Update…March, 2024:

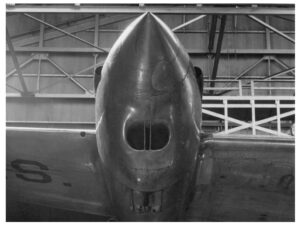

Dating Back to December 30, 2017 – have nearly seven years gone by already? – I’ve made a correction to this post based on a recent communication from Russ Czaplewski. Russ calls attention to the photo of the nose art of B-26B Marauder nicknamed “Becky“, of the 320th Bomb Group’s 441st Bomb Squadron, from Victor C. Tannehill’s book Boomerang! – Story of the 320th Bombardment Group in World War II.

In my caption to the image, I originally identified this camouflaged B-26 as aircraft 42-107711, squadron / battle number “02“, which was piloted by Lt. Paul E. Trunk and lost with its entire crew on August 15, 1944, when the plane crashed into a mountain in bad weather.

Here’s Russ’s message:

“I have an original negative with a similar view of “Becky” and the serial number above the round unit logo reads 42-96119 rather than 41-107711. There were multiple bombers named “Becky” in the 441st and the illustration shown is not sharp enough to distinguish the serial number.”

Along with the corrected information about 42-107711, I’ve updated the post by including the text of the obituary for Heinz Thannhauser’s father Justin, and, adding links to FindAGrave for the eight crew members of the lost B-26.

______________________________

Aufbau: The Reconstruction of Memory

As irony abounds in the histories of nations, so it does in the lives of men.

During World War Two, a striking irony could sometimes be found among Jewish military personnel in the Allied armed forces. Some Jewish soldiers, at one time citizens of Germany and Austria, and subsequently refugees and emigrants from those countries, might – through a combination of intention and chance – find themselves arrayed in battle against the Axis. This circumstance, a melding of civil obligation, moral responsibility, idealism, motivated by a personal sense of justice, was deeply symbolic aspect of Jewish military service during the Second World War.

For the United States, a perusal of both the Jewish press and the general news media from 1942 through 1945 reveals occasional articles – and inevitably, casualty notices – covering such servicemen. Such news items called specific attention to the circumstances behind a soldier’s arrival in the United States, and often extended to accounts of his family’s pre-war life in Germany or Austria. This was not limited to the American news media. The Jewish Chronicle of England was replete with articles covering the military service of Jewish refugee soldiers in the armed forces of England and British Commonwealth countries, including – before Israel’s re-establishment in 1948 – British military units comprised of personnel (often refugees) from the pre-State Yishuv.

In the American news media, a striking example of one such news items appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer on June 13, 1943.

GERMAN REFUGEE MISSING IN ACTION

A 22-year-old German refugee who fled his native Leipzig in 1935 to escape Nazi persecution is one of four Philadelphians reported last night by the War Department as missing in action.

He is Corporal Maurice Derfler, of 1601 Ruscomb St., worker in a Philadelphia clothing factory before he entered the Army Air Forces on March 28, 1942.

WROTE TO FIANCEE

Derfler has been missing since May 19, just five days after his fiancée, Mildred Roush, 19, of 4813 N. Franklin St., received a letter from him, stating that he was “going on a dangerous mission” but felt sure that he would return. For, he explained, he was looking forward to his furlough next September, when he and Miss Roush would be married.

The next message was the War Department communication, which Abraham Roush, prospective father-in-law of the soldier, received on May 29. The message stated that Derfler, a radio operator in a Consolidated Liberator bomber, had failed to return from a mission.

FIANCEE CONFIDENT

Miss Roush, who is confident that Derfler will return, “and I still will be waiting,” could tell little of her fiancee’s flight from his native Germany. “He didn’t like to talk about it. It must have been an ordeal for him. He keeps it as his secret.”

Derfler, Miss Roush recalled, arrived in Philadelphia with a group of other refugees. His one desire was to get into the American forces for a “crack at the Germans.” He was naturalized in September of 1941 and the following March entered the service. Ironically, the Air Forces sent him into the Pacific area.

Corporal Derfler served as a radio operator in the 400th Bomb Squadron of the 90th (“Jolly Rogers”) Bomb Group of the 5th Air Force. His aircraft, a B-24D Liberator (serial number 41-29269) piloted by 1 Lt. Donald L. Almond, was conducting a solo daylight reconnaissance mission along the eastern coast of New Guinea. It was intercepted by five Japanese pilots of the 24th Sentai, who were flying Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa (Japanese for “Peregrine Falcon”; Allied code-name “Oscar”) fighter planes. One of these aviators, Sergeant Hikoto Sato, was killed during the engagement when his fighter rammed the B-24.

As the aerial engagement began, the B-24 radioed a message – likely transmitted by Corporal Derfler himself – that it was under attack by Japanese fighters.

Five minutes later, another radio message reported that the plane was going down.

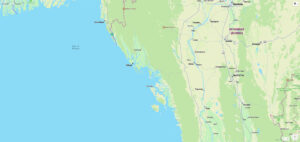

No trace of the plane or crew – presumed to have crashed near Karkar Island, off the northeastern coast of New Guinea – has ever been found.

The names of the B-24’s ten crewmen are commemorated at the Tablets of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery, in the Philippines.

Corporal Derfler (serial number 33157713) received the Air Medal and Purple Heart. In 1943, he was mentioned in The American Hebrew (August 20), the Chicago Jewish Chronicle (August 27), and The Jewish Times (Delaware County, Pennsylvania) (September 3).

Initially assigned to the famed 44th (“Flying Eightballs”) Bomb Group – which, ironically, flew bombing missions against Germany – Cpl. Derfler was the only member of his family to have escaped from Germany.

______________________________

In terms of detailed information about the military service of German-Jewish refugees in the armed forces of the Allies – in general – and United States in particular, one publication stands out: Aufbau, or in translation, “Construction”, or “Building Up”. Published between 1934 and 2004, the newspaper was founded by the German-Jewish Club, later re-named the “New World Club”. Originally intended as a monthly newsletter for the club, the periodical changed markedly when Manfred George was nominated as editor in 1939. George transformed the publication to one of the leading anti-Nazi periodicals of the German Exile Press (Exilpresse) Group, increasing its circulation from 8,000 to 40,000. According to the description of Aufbau at Archiv.org (and as can be solidly verified from perusal of its contents), writings of many well-known personalities appeared in its pages. (Three names among many: Albert Einstein, Thomas Mann, and Stefan Zweig.) According to Wikipedia, after having been published in New York City through 2004, the periodical subsequently began publishing in Zurich. However, the given link (http://www.aufbauonline.com/) seems to be inoperative.

