“…the fact that its entire crew of five are all from New York.”

_______________

Definitions of the phrase “New Yorker”…

… at Wordnik:

“a native or resident of New York (especially of New York City)”

… at Cambridge Dictionary:

“someone from the US city of New York”

“someone from the US state of New York”

…at Collins Dictionary:

1. a. “of the state of New York”

1. b. “of the city of New York”

2. a. “a person born or living in the state of New York”

2. b. ” a person born or living in the city of New York”

______________________________

My prior post, The Invisible Sailor – The Invisible Jew?, concerning Warner Brothers’ 1943 film about the United States submarine service, Destination Tokyo, focuses on a fascinating scene that arrives at the film’s halfway point. After “Mike”, one of the sub’s crew, is murdered – quite literally stabbed in the back – by a Japanese fighter pilot ostensibly in the act of surrender, the Greek-American sailor “Tin-Can” (played by Dane Clark, actual name Bernard Elliot Zanville) is unwilling and unable to attend the former’s funeral. Tin-Can’s absence from the ceremony sparks anger and shock from his fellow crew members, who take deep offense at his detached and seemingly passive reaction to the death of a fellow crewman. Then, with great and increasing intensity, Tin-Can explains the reason for his absence. He relates how the suffering of his family in German-occupied Greece – particularly the murder of his kindly philosopher uncle – has become the central motivation for his military service, which is a form of patriotism and deeply personal – if not familial and ethnic – revenge against the Axis. In a story otherwise devoted to action, adventure, drama, and occasional moments of levity (what, with Alan Hale, Sr.!), Tin-Can’s speech grounds the film upon a plane of seriousness and depth.

But, I believe there was a story behind Tin-Can’s story. As I explain fully in the post, given the ownership of the studio that produced the film, as well as identity of some of the writers, producers, and actors involved in the movie’s creation – let alone the time-frame of the film’s release – I believe that the writers and producers of Destination Tokyo used Tin-Can’s speech as a disguised soliloquy about the fate of of the Jews of Europe. The proviso being of course, that unapologetically and explicitly drawing attention to the fate of the Jews of Europe in the context of fighting the Axis powers, in a form of popular entertainment created for a nationwide audience, was – in the Hollywood of 1943 – perceived as being anathema, in terms of cultural, social, and professional acceptability.

Anyway, Destination Tokyo was a movie; a story; fiction, in which reality lay behind a cloak of invisibility.

In the world of life; of fact; of literature and journalism, there are other forms of invisibility; even if unintentional; even if benign. But, just as in Destination Tokyo, the absence of a fact can “speak” far more loudly and leave a far deeper impression, than if it is mentioned … even if briefly, even if fleetingly, even if in passing. This will reveal more about the writer, publisher, and tenor of the times, than the story itself. Such was the case of a news item published in The New York Times in early 1944…

But first, by way of explanation:

Many of my posts on this blog – an ongoing series as it were?! – focus on the military service of Jewish soldiers during the Second World War. These are centered around news items about Jewish military casualties from the New York metropolitan area, which were published in The New York Times, in the final two years – 1944 and 1945 – of that global conflict.

Appearing under the heading “Jewish Soldiers in The New York Times in WW II”, I’ve created about forty such posts as of the completion of “this” post in mid-July of 2023. As explained more fully at Soldiers from New York: Jewish Soldiers in The New York Times, in World War Two, the now-distant impetus for this effort was my review of every issue (seriously!) of the Times published between late 1940 and 1946 for any news item related to the military service of Jewish soldiers during that time. (I did this in the 1990s by reviewing the Times on 35mm microfilm. Lots and lots of microfilm. Did I say lots? Lots!) The goal of this endeavor was to learn about the experience and thoughts of Jewish soldiers in the Armed forces of the Allies in the context of the Shoah, and, the historical experience of the Jewish people during that awful, complex, and transformative time.

I thought – when I began this research three now-seemingly-distant decades ago – given the Times being a newspaper headquartered in Manhattan, with the New York metro area then being the demographic “center” of Jewish life in the United States, that the newspaper would occasionally feature news items about the implications or aspects of Jewish military service during the war, even if in passing: even if tangentially; even only hesitantly. Well, was I wrong about that. Very wrong. Completely wrong; completely-upending-your-assumptions and jaw-droppingly kind of wrong.

Certainly news about American Jewish servicemen (and on vanishingly rare occasions, Jewish soldiers in the armies of other Allied nations) appeared in the Times, but this facet … or central aspect? … of their identity was never a focus of the paper’s reporting, assuming it fell into the awareness of the paper’s journalists and editors to begin with. Well… Given the history of the Times, the prevailing self-perception of the Jews of America at that time, and, the nature of the times (pun entirely intended), perhaps this was inevitable. An example of this, from early 1944, follows…

On February 4 of that year, this article, by an anonymous Times correspondent, appear in the first section of the newspaper:

FIVE NEW YORKERS ON INVASION PLANE

Crew of Butchski Plan to Run ‘Overseas Branch of the Bronx Express’

By Cable to THE NEW YORK TIMES.

AT A UNITED STATES TROOP CARRIER COMMAND STATION in Britain, Feb. 3 – All the twin-engined transport planes on this station look alike in their grubby green-brown war paint, but one is really different. Its two chief points of difference are the white lettered name Butchski on the nose and the fact that its entire crew of five are all from New York.

When the invasion starts and the troop-carrier command begins shuttling combat soldiers from bases to actual fighting fronts Butchski will become an “overseas branch of the Bronx Express,” according to its crew. Every member of the crew agrees the service will be strictly “express.”

