“I hold my life as wholly sacrificed, but if fate should be kind enough to spare me, after the war I shall consider my life as no longer belonging to me, and, after having done my duty towards France, I shall devote myself to the great and unhappy Jewish people from whom I am descended.”

A perennial, central, and universal aspect of human nature has been the need for acceptance – and the validation of that acceptance – by one’s surrounding culture, society, and nation. The overlapping motivations for this range from the pragmatic and material, to even the spiritual – at least in so far as politics being a substitute for religion. The paradox with the need for validation – whether it be for an individual, or, for the “place” of a distinct group – is that typically, that very validation is accorded greater credence when it emanates from one who is unafillated with, and ultimately in opposition, to that very person or group.

A striking example of this was manifest as the cover article of The Jewish Exponent (of Philadelphia) in its issue of July 26, 1918, published only four months before the end of the Great War. Entitled “The Jews and The War,” the essay is an English-language translation of a chapter within Maurice Barrès’ 1917 book Les Diverses Families Spirituelles de la France (The Various Spiritual Families of France), entitled “les Israelites” (“The Israelites”).

As such (you can view the book’s table of contents by scrolling below…) that chapter was one of five (or six, depending on how you interpret the text!) of the book’s eleven chapters, which taken together focused upon the various groups within and comprising the nation of France, whose unity Barrès deemed essential to the survival of that nation at a time of existential crisis. Noteble is the fact that while two of these “families” – Catholics and Protestants – are defined by religious belief and doctrine; a fourth – the Socialists – can be termed political (with economics thrown in for the mix?); and the fifth – the Traditionalists – one might be deemed cultural.

Ultimately, Barrès title subsumes and equalizes all these groups within the larger whole of France, as, families. And, among these national families of France is the Jewish people, a family defined not only in terms of terms of the nature of its religous belief (or, disbelief, as the case may be), but simultaneously with a particular land, and ultimately, peoplehood – the Jewish people. In his discussion about the Jews of France, rather than engage in a lengthy religious, philosophical, or political exegesis, Barrès simply presents accounts about the enlistment, military service, and death in action of three French Jewish soldiers: Sous Lieutenant Amadee Rothstein, Sous Lieutenant Robert Walter Hertz, and Caporal Robert Cahen.

The examples of these three men – three, alas, of very many – seem to have been chosen based on their ancestry, the symbolism inherent to their stories, and finally, the sense of literary expression evident in their correspondence with friends, family, and even in literary or academic journals: Rothstein (from the fourth Arrondissement?), a proud Zionist, born in Cairo in 1891; Hertz, a student of the Normal College and professor of philosophy in the college of Douai, born in Saint Cloud in 1891, to a father of German Jewish ancestry; Cahen, a graduate of the Normal College and freethinker who wrote, “I do not believe in any dogma of any religion.” “I have just read the Bible. It is for me a collection of tales, of old and charming stories. I do not look for, nor do I find in it anything else but poetic emotions.” – None and nevertheless, a Jew.

Obviously – ! – Barrès penned his book in French, (I don’t know if an English-language translation exists, the 1917 edition being available at archive.org., while you can – I think! – more easily read the chapter in its original French text, transcribed here.) In that light, it’s interesting that the Exponent did not mention the name of the text’s translator. Could this person have been M. Marcel Knecht, mentioned in the article’s preface as a member of the French High Commission to the United States?

______________________________

You can read the full text of Barrès’ article / chapter – as presented in the Exponent – below, transcribed verbatim, below.

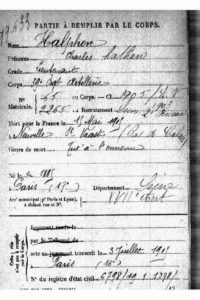

I’ve supplemented the text by including “PARTIE À REMPLIR PAR LE CORPS (‘PART TO BE COMPLETED BY THE CORPS’)” forms (for example, see my earlier post, Three Soldiers – Three Brothers? – Fallen for France: Hermann, Jules, and Max Boers) Cards for Rothstein, Hertz, and Cahen, listing biographical information about each soldier as derived from both the Cards and other sources, such as l’Univers Israélite (reviewed at the Dorot Jewish Division of the New York Public Library), and the 2000 reprint of Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française 1921. To enable you to distiniguish between my textual additions and the original article, more easily, this information is presented in maroon-colored text, like this.

To place the lives of these three men in greater perspective, at the “end” of this rather lengthy post, I’ve listed the names of French Jewish soldiers, and German Jewish soldiers, who lost their lives on the same dates as Rothstein, Hertz, and Cahen. The record for each of the French Jewish soldiers comprises that soldier’s 1) rank, 2) country or land of birth, and, 3) the geographic location where he was killed. All these names were obtained from the SGA’s Base des Morts pour la France de la Première Guerre mondiale (Database of Killed for France in the First World War) database. And, the record for each of the German Jewish soldiers comprises the soldier”s name, rank, military unit, and (where known) place of burial. Notably, of the eighty-eight French Jewish soldiers who were killed in action or died of wounds on May 9, 1916, the names of twenty-seven men do not appear in Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française.

(Amidst discussion of a stark and haunting topic, a technical point: The databases at the SGA website give access to an extraordinary trove of historical and genealogical information. But, while records can be searched using the soldier’s date of birth, there is no search field for the date on which a casualty was incurred. Okay, back to the discussion…)

______________________________

What about Maurice Barrès’; what about his article?

The animating idea underlying M. Marcel Knecht’s laudatory introduction to Barrès’ article is that the circumstances of the Great War, with the nation of France in peril and its survival dependent upon the steadfast unity of all elements of its population, caused a sea-change – a “great transformation” (adopting Karl Polanyi’s appelation from an entirely different topic…), as it were – in the latter’s perception of the Jews of France. (And perhaps indirectly – albeit unaddressed in the essay – Jews, “in general”? But, that’s speculation…) This changed perception centrally manifested itself in terms of a straightforward appreciation of the dedication, valor, and willingness for self-sacrifice on the part of French Jewish soldiers, and secondarily, as the consequent willingness to accord the Jews of France a place within and of the national body – a place symbolic; yet a place quite real – paralleling that of other groups which together comprise the French nation.

But, that’s simplifying things a little. The issue at hand is more complex, for Barrès actually divides the Jews of France into two distinct groups.

One group is comprised of those Jews whose families have a long tradition of residence and ancestry in France, as evidenced in the opening paragraph, “Many Jews, settled in our midst for generations and centuries, are natural members of the national body,” and later, “But there are other Jews in large numbers, rooted for centuries and generations in the soul of France, and intimately identified with the joys and sorrows of the national life.”

