Among the ninety-odd obituaries for Jewish servicemen published in The New York Times during the Second World War, were three for Jewish soldiers born in Germany. Whether these servicemen were selected for news coverage specifically because of that ancestry – or – this number by chance approximated the relative proportion of German-born Jews in the American armed forces – or – whether the Times’ reporting about these men was influenced by other publications, such as Aufbau – or? – whether this was attributable to social connections with the families of these soldiers on the part of the Times’ staff (which was evidently the case for Army Air Force Captain William Hays Davidow) is unknown.

In any event, thus far in this project I’ve presented the story of T/4 Alexander H. Hersh, who was killed in action in the European Theater on January 21, 1945.

In the future, I hope to present information about Berlin-born 2 Lt. Alfred Kupferschmidt, who, as a member of the 116th Reconnaissance Squadron, 101st Cavalry Group, was killed by artillery fire on February 25, 1945, and reported upon in the Times the following May 6. Like many of the soldiers profiled in this series of posts, Kupferschmidt’s name never appeared in American Jews in World War II.

But, until then, here’s a “third” German-born Jewish soldier: Private First Class Harry Kaufman, 32817804. Born in Bielefeld in 1925, he was the son of Sally and Elsie Kaufman, his family residing at 3593 Bainbridge Avenue in the Bronx. A member of the 254th Infantry Regiment of the 63rd Infantry Division, his name appeared in a Casualty List published on May 10, 1945. He was the subject of (brief) news stories in the Times on May 23, the Daily News on May 17, and Aufbau on May 4. His name appears on page 359 of American Jews in World War II. A recipient of the Purple Heart, he is buried at the Lorraine American Cemetery at Saint Avold France, in Grave 32 Row 16, Plot D.

Here is his very brief obituary, as it appeared in the Times:

Refugee in U.S. in 1936 Is Casualty in Germany

Pfc. Harry Kaufman was killed in action in Germany on April 17, according to word received by his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Sol Kaufman, of 3593 Bainbridge Avenue, the Bronx.

He came to this country in 1936 from Germany with his parents and tried to enlist in the armed forces in 1942, but was not accepted. He was a student at the Bronx High School of Science when drafted in February, 1943.

Private Kaufman was injured while a paratrooper. He later was transferred to the infantry.

Here’s Private Kaufman’s portrait, as published in the Times.

Here’s the first page of Aufbau’s May 4 issue. The headlines are self-explanatory even if one doesn’t know German!

And, here’s the paper’s last page, on which appeared information about military awards, military accomplishments, and inevitably, casualties. The practice of publishing such news items specifically on te final page of every issue page was established in the newspaper as early as 1944. In this instance, the news article about Harry Kaufman appears in the upper left corner.

Once again, Harry Kaufman’s portrait. This is the same image which appeared in the Times, albeit the latter published only a cropped version of the photo. Here, Harry’s glider infantry shoulder patch is visible on his left shoulder, indicating that this picture was taken before his assignment to the 63rd Infantry Division.

Here’s a better view of the shoulder insignia of the glider infantry…

…and here’s the shoulder patch – an original from WW II – of the United States Army’s 63rd Infantry Division.

A transcript and translation of Aufbau’s very brief news item about Harry Kaufman’s death in battle….

Für die Freiheit gefallen

Pfc. Harry Kaufman

ist am 18. April in Alter von 20 Jahren “irgendwo in Deutschland” gefallen. Er wurde in Bielefeld geboren und kam 1936 mit seinen Eltern nach New York. Ende Februar 1943 wurde er in die Armee eingezogen und im November 1944 nach Uebersee geschickt. Er gehörte der 7th Army an.

Fallen for Freedom

Pfc. Harry Kaufman

fell “somewhere in Germany” on April 18th at the age of 20. He was born in Bielefeld and came to New York with his parents in 1936. At the end of February 1943 he was drafted into the army and sent overseas in November 1944. He was a member of the 7th Army.

__________

This Oogle map of the New York metropolitan area shows the location of the Kaufman family’s residence at 3593 Bainbridge Avenue in the Bronx…

…and, here’s a larger scale Oogle map of the same area.

__________

Harry Kaufman’s matzeva at the Lorraine American Cemetery, photographed by FindAGrave researcher Thomas Welsch.

Some other Jewish military casualties on Tuesday, April 17, 1945 (Yom Shishi, 5 Iyar, 5705) include…

– .ת. נ. צ. ב. ה –

תהא

נפשו

צרורה

בצרור

החיים

United States Army (Ground Forces)

Butler, Manfred, PFC, 42136245, BSM, Purple Heart (Italy)

10th Mountain Division, 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment

Born in Germany, in 1926

Mrs. Natalie J. Butler (mother), 863 Hunts Point Ave., New York, N.Y.

Florence American Cemetery, Via Cassia, Italy – Plot F, Row 14, Grave 25

Aufbau 11/9/45

American Jews in World War II – Not listed

Cohn, Irving, PFC, 32272686, BSM, Purple Heart (at Ie Shima, Okinawa)

77th Infantry Division, 307th Infantry Regiment, I Company

Born 5/22/10

Mrs. Mary Cohn (mother), Evelyn (sister), 825 Gerard Ave., Bronx, N.Y.

Mount Hebron Cemetery, Corona, N.Y.

American Jews in World War II – 293

Goltman, David Monroe, PFC, 42126851, Purple Heart

97th Infantry Division, 303rd Infantry Regiment

Born Brooklyn, N.Y, 1/24/26

Mr. and Mrs. Charles and Jeanette Goltman (parents), 1675 54th St., Brooklyn, N.Y.

Cemetery location unknown – buried 1/7/49

Casualty Lists 5/9/45, 6/8/45

The New York Times (Obituary Section) 1/6/49

American Jews in World War II – 329

Hayek, Teddy K., PFC, 32681062, Purple Heart

30th Infantry Division, 117th Infantry Regiment, Medical Corps

Mr. Albert K. Hayek (brother), 239 West 103rd St., New York, N.Y.

(also) 4 W. 109th St., New York, N.Y.

Long Island National Cemetery, Farmingdale, N.Y. – Section H, Grave 9586

Casualty Lists 5/14/45, 5/28/45

American Jews in World War II – 342

____________________

Kiel, David (David Bar Yosef), PFC, 32863120, Purple Heart, 1 Oak Leaf Cluster

34th Infantry Division, 168th Infantry Regiment, K Company (Signal Corps)

Wounded previously, approximately on 1/15/44 and 7/9/44

Mr. Joseph Kiel (father), PFC Bernard Kiel, and, Hyman Kiel (brothers), 37-07 61st St., Woodside, N.Y.

Born New York, N.Y., 9/18/24

Mount Hebron Cemetery, Flushing, N.Y. – Society T.D. Young Men, Block 50, Reference 2, Section A-C, Line 7, Grave 39

Casualty Lists 2/15/44, 9/9/44, 5/12/45

Long Island Star Journal 6/13/45

American Jews in World War II – 361

A pensive mood: Private Kiel’s portrait, as it appeared in the Long Island Star Journal on June 13, 1945…

…which accompanied the following news item:

Killed in Italy

Private First Class David Kiel was killed in Italy, his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Kiel of 37-07 61st St., Woodside, have been informed by the War Department. He was extending a communications line to a forward position when he was fatally wounded by bomb fragments, his father and mother were told. He has been buried in Italy. His brother, Bernard, is a private first class in the Army in New Guinea. Another brother is a seaman, 2/C, at the Sampson Naval Training Center.

__________

David’s matzeva at Mount Hebron Cemetery, photographed by FindAGrave researcher Ronzoni.

PFC David Kiel’s story continued, at least indirectly, at least for a time, at least (and at most) for a few years beyond 1945: In 1949, Jewish War Veterans Post named in his memory was established in Woodside. The following three news articles, from the (good ‘ole!) Daily News, and, Long Island Star Journal, report on this event:

JWV to Install

Daily News (New York)

March 13, 1949

Joseph Newman, commander, heads a staff of officers to be installed tonight by the David Kiel Jewish War Veterans Post of Woodside. The installation will be held in Paprin’s restaurant, 60-21 Roosevelt Ave., Woodside, Queens.

