The Germans (The Luftwaffe)

The identity of the Luftwaffe unit that sank the Erinpura is revealed in Norman Clothier’s excellent account as Kampfgeschwader (“Bomber Wing”) 26. The sinking of the ship is described thusly:

“In the late afternoon of 1 May 1943 the convoy was in six columns on a westerly course not far from the North African coast. The first warning of air attack came at 18:43 [6:43 P.M.] when a single aircraft approached the convoy out of the sun. Flying at about 50 feet (15 m) above the sea it flew between the starboard line of escorts and the convoy, so that only two ships were able to engage it. Apparently no hits were made. Reports differ as to whether it released a torpedo or jettisoned something, but no ship was hit. This aircraft retired to the north-east pursued by shore-based fighters who claimed to have destroyed it. It would have been able to report the convoy’s position by radio before it was shot down.

“Shortly after 19:10 [7:10] another plane attempted to repeat the same tactics, but it was driven off by fire from the escorts. Retreating to the north-west it, too, was pursued and destroyed by fighters.

“Finally the main attack commenced at 19:50. [7:50] A German source (“Dr. Phil Ernst Thomsen who took over the command of III / KG 26 in 1944.”) says that it was made by two Gruppen (equivalent squadrons), III / KG 26 under Major Nocken and II / KG 26 led by Major Werner Klumper, who also commanded the attack as acting wing commander. British estimates of the number of attackers vary from 18 to 36. The lower figure seems to be more probable. The attack was synchronised by two groups so as to confuse the defence. British reports differ. Apparently the first attack was made by bombers. Ships in the convoy twisted and turned to avoid the falling bombs and no hits were made. All vessels were firing their anti-aircraft weapons. At the same time a Heinkel 111 was seen to drop a torpedo about a mile from the convoy, later a flash was seen and an explosion heard. The tanker British Trust was hit, her port side was opened for a third of her length and her cargo of oil caught fire. She listed heavily and sank in about three minutes. No boats could be lowered and difficulty was experienced in getting rafts clear, but her crew, mainly Indian lascars, behaved very well and many survived to be picked up.

“The action intensified at about 20:10 [8:10] with many bombers overhead, the guns of the convoy and escorts firing furiously and the scene partly lighted by the burning oil from the British Trust. At this time fighters were probably overhead attacking the bombers, as shore command claimed that it had three Spitfires, eleven Hurricanes and a Beaufighter airborne very quickly.”

There is a plethora of material covering the history of KG 26, attributable to its lengthy (1939 through 1945) service, and, participation in combat on every European front.

