Dov HaLevi), PFC, 33772037, Purple Heart

90th Infantry Division, 357th Infantry Regiment, Company E or G

Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin (9/11/86-6/20/74) and Minnie (Haber) (12/19/94-3/20/91) Einhorn (parents)

Edgar, Harold, and Cpl. Marvin D. Einhorn (brothers)

6642 Lincoln Drive, Philadelphia, Pa.

Born Philadelphia, Pa., 12/4/25

Roosevelt Memorial Park, Trevose, Pa. – Lot D3, Plot 31A, Grave 3; Buried 8/15/48

Casualty List 12/4/25

Jewish Exponent 3/16/45, 8/20/48

Philadelphia Inquirer 3/8/45, 8/14/48

Philadelphia Record 3/8/45

American Jews in World War II – 518

____________________

Fink, Harold, Sgt., 18073450, Purple Heart, in France

70th Infantry Division, 275th Infantry Regiment, G Company

Mr. and Mrs. Hyman (4/3/93-11/3/37) and Minnie (Levine) (5/18/97-8/15/91) Fink (parents), 2202 East Alabama St., Houston, Tx.

Ethel Cecile, Hortense, and Jack Joel (sisters and brother)

Born Brenham, Tx., 1923

Epinal American Cemetery, Epinal, France – Plot B, Row 39, Grave 24

American Jews in World War II – 571

This portrait of Sgt. Fink, from the Class of 1940 San Jacinto High School yearbook, is via FindAGrave contributor Patrick Lee.

____________________

____________________

Goldsmith, Jack, S/Sgt., 32432720, Purple Heart, at Darnatel, France

Mr. and Mrs. William and Lena Goldsmith (parents), 710 Fairmount Place, Bronx, N.Y.

Irwin J. Goldsmith and Mrs. Bess (Goldsmith) Zuckerman (brother and sister)

Born 1917

Place of burial unknown – Buried 3/26/49

New York Times (Obituary Section) 3/26/49

American Jews in World War II – 327

____________________

Gorod, Sherman, PFC, 16169183, Purple Heart

14th Armored Division, 68th Armored Infantry Battalion

Mr. and Mrs. Abraham (5/1/87-5/61) and Sadie (Grawoig) (3/15/85-12/71) Gorod (parents), 311 East 69th St., Chicago, Il.

Born Chicago, Il., 3/16/24

Oak Woods Cemetery, Chicago, Il. – Buried 7/30/48 (Graveside Service)

Chicago Tribune 7/30/48

American Jews in World War II – 101

The Schwartz Family Tree, at Ancestry.com, includes this Class of 1942 Parker High School yearbook portrait of PFC Gorod.

____________________

____________________

Hart, Rudolph I., PFC, 32700046, Purple Heart

103rd Infantry Division, 411th Infantry Regiment, K Company

Mr. Maurice Hart (uncle), 132 Bella Vista Ave., Tuckahoe, N.Y.

Born New York, N.Y.

Epinal American Cemetery, Epinal, France – Plot B, Row 22, Grave 54

Casualty List 4/3/45

The Herald Statesman (Yonkers) 4/2/45

American Jews in World War II – 341

____________________

Levinsky, Stanley M. (Shmuel Moshe bar Ben Tsion), PFC, 13125947, Purple Heart, 1 Oak Leaf Cluster

35th Infantry Division, 134th Infantry Regiment, K Company

Wounded in action previously; approximately 6/17/44

Mr. and Mrs. Barney (1892-1949) and Pauline (1893-1977) Levinsky (parents), 237 S. 57th St., Philadelphia, Pa.

Born 6/1/22

Har Zion Cemetery, Collingdale, Pa. – Section A, Lot 550, Grave 1

Jewish Exponent 8/25/44, 3/2/45

Philadelphia Record 8/17/44, 2/20/45

American Jews in World War II – 536

____________________

Levy, Joseph Leonard, Pvt., 13141950, Purple Heart

90th Infantry Division, 357th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Benjamin Levy (father), 1439 Kennedy St., NW, Washington, D.C.

