Then, one evening, he sat in a train travelling westward

and felt as if he was not making this journey of his own free will.

Things had turned out as they always had in his life,

as indeed much that is important does in the lives of others,

who are deceived by the more noisy and deliberate nature of their activities

into believing that an element of self-determination governs their decisions and transactions.

However, they forget that over and above their own brisk exertions lies the hand of fate.

(Joseph Roth, Flight Without End, 1927)

______________________________

_______________

______________________________

If a tree falls in a forest, does anyone hear it?

And if the forest should fall, will it be remembered?

The Great War ended over one hundred years ago, though its political, cultural, and perhaps even theological impact (the latter in a secular guise) have persisted to the present, and doubtless will continue – even if in muted and unrecognized form – into the future. Typical of transformative civilizational events, the war has inspired and generated an incalculably expansive body of literature – fiction; personal memoirs; poetry; unpublished manuscripts and personal correspondence; historical studies; archival records – the volume of which is an indirect measure of the scope of its effects.

Such for “the world” in general, and as much for the Jewish people as well. As described by David Vital in his magisterial overview of European Jewish history A People Part – A Political History of the Jews in Europe, 1789-1939, during an era of confident if not exuberant nationalistic feeling among both the Allied and Axis powers, the war provided the opportunity for the Jews of Europe and the United States (even to some extent among the Jews of Imperial Russia) to manifest – no more or less than other peoples – sincerely felt feelings of patriotism undergirded by an ethos of acculturation and assimilation.

Regardless and perhaps in spite of the war’s outcome, in terms of trauma and human suffering, what’s particularly notable about the postwar era is the profusion of compilations of historical information concerning Jewish military service, created by individuals, Jewish communities, and organizations of Jewish veterans, within countries that comprised both the Allies and Central Powers. Among the Allies, such compilations covered military service by Jews in the British Commonwealth (the content of which overlapped onto a monograph about the military service of Jews in both Australia and New Zealand), Bulgaria, France, Italy, and Serbia. No such works were created about the military service of the Jews of the United States (I rectified that astonishing absence a few years ago; see here and here), or, to the best of my knowledge, Belgium, Greece, Romania, and Russia.

Of the four countries that comprised the Central Powers (the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Bulgaria, Germany, and the Ottoman Empire) parallel books about Jewish military service were limited to Bulgaria and Germany.

And in this, we find a forest of memory that is fallen and long-forgotten: That of the Empire of Austria-Hungary, the multi-national state formed from an alliance between those two nations that was formed in 1867 and survived until the 31st of October, 1918. According to Martin Gilbert’s Atlas of Jewish History, the Jewish military contribution in the Austro-Hungarian Empire – 320,000 in service, with 40,000 dead – far exceeded that of Imperial Germany, or, that of the British Commonwealth, France, and the United States combined. Military service and casualties among the Jews of the Empire were second in gravity only to the terrible military toll incurred by the Jews of Imperial Russia, from whom of the 650,000 in military service, 100,000 lost their lives.

And with this; and in spite of this; and probably because of this: the Empire’s dissolution, and I’d think its social and cultural effects on the Jews of the newly autonomous Austria, and, Hungary; the nominal fact that the Empire no longer existed, no compilation (to the best of my knowledge) about the military service of Austro-Hungarian Jewry was ever created, or would be created. The following video places this in perspective…

Jewish Soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian Army (August 30, 2013), at Centropa Cinema

But, even in 2023 and beyond, there might be a way to created such a record. It would be approximate. It would be incomplete. It would be open-ended. But, a nominal record of Jewish military service in the Austro-Hungarian Empire it would nonetheless be. This would be via the newspaper Dr. Bloch’s Oesterreichische Wochenschrift, created (as implied by the title!) by Rabbi Joseph Samuel Bloch.

As part of the Digital Collection (Digitale Sammlungen) of Goethe University of Frankfurt am Main, this newspaper, “…was originally founded with the intention of using an offensive organ to put the enemies of the Jews in their place.” “The newspaper, under its editor of many years, was primarily directed against the influential, openly anti-Semitic Christian-social movement around Karl Lueger. Another focus of the “Österreichische Wochenschrift”, which became the official organ of the Viennese religious community soon after its founding, was the often very sharp criticism of Zionism, whose colonization plans the orthodox scholar Bloch supported in principle, but whose leaders he accused of domestic political misconduct in the implementation accused of their program.” Published weekly between 1884 and 1920, the periodical is available through the University’s Judaica Section under the Compact Memory heading, here, the University’s holdings encompassing the years 1891 (Volume 8 – January 2, 1891) through 1920 (Volume 37 – February 20, 1920).

Fortunately, I had the time to create such a record. Or, more aptly phrased, I made the time to create such a record. As described in my post about identifying Jewish military casualties of the First World War, during the early 2000s, while in the corporate world, I encountered a situation that was – by all stereotypical standards of “cubicle-land” – entirely unexpected. Rather then being utterly deluged with work, I found myself in the opposite situation: For many months, I simply had nothing to do. And so, while perusing the Internet for websites pertaining to Jewish and military history, I discovered Goethe University’s Digital Collection, and there, along with Aufbau, Dr. Bloch’s Oesterreichische Wochenschrift. Realizing that the opportunity would not again arise, I reviewed each and every issue of the newspaper published between August, 1914, and December, 1918, in an effort to identify all (seriously!) news items, articles, essays, and other items published during that time interval pertaining to Jewish military service in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, as well as in Germany, or even the armed forces of the Allies.

In this endeavor, I discovered over such 3,500 items. A year-by-year tabulation follows below:

1914: 353

1915: 1162

1916: 822

1917: 812

1918: 420

Total: 3,569

______________________________

_______________

______________________________

But what about Rabbi Joseph Bloch the person; himself? The Wikipedia record for Rabbi Bloch, largely based on the 1901-1906 entry in The Jewish Encyclopedia, provides an overview of his family background, early life, rabbinical positions, and subsequent career in journalism and politics – the latter geographically centered in Vienna – particularly in terms of his defense of Austrian Jews against antisemitism. However, this account makes only a brief reference to Dr. Bloch’s Oesterreichische Wochenschrift.

Robert Wistrich’s 1986 Jewish History article “Zionism and Its Religious Critics in fine-de-siècle Vienna”, provides a wider overview of the creation of the Rabbi’s newspaper, his initially positive, then ambiguous, and ultimately (ironically!) negative attitude towards political Zionism. The latter seems seems to have sprung from the theological unacceptability of human and thus purely secular – versus Divine and Messianic – efforts to recreate a Jewish nation-state, and quite astonishingly, for one who had so confidently and successfully defended the Jews against antisemitic calumnies, fear about the potential social and political repercussions of Zionism upon the Jews of Austria, and perhaps by implication (?) Europe and beyond. As noted by Dr. Wistrich, “For Rabbi Bloch, the Jews had to defend their ethno-religious interests while remaining a supranational, mediating element within the multi-national State, but they should on no account be defined as a separate political nation.” In terms of the clash between Rabbi Bloch and Theodore Herzl, specifically as presented in Dr. Wistrich’s paper, in light of political developments in Israel in 2023, Dr. Bloch was prescient about the implications of “defining Jewry as a secular political nation”. For more about this deeply fraught topic, you might want to read Israel Eldad’s The Jewish Revolution – Jewish Statehood, and, David Vital’s The Origins of Zionism.