__________

Long Island Star Journal

March 1, 1949

Organizing New Jewish War Veterans Post in Woodside

Four Woodsiders go over plans for the David Kiel Jewish Veterans Post of Woodside institution ceremony, to be held March 13 in Paprin’s restaurant, Woodside. They are (seated, left to right) Raymond Newman of 59-16 Woodside Avenue, chairman, and Philip Paprin, the restaurant owner, and (standing, left to right) Henry Rosenblatt, Queens J.W.V. Musical Director, and, Rabbi Yehudah Pehkin of the Woodside Jewish Center. The program includes a dinner and installation of officers.

__________

DAVID KIEL POST TO SEAT OFFICERS

Long Island Star Journal

March 10, 1949

The David Kiel Jewish War Veterans Post will be formally instituted Sunday night in Paprin’s restaurant, 60-21 Roosevelt avenue, Woodside. Joseph Newman of 59-16 Woodside avenue, Woodside, commander, and other officers will be installed.

They include Bernard Kiel and Jordan Rolnick, vice-commanders; Arthur Schulman, quartermaster; Isadore Kamen, adjutant; Harold Morrison, officer-of-the-day; Dr. Arthur Gordon, surgeon; Milton Hong, chaplain; Wallace Green, officer of the guard; Joseph Zarchy, historian; Joseph Honig, patriotic instructor; Arthur Zarchy, service officer, and Stanley Ganz, Max Schaffer and William Bell, trustees.

Raymond Newman is the arrangements committee chairman. Dancing will follow the installation.

It would seem that by now, the year 2021, the David Kiel Jewish War Veterans Post no longer exists: Searching the very phrase “David Kiel Jewish War Veterans Post” in DuckDuckGo, and that o t h e r search engine – y’know, that one in Menlo Park? – yields parallel results: “No results found for “David Kiel Jewish War Veterans Post””, and, “It looks like there aren’t many great matches for your search,” respectively. This should not be too surprising, given the passage of time and the fragility of human memory, let alone the enormous sociological, demographic, and technological changes that have transpired in the United States, and the rapidly atrophying “West” in general, since the late 1940s.

If such forces have affected the Western world in general, so are they similarly affecting the Jews of the United States. As for the future of the Jews in the United States? About that I make no predictions, other than to say that while history never repeats itself congruently, there is a similarity in patterns of thought and behavior across time and space, for human nature remains unchanged. And so, the following two essays – by Joel Kotkin and Caroline Glick, despite all their likely ideological differences! – deserve equal contemplation.

And in time, not just contemplation.

Why American Jews are Looking to Israel

The Threats American Jewry Refuses to Face

____________________

Klein, Jerome R. (Yosef Bar Yakov Klein), Pvt., 13179290

Died Non-Battle

Born 1924

Mr. and Mrs. Jacob E. (7/1/92-5/6/69) and Minnie (1/12/99-8/14/89) Klein (parents), Philadelphia, Pa.

Montefiore Cemetery, Jenkintown, Pa. – Section 4, Lot 353, Grave 1; Date of burial unknown

American Jews in World War II – Not listed

Here’s the Klein family plot at Montefiore Cemetery in Jenkintown, Pennsylvania. Jerome’s resting place is at the left.

Jerome Klein’s matzeva. Information concerning the specific military unit to which he was assigned is unavailable. Given that he’s categorized as having “Died Non-Battle”, I believe his military service was limited to the United States.

____________________

Krieger, Morris J., PFC, 35517750, BSM, Purple Heart (at Mount Serra, Tuscany, Italy)

10th Mountain Division, 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment, F Company

Born 1917

Mrs. Emilie Krieger (wife); Charles Krieger (son; YOB 1942), William J. Krieger (brother); Mrs. Sadie Thomas and Mrs. Mary Winston (sisters), 110 Hill St., Bay City, Mi.

Florence American Cemetery, Florence, Italy – Plot B, Row 6, Grave 5

Cleveland Press & Plain Dealer – 5/23/45

American Jews in World War II – 492

____________________

London, Maurice (Moshe Bar Benyamin), PFC, 33786461, Purple Heart (Germany)

283rd Field Artillery Regiment, A Battery

Born 10/18/19, Philadelphia, Pa.

Mrs. Norma London (wife); “Ganelle” / “Janella”?) (daughter), 3209 W. Dauphin St., Philadelphia, Pa.

Benjamin London (father); Billie and Lena (sisters)

Mount Sharon Cemetery, Springfield, Pa. – Section L, Lot 450, Grave 2; Buried 9/26/48

The Jewish Exponent 5/18/45, 6/8/45, 10/1/48

The Philadelphia Inquirer 5/12/45, 9/24/48

Philadelphia Record 5/12/45, 5/28/45

American Jews in World War II – 537

Private Maurice London’s matzeva. Examination of the upper part of the column reveals that a photographic portrait set in a ceramic mount may once have been attached to it, in the custom of many matzevot from the 20s through the 40s. That picture has been lost in the decades since the late 1940s.

____________________

Paul, Solomon, PFC, 33053838, BSM, Purple Heart

77th Infantry Division, 307th Infantry Regiment

Born 4/25/20

Mr. and Mrs. Louis and Rose Paul (parents), 2732 North Front St., Philadelphia, Pa.

Honolulu Memorial, Honolulu, Hawaii – Plot E-170; Buried 1/3/49

Philadelphia Inquirer 6/11/45

Philadelphia Bulletin and Philadelphia Record – 6/12/45

American Jews in World War II – 452

Penso, Stanley, PFC, 42183678, Purple Heart (Germany)

Born 1926 (?)

Mrs. Ray Penso (mother), 1460 Grand Concourse, New York, N.Y.

City College of New York Class of 1947

Cemetery location unknown

Casualty List 5/19/45

American Jews in World War II – 404

____________________

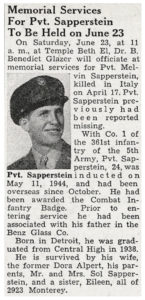

Sapperstein, Melvin S., Pvt., 36978192, Purple Heart

91st Infantry Division, 361st Infantry Regiment, I Company

Born Detroit, Michigan, 8/7/20

Mrs. Theodora (Alpert) Sapperstein (wife), 2923 Monterey St., Detroit, Mi.

Mr. Sol Sapperstein (father); Eileen (sister), 2923 Monterey, Detroit, Mi.

Machpelah Cemetery, Ferndale, Mi. – Section 6, Lot 36, Grave 413D; Buried 11/28/48

Casualty List 5/22/45

The Jewish News (Detroit) 6/15/45, 11/26/48

Baltimore Jewish Times 4/27/45

American Jews in World War II – 195

Announcement of a memorial service for Private Sapperstein, published in The Jewish News on June 15, 1945.

Private Sapperstein’s matzeva, as photographed by FindAGrave contributor KChaffeeB. His name appears atop the stone in Hebrew characters, but the text cannot be resolved due to the angle of the image.

____________________

Schwartzman, Henry, Pvt., 32899677, Silver Star, Purple Heart

14th Armored Division, 48thy Armored Tank Battalion

Mrs. Sylvia Schwartzman (wife), 1559 40th St., Brooklyn, N.Y.

Tablets of the Missing at Lorraine American Cemetery, St. Avold, France

Casualty List 5/31/45

American Jews in World War II – 436

Unger, Irwin M. (Ezriel Mordechai Ben Yehuda Tzvi), PFC, 42064656, Silver Star, Purple Heart (Germany)

8th Armored Division, 49th Armored Infantry Battalion, A Company

Born 1926

Mr. and Mrs. Joseph (Juda) [1892-3/13/41] and Molly M. (Gottesman) [1897-2/17/77] Unger (parents), 133 Clarke Place, New York, N.Y.

Baron Hirsch Cemetery, Staten Island, N.Y. – First Nadworner Sick Benevolent Association (matezva is missing)

Casualty List 5/18/45

American Jews in World War II – 463

United States Army Air Force

First Lieutenant Nathaniel Norman Shane

– Murdered while Prisoner of War –

On the 17th of April, 1945, First Lieutenant Nathaniel Norman Shane (0-781687), a co-pilot in the 327th Bomb Squadron, 92nd Bomb Group, 8th Air Force, was one of three airmen – from a crew of eight – who were able to parachute from their B-17G Flying Fortress (43-39110, UX * E, otherwise known as Naughty Nancy), after their aircraft was struck by another 327th Bomb Squadron B-17G (44-8903, the un-nicknamed UX * G) in a mid-air collision during a mission to Dresden, Germany.