Luxembourg American Cemetery, Luxembourg City, Luxembourg – Plot E, Row 5, Grave 31

American Jews in World War II – 78

________________________________________

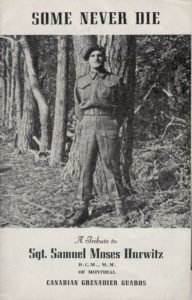

Sergeant Seymour Millstone and PFC Stanley Rubenstein were two of the seventy-six men – from the contingent of 350 American POWS sent from Stalag 9B (Bad Orb) to the Berga am Elster slave labor camp and assigned to Arbeitskommando 625 – who died, directly or indirectly during their imprisonment at Berga, or on the forced of the surviving POWs from the camp later. I’ve mentioned this event in blog posts about First Lieutenant Sidney Diamond, Pvt. Edward A. Gilpin, and Captain Arthur H. Bijur, while you can read about it in much more depth in an essay by William J. Shapiro, veteran of the 70th Infantry Division, at the Jewish Virtual Library.

Sergeant Millstone died on March 25, and PFC Rubenstein on April 4. They were among the twenty-six POWS who died while actually at Berga, per se. Forty-nine POW deaths occurred immediately commencing with the forced march of POWs from the camp on April 6 (not April 3, as described elsewhere), through April 23, 1945, only two weeks before the war in Europe ended. Aaron “Teddy” Rosenberg (Aharon bar Zev Ha Cahan) of Jacksonville, Florida, initially made a complete recovery from the effects of his imprisonment, but rapidly and irreversibly relapsed. He died in the United States on June 27, 1945, a little over two months after liberation.

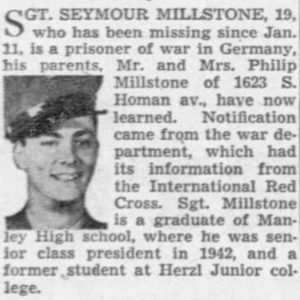

Millstone, Seymour, Sgt., 36696896

79th Infantry Division, 315th Infantry Regiment

Captured

Died (in reality, murdered) while POW 3/25/45

POW at Stalag 9B (Bad Orb), and, Berga am Elster (German POW # 27542)

Mr. and Mrs. Philip and Alice (Resnick) Millstone (parents); Miss Phyllis Millstone (sister), 1623 South Herman Ave., Chicago, 3, Il.

Also 201 South 8th St., Las Vegas, Nv.

Born Cleveland, Oh., 7/23/25

Netherlands American Cemetery, Margraten, Holland – Plot N, Row 15, Grave 12

American Jews in World War II – 110

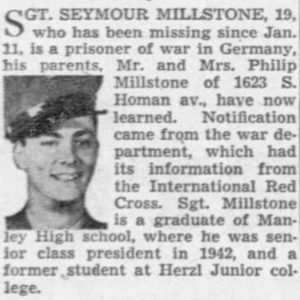

This newspaper item about Sgt. Millstone’s POW status is by FindAGrave contributor Jaap Vermeer.

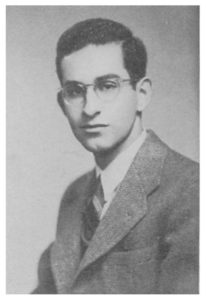

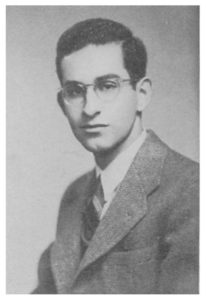

This portrait of Sgt. Millstone is via Ancestry.com.

____________________

____________________

Rubenstein, Stanley (Yehosha bar Eliahu Shmuel), PFC, 33977622, Purple Heart

79th Infantry Division, 315th Infantry Regiment

Captured

POW at Stalag 9B (Bad Orb), and, Berga am Elster (German POW # 27465)

Died (murdered, in reality) while POW 4/4/45

Mr. and Mrs. Simeon and Sarah (Finkelstein) Rubenstein (parents), Earl (brother), 1171 Ocean Parkway, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Born New York, N.Y., 9/14/24

Long Island National Cemetery, Farmingdale, N.Y. – Section J, Grave 14645; Buried 4/13/49

New York Times – Obituary Page (Memorial Section) 9/14/45

New York Times – Obituary Page 4/10/49

American Jews in World War II – 423

________________________________________

In researching this story some years back at the United States National Archives (I considered writing a book about this story. But, I decided not to. That’s another story.) Well anyway, to quote an earlier blog post:

The books – both released in 2005 – are: Soldiers and Slaves : American POWs Trapped by the Nazis’ Final Gamble, by Roger Cohen and Michael Prichard, and, Given Up For Dead : American GIs in the Nazi Concentration Camp at Berga, by Flint Whitlock. A review of Whitlock’s book by John Robert White can be found at H-Net Reviews, under the title Fitting Berga into the History of World War II and the Holocaust.