And so, from Dr. Wistrich’s article…

The Galician-born Rabbi Joseph Samuel Bloch, perhaps the foremost defender of Jewish rights in the Austrian Reichsrat at the end of the 19th century, in his own maverick way reflected this Orthodox world-view while combining it with a pugnacious political militancy and astute sense of public relations. Bloch came from the Austrian provinces to the Viennese industrial suburb of Florisdorf at the end of 1870s and from the outset challenged the social and political philosophy of the Viennese liberal establishment. He won popularity among working-class Gentiles by lecturing to them about the advanced social doctrines in the Hebrew Bible and respect among traditional Jews by his vigorous defense of the Talmud. Above all, he became a popular Jewish hero and parliamentary candidate through his vitriolic onslaught on the Catholic anti-Semite, Canon August Rohling, whose scurrilous Talmudjude had left the official Viennese Jewish leadership, both lay and religious, floundering in impotent silence and embarrassment.

Like many other Orthodox Galician Jews, Rabbi Bloch aligned himself politically with the Polish Club in the Austrian parliament and with Count Taafe’s [Eduard Taaffe, 11th Viscount Taaffe] conservative ruling coalition. A Habsburg dynastic patriot, he constantly warned the Austrian Jews to remain neutral in the nationalities’ conflict and on no account to identify themselves with German, Czech, Magyar or any other form of national chauvinism. At the same time, militant Jewish self-defense was necessary to counteract the threat of organized political anti-Semitism – a point in which Bloch differed from other Orthodox rabbis as well as from most liberal establishment Jews. Indeed, in his aggressively political stance and with his proud, self-assertive Jewish ethnic consciousness, Rabbi Bloch in the early 1880s seemed closer to the students of Kadimah than any other prominent Jewish public figure in Austria. The journal which he founded – the Oesterreichische Wochenschrift – for all its conservative, Austrian dynastic loyalism, was also infused with a Jewish national spirit that seemed radical and even populist at the time. Not surprisingly, Rabbi Bloch was a guest of honor in December 1884 at the Maccabean dinner held by Kadimah students, though significantly he warned against misinterpreting the message of the Maccabees in a nationalistic, warlike spirit. But he shared with the early Zionists the same consciousness of the common fate of the Jews, the same determination to fight against apostasy and self-hatred within Jewish ranks, the same rejection of assimilation and reassertion of Jewish honor and self-respect.

Yet Rabbi Bloch’s attitude to the political Zionism which emerged in the 1890s was clearly ambiguous. He had always been sympathetic, like Spitzer and Güdemann, to the moderated, practical colonization efforts of the Hovevei Zion. In 1896 he had even encouraged Herzl’s first efforts to publicize his Zionist ideas and introduced him to the Austrian finance minister, Leon Ritter von Bilinski, a Catholic of Jewish origin and a leading member of the Polish Club. Like Bilinski, Bloch had been impressed by Herzl’s magnetic personality and by his vision and political insight, but remained highly skeptical about his nationalist ideology and its long-term implications for Jewry. He had been pleasantly surprised (like the Chief Rabbi of Vienna, Moritz Güdemann) that a witty feuilletonist and literary editor of the Neue Freie Presse should suddenly become passionately interested in Jewish affairs. At a private reading of what would later become known as Der Judenstaat, Rabbi Bloch had moreover liked its literary style and was relieved that there was no mention of Palestine as the future location of the Jewish State.

When Herzl subsequently evoked the historic Jewish claim to Palestine, Bloch’s reaction was, however, sharply disapproving. Recalling the disastrous episode of the “false messiah,” Shabbetai Zevi, Rabbi Bloch advised Herzl of the history of the Holy Land and its exposed geo-political position. He also lent to Herzl two addresses on the Talmud given by Dr. Jellinek [Rabbi Adolf Jellinek] nearly thirty years earlier, which reflected the prophetic supra-national spirit of Judaism and which warned against attempts to rebuild the Temple. He even recounted to Herzl the historic encounter of 1882 in Vienna between Jellinek and Leo Pinsker. Only this time he sided with the recently deceased liberal rabbi, despite the fact that Jellinek had been his bête noire for many years and had helped to block his appointment to the Chair of Hebrew Antiquities at the University of Vienna. Rabbi Bloch explained to Herzl that though residence in the land was considered a great virtue in the Talmud, Judaism forbade a mass return to Palestine and a restoration of the Jewish State before the advent of the Messiah.

Bloch, like his close friend and ally, Rabbi Moritz Güdemann, favored a philanthropic Zionism along the lines of the agricultural settlements encouraged by Sir Moses Montefiore, Baron Maurice de Hirsch and Baron Edmond de Rothschild. But he objected to Herzl’s insistence on defining Jewry as a secular political nation, holding the view that this would undoubtedly endanger the status of Jews in Austria at a time of rampant anti-Semitic propaganda calling for their disenfranchisement. For his part, Herzl was arrogantly dismissive of Bloch’s “medieval, theological tussle with the anti-Semites,” which to his mind suffered from all the familiar illusions of Jewish self-defense activity. When Herzl founded Die Welt, a rival journal to Dr. Bloch’s well-established Wochenschrift, relations deteriorated still further. By the turn of the century, Bloch’s weekly was publishing articles sharply critical of Herzl’s Regierungs-Zionismus, his reliance on high diplomacy, and his ignorance of Jewish history and of the Jewish masses in Russia and Galicia. The official line of the weekly was to support a practical emigration policy that included Palestine as one of its goals but to reject the diplomatic “Kunststücken” and utopian fantasies behind the idea of the Jewish State.

After Herzl’s death in 1904, the Austrian Zionists began to engage more openly in Landespolitik and the rivalry between them and the Austrian Israelite Union – which Rabbi Bloch had done so much to found in 1886 – grew more intense. Bloch resented Zionist politicking in Austrian parliamentary elections, though he chose to see the election of four Jewish national deputies to the Reichsrat in 1907 as a victory for his own credo of vigorous Jewish political representation. For Rabbi Bloch, the Jews had to defend their ethno-religious interests while remaining a supranational, mediating element within the multi-national State, but they should on no account be defined as a separate political nation.