Missing Air Crew Report 14053, for Naughty Nancy, reveals that the plane’s other two survivors were the pilot, 1 Lt. John W. Paul., Jr., of Dundalk, Maryland, and tail gunner, S/Sgt. Peter B. Taylor, of Worcester, Massachusetts. Of the eight crew members aboard UX * G, covered in MACR 14052, there were two survivors: Pilot 1 Lt. Arthur H. Heuther, and co-pilot 2 Lt. Frank K. Jones.

Shane landed uninjured in the vicinity of the German town of Reinhardtsgrimma*, south of Dresden, and was soon captured by a member of the SS named “KIRSTEN”.

As angry civilians arrived on the scene, Shane was murdered: He was shot several times by Kirsten.

As documented in Shane’s Individual Deceased Personnel File (IDPF) – in the context of the discovery and identification of Shane’s body in 1948 – “The [Parish] Preacher [“Hinke”, who reported the shooting] evidently seemed to know more than he was willing to talk about.”

A review of documents in Shane’s IDPF, and, NARA Records Group 153 (Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General), shows that the case was not investigated beyond the context of recovering Shane’s body. The limiting factor, of course, was the Cold War (the first Cold War?!): Correspondence in 2017 with the German Central Office of the National Judicial Authorities for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes revealed that the, “…events and persons described … are unknown or unidentifiable. This, et. al., is due to the fact that both Reinhardtsgrimma and Dippoldiswalde are located in Saxony and thus lay in the Soviet occupation zone or the GDR, for which the central office was not responsible due to the German division until 1989/90.”

As recorded in Shane’s IDPF, the last information about Kirsten – first name unknown – was that as of February, 1948, the former member of the SS was jailed in the town of Dippoldiswalde.

Beyond that, there is nothing.

Shane’s body was in time returned to the United States. He was buried at King Solomon Memorial Park, in Clifton, New Jersey (Section Lebanon, Block 66, Grave 43) on April 23, 1950.

Having flown 27 missions, Nathaniel Shane received the Purple Heart, Air Medal, and three Oak Leaf Clusters. Born on June 6, 1922, in Manhattan, he was married, his wife Beatrice residing at 1231 Boynton Avenue, in the Bronx. His parents, Harry A. and Sadie Shane, and his brother, Sidney, lived at 810 Hunts Point Avenue, (also) in the Bronx.

While Lt. Shane’s name appeared in a Casualty List published on May 22, 1945, his name – like the names of many American Jewish WW II military casualties – is absent from American Jews in World War II, as attested to by many prior posts at this blog.

Strangely, while the National WW II Memorial hosts an Honoree page for Lieutenant Shane created by his brother, with the statement, “AIR CORPS PILOT. HE WAS KILLED ON APRIL 17, 1945 IN A RAID OVER DRESDEN, GERMANY. RECEIVED THE HONORABLE SERVICE LAPEL BUTTON, EUROPEAN-AFRICAN-MIDDLE EASTERN CAMPAIGN MEDAL WITH 1 BRONZE STAR, AND THE WWII VICTORY MEDAL,” (accompanied by the above photo of the Lieutenant), Nathaniel Shane’s name is absent from that website’s National Archives Registry. (I’ve encountered this discrepancy with other record searches at the National WW II Memorial website.)

Akin to the post about Corporal Jack Bartman, I hope to create a separate post about Nathaniel Shane’s story in the future.

“…a former municipality in the district of Weisseritzkreis in Saxony in Germany located near Dresden. On 2 January 2008, it merged into the town Glashütte.

This Oogle map image shows Reinhardtsgrimma in relation to Dresden.

…and, Oogling on in, here’s a map of the town at a larger scale.

Soviet Union

Red Army

U.S.S.R. (C.C.C.Р.), Red Army [РККА (Рабоче-крестьянская Красная армия)]

Altman, Boris Shlemovich – Guards Senior Sergeant [Альтман, Борис Шлемович – Гвардии Старший Сержант]

385th Guards Heavy Self-Propelled Artillery Regiment

Telephone Operator [Телефонист]

Born 1924; Tetievskiy Raion

Beloshevskiy, David Borisovich – Junior Lieutenant [Белошевский, Давид Борисович – Младший Лейтенант]

6th Guards Tank Corps, 51st Guards Tank Brigade

Tank Commander [Командир Танка]

Born 1922; city of Serdobsk

Memorial Book of Jewish Soldiers Who Died in Battles Against Nazism – 1941-1945 – Volume I – 126

Dekhtyar Iosif Markovich – Lieutenant [Дехтяр, Иосиф Маркович – Лейтенант]

Battery Commander – Self-Propelled Guns [Командир Батареи – Самоходной Установки] – SU-76 [СУ-76]

Armored and Mechanized Troops, 1221st Self-Propelled Artillery Regiment, 1st Belorussian Front

Born 1919, city of Korosten, Zhytomyr Oblast, Ukraine

Gimelfarb / Gimelford, Nikolay Naumovich – Guards Sergeant Major [Гимельфарб / Гимельфорд, Николай Наумович – Гвардии Старшина]

Cannon Commander – Self-Propelled Gun [Командир Орудия – Самоходной Установки] – ISU-122 [ИСУ-122]

367th Guards Self-Propelled Artillery Regiment, 31st Tank Corps

Born 1925; city of Moscow

Greys, Grigoriy Danilovich – Guards Junior Lieutenant [Грейс, Григорий Данилович – Гвардии Младший Лейтенант]

54th Guards Tank Brigade

Tank Commander [Командир Танка]

Born 1911; Kushchenskiy Raion, Rostov Oblast

Memorial Book of Jewish Soldiers Who Died in Battles Against Nazism – 1941-1945 – Volume VIII – 206

Perelman, Lev Solomonovich – Private [Перельман, Лев Соломонович – Красноармеец]

Machine-Gunner [Автоматчик]

240th Rifle Division

Born 1923; city of Nezhin

Memorial Book of Jewish Soldiers Who Died in Battles Against Nazism – 1941-1945 – Volume VIII – 401

Sunik, Abram Shaevich – Junior Lieutenant [Суник, Абрам Шаевич – Младший Лейтенант]

175th Tank Brigade

Tank Commander [Командир Танка]

Born 1921; city of Tashkent

Memorial Book of Jewish Soldiers Who Died in Battles Against Nazism – 1941-1945 – Volume III – pp. 395, 423

Tsimkin / Tsinkin Aleksandr Yakovlevich, Guards Sergeant [Цимкин / Цинкин, Александр Яковлевич – Гвардии Сержант]

Gun Charger (Заряжающий)

51st Guards Tank Brigade

At Ette, Germany

Born 1910; city of Mari, Turkmen SSR

England

“FROST, WITH A GESTURE STAYS THE WAVES THAT DANCE.”

Warrant Officer II Class John Gamble was one of the 37 members of the Jewish Brigade who were killed during the time in which the unit was engaged in combat with German forces. Biographical information, his portrait, and his story as presented in Jacob Lifshitz’s The Book of the Jewish Brigade: The History of the Jewish Brigade Fighting and Rescuing [in] the Diaspora – the latter transcribed as Hebrew, with English translation – are presented below…

Gamble, John Allan, WO 2C, 938393, Battery Sergeant-Major

England, Royal Artillery

200th Field Regiment, Palestine Regiment, Jewish Brigade Group

Mrs. Joan Gamble (wife), Kingsbury, Middlesex, England

Mr. and Mrs. Graham and Caroline Susan Gamble (parents)

Born 1918

Forli War Cemetery, Vecchiazzano, Forli, Italy – VI,C,23

We Will Remember Them – A Record of the Jews Who Died in the Armed Forces of the Crown 1939 – 1945, Volume I – 244

The Book of the Jewish Brigade – 249

סרגינט מיגיור גאמבל ג’ון אלאן ז”ל.

סרגינט מיגיור גאמבל ג’ון אלאן ז”ל.

Sergeant Major John Allan Gamble of blessed memory.

נפצע ומת מפצעיו ביום 17 באפריל 1945 בתאונת-דרכים באיטליה.

He was injured in a car accident in Italy on April 17, 1945 and died of his injuries.

סוללת התותחנים שלו נסעה לחזית ,וג’ון ,שרכב על אופנוע ,שימש כמפקח-התנועה. מכוניות השיירה העלו גלי אבק גדולים לאורך הדרך ,שסינוורו את העינים והאופנוע שלו התנגש עם מכונית-משא גדולה והוא נפצע קשה בברכיו ובשוקיו ומת מפצעיו .נקבר בבית-הקברות הצבאי (Forli) בעיר פורלי.