Second, those Jews whose connection to France is been less immediate both temporally and geographically, their hhaving been born and raised in the country’s colonies (such as Algeria), or whose immediate ancestry even derives from the land of the nation’s foe, Germany, epitomized in the adjective “adopted”. This is seen in such comments as as, “Passing on to another portion of this category of adopted ones who conduct themselves as good Frenchmen in order to pay for and justify their adoption, I advance positive evidence, which brings us before a noble and ardent soul and introduces us into the midst of the intimate sufferings of Gallicized Israel,” and, “Let us now come a little nearer, and from this friend from the outside let us proceed to our adopted ones.”

In any case, however well-written the essay, Barrès’ closing and ending sentences are revealing, and a sign – perhaps intentional; perhaps taken-for-granted – of his perception of the nature and “place” (a place real; a place symbolic) of the Jewish people in the world, and in history.

First, there’s the sentence with which the very article commences, “For Israel in his eternal wandering, choosing a country is a matter of great importance.” Israel – the Jewish people – is definied by definition and nature as a wanderer; as eternally homeless, despite finding homes – a secularized political version of a Christian theological definition. Curiously, this seems at odds (perhaps Barrès’ himself neither perceived nor contemplated the contradiction!) with a not-so-passing reference to the re-establishment of a Jewish nation-state: “Did he [Amedee Rothstein] expect to obtain from the victory of the Allies the realization of the curious plans, which are not without grandeur, of Doctor Herzl, or did he, more simply and with more certainty, desire to increase through sacrifice the moral force and prestige of Israel? One word which he uttered leaves no doubt of the strength and direction of his thought. He told his friends he would meet them after the war in Palestine.”

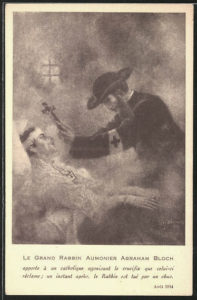

And, the closing paragraph, in reference to the death of Rabbi Abraham Bloch:

“The old families rooted for generations in the French soil will take, as their typical hero and standard-bearer, the Chief Rabbi of Lyons, who falls on the field of Honor offering a crucifix to the dying Catholic soldiers.

“In the village of Taintrux, near Saint-Die, in the Vosges, on the 29th of August, 1914 (on a Saturday, the sacred day of the Jews), the field hospital of the 14th Corps catches fire under the German bombardment. The stretcher-bearers, amid flames and explosions, carry away 150 wounded. One of the latter, mortally struck, asks for a crucifix. He asks it of M. Abraham Bloch, the Jewish chaplain, whom he takes for the Catholic chaplain. M. Bloch bestirs himself, he seeks, he finds, he brings to the dying man the symbol of the faith of the Christians. And a few steps further on, a shell strikes him down. He dies in the arms of the Catholic chaplain, Father Jamin, a Jesuit Father, whose testimony is proof of this incident.

“No comment could add aught to the feeling of sympathy inspired in us by such an act, so full of human tenderness. A long procession of instances has just shown us Israel striving in the war to demonstrate his attitude towards France. Step by step we have risen; here fraternity spontaneously meets its perfect gesture; the old Rabbi presenting to the dying soldier the immortal sign of Christ on the cross is a picture that will never perish.”

Aside from the historicity (actually, the lack thereof) of Barrès’ account of Rabbi Abraham Bloch’s death (about which you can read much more in English and French, from a translation and transcript, respectively, of the chapter “Mythe et réalité: la mort du grand rabbin Abraham Bloch“, from Philippe-E. Landau’s Les Juifs de France et la Grande Guerre) I’m struck by the symbolism and power of this tale in terms of the self-identity of French Jewry. It parallels (if it doesn’t even unintentionally anticipate!) the story of “The Four Chaplains” – at least, as reported during and promulgated after the Second World War – vis-a-vis the self-perception of American Jewry. (There were many other Jewish men – both soldiers and Merchant Marine crewmen – who became casualties during the loss of the U.S.S. Dorchester on February 3, 1943, whose names have vanished from history. Maybe more about that topic in the future…)

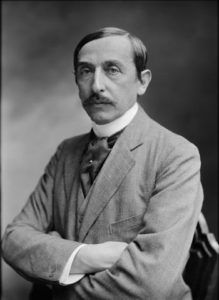

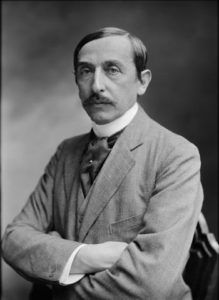

Anyway, back to Maurice Barrès’, the writer; the journalist; the politician, and simply, the man…

Born in 1862, he was fifty-five years old when Les Diverses Families Spirituelles de la France was published in 1917. He died only six years later, in 1923.

Did the composition of “les Israelites”, within Les Diverses Families Spirituelles de la France, mark a genuine sea-change in his beliefs about and attitude towards the Jewish people, or did this signify only a temporary moderation, modified by expediency, from his prior beliefs about the Jews – most evident during the Dreyfus Affair? I do not know. Now do I know if subsequent to 1917 he penned anything further about the Jewish people. (A cursory web search seems to yield no further writings in this vein.) Well, it’s notable that For And Against Dreyfus mentions that he, “…deduced Dreyfus’s guilt “by his race”, while in 1897, Les Déracinés, the first volume of his trilogy Roman de l’énergie nationale, rejected the legacy of the Enlightenment, which had made a moron of France.” However, his biography at Wikipedia (being cognizant of Wikipedia’s ideological bias) states, “During World War I, Barrès was one of the proponents of the Union Sacrée, which earned him the nickname “nightingale of bloodshed” (“rossignol des carnages”). … During the war Barrès also partly came back on the mistakes of his youth, by paying tribute to French Jews in Les familles spirituelles de la France, where he placed them as one of the four elements of the “national genius”, alongside Traditionalists, Protestants and Socialists – thus opposing himself to Maurras who saw in them the “four confederate states” of “Anti-France”.”

There is a winding road between these two extremes. Perhaps Barrès took only a temporary detour from a certain well-established ideological path; perhaps hegenuinely navigated to a land of different belief. Perhaps he remained somewhere between; perhaps the issue became moot, after a time.

In any event, onwards to his article, which you can view, and read, below.