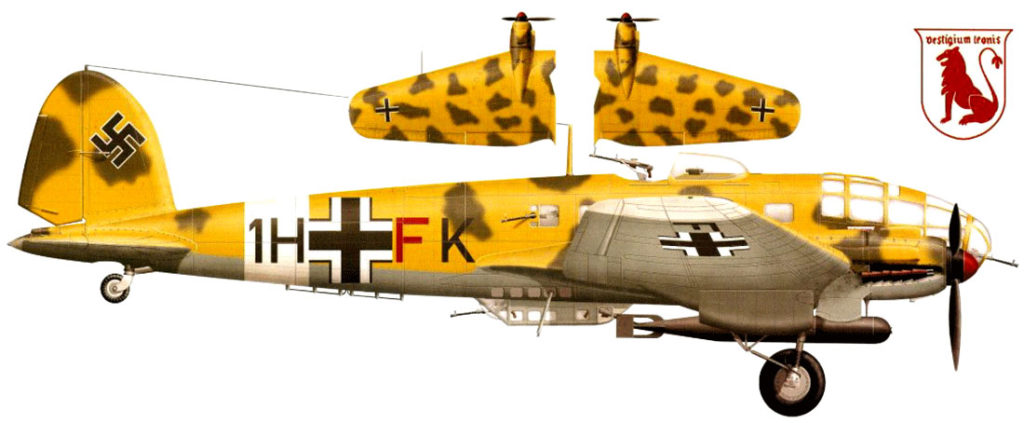

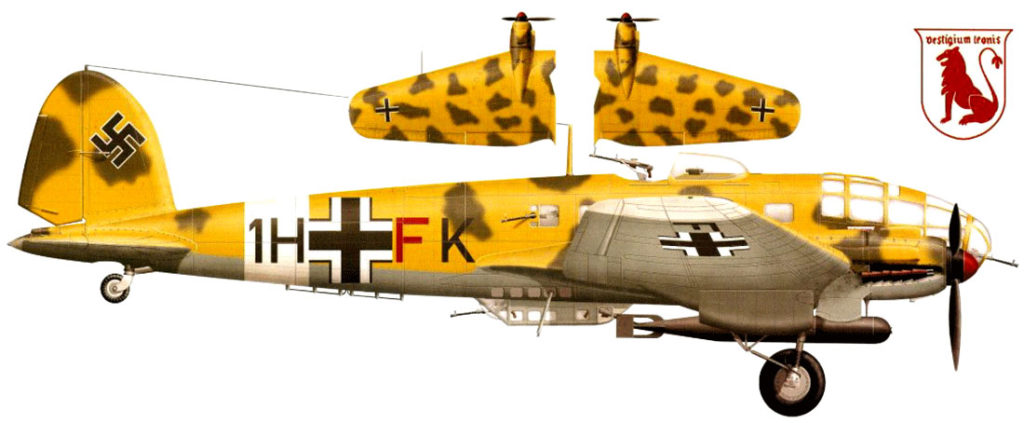

The Kampfgeschwader was equipped with He-111, Ju-88, and eventually Ju-188 aircraft, all these aircraft being twin-engine medium bombers which were decorated with the Geschwader’s emblem of a stylized lion beneath the motto “Vestigium Leonis” (“Winged Lion”). During its service, KG 26 incurred the loss of 341 aircraft (271 He-111s, 12 Ju-188s, 1 Ju-52, 56 Ju-88s, and 1 Bf-108). II / KG 26 and III / KG 26, the specific units which sank the Erinpura and British Trust, are abbreviations for II Gruppe and III Gruppe (2nd and 3rd Groups) of the Kampfgeschwader.

Color profile of a desert camouflaged He-111H, bearing the insignia of KG 26, from the Wings Pallette website, by Zygmunt Szeremeta. The alpha-numeric code “1H” identified the Geschwader’s aircraft.

Color profile of a desert camouflaged He-111H, bearing the insignia of KG 26, from the Wings Pallette website, by Zygmunt Szeremeta. The alpha-numeric code “1H” identified the Geschwader’s aircraft.

The nose of a Heinkel He-111H of KG 26 in North Africa, from the Asisbiz website. The aircraft is finished in the Luftwaffe camouflage color “RLM [Reichs Luftfahrt Ministerium – “Ministry of Aviation”] 79 Sandgelb”.

The nose of a Heinkel He-111H of KG 26 in North Africa, from the Asisbiz website. The aircraft is finished in the Luftwaffe camouflage color “RLM [Reichs Luftfahrt Ministerium – “Ministry of Aviation”] 79 Sandgelb”.

Another He-111H of KG 26, also in North Africa, from the waralbum.ru website. Notable in this view is the aircraft’s nose-mounted 7.9 mm machine gun.

Another He-111H of KG 26, also in North Africa, from the waralbum.ru website. Notable in this view is the aircraft’s nose-mounted 7.9 mm machine gun.

During the time of the sinking of the two ships, II / KG 26 was based at Villacidro, Sardinia, and equipped with He-111H-4/6 torpedo bombers, while III / KG 26 was based at Grosseto, Italy, and equipped with Ju-88A-4 dive bombers. KG 26 was then commanded by Oberstleutnant (Lieutenant Colonel) Werner Klümper. The commander of II Gruppe was Major George Teske, while III Gruppe was commanded by Hauptmann (Captain) Klaus Nocken, who, according to Norman Clothier’s references, was killed in Prague in 1945.

Though the above report mentions that shore-based RAF fighters destroyed two of KG 26’s bombers during the strike on the convoy, and possibly the aircraft that initially spotted the convoy, the list of KG 26 losses implies that this was not so.