The documentary, Berga: Soldiers of Another War, was the subject of reviews and discussions by the International Documentary Association (Kevin Lewis – Remembering the POWs of ‘Berga’: Guggenheim’s Final Film Celebrates His Army Unit) and The New York Times (Ned Martel – G.I.s Condemned to Slave Labor in the Holocaust). The last project of documentary film-maker Charles Guggenheim, Soldiers of Another War was released in May of 2003, eight months after his death.)

____________________

In any effort, as part of my research, I discovered that the names of the POWs at Berga had been recorded in two lists that differ appreciably in depth and format.

One list is quite simple in organization, and has information fields for a POW’s surname and given name, German POW number, rank, date of birth, vocation or profession, height in meters, and eye color.

The other list is much more complex; its “header” page (scanned from a photocopy) is shown below, followed by a German-language transcription and English-language translation.

USA

350 U.S.A.

(Datum) 16.2.45

28.März 1945

Zu= und Abgänge

des Kriegsgefangenen = Lagers IX B

Abgangs Meldung Nr. 1937 für Stalag IX B

Zugangsmeldung 176 für Stalag IX C

Bemerkungen:

1. Die liste ist zugleich die Meldung über die ausgegebenen Erknunngsmarken.

2. Die Abgänge sind hinter den Zugangen geschlossen einzutragen.

3. ”Matrikel-Nr.” = Nr. der Stammrolle ufw. des Kr. Gef. in seinem Heimatlande.

An die

“Wehrmachtauskunftstelle fur Kriegerverluste und Kriegsgefangene”

Berlin

_____

USA

350 U.S.A.

(Date) 2/16/45

28 March 1945

Arrivals and Departures

of the prisoner of war = Camp IX B

Departure Report No. 1937 for Stalag IX B

Entry message 176 for Stalag IX C

Remarks:

1. The list is at the same time the notification of the identification marks issued.

2. The departures are to be entered closed behind the arrivals.

3. “Matriculation No.” = Number of the master role etc. [military serial number] of the prisoner of war in his home country.

To the

“Wehrmacht Information Center for Lost Soldiers and Prisoners of War”

Berlin

____________________

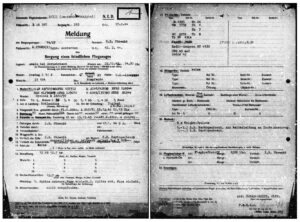

The image below, also scanned from a paper photocopy, shows the final of the 44 pages comprising this “larger” list, with the names of Stanley Rubenstein, Seymour Millstone, and Jack Bornkind (Yakov bar Nachum), who died on April 23, literally moments before a group of POWs were liberated by American forces, being the 348th, 349th, and 350th entries.

Note that the data fields include the soldier’s German-assigned POW number, surname, first name, date of birth, parent’s surnames, residential address and name of “contact”, Army serial number, and place/date of capture. Ironically, on neither list does the soldier’s religion or ethnicity actually appear. However, on the “smaller” of the two lists (not shown here) the names of the Jewish POWs comprise the first 77 entries, while in this “larger” list – overall at least – surnames / religions / nationalities are generally (generally) arranged at random.

Finally, an opinion: While I’ve used the word “died” to describe the fate of Seymour Millstone and Stanley Rubenstein, in moral, ethical, and philosophical fact, they and the seventy-four others who did not survive either imprisonment at Berga, or, the death march afterwards (and in the case of Aaron T. Rosenberg, its after-effects) were, simply and honestly, murdered.

____________________

Schreier, Bernard S., PFC, 32811465, Bronze Star Medal, Purple Heart

78th Infantry Division, 309th Infantry Regiment

Mr. and Mrs. Charles (12/20/90-5/25/64) and Pauline Schreier (parents), 424 Grand Concourse, New York, N.Y.

