To have a “place” can mean different things: A place can be a physical location; it can be a relationship to others, be they family, friends, or strangers; it can imply a sense of familiarity with and belonging to the zeitgeist of a particular age. And sometimes, it can be all these definitions – changing in degree and intensity – at once.

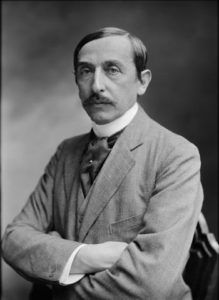

For the French writer, journalist, and politician Auguste-Maurice Barrès’, the “place” of the Jews of France during that nation’s hour of crisis in the First World War was addressed by the chapter “The Israelites” in his 1917 book Les Diverses Families Spirituelles de la France (The Various Spiritual Families of France), the full text of which you can read in English, and, the (original) French.

While the above-mentioned chapter (one of eleven within his book) comprises 23 pages, his monograph includes a “Notes and Appendix” section of 41 pages (page 268 through page 309). For chapter Five – “The Israelites” – relevant material can be found on pages 282 through 292, correlating to footnotes #12 through #14 in chapter Five.

As a supplement to my earlier posts covering the “The Israelites”, and to fully appreciate Barrès’ writings Jews in the French Army, you can read a translation of the relevant pages of the Notes and Appendix section, below. And, (yet!) further below, near the end of the post) you can read the text in the original French.

Intriguingly, from the Notes and Appendix section of the book, it can be seen that despite his attitude towards French Jewry during the Dreyfus affair, by 1917 Barrès’ had been engaging in correspondence with Jewish soldiers serving in the French Army, and, some representatives of the Jewish community of France. Similarly, paralleling the contents of Chapter Five, in the Notes and Appendix Barrès alludes to three Jewish soldiers who fell for France:

The first (anonymous) soldier – “Aged 33, sergeant to the 360th Infantry Regiment, this Jewish soldier took part in the fighting of Reméreville, Crévic, Bois Saint-Paul, Velaine-sôus-Ainance, from August 25 to September 14, 1914.” The second soldier – mentioned by name – Charles Halphen, who served in the 39th Artillery Regiment, and was killed in action on May 15, 1915. The third soldier – also mentioned by name – Captain Raoul Bloch, killed on May 12, 1916, near Verdun. The information about the anonymous 33-year-old sergeant was of such accuracy that I was immediately able to identify him, based on his archival record from the SGA, and, information in Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française. He was Sergent-Major Max Jean Francois Claude Levy.

It’s particularly notable that the biographical backgrounds of Bloch, Halphen, and Levy, all deeply patriotic, encompass a wide spectrum of religious belief (particularly represented by Max Levy) and represent different levls of acculturation.

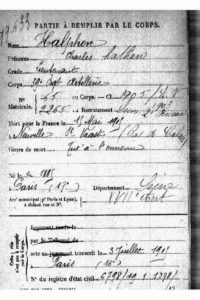

Paralleling my post about “The Israelites“, this post presents “PARTIE À REMPLIR PAR LE CORPS (‘PART TO BE COMPLETED BY THE CORPS’)” Cards for Levy, Halphen, and Bloch, and includes biographical information about each soldier as derived from both the Cards and other sources, such as l’Univers Israélite (reviewed at the Dorot Jewish Division of the New York Public Library), and the above-mentioned Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française. And…just like my prior post…to enable you to distinguish between my additions and the original text more easily, “my” information is presented in maroon-colored text, like this. (Refer to my earlier post, Three Soldiers – Three Brothers? – Fallen for France: Hermann, Jules, and Max Boers) for a longer discussion about information in “PARTIE À REMPLIR PAR LE CORPS (‘PART TO BE COMPLETED BY THE CORPS’)” Cards.)

In addition, this post lists the names of French Jewish soldiers who lost their lives on the same dates as Levy, Halphen, and Bloch. The record for each of the soldiers comprises that soldier’s 1) rank, 2) country or land of birth, and, 3) the geographic location where he was killed. All these names were obtained from the SGA’s Base des Morts pour la France de la Première Guerre mondiale (Database of Killed for France in the First World War) database.