His artillery battery drove to the front, and John, riding a motorcycle, served as traffic inspector. The convoy cars raised large waves of dust along the road, which dazzled his eyes and his motorcycle collided with a large truck and he was badly injured in his knees and calves and died of his wounds. He was buried in the military cemetery in the town of Forli.

בן כ”ז במותו .נוצרי יליד אנגליה .נתחנד בבית-ספר ברונט שבמאנספילד .ספורטאי נלהב ,ייצג את בית-ספרו בתחרויות קרירט וכדור רגל והיה חבר פעיל במשד כמה בקלוב חובבי הקריקמ בוודהאוז ;שחייו וצולל מובהק .עסק לפני התגייסותו בהנהלת-חשבונות .גשוי .התגייס לצבא עם פרוץ המלחמה וצורף לחיל התותחנים .עד שנת 1943 שימש כמדריך בשיעורי-תותחנות בדרום וולס ובאירלנד ,אחר כך נשלח לצפון-אפריקה ושירת במחנה השמיני .אתר עבר לאיטליה והצמיין באומץ-לב בפעולות בפיזה וזבה על בך באות-ההצטיינות “עלי אשל” ביום 24 באוגוסט 1944 .ושוב הצטיין באומץ-לב זוכה להיוכר בהודעה צבאית ביום 11 בינואר 1945 .כשהחי”ל נכנס לחזית ,צורף אלאן לחיל התותחנים שבחי”ל.

He was 27 years old at the time of his death. A Christian born in England. He became an enthusiastic athlete at the Brunt School in Mansfield. He joined the army when the war broke out and joined the artillery. Until 1943 he served as an artillery instructor in South Wales and Ireland, then was sent to North Africa and served in the camp “Ali Eshel” on August 24, 1944. And again he excelled in courage. He was recognized in a military announcement on January 11, 1945.

This phot of Warrant Officer II Class’ Gamble’s matzeva is by FindAGrave researcher bbmir (no longer active), who apparently took images of many tombstones at the Forli War Cemetery.

____________________

____________________

Gordon, Stanley Edward, Lt., 331196

Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment)

Mr. A. Gordon (father), “Aloha”, King__on (?) Lane, Southwick, England

(also) 86 Great Tischfield St., London, England

Becklingen War Cemetery, Borkel, Kreis Becklingen, Germany – 3,B,16

Jewish Chronicle 5/18/45

We Will Remember Them – A Record of the Jews Who Died in the Armed Forces of the Crown 1939 – 1945, Volume I – 96

____________________

“GRIEVOUSLY MOURNED BY LOVING PARENTS, SISTERS, BROTHERS AND RELATIVES.”

Rosen, Michael, Lance Bombardier, 1544792

Royal Artillery, 71st Anti-Tank Regiment

Mr. and Mrs. Morris and Leah Rosen (parents), Sheffield, England

Born 1920

Hanover War Cemetery, Germany – 7,F,12

We Will Remember Them – A Record of the Jews Who Died in the Armed Forces of the Crown 1939 – 1945, Volume I – 148

This image of Lance Bombardier Rosen’s matzeva is by FindAGrave researcher pfo. Akin to the photo of Warrant Officer II Class Gamble’s tombstone, this image reveals the powerfully simple standardized design of tombstones in Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries, where commemorative inscriptions always appear below the religious symbol engraved in the stone’s center.

France

Bouaziz, Isaac, at Meknes, Morocco

France (Maroc), Armée de Terre, 16eme GA FTA Alger

From Fez, Morocco

Born 10/21/21

Died of illness (Maladie)

Golberg, Salomon, at Baden-Baden, Germany

France, Armée de Terre, 19eme Bataillon de Chasseurs à Pied

From Paris, France

Born 2/16/24

Died of wounds (Des suites des Blessures)

Perez, Moise, at Kehl [sic], Germany

France (Maroc), 101eme Genie

Born Marrakech, Morocco, 1919

Killed in combat (Tue au combat)

Poland

(Operation Bautzen-Elba, and, Operation Brand-Berlin)

Fajfer, Leon, Pvt. (Germany, Brandenburg, Karlshof (Operation Brand-Berlin))

Polish People’s Army, 7th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Daniel Fajfer (father)

Born 1919

JMCPAWW2 I – 19

Frenkiel, Maksymilian, Pvt. (Germany, Altreetz (Operation Brand Berlin))

Poland, Polish People’s Army, 5th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Baruch Frenkiel (father)

Born Kuchary, Poland, 1918

JMCPAWW2 I – 22

Gondowicz, Henryk, Pvt. (Operation Pomeranian Wall)

Polish People’s Army

JMCPAWW2 I – 25

Grynblat, Jakub, Sergeant Major (Germany, Altreetz (Operation Brand Berlin))

Polish People’s Army, 5th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Chaim Grynblat (father)

Born Warsaw, Mazowieckie, Poland; 1917

JMCPAWW2 I – 26

Klugman, Oskar, Pvt. (Poland-Germany, Oder River (Operation Brand Berlin))

Polish People’s Army, 2nd Light Artillery Regiment

Mr. Henryk Klugman (father)

Born Warsaw, Mazowieckie, Poland; 1917

JMCPAWW2 I – 37

Kniazanski, Maks, First Sergeant (Germany, Altwriezen (Operation Brand Berlin))

Polish People’s Army

Born 1925

JMCPAWW2 I – 37

Lampert, Leon, Lance Corporal, 27094 (Rhede, Germany; Canadian Hospital No. 6 at Ootmarsum, Netherlands)

1 Polska Dywizja Pancerna, 10 Pulk Dragonow

Poland, Polish Army West

Born Czernin d. Pieszew, Poland; 2/4/19

Jonkerbos War Cemetery, Gelderland, Netherlands – Plot V, Row A, Grave 3; Initially buried in Cemetery “Kuiperberg”, Ootmarsum, Netherlands

JMCPAWW2 II – 118

Landau, Antoni, Pvt. (Germany, Brandenburg, Neurüdnitz (Operation Brand Berlin))

Polish People’s Army, 6th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Natan Landau (father)

Born Tyczyn, Podkarpackie, Poland, 1905

JMCPAWW2 I – 43

Majner, Tadeusz, Cpl. (Germany, Brandenburg, Bad Freienwalde (Operation Brand Berlin))

Polish People’s Army, 4th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Leon Majner (father)

Born Warsaw, Mazowieckie, Poland; 1912

JMCPAWW2 I – 47

Nadryczny, Beniamin, Pvt. (Germany, Brandenburg, Bad Freienwalde (Operation Brand Berlin))

Poland, Polish People’s Army, 4th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Shlomo Nadryczny (father)

Born Tulicze (d. Kobryn), Poland, 1920

JMCPAWW2 I – 51

Panas, Wladyslaw, Pvt. (German-Polish border, Niesse (Operation Bautzen Elba))

Polish People’s Army, 37th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Daniel Panas (father)

Born 1908

JMCPAWW2 I – 53

Perelberg, Izaak, Cpl. (Germany, Brandenburg, Bad Freienwalde (Operation Brand Berlin))

Poland, Polish People’s Army, 1st Howitzer Regiment

Mr. Ben-Zion Perelberg (father)

Gorn Hrubieszow, Lubelskie, Poland; 1922

JMCPAWW2 I – 53

Rajchel, Jozef, Cpl. (Germany, Brandenburg, Neuwustrow (Operation Brand Berlin))

Lithuania, Polish People’s Army, 5th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Izrael Rajchel (father)

Born Braslaw (d. Vilna), Lithuania; 1915

JMCPAWW2 I – 56

Roza, Izrael, WO (Germany, Konigsreetz (Operation Brand Berlin))

Poland, Polish People’s Army, 4th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Icek Roza (father)

Born Lochow (d. Wegrow) [Mazowieckie?], Poland, 1916

JMCPAWW2 I – 59

Rozenbaum, Chaim, Pvt. (Germany, Saxony, Lodenau (Operation Bautzen Elba))

Polish People’s Army, 33rd Infantry Regiment

Mr. Izrael Rozenbaum (father)

Born 1924

JMCPAWW2 I – 58

Szafran, Chil, Pvt. (Germany, Saxony, Lodenau (Operation Bautzen Elba))

Polish People’s Army, 33rd Infantry Regiment

Mr. Mojzesz Szafran (father)

Born 1903

JMCPAWW2 I – 65

Szwarc, Roman, Cpl. (Germany, Klemzow (Operation Brand Berlin))

Poland, Polish People’s Army, 13th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Jozef Szwarc (father)

Born Wygnanka (d. Lublin), Poland, 1916

JMCPAWW2 I – 69

Trostenman, Zelik, Pvt. (Germany, Altreetz (Operation Brand Berlin))

Poland, Polish People’s Army, 5th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Lejb Trostenman (father)

Born Wolomin, Mazowieckie, Poland, 1908

JMCPAWW2 I – 71

Prisoners of War

United States Army

Glassoff, Isadore, Pvt., 31028697, Field Artillery, Purple Heart

6th Armored Division, 212th Field Artillery Battalion, Service Battery

Born in Massachusetts, 9/14/14; Died 2/21/78

Prisoner of War; POW camp (if any…) unknown

Mr. and Mrs. Hyman and Ida Glassoff (parents), Joseph (brother), 143 Cottage St., Everett, Ma.