Unfortunately, the Kampfgeschwader lost no aircraft that day.

The entry on the Erinpura at Hebrew Wikipedia states that the convoy was identified by a German Storch (“Stork”) type aircraft, most likely an allusion to the Fieseler Fi-156 light observation and army cooperation plane. However, performance figures for the very lightly armed Fi-156 state that the aircraft’s range was 240 miles, vastly short of the distance between the Erinpura’s convoy and German air bases in Sardinia and Italy. Thus, the convoy was more almost certainly spotted by a He-111 or Ju-88. This is also consistent with the accounts given by Norman Clothier and Henry Morris.

Curiously, the accounts given by Henry Morris and Norman Clothier differ by exactly one hour in terms of the timing of the bombing of the Erinpura. Henry Morris gives the start of the main attack as 20.50 (8:50 P.M.), with the ship being struck by a bomb at 21.05 (9:05 P.M.). Norman Clothier gives the start of the main attack as 19.50 (7:50 P.M.). In any event, KG 26’s strike was obviously timed to coincide with sunset, which – on May 1, 1943, near Benghazi – occurred at 21:19 (7:19 P.M.).

Aboard the Erinpura

The Palyam and Aliyah Bet Website provides a document in Hebrew entitled (English Translation) “Yishuv Volunteers For the British Army During the Second World War 1939-1945“, which specifically focuses on the sinking of the Erinpura, and includes eyewitness accounts of this event and its aftermath, by three survivors: Chaim Ast, Ben Ami Melamed, and Eli Zeiler. The translated document (a somewhat approximate translation) is presented below:

Chaim Ast was sailing for three days on the Erinpura without knowing where he was going. The sun rose and fell over the Mediterranean waters. The waves surged and subsided frequently, but Ast and members of the 462nd were only able to guess where they were going. Since leaving the port of Alexandria, the company commander, Major Yoffe, would say nothing. Members of the company had lost the sense of time and place. Only the celebrations on the first of May involving a prescribed routine hinted at something on the calendar.

“That day at dusk, with Prof. Eisenberg and one of our officers, we gathered on the upper deck,” recalls Ast, with wandering eyes. “Until then we sailed without knowing where we were going, and, there was an air of uncertainty. Eisenberg called us; told all of us first of the 1st of May and its meaning, and then the purpose of our cruise – to embark in Malta for the invasion of southern Europe. Below the deck, the socialists were celebrating, and while he was talking, a plane passed overhead. After that I went down. We had long tables with benches and sat and talked. Suddenly came the bombing.”

…south to Al Alamein:

When the 462nd Company was established, way back in 1942, Eli Zeiler was a young teenager who wondered around the open spaces surrounding Degania Alef. While he was walking in the fields, the British were training a group of Israeli soldiers that were designated to act alongside her majesty’s army, in battles that were beginning throughout the world at that time, as one of the four Hebrew transport platoons. For Zeiler it was a golden opportunity for closure.

“I was born in Austria, and in 1938 my high school classroom teacher ordered all Jews to leave. So I left,” he recalls. “I moved here straight to the kibbutz and soon after that I decided to join. The Histadrut wanted to send me a commanders’ course of ‘defense’ and refused to enlist me in the British army, so I bypassed them and applied directly through the Army recruiting office. I received a pound and a half, and I took a bus to Sarafand, the “Zerifin” of today”.

Among the people he met in the company, were Ben Ami Melamed and Chaim Ast; old friends ever since elementary school, and decided to join the same company. More than 60 years have passed, but when the three of them met this week in Ast’s apartment, the memories of those early days as fighters returned quickly. “The atmosphere was such that anyone who joined the British was an evader”, was Ast’s opening line. “I left everything, I recruited five more fighters with me and we went together to enlist in the British Army. I went straight to the front, to El Alamein”.

The transport company received full infantry training and learned to drive on primitive roads. Thereafter, recruits from the battle of El Alamein joined the expanding front where Italian-German forces commanded by Rommel were quickly advancing. “The Germans arrived, and it was a real threat. We felt it would be a shame for the Germans do to us what they did to all the Jews,” recalls Melamed. “The feeling was not easy when we got to the front. We knew that if the Germans would break the El Alamein line, they would conquer Egypt and then will come our way to Israel.