________________________________________

__________________________

__________________________

______________________________

The Jews And The War

By Maurice Barres

Member of the French Academy

(Translation for The Jewish Exponent)

The article here presented for the first time in an English translation is notable not only because it comes from the pen of a member of the French Academy and one of the foremost European litterateurs of the day but because the glowing tribute paid to the Jewish people has been written by one who in the past has stood on the side of the enemies of the race, having lent his influence to the unenlightened activities of the anti-Semites. His new realization of the intrinsic worth of the Jews as a people and of the immense services which the Jews have rendered to the cause of France and her Allies in the great struggle for the freedom of the world, constitutes one more conversion of striking significance and illustrates anew one of the remarkable effects of the great awakening brought forth by the war. The author himself does not hesitate to refer to his change of views and in reviewing the correspondence of Robert Hertz, he says, “On various occasions my own name, now condemned, now praised, recurs under his pen, and I listen to our agreements and disagreements with the greatest attention, FOR THE WAR LEAVES US NOTHING, WHICH WE SHOULD REFUSE TO REVISE.” The article consists of a chapter from “Les Diverses Families Spirituelles de la France” (The Various Spiritual Families of France), a book by M. Barres, just published, in which the distinguished author describes how the diverse population of France has been welded into one whole by the struggle against a common enemy, and pays enthusiastic tribute to the different classes of people living in the country, which have attested their loyalty by sacrifice. M. Marcel Knecht, a member of the French High Commission to this country, who recently wrote in the Jewish press on the important role which the French Jews have played and are still playing in the present struggle, paid particular attention to the new book of M. Barres, asking for it the special consideration of the Jews in this country, “because this book contains the greatest praise for the Jewish attitude in the war.” He said further: “This book was written by a man who, during the Dreyfus affair, and who since has always been on the other side of the barrier. He is a Lorrainer, a great French writer, a member of the French Academy, a man occupying a great official position in the Nationalist Party of France, Maurice Barres, who was not particularly considered a friend of the Jews. He has written in this book a great chapter on the Jews, praising their heroism.”

__________________________

______________________________

MAURICE BARRÈS

MAURICE BARRÈS

OF THE FRENCH ACADEMY

PRESIDENT OF THE LEAGUE OF PATRIOTS

THE VARIOUS SPIRITUAL FAMILIES OF FRANCE

PARIS

EMILE-PAUL FRÈRES, EDITORS

100, RUE DE FAIBOURG-SAINT-HONORÉ. 100

PLACE BEAUVAU

1917

______________________________

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapters. – Pages.

I Our diversities disappear on August 4, 1914 – 1

II … And reappear in the army – 9

III The Catholics – 19

IV The Protestants – 51

V The Israelites – 67

VI The Socialists – 90

VII The Traditionalists – 137

VIII Catholics, Protestants, Socialists, all defending France, defend their particular faith – 193

IX An already legendary night (Christmas 1914) – 205

X Twenty-year-old soldiers devote themselves to creating a more beautiful France – 215

XI This profound unanimity, we will continue to live it – 259

Notes and Appendix – 269

PRINTING CHAIX, RUE BERGERE, 20, PARIS – 842-1-17. (Lucre Lurilleux)

__________________________

______________________________

For Israel in his eternal wandering, choosing a country is a matter of great importance. His country is not always a heritage from his ancestors; he acquires it then by an act of his free will, and he assumes his citizenship as a quality of which he is anxious to prove himself.

Many Jews, settled in our midst for generations and centuries, are natural members of the national body, but they are concerned that their newly-arrived co-religionists should prove their loyalty. In the early days of the war, when a hostile feeling rose up in the ancient Parisian Ghetto (in the fourth Arrondissement) against the Jews from Russia, Poland, Rumania and Turkey, a meeting was held in the home of one of the editors of the newspaper, The Jewish People (Le People Juif), of which it published a report, “Do you not think, “ said one, “that it is necessary to organize a special service for enlisted foreign Jews in order that it may become known that the Jews have also brought forward their contingent?”

The same day an appeal in French and Yiddish was addressed to the immigrant Jews inviting them to come and register in the rooms of the Jewish People’s University, 8 Rue de Jarente. It was received with enthusiasm, and, says The Jewish People, “Not one Jewish tradesman in the Jewish quarter failed to display a copy of it in his show window very prominently.” On the very next day, an enormous crowd thronged the rooms of the Jewish People’s University. Each one wished to be registered as soon as possible, and to be in possession of the card certifying to his enlistment, the magic card which opened the ranks of police officers and calmed the wrath of janitors and over-zealous neighbors. (Le People Juif, October, 1916.)

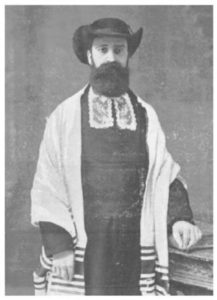

Eager young men, intellectuals, it seems, questioned, informed, exhorted, and registered these motley recruits. The most zealous was a 22 year old Jew, a student of the engineering school, small, frail, with gleaming, almost feverish eyes, with a strong and aggressive spirit. This young enthusiast dreamed of creating a veritable Jewish legion. Rothstein was a Zionist. By this devotion given to France, he was sure that he was serving the cause of Israel.

How did he understand it? Did he expect to obtain from the victory of the Allies the realization of the curious plans, which are not without grandeur, of Doctor Herzl, or did he, more simply and with more certainty, desire to increase through sacrifice the moral force and prestige of Israel? One word which he uttered leaves no doubt of the strength and direction of his thought. He told his friends he would meet them after the war in Palestine.

When all had enlisted, he himself signed the sheet.

Having departed as a simple soldier, Amidee Rothstein was promoted second lieutenant then mentioned in an army order “for having displayed remarkable vigor and coolness to the admiration of the infantry officers and of his men,” and finally made a Knight of the Legion of Honor, “for having particularly distinguished himself on the 25th of September, 1915, by being the first to leave the trenches, and vigorously carrying his men along with him, which helped to give superb dash to our first wave of assault.”

We should like to be familiar with the thought, the wonderments, the sympathies, the hopes of this young hero of Israel amid the soldiers and landscapes of France, in a moral atmosphere so different from his own spirit, but with which he was intoxicated, and wished to enrich himself.

I have read his analysis of the treatise by Pines on “Yiddish Literature,” an analysis quite brief and unadorned, which makes us regret a more considerable work, “too subjective, too personal,” we are told, which he had devoted to the same subject. “Such as they are, these ten pages, where he hears the Jewish people speak, reveal his fixed idea, his obsession on the sufferings and hopes of Israel, his gaze towards Palestine. He seems to place over everything the feeling of national pride, which he endeavors to reconcile with the ideal of humanity.”