Born Bronx, N.Y., 5/27/23

Ardennes American Cemetery, Neupre, Belgium – Plot D, Row 8, Grave 54

Casualty List 11/1/1945

American Jews in World War II – 433

____________________

Schwartz, Norman, T/5, 32805024, Engineer, Purple Heart, in Belgium

87th Infantry Division, 312th Engineer Combat Battalion

Mr. Max Schwartz (father), 780 Pelham Parkway, New York, N.Y.

Born 1924

Casualty List 3/15/45

Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery, St. Louis, Mo. – Section 82, Grave 1J; Buried 3/9/50

American Jews in World War II – 436

This image of the collective grave of T/5 Schwartz and eight comrades – all presumably killed in the same January 11, 1945 incident – is by FindAGrave contributor Eric Kreft.

____________________

____________________

Tannenbaum, Henry (“Hershy”) Irving (Yitzhak Tzvi bar Ezra Yisrael), Pvt., 33752792, Purple Heart, 1 Oak Leaf Cluster, in Belgium

83rd Infantry Division, 331st Infantry Regiment, F Company, 2nd Battalion

Mrs. Bertha (Fiedel) Tannenbaum (wife), Samuel Victor (son), 110 Division Ave., Brooklyn, N.Y.

Mr. and Mrs. Abraham and Molly Tannenbaum (parents), Leon and Sadie (brother and sister)

Born Brooklyn, N.Y., 2/29/16

Mount Hebron Cemetery, Flushing, N.Y. – Williamsburg Bikur Cholim Society, Block 25, Reference 9, Section G, Line 8, Grave 11

War Department Release 12/19/44

The Jewish War Veteran, Spring, 1989

American Jews in World War II – 459

You can read more about Pvt. Tannenbaum, the battle in which he lost hi life, and especially the impact of his death on his family, in this moving essay by his son, Samuel Victor, at the American WW II Orphans Network.

Or, to quote William Faulkner in Requiem for a Nun, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

These three photos of Private Tenenbaum, his wife and son, and matzeva, are via FindAGrave contributor THR (from Samuel Tannenbaum).

__________

Henry Tannenbaum, his wife Bertha, and their son Samuel, at Livingston Manor, New York, in July of 1944.

xxxxx

__________

Wounded in Action

Firestone, Berel (Beryl), T/4, 12154917, Radio Operator, Purple Heart, in Luzon, Philippines

Miss Lynn Spear (fiancee), 34-20 83rd St., Jackson Heights, N.Y.

Mr. Maurice Firestone (father), Boston, Ma.

Born 1923

Casualty List 3/17/45

Long Island Star Journal 3/17/45

American Jews in World War II – 309

____________________

Orlow, Michael H.M., PFC, 33791740, Purple Heart, 2 Oak Leaf Clusters, in Luxembourg

Mrs. Dora Orlow (wife), 1639 W. Huntingdon St., Philadelphia, Pa.

Mr. Morris Orlow (father), Miriam (sister)

Born 1911

Jewish Exponent 3/9/45

American Jews in World War II – 542

____________________

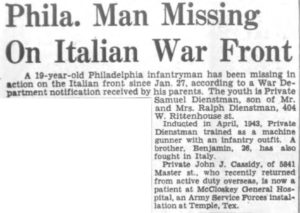

On November 11 of the year 2010, an article by David Rubin appeared in The Philadelphia Inquirer. Probably not-so-coincidentally published on Armistice Day – the (92nd) anniversary of the end of World War One, otherwise known as the “Great War” – the article recounts the WW II military service of Rubin’s uncle Robert C. Paul, who served as an infantryman in the European Theater of War. Though a single article, Rubin’s reminiscence is in reality two parallel stories: It focuses on his uncle’s experience in the army as recounted through correspondence with his immediate family, and then segues into the war’s unsurprisingly indelible impact on Robert Paul’s life over subsequent decades. While this impact was immediately physical (his uncle was on January 11, 1945 wounded by shrapnel in the right foot and side), on different and perhaps deeper level it was political; perhaps psychological; perhaps spiritual; perhaps more.

A transcript of David Rubin’s article follows, in turn followed by some accompanying images scanned from the print (remember that thing called print?!) edition of the Inquirer.

A World War II Soldier’s Letters Bring Back the Horrors of War

As a member of the Ninth Infantry Division, it was my cousin Bobby’s lot to be tethered to the front line in some of World War II’s most fearsome fighting.