The skipper of Butchski is quiet, youthful-looking Capt. E.M. Malakoff of 60 East Ninety-fourth Street, Manhattan. A graduate of Penn State and New York University Law School, he passed the New York bar examination in 1941.

He is only 27 years old now, but handles the transport plane as if he had been flying it all his life. The plane is named for his 9-year-old brother James, whose nickname is Butchski.

Co-Pilot “Typical New Yorker”

Lieut. James P. Wilt of 538 East Sixteenth Street is co-pilot. He maintains he is the most typical New Yorker because he was born in Dayton, Ohio, twenty-five years ago and moved to New York to attend New York University after having gone to the University of Cincinnati. After finishing school he worked in radio before joining the Army. His father and mother, Mr. and Mrs. Noble Wilt, now live in Troy, Ohio, with his younger brother and sister.

Flight Officer Saul Bush, who is 25 years old and lives at 1749 Grand Concourse, the Bronx, is the navigator of Butchski. He insists his chef distinction is that he is the only married man in the crew and he feels sorry because the other members will never be able to marry a girl as incomparable as his wife, Beatrice, who lives in the Bronx. He attended De Witt Clinton High School and City College in New York.

Staff Sgt. David Lifschutz, who says he “was born, reared and hopes to die” in New York, is the fourth member of the crew. He is only 21. His home is 32-17 Seventy-seventh Street, Jackson Heights, and for years before he joined the Army he used to hang around La Guardia Field hoping to be a flier one day. He attended Long Island City High School and his parents still live at the Seventy-seventh Street address.

Youngest Member Is 20

Staff Sgt. Lester Leftkowitz [sic], who attended Morris High School and lived at 586 Southern Boulevard, the Bronx, with his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Samuel H. Lefkowitz, is the fifth and youngest member of the crew. He is just 20 years old.

The job of Butchski is to haul paratroops and tow gliders loaded with airborne fighting men to fighting areas when the invasion starts. They all realize it is a tough job, but one that has to be done, and they are just waiting until the time comes to do it.

Here’s how the article appeared in the paper:

______________________________

Biographical information about each of these men follows below. (A minor caveat: “Letfkowitz” is actually “Lefkowitz”.) As will soon be evident as you scroll through this lengthy post, Captain Malakoff was killed in action, but every member of his crew survived the war. With the significant caveat, that Staff Sergeant Lifschutz was shot down and taken prisoner of war in late December of 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge.

And so, Butchski’s crew:

Pilot: Capt. Seymour M. Malakoff, 0-660774, Air Medal, Purple Heart

Mr. and Mrs. Jacob John (3/6/91-6/14/55) and Vera (Ida) (Partman) (7/12/90-11/18/43) Malakoff, 60 East 94th St., New York, N.Y.

James Leonard “Butchski” Malakoff (brother) (6/20/33-7/24/07)

Born New Haven, Ct., 10/24/16

The New York Times 2/4/44, 6/27/44

Casualty List 7/25/44

Forvarts 6/29/44

Co-Pilot: Lieutenant James Philip Wilt

Mr. and Mrs. Walter Noble (5/21/93-1984) and Katherine (Harper) (Folckemer) (1/4/93-12/29/61) Wilt (parents)

Robert N. Wilt (brother) (1/6/30-7/2/60), 234 South Plum St., Troy, Oh.

Wartime residence: 538 East 16th St., New York, N.Y.

Born Dayton, Oh., 4/2/18; Died 12/13/78

Riverside Cemetery, Troy, Oh. – Section 1, North West Corner

Navigator: Flight Officer Saul Bush

Mrs. Beatrice (Rosen) Bush (wife), 1749 Grand Concourse, Bronx, N.Y.

Mr. and Mrs. Alfred and Dora (Stein) Bush (parents), 2101 Morris St., New York, N.Y.

Born New York, N.Y., 6/29/19; Died 10/20/04

American Jews in World War II – Not Listed

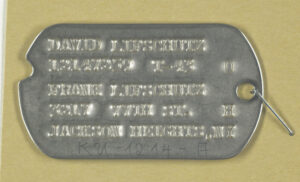

Radio Operator: S/Sgt. David Lifschutz, 12147259, Air Medal Three Oak Leaf Clusters, Purple Heart

Mr. and Mrs. Ephraim (“Frank”?) and Claire Lifschutz (parents), 32-17 77th St., Jackson Heights, N.Y.

Born New York, N.Y., 6/3/22

Casualty List 6/13/45

Long Island Star Journal 4/14/45, 6/14/45

American Jews in World War II – 381

Crew Chief: S/Sgt. Lester Lefkowitz (Hersch G’dali bar Shmuel), 12182071

Born Bronx, N.Y., 5/25/23; Died 10/3/00

Mr. and Mrs. Samuel H. and Etta Leftkowitz (parents), 586 Southern Boulevard, Bronx, N.Y.

Mount Ararat Cemetery, East Farmingdale, N.Y.

American Jews in World War II – Not Listed

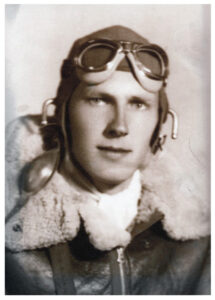

What about Seymour Malakoff? … He received his pilot wings and was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant on May 20 1942. His portrait appears below. Taken when he was aviation cadet, it’s from the United States National Archives, where it’s one image among thousands of similar photos within 105 archival storage boxes encompassing the collection “RECORDS OF THE ARMY AIR FORCES – Photographic Prints of Air Cadets and Officers, Air Crew, and Notables in the History of Aviation”.

Lt. Malakoff’s portrait, “P-14933”, is in box 57.

