Louis Falstein’s literary oeuvre commenced at least five years – and probably more – before the 1950 publication of Face of a Hero, based on this very brief news item from Molto Buono (Italian for “Very Good”), the unofficial wartime newspaper of (first) the 723rd Bomb Squadron, and (subsequently) the 450th Bomb Group. The article specifically mentions that Louis was an editor of New Writers and Midwest magazines, and was solicited to write articles for Free World, a publication affiliated with the United Nations.

The article confirms Lou’s service as a combat airman in the 723rd Bomb Squadron, the article’s publication date, February 3, 1945, placing an approximate time-frame on the period of Lou’s service with the Cottontails: The latter part of 1944 through early 1945.

Molto Buono, February 3, 1945

723rd Notes

Did you know that S/Sgt Lou Falstein, who very recently wound up his missions and took the long but wonderful voyage home, is a professional writer, a former editor of “New Writers” and “Midwest” Magazines? Just before leaving, Lou was asked to write a series of monthly articles on the development of democracy in Italy for “Free World,” an outstanding international publication, dealing with United Nations economic and political problems.

________________________________________

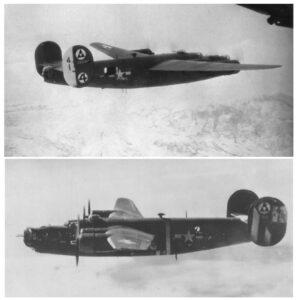

To give an appreciation of the technical aspects of being a B-24 Liberator tail gunner, this video, “Consolidated B-24 Tour – Subscriber’s Request! – Part 1“, at Kermit Weeks’ YouTube channel, shows the interior of the rear fuselage of a B-24J Liberator, with particular emphasis on the interior of Louis’ crew station, the Emerson tail turret. The aircraft is “Joe”, 44-44272.

________________________________________

It seems that Louis’ first published writing appeared in a periodical of great significance: The New Republic. From August of 1945 through January of 1946, he authored five articles for that magazine, three of which were based upon his experiences in the Armed forces, the other two reporting on the development of the atomic bomb. The commonality of the articles is their very “human” approach to their subject matter: they emphasize neither Lou’s military experiences per se, nor the purely technological and scientific aspects of the extraction and refinement of uranium for use in atomic weapons. Instead, they focus on Lou’s impressions of civilian refugees, fellow soldiers, and scientists and their families, paying particular attention to language, speech, and emotion. However, the final two articles are somewhat analytical, one covering moral and political controversies arising from the use of atomic weapons, and, the other entirely straightforward discussion of veterans’ organizations in the post-WW II United States.

These are the article titles and their publication dates:

“From a Flier’s Notebook” – August 20, 1945

“You’re on Your Own” – October 8, 1945

“Oak Ridge: Secret City” – November 12, 1945

“The Men Who Made the A-Bomb” – November 26, 1945

“Veterans Welcome” – January 28, 1946

Full transcripts of all five articles are given below, with each article “headed” by quotes – in dark red, like this – that I think exemplify or highlight the article’s central point. The two articles about the Oak Ridge National Laboratory are accompanied by images of cartoons (one from P.M., the other from the Daily Mail) that actually appeared in those pieces.

Of special note – for the purpose of this series of posts – is Lou’s very first article: “From a Flier’s Notebook”. Note that in the first paragraph Lou mentions “our crew”, the only non-fiction reference to his fellow crew members – whoever they were – that I’ve found. And, in light of the statement, “Today we find ourselves in a luxurious palace. We’re on a high hill, and below our rocky cliffs flows the bluest of seas, so blue it hurts your eyes; its waters so clear you can see many fathoms down from your window,” was the un-named location of their “luxurious rest” Capri, or, Naples?

Of much greater import in terms of Face of a Hero is Lou’s detailed and moving account of his interactions and conversation with Yugoslavian refugees, both partisans and civilians, at a nearby rest camp, the article concluding upon his crew’s encounter with Jewish refugees from Yugoslavia, Austria, and Poland, at a “refugee colony on the coast.” Both of these encounters would be the basis a very lengthy passage in Lou’s then-future novel.

There, Sergeant Ben Isaacs feels an intense and immediate sense of identification – if not empathy – with these people, his awareness of this shared history giving rise to memories of escaping the Ukraine and reaching America in the wake of the Russian Civil War. And yet, even with closeness, there is distance: He comes to the realization that the trajectory of his life – the passage of time, and, his years in America, as an American – have created a near-unbridgeable gulf between himself and the people who in both symbolism and reality, embody his past.

But, that’s for later.

Here are the articles:

August 20, 1945 – “From a Flier’s Notebook“

October 8, 1945 – “You’re On Your Own“

November 12, 1945 – “Oak Ridge: Secret City“

November 26, 1945 – “The Men Who Made the A-Bomb“

January 28, 1946 – “Veterans Welcome“

________________________________________

From a Flier’s Notebook

The New Republic

August 20, 1945

Today we find ourselves in a luxurious palace.

We’re on a high hill,

and below our rocky cliffs flows the bluest of seas,

so blue it hurts your eyes;

its waters so clear you can see many fathoms down from your window.

We are here for a three-day rest.

Combat fatigue.

There is a Yugoslav rest camp nearby….

**********

In the shoe-repair-shop were two elderly people – Viennese.

The woman, still showing signs of former good living, looked up and smiled.

“A guest,” she said, and embraced me.

Vienna.

Had I ever heard of Vienna?

Yes, I said, I’d had occasion to hear of it…

“Ah, you’ve been bombing it!” she exclaimed.

“Goot! Goot! I have a great house there, but I don’t care.

Bomb it.

Hitler is there.

Destroy it!

Destroy the evil genie!”

America – would I tell them something about America, the outside world?

She held onto me: “Please come to our casa, if only for an hour…”

They live on this rocky, craggy coast, far away from their native lands.

They work and pray in their little synagogue.

They are very dexterous with their hands and are self-supporting.

But they have no place to go.

They are strangers here and strangers in their homelands.

Some of them talk of Palestine, of America.

But most of them live with nothing to look forward to.

The manager saw us to the road.

He shook my hand and said:

“Please come back.

We are apart from the world…

Shalom (Peace be with you).”

IN WAR things change very quickly from the sublime to the ridiculous, and vice versa. Yesterday our crew was in very Spartan surroundings eating C-rations and sleeping on the hard canvas bunks. Today we find ourselves in a luxurious palace. We’re on a high hill, and below our rocky cliffs flows the bluest of seas, so blue it hurts your eyes; its waters so clear you can see many fathoms down from your window. We are here for a three-day rest. Combat fatigue.

There is a Yugoslav rest camp nearby, and in the beautiful village below our palace I met several Yugos at the well. Many of them wear uniforms, British style, and all have Partisan caps, even babes in arms. We started a conversation with a couple, of lads and found that we could understand one another quite well. They invited us to an affair which was to take place that evening. As we talked, a fierce mustachioed giant came over. A Yugo M.P. He listened to our talk, nodded approvingly and finally said in – English: “You come tonight to party, h-okay. H-eight o’clock, h-okay.” And he put his huge paw gently on my shoulder and concluded: “American aviaticheri very good, sure.”

The show took place in a monastery. The program consisted of short sketches – crude, agitational, but good front-line stuff. The poetry is on a high level. These people sing well and are impressive even to those who do not understand them. And they sing at the slightest provocation. The blind, emaciated accordionist would strike up a tune, and the whole assemblage of men, women and children would join in lustily. Then someone would shout in their language: “Death to Fascism, Freedom to the People!” and there would be an echo. They have a fine, proud, dignified bearing. They are poor, but offer you cigarettes. British. (You prevail upon them to take your American smokes. They accept, but reluctantly.) The children have mature faces. They do not beg or accept candy like many of the little Italians who ask for “chungum…chocolat…caramel…” They follow the sketches intently. Some of the twelve-year-olds have seen action in battle. The women are big, some quite attractive; they carry rifles, like the men.

