[This post first appeared on April 30, 2017. Now in 2022, five years later, it’s been updated. In its original form the post only covered Army Air Force ferry pilot Captain Edmond J. Arbib, notice of whose death in a domestic training flight on July 12, 1945, appeared in The New York Times the following July 18. The post now covers incidents involving four other Jewish servicemen on that same July Thursday, part of a larger (lengthier) project of updating and expanding my other posts covering American Jewish WW II casualties reported upon in The Times.]

Even if “the war” in Europe had by the second week of May, 1945, ended, the war still continued: One airman was lost during a training flight in the European Theater, and two others in the Pacific Theater. The fourth Jewish soldier, Gunner Solomon Rosen, from Essex, England, having survived for three and a half years as a prisoner of the Japanese, died in Borneo.

Further details about these four men appear below…

On Thursday, July 12, 1945 / 3 Av 5705

– .ת.נ.צ.ב.ה. –

Tehé Nafshó Tzrurá Bitzrór Haḥayím

May his soul be bound up in the bond of everlasting life.

Notice about the death of Army Air Force Ferry Pilot Captain Edmond J. Arbib was published in the Times on July 16 and 18, with his obituary appearing on the latter date.

Captain Arbib, a member of the 5th Ferry Group of the Air Transport Command, lost his life while piloting Douglas A-26C Invader 44-35799. With 1 Lt. John W. Thomas (of Craighead County, Arkansas) as a pilot-rated passenger, his aircraft took off on a demonstration training flight from Love Field, in Dallas, Texas, and crashed northwest of Grand Prairie.

____________________

Veteran Air Force Pilot is Killed in Texas Crash

Capt. Edmond Joseph Arbib, Army Air Forces, 27-year-old veteran ferry pilot, was killed at Love Field, Tex., when his airplane crashed last Thursday, the War Department has informed his family here. Descended from Jonas N. Phillips, an American Revolutionary soldier, and from Henry Marchant, a signer of the Articles of Confederation, Captain Arbib was born in New York, the son of Mr. and Mrs. Rene S. Arbib [Rene Simon Arbib; 4/11/90-7/21/47], his father being a native of Cairo, Egypt, and his mother the former Miss Sylvia Phillips.

Capt. Edmond Joseph Arbib, Army Air Forces, 27-year-old veteran ferry pilot, was killed at Love Field, Tex., when his airplane crashed last Thursday, the War Department has informed his family here. Descended from Jonas N. Phillips, an American Revolutionary soldier, and from Henry Marchant, a signer of the Articles of Confederation, Captain Arbib was born in New York, the son of Mr. and Mrs. Rene S. Arbib [Rene Simon Arbib; 4/11/90-7/21/47], his father being a native of Cairo, Egypt, and his mother the former Miss Sylvia Phillips.

He enlisted in September, 1941, as a private in the ground forces of the AAF. In October, 1942, he received his wings. Captain Arbib ferried planes to every war theatre and served in the China-Burma-India theatre for nine months, making eighty-eight round trips over the Himalayan “hump”.

He held the Distinguished Flying Cross with three bronze stars, the Air Medal with two Oak Leaf Clusters and a Presidential Wing Citation.

Surviving are his widow, Mrs. Harriet Brodie Arbib; his parents and a sister, Mrs. Harold Bartos.

Amidst advertisements for women’s clothing, Southern Comfort, and Gene Krupa (in an “air-conditioned” setting, no less – well, we are talking 1946 after all) Captain Arbib’s obituary appeared on page 13 of the Times.

____________________

Born on January 23, 1918, Edmond was buried at the Beth Olam Cemetery, in Cypress Hills, Ridgewood, Queens. Note that his obituary calls attention to his descent from Jonas Phillips (1736-1803) and Harry Marchant.