(Digression one: The overwhelming majority of these images were taken during the very late 1930s, and early 1940s; with a very small number from WW I and the twenties. A few civilian flyers (like Amelia Earhart and Anthony Fokker) are also present, along with a few images of famous German WW I aviators. Most of the portraits are of Flying Cadets, or, men who had just graduated as Second Lieutenants and received their “wings” from Army Air Force pilot, bombardier, and navigator schools. The majority of the images seem to have been taken from 1941 through 1943, with some from 1944, and a very few thereafter.

Some pictures were taken outdoors, along an airfield flight-line, apparent from background scenery. Some, with photographic back-drops of aircraft, clouds, or other aviation-related images, were obviously taken in studios. Other were taken in simple, unadorned, indoor settings. Some images are printed upon 8 ½” x 11” black & white glossy finish photographic paper, while others, of smaller dimensions, are mounted upon (glued to) heavy 8 ½” x 11” stock. Typically, information such the date of the photograph, name and rank of subject, and the aviation school where the image was taken is recorded with the image; sometimes on the image itself.

Inevitably, given the coincidence between the timing of their graduation and the time-frame of the Second World War, many of these men were killed in action, while others lost their lives in training or operational accidents. Similarly, it is notable that there are no photographs of aircrews; only individuals. Notably, this collection of photographs comprises a limited number of the tens of thousands Army Air Force pilots, bombardiers, navigators who were Aviation Cadets, or were commissioned, during World War Two.)

______________________________

The Times article obviously attracted attention well beyond the confines of Manhattan, for it was referenced in Walter Winchell’s column three days later, in which S/Sgt. Lifschutz was mentioned in reply to comments by Mississippi Senator John E. Rankin concerning the latter’s remarks about the ethnic backgrounds of American servicemen. Here are the first two paragraph’s from Winchell’s column:

By Walter Winchell

The Man on Broadway

NEW YORK, Feb. 7. – Man About Town:

U.S. Senator Styles Bridges is helping his State Department heart trousseau shop … Al Jolson is Jinx Falkenberg’s most constant visitor at her St. Luke’s Hospital bedside… Dorothy Fox, the dance director, got a quiet melting down (from her Naval Intelligence bridegroom in Florida last week)… Barbara Booth, who understudied Hepburn in “Without Love,” was secretly married last week in San Francisco to an Army lieutenant… New Yorkers suspect that Wayne (wife-killer) Lonergan’s sudden coin (to hire a lawyer) came from men named in her diary… Betty Hutton is Capt. C. Gable’s morale builder this week… “Under Cover” author Carlson is 1-A and rarin’ to go.

HERR RANKIN’S disparagement of certain war heroes is the consequent result of a defense mechanism. He is Chairman of the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee. Rankin is a World War I war vet – by virtue of 17 days’ service… The AP reports that the first American ashore on the Anzio beaches (south of Rome) was Pvt. Walter P. Krysztofiak, a father, of Illinois. Wonder what Rankin would say about this American whose name can hardly be pronounced? … And then there’s the New York Times report of Feb. 4 (about New Yorkers making up the crew of a bomber) – one crew man being Staff Sgt. David Lifschutz… You can tell Rep. Hoffman from the others in Congress. While he talked about a march on Washington – his constituents were more interested in a March of Dimes… Ralph Pearl says Hoffman is so unimpressive (haw!) he goes in one eye – and out the other.

Here’s how Winchell’s column actually appeared … as published in the Syracuse Herald-Journal:

______________________________

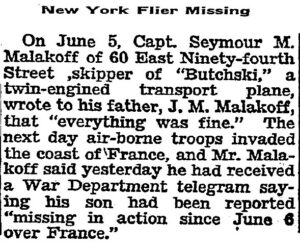

If the Times article of February 4 was (in its own way) enlightening, the following very small news item, published on June 27, three weeks after D-Day, was much sadder: It reports that Captain Malakoff was missing in action.

New York Flier Missing

On June 5, Capt. Seymour M. Malakoff of 60 East Ninety-fourth Street, skipper of “Butchski,” a twin-engined transport plane, wrote to his father, J.M. Malakoff, that “everything was fine”. The next day air-borne troops invaded the coast of France, and Mr. Malakoff said yesterday he had received a War Department telegram saying his son had been reported “missing in action since June 6 over France.”

______________________________

What happened?

Missing Air Crew Report 8409 reveals that Captain Malakoff was the pilot of C-47A 43-30735 (otherwise known as “CK * P” / chalk # 37 / “Butchski II“), of the 75th Troop Carrier Squadron, 435th Troop Carrier Group, 9th Air Force. His aircraft was one of nineteen 9th Air Force C-47s lost during D-Day (this number based on MACRs covering C-47 losses on June 6), with the 435th losing two other aircraft, both from the 77th Troop Carrier Squadron. These planes were 42-24077, “IB * J”, piloted by 1 Lt. James J. Hamblin (MACR 7801), and 43-30734, piloted by Captain John H. Schaefers (MACR 8414). Identical to Captain Malakoff’s “Butchski II” (as will be evident a few paragraphs down…), there were no survivors from the crew of either transport; four men in Lt. Hamblin’s crew, and 5 in Captain Schaefers’.

(Digression two: Here’s the insignia of the 75th Troop Carrier Squadron. (It’s from Ebay seller abqmetal.))

The fate of Butchski II is described in this excerpt from Ian Gardner’s Tonight We Die As Men, the story of the 3rd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, encompassing the history of the Battalion’s from its creation through D-Day. The excerpt describes the loss of the C-47 as seen from the ground.