Blaj Bralle, the blind Dalmatian, plays the accordion like a master. I met him in a cool wine cellar. He agreed to share my bottle of wine if he could reciprocate. “I’ll play for you,” he said. He played and sang in a high passionate tenor voice and drank for three hours. While Blaj and I were drinking, the giant mustachioed M.P. lumbered in. He dented my back with his huge paw and said he was very happy to see me, but he could not stay; he was on duty. Very sorry. But he would have just one sip. A quick one. He tossed off one glass, wiped his mustaches and said, “I go now.” I asked him to have another. “H-okay.” He drained another glass. “Good!” He said he sure missed the wine when he was imprisoned by the Germans for three full years. Then he excused himself, said duty called; he would have just one more drink. He told me how he’d starved, how the Nazis tied his hands over his head for days, how they shot people. He showed me an old copy of Stars and Stripes which carried his fierce mustache and an article detailing his experiences as a Partisan and prisoner of war. We killed the bottle, and he finally left, saying: “H-okay, h-okay, I’ll see you…”

It’s been a long time, and I’ve flown many missions. Back at the rest camp facing the blue sea. I fell in love with this spot on my first visit here two months ago: The warm sun and the beach are far away from the droning planes and early alerts. The grim war-life is erased from my mind for a few brief days.

I cannot find my old friends among the Yugoslavs here. A young lad, Dmitri, promised to take me to another accordionist who might have word of Blaj. Dmitri is fifteen, a dignified, taciturn peasant boy. He is a veteran guerrilla, recovering from wounds received in action. He wears a Partisan cap with five-point-star, but no shoes. We went to the “home” of Professor Nikita. A barren, cavernous room with a mattress on the stone floor. Two broken chairs. Nothing else.

Professor Nikita is also blind. Blaj Bralle is no longer here, he said. He is sick with tuberculosis and has been taken away. (These people have so little, so tragically little, to eat.) “I will oblige you with some accordion playing.”

The accordionist and I drank. His wife poured the wined with delicate hand like a hostess accustomed to gracious manners. I sat on the floor, but she refused to sit on the chair, insisting that I take it.

I had one cigar in my pocket, our week’s ration. I offered it to Nikita. He refused, but finally took it. He fondled the cellophane wrapper for a long time. Then he undid it ceremoniously, mumbling: “Ah, my dear friend! What a treat! It’s been so many years… But you are depriving yourself- “

“Smoke it, please,” I said.

“Surely, surely,” Nikita exclaimed, his strong, stony face beaming. “Mama, we’ll proceed to smoke this wonderful thing. Mama, smell it.” We lit the cigar. “Mama, come here. The sheer fragrance of it. Now I’m happy. I shall smoke it slowly and I shall play some songs for our dear comrade.”

As we played and sang, a young bespectacled Italian priest in dark brown cassock and his boy assistant entered. The hostess gave him her seat. They spoke Italian. The priest asked for some operatic airs and sang in a strong tenor voice. His face grew red and sweaty. My Luckies made the rounds. The hostess stood and smiled graciously, wanting her guests to be happy.

How poor these people are! But what dignity! “Our land is afire!” the accordion player said. “It is a beautiful land, but the incendiaries have put it to the torch. You can do the same to them. You and your mighty airplanes.”

The other night the Red Cross gave a party for us and Invited Dmitri. He came reluctantly. He has no shoes – and he doesn’t like to sit at dances. As we walked to the hotel, we met several friends of Dmitri’s and I invited them too. There was one husky girl, her left hand in a cast. Her name was Zinka. She is of peasant origin, wears a Partisan cap and trousers and there are three battle stars on her jacket. She has a peasant’s suspicion of city folk, of strangers, of Americans, too. She spoke very little. Dmitri told me that she had been a commander, of three hundred Partisans, with a legendary reputation for heroism and leadership. Her husband was killed at her side. She doesn’t laugh much nor smile. Her hatred is grim, but the children here, the many Yugoslav orphans, love her. She is very tender to them. We danced a waltz together. “I like these,” she said. “When there was music at home, we danced much.” I brought Zinka some punch and cake. Later in the evening she offered me some. “Take it,” she said. “But I’m full,” I told her. “You brought me some before,” Zinka retorted. “Now you will share mine.” She hails from the mountains and her dialect is not easy for me to understand, but we managed. She has killed many Germans. “You have too?” she asked. “Many?” I said I didn’t know how many. “But you kill them. That is what matters. That makes us brothers-in-arms.”

Yesterday we played Santa Claus to a group of Yugoslav children. A truckload of us took off for a coastal town where the orphans are housed. We carried several cartons of candy with us.

In an improvised hospital with cold, drab rooms were little tots, all feverish eyes in dry, white faces. The English Red Cross worker, named Mercy, led us among the children. They knew instinctively the meaning of a toy: a teddy bear or a clumsy dog made of olive drab. But candy – few had ever seen it. One youngster reluctantly accepted the bar I gave him. He gazed at it blankly, no reaction on his face. We removed the cellophane wrapper and suggested that he taste the candy. He did, hesitantly. Finally he realized that candy is to be eaten.

The older children, aged nine or ten, understood the occasion. They lined up solemnly, not like our kids yelling with joy and anticipation. They did not reach out. But as we made the rounds, each one upon taking the candy said quietly: “Chvala (Thank you).”

In the evening a bonfire was built in the village square. The youngsters marched in, singing as usual, and sat around the fire. A silver-bearded old guerrilla who looked like a professor, played Santa Claus. He wore a big white robe, and a Partisan cap. Before passing out the toys and candy, Santa Claus made a brief speech. He told the children of the gifts brought them by their allies; gifts which they must gladly accept, some day to be repaid. He said it was necessary to move up this Christmas celebration because they were all going back to Yugoslavia where great tasks awaited them and their leader, Tito. The children cheered Tito, the Allies and Santa Claus.

Earlier in the afternoon we had visited a Jewish refugee colony on the coast. Here were Yugoslav, Austrian and a few Polish Jews. In a huge villa, once inhabited by rich fascists, these homeless people have set up workshops. They make bedsprings of telephone wires, as well as clothes, toys and shoes. They have access to discarded materials only. Yet their work is superb.

The general manager, with a Hitler mustache, showed us ground. “Out of 70,000 Jews once inhabiting Yugoslavia, only 6,000 are left,” he said. “And they are alive today because they are with the Partisans.” He was once a big businessman in Belgrade. Now he has nothing, expects nothing.

An old nearsighted Austrian Jew was wiring bedsprings in a dark room. There is no electricity. He asked me eagerly from where I came. “New York,” I told him. “Ah, New York!” he exclaimed. “Do you know the Schumans on Eighty-sixth Street? Please see them. Tell them of my plight… Please…”

In the shoe-repair-shop were two elderly people – Viennese. The woman, still showing signs of former good living, looked up and smiled. “A guest,” she said, and embraced me. Vienna. Had I ever heard of Vienna? Yes, I said, I’d had occasion to hear of it… “Ah, you’ve been bombing it!” she exclaimed. “Goot! Goot! I have a great house there, but I don’t care. Bomb it. Hitler is there. Destroy it! Destroy the evil genie!” America – would I tell them something about America, the outside world? She held onto me: “Please come to our casa, if only for an hour…”

They live on this rocky, craggy coast, far away from their native lands. They work and pray in their little synagogue. They are very dexterous with their hands and are self-supporting. But they have no place to go. They are strangers here and strangers in their homelands. Some of them talk of Palestine, of America. But most of them live with nothing to look forward to.

The manager saw us to the road. He shook my hand and said: “Please come back. We are apart from the world… Shalom (Peace be with you).”

SERGEANT LOUIS FALSTEIN

________________________________________

You’re on Your Own

The New Republic

October 8, 1945

There was no hell-raising in the barracks.

If there was any joy in our hearts, it was an inner joy.

