This is the second of four posts covering Jewish military casualties on Friday, May 4, 1945, “this” post pertaining to members of the United States Army Air Force.

The four men listed here – 2 Lt. Bernard Prizer, PFC Rodney E. Jacobson, F/O Aldwyn W. Fields, and Cpl. Milton Jcobs – were casualties in very different settings. These ranged from a training flight in the United States (Prizer), to an as-yet-unknown ground action in Germany (Jacobson), to a combat mission against the Japanese (Fields and Jacobs).

Of the four, only Fields survived.

On Friday, May 4, 1945

(22 Iyyar 5705)

______________________________

United States

2 Lt. Bernard Prizer

450th Army Air Force Base Unit

– .ת. נ. צ. ב. ה –

תהא נפשו צרורה בצרור החיים

2 Lt. Bernard Prizer (0-763854) serving as a co-pilot, was killed in the crash of a Martin TB-26B Marauder (41-18241) piloted by 2 Lt. Arthur C. Middleton and assigned to the 450th Army Air Force Base Unit (Combat Crew Training Station, Night Fighter), based at Hammer Army Airfield, Fresno, California. The aircraft crashed 1 1/2 miles north of the city of Pinedale, with none of the plane’s six crewmen surviving. Investigators speculated that that cause of the accident was detonation of the port engine, which reportedly had been cutting out in flight.

Lt. Prizer was not buried in a Jewish cemetery in his home city of Cleveland, but instead in a Christian cemetery – the Little Bethel Freewill Baptist Cemetery, southwest of Macon, Georgia – presumably because his wife Margaret was from the city of Ideal.

Born Ohio, 2/6/17

Resided with wife at 944 F Street, Fresno, Ca.

Mr. and Mrs. Julius and Selma Prizer (parents); Edith and Nathan Prizer (sister and brother), 3421 E. 135th St., Cleveland, Oh.

Fresno Bee 5/5/45 (via GenDisasters.com, submitted by Stu Beitler) – see transcript below…

Fatal Army Air Forces Aviation Accidents in the United States, 1941-1945 – Volume 3: August 1944 – December 1945 – p. 1091 (Incident “5-4-45A”)

American Jews in World War II – 497

__________

From the Williams T. Larkins collection at 1000aircraftphotos.com, this 1945 photo shows a bedraggled but colorful TB-26B (42-43332) at Kingman, Arizona, before conversion to pots & pans, or, aluminum siding. Quoting 1000aircraft photos, “In 1943, a conversion program was initiated to strip B-26s of operational equipment and provide them with target towing gear. In all, 208 B-26B and 350 B-26C were converted in this way, and re-designated AT-23A and AT-23B in the advanced trainer category. These designations were later changed to TB-26B and TB-26C respectively…”

__________

FRESNO ARMY BOMBER CRASH KILLS 6 MEN

Fresno Bee – May 5, 1945

Six army airmen, including a Fresnan, were killed instantly yesterday afternoon when the twin engined medium bomber in which they were flying crashed and burned about two miles north of Camp Pinedale on the Yosemite Highway.

The Fresnan was Corporal PAUL H. BROWN, 25, a son of Sam Lee Brown of Orange, Tex. He had lived with Lieutenant Colonel and Mrs. Beverly H. Jones, 5707 Wilson Avenue, for the last six years, and attended the Fresno High School and the Fresno State College, where he played football before he entered the service three years ago.

The fatal accident was the most serious in the recent history of Hammer Field, and the first crash involving more than one or two fliers since a B-24 fell into Huntington Lake in 1943, killing six men.

Eye witnesses to the crash, including a rancher living nearby who reported to Hammer Field authorities the plane was in trouble when it passed over his home at treetop level, said the ship was having engine trouble before it struck the ground.

The terrain in the area is rolling, and small knolls rise several feet above the highway.

The pilot of the ill-fated ship was Second Lieutenant ARTHUR C. MIDDLETON, 29, a son of Mrs. Mary K. Chambers, 5000 East Broadway, Long Beach.

The copilot was Second Lieutenant BERNARD PRIZER, 27, whose home before he entered the service was at 3421 East 135th Street, Cleveland, O. He resided with his wife, Mrs. Margaret Jane Prizer, at 944 F. Street. Mrs. Prizer was taken to the Hammer Field Base Hospital, suffering from shock, after she was told of the crash which killed her husband.

The other four men aboard the plane were:

Sergeant JOSEPH J. HIZNY, 23, whose wife, Mrs. Anna Mae Hizny, resides at 1717 River Road, Pittston, Pa.

Sergeant JOHN B. SZUES, 29, a son of Mrs. Mary Szues, RFD (no number), Machias, N.Y.

Corporal PAUL F. REDHEAD, 29, a son of Mrs. Colista Redhead, 11815 Chesterfield Avenue, Cleveland, O.

BROWN is survived by three brothers, John G., a veteran of the marines, and Sammy B., both of whom live in Stillwater, Okla., and Frank, who has been a prisoner of the Japanese since Manila fell early in the war, and three sisters, Mrs. Glen Smith, Miss Helen B. Brown and Miss Lillian Brown, all of Valliant, Okla.

He had been stationed at Hammer Field for the last year as an aviation mechanic.

Shortly after the plane took off from Hammer Field, its crew radioed the control tower at the army base the ship was in trouble and was planning to try for a crash landing.

The radio report was the last word from the ship, and moments later army personnel at Hammer Field, about seven miles from the scene of the crash, saw smoke rising after the plane had struck the ground.

Competitors in the California State Open Gold Tournament pro-amateur division, playing on the Fort Washington Golf Course about three miles away, heard the explosion which followed the plane’s crash.

