“And we must remember that this book was written not as a historical record for ourselves, but primarily as a weapon against anti-Semitism.”

* * * * * * * * *

“Curt Riess, who has done much literary introduction of late, adds to the general confusion by proclaiming that to think of Jews “as a group is not logically justifiable”. According to him Jews are “not a nation, not a religious community, not a race. Furthermore, Zionists form only a relatively small percentage of all Jewish people in the world.” Mr. Riess also recommends that the book should be widely read. The reviewer disagrees.”

____________________

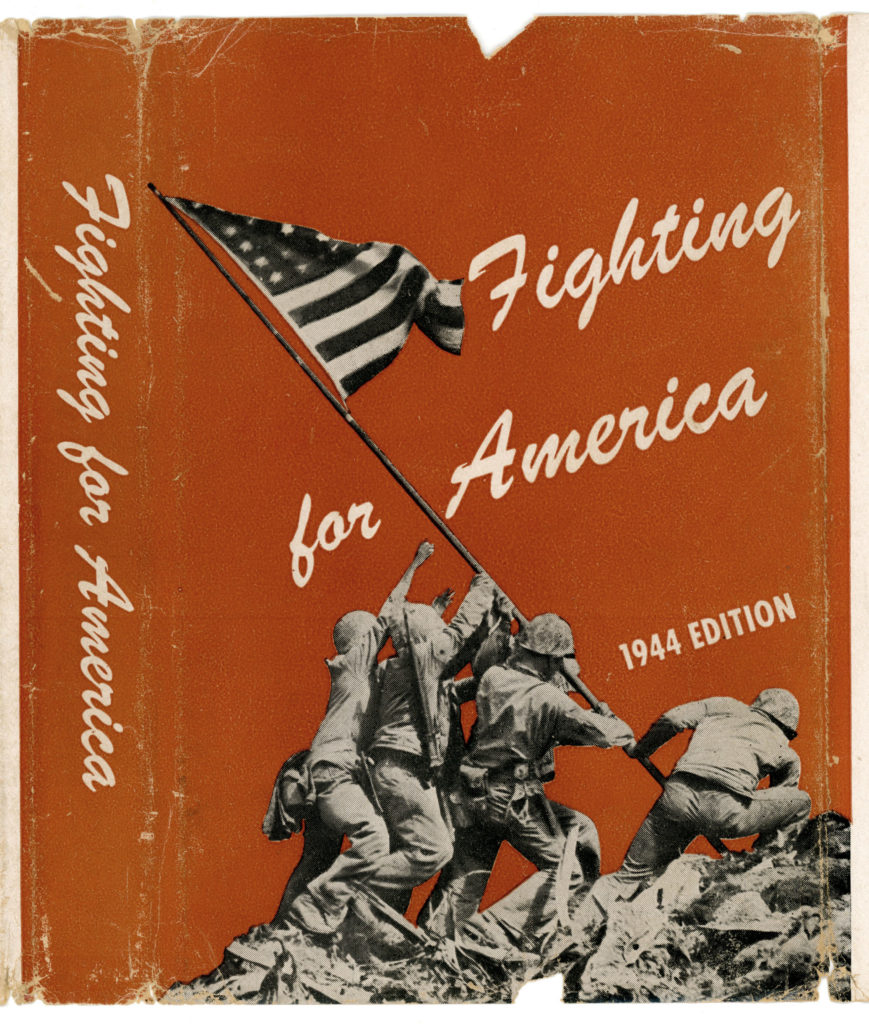

This item is a dual book review from late 1945 by Abraham G. Duker, covering publications dealing with Jewish military service. The first book – Fighting For America – 1944 Edition, covers Jewish military service in the United States’ armed forces during the Second World War, based on information gathered by the Bureau of War Records of the National Jewish Welfare Board through that year. The second, The Fighting Jew, presents a historical overview of Jewish military activity and participation from (as can be understood from the review) as far back as the Bar Kochba Revolt of 132-135 (or, 136) C.E., while primarily emphasizing the modern era and contemporary times.

While Abraham Duker’s brief review of Fighting For America could be deemed skeptical but appreciative, his opinion of Ralph Nunberg’s book is – charitably phrased – highly dismissive.