Casualty List (Liberated POW) 6/21/45

American Jews in World War II – 160

____________________

United States Army Air Force

8th Air Force

78th Fighter Group

82nd Fighter Squadron

While a number of my prior posts have either focused on, profiled, or mentioned in passing Jewish aviators who served as fighter pilots in the WW I United States Army Air Service (like Jacques M. Swaab), United States Army Air Force, United States Navy, United States Marine Corps, and Royal Air Force, the 17th of April in 1945 was somewhat unusual in this respect. That day, two Jewish fighter pilots – assigned to the same Air Force – the England-based 8th Air Force; members of the same Fighter Group – the 78th; members of the same Fighter Squadron – the 82nd; flying the same type of aircraft – the P-51D Mustang; were lost during a bomber escort and strafing mission to the Dresden area. The Parallels continue. Both were immediately captured (one was injured) and both survived the war’s closing weeks (well, the war obviously continued in the Pacific Theater!) to eventually return to the United States.

On another, more abstract level, documentation about these two pilots has its own curious parallel: The Missing Air Crew Reports (MACRs) covering their loss in combat were filed sequentially, and their portraits can be found in the same official Army Air Force Photograph, image 72440AC (A12409).

Who were they? Second Lieutenant Alvin Mordecai Rosenberg (MACR 13940) and First Lieutenant Allen Abraham Rosenblum (MACR 13939).

____________________

Lt. Rosenberg, 0-830084, parachuted from his P-51D 44-72357 (the probably un-nicknamed MX * D) at a point southwest of Adorf and north-northeast of Selb, Germany, due to an engine fire (and possible coolant leak) of unknown origin. Though nothing is known about his experiences as a POW, he would eventually return to his home state of New York. Born on January 6, 1924, he was the son of Raphael and Estelle, the family living at 2261 64th Street, in Brooklyn. He received the Air Medal, three Oak Leaf Clusters, and Purple Heart, though it’s not known if the latter award was specifically granted for the April 17 mission. His name appeared in the Brooklyn Eagle on July 25, 1941 (yes, 1941, not 1944), and in a War Department Casualty List of May 18, 1945. And, his name also appears on page 416 of American Jews in World War II.

Here’s a very high resolution scan of his portrait, from Army Air Force Photo 72440AC (A12409)…

…and, here’s a transcript of the Missing Aircrew Report pertaining to his loss:

S T A T E M E N T

I was flying Surtax Yellow leader when Surtax leader went down on an airdrome to destroy a jet that had just landed. My wingman couldn’t get his left combat tank off, so I didn’t take my flight down. Surtax spare, Lt. Rosenberg, was flying #5 in Yellow flight. He called that something had popped out the right side of his cowling. He had not been hit by flak. I told him to open his coolant and oil shutters wide, which he did, and to pick up a heading of 270 degrees, which he failed to do. He kept steering about 180 degrees and called in about 3 minutes later that he had returned his shutters to automatic because the plane seemed to be OK. I told him again to steer about 280 or 290 degrees, which he did, and told him to open his shutters again, which he did. By this time, I was flying fairly close formation with him, so I could observe the right side of his plane. A thin steady stream of white smoke was coming out of the exhaust stacks, which became increasingly worse after about 4 or 5 minutes. He said it was going to quit and wanted to know if we were in friendly territory. I told him to prime like mad, and the smoke stopped temporarily. I told him to try to keep it going for at least 7 minutes, because we were still in enemy territory. Every time the smoke started, I would yell at him to prime, and the smoke would stop. About 3 minutes from the time it got bad, however, the engine quit altogether and flames emanated from around the exhaust stacks. He immediately released the canopy and bailed successfully. The plane crashed and exploded, and he landed about 100 yards from a house. Two people came out to him, and he seemed to be OK, for he stood and waved to us. Lt. Childs, my element leader, buzzed them a couple of times, so his description of the people with Lt. Rosenberg follows. Lt. Rosenberg’s exact position is not known, but his approximate position is in the vicinity of Adorf, just south of Plauen.

IVAN H. KEATLEY 0-665815

Captain, Air Corps.

I was flying Surtax Yellow 3. After Lt. Rosenberg bailed out, I saw him land safely in an open field and saw him met by two German men. One appeared to have on an olive drab uniform, the other was wearing civilian clothes. As I passed over, he waved that he was OK. The second time I passed over he was standing in a small village, which I believe was Adorf.

JOHN C. CHILDS 0-2005853

1st Lt., Air Corps

I certify I have interrogated every pilot in the vicinity of Adorf, where Lt. Rosenberg became MIA, and that all available information is incorporated in the statements above.

ERWIN C. BOETTCHER

Captain, Air Corps

Intelligence Officer

Here’s by the map accompanying the MACR. Not too precise, but it does the job.

I’ve been unable to trace information about Lt. Rosenberg further.

____________________

The day was rather more eventful for Lieutenant Rosenblum. During a strafing attack against the Kralupy Airdrome, north-northwest of Prague and just east of the Vltava River, where his formation position was that of “Surtax Red Leader”, his left drop tank (which he couldn’t jettison) and propeller struck the ground, even as his Mustang (P-51D 44-72367, the probably un-nicknamed “MX * C”) became the focus of German antiaircraft fire. After a brief farewell radio message, he attempted to belly-land his plane, but the aircraft tumbled, and – as anti-aircraft fire continued – it cartwheeled, tearing off the right wing. Though no sign of life was seen by an observing pilot (Lt. Klassen) once the hurtling Mustang stopped moving, Lt. Rosenblum emerged from the wreck quite alive, his only injury a broken arm. As revealed in an Atlanta Constitution article of October 30, 1945 (see below), he was interned at Stalag 18C, in Markt Pongau, Austria, and like Lt. Rosenberg, in time returned to the United States.

Serial number 0-678943, he completed 56 missions, and received the Air Medal and two Oak Leaf Clusters, at least based on information in American Jews in World War II, where his name appears on page 89. Given his injury and total number of missions flown, it seems that he should have received the Purple Heart and eleven Oak Leaf Clusters…

Lt. Rosenblum’s parents were Nathan (Nuchum) Beryl and Freda (Bain) Rosenblum, of 127 Peachtree Street, in Anderson, South Carolina, while his sister Sarah was married to Sergeant David D. Danneman (himself a POW, as described below), from 771 Washington Street, in Atlanta. Born in Orangeburg, South Carolina, on April 26, 1923, he passed away on October 12, 1986, and is buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Cemetery, in Lilburn, Georgia. Along with American Jews in World War II, his name appeared in an official Casualty List on May 17, 1945, the Southern Israelite on November 2, 1945, and the Atlanta Constitution on March 9, 1945. This latter article follows below…

Lt. Allen Rosenblum In Air Convoy to Berlin

Lt. Allen A. Rosenblum, whose sister, Mrs. David Danneman, lives at 771 Washington Street, S.W., was one of 900 fighter pilots convoying 1,000 Eighth Air Force Fortresses in a recent devastating attack on the heart of Berlin.

Flying a P-51 Mustang, Lt. Rosenblum was in the air more than five and a half hours on the Berlin mission. His group, which went down to strafe an airfield at Luneburg and trains in other parts of western Germany, left 15 Nazi planes burning on the field and damaged 11 others, in addition to several locomotives and oil cars which were destroyed.

