“The clothes benefited the children,

but I was afraid so nobody would find out that they were bloodstained.

People are jealous today, there could be unnecessary talking in the house.

I cleaned them to some extent and removed the stains and then sold them straight away.

You can send something again, but prefer something less soiled.

You should be a little more careful and at least cut off the yellow stars…

I’m free for your next package…”

– Letter from a woman in Germany

to her husband in the Wehrmacht

on the Eastern Front, late 1943

______________________________

There are several ways to learn about a soldier’s life. Photographs provide a vision of – and into – the past. Documents, whether drawn up by a military unit or a civilian bureaucracy, disclose a man’s place in a organization, and reveal his actions over a span of time. The kaleidoscopic memories of his descendants, siblings, comrades and friends – each through their own unique and sometimes contradictory set of memories! – shed light on the inevitable complexity of his relationships with other human beings. But, there’s another, very well known way, through which a man can be understood, and remembered. At least in part. At least, for a little while. And that is through his own writing, whether in the form of letters or a diary.

It is the latter – for a Jewish soldier who eighty years ago served on the Eastern Front – which follows below.

The soldier’s name? Albert Elsner. Born in Ostrava, he served as an infantry Sergeant in the 1st Czechoslovak independent brigade. Wounded in action on November 6, 1943 during the Soviet Union’s re-taking of Kiev from German forces, he died in a military hospital three days later.

____________________

….The 1st Czechoslovak Independent Brigade in the battle for Kiev….

The 1st Czechoslovak Independent Brigade was formed on May 10, 1943 from “…the remnants of the 1st Czechoslovak Independent Field Battalion and the 1st Czechoslovak Reserve Regiment,” and under the command of Colonel (promoted to General on December 16, 1943) Ludvik Svoboda. The Brigade was incorporated into the 1st Czechoslovak Army Corps on April 10, 1944, upon which point it became one of the Corps’ four infantry brigades. (The newly formed 3rd and 4th were also infantry units, while the new 2nd was a paratroop brigade.) Also then created as part of the Corps were the 1st Czechoslovak independent tank brigade, 1st Czechoslovak independent engineering battalion, and two aviation units: the 1st Czechoslovak independent fighter air regiment, and, 1st Czechoslovak join air division. As such, both the 1st Czechoslovak Independent Brigade and 1st Czechoslovak Army Corps were military units of the Czechoslovak government-in-exile, fighting under Soviet Command alongside the Red Army.

____________________

From Czech Patriots, here’s general information about the Brigade during the time of Sergeant Elsner’s late-1943 service, with minor edits for clarity:

Commander: As of June 12, 1943: Colonel Ludvik Svoboda; General as of 12/16/43

Number of Personnel: As of September 30, 1943: 3,517 persons (including 82 women)

National Composition:

Czechs – 563 (16%)

Slovaks – 343 (9.7%)

Rusyns (Rusnaks) – 2,210 (62.8%)

Jews – 204 (5.8%)

Russians – 6

Poles – 5

Latvians – 2

Germans – 2

Hungarians – 13

…and…

“Soviets” (? – !) – 169 (4.8%)

Composition by Rank:

114 officers (including 21 officers of the Red Army)

25 technical-sergeants

3,378 soldiers (including 148 specialists from the Red Army for technical positions, which could not have been filled by Czech specialists)

Under command: 1st Ukrainian Front (Voronezh Front renamed (October 20, 1943) 1st Ukrainian Front under command of General Nikolay F. Vatunin)

Movements in 1943:

May 9 – September 30: Novohopersk

October 13: Voronezh railway – Kursk railway – Lgov railway

October 17: Vorozhba railway – Konotop railway – Bahmach railway – Nezhin railway – Priluki railway

October 23: Petrovka tank battalion – Novy Bykov tank battalion – Kazackoe – Kalita tank battalion – Ljutezh

November 4: Jablonka

November 6: Kiev – Borshchagovka

November 8: Vasilkov

During combat activities around Vasilkov area one group charged Chernahov village (November 9), and second group fought in Komunna Chajka and Petrivka (November 11)

December12: Kiev

____________________

Also from Czech Patriots, here’s a very (very) general overview of the Brigade’s actions during the battle for Kiev, again with edits for clarity:

Czechoslovak unit: 1st Czechoslovak independent brigade; in particular: 1st and 2nd infantry battalions, 1st tank battalion

Allied forces: Soviet 240th (931st Rifle Regiment) and 136th Rifle Divisions

Enemy forces: German 4th Tank Army, VII Corps. In particular, units of the 75th infantry Division and 7th Tank Division (V. Goncharov – Battle for the Dneiper – 1943)

Brief chronology: Czechoslovaks started the attack at 12:30, after overpass anti-tank group continued combat in Volejkovo area, Syrecks’ barracks and railway-track. With that on the right side a company of T-34 tanks and 2 [motorized?] rifle platoons captured the “Bolshevik” factory buildings (17:00); on the left a light tank company with T-70M tanks and infantry forced the Germans from the zoo area (18:00), further both tank companies checked the Kiev railway-station (20:00), and saved a bridge from destruction. At midnight the commander of the Soviet 38th Army Colonel General Moskalenko ordered to continue the attack in order to secure the bridge over the Dneiper River by day-break. At 02:00 Czechoslovak troops joined the final attack and were the first to reach the Dneiper River.

Kiev was liberated at 6:50 on the morning of November 6.

Czechoslovak casualties: 30 killed, 80 injured, 4 missing, 3 T-34 tanks lightly damaged

Enemy casualties: 630 soldiers killed, 1 Do-217 aircraft destroyed, 4-6 tanks, 2 “Ferdinand” howitzers [The Ferdinand was actually a heavy tank destroyer most notably used in the Battle of Kursk. Only 91 were manufactured. Wikipedia has negligible information about the tank destroyer’s post-Kursk use, simply stating that, “The surviving Ferdinands fought various rear-guard actions in 1943 until they were recalled to be modified and overhauled.”], 7 armor vehicles, 4 artillery batteries, 22 bunkers, 31 focuses of resistance, 41 heavy machine guns and 24 light machine guns were destroyed.

____________________

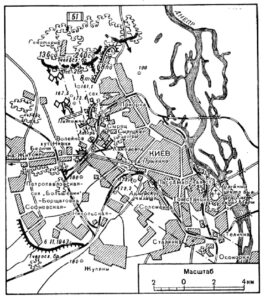

This map, which I believe (?) was originally published in General Ludvik Svoboda’s book От Бузулука до Праги (“Ot Buzuluka do Pragi“) (From Buzuluk to Prague) in Moscow in 1969, illustrates the relative positions of Soviet, Czech, and German forces during the Battle for Kiev. Consistent with the book’s year and place of publication, place names are in Russian. You can find this map at the Wikipedia entry for the (second) Battle of Kiev (1943).

The following map, from “Combats of the 1st Czechoslovak independent brigade – Battle of Kiev (03.-06.11.1943)“, also shows the disposition of Soviet, Czech, and German forces in and around Kiev in early November of 1943, but is adapted from the above map, with drafting by M. Gelbic. Geographic features are depicted a little differently, and the use of color reveals Soviet / Czech military forces much more clearly than the Soviet map itself. An interesting take-away from this map – as I interpret it – is that the Soviet offensive occurred from a general southwest to northeast axis, with German forces in Kiev backed against the Dneiper River to the east.

____________________

Specifically in terms of the relative proportion of Jewish soldiers serving, the 1st Czechoslovak Independent Brigade was – for a time – analogous to the 16th Lithuanian Rifle Division (see also ru.wikipedia), in that a notably high proportion of both units’ personnel were Jews. This situation arose not (emphatically not) through any ideological affinity for Jewish peoplehood, nationalism or Zionism on the part of the Soviet leadership, but instead – enabled by the intersection of geography, demography, and timing – the straightforward requirement for suitable, proficient, and motivated manpower when national survival was paramount.

Here’s the cover of Dorothy Leivers’ book about the 16th Rifle Division, Road to Victory – Jewish Soldiers of the 16th Lithuanian Division, 1942-1945, published by Avotaynu in 2009. The book’s a translation and revision of the Hebrew edition, published in Tel-Aviv in 1999 as Haderech el HaNitzachon. The original edition is in Yiddish, authored by Yakov Shein and Emanuel Vaserdam. Published in 1995, the title is Der Veg Zum Nitzkhon.