Hammer Field authorities said the plane was on a routine combat training flight when the fatal crash occurred. A board of army officers has been appointed to investigate the accident.

Fire crews from both Camp Pinedale and Hammer Field rushed to the scene of the crash after the report was received of the plane’s difficulties, but were too late to attempt any rescue work.

This image of Lt. Prizer’s simple matzeva is by FindAGrave contributor Doug Cromer.

________________________________________

European Theater

United States Strategic Bombing Survey

PFC Rodney Edward Jacobson

– .ת. נ. צ. ב. ה –

תהא נפשו צרורה בצרור החיים

Though one might ostensibly assume that every casualty associated with service in the Army Air Force would be directly associated with flying “in” or activity “with” an aircraft, PFC Rodney Edward Jacobson (36589029) shows that this was not – hardly at all – so. A member of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey, PFC Jacobson was killed only four days before the war’s end in Europe. The reasons is unknown: perhaps his unit was engaged in a firefight with German soldiers; perhaps he was riding in a vehicle which struck a mine; perhaps something else. He received the Purple Heart.

Born Detroit, Mi., 3/17/23

Mr. and Mrs. Harry [7/4/95-1/10/72] and Sophie (Victor) [1/2/97-8/12/81] Jacobson (parents), 1 Lt. Ivan Mayer Jacobson (brother), 2030 Chicago Blvd., Detroit, Mi.

Clover Hill Cemetery, Royal Oak, Mi. – Section 5, Lot 41; Buried 8/21/49

Student at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio; Member of Zeta Beta Tau fraternity

Casualty List 6/19/45

Detroit Jewish Chronicle 6/15/45, 10/1/48, 8/19/49

The Jewish News 6/15/45, 8/19/49

American Jews in World War II – 191

This portrait of PFC Jacobson, first published in the 1954 Jewish War Veterans of Michigan Golden Book, is one of the many images from that publication now viewable via the Jewish War Veterans – Department of Michigan.

__________

In this image from the October 1, 1948, of the Detroit Jewish Chronicle, of a plaque honoring members of Temple Beth El who served in the recently ended war, which specifically lists the names of those who were killed in action, or who – like Lieutenants Green or Weil – died in accidents, PFC Jacobson’s name appears fourth from the top in the right column. Biographical information about nine of these men – three in the army ground forces, four in the air force, and two in the navy – follows the image…

United States Army

Davis, Charles Pershing, PFC, 36128967, Purple Heart (Biak Island)

162nd Infantry Regiment, 41st Infantry Division

Killed in action June 14, 1944

Born August 1, 1918

Mrs. Helain (Abel) Davis (wife), 3255 Cortland St., Detroit, Mi.

Mrs. Rose Davis (mother); Cpl. Marshall, Raymond, and Bernard (brothers), 18015 Ohio Ave., Detroit, Mi.

Graduate of Detroit Institute of Technology

Clovel Hill Cemetery, Royal Oak, Mi.

The Jewish News 7/14/44, 11/3/44

American Jews in World War II – 189

Rafelson, Robert Julien, PFC, 36868672, Purple Heart (Rhine River, Germany)

Engineer Corps

Died of wounds March 13, 1945

Born March 15, 1914

Mrs. Ileen (Jacobson) Rafelson (wife); Tommy (son; YOB 1943), 18922 Muirland, Detroit, Mi.

Mr. Mark Rafelson (father), 18085 Oak Drive, Detroit, Mi.

Graduate of Adrian College; MS degree from University of Michigan

Beth El Memorial Park, Livonia, Mi. – Section 2, Lot 113, Grave 2

The Jewish News 4/6/45

American Jews in World War II – 194

Simon, Lewis Arthur, T/5, 36589807, Purple Heart (Germany)

Died February 20, 1945

2nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron

Born September 5, 1924

Mr. Harold Simon (father), 19 Lasalle Blvd., Detroit, Mi.

Woodmere Cemetery, Detroit, Mi. – Section North F; Buried 8/1/48

The Jewish News 3/9/45

American Jews in World War II – 196

United States Army Air Force

Green, Roy Frank, 2 Lt., 0-661308, Fighter Pilot

23rd Fighter Squadron, 36th Fighter Group

Killed in flying accident November 12, 1942. Aircraft crashed 5 miles south of Corozal, Puerto Rico

Aircraft: P-39D 41-6919

Born 1918

Mr. Max Greene (father); Mrs. Ida Greenberg (mother), Arlene, Ray and Russ (brother and sisters), 2923 Pasadena Ave., Detroit, Mi.

Clover Hill Park Cemetery, Royal Oak, Mi. – Section 17; Buried 5/13/48

The Jewish News 12/29/44

American Jews in World War II – 191

Jacobs, Alfred L., Sgt., 36145928

Killed in ground accident at Rapid City, South Dakota June 25, 1944

Born March 8, 1919

Mr. Henry Jacobs (father); Richard (brother), 931 Beaconsfield, Grosse Pointe, Mi.

Beth El Memorial Park, Livonia, Mi. – Section 6, Lot 72, Grave 6

The Jewish News 7/14/44

American Jews in World War II – 191

Seymour, William Seymour, 1st Sergeant, 39024032, Drop Crewman, Air Medal, Purple Heart

2nd Troop Carrier Squadron, 10th Air Force

Killed in action January 18, 1944

Aircraft: C-47 41-19476; Pilot: Capt. Ferde A. Larson; Eight crewmen – no survivors

Born 1909

Mr. Emil Schubot (father); Mr. Jules R. Schubot (brother); Betty, Maurice, Rosalind, Sadie, and Samuel (siblings), 18624 Wildemere, Detroit, Mi.