We have his ultima verba, in a letter addressed to his chaplain, Mr. Leon Sommer. “At the present moment,” says he, “I hold my life as wholly sacrificed, but if fate should be kind enough to spare me, after the war I shall consider my life as no longer belonging to me, and, after having done my duty towards France, I shall devote myself to the great and unhappy Jewish people from whom I am descended. My dear chaplain, in case I should die, I should very much like to sleep under the Shield of David. A Mogen David would rock me with a last thrill and my soul would he happy in the thoughts of sleeping my eternal sleep under the shadow of the emblem of Zion.

On the 18th of August, 1916, Lieutenant Rothstein fell at the head of his men, struck by a bullet in the forehead.

______________________________

Sous Lieutenant Amadee Rothstein

Sous Lieutenant, 1635, France (Egypte), Armée de Terre, Legion d’Honneur

Sous Lieutenant, 1635, France (Egypte), Armée de Terre, Legion d’Honneur

Légion étrangère, Regiment de Marche de la Legion Etranger

(“En subsistance au 4eme Regiment de Afrique”)

Killed by the enemy [Tué a l’ennemi] August 18, 1916 at Fortin Route du Fort de Vaux / Verdun a Vaux, Meuse, France

Born June 20, 1891, Cairo, Egypt

l’Univers Israélite 9/8/16 (article), 11/16/17

Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française 1921, p. 72 (“Rothstein, Amedee”)

l’Univers Israélite: “Inhume a Haudainville (Meuse), avec le ministere de M. Sommer, aumonier militaire. Il aviat ete cite deux fois a l’ordre de l’armee en fait chevalier de la Legion d’honneur”

Specific place of burial unknown

______________________________

There is something painful and alluring in the destiny of a young spirit who regards the world exclusively through the Jewish nation, and who dies in the service of those he loves most, but from whom he insisted on being distinguished. It is one of the innumerable trials of wandering Israel.

Let us now come a little nearer, and from this friend from the outside let us proceed to our adopted ones.

The Algerian Jews, during the war, show us Israel just united to French civilization, and ardently eager to partake of our rights, our duties and our sentiments. Forty-five years ago they had not a single right. Cremieux suddenly granted them a privilege which greatly upset the Arabs. He decreed them French citizens. The nobility of this title, the prerogative attached to it, and our education seem to have transformed them into patriots. Their fathers were only familiar with commerce, but they thrilled with the call to arms. They departed, I am told, with great enthusiasm. A witness assures me that they were heard to exclaim: “We will throw ourselves on the Boche, and we will bury our bayonets in their bodies with the battle cry of the Eternal.”

The cry is superb, and carries out imagination back to old Biblical times and to the Maccabaean epic. One authorized to speak in their name writes me as follows:

“They are serving for the most part in the Zouaves, and were there (until recently) in the proportion of one in four. They have fought in the battle of Belgium, of the Marne (particularly at Chamigay), before Soissons, in Arras, on the Yser, in Champagne, at Verdun, on the Somme, at the Dardanelles, in Servia. It is especially in the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 8th Zouaves, which included them in the beginning. The 45th Division, formed in Oran of reservists and territorialists, is the one which went through Paris the first days of September, and which was immediately sent by Galliene to the neighborhood of Meuse, there to deliver the blow which was decisive.”

Passing on to another portion of this category of adopted ones who conduct themselves as good Frenchmen in order to pay for and justify their adoption, I advance positive evidence, which brings us before a noble and ardent soul and introduces us into the midst of the intimate sufferings of Gallicized Israel.

I have before me the family correspondence of Robert Hertz, student of the Normal College, professor of philosophy in the college of Douai, founder of the Socialist Memoranda, the son of a German Jew. And it is this last circumstance which constitutes the tragedy of his position and his psychology. His letters to his wife are admirable in their fullness and warmth. I should not be fair to him if I did not mention his love for his hearthstone, his vigorous intellectual curiosity which operates in the most original manner even in the course of the war, his entire satisfaction with that military discipline where he satisfied what he calls his “nostalgia for the absent cathedral,” and finally his indomitable and deliberate will [to] go “to the limit.” On various occasions my own name, now condemned, now praised, recurs under his pen, and I listen to our agreements and disagreements with the greatest attention, for the war leaves us nothing which we should refuse to revise. But I shall not stop; I hurry on almost brutally, for the very honor of this Robert Hertz, to his naked and quivering thought, “If I fall,” he writes to his wife, “I shall have discharged only a very small part of my debt to our country.”

And on this point this splendid passage:

“My dearest, I recall my dreams when I was very little, and later a student in d’Alma Avenue. With all my being, I wanted to be a Frenchman, to deserve to be one, to prove that I was one, and I dreamed glorious deeds in the war against William. Then this desire for “integration” took another form, for my Socialism proceeded largely from it.

“Now the old boyish dream lives again in me, more ardent than ever. I am grateful to my chiefs who accept me as their subordinate, to the men whom I am proud to command, to them, the children of a people truly elect. Yes, I am filled with gratitude to the fatherland which receives me and crowns me. Nothing will be too much to pay for that, so my little lad can always walk with head erect, and, in the France restored, to free from the torment which poisoned many hours of our childhood and youth. ‘Am I a Frenchman? Do I deserve to be one? No, little one you will have a country and yes you will be able to walk proudly on the earth, nourishing yourself with this assurance: ‘My daddy was there, and he gave everything to France.’ As for me, if I need any, this thought is the sweetest reward.

There was something in the position of the Jews, especially in the recently arrived German Jews, which was dubious and irregular, clandestine and spurious. I consider this war as a welcome opportunity to ‘regularize the situation’ for ourselves and for our children. Afterwards, they will be able to work, if they so please, for the super and international ideal, but first of all, one must demonstrate by deeds that one is not beneath the national ideal.

The author of this testament signed it with his blood, certified it with his death, Robert Hertz was killed on the 13th of April, 1915, at Marcheville, at the time second lieutenant in the 330th Infantry. I do not think it would be possible to find a text revealing with greater strength and feeling the passionate desire of Israel to lose himself in the French soul.

