A number of my posts pertaining to Jewish soldier in the Second World War have focused on or referenced German-born Jews who served in the Allied armed forces. One such soldier was Private Eric M. Heilbronn, who, serving in the United States Army’s 34th Infantry Division, was killed in Italy on January 7, 1944.

Eric Heilbronn’s story is particularly notable because he was the subject of a short biography in the German “exile-newspaper” Aufbau (“Reconstruction”), which was accompanied by his photograph. A brief biographical profile of Erich appeared in my post pertaining to Captain and Silver Star recipient Howard K. Goodman of the United States Marine Corps, who was killed in action on January 7, 1944.

And, there Erich Heilbronn’s story remained. That is, until late 2020 (hey, time flies…) when I received a most interesting communication from Dr. Bastiaan van der Velden of the Open University of the Netherlands, which follows below:

Dear Michael

Thanks for your mail. Erich’s father was born in the same village as my family [Tann] – and the two families married a couple of times, that’s why I have the info collected. I will sent you also a wetransfer for a larger file. I think there you find all the sources I used (you can search them).

A youth picture [of Erich Heilbronn, within a biography of Emil and Fanny Jondorf, on page 8].

Success with the work

Kind Regards

Bastiaan

In light of Bastiaan’s generous contributions, this post presents a more complete picture of Erich Heilbronn and his family, seen through the eyes of his friend, fellow German-Jewish émigré soldier, Frank A. Harris (originally Frank Siegmund Hess).

But first – to recapitulate and save you from redundant mouse-clicks! – here’s the biographical record of Pvt. Erich Heilbronn which appears in the above-mentioned blog post about Captain Goodman, including the photo and article that originally appeared in Aufbau.

____________________

Heilbronn, Eric Moses (Moshe ben Yitzhak), Pvt., 32816833, Purple Heart

United States Army, 34th Infantry Division, 168th Infantry Regiment, A Company

Rabbi Isak [6/4/80-6/9/43] and Mrs. Erna Esther [2/9/92-5/3/77] Heilbronn (parents), Cecil and Irmgard (Pinto) Heilbronn, 382 Wadsworth Ave., New York, N.Y.

Born Nurnberg, Germany, 1924

Burial location unknown

Casualty List 2/22/44

Aufbau 5/12/44

American Jews in World War II – 342

The May 12, 1944 edition of Aufbau, in which news about Private Heilbronn’s death appeared in the far left column, is shown below:

Here’s the news item about Private Heilbronn, which is followed by a transcription of the original German, and an English-language translation:

ist im Alter von nur 20 Jahren auf dem italienischen Kriegsschauplatz gefallen. Er war seit dem 7 Januar dieses Jahres als vermisst gemeldet, aber erst vor wenigen Tagen hat seine Mutter die Nachricht von seinem Tod erhalten.

Pvt. Heilbronn ist der Sohn des ihm sieben Monate im Tod vorangegangenen Rabbiners Dr. Isaak Heilbronn und stammte aus Nurnberg. Er widmete such insbesondere der Jugendbewegung innerhalb der Gemeinde seines Vaters, der Congregation Beth Hillel, und versuchte, die eingewanderte deutsch-jüdische Jugend mit der americanischen Weltanschauung vertraut zu Machen und sie fur die Ideale Amerikas zu begeistern.

Pvt. Heilbronn kam Antang 1939 nach Amerika, absolvierte die High School in New York und nahm später Abendkurse in Buchprüfung am City College. Tagsüber war er bei der Federation of Jewish Charities beschaftigt. Im März 1943 rückte er in die Armee ein.

Pvt. Eric M. Heilbronn

died at the age of only 20 in the Italian theater of war. He was reported missing since January 7 of that year, but only a few days ago his mother received the news of his death.

Pvt. Heilbronn is the son of Rabbi Isaac Heilbronn from Nurnberg, who died seven months before his death. He was particularly dedicated to the youth movement within his father’s congregation, Congregation Beth Hillel, and tried to familiarize immigrant German-Jewish youths with the American world view and to inspire them with the ideals of America.

Pvt. Heilbronn came to America in 1939, graduated from high school in New York and later took evening classes in auditing at City College. By day he was employed by the Federation of Jewish Charities. In March 1943 he joined the army.

____________________

Frank Harris’ story can be found in the document “Biography of Frank A. Harris, Fürth“, at the website of RIJO Research, and, in the form of an interview by Jeffrey Boyce that was published at the website of the “National Food Service Management Institute – Child Nutrition Archives”, I think in late 2014; I think no longer accessible! However, having kindly been given access to this interview by Bastiaan, the text of the document – up to and including Frank’s account of discovering Erich’s grave near Cassino, Italy, in early 1944 – follows. (There’s more to Frank Harri’s story, but it’s not included here.)

The transcript of the Jeffrey Boyce interview then is followed by a transcript of Frank’s biography, from in the Leo Baeck Institute’s Frank A. Harris Collection, 1977-1992.

For both documents, I’ve highlighted those sections directly pertaining to Private Erich Heilbronn in dark red. (Like “this”.)

__________

Frank A. Harris

Oral History

Interviewee: Frank A. Harris

Interviewer: Jeffrey Boyce

Interview Date: June 8, 2011

JB: I’m Jeffrey Boyce and it’s June 8, 2011. I’m here with Mr. Frank Harris in Somers, New York. Frank is going to share his story of child nutrition and some other things about his life with us. Welcome Frank and thanks for taking the time to talk with me today.

FH: Thank you very much and thank you for coming a long distance, and we much appreciate it.

JB: Happy to do it. We’ve been working on this about two years now haven’t we?

FH: That’s right. That’s just about what it is.

JB: Could we begin today by you telling me a little bit about yourself, where you were born and where you grew up?

FH: All right. I was born in Furth, Bavaria, Germany. Furth is a city next to Nuernberg. It’s like Minneapolis and St. Paul, kind of a twin city. I was born on December 7, 1922, the second child born in 1922, which was very unusual. My sister was born on January 3rd. When my mother became pregnant again she was hesitant to tell my father, but in the long run she couldn’t hide it. He became so upset muttering “People think I have nothing better to do.” But when I did come I was totally accepted and my mother was delighted because she raised us almost like twins.

JB: So you were born in the same year?

FH: Same year, 1922, which was very unusual, so I could really say I was an accident, but a happy accident.

JB: Tell me a little bit about your childhood. You started school in Germany?

