“Now that’s what I call a dead parrot.”

________________________________________

I: Anti Antiheroism

As the character of every man is unique, so is the spirit of every age.

The nature of that spirit can be animated by many things; some coincidental, some acting in concert, and some irreconcilable. As for the latter, perhaps most apparent in recent decades has been the clash – a clash lying deep in history and even deeper within human nature – between an appreciation of the past and confidence in the future, and, a world view that finds meaning and power through being relentlessly adversarial, solely and simply for the sake of being adversarial.

In any event, it’s only through the perspective of time – whether years or decades – that the spirit of an age can be understood. So, I think back…

____________________

During my freshman year at Easton College, my course of study involved – like that of all incoming students – a year of English. My first and second semester classes in that subject – both titled “Literary Form and Meaning” – were taught instructors who had very dissimilar teaching styles, and who were equally unlike in the strictness and rigor with which they graded students’ compositions and tests. Despite thee differences, the two classes had a commonality in their approach to literature, and, the body of readings assigned to students. In theme and content, both placed a clear and specific emphasis on literary works centered upon the concept of the anti-hero; the transgressor or questioner of norms; the individual set against mores and social convention. Not necessarily – perhaps? – as a figure to be emulated, but definitely – for certain! – as an individual embodying and symbolizing an alternative, contrary way of understanding, moving within, and ultimately contending with the world.

Or to put it more succinctly, as I remember in the simple phrase of one of my instructors, people who were “knaves and rogues”. People who were antiheroes.

Even now, I remember some of the stories and books that we read.

Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery. Alan Sillitoe’s The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner; very well-written, but astonishingly bleak. Herman Melville’s Bartleby The Scrivener; compelling, but I would prefer not to again read it. Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange. Molière’s Tartuffe. Homer’s Odyssey. Two works of Shakespeare: Henry IV, with a perhaps-inevitable focus on Sir John Falstaff, who I found as tiresome as he was boring. Oliver Twist, with equal time devoted to Bill Sikes and Fagin. (It would be so nice to see an alternative depiction of Fagin, as inspired by Will Eisner’s graphic novel…) Of these eight works (there were others) my favorite was by far the Odyssey; my least favorite (by far; by far) Tartuffe (awful and pretentious); the most disturbing and memorable – and I’m certain intended as such – Burgess’ Clockwork. Did the latter glorify and validate violence, condemn such, or, was it a detached depiction of a society in the midst of self-induced and persisting disintegration fostered by apathy and collectivism? Perhaps it was all of these, and more.

I found the emphasis on this literary theme to be more than odd, but I never broached my puzzlement to anyone. However, as the months passed, even as I was unevenly matched in a sumo-style wrestling-bout with introductory calculus, struggling with chemistry, and gradually reconciling myself to the fact that engineering would never be my forte, and above all trying to navigate other uncertainties (where I felt as if I was blindfolded during an unending eclipse), I soon noticed something:

Given the universal requirement of a year of English for all freshmen, and the inevitably large number of classes needed for so very many incoming students, the suite of required readings – whether novels, novelettes, short stories, or plays – varied somewhat from class to class. But, most (most) English classes, I think, used the same general set of literary works. I suppose the selection of books was made by the college’s English Department, rather than by individual instructors themselves, although with allowance for professors’ literary tastes and preferences. In any case, I soon saw that the required readings in “Literary Form and Meaning” were very different from those of virtually all other English classes. Very.

II: The Flight That Failed

That’s when I took notice of a certain novel, first among the books of my friend R., and second, realizing that this novel was one of the assigned readings of the majority of freshman English students. The author was a man named Joseph Heller. The novel was Catch-22.

I knew a little bit about Catch-22. To be more accurate, I knew “of” Catch-22, the movie.

I became vaguely aware of the film in 1970, via an article in a special edition of Flying magazine (I think it was Flying magazine?) which in either a special edition, or, a special section of a regular monthly issue, displayed photographs of B-25J bombers used in the movie by that name. These images, ground shots and in-flight photos, clearly illustrated the contrived nose art, unit insignia, and simulated armament featured by these aircraft. I don’t remember – and looking back I would not think – that the magazine paid any attention to Heller’s novel in a literary or historical sense, or focused on the movie as an example of cinematography. Then again why would it, for the magazine was aimed at pilots and aviation enthusiasts. Though to be admitted, I was at that time too young to be interested in such things. (Though I did enjoy 2001 A Space Odyssey when I saw it in the summer of ’68. Well, okay, only the scenes of David Bowman, Frank Poole, and Hal the computer. I had no idea why those crazy monkeys were dancing at the film’s beginning, and what that glowing baby and “big black monolith” – as it was dubbed in Mad Magazine’s March 1969 parody, “201 min. of a Space Idiocy” [check it out at the tumblr feed dedicated to Keir Dullea!] – were doing in the fancy hotel room at the movie’s end. Which scene, admittedly, freaked me out. A little.)