We asked each other, somewhat sheepishly: “What do you intend to do for a living?”

**********

A private from New York, said:

“I can just see myself …

riding on the Eighth Avenue subway. …

All of a sudden I feel inside my shirt and discover I ain’t got my dog tags on …

I’m scared stiff an MP will catch me and I’ll get restricted.

“So I pull the emergency cord for the train to stop, and I run home for my dog tags. …

I can just see it.”

**********

For most of us it was the last night in the Army.

No doubt some felt a sentimental twinge in parting with a life so thoroughly lived

that its imprints would linger forever in one’s being.

It had not all been blood and sweat,

and even for those of us who had seen the burial of our comrades,

there had also been many moments of joy and warmth and common feeling of accomplishment.

And some of us spoke freely of joining the Reserve

and even reenlisting if we could not make a go of it in civilian life.

An infantry sergeant who had been through the hell of Anzio, said:

“For months now I’ve been sweating it out, looking forward to this.

Now that it’s come, I’m afraid.”

ELEVEN of us boarded the train in Chicago with orders to report at Fort Dix for, separation from the Army. We were a jubilant bunch of high-point men. It was our last train ride as GIs, and one we had been looking forward to for many years. We found our Pullman compartments but did not stay in them long. A feeling of great excitement and anticipation imbued each of us. The club-car was crowded; the washrooms, platforms and passageways were loud with talk and handshakes and back-slapping. There were hundreds of us riding the Freedom Train. In the dining-car we presented our government meal tickets and received the inevitable stew, but this time we did not resent it. For this was the last time. We were lavish in our tips. We called each other Mister.

The following morning we arrived at Fort Dix. At the gate we saw a GI coming in our direction, a barracks bag slung over his shoulder and a shiny, new cloth discharge emblem on his shirt. “How long does it take to get a discharge?” Joe Myron, a waist gunner who had flown with the 15th Air Force, asked. “Forty-eight hours,” the brand-new civilian replied.

“That’s too long for me,” Joe said as we moved on.

Forty-eight hours isn’t a long time after years in the Army. But even the most stolid and patient among us considered one day’s delay in our discharge as an irreparable blow to the progress of mankind. We were in a hurry. And here, finally, was the opportunity. No golden promises awaited us outside, and many looked with fear and uncertainty to the future. But now, getting out was the important thing.

We were issued bedding, assigned to barracks in the Casual Area, and told to listen to the public address system and read the bulletin board. “Your names will appear on the roster tomorrow,” the non-com from Operations said indifferently, “Most of you will get on it tomorrow, but some won’t. And if you don’t, you’ll know your service record is not in order. And please don’t come to Operations and ask us why you didn’t make the roster. We just work here – 24 hours a day.”

In the barracks we found three men who said they’d been there four days already. One of the men, tall, flabby, with six overseas bars on his shirt-sleeve, talked with the bitterness and cynicism one finds so frequently in the Army among those who feel trapped. “Four days I been here!” he said. “I ain’t no dischargee. If you ask me, I’m a retainee.”

Twice daily, rosters were posted along a large wall in front of a modest little building called Operations. These rosters contained the names of men and the schedule for their discharge processing. The most prevalent question among us was: “Did you get on a roster?” Of our original group of eleven men, ten got on. Jimmie Moore, former radio-operator-gunner, didn’t make it. “You’ll get on tomorrow,” we consoled him. But Jimmie was broken-hearted. “I know my service record is in order,” he muttered dejectedly. “It always happens to me.” He lay in his bunk and sweated it out. We, the lucky ones, thought of tomorrow, our first day of processing, and many obstacles loomed in our minds. Suppose we flunked the physical test and the Army refused to release us? Suppose Finance snafu-ed the works? We built a thousand pessimistic suppositions. A former paratrooper in dirty uniform and sparkling jump-boots summed up our feelings: “You ain’t out of the Army till you got that white piece of paper.”

Our processing began in the afternoon. About fifteen hundred of us crowded into a large, unfinished auditorium to hear a welcome speech by a lieutenant, and an outline of the processing steps. Then the Protestant chaplain, who looked like a tough racket-buster, offered his three principles to guide us when we changed over from khaki to civvies. “Take it easy,” he thundered. “Have confidence in God,” and “Help build a better America.” It was a big order on a warm afternoon; and orientation talks never were popular among GI’s. But we were in a festive and magnanimous mood. And the chaplain had a sense of humor. “Take it easy,” he counseled, “no matter what you undertake. … If you want to get married, think it out, take it easy. If you want to use the vocabulary you acquired in the Army, think it over, take it easy. Ask for the salt if you want it; no adjectives needed, they’ll know what you mean…”

An Over-age Destroyer-a man 38 or more being released because of age-said philosophically: “The only way to beat the insurance companies is to die young.” How to convert bur government insurance was the most debated question. We argued it among ourselves in the barracks, and sought clarification on the following morning when our group started processing in earnest. The counselors sat in plywood-partitioned cubby holes, armed with our service records and large, unpleasant-looking tomes. My counselor, a staff sergeant who’d toured the globe for the Army, had a friendly handshake for me. He said he would give me as much time as I desired. He was here to help me and advise me on my rights as a veteran; how to convert my insurance, and so on. We scanned my service record thoroughly, and toward the end, when we got up, he put his hand on my shoulder and said in paternal fashion: “I’d also advise you to have some children. In old age they make life much brighter.”

In the afternoon the much dreaded physical examination came up. It was as thorough as the one I had during induction several years ago, but much less personal. The doctors and medics seemed more harassed and colder; they worked at a swift pace, and there was little time for oral questioning. One doctor regarded us with envy and said: “I heard a rumor the Army is going to discharge a doctor this year.” We were thumped and jabbed and stabbed by needles and shoved along in assembly-line fashion until we were thoroughly explored and recorded and ordered to dress and leave. My friend, the waist gunner, was told to stay; the doctors discovered a murmur in his heart. He sat in misery, upstairs, awaiting reexamination. Some were advised to file claims with the Veterans’ Administration for service-connected disabilities. One fellow with large, feverish eyes who suffered from recurrent malaria, asked: “If I file a claim, will it hold up my discharge?” He was assured that it would take only an additional ten minutes to file a claim with the VA. Of course, one was not certain of having the claim approved, but it was best to have it -on record, for some of the service-connected disabilities were liable to grow worse in the future. By filing now, one would save a great deal of time and red tape. But there were many men who did not file claims because they feared it might create another obstacle in their path to liberation.

We were through for the day. In the evening we drank beer out of small paper cups at the PX, and studied the merchandise on the shelves. It reminded me of the evening before our crew took off for overseas. We had done a great deal of shopping. We bought razor blades, pipes, tobacco, candy, cigarettes; our co-pilot took along silk stockings and rouge and lipstick in order to establish a good bargaining position with the girls in the ETO. Now we were studying the shelves again, wondering what to buy before taking off into the unexplored domain of civilian life.

There was no hell-raising in the barracks. If there was any joy in our hearts, it was an inner joy. We asked each other, somewhat sheepishly: “What do you intend to do for a living?” Most of us did not intend going back to our old jobs. The future for us was tomorrow – when we would get that White Piece of Paper; beyond that was a blank. Jimmie Moore, who’d spent the day listening to the loudspeaker and scanning the many rosters, was more dejected than ever. “Tomorrow will be two days, and I ain’t on yet.” Some men played poker; not recklessly, not like overseas when money meant little, when you did not know whether you would be alive the next evening to play again.