So, to begin, the title and table-of-contents of Les Diverses Families Spirituelles de la France…

______________________________

______________________________

OF THE FRENCH ACADEMY

PRESIDENT OF THE LEAGUE OF PATRIOTS

THE VARIOUS SPIRITUAL FAMILIES OF FRANCE

PARIS

EMILE-PAUL FRÈRES, EDITORS

100, RUE DE FAIBOURG-SAINT-HONORÉ. 100

PLACE BEAUVAU

1917

______________________________

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapters. Pages.

I Our diversities disappear on August 4, 1914 1

II … And reappear in the army 9

III The Catholics 19

IV The Protestants 51

V The Israelites 67

VI The Socialists 90

VII The Traditionalists 137

VIII Catholics, Protestants, Socialists, all defending France, defend their particular faith 193

IX An already legendary night (Christmas 1914) 205

X Twenty-year-old soldiers devote themselves to creating a more beautiful France 215

XI This profound unanimity, we will continue to live it 259

Notes and Appendix 269

PRINTING CHAIX, RUE BERGERE, 20, PARIS – 842-1-17. (Lucre Lurilleux)

______________________________

NOTES AND APPENDIX

(12) NOTE FROM PAGE 74. – “I would like to know more about the war activity of the Israelites in Algeria than I could have obtained …”

Someone authorized to speak in their names writes [to] me:

“They serve, for the most part, in the Zouaves and were there (until lately) in the proportion of a quarter. They took part in the battles of Belgium, the Marne (particularly at Chambry), Soissons, Arras, Yser, Champagne, Verdun, the Somme, Dardanelles, Serbia. It is especially the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 8th Zouaves, constituted in Algeria, who set them at the beginning. The 45th division, formed at Oran of reservists and territorials, was the one that crossed Paris in the first days of September, and was immediately sent by Gallieni to the vicinity of Meaux, to carry the blow which was decisive.”

______________________________

(13) NOTE FROM PAGE 78. – “The documents which I possess on the moral elite of the Israelites only make known to me consciences which seem emptied of their religious tradition …”

On this subject, a young Jewish, industrial, Lorraine officer, who was the object of a beautiful citation by the order of the army, writes me an interesting letter which begins with these words: “I am a Jew, sincerely believing and attached to my religion …” I leave some fragments:

“Let us take as an example,” said the officer, “an Israelite of what is called the good bourgeoisie, that is, the second lieutenant who writes to you … I had a medium education (classical studies to Carnot, then beginning of right). My parents are from Alsace, and under Louis-Philippe, one of my grandparents was Mayor of Altkirch. For my part, I did my military service, like all the young people I knew, without much pleasure or enthusiasm, and only thought of the war when my father told me about his campaign of 1870.

Suddenly comes the period of tension in 1914, then mobilization. I would have liked you to see our joy, to we Jews who, according to you, sir, do not have real love of their country or have it only by gratitude for a country where they have not been martyred … I remember that Saturday night, when my parents accompanied me to Paris-Lyon-Méditerranée. My mother was crying and my father laughed with joy despite having tears in the corner of his eye. For my part, I give you my word of honor and [as a] soldier; I was happy without calculation, happy to fight for my country that I loved … All my friends to whom I said goodbye, without doubt that it was goodbye to me, had the joy at heart of the idea of taking over Alsace, of which we for the most part are native.

I insist on this instinctive sentiment of patriotism; I would like us to know each other better, we other Jews, who are not ashamed of our race and who do not use our fortune to offer hunts to people ruined by fragments. I believe you only see two kinds of Jews:

First of all, the little aristocracy, with enormous fortunes, and which is not very interesting (characterized by its platitudes toward the great names of Catholicism).

Then, there are the Polish Jews who clutter our country and who, to eat, do all the trades (the latter are only interesting by the misfortunes they have endured in Russia).

But there are also the believing Jews, sincere, profoundly fond of their country, not seeking to dazzle others by their fortune and their luxury of bad taste: in short, the good bourgeoisie. You believe too much that Jews are beings apart, who have a special mentality. Between the “Nucingen” and the “Gobseck”, there is something else.

I had a hard time at the front because during the first winter we were not yet used to this war of “moles” and in the Vosges (col de Sainte-Marie) we suffered a lot from the cold. For men, physical suffering alone counted; but as an officer I had painful days. This inaction weighed on me. The loneliness in our wooded mountains breeds melancholy, bad feelings; in short weariness. It was then that my faith intervened and saved me morally. I remembered the prayer I was making at night, before kissing my mother and who is very similar to your “Pater noster”. I prayed and the Lord supported me; gave me calm. Whenever I had a decision to make, I thought of Him and I was quiet.