Bloch’s antipathy to political Zionism appears to have grown with the years. According to one source – though the authenticity of the claim has been challenged – he received some 250 negative written opinions on Herzlian Zionism from prominent Orthodox rabbis in the period between 1897 and 1913. The successes of the Zionist movement after 1917 in the sphere of international diplomacy did not diminish his conviction that political Zionism was a great danger to the Jews, that it was playing with fire and would only serve to inflame anti-Semitism. Indeed, in a letter to his namesake, Rabbi Chaim Bloch, shortly before his death at the end of 1923, he urged the latter to work for the creation of an “anti-nationalist movement within Jewry” to contain the threat posed by political Zionism.

Here’s the front page of Dr. Bloch’s Oesterreichische Wochenschrift for the issue of July 7, 1916, symbolically chosen for this post because of the connotation of that date with the opening week of the Battle of the Somme. (Not that there’s anything about that battle in this issue!) There’s no need to display the first page of any other issue of the paper published during the Great War, because the cover design was identical from year to year to year throughout that time interval.

______________________________

_______________

______________________________

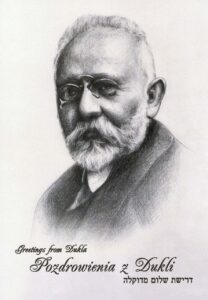

“Rabbi Joseph Samuel Bloch – born in Dukla 20.11.1850”

This postcard image of Rabbi Bloch from KehilaLinks at JewishGen is described by Jeffrey Alexander and Philip Ross as being one of ten postcards published by Sztetl Dukla in 2015 showing portraits of Jews from Dukla. Taken from period photographs, the postcards’ line drawings were created by Krakow artist Wojciech Gryszkiewicz, with postcard design by Judith Stola.

Here’s the original photograph upon which the Sztetl Dukla postcard is based. From the Wikipedia record for Rabbi Bloch, the image, by an unknown photographer, is described as being from Erinnerungen aus meinem Leben (Vienna & Leipzig: R. Löwit, 1922) by Dr. Joseph S. Bloch”.

As for Dukla, the small town is described by Alexander and Ross at JewishGen as being, “…located in the southern part of Poland, at latitude 49° 34´, longitude 21° 41´. Although the town began in Poland, it was part of Galicia (an Imperial Province of the Austrian Empire) from 1776 to 1919. Today the town of Dukla is found in Poland’s Supcarpathian Volvodeship [province], within the powiat [county or district] of Krosno and is part of the gmina [municipality or commune] of Dukla consisting of the Dukla town and villages surrounding it. At the end of the 2020 calendar year, the town of Dukla had a population 2,005 people.”

______________________________

_______________

______________________________

As noted above, my survey of Dr. Bloch’s Oesterreichische Wochenschrift for news items, articles, essays, and other items about Jewish military service in the Austro-Hungarian armed forces identified over such 3,500 items published from August of 1914 through November of 1918. Being that the translation of these items would be an effort gargantuan – far more in terms of time than effort – my records for these items are limited to their titles, and, bibliographical information about the issue in which they were published. So continuing with the theme of the opening of the Battle of the Somme in July of 1916, here are relevant news items for that month, listed under the date of publication. The front-page news item is in boldface.

July 7, 1916 (Issue 27)

Human Race’s Latest Rifts – By Privy Councilor Ed. King in Bonn – II

War Decorations of Jewish Officers and Soldiers

Award of a Jewish MP

The False Russian Reports (Approved by the War Press Office.)

Doubly Heroic

Medical Officer Tobias Weinstock

Silver Medal First Class for Bravery

More Awards

The Heir to the Field House of Worship

Good and Blood

Jewish Families in the Field

Awards of Jewish Warriors with the Iron Cross

Field Post Letters

Pesach in Tschita and Pjetchanska (see below…)

Internment of an Austrian Inventor in England

Prof. Adolf Frank, Founder of the Potash Industry, Died

Vienna Official Gazette of June 21

July 14, 1916 (Issue 28)

Celtic-Aryan “Cultural Work” – On the Second Air Bombardment of Karlsruhe on June 22, 1916

War Decorations of Jewish Officers and Soldiers

The Father with Three Sons

The Grossman Family

Appointment of a Field Rabbi

Jewish Families in the Field

More Awards

Jewish Baggage Ahead! – An Episode from the Battles before Luek

Honor of a Fallen War Volunteer

Awards of Jewish Warriors with the Iron Cross

The Blood Sacrifices of the Russian Jews

Heroic Death of a Jewish-Polish Legionary

Honored after Death

Fallen Before the Enemy

July 21, 1916 (Issue 29)

A Reminder for the Heern Prosecutor

War Decorations of Jewish Officers and Soldiers

Colonel v. Racy About the Jewish Soldiers

More Awards

Fallen in the Field of Honor

Warfare Awards

Red Cross Awards

Promotion

Commendatory Recognitions

Heroic Death

List of Officers and Men Buried in Vienna from May 15 to July

Honored after Death

Fallen Before the Enemy

Remedy Against Profiteering Traders in Old Times

Awards of Jewish Warriors with the Iron Cross

A Letter from Dr. Gaster

July 28, 1916 (Issue 30)

The “Plutocracy” as the Cause of the World War (A Revelation of the “Reichspost”) – II

War Decorations of Jewish Officers and Soldiers

High Distinction of a Field Rabbi

Jewish Families in the Field

Lieutenant Emmerich Biro

Awarded the Silver Medal for Bravery

Recent Award

More Awards

Fallen in the Field of Honor

Red Cross Award

The Father of Seven Sons

Imperial Gift

Honored after Death

Well Deserved Recognition

Awards of Jewish Warriors with the Iron Cross

Fallen Jewish Heroes in the Jewish Cemetery of Ungvar

A Jew on the Merchant Submersible “Deutschland”

Gobineau and Chamberlain

Cultural Work in the East

Secretary of State Helfferich in a Jewish Cheder School

A Tour of the Chief Rabbi in Strassburg

Women as Funeral Orators

______________________________

_______________

______________________________

Here are four random news items from Dr. Bloch’s Oesterreichische Wochenschrift, one for 1915 and 1916, and two for 1917. They’re presented such that the English-language translation appears first, followed by a verbatim transcript of the article in German (in blue), then an image of the article as it appeared in the newspaper, concluding with an image of the entire page in which the news item appeared. I’ve also included three sort-of-randomly-chosen images – two individual pictures and a group photo – of Jewish soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian military, to lend a visual “flavor” to the text.

______________________________

_______________

______________________________

Just a photograph: A Jewish soldier in the Austro-Hungarian army:

“Maximilian Rosenbluth, soldier and baker of Dukla.”

Also from KehilaLinks at JewishGen; like the portrait of Rabbi Bloch, this image is one of Sztetl Dukla’s 2015 ten postcard set by Wojciech Gryszkiewicz and Judith Stola.