A catalog record for Aufbau – and 29 other periodicals comprising German Exile Press publications can, appropriately, be found at the website of the German National Library – Deutsch National Bibliothek. A screen-shot of the catalag record for Aufbau is shown below:

When the Aufbau was reviewed in 2010, it could be accessed directly through the DNB’s website. However, by now – 2017 – it seems to be only available through archive.org. This is the first page of Archive.org catalog record for the publication:

When the Aufbau was reviewed in 2010, it could be accessed directly through the DNB’s website. However, by now – 2017 – it seems to be only available through archive.org. This is the first page of Archive.org catalog record for the publication:

Unlike the DNB website, which (as I recall?…) allowed access and viewing of the publication on an extraordinarily useful issue-by-issue and even page-by-page basis, users accessing Aufbau at Archive.org cannot view the periodical at such a fine level of informational ”clarity”. (Despite being able to scroll through and view volumation and numbering of all issues in Archive.org’s “View EAD” window.) Rather, once a hyperlink for any issue is selected, the entire content for that year is then displayed in a new window as a single file – and that year’s full content is also downloaded as a single PDF, or in other formats.

Unlike the DNB website, which (as I recall?…) allowed access and viewing of the publication on an extraordinarily useful issue-by-issue and even page-by-page basis, users accessing Aufbau at Archive.org cannot view the periodical at such a fine level of informational ”clarity”. (Despite being able to scroll through and view volumation and numbering of all issues in Archive.org’s “View EAD” window.) Rather, once a hyperlink for any issue is selected, the entire content for that year is then displayed in a new window as a single file – and that year’s full content is also downloaded as a single PDF, or in other formats.

The image below shows issue records for Aufbau as they appear at the Archive.org catalog record. (The format of this information is representative of, and identical to, issue records for all other years of publication.)

And… This image shows the interface for 1942 issues of Aufbau, by which the publication – encompassing that entire year – can be viewed online, or downloaded. Other years of publication are displayed in a similar manner.

And… This image shows the interface for 1942 issues of Aufbau, by which the publication – encompassing that entire year – can be viewed online, or downloaded. Other years of publication are displayed in a similar manner.

PDF file sizes for wartime editions of Aufbau are:

PDF file sizes for wartime editions of Aufbau are:

1941 (Volume 7): 453 MB

1942 (Volume 8): 566 MB

1943 (Volume 9): 513 MB

1944 (Volume 10): 530 MB

1945 (Volume 11): 353 MB

Published on a weekly basis, Aufbau provides overlapping windows upon American Jewry, German Jewry (particularly of course, those Jews fortunate enough to have escaped from Germany), and world Jewry, through its coverage of political, social, and intellectual developments of the late 1930s and early 1940s. News covered by the publication pertained to all facets of life, “in general”: current events; literary, cultural, cinematic, theatrical, and social news; and, innumerable essays and opinion pieces.

Intriguingly, the paper’s news coverage and editorial content – at least encompassing 1939 through 1946 – suggests intertwining, competing, and parallel aspects of thought that have persisted since the halting beginnings of Jewish “emancipation” only a few centuries ago: One one hand, a staunch and unapologetic emphasis on Jewish identity and Zionism. On the other, the subsuming of Jewish identity within a wider world of (ostensibly) democratic universalism.

(Ah, but I digress. That is another long, and continuing story…)

Back, to the topic at hand…

Though Aufbau’s central focus was not Jewish military service as such, the newspaper nonetheless serves as a tremendously rich repository of information – genealogical; biographical; historical – about the experiences of Jewish soldiers during the Second World War. In that sense, news items in Aufbau relevant to Jewish military service falls into these general themes:

1) Lists of awards and honors;

2) News about and accounts of military service by American Jewish soldiers; similarly-themed news items about military service of Jews in other Allied nations (the Soviet Union, British Commonwealth countries, France, and Poland);

3) Detailed biographies of soldiers wounded, killed, and missing in action;

4) The campaign for the establishment of some form of autonomous Jewish fighting force;

5) The activities of the Jewish Brigade Group;

6) The military service of Jews from the Yishuv in the armed forces of Britain and other Commonwealth nations;

7) Zionism – the drive to re-establish a Jewish nation-state.

These items are often accompanied by photographs of the specific servicemen in question, or, thematically relevant illustrations. Of course, given the origin and ethos of Aufbau, from editor to publisher; from correspondents to stringers to contributors; in its coverage of Jewish military service, the newspaper placed great – if not central – emphasis, on Jewish soldiers whose families originated in Germany, and who were fortunate enough to have found citizenship in the United States.

The following five categories of articles in Aufbau are immediately relevant to the seven “themes” listed above:

1) The Struggle for a Jewish Army – 139 articles

2) Jews of the Yishuv at War – 33 articles

3) Jewish Prisoners of War – 10 articles

4) Jewish Military Casualties – 132 articles

5) The Jewish Brigade – 37 articles

6) Photographs (primarily of soldiers, yet including other subjects) – 252

…while the following three categories of items, though not directly related to Jewish WW II military service, are very relevant to the “tenor of the times”…

1) antisemitism / Judeophobia – 20 articles

2) Random News Items About the Second World War – 31 articles

3) Acculturation and Assimilation – 48 articles

______________________________

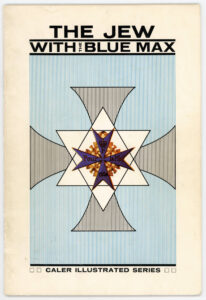

As examples of such news items in Aufbau – yet more than mere examples; to bestow symbolic tribute upon the many German-Jewish soldiers who served in the Allied armed forces – news items about two WW II German-Jewish soldiers (Army Air Force S/Sgt. Heinz H. Thannhauser and Army PFC George E. Rosing) follow.