Lt. Harvey Schubot (brother), 400 N. Camden Drive, Beverly Hills, Ca.

Rock Island National Cemetery, Rock Island, Il. – Section E, Grave 407; Buried 6/8/50

Detroit Jewish News 2/25/44

American Jews in World War II – 195

Weil, Victor Hugo, 1 Lt., 0-513327, Co-Pilot

9th Ferry Squadron, 6th Ferry Group

Killed in flying accident October 7, 1943. Aircraft crashed at 3048 E Street, in San Bernardino, California

Aircraft: B-25H 43-4203; Pilot: 2 Lt. Randall R. Weiland; Three crewmen – no survivors

Born Michigan, March 27, 1901

Mrs. J.W. Roemer (sister), 49 Virginia Park, Detroit, Mi.

Woodmere Cemetery, Detroit, Mi. – Section North F, Beth El Plot, Lot 25, 26

Detroit Jewish News 10/15/43, 2/9/45

American Jews in World War II – 197

United States Navy

Kopman, Joseph W., Lt. JG, 0-283230, Fighter Pilot, Purple Heart

VF-13 (Navy Fighter Squadron 13), USS Franklin (CV-13)

Killed in action October 17, 1944, Pacific (ABMC lists date as October 18, 1945)

Aircraft: F6F-5 Hellcat 58375; Ditched, but did not survive.

Born 1922, Missouri

Mr. and Mrs. Saul Louis and Ann Kopman (parents), Fay Barbara Kopman (sister), 300 Whitmore Road, Detroit, Mi.

Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery, Manila, Philippines

The Jewish News (Detroit) 1/19/45

OurOldNavy

USSFranklin.org

American Jews in World War II – 192

Lewis, Leonard Leon, Lt. JG, 0-275815, Assistant Beachmaster, Purple Heart

6th Naval Beach Battalion

Killed in action June 6, 1944, in Normandy France (ABMC lists date as June 8, 1944)

Born April, 1924

Michigan State Normal College, Class of 1938

Mrs. Esther (Berger) Lewis (wife); Linda Stark (daughter; YOB 1943), 15818 Meyers Road, Detroit, Mi.

Mr. Jacob B. Lewis (father); Lillian, RM 3C George K., Philip, Albert, Henry, Warren (sister and brothers), 20 Worcester Place, Detroit, Mi.

The Jewish News (Detroit) 7/14/44, 1/19/45

Normandy American Cemetery, St. Laurent-sur-Mer, France – Plot J, Row 10, Grave 32

6thBeachBattalion.org

American Jews in World War II – 1923

________________________________________

Pacific Theater

20th Air Force

As has been recounted in many prior posts in this series (and recounted above for Lt. Prizer) many wartime casualties occurred in situations that were not actually associated with enemy action, or if a result of an encounter with the enemy, were not related to the immediacy of that event.

Such an incident on May 4, 1945 concerned Flight Officer Aldwyn Bernard Fields (T-129136), a B-29 Superfortress navigator in the 60th Bomb Squadron of the 39th Bomb Group. He was one of four survivors of the crew of eleven in B-29 44-70004 (an anonymous aircraft upon which the crew had intended, but never had the opportunity, to bestow the nickname “City of Cooperstown”) commanded by 1 Lt. Smith L. Edwards.

Rescued from the Pacific Ocean after bailout, the story of F/O Fields’ and the other three survivors is related in detail in MACR 14367.

This was F/O Fields’ first combat mission, and as a result of the tragic severity of his injuries, for which he received the Purple Heart (no Air Medal, let alone no Distinguished Flying Cross, the former necessitating the completion of five combat missions) it proved to be his only combat mission.

Born in Manhattan on August 28, 1917, F/O Fields was the son of Beatrice L. Fields (subsequently Kaplan), who passed away on April 6, 1959. His sister, Beverly (Fields) Sacks, lived at 69-10 Yellowstone Boulevard in Forest Hills, Long Island, while his father’s identity is uncertain. His father may (may…) have been Max Fialkoff (thus, the name change to “Fields”). If (?) so, the Fialkoff family experienced tragedy a full decade before the war, for the New York Times reported that a Max Fialkoff, a dress manufacturer born in 1891, took his life at his place of work – at West 33rd Street in Manhattan – on February 13, 1934.

Brief news articles about F/O Fields appeared in the Long Island Daily Press and Long Island Star Journal on June 20, 1945, while his name appeared in a Casualty List published in the New York Times on June 21. Beyond that, the only other facets of information I’ve been able to uncover about him indicate that he graduated from City College in 1938, attained a Master’s Degree – subject unknown – from Columbia University prior to World War Two, and postwar, was somehow associated – perhaps philanthropically? – with the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Aldwyn Bernard Fields, 65 years old, passed away on March 16, 1982. He is buried near his mother, at Wellwood Cemetery in West Babylon, New York. (Section 1, Block 3, Division 43897, Plot A-14, Grave 1).

As has become evident from the majority of posts in this series, akin to very many American Jewish WW II military casualties, or, servicemen who received military awards, Aldwyn Fields’ name never appeared in the 1947 book American Jews in World War II.