The two men moved cautiously off along the line of the wall toward a hedge. A few minutes later they discovered George Rosie hiding under a tree. He was overjoyed to see them. They remained hidden in the hedge for a while wondering what they should do. Suddenly Rosie pointed in the direction of the farmhouse and muttered something through his broken teeth that sounded like, “Jesus Christ. Look!”

A C-47 had been hit, its port engine was on fire and it was banking sharply to the right. The men watched as the aircraft leveled out and its paratroopers started to jump. As the last man left the aircraft it became totally engulfed in flames. It was then that Gibson, Lee, and Rosie realized that it was heading directly toward them. They flattened themselves against the ground and the stricken plane tore through power lines and swept 20 ft above their heads before exploding in a ball of flame at Clos des Brohiers. Just moments later they were surprised to see four men, silhouetted by the inferno, sprinting toward them. A water-filled ditch briefly interrupted their run, but they waded in and quickly scrambled out. Watching in amazement, Gibson’s small group could not believe their eyes. Before them, covered in mud and dripping wet, were Cyrus Swinson, Leo Krebs, Phil Abbey, and Francis Ronzani. All four had jumped from the same plane as Gibson. They had been hiding in a field and the burning plane forced them out.

Dr. Barney Ryan had landed in the flooded area close to L’Amont and could see something burning furiously on higher ground nearby. He had met up with three other men and led them toward the fire. Ryan recollects, “I couldn’t be sure what was burning at the time but thought it was an aircraft. We were shot at by figures running around the flames. As we weren’t supposed to open fire until daybreak we guessed they must be Germans.” The figures were probably Mongolian soldiers who could see Ryan’s group illuminated in the flames. Their firing forced Ryan and his men to dive under the water and swim away.

The burning plane had been carrying 18 men from H Co, 501st Bn. They had been scheduled to jump on Drop Zone C, which was about 3 miles north of the crash site. All the paratroopers got out safely but unfortunately the plane’s five-man crew perished in the inferno. The aircraft was piloted by Capt. Malakoff from the 435th Troop Carrier Group’s 75th Troop Carrier Squadron, based at Welford in Berkshire. It was probably hit shortly after crossing the French coast and fell back in the formation. Losing altitude and unable to reach the drop zone, the pilot switched on the green light allowing the paratroopers to jump to safety before the plane crashed.

______________________________

Missing Air Crew Report 8409 includes thirteen (!) eyewitness accounts pertaining to the loss of Captain Malakoff’s C-47. These comprise a total of ten statements from the eighteen paratroopers aboard the plane (all eighteen jumped successfully) and, statements from Captain Paul W. Dahl (C-47 42-92093), and First Lieutenants Charles P. Kearns, Jr. (C-47 42-100675) and Edgar H. Albers, Jr. (C-47 42-92099), fellow pilots in the 75th Troop Carrier Squadron. Here’s Captain Dahl’s statement:

I last saw Captain Malakoff as we entered the West Coast of the Cherbourg Peninsula. I was leading the second element of the 4th Squadron. Captain Malakoff was leading the last squadron directly behind me. Immediately after crossing the coast we went into an overcast laying over the coast directly on our course. I turned out to the right a short distance to avoid collision with other ships in the overcast and then resumed course letting down until I broke out beneath the overcast. If Captain Malakoff had continued straight on course he undoubtedly would have caught up with us out on our left. A short time after breaking out of the overcast I was fired upon from the ground, guns firing all over the sky. I saw two ships explode and go down in flames off to our left front about 300 to 500 feet above. Approximately one-half a minute later I made a left turn into the D.Z. (my navigator recognizing it) and it was about this time I saw a violent explosion directly to our left and then saw the flames engulfing the remnants of the plane as it went down. I would say this occurred about approximately one mile Northwest of the DZ according to my navigator’s calculations. The exploding plane was at about the same altitude as we were which was 1000 ft indicated letting down. I definitely saw tracers going into the explosion. I had to make a left turn into the DZ because of the previous right turn I made in the overcast which is another fact that might indicate Captain Malakoff’s being off to my left.

I would estimate Captain Malakoff’s speed at 140 to 150 mph the last time I definitely saw him before we entered the overcast.

I was in the overcast approximately few and one half minutes. We were under fire most of the time after breaking out of the overcast.

______________________________

This statement is by Pvt. Joe L. Cardenas, of (at the time) H Company:

I was the last man in my stick, the last to jump from the plane. Because of my position near the radio compartment I couldn’t see out but 1 did notice the plane lurch a little possibly from wing hits. Lt. Hoffmann [1 Lt. John W. Huffman] gave the order to “stand up”, “hook-up”. The crew chief came out and said that he thought they were coning in south of the DZ. He told us to hold it up and I passed this word down the line. He then went back to the pilot. He came out again and wanted to know why we were in the plane and went back into the pilot’s cabin. He came out again, rather excited and said “we are coming over the DZ when you get the light. “Go! Go! Go!” The plane seemed to be OK. I had no trouble getting out. I never saw the plane again after I jumped.

______________________________

Missing Air Crew Report 8409 lists C-47 43-30735 as having last been seen west of Etienville, France. In reality, the plane crashed on the ground of the Frigot Farm, about two miles north-northwest of Carentan. Several images of Butchski II’s crash site can be seen at TAPA Talk (“Meehan Crash Site“), while Mark Bando has this account at The Carrington News:

C-47 #43-30735 (pilot Seymour M. Malakoff) belonged to the 75th TCS and was shot down during mission Albany on D-day. Butchski II came down near Frigot Farm on D-Night, just north of the road that runs straight east toward Basse Addeville [La Basse Addeville] from Dead Man’s Corner. The plane was carrying the stick of 3rd platoon H/501. Capt. Seymour Malakoff, pilot, 2nd Lt. Thomas Tucker, co-pilot, 1st Lt. Eugene Gaul, navigator, Sgt. Paul Jacoway flight engineer, S/Sgt. Robert Walsh, radio … were all killed in the crash.