Normandy. The Huertgen Forest. The Battle of the Bulge.

He rarely mentioned any of it.

But when he lay in the hospital, dying of cancer in the spring of 2009, he couldn’t stop talking. And the morphine made his accounts suspect. It wasn’t clear what he’d seen, what he’d dreamed.

When an uncle sent me a box a few months ago stuffed with my cousin’s letters from the war, I finally had the opportunity to learn about the events that shaped him, and that helped tear him apart.

At first Bobby wrote home so often his letters didn’t bear the date, just the day.

“Thurs,” begins an early correspondence to his mother from infantry camp. “The boys thank you for the food. Even C rations would taste good.”

Pvt. Robert C. Paul was undergoing training at Fort Meade, Md. He was writing back home to his mother, my great-aunt Ethel.

“My moonshiner friends built a blazing fire in the downpour and I kept warm for a while. But then I had to fix my booby traps.”

The year was 1943. Bobby was 19, a bespectacled twig at 5-foot-9 and 130 pounds. When he was drafted, he’d just finished his third year at Harvard College.

Bobby always thanked his good fortune to be paired with Southern boys who were crack shots. He was an unlikely warrior, a sensitive soul who loved Abbott and Costello movies, Walt Whitman poems, and his mother’s fruitcake.

He was, by his own account, the world’s worst soldier, the very label one of his drill sergeants pinned on him.

“Fine,” went Bobby’s reply. “Then send me home.”

Instead, they sent him to Normandy on July 1, 1944, three weeks after the invasion. Bobby’s father was dying of kidney disease, and after a short leave my cousin caught up with the 39th Infantry Regiment, the fighting already in progress.

Most of his letters are written in pencil and scrawled on stationery from the USO, the Army, the Marine Corps, whatever he had handy. He reported to his mother, a fellow cinema fan, on the movies he saw on leave. He asked his father about baseball, hockey, and the ponies. He hungered for news about his many cousins and friends back home.

The chatty tone ended with the letter dated Oct. 16, 1944:

“Here it is blue Monday and I am in Paris. It took a shell to get me here. I am all right, feeling better physically than mentally. I got it in my left arm, but it is not too bad. I’ll be none the worse for it when I get better.”

He tried to assure his parents that the hospital was modern, the doctors first rate. He didn’t want anyone worrying, or blaming themselves for letting him ship out, as though they’d had a choice.

“This is devilish business and one has to have faith,” he wrote. “I thought that the battle would make me a stronger person, but I realize how weak I still am. When the shock of combat has worn off, I realize that it is but a bluff, that mask of bravery that I have been carrying on under.”

Bobby’s recovery took a couple of months. He had been back with his company in the Huertgen Forest for just a matter of days when he was mortared again.

His wounds that time were serious, despite the Army telegram that reported he’d been injured only “slightly.”

The shell landed Jan. 11, 1945, in Belgium near the German border. Shrapnel blew off bits of three toes on Bobby’s right foot and raked his thighs and arms. He was evacuated to a hospital in England.

He tried to dwell on the positive when he wrote his mother on Red Cross stationery:

“I was very fortunate this time because I was wearing glasses and had no helmet on when I got hit. It was around midnight and they had to use a snow buggy to get me out. The company medics are the heroes of this war because they take care of the wounded regardless of the risks. They go through everything with nothing but a red cross for protection.”

Now Bobby talked about how the war was going from his perspective, how although everyone was talking about the Russian offensive, he felt the Germans were too stubborn, too tough to quit so soon.

He’d fought for seven months, across France to the Ardennes, then helped capture Roetgen, the first German town conquered in the war. He was exhausted.

With the war winding down, he must have sensed he would not see combat again – he’d be sent home after five months in the hospital to recuperate at Camp Edwards in Massachusetts. He received his discharge from there that summer, a 21-year-old private first class awarded the Purple Heart.

For the rest of his life, Bobby would rally support for antiwar movements. He never let my brother and me play with guns.

“The experience I went through wasn’t pleasant,” he wrote from his English hospital to his mother. “It didn’t prove anything, but it was part of my sacrifice for my country. I haven’t done much, but some of my critics should have been over here. This is the infantry’s war, but they will get no credit when the war is over. The rear echelon boys who have it made will be the toasts of the town. I’ll be glad enough to just get back to you, but I will know that I did my part.”