At the moment of the attack itself, the duty imposes on you enough work so that one can think only of the orders received and the means to execute them for the best. But before! The half hour preceding the offensive attack or reconnaissance has a tragic grandeur. Every one, Catholic, Protestant, or Jew, collects himself, and the true believers recognize themselves in their calm, which at this moment can not be feigned.

I write to you in all sincerity. Whenever I saw that I had to go to death, I thought of “Him,” and my duty seemed natural, without merit. When I was buried, I thought myself wounded to death and my first thought was still for my God.

The Jewish religion is not made for the people, because it is not composed of small external practices, but only of the idea of God and the survival of the soul. That’s why there are few true believers.

It happened to me, wanting to gather me, to go to a church and I do not think I committed sacrilege.

This is my state of affairs, which I am simply exposing to you, feeling sympathy for you.”

(Letter from Second Lieutenant L., December 29, 1916.)

______________________________

On the same subject a letter signed by an important name in Parisian society:

I do not want to let you believe that the consciences of the Israelites who died for France with love “are emptied of their religious tradition”. However, I can only bring you “texts” by formally asking you to take them only as anonymous. By modesty first, and by justice also for unknown heroes, I desire that the name of my son be piously guarded by you without being published …

I regretfully conform to this desire; I will not mention the name of the hero, who held a high office; I limit myself to analyzing the small file that is communicated to me.

Aged 33, sergeant to the 360th Infantry Regiment, this Jewish soldier took part in the fighting of Reméreville, Crévic, Bois Saint-Paul, Velaine-sôus-Ainance, from August 25 to September 14, 1914. [Max Jean Francois Claude Levy] At this date, he writes to his parents a letter that will be the last:

Papa, adored mama. Thank you for your tender cards and letters that I receive very well, but in package. Last night those of August 31st and September 1st. You are, I am sure, an admirable nurse, but I will not need your care for this time. We are now held back for a long time from the line of fire where we have been since August 26, especially since September 2. I did not have an attack, not a scratch, and yet I felt almost sure, so much I had the powerful feeling of God’s protection that he granted me for all and by you my admirable parents. So that I had no merit in feeling no hesitation in throwing myself between bullets and shells; I saw them veer around me. I did not commit any act of valor, at all, I hasten to say it, I just went where I was told to go.

Three days later, having proposed to conduct a reconnaissance, he enters the village of Bezange-la-Grande. A young peasant advises him to “turn around”. He answers: “I am charged with a reconnaissance, one must go farther …”, and almost immediately he falls, hit in the head by an explosive bullet. He had said to his father on leaving him: “I will bring you back Lorraine, or I will stay there.” The inhabitants buried him and the mayor was able to send the parents the medal of piety found on their son; it bore the traditional inscription: “You shall love the LORD.” [This is a reference to the Shema Yisrael prayer, in Deuteronomy 6, Verses 4-5. The full text:

4) Hear, O Israel: the LORD our God, the LORD is one.

שְׁמַע, יִשְׂרָאֵל: יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ, יְהוָה אֶחָד.

5) And thou shalt love the LORD thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy might.

וְאָהַבְתָּ, אֵת יְהוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ, בְּכָל-לְבָבְךָ וּבְכָל-נַפְשְׁךָ, וּבְכָל-מְאֹדֶךָ.]

On the paper he had prepared before his departure and where he expressed his last wishes, he invoked the sacred word: He walked with God all the days of his life. Suddenly we no longer saw him because God had taken him.” [A reference to Chapter 5, Verse 24, in Genesis. The actual text: And Enoch walked with God, and he was not; for God took him. וַיִּתְהַלֵּךְ חֲנוֹךְ, אֶת-הָאֱלֹהִים; וְאֵינֶנּוּ, כִּי-לָקַח אֹתוֹ אֱלֹהִים.]

And again: “For myself, I know that my Redeemer lives and that He will raise me up from the earth, and that when my flesh is destroyed, I will see God. I will see Him with my eyes.” [A reference to Verses 25 through 27, in Chapter 19 of the Book of Job. The actual text:

25) But as for me, I know that my Redeemer liveth, and that He will witness at the last upon the dust;

וַאֲנִי יָדַעְתִּי, גֹּאֲלִי חָי; וְאַחֲרוֹן, עַל-עָפָר יָקוּם.