I don’t remember who said this but we decided that in case of a retreat, we would abandon the British army and go to Israel by trucks. While preparing for battle, the transport platoons were busy paving roads. During the battle days, Aset, Melamed, Zeisler and their friends would go into the lines of the infantry squads.

While preparing for battle, there were detachments of transports especially in road construction. On the days of battles Ast, Melamed, Zeiler and friends would go into lines classed as infantry. On other days they would transfer equipment to one point and come back with prisoners to another point. This situation often gave rise to complex situations. “When the distances became longer, one day wasn’t enough to transfer the prisoners so we had to spend the night with them”, Zeisler says. “The problem was that one driver and one infantry soldier can’t really guard 30 prisoners of war, so we invented a game – Find the shoes. We had them take off their pants and shoes, and walk them 200 meters into the desert, and that way we could ensure ourselves that no one would escape without their belongings. For some fun, we would make a big pile of all the shoes – for them to search.”

In October 1942, the winds began to warm at El Alamein. The British Eighth Army, under the command of Montgomery, began to chase Rommel’s forces and lead what is considered by many as the turning point of World War II. “When we were chasing the Germans, we were moving forward so quickly that we couldn’t stop,” recalls Ast. “The trip had become dangerous. Ben-Ami, who was the co-driver of mine, was observing out of the truck, dismantling plugs from abandoned German trucks and replacing them while we were driving. That’s how we moved forward. At last when the enemy lines were finally breached, we entered the most terrible battle area. The bodies of soldiers were strewn everywhere. I remember this image like it was yesterday, but most of all – I can not forget the smell.”

Idiots, jump into the sea!

After the battle in North Africa ended the transport platoon together with other British army forces went towards Alexandria. Scenting the smell of victory, Melamed, Zeisler and Aset embarked with the rest of their friends on the British ship the “SS Erinpura”. On the 29th of April of that year, at the end of Passover, the first convoy left with as a naval force of 27 ships carrying soldiers, supplies and equipment for the British army.

The goal of the journey was to reach Malta and join the forces that were meant to participate in the allies invasion of Sicily. However the Germans had other plans. “On the 1st of May at dusk, while the convoy was making it’s way by sea, about 50 kilometers north of Benghazi, Libya, a German reconnaissance plane came from the west was flew over our heads”, describes Zeisler. It came right out of the sun so we couldn’t see it approaching, and passed between the ships at the same height of the decks. So it was impossible to open fire on him, so as not to hit the other ships. After it flew away, it was very clear that an attack would begin”.

And of course around 20:00, 12 German warplanes came over the convoy of ships, focus on the lead ship in the convoy – the Erinpura. “They hit our ship in 2 places – one straight in the hold and the other from the side,” Ast mentioned.

“This is a moment that I do not remember. I ran towards to the stairs but did not find them. I somehow got to the upper deck, and as I came up, I met a friend there. He saw the water getting closer and started to cry. I did not have too much experience in water, but I heard that when something is sinking it causes a whirlpool. I said, ‘You are not a woman on the beach in Tel Aviv, jump! He did not want to, so I pushed him and jumped after him. I saw that the bottom floor collapsed, and the stairs collapsed. The ship began to descend like an elevator,” says Zeiler. “She started to tilt angle of 45 degrees. When I managed to stay away some ten meters by swimming, I saw the propeller rise, and there was a huge explosion, apparently in the engine room.”

Melamed himself was secluded in a room at the back of the ship and rushed up to the top deck. “I saw two guys standing and throwing rafts,” he says. “I came to help them and I saw the side of four guys sitting and praying. I saw that the ship was going to sink and I realized there was no choice and had to jump into the sea. Suddenly the rear of the ship rose into the air and the water was already upon us. I called to them, ‘Idiots, jump into the sea!’ And they continued to pray. I jumped and started to swim with all my strength to stay away from the ship. Her horn blared very long, and then I turned around and I saw her descend with them into the water. It was a picture of horror: the bow turned forward and on the aft hung dozens, if not hundreds of soldiers. Terrible screams. I threw my belt I minded and I swam with all my might. I turned back again – no vessel, no people, everything was gone, and the Germans firing at us with bursts of gunfire.”