______________________________

_______________

______________________________

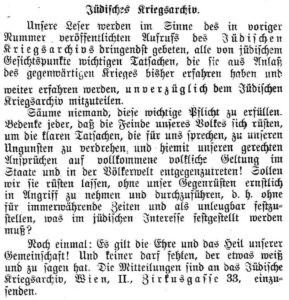

Year 1915

This article, from 1915, follows a theme seen in The Jewish Chronicle during the same time-frame: The plan to create a historical record of Jewish military service. Perhaps less out of innate pride and the natural need to record the historical experience of the Jews per se, than the anticipated need to refute antisemitic calumny in the future. This assumes, of course, that antisemitism – Jewhatred – can be refuted by facts, logic, and reason.

Jewish War Archive

January 29, 1915

Issue Number 5, Page 85 (Issue page 9)

Our readers are urged, in the sense of the publication of the Jewish War Archive, published in the previous issue, to inform the Jewish War Archive without delay of all facts of Jewish legitimacy, which they have so far experienced and will continue to experience on the occasion of the present war.

Do not frustrate fulfilling this important duty. Remember everyone that the enemies of our people are preparing themselves to turn the clear facts that speak for us to our detriment, and thus to oppose our just claims to perfect national validity in the state and in the peoples! Shall we equip them without seriously attacking and executing our countermeasures, without establishing for everlasting times and as undeniable what needs to be established in the Jewish interest?

Once upon a time: the honor and the salvation of our community are important! And no one may fail, who knows something and has something to say. The notifications are to be sent to the Jewish War Archive, Vienna, II., Zirkusgasse 33.

Judisches Kriegsarchiv

Unsere Leser werden im Sinne des in voriger Nummer veröffentlichen Aufrufs des Jüdischen Kriegsarchivs dringendst gebeten, alle von jüdischen Gestchtspunkte wichtigen Tatsachen, die sie aus Anlass des gegenwärtigen Krieges bisher erfahren haben und weiter erfahren werden, unverzüglich dem Jüdischen Kriegsarchiv mitzuteilen.

Säume niemand, diese wichtige Pflicht zu erfüllen. Bedenke jeder, dass die Feinde unseres Volkes sich rüsten, um die klaren Tatsachen, die für uns sprechen, zu unseren Ungunsten zu verbrehen, und hiemit unseren gerechten Ansprüchen auf vollkommene volkliche Geltung im Staate und in der Völkerwelt entgegenzutreten! Sollen wir sie rüsten lassen, ohne unser Gegenrüsten ernstlich in Angriff zu nehmen und durchzuführen, d.h. ohne für immerwährende Zeiten und als unleugbar festzustellen, was im jüdischen Interesse festgestellt warden muss?

Noch einmal: Es gilt die Ehre und das Heil unserer Gemeinschaft! Und keiner darf fehten, der etwas weiss und zu sagen hat. Die Mitteilungen sind an das Jüdische Kriegsarchiv, Wien, II., Zirkusgasse 33, einzusenden.

______________________________

_______________

______________________________

Year 1916

This article is fascinating, moving, and inspiring. It’s a transcript of a letter sent to a family somewhere in Austria-Hungary by their son, then somewhere in the vicinity of “Tschita” (Chita), a city in south central Russia east of Lake Baikal. The writer describes having attended the second Pesach Seder of 1916, in the temple in Chita, a central clue identifying the city being mention of Ingodinskaya Street, on which the schul was (still is) located. There are absolutely no specifics in the letter about the author. But, comments in the text strongly suggest that he was a prisoner of war in Russian captivity, the most obvious being that his attendance at the Seder with three companions occurred while under guard of a bayonet-wielding Russian soldier, the latter who it seems remained at a penal house – with a number of other Russian guards? – while the writer and his companions attended the Seder, in the schul.

As you can see in the images below, the schul is very much still standing on Ingodinskaya Street, albeit it hasn’t been a schul for many decades.

Pesach in Tschita and Pjetchanska

July 7, 1916

Issue Number 27, Page 451 (Issue page 7)

Pjetchanska, Wednesday, June 19.

April (Pesach), 2nd day, evening.

Dear parents and sister!

Despite many difficulties to be overcome, I can confidently apply the words of the Haggadah to yesterday: Chassal Siddur Pesach Kehilchosan…

Yesterday, on the 1st day of Passover, I was in the big temple in Tschita at the valley prayer [?] and had lunch in the Talmud Torah building, later in the afternoon also had tea there and was here again in the evening.

The city is 7 kilometers from here; despite the fact that it had snowed quite heavily just yesterday, during the night and throughout the day the snow and wind made themselves unpleasantly felt, I am extremely satisfied with yesterday.

The impressions I gathered yesterday will probably stay alive for a long time and I won’t soon forget the valley prayer [?] in the Tschita temple.

Three men and the Russian guard, who followed with rifle and fixed bayonet, counting our four, we walked about 1 1/4 hours at a rather brisk pace through the snowy forest, in which for the time being no footsteps were to be seen, to the town. We soon came to the wheeled path, where it was easier, and it wasn’t long before we saw the building of the big penal house, in front of which many guards were standing.

In the east lane, which leads from the road into the city, in Ingodinskaya, so named after the river Ingoda that flows past here, there is also the large, whitewashed temple with a broad dome that can be seen from afar. Some stairs lead from the foundation, which has a certain height, to the entrance. The temple itself is quite high and although it now only has a women’s gallery, it seemed to me higher than the temple in Bucharest, also a bit bigger. Very simple painting, everything in white (also inside), the light floods through large, wide windows. Nevertheless, in honor of the day, the temple was electrically lit and all the bulbs were lit. Quite a few prisoners with posts and a large native audience had appeared, but they did not fill the great temple; in passing I noticed tuxedos and tailcoats, many wide silk thongs, few top hats.

The valley prayer [?] was performed by a religious leader Schlesinger, who, according to today’s newspaper, received the Anne’s Order [Order of Saint Anna] in his capacity as a member of the supervisory board of the Russian State Bank of Tschita. I also exchanged two words with Rabbi Herr Lewin, maybe he will write to you again…

I came back a little tired, but with a lifted feeling that I had walked through the snow to the “valley”.

Here, too, Passover was celebrated according to the regulations under the supervision of a Hungarian-Jewish doctor, who performed the Musaf prayer in the local prayer room today.

On the first night of the Seder, I sang part of the Seder…

Via Auction.ru, this undated postcard shows the Chita Synagogue.

As does this image, from Stephanie Comfort’s flickr photostream.

Taken by E. Kutysheva on March 6, 2018, this image (“Чита Синагога – Русский Здание синагоги в Чите – 2018 03“) gives a contemporary view of the Chita Synagogue. Though intact, the building no longer serves as a center of Jewish life. The “broad dome” noted by the unknown prisoner – the central cupola – no longer exists, and, the Mogen David(s) that surmounted each of the smaller cupolas have vanished.