FH: Yes, I started school in Germany. I started at an elementary school in 1929. As you know, Hitler came to power in 1933. In the beginning nothing much happened. After I graduated from elementary school we went to high school, where the atmosphere became quite uncomfortable for us. We had four Jewish students in our class. Classes are not twenty-four like here in the United States. We had about 35-40 students. Our classroom teacher was Professor Berthold, who was marvelous. He wrote all the French textbooks in Germany. He himself was not a Nazi, but we had two gym teachers, Mr. Vilsmaier & Mr. Steinhardt. We the four Jewish kids were superior in all athletic activities. The students couldn’t accept us because the teachers pictured all Jews as clumsy and smelly, and would order the gentile students, “Ok. It’s time to beat up the Jews.” So our classroom teacher, Dr. Berthold, urged my father to take Franz out (my name was not yet Frank) and enroll him in the Jewish school.” Myself and the other Jewish boys were taken out of the public high school and were enrolled in the Jewish high school in the Blumenstrasse in Furth. This is where I met all the youngsters who have remained my friends for a lifetime. Our teachers were excellent scholars. We were taught many subjects, not only Hebrew. The director, Dr. Prager, was superior, and the chemistry and math teachers were excellent. We had a wonderful class, of about 30-35. As of today there are still 12-15 alive. Some have died in the Shoah, (in the Holocaust). Many of them have immigrated to the U.S., Canada, the U.K., Australia, etc. We have maintained a wonderful relationship with all the survivors.

JB: I understand one of those men is quite well-known to most people who would be reading this – Mr. Kissinger.

FH: That’s right. Henry Kissinger was one of my classmates. He sat right behind me. I should tell you – I’m not claiming that I was a great student – I really wasn’t. I was great in imitating most of the teachers. That was my greatest contribution. Henry was not the greatest student either. He was a good student. He was interested in history. We had an outstanding class of really outstanding students, but Henry was not an outstanding student. He was a good student. And I can truly say that we have remained friends to this very day.

JB: Were there any sort of nutrition programs in the schools you attended in Germany?

FH: No, we did not have any nutrition programs in the schools. As a matter of fact school days were divided. We attended school in the morning and at noontime we went home for lunch. And it was not really lunch. We like most families had our big dinner at noontime. My father, who was the owner of a toy factory, came home for our big meal at noontime, and then took a nap, while my sister and I went back to school in the afternoon. We did not have a nutrition program. We had all our meals at home. In order to get my dad home on time for our noon-time meal our dog Bobby ,who was a mean little creature , but very smart, left the house, ran down to my dad’s business, waited until my dad came out, and then raced back to alert us that Dad was on his way. He never walked with him, but when Bobby arrived home; my mother could get the soup and the meat and everything ready, because Dad was on his way home.

JB: Sounds like a smart dog.

FH: Yes.

JB: You spoke earlier about why you changed schools. Things were getting bad in Germany. Then you ended up leaving Germany. Tell us about that.

FH: Yes, ok. That came a bit later. You have no doubt heard of the Kristallnacht, November 9, 1938, when the Germans used as an excuse that a secretary at the French Embassy in Paris was killed by a Jew, to round up all the Jews in Germany and burn all the synagogues. We were awoke at three o’clock in the morning. The doorbell rang and some SA men, the home forces of the secret police, came to our house to arrest us. Interestingly enough one of them was one of my father’s World War I comrades. My Dad fought in the First World War and felt nothing ever could happen to him because he was born and lived in Germany all his life. No matter whatever the Nazis did, whatever the Nazis said, nothing will ever happen to us. But that night his Army comrade arrested him and all of us. The other SA man that picked us up was the owner of the delicatessen store whose business flourished because of his Jewish clientele. And we had very little time just to get dressed. They took us to a place called Plaerrer, where all the Jews were assembled. We marched through town. Next to me was a little girl. She was six years my junior. I only had one pair of gloves that I shared with little Eva because it was November and bitter cold already. It was supposed to be an action that nobody knew about, but the entire population was out. They screamed and they hollered and they spat at us. And we marched to this place called the Plaerrer, where some of us were beaten up. Our little rabbi was asked to step on the Holy Bible, the Holy Torah, and when he refused to do this, he too was beaten up. In the background we could see all of our synagogues were aflame. We had one courtyard with one Haupt (Main) and four other smaller synagogues. The Nazis burned them all down that day. Later on we were marched to a huge auditorium. This auditorium was called the Berolzheimerianum that was donated by a Jew many, many years ago. We were lectured on the history of the Nazis, and why the Nazis are superior to everyone else, the superior Aryan race. First they discharged the women and the girls. Afterwards they released boys under sixteen. I was one month shy of sixteen, born on December 7th, and this was only November 9th. Therefore I was released while all the men were taken to the Justizpalast in Nuernberg, the very building where, after the war, all the Nazi criminals were put on trial. All the adult men were kept overnight. My friend Eva, the one I shared the gloves with, went with me to the Gestapo. We had the courage to go, pleading to learn where they had taken our Pappas. They told us that they were taken to the Justizpalast. We went home to get some chicken soup, and returned to the Justizpalast to give the chicken soup to the guard, asking him to deliver it to our fathers. Much, much later after their release, we found out that they never got the chicken soup. The guard must have eaten the chicken soup prepared by Jews. Along with all other men, my father was taken to a concentration camp, called Dachau. In order to gain his release my mother and I were summoned to the Gestapo, the secret German police, to sign over my father’s business – the co-owner of a toy manufacturing company – and his Mercedes car to the tune of twenty marks, which is equal to about $10-15. They indicated any reluctance on our part to sign could become a death sentence for my dad. Therefore we shall never ever see him again. And this is when I learned the real priorities very early in my life. Not what was important the day before – my father’s business and the car, the jewelry or the Kristall that we owned – no, what was important was to get my father out of the K.Z. to allow us to function as a family once again, and get out of Germany. While my father was in Dachau we went to the American Consulate in Stuttgart, to receive a number to allow us to immigrate to the United States. There was a quota system. We got our number – somewhere in the 14,000s – I will get back to this part of my life a little later. My father was released five weeks after his arrest. He was a totally broken man. His first concern after his release was to get me out, since by that time I’d turned sixteen. I quickly attended a cooks and bakers school to take a speed course in cooking and baking. On March 7th or 9th, my dad – not my mother who was too upset – took me in the middle of the night to the railroad station to take a train with lots of other children called the Kindertransport, destination Holland.