Aufbau’s biography of S/Sgt. Thannhauser is quite detailed, probably due to his family’s prominence in the German-Jewish immigrant community, and, the world of art Even before he entered the Army Air Force, Heinz’s background and accomplishments portended a remarkable future, if only his bomber had taken a slightly different course before before a Sardinian sunrise on August 15, 1944…

Heinz was the son of Justin K. (5/7/82-12/26/76) and Kate (Levi) (5/24/94-1959) Thannhauser, grandson of Heinrich Thannhauser, and the lineal descendant of Baruch Loeb Thannhauser, his father and grandfather originally having been residents of Munich, where – as art dealers – they owned the Thannhauser Galleries, specializing in Modernist art. Justin moved to Paris in 1937 with his family to escape the Third Reich, and after the outbreak of the Second World War, to Switzerland. They fled to the United States in 1941, establishing themselves in New York City, where Justin opened a private gallery, the initial core of which comprised a number of works that he had managed to bring with him to America.

Due to Heinz’s death, and the doubly tragic passing of his only other child Michel in 1952, Justin cancelled plans to open a public gallery. He remained a resident of New York until 1971, operating his gallery, collecting art, and assisting museums and galleries with exhibitions and acquisitions. In recognition and honor of his sons and their late mother Kate – as well as his support of artistic progress – Justin’s collection was bequeathed to the Guggenheim Museum in 1963. Due to the scope, size, and centrality of the collection, the Guggenheim established the Thannhauser Wing in 1965, where the original components of the collection, as well as additional works, are now on display.

Justin passed away in 1976, his only survivor having been his second wife, Hilde. Here is is obituary, as published in The New York Times on December 31, 1976.

Justin Thannhauser Dead at 84; Dealer in Art’s Modern Masters

December 31, 1976

GSTAAD, Switzerland, Dec. 30 (AP) —Justin Thannhauser, a German‐born United States art dealer whose landmark exhibitions spread the fame of modern masters such as Pablo Picasso, Edvard Munch and Paul Klee, died here last Sunday, a personal friend said today. He was 84 years old.

A Swiss journalist, Gaudenz Baumann, said Mr. Thannhauser suffered a heart attack in his hotel room last Friday. He was buried in Bern today.

Mr. Thannhauser’s five galleries in Gerbieny, Switzerland, France and the United States handled some of the best work of the 20th‐century masters.

He turned the Munich art gallery that his father founded in 1904 into a focal point for Mr. Munch and other Die Bruecke group expressionists, Klee, Vassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc.

Collection Seized

Mr. Thannhauser branched out to Lucerne from 1919 to 1939 and opened Galerie Thannhauser, his biggest gallery, in Berlin, in 1927.

During a 1937 Swiss visit, the Jewish dealer’s Berlin collection was seized by the Nazi regime. He was forced to reestablish himself in Paris, only to lose another collection to the Nazis during the World War II German invasion of France.

Mr. Thannhauser fled to New York in 1941 and started collecting from scratch. Among many works he donated to art museums, 75 paintings including valuable French Impressionist works are on display in the Thannhauser wing of the Guggenheim Museum in New York City.

It was in the “Moderne Gallerie” that Mr. Thannhauser ran in Munich from 1909 to 1928 that Marc and Kandinsky first met and in 1911, founded the group of artists named Der Blaue Reiter – the blue rider – after a famous Kandinsky painting.

The first major exhibitions by Picasso and Marc were held there in 1909. Mr. Thannhauser retained his links with Picasso and was one of the few visitors with regular access to the Spanish painter before he died in 1973 in his cloistered home in France.

The Moderne Gallerie staged the first Klee display in 1911 and the same year, helped fix Blaue Reither group’s place in modern art history with a pioneering exhibition.

Mr. Thannhauser left the United States in 1971 to retire in Switzerland, dividing his time between his Bern home and Gstaad.

His only surviving close relative is his second wife, Hilde, 56. A son from former marriage was killed in the crash of a United States bomber in the south of France during the 1944 Allied invasion.

______________________________

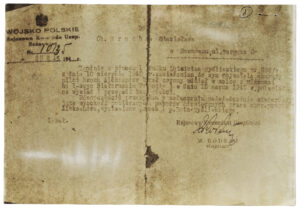

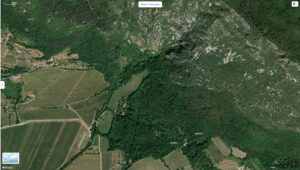

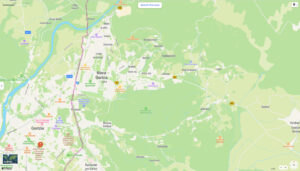

A radio operator in the 441st Bomb Squadron of the 320th Bomb Group (12th Air Force), Heinz and his seven fellow crewmen were killed when their B-26C Marauder (serial 42-107711, squadron number “02”, nicknamed “Becky” [Update, March, 2024 … see correction about aircraft identification in next paragraph…] crashed during take-off from Decimomannu, Sardinia, on August 15, 1944. The plane flew directly into the side of Monte Azza, 2 kilometers from the town of Serrenti, in the pre-dawn darkness. The aircraft had been one of 34 B-26s dispatched to bomb a beach at Baie de Cavalaire (north of Saint Tropaz), France. As revealed in the 320th Bomb Group’s report of that mission, one other B-26s was lost on take-off, fortunately with all crewmen surviving.

Heinz’s name would appear in an official casualty list published in October 21, 1944,

______________________________

The illustration below, from Victor Tannehill’s Boomerang! – Story of the 320th Bombardment Group, shows what I believe is “the” actual Becky: 42-107711. The circular emblem just behind the bombardier’s position is the insignia of the 441st Bomb Squadron, while rows of bomb symbols painted to the right of the plane’s nickname denote sorties against the enemy. [Update… Based on information from Russ Czaplewski, this aircraft isn’t 42-107711, a B-26C-45-MO. It’s actually 42-96119, a B-26B-55-MA. Being that there is neither a Missing Air Crew Report nor an Accident Report for this aircraft, I would assume that the latter plane survived the war and was returned to the United States for reclamation by the RFC.]

______________________________

______________________________

This image, from Vintage Leather Jackets, shows a beautiful original example of a 441st Bomb Squadron uniform patch, which would have adorned the flying jacket of many a 441st BS airman. The Latin expression “Finis Origine Pendet”, superimposed on a B-26 Marauder, means “The Beginning of the End”.