Regardless of the books’ differences in content and style, and the lack of historical accuracy of the latter (!), a shared quality of the works would seem to have been the imperative of validating the bravery and patriotism of Jews, within both the immediate (WW II) and long-term historical context. As such, and as correctly perceived by Duker regarding Fighting for America, one (not the only) purpose of that book was to refute antisemitism. (Of course, this would have been based on the erroneous assumption that antisemitism is amendable to refutation by logic and reason, in the first place…)

Duker is correct in deeming these works to be part and representative of Jewish “apologetic literature”, examples of which most strikingly appeared during and after the First World War, some even appearing in Germany amidst the Franco-Prussian War. Regardless, the information amassed in at least some such books – which have varied tremendously in terms of comprehensiveness, style, and physical format – is still historically valuable.

I would take issue with Duker’s implication that the lack of a publication covering American Jewish service in WW I, was due to the fact that the impetus to create such a book did not exist at that time – in the late ‘teens and through the 1920s – among American Jewry. Actually, it did. Certainly, more than sufficient information had been amassed by the Office of War Records of the American Jewish Committee, that could have eventuated in such a publication, perhaps as multiple volumes. That it was not produced – that the project seems to have been “shelved” – was, I would suggest, due to the tenor of the times: Amidst overlapping currents of economic and social uncertainty, and worse, much of American Jewry – at least, as perceived, influenced and led by its ostensible, nominal, de facto leadership – adopted a survival strategy of collective self-effacement.

In any event, regardless of the impetus behind its creation, Fighting for America and its related and larger 1947 two-volume publication, American Jews in World War Two are valuable (albeit highly incomplete) reference works.

____________________

FIGHTING FOR AMERICA, A Record of the Participation of Jewish Men and Women in the Armed Forces During 1944, New York, The National Jewish Welfare Board, 1944, 290 pp.

THE FIGHTING JEW, by Ralph Nunberg. With an Introduction by Curt Riess. New York, Creative Age Press, 1945, 295 pp.

A significant index of the status of the Jews in the world today, their fears and uncertain view of their own future, is the relatively large number of publications on the subject of Jews and military prowess, two of which are here examined. Fighting for America is reminiscent of similar volumes published by Jewish communities in Europe, Africa, and Australia following World War I. The fact that no such publication appeared in the U.S. at that time, and that American Jewry is the first to produce one after World War II, is in itself an indication of the spread of this type of apologetics, whose effectiveness has been amply tested in the crematoria of Europe.

A significant index of the status of the Jews in the world today, their fears and uncertain view of their own future, is the relatively large number of publications on the subject of Jews and military prowess, two of which are here examined. Fighting for America is reminiscent of similar volumes published by Jewish communities in Europe, Africa, and Australia following World War I. The fact that no such publication appeared in the U.S. at that time, and that American Jewry is the first to produce one after World War II, is in itself an indication of the spread of this type of apologetics, whose effectiveness has been amply tested in the crematoria of Europe.

Fighting for America is an incomplete record of the heroism of Jewish members of the armed forces. It is incomplete because unlike Catholics, “Americans of the Jewish faith” do not take their religion or community adherence seriously enough to establish a unified system of records of births, marriages, and affiliation. The Jewishness of Sam Levine, Bernard Shapiro, or Norman Friedman is beyond doubt in most cases. A student of Jewish history will easily spot the Sephardic Abe Condiotti. He will hesitate before identifying Gilbert Stein, Lou Charles Lerner, or Harold Monash. But it takes much research to identify as Jewish names like Bertram N. Sheff, Martin Rockmore, Morris Saunders, John Stark, or George J. Smith. The Welfare Board’s Bureau of War Records has done it in these cases; more power to its staff.

____________________

Lt. Abraham Condiotti, as seen in the Philadelphia Bulletin of June 8, 1944. An article about him appeared in The New York Times on the same day. Strangely, though a brief account of his deeds on D-Day appeared in Fighting For America – 1944 Edition, his name never appeared in 1947’s American Jews in World War Two.

Lt. Abraham Condiotti, as seen in the Philadelphia Bulletin of June 8, 1944. An article about him appeared in The New York Times on the same day. Strangely, though a brief account of his deeds on D-Day appeared in Fighting For America – 1944 Edition, his name never appeared in 1947’s American Jews in World War Two.