This Yandex map shows the building’s location on Ingodinskaya Street…

…while at a smaller scale, this Oogle map shows the general geography of Chita. Note the Ingoda River (as mentioned in our unknown POW’s letter) that winds adjacent to and within the southern part of the city, and, Lake Kenon on the city’s western edge.

The city is directly east of the southern part of Lake Baikal…

…and directly north of Mongolia. (By over 125 miles.)

Pessach in Tschita und Pjetschanska

Pjetschanska, Mittwoch, 6./19. April (Pessach), 2. Tag abends.

Vielgeliebte Eltern und Schwester!

Trotzdem viele Schwierigkeiten zu überwinden waren, kann ich getrost die Worte der Hagadah auf den gestrigen Tag anwenden: e chassal siddur pessach Kehilchosan…

Gestern, am 1. Pessachtage, war ich im grossen Tempel in Tschita beim Talgebet und habe im Talmud-thoragebäude zu Mittag gegessen, später nachmittags dort auch Tee genommen und war gegen Abend wieder hier.

Die Stadt ist 7 Kilometer von hier entfernt; trotzdem es gerade gestern ziemlich stark geschneit hatte, in der nacht und den ganzen Tag über Schnee und Wind sich fortgesetzt unangenehm fühlbar machten, bin ich mit dem gestrigen Tage überaus zufrieden.

Die gestern gesammelten Eindrücke werden wohl lange Zeit lebendig bleiben und ich werde das Talgebet im Tschitatempel nicht so bald vergessen.

Drei Mann und den russischen Posten, der mit Gewehr und aufgepflantzem Bajonett folgte, miteingerechnet, unserer vier, gingen wir ungefähr 1 ¼ Stunden in ziemlich lebhaftem Tempo durch den verschneiten Wald, in dem vorerst keine Fussstapfen wahrzunehmen waren, nach der Stadt. Wir kamen bald auf den fahrbaren Weg, wo es leichter ging, und es dauerte nicht lange, da sahen wir schon das Gebäude des grossen Strafhauses, vor dem viele Wachen standen.

In der estern Gasse, die vom Wege in die Stadt führt, in der Ingodinskaya, nach dem hier vorbeifliessenden Fluss Ingoda so genannt, steht auch der grosse, ganz weiss getünchte Tempel mit einer breiten, weithin sichtbaren Kuppel. Einige Treppen führen vom Fundament, das eine gewisse Höhe hat, zum Eingang. Der Tempel selbst ist ziemlich hoch und trotzdem er jetzt nur eine Frauengalerie hat, schien er mir höher als der Tempel in Bukarest, auch etwas grösser. Sehr einsache Malerie, alles in Weiss gehalten (auch drinnen), das Licht fluter durch grosse, breite Fenster. Trotzdem war der Tempel zu Ehren des tages elektrisch beleuchtet und alle Birnen waren entzündet. Recht viele Gefangene mit Posten und zahlreiches einheimisches Publikum waren erschienen, doch füllten sie nicht den grossen Tempel; im Vorbeigehen bemerkte ich Smokings und Fracks, viele breite Seidentalessim, wenige Zylinder.

Das Talgebet verrichtete ein Kultusvorsteher Schlesinger, der laut heutiger Zeitung den Annernorden in seiner Eigenschaft als Aufsichtsrat der russischen Staatsbank von Tschita erhalten hat. Mit dem Rabbiner Herrn Lewin habe ich auch zwei Worte gewechselt, vielleicht schreibt er Dir noch…

Etwas müde zwar, aber mit gehobenem Gefühl, durch Schnee zum „Tal“ gegangen zu sein, kam ich züruck.

Auch hier wurde unter Oberaussicht eines ungat.-jüdischen Arztes, der heute das Mussaphgebet im hiesigen Betlokal verrichtet hat, vorschriftsmässig Pessach gefiert.

Am ersten Sederabend sang ich einen Teil des Seders vor…

______________________________

_______________

______________________________

Just a photograph: Yiddish and Hebrew poet, essayist, and writer Uri Zvi Greenberg (alternative: Uri Tsevi Grinberg; Hebrew: אורי צבי גרינברג), during his service in the Austro-Hungarian army. (Photo from Zeev Galili’s Blog, Logic in Madness (היגיון בשיגעון), within his April 20, 2009 post Uri Zvi Greenberg – the poet who predicted the Holocaust (אורי צבי גרינברג – המשורר שחזה את השואה).)

The Great War has long been recognized as having a significant and enduring impact upon twentieth century poetry and literature, a legacy that persists to this day. A poet whose verse is stunning in its power, visual symbolism, moral clarity, and eventual political and religious urgency, Uri Greenberg arrived in the Yishuv in December of 1923, by which time he’d become a supporter of Zionism as the only path for the survival of the Jews of Europe. Perhaps his vision about the future of European Jewry is best embodied in his poem “In malkhes fun tseylem” (In the Kingdom of the Cross), “his last great Yiddish work before he emigrated to Palestine and channeled his burgeoning poetic energies into the writing of Hebrew poetry.”

The following excerpt from Glenda Abramson’s article in the Fall, 2010, issue of Shofar, “The Wound of Memory – Uri Zvi Greenberg’s ‘From the Book of the Wars of the Gentiles’”, describes Greenberg’s war experiences in terms of their being an impetus for (but by no means the sole influence upon) the development of his subsequent literary oeuvre:

In 1914 Greenberg was conscripted into the Imperial army, and after a brutal period of basic training in Hungary he was sent to the even more brutal frontline trenches on the Serbian border. Although a bookish and sensitive young man apparently unsuited for war service, Greenberg participated in all the battles fought in Serbia until the fall of Belgrade and distinguished himself in the field, although the experience scarred him for the remainder of his life. In his first book, published in 1915 with the title Ergits oif felder (Somewhere in the fields), he writes, “The world is a great graveyard and you—nothing but shadows, eternally afflicted on the isle of death.”

In the winter of 1914 on the Serbian front Greenberg fought in the Battle of Cer on the River Sava in which about 25,000 Austro-Hungarian officers and men were killed and wounded, and around 4,500 were captured. The weather was bad, rain and mud adding to the armies’ difficulties. In this campaign, between Austria, Germany, and Bulgaria on the one side and Serbia on the other, the Austrians crossed the river under fire from the Serbs, who strongly and effectively resisted, in order to reach Belgrade. The number of casualties was high during the river crossing, and when the forces reached the opposite bank they launched an attack on the enemy trenches, which were encircled with barbed wire. Greenberg was one of the few survivors of those who were ordered to mount the wire to reach the Serbian trenches. The Imperial army lost the battle. Greenberg saw his dead comrades hanging upside down on the wire, a sight that left a profound and lasting impression on him.