When we were about to clean out his house in Sharon, Mass., a year ago last spring, Bobby wanted to make sure we grabbed the Nazi flag because some people might not understand why he’d kept it. I wrote a column about my dilemma: What’s the right thing to do with it?

We wound up giving it to the town’s historical society, with his obituary and my column. They’re all on display today, Veterans Day. The woman who runs the society said they describe the flag as a souvenir from the war.

I have to think Bobby would laugh at that notion, as though the Nazi flag were some trinket, like a miniature Eiffel Tower, and not the symbol of the evil that made him reach so far down inside himself, not the reminder of the blood and the screams and the terror he endured.

Or maybe his voice would rise excitedly, and he’d yell, because little things would often upset him.

Reading his letters, I have a better sense why.

Here’s a biographical record about Robert C. Paul:

Paul, Robert Carlton (Reuven Caleb bar Shimon HaLevi), PFC, 31358523, Purple Heart, 1 Oak Leaf Cluster

9th Infantry Division, 39th Infantry Regiment, I Company

Wounded January 11, 1945; Slightly wounded in action previously (approximately October 15, 1944)

Mr. and Mrs. Sidney R. and Ethel (Shapiro) Paul (parents), 133 South Main St., Sharon, Ma.

Born April 22, 1924; Died March 9, 2009; Buried at Rabbi Isaac Elchonon Cemetery, Everett, Massachusetts

Philadelphia Inquirer – November 11, 2010

American Jews in World War II – Not Listed

____________________

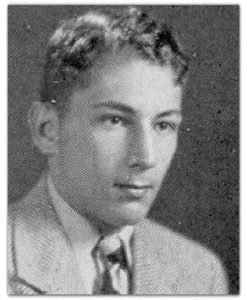

Robert Paul, probably as seen in his high school graduation portrait.

__________

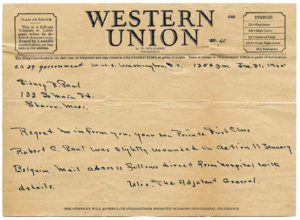

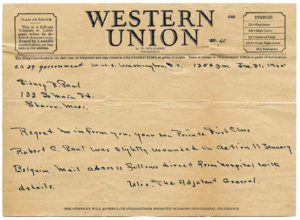

Here’s an example of state-of-the-art communication in a world refreshingly prior email and Facebook (Facebook? – gag!): A Western Union telegram. In this case, the War Department’s message of January 31, 1945, to PFC Paul’s father Sidney, informing him of Robert’s wounding on January 11, 1945. Very unusual for a telegram, the text takes the form of a handwritten message, rather than typed text. A transcription follows…

Sidney R. Paul

133 So Main St.

Sharon, Mass.

Regret to inform you, your son Private First Class Robert C. Paul was slightly wounded in action 11 January Belgium. Mail address follows direct from hospital with details.

Ulio, The Adjutant General

__________

One message generates another. Evidently, Robert’s mother sent an inquiry to the War Department upon receipt of the January 31 communication. Her reply yielded this message, generated in the typical telegram format of lines of typed text glued to the Western Union stationary.

PTA 415 54/55 GOVT = WUX WASHINGTON DC 1 449P

MRS SIDNEY R PAUL =

133 SOUTH MAIN ST SHARON MASS RTE BSN=

REURTEL NO INFORMATION RECEIVED CONCERNING CONDITION OF YOUR SON PVT FIRST CLASS ROBERT C PAUL SINCE PREVIOUS COMMUNICATION REPORT RECEIVED DID NOT GIVE NATURE OR EXTENT OF WOUNDS REPORTS OF HIS CONDITION WILL BE PROMPTLY FORWARDED TO YOU UPON RECEIPT ASSURE YOU OUR SICK AND WOUNDED SOLDIERS ARE RECEIVING BEST POSSIBLE MEDICAL CARE =

J A ULIO THE ADJUTANT GENERAL

__________

The soldier has returned: This V-Mail letter of February 22, 1945, was sent by Robert to his mother while he was recovering from his wounds at “U.S. Hospital Plant 4103”.