To be specific, as described at YadVashem and Wikipedia, the 16th Rifle Division (Russian: 16-я стрелковая Литовская Клайпедская Краснознамённая дивизия; romanized: 16-ya strelkovaya Litovskaya Klaypedskaya Krasnoznamonnaya diviziya; Hebrew: דיוויזיית הרובאים הליטאית ה-16; Lithuanian: 16-oji ‘Lietuviškoji’ divizija) was formed in late 1941 when the Soviet Union created ethnic-based divisions. “The purpose of the divisions was not only military but also political as their members were important for the planned post-war Sovietization of the occupied Baltic states.” In this framework soldiers assigned to the 16th Lithuanian Rifle Division had to be former citizens of Lithuania (including Jews) and ethnic Lithuanians who were residing on Soviet territory.

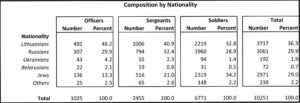

Figures for the division’s composition by nationality, as of January 1, 1943, are given by Aron Abramovich within In The Decisive War – The Participation of the Jews of the USSR in the War Against Nazism. Abramovich’s figures reveal that Jews then comprised 13.3% of the Division’s officers, 21% of its sergeants, and 34.2% of its soldiers, for an overall total of 29%, figures very close to those listed in Wikipedia. The division’s “composition by nationality” is presented in the table below, which I adapted from the original table (in Russian) in his book:

As described at Wikipedia, “In the first days of the battle [of Alekseyevka, where the Division first entered combat], the 16th Rifle Division withstood the attack of the German 383rd Infantry and 18th Panzer Divisions, that were accompanied by 120 planes. After suffering serious losses, the Soviet armies eventually emerged victorious. Between 20 February and 24 March 1943, the division lost 1,169 dead and 3,275 injured men.” Casualty lists in Road to Victory reveal that nearly 540 of those 1,169 combat deaths were Jews.

By war’s end, twelve soldiers of the division were awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union, of whom four were Jews, comprising:

Sergeant Kalman Shur (Калманис Маушович Шурас / Калман Моушович Шур)

Private (Gun-Layer; Gunner) Boris Tsindelis (Бори́с (Бе́рел) Изра́илевич Цинделис) – Killed in action

Corporal Girsh Ushpolis (Hirsz Uszpol / Григорий Саульевич Ушполис),

…and, most prominently…

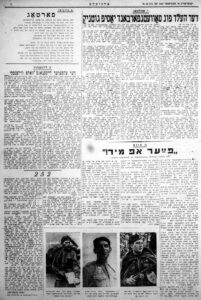

Vulf (Wolf) Vilenskii (Lithuanian: “Volfas / Vulfas Vilenskis“); Russian: Виленскис, Вольфас Лейбович (“Vilenkis, Volfas Leybovich”)), concerning whom information is abundantly available in print and electronic formats. Here’s one: The biography of Vilenski at Yad Vashem mentions an article by M. Liubetskis, “Der elterer leitenant Volf Vilenski” (Senior Lieutenant Vulf Vilenski), which was published in Eynikayt on September, 30, 1943.

For all you Yiddish speakers out there (are there any still?!), here’s that same article…

… and here’s the full page on which the article appeared (center left of page):

Briefly digressing, here are close-ups of the three photos at the bottom of the page, with translated captions:

“Commander of the naval guard aviation division Guard Major Khaim Khashper awarded the Order of Lenin.”

“The talented young surgeon Boris Prokhovnik, awarded the Order of the Fatherland War, 2nd Class.”

“The outstanding reconnaissance efreytor Shimen Roytman, awarded the Order of the Red Banner.”

____________________

__________

…..Now, back to the subject at hand: Sergeant Alfred Elsner’s diary…..

__________

____________________

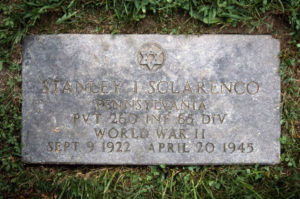

As for the Sergeant himself, unfortunately, I possess no further further information about him. However, there’s a possibility – however slight! – that a biographical record about him exists at Yad Vashem’s Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names, which – though not designed specifically as such – includes some records for Jewish soldiers who were killed in action while serving in the Allied armies. Though not specifically listed therein as a soldier, Yad Vashem has a record (database item “ID 8829252”) for an “Alfred Elsner” born on July 16, 1904, to Mojžiš and Bluma (Windholzova) Elsner, married to Ilona (Kleinová) Elsner, and a resident of Moravska Ostrava. But, there’s no information about his actual fate during the Second World War.

That man might be “our’ Sergeant Elsner, or, he might not be.

Brief excerpts from Sergeant Elsner’s diary can be found on pages 288 and 289 of Erich Kulka’s 1987 book Jews in Svoboda’s Army in the Soviet Union – Czechoslovak Jewry’s Fight Against the Nazis During World War II, which originally appeared in Hebrew in 1977, published by Yad Vashem’s Institute of Contemporary Jewry, and, Moreshet.

The moving and enigmatic nature of the excerpts sparked my curiosity, and through the archives of Yad Vashem I obtained a copy of the diary, specifically listed in the bibliography of Kulka’s book as “Diary of Sergeant Alfred Elsner, Records Group O.59 / 204, File Number O.33 / 204”. In actuality, the diary turned out to comprise 14 pages of text within a lengthier document encompassing 144 pages – all in typewritten German – entitled “Tatsachenbericht und Dokumentation: Betiligung der juedischen Soldaten in der tschechoslovakischen Armee in der Sowjetunion in den Jahren 1939 – 1945” or, “Factual Report and Documentation: Investigation of Jewish Soldiers in the Czechoslovak Army in the Soviet Union in the Years 1939 – 1945″, authored by Dr. Michal Stemmer – Stepanek.

The Elsner diary encompasses the time-frame of 30 September 1943 through November 8 of that year, the latter date one day before his Elsner’s death on November 9 (12th Cheshvan 5704). Of great importance, you’ll notice that it begins with a preface and ends with a discussion of the document’s literary history. These sections are by the above-mentioned Michal Stemmer (Stepanek), who served in a mortar company in the 1st Czechoslovak Independent Brigade, also in the Battle of Sokolovo in early March of 1943. As is revealed in the text, Dr. Stemmer received the diary from Karel Borský, a soldier in the Czech military who changed his name to “Kurt Biheller” after January, 1946, eventually attaining the rank of colonel in the postwar Czech armed forces.

To explain…

Borsky, in 1943 a Sergeant and deputy commander of the anti-tank company of the 1st field battalion, 1st Brigade, due to his skill in amateur photography – and under the suggestion of Sgt. Jaroslav Procházka – became a photographer for the brigade newspaper Naše vojsko v SSSR (Our Army in the USSR) because until then the Czech unit was dependent for battle photographs on Soviet photojournalists. The photo below, from Rota Nazdar (“Hello Company”), shows him standing before a T-34 tank (early version, with 76mm gun and “mickey-mouse” appearing turret hatches) prior to the battle for Kiev.

The caption? “Sergeant Karel Biheller-Borský (May 13, 1921–August 9, 2001), photographer 1. Czechoslovak brigade in the USSR before the attack on Kiev. On November 5, 1943, he was advancing directly in the first line of infantry of the 2nd Field Battalion and while taking documentary pictures of the battles, he was severely wounded by fragments of an artillery shell. His camera disappeared, so no photograph is known directly from the brigade’s battles near Kiev.” (Četař Karel Biheller-Borský (13. 5. 1921–9. 8. 2001), fotograf 1. čs. brigády v SSSR před útokem na Kyjev. Dne 5. 11. 1943 postupoval přímo v prvním sledu pěchoty 2. polního praporu a při pořizování dokumentárních snímků z bojů, byl těžce raněn střepinami dělostřeleckého granátu. Jeho fotoaparát zmizel a tak přímo z bojů brigády u Kyjeva není známa žádná fotografie.)

On November 5 1943, during a joint attack of the Soviet 51st Rifle Corps and the 1st Czechoslovak Army independent brigade upon German forces in Kiev, Borsky was advancing directly in the first line of infantry of the 2nd Field Battalion. While taking documentary pictures of the battle, he was seriously injured in the back by shrapnel from an exploding artillery shell. Borsky was brought to a field hospital and placed next to Platoon Commander Elsner. It was through this chain of events that Borsky (also from Ostrava) received Sergeant Elsner’s diary after the latter’s death, as well as the letter to an unknown German soldier, concerning which see the quotation at the top of this post … and more below.

In time, Borsky gave Elsner’s diary to Dr. Stemmer, who incorporated its text into his “Tatsachenbericht und Dokumentation: Betiligung der juedischen Soldaten in der tschechoslovakischen Armee in der Sowjetunion in den Jahren 1939 – 1945”, which (in the early 1970s?) was transferred to Erich Kulka, and in turn incorporated into the Archives of Yad Vashem (“Act No. E / 10-2, 3030/267-e”). You can access the Hebrew transcription of the document here.