26) And when after my skin this is destroyed, then without my flesh shall I see God;

וְאַחַר עוֹרִי, נִקְּפוּ-זֹאת; וּמִבְּשָׂרִי, אֶחֱזֶה אֱלוֹהַּ.

27) Whom I, even I, shall see for myself, and mine eyes shall behold, and not another’s. My reins are consumed within me.]

אֲשֶׁר אֲנִי, אֶחֱזֶה-לִּי–וְעֵינַי רָאוּ וְלֹא-זָר: כָּלוּ כִלְיֹתַי בְּחֵקִי.]

[Perhaps Max Levy’s “medal of piety” referred to by Barrès’ was a Mezuzah in the form of an amulet…?]

Max Jean Francois Claude Levy

Sergent Major, 16063 / 16635, France, Armée de Terre, Infanterie, 360eme Regiment d’Infanterie, 22eme Compagnie

Sergent Major, 16063 / 16635, France, Armée de Terre, Infanterie, 360eme Regiment d’Infanterie, 22eme Compagnie

Killed by the enemy [Tué a l’ennemi] at Carency, Pas-de-Calais, France, May 9, 1915

Born August 9, 1887, 10eme Arrondissement, Paris, France

Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française, p. 56

Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française lists name as “Levy, Max”, and gives date and location as May 5, 1915, Villers-aux-Bois”

Buried at Necropole Nationale “Notre-Dame-de-Lorette”, Ablain-Saint-Nazaire, Pas-de-Calais, France – Tombe Individuelle, Carre 87, Rang 4, No. 17468

SGA burial record gives name as “Levy, Max”

______________________________

On Israel believing, still this document of the sacred union. M. Lancrenion, priest, medical aide-major in the 1st group of the 39th artillery, writes to the mother of the young Charles Halphen, lieutenant of the 39th artillery, fallen on the field of honor on May 15, 1915, a letter of which here is the end:

The friendship, linked by me with your son, has turned into respect and admiration for his heroic death. And I want to tell you too, the infinitely powerful and merciful God, in whom we all believe, though different from religion, in which your son believed (he told me), took from him, I hope, the right and loyal soul, who sacrificed himself for duty, and he took it for immortality … I prayed from the bottom of my heart yesterday, today, this God of mercy, to receive your son to him, and to gather you to him, when the time will come for an eternal and happy meeting … May this word of a minister of God not calm your pain, but bring you hope, support your courage, help you bear the sacrifice.

Charles Nathan Halphen

Lieutenant, 65, France, Armée de Terre, Artillerie

Lieutenant, 65, France, Armée de Terre, Artillerie

39eme Regiment d’Artillerie de Campagne

Killed by the enemy [Tué a l’ennemi], at Neuville-Saint-Vaast, Pas-de-Calais, France, May 15, 1915

Mr. Georges Halpen (father)

Born December 3, 1885, 17eme Arrondissement, Paris, France

l’Univers Israélite 10/8/15, 1/26/17

The Jewish Chronicle 7/30/15

Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française, p. 41

Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française gives name as “Halphen, Charles” and date as May 12, 1915

l’Univers Israélite: “Professeur au college Chaptal; Cite a l’ordre de l’armee; Il etait fils de feu Georges Halphen, membre de l’Academie des sciences”

Buried at Cimetiere Militaire “Ecoivres Milit. Cemetery”, Ecoivres – Mount Saint Eloi, Pas-de-Calais, France – Tombe Individuelle, Rang 23, No. 731, 65

______________________________

(14) NOTE FROM PAGE 92. – I am told: “You have seen exceptional Israelites, newly arrived among us or great intellectuals”, and I am given to read the correspondence of Captain Raoul Bloch, killed on May 12, 1916 before Verdun, who belonged to the business world. His letters, in a firm tone, exude the most salutary patriotic and family feeling.