______________________________

Sous Lieutenant Robert Walter Hertz

Sous Lieutenant, 453, Armée de Terre, 330eme Regiment d’Infanterie

Sous Lieutenant, 453, Armée de Terre, 330eme Regiment d’Infanterie

Killed by the enemy [Tué a l’ennemi] April 13, 1915; Died on the field [Mort sur le terrain] at Marcheville, Meuse, France

Born June 22, 1881, Saint Cloud, Seine, France

l’Univers Israélite 10/8/15

Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française 1921, p. 42

l’Univers Israélite: “Eleve diplome de l’Ecole des Hautes-Etudes”

Place of burial unknown

______________________________

Such are the Jews recently arrived among us and in whom the unreasoning, almost animal part which there is in our love for our fatherland does not exist. Their patriotism is wholly spiritual, an act of the will, a decision, a choice of the spirit. They prefer France, that country presents itself to them as a freely constituted association. Moreover, they are able to find in this very condition a reason for devotion, and Robert Hertz, the son of a German, shows us in admirable manner that, knowing himself to have been adopted, he wished to conduct himself in such a way as to be worthy of his adoption. But there are other Jews in large numbers, rooted for centuries and generations in the soul of France, and intimately identified with the joys and sorrows of the national life. I ask myself what patriotic support do they find in their religion? What remains in them of pious Israel of old, and what aid does the latter offer to its sons engaged in the war?

The chief rabbi of the Central Consistory of France, in a letter which I have before me, answers: “My chaplain and myself have, since the beginning of the war, established the fact that there has been a great return of faith among the Jewish soldiers which fuses with their patriotic enthusiasm.” Nevertheless, I have no documents in my possession. I point out in simple good faith, the gaps in my investigation. The documents which I possess on the moral elite among the Jews introduce me only to such spirits as appear to be devoid of their religious tradition. They are all free thinkers. [Subsequently, Mr. Barres received a number of communications, revealing the fact that with many of the Jewish soldiers fighting and dying for France, their religion is a great element in the sum of their moral strength.]

The free thinkers who emerge from Catholicism or Protestantism subsist, in large measure, on the ancient Christian foundation; for centuries they have been prepared in the little village churches. But these Jews, what is their devotion and resignation made of? What has the spirit of wisdom which rests in the shadow of the old synagogue told them? Towards what synagogue of Jehovah do they incline when they pronounce the Fiat voluntas tua? And how do the gradations of their assent group themselves on the moral scale which runs from painful expectancy to joyful eagerness for self-sacrifice.

One young Jew gives us an answer to these great questions. Roger Cahen, recently graduated from the Normal College, less than 25 years old, is a second lieutenant in the forests of Argonne. Under the German fire, he gives himself up voluptuously to an inspection of his conscience of which his letters gives us a sketch. Clear and strong, with all the buddings which promise great talent, they exhale the confidence of a young intellectual who, speaking to his family, to loyal friends, to his old teacher, M. Paul Derjardine, is not afraid to reveal his pride and his spiritual freedom. They are like to many little meditations where it is clearly seen that the young soldier looks for and finds only himself in all the chaos of this war. Roger Cahen does not venture beyond the circle of light which is shed by his small inner frame. “I do not believe in any dogma of any religion,” he writes. That was his view before the war, he confirms himself in it in December, 1915, two months before his heroic end. “I have just read the Bible. It is for me a collection of tales, of old and charming stories. I do not look for, nor do I find in it anything else but poetic emotions.”

It is poetic emotions, also, which he looks for in war, and he finds many very beautiful ones. I believe him entirely when he writes: “I have within me a fund of joyousness without end, a soul which is fresh and pure, receptive to everybody and to every sensation. Every morning I have the feeling that I have only just been born and that I am seeing the vast world for the first time.” Certain of his letters written on his knees, in the light of a small wax candle, five meters under the ground, are of great lyric power. Listen reverently to this fragment of eternal poesy:

“Splendid of the nascent day, no hymn can equal that which rises up in the soul of the men who watch in the trenches, when, after hours of expectance they first feel, and then see appear and grow the light triumphant. At those moments, I have a whole orchestra within me. If I could only write down this inward music which no concert will ever restore to me. If you only knew how rich and beautiful are the emotions of the dearly beloved day into the world.”

In the bottom of the first line trenches he notes down that the only events in his history are “the changes in the natural order, nightfall, dawn, an overcast or starry sky, the war with or the coolness of the air. This amalgamation with the life of the world gives to our own life an incomprehensible grandeur and beauty”

Thus bound up with the universal splendor, he defies destiny. “I am confident that whatever happens today, tomorrow, in a week, I have shown myself lofty enough to dominate events and to look at them only with curiosity.”

All that is summarized in this confession of faith:

“At the risk of appearing insane to you, I declare with all my soul and conscience that I love to be here. I love the first line trenches as an incomparable “Thinkery.” Here you retire into yourself, with all your powers concentrated: here you enjoy complete fullness of life. I am here as under a reflector. I see myself here under a very keen light with a clearness which better than any study chamber encourages self analysis.”

To each one of his letters, his conclusion is always that henceforth he considers himself a good and strong instrument. It is the refrain and the mainspring of his daily thought. He has found his rule of life and his road. He is sure of himself.

This is his manner in pronouncing in his turn the flat voluntas tua:

“I endeavor to take advantage of my isolation and of the keenness of mind induced by danger for knowing myself better. If you only knew with what simplicity one looks upon oneself and judges oneself in this region. I have succeeded unto the present in maintaining myself in a state of philosophic equanimity and indifference of constant resignation.”

There it is, this universal word, resignation. And it’s not a word alone, it is indeed the thought. Very warm and noble, profoundly painful for those who listen to it with perfect sympathy, but for him shot through with a joyful peace:

“I have forbidden myself to pass judgment on the value of the events of my life; I accept them all as opportunities which fate offers me for knowing myself better and for improving myself.”

It is true that he is unique, but how can one read him without loving him, this young intellectual who died at the age of 25 years for France. Indeed, he is happy that besides here there were Reguy, Psichari, Marcel Drouet and the young Leo Latil, Jean Rival Cazalia, luminous children all. His spiritual freedom, his isolation, his fine and noble voluptuous nature, are yet a form of courage very elegant and very strong. Roger Cahen continues, revives, and broadens a conception of life which we so much loved a quarter of a century ago. He seals it with heroism. Having fallen in the field of honor, in that Argonne where, for six months he had indefatigably listened to his thoughts, he is cited in the order of the 18th Brigade of Infantry, and wept for, a sergeant tells us, by the men in his company.