More about his story follows…

__________

Seen at Batista Field, Cuba, during training, here’s the Smith Edwards crew: (Replacement Crew 16, 60th Bomb Squadron) in a photo from Fold3, via Sam Pennartz. Names follow below…

Standing (left to right):

Hetherington, Donald W., 1 Lt. – Newfield, N.Y. – Pilot – Rescued (See also…)

Kelly, Odie Allen, 2 Lt. – Midland, Tx. – Radar Operator – Missing (KIA) (See also)

Fields, Aldwyn Bernard, F/O – Navigator – Rescued

Engelholdt, James Mathias, 1 Lt. – Fond du Lac, Wi. – Bombardier – Missing (KIA)

Edwards, Smith Long, 1 Lt. – La Salle, Il. – Airplane Commander – Missing (KIA) (See also…)

Anderson, Clyde Raymond, Sgt. – Buxton, Me. – Radio Operator – Rescued

Kneeling (left to right):

Arundale, Gerald Wilbur, S/Sgt. – Sheridan, Il. – Gunner (Central Fire Control) – Missing (KIA) (See also…)

Nyholm, Ernest E., Jr., Sgt. – New York, N.Y. – Gunner (Right Blister) – Missing (KIA)

Ogilvie, James R., T/Sgt. – Gunner (Tail) – Did not fly with this crew on this mission

Clark, Harry Wilber, T/Sgt. – La Grange, Il.- Flight Engineer – Missing (KIA)

Sitting (front):

O’Brien, Herbert J., Jr., Sgt. – Otsego, N.Y. – Gunner (Left Blister) – Rescued

____________________

Images of the emblem of the 60th Bomb Squadron are not too abundant, but an excellent example can be found – and purchased as a decal, in different sizes and formats – at MCGraphicsDecals. Since the image is copyrighted, I’m providing the aforementioned link, rather than showing the insignia itself, “here”!

____________________

As mentioned above, it had been the intention of the Edwards crew to bestow the nickname City of Cooperstown (as in Cooperstown, New York) upon their bomber, but fate never granted them this opportunity. However, if the wheels of time had revolved differently, this moniker would presumably have appeared in the style of nose art carried by other 314th Bomb Wing (thus, 39th Bomb Group) aircraft. This emblem was in the form of a pennant superimposed on a map of the United States, the pennant’s flagpole pointing to the specific town or city inspiring the aircraft’s name, with the name of that town or city marked on the pennant.

An example of this appears below: The nose art for B-29 City of Knoxville (44-69995), of the 458th Bomb Squadron, 330th Bomb Group. This image is from a set of “Original U.S. WWII B-29 Bomber City of Knoxville Bombardier Fuse Key Grouping – 20 Missions” at Original Military Antiques.

Via Ancestry.com, here’s Aldwyn’s graduation portrait in the yearbook of City College of New York, Class of 1938 …

… and, now twenty-eight years old, his portrait from the Long Island Star Journal on June 20, 1945, which accompanied an article about his rescue on the May 4 mission.

Here’s a transcript of the Star Journal’s article.

The text mentions Aldwyn’s B-29 as having been the Purple Shaft, but this was in error. As explained by Donald Hetherington (below), on arrival in the Pacific the Edwards crew and the real Purple Shaft (42-65361) were mistakenly assigned to the 19th Bomb Group. When the crew was transferred back to the 39th Bomb Group, the Purple Shaft remained with the 19th.

Lieut. Fields Wounded On Tokyo Raid

Second Lieutenant Aldwyn B. Fields, 24, Forest Hills flight officer on a B-29, “Purple Shaft”, was wounded while returning from a bombing raid over Tokyo, his mother, Mrs. Florence Fields of 69-10 Yellowstone Boulevard, has been informed.

The “Purple Shaft” had completed her mission, but caught fire and exploded on the way back to its Marianna base. Lieutenant Fields parachuted into the Pacific and was picked up by the Navy off Iwo Jima. He has been in the Army for three years and overseas three months.

He was graduated from DeWitt Clinton High School, the Bronx; City College, and received a Master’s Degree from Columbia. He was commissioned at Austin, Texas.

____________________

This brief newspaper article, published in the Cooperstown Evening Telegram on May 18, 1945, pertains to Sgt. O’Brien’s arrival in the Marianna Islands. The article specifically mentions that the crew’s B-29 was to be named after that city, but doesn’t actually specific that this nickname was really painted on the plane.

SUPER FORTRESS NAMED ‘COOPERSTOWN’

Cooperstown – The CWW of a B-29 Super-Fortress of which Sgt. Herbert J. O’Brien, Oaksville, is turret gunner, recently arrived in the Marianna Islands.

He was given the honor of naming the bomber and “Cooperstown” was the choice. O’Brien is the eldest son of three sons of Mr. and Mrs. Herbert O’Brien, in service. Cpl. Robert is with the Infantry in Germany and Richard is waiting call for Navy service.

____________________

This article about Sgt. O’Brien, from The Otsego Farmer of June 8, 1945, mentions him having been wounded on the mission of May 4, but (well, unsurprisingly) doesn’t give any details about the incident. (This article, and the preceding article from the Cooperstown Evening Telegram, were obtained via Thomas M. Tryniski’s Fulton History database / website.)

Sgt. O’Brien Awarded Purple Heart Medal

Sergeant Herbert J. O’Brien, Jr., of Cooperstown, was presented with the Purple Heart on May 16th. The medal was presented by his commanding officer, Colonel George W. Mundy, at a Superfortress base on Guam. Sergeant O’Brien was wounded in action on May 4th while participating in a Superfortress attack on strategic targets on Kyushu, Japan. Having recovered from his wound, he was returned back to duty on May 8th.

Sergeant O’Brien is the son of Mr. and Mrs. Herbert J. O’Brien of Cooperstown.