All the troopers on board including Harry Plisevich, Len Morris, Robert Niles, Paul Solea, and Clarence Felt jumped before the ship went in. Solea’s reserve chute opened accidentally in the plane, causing a four minute delay in jumping. Due to the cloud banks and ground fire which brought down two other planes of the same serial carrying G/501st personnel [42-24077 and 43-30734], the plane had strayed off-course. Butchski II was actually hit somewhere south of Carentan and then began a route bringing her NE, on an angle that took her above Addeville. She then turned back west bound and the occupants of the Frigot farm on the north side of the road just west of the A13 overpass heard it go over their house before she crashed a few fields over. There was a AA battery on the high ground just north of Chateau Bel Enault [Château Bellenau], which was pumping rounds at the plane as it turned west, losing altitude all the while, one of the troopers [Pvt. Fred J. DiPietro, 15354752?] that jumped was KIA shortly after landing between Baupte and Raffoville, when he knocked on the door of a French farmhouse and a German answered, probably with a pistol in his hand. From Mark Bando…

These two air photos show the Frigot Farm, which lies at the intersection of D913 and Rue du Bel Esnault, bounded by rows of trees adjacent to each road. Based on photos at TAPA Talk, the aircraft crashed adjacent to one of the two northwest-southeast oriented rows of trees subdividing the property: the long row in the very center of the image, or, the diminutive row in the farm’s southwest corner.

This photo, at a smaller scale, shows the setting of the Frigot Farm relative to Château Bellenau, which is just southwest of La Basse Addeville.

______________________________

Words and maps can only convey so much. The photo below, also from Gardner’s book (as is the caption), shows the burnt-out wreckage of Captain Malakoff’s C-47 a few days after D-Day. Little is left of the aircraft except for the fin, an outer portion of one wing, and fragments of bent and burned aluminum.

“Pvt. Walter Hendrix from E Company 506th stands beside the burnt-out remains of 75th Troop Carrier Squadron C-47 “Butchski II”, which crashed near Frigot Farm on D-Day. The plane was carrying men from H Company 501st, who all jumped to safety before it crashed. Unfortunately its crew were not so fortunate and Capt. Seymour Malakoff (pilot), 2 Lt. Thomas Tucker (co-pilot), 1st Lt. Eugene Gaul (navigator), Sgt. Paul Jacoway (flight engineer) and S/Sgt. Robert Walsh (radio operator) all perished in the inferno. (Forrest Guth picture, Carnetan Historical Center)”

I do find it notable that whereas the Times gives the nickname of Captain Malakoff’s C-47 as “Butchski“, Missing Air Crew Report 8409 and other sources list the aircraft’s name as “Butchski II“. Whether this reflects an error in the Times’ article, or, the fact that there was an original “Butchski (one)” replaced by a C-47 dubbed “Butchski II” … in the tradition of so many USAAF WW II aircraft … I’ve no idea.

______________________________

Captain Malakoff’s crew on this mission – their first, last, and only mission – comprised:

Co-Pilot: 2 Lt. Thomas A. Tucker, 0-686291, Buffalo, N.Y. (Born 1918)

Forest Lawn Cemetery, Buffalo, N.Y.

Navigator: 1 Lt. Eugene Edward Gaul, 0-807185, Newark, N.J. (Born 7/4/20)

Long Island National Cemetery, East Farmingdale, N.Y. – Plot H, Grave 7930

Flight Engineer: Sgt. Paul B. Jacoway, 39097783, Fort Smith, Ak. (Born 5/22/18)

Fort Smith National Cemetery, Fort Smith, Ar. – Section 4, Grave 2163

Radio Operator: S/Sgt. Robert Donald “Donny” Walsh, 37397005, Saint Louis, Mo. (Born 4/6/21)

Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery, Lemay, Mo. – Section OPS3, Grave 2307E

I’d suppose that his original crew, as listed in the Times, was broken up as a unit prior to D-Day, and distributed among other crews in the 75th Troop Carrier Squadron. In any event, as mentioned above, all of Captain Malakoff’s original crewmen survived the war.

Captain Malakoff is buried at Normandy American Cemetery, St. Laurent-sur-Mer, France, Plot F, Row 18, Grave 18. Like Flight Officer Bush and Sergeant Lefkowitz, his name is absent from American Jews in World War II.

______________________________

Perhaps inspired by the Times, on June 29 the Forvarts published the following news item about Lieutenant Malakoff. Given the formal nature of the portrait, what with the fluffy white scarf and jauntily placed cap and headphones, this picture was probably taken during his pilot training in the United States – possibly upon his graduation from pilot training and commissioning as an officer – and before his assignment to the 435th Troop Carrier Group. I suppose the picture was sent to his parents, who then provided the image to the Forvarts.

Though I don’t know Yiddish, I think the approximate translation of the title is rather straightforward: Something to the effect of “Jewish Pilot Flies Airplane with Parachutists”. The word “Butchski“, phoneticized in Yiddish, definitely appears in the article. It’s in quotes in the third line from the bottom.

__________

_______________________

And now, submitted for your consideration:

The elephant in the living room.

…or…

The rhinoceros in the foyer.

_______________________

__________

Getting back to the Times’ article.

Well, yeah.