JB: This was 1938?

FH: 1939. March of 1939. And Jeff, I will never forget the feeling when the train pulled into the station and I climbed aboard. We had all these kids, some as young as three or four years old, and the train pulling out seeing your – in my case my father – while others seeing their parents at the railroad station, really not knowing if they’ll ever see them again. I was fortunate. I saw my parents again, but many, many of the other children never saw their parents again. They didn’t understand why they were sent out of Germany. They begged their parents to let them stay with them. It was the greatest sacrifice that these parents had to make, to send their children out, to gain their freedom, even if in the long run they themselves couldn’t get out. So we crossed the border and arrived in Holland, where we stayed first at a camp in Rotterdam close to the harbor. Later on we were taken to a monastery, to be taken care of by nuns, who absolutely mistreated us. This was very unusual because the Dutch people in general were very helpful. I stayed there for a few weeks. A cousin of mine Stefan, who was about twelve years my senior had earlier immigrated to Holland and had started his own business. He came to visit with me regularly. I begged him to get me out of there, and he did. I lived with Stefan until my parents and my sister got out of Germany, arriving via France in England. Upon their arrival they called Stefan, who took me to Hoek van Holland to cross the English Channel to Dover. When officials looked at my papers they claimed that my entry visa into England had expired, and if they don’t allow me to enter England they’re going to send me back to Germany. My cousin Stefan bribed the captain of this little boat and said, “That kid will never go back to Germany. He has permission to be in England; just his entry visa has expired because his parents got out so late.” I could not speak English at the time, since I was taught French in school by my famous Professor Berthold. I looked extremely young, even though I was sixteen, but I looked like twelve. After throwing up on the entire trip from Hoek van Holland to Dover the captain took me by the hand, put a little navy cap on me, and with my little suitcase, the Captain put me on a train destination London where my dad picked me up. It was a happy reunion. Together we moved from London to West Bromwich, Staffordshire, where my dad had a business friend who assisted us in starting a small toy business. This lasted barely one year, when the war broke out, and my Dad and I were interned, but not my mother nor my sister. We were arrested and taken for a couple of nights to a local jail. I shall never forgot this either. The arresting official, Police Commissioner Clark, apologized a thousand times for our arrest. Those were orders by the Home Office to arrest us and to be classified as Enemy Aliens. Not until many, many months or years later that our classification was changed from Enemy to Friendly aliens. After a couple of nights at the local jail we were transferred to an internment camp, first to Lingfield, a racetrack in London. We slept on the steps of the racetrack. Later on we were taken to Huyton internment camp near Liverpool. When we arrived at Huyton, one of my childhood friends, Lutz, tipped me off that a transport was leaving that night, either for Australia or for Canada with all the male youngsters. During the night I escaped from where I was stationed to join my dad, which saved me from going to Australia. We stayed in the internment camp until we were called up to the American Consulate under police guard, where we also met my sister and mother again and where we got our visas. We had to go back to the internment camp while my mother and my sister went back to West Bromwich, to pack up whatever belongings we had, and join us in Liverpool. We were released one night before our boat was to leave and stayed at a hotel that was bombed during the night by the Nazis. The bombs hit the front of the building and we were in the rear of the hotel. We were extremely fortunate. We left on a boat called the S.S. Samaria that had 500 British evacuees, kids that were going to Canada. We traveled in a convoy. The boat was hit by a mine, but fortunately didn’t sink, because it was equipped with a device called a Churchill Device that neutralized the mine and saved our boat. It was a very traumatic crossing. Everybody was seasick. My dad advised me not to undress at night, to stay prepared and ready for any emergency. It so happened when the mine hit the boat I was dressed and he had undressed to clean and shave. All of us had to go up on deck until they were sure that the boat was safe to continue our journey. We were part of a convoy with destroyers racing around since they were not sure if it was a mine or a torpedo. To make a long story short, we arrived safely in the United States on October 2, 1940. It was the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah, and my first trip was to go to synagogue to thank the Good Lord that I made it. At the entrance somebody stopped and asked me, “Where’s your ticket?” I said, “What do you mean ticket? I don’t need to get a ticket to go to synagogue to pray and thank God for my survival.” “Oh, you need a ticket.” But it was the synagogue of our congregation, Nuernberg, Furth, and Munich, and I responded by asking the guard to get my friend Eric Heilbronn, the rabbi’s son. He came out running. He was so excited that he ran right back into the synagogue up on the pulpit to tell the Rabbi (his Dad), “Papa, Papa, Franz ist da – Frank is here.” “Let him come in,” was Rabbi Heilbronn’s response. I could go in and see all my old friends – Walter Oppenheim, Hans Sachs, and Henry Kissinger, and so many others who were happy to see me again. Rosh Hashanah 1940 we were reunited again.

JB: Wow, what an amazing story. And then from there?

FH: Next step was for me to find a job. My first trip was to visit an outfit called “The Blue Card”, who assisted German refugees who immigrated to the United States. The Executive Director was a Dr. Richard Jung, who recognized me. He was a friend of my uncle, Dr. Arnold Frankenau. Since he was in no position to help me in finding a job he smiled and said, “Franz, here are ten dollars, and you don’t ever have to pay them back.” I have never forgotten this good deed. Years later I became very active with The Blue Card. At present I am still Vice-President of this wonderful organization, who honored me at a special dedication at the Heritage Museum in New York in 2005. I will talk about the wonderful work of The Blue Card a bit later on.

I had to find a job in 1940. I walked along Fifth Avenue, and was told that Fifth Avenue is the dividing line between east and west. There was a jewelry store called Richter’s. I went in and asked if they could use somebody. They said, “OK.” They gave me a job, ten dollars a week. Ok. I got the job, and had to take many jewelry items to the repair shops that were located in the 30s and in the 40s streets, to be repaired and then bring them back. At night Mr. Richter gave me deliveries to make on my way home. I walked up Fifth Avenue through Central Park, which was quite safe at the time. Since most of the deliveries were on the West Side I walked through Central Park to save the 0.5 subway fare. The first week was over; it was Friday. I went out during my lunch period to buy little gifts for my family. At night when I got my pay, I got my ten dollars, and Mr. Richter said, “Listen, I’ve got to let you go because you didn’t produce enough.” I worked my everything off and tried to please the Richter Jewelry Store and I was fired after one week. At least I had the good sense to say, “Mr. Michter, at least give me a recommendation. Say that I have worked here for six months. It will help me to find another job because I have only been in the country for two weeks.” So he gave me the recommendation that is still in my possession. The recommendation reads that I worked for six months for Richter’s and I was very satisfactory. So I arrived home with a recommendation but without a job.