The lights went out at 10 p.m. One tech sergeant, who had flown missions out of England and had been wounded and, much decorated, mused out loud: “Seems to me,” he said in mock dejection, “I never will get that Good Conduct Ribbon.” His record was spotless, he assured us, but it seemed, he never was stationed in one place long enough to receive that award. His service record stated that he was “favorably considered” for that’ high honor at eight different camps. “Now it’s too late,” he said with resignation. “What will I tell my grandchildren, when they ask: ‘Grandpa, did you receive the Good Conduct Ribbon in the Great War?’” Beneath the sergeant, in the lower bunk, a high-point cook’s helper outlined his plans for the future: “I’m going back to Italy,” he said. “I got a woman there, and she’s got two kids. I never seen a cook like her in all my life!” A private from New York, said: “I can just see myself … riding on the Eighth Avenue subway. … All of a sudden I feel inside my shirt and discover I ain’t got my dog tags on … I’m scared stiff an MP will catch me and I’ll get restricted. “So I pull the emergency cord for the train to stop, and I run home for my dog tags. … I can just see it.” Another man said: “Tomorrow I’ll be a civilian. From tomorrow on I ain’t stationed in a place, I live there, see! And when I decide to travel, it ain’t ‘…in accordance with AR 20-64, said EM ordered to report at destination no later than …’ I report when I please. And when I go some place, it ain’t on a furlough 15 days plus traveling time-it’s a vacation and I stay as long as I want. Tomorrow I’ll be a free man.”

The waist gunner who was held back because of his heart murmur did not indulge in flights of fancy. And neither did a couple of other men who were scratched from the roster for further check-ups. They could sweat it out several days more; but each day was eternity.

For most of us it was the last night in the Army. No doubt some felt a sentimental twinge in parting with a life so thoroughly lived that its imprints would linger forever in one’s being. It had not all been blood and sweat, and even for those of us who had seer the burial of our comrades, there had also been many moments of joy and warmth and common feeling of accomplishment. And some of us spoke freely of joining the Reserve and even reenlisting if we could not make a go of it in civilian life. An infantry sergeant who had been through the hell of Anzio, said: “For months now I’ve been sweating it out, looking forward to this. Now that it’s come, I’m afraid.”

In the morning-our last morning as soldiers-the omnipresent loudspeaker from Operations instructed us to turn in our bedding and to fall out in front of Operations with our baggage. We said goodbye to the men who stayed behind. Jimmy Moore, who had finally got on a roster, remarked: “You guys will be unemployed just two days longer than me.” A guide with an orange armband marched us off at 7:30 past the mess hall where German PWs were sweeping the cement sidewalk and eyeing us blankly. Among us there were some angry mutterings, and then someone in our ranks started humming: “When this war is over, we will all enlist again, When this war is over, we will all enlist again, Like hell we will, like hell…”

We were marched into a long, fluorescent-lighted building to sign the discharge papers. Even for the average Army cynic the impending ceremony had a touch of solemnity in it. We lined up along a tall table and our service records were placed in front of us, on large blotters covered in ink with many names that preceded us. We were told to sign three copies, one in indelible pencil. The instructions were concise and simple; certainly there could be no room for error. Arid yet we were nervous. And the huge, sandy-haired man whose name was Dombrowski trembled when he took up the pen and, beads of perspiration stood on his forehead. After the signing and finger-printing we stood outside briefly to relax from the ordeal.

At the clothing-exchange shed, grimy shirts and trousers were discarded for new ones. A doggie parted reluctantly with his high infantry combat shoes. “They ain’t even-good for work,” he said. Someone suggested they were perfect for hunting. “Not job-hunting,” the doggie said, trying on a pair of GI shoe, “sand that’s the only kind I’ll do for a while.”

For some days we’d looked with envy on men who had the cloth discharge emblem sewn on their uniforms. We deemed such honor and accomplishment beyond our reach. Now it was our turn. A battery of sewing machines which lined two sides of a large shed was operated by GI’s with bored expressions. They grabbed the shirts and blouses we threw down on the tables, and the needles raced above the right breast pockets, wedding the shiny, golden emblem irrevocably to our shirts. We dressed and patted the emblem lovingly, and we were off again, to Finance, this time. On the company street we saw a group of Negro dischargees march by; they were processed separately, as if belonging to another army. But they too wore happy grins.

At Finance, the pay roster was called, and we lined up again to receive our final pay. This was the last hurdle. The room was filled with smoke and nervous chatter. The paratrooper who still had his shiny boots on, said, “Soon as I get the dough from the cashier, I run. Don’t matter if I get overpaid or underpaid. And by the time they find the mistake, I’ll, be in Buffalo.” The loudspeaker interrupted our speculations and warned us that of the money due us, all but $50 would come in check form. It was for our own protection, the loudspeaker said, for there were instances in the past when a man who carried $500 with him when he left the discharge center would beg an MP for carfare to get out of Trenton.

We were paid and given our lapel discharge button. The paratrooper did not take off across the fields. Everything went smoothly and efficiently. Outside, a Permanent Party non-com said: “Everybody put on a tie and smarten up because we’re going to the chapel from here for the discharge papers.”

About 300 of us took our seats silently in the big, mural-covered chapel: I remembered the one at Grand Central Palace in New York when I was sworn in. The room was dark then and hushed in silent bewilderment. This was a little different. The windows were open and the bright sun came in. A major with narrow eyes sat on the podium underneath a flamboyant mural depicting George Washington reviewing two armies: the Continentals and the Army of today. In the pear, on the balcony, the organ played softly: “America” We looked back, and the Wac at the organ winked at us: The Jewish chaplain said a brief prayer. I did not hear the prayer. And I caught only snatches of the major’s speech who said he was bidding us a warm farewell in the name of the Chief of Staff. I watched the faces of my buddies, and; like myself, they were impatient to hear their names called. The major stepped down from the podium. He took up the envelopes which contained our discharges and the names were read off. A name was called and a man stepped forward to salute for the last time and to receive his paper after a hearty handshake. The ceremony proceeded quietly. Occasionally the major found it difficult to pronounce names that were of Polish, Czech or perhaps Armenian origin. And they were all there, in this small group, names from all the lands and religions that forged out of their blood the flaming letter V.

LOUIS FALSTEIN

________________________________________

Oak Ridge: Secret City

The New Republic

November 12, 1945

I asked my driver, a young woman from this Bible Belt country, where the plants were.

“Well git to ‘em,” she said with a knowing smile.

“It takes time.”

And like a trained guide she pointed to the neighborhoods and called them off:

“Where you’re staying, that’s Jackson Square, main residential and business section.”

I scribbled in my notebook:

Pine Valley, Elm Grove, Grove Center, Jefferson Center, Middletown, Happy Valley.

While pointing out the neighborhoods,

she also suggested that I jot down the A&P’s,

the Farmers’ Market, Supermarkets,

and a hot dog stand selling Coney Island dogs for ten cents.

She called my attention to the fact that in the Trailer Camps

the streets were named after animals: Squirrel, Terrier, Racoon.

But I didn’t ask her how come there was a Lincoln Road in the heart of Tennessee.

EIGHTEEN MILES WEST of Knoxville lies the town of Oak Ridge, birthplace of the atomic bomb. We drove over a recently constructed road and I asked the driver, a young private, when the road was built and how far it extended. He smiled obligingly, hesitated and finally said: “Suppose it’s perfectly all right to tell you, but I wish you’d inquire about it from the proper authorities when we get to Oak Ridge.”

____________________

Drawing by Eric Godal. Copyright by Field Publications, Inc., and reprinted by courtesy of PM

____________________

That was my first lesson in what is a habit of long standing with Oak Ridgers: security. I found out that security includes not only the Clinch River and Cumberland Mountains which keep the outside world from this atomic city. I saw gates within gates and barbed wire fences and signs warning of “Prohibited Zones” and “Restricted Areas.” And posters in dormitories, offices and stores: “Protect Project Information….”

People in authority say, “Don’t quote me on this” or ‘This is off the record.”

A young scientist told me, “Even those who talked m their sleep learned to keep their mouths shut.” I asked naively wherein lay the danger of talking in one’s sleep, and the reply was: “What if the wife heard you?” Things aren’t so bad now, he said with relief. “There was a time, coming home from the lab, when I couldn’t talk to my wife at all. I pretty well knew what the Project was making, but I couldn’t tell her. We’d sit around the dinner table and the strain was terrible. A man could bust. Then we started quarreling. Over nothing, really. So we decided to have a baby.”