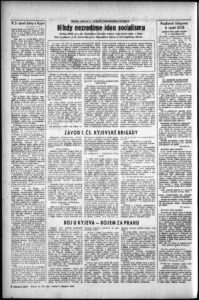

Dr. Stemmer’s concluding comments mention that an excerpt from Sergeant Elsner’s diary, with specific mention of himself, and Borsky / Biheller, was published in 1948, on the fifth anniversary of the battle for Kiev, in the official Czech military newspaper Obrana lidu (“The Defense of the People”). Given that the Soviet Army recaptured Kiev from German forces on the morning of November 6, 1943, and that digitized issues of this newspaper are available at DigitalNiknihovna.cz, I was able to locate the issue of November 6, 1948 (issue 259), which indeed (!) – on its first three pages – indeed commemorates that victory. The issue is six pages long; here are the first three pages:

I reviewed this issue thoroughly for any mention of the surnames Biheller, Elsner, and Stemmer, but – !?!?!? – I couldn’t find them or any mention of Elsner’s diary. Likewise, nothing relevant appeared in issue 260 (of November 7), which is 10 pages in length. For this I can offer no explanation except the passage of time and the uncertainty of human memory. Dr. Stemmer also mentions that the diary was also published in Obrana Lidu in 1956, but … I haven’t reviewed the issues for that year. Hey, 52 is a lot…

Which, brings up another and important facet of the lives of Biheller and Stemmer; of the history of the Jews of Czechoslovakian; an event that reflects the ongoing history and future of the Jewish people … “in general”.

Dr. Stemmer clearly mentions that both he and Biheller, despite their years of dedicated military service, were imprisoned and interrogated by “civilian and military organs” during the “political show trials of the fifties”, and suspended from military service. Though – timewise – he offers no specifics, I’m certain this occurred in the context of the political and social atmosphere surrounding the November 1952 show-trials of Rudolf Slánský and 13 other high-ranking Communist bureaucrats … who were (via Wikipedia) “…arrested and charged with being Titoists and “Zionists”. Those tried with Slánský were Bedřich Geminder, Otto Šling, André Simone, Karel Svab, Otto Fischl, Rudolf Margolius, Vladimir Clementis, Ludvik Frejka, Bedřich Reicin, Artur London, Eugen Löbl, and Vavro Hajdů.“

“Eleven of these men, including Slánský, were hanged at Pankrác Prison in Prague on 3 December, and three (Artur London, Eugen Löbl and Vavro Hajdů) were sentenced to life imprisonment. The state prosecutor at the trial in Prague was Josef Urválek.”

Not at all coincidentally, ten of these men were Jews.

“…the show trials occurred in the context of the February 1948 coup by which the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia took control of the country, which since the end of WW II had enjoyed limited democracy. The one-party state needed to manufacture enemies from within to justify its own existence. This paralleled the split between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, and, political trials (not necessarily antisemitic, per se) against alleged Titoist and Western imperialist elements in Albania, Bulgaria, and Hungary. Within the same context was the ostensibly anti-Zionist (in reality antisemitic) campaign which commenced in the Soviet Union subsequent to the reestablishment of Israel in 1948, and, the postwar destruction of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee.

“The trial was orchestrated (and the subsequent terror staged in Czechoslovakia) on the order of Moscow leadership by Soviet advisors, who were invited by Rudolf Slánský and Klement Gottwald, with the help of the Czechoslovak State Security personnel following the László Rajk trial in Budapest in September 1949. Klement Gottwald, president of Czechoslovakia and leader of the Communist Party, feared being purged and decided to sacrifice Slánský, a longtime collaborator and personal friend, who was the second-in-command of the party. The others were picked to convey a clear threat to different groups in the state bureaucracy. A couple of them (Šváb, Reicin) were brutal sadists, conveniently added for a more realistic show.”

Benjamin Ivry’s 2022 article in The Forward, “In the shadow of the Holocaust, a new Kafkaesque nightmare for Jews in Czechoslovakia – 70 years ago, 10 Jews were executed after the antisemitic Slánský trial“, provides a substantive and thought-provoking retrospective on the trial, and especially its impact on the Jews of Czechoslovakia. I also recommend Helaine Blumenthal’s Communism on Trial: The Slansky Affair and Anti-Semitism in Post-WWII Europe.

In any event, by the mid-50s, Borsky-Biheller and Stemmer-Stepanek were able to resume their lives.

Stemmer-Stepanek presents a very brief pre-war autobiography in the lengthy “Protocol” (Preface?) of Betiligung der juedischen Soldaten in der tschechoslovakischen Armee in der Sowjetunion in den Jahren 1939 – 1945”. A translation follows…

My name is Dr. Michael Stemmer Stepanek. I come from Moravská Ostrava and was born in the family of the Ostravian watchmaker Samuel Stemmer and his wife Regina, née Sandel, on April 26, 1907. After passing the matriculation examination at the state grammar school in Opava / Troppau /, I began studying law at Charles University in Prague in 1925. I graduated from the university with distinction. I then worked for two years as a trainee at the [firm of] Ostrava Advocates Dr. Adolf Loewinger, Dr. Paul Reik and Dr. Max Weber. A year later I practiced as an aspirant at the district court in Moravská Ostrava. From 1934 until the Munich Agreement in September 1938 I worked at a Prague university institute, which rigorously prepared students of the law faculty for state examinations. After the occupation of the Sudeten by Hitler’s-Germany in October 1938, I was dismissed from my post. I returned from Prague to Moravská Ostrava back to my parents and siblings. My brother Sale Stemmer, who is 2 years younger, and my sister Nathalie, who is 10 years younger, decided to emigrate to Palestine [sic]. I stayed with my parents in Moravská Ostrava. On March 14, 1939, I witnessed the invasion of Hitler’s army. In the night of the same day, without saying goodbye to my parents, I fled across the border to Poland, a few hundred meters from the house where I was born. I never saw my parents again. They went the way of suffering of the 6 million European Jews who fell into the hands of the Nazi murderers, to a fatal end.

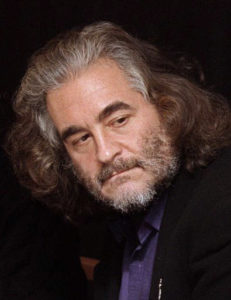

From Yad Vashem, this photo (contributed by Meira Idelstein) shows Michal Stemmer-Stepanek and Ilya Ehrenburg in September of 1945.

Dr. Stemmer-Stepanek evidently made aliyah to Eretz Israel, for in “Tatsachenbericht und Dokumentation: Betiligung der juedischen Soldaten in der tschechoslovakischen Armee in der Sowjetunion in den Jahren 1939 – 1945” he lists his 1970 address as Zahala-Neve Sharret 55/1 in Tel Aviv.

Further information about Biheller will appear in a future post. For now, here’s an excerpt from his biography at cs.wikipedia:

“In 1946, Kurt Biheller … became an information officer and served in Tábor. At the end of 1948, he was transferred to Prague and subsequently to the Ministry of National Defense. He then served as a military and air attaché in Budapest. In 1951, he was dismissed from his post, fired from the army and arrested. He was imprisoned and interrogated in the Ruzyne prison and the infamous Domečko. No charges were brought against him and he was released without reason in April 1952. He worked in the construction industry and was drafted back into the army in 1956. He served in Čáslav, then as military attaché and ambassador to the Commission of Neutral States to the United Nations in Korea. He served the end of his career in the Department of Foreign Relations at the General Staff. He attained the rank of colonel. In retirement, he became an official of the Czech Union of Freedom Fighters and the Czechoslovak Legionary Community. He published memoirs and autobiographical books. After the creation of the Army of the Czech Republic, he was promoted to the rank of brigadier general. He died after a long illness on August 9, 2001.”

The full document “Tatsachenbericht und Dokumentation: Betiligung der juedischen Soldaten in der tschechoslovakischen Armee in der Sowjetunion in den Jahren 1939 – 1945” is available via Yad Vashem’s database under the item record “Testimony of Michael Michal Stemmer-Stepanek, regarding his experiences in the Czechoslovakian regiment in the context of the Red Army in Bosoluk, Kiev, Czechoslovakia and Slovakia“, where it comprises a total of 201 pages, the first 44 in Hebrew, followed by a Erich Kulka’s 13 page introduction (in German), and Stemmer-Stepanek’s actual 144-page-long text. Given that Yad Vashem’s database displays digitized documents – if, such as this one, they comprise multiple pages! – in sets of 32 images, this full document (both Hebrew and English text) comprises 7 sets of images, with Elsner’s diary appearing as the last page of set “4”, and the first 12 pages of set “5”.