____________________

Here’s a very high resolution scan of Lt. Rosenblum’s portrait, from Army Air Force Photo 72440AC (A12409)…

…and, here’s a transcript of the Missing Aircrew Report pertaining to his loss:

STATEMENTS OF EYE–WITNESSES

We were flying in Surtax Red flight, led by Lt. Rosenblum, on a bomber escort to Dresden. After the target, we flew south into Czechoslovakia and hit the deck to strafe an airdrome north of Prague. Surtax Red leader tried to drop his tanks, but his left one would not come off. One the run toward the field, while on the deck, Lt. Schneider called him, but he never did get it off. As we neared the field, on the deck, flak began to come at us. I saw it was being concentrated on Red leader. We were line abreast and I saw Rosenblum’s prop and tank hit the ground before reaching the field as he was hugging the ground to get under the flak. We believe he also hit his prop again on the field. He then said, “I’ve got to belly in here, so long fellows.” We passed him just as he was bellying in and did not get another look at the aircraft.

EDWIN O. SCHNEIDER 0-713584

1st Lt., Air Corps.

HARRY L. ROE JR 0-830318

2nd Lt., Air Corps.

__________

I was Cargo (83rd Fighter Squadron) Yellow leader on bomber escort In the Dresden area when Nuthouse reported jets in the area. I took my Section south of target to investigate some Bogies which turned out to be Surtax White and Red flights. They were positioning themselves to strafe an airdrome, so I circled to observe results. As Surtax Red Flight went over the drome, I saw one aircraft lagging behind and going very slow, and at that time Surtax Red leader called and said, “I’ve got to belly in here, so long fellows.” He cleared the west edge of the airfield, but hit something with his left wing just as he bellied in, which spun the aircraft around and tore off his right wing as he cart-wheeled. From the time he reached the edge of the field until after the aircraft came to a stop, I observed hits on and all around his aircraft from small caliber arms. The aircraft did not burn, and no one got out as I circled.

PETER W. KLASSEN 0-708695

1st Lt., Air Corps

I certify that I have interrogated every pilot in the area of Kralupy Airdrome at the time Lt. Rosenblum became MIA. All available information is Incorporated in the statements of the above.

ERRIN C. BOETTCHER

Captain, Air Corps

Intelligence Officer.

Here’s by the map accompanying the MACR. Like that for Lt. Rosenberg, not too detailed, but close enough, considering the conditions (combat conditions, that is!) under which observations were made.

Given the nearly eight decades that have transpired since the events in question, I thought it would be interesting to identify the actual location and current appearance of the Krapuly Airfield. This was not difficult, for the website Vrtulníky v Česku (Helicopters in the Czech Republic) has substantial information (at “Kralupy nad Vltavou Kralup“) chronologically arranged, about the airfield’s history from 1913 through 1955, of course in Czech. This includes the statement;

“16.4.1945 nálet stíhačů od 78th FG a 339th FG, 8th USAAF z Velké Británie.

Jako první byly zničeny čtyři stroje He 177. Pozoroval jsem vzdušný kolotoč z výšiny nad Minicemi, nad kterými dokončovaly některé stroje otáčky a vracely se zpět ke kralupskému letišti. V krátké době zůstaly z pýchy německého letectva na zemi jen hořící trosky. Po osmi průletech spojeneckých stíhačů byl celý prostor letiště zničen. Proti útočícím Mustangům nezasáhli Němci ani ze země, ani ze vzduchu. Zdroj.

Přímý účastník útoku na kralupské letiště Leutenant J.W. Gokey od 503rd FS, 339th FG, 8th USAAF z Velké Británie vzpomíná: “V oblasti, kam jsem směřoval, jsem spatřil několik letadel 78th FG, útočících na letiště u Kralup. Zapojili jsme se také krátce do boje. Plocha byla špatně přístupná a již na ni hořelo 30 nebo 35 transportních Ju 52. Zaměřili jsme se na vybavení letiště a zničili několik baráků na severu hlavní dráhy. Pro nedostatek paliva jsme prostor brzy opustili. Ze země nešla žádná palba, ale viděl jsem dva palposty flaku, které pravděpodobně zničila již 78th FG ..”

Approximate translation?

On April 16, 1945 raid [by] fighters from the 78th FG and 339th FG, 8th USAAF from Great Britain.

The He 177 aircraft were the first to be destroyed. In a short time, out of the pride of the German Air Force, only burning debris remained on the ground. After eight flights by Allied fighters, the entire area of the airport was destroyed. The Germans did not intervene against the attacking Mustangs either from the ground or from the air.

A direct participant in the attack on Kralupy Airport, Lieutenant J.W. Gokey from the 503rd FS, 339th FG, 8th USAAF from Great Britain recalls: “In the area where I was heading, I saw several 78th FG aircraft attacking the airport near Kralupy. We also participated briefly. The area was difficult to access and 30 or 35 Ju-52 transports [had] already burned. We focused on airport equipment and destroyed several barracks in the north of the main runway. Two flak outposts were probably destroyed by the 78th FG.”

Interestingly, given that Kralupy nad Vltavou Kralup has no information about an attack against the Kralupy Airfield on April 17 – and I don’t think the 78th Fighter Group would have conducted a strafing attack against the same distant enemy airfield on two consecutive days – I wonder if the above statement about a mission on April 16, actually refers to the 78th’s mission of April 17. (I think it may!) In any event, here are three images of an April strafing attack against the Kralupy airfield from the same web page. (The source of the photos is not listed.)

In the image below, a P-51 is visible banking to the left, in the upper right corner.

But, what about the airfield’s specific location? Kralupy nad Vltavou Kralup displays air photos of the area, taken in 1946 and 1953, which show the field in relation to nearby geographic features, as well as the wreckage of Luftwaffe aircraft (I think Siebel 204s) that after the war were dumped in nearby quarries, or, pushed into wooded areas bordering the field. This photo, taken in 1953, shows the locations of four of these aeronautical junk piles – denoted by red ovals – at the periphery of the field.

But, what about the airfield’s specific location? Kralupy nad Vltavou Kralup displays air photos of the area, taken in 1946 and 1953, which show the field in relation to nearby geographic features, as well as the wreckage of Luftwaffe aircraft (I think Siebel 204s) that after the war were dumped in nearby quarries, or, pushed into wooded areas bordering the field. This photo, taken in 1953, shows the locations of four of these aeronautical junk piles – denoted by red ovals – at the periphery of the field.

Using this information and these photos in conjunction with the map in MACR 13939, I’ve created the following series of Oogle maps which – as you move “down” this page – reveal, at successively larger scales and therefore in greater detail, contemporary views of the airfield’s location. In each case, the airfield site is denoted by a red circle.

First, the airfield in relation to the city of Prague: A teeny-tiny red circle on this small-scale map.

Oogling on in, the airfield in relation to Veltrusy, and, Karlupy nad Vltavou (“Kralupy on the Vltava River”).

Oogling even closer…

Here’s a 2021 Landsat view of the area above. You can see that much of the terrain once occupied by the airfield is now taken up by buildings.

A map view again, but closer…

…followed by another Landsat image at the same scale as above. Note that probably more than half of the area once occupied by the airfield is now taken up by industrial development.

Finally, in this 3-D Oogle image of the airfield site (looking west-northwest) the extent of postwar construction is very clear. Also noticeable at the lower center right is one of the forested areas that existed back in 1945. Perhaps some aircraft wrecks – even including the remnants of P-51D 44-72367? – still lie there, deeply buried, awaiting discovery?

____________________

But, what of the two lost Mustangs? The fate of the P-51s is clearly described in the MACRs: Lieutenant Rosenberg’s plane crashed and exploded not far from where he landed by parachute, while Lieutenant Rosenblum’s aircraft broke apart when he crash-landed on the airfield. Given the time-frame of the planes’ losses, there are no Luftgaukommando Reports pertaining to them. End of that story.

As for the markings of the two aircraft, information comes from Garry Fry’s Eagles of Duxford, which lists the squadron codes assigned to the planes as MX * C for Lt. Rosenblum’s, and MX * D for Lt. Rosenberg’s. Though Eagles does not indicate if the planes carried nicknames or nose art, this possibility is not entirely precluded, for – given the fact that the pertinent MACRs don’t even record the P-51’s squadron codes in the first place! – if the planes had been nicknamed, this information may simply have never been preserved.

Regardless, the following two images, from Peter Randall’s Little Friends website, give a very good representation of the presumable appearance of the two fighters: Natural metal finish, red rudders, “swept” black and white checkerboard nose trimmed in red surrounding the front half of the aircraft’s nose, and squadron codes painted in black (or, insignia blue?) trimmed with red.