______________________________

Caporal Roger Cahen

Caporal, 7586, Armée de Terre, 149eme Regiment d’Infanterie

Caporal, 7586, Armée de Terre, 149eme Regiment d’Infanterie

Killed in combat by gunshot [Tué par coup de feu au combat] May 9, 1915

at Aix-Noulette, Pas-de-Calais, France

Born October 17, 1892, Havre, Seine-Inferieure, France

l’Univers Israélite 12/7/17

Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française 1921, pp. 21 and 26 (Name appears as both “Cahen, Roger” and “Cohen, Roger”)

Place of burial unknown.

______________________________

Roger Cahen, Robert Hertz, Amedee Rothstein, all of these strong individualized figures, present something rare and singular. I like to follow in their various epochs, the stages, the formation of a personality, the young Jewish intellectual, who for several years has been playing a big role in France, but I do not offer them as representatives of the Jewish French community. The old families rooted for generations in the French soil will take, as their typical hero and standard-bearer, the Chief Rabbi of Lyons, who falls on the field of Honor offering a crucifix to the dying Catholic soldiers.

In the village of Taintrux, near Saint-Die, in the Vosges, on the 29th of August, 1914 (on a Saturday, the sacred day of the Jews), the field hospital of the 14th Corps catches fire under the German bombardment. The stretcher-bearers, amid flames and explosions, carry away 150 wounded. One of the latter, mortally struck, asks for a crucifix. He asks it of M. Abraham Bloch, the Jewish chaplain, whom he takes for the Catholic chaplain. M. Bloch bestirs himself, he seeks, he finds, he brings to the dying man the symbol of the faith of the Christians. And a few steps further on, a shell strikes him down. He dies in the arms of the Catholic chaplain, Father Jamin, a Jesuit Father, whose testimony is proof of this incident.

No comment could add aught to the feeling of sympathy inspired in us by such an act, so full of human tenderness. A long procession of instances has just shown us Israel striving in the war to demonstrate his attitude towards France. Step by step we have risen; here fraternity spontaneously meets its perfect gesture; the old Rabbi presenting to the dying soldier the immortal sign of Christ on the cross is a picture that will never perish.

__________________________

______________________________

– .ת. נ. צ. ב. ה –

תהא

נפשו

צרורה

בצרור

החיים

April 13, 1915 – Sous Lieutenant Robert Walter Hertz

Jewish Casualties in the French Army

Cahen, Rene, Caporal, France, 1957, Meurthe-et-Moselle; bois le Pretre

Israel, Lucien, Caporal Fourier, France, 17557, Meuse; Verdun; l’Hopital No. 1

Jewish Casualties in the German Army

Cohen, Siegfried, Soldat, 21 Bayerisch Reserve Infanterie Regiment, 2 Battalion, 6 Kompagnie, at Apremont

Goldmann, Leo Alfred, Soldat, 36 Landwehr Infanterie Regiment, 2 Battalion, 5 Kompagnie – Kriegsgräberstätte in Harville (Frankreich), Grab 110

Schloss, Moritz, Kriegsfreiwilliger, I Bayerische Armee Korps, 2 Landwehr Eskadron

Steinitz, Bernhard, Unteroffizier, 93 Reserve Infanterie Regiment 93, 1 Battalion, 3 Kompagnie – Ulrichstein-Jüdischer Friedhof

May 9, 1915 – Caporal Roger Cahen

Jewish Casualties in the French Army

Aberbach, Tobie, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 25537, Pas-de-Calais; Berthonval

Abram, Pierre, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Italie), 19535, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Abramovitch, David, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 20487, Pas-de-Calais; Mont-Saint-Eloi (pres); Berthonval

Astruc, Mail, Caporal, France (Bulgarie), 19272, Pas-de-Calais; Berthonval

Barkan, Jacques, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 23139, Pas-de-Calais; La Targette

Baur, Georges Henri Victor, Sergent, France, 12156, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Ben Hamou, David, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Algérie), 1639, Belgique; Nieuport-Bains

Ben Mouchi, Isaac Zenon, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Algérie), 18775, Turquie; Dardanelles; Gallipoli Peninsula

Ben Soussan, Abraham, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Algérie), 995, Belgique; Nieuport

Benarroche, Isaac, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Algérie), 4623, Pas-de-Calais; Roclincourt

Benbassat, Moise, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Turquie), 20110, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Berkovitch, Berg, Canonnier Servant de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 23184, Pas-de-Calais; Berthonval

Berlevy, Moise Herich David, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 23028, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Chait, Moise, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 26319, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Cherki, Moise, Caporal, France (Algérie), 16297, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Chwat, Nathan, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Pologne), 25411, Pas-de-Calais; Berthonval

Cohen, Liaou, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Algérie), 994, Belgique; Nieuport

Czajkowski, Boleslas Charles, Sous Lieutenant, France (Turquie), 9038, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Daici, Elias, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France, 26788, Pas-de-Calais; La Targette

David, Louis, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Italie), 26087, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Davidovici, Salomon, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Roumanie), 27022, Pas-de-Calais; Mont-Saint-Eloi

Dobrowolski, Ronald, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Pologne), 25389, Pas-de-Calais; Berthonval

Dores, Rahmiel Faivel, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 23567, Pas-de-Calais; La Targette

Evlagon, Vitali, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Turquie), 22914, Pas-de-Calais; Berthonval

Fain, Judas, Caporal, France (Algérie), 1841, Somme; Abbeville

Feldmann, Charles Maurice Albert, Sergent, France, 12243, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Fogelbaum, Salomon, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Pologne), 20456, Pas-de-Calais; La Targette

Frankel, Felix, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France, 6378

Fried, Jean, Soldat de 1ere Classe, France (Roumanie), 22953, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Garbarovitz, Albert, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 26409, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Gerchinovitz, Valodia, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 23489, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Ginsbourg, Simon, Soldat, France (Russie), 23130, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Goldberg, Guibel, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Pologne), 25446, Pas-de-Calais; secteur de Berthonval

Goldenberg, Salomon, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Turquie), 26836, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Golstein, Faivel, Soldat de 1ere Classe, France (Pologne), 26469, Pas-de-Calais; secteur de Berthonval

Gourevitz, Isaac, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 26362, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Guez, Emmanuel, Caporal, France (Algérie), Belgique; Nieuport

Haron, Maurice, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Egypte), 21598, Pas-de-Calais; La Targette

Herscu, Joseph, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Roumanie), 24462, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Kandel, Leib Leon Ori Selig Georges, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 26495, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Katz, Francois, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Pologne), 29188, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Katzigna, Abraham, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 26339, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Konetzki, Jacques, Soldat de 1ere Classe, France (Russie), 26892, Pas-de-Calais; nord de Arras