____________________

So, what actually happened to 44-70004 and her crew? In Missing Air Crew Report 14367, the story is best and most appropriately told in the vivid dispassion typical of military documents. Here it is:

Narrative Report [from Missing Air Crew Report]:

Prior to Abandonment:

The emergency of the aircraft developed at 0345 on May 4th. The position of aircraft was approximately 20 miles south of Iwo Jima at 10,000 ft. There was no indication of any trouble before the fire started. No one in the plane smelled or saw any smoke before the fire broke out. The fire was first seen by the radio operator [Anderson] in the vicinity of the voltage regulators under the Liaison Radio. The flames looked as if they were coming off the floor.

The radio operator notified the crew in the nose by voice. Steps were immediately taken to put out the fire with the extinguisher. The flames were out for a moment but started again and the extinguisher was empty. The radio operator made attempts to smother the flames with flak curtains but could not get at it to do any good.

Preparation for Abandoment:

A state of emergency was declared by the pilot. [Edwards] There was no electrical power as soon as the fire started. The pilot hit the gear switch to get nose gear down and also hit the alarm bell. The alarm bell gave one very short ring, but the nose gear did not start down. The co-pilot tried to call buddy ship but the radio was out and also the interphone became inoperative.

____________________

This Oogle map shows the approximate location of 44-70004’s loss, based on latitude and longitude coordinates (24-18N, 141-22 E) listed in the Missing Air Crew Report. To the best of my knowledge, there were no restaurants, hotels, pharmacies, or ATMs in this part of the Pacific Ocean in 1945, though I’m sure Iwo Jima has them aplenty now. (As for “transit”, “parking”, and “attractions”, wellll… In a sort of sense those sort of existed in 1945, but not in a sort of way anyone would want to take have taken advantage of. Sort of.)

____________________

The bombardier [Engholdt], engineer [Clark] and navigator [Fields] were attempting to crank the nose gear by hand. There was a great deal of smoke in the nose of the plane. It was a whitish grey smoke and very irritating. The windows in the pilot’s compartment were tried open and closed with no noticeable changes in the smoke.

Abandonment:

The co-pilot seeing that the efforts of the crew to get the nose gear down were not going too well, as he was coughing a great deal and couldn’t see very well, left the co-pilot’s seat to go back to the bomb bay door to tell the men in back to bail out. The co-pilot saw the CFC gunner [Arundale] going through the tunnel to tell the men in back to bail out. The radio operator [Anderson] jumped down in the bomb bay and pulled the emergency handle. The doors opened and he fell out. The co-pilot [Hetherington] was standing on the cat walk and was just going back inside when the navigator came out and jumped. He was so badly burned that he was hardly recognizable. The fire had increased in intensity a great deal in about 15 seconds. When the co-pilot had come out, the flames were coming out under the top turret but when he started to go back in the flames were all over the turret, with intense heat; so he turned around and jumped. The navigator had tried to bring the engineer [Clark] back with him but he [Clark] wouldn’t go through the fire.

The left gunner [O’Brien] heard the alarm bell, fastened his parachute and started for the rear escape hatch, telling the right gunner [Nyholm] to follow him. The right gunner had started to get a fire extinguisher to take up front. The radar officer [Kelly] was in his chute and was fastening on his dinghy when the left gunner got back to the radar room. He told him some one had bailed out of the front and to jump. Two men, the radar and right gunner, were standing behind the left gunner when he jumped.

The co-pilot jumped and pulled the cord when he saw he was clear of the plane. The plane came around in a circle and the whole nose was on fire, flames were coming out of the top and right side of [the] fuselage. After about a ninety degree turn more it blew up before hitting the water.

The co-pilot saw four other chutes below him and just before the explosion another one open quite low and close to the plane, therefore, the co-pilot was certain that six got out of the plane.

Escape:

The co-pilot, navigator, and radio operator bailed out through the front bomb bay. The left gunner bailed out through the rear escape hatch.

Weather:

Visibility was good. The swells were from ten to fifteen feet high. Wind velocity was unknown.

Survival:

Other B-29s which saw the men parachuting out radioed in their position. The survivors had been in the water ten minutes when they saw planes flying low overhead.

A Navy PBY spotted the co-pilot [Hetherington] and dropped sea marker dye and smoke bombs. The co-pilot was in his dinghy approximately two minutes after contact with the water. He paddled about ten feet, got his parachute and dropped it over his dinghy. It was very easily spotted from the air and worked well as a sea anchor. The co-pilot did not drift at all and stayed in the same position as the sea marker dye.

The navigator [Fields] had only his Mae West and had considerable trouble in inflating it. His hands were severely burned, also his head and arms. It took him about thirty minutes to inflate his Mae West. A PBY spotted him and dropped a five man dinghy to him, to which he swam and got into with quite a lot of trouble due to his weak condition.

The left gunner [O’Brien] had his dinghy. He was spotted by rescue planes and smoke bombs and sea marker dye was dropped.

The radio operator [Anderson] did not have his dinghy as it was lost in the fire but he had his Mae West. He was not spotted by any rescue planes. Planes flew directly over him several times. No sea marker dye or smoke bombs were dropped near him.

Rescue:

A mine sweeper had been sent out immediately and a destroyer escort soon after. The mine sweeper arrived at the scene first. It picked up the navigator first who was about five miles from the co-pilot. It then came over and picked up the co-pilot. The radio operator was picked up about 15 minutes later by luck, some one saw something out quite a ways and it was he swimming. The destroyer escort was at the scene by this time and picked up the left gunner.

Although efforts were made until dark to pick up the other men, no one was found. There was considerable wreckage still floating where the plane went down. In the area near the wreckage a number of large sharks were seen.

The two ships stayed out until dark and then the survivors were transferred to the destroyer escort and taken into Iwo Jima so that the navigator could have better medical attention. The mine sweeper anchored in the vicinity of the wreckage and continued search the next day, but no further survivors were found.