The next job I took was for a carpet outfit in Brooklyn. I took the subway to Brooklyn, which for me was quite difficult. I was never very tall. I was never very strong. I had to schlep these carpets, and yes after one week I quit. I also got paid ten dollars. So basically, ten dollars was my life. I should have mentioned, when we arrived in the United States, we were allowed to bring in ten dollars per person, so it was ten dollars each for my father, for my mother, for my sister, and for me. When I went to The Blue Card I got ten dollars to tie me over. When I was fired from Richter’s I got ten dollars.

When I quit the carpet store I got paid ten dollars. So again I was out of a job. And I looked for some other jobs, and held all kinds of really crazy jobs. I wanted to get into hotel work since I had taken a course in cooking and baking. I went to the Waldorf-Astoria and I asked Monsieur Lugot, who was a Frenchman, if he could give me a job. He looked at me, and since his eyesight was rather poor out of one eye, and out of the other one I believe he could see nothing. He looked me over and said in his strong French accent, “Brrr. Monsieur Harris, at your age I was potato peeler. Don’t tell me you can cook. Get out of here. Come see me in a few years.”

I did come back and worked at the Waldorf after my army service. I’m going to talk about it later on during this interview.

JB: So after New York, you said a couple of years later you joined the army?

FH: Yes. I had a few other jobs. My dad unfortunately died in 1942, two years after we came to the States. I got a deferment from the army for one year. In 1943 I was drafted for the army. When they looked at me, since I looked so young, the sergeant said, “Come on, stop kidding. Send your brother.” I said, “No, I’m the one.” My name at that time still was Franz Siegmund Hess. I was accepted and really enjoyed the army. I was sent to Fort Dix, New Jersey, and from Fort Dix I was sent to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, to cooks and bakers school. The Military training was rather tough. It was one day basic training and one day working in the kitchen. At least I was able to get my foot in the kitchen, which was an advantage. This is what I wanted. As part of basic training we had a marathon race. From every company they had to send a couple of fellows to run the marathon. I certainly didn’t volunteer, but the sergeant said, “Hess, you’re the one that goes on the marathon.” I had not trained for such a race, nor was I in any shape for it. To make a long story short, I was ordered to run this marathon, even though I protested, since I had to work that night in the officers’ mess. The response from the sergeant was, “I don’t want any excuses. You’re going on the marathon.” But it wasn’t an excuse – the real marathon is usually 26 miles – this marathon was 14 miles, but it was incredible. When I finished all I wanted to do is lay down but they didn’t let me. They marched me because you’re not supposed to lie down. So I finished the marathon, swore to myself that I will never, ever volunteer, or will fight anyone that’s going to volunteer for me. I still worked that night in the officers’ mess.

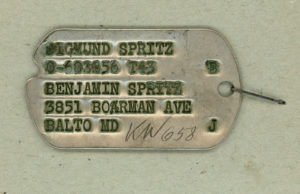

At another time I was once more tricked into a boxing tournament. I was a featherweight – and was opposed by a fellow from the South, who hated me because I was a Yankee. I tried to impress upon him that I’m not really a Yankee, I’m a refugee. But he was so strong he beat the hell out of me. And in between rounds my trainer said, “Go back and get him.” I said, “No, you go get him.” He didn’t and I took a heck of a beating, but I finished at least. There were only three or four rounds, whatever it was. But those were my special experiences at basic training. Upon completing basic training we were transferred to Camp Meade, MD. On a beautiful Fall day I was taken to Baltimore, Maryland, where I became an American citizen, a proud American citizen. When I was asked, “Do you want to change your name?” I said, “Yes, absolutely.” As I mentioned earlier, my name was Franz Siegmund Hess. So I requested a change from Franz to Frank. And Hess, I didn’t want anyone to ever question me if I’m related to Rudolph Hess, the Deputy Fuehrer. I asked to change it from Hess to Harris, but leave my middle initial S. Somehow when the papers came back the army messed this up and made Frank A. Harris out of it, so that’s when Franz Siegmund Hess became Frank A. Harris. From Camp Meade, Maryland, we went to Camp Patrick Henry in Virginia, and later on sailed on a troop transport to Casablanca. I was terribly seasick. They put me on a gun crew to look for submarines. I was completely useless for this assignment, because all I did was throw up for the entire period of my duty. This was a ship – the Empress of Scotland – that was used in peace time as a luxury liner to transport cruise passengers to the United States from England. During the war this luxury liner was used as a transport ship for soldiers. In place of 500 cruising passengers, we had 5000 seasick soldiers. It was a horrible trip. You couldn’t stand in line for food because the lines went all around the boat for any of the meals. I became quite seasick and was taken on sick call. The medic advised me “You need to eat.” My response, “I agree please get me something to eat.” He responded, “I can’t do that. You have to stand in line.” There was no way. I made a deal with one of the sailors from the Empress of Scotland. He sold me a dozen oranges for ten dollars – again here come the ten dollars – that saved me on the whole trip to Casablanca.

Being on the watch for submarines we had one tall fellow on the ship by the name of Walt Dropo. Walt Dropo was the tallest of the company and I was the shortest. One night on my submarine watch I felt that I had the urge again to throw up. Since I was on my way up on top deck I raced out to the bridge to make sure that nothing happened to any of the boys on the lower deck. All I could hear out of the dark, “I’m going to catch this son of a – that puked on my head and I’m going to throw him overboard.” And as much as I wanted to die when we got back to our sleep quarters, I did not tell him who the son of a gun was. At least not until we got to North Africa, when I confessed and he responded, “Frank you’re so smart that you didn’t tell me then – no telling what I would have done to you.” And I tried to explain that I went out of my way to avoid this mess. We remained good friends. Walt Dropo, after his discharge, as some of you might remember, was the first choice of the Chicago Bears, a top choice of a basketball team. His preference was baseball, and he became the famous first baseman for the Boston Red Sox. Later on he also played for the Detroit Tigers. After we were discharged I told my friends, “Oh, Walt Dropo’s a friend of mine.” ‘Oh, tell me another one’ was my friend’s’ response. So we attended a Yankee game, when they played the Detroit Tigers. I went down in between innings to the top of the dugout asking the guard, “Tell Walt Dropo to come over here.” He greeted me with a big grin, “Frankie Boy! So good to see you again.” So my friends were truly convinced that he was my army buddy.