Krakouschansky, Helcite, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 23396, Pas-de-Calais; Berthonval

Leiba, Moise, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Roumanie), 26907, Pas-de-Calais; La Targette

Leibovici, Nahman Georges, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Roumanie), 26901, Pas-de-Calais; La Targette

Levine, David, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 26916, Pas-de-Calais; secteur de Berthonval

Levy, Chaim Lemel, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Pologne), 23023, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Levy, Isaac, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Turquie), 22973, Pas-de-Calais; La Targette

Levy, Max Jean Francois Claude, Sergent Major, France, 16063 / 16635, Pas-de-Calais; Carency

Levy, Paul Emile, Lieutenant, France, 45, Pas-de-Calais; Berthonval / Mont Saint Eloi

Litwak, Levy, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 20586, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Manassohn, Isaac, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Pologne), 23573, Pas-de-Calais; Saint Vaast; secteur de Berthonval

Migdal, Leibus, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Pologne), 25386, Pas-de-Calais; Berthonval,

Miller, _____, France (Indefini)

Moscowitch, Maurice, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Egypte), 27086, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Novak, Antoine, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Hongrie), 25283, Pas-de-Calais; secteur de Berthonval

Picard, David, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France, 823, Pas-de-Calais; Carency

Posner, Nathan, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Roumanie), 26970, Pas-de-Calais; Berthonval

Praschker, Idel, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), Pas-de-Calais; La Targette

Rapaport, Boris, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Israël), 26986, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Rosa, Joseph, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Pologne), 25373, Pas-de-Calais; secteur de Berthonval

Rosenbaum, Hermann, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 34017, Pas-de-Calais; Berthonval

Roterman, Moschelt, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 26486, Pas-de-Calais; La Targette

Rotker, Victor, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Pologne), 23051, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Rousseau, Daniel, Adjutant, France, 27968, Pas-de-Calais; secteur de Berthonval

Schapiro, Simon, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 26337, Pas-de-Calais; Berthonval

Schlitt, Aron, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 23548, Pas-de-Calais; La Targette

Schtraim, Ilhaim, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 26493, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Schulman, Abraham, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 23148, Pas-de-Calais; La Targette

Sklarewski, Samuel, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 23411, Pas-de-Calais; Mont-Saint-Eloi

Sobol, Barouch, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 20449, Pas-de-Calais; secteur de Berthonval

Spack, Salomon, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 23475, Pas-de-Calais; La Targette

Tchellebides, Clement, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Turquie), 22401, Pas-de-Calais; secteur de Berthonval

Terner, Aron, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Roumanie), 19617, Pas-de-Calais; La Targette

Tiano, Moise, Soldat de 1ere Classe, France (Grèce), 22909, Pas-de-Calais; La Targette

Waichmann, Israel, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Pologne), 23502, Pas-de-Calais; secteur de Berthonval

Wechsler, Sigmund, Soldat de 1ere Classe, France (Roumanie), 27053, Pas-de-Calais; Berthonval

Weichman, Schulim, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 23094, Pas-de-Calais; La Targette

Weil, Alphonse, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France, 8236, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Weinberg, Casimir, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Pologne), 25383, Pas-de-Calais; secteur de Berthonval

Weinberg, Lazare Rene, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France, 9690, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Wolger, Mayer, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 26313, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Wunenberger, Francois Leon, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France, 22311, Pas-de-Calais; secteur de Berthonval

Yakar, Isaac, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Turquie), 23075, Pas-de-Calais; Neuville-Saint-Vaast

Zenou, Mouchi ben Isaac, France (Indefini), Turquie; Dardanelles; Gallipoli Peninsula

Zerbib, Nathan, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Algérie), 2375, bord du Ceylan

Zimmerling, Michel, Caporal, France (Russie), 23700, Pas-de-Calais; Berthonval

The names of twenty-seven of the above men do not appear in Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française. They are: Aberbach, Benbassat, Berkovitch, Berlevy, Chait, Liaou Cohen, Dobrowolski, Fried, Gerchinovitz, Herscu, Francois Katz, Katzigna, David Levine, Chaim Lemel Levy, Isaac Levy, Migdal, Moscovitch, Praschker, Rotker, Schapiro, Schtraim, Sklarewski, Wechsler, Weinberg, Wolger, and Yakar

Jewish Casualties in the German Army

Blass, Max, Soldat, 12 Bayerisch Reserve Infanterie Regiment, 2 Battalion, 8 Kompagnie, at Arras – Kriegsgräberstätte in St.Laurent-Blangy (Frankreich), Kameradengrab

Blumenthal, Otto, Soldat, 55 Infanterie Regiment, 2 Battalion, 5 Kompagnie – Kriegsgräberstätte in Illies/Nord (Frankreich), Block 5, Grab 1

Bodenheimer, Arthur, Unteroffizier / Landsturmmann, 201 Reserve Infanterie Regiment, 3 Battalion, 10 Kompagnie – Kriegsgräberstätte in Langemark (Belgien), Block A, Grab 4842

Burger, Fritz, Soldat, 7 Bayerisch Reserve Infanterie Regiment, 3 Battalion, 10 Kompagnie, Bayoneted by a Senegalese soldier, Died while Prisoner of War on 5/15/15, at French Military Hospital, Le Mans

Davidsohn, Ludwig, Unteroffizier, 110 Infanterie Regiment, 2 Battalion, 8 Kompagnie

Ephraim, Eduard, Soldat, 208 Reserve Infanterie Regiment, 1 Battalion, 1 Kompagnie

Freimann, Sigmund, Gefreiter, 10 Bayerisch Reserve Infanterie Regiment, 1 Battalion, 1 Kompagnie, at Neuville

Gerechter, Georg, Soldat, 208 Reserve Infanterie Regiment, 3 Battalion, 12 Kompagnie

Gross, Salo, Soldat, 205 Reserve Infanterie Regiment, 1 Battalion, 1 Kompagnie

Herrmann, Friedrich, Soldat, 111 Infanterie Regiment, 1 Battalion, 2 Kompagnie

Itzig, Georg, Gefreiter, 206 Reserve Infanterie Regiment, 1 Battalion, 2 Kompagnie

Laibon, Abraham, Soldat, 55 Infanterie Regiment, 3 Battalion, 11 Kompagnie

Levy, Julius, Unteroffizier, 14 Feldartillerie Regiment, 1 Battalion, 4 Kompagnie – Kriegsgräberstätte in Lens-Sallaumines (Frankreich), Block 11, Grab 155