A psychiatrist at the Oak Ridge Hospital told me of his increased work load during the days before the Bomb was dropped. “The strain was terrible,” he said. “I had my hands full. But practically no one talked. One fellow couldn’t stand it, so he told his wife. But she felt the secret was too much for her and she told it to a friend. So they had to terminate all three of them in a hurry.”

Actually very few of the 75,000 Oak Ridgers knew what was being done on this great reservation. Some rumors had it that synthetic rubber was being made. Wiseacres said they were getting ready to manufacture buttons for the Fourth Term. One plant didn’t know what the other was doing, and even within plants the work was completely departmentalized. The people on top knew, the scientists knew, but they didn’t talk. The Bomb hit Hiroshima and the Oak Ridge Journal ran a banner head: “Oak Ridge Attacks Japan.”

But the people still don’t talk. The whole world knows what Oak Ridge is producing. What isn’t known is how it’s being produced. As an outsider you will be heard out with tolerant suspicion when you talk of atomic fission or the Bomb, but if you mention plutonium or U-235, the cold stares set in. The more polite Ridger will listen to your question, dig into his pocket for the Smyth Report, and pointing to a well worn page, will say: “There is your answer.”

The fact of the matter is, the Smyth Report contains more information about the Bomb than most people in this town possess. The ones who know more keep it to themselves, and the rest feel it’s none of your business.

At first glance you wonder what all these thousands of people from all parts of the United States are doing in this hidden Tennessee country. From the ridges-which lace the reservation in all directions, you look in vain for signs of industrial activity. Finally you discover several smokestacks. But they are smokeless. All over the place, seemingly planless at first, are a jumble of hutments, barracks, dormitories, trailer camps. Perched on the ridges are the dormitories on stilts looking like chicken coops, the houses and permanent apartments. The over-all impression is a combination of army base, boomtown, construction camp, summer resort. The “Colored Hutment” section looks like an Emergency Housing Slum Area.

I asked my driver, a young woman from this Bible Belt country, where the plants were. “Well git to ‘em,” she said with a knowing smile. “It takes time.” And like a trained guide she pointed to the neighborhoods and called them off: “Where you’re staying, that’s Jackson Square, main residential and business section.” I scribbled in my notebook: Pine Valley, Elm Grove, Grove Center, Jefferson Center, Middletown, Happy Valley. While pointing out the neighborhoods, she also suggested that I jot down the A&P’s, the Farmers’ Market, Supermarkets, and a hot dog stand selling Coney Island dogs for ten cents. She called my attention to the fact that in the Trailer Camps the streets were named after animals: Squirrel, Terrier, Racoon. But I didn’t ask her how come there was a Lincoln Road in the heart of Tennessee.

“I want you-all to write a good story about Oak Ridge,” she said warningly. “There’s been many of you writers from the North, but I ain’t seen a good story yet. You fellas don’t seem to git the sperit of this place.” I heard a great deal more on the subject of “the spirit” from articulate residents during my stay.

“There’s 53 old cemeteries here,” my informant continued, “spread over the 95,000 acres of Roane an’ Anderson Counties. When the people was moved off the land for the Project to commence, the Army promised it would take care of the cemeteries. And they do.” On Decoration Day the approximately 3,000 former inhabitants of these ridges are all granted passes to come and decorate the graves, “What happens when somebody on the Project dies?” I asked. “Well,” my driver said, “they’s shipped back home where they’s from.” What’s more, she added, few people ever die here, because most of the workers are young. “I never seen a grandmother in two years I been here,” she said.

The plants are widely dispersed and hidden in the valleys. Miles of wooded areas separate them from one another and from the residential districts. Mountains and ridges prevent any observation until you are actually near them. First come the warning signs, then the big fences and guard towers, and in the background are the massive atomic fortresses. Again there are smokestacks, and no smoke pours out. I said to my guide it didn’t seem to me as if anything were going on inside those plants. “Plenty going on,” she replied, “just ain’t no smoke to it.”

The mystery deepened even more with the realization that while a great many things entered the huge structures, very little seemed to come out. Later I learned that it required big quantities of ore and many complicated processes – done here and elsewhere-finally to isolate the negligible bit of precious uranium from the mixture of U-235 and U-238.

There are several methods of extracting the uranium. The Tennessee Eastman plant, known as Y-12, and comprising 270 buildings, uses the electro-magnetic process. Carbide and Carbon Corporation, K-25, occupying 71 buildings, obtains the same results by gaseous diffusion. S-50, operated by the Fercleve Corporation, employs the thermal-diffusion method. All these processes have been tested, and they all work. X-10, the Clinton Laboratories, formerly connected with duPont, are doing research on plutonium, the main plant being at the Hanford Engineering Works in the State of Washington.

Three shifts keep the plants in operation day and night, and thousands of workers and technicians from Oak Ridge and its environs check in past the maze of fences, guards and more guards. Few of them ever see the finished product, and before the Bomb struck Hiroshima they hadn’t the least inkling of what was going on behind the thick walls that separated them from the radio-active uranium. Charlie Chaplin’s awe at entering the super-modern factory in “Modern Times” was nothing compared to what the Project workers first experienced in the plants. Charlie at least saw what he was making. The Ridgers still can’t see, but they know. There’s a purpose to all the button-pushing; and fantastic equipment.

“I still don’t see how a gadget can take the place of a brain,” a worker said philosophically, “but leave it to them long-hairs to think things out.”

Three years ago the Manhattan Engineer Distict was a plan. The Black Oak Ridge country was chosen as one of the three atomic sites for its electric power, supplied by the TVA, its inaccessibility to enemy attacks, its water supply and the then uncritical late area. The small farmers who inhabited these ridges were moved off the land with proper remunerate and dispatch. They could not be told why.

The bulldozers moved in, and with them arrived the jeeps and the automobiles. The army, having the scientists in mind at first, built several hundred permanent houses and put fireplaces in them. Often the fireplaces were there before the walls were up. Then the plans were changed, and more houses were built. More workers arrived, and the need for shelter became acute. They started building barracks, hutments and the TVA came to the rescue with those square, matchbox demountables. And finally the trailers were bought in and set up below the ridges.

IT WAS not an inspired migration. Many were lured by high wages; others by promises of comfortable living. The scientists, those who had worked with the Project in other parts of the country, knew the reasons. The GIs came because they were told to come. One woman said it was a good way of getting rid of her husband. “I knew he couldn’t follow me past the gates.”

They waded in the red-clay mud, and some walked about barefoot for fear of losing their shoes. The clay was hard and they had to water it at night in order to dig it next morning. People knew there was no gold to be found in the Cumberlands, and therefore it is the more remarkable that they worked with such fervor and pioneering zeal.

When Oak Ridge had 15,000 inhabitants, there was only one grocery store in town. Businessmen, unable to find out the potential number of customers or clients, were reluctant to move in. One five-and-ten concern asked for a contract barring competitors for a period of ten years. Slowly, warily, entrepreneurs set up shop in Oak Ridge. And they’ve done quite well by themselves, so well, in fact, that the OPA has had to step in on occasion to curb some enterprising souls.

Roads were laid out, buses started to operate, taxi-cabs were brought in. Neon lights went up on business establishments, and some people started calling Oak “Ridge “home.” They cut weeds and planted Victory gardens and raised pets. People started having children, many children. “Pretty near all there was to do in those days,” a father said.

Today the city has its Boosters and Junior Chamber of Commerce, and a Women’s Club. It has beauticians; one hair stylist advertises as being connected “formerly [with] Helena Rubinstein’s Fifth Avenue, N.Y.” There are tennis and handball courts. A symphony orchestra, composed of Project employees, is led by a prominent scientist. There are seven recreation halls into which people can wander and join a bridge game or participate in community singing. There are several movie houses and a Little Theatre and a high school. But Oak Ridge still has no sidewalks. “When I first came here,” a youngster of ten said, “I missed sidewalks most. Now I don’t care.”