______________________________

______________________________

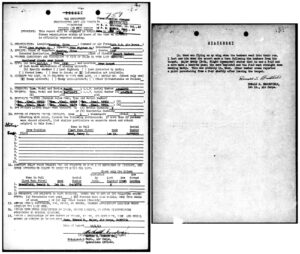

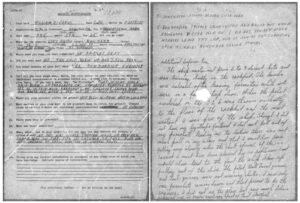

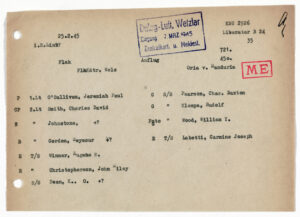

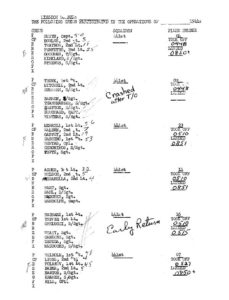

Here is the 320th Bomb Group’s Mission Report covering the mission of August 15, 1944. Becky’s [42-107711’s] crew is listed at the bottom.

______________________________

______________________________

Most of the Mission Report is comprised of crew lists for the B-26s assigned to the mission, the page below covering six aircraft of the 441st Bomb Squadron. Lieutenant Trunk’s plane and crew are listed second, with the notation “Crashed after T/O written alongside.

______________________________

______________________________

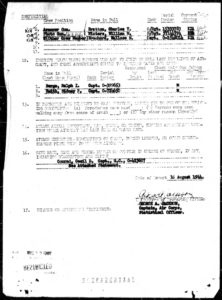

As stated in the concluding paragraph of the Missing Air Crew Report covering Becky (MACR 7300), “He [1 Lt. Paul E Trunk, the plane’s pilot] made no attempt to contact us by radio so further attempts to ascertain the exact cause would only be conjecture. In our opinion the actual cause of the accident cannot be ascertained.”

Here is the first page of the Missing Air Crew Report for the loss of Becky [42-107711], with five of the plane’s crew listed at bottom…

______________________________

______________________________

…while this is the second page, listing Sergeants Bratton and Winters, with Captain Brouchard, as a passenger, at the end.

______________________________

______________________________

This page lists the home addresses and next of kin of the crew.

______________________________

Lt. Trunk, from Shippenville, Pennsylvania, is buried in Arlington National Cemetery (Section 12, Grave 4836). Lt. Rolland L. Mitchell, the plane’s co-pilot, from Thomson, Illinois, is buried at Lower York Cemetery, in that city. T/Sgt. William C. Barron, the flight engineer, from Los Angeles, is buried at the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery and Memorial, at Nettuno, Italy.

The remaining five crewmen – Heinz (army serial number 31296512), S/Sgt. Harmon R. Summers (bombardier), S/Sgts. Charles T. Bratton (aerial gunner) and William M. Winters (photographer), with Capt. Wallace M. Brouchard (the Executive Officer of the 441st, who “went along for the ride”) – were buried on March 18, 1949 at – as you can see from the proceeding links – Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in St. Louis, in collective grave 90-92.

This picture, of the collective grave marker of the above-listed crewmen, is by FindAGrave contributor Erik Kreft.

______________________________

______________________________

Exactly one month after Heinz was killed, a tribute to him appeared in Aufbau.

HEINZ THANNHAUSER

Aufbau

September 15, 1944

Ein wunderbar erfülltes junges Leben hat ein jähes Ende genommen. “Heinz Thannhauser, Staff Sgt. of the U. S. Army Air Force, killed in action over Sardinia, August 15, 1944.”

Fünfundzwanzig Jahre alt. Ein Liebling der Götter und der Menschen. Glücklichste Jugend im schönsten, wärmsten Elternhaus. Begeistert Amerika liebend und überall hier Gegenliebe findend. Ungewöhnlich begabt, ungewöhnlich reif. Mit sechzehn Jahren — statt der erforderten achtzehn — war er in Cambridge zum Studium zugelassen worden — eine beispiellose Ausnahme in der traditionsgebundenen englischen Universität. In Harvard macht er seinen Doctor of Art. Mit 22 Jahren wird er Instructing Professor an der Universität Tulane, New Orleans.

Lehren ist seine Leidenschaft. Er versteht es, wie wenig andere, die Begeisterung seiner Schuler zu wecken. Nicht nur für die Kunst, zu der er von Kindheit auf die Liebe im Elternhause eingesogen hatte. Er wirbt und wirkt für das, was nur als das Höchste ansicht: für das Ideal demokratischer Freiheit. Er gründet Jugendklubs, hält Reden, schreibt Aufsehen erregende Aufsatze — er reisst die anderen durch seine starke Empfindung mit. Und durch den wunderbaren Sense of humor, den er mit seiner scharfen Beobachtungsgabe verbindet.

Aber in diesem lebensschäumenden, von Schönheit und Frohsinn erfüllten Menschen steckt ein glühender Hass gegen die brutalen Gewalten, die den Untergang Europas herbeigeführt haben. Und eine ganze Welt schwer bedrohen. Als der Krieg hier ausbricht, meldet er sich sofort freiwillig.

Im Februar 1943 verlässt Heinz Thannhauser Amerika auf seinem Bombenflugzeug. Von nun an kommen Briefe, Briefe, Briefe. Es sind nicht nur Schätze für seine Eltern. Es sind Dokumente der Zeit und Dokumente schönster Menschlichkeit. Er kennt keine Trägheit des Herzens. Er ist ein Kämpfer aus Leidenschaft — vom ersten bis zum letzten Tag. Heinz Thannhauser glaubt glühend an die gerechte Sache, die er vertritt. Wie eine Beschwörung kehrt der Satz wieder:

“Ihr musst alles tun, was in Eurer [not legible] steht um zu verhindern, dass es jemals wieder einen solchen Krieg gibt.. nicht mit Phrasen – – mit Taten…”

Er selbst leistet einen Schwur, sein Leben lang dafür zu kämpfen.