Captain Malakoff’s crew were most definitely “New Yorkers” by either residence or birth. That’s explicitly stated in the Time’s article’s first paragraph. That all but one of the airmen in the crew were Jews was, however, entirely left unmentioned. Perhaps this “silence” about the coincidence of four Jewish airmen assigned to the same aircrew, in the European Theater of War, arose because it wasn’t even noticed to begin with. (That, I seriously doubt.) Perhaps it was deemed irrelevant. (That is surely possible.) Perhaps it was left unmentioned because the story’s anonymous author and editor adhered to and tacitly accepted the Times’ deeply animating ideology which has continued to negate an acceptance of Jewish peoplehood. (Surely that’s possible too.)

But still, in the cultural context of the forties and the next few decades (not so much any more),the phrase “New Yorker” was a verbal shorthand that not always, but not uncommonly had a certain Jewish connotation or “ring” to it – on occasion positive; sometimes ambivalent; perhaps neutral; sometimes negative – whether in politics, popular culture, or comedy.

Walter Winchell’s column, published three days after the Times’ story, made mention of David Lifschutz as a way of refuting Congressman John E. Rankin’s statements about American Jews. But, even accounting for the fact that Winchell was a gossip columnist, something’s clearly “off” with with his article just as much as there is in the Times’ original story. On a minor point, Butchski was a transport, not a bomber. On a major point, obviously having combed the article for details, why did Winchell not deign to mention Seymour Malakoff, Saul Bush, and Lester Lefkowitz? Given the length of his very long column – of which the above image is only a beginning snippet – why the silence about these three men? Though my knowledge of Winchell’s life only comes from Wikipedia, what stands out from his biography is that despite – or perhaps as a consequence; perhaps as a cause – of his all-too-fleeting fame and social prominence (in a personal life characterized by turbulence and tragedy); despite his father having been a part-time cantor – his only real connection to Judaism and the Jewish people was in his ancestry.

Plus, the Magen David on his Matzeva.

Yet, there could be another explanation for the nature of the Times’ article: Perhaps there were aspects of the Times’ reporter’s conversation with the crew of Butchski – then unrecorded and now unknown – that never reached the printed page. In this, I’m reminded of comments made to me by a Jewish WW II veteran who flew B-17s in the 8th Air Force, several of whose crew members were Jews, and whose brother (a ball turret gunner) and cousin (1st Lieutenant Morris Leve; see also…) were killed in action while serving in the 15th and 8th Air Forces, respectively.

As he related in a late 1993 interview:

Me: Can you recall any other Jewish guys who were in your squadron, besides the guys in your crew?

Veteran: Oh yeah. Yeah. We had a…we had a guy; he was a navigator. A fellow by the name of Bill L. And Bill L.… Bill L.… He had worked for the…he worked for the Daily… He had some kind of a job with the Daily News. … The fact that he had worked for the newspaper, I guess, you know… He was… Let me see, how can I say it? You know, he wanted…he wanted in the worst way, to publicize…the fact… He hung onto my crew…because we had so many Jews. And he wanted…he wanted to…you know, to throw out a lot of publicity about it and I turned him down, while we were overseas. And I said, “No, no, no. I don’t want to do that.”

The one thing that he did, and it was printed in the Brooklyn Daily Times, or Times Union…I forget what the hell the name of the paper was… He had a picture taken of Irving S. and myself…at the airplane, glancing at a…at a map, and he had written a small article. He and some other guy… I forget what the hell his name was. He was our…he was our PR man. He was also Jewish. And he was the squadron PR man.

And…and they…they had this little article, and they titled it as, “Brooklyn Flak Dodgers”, you know, and he was showing me how we could dodge the flak and all this other bullshit!, but… But it was never printed that way, in the paper. It was just printed…and I have a copy of it…it was printed just as, “Two… You know, as “Two Brooklynites on the Same Crew”. That’s all. Just some little article in the… And I have it someplace. I don’t know where.

And I have that picture, too. I have a copy of the picture.

Me: But he tended to want to socialize with your crew?

Veteran: No, no no no no. No, he didn’t… No, there was…there was no socializing at all. He…the only thing that he wanted to do… He wanted to, you know… I guess, he wanted…he wanted to write, about “this Jewish crew, that were doing ‘this’ and were doing ‘this’ and were doing, you know. And he wanted to…he wanted some sort of notoriety about it, and I didn’t want…I didn’t want it. I said, “No, I don’t care for it.”

I came in…I…I had…I had my brakes shot out on one mission. I had the hydraulic system that was just… My whole hydraulic system went bad, you know, just the…the fluid leaked out. It was shot up? And, I made, what they called…referred to as a…”Stars and Stripes Landing”, using a parachute to…you know, to…to slow me down so that I could…

Me: Out the waist windows or something like that?

Veteran: No no, out the tail. And we used that parachute out the tail, and he wanted to make a big tzimmis [Yiddish for fuss] about it, and I said, “No, I don’t want it Bill.” I said, “I’ll tell you what you do. Write a nice article about my tail gunner, who’s”…what the hell is his name?…P., Henry P.… I said, “Write an article about Henry P.; that P. threw his parachute out the tail, to slow us down so that we didn’t run off the runway.” And that was…that was it.

I didn’t want… I was kind of… You know, I was…superstitious about it, you know.

Me: About the Jewish angle being played up.

Veteran: Well, about any angle… I was superstitious about any kind of, really, publicity. You know, trying to make a…trying to make a hero out of us, you know?

Me: That it would be tempting fate?

Veteran: I think so, yes. That was my feeling.

__________

_______________________

As mentioned above, the only casualty among Captain Malakoff’s original crewmen would eventually be his radio operator, S/Sgt. David Lifschutz. Here’s his photo, from the Long Island Star Journal of June 14, 1945.