Dear Mother:

I am beginning to find one-sided correspondence overwhelming. There isn’t much to write about with my routine pleasantly unexciting. I can report that I am getting along quite nicely. I can use a wheelchair and can hop around the ward for short distances, so I am not bed-bound. I am not able to get to the cinema yet, but I don’t think it will be long now. The Pacific war now seems to be getting rougher every day. Byrnes is crouching down on everybody & everything. But I know that you will carry on. You should[n’t?] be forced to resort to K-rations & foxholes. Take care of Father & yourself and give my regards to all the family.

Hugs & Kisses

Bobby

The “Byrnes” referred to in the above letter was James F. Byrnes, head of the Office of Economic Stabilization and the Office of War Mobilization.

__________

Somewhere in the United States, Robert on crutches during his recovery.

____________________

Pick, Harold R., Sgt., 36649783, Purple Heart

79th Infantry Division, 315th Infantry Regiment

Captured; POW at Stalag 9B (Bad Orb)

Mrs. Ida Pick (mother), 533 Addison St., Chicago, Il.

Casualty List 5/16/45

American Jews in World War II – 112

____________________

Weisbein, David, PFC, 33811447, Purple Heart, in Belgium

Mrs. Sarah Weisbein (wife); Ellen (daughter), 2519 S. Marshall St., Philadelphia, Pa.

Born 1913

Jewish Exponent 3/23/45

Philadelphia Inquirer and Philadelphia Record 3/10/45

American Jews in World War II – 559

________________________________________

Some other Jewish military casualties on January 11, 1945, include the following…

Soviet Union / U.S.S.R. (C.C.C.Р.)

Red Army [РККА (Рабоче-крестьянская Красная армия)]

Killed in Action

Davidovna, Aleksandra Abramovna (Давидовна, Александра Абрамовна), Lieutenant (Лейтенант)

Senior Nurse (Female Soldier) (Старшая Медицинская Сестра)

Mobile Field Hospital 3537

Wounded 1/10/45; Died of wounds 1/11/45 at Mobile Surgical Field Hospital 171

Born 1923, city of Moscow

Mother: Vera Semenovna “Meldenson” (Mendelson?)

Freylikhman, Motel Shlemovich (Фрейлахман, Мотель Шлемович), Lieutenant (Лейтенант)

Infantry – Senior Medic (Фельдшер Старшии)

66th Guards Rifle Division, Medical Services

Born 1923, Zhytomyr Oblast

Father: Shlema Zayvelovich

Fuksman, Abram Borisovich (Фуксман, Абрам Борисович), Lieutenant (Лейтенант)

Armor – Self-Propelled Gun Commander (Командир Самоходной Установки)

38th Artillery Regiment, Military Post 22131 “E”

Died of disease / illness at Clearing and Evacuation Hospital 1353

Born 1905, Chelyabinsk or Zhitomir

Wife: Anna Sheleevna Shterman

Krasnoshchek, Khaim Tsalevich (Краснощек, Хаим Цалевич), Lieutenant (Лейтенант)

Infantry – Battery Commander (Командир Батареи)

100th Artillery Regiment

Father: Tsal Mardukhovich Krasnoshchek

Milkher, Genrikh Abramovich (Мильхер, Генрих Абрамович), Lieutenant (Лейтенант)

Infantry – Rifle Company Platoon Commander (Командир Взвода Стрелкового Роты)

1st Polish Army, 4th Rifle Division, 12th Rifle Regiment

Born 1918, Warsaw

Sagalovich, Naum Isaakovich (Сагалович, Наум Исаакович), Lieutenant (Лейтенант)

Infantry – Firing Platoon Commander (Командир Огневого Взвода)

100th Howitzer Artillery Regiment

Missing in Action

Born 1905

Wife: Mariya Izrailovna Shenderovna

Taymufet, Mayor Gertsovich (Таймуфет, Майор Герцович), Guards Red Army Man (Гвардии Красноармеец)

Armor – Sapper (Сапер)

27th Guards Autonomous Heavy Tank Regiment, Sapper Platoon

Missing at Pruvayni, Latvia

Estra Moiseevna Taymufet (mother), Stalinskiy Oblast, Kamenets-Podolsk, Stalina Village, House 120

Born 1922, city of Kamenets-Podolsk

Mother: Estra Moiseevna Taymufet

Polish People’s Army

Killed in Action

Cymer, Henryk, Cpl.