Ein Bericht aus Rom, wo er drei selige Urlaubstage verbringt, klingt wie eine Fanfare. Er ist in einem Glückstaumel. Seitenlang schildert er Details einiger Gestalten am Plafond der sixtinischen Kapelle — zum erstenmal sieht er im Original die Meisterwerke, über die er gelehrt und geschrieben hat. Er ist wie betrunken von so viel Schönheit. Aber gleich danach:

“Trotz allem, es ist wichtiger, das Leben eines einzigen unschuudigen Geisel zu retten, als das schonste alte Kunstwerk…”

In einem seiner letzten Briefe schildert er die Erregung, die mit jedem Flug verbunden ist. (Er hatte 37 Missions hinter sich…):

“…The sober anticipation before a mission. The terrible feeling of going time after time through heavy flak without being able to do anything except sit and hope for the best. The real exultation of seeing your bombs hit the target – huge flames coming up and smoke as high as you are flying. The relief and joy at seeing your field again, like home indeed! Also – losing your friends – empty beds, guys who, the night before, were talking of what names to give their children and so on… And I share his horror of war and determination that it must never happen again…”

Heinz Thannhauser hat ein Testament hinterlassen. Er vermacht alles, was er besitzt, dem “American Youth Movement for a Free World”.

– A. D.

______________________________

Fallen For Freedom

HEINZ THANNHAUSER

Aufbau

September 15, 1944

A wonderfully fulfilling young life took an abrupt end. “Heinz Thannhauser, Staff Sgt. of the U.S. Army Air Force, killed in action over Sardinia, August 15, 1944.”

Twenty-five years old. A favorite of God and mankind. The happiest youth in the most beautiful, warmest home. Enthusiastic, America loving and everywhere here finding requited love. Unusually gifted; unusually mature. At sixteen years – instead of the required eighteen – he had been admitted to Cambridge to study – an unprecedented exception to the tradition-bound English university. At Harvard he makes his Doctor of Art. At 22 he is an instructing professor at Tulane University, New Orleans.

Teaching is his passion. He understands how little others awaken the passion of his students. Not only for art, which from childhood he had imbibed to love in his parents’ home. He promotes and acts only for what is the highest opinion: For the ideal of democratic freedom. He founds youth clubs, gives speeches, writes sensational essays – he pulls others with his strong feelings. And through a wonderful sense of humor, which he combines with his keen powers of observation.

But in this tumultuous beauty and joy, there is an ardent hatred against the brutal forces which have led to the downfall of Europe. And heavily threaten the whole world. When the war broke out, he immediately volunteered.

In February 1943, Heinz Thannhauser left America on his bomber aircraft. From now on arrive letters, letters, letters. They’re not just treasures for his parents. They are documents of time and documents of the most beautiful humanity. He knows no indolence of the heart. He is a fighter of passion – from the first to the last day. Heinz Thannhauser glowingly believes in the just cause he represents. Like an incantation, the sentence repeats:

“You have to do everything that is in your [power] to prevent that there is ever such a war again … not with phrases – – with deeds …”

He himself makes an oath, to fight for this all his life.

A report from Rome, where he spends three blissful holidays, sounds like a fanfare. He is in a stroke of luck. For pages on end he describes details of some figures on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel – the first time he sees the original masterpieces, about which he has taught and written. He is intoxicated with so much beauty. But immediately afterwards:

“In spite of all this, it is more important to save the life of a single innocent hostage than the most beautiful old work of art …”

In one of his last letters, he described the excitement that is associated with each flight. (He had 37 missions behind himself…):

“… The sober anticipation before a mission. The terrible feeling of going through heavy flak time after time without being able to do anything except sit and hope for the best. The real exultation of seeing your bombs hit the target – huge flames coming up and smoke as high as you are flying. The relief and joy at seeing your field again, like home indeed! So – losing your friends – empty beds, guys who, the night before, were talking of what names to give their children and so on… And I share his horror of war and determination did it must never happen again… “

Heinz Thannhauser made a will. He bequeathed everything he owned, to the “American Youth Movement for a Free World”.

– A.D.

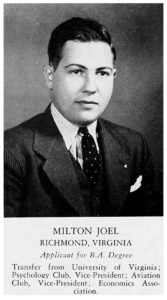

While the Aufbau article touched upon the depth of Heinz’s education and ambitions, his life was chronicled in much greater detail in College Art Journal in 1945 (Volume 4, Issue 2) in the form of a biography by “H.R.H.”:

On August 15, 1944, Sgt. Heinz H. Thannhauser was killed in action while in service of his country as radio operator and gunner on a Marauder Bomber in the Mediterranean theatre. His parents have recently been notified that Heinz was awarded posthumously the Purple Heart.

He was born in Bavaria on September 28, 1918. The son of the well known Berlin and Paris art dealer, Justin K. Thannhauser, Heinz had a unique opportunity of becoming acquainted with the works of modern artists at an early age. He received his primary and secondary education at the College Francais in Berlin and later in Paris at the Sorbonne. He then attended Cambridge University. England, and took his B.A, degree in 1938. In that year he came to this country at the age of twenty, and was holder of the Sachs fellowship at Harvard University. During his two years at Harvard, he specialized in the history of modern art and obtained the A.M. degree in 1941. At the Fogg his brilliant and active mind and his warm enthusiasms won Heinz the respect and the friendship of his fellow students and teachers. In the fall of 1941, he accepted an instructorship under Professor Robin Feild at Newcomb College of Tulane University. He was a collaborator of the ART JOURNAL where he published in March 1943 an article describing a project for collaboration between art and drama departments. He had planned during the summer of 1943 to begin work on his doctoral dissertation, but in February he entered the Army.

Heinz had shown much promise as a young teacher and scholar in the field of art history and his loss will be keenly felt.

H.R.H.

In January 1945, the College Art Journal published another tribute to Heinz, in the form of a transcript of a letter sent to his parents in 1944. Under the title “Furlough in Rome”, the article is an extraordinarily vivid, detailed, yet light-hearted account of a tour of artistic works among churches in that city, this letter having been alluded to in the above Aufbau article.