____________________

__________

____________________

I’m currently working on a translation of “Tatsachenbericht und Dokumentation: Betiligung der juedischen Soldaten in der tschechoslovakischen Armee in der Sowjetunion in den Jahren 1939 – 1945”. (!)

If I get the thing completed (!?!), maybe I’ll post it… (!!)

Some day. (!!!)

____________________

__________

____________________

…..And so, on to the translated diary of a forgotten soldier…..

Here’s Sergeant Elsner’s diary, and, Michael Stemmer-Stepanek’s comments. I’ve organized the text such that for each day’s entry, the English-language translation appears first, followed by the German-language version in dark blue, both languages in (this) big Merriweather font. The comments of Michael Stemmer-Stepanek, are in (this) smaller Arial font.)

Here we go.

ON THE RIGHT SHORE OF THE DNEIPER

According to Operation Plan Number 1, our Czechoslovak Brigade was to go to the front in 8 individual transports from 30 September to 3 October 1943. The final station was only known to the commanders. The soldiers only knew, that they were driving to the Dnieper.

Our mortar company left Novochopjorsk on 1 October with the transport of the 2nd Battalion. The trip from Novochopjorsk to the unloading station at Prikuly lasted 12 days…

From Prikuly we marched to the Dnieper on foot. 150 kilometers in two days! We set up camp in dense, tall spruce forests on the left bank of the powerful Ukrainian stream. Small huts, probably made up of thin spruce trunks, covered with shrubs and foliage, and a home for the next few days. In the night from the 22nd to the 23rd of October we crossed the river over a pontoon bridge.

At 8 o’clock in the morning of 3 November 1943, a beautiful sunny day, the attack on Kiev begins. At 2 o’clock in the afternoon our company crossed the railway line on the outskirts of the city. The entire night we fought bitter battles with desperately fighting units of the Waffen SS. In the morning hours of 6 November 1943, the Russian tank divisions, together with tanks and infantry units of the 1st Independent Czechoslovak Brigade of the USSR under the command of Colonel Ludvik Svoboda, freed the capital of Ukraine – Kiev. The Soviet government valued the combat operations of the Czechoslovak brigade very highly. It awarded orders and medals to 42 officers – among whom were almost all the Jewish commanders, 64 non-commissioned officers and 29 private soldiers. The President of the Czechoslovak Republic honored 41 members of the brigade who sacrificed their lives in the battle for Kiev with the “Czechoslovak War Cross 1939” – “In Memoriam”. There are among them Jewish soldiers, Dr. Oskar Bachrich, Corporal Leo Heller, Corporal Jan Fischer, Corporal Jan Hausner, Lieutenant and battery commander Erwin Falter … other Jewish non-commissioned officers and also the young platoon commander Alfred Elsner from Ostrava …

From day one, when he boarded the military train in Novochopjorsk, platoon commander Elsner kept a diary until one day after the liberation of Kiev, when the relentless death of a soldier tore the quill from his hand.

I have before me the small thin booklet. It is already yellowed; torn at the corners; I carried it in the field bag the long fight way from the Dnieper to Prague, an expensive legacy of my young countryman, combat companion and friend. The writing has already heavily faded; at times I can only compile words and sentences from the individual letters with great effort. I quote the short diary as a shocking literal confession of a young Czechoslovak Jew to freedom; to the love of life. A commitment of the indomitable will to fight against tyranny. – [Dr. Michael Stemmer (Stepanek)]

AM RECHTEN UFER DES DNEJPR

Laut Operationsplan Nummer 1 sollte unsere tschechoslovakische Brigade in 8 Einzeltransporten in den Tagen vom 30 September bis 3 Oktober 1943 an die Front fahren. Die Endstation kannten nur die Kommandanten. Die Soldaten wussten nur, dass sie zum Dnejpr fahren.

Unsere Granatwerferkompanie verliess Novochopjorsk am 1 Oktober mit dem Transport des 2 Bataillons. Die Fahrt von Novochopjorsk in die Ausladestation Prikuly dauerte 12 Tage…

Von Prikuly marschierten wir bis zum Dnejpr zu Fuss. 150 Kilometer in zwi Tagen! In dichten, hohen Fichtenwaeldern an linkin Ufer des maechtigen ukrainischen Stromes schlagen wir under Feldlager auf. Kleine Huetten, notduerftig zusammengesimmert aus duennen Fichtenstaemmen, bedeckt nit Reisern und Laub sing undser Heim fuer die naechsten Tage. In der Nacht vom 22 auf den 23 Oktober ueberschreiten wir ueber eine Pontonbruecke den Strom.

Um 8 Uhr Frueh des 3 November 1943, einem schoenen sonnigen Tag, beginnt der Angriff auf Kiew. Gegen 2 Uhr Nachmittag ueberquert unsere Kompanie die Eisenbahnlinie am Rande der Stadt. Die ganze Nacht fuehren wir erbitterte Kaempfe mit verzweifelt sich wehrenden Einheiten der Waffen SS. In den Morgenstunden des 6 November 1943 befreiten die russischen Panzerdivisionen zusammen mit Panzer und Infanterieeinheiten der 1 selbstaendigen tschechoslowakischen Brigade in der UDSSR unter dem Befehl von Oberst Ludvik Svoboda die Hauptstadt der Ukraine – Kiew. Die Sowjetregierung wertete die Kampfhandlungen der tschechoslowakischen Brigade sehr hoch. Sie zeichnete 42 Offiziere – unter denen sich fast alle juedischen Kommandanten befanden, 64 Unteroffiziere und 29 einfache Soldaten met orden und Medaillen aus. Der President der Tschechoslowakischen Republik zeichnete mit dem “Tschechoslowakischen Kriegskreuz 1939” “in memoriam” 41 Angehorige der Brigade aus, die im Kampf um Kiew ihr Leben geopfert haben. Es sind unter ihnen die juedischen Soldaten, Dr. Oskar Bachrich, der Gefreite Leo Heller, der Gefreite Jan Fischer, der Korporal Jan Hausner, der Leutnant und Batteriekommandant Erwin Falter…weitere juedische Unteroffiziere und auch der junge Zugsfuehrer Alfred Elsner aus Ostrau…

Vom ersten Tag an, de er in Novochopjorsk den Militaerzug bestieg fuehrte Zugsfuehrer Elsner ein Tagebuch bis einen Tag nach der Befreiung von Kiew, als ihm der unerbittliche Soldatentod die Feder aus der Hand riss.

Iche habe vor mir das kleine duenne Heftchen. Es ist schon vergilbt, an den Ecken zerfranst, ich trug es in der Feldtasche den langen Kampfweg von Dnjepr bis Prag, ein teures Vermachtnis meines jungen Landmannes, Kampfgefaehrten und Freundes. Die Schrift ist schon stark verblasst, zeitweise kann ich nur mit groesster Anstrengung aus den einzelnen Buchstaben Worte und Saetze zusammenstellen. Ich zitiere das kurze Tagebuch woertlichen erschuetterndes Bekenntnis eines jungen tschechoslowakischen Juden zur Freiheit, zur Liebe zum Leben. Ein Bekenntnis des unbeugsamen Willens gegen die Tyrannei zu kaempfen.

September

30 Thursday

On to the west!

Morning – the last defile in the city of Novochopjorsk.

Preparation for departure.

15.45 hours – the 1st Field Battalion begins.

16.00 – Moving off to the station.

24.00 – Departure of our military train. We introduce supervisory service – KOPL / Heavy machine guns and assault guns / In each wagon two light machine guns. A continuous observation service on the locomotive – telephone connection. We sing, peel potatoes, carry water to the kitchen, we eat and dream.

30 Donnerstag

Auf nach Westen!

Vormittag – das letzte Defillee in der Stadt Novochopjorsk.

Vorbereitung zur Abfahrt.

15.45 Uhr – Antritt des 1. Feldbataillons.

16.00 – Abmarsch auf den Bahnhof.

24.00 – Abfahrt unseres Militaerzuges. Wir fuehren Aufsichtsdienst ein – KOPL / Schwere Maschinengewehre und Sturmgeschuetze / In jedem Waggon zwei leichte Maschinengewehre. Einen staendigen Beobachtungsdienst auf der Lokomotive – Telephonverbindung. Wir singen, schaelen Kartoffel, tragen Wasser in die Kueche, wir essen und träumen.

October

1 Friday

We drive all night and all day [to] Abramavka – first station -. Here the soldiers Blaha and Mortin are left behind. They went to get water … but they caught up with us in a Russian military train in Skalovka station … Rain and sunshine alternate.