Raoul Bloch

Capitaine, France, Armée de Terre, Infanterie

Capitaine, France, Armée de Terre, Infanterie

306eme Regiment d’Infanterie

Killed [Tué], May 12, 1916, at Mort Homme, Fromerville, Meuse, France

Born April 11, 1872, Auxerre, Yonne, France

Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française 1921, p. 17

American Jewish Yearbook V 21, p. 38

Place of burial unknown (None?…)

Aged forty, assigned to the service of the [reserves], he asks to go into active [service]. “I am anxiously waiting to do my duty as I desire and understand it; as French and Jew, I have to do it twice. The country is at this moment in need of all its men valid for defense, arms in hand; – I am in a service that can be done very well with men of age and less nimble, my duty is to offer my services elsewhere …»

On the 6th of January, 1915, he sends to his wife this page full of the earthly piety of an Alsatian Israelite:

With what joy I will go to the side of Alsace and what memories by penetrating into uniform in this country of our dreams! Our poor fathers would flinch in their graves! Finally, the “revenge” of which they spoke so much, whose heart overflowed! and my brave brother, my old under the hood, and in what tragic moments! with what pleasure I will avenge him and Robert my brother too soon disappeared! What a note to pay the Bandits and how I will be fierce creditor!

Tell them all, brothers and sisters, that never can our hearts have vibrated so much in unison and have so intensely communicated. I often think of all those who surround you at this moment with such tender affection, and help you to bear valiantly the heavy contribution of the country that I imposed on you as well as myself. To be one of those who have contributed directly to your home birthplace will be for me a sweet joy and a complement to our life so united and so tender. What a beautiful anniversary of our twenty years of cleaning, the “rue de la Mésange” once again French! what more beautiful gift can I dream to bring you! And Lauterbourg, Niederbronn, Bionville, all in our three colors! You must understand why I wanted and had to leave, the whole family tradition is not with me? To be able to take you and our darlings to Alsace-Lorraine and tell them: Papa has helped in the measure of his strength to return these two beautiful countries to France, what a better reward for me?

__________________________

______________________________

– .ת. נ. צ. ב. ה –

תהא

נפשו

צרורה

בצרור

החיים

May 9, 1915 – Max Jean Francois Claude Levy

The books Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française (in combination with the SGA database) and Die Jüdischen Gefallenen Des Deutschen Heeres, Deutschen Marine Und Der Deutschen Schutztruppen 1914-1918 – Ein Gedenkbuch, reveal the names of approximately 90 French Jewish soldiers, and 27 German Jewish soldiers – killed in action or died of wounds – for the above date.

May 15, 1915 – Charles Nathan Halphen

Freyberg, France, Seine-Maritime; Rouen; l’Hopital (“Partie a Remplir par le Corps” card could not be found or identified in SGA database; name from Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française

Koskach, Isaac, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Algérie), 16850, Belgique; Het Sas

Midowitch, Kiel, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Russie), 20493, Pas-de-Calais; Berthonval

Zerbib, Messim Emile, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Algérie), 10859, Pas-de-Calais; Roclincourt

The names of Midowitch and Zerbib do not appear in Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française.

May 12, 1916 – Raoul Bloch

Bernheim, Lucien Germain Edouard, Aspirant, France, 6473, Meuse; Vauquois

Darmon, Mimoun, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Algérie), 17288, Meuse

Walter, Stephan, Soldat de 2eme Classe, France (Pologne – Lodz), Meuse; Thierville; 1600 m a l’ouest de

Walter’s name does not appear in Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française.

______________________________

______________________________

NOTES ET APPENDICE

(12) NOTE DE LA PAGE 74. — «J’aimerais avoir sur l’activité guerrière des Israélites d’Algérie des précisions que je n’ai pu me procurer…»

Quelqu’un d’autorisé à parler en leurs noms m’écrit:

«Ils servent, pour la plupart, dans les zouaves et s’y trouvaient (jusqu’à ces derniers temps) dans la proportion d’un quart. Ils ont pris part aux combats de Belgique, de la Marne (particulièrement à Chambry), devant Soissons, à Arras, sur l’Yser, en Champagne, sous Verdun, dans la Somme, aux Dardanelles, en Serbie. Ce sont surtout les 1er, 2e, 3e, 4e et 8e zouaves, constitués en Algérie, qui les ont encadrés à l’origine. La 45e division, formée à Oran de réservistes et de territoriaux, est celle qui a traversé Paris dans les premiers jours de septembre et qui a tout de suite été expédiée par Galliéni dans les environs de Meaux, pour y porter le coup qui fut décisif.»