____________________

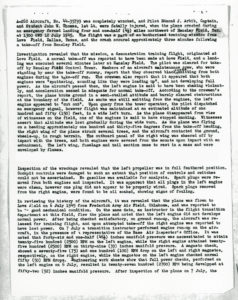

Here are images of the Army Air Forces Accident Report (46-7-12-5) covering the loss of A-26C 44-35799.

This is the report’s first page, which includes nominal information about the incident: date, time, and location, and, background flight experience of the crew members.

__________

Here’s the bulk of the Report’s text. Though it was determined by accident investigators that the port engine was feathered and not operating and insufficient power could be attained in the starboard engine to maintain flight, at the time of the crash, the specific cause of these mechanical problems couldn’t be established with certainty.

A normal take-off was reported to have been made at Love Field, and a landing was executed several minutes later at Hensley Field. *** Members of the aircraft maintenance crew, who were standing by near the take-off runway, report that they observed black smoke emitting from both engines during the take-off run. The crewmen also reported that it appeared that both engines were “sputtering, sound like they were loaded up”, and not developing full power. As the aircraft passed them, the left engine is said to have been shaking violently, and acceleration seemed inadequate for normal take-off. *** As smoke was still emitting from the engines, the left engine appeared to “cut out”. ***

Inspection of the wreckage revealed that the left propeller was in full feathered position.

Full consideration has been given to the experience and qualifications of Captain Arbib, and it is felt that normal preflight engine run-up was satisfactory, or flight would not have been attempted from Love Field. The fact that the engines were reported to function normally on occasions, while checking unsatisfactorily at times, has been considered, however the exact nature and cause of the reported loss of power can not be determined. Exact time that the aircraft was on the ground at Hensley Field, prior to take-off, could not be determined, however it was found that considerable taxiing was necessitated and there was a delay in take-off due to congested traffic. Whether or not a pre-flight power check was run prior to the take-off is not known.

All facts and findings, as set forth above, have been reviewed and it is the opinion of members of this Aircraft Accident Investigating Board that reported engine functions indicate that both engines were “loaded up” on take-off, due possibly to excessive rich mixture. Though it was found that the left propeller was feathered, it is believed that a similar malfunction was experienced in both engines, and that sufficient power could not be attained in the right engine to sustain single-engine flight.

It is concluded that take-off power failure, of this nature, could be fore-seen and avoided by the execution of a normal pre-flight power check and the proper manipulation of power controls.

It is recommended that the importance of pre-take-off power checks be stressed, regardless of the condition of aircraft engines, and that special attention be given to engine run-up and power checks after extended ground operations, which might be conducive to “loading up” of engines.

________

The Report also includes this letter to the Post Safety Officer, which goes into detail about Captain Arbib’s experience an proficiency, concluding that, “Captain Arbib’s ability as a pilot and his flying record was considered above average by the undersigned.“

16 July 1945

TO: Flying Safety Officer, Post

FROM: Flight Training Office

SUBJECT: Captain E.J. Arbib, information concerning

1. Captain Edmond J. Arbib was assigned to Transition on personnel memorandum number 148 – 23 June, 1945, as a pursuit A-26 instructor.

2. The above mentioned pilot was given an instructor’s flight check ride in B-25 ship and was found highly satisfactory. This pilot had one thousand (1000) hours first pilot time – five hundred (500) hours of which was in C-46s, one hundred hours in B-25s, one hundred (100) hours in B-24s, eighty (80) hours in P-38s, and two hundred and twenty (220) hours single engine pursuit. Subject Officer was formerly a check pilot on B-24 type aircraft at Romulus, Michigan and held a white instrument card with two hundred and fifty (250) hours instrument time. Pilot was not involved in any accident due to pilot error.

3. Captain Arbib was given an original A-26 check at this Station on 13 May, 1945. After the original check, Captain Arbib spent twelve (12) hours on A-26s under the supervision of the Pursuit Flight Commander. This time consisted of extensive single engine work, both on take-offs and landings – practically all landings were completed under the supervision of an A-26 instructor or the Flight Commander.