The Erinpura sank in less than four minutes. Melamed, Zeiler and Ast found themselves in the icy darkness of the Mediterranean. Time passed, and more. Gunfire was replaced by a soft throbbing sound. Greek naval forces in the occasional darkness trying to find the survivors. “I saw two rafts and began to gather more and more people, of all nations, on them” says Melamed quietly. “South Africans, British and Indians. Most of the people who lived, were on the raft floating in the water. We decided all together, without knowing the languages, that only the wounded will remain on the rafts. A Greek destroyer approached, and when I grabbed the ladder I saw that I could not continue because four hours in the water had weakened me. Suddenly a pair of strong hands caught me and pulled me up. I do not remember what was happening through the night, but in the morning we saw a difficult scene. The captain of the ship stood and said a prayer, and beside him were several bodies bound with weights. A shot in the air and the bodies were thrown into the sea.”

A Greek sailor rubbed me:

Most of the soldiers and the crew that remained on Erinpura died that night. Of the 300 members of the Company there only 160 survivors who were transferred to safety. “I woke up in the ship’s hold as a Greek sailor rubbed me with a towel and another poured rum for me” says Zeiler.

“After that we went to Tripoli and we got some clothes. We were there for a week or ten days, and then they took us back to Alexandria and later to Israel. We got two weeks off, that the British Army has customarily given for a unit sending two-thirds of its troops home on leave. Ast states: “Freedom of survivors.”

The exit from hell back to the outside world, they suggest, was not easy. “There was a terrible shock. We did not know who was living and who was not, and I was especially worried about those I met, those whose families I knew,” says Melamed, on the first days of return. “When we arrived in Tripoli I wrote letters home. We should not have to clearly write things on what happened, but my letter hinted that something happened to me and I was alive. The censors cut almost everything. You could just understand that I was alive after the date of May 1”.

“My mother did not know whether I was alive or dead,” says Ast. “Several days after the incident there was published in the newspaper Davar a list of 138 soldiers from Eretz Israel who drowned in the sea. Our families had found everything through the paper. When I came to Israel, I got on a bus headed home. I sat not far away from the driver and in front of me sat a man in uniform and he told the driver he was on the ship and he was saved. I heard the story, watching and listening, and knew that here there was one that pretended. When we reached the destination, I approached him and said: ‘I had a very pleasant time hearing your story, but I wanted to ask you if recognize a friend of mine who was on the ship.’ He asked me, ‘Who was your friend?’ I told him: ‘Chaim Ast.’ ‘Ah, Chaim Ast, poor guy, he drowned.’ A minute later I took out my notebook and said to him, at least I have the honor to know of whom you spoke…”

“You have to understand that by then there was no event of this magnitude,” adds Zeiler. “We had far more casualties than the Jewish Brigade. When I came back they told me: ‘What are you doing here? After all that had drowned.’”

After home leave the three were called back to the front. The company had been rebuilt, and in September 1943 was attached to the Allied forces that invaded Italy via Salerno, south of Naples. There they were busy unloading docks and transport equipment, fuel and ammunition to the front, the first confrontation with the horrors of the Holocaust. “So we met with the survivors,” says Ast. “When we went to the British Army, the goal was to save the land of Israel; we had no idea that of all this story. They came to us as refugees and we could not believe them at all. Little by little, like drops of water upon the rock, came more and more.”

The three moved on – built homes, developed careers, and have designed their own memorial event. After Salerno took place the first memorial event booklet about the difficult situation of the sinking, exactly a year after that occurred. Since they are conscientious in participating every year at the memorial to the 140 names, at a unique monument erected in their memory at Mount Herzl.

…”We should not write clearly on things that happened, but my letter hinted that something happened to me and I’m alive. The censors cut almost everything” … Ben Ami Melamed.