JB: So from Casablanca you went where?

FH: From Casablanca we were transported to Oran with the 40 and 8, boxcars. They were called 40 and 8 because at one time they were used for transporting horses. We stayed in Oran for a few weeks, where we were taken frequently on long marches. I never forgot that we arrived in Oran during the rainy season in Africa. We were stationed on a hill where we had to pitch our tents. It was horrible because the rain ran right through our tents. But we survived this ordeal as well. By boat we were transported to Naples, staying in a replacement depot until I was assigned to the 2759th Combat Engineers. On our way north we bypassed Cassino and Anzio arriving in Leghorn (Livorno), where our outfit built bridges. On one of my days off I was able to visit Cassino. My childhood friend Eric Heilbronn – the one who got me into the synagogue without a ticket on my arrival in the States – was sent overseas about one month before me. Permit me to back up a little bit. Eric was in the military intelligence when his father the rabbi died. Eric attended his father’s funeral in New York, and on the way back to South Carolina he passed through Fayetteville, North Carolina. From Ft. Bragg I traveled to the railroad station to see and shake hands with Eric for the last time. He was taken out of the military intelligence, put in the infantry, and sent overseas. He only became a U.S. citizen overseas and was immediately sent into combat and killed the first day in combat. When I traveled to Cassino I looked at some of the graves, when somebody told me that there was a cemetery about ten kilometers further back. I hitchhiked there and saw literally thousands of graves. Cassino was a total disaster. The very first grave that I looked at was the grave of my friend Eric. I had to inform his mother, who at this time was only notified that he was missing in action, while he was already killed. I took pictures of his grave to send to his mom, who in many ways kind of adopted me, as the closest friend to her son. Our company left Leghorn, Italy on our way to France.

____________________

From Frank A. Harris Collection at Leo Baeck Institute Archives

My parents and I moved in together with the Jonas’s, Grete Herzberg, her mother Lilli Huber and an assortment of “Unter Mieters”. All of us had to earn a living, so I went to work the very first week as a delivery boy for Richter’s Jewelry store on 5th Avenue. The pay – $10.00 per week. The hours – 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM, 6 days a week. Length of employment, 1 week. Reason for dismissal-not lack of work, nor incompatibility, nor dishonesty – but that I was not productive enough for “that much money”.

And so I made the rounds from job to job – a “carpet schlepper” (the first job that I quit, because it was so strenuous) to chandelier assembler, to paper slipper § machine operator, to cook in a hotel. This was my preference, having had training in Munich. I also attended food trade high school at night in New York. All of us were most active in the Beth Hillel Synagogue’s youth group.

December 7, 1941 – my 19th birthday. During my party, the news came over the radio that Pearl Harbor had been attacked. All of us realized that, sooner or later, we would be inducted to serve our new Country.

On August 18, 1942 my father died at the age of 57, never really recovering from the traumatic experiences in the concentration camp K. 2 and the internment camp in England. So I became head of our household and chief provider at the ripe old age of 19.

My mother, who is now 84, is well and is now residing at the Isabella Home in Washington Heights, N.Y.C., along with many elderly friends from Nuernberg and Fuerth.

Barely 6 months after, I was drafted into the Army at Ft. Dix, took my basic training in Ft. Bragg, N.C. in the field artillery. Needless to point out, I was a model soldier, bubbling with enthusiasm and patriotism, while live bullets were shot over my head during the obstacle course. Some of my other accomplishments: a) I volunteered for the marathon – to get out of K.P. – and, upon completion, it took me 6 hours to catch my breath, b) I was in the boxing finals of featherweights against a Southerner who liked me personally, but hated all Yankees. He treated me as a Yankee in the ring. I lost by a TKO. The referee, also being a Yankee and having compassion for me, stopped the fight. (No Purple Heart for my gallant efforts?) Weekends I spent – meeting my friends, Henry K. [Henry Kissinger] (then a buck private) or Eric Heilbronn, both stationed in S.C. Eric I saw for the last time when he returned from his father’s funeral.

I became a citizen and changed my name from Franz Siegmund Hess to Frank A. Harris in Baltimore, Maryland in October 1943. This was one of the few quick moves I made in my life. I had intentions of changing my first name from Franz to Frank. The woman behind the desk asked about the 2nd name and as quickly as she asked, I answered “change it from Hess to Harris”. The Army goofed up the middle initial from S. to A. The real reaction came with my mother’s first letter, moaning over the fact that the “Stammbaum” will die.

While stationed at Ft. Meade (met my cousin Gus Osier there) my last stop in the U.S. was Camp Patrick Henry in Virginia, where the then Capt. Martin Herrmann was Supreme Commander of a colored outfit. They were also guarding prisoners. Since Martin was a linguist, he taught his men the German language (one of them stood in front of the doctor’s office instructing the prisoners

“Hosenturchen Zumaehen”.

I left the good old U.S. on Thanksgiving 1943 on the “Empress of Scotland”, a Cunard luxury liner designed for 500 passengers. It was my good fortune that the British consider an 0 as a Zero, so there were 500(0) (five thousand) passengers aboard. It was a never to be forgotten trip. I was so seasick, that the ship’s commander thought I was an excellent prospect for the gun crew – to look for submarines. I was on duty for two hours and off for four hours, and I never prayed so hard that some torpedo would get me out of my misery. Food was non-existent on the boat and the toilet facilities were air-conditioned -overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. I arrived in Casablanca unexpectedly one day early, in terrible physical and mental condition, but with full field pack, gas mask and M-l rifle, marching down the gangplank to music by an Army band, witnessed by a crowd of suspicious-looking Arabs. All I wanted was one square meal but I had to wait a full 24 hours for it. After a couple of weeks of fraternizing with the Moroccans, I took the 40 and 8 train to Oran (40 refers to 40 hours for 400 miles, 8 for 8 box cars). We slept in shifts, since there was little room to stand up, let alone lay down.

Oran is a very scenic city in French Algeria, but since every Arab looked at every American as a potential rapist or killer, it was totally unsafe to visit the city to engage in legitimate business transactions, such as selling your “Raleigh cigarettes” (they preferred Camels), we stayed around camp waiting for reassignment, which came shortly afterwards to Naples, Italy via Sicily. You know the old saying “See Naples and die” – but I didn’t want to die in Naples – I had to fight the Germans in Germany.