4. Captain Arbib’s ability as a pilot and his flying record was considered above average by the undersigned.

/s/ A.E. Probst

A.E. Probst

1st Lt., AC

Pursuit Flight Commander

A TRUE COPY

Wilbur G. Shine

WILBUR G. SHINE

Captain, Air Corps

____________________

United States Army Air Force

12th Air Force

Though the war in Europe had ended, Army Air Force training missions continued regardless. On July 12, during a simulated dive-bombing mission of an airdrome at Augsburg, and, a simulated strafing mission of buildings at the Ammersee (Ammer Lake), First Lieutenant Fred B. Schwartz (0-2057031) was killed when his P-47D Thunderbolt fighter, aircraft 42-26718 (squadron identification letter “C” or “O“) struck the surface of the Ammersee and sank. The incident was reported in Missing Air Crew Report 14953.

A member of the 522nd Fighter Squadron, 27th Fighter Group, 12th Air Force, Lt. Schwartz, born on May 6, 1924 in McKeesport, Pa., and was the son of John and Lillian (Gelb) (10/13/93 – 1/3/83) Schwartz of 628 Petty Street. His sister was Velma Feldman, who in 1945 resided at 1629 Cal. Avenue, in the White Oak section.

His name appearing on page 550 of Volume II of American Jews in World War II, Lt. Schwartz had been awarded the Air Medal and two Oak Leaf Clusters, suggesting that he’d flown over 10 combat missions prior to the war’s end. He is buried at the Luxembourg American Cemetery at Plot H, Row 4, Grave 47.

As well as in MACR 14953, information about this incident can be found at Aviation Safety Net, and, the 12 O’Clock High Forum. The story of the plane’s loss and eventual recovery and salvage was reported upon by Gerald Modlinger in the Augsburger Allgemeine on April 16, 2009 and June 5, 2010, though as of now – 12 years later, in 2022 – those two articles, the latter including a picture of the salvaged P-47, are behind paywalls. (Oh, well.) But – ! – when I first researched this story some years ago, these articles were still openly available and I was able to copy and translate them. So, they appear below, accompanied by an air photo of the Ammersee.

________

Here’s the shoulder-patch of the 12th Air Force…

…while this image of the emblem of the 522nd Fighter Squadron is from Popular Patch.com.

Here are two representative depictions by illustrator Chris Davey of 522nd Fighter Squadron Thunderbolts, as seen in Jonathan Bernstein’s P-47 Thunderbolt Units of the Twelfth Air Force. A single letter on the mid-fuselage serves as a plane-in-squadron identifier on these otherwise simply marked aircraft.

This painting is of P-47D 42-26444, “Candie Jr.“, “E“, flown by Lt. Robert Hosler, in December of 1944…

…while this painting shows P-47D 44-20856 “BETTY III“, “O“, of 1 Lt. Robert Jones, as the aircraft appeared in early April of 1945.

________

Pilot Rests in Cemetery in Luxembourg (“Pilot-ruht-auf-Friedhof-in-Luxemberg”)

When a quiet solitude had entered Lake Ammersee in November, a lonely watercraft was sailing on the lake. An American explorer was viewing sonar for an aircraft that crashed shortly after the end of the war.

Gerald Modlinger

April 16, 2009

Diessen – When a quiet solitude on Lake Ammersee arrived in November, a lonely watercraft was on the lake. An American explorer was viewing sonar for a plane that crashed shortly after the end of the war, and especially for the pilot who was killed. Aerospace researcher Josef Köttner from Diessen has now researched that the pilot who he has been looking for has been resting in a US military cemetery in Luxembourg for decades.

Bob Collings, director of the company, emailed last November when he told how moving it was when members of the family were given certainty about the mortal remains of their fathers and grandfathers who had been killed in the war. The search campaign on the Ammersee also returned to a request from the descendants of the missing US soldier. At the same time, the courthouse also issued the necessary permits for the exploration.