Some people point with pride. Others point at the “Colored Hutments,” where living facilities are primitive, to say the least, though comparable to some of the housing for white workmen. Negro children are not permitted to go to school with whites; they journey to nearby Clinton for their education. And for that reason many Negroes did not bring their children to Oak Ridge. Plans are now being made to provide school facilities for the Negroes as soon as a sufficient number of children are enrolled to justify it. They have one recreation hall, the Atom Club, and one movie house, which is located 12 miles from their hutments, in the K-25 area.

The GI scientists point to the great discrepancy in salaries.

No one points at the food served at Oak Ridge cafeterias, and that’s as it should be.

One of the town’s most interesting institutions is the Oak Ridge Hospital. It is an experiment in what its brilliant young director, a lieutenant colonel, says “has absolutely no relationship with socialized medicine.” He calls it “The Group Insurance Plan.” Nevertheless, I advise Dr. Fishbein not to be lulled by the colonel’s reassurances. The plan works something-like this: each family head pays $4 a month, and the medical services include all his children below the age of 19. Doctors make private calls, but the fees go to the hospital. There is no private practice. The hospital has 300 beds and can handle 1,500 in-patients monthly. Five psychiatrists are attached to the institution, and their emphasis is on what they call group therapy. The hospital is staffed with high-caliber practitioners, many of them from the Mayo Clinic. Everybody in Oak Ridge can afford to enjoy good health.

THIS is the only city in the United States which has no unemployment and no reconversion problem. There are no election headaches, since the councilmen act only in an advisory capacity to the District Engineer, who is both an army officer and the mayor. Those who acquire an additional child try to move from a B-house to a C-house, and so on up to a F-house, which rents for $73 a month. And those who marry and are lucky move from their “Single”‘ dormitories to an A-house. But no matter where they move, most of it is Cemesto (cement and asbestos rolled into sheets). And there’s a feeling of temporariness about the whole place. The one bank in town is bulging with assets, for which the state of Tennessee is not ungrateful. The inhabitants of Knoxville have learned to tolerate the outsiders, if not for their ways, for the revenue they’ve brought.

There is a tendency among many to talk about the “past” and about “the spirit” they had “in those days.” A few have left for the other “home,” but most are waiting. The Bomb that pulverized Hiroshima was the reason for their existence. The world was shaken to its very foundations. Now the people who’ve unchained this fury are thinking of its implications not only lor their immediate tomorrow, but for the world’s also.

Louis Falstein, recently discharged from the Army, flew 50 missions with the 15th Air Force. Now in New York, his working on short stories and a novel. He visited Oak Ridge as a special correspondent for the New Republic.

________________________________________

The Men Who Made the A-Bomb

The New Republic

November 26, 1945

In July, 1945, the A-Bomb was tested in the desert of New Mexico.

I’m told that a flyer who was sent up to observe the explosion from a safe distance

was so startled by the bomb’s flash that he radioed a terrified message to the ground:

“The damned long-hairs have let it get away from them!”

The flyer was wrong.

The bomb was a success.

Many of the men who made it then petitioned the President

not to use it on the remaining Axis power, Japan, without prior warning.

However, they felt it was more dangerous for the world’s future to keep the bomb secret

than to explode it over Japan and thus shorten the war.

They wanted it to be used in some way,

realizing their own responsibility for the consequences.

With Hiroshima came the end of an epoch.

“When the papers came out with news and it was no longer a secret,”

an Austrian refugee scientist relates,

“we rushed it out in the streets and hollered ourselves hoarse:

“Uranium … graphite pile … uranium… Then we got drunk.”

X-10, OR CLINTON LABORATORIES, lies hidden between the ridges and is surrounded by great forests. The plant, inscrutable like all plants at Oak Ridge, shows no sign of life or activity. Three smokeless stacks and the white buildings give the impression of an abandoned ghost factory, and the guard towers and barbed-wire fences seem as if they are there only for the purpose of assuring peaceful slumber. Nearby, a big sign depicts a lazy sun coming up over the horizon with the inscription: “Dawn of Peace. Lee’s Make It Forever.” It’s a serene picture, but a false one. X-10 is very much alive. It works three shifts making plutonium for experimental purposes. And it has a greater concentration of scientists than any other plant at Oak Ridge, among them many G.I.s. Lately, these scientists have been very vociferous.

____________________

The Atom Squatters

Illingworth in the Trans-Atlantic edition of the London Daily Mail.

____________________

To Oak Ridgers the scientists are known as “long-hairs.” To mountaineer Southerners on the Project the long-hairs are a peculiar lot who were at one time in favor of interdenominational services, “all praying in one church and at the same time,” I heard said with obvious disapproval. And their children in school are forever clamoring for more student representation on the council. “They got ‘em that Symphony Orchester playin’ classical stuff.” Some of them don’t like segregation of the Negroes into “Colored Hutments” at Oak Ridge. Now they’re raising a fuss about what should be done with the A-Bomb.

I was introduced to my first long-hair in the lobby of the Oak Ridge Guest House. He was a tall young man of about twenty-five, and was absorbed in the funnies when I came up. “I like the funnies very much,” he said, “but Orphan Annie’s politics make me mad.”

In the evening I met another long-hair. He, too, was in his twenties. His wife looked like a girl recently out of college. “And this is my dog, Pluto,” the young scientist said, “named after plutonium. A very intelligent dog.” He turned to the dog and said: “Pluto, would you rather work for duPont or be a dead dog?” Pluto rolled over on his back and played dead. The owner tossed him a biscuit. Then he said: “Have you seen the May-Johnson bill? It’s suicide. Something must be done …”

There are 75,000 people at Oak Ridge connected in one way or another with the Project. The Project is making atomic bombs. The war is over, and the Ridgers are well aware of the fact that atomic bombs are not needed for peace. They’re thinking of the A-Bomb and the future, but only the scientists have made themselves heard. I wondered whether the others were silent because of their long habit of security or from fear of censorship by the Army. One chemist said to me: “I just don’t think there’s any hope. Don’t quote me on that. I feel a terrible guilt. I sometimes wish I could be religious.”

The Oak Ridge Journal, a town weekly, carries in its October 18 issue an interview with five Project workers picked at random. “What form of control do you favor for the atomic bomb?” To the outside world such a question suggests nothing out of the ordinary. But in Oak Ridge, where the people have kept quiet for three years, and where one of the large companies recently issued an order through the Army, forbidding, among other things, discussion and speculation on “…international agreements, beyond the presidential releases …” the Journal’s modest poll is quite significant. Of the five questioned, four expressed themselves as favoring some sort of international control, while the fifth, an Army sergeant, said: “We should keep it here and use it as a powerful threat to ensure world peace…”

THE SEVERAL HUNDRED civilian scientists at Clinton Laboratories have organized to find an answer to this most urgent problem. I met with members of the executive committee of the Association of Oak Ridge Scientists. It was somewhat surprising to find that the oldest man in the group was not yet thirty. But these men, chosen for their outstanding work in physics and chemistry, are a mature and responsible lot. There is an urgency about them now, and deep concern in their faces. They’ve fashioned a terrible weapon and consider themselves the Responsibles. They think how the weapon should be controlled jointly – by the world.

Who are these Responsibles? Most of them have been with the Project since its inception. They worked with it in Chicago on the “Metallurgical Project,” where the first experiments were made on a limited scale with graphite piles by Dr. Fermi. Unlike most Ridgers, they knew what the Project was doing in its later stages, and what its end product would be. They worked stubbornly, tirelessly, completely disregarding their own safety. They, too, were front-line soldiers. “When Dr. Fermi set off the first graphite pile beneath a fence near Chicago University,” a young scientist reminisced, “some men stood around with water hoses to put out the fire if the chain reaction threatened to get out of control. I was praying hard, hoping it wouldn’t blow sky high, and there were these guys with little water hoses!”