____________________

I still possessed that copy of Flying two years later, when I bought the Aurora plastic model company’s 1/48 plastic model kit of the B-25J Mitchell. At the time (we’re talking fifty-two years ago) the kit was the only 1/48 “J” on the market, though Revell did manufacture the “B” in the same scale.

Here are two versions of the box art for Aurora’s kit. The first is, I think, from its initial release in the mid-1950s, and the second from its mid-1960s version.

Via EBay seller blackandwhitemaui1 (not a plug, just giving the source!), here’s the instruction sheet the Aurora kit. Suffice to say this ain’t no Monogram 1/48 B-25J (whether solid or glass nose) or Academy 1/48 B-25B. Not by any stretch of imagination, thought, or sprue.

____________________

A few years after graduating from Easton College, I wanted to learn just why (“Why?!”) Catch-22 had been and continued to be the center of literary attention, to the point where the very expression – c a t c h – 2 2 – had passed into the English language as a figure of speech, seemingly unrelated to Heller’s novel. More (hey, I do like a good story) I simply wanted to read the book. I quickly found a paperback copy in very nice condition at a used bookstore; not too difficult, as new and used copies of the book were then abundant, just as were once physical stores selling new and used books.

Just as were physical stores in general.

Here’s an image of the cover of the novel’s first paperback edition. Note (especially!) the prominent above-the-title placement given to Nelson Algren’s November, 1961 endorsement from The Nation: “…the best American novel that has come out of anywhere in years.” “Wow!” Hey, if the book’s endorsed by The Nation and The New York Times then just as night follows day, it must be good. (The sarcasm is intentional, as you’ll read later.)

I opened the book.

I was fully aware that this was a novel and so – by definition – not a historical work. However, given its setting and time-frame, I nonetheless thought it would provide some degree of insight, however dramatized and fanciful, about WW II and the Mediterranean Air War, drilling down to and focusing on the experience of aerial combat from the vantage point – whether physical, psychological, or intellectual – of the individual aviator. Assuming that the novel was inspired by fact – so I reasoned – suggested to me that at least some elements of historical reality – a changed unit name here; an altered target name there; the details of a pivotal combat mission altered in detail elsewhere – could easily be perceived within its pages. This, coupled with a fictionalized discourse or reverie – or two, or three, or more?! – about such topics as human nature, courage, cowardice, camaraderie (and even humor and absurdity!) from the perspective of by then a quarter-century since the war’s end – would I thought certainly be found in Heller’s writing.

Anyway, it was long. There was bound to be something good within it, somewhere.

So, I started to read it. And then, after reaching a point perhaps 100-odd pages into the novel, I stopped.

I never made my way to the end. I tried. Really, I tried. But, I couldn’t get any further, for to read on would have wasted time that could be more wisely spent elsewhere.

My assumptions about and hopes for the book were wrong. Entirely wrong. Startlingly wrong. Catch-22 was to me as was poor “Polly”, the famed mythical Norwegian Blue Parrot of Monty Python fame, for it ran down the curtain literary and should have long since joined the remaindered inventory invisible. To wit:

This parrot is no more.

It has ceased, to be.

This, is an ex-parrot.

Truly, it was awful.

The novel seemed to violate even the most expansive and generous concepts of plot, theme, organization, brevity versus descriptiveness, and, character development; concepts which I’ve taken for granted from all my prior reading. (For example, the works of WW II veteran James Jones, principally the magnificent novels From Here to Eternity and The Thin Red Line, or Irwin Shaw’s The Young Lions.) Other than being set in the Mediterranean Theater of War in the latter part of WW II, the book was bereft of even the most indirect or tangential historical context, for no sense of place, time, or a larger setting emerged from its pages. For all its length and verbosity – and admitted linguistic cleverness (oh wow, gee, I guess there’s that) – it was jarringly one-dimensional. At the core, the novel was a form of literary self-indulgence: unrefined prose randomly splashed onto its pages as if from a high-pressure fire-hose, lacking a transcendent central message, absent of meaningful character transformation, and above all, bereft of any larger moral and historical insight.

At least, that’s how I felt about it in my early 20s.

I gave it another try some years later; I had the same experience. I grew as exasperated as I had the first time. I know that my literary tastes had by then substantially changed (hey, they’ve changed a helluva lot since), but my aversion to Catch-22 remained.

But about the war, I wanted to read more.

III: On Wings of Words

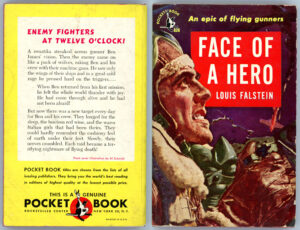

In the mid-1980s, while browsing through the inventory of a used bookstore in a small town in Pensylvania, I chanced across a paperback book – a Pocket Book in near-pristine condition, that – first by virtue of its cover art, and second by the explanatory “blurb” on its rear cover, immediately caught my attention. The book was entitled “Face of a Hero”. Its author was one Louis Falstein.