Crew recommendations:

More coordination between the planes and ships.

Modification of puncturing mechanism of CO2 cylinders on Type B-4 life preservers.

Use of canopy on raft after person bails out for purpose of easy identification by aircraft; also helps as an emergency sea-anchor.

____________________

Here’s Donald Hetherington’s account of the incident, from History of the 39th Bomb Group. The book’s 1996 publication implies that this account was written in the early 1990s.

On May 4 over Oita, we had some damage to the right wing, close to the fuselage; it was probably from a phosphorous shell. Fire started coming through the radio operator’s compartment. Engineer Harry Clark, Bombardier James Engleholdt, and Navigator Al Fields were attempting to lower the nose wheel with a hand crank and said it had jammed. I hit the alarm bell, called on the intercom to bail out and called to our buddy plane that we were going out. I later assumed that our engineer had turned off the battery and generator switches, as I did not transmit. I said that I would go back and to see if I could get the bomb bay doors open. Radio Operator Clyde Anderson was working on the emergency handles and jumping on the doors. After four or five jumps, the doors opened and he fell out with his one-man life raft on fire. I called out to the crew up front that the doors were open. …

As I stepped into the bomb bay, there was an explosion up front and I was blown out. It apparently popped my chute; I saw the D-ring falling beside me. Hugh O’Brien said when he got to the rear door someone had frozen. Hugh thought if he jumped the rest would follow.

The following would be Missing In Action: Smith Edwards, James Engelholdt, Odie Kelly, Harry Clark, Gerald Arundale, Ernest Nyholm and a tail gunner who’s name I never knew. [Jacobs] He replaced our regular tail gunner James Ogilvie, who had accidentally shot himself in the foot just before going to the gunner’s briefing.

Our buddy airplane saw debris on the ocean and when we did not respond to radio calls, they called Guam and also Iwo and PBY was out to look for us. They spotted me and dropped smoke flares and marker dye. They found Al and dropped him a five-man life raft. He was too weak to get in but could get his arm over the edge. Just before dark, a minesweeper and a destroyer escort arrived. The minesweeper found me then Clyde Anderson in his Mae West. The destroyer escort found Al Fields and Hugh O’Brien. …

We were going to name our plane after the “City of Cooperstown”. Our crew was assigned to the 19th BG by mistake. We were loaded with bombs and ready for Tokyo when orders came down to transfer us back to the 39th. They would not let us fly the mission, as the 39th would get credit for it. Our plane did not come back from Japan so we were lucky once. The second time we weren’t. We were just not meant to fly. My form 5-Flight Record says: one take off, no landings.

I returned to the 60th and was assigned to the 314th Wing as an Air Sea Rescue Officer where I remained until I returned to the States in December 1946. I got promoted in August a day after General Power asked about my rank.

____________________

Akin to biographical information I’ve posted about other 20th Air Force casualties, here’s Major David I. Cedarbaum’s record covering F/O Fields’ casualty status. This document is from the Honor Roll in the Cedarbaum Files (Folder 5) at the American Jewish Historical Society…

____________________

The other Jewish crewman aboard 44-70004 was Corporal Milton Jacobs (35517801), the plane’s tail gunner, who was filling in for T/Sgt. Ogilvie, the latter recovering from an accidental gunshot wound. Ogilvie eventually completed his missions with Replacement Crew 11 – that of 2 Lt. Vincenzo Ricci, of which Jacobs was originally a member.

Milton was born in Czechoslovakia on January 16, 1922. His parents, Henry [6/3/98-1985] and Olga (Breitbart) [1899-1986] Jacobs, and brother Lester, lived at 11609 Hopkins Ave., in Cleveland, Oh. A member of Ohio State University Class of 1947, his name is commemorated on the Tablets of the Missing at the Honolulu Memorial in Hawaii.

His name appeared in a War Department Casualty List released on June 19, 1945, the Cleveland Press & Plain Dealer on June 17, 18 and November 21, 1945, and can be found on page 490 of American Jews in World War II.

This portrait of Cpl. Jacobs was taken when he was simply “Milton Jacobs”. The picture appears in the 1941 yearbook of the Cleveland East Technical High School. It’s from Ancestry.com.

Three or four years later, this picture is from the photo of the Ricci crew.

Here’s Major David I. Cedarbaum’s record concerning Cpl. Jacobs, also from the Cedarbaum Files Honor Roll (Folder 5) at the AJHS.

____________________

Many visitors to this blog doubtless have familiarity with military history in general (…I guess…), and military aviation in particular (…I suppose…), and thus, need no introduction to the Boeing B-29 Superfortress. However, given that nearly eight decades have transpired since the Second World War’s end in 1945, and the seeming lack of even general knowledge concerning that war, its weapons, and tactics in contemporary generations, a few photos and diagrams of the B-29 follow. These shed light on the dire predicament faced by the Edwards crew as they flew above the Pacific Ocean, a little over seventy-six years ago.

__________

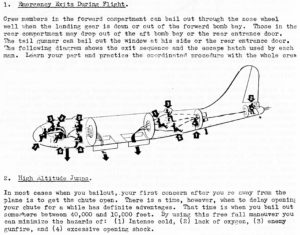

First, this diagram, from the XXI Bomber Command Combat Crew Manual, specifically Section XII – “Emergency Procedures” – depicts the sequence by which the eleven members of a Superfortress crew were to bail out of their bomber during an in-flight emergency. Note that the crew of a B-29 is situated in three separate areas of the fuselage: Pilot, co-pilot, navigator, bombardier, radio operator, and flight engineer are in the nose; behind the plane’s rear bomb bay are three aerial gunners and a radar operator; in the tail, isolated from the rest of the crew, is the tail gunner.