In order to clarify the fate of the pilots killed in the crash of the P-47 Thunderbolt on July 12, 1945, however, the elaborate search action would obviously not have been necessary. After an Internet investigation and a request from the US Air Force, 79-year-old Köttner is clear about the incident and the fate of the killed pilot.

The crashed P-47 Thunderbolt was piloted by Fred B. Schwartz, a member of the US Air Force’s 522th Fighter Squadron. This unit was stationed in Sandhofen near Mannheim in the summer of 1945. From the accident report and the reports of pilots of other combat aircraft it is clear that on 12 July 1945 at 9:40 am, four P-47 Thunderbolt machines from Sandhofen flew to a practice site on an airfield south of Augsburg and then aimed at a row of houses on the Ammersee as targets. At about 11 o’clock an airplane’s propeller tips came into contact with the surface of the water. The pilot had misjudged the situation. The plane pulled up again, then fell to the water on the south-east of Lake Ammersee and sank after a few seconds without the pilot leaving the aircraft. The remaining three P-47s still circled around the crash site for some time and then returned to their base.

Meanwhile, a boat had arrived at the crash site, but at that time the plane had already sunk in the water, at a point where the lake is about 45 meters deep. A buoy was installed as a marker.

Afterwards a company from Regensburg was assigned to recover the wreckage of the aircraft. There is nothing else to read in the accident report. On an American website, on which the overseas soldiers’ residences are listed, Köttner finally found himself in search of the fallen Lieutenant Fred B. Schwartz. The pilot, who came from Pennsylvania, found his final place of rest at the military cemetery in Luxembourg.

In the meantime, nothing has been known about the findings gained during the days-long search on the Ammersee. “We are also surprised that we have not heard anything at all,” said Wolfgang Müller, the courthouse’s spokesman yesterday regarding the Lieutenant. Furthermore, the employees of the water authority would be interested in the findings of the Americans about the conditions on the bottom of the lake.

Without giving any details, Bob Collings and Bob Mester had told the search company Underwater Admiralty Sciences (UAS) about the wreckage of cars, boats and craters their sonar had encountered. Whether or not they found the plane they were looking for, remained open.

__________

The P-47 Was Already Salvaged in 1952 (“Die P-47 wurde schon 1952 zerlegt”)

Gerald Modlinger

June 5, 2010

Diessen – The aircraft search by an American company one and a half years ago at the Ammersee was probably not only with regard to the unfortunate pilot, but also with regard to his aircraft from the start without certainty. The underwater archaeologist Lino von Gartzen from Berg reports in the magazine Flugzeugclassic that the airplane wanted by the Americans already 1952 from the Ammersee had been salvaged. Previously, Lachen avocational researcher Josef Köttner had already shown that the pilot who had been killed on July 12, 1945, has been lresting in an American military cemetery in Luxembourg for decades.

This picture shows the salvage of the P-47 Thunderbolt near St. Alban in the spring of 1952. The American search team arrived 56 years too late to find it still.

Photo: 1952 Ludwigshain / Collection of Gartzen

Photo: 1952 Ludwigshain / Collection of Gartzen

This Wikimedia Commons image of the Ammersee is by Carsten Steger.

The fact that there are probably no more aircraft in the southern Bavarian lakes today is mainly due to Ludwiging, a native of Inning, who reported on Gartzen in October 2009 in Flugzeugclassic.

Ludwigshain (1920-2009) had been trained in the Second World War by the Navy in Norway as a salvage dredger. One needed such people among other things, in order to be able to lift airplanes, which were sunk by saboteurs in the harbor. His knowledge remained useful to Hain after the end of the war. With a partner he began to retrieve aircraft which had fallen into the Bavarian lakes. When he had fished the lakes largely empty, he went to Lake Constance, where he died in the spring of 2009.