1 Freitag

Wir fahren die ganze Nacht und den ganzen Tag Abramavka – erste Station -. Hier bleiben die Soldaten Blaha und Mortin zurueck. Sie gingen Wasser holen… aber sie holten uns mit einem russischen Militaerzug in der Station Skalovka ein… Regen und Sonnenschein wechselt.

2 Saturday

24.00 hours. Everywhere traces of strong bombardment and destruction can be seen.

6.00 hours departure.

2 Samstag

24.00 Uhr. Ueberall sind Spuren starken Bombardierens und von Vernichtung zu sehen.

6.00 Uhr Abfahrt.

3 Sunday

Station “Kostomyj”. We are still standing. Stricter security measures against air strikes. I issue [an] order, prohibiting leaving the wagons. It is … It is a nice, sunny day. Departure at 02.00 hours. We are already in the Kursk district. The education officers work diligently to dispel boredom from the soldiers. They distribute handwritten front newspapers; magazines, among us. In all cars musicians play on …

3 Sonntag

Station “Kostomyj”. Wir stehen noch immer. Verschaerfte Sicherheitsmassnahmen gegen Luftangriffe. Ich gebe Anordnungen heraus, Verbote die Waggone zu verlassen. Es ist… Es ist ein schoener, sonniger Tag. Abfahrt um 02.00 Uhr. Wir sind schon im Bezirk Kursk. Die Erziehungsoffiziere arbeiten fleissig, um den Soldaten die Langweile zu vertreiben. Sie verteilen unter uns Frontzeitungen, Zeitschriften, die mit der Hand geschrieben sind, Nachrichten. In allen Waggonen spielen Musikanten auf…

8 Friday

We arrived in the area where in July the Red Army opened the counter-offensive and began its successful advance to the west. We stand in the station Karenowo all night. My train has guard duty against airstrikes. Departure. Gunfire was heard at night. The mood of the soldiers has improved significantly as they hear the news that the Red Army has passed the Dneiper in battle. Along the railway line are long rows of boxes of German ammunition. In the terrain we recognize the network of German and Russian barbed wire …

8 Freitag

Wir kamen in die Gegend an, in der im Juli die Rote Armee die Gegenoffensive eroeffnete und ihren erfolgreichen Vormarsch nach dem Westen begann. Wir stehen die ganze Nacht in der Station Karenowo. Mein Zug hat Wachdienst gegen Luftangriffe. Abfahrt. In der Nacht war Geschuetzfeuer zu hoeren. Die Stimmung der Soldaten hat sich bedeutend gebessert, als sie die Nachricht erfahren, dass die Rote Armee den Dnjeper im Kampf ueberschritten hat. Entlang der Eisenbahnlinie liegen lange Reihen von Kisten mit deutscher Munition. Im Terrain erkennen wir das Geflecht deutscher und russischer Drahtverhaue…

9 Saturday

Vorozda – a bigger station – shot to pieces. We stand from midnight. A military train from our brigade has caught up with us. In the night a “Fritz” flew. There was also another military train of our brigade. The music is playing again. Departure at 13.00 hours. The stations we pass through are bombed out …

9 Samstag

Vorozda – ein groessere Station – zerschossen. Wir stehen von Mitternacht. Es hat uns ein Militaerzug unserer Brigade eingeholt. In Nacht flog ein “Fritz”. Es kam auch noch ein weiterer Militaerzug unserer Brigade an. Die Musik spielt wieder. Abfahrt um 13.00 Uhr. Die Stationen, die wir durchfahren, sind aus bombardiert…

10 Sunday

We continue our journey with smaller stays. We are preparing to take out the wagon …

12.00 hours – Bachmac. The brigade takes in an urn a little earth of the battlefield on which the Czech legionnaires fought against the Germans 25 years ago. The urn with the historical earth is destined for the monument of the unknown soldier in Prague … At 23.00 hours – alarm. A German Messerschmitt has attacked one of our military trains in the station, not even 500 meters away from our train … with 8 bombs he hit a car. 8 to 10 soldiers were killed …

10 Sonntag

Wir setzen unsere Fahrt mit kleineren Aufenthalten fort. Wir bereiten uns zum Auswaggonieren vor…

12.00 Uhr – Bachmac. Die Brigade nimmt in eine Urne ein wenig Erde des Schlachtfeldes mit, auf dem vor 25 Jahren die tschechischen Legionaere gegen die Deutschen gekaempft haben. Die Urne mit der historischen Erde ist fuer das Denkmal des Unbekannten Soldaten in Prag bestimmt… Um 23.00 Uhr – Alarm. Ein deutscher Messerschmitt hat einen unserer Militaerzuege in der Station ueberfallen, nicht ganze 500 Meter von unserem Zuge entfernt… mit 8 Bomben traf er einen Waggon. Dabei wurden 8 bis 10 Soldaten getoetet…

At this point, the entry in the diary of platoon commander Elsner does not coincide with the historical reality. This inaccuracy can be explained by the fact that the train driver did not mark every day entered in his diary, which consisted of loose, not stapled sheets, with the correct date, or even left out a few days altogether. It follows logically, that platoon commander Elsner, in the military hospital to which he was transported after his severe wound, endeavored to supplement the missing pages from his memory. – [Dr. Michael Stemmer (Stepanek)]

The bombing of the German aircraft on the Czechoslovak military train did not take place on Sunday October 10, 1943, but on Tuesday the 12th October. By a direct hit in a four-axle wagon of the 2nd Battery, the Jewish battery commander Engineer Lieutenant Erwin Falter from Orlova near Ostrava, 8 NCOs and 30 soldiers were killed. Through the same direct hit, three NCOs and six other soldiers were mortally wounded in the adjacent wagons of the 1st and 3rd batteries. The total losses of the 1st Czechoslovak firefighting division on 12th October 1943 – 1 officer, 12 non-commissioned officers / of which 5 Jews / and 37 soldiers / of which 11 Jews /.

An dieser Stelle stimmt die Eintragung im Tagebuch von Zugsfuehrer Elsner nicht mit der historischen Wirklichkeit ueberein. Diese Ungenauigkeit ist mit der Begruendung zu erklaeren, dass der Zugsfuehrer nicht jeden, in seinem, aus losen, nicht zusammengehefteten Blaettern bestehenden Tagebuch eingetragenen Tag, mit dem richtigen Datum bezeichnete, oder sogar einige Tage ueberhaupt ausliess. Es ergibt sich die logische Schlussfolgerung, dass Zugsfuehrer Elsner sich bemuehte, im Militaerspital, in das er nach seiner schweren Verwundung ueberfuehrt wurde, die fehlenden Blaetter aus seinem Gedaechtnis zu ergaenzen.

Der Bombenangriff des deutschen Flugzeuges auf den tschechoslowakischen Militaerzug erfolgte naemlich nicht am Sonntag den 10.Oktober 1943, sondern am Dienstag den 12.Oktober. Durch einen Volltreffer in einen vierachsigen Waggon der 2.Batterie wurde der juedische Batteriekommandant Ing. Leutnant Erwin Falter aus Orlova bei Ostrava, 8 Unteroffiziere und 30 Soldaten getoetet. Durch denselben Volltreffer wurden in den benachbarten Waggonen der 1. und 3. Batterie 3 Unteroffiziere und 6 weitere Soldaten toedlich verwundet. Die Gesamtverluste der 1.tschechoslowakischen Geschuetzdivision betrugen am 12.Oktober 1943 – 1 Offizier, 12 Unteroffiziere / davon 5 Juden / und 37 Soldaten / davon 11 Juden /.

11 Monday

Five more alarms were announced. Then a group of our soldiers helped to dispose of the wreckage of the wagons and repair the ruined railway line. At 6.00 hours we drove out of the station. At 9:00 am we arrived in Prikuly. Also this station was like the rest burned down to the ground. The city was otherwise unscathed. Near the train station we saw a lot of airfields … On our way we are accompanied by Russian planes of the most modern types. What a joy a man feels, if he feels safe through their wings. We marched for 26 kilometers into the village of P. The inhabitants believed for a moment that we were Germans, but afterwards they welcomed us … The Germans withdrew from this village only three weeks ago.

11 Montag

Noch fuenfmal wurde Alarm verkuendet. Dann half eine Gruppe unserer Soldaten die Truemmer der Waggone zu beseitigen und die zerstoerte Eisenbahnlinie wieder in Stand zu setzen. Um 6.00 Uhr fuhren wir aus der Station heraus. Gegen 9.00 Uhr kamen wir nach Prikuly. Auch diese Station war wie die uebrigen ausgebrannt bis auf die Grundmauern. Die Stadt blieb sonst unversehrt. In der Naehe des Bahnhofes sahen wir viele Flugplaetze… Auf unseren weiteren Weg begleiten uns russische Flugzeuge der modernsten Typen. Was fuer eine Freude empfindet ein Mensch, wenn er sich durch ihre Fluegel gesichert fuehlt. Wir marschierten gegen 26 Kilometer in das Dorf P. Die Einwohner glaubten im ersten Moment, dase wir Deutsche seien, aber nachber nahmen sie uns lieb auf… Aus diesen Dorf haben sich die Deutschen erst vor drei Wochen zurueckgezogen.