Or, as described at YIVO: “Summarily drafted in 1915, Grinberg experienced the horrors of warfare in which many of his fellow soldiers died or were severely wounded. The fording of the Save River, in particular, etched itself in his memory, and was to reappear obsessively in poems he would write throughout his life. Exposed to enemy fire while crossing the river, Grinberg suddenly found himself alone and disoriented in a Serbian post on the other side of the river. All his fellow attackers were hanging lifeless, heads down and boots pointing up, on the electrified wire, while all the defenders were probably killed by a hand grenade. Then the moon shone from the clearing autumnal sky, casting its silvery light on the well-worn metal cleats of the upturned boots of the soldiers. The poet was mesmerized by the eerie effulgence, which he was never to forget. The image would later inspire the title of his first Hebrew book: Emah gedolah ve-yareaḥ (Great Terror and Moon; 1925). What he saw then – a heap of cadavers illuminated by moonlight – amounted to a horrendous negative epiphany: an indifferent God incorporated in dead and mutilated human flesh. This proved to be one of the sources of Grinberg’s modernistic vision. Still, when Bikeles-Shpitser published Grinberg’s first poetry collection, Ergets oyf felder (Somewhere in the Fields; 1915) he included in it, without violating the unified tonality of the slight booklet, both the war poems the poet had penned when still safe in his parents’ home and those he sent from the battlefield.”

You can gain more insight into the life and poetry of Uri Tzvi Greenberg at the blog of Israel Medad – long-time resident of Shiloh, Samaria, Israel – MyRightWord.

______________________________

_______________

______________________________

Year 1917 – I

Published in the newspaper’s correspondence section, this letter, by Corporal Alfred Ellinger, and, Einjahr Freiwilliger (One-Year Volunteer) Konrad Heim on behalf of their comrades, focuses on the social, communal, intellectual, and spiritual challenges facing Jewish soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian military, the correspondents implying that in such matters, Jewish soldiers have essentially been left to themselves. This is juxtaposed against support received Gentile soldiers, and, Jewish soldiers in the German military, the latter whose needs are met by Jewish organizations in that country. The letter concludes by imploring the leaders of the Jewish community in Vienna, and, Jewish organizations in that city and beyond, to assist their sons at the Front.

Open letter to the leaders of the Austrian Jewry in Vienna.

November 9, 1917

Issue Number 43, Page 708 (Issue page 8)

From the front we address these lines publicly to the leaders of Judaism in Austria. The largest Jewish community in Austria is in Vienna; the heads and leaders of this community are therefore also the leaders of all Austrian Jewry and have repeatedly publicly acknowledged themselves as such. The venerable President of Vienna’s Israelite religious community is also President of the Israelite Alliance and the Austrian Association of Communities. We Jewish soldiers at the front must turn to him and his colleagues with our specifically Jewish needs.

The Jewish soldiers at the front have other interests that stem from Judaism in addition to those shared with all their comrades. Judaism means to us one of the few spiritual values through which one feels a constant connection to one’s homeland; it is a refuge for us in the hours of despair and mental depression. The war has deepened our interest in everything Jewish, and we want to know how things are with Judaism at home. The lively interest of the Jewish soldiers at the front for Jewish things found only insufficient satisfaction. Why don’t you take care of such matters? The Lord’s administration does not have the task and duty of satisfying all such needs. The Christian soldier is well supplied with religious and national literature through the efforts and achievements of non-governmental organizations. Why does Judaism not think of bestowing the same kindness and care on its sons in the field? A German prayer book for the field, for example, which, if written with understanding, satisfies the sensibilities of the educated, would be an urgent need and should be sent to every soldier from home free of charge.

Magazines are too rare an article at the front, and Jewish works and books are almost impossible to find. And yet (with all recognition of the difficulty of realizing it) every man should have at least one Jewish newspaper or magazine at his disposal. A concise field edition of the history of the Jewish people up to the present would be most welcome.

Our comrades of Jewish faith in the German army are much better cared for and cared for by Jewish organizations in Germany. They receive a lot of reading material with Jewish content and their own commemorative publications of an instructive nature for every Jewish holiday.

We are at the front and initially fighting for Kaiser and fatherland. But we also fight for the honor of Judaism at the same time. The Jewish leaders in Vienna should seriously consider this. As we faithfully do our duty in need and death at the front, we also fight for the honor of the Jewish name. Does Austrian Jewry feel no obligations towards their sons at the front? We hereby want the leaders of Viennese Jewry to accept these serious duties, the presidents and heads of both the community and the Alliance, as well as other organizations, of these serious duties. Should it then be said that Jews only fulfill those duties which are enforced by force, but neglect moral duties?

No! We hope that our public appeal will not go unheeded.

Alfred Ellinger, Corporal

Konrad Heim, One-Year Volunteer

on behalf of 40 Non-Commissioned Officers and

One-Year Volunteers

Offenes Schreiben an die Führer der österreichischen Judenschaft in Wien.

Von der Front aus Wenden wir uns mit diesen Zeilen öffentlich an die Führer des Judentums in Oesterreich. Die grösste jüdische Gemeinde Oeterreichs ist in Wien; die Vorsteher und Leiter dieser Gemeinde sind darum auch die Führer des österreichischen Gesamtjudemtums und haben sich wiederholt öffentlich als solche bekannt. Der ehrwürdige Präsident der Wiener israelitischen Kultusgemeinde ist auch Präsident der Israelitischen Allianz und des Oesterreichischen Gemeindebundes. Un ihn und an seine Kollegen müssen wir jüdischen Soldaten an der Front uns mit den spezifisch jüdischen Bedürfnissen, wenden.

Die jüdischen Soldaten an der Front haben neben den mit allen Kameraden geteilten noch andere, aus dem Judentum entspringende Interessen. Das Judentum bedeutet uns eines der wenigen geistigen Werte, durch die man sich fortwährend mit der Heimat verbunden fühlt; es ist uns eine Zuflucht in Studen der Verweiflung und seelischer Depression. Der Krieg hat unser Interesse für alles Jüdische vertieft, und wir wollen wissen, wie es mit dem Judentum in der Heimat bestellt ist. Das lebhafte Interesse der jüdischen Frontsoldaten für jüdische Dinge findet aber nur ungenügende Befriedigung. Warum sorgt man nicth für solche Belange? Die Herresverwaltung hat nicht die Aufgabe und die Pflicht, alle solche Bedürfnisse zu befriedigen. Der christliche Soldat wird mit religiöser und nationaler Literatur reichlich versehen, und zwar durch Bemühungen und Leistungen nichtstaaatlicher Organisationen. Warum denkt das Judentum nicth daran, seinen Söhnen im Felde die gleiche Wohltat und Sorgfalt zuzuwenden? Ein deutches Gebetbuch fürs Feld zum Beispiel, das, verständnisvoll abgefasst, das Empfinden des Gebildeten befriedigt, wäre ein dringendes Bedürfnis und sollte jedem Soldaten von der Heimet aus unentgeltlich geliefert werden.