All metal was strongly sought in the 1950s

It is today the high antiquity of historical aircraft wrecks that arouses the interest in them, making after the Second World War the scarcity, especially in metals, of aircraft wrecks to worthwhile companies. It was only in the early 1960s that such [wrecks] became gradually uninteresting, as the price of scrap metal fell sharply.

In southern Bavaria, Hain with his partner Schuster, among other things [found] a British Lancaster, a B-17, a Bf-109 and two P-47 Thunderbolts, besides various vehicles, boats, a mini-U-boat and heavy bridge parts, writes Gartzen, after a conversation he had had with Hain shortly before his death.

The eye-witnesses did not agree on the type of aircraft

Ludwigshain found one of the two American P-47 Thunderbolt machines taken from the Ammersee in the spring of 1952. The Landsberger Tagblatt had already been mentioned by Rolf Haunz in November 2008 for this aircraft. The Kaufbeurer spent his childhood in Diessen and was a witness to the spectacular flight of aircraft in front of St. Alban. Haunz said at the time that it must have been a P-47. However, other people who saw children as the plane was landed could not confirm this with certainty.

According to Gartzen, “99.99 per cent” of Ludwigshafen’s photographs made it clear that in 1952 the P-47, which was sought again a year and a half ago, was taken from the Ammersee. The serial number was exactly what the Americans were looking for. The cockpit of the P 47 was closed, indicating that the aircraft pilot could not leave his machine. In addition, the time of the salvage coincided with the identification of missing pilot Fred B. Schwartz in April 1952.

After the plane was pulled ashore, it was disassembled. The parts were transported by truck and train. Crashed airplanes were a real treasure in the 1950s: Gartzen knows of a case in which such an aircraft produced 25,000 marks. “That was the value of a family home.”

____________________

United States Army Air Force

5th Air Force

Though combat missions had ended for the Army Air Force in the European Theater, they would continue without respite in the Pacific for four more months.

On one such mission, – to destroy oil storage tanks at Toshien, Taiwan (formerly Formosa) – B-24M Liberator 44-50390 “Becomin’ Back” of the 528th Bomb Squadron, 380th Bomb Group, piloted by Major Kenneth E. Dyson, was struck by three or four bursts of 90mm anti-aircraft fire. Of the plane’s 11 crew members, there would be six survivors. Second Lieutenant Eugene Stark (0-2024001), the bombardier, would not be among them. He was seen to bail out by T/Sgt. Edward Treesh, the flight engineer, but was not seen afterwards. The plane’s loss is described in MACR 14921.

The son Martin and Julia (10/27/98-7/21/90) Stark, of 950 Aldus Street in New York City, Lt. Stark would be the recipient of the Air Medal, 1 Oak Leaf Cluster, and Purple Heart, indicating that he’d completed between five and ten combat missions. His name appeared in official casualty lists on August 8 and October 3, 1945, and can be found on page 453 of Volume II of American Jews in World War II.

The plane’s crew consisted of:

Dyson, Kenneth E., Major – Pilot (Killed – Not recovered)

Muchow, Robert Leonard, 2 Lt. – Co-Pilot (Rescued)

Flanagan, Michael J., Jr., 1 Lt. – Navigator (Killed – Buried at sea)

Stark, Eugene, 2 Lt., Bombardier (Killed – Not recovered)

Bongiorno, Thomas G., F/O – H2X Navigator (Killed – Not recovered)

Treesh, Edward Oren, T/Sgt. – Flight Engineer (Rescued)

Nagel, Lawrence J., T/Sgt. – Radio Operator (Rescued)

Latta, William E., S/Sgt. – Gunner (Rescued)

Heffington, James C., S/Sgt. – Gunner (Killed – Not recovered)

Wood, Albert W., S/Sgt. – Gunner (Rescued)

Dalton, Maurice G., S/Sgt. – Gunner (Rescued)

__________

This image of the 528th Bomb Squadron insignia is from the MASH Online military clothing and insignia store.