First, P-51D 44-63246: This particular image was, “Taken in Duxford, England by Maj. Atlee G. (Pappy) Manthos while operations officer with the 78th Fighter Group following the end of hostilities in Europe. The pilot of this 82nd FS P-51D was Lt. John C. Childs of Hot Springs, Arkansas.”

Second, P-51D 44-15745: “Lt. Walter E Bourque. Detroit, Mi. 82nd Fighter Squadron. P-51D 44-15745 MX-T.” This photo also appears as image UPL26433 via the American Air Museum in England.

__________

But then, there’s this… Lt. Rosenblum, seated in the cockpit of unidentified P-51D Rosey THE Riveter. Unfortunately (!), specific identification of this plane is impossible, since the plane’s individual aircraft code letter – painted on the aft fuselage – does not appear in the image. Otherwise, the shade of the Rosey THE Riveter logo and MX squadron code letters – both dark, with lighter outline – appear to be identical. Interestingly, rather than a K-14 gyroscopic gunsight, the plane is equipped with a (N-9?) reflector gunsight.

Unfortunately, the source of this image – the very title of the book in which I discovered it – escapes me for the moment (!), but I think the picture appeared in a book about the history of the Jews in the South. In any event, the image is credited to Raymond and Sandra Lee Rosenblum. [Update 8/14/21: The image is from the 2002 book A Portion of the People – Three Hundred Years of Southern Jewish Life, and is from the collection of Raymond and Sandra Lee Rosenblum.]

__________

But, there’s more, and even earlier, to Lt. Rosenblum’s story. April 17, 1945 was not the only day on which he did not – immediately – return to his base.

On September 18, 1944, he bellied in east of Brussels in P-47D 43-25300 (“MX * I”, nickname: “B Hope”). As described by Garry Fry in a letter to Rudy Kenis of De Panne, Belgium, of October 31, 1986,

Dear Rudy,

This P-47 43-25300 was successfully belly-landed on Sept. 18, 44… The pilot was 1 Lt. Allen A. Rosenblum, 82 F.S., who was not hurt and he returned to England and resumed his duties. The reason for the crash is that he ran out of gasoline on the way home.

Photographs of the wreck of MX * I can be viewed here, while a summary of the day’s events, from the 82nd Fighter Squadron History, follows:

2 October 1944

September 18. 17 Planes on fighter bomber mission of Flak positions in Holland. In Rotterdam 1530 hrs. Out Amsterdam 1709 hrs. Take off 1435 hrs. Down at 1740 hrs. Bombing poor to good results on flak positions and barges. 30 Plus trucks in convoy strafed on highway between Brest and Vianen, 18 destroyed and 11 damaged. Heavy accurate light and heavy flak from Rotterdam and flak barges west of the city. 2 Cat. AC and 1 Cat. A flak damage. Lt. R.C. Snyder MIA, hit by flak and bellied in SW of Rotterdam and heard to say he was O.K. after landing. [P-47D 42-75551, MX * M, MACR 9001] Pilots were Capt. May, Lts. Lamb, Bolgert, Coss, Shope, Rosenblum, Mattern, Nelson, Brown, Snyder, Boeckman, Croy, Sharp, Miller, Bosworth, Eggleston, and Keatley.

Finally and perhaps most importantly, some comments about Allen A. Rosenblum as a “person”, from letters to Rudy Kenis in late 2012 by Allen’s son Michael.

28 October 2012

Hi, Rudy – I have a picture of my dad in a plane with the MX * I marking, but not certain that was his plane. I also have a photo of dad in a plane marked “Rosey the Riveter”. He was shot down twice, but I only have information on his second crash in Poland (see attached). It is possible that his first crash was in Belgium – he was able to make it back to Allied lines safely. After his second crash, he was a POW until the end of the war (2-3 weeks) – fortunate. Please let me know if you find out anything about the Belgium crash. Dad never spoke much about his war efforts – doing so gave him nightmares for weeks afterwards. I recently learned some of these details through contacts on the P-47 pilot website.

Many thanks

__________

4 November 2012

Hi, Rudy – Many thanks for the email. I think Dad’s earlier crash because of low fuel matches what I know of his war efforts. Here is a picture of Dad in his Rosey the Riveter (MX) aircraft. [See above.] Hope this helps.

……….

Forgot to mention that you words about my father are very kind. He would have been very pleased to have heard them. Dad almost never spoke about his time in the war. Doing so would cause him to have nightmares for weeks afterward. We would have called it PTSD. It is amazing to me to find that there are efforts of others honoring efforts of pilots like Dad. Many thanks.

____________________

Lieutenant Rosenblum’s brother-in-law, Sergeant David Daniel Danneman (34261537) served as a togglier in the 547th Bomb Squadron of the 384th Bomb Group. His plane, B-17F 42-29870 (JD * U, otherwise known as BIG MOOSE) piloted by 1 Lt. Giles F. Kauffman, was shot down on October 14, 1943. Its loss is covered in MACR 1038 and Luftgaukommando Report KU 296 (which, being a very early “low numbered” Luftgaukommando Report, is missing from NARA Records Group 242), the entire crew of ten surviving.

Born on August 1, 1918 in Anderson County, South Carolina, he was the son of Aaron and Jenny (Jacobovitz) Danneman. His wife Sarah resided at 771 Washington Street in Atlanta, Georgia.

David Danneman passed away at the young age of 49 on December 25, 1967. His name appeared in a Casualty List released on June 15, 1945, and on page 87 of American Jews in World War II, where he is recorded as having received the Purple Heart. His commemorative page at the National World War II Memorial can be found here.

As mentioned above, on October 30, 1945, The Atlanta Constitution published a lengthy article (by Katherine Barnwell) about the experiences of Lt. Rosenblum and Sergeant Danneman, in the context of a postwar reunion of the two men. Like many newspaper articles of the era, the account, which includes an excellent photo of the brothers-in-law and Sergeant Danneman’s wife Sarah, is particularly valuable in presenting information unavailable in military records. A transcript follows:

Brothers-in-Law Meet Here; Held as POW 50 Miles Apart

STORY-BOOK-ENDING

It was a joyous reunion at 771 Washington street yesterday for two Atlanta brothers-in-law who met here for the first time in many months after being prisoners of war – 50 miles apart – in Germany.

It was a joyous reunion at 771 Washington street yesterday for two Atlanta brothers-in-law who met here for the first time in many months after being prisoners of war – 50 miles apart – in Germany.

It was an equally happy occasion for Mrs. Sarah Danneman, who was present at the meeting between her brother, Lt. Allen A. Rosenblum, and her husband, S/Sgt, David D. Danneman. Both men served in the Eighth Air Force in England, and both were shot down in missions over Nazi territory.

It was, in fact, a story-book ending for all concerned, as the smiles which all three wore yesterday amply proved. Danneman received his discharge about a week ago, and Rosenblum expects to become a civilian again around the first of December.

Danneman spent the longer period in a German prison – 19 months, though “it seemed much longer.” He was sent overseas in April, 1942, and received his training at an RAF school in Kirkham, England.

NOSE GUNNER ON “FORT”

A nose gunner on a Flying Fortress, he was shot down on his third mission, over Schweinfurt, Germany, Oct. 14, 1943. His plane was hit by antiaircraft flak, and he parachuted 28,000 feet to safety.

“That mission,” Danneman explained proudly, “caused the war to end six months earlier than it would have otherwise. Although we lost 60 bombers, we destroyed the largest ball bearing factory in Germany.”

Danneman was taken to Krems, Austria, where he was imprisoned at Stalag 17B. He remained there until April of this year when all prisoners there were forced marched to Braunau, Austria, Hitler’s birthplace. He was liberated by the Third Army last May 2.

Like other American prisoners in Germany, he received little food except “wormy soup, a few potatoes, and some black bread.” He himself received only one beating from guards, but he witnessed the torture of hundreds of Jewish prisoners who were “more dead than alive.”

HOMEMADE RADIOS

“We had hundreds of ‘bugs’ (homemade radios) in the camp,” Danneman said. “We would swap cigarettes sent us by the Red Cross to French workers for radio parts, so that we could keep up with the progress of the war.”

But Danneman did not know that his wife’s husband, Lt. Allen Rosenblum was overseas, much less that he was a prisoner only 50 miles away later in the war.

Rosenblum went overseas in July, 1944, and completed 56 missions before being shot down. He was attached to the 78th Fighter Group of the Eight Air Force and he was credited with destroying four German planes and damaging two others.