Here’s the cover of my copy of the paperback:

The book’s origin is explained on the front endpaper:

EVERY WORD of Face of a HERO reads as though it were written on the spot. When you finish this book you will know that this was the way it was 20,000 feet in the air with enemy planes attacking from all sides. For Louis Falstein, like his novel’s hero, Ben Isaacs, was there. As an aerial gunner with the Fifteenth Air Force, Mr. Falstein won a Purple Heart, four Air Medals, and nine battle stars.

Face of a Hero is Louis Falstein’s first novel. It was originally published by Harcourt, Brace & Company.

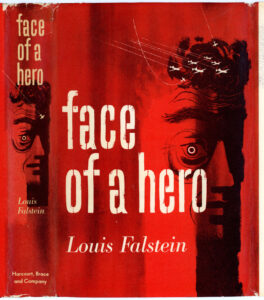

I bought the book, but I was unable to actually read it, for I didn’t want to risk damaging it in light of its (then) nearly fifty-year fragility. Instead, I purchased a copy of the Harcourt, Brace 1950 hardcover first edition from a specialty used bookseller. That copy I read, and read twice.

Here’s the jacket:

Here’s Louis Falstein’s 1950 portrait by “Arni”, featured inside the book’s jacket…

I thought that Face of a Hero was excellent.

I think it remains so.

I read the novel from three perspectives: Simply as a work of diversion – of fiction, for fiction’s sake; to gain an understanding of WW II aerial combat from the vantage of an enlisted man serving as an aerial gunner; to see what perspectives and insights could be availed from a Jewish aviator flying combat missions against Nazi Germany, given the nature and ethos of the Third Reich. As for Catch-22? By the time I read Face of a Hero, Hell’s novel had – in contemporary parlance – long since “fallen off my radar”. Far, far, off. Well, the “scope” had been turned off years before.

Thirteen years later, in April of 1998, both novels came to public attention as a result of an inquiry to the Sunday Times of London by one Louis Pollock, inquiring whether, as his letter was quoted in the Chicago Tribune, “…anyone could account for the amazing similarity of characters, personality traits, eccentricities, physical descriptions, personnel injuries and incidents” among the two novels. Pollock’s question was addressed by Michael Mewshaw in the Washington Post, Mel Gussow in the New York Times, and Sanford Pinsker in The Forward. It was also touched upon in biographical retrospectives of Joseph Heller published in the two “Posts” (that of Washington, and, Jerusalem) just after that author’s death in December of 1999.

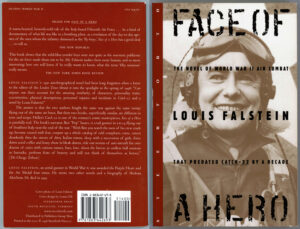

I think this controversy was at least the partial impetus for Steerforth Press’s 1999 reissue of Face of a Hero in trade paperback format…

…the cover of which appears below:

The novels do parallel one another on first glance. Both stories are set in the Mediterranean Theater of War in the final years of WW II. Sergeant Ben Isaacs, Falstein’s protagonist, is a Jew and an aerial gunner on B-24 Liberator bombers in the 15th Air Force. Heller’s Captain John Yossarian, a bombardier of distant Assyrian heritage, serves on B-25 Mitchell bombers in the 12th Air Force. However, despite these superficial similarities, and other aspects of the two texts, the novels really are utterly different in terms of style, overarching plot, theme, character development, and especially the perception, role and fate of the protagonist (and even secondary characters) in a larger historical context.

Beyond the different nature of the novels as literature, the literary and cultural fate of the two books has been dissimilar to a degree so vast as to be… Well, how sounds the word “absurd”? Despite positive reviews in The New York Times, the Washington Post, The New Republic, and glowing comments in other newspapers and periodicals, Face of a Hero fell into an obscurity from which it was only lightly and temporarily revived in the Steerforth Press edition. Catch-22 has experienced a fate vastly different: Whether as a novel, a film, a television (mini)-series, or an expression that has become part of contemporary language, culture, and thought, Catch-22 and “catch-22” live on.

But, this series of posts is about Louis Falstein and Face of a Hero.

More, to follow…

A Few References…

Falstein, Louis, Face of a Hero, Harcourt, Brace & Company, New York, N.Y., 1950

Falstein, Louis, Face of a Hero, Pocket Books, Inc., New York, N.Y., 1951

Falstein, Louis, Face of a Hero, Steerforth Press, South Royalton, Vt., 1999

Heller, Joseph, Catch-22, Dell Publishing, New York, N.Y., 1968