As indicated by this manual, in the nose, the bailout sequence was: 1) bombardier, 2) flight engineer, 3) co-pilot, 4) navigator, 5) radio operator, and 6, pilot. Escape could be made through a hatch in the cockpit floor situated directly above the nose wheel (by definition, necessitating that the nose wheel be lowered), or, through the bomb bay, the latter option requiring that the crew compartment to be depressurized so that the bomb bay could be accessed through a circular hatch.

In the rear, the bailout order was: 1) right blister gunner, 2 left blister gunner, and 3) central fire control gunner. The two remaining crew members – the radar operator and tail gunner – would exit separately. Escape could be made through the aircraft’s entrance door at rear starboard fuselage, or, through the rear bomb bay, either of which which (as per the nose) required that the rear crew compartment be depressurized.

The tail gunner could escape through the same entrance door, or (not too clearly illustrated here) via an emergency escape hatch (in the form of a jettisonable window) on the starboard side of his compartment.

Well, that’s the idea, but there were four unwritten provisos: The crew was largely or entirely uninjured; the plane relatively intact or undamaged; the aircraft in relatively level flight; the plane under control. In this, the bailout diagram is consistent with depictions in instruction manuals pertaining to emergency procedures for other multi-place USAAF WW II aircraft: Whether “ditched” at sea, or in mid-air, the aircraft is illustrated as being entirely intact, with crew members able to nominally carry out their assigned responsibilities. (I don’t know about diagrams in instruction manuals for British Commonwealth warplanes…)

But, even the most cursory review of accounts by crew members of B-29s – let alone other USAAF bombers, such as B-17s, B-24s, B-25s, and B-26s – who bailed out of their planes due to combat damage, or in emergency situations unrelated to battle, reveals that such idealized conditions were far (far) more often the exception than the rule.

Such as, for the Edwards crew.

____________________

Here’s a wartime painting of a B-29 by Norman Dawn, from WW2OnLine, which presents a clear (yet not entirely accurate – I’ll explain why in a moment!) cutaway “view” of the plane’s design, specifically in terms of the crew layout. In front, the pilot and co-pilot sit side by side, with the bombardier (obscured by canopy frames) in the very nose. On the right side of the fuselage and behind the co-pilot is the flight engineer, while behind the engineer is the radio operator. On the left side of the fuselage and behind the pilot is is the navigator. Above the bomb-bay, a pressurized tunnel connects the front and rear crew compartments.

While Dawn’s painting is extremely helpful in illustrating the relative locations of the aircraft’s crew positions, it’s also deceptive, for the dimensions of the human figures in the painting have been greatly diminished in size – deliberately so? – relative to the size of the aircraft, deceptively implying that the crew compartments were far, far (did I say far?!) roomier (and big) than in reality. Another error is apparent in the figure of the crew member moving through the tunnel: Though he’s wearing a parachute, the actual tunnel diameter was – I think – far too narrow to permit this.

Otherwise, regardless of the painting’s degree of (in)accuracy, it depicts a real aircraft; “136954” was the serial number of an actual bomber, specifically, 41-36954 (the first YB-29, the prefix “Y” denoting a test aircraft), which made its first flight on June 26, 1943. Though the plane never flew in combat, it’s correctly shown in olive drab camouflage, which was applied to the three XB-29s (“X “for experimental), all fourteen YB-29s (“Y” for testing), and very early production Superfortresses. You can view an image of the actual plane here. So, I suppose that Mr. Dawn’s painting (was he employed by Boeing?) dates from 1943.

____________________

This illustration is vastly more realistic. From Boeing’s B-29 Maintenance and Familiarization Manuel (HS1006A-HS1006D), this cutaway shows the interior details of a B-29’s forward crew compartment in entirely correct proportion, and, in detail. Immediately apparent from the design in the maximum use of available space for equipment, with room personnel being kept at a bare and functional minimum.

The location of the navigator’s station (Fields’), with its wooden table, is directly behind the pilot. The radio operator’s station (Anderson’s; where the fire began) is opposite, while the flight engineer (Clark would) have been directly behind the co-pilot.

____________________

From TheBestFilmArchives, this film How it Works: The B-29 Superfortress – USAAF Training Film 1944 – provides an excellent overview of the operation of the B-29, primarily from the aircraft commander’s perspective. Particularly noteworthy in the context of this post are the animations showing the crew arrangement, and, the aircraft’s defensive systems.

Several YouTube channels host this particular video, TheBestFilmArchives version being the best of the lot in terms of contrast, lightness, and, resolution.

The particular B-29 featured in the video is aircraft 42-6211, which was delivered to the Army Air Force on October 26, 1943. A very early B-29, it’s notable that the side blisters have bracing frames or multiple panels, and – more obviously – the plane is camouflaged.

This picture of the plane’s tail, taken on December 12, 1943, is from WorldWarPhotos.

The bomber was eventually assigned to the 771st Bomb Squadron of the 462nd Bomb Group, and piloted by Carl T. Hull, Jr., destroyed during a take-off crash at Piaradoba, India, on May 23, 1944.

____________________

____________________

On a note vastly less serious and vastly more pop culture…

The hemispherical multi-panel design of the B-29’s plexiglass nose and canopy was the inspiration for the cockpit of Han Solo’s Millennium Falcon spacecraft in the iconic series of Star Wars movies. (Digression: With the exception of Rogue One – the only good film in the series, and even an excellent stand-alone film – Star Wars is emphatically not science fiction, though it heavily relies on the pop-culture tropes of science fiction, such as “space!”, “aliens!”, and “spaceships!”. It’s really a paper-thin, brightly colored mélange of morally empty “new age” merde indirectly inspired by Joseph Campbell. Digression herewith ends.)