13 Wednesday

At 9.00 hours departure from P-Nova Alexejowkraet; foot care; lunch. On the way we meet a guard soldier of the 25th Soviet Division, which was our neighbor in the struggle for Sokolovo. The men from the liberated Russian cities and villages submit themselves to the Assent Commissions. In the evening dusk we reach the village Kozacka. Three soldiers are quartered in a little house, we rest comfortably. After a long time a warm meal again, after we have so much longing …

13 Mittwoch

Um 9.00 Uhr Abmarsch aus P-Nova Alexejowkraet, Fusspflege, Mittagessen. Auf dem weiteren Wege begegnen wir einem Gard-soldaten der 25.sowjetischen Division, die unser Nachbar im Kampf um Sokolovo war. Die Maenner aus den befreiten russischen Staedten und Doerfern stellen sich den Assentkommissionen. In der Abend daemmerung erreichen wir das Dorf Kozacka. Je drei Soldaten werden in einem Hauschen ein-quartiert, wir ruhen uns bequem aus. Nach langer Zeit wieder einmal ein warmes Essen, nachdem wir schon so starke Sehnsuckt haben…

15 Friday

I sleep in a different place than last night. Daily program: Weapons cleaning …

Italy is at war with Germans. In the afternoon we receive instructions for the employment of the crew, for alertness and further security measures. In the evening there is the thunder of cannon and the drone of aircraft engines in the distance.

15 Freitag

Ich schlafe auf einem anderen Ort, als vorige Nacht. Tagesprogramm: Waffenreinigung…

Italien hat Deutschen den Krieg. Nachmittag erhalten wir Instruktionen feur die Beschaeftigung der Mannschaft, fuer Alarmbereitschaft und weitere Sicherheitsmassnahmen. Am Abend ist in der Weite gedaempfter Kanonendonner und Droehnen von Flugzeugemotoren zu heeren…

16 Saturday

I take on the duties of the supervisory officer of our district.

Two NCOs and a soldier got drunk at night. The corporal was demoted, all were put into the kitchen …

We have already been allowed to write letters … In the evening, at 21 hours 20 minutes, the alarm is announced. I am still in the service of the supervisory officer. It gets around that two German saboteurs were caught with a radio station. Some German planes have allegedly landed on Russian airfields …

16 Samstag

Ich uebernehme den Dienst des Aufsichtsoffziers unseres Quartieres.

In der Nacht haben sich zwei Unteroffiziere und ein Soldat betrunken. Der Korporal wurde degradiert, alle wurden ins Kitchen gesteckt…

Es ist uns schon erlaubt worden Briefe zu schreiben… Am abend, um 21. Uhr 20 Minuten wird Alarm verkuendet. Ich bin noch immer im Dienst des Aufsichtoffiziers. Es spricht sich herum, dass zwei deutsche Diversanten ausgeruestet mit einer Funkstation gefangen wurden. Einige deutsche Flugzeuge sind angeblich auf russischen Flugplaetzen gelandet…

17 Sunday

I have morning service. In the afternoon, with the company commanders, I carry out a reconnoitering of the terrain. In the evening, the company is having fun. We sing Russian, Czech and Slovak songs with Russian girls …

I am very tired after the service; I would like to sleep. But in the evening many young girls came to our house. There also came our battalion commander, Staff Captain Kholl. We chatted happily until late into the night.

17 Sonntag

Ich habe vormittag Dienst. Nachmittag fuehre ich mit den Kompaniekommandenten eine Rekognoszierung des Terraines durch. Am Abend geht es bei der Kompanie lustig zu. Mit den russischen Maedchen singen wir russische, tschechische und slowakische Lieder…

Ich bin nach dem Dienst sehr muede, ich moechte gerne schlafen. Aber am Abend kamen in unser Häuschen viele junge Maedchen. Es kam auch unser Bataillonskommandant, Stabskapitaen Kholl. Wir unterhielten uns froehlich bis spaet in die Nacht.

18 Monday

We are recommencing reconnoitering of the terrain. At 10 hours comes the order to pack. The battalion prepares to march off …

At 15.15 hours departure … The girls accompany us far after the village …

18 Montag

Wir fuehren von neuem eine Rekogniszierung des Terrains durch. Um 10.Uhr kommt der Befehl zum Packen. Das Bataillon bereitet sich zum Abmarsch vor…

Um 15.15 Uhr Abmarsch… Die Maedchen begleiten uns weit hinter das Dorf…

22 Friday

Today four men returned to our train …

Departure at 15.00 hours … At midnight we set up quarters in the forest. At night, there are fiery flashes of exploding shells and bombs … At 10.20 hours our company jumps over a pontoon bridge to the Dnieper …

22 Freitag

Heute kehrten zu unserem Zug vier Mann zurueck…

Abmarsch um 15.00 Uhr… Um Mitternacht schlagen wir im Wald Quartier auf. In der Nacht sind feurige Blitze explodierender Granaten und Bomben zu sehen… Um 10.20 Uhr uebreschreitet unsere Kompanie ueber eine Pontonbruecke den Dnjeper…

27 Wednesday

The mortars of our brigade / 2nd Platoon of my Company, Commander, Second Lieutenant Herrman Steinberg – note of Dr. Michael Stemmer – began a successful action against the Hitler soldiers. Strong enemy artillery fire at night. The first strong frost begins. In the canteen this morning there was ice instead of tea.

27 Mittwoch

Die Granatwerfer unserer Brigade / der 2.Zug meiner Kompanie, Komandant, Unterleutnant Herrman Steinberg – Annerkung Dr.St.M. – begannen eine erfolgreiche Aktion gegen die Hitlersoldaten. In der Nacht starkes feindliches Artilleriefeuer. Es beginnen die ersten starken Froste. In der feldflasche war heute morgen statt Tee Eis.

28 Thursday

We are constantly in the reserve of a Soviet division. We practice close combat in wooded terrain. In the evening, the artistic ensemble of the Ukrainian Front gave a concert in our bunkers. The bunker in which the actors, singers and dancers performed is close to the German positions … During the entire duration of the concert, mutual artillery and mortar fire …

We are very impatient. Not far from our positions, the Russians fight with the Nazis in the first line. When do we intervene in the fight? Why should we, the Czechoslovak soldiers, stay in the reserve in the fight for Kiev?

28 Donnerstag

Wir sind staendig in der Reserve einer sowjetischen Division. Wir ueben Nahkampf im bewaldeten Terrain. Am Abend gab das kuenstlerische Ensemble der Ukrainischen Front in unseren Bunkern ein Konzert. Der Bunker, in dem die Schauspieler, Saenger und Taenzer auftraten, ist nahe den deutschen Stellungen… Waehrend der ganzen Dauer des Konzertes hielt gegenseitiges Artillerie und Granatwerferfeuer an…

Wir sind schon sehr ungeduldig. Nicht weit von unseren Stellungen kaempfen die Russen mit den Nazis in der ersten Linie. Wann greifen wir in den kampf ein? Warum sollen gerade wir, die tschechoslowakischen Soldaten im Kampf um Kiew in der Reserve bleiben?

31 Sunday

Occupation: Assault units practice battle in the forest. The Russians bring more and more guns, grenade launchers, “Katyushas” and ammunition in the front line. Rumors are spreading that two German spies, dressed in Russian uniforms, were caught in the section of our battalion …

31 Sonntag

Beschaeftigung: Angriffsabteilungen ueben Kampf im Walde. Die Russen bringen immer mehr Geschuetze, Granatwerfer, “Katjuschas” und Munition in die erste Linie. Es werden Geruechte verbreitet, dass im Abschnitt unseres Bataillons zwei deutsche Spione, angezogen in russische Uniformen, gefangen wurden…

November

2 Tuesday

Activity: advance through the forest, fight for a settlement. We are watching German aircraft, dive-bomb ground targets and cover them with machine-gun fire. In the afternoon German planes bombard the firing positions of our battalion. Our aircraft defense has its hands full of work.