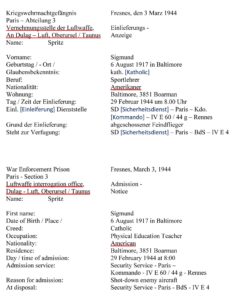

It was then that I learned of the death of my friend Eric Heilbronn and I found his grave near Cassino – also Pauli Harris (Hechinger), and the cruelty of this war struck home some more.

I was assigned to the 2759th Combat Engineers of Clark’s 5th Army (I shared a tent with Henry Landman, Lisa Oettinger’s husband), finishing in Livorno, Italy before moving on the Marseilles, France and Gen. Patton’s 7th Army. It was there that I met my cousin Al Moss (Mosbalner) again. During the winter of 1944, we moved through France into Germany and what a feeling to return as a soldier of the U.S. Army! I don’t know if I should say in retrospect that I was proud of what I had done in Germany. I do know that I was full of hate and fury and I have no regrets, after what the Nazis had done to my father and to many of my friends and family. The day I returned to Fuerth, my old friend Helmut Reissner came back from the K-2. I was in Ausburg when word came that the war in Europe was over. I left Germany, vowing that I would never return. I was shipped back to Marseilles, waiting to be assigned to the Pacific. The Atom bomb on Hiroshima finished the war there and exactly two years to the day from leaving the U.S., I embarked once again for the U.S. I arrived near Boston on December 5th, 1945 and headed for the first phone booth to call my mother and share with her my safe return, waiting for three hours to get through, expecting my mother’s voice, choking with emotion that I am alive. Her first words were “Franz, wo bist du denn?” [Franz, where are you?] and when I answered not in Germany nor in France, but in Boston and I will be home tomorrow, she didn’t say “I am so happy” but “Bring mir bitte ein seifewpulver und butter mit denn das ist sehr knapp hier” [“Please bring me some soap powder and butter, because that’s very scarce here”].

__________

“The very first grave that I looked at was the grave of my friend Eric. I had to inform his mother, who at this time was only notified that he was missing in action, while he was already killed. I took pictures of his grave to send to his mom, who in many ways kind of adopted me, as the closest friend to her son. Our company left Leghorn, Italy on our way to France.”

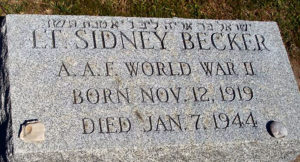

Here’s Frank Harris’ photograph of the grave of his friend Erich Heilbronn, near Cassino.

____________________

Like their son Erich, Rabbi Isak Heilbronn and his wife Erna Esther are buried at Cedar Park Cemetery in Paramus, New Jersey. This photo of their matzeva is by FindAGrave contributor dalya d.

Erich is buried alongside three other WW II Army casualties of German-Jewish ancestry. As seen in the photo below (also by dalya d) from left to right, these men are: T/5 John S. Weil, Pvt. Werner M. Strauss, PFC Paul M. Harris. Erich’s grave is at far right.

Biographical information about these three soldiers follows this image. Note that information about them appeared in Aufbau, and, American Jews in World War II.

.ת.נ.צ.ב.ה.

Tehé Nafshó Tzrurá Bitzrór Haḥayím

May his soul be bound up in the bond of everlasting life.

John Samuel Weil (Shmuel ben Dovid), T/5, 42078365, Purple Heart

Luxembourg, January 19, 1945

Born Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 9/5/10

Mrs. Maxine (“Mayme”) (Leibovitz) Weil (mother), 820 West End Ave., New York, 25, N.Y.

Sgt. Eric Lennart (step-brother)

Casualty List 3/8/45

Aufbau 2/2/45, 2/23/45

American Jews in World War II – 466

Werner Martin (Michael) Strauss (Mikhael ben Mordekhai), Pvt., 32898487, Purple Heart

30th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division

Italy, January 28, 1944

Mr. and Mrs. Max and Recha Strauss (parents), 880 West 180th St., New York, N.Y.

Born 3/11/24

Casualty List 3/17/44

Aufbau 3/3/44

American Jews in World War II – 457

Paul M. Harris (Pinkhas ben Yehuda), PFC, 32812529, Purple Heart

Italy, February 8, 1944

Dr. Otto M. Weller (friend), 676 Riverside Drive, New York, N.Y.

Mr. Leo Marlow [Manhardt] (uncle?), 44 Bath Road, Buxton, England

Born Munich, Germany, 3/3/24

Surname was originally “Hechinger“

Casualty List 11/19/44

Aufbau 8/11/44, 10/20/44

American Jews in World War II – 341

________________________________________

In closing, here’s a biography of Rabbi Heilbronn in English, followed by the original text in German, via RIJO Research. Note that the document was written in February of 1937…

Rabbi Dr. Isaak Heilbronn

(Born June 4, 1880 in Tann in the Rhön)

Nuremberg-Furth Israelite Community Paper No. 12 from February 1, 1937 (16th year), page 198

On the 25th official anniversary of Rabbi Dr. Isaak Heilbronn in the religious community in Nuremberg

More than half a century ago our celebrant saw the light of day in Tann in the Rhön; his education took him to the Jewish universities of Berlin and Breslau via the Göttingen grammar school; he received his license to practice as a rabbi in the Breslau seminary, and in Erlangen he received his doctorate with a thesis on “the mathematical and scientific views of Josef Salomo Delmedigo”.

In the year 1904 Dr. Heilbronn got his first job as a preacher in Spandau. The position was withdrawn for reasons of economy, because the community’s resources had been severely weakened due to the departure of the most efficient censite. [?] What was an isolated case in those happy times threatens to become almost a general phenomenon today, due to the emigration of so many fellow believers and the decline in assets and income of those who remain behind.

From Spandau, in 1912 Dr. Heilbronn committed to our religious community. That was a considerable promotion, which was also a testament to his excellent qualifications.

However, it was not pure and unclouded happiness that awaited him in Nuremberg. Based on the provisions of the old Bavarian state church law, which was still in force at the time, Rabbi Dr. Freudenthal, who had been in charge of the rabbinate since 1907, [that] Dr. Heilbronn should not be treated on an equal footing, but only as a “rabbinate substitute”.

That was a structural limitation of his functions, but it must be said that even with equality, it would not have been easy [for] Dr. Heilbronn to emerge next to next to Freudenthal whose life maxim was a downright fanatical will to work, a man whose insatiable creative will could not even break severe shocks to his health, who would have needed rest even in the time when his reduced physical strength was most urgent, had refused any discharge; added to this was the genteel reluctance that Dr. Heilbronn exercised with consideration for the higher years of life and service of his official colleague.