Lilienfeld, Bernhard, Soldat, 39 Landwehr Infanterie Regiment 39, 1 Battalion, 2 Kompagnie

Lowy, Ernst, Soldat, 13 Bayerisch Reserve Infanterie Regiment, 3 Battalion, 11 Kompagnie, at Bukow, Galizia, Poland

Mendel, Emanuel Emil, Soldat, 39 Landwehr Infanterie Regiment, 1 Battalion, 4 Kompagnie

Mey, Salomon, Soldat, 39 Landwehr Infanterie Regiment, 1 Battalion, 1 Kompagnie

Mischlowitz, Siegfried, Soldat, Lehr Infanterie Regiment, 1 Battalion, 4 Kompagnie

Neufeld, Herbert, Soldat, 109 Leib Grenadier Regiment, 3 Bataillon, 9 Kompagnie

Nussbaum, Julius, Unteroffizier, 13 Bayerisch Reserve Infanterie Regiment, 3 Battalion, 11 Kompagnie, at Bukow, Galizia, Poland

Oppenheimer, Salli, Unteroffizier, 77 Landwehr Infanterie Regiment, 1 Battalion, 4 Kompagnie

Philipp, Hans, Dr., Oberleutant, 7 Bayerische Reserve Infanterie Regiment, Maschinen-Gewehr Kompagnie, at Souchez – Kriegsgräberstätte in St.Laurent-Blangy (Frankreich), Kameradengrab

Rauschmann, Willi, Soldat, 206 Reserve Infanterie Regiment, 1 Battalion, 1 Kompagnie

Reich, Siegfried, Soldat, 231 Reserve Infanterie Regiment, 2 Battalion, 7 Kompagnie

Reichhold, Louis, Soldat, 10 Bayerisch Reserve Infanterie Regiment, 3 Bataillon, 9 Kompagnie, at Neuville – Kriegsgräberstätte in St.Laurent-Blangy (Frankreich), Kameradengrab

Silberbach, Arthur, Soldat, 55 Infanterie Regiment, 3 Battalion, 10 Kompagnie – Kriegsgräberstätte in Illies/Nord (Frankreich), Block 5, Grab 3

Thal, Adolf, Gefreiter, 73 Landwehr Infanterie Regiment, 3 Battalion, 11 Kompagnie

Weinstein, Artur, Soldat, 205 Reserve Infanterie Regiment, 2 Battalion, 5 Kompagnie – Kriegsgräberstätte in Vladslo (Belgien), Block 8, Grab 905

August 18, 1916 – Sous Lieutenant Amadee Rothstein

Jewish Casualties in the French Army

Amsellem, Salomon, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Algérie), 24892, Somme; Maurepas

Attar, _____, France (Indefini) (“Partie a Remplir par le Corps” card could not be found or identified in SGA database)

Ben Simon, Joseph David, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France, 26067, Somme; Maurepas

Benchetrith, Jacob, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Algérie), 21048

Canoui, Elie, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Algérie), 6454, Somme Maurepas

Dahan, Rene, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Algérie), 21054, Somme; Maurepas

Danziger, Manasse Michel, Aspirant, France, 8025, Meuse; Vaux Chapitre

Fischhof, Robert Eugene, Sous Lieutenant, France, Somme; Maurepas

Godchaux, Alcide, Sous Lieutenant, France, Somme; Maurepas; sud de

Levine, Albert, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Pologne), 33288, Meuse; Vaux; Damloup

Saada, Isaac, Soldat, France (Algérie), 16818, Somme; Maurepas

Jewish Casualties in the German Army

Guggenheim, Hartwig, Unteroffizier, 692 Fussartillerie Batterie

Hermann, Siegfried, Soldat, 55 Landwehr Infanterie Regiment

Hirsch, Helmut, Soldat, 80 Reserve Infanterie Regiment, 3 Battalion, 12 Kompagnie

Lemberger, Julius, Soldat, 119 Grenadier Regiment, 3 Battalion, 10 Kompagnie

Minkel, Max, Soldat, 68 Infanterie Regiment, 1 Battalion, 3 Kompagnie

Neumann, Markus, Soldat, 144 Infanterie Regiment, 2 Battalion, 8 Kompagnie

Priester, Max, Unteroffizier, 64 Reserve Infanterie Regiment, 3 Battalion, 12 Kompagnie

Simon, Fritz, Soldat, 1 Garde Reserve Regiment, 2 Battalion, 7 Kompagnie

Stern, Isaak, Soldat, 123 Grenadier Regiment, 1 Battalion, 4 Kompagnie

Wolf, Aloys, Unteroffizier, 364 Infanterie Regiment, 1 Battalion, 4 Kompagnie

References and Suggested Readings

Barrès, Maurice, Les diverses familles spirituelles de la France, Paris, Émile-Paul frères, Paris, France, 1917, at Archive.org

Maurice Barrès, at Wikipedia

Maurice Barrès, at For and Against Dreyfus

Maurice Barrès, at Radical Right Analysis

Maurice Barrès, (photographic portrait by Atalier de Nadar [Photo (C) Ministère de la Culture – Médiathèque du Patrimoine, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Atelier de Nadar]), at images d’art

Englund, Steven, An Affair As We Don’t Know It (Book Review of An Officer and A Spy, by Robert Harris), at Jewish Review of Books, Spring, 2015

Weber, Eugen, Inheritance and Dilettantism: the Politics of Maurice Barrès, Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Summer/été 1975), pp. 109-131, at JSTOR

Die Jüdischen Gefallenen Des Deutschen Heeres, Deutschen Marine Und Der Deutschen Schutztruppen 1914-1918 – Ein Gedenkbuch, Reichsbund Jüdischer Frontsoldaten, Forward by Dr. Leo Löwenstein, Berlin, Germany, 1932

Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française (Israelites [Jews] in the French Army), Angers, 1921 – Avant-Propos de la Deuxième Épreuve [Forward to the Second Edition], Albert Manuel, Paris, Juillet, 1921 – (Réédité par le Cercle de Généalogie juive [Reissued by the Circle for Jewish Genealogy], Paris, 2000)

“Died for France in the First World War” “PARTIE À REMPLIR PAR LE CORPS (‘PART TO BE COMPLETED BY THE CORPS’)” forms, at Morts pour la France de la Première Guerre mondiale

French Military War Graves, at Sépultures de Guerre