2 Dienstag

Beschaeftigung: Vormarsch durch den Wald, Kampf um eine Siedlung. Wir beobachten deutsche Flugzeuge, die im Sturzflug auf Erdziele Bomben werfen und sie mit Maschinengewehrfeuer belegen. Nachmittag bombardieren deutsche Flugzeuge die Feuerstellungen unseres Bataillons. Unsere Flugzeugabwehr hat volle Haende Arbeit.

3 Wednesday

At 7 hours combat readiness is announced. At 8 hours the artillery preparation begins. The decisive attack on Kiev begins. It thunders and roars from all sides … and the political officer to the squad … At 9 hours moving off to the defensive positions.

3 Mittwoch

Um 7 Uhr frueh wird Kampfbereitschaft verkuendet. Um 8.Uhr beginnt die Artillerievorbereitung. Es beginnt der entscheidende Angriff auf Kiew. Es donnert und droehnt von allen Seiten… und der politische Offizier zur Mannschaft… Um 9.Uhr Abmarsch in die Verteidigungspositionen.

4 Thursday

The whole night we go through defense lines from which the Germans have withdrawn the day before. Everywhere Soviet tanks, guns and “Katyushas” have been through passages developed by Soviet pioneers in densely forested areas. The forests are full of corpses of German soldiers. We “hurry” ourselves and at the same time we prepare for the attack. We are only a few meters from the first front line …

Intensified security service …

An enormous multitude of Russian soldiers, equipped with modern weapons. We are supposedly only 5 kilometers away from Kiev …

Enemy mortars explode around our defenses …

4 Donnerstag

Die ganze Nacht gehen wir durch Verteigungslinien vor, aus denen sich die Deutschen einen Tag vorher zurueckgezogen haben. Ueberall sind sowjetischen Panzern, Geschuetzen und “Katjuschas” von sowjetischen Pionieren Durchgaenge durch dichtbewaldetes Gebeit ausgebaut worden. Die Waelder sind voll von Leichen deutscher Soldaten. Wir “igeln” uns ein und gleichzeitig bereiten wir ins zum Zngriff vor. Wir sind nur einige wenige Meter von der ersten Frontlinie entfernt…

Verstaerkter Wachdienst…

Eine ungeheure Menge russicher Soldaten, ausgeruestet mit modernen Waffen. Wir sind angeblich nur noch 5 Kilometer von Kiew entfernt…

Rings um unsere Verteidigungsstelllung explodieren feindliche Granaten…

5 Friday

“Katyushas” are firing at the Germans. Our mortars participate in the fire. Scout troops of our brigade penetrate deep into the German positions … Soviet “Shturmoviks” [see wikipedia, and, ru.wikipedia] fly over the German positions. The Germans unleashed a hurricane of anti-defense fire against them. Our heads are ringing from the thunder of the cannon.

At 11 hours moving off …

We attack in the direction of – Kiev. Our battalion forms the reserve of the 1st Czechoslovak Brigade. Everything: automobiles; guns; tanks; people, swim in a powerful stream – everything moves forward. Enemy mortars fall into our ranks. However, we continue to penetrate. Already we have made the first line … We storm forward inexorably … ”

In this phase of the attack on Kiev I am only a few meters away from Platoon Commander Elsner. Covered by our tanks, our company rushes in inexorably with its train. Towards evening we stop on a hill in front of the city. In front of our eyes, there is a wide view of the valley, where the city lies, surrounded by dark swirling smoke. We descend into the valley and march to the city. On the streets we see bodies of Hitler’s soldiers; shattered and charred German tanks.

Platoon Commander Elsner stops in front of an automobile of the German army post office. Its engine is still working; out of the broken window protrudes a frozen hand, holding out a leather bag. Elsner opens the cabin door and the body of a German soldier falls on the ground. From the shot-through canteen on the belt black steaming coffee slowly flows out. Elsner opens the bag and letters drop out of it. They are from Germany. “What do German women write to their men and sons at the front?”, says the young train leader. He opens a letter and reads its contents. He reads a long time – then he silently hands it to me. The letter contains only a few sentences. I quote them literally: _____ mistakes … – [Dr. Michael Stemmer (Stepanek)]

“The clothes benefited the children, but I was afraid so nobody would find out that they were bloodstained. People are jealous today, there could be unnecessary talking in the house. I cleaned them to some extent and removed the stains and then sold them straight away. You can send something again, but prefer something less soiled. You should be a little more careful and at least cut off the yellow stars… I’m free for your next package…”

Suddenly I feel a burning pain in my knee. I fall to the ground; I try to sit up, it cannot be … My soldiers put me on a wagon of the mortar company of Lieutenant Bedrich and with other wounded soldiers they took me to our field hospital … From there we are evacuated into the hinterland … What a pity; how would I like to be with my boys in Kiev …

5 Freitag

“Katjuschas” feuern auf die Deutschen. Unsere Granatwerfer beteiligen sich an dem Feuer. Spaehtruppen unserer Brigade dringen tief in die deutschen Stellungen ein… Sowjetische “Sturmowiky” fliegen ueber die deutchen Stellungen. Die Deutschen entfesselten gegen sie einen Uragan [ouragan – Fr.] von Abwehrgeschuetzfeuer. Es droehnt [dröhnt] uns der Kopf von dem Kannonengebruell.

Um 11.Uhr Abmarsch…

Wir greifen in der Richtung – Kiew – an. Unser Bataillon bildet die Reserve der 1.tschechoslowakischen Brigade. Alles, Automobile, Geschuetze, Panzer, Menschen schwimmen in einem maechtigem Strom – alles bewegt sich nach vorn. In unsere Reihen fallen feindliche Granaten. Wir dringen jedoch weiter vor. Schon haben wir die erste Linie uebreschritten… Wir stuermen unaufhaltsam vorwaerts…”

In dieser Phase des Angriffes auf Kiew bin ich nur einige wenige Meter von Zugsfuehrer Elsner entfernt. Gedeckt durch unsere Panzer, stuermt unsere Kompanie mit seinem Zug unaufhaltsam vor. Gegen Abend machen wir auf einem Huegel vor der Stadt halt. Vor unseren Augen bietet sich ein weiter Ausblick in das Tal, wo die Stadt liegt, eingehuellt in dunkle Rauchschwenden. Wir steigen ins Tal nieder und marschieren zur Stadt. Auf den Strassen sehen wir Leichen von Hitersoldaten, zerschossene und verkohlte deutsche Panzer.

Zugsfuehrer Elsner bleibt vor dem Automobil der deutschen Feldpost stehen. Sein Motor arbeitet noch, aus dem zerbrochenen Fenster ragt eine erstarrte Hand, eine Ledertasche haltend, heraus. Elsner oeffnet die Kabinentuer und der Koerper eines deutschen Soldaten faellt auf die Erde. Aus der durchschossenen Feldflasche am Riemen fliesst langsam schwarzen dampfender Kaffe heraus. Elsner oeffnet die Tasche und es fallen aus ihr Briefe heraus. Sie sind aus Deutschland. “Was schreiben deutsche Frauen ihren Maennern und Soehnen an die Front?”, sagt der junge Zugsfuehrer. Er macht einen Brief auf und liest seinen Inhalt. Er liest lange – dann reicht er mir ihn schweigend. Der Brief enthaelt nur einige Saetze. Ich zitiere sie woertlich: ___en Fehlern…

“Die Kleider sind den Kindern zu gute gekommen, aber ich bekam Angst, damit niemand daraufkommt, dass es Blutflecken waren. Die Menschen sind heute neidisch, es koennte im Hause zu unnoetigen Rederei en kommen. Ich habe sie einigermassen gereinigt und die Flecken beseitigt und dann lieber gleich verkauft. Du kannst wieder etwas schicken, aber lieber etwas weiniger verschmutztes. Du solltest etwas vorsichtiger sein und wenigstens die gelben Stern abtrennen… Ich freie mich auf dein naechstes Pakett…”

Ploetzlich fuehle ich einen brennenden Schmerz im Knie. Ich falle zur Erde, versuche mich aufzurichten, es geht nicht… Meine Soldaten legten mich auf einen Wagon der Granatwerferkompanie von Unterleutnant Bedrich und mit anderen verwundeten Soldaten brachten sie mich in unser Feldlazarett… Von dort werden wir ins Hinterland evakuiert… Schade, wie gerne waere ich mit meinen Jungen in Kiew…

6 Saturday

I am in the field hospital …

6 Samstag

Ich bin im Feldlazarett…

7 Sunday

I am in the field hospital …

7 Sonntag

Ich bin im Feldlazarett…

8 Monday

I’m in the field hospital … The letter I took from the German soldier in Kiev has been given to platoon commander Karel Biheller. He should send it to the editors of our front newspaper. Too bad, that I see so poorly … I cannot read the paper … maybe the letter has already appeared …?