(13) NOTE DE LA PAGE 78. — « Les documents que je possède sur l’élite morale des israélites ne me font connaître que des consciences qui paraissent vidées de leur tradition religieuse…»

Là-dessus, un jeune officier israélite, industriel lorrain, qui a été l’objet d’une belle citation à l’ordre de l’armée, m’écrit une lettre intéressante qui commence par ces mots: «Je suis juif, sincèrement croyant et attaché à ma religion…» J’en détache quelques fragments:

«Prenons comme exemple, me dit cet officier, un israélite de ce que l’on appelle la bonne bourgeoisie, c’est-à-dire le sous-lieutenant qui vous écrit… J’ai eu une instruction moyenne (études classiques à Carnot, puis commencement de droit). Mes parents sont originaires d’Alsace, et, sous Louis-Philippe, un de mes grands-parents était maire d’Altkirch. Pour ma part, j’ai fait mon service militaire, comme tous les jeunes gens que je connaissais, sans grand plaisir ni enthousiasme, et ne pensais à la guerre que lorsque mon père me racontait sa campagne de 1870.

»Tout à coup arrive en 1914 la période de tension, puis la mobilisation. J’aurais voulu que vous puissiez voir notre joie, à nous juifs qui, d’après vous, Monsieur, n’ont pas l’amour réel de leur patrie ou ne l’ont que par reconnaissance pour un pays où ils n’ont pas été martyrisés… Je me souviens de ce samedi soir, lorsque mes parents m’ont accompagné au Paris-Lyon-Méditerranée. Ma mère pleurait et mon père riait de joie en ayant malgré tout use larme au coin de l’œil. Pour ma part, je vous en donne ma parole d’honneur et de soldat, j’étais heureux sans calcul, heureux de me battre pour mon pays que j’aimais… Tous mes amis à qui j’ai dit au revoir, sans me douter que c’était un adieu, avaient la joie au cœur à l’idée de reprendre cette Alsace dont nous sommes pour la plupart originaires.

»J’insiste sur ce sentiment instinctif de patriotisme; je voudrais que I’on nous connaisse mieux, nous autre juifs, qui n’avons pas honte de notre race et qui n’usons pas de notre fortune pour offrir de chasses aux gens ruinés à particule. Je crois que vous ne voyez que deux sortes de juifs :

»D’abord la petite aristocratie, aux fortunes énormes, et qui est peu intéressante (caractérisée par sa platitude envers les grands noms du catholicisme).

»Ensuite, les juifs polonais qui encombrent notre pays et qui, pour manger, font tous les métiers (ces derniers ne sont intéressants que par les malheurs qu’ils ont endurés en Russie).

»Mais il y a aussi les juifs croyants, sincères, aimant profondément leur pays, ne cherchant pas à éblouir les autres par leur fortune et leur luxe de mauvais goût: bref, la bonne bourgeoisie. Vous croyez trop que les juifs sont des êtres à part, qui ont une mentalité spéciale. Entre le «Nucingen» et le «Gobseck», il y a autre chose.

»J’ai passé au front de durs moments, car pendant le premier hiver nous n’avions pas encore l’habitude de cette guerre de «taupes» et dans les Vosges (col de Sainte-Marie) nous souffrions beaucoup du froid. Pour les hommes, la souffrance physique seule comptait; mais, comme officier, j’avais de pénibles journées. Cette inaction me pesait. La solitude dans nos montagnes boisées engendre la mélancolie, les mauvais sentiments, bref la lassitude. C’est alors que ma foi est intervenue et m’a sauvé moralement. Je me suis souvenu de la prière que je faisais tout petit, le soir avant d’embrasser ma maman et qui ressemble beaucoup à votre «Pater noster». J’ai prié et le Seigneur m’a soutenu, m’a donné le calme. Chaque fois que j’avais une décision à prendre, je pensais à Lui et j’étais tranquille.

»Au moment de l’attaque même, le devoir vous impose suffisamment de travail pour que l’on ne puisse penser qu’aux ordres reçus et aux moyens de les exécuter pour le mieux. Mais avant! La demi-heure qui précède l’attaque ou la reconnaissance offensive, possède une grandeur tragique. Chacun, catholique, protestant ou juif se recueille, et les véritables croyants se reconnaissent à leur calme, qui, à ce moment, ne peut être feint.

»Je vous écris en toute sincérité. Chaque fois que je voyais qu’il fallait aller à la mort, je pensais à «Lui», et mon devoir m’apparaissait naturel, sans mérite. Lorsque j’ai été enseveli, je me suis cru blessé à mort el ma première pensée a été encore pour mon Dieu.