Remaining in the 75th Troop Carrier Squadron, S/Sgt. Lifschutz was a crew member aboard C-47A 43-48718 (the un-nicknamed CK * A) when, during the re-supply mission to American troops in Bastogne, Belgium on mid-afternoon of December 26, 1944, his plane was shot down by anti-aircraft fire. Coincidentally; ironically, S/Sgt. Lifschutz’s pilot this day was Captain Paul Warren Dahl, whose eyewitness account (see above) of the loss of Butchski II on D-Day figures so prominently in the Missing Air Crew Report for Captain Malakoff.

This photo of the Dahl crew, dated June 17, 1944, is from Captain Paul Dahl, 75th TCS, 435th TCG, at Honouring IX Troop Carrier Command.

Unfortunately, the only person actually identified in the photo is the Captain himself, at center rear. This photo of Captain Dahl, from his biography at FindAGrave, was taken while he was a flying cadet.

Even if names can’t be correlated to faces, I think it’s possible to attach names to faces based on information in the relevant Missing Air Crew Report, number 11322.

Along with Captain Dahl and S/Sgt. Lifschutz on the December mission were the following men:

Co-Pilot: 2 Lt. William L. Murtaugh, 0-809998

Navigator: 1 Lt. Zeno Hardy Rose, Jr., 0-807314

Flight Engineer: T/Sgt. George T. Gazarian, 31125533

Passenger: Sgt. John J. Walsh, 36321092, member of 3rd Air Cargo Resupply Squadron

Missing Air Crew Report 11322, covering the loss of this aircraft, includes accounts by three crewmen of a nearby C-47, as well as detailed reports by Captain Dahl and Lt. Murtaugh. The latter two men, along with Lt. Rose and Sgt. Walsh, landed by parachute in no-man’s-land between German and American forces, but were immediately saved from death or capture by soldiers from the 318th Infantry Regiment of the 80th Infantry Division. It turned out that Captain Dahl, Lt. Murtaugh, and Sergeant Walsh were wounded either when their plane was struck by anti-aircraft fire, or, injured when they landed by parachute, all having bailing out from an extremely low altitude. Murtaugh was most seriously hurt, but Navigator Zeno Rose was much more fortunate, emerging from the ordeal unwounded.

This report about the men’s rescue was filed by the Adjutant of the 435th Troop Carrier Group on January 2, 1945, when the status of the plane’s two other crewmen – S/Sgt. Lifschitz and T/Sgt. Gazarian – was still “Missing in Action”:

2 January 1945.

1st Lt Zeno H Rose, 0807314, 75th Troop Carrier Squadron, this organization, reported “Missing in Action” on “Missing Air Crew Report”, this headquarters, dared 28 December 1944, has returned to this organization.

The following is extracted from interrogation of Lt Rose and is submitted as supplemental to “Missing Air Crew Report”.

“We took off from Station 474 about 1211 BST, 26 December 1944, and flew as the lead ship of the right element of the 75th TC Squadron in the 435th formation. About two end one half minutes before we reached the DZ at Bastogne, Belgium, we were subjected to enemy fire from both light machine gun and light flak. Both types of fire were effectively hitting our airplane knocking out the instrument panel on the right side, and at that time, the co-pilot, Lt Murtaugh, was hit by both MG and AA fire that broke his right shoulder or collar bone. This caused profuse bleeding and severe pain, however, Lt Murtaugh remained at his position and carried on his duties. At this scene time, the flak burst hit me, although the injury was slight.

Our bundles both in the pararacks and the cabin were ejected over the DZ about 1525 BST. We made a sharp right turn and were in formation on the ran out when about 2-1/2 minutes from the DZ light flak burst in the cockpit, most probably severing the fuel lines, knocking out the instruments, wounding Captain Dahl and starting fires in the forward part of the airplane. Captain Dahl rolled the trim tab back checked the power which was already on full, and gave the order and signal for balling out.

I quickly proceeded to the cabin door and saw that the enlisted men had net yet jumped; they seemed to be hesitant possibly because of our altitude. There was no hesitancy on my part so without further thought, I jumped and was followed by the enlisted men. (I later learned that the enlisted men were followed by Lt Murtaugh and then Captain Dahl.) It seemed that we were about three hundred and fifty feet above the ground at that time and my parachute opened instantly. During my descent to the ground I could hear enemy bullets whizzing past. I landed near some woods southwest of Bastogne and north of Assenois at approximately P325545, which at that time was between our lines and these of the enemy. There was a great deal of fire coming toward me so I feinted dead until I could become oriented.

Captain Dahl, Lt Murtaugh and Sgt Walsh landed at a position about 100 yards southeast of my landing near or in the woods and they were picked up by the same organization that joined me. Captain Dahl had a broken arm, some wounds and lacerations from flak and burns about the nape of his neck; Lt Murtaugh had the broken shoulder, several flak wounds about the face and a sprained ankle, and Sgt Walsh had a broken leg. All three as well as myself were given medical aid at the Aid Station, then sent to a clearance station, then to a field hospital and then to the 103rd Hospital about forty miles south of Bastogne.

Before departing from the area in which we landed, we were told that the parachute of one of the men had not opened and that in the case of the sixth man, that he had landed closer to the enemy lines and that he had been taken prisoner or had been killed by the enemy.”

Lt Rose interrogated by Captain Clement A. Erb, Intelligence Officer, 75th Troop Carrier squadron, this organization.