Zeitschriften sind ein zu seltener Artikel an der Front, jüdische Werke und Bücher so gut wie gar nicht zu finden. Und doch müsste (bel aller Anerkennung der Schwierigkeit der Verwirklichung) jedem Mann mindestens eine jüdsiche Zeitung oder Zeitschrift zur Verfügung stehen. Eine kurzgesasste Feldausgabe der Geschichte des jüdischen Volkes bis zur Gegenwart wäre hochwillkommen.

Unsere Kameraden jüdischen Glabens in der deutschen Armee werden von jüdischen Organisationen in Deutschland ungleich besser bedacht und versorgt. Diese erhalten viel Lektüre jüdischen Inhaltes und eigene Festschriftchen lehrreicher Natur zu jedem jüdischen Feiertage.

Wir stehen an der Front und kämpfen zunächst allerdings für Kaiser und Vaterland. Allein wir kämpfen auch gleichzeitig für die Ehre des Judentums. Das sollten die jüdischen Führer in Wien doch ernstlich bedenken. Indem wir treu in Not und Tod an der Front unsere Pflicht ersüllen, kämpfen wir auch für die Ehre des jüdischen Namens. Empfindet das österreichische Judentum gegenüber seinen Söhnen an der Front gas keins Pflichten? An diese ernsten Pflichten wollen wir hiemit öffentlich die Führer des Wiener Judentums, die Herren Präsidenten und Vorsteher, sowohl der Gemeinde als auch der Allianz, sowie anderer Organisationen ernstlich gemahnt haben. Sollte es denn heissen, dass Juden nur soche Pflichten erfüllen, die durch Gewalt erzwungen werden, die moralischen Pflichten aber vernachlässigen?

Neine! Wir hoffen, dass dieser unser öffentlicher Appell nicht ungehört verhallen wird.

Alfred Ellinger, Korporal

Konrad Heim, Einj.-Freiw.

im Namen von 40 Unteroffizieren und

Einjährig-Freiwilligen

______________________________

_______________

______________________________

Just a photograph: “Postcard featuring Jewish soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian army, ca. 1914-1918”. From the Blavatnik Archive, the postcard is described as being 9 by 14 inches, but (!) I think that’s an error, the correct unit probably being centimeters. The reverse side of the postcard is absent of any information.

Of those men who survived the war, what became of them by 1927?

And 1937?

Were any still alive in 1947?

______________________________

_______________

______________________________

Year 1917 – II

Paralleling The Jewish Chronicle, and, l’Univers Israélite, throughout the war, Dr. Bloch’s Oesterreichische Wochenschrift regularly published lists of the names of Jewish servicemen who had received military awards, such compilations including the soldier’s rank, civilian occupation, town or city of residence, and, the name or title of the award he’d received. As a sad and inevitable parallel to these award lists, the newspaper published lists of casualties, albeit absent of the specific date and location when he was killed, missing or wounded. In either case, I don’t know the source of the information utilized by the Wochenschrift in this endeavor: Perhaps the names were collected by a central organization of the Austrian Jewish community.

An example follow below: A list of fifty Jewish officers and soldiers in the 307th Honved Infantry Regiment who received military awards.

Fifty Jewish Heroes of the No. 307 Honved Infantry Regiment.

January 26, 1917

Issue Number 4, Pages 53-55 (Issue pages 5-7)

In the Honved Infantry Regiment No. _____, which had been in existence since June 1915 and was first under the command of Colonel Julius Parsche, then under that of Lieutenant Colonel Paul Bozo, and which, according to the official Höser reports, was particularly distinguished in the Toporoutz battles, such as “Egyenlöseg” reports that the named officers and members of the squad received the highest awards, partly for brave and self-sacrificing behavior in front of the enemy, partly for excellent and particularly dutiful service:

Fünfzig jüdische helden des Honvedinfanterie-regiments Nr. 307.

Bei dem seit Juni 1915 bestehenden und zuerst unter dem Kommando des Obersten Julius Parsche, dann unter demjenigen des Oberstleutnants Paul Bozo kämpfenden und in den Toporoutzer Kämpfen auch laut den amtlichen Höser-Berichten sich besonders ausgezeichneten Honved-Infanterieregiment Nr. _____ haben, wie „Egyenlöseg“ berichtet, die nachkenannten Offiziere und dem Mannschaftspande angehörnden Personen teils für tapferes und aufopferundsvolles Verhalten vor dem Feinde, teils für vorzügliche und besonders pflichttreue Dienste Allerhöchste Auszeichnungen erhalten:

Names as listed in article…

Lebovics, Heinrich, Oberleutnant d.R. (1)

Erdös, Wilhelm, Chefstellvertreter (2)

Wurm, Nikolaus, Reserve Leutnant (3)

Müller, Arpad, Landsturm-Oberleutnant (4)

Merö, Bernhard, Mitchef, Oberleutnant d.R. (5)

Steiner, Edgar, Oberleutnant d.R. (6)

Strancz, Isidor, Reserveleutnant (7)

König, Armin (8)

Rosza, Rudolf, Einjährig-Freiwilliger (9)

Halasz, Andor, Dr., Regimentarzt (10)

Töröf, Heinrich, Dr., Assistenzarzt (11)

Fleischl, Josef, Reserveleutnant (12)

Kuttner, M.L., Landsturm-Fähnrich (13)

Levac, Karl, Landsturm-Veterinärarzt (14)

Keppich, Alfred, Rechnungsunteroffizier 1. Klasse (15)

Fischer, Arthur (16)

Deak, Ludwig (17)

Reich, Armin, Landsturm-Fähnrich (18)

Witrael, Wilhelm, Rechnungsunteroffizier 1. Klasse (19)

Wolf, Desider, Rechnungsunteroffizier 1. Klasse (20)

Pick, Emerich, Sanitätsfähnrich d.R. (21)

Marton, Alexander, Rechnungsunteroffizier 1. Klasse (22)

Kalman, Arthur, Feldwebel (23)

Fleischmann, Ignatz, Rechnungsunteroffizier 1. Klasse (24)

Nathan, Moritz, Rechnungsunteroffizier 2. Klasse (25)

Rosenzweig, Julius, Feldwebel (26)

Elkan, Paul, Rechnungsunteroffizier 1. Klasse (27)

Fülöp, Aler. (28)

Holczmann, Max, Landsturm-Oberleutnant (29)

Fessler, Adolf (30)

Farago, Nikolaus, Fähnrich (31)

Rona, Bela, Fähnrich (32)

Löwy, Friedrich, Feldwebel (33)