David Cenciotti, of The Aviationist, discusses this aspect of the cultural history of the B-29 bomber at: “Did you know that the Millennium Falcon’s cockpit was inspired by the WWII B-29 Superfortress bomber?“

____________________

____________________

This image, looking forward from the B-29 navigator’s station (as configured in an early production B-29) gives a general impression of what F/O Fields would have seen from his crew position. The work table with its foldable extension is immediately obvious. There’s a small window to the left, fabric lining covering the cockpit walls, while the fabric lined dorsal turret – which was surrounded by flames as the crew attempted to escape from 44-70004 – is immediately to the right.

In terms of the photo’s specifics, it was taken inside B-29A 42-93824 on December 22, 1943, probably (?) at the Boeing factory, given that a hangar door is visible through the window. On September 13, 1944 the plane, assigned to the Combat Crew Training Squadron of the 234th Base Unit, crashed near Clovis Army Air Field, New Mexico, while landing after a training mission. Pilot Captain Jack F. Clark was killed, and his twelve crew members injured.

____________________

Here’s another view of the B-29 navigator’s station (via the National Air and Space Museum) which, in terms of furnishings and equipment, p r o b a b l y has a vastly closer resemblance to F/O Fields’ station in the Edwards’ crew’s 44-70004 than does the early 42-93824. This is likely so because this is the interior of the later production B-29 44-86292, better known as the Enola Gay. While basic components are the same as above, note the presence of the orange-screen cathode ray tube for the plane’s AN/APQ-13 radar indicator.

____________________

To visually sum things up, this panoramic 360-degree-view, at 360Cities, gives a high resolution, clear view of the B-29’s front crew compartment. The view can be adjusted to show the escape hatch in the center of the nose compartment, through which – given that the bomber’s nose wheel wouldn’t fully extend – forced the Edwards crew to exit through the bomb bay.

____________________

Moving from front to rear: Also from the B-29 Maintenance and Familiarization Manuel, this cutaway shows the interior details of a B-29’s aft compartment, where was situated the tail gun position, occupied by Cpl. Jacobs. As tail gunner, he had two means of escape from 44-70004: He could have depressurized his compartment and exited the bomber via the plane’s rear entrance door, or, jumped through the escape hatch created by jettisoning the starboard window at the tail gunner’s position.

But, the Missing Air Crew Report makes no mention of Cpl. Jacobs. Physically isolated from the crew, his fate will forever be unknown.

____________________

This video, from the YouTube channel of SkyJockDS, appropriately entitled B-29 Tail Turret View!, clearly shows the interior of the Commemorative Air Force’s B-29A FiFi (44-62070), with particular attention to the view from the compartment’s side windows. The emergency exit, through which Cpl. Jacobs (could?) have escaped, appears from 0:36 through 0:39. The center of attention is the General Railway-manufactured Pedestal Gunsight, images of of the B-29 bombardier’s version of which can be viewed here.

________________________________________

So much for the aircraft. So much for technology.

And about F/O Fields?

According to the report filed by Major Cedarbaum, he “Jumped through flames; [and was] burned on [his] face”.

The Missing Air Crew Report recounts that his injuries were much more severe; he was, “Seriously injured in action; [with] 2nd or 3rd degree burns”.

But, the true gravity of his injuries is actually revealed – decades later – in a communication by Donald Hetherington to the 39th Bomb Group, in which it was related that the navigator’s injuries were far more grave than indicated in Major Cedarbaum’s report. As described by Hetherington in the History of the 39th Bomb Group, “Al dove through the emergency hatch with his entire flying suit on fire.

“Clyde [Anderson] and I were transferred to the destroyer by Bosun Chair and taken to Iwo. We were evacuated to Guam in about 10 days. The hospital in Guam kept me to assist in caring for Al and keep his spirits up until he was sent back to the States. This was about six weeks.

“He would spend about 3 years having plastic surgery to rebuild his nose, ears and damage to his arms and legs.”

But, even the very little that is known is tragically remarkable, for despite the severity of his injuries (it took a half-hour for him to inflate his Mae West, indicative of the degree to which his hands had been injured), F/O Fields had the presence of mind and willpower to endure until rescue by the Navy just before sunset.

But, Donald Hetherington’s comment about Aldwyn Fields receiving medical treatment until 1948 (!) implies that the two maintained communication for at least a few years after the war’s end.

Alas, his postwar story will probably remain unknown.

(Well, that is merely among men.)

Books, References, Websites, and Other Things

Specific Reference Works

Birdsall, Steve, B-29 Superfortress in Action, Squadron / Signal Publications (Aircraft No. 31), Warren, Mi., 1977

Dublin, Louis I., and Kohs, Samuel C., American Jews in World War II – The Story of 550,000 Fighters for Freedom, The Dial Press, New York, N.Y., 1947

Freeman, Roger A., Camouflage & Markings – United States Army Air Force 1937-1945, Ducimus Books Limited, London, England, 1974 (B-29 pp. 145-168)

Lloyd, Alwyn T., B-29 Superfortress in detail & scale, Aero Publishers, Inc., Fallbrook, Ca., 1983

Mireles, Anthony J., Fatal Army Air Forces Aviation Accidents in the United States, 1941-1945 – Volume 3: August 1944 – December 1945, McFarland & Company Inc., Publishers, Jefferson, N.C., 2006

No Specific Author Listed

XXI Bomber Command Combat Crew Manual, A.P.O. 234, May, 1945 (reprint obtained via EBay)