FURLOUGH IN ROME

BY HEINZ H. THANNHAUSER

Excerpts from a letter written to his parents during the summer of 1944 after a visit to Rome

THAT morning we went to S. Luigi dei Francesi, to look at the Caravaggio pictures; but there was a big mass and celebration there by French troops of the 5th Army, so we didn’t see them. The French came out later in a parade reminiscent of some I’ve seen in Paris, with turbaned troops and all (only their uniforms, except for headgear, are always American) – we took a picture or two of them. Next, we went to the Sapienza and got into the courtyard and looked at St. Ivo; unfortunately, the inside was closed, you can see it only on days when mass is held for the laureates. But we looked at the facade for quite a while, and after this visit to Rome I have even more respect for Borromini than I had by studying him formerly. From there we went to S. Agnese in Piazza Navona, and had a good look at the Four Rivers Fountain too, which really is a pretty daring tour de force on old Bernini’s part. The veil of the Nile is quite something. All in all this visit to Rome has increased my respect for the technical courage and perfection of the Baroque masters if for nothing else in their work. Next, S. Andrea della Valle, which quite apart from its design was amazing as being the first example of Baroque cupola and ceiling decoration I’d seen – the Lanfranco dome not being, perhaps, as terrific as some of them, but quite an introduction! Then the Palazzo Farnese, which is now a French headquarters building. After asking some Sudanese guards for directions, we groped our way up and finally a maid showed us into the Galleria, which was just being cleaned up – what a thrill! A lot of super-moderns despise the Carracci as coldly academic and what-not, but when you see an ensemble like this, which so perfectly fulfills its purpose, your hat goes off to them. The freshness of the color is amazing, and both the figures and the entire composition are pure delight. Especially as a little breather after too many visits to the dark and serious churches – although I understand the fracas caused by cardinals having sexy things like that painted in their home! The other rooms were astounding too, with the woodwork ceilings, etc. I need hardly say how impressed I was with the facade in Rome, however, you get so, that the only thing you notice is a façade that is not perfect, the perfect ones being so common! Next, S. Mariain Vallicella, with another terrific ceiling, and the Rubens altar piece with the angels holding up the picture of the Virgin that the gambler is said to have stoned when it was at S. Mariadella Pace, whereupon real blood came from it.

The next day we went to Santa Susanna and then to S. Maria della Vittoria, but unfortunately the Bernini Ecstacy of St. Theresa has been walled in for protection, like so many other things. The figures of the onlooking Cornaro family in the two side boxes are still visible, though. Then we went up to see S. Carloalle Quattro Fontane, which is just about the most amazing of Borromini’s tours de force. We couldn’t get into the cloister but we looked for quite a long time at the amazing amount of movement and undulation he got into so small a facade at such a narrow corner. We tried to take pictures of it but will have to splice two together, there wasn’t enough backing room.

From there it was just a little way to Sta. Maria Maggiore, which I had especially wanted to see, after that unending paper I wrote for Koehler on the mosaics there. I was afraid they’d probably have them walled up like most of the apsidial mosaics in Rome, but lo and behold, they were all there in their full freshness! It was one of the most terrific artistic impressions I got on our stay in Rome. I had not expected anything like the strength of color that remains just gleaming out at you, – especially so, of course, in the case of the Torriti work but amazingly bright too with the old mosaics. We walked round the whole church looking at the mall: the walls of Jericho falling down, God’s hand throwing stones down on the enemy, Lot’s wife turning to salt, the passage over the Red Sea, etc. I really was happy we had been able to get into Sta. Maria Maggiore.

We had planned to go back via the Thermae of Trajan, but it got too late for that, and at S. Pietro in Vincoli, we heard that Michelangelo’s Moses was all covered up, so we didn’t bother. Instead, we dropped into San Clemente, where so many great painters have worshipped in Masaccio’s chapel. Father McSweeney (it’s a church given to the Irish in Rome), who took us around, remarked, “He was quite a big noise in those days, as you would say!” First I asked him in Italian how to get to the subterranean church, and he answered in Italian and then said “Ye don’t speak much English, do ye?” which was very funny. He proved to be an unusually interesting person, with the most intimate knowledge of art history and styles and so forth as well as all matters pertaining to his church and a lively interest in the war, discussing bombing formations and everything else. He is completely in love with Rome and said there was no place like it to live in, and that he hoped after the war we would all three come to stay and live there! The mosaics, as usual, were covered over, but we had plenty of time to study all the details of the Masaccio and Masolino works, and then went down to the old church below, with the Mithraic statue and the other amazing things. He showed us where the house of Clemens was, and pointed out the usual anecdotic details of the Cicerone with an ever so slight but delightful note of amusement in his voice, placing them where they belong: for instance, with the Aqua Mysteriosa, “because nobody knows where it comes from” he said, as if he meant to say, “and why should anybody give a damn, either?” All in all, on account of the Masolino chapel, the church itself, the subterranean part with its amazing fragments of early painting, and last but not least Father McSweeney’s delightful and enlightened manner, this was one of our most memorable visits in Rome.

We hailed a horse carriage and went straight to St. Peter’s. As Paul and I had already studied it pretty thoroughly the time before, we just glanced into give our friend a look at it, and then went straight to the Sistine Chapel. Well, there just aren’t any words to tell how overwhelming it was. Here I’d written a paper, God knows how long, about the Prophets and Sibyls and the interrelation of figures on the ceiling, but I hadn’t known a damned thing about the ceiling. It is so unbelievably powerful that you can’t say anything. I kept looking, irresistibly, at the Jonah, which epitomizes tome the whole of Michelangelo’s life and torture, and really is, in the last analysis, the culmination and cornerstone to the whole ceiling. What a piece of painting – what a piece of poetry, or philosophy, or emotional outburst, a whole age expressed in one movement of a body! The way in which everything including the Prophets and Sibyls and Atlantes builds up from the relatively quiet figures in the chronologically later pieces (Biblically speaking) to the storm that sweeps through the early Genesis scenes and the figures around them, is inexpressible in words, Romain Rolland’s or anyone’s. As for sheer perfection of painting, the Creation of Adam just can’t be beat. And say what you will, no photographs, detail enlargements of the most skillful kind, can ever do what the things themselves do to you, especially in the context from which you can’t separate them. The Last Judgment is almost an anticlimax against it; and as for the Ghirlandaios, etc., you just can’t get yourself to look at them because something immediately pulls your eye up high again. And when has there ever been a man to do so much to your sense of form with such modest and restrained use of color? You begin to wonder why Rubens ever needed all that richness when a guy like this can sweep you off your feet with just a few tints of rose and light blue and yellow – but where the tints are put, oh boy! Well, it’s all written up in all the books, but I just have to put down what it did to me. – Mediterranean Theatre

Finally, an excellent representative image of B-26 Marauders of the 441st Bomb Squadron in formation, somewhere in the Meditarreanean Theater of War. Notice that the aircraft in this photo comprise both camouflaged (olive drab / neutral gray) and “silver” (that is, uncamouflaged) aircraft. The image is from the National Museum of the Air Force.