12th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Jakub Cymer (father)

Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II, Volume I – 14

____________________

Gryner, Jozef, Pvt.

12th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Abram Gryner (father)

Born 1918

Aleksandrow Cemetery, Lodzkie, Poland – Q A1 R 3 No. 1

Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II, Volume I – 26

____________________

Milcher, Henryk, 2 Lt., at Warsaw, Poland

12th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Abrahama Milcher (father)

Born Mazowieckie, Warsaw, Poland, 1919

Warsaw, Aleksandrow Street Cemetery, Warsaw, Poland

Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II, Volume I – 49

____________________

Robert, Bronislaw, Cpl.

10th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Dawid Robert (father)

Warsaw, Aleksandrow Street Cemetery, Warsaw, Poland – Q A2, R 12 No. 2

Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II, Volume I – 58

France – Armée de Terre

Killed in Action

Rosenberger, Hans, Sergent-Chef (“AC-21P-146645”), at Obenheim, Bas-Rhin, France

Bataillon de Marche No. 24

Born 6/11/08

Carre communal “Kogenheim”, Kogenheim, Bas-Rhin, France – Tombe individuelle, No. 2

(First name from SGA “Seconde guerre mondiale” web site – SGA “Sepultures de Guerre” web site gives name as “Jean”. SGA “Seconde guerre mondiale” web site lists Unite as “1ere D.F.L.”, while SGA “Sepultures de Guerre” web site lists Unite as “B.M. 24”.)

And to conclude (! – ?), here are some references…

Books (Author Listed)

Dublin, Louis I., and Kohs, Samuel C., American Jews in World War II – The Story of 550,000 Fighters for Freedom, The Dial Press, New York, N.Y., 1947

Maurer, Maurer, Combat Squadrons of the Air Force – World War Two, Albert F. Simpson Historical Research Center and Officer of Air Force History, Headquarters, USAF, 1982

Russell of Liverpool, Edward F.L.R., Baron, The Knights of Bushido: A History of Japanese War Crimes During World War II, Skyhorse Publishing, New York, N.Y., 2008

Meirtchak, Benjamin, Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II: I – Jewish Soldiers and Officers of the Polish People’s Army Killed and Missing in Action 1943-1945, World Federation of Jewish Fighters Partisans and Camp Inmates: Association of Jewish War Veterans of the Polish Armies in Israel, Tel Aviv, Israel, 1994

Smith, Paul T., The Pacific Crusaders, Mohave Books, Ca., 1980

Rust, Kenn C., Thirteenth Air Force Story, Historical Aviation Album, Temple City, Ca., 1981

Books (No Specific Author)

The Crusaders: A History of the 42nd Bombardment Group (M), 1946, Army & Navy Pictorial publishers, 234 Main St., Baton Rouge, La.

The Pictorial History of the 444th Bombardment Group, Very Heavy Special, 1947

A Bunch of Websites…

B-25J 43-27979 and Her Crew, at…

Pacific Wrecks

B-29 42-665226 and Her Crew, at…

Pacific Wrecks

Divah World blog

677th Bomb Squadron, 444th Bomb Group

12 O’Clock High! – Luftwaffe and Allied Air Forces Discussion Forum (under “Japanese and Allied Air Forces in the Far East”)

Dark and Bizarre Stories

Fukudome War Crime Trials, at…

World War II Document Archive – Pacific Theater Document Archive formerly at wcsc.berkeley.edu (no longer available)

Trial Record of Singapore War Crimes Case No. 235/1102 (Vice Admiral FUKUDOME Shigeru, Rear Admiral ASAKURA Bunji, Commander INO Eiichi, Vice Admiral IMAMURA Osamu, Captain MATSUDA Gengo, and Capt SAITO Yakichi), held on 9, 12, 17-20, 23 and 27 Feb 1948, at www.ocf.berkeley.edu

Pvt. Henry I. Tannenbaum, at…

American WW II Orphans Network

Geni.com

Thomas D. Curry and the men of F Company, 331st Infantry Regiment, 83rd Infantry Division

PFC Robert C. Paul, at…

Rubin, Daniel, “A World War II Soldier’s Letters Bring Back the Horrors of War”, The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 11, 2011 (formerly here; no longer available)

384