__________

The Missing Air Crew Report for the plane’s loss includes detailed eyewitness statements by all six survivors – 2 Lt. Muchow, S/Sgt. Latta, T/Sgt. Treesh, S/Sgt. Dalton, T/Sgt. Nagel, and S/Sgt. Wood – of which S/Sgt. Dalton’s is by far the longest and most detailed. Notably, the only survivor from the front of the plane was Lt. Muchow. The last of the survivors to be rescued, he was picked up from the sea by a Martin PBM Mariner. Here’s his account of the loss of “Becomin’ Back“:

528TH BOMBARDMENT SQUADRON (H) AAF

APO # 321

19 JULY 1945.

EYEWITNESS DESCRIPTION OF CRASH

On July 12, 1945, we were on a mission to Toshien, Formosa to knock out some oil storage tanks in the northeast corner of the town. We were lead ship of the second squadron. Instead of making the planned bomb run, Major Dyson asked the H2X Operator for a direct heading to the target from that position which we later found out to be north of the prescribed bomb run and directly over a battery of 90mm anti-aircraft guns. After starting on the bomb run I could see a solid barrage of ack-ack about a mile in front of us and at out altitude. It appeared at the time that our evasive action was insufficient an then we were hit.

I remember only one burst close in on the left side of the plane. This burst shattered the pilot’s window, injured Major Dyson, shot out the auto-pilot and burst the hydraulic lines in front of my feet. I immediately called the engineer and asked him to check the leaking gas. I then asked Major Dyson how bad he was hit. I could see he had superficial cuts about the face and he added that his left arm or side was hit. The blast had blown off his earphones and mike and he was very dazed. I was dazed enough that the one burst is all I recall, later I found out we received three or four.

I switched to “D” Channel and tried to contact the submarine, to no avail. I finally switched to “B” Channel and contacted a fighter plane who in turn gave me the sub’s position. I looked back then and the leaking gas in the bomb-bay looked like a solid sheet of rain. The fumes had penetrated the plane and we were all affected to a certain degree. We had the side windows open up front so were lucky in that respect.

I asked Sgt. Wood to get me the navigator and when I finally made him look my way he just laughed in my face. H was like a drunk from the gas fumes and so too, were the others on the flight deck. This, helped account for the dazed reactions of all of us.

All this time Major Dyson just sat with a dazed expression on his face, said nothing, and flew the ship by instinct, I thought, than from realization, of the situation. Or ordered us to bail but we were too close inshore and continued to the submarine. Several times I took the ship and turned it back toward the sub when Major Dyson turned back toward Formosa.

The ship was running okay from the recordings of the instruments and our main worry was losing an engine. We were headed toward the sub and loosing altitude at about three hundred (300) feet per minute. We were hit while at about 13,000 feet. The first man bailed out at about 10,000 feet and I bailed out at about 8,500 feet. I was the last man to leave the ship. Before Lt. Flanagan bailed out he told me he was going. I asked if all had bailed and ‘chutes opened and he said they had. I left soon after he did and thought Major Dyson would follow me. After my ‘chute opened I saw the ship just before it hit the water. It had apparently lost an engine and gone in on a wing. The men on the sub said it started burning before hitting the water, then blew up.

The following was taken from the Log of the U.S.S. Cabrilla (SS-288), the submarine that picked us up.

July 12

1140, received word that plane was going to be ditched.

1145, sighted seven ‘chutes in the air.

1210, picked up Dalton, M.G.

1212, picked up Wood, A.W.

1302, picked up Flanagan, M.J.

1331, picked up Treesh, E.O.

1400, picked up Latta, W.E.

1404, picked up Nagel, L.J.

1422, picked up Muchow, R.L.

1640, buried Lt. Flanagan, M.J. at sea, Goron Bi, Formosa, baring 036 T, distