Given the importance of Passover – Pesach – to the Jewish people, both as a discrete historical event and in terms of its perennial centrality in the arc of Jewish (and dare one say … indirectly world?) history, it’s only natural that this blog presents examples of Pesach observance by Jewish soldiers in a variety of historical settings, and, within the armed forces of different nations. In that light, you can read about military Pesach observance in the following posts:

World War One

World War Two

The Jews of Hawaii in World War Two: The Jewish Exponent, September 10, 1943 (November 10, 2022)

Pacific Pesach – The Guam Haggadah (parts one, two, three, four, and five (references). (January, 2017)

Pesach with the Jewish Brigade: Italy – March, 1945 (May 24, 2018)

The commonality of these posts is obvious: They pertain to Pesach observance by Jewish servicemen specifically in the Allied armies in both wars. While this is so by definition – alas, truly needing no explanation – in the Second World War, in the First World War (the ironically named “Great War”) Pesach was observed by Jewish soldiers serving in the militaries of both the Allies and Central Powers, among the latter most obviously and prominently Imperial Germany. The latter is the topic of “this” post: Passover observance, specifically in terms of the Seder, amidst the horrific Battle of Verdun, during 1916. This was the subject of former Feldrabbiner (Field Rabbi) Georg Salberger’s detailed reminiscence in Der Schild, which was published in April of 1936.

As described at the Leo Baeck Institute – Edythe Griffinger Portal, “Georg Salzberger was born in Culm, West-Prussia (Chełmno, Poland) in 1882 and grew up in Erfurt, Germany, where his father Moritz Salzberger was the rabbi. He studied at universities in Berlin and Heidelberg, and he was ordained rabbi at Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums in Berlin in 1909. From 1910 to 1937, Salzberger was rabbi at the liberal Westend-Synagogue in Frankfurt am Main; he also lectured at the Philanthropin and other Jewish institutions. After incarceration at Dachau, Salzberger emigrated to London, England, where he was co-founder of the German-speaking “New Liberal Jewish Congregation”. Rabbi Dr. Georg Salzberger died in London in 1975.”

Here’s Rabbi Salzberger’s undated portrait from the Leo Baeck Institute: “Part of the Paul Arnsberg Collection, AR 7206; Accession Number F826.” You can also view the portrait via the Center for Jewish History.

As in my prior posts about Der Schild, this posts includes images of the article, followed by an English-language translation, and finally, the same article in the original German. (Unfortunately, the final paragraph, illegible, is absent from this post.) Both versions of the article close with Julius Rosenbaum’s sketch of the crowded Seder, which appeared on page seven of the March 13, 1936 issue of the newspaper – that issue (awaiting translation to English…) being almost entirely devoted to the service and experiences of German Jewish soldiers during the Battle of Verdun. (Not that it mattered in the Germany of 1936, but anyway…)

And so, the Seder of 1916 in the Deutsches Heer.

Pesach Before Verdun

by Kam. Field Rabbi (ret.) Georg Salzberger, Frankfurt a.M.

The Shield

April 3, 1936

Number 14/15

“Oh, this night is certainly different from all other nights,

from those in our beloved homeland with father and mother,

with wife and child,

but also from the nights in the muddy trenches,

in the “bomb-proof” shelter,

at the forward post or during the assault.

War is outside, and here, for one night, there is peace.

Many a tear steals from their eye

when they hear the old melodies here

or when they see the long procession of their ancestors,

heroic, storm-hardened men and women,

pass by in the text of the Haggadah.”

Since February 21, 1916, the beginning of the great offensive, the cannons thundered day and night around the old, defiant fortress. In heroic attacks and counterattacks, the German positions had been pushed forward to the barrier forts: Fort Vaux had been taken after admirable resistance from the French garrison. The German Crown Prince had received its brave commander, a Jewish captain, as we were told, in his headquarters in Stenay on the Meuse and returned his sword to him as a sign of his appreciation. Troops of captured Frenchmen could be seen everywhere. But the hospitals also filled up. Hecatombs of flourishing people were sacrificed in the murderous battles of those days and months; hecatombs succumbed to their wounds behind the front despite the self-sacrificing care of doctors, medics and nurses. In some cases a relatively light injury was enough to cause death within a few days through the development of gas phlegmon.

I had asked the general doctor of the 5th Army, to which I was assigned as field rabbi, to telegraph me when Jewish wounded were brought to a field or military hospital or when Jewish casualties were to be buried. The request was granted wherever possible. I was constantly on the move: in a car, on a truck, on a horse-drawn cart, on foot. In Stenay, where I was based, in Carnigon, in Montmedy, in Longuyon and Pierrepont – to name just the large hospitals – everywhere it was necessary to seek out the wounded, to bring them gifts of love and spiritual support, to accept their wishes and to report back home on their behalf. It is impossible to describe all the torments, but also all the quiet heroism that took place in the houses and barracks. Of course there was no difference between Jew and non-Jew: not in the torments, and not in the heroism for the brave men who lay there in bed next to bed, not for the priest who went from bed to bed. For how many, any consolation and any help came too late! Now here, now there, we lowered a brave man into the foreign earth with the ever moving song of the good comrade; often there were many at once, wrapped in white sheets, whom we buried in the military grave, and then it was not uncommon for the priest or the rabbi to give the funeral oration for all of them.

Under such circumstances, it was not easy to prepare for the Passover celebration. I had obtained an army order from the AOK [Army Higher Command], according to which the Jewish officers and men of all units of the “Crown Prince’s Army”, as far as they were available, were to be sent on leave to Stenay on the first evening of the festival or to Longuyon on the second, in order to take part in the service and the subsequent “religious meal”. The reports came in far more than I had expected, and I was happy that my good boy had brought a hundredweight of ritual smoked meat, generously donated by my home community, from Frankfurt am Main, as well as sizeable packages of matzo and a crate of wine. The director’s office supplied potatoes and canned vegetables. The rooms for the Seder celebration had to be inspected and prepared in a hurry, the meat had to be cooked in a large kashered kettle, the potatoes had to be peeled, etc.

The first evening service gathered in the beautiful church in Stenay about 300 men who had come from the most varied regions, some from far away, through bottomless mud and at the risk of their lives, from the VI, VII and XXII: RK [Reserve Corps] and from the staging areas of Stenay, Dun and Mouzon. In the absence of a Hazzan – the one from the previous year had fallen – I had to take over the office of preacher. The sight of the church filled to the last seat when I then stepped up to the improvised pulpit was overwhelming. The value of memory was spoken of in the sermon, which is presented to us in the three main symbols of the Seder table! As usual, we ended with a prayer and the Kaddish, just as we had begun with the beautiful Dutch prayer of thanksgiving accompanied by the organ; its powerful ending: “Lord, set us free!” was still ringing in our ears when we went to the town’s market square after the tribunal to celebrate the “domestic celebration” together. Because of the large number of participants, we had to do it three times in a row. This meant that not only the meal, which was served from an anteroom, was a little short, but unfortunately also the Haggadah, although I did not fail to explain the signs and customs.

Officers and doctors, as well as 5 Jewish nurses from the nearby Inor epidemic hospital, took part in the first Seder. The second Seder was given by an old family father whose name I no longer remember, the third by the younger son of Rabbi Meyer from Regensburg: It was exactly “around the middle of the night” when the last guests left the room, who had certainly never seen such a strange group together before or since.

The next morning, in the same hall, the comrades who did not have to return to the front held a service among themselves. But I had to drive in the pouring rain, laden with matzo and wine and a mailbag full of Jewish newspapers and magazines in a small car that Major Vogt from the A.O.K. had granted me, via Montmedy and Charency to Longuyon. I unloaded at Levys’s (from Diedenhoefn) sutler’s. I had sent a large crate of matzo and two of canned fruit from Frankfurt by train. The platoon commander, Lt. Colonel V. Schott, who I spoke to, had approved 400 rations of meat and 8 hundredweight of potatoes. At around 7 a.m., around 300 men lined up on the square in front of the town hall. Lt. Sergeant Wanghenheim had them counted and marched to the cinema in four formations. Festively decorated and illuminated, it welcomes our congregation, which includes two officers, several doctors (one of them the late D. Jungmann from Breslau) and sisters from Pierrepont and Longuyon. This time our prayer leader is Hofsanger Platz, who has already performed excellently at the Yom Kippur service in Montmedy. Here I only need to be a rabbi: ancient, proud memories will become an experience for us today – experiences will become memories again, that was more or less the basic idea of my sermon. During a short break, wine and matzah are served, although of course there is only one bottle for one person and one matzah for two people. But there is not a symbol missing from the Seder plate in front of me. And even though everyone only drinks four sips of wine instead of the prescribed four cups, there is still a youngest person there (a member of the Israeli Religious Society in Frankfurt am Main) who asks Ma Nishstana. Oh, this night is certainly different from all other nights, from those in our beloved homeland with father and mother, with wife and child, but also from the nights in the muddy trenches, in the “bomb-proof” shelter, at the forward post or during the assault. War is outside, and here, for one night, there is peace. Many a tear steals from their eye when they hear the old melodies here or when they see the long procession of their ancestors, heroic, storm-hardened men and women, pass by in the text of the Haggadah. The fare is meager, and I cannot blame a humorous comrade for thinking that even the meat today is only symbolic: and yet they all join in with grateful hearts when Dr. S___andi says the grace before meals.

Meanwhile, in the cafe opposite, the 100 men who no longer had room with us had held their own service and Seder. The next morning we all met again in the cinema for a peaceful service with learning, haftorah and musaf. A Mater who experienced it has captured it in his picture. (This picture of the Mater, our Kam. Julius Rosenbaum [of] Berlin, was in No. 11, page 7, D. R.d.)

Pesach vor Verdun

von Kam. Feldrabbiner a.D. Georg Salzberger, Frankfurt a.M.

Der Schild

April 3, 1936

Nummer 14/15

Seit dem 21. Februar 1916, dem Beginn der grossen Offensive, donnerten Tag und Nacht die Kanonen um die alte trotzige Festung. In heldenmütigen Angriffen und Gegenangriffen waren die deutschen Stellungen bis zu den Sperrforts vorgeschoben worden: Fort Vaux war nach bewundernswertner Widerstand der französischen Besatzung genommen. Ihren tapferen Kommandanten, einen jüdischen Hauptmann, wie man uns erzählte, hatte der Deutsche Kronprinz in seinem Hauptquartier zu Stenay an der Maas empfangen und ihm zum Zeichen seiner Anerkennung den Degen zurückgegeben. Ueberall sah man Trupps von gefangenen Franzosen. Aber auch die Lazarette füllten sich. Hekatomben blühender Menschen wurden in den mörderischen Schlachten jener Tage und Monde geopfert, Hekatomben erlagen trotz aufopfernder Pflege von Aerzten, Sanitätern un7d Krankenschwestern hinter der Front ihren Verwundungen. Ost genügte eine verhältnismässing leichte Verletzung, um durch sich entwickelnde Gasphlegmone in wenigen Tagen den Tod herbeizufuhren.

Ich hatte den Generalarzt der 5. Armee, der ich als Feldrabbiner zugeteilt war, gebeten, dass ich telegraphisch verständigt würde, wenn in einen Feld- oder Kriegslazarette jüdische Verwundete eingeliefert wurden oder jüdische Gefallene zu bestatten waren. Nach Möglichkeit entsprach man der Bitte. Ich war ständig unterwegs: im Personenauto, auf Kraftlastwagen, auf Pferdefuhrwerken, zu Fuss. In Stenay, wo ich mein Standquartier hatte, in Carnigon, in Montmedy, in Longuyon und Pierrepont – um nur die grossen Lazarette zu nennen – überall galt es, Verwundete aufzusuchen, ihnen Liebesgaben zu bringen und seelische Aufrichtung, ihre Wünsche entgegen zu nehmen und für sie nach der Heimat zu berichten. Unmöglich, all die Qualen, aber auch all das stille Heldentum zu schildern, die sich in den Häusern und Baracken abspielten. Natürlich gas es de zwischen Jude und Nichtjude keinen Unterschied: nicht in der Qual, und nicht im Heldentum für die Braven, die dort Bett an Bett lagen, nicht für den Geistlichen, der von Bett zu Bette ging. Bei wievielen kam jeder Trost und jede Hilfe zu spät! Bald da, bald dort senkten wir mit dem immer wieder ergreifenden Liede vom guten Kameraden einen Braven in die fremde Erde, oft waren es viele auf einmal, die wir in weisse Laken gehüllt im Waffengrab begruben und dann kam es nicht selten vor, dass der Pfarrer oder der Rabbiner ihnen insgesamt die Grabrede hielt.

Unter solchen Umständen war es nicht leicht, für die Pessachfeier zu rüsten. Ich hatte heim AOK [Armeeoberkommando], einen Armeebefehl erwirkt, wonach die jüdischen Offiziere und Mannschaften aller Truppenteile der „Kronprinzen-Armee“, soweit sir irgend abkömmlich waren, zum 1. Abend des Festes nach Stenay oder zum 2. Nach Longuyon zu beurlauben seien, um am Gottesdienst und am anschliessenden „religiösen Mahl“ teilzunehmen. Weit zahlreicher, als ich erwartet hatte, liefen die Meldungen ein, und ich war glücklich, dass mein braver Bursche einen Zentner rituelles Rauchfleisch, das meine Heimatgemeinde grosszügig gestiftet, aus Frankfurt am Main gebracht hatte, dazu ansehnliche Pakete Mazzen und eine Kiste Wein. Kartoffeln und Gemüsekonserven lieferte die Intendantur. In Eile mussten die Räume für die Seder-Feier besichtigt und hergerichtet, das Fleisch in einem grossen gekascherten Kessel gekocht, die Kartoffeln geschält werden ufw.

Der erste Abendgottesdienst versammelte in der schönen Kirche zu Stenay annahernd 300 Mann, die aus den verschiedensten Gegenden, teilweise von weit her, durch grundlosen Schlamme und unter Lebensgefahr, vom VI, VII und XXII: RK [Reserve-Korps] und aus den Etappenorten Stenay. Dun und Mouzon gekommen waren. In Ermangelung eines Chasen – der vom vorigen Jahr war gefallen – musste ich das Amt eines Barbeters übernehmen. Ueber wältigend der Anblick des bis auf den letzten. Platz gefüllten Gotteshauses, als ich dann an die improvisierte Kanzel trat. Von dem Wert der Erinnerung sprach in der Predigt, die in den drei Hauptsymbolen der Seder-Tafel uns entgegen tritt! Wie zumeist schlossen wir mit einem Gebet und dem Kaddisch, wie wir mit dem schönen Niederländischen Dankgebet unter Orgelbegleitung begonnen hatten; sein kraftvoller Ausklang: „Herr, mach uns frei!“ lag uns noch im Ohr, als wir uns nach dem Tribunal auf den Marktplatz des Fleckens begaben, um dort zusammen die „häusliche Feier“ zu begehen. Wegen der Fülte der Teilnehmer mussten wir es dreimal nacheinander tun. Dadurch kam nicht nur das Mahl etwas zu kurz, das von einem Vorraum, aus serviert wurde, sondern leider auch die Haggada, obwohl ich es an Erklärungen der Zeichen und Bräuche nicht fehlen liess.

Am ersten Seder nahmen Offiziere und Aerzte, auch 5 jüdische Krankenschwestern aus dem nahen Seuchenlazarett Inor teil. Den zweiten Seder gab ein alter Familienvater, dessen Namen ich nicht mehr weiss, den dritten der jüngere Sohn des Rabbiners Meyer aus Regensburg: Es war genau „um die Mitte der Nacht,“ als der letzten Gäste den Raum verliessen, de gewiss weder vor noch nachher eine so merkwürdige Gesellschaft beisammen gesehen hat.

Am anderen Morgen hielten im gleichen Saal die Kameraden, die nicht gleich zur Front zurück mussten, unter sich einen Gottesdienst ab. Ich aber musste, beladen mit Mazzen und Wein und einem Postsack voll jüdischer Zeitungen und Zeitschriften in einem Klein-Auto, das mir Major Vogt vom AOK bewilligte, bei strömendem Regen über Montmedy und Charency nach Longuyon fahren. In der Marketenderei von Levys (aus Diedenhoefn) lud ich ab. Eine grosse Kiste mit Mazzen und zwei mit Obstkonserven aus Frankfurt hatte ich per Bahn vorangeschickt. Etappen-Kommandant Oberstltn. V. Schott, bei dem ich vorgesprochen, hatte 400 Rationen Fleisch und 8 Zentner Kartoffeln bewilligt. Gegen 7 Uhr treten auf dem Platz vor dem Rathaus etwa 300 Mann an. Feldwebel-Ltn. Wanghenheim lässt abzählen und in 4 Gliedern zum Kino marschieren. Festlich geschmückt und beleuchtet empfängt es unsere Gemeinde, unter der sich auch 2 Offiziere, mehrere Aerzte (einer von ihnen der inzwischen verstorbene D. Jungmann aus Breslau) und Schwestern aus Pierrepont und Longuyon befinden. Diesmal ist unser Vorbeter Hofsänger Platz, der sich bereits beim Yom-Kippur-Gottesdienst in Montmedy hervorragend bewährt hat. Hier brauche ich nur Rabbiner zu sein: Uralte stolze Erinnerung wird uns heute zum Erlebnis – Erlebnis wird wieder zur Erinnerung werden, das etwa war der Grundgedanke meiner Predigt. Während einer kurzen Pause werden Wein und Mazzen gereicht, wobei freilich nur 1 Flasche auf 1 Mann und 1 Mazze auf 2 Mann kommt. Aber auf der Sederschüssel vor mir fehlt kein Symbol. Und wenn auch jeder statt der vorgeschriebenen 4 Becher nur 4 Schluck Wein trinkt, so ist doch ein Jüngster da (Mitglied der Isr. Religionsgesellschaft im Frankfurt a. M.), der ma nischstanno fragt. O., diese Nacht unterscheidet sich allerdings von allen andern Nächten, von denen in der lieben Heimat bei Vater und Mutter, bei Weib und Kind, aber auch von den Nachten in den schlammigen Schützengraben, im „bombensicheren“ Unterstand, auf vorgeschobenem Posten oder beim Sturmangriff. Kriegs ist draussen, und hier für eine Nacht Frieden. Manchem stiehlt sich eine Träne aus dem Auge, wenn er die alten Melodien hier vernimmt oder in langem Zuge die Geschlechter seiner Ahnen, heldenhafter, sturmerprobter Männer und Frauen im Texte der Haggada an sich vorüberziehen steht. Schmal ist die Kost, und ich kann es einem humorvollen Kameraden nicht verargen, wenn er meint, auch das Fleisch sei wohl heute nur symbolisch geboten: und doch stimmen sie alle aus dankbaren Herzen ein, als Dr. S___andi das Tischgebetspricht.

Im Cafe gegenüber haben inzwischen die 100 Mann, die bei uns nicht mehr Platz fanden, ihren eigenen Gottesdienst und Seder gehalten. Am nächsten Morgen finden wir alle uns noch einmal im Kino zu friedlicher And____ mit Leienen, Haftoro und Mussaph zusammen Ein Mater, der sie miterlebt, hat sie im Bilde, sein gehalten. (Dieses Bild des Maters, unseres Kam. Julius Rosenbaum Berlin, war in Nr. 11, Seite 7, D. R.d.)

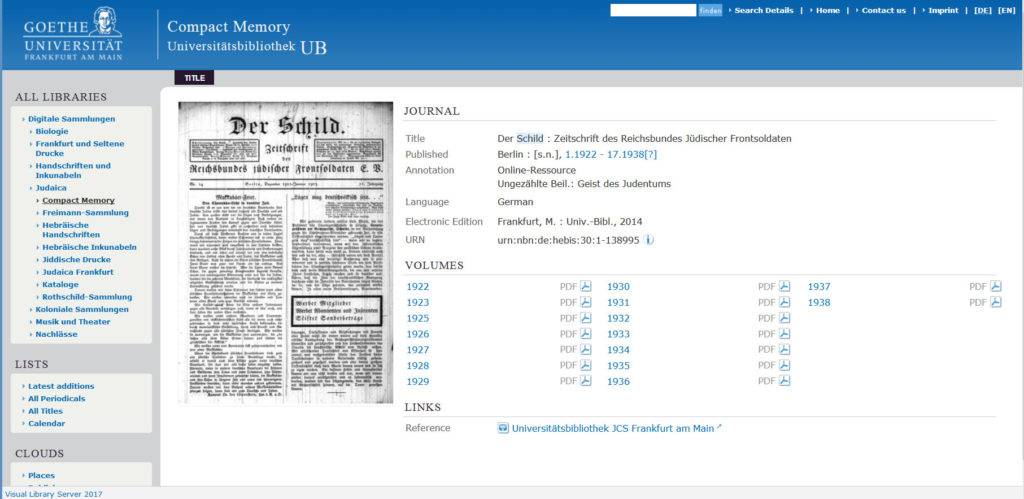

Here’s an overview of how to access Der Schild at Goethe University, excerpted from my post “Infantry Against Tanks: A German Jewish Soldier at Cambrai, November, 1917“, of September 9, 2017. (It certainly seems to have come in handy, just over seven years later!)

“Stories and depictions of World War One combat, composed both during and after the “Great War”, are abundantly available in print and on the web.

“A fascinating source of such accounts – but even moreso a source particularly; poignantly ironic – is the newspaper Der Schild, which was published by the association of German-Jewish war veterans, the “Reichsbundes Jüdischer Frontsoldaten”, from January of 1922 through late 1938, the latter date paralleling the disbandment of the RjF. Der Schild is available as 35mm microfilm at the Dorot Jewish Division of the New York Public Library, and in digital format through Goethe University Frankfurt am Main.

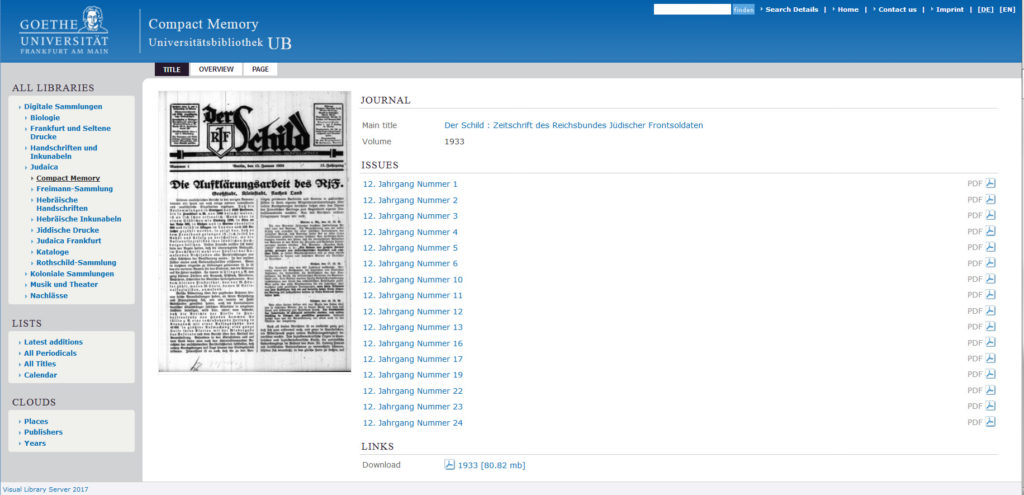

“The screen-shot below shows the Goethe University’s catalog entry for Der Schild, which allows for immediate and direct access of the library’s holdings of the newspaper. All years of the publication, with the exception of 1924, are available; all as PDFs.

“Of equal (greater?!) importance, accessing digital holdings is as simple as it is intuitive (and easy, too!) In effect and intent, this is a very well designed website! This is shown through this screen-shot, presenting holdings of Der Schild for 1933.

“Of equal (greater?!) importance, accessing digital holdings is as simple as it is intuitive (and easy, too!) In effect and intent, this is a very well designed website! This is shown through this screen-shot, presenting holdings of Der Schild for 1933.

“The total digitized holdings of Der Schild in the Goethe University’s collection comprise approximately 530 issues. “Gaps” do exist, with 1922 comprising only four issues (9, 10, 13, and 14) and 1923 comprising three issues (14, 15, and 17). However, holdings for all years commencing with 1925 are – I believe – complete, through the final issue (number 44, published November 4, 1938).

“The total digitized holdings of Der Schild in the Goethe University’s collection comprise approximately 530 issues. “Gaps” do exist, with 1922 comprising only four issues (9, 10, 13, and 14) and 1923 comprising three issues (14, 15, and 17). However, holdings for all years commencing with 1925 are – I believe – complete, through the final issue (number 44, published November 4, 1938).

“Not unexpectedly, Der Schild’s content sheds fascinating and retrospectively haunting light on Jewish life in Germany during the 1920s and 1930s; on Jewish genealogy; on the military service of German Jews (not only in the First World War but the Franco-Prussian War as well), often focusing on Jewish religious services at “the Front”, rather than “combat”, per se (see the issue of April 3, 1936, with its cover article “Pesach vor Verdun”); on occasion about Jewish military service in the Allied nations during “The Great War”(1); on Jewish history, literature, and religion; on Jewish life and Jewish news outside of Germany.

“There is much to be explored.”

References

Bund jüdischer Soldaten (YouTube Channel)

Der Schild (digital version) (at Goethe University Frankfurt website)

Reichsbund jüdischer Frontsoldaten (at Wikipedia)

Vaterländischer Bund jüdischer Frontsoldaten (Patriotic Union of Jewish Front-Line Soldiers”)