The members of this air crew were flying in aircraft C-47A, No. 43-48713, organizations and present status indicated; crew position indicated:

Dahl, Paul W., Captain, 0 401 356, Pilot, 75th TC Sq “SWA”

Murtaugh, William L., 2d Lt., 0 809 998, Co-Pilot, 75th 7C Sq “SWA”

Rose, Zeno H., 1st Lt., 0 807 314, Navigat., 75th TC Sq “RTD”

Gazarian, George T., S/Sgt., 31 125 533, Aer Eng, 75th TC Sq “MIA”

Lifschutz, David., T/Sgt., 12 147 259, Rad Opr., 75th TC Sq “MIA“

Sgt John J. Walsh, 3rd Air Cargo Re-Supply Squadron, was flying on subject aircraft, and was reported as battle casualty by his organization.

MACR 11322 includes the following map, indicating that the C-47 crashed just west of what is today highway N4, north of Remonfosse and east of Assenois.

This Apple air photo shows Assenois at lower left center, Remonfosse to the east, and Bastogne to the north. The blue circle indicates the approximate area where the crew landed by parachute – as suggested by the MACR – while the black circle indicates the (again) approximate crash location of C-47A 43-48718.

The status of Sergeants Lifschutz and Gazarian, like Captain Dahl on their 9th mission, was uncertain at least through March of 1945. However, the fate of both Sergeants was established by the war’s end, as revealed in the Individual Casualty Questionnaires as completed by Lt. Rose and incorporated into MACR 11322. (Rose’s are the only such Questionnaires in the MACR.)

Sergeant Gazarian (31125533) was killed, either in an unsuccessful parachute jump, or due to ground fire from German troops. Given that witnesses reported seeing five, and not six, parachutes, the cause was most likely the former. Born on January 3, 1907, the thirty-seven year old sergeant from Waterbury Ct., is buried at Old Pine Grove Cemetery, Waterbury, Ct.

S/Sgt. Lifschutz was immediately captured on landing, as revealed in Lt. Rose’s Questionnaire. Given that he and Lt. Rose met one another on May 12, 1945, perhaps he returned to the 75th Troop Carrier Squadron after his liberation, while en route back to the United States.

The very fact that Lt. Rose was able to record a full list of S/Sgt. Lifschutz’s missions, which were completely identical in date and number to those flown by T/Sgt. Gazarian and Captain Dahl, suggests that Lifschutz, Gazarian, Rose, and Dahl had been members of the same crew commencing with the Normandy invasion. Thus – following that logic – with the exception of Lt. Murtaugh, for whom the flight of December 26 was his first (and only?) mission – these are the men who appear in the photo of the Dahl crew: Gazarian and Lifschutz in front.

The POW camp in which S/Sgt. Lifschutz was interned is unknown, but that he was a POW is solidly verified by the standard Luftgaukommando Report form “Meldung über den Abschuss eines US-amerikanischen Flugzueges“(“Report About the Shooting Down of a US Airplane”), in report KU 1214A. The Report also includes a crew list for C-47 43-48718, which includes Captain Dahl’s serial number. Oddly, an English-language transcription of this document can be found in MACR 11322, but the original sheet is missing from the actual Luftgaukommando Report.

(Digressing… The “A” suffix seems to have been used in Luftgaukommando Reports covering aircraft which had multiple crewmen – as opposed to single-seat fighters – in situations for which some crewmen were known to have evaded capture, or were otherwise unaccounted for, at the time the report was initially filed.)

Here’s S/Sgt. Lifschutz’s dog-tag.

Yes, it bears the letter “H”.

The Long Island Star Journal reported upon the Sergeant’s liberation and impending return in its issue of June 14, 1945, in a brief article which featured his portrait.

Bastogne Captive Awaits Return

Staff Sergeant David Lifchutz of Jackson Heights, who was captured Dec. 24 after he bailed out from his burning plane over Bastogne, was liberated April 29 and is in England awaiting shipment home.

A radio operator on a C-47 transport plane, the 23-yeard-old airman had flown over Holland, France and Germany in the year and a half he had been overseas. He wears the Air Medal with one cluster.

A graduate of Public School 126, Jackson Heights, Long Island City High School and the Hebrew Technical Institute, which is now a part of New York University, Sergeant Lifchutz worked in the Brooklyn Navy Yard as a shipfitter before entering the Army in 1943.

He is the only son of Mr. and Mrs. Ephraim Lifchutz of 32-17 77th Street.

I don’t know anything at all about the subsequent course of David Lifschutz’s life, but I suppose that given the passage of time, following the way of all men, he has passed into history.

But, it’s nice to remember a little bit longer.

Two Books.

Dublin, Louis I., and Kohs, Samuel C., American Jews in World War II – The Story of 550,000 Fighters for Freedom, The Dial Press, New York, N.Y., 1947

Gardner, Ian, and Day, Roger, Tonight We Die as Men: The Untold Story of Third Battalion 506 Parachute Infantry Regiment from Toccoa to D-Day, Osprey, Oxford, England, 2010 (see pages 153-155)

Digression Three…

In light of my post about Destination Tokyo, I’m contemplating a post about James Jones’ 1962 novel, The Thin Red Line, which was the basis of the 1964 film by Andrew Marton, and, the 1998 film by Terrence Malik. I’ve not seen either film (!), but I’m particularly curious about the 1998 version in light of Malick – as touched upon in weirdly brief passing by Peter Biskind at Vanity Fair – having “…changed Stein [Captain Bugger Stein], a Jewish captain, to Staros, an officer of Greek extraction, thereby gutting Jones’s indictment of anti-Semitism in the military, which the novelist had observed close-up in his own company.” This is in light of the many, many (did I say “many”?!) passages in the novel centered upon Captain Stein, by which Jones, a fantastic writer, with clear and obvious intent explored the officer’s experiences with tremendous perception, depth, and empathy.

So, in 1998, why was Captain Bugger Stein missing in action from The Thin Red Line?