Through all of this, Dr. Heilbronn had a very limited field of activity; the shackles that were imposed on him left little room for the free development of the forces that slumbered in him; until Freudenthal’s resignation he could rarely speak from the pulpit to the congregation and only serve their members as pastors at weddings and funerals for short periods of time. The fact that he won the hearts of everyone very soon, the love and trust of the widest circles, speaks to a high degree for his rabbinical ability, for the warmth and humanity of his being that radiates from him. Dr. Heilbronn knew and always knows in his sermons to instruct his listeners by virtue of his great knowledge, to arouse them and to sooth them, he always finds words to fill the many people who are desperate today with God’s-trusting confidence. On the altar and on the bier, threads of solidarity weave from him to the happy and the mourning to create a kind of deeply human community.

A very special area of Heilbronn’s work has always been the education of young people; years ago, Dr. Heilbronn recognized with a clear view the paramount importance, especially in our religious community, of the training of religious youth who are not ashamed of their Judaism but are proud of it.

But the very own field of Dr. Heilbronn, towards which his innermost being urges him, is after all caring for the poor and depressed, a circle that is expanding almost from day to day in this difficult time. There is hardly a welfare organization in our community in which Dr. Heilbronn is not in a leading position or in any other influential position, and everywhere he is the warm, eloquent advocate for all who have to struggle hard for their existence.

Josef Salomo Delmedigo, who life chose Dr. Heilbronn chose as the subject of his doctoral dissertation, was a scholar of high grades, of unusual versatility, he was an astronomer, doctor, philosopher, mathematician, but he was certainly not a role model for his biographer in mathematics and even less in one whole other area.

A mathematician, if you mean an arithmetic artist in the usual sense, is not Dr. Heilbronn at all; at least not in welfare. He doesn’t calculate at all, but yields in the exuberance of his heart, or to put it more correctly, he would give if the writer of these lines didn’t give him a friendly stop every now and then. – But the difference in lifestyle is even greater. Delmedigo has not always expressed his true conviction – perhaps under the pressure of a frequently changing but always difficult to treat environment – he has not infrequently thrown diplomatic veils over his innermost thoughts. In this point, Dr. Heilbronn is just the opposite: his word is clear, his manner open, sincere and true. This truthfulness, like the mildness of his being, is also the cornerstone for the harmonious cooperation between him and the chairman of the community.

The cradle of our jubilee was shrouded in the harsh winds of the Rauen Rhön, but they did not give him any of their roughness on the path of life, his mind was and remained full of tender feelings, understanding everything human, open-minded everything human, his heart filled with kindness and love.

Anniversary articles usually close with friendly pictures for the next span of life, with beautiful prospects for a bright future; such words would be empty phrases, hollow idioms in this dark time that has come upon us all. On the contrary, the rabbi’s duties will weigh particularly heavily on our celebrant in the near future. From the pulpit he will have to try more than ever to instill courage and confidence in the souls of the oppressed parishioners. Welfare care will make ever greater demands with the growing need and ever more difficult problems will have to be mastered.

We therefore close with the wish: [that for] Dr. Heilbronn and his honored wife, the loyal and proven helper in works of charity, may strengths be retained for many years to help overcome the endless difficulties that surround us and await us. [Ludwig] Rosenzweig

On February 10, 1939, the Heilbronn family emigrated to New York via London, where Dr. Heilbronn together with the former Munich rabbi Dr. Leo Baerwald founded a community for emigrants from Germany, in which many people from Nuremberg, Munich and Fürth became members and found a spiritual home. His son Erich died as an American soldier in World War II.

____________________

Rabbiner Dr. Isaak Heilbronn

(geb. 4.6.1880 in Tann i.d. Rhön)

Nürnberg-Fürther Israelitisches Gemeindeblatt Nr. 12 vom 1. Februar 1937 (16. Jg.), S. 198f.:

Zum 25jährigen Amts-Jubiläum des Rabbiners Dr. Isaak Heilbronn in der Kultusgemeinde Nürnberg

Vor mehr als einem halben Jahrhundert erblickte unser Jubilar in Tann in der Rhön das Licht der Welt; sein Bildungsgang führte ihn über das Göttinger Gymnasium auf die jüdischen Hochschulen von Berlin und Breslau; im Breslauer Seminar erhielt er seine Approbation als Rabbiner und in Erlangen promovierte er mit einer Arbeit über “die mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Anschauungen des Josef Salomo Delmedigo” zum Doktor.

Im Jahre 1904 erhielt Dr. Heilbronn seine erste Anstellung und zwar als Prediger in Spandau. Die Stelle wurde aus Sparsamkeitsgründen eingezogen, weil die Mittel der Gemeinde wegen Wegzugs des leitungsfähigsten Censiten sehr geschwächt worden waren. Was in jenen glücklichen Zeiten ein Einzelfall war, droht heute durch die Auswanderung so vieler Glaubensgenossen und durch den Vermögens- und Einkommensverfall der Zurückbleibenden beinahe eine Allgemeinerscheinung zu werden.

Von Spandau wurde Dr. Heilbronn im Jahre 1912 für unsere Kultusgemeinde verpflichtet. Das war ein beträchtlicher Aufstieg, der zugleich Zeugnis für seine ausgezeichnete Qualifikation war.

Ein reines und ungetrübtes Glück war es jedoch nicht, das ihn in Nürnberg erwartete. Auf Grund der Bestimmungen des damals noch geltenden alten bayerischen Staatskirchenrechtes konnte Dr. Heilbronn Herrn Rabbiner Dr. Freudenthal, der seit 1907 das Rabbinat betreute, nicht gleichgestellt, sondern nur als “Rabbinatssubstitut” angestellt werden.

Das war schon eine strukturelle Einschränkung seiner Funktionen, aber es muss gesagt werden, dass es auch bei einer Gleichstellung Dr. Heilbronn nicht leicht geworden wäre, neben einem Freudenthal, dessen Lebensmaxime ein geradezu fanatischer Arbeitswille war, aufzukommen, neben einem Manne, dessen unstillbaren Schaffenswillen nicht einmal schwere gesundheitliche Erschütterungen zu brechen vermochten, der auch in der Zeit, in der seine geminderten körperlichen Kräfte dringendst der Schonung bedurft hätten, jede Entlastung abgelehnt hat; dazu kam noch die vornehme Zurückhaltung, die Dr. Heilbronn mit Rücksicht auf die höheren Lebens- und Dienstjahre seines Amtskollegen übte.