______________________________

______________________________

______________________________

Stephen Ambrose’s 1998 book The Victors included recollections of the experiences of Cpl. James Pemberton, a squad leader in the United States Army’s 103rd Infantry Division, covering combat with German forces in late 1944. Pemberton mentioned the death in battle of a German-speaking Jewish infantryman, who was killed while attempting – in his native language – to persuade a group of German soldiers to surrender.

The fact that the soldier remained anonymous lent the story a haunting note, for that man’s name deserved to be remembered.

Aufbau revealed his identity. He was Private First Class George E. Rosing.

Born in Krefeld, Germany, he arrived in the United States on a Kindertransport in 1937. As revealed in the newspaper in September of 1945 (and verified through official documents) he received the Silver Star by audaciously using his fluency in German to enable the advance of his battalion in late November of 1944.

The Victors – Eisenhower and His Boys: The Men of World War II

Stephen E. Ambrose

1998

That same day Cpl. James Pemberton, a 1942 high school graduate who went into ASTP and then to the 103rd Division as a replacement, was also following a tank. “My guys started wandering and drifting a bit, and I yelled at them to get in the tank tracks to avoid the mines. They did and we followed. The tank was rolling over Schu [anti-personnel] mines like crazy. I could see them popping left and right like popcorn.” Pemberton had an eighteen-year-old replacement in the squad; he told him to hop up and ride on the tank, thinking he would be out of the way up there. An 88 fired. The replacement fell off. The tank went into reverse and backed over him, crushing him from the waist down. “There was one scream, and some mortars hit the Kraut 88 and our tank went forward again. To me, it was one of the worst things I went through. This poor bastard had graduated from high school in June, was drafted, took basic training, shipped overseas, had thirty seconds of combat, and was killed.”

Pemberton’s unit kept advancing. “The Krauts always shot up all their ammo and then surrendered,” he remembered. Hoping to avoid such nonsense, in one village the CO sent a Jewish private who spoke German forward with a white flag, calling out to the German boys to surrender. “They shot him up so bad that after it was over the medics had to slide a blanket under his body to take him away.” Then the Germans started waving their own white flag. Single file, eight of them emerged from a building, hands up. “They were very cocky. They were about 20 feet from me when I saw the leader suddenly realize he still had a pistol in his shoulder holster. He reached into his jacket with two fingers to pull it out and throw it away.

“One of our guys yelled, ‘Watch it! He’s got a gun!’ and came running up shooting and there were eight Krauts on the ground shot up but not dead. They wanted water but no one gave them any. I never felt bad about it although I’m sure civilians would be horrified. But these guys asked for it. If we had not been so tired and frustrated and keyed up and mad about our boys they shot up, it never would have happened. But a lot of things happen in war and both sides know the penalties.”

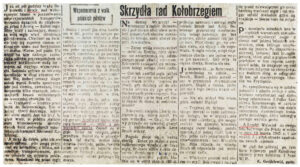

Aufbau’s tribute to PFC Rosing appeared nineteen days after the end of the Second World War.

Pfc. George E. Rosing

Aufbau

September 21, 1945

Der fruhere Gert Rozenzweig aus Krefeld, zuletzt Cincinnati, O., ist am 1. Dezember 1944 beim Vormarsch auf Schlettstadt im Elsaas im Alter von 21 Jahren gefallen. Er wurde jetzt posthum mit dem Silver Star, der dritthöchsten Auszeichnung der amerikanishen Armee, geehrt. – Es war am 24. November 1944, als die Spitze seines Bataillons in der Nähe von Lubine in Frankreich auf eine unerwartete feindliche Block-Stellung stiess, die die Strasse versperrte. Unter Lebensgefahr trat Pfc. Rosing vor und begann, den feindlichen Wachposten auf deutch ins Gespräch zu ziehen. Auf dessen Befehl legte er die Waffen nieder ung ging bis zu zehn Meter an den Wachposten heran. Damit gab er seinen Kameraden Gelegenheit, Deckung zu suchen und den Angriff vorzubereiten. Der Wachposten war uberrascht. Bevor er sich aber der Situation bewusst wurde und Alarm geben konnte, gelang es der amerikanischen Truppe, durch die Stellung durchzustossen. – Pfc. Rosing kam 1937 mit einen Kindertransport nach Amerika; 1942 nachdem er gerade ein Jahr am College of Engineering an der Universität Cincinnati studiert hatte, trat er in die Armee ein.

The former Gert Rozenzweig from Krefeld, most recently of Cincinnati, Ohio, fell on 1 December 1944 on the way to Schlettstadt in Elsaas at the age of 21 years. He has now been posthumously honored with the Silver Star, the third highest honor of the American Army. It was on November 24, 1944, when the head of his battalion encountered an unexpected enemy position blocking the road near Lubine in France. Under mortal danger, Pfc. Rosing began to draw the enemy sentinel into conversation. At his [the German sentinel’s] orders he laid down his weapons and went up to ten meters to the sentry. He gave his comrades the opportunity to seek cover and prepare for the attack. The sentry was surprised. But before he [the German sentinel] became aware of the situation and could give the alarm, the American force managed to break through the position. – Pfc. Rosing came to America in 1937 with a children’s transport; in 1942, after just one year studying at the College of Engineering at Cincinnati University, he joined the army.

Aufbau, September 21, 1945, page 7: The story of George Rosing.