»La religion juive n’est pas faite pour le peuple, car elle n’est pas composée de petites pratiques extérieures, mais uniquement de l’idée de Dieu et de la survie de l’âime. C’est pourquoi il y a peu de véritables croyants.

»Il m’est arrivé, voulant me recueillir, d’aller m’agenouiller dans une église et je ne crois pas avoir commis un sacrilège.

»Voilà mon état dame que je vous expose simplement, sentant chez vous une sympathie.»

(Lettre du sous-lieutenant L., 29 décembre 1916.)

Sur le même sujet une lettre signée d’un nom important dans la société parisienne:

Je ne voudrais pas vous laisser croire que les consciences des Israélites morts pour la France avec amour «sont vidées de leur tradition religieuse». Je ne peux cependant vous apporter des «textes» qu’en vous demandant formellement de ne les prendre que comme anonymes. Par modestie d’abord, et par justice aussi pour les héros inconnus, je désire que le nom de mon fils soit par vous pieusement gardé sans être publié …

Je me conforme à regret à cette volonté; je tairai le nom du héros, qui occupait une haute charge; je me borne à analyser le petit dossier que l’on me communique.

Agé de 33 ans, sergent au 360e régiment d’infanterie, ce soldat israélite a pris part aux combats de Réméreville, Crévic, Bois Saint-Paul, Velaine-sôus-Ainance, du 25 août au 14 septembre 1914. A cette date, il écrit à ses parents une lettre qui va être la dernière:

Papa, maman adorés. Merci de vos tendres cartes et lettres que je reçois très bien, mais en paquet. Hier soir celles du 31 août el du 1er septembre. Vous êtes, j’en suis sur, une infirmière admirable, mais je n’aurai pas pour celle fois besoin de vos soins. Nous sommes aujourd’hui retenus en arrière pour longtemps de la ligne de feu où nous sommes depuis le 26 août, surtout depuis le 2 septembre. Je n’ai pas eu une atteinte, pas une égratignure, et pourtant je me sentais presque sûr, tellement j’avais sur moi la sensation puissante de le protection de Dieu qu’il m’accorda pour tous et par vous mes admirables parents. De sorte que je n’ai eu aucun mérite à n’éprouver aucune hésitation à me jeter entre les balles et les obus; je les voyais dévier autour de moi. Je n’ai d’ailleurs commis aucun acte de valeur, du tout, je m’empresse de le dire, je me suis contenté d’aller là où l’on me disait d’aller.

Trois jours plus tard, s’étant proposé pour conduire une reconnaissance, il pénètre dans le village de Bezange-la-Grande. Un jeune paysan lui conseille «de faire demi-tour». Il répond: «Je suis chargé d’une reconnaissance, il faut aller plus loin…», et presque aussitôt il tombe frappé à la tête d’une balle explosible. Il avait dit à son père en le quittant: «La Lorraine, je vous la rapporterai ou j’y resterai.» Les habitants l’ensevelirent et le maire a pu faire parvenir aux parents la médaille de piété trouvée sur leur fils; elle portait l’inscription traditionnelle: «Tu aimeras l’Éternel.» Sur le papier qu’il avait préparé avant son départ et où il exprimait ses dernières volontés, il invoquait la parole sacrée: Il chemina avec Dieu tous les jours de sa vie. Tout à coup on ne le vit plus parce que Dieu l’avait pris.» Et encore: «Pour moi, je sais que mon Rédempteur est vivant et qu’il me ressuscitera de la terre, et que lorsque ma chair aura été détruite, je verrai Dieu. Je le verrai de mes yeux.».

Sur Israël croyant, encore ce document d’union sacrée. M. Lancrenion, prêtre, médecin aide-major au 1er groupe du 39e d’artillerie, écrit à la mère du jeune Charles Halphen, lieutenant au 39e d’artillerie, tombé au champ d’honneur le 15 mai 1915, une lettre dont voici la fin:

L’amitié, liée par moi avec votre fils, s’est transformée en respect et en admiration devant sa mort héroïque. Et je veux vous le dire aussi, le Dieu infiniment puissant et miséricordieux, dans lequel nous croyons tous, quoique différents de religion, dans lequel votre fils croyait (il me l’a dit), a pris auprès de lui, je l’espère, l’âme droite et loyale, qui s’est sacrifiée pour le devoir, el il l’a prise pour l’immortalité … J’ai prié du fond de mon cœur hier, aujourd’hui, ce Dieu de miséricorde, de recevoir votre fils auprès de lui, et de vous réunir à lui, quand le temps sera venu pour une réunion éternelle et heureuse… Puisse cette parole d’un ministre de Dieu, non pas calmer votre douleur, mais vous apporter l’espérance, soutenir votre courage, vous aider à supporter la sacrifice.