When part of the Project moved to Oak Ridge in 1942, the scientists moved with it. Many of them went to work at Clinton Laboratories for further research on plutonium. And there, side by side with GI scientists, they embarked on a feverish race with Hitler for the completion of the atomic bomb. They trudged through the red-clay mud and often spent sixteen hours daily at the laboratory. At home, evenings, they stared at their wives silently. They could report neither their near-successes nor failures. The wives learned not to ask questions. “So we played Chinese checkers,” one physicist said, “till we got sick of it.”

“Once I found myself doodling on a piece of paper after dinner. My wife came up to where I was sitting. She didn’t say anything. We’d got into the habit of not talking. But she looked at the paper on which I was drawing aimlessly and her eyes seemed to ask the question: ‘What are you doing?’ And what was I doing? Drawing a chain reaction on paper unconsciously. I tore the paper and threw it in the fireplace. Then we went to bed.”

Dr. Harrison Brown, who had come to the Project from Johns Hopkins and who at the age of twenty-nine is an outstanding scientist and member of the Association, told me the story of those heartbreaking and crucial days. “On New Year’s Eve, 1943, we finally achieved our first great goal,” he said. “A complete milligram of plutonium – 1/1000th of a gram! We sent it off to Chicago for critical experimental purposes and stayed in the laboratory to celebrate. But how long can you keep slapping each other on the shoulder? We could not tell our wives of the great triumph. So we retired at nine.”

In July, 1945, the A-Bomb was tested in the desert of New Mexico. I’m told that a flyer who was sent up to observe the explosion from a safe distance was so startled by the bomb’s flash that he radioed a terrified message to the ground: “The damned long-hairs have let it get away from them!”

The flyer was wrong. The bomb was a success. Many of the men who made it then petitioned the President not to use it on the remaining Axis power, Japan, without prior warning. However, they felt it was more dangerous for the world’s future to keep the bomb secret than to explode it over Japan and thus shorten the war. They wanted it to be used in some way, realizing their own responsibility for the consequences.

With Hiroshima came the end of an epoch. “When the papers came out with news and it was no longer a secret,” an Austrian refugee scientist relates, “we rushed it out in the streets and hollered ourselves hoarse: “Uranium … graphite pile … uranium… Then we got drunk.”

IN THE FIRST WEEK of September the scientists at X Oak Ridge began informal meetings to discuss the implications of the A-Bomb for the future. They found their concern shared by others. Two weeks later they set up a tentative organization and elected an executive committee. They issued their first Statement of Intent, boldly announcing that: 1. The A-Bomb is no secret. 2. We cannot long have a monopoly of its manufacture. 3. International control is the only solution.

By the end of September more than 90 percent of all civilian scientists at Clinton Laboratories banded formally into the Association of Oak Ridge Scientists. Similar groups came into existence in Chicago and Los Alamos, New Mexico.

Dr. P.S. Henshaw, a biologist on leave from the National Cancer Institute and one of the leading members of the Association, summed up the scientist’s viewpoint. “For many years an accusing finger has been pointed at the scientist for his concern solely with the work in his laboratory. To some extent such accusation was correct. We were not, in large, concerned with the social implications of our work. But now we can no longer remain unconcerned. The necessity to speak out has been forced upon us by the nature of the weapon which we ourselves helped make. Man’s very existence is threatened unless intelligent use is made of our discoveries.”

It is ridiculous, the scientists point out, to claim that the A-Bomb and the so-called “know-how” can remain strictly an American possession. What about the great roster of European scientists who have experimented in the nuclear field for many years? And what about the scientists of European origin who had worked on aspects of the Project and who have since returned to their native lands? Nor need the other countries invest two billion dollars to achieve their goals. Our work was handicapped by the necessity for basing major decisions on largely theoretical predictions. They know the A-Bomb works. They know it can be manufactured through any one of four processes: electromagnetic, gaseous diffusion, thermal diffusion, and plutonium. They need use only one of these methods, or they can develop one of their own.

The May-Johnson bill, the scientists feel, even if considerably watered down by amendments, will defeat the very purposes which its short-sighted backers seek. For, rather than work under a cloak of secrecy and be subject to all manner of restrictive measures, many nuclear scientists will leave the field altogether, as some have already threatened to do.

The scientists do not claim to have an answer as to how the world should get along. They say an answer must be found. The world cannot afford not to get along. If we reveal no more information to the other nations, this country may hold leadership for a few years. After five years the United States cannot rely for its security upon producing more deadly atomic bombs. This knowledge has led some to propose that we ensure our security by forcibly preventing other nations from producing atomic bombs. Since no nation would peacefully accept this prohibition, such a step would mean that we should have to conquer the world within the next five years. At the present stage of atomic development, such world conquest would be neither quick nor certain. Nor would the American people acquiesce in such a course.

International control [say the scientists] is another alternative that has been widely proposed. No specific plans have been prepared, and we do not intend to offer one. We recognize that any such plan involves many difficulties, and may require that in order to preserve the peace of the world, we forgo some potential peaceful applications of atomic power and some phases of our national sovereignty.

The alternatives are clear! I If we ignore the potentialities of atomic warfare, in less than a generation we may find ourselves on the receiving end of atomic raids. If we seek to achieve our own security through supremacy in atomic warfare, we will find that in ten years the whole world is as adequately armed as we, and that the threat of imminent destruction will bring about a “preventive war.” If we recognize that our present leadership in atomic power can last at the most several years and we attempt to dominate the world, we will find ourselves immediately involved in another and greater war in violation of our democratic moral code and with no assurance of victory.

In view of the disastrous nature of these alternatives, we must expend every effort to achieve international cooperation and control as the only possible long-term solution.

We strongly urge the people of the United States and their leaders to think about, and find means for, the international control of atomic power. The United States must exert leadership to promote this. The citizens of our country, together with the peoples of the rest of the world, must demand that their leaders work together to find the means of effective international cooperation on atomic power. They must not fail. The alternatives lead to world suicide.

I talked to the men who made the A-Bomb, and that’s their message to you.

Louis Falstein, recently discharged from the Army, flew 50 missions with the 15th Air Force. Now in New York, his working on short stories and a novel. He visited Oak Ridge as a special correspondent for the New Republic. He visited Oak Ridge as a special correspondent for The New Republic.

________________________________________

Veterans Welcome

The New Republic

January 28, 1946

The young man with the ruptured duck is skeptical and cautious,

as a result of his bitter experiences with authorities, promises and flowing phrases.

He is justifiably disillusioned with the state of our nation,

and the great danger is that he will retire into himself to sulk alone.

A greater danger is that he will be attracted by the fascist groups

who will direct his disillusionment into their own channels.

It is incumbent on all progressive veterans’ groups

to speak out boldly on the pressing issues of the day;

to take sides with men who act for progress.

Show the veteran the proper path, and trust his intelligence.

THE YOUNG MAN wearing a “ruptured duck” in his lapel may not be the most popular guy in the world with the housing authorities or the employment agencies, which are downright ashamed of their meager offerings, but there are more than half a hundred outfits who shout a lusty welcome to our hero. These are the veterans’ organizations, and they’re out for big business. The ruptured duck, so far as the mushrooming legions are concerned, is a soaring eagle, and nothing is too good for the man who wears one. Thirteen million men and women will eventually be veterans; add their families, and the sum total means a sizable chunk of influence for good or bad.

Heading the vast array of ex-servicemen’s organizations are the Big Two: the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars. Both have been in business a long time and are well aware that their considerable prestige can be maintained only by striking out for the new returnee. The AL and the VFW have set aside great sums of money for high-powered campaigns that reach out to the prospective veteran while he’s still overseas. The Legion is reputed to have a hundred million in the kitty, with a plan for setting up a radio station, FM, television, all working toward the goal of five million members by 1947.