* * * * * * * * * *

The document below is an account of the sinking of the Erinpura by (I think…?) Major Yoffe, commander of the 462nd General Transport Company. The document is from Volume 2 of Dr. Yoav Gelber’s Jewish-Palestinian Volunteering in the British Army During the Second World War.

The following 2-page letter, from Volume 2 of Jewish-Palestinian Volunteering in the British Army During the Second World War, also (I believe) describes the sinking of the Erinpura. (Translation would be appreciated!)

The following 2-page letter, from Volume 2 of Jewish-Palestinian Volunteering in the British Army During the Second World War, also (I believe) describes the sinking of the Erinpura. (Translation would be appreciated!)

This is the first page…

…and this is the second page.

…and this is the second page.

* * * * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * * * *

The following letter, written on May 4, 1943 by Corporal Amiram Ben Zvi (or, “Ben Zion”?), PAL/551, a survivor of the sinking, is reproduced in Volume 2 of Jewish Palestinian Volunteering in the British Army During the Second World War, Roi Mandel’s article about the 462nd General Transport Company, and also on page 23 of Yishuv volunteers to the Biritsh Army during the Second World War 1939-45.

The Yishuv Volunteers booklet also includes this Hebrew-character transcript of the letter:

The Yishuv Volunteers booklet also includes this Hebrew-character transcript of the letter:

An approximate English-language translation of this text (generated via Google.translate) follows:

An approximate English-language translation of this text (generated via Google.translate) follows:

“Greetings to you my dear!

I am alive, not writing for a time. I would especially like to tell you that I am safe and sound, after hardships, and that I am in the same place as a month ago with a large number of friends.

How are you all? For several weeks I have not received any information from you and hope I receive everything all at once.

I said goodbye to all families and friends, and do not believe the false rumors. Maybe I’ll see you soon.

Next time I’ll be here longer.

Farewell,

Forever Yours

Amiram”