____________________

Apologetics or no apologetics, it is still nice to know that the Jews have done their bit in this war for America. They have contributed their share in all branches of the service; for instance, 40% of all the Jewish physicians in this country were members of the armed forces. That such enthusiastic participation may be misjudged can be attested by the talk so frequently heard in the barracks that “the Jews have all the easy jobs”. In addition to lists of decorations and citations, the volume includes ample examples of heroism on the part of men and women, including members of the commonly scoffed at Chaplains’ Corps, whose achievements on behalf of interdenominational amity are emphasized. More should have been said, however, about what the chaplains have done for the “displaced” Jews, a story which puts many a respectable relief organization to shame. But the “public relations” angle places achievements on behalf of Jews last on its list. And we must remember that this book was written not as a historical record for ourselves, but primarily as a weapon against anti-Semitism.

***

The Fighting Jew is a hurriedly composed yet well written pot boiler of facts and fiction, put out in an effort to prove that the Jew is not a coward. It is evident that the author is not a student of Jewish history. Otherwise he would have included the Khazars, Berek Joselewicz, and members of Hashomer, and a host of other Jewish warriors. Had Mr. Nunberg stuck to his subject without wandering off to discuss problems, social and historical, which he is manifestly incapable of handling, and had he, in addition, taken care to do some serious research and check his data, a decent book for juveniles might have emerged. As it is, this volume contains too much misinformation. And it is a pity, for its author can do good popular writing.

The book begins with a justifiably gruesome description of life in the Warsaw ghetto, regrettably, culled from second-hand sources. The Polish underground’s distrust in the Jewish capacity to fight, rather than ordinary anti-Semitism, is given as the reason behind the Polish refusal to supply the Jews with arms. Klepfisz, a truly heroic figure, is melodramatized as almost the sole leader of the resistance, to the extent that the author puts in the mouth of the ghetto defenders the question whether “this Michael Klepfisz might not be one of the tribe of David, the Messiah, whose coming had been promised to the Jews for their hour of greatest need.” Melodramatic suspense is created by making the reader wait till the end of the volume for the outcome of the struggle, while the book turns to ancient history. The Biblical period is disposed of in one page. The Maccabeans rate but three quarters of a page. No chronology is given.

This is followed by a fifteen page thriller of the revolt against Rome and the destruction of Jerusalem. Errors abound. Nunberg makes the completely unjustified assertion that following the Bar Kokhba revolt, Jews no longer went “to battle for a Jewish cause or [did they] die for the survival of the Jewish nation… Now they fought for whatever country had become their home.” This, by all rules of logic, should have excluded much of the subsequent material. But the author, unimpressed by his own generalizations, deals albeit too sketchily with the subsequent revolts against Rome and Persia, the Jewish kingdom in Yemen, and the wars against the rising Mohammedans.

A major portion of the book is devoted to America, the “promised land”. The author’s grasp of seventeenth century conditions is indicated in his statement that Jews resented the fact that “Dutchmen, Frenchmen and Englishmen” had been “forbidden to settle in New Amsterdam just because they were Jewish”.

In his treatment of “the fight for equality” in Europe, the arduous course of emancipation is sophomorically simplified. Napoleon is described as a man “who gave much thought to the Jewish problem,” and a lion’s share of space is given his general, Andrea Massena, the Duke of Essling, whose Jewish origin is still a matter of speculation and who never identified himself as a Jew religiously. The Dreyfus case, where there is no shadow of suspicion of martial accomplishment, is treated as background to a brief story of Herzl and Zionism, which in turn is woven into a presentation of Jewish heroism in World War I. Jewish self-defense in Palestine in 1936 is discussed without mentioning its national and social motivation, typified by the policy of Havlagah (self restraint). The word Haganah is not in the index.

Following a greatly simplified and rather inaccurate picture of political events which preceded World War II, the author devotes a chapter to the prowess of Jews in that war, with Russian and American Jews receiving most attention. Much more could have been added. Nevertheless this chapter is the best in the book, which ends with a description of the final resistance of the Warsaw ghetto.

Curt Riess, who has done much literary introduction of late, adds to the general confusion by proclaiming that to think of Jews “as a group is not logically justifiable”. According to him Jews are “not a nation, not a religious community, not a race. Furthermore, Zionists form only a relatively small percentage of all Jewish people in the world.” Mr. Riess also recommends that the book should be widely read. The reviewer disagrees.

– Transcribed 2014