It was in April 1945, when he was strafing an air field in the Sudetenland that his plane was hit by antiaircraft fire. He made a crash landing in a clump of trees, and suffered head wounds and a broken arm.

Taken prisoner immediately, he was sent to Stalag 18-C in Austria. Although he was in prison only about three weeks before he was liberated, he lost 30 pounds during that time.

“BETTER OFF THAN MOST”

“But I was better off than most,” he admitted. “I saw guys by the road so hungry that they were eating leaves from the trees – and grass too.”

Meanwhile, Mrs. Danneman here in Atlanta did mot merely wait idly for the return of her husband and brother. Besides holding down a full-time job, she worked three nights a week as a nurse’s aid, and most other nights as a USO hostess. She amassed more than 2,000 hours in USO work.

Both Danneman and Rosenblum were much-decorated for their Army service. Rosenblum wears the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal, wight eight oak leaf clusters, the Purple Heart, Good Conduct medal, and the presidential unit citation. Danneman received the Purple Heart last Friday, and the Air Medal and Good Conduct medal are on the way.

“Good conduct was sort of forced on me,” Danneman laughed, “since German guards were watching me for nearly two years.”

Wounded in Action

United States Army (Ground Forces)

Abramson, Harry, Pvt., 33939323, Purple Heart (Italy, Bologna)

Born 1919

Mrs. Eva Abramson (mother), 707 S. 4th St., Philadelphia, Pa.

The Jewish Exponent 5/18/45

Philadelphia Record 5/10/45

American Jews in World War II – 508

Cooper, Sidney, Sgt., 13077767, Purple Heart (at Ie Shima, Okinawa)

Born Philadelphia, Pa., 1/31/20

Mrs. Anne Cooper (wife); Gail Eileen and Marsha Sharon (daughters), 2500 N. Marston St. / 523 Snyder Ave., Philadelphia, Pa.

Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin and Florence Cooperman (parents), 2711 South 9th St., Philadelphia, Pa.

The Jewish Exponent 6/8/45

Philadelphia Inquirer and Philadelphia Record 5/29/45

American Jews in World War II – 516

Kaitz, Aaron A., Pvt., 33815875, Purple Heart (Germany)

Born 1926

Mr. and Mrs. Abraham H. and Anna C. Kaitz (parents), 1316 South Street, Philadelphia, Pa.

Jewish Exponent 5/18/45

Philadelphia Inquirer and Philadelphia Record 5/9/45

American Jews in World War II – 530

United States Marine Corps

Polotnick, Harry, Sgt., 810771, Purple Heart

6th Marine Division, 29th Marine Regiment, 3rd Battalion, G Company

Born 10/4/23; Died 3/27/91

Saint Louis, Mo. (next of kin unknown)

American Jews in World War II – 215

Other Incidents…

…United States Army Air Force

Rescued with fellow crew members after ditching in the Pacific…

Greenfogel, Maurice “Mo” (Moshe Bar Mordechay HaCohen), Sgt., 32874753, Passenger

5th Air Force, 2nd Emergency Rescue Squadron

No Missing Air Crew Report, Aircraft C-47B 43-47995, Pilot 1 Lt. Robert L. Rohlfing, 12 crew and passengers – all personnel survived; Rescued 4/18/45 at 2130 by Hospital Ship USS Maetsuycker

Born 10/23/24, Brooklyn, N.Y.; Died 6/4/17

Mr. and Mrs. Max and Gussie Greenfogel (parents), Albert and Evelyn (brother and sister), Brooklyn, N.Y.

American Jews in World War II – Not listed

The pilot of a B-17 Flying Fortress, who witnessed the loss of another B-17…

Rabinowitz, Eugene, 1 Lt., 0-831796 (Bomber Pilot)

8th Air Force, 305th Bomb Group, 366th Bomb Squadron

In MACR 14172, witness to loss of B-17G 43-38085 (“KY * L”, “Towering Titan”), pilot by 2 Lt. Brainerd E. Harris, 8 crew – no survivors

Probably from Brooklyn, N.Y.

Opelika-Auburn News – 9/15/20

American Jews in World War II – Not listed

Soviet Air Force

Military Air Forces – VVS (Военно-воздушные cилы России – ВВС)

Missing during combat mission on April 17 – 18, 1945. Actual fate unknown.

Shapiro, Mikhail Solomonovich – Junior Sergeant [Шапиро, Михаил Соломонович – Младший Сержант]

1st Guards Aviation Corps, 16th Guards Bombardment Aviation Regiment (By June of 1945, at Military Post 15539 “V”)

Aerial Gunner – Radio Operator [Воздушный Стрелок-Радист]

Aircraft: Probably… Il-4 [Ил-4]

Born 1926; city of Kiev

Mr. Galina Mikhaylovna (Moiseevna?) Shapiro (mother), Labzik Street, Uichi Building, Block 36, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

References

Dublin, Louis I., and Kohs, Samuel C., American Jews in World War II – The Story of 550,000 Fighters for Freedom, The Dial Press, New York, N.Y., 1947

Freeman, Roger A., The Mighty Eighth – A History of the U.S. 8th Army Air Force, Doubleday and Company, Inc., New York, N.Y., 1970

Freeman, Roger A., Camouflage & Markings – United States Army Air Force, 1937-1945 [“North American P-51 & F-6 Mustang U.S.A.A.F., E.T.O. & M.T.O., 1942-1945”], Ducimus Books Limited, London, England, 1974

Fry, Garry L., Eagles of Duxford: The 78th Fighter Group in World War II, Phalanx Publishers, St. Paul, Mn., 1992

Lifshitz, Jacob (יעקב, ליפשיץ), The Book of the Jewish Brigade: The History of the Jewish Brigade Fighting and Rescuing [in] the Diaspora (Sefer ha-Brigadah ha-Yehudit: ḳorot ha-ḥaṭivah ha-Yehudit ha-loḥemet ṿeha-matsilah et ha–golah ((גולהה קורות החטיבה היהודית הלוחמת והמצילה אתספר הבריגדה היהודית)), Shim’oni (שמעוני), Tel-Aviv, 1950

Maryanovskiy, M.F., Pivovarova, N.A., Sobol, I.S. (editors), Memorial Book of Jewish Soldiers Who Died in Battles Against Nazism – 1941-1945 – Volume I [Surnames beginning with А (A), Б (B), В (V), Г (G), Д (D), Е (E), Ж (Zh), З (Z), И (I)], Union of Jewish War Invalids and Veterans, Moscow, Russian Federation, 1994

Maryanovskiy, M.F., Pivovarova, N.A., Sobol, I.S. (editors), Memorial Book of Jewish Soldiers Who Died in Battles Against Nazism – 1941-1945 – Volume III [Surnames beginning with О (O), П (P), Р (R), С (S)], Union of Jewish War Invalids and Veterans, Moscow, Russian Federation, 1996

Maryanovskiy, M.F., Pivovarova, N.A., Sobol, I.S. (editors), Memorial Book of Jewish Soldiers Who Died in Battles Against Nazism – 1941-1945 – Volume VIII [Surnames beginning with all letters of the alphabet], Union of Jewish War Invalids and Veterans, Moscow, Russian Federation, 2005

Meirtchak, Benjamin, Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II: I – Jewish Soldiers and Officers of the Polish People’s Army Killed and Missing in Action 1943-1945 [“JMCPAWW2 I”], World Federation of Jewish Fighters Partisans and Camp Inmates: Association of Jewish War Veterans of the Polish Armies in Israel, Tel Aviv, Israel, 1994

Meirtchak, Benjamin, Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II: II – Jewish Military Casualties in September 1939 Campaign – Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armed Forces in Exile Soldiers and Officers of the Polish People’s Army Killed and Missing in Action 1943-1945 [“JMCPAWW2 II”], World Federation of Jewish Fighters Partisans and Camp Inmates: Association of Jewish War Veterans of the Polish Armies in Israel, Tel Aviv, Israel, 1995

Morris, Henry, Edited by Gerald Smith, We Will Remember Them – A Record of the Jews Who Died in the Armed Forces of the Crown 1939 – 1945, Volume I, Brassey’s, United Kingdom, London, 1989

Rosengarten, Theodore and Rosengarten, Dale, A Portion of the People – Three Hundred Years of Southern Jewish Life, University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, S.C., 2002

No Author

Duxford Diary, 1942-1945, W. Heffer & Sons (printer), Cambridge, England, 1945