The Location

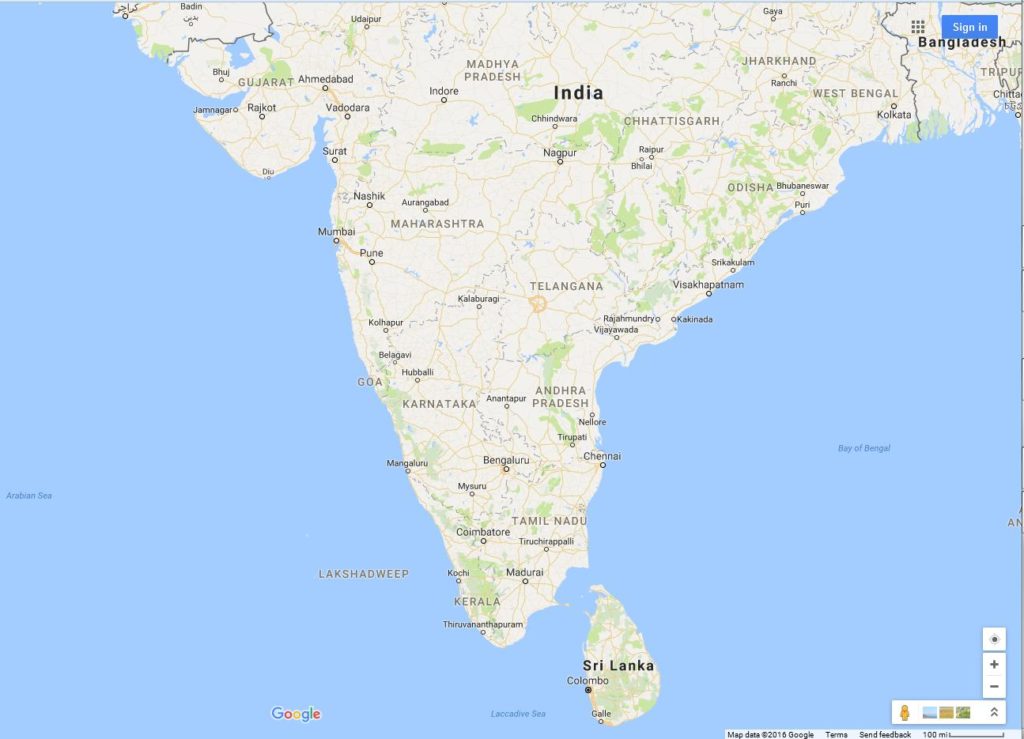

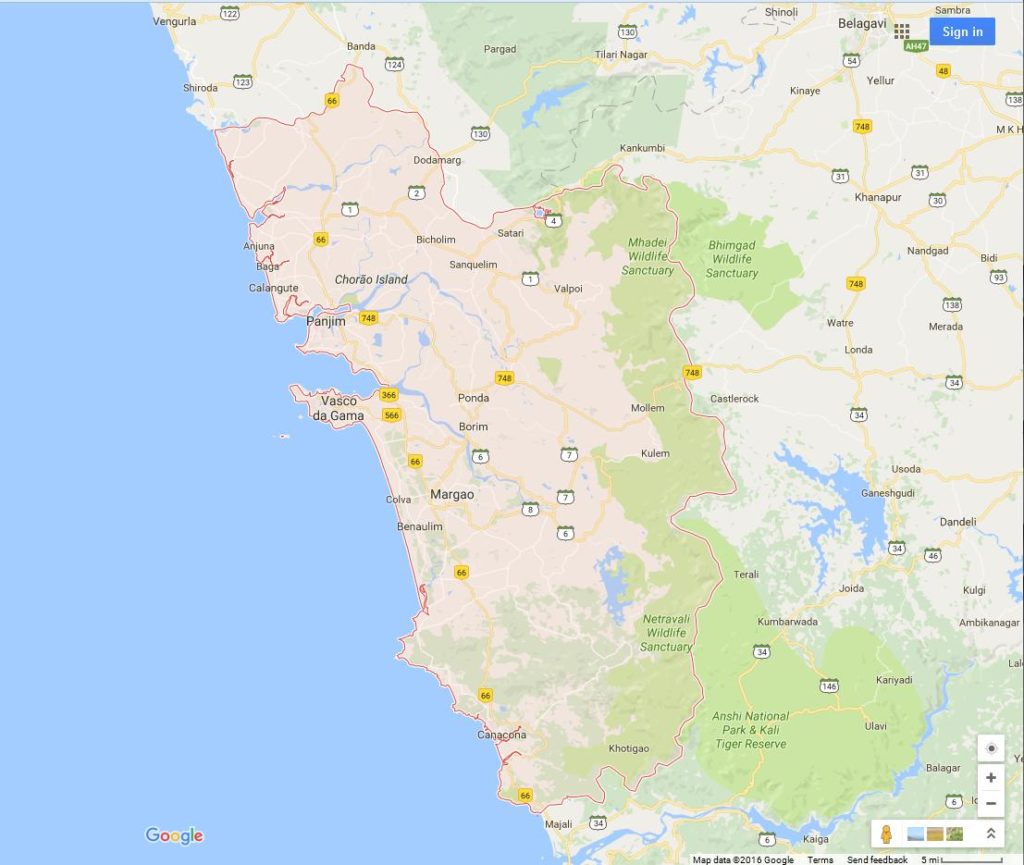

Wikipedia’s list of shipwrecks gives the position of the Erinpura’s sinking as 32-40N, 19-53 E, while the British Trust was lost, “30 nautical miles (56 km) north northwest of Benghazi, Libya”. The website notes that this location is derived from Norman Clothier’s article, but oddly, no such reference can actually be found in that article. Regardless, maps – at successively larger scales, created via Google Maps – showing the location of the Erinpura’s sinking are presented below:

Based on the above-illustrated location, a bathymetric map of the Mediterranean Sea created by Ikonact shows that the ship – forever the final resting place for several hundred men – lies at a depth of approximately 500 meters, approximately 30 miles north-northwest of Benghazi, Libya.

Based on the above-illustrated location, a bathymetric map of the Mediterranean Sea created by Ikonact shows that the ship – forever the final resting place for several hundred men – lies at a depth of approximately 500 meters, approximately 30 miles north-northwest of Benghazi, Libya.