(14) NOTE DE LA PAGE 92. — On me dit: «Vous avez fait voir des israélites d’exception, nouvellement venus parmi nous ou bien grands intellectuels», et l’on me donne à lire la correspondance du capitaine Raoul Bloch, tué le 12 mai 1916 devant Verdun, qui appartenait au monde des affaires. Ses lettres, d’un ton ferme, respirent le plus salubre sentiment patriotique et familial.

Agé de quarante ans, affecté au service des étapes, il demande à passer dans l’active. «J’attends impatiemment de faire mon devoir comme je le désire et le comprends; comme Français et Juif, je dois le faire doublement. Il faut au pays en ce moment tous ses hommes valides pour la défense les armes à la main; — je suis dans un service qui peut se faire fort bien avec des hommes d’âge et moins ingambes, mon devoir est d’offrir mes services ailleurs…»

En date du 6 janvier 1915, il envoie à sa femme celte page toute pleine de la piété terrienne d’un Israélite alsacien :

Avec quelle joie je m’en irai du côté de l’Alsace et quels souvenirs en pénétrant en uniforme dans ce pays de nos rêves! Nos pauvres papas en tressailleraient dans leurs tombes! Enfin, la «revanche» dont ils ont tant parlé, dont leur cœur débordait! et mon brave frère, mon ancien sous la capote, et dans quels tragiques moments ! avec quel plaisir je le vengerai ainsi que Robert mon frère trop tôt disparu! Quelle note à faire payer aux Bandits et combien je serai féroce créancier!

Dis-leur à tous, aux frères et sœurs, que jamais peut être nos cœurs n’ont tant vibré à l’unisson et n’ont communie d’une façon aussi intense. Je pense souvent à tous ceux qui t’entourent en ce moment d’une affection si tendre et t’aident à supporter vaillamment la lourde contribution du pays que je t’ai imposée ainsi qu’a moimème. Être de ceux qui auront contribué directement à te rendre ton berceau natal sera pour moi une bien douce joie et comme un complément à notre vie si unie et si tendre. Quel bel anniversaire de nos vingt ans de ménage, la «rue de la Mésange» redevenue française ! quel plus beau cadeau pourrai-je rêver de t’apporter! Et Lauterbourg, Niederbronn, Bionville, tout cela sous nos trois couleurs! Tu dois comprendre pourquoi je voulais et devais partir, toute la tradition familiale n’est-elle pas avec moi? Pouvoir emmener toi et nos chéris en AIsace-Lorraine et leur dire: Papa a aidé dans la mesure de ses forces à rendre ces deux beaux pays à la France, quelle plus belle récompense pour moi?

References and Suggested Readings

Barrès, Maurice, Les diverses familles spirituelles de la France, Paris, Émile-Paul frères, Paris, France, 1917, at Archive.org

Maurice Barrès, at Wikipedia

Maurice Barrès, at For and Against Dreyfus

Maurice Barrès, at Radical Right Analysis

Englund, Steven, An Affair As We Don’t Know It (Book Review of An Officer and A Spy, by Robert Harris), at Jewish Review of Books, Spring, 2015

Die Jüdischen Gefallenen Des Deutschen Heeres, Deutschen Marine Und Der Deutschen Schutztruppen 1914-1918 – Ein Gedenkbuch, Reichsbund Jüdischer Frontsoldaten, Forward by Dr. Leo Löwenstein, Berlin, Germany, 1932

Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française (Israelites [Jews] in the French Army), Angers, 1921 – Avant-Propos de la Deuxième Épreuve [Forward to the Second Edition], Albert Manuel, Paris, Juillet, 1921 – (Réédité par le Cercle de Généalogie juive [Reissued by the Circle for Jewish Genealogy], Paris, 2000)

“Died for France in the First World War” “PARTIE À REMPLIR PAR LE CORPS (‘PART TO BE COMPLETED BY THE CORPS’)” forms, at Morts pour la France de la Première Guerre mondiale

French Military War Graves, at Sépultures de Guerre

Mechon Mamre, at Mechon-Mamre.org