Neumann, Bernhard, Fähnrich (34)

Steiner, Josef, Leutnant (35)

Stern, Adolf, Zugsführer (36)

Hecht, Josef (37)

Horn, Adolf (38)

Laszlo, Adolf, Reserveleutnant (39)

Ringwald, Arthur, Zugsführer (40)

Stern, Julous, Landsturm Fähnrich (41)

Szel, Ladislaus, Fähnrich (42)

Spitzer, Moriz, Zugsführer (43)

Schwarz, Franz, Feldwebel (44)

Stein, Heinrich, Oberrechnungsführer 1. Klasse (45)

Aigner, Ludwig, Fähnrich (46)

Schneider, Isidor, Zugsführer (47)

Raab, Wilhelm (48)

Leipnik, Alexander, Einj.-Freiw.-Fähnrich (49)

Weiner, Jakob (50)

Listed alphabetically…

Aigner, Ludwig, Fähnrich (46)

Deak, Ludwig (17)

Elkan, Paul, Rechnungsunteroffizier 1. Klasse (27)

Erdös, Wilhelm, Chefstellvertreter (2)

Farago, Nikolaus, Fähnrich (31)

Fessler, Adolf (30)

Fischer, Arthur (16)

Fleischl, Josef, Reserveleutnant (12)

Fleischmann, Ignatz, Rechnungsunteroffizier 1. Klasse (24)

Fülöp, Aler. (28)

Halasz, Andor, Dr., Regimentarzt (10)

Hecht, Josef (37)

Holczmann, Max, Landsturm-Oberleutnant (29)

Horn, Adolf (38)

Kalman, Arthur, Feldwebel (23)

Keppich, Alfred, Rechnungsunteroffizier 1. Klasse (15)

König, Armin (8)

Kuttner, M.L., Landsturm-Fähnrich (13)

Laszlo, Adolf, Reserveleutnant (39)

Lebovics, Heinrich, Oberleutnant d.R. (1)

Leipnik, Alexander, Einj.-Freiw.-Fähnrich (49)

Levac, Karl, Landsturm-Veterinärarzt (14)

Löwy, Friedrich, Feldwebel (33)

Marton, Alexander, Rechnungsunteroffizier 1. Klasse (22)

Merö, Bernhard, Mitchef, Oberleutnant d.R. (5)

Müller, Arpad, Landsturm-Oberleutnant (4)

Nathan, Moritz, Rechnungsunteroffizier 2. Klasse (25)

Neumann, Bernhard, Fähnrich (34)

Pick, Emerich, Sanitätsfähnrich d.R. (21)

Raab, Wilhelm (48)

Reich, Armin, Landsturm-Fähnrich (18)

Ringwald, Arthur, Zugsführer (40)

Rona, Bela, Fähnrich (32)

Rosenzweig, Julius, Feldwebel (26)

Rosza, Rudolf, Einjährig-Freiwilliger (9)

Schneider, Isidor, Zugsführer (47)

Schwarz, Franz, Feldwebel (44)

Spitzer, Moriz, Zugsführer (43)

Stein, Heinrich, Oberrechnungsführer 1. Klasse (45)

Steiner, Edgar, Obertleutnant d.R. (6)

Steiner, Josef, Leutnant (35)

Stern, Adolf, Zugsführer (36)

Stern, Julous, Landsturm Fähnrich (41)

Strancz, Isidor, Reserveleutnant (7)

Szel, Ladislaus, Fähnrich (42)

Töröf, Heinrich, Dr., Assistenzarzt (11)

Weiner, Jakob (50)

Witrael, Wilhelm, Rechnungsunteroffizier 1. Klasse (19)

Wolf, Desider, Rechnungsunteroffizier 1. Klasse (20)

Wurm, Nikolaus, Reserve Leutnant (3)

______________________________

_______________

______________________________

More to follow from Dr. Bloch’s Oesterreichische Wochenschrift

… Jewish in the Allied Armed Forces

… Jewish Aviators in the K.u.K. Luftfahrtruppen (Kaiserliche und Königliche Luftfahrtruppen)

… Jewish Life Beyond the Great War

______________________________

_______________

______________________________

And even more…

Austria-Hungary, at…

fine-de-siècle, at…

Austro-Hungarian Army, at…

… Austrian Philately (John Dixon-Nuttall)

… The World of the Habsburgs (“Jewish soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian army”)

… Jewish Artifact Education (Rabbi Binyamin Yablok’s Virtual Jewish Museum)

… Israeli Ministry of Defense (Jewish Combatant Collection)

Joseph Samuel Bloch, at…

… Geni.com

… Jewish Encyclopedia (Eisenberg, Das Geistige Wien, s.v.; derived from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.)

… YIVO

Uri Tzvi Greenberg…

Abramson, Glenda, “The Wound of Memory – Uri Zvi Greenberg’s ‘From the Book of the Wars of the Gentiles’”, Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies, V 29, N 1, Fall, 2010, pp. 1-21

Galili, Zeev, Uri Zvi Greenberg – The Poet who Predicted the Holocaust (אורי צבי גרינברג – המשורר שחזה את השואה), at “Logic in Madness” (Zeev Galili’s blog (היגיון בשיגעון -הטור המקוון של זאב גלילי))

(From Zeev Galili’s blog: “Reporter at “Yediot Ahronoth” – chief reporter at the news desk, chief of reporters, editorial center and acting editor-in-chief. A columnist in the “Mekor Rishon” newspaper. Teaches in academia (communication, philosophy), effective writing instructor in dozens of businesses, government offices and public institutions, author of children’s books, shadow writer – all former.”)

Weingrad, Michael, “An Unknown Yiddish Masterpiece That Anticipated the Holocaust – Written in 1923, ‘In the Crucifix Kingdom’ depicts Europe as a Jewish wasteland. Why has no one read it?”, at Mosaic.com,

April 15, 2015

… at YIVO Encyclopedia

Chita, Russia, at…

… Wikipedia (Chita, Zabaykalsky Krai)

Chita Oblast, at…

Jews of Chita, at…

… JewishGen (email by Naomi Fatouros – September 21, 1998)

… Jewish Telegraphic Agency (“Jewish Population of Chita Drops 75 Percent in Decade” – July 10, 1931)

Otherwise, …

Eldad, Israel, The Jewish Revolution – Jewish Statehood, Shengold Publishers, Inc., New York, N.Y., 1971

Gilbert, Martin, Atlas of Jewish History, Dorset Press, 1984

Roth, Joseph, Flight Without End, J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd., London, England, 1984

Vital, David, The Origins of Zionism, Oxford University Press, Oxford, England, 1980

Wistrich, Robert, Zionism and Its Religious Critics in fine-de-siècle Vienna, Jewish History, V 10, N 1, Spring, 1986, pp. 93-111