Here ended the diary of Platoon Commander Elsner. He could not continue it. He succumbed to his serious injuries. – [Dr. Michael Stemmer (Stepanek)]

8 Montag

Ich bin im Feldlazarett… Den Brief, den ich dem deutschen Soldaten in Kiew abgenommen habe, habe Zugsfuehrer Karel Biheller gegeben. Er soll ihn die Redaktion unserer Frontzeitung schicken. Schade, dass ich so schlecht sehe…ich kann die Zeitung nicht lessen… vielleicht ist der Brief schon erschienen…?

Hier endete das Tagebuch des Zugsfuehrer Elsner. Er konnte es nicht weiter fuehren. Er erlag seinen schweren Verletzungen.

Platoon Commander Karel Biheller, a young Jewish tradesman from Ostrava, was wounded in my dugout on the first day of the attack on Kiev by a German shell. While he was brought to the field hospital with severe injuries, where he was lying next to Platoon Commander Elsner, I got off with some abrasions … The letter, that Elsner had taken in my presence from the dead German soldier in Kiev, Karel Biheller gave me in liberated Prague after the war. I have published it with an excerpt from the diary of Platoon Commander Elsner in the central organ of the Czechoslovakian People’s Army “Obrana lidu” on the occasion of the fifth anniversary of the battle for Kiev. This article displayed me and Karel Biheller; at the time I was a senior officer of the Czechoslovak army, in the period of the political show trials of the fifties; the accusation “Zionist propaganda”; interrogation by civilian and military security organs – temporary, short imprisonment, suspension of active military service for me – and Karel Biheller, the mediator of the letter of the Nazi soldier killed in the fight for Kiev, a long-term imprisonment …

Only after my and Colonel Karel Biheller’s rehabilitation in 1956 was the diary of platoon commander Elsner allowed to be published again in the Czechoslovak army press. – [Dr. Michael Stemmer (Stepanek)]

Zugsfuehrer Karel Biheller, ein junger juedischer Handelsangestellter aus Ostrava, wurde in meinen Schuetzengraben am ersten Tage des Angriffes auf Kiew von einer deutschen Granate verwundet. Waehrend er mit schweren Verletzungen in das Feldlazarett ueberfuehrt wurde, wo er neben Zugsfuehrer Elsner zu liegen kam, kam ich mit einigen Hautabschuerfungen davon… Den Brief, den Elsner in meiner Gegenwart des toten deutschen Soldaten in Kiew abgenommen hatte, gab mir Karel Biheller nach den Krieg im befreiten Prag. Ich habe ihn mit einen Auszug aus dem Tagebuch von Zugsfuehrer Elsner im Zentralorgan der tschechoslowakischen Volksarmee “Obrana lidu” anlaesslich des 5 Jahrestages Kampfes um Kiew veroeffentlicht. Dieser Artikel trug mir und Karel Biheller, damals such schon wie ich ein hoher Offizier der tschechoslowakischen Armee, in der Zeit der politischen Schauprozesse der fuenfziger Jahre den Vorwurf “Zionistischer Propaganda”, Verhoere durch zivile und militaerische Sicherheitsorgane – mir zur zeitweilige, kurze Inhaftierun, Suspendierung vom aktiven Militaerdienst – und Karel Biheller, dem Vermittler des Briefes des nazistischen, im Kampf um Kiew getoeteten Soldaten, eine langjaehrige Kerkerhaft ein…

Erst nach meiner und Oberst Karel Bihellers im Jahre 1956 erfolgten Rehabilitierung, durfte das Tagebuch von Zugsfuehrer Elsner wiederum in der tschechoslowakischen Armeepresse veröffentlicht werden.

_________________________

References, references, references!

Websites

1st Czechoslovak Independent Brigade, at…

… CzechPatriots (via Archive.org (“Czechoslovak Military Units in the USSR (1942-1945)”)

1st Czechoslovak Army Corps, at…

… CzechPatriots (via Archive.org (“Czechoslovak Military Units in the USSR (1942-1945)”)

1st Czechoslovak Army Corps in the Soviet Union, at…

Czechoslovak Independent Tank Brigade in the USSR [československá samostatná TANKOVÁ BRIGADA v SSSR], at…

Ludvik Svobda, at…

… Ludvík Svoboda.cz (via Archive.org; “Ludvík Svoboda – army general – president of Czechoslovakia 1968 – 1975”)

Karel Borský (Kurt Biheller), at…

… cs.wikipedia (“Karel Borský”)

… Valka.cz (“Biheller, Kurt (Borský, Karel)”)

… Rotanazdar.cz (“Četař Karel Biheller-Borský”)

Michael (Michael) Stemmer-Štěpánek, at…

… ArmedConflicts (“Stemmer (Štěpánek), Michal”)

… Yad Vashem (“Testimony of Michael Michael Stemmer-Stepanek, regarding his experiences in the Czechoslovakian regiment in the context of the Red Army in Bosoluk, Kiev, Czechoslovakia and Slovakia”, specifically, pages 19 through 23)

Central Military Archive of the Czech Republic, at…

Obrana lidu (Newspaper “The Defense of the People”; ISSN 0231-6218), at…

The Second Battle of Kiev, at…

Jewish Soldiers in World War Two, at…

… Yad Vashem (Jewish Soldiers in the Allied Armies)

… Yad Vashem (Jews in the Red Army, 1941-1945)

Yad Vashem Archives, Jerusalem, Israel

Diary of Sergeant Alfred Elsner, Records Group O.59 / 204, File Number O.33 / 204

Expert’s Report Concerning “Factual Report and Documentation: Investigation of Jewish Soldiers in the Czechoslovak Army in the Soviet Union in the Years 1939 – 1945” – Author: Dr. Michael Stemmer – Stepanek; Arranged by: Erich Kulka

Deposited: Yad Vashem Archives, Act No. E / 10-2, 3030/267-e

Books

Абрамович, Арон (Abramovich, Aron), В Решающей Войне : Участие и Роль Евреев СССР в Войне Против Нацизма (In the Decisive War : The Participation and Role of the Jews of the USSR in the War Against Nazism), Тель-Авив, Израиль (Tel-Aviv, Israel), 1982 (OCLC 10304647)

Gilbert, Martin, Atlas of Jewish History, Dorset Press, 1976

Kulka, Erich, Jews in Svoboda’s Army in the Soviet Union – Czechoslovak Jewry’s Fight Against the Nazis During World War II, University Press of America, Lanham, Md., 1987

Leivers, Dorothy, Road to Victory – Jewish Soldiers of the 16th Lithuanian Division, Avotaynu, Bergenfield, N.J., 2009

Свобода, Людвик [Svoboda, Ludvik], От Бузулука до Праги [Ot Buzuluka do Pragi / From Buzuluk to Prague], Воениздат, Moskva [Voenizdat, Moskva / Military Publishing House, Moscow] 1969 [OCLC 5330613; Translated from Czech]

[Vojenské osobnosti československého odboje. 1939–1945. Vojenský historický ústav Praha. Vojenský historický ústav Bratislava. Praha, květen 2005 (Ministerstvo obrany České republiky – Agentura vojenských informací a služeb, 2005 ISBN 80-7278-233-9)]

Military Personalities of the Czechoslovak Resistance. 1939–1945. Military Historical Institute Prague. Military Historical Institute Bratislava. Prague, May 2005 (Ministry of Defense of the Czech Republic – Military Information and Services Agency, 2005 ISBN 80-7278-233-9)

Zide v boji a odboji trojjazycne – Rezistence československých Židů v letech druhé světové války [The Jews in Battle and in The Resistance – The Resistance Efforts of the Czechoslovak Jews during World War II], An exhibition initiated by the Jewish Community in Prague under the leadership of Ing. Tomáš Jelínek, Held by the Association of Jewish Soldiers and Resistance Fighters, Maiselova 18, 110 00 Prague 1; Poprvé byla tato výstava představena v roce 2005 v prostorách Poslanecké sněmovny České republiky [This exhibition was first presented in 2005 in the premises of the Chamber of Deputies of the Czech Republic]

Journal Articles

Binar, Aleš, Participation of Czechoslovaks in The Battle of Kyiv 1943, Military Historical Bulletin (СТОРІНКАМИ ДРУГОЇ СВІТОВОЇ ВІЙНИ), 110-130, V 41, N 3, 2021 (DOI: 10.33099/2707-1383-2021-41-3-110-131 / УДК: 94(477)(-25)(1943))

Gitelman, Zvi, “Why They Fought: What Soviet Jewish Soldiers Saw and How It Is Remembered”, NCEER [National Council for Eurasian and East European Research Working Paper] Contract Number: 824-03g, September 21, 2011