Durch all das hatte Dr. Heilbronn ein sehr eingeschränktes Wirkungsfeld, die Fesseln, die ihm auferlegt waren, liessen der freien Entfaltung der Kräfte, die in ihm schlummerten, wenig Spielraum; er konnte bis zum Rücktritt Dr. Freudenthals nur selten von der Kanzel zur Gemeinde sprechen und nur während kurzer Zeiträume ihren Mitgliedern bei Trauungen und Bestattungen Seelsorger sein. Dass er sich trotzdem sehr bald die Herzen aller gewann, die Liebe und das Vertrauen weitester Kreise errang, spricht in hohem Mass für sein rabbinisches Können, für die Wärme und Menschlichkeit seines Wesens, die von ihm ausstrahlt. Dr. Heilbronn wusste und weiss immer in seinen Predigten seine Zuhörer kraft seines grossen Wissens zu belehren, aufzurütteln und auch zu beruhigen, er findet immer wieder Worte, um die vielen Menschen, die heute am Verzagen sind, mit gottvertrauender Zuversicht zu erfüllen. Am Traualtar wie an der Bahre weben sich von ihm zu den Frohen wie zu den Trauernden Fäden der Verbundenheit zu einer Art tiefmenschlicher Gemeinschaft.

Ein ganz besonderes Gebiet Heilbronnschen Wirkens war von jeher die Erziehung der Jugend; Dr. Heilbronn hat schon vor Jahren mit klarem Blick erkannt, welch überragende Bedeutung gerade in unserer Glaubensgemeinschaft der Heranbildung einer religiösen Jugend, die sich ihres Judentums nicht schämt, sondern stolz auf es ist, zukommt.

Aber das ureigenste Feld Dr. Heilbronns, auf das ihn sein innerstes Wesen hindrängt, ist doch die Fürsorge für die Armen und Bedrückten, ein Kreis, der sich in dieser schweren Zeit fast von Tag zu Tag erweitert. Es gibt in unserer Gemeinde kaum eine Wohlfahrtsorganisation, in der Dr. Heilbronn nicht an leitender oder sonstiger einflussreicher Stelle steht, und überall ist er der warme, beredte Fürsprecher für alle, die hart um ihr Dasein ringen müssen.

Josef Salomo Delmedigo, dessen Leben sich Dr. Heilbronn zum Gegenstand seiner Doktor-Dissertation gewählt hat, war ein Gelehrter von hohen Graden, von ungewöhnlicher Vielseitigkeit, er war Astronom, Mediziner, Philosoph, Mathematiker, aber ein Vorbild für seinen Biographen war er bestimmt nicht in der Mathematik und noch weniger auf einem ganz anderen Gebiet.

Ein Mathematiker, wenn man darunter einen Rechenkünstler im üblichen Sinne versteht, ist Dr. Heilbronn ganz und gar nicht; wenigstens nicht in der Wohlfahrt. Da rechnet er überhaupt nicht, sondern ergibt im Überschwang seines Herzens, richtiger gesagt, er würde geben, wenn ihm der Schreiber dieser Zeilen nicht mitunter ein freundschaftliches Stop entgegenhalten würde. – Noch grösser aber ist der Unterschied in der Lebensführung. Delmedigo hat nicht immer – vielleicht unter dem Druck einer häufig wechselnden, aber stets schwer zu behandelnden Umwelt – seine wahre Überzeugung zum Ausdruck gebracht, er hat nicht selten diplomatische Schleier über seine innerste Gedankenwelt gebreitet. In diesem Punkte verkörpert Dr. Heilbronn das gerade Gegenteil: sein Wort ist klar, seine Art offen, aufrichtig und wahr. Diese Wahrhaftigkeit, wie die Milde seines Wesens, sind auch die Grundpfeiler für das harmonische Zusammenwirken zwischen ihm und dem Vorsitzenden der Gemeinde.

Die Wiege unseres Jubilars war umwittert von den harten Winden der Rauen Rhön, aber sie haben ihm von ihrer Rauheit nichts mit auf den Lebensweg gegeben, sein Gemüt war und blieb voll zartester Empfindung, alles Menschliche verstehend, allem Menschlichen aufgeschlossen, sein Herz erfüllt von Güte und Liebe.

Jubiläumsartikel schliessen gewöhnlich mit freundlichen Bildern für die nächste Lebensspanne, mit schönen Ausblicken auf eine frohe Zukunft; solche Worte wären in dieser düsteren Zeit, die über uns alle gekommen ist, leere Phrasen, hohle Redensarten. Im Gegenteil, die Pflichten des Rabbiners werden in der nächsten Zeit besonders schwer auf unserem Jubilar lasten. Von der Kanzel herab wird er mehr wie je versuchen müssen, Mut und Lebenszuversicht in die Seelen der bedrückten Gemeindemitglieder zu träufeln. Die Wohlfahrtspflege wird mit der wachsenden Not immer grössere Anforderungen stellen und immer schwierigere Probleme werden zu meistern sein.

Wir schliessen daher mit dem Wunsche: mögen Dr. Heilbronn und seiner verehrten Gemahlin, der getreuen und bewährten Helferin in den Werken der Nächstenliebe, noch lange Jahre die Kräfte erhalten bleiben, um die unendlichen Schwierigkeiten, die uns umgeben und unserer harren, überwinden zu helfen. [Ludwig] Rosenzweig

Am 10.2.1939 wanderte die Familie Heilbronn über London nach New York aus, wo Dr. Heilbronn zusammen mit dem ehemaligen Münchner Rabbiner Dr. Leo Baerwald eine Gemeinde für die Emigranten aus Deutschland gründete, in der viele Menschen aus Nürnberg, München und Fürth Mitglieder wurden und eine seelische Heimat fanden. Sein Sohn Erich fiel als amerikanischer Soldat im Zweiten Weltkrieg.

Reference (Just One)

Dublin, Louis I., and Kohs, Samuel C., American Jews in World War II – The Story of 550,000 Fighters for Freedom, The Dial Press, New York, N.Y., 1947.

Acknowledgement

My deep thanks to Bastiaan van der Velden for enabling me to present a fuller historical picture of Erich Heilbronn and his family.