It’s a long haul, but the AL is in an advantageous position to get the desired quota of 3,300,000 new members. The influence it wields, particularly in small towns throughout the country, is undeniably strong. Like the VFW, the Legion is firmly established with its rituals, halls, bars, billiard rooms and occasional parades down Main Street to show off the brand-new veteran to admiring and cheering crowds. There’s the handshake and the slap on the shoulder and a few drinks. Then a promise of the old job back, perhaps, or the “let’s-see-what-we-can-do-for-you” attitude. The pressure is strong, and the small-town veteran joins, in the end, not only for the social and economic benefits, but because it is the prudent thing to do. In the larger cities, where social outlet is greater and more varied, the Big Two are making slower progress.

Six hundred thousand new veterans have joined the American Legion in the past few years. The old men are still in control, but the young voices are being heard. The recent convention, held in Chicago, was the soberest in years, and a new, serious note was injected into the deliberations. A move to deny charters to new Labor Legionnaire Posts, of which there are already more than a hundred, was defeated on the convention floor. The Labor Legionnaire Conference proposed some resolutions that would have brought down upon it the wrath of the Americanization Committee in the past. Among the proposals were: action on the full-employment bill; condemnation of the Wall Street Post for an “Americanism” award to Cecil B. De Mille; opposing the National Convention’s going on record regarding compulsory military training, until all men were out of uniform and able to vote on the subject. The Labor Legionnaires urged the convention to reverse its previous stand on immigration; to encourage the passage of the 65-cents-an-hour minimum-wage bill and abolition of the poll tax; to endorse the winter clothing drive for the Yugoslavian people. The labor resolutions were not adopted, but for the first time in its career, the AL Convention listened to a CIO speaker. Its final decisions were no model of progressivism, but it would be wrong to assume that the powerful American Legion, which contains so many new veterans, can be ignored and shunned.

The VFW, older but numerically smaller than the AL, has, on the whole, been the more liberal of the two. There is no doubt that the 800,000 new members – out of a total of 1,000,000 – have to a great extent generated the fresh breeze now coursing through the smoky VFW halls. Several posts have collaborated with trade unions on issues pertaining to veterans. These moves have not been discouraged by the top leadership, which is committed to expansion. The organization’s great enticement is a proposal for a Big Bonus which is calculated to give the veteran a huge amount of money, a maximum of $5,000 per man.

Both organizations make grudging provisions for Negro veterans, who are shunted into posts of their own. The AL has posts for women, while the VFW decided at its recent annual encampment in Chicago to postpone the woman problem until next year.

TRAILING the Big Two is a roster of new veterans’ organizations, ranging from budding progressivism to outright pro-fascism. Gerald L.K. Smith, of the America First Party, is the chief-of-staff of the Nationalist Veterans of World War II. Smith wants the white “Christian” veterans only. “My time will come,” warns the bombastic disciple of the late, unlamented Huey Long, “in the postwar period, in the election of ‘48. The candidate will not be me – it will be a young veteran of this war – but I’ll be behind him. If business conditions are bad – inflation, widespread unemployment, farm foreclosures – then my candidate will be elected.”

Edward J. Smythe, a defendant in the sedition trial of 1944, has hatched the Protestant War Veterans, “a voluntary association of white gentiles of the Protestant faith who served in any of the wars of the Republic.” He advocates a bonus of $1,000 for every discharged veteran.

Joe McWilliams, the Yorkville Fuhrer who has managed so successfully to keep out of trouble with the law, put his pro-fascist cronies to shame with his stupendous “Serviceman’s Reconstruction Plan” which “will utterly destroy the long prepared program of the Marxists.” And the way to achieve this is by “the just payment of $7,800 to our several million militarily trained young men and their establishment as business-owning citizens …” The Chicago Tribune, an old hand at protecting “the American way,” has supported the plan.

There was a time when the Shrine of the Little Flower out at Royal Oak, Michigan, was known among Detroiters as the Shrine of the Little Swastika. Social Justice was banned in ‘42, but you can’t keep a good man down. Father Coughlin, whose heart “bled for the people,” formed the Saint Sebastian Brigade, this time to “help” the soldier. He collected 400,000 names of servicemen from wives, mothers and sweethearts, and he prayed with equal fervor for all of them to St. Sebastian, the soldier’s patron saint. There was an incidental charge for the services, amounting to $700,000. The St. Sebastian Brigade is not a veterans’ organization, but Father Coughlin, who never lets go of a good thing, should obviously be closely watched by the government, the Catholic Church and the people.

Behind these well known rabble-rousers are the smaller fry, and the list of their sponsors reads like Who’s Who at a sedition trial. They’re out in force to snatch the confused, disgruntled and embittered ex-serviceman. And unless something is done immediately to improve conditions for the new civilian, the fascists in our midst will reap a rich harvest.

Fortunately, the rabble-rousers do not have the field to themselves. Liberal and progressive groups are being formed throughout the country, some as small “committees,” others as fledgling organizations of veterans. Then there are those who appeal to limited groups, like the Jewish War Veterans, Catholic War Veterans, Italian-American World War Veterans, Blinded Veterans’ Association, Bilateral Leg Amputee Club of America, and others. One of the smallest but most active is New York’s Veterans Against Discrimination. Born as a result of John O’Donnell’s vicious attacks against minorities in the New York Daily News, the committee’s main function is picketing. The veterans picketed the News offices, and carried the fight to the large stores advertising in that paper. For whatever reason, some of the large advertisers in the News have recently withdrawn their copy. Veterans in other cities arc emulating New York’s example.

OF THE moderately successful new groups, the American Veterans of World War II, Amvets, has been bogged down recently by a series of splits and factional fights on the question of labor. The smoke of battle has not cleared, and it is too early to pass final judgment.

The American Veterans’ Committee, comparatively new in the field, but highly publicized in recent months due to its effective work on behalf of housing for veterans, is emerging as one of the important organizations. The Committee’s “Statement of Intentions” says: “We look forward to … living in freedom from the threat of another war … We are associating ourselves with American men and women, regardless of race, creed or color, who are serving with or have been honorably discharged from the armed forces, merchant marine, or allied forces …” Its aims include: “Adequate financial, medical, vocational and educational assistance for every veteran. Thorough social and economic security. Free speech, press, worship, assembly and ballot … Active participation of the United States in UNO … Establishment of an international veterans’ council for the furtherance of world peace and justice among the peoples of all nations.”

The AVC, with forty chapters in the states, is scheduled to hold its Constitutional Convention in Des Moines in March, at which time the committee will be transformed into a full-fledged veterans’ organization.

The young man with the ruptured duck is skeptical and cautious, as a result of his bitter experiences with authorities, promises and flowing phrases. He is justifiably disillusioned with the state of our nation, and the great danger is that he will retire into himself to sulk alone. A greater danger is that he will be attracted by the fascist groups who will direct his disillusionment into their own channels. It is incumbent on all progressive veterans’ groups to speak out boldly on the pressing issues of the day; to take sides with men who act for progress. Show the veteran the proper path, and trust his intelligence.

Louis Falstein, recently discharged from the Army, flew 50 missions with the 15th Air Force. Now in New York, he is working on short stories and a novel.

Here’s Some References…

Molto Buono, February 3, 1945 (page 3), at 450th BG.com

Manhattan Project, at Wikipedia

Oak Ridge, Tennessee, at Atomic Heritage Foundation

Oak Ridge National Laboratory, at Wikipedia

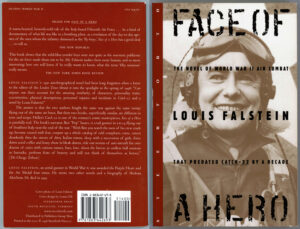

Falstein, Louis, Face of a Hero, Steerforth Press, South Royalton, Vt., 1999