The account of PFC Rosing’s award of the Silver Star appears to have been derived from his “original” Silver Star citation, which can be found at the website of the 103rd Infantry Division Association. The full citation reads as follows:

The account of PFC Rosing’s award of the Silver Star appears to have been derived from his “original” Silver Star citation, which can be found at the website of the 103rd Infantry Division Association. The full citation reads as follows:

HEADQUARTERS 103d INFANTRY DIVISION

Office of the Commanding General

APO 470, U.S. Army

19 December 1944

GENERAL ORDERS)

:

NUMBER – 75)

AWARD, POSTHUMOUS, OF SILVER STAR

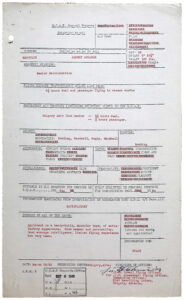

Private First Class George E. Rosing, 35801894, Infantry, Company “C”, 409th Infantry Regiment. For gallantry in action. During the night of 24 November 1944, in the vicinity of *** France, Private Rosing was with the battalion point, acting as interpreter, when an enemy road block was encountered. The point was cutting the surrounding barb wire entanglement around the road block when suddenly challenged. Private Rosing, a brilliant conversationalist in the enemies [sic] language, immediately stepped forward, with utter disregard for his life, to engage the sentry in conversation. He was ordered to drop his arms and advance to within 15 feet of the sentry, which he did. This gallant move gave the point an opportunity to seek cover in the immediate area. The guard stupefied by Private Rosing’s boldness was unaware of the situation confronting him. Before the guard could regain his composure, Private Rosing, assured that his group had reached safety, dived for the bushes as the sentry opened fire, and returned to his comrades unscathed. As a result of his quick thinking and calmness during a tense situation the battalion was able to pass through the enemy road block successfully in the push towards its objective. Throughout this entire activity his display of magnificent courage reflects the highest traditions of the military service. Residence: Cincinnati, Ohio. Next of kin: Eugene Rosenzweig, (Father), 564 Glenwood Avenue, Cincinnati, Ohio.

By command of Major General HAFFNER:

G.S. MELOY, JR.

Colonel, G.S.C.

Chief of Staff

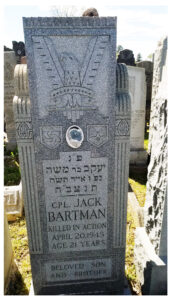

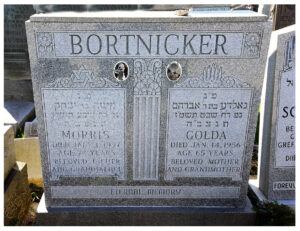

Born on December 3, 1923, PFC Rosing (serial number 35801894) was the son of Eugene and Herta (Herz) Rosing. The brother of Pvt. John Rosing, his name appeared in Aufbau on January 12 and September 21, 1945. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery, at Section 12, Grave 1574. His matzeva appears below, in an image at BillionGraves.com taken by Liallee.

Born on December 3, 1923, PFC Rosing (serial number 35801894) was the son of Eugene and Herta (Herz) Rosing. The brother of Pvt. John Rosing, his name appeared in Aufbau on January 12 and September 21, 1945. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery, at Section 12, Grave 1574. His matzeva appears below, in an image at BillionGraves.com taken by Liallee.

______________________________

______________________________

Two men, among many.

______________________________

As part of my research about Jewish military service during the Second World War, I reviewed all issues of Aufbau published between 1939 and 1946 for articles relating to Jewish military service and identified pertinent news-items in the categories listed above. (Whew. It took a while…) These will be presented in a future set of blog posts, with – where necessary – English-language translations accompanying the German-language article titles.

I have not translated all, many, most, or even “a lot” of these articles; I leave that to the interested reader. (!)

Well, okay.

I’ve translated a certain select and compelling few, primarily concerning Jewish prisoners of war, and, the Jewish Brigade Group, which you may find of interest.

These will appear in the future.

______________________________

References

Maurice Derfler

B-24D 41-24269 (at Pacific Wrecks)

Aufbau

Aufbau (Digital), via Leo Baeck Institute (at Archive.org)

German Exile Journals, at German National Library (at Deutsche National Bibliothek)

German National Library Catalog Entry for “Aufbau”, at German National Library (at Deutsche National Bibliothek)

Aufbau (Wikipedia)

Aufbau (at Internet Archive)

German Exile Press (1933 – 1945) (Exilpresse digital – Deutschsprachige Exilzeitschriften 1933-1945) (Digital Exile Press – German Exile Magazines – 1933-1945)

Aufbau (at German Exile Press)

Aufbau (New York) at the Leo Baeck Institute

Leo Baeck Institute (at Wikipedia)

Leo Baeck Institute (New York)

Justin K. Thannhauser

Thannhauser Family (at Kitty Munson.com)

Thannhauser Family General Biography (at Wikipedia)

Justin K. Thannhauser and Guggenheim Museum (at Guggenheim Museum)

Thannhauser Collection (At Guggenheim Museum)

Thannhauser Collection (Book – At Guggenheim Museum)

Justin Thannhauser Obituary (The New York Times – 12/31/76) “Justin Thannhauser Dead at 84; Dealer in Art’s Modern Masters”

Uncle Heinrich and His Forgotten History (PDF Book) (by Sam Sherman)

Heinz H. Thannhauser

Für die Freiheit gefallen – Heinz Thannhauser (Article in Aufbau, at Archive.org)

Thannhauser, Heinz H – Biographical Profile at FindAGrave (at FindAGrave.com)

College Art Journal Volume 4, Issue 2, 1945 (Tribute to Heinz H. Thannhauser)

Furlough in Rome (Letter by Heinz H. Thannhauser in College Art Journal)

320th Bomb Group

320th Bomb Group Mission Reports (at 320th Bomb Group website (“When Gallantry was Commonplace”))

441st Bomb Squadron Insignia (at Vintage Leather Jackets)

Freeman, Roger A., Camouflage & Markings – United States Army Air Force 1937-1945, Ducimus Books Limited, London, England, 1974 (B-26 Marauder on pp. 25-48)

Tannehill, Victor C., Boomerang! – Story of the 320th Bombardment Group in World War II, Victor C. Tannehill, Racine, Wi., 1980. (Photo of “Becky” on page 115)

George E. Rosing

Ambrose, Stephen E., The Victors: Eisenhower and His Boys: The Men of WW II, Simon & Schuster, New York, N.Y., 2004.

George E. Rosing Cemetery Record (at Billion Graves)

George E. Rosing Cemetery Record (at FindAGrave)

103rd Infantry Division (103rd Infantry Division WW II Association)

103rd Infantry Division Award List for December 19, 1944 (103rd Infantry Division WW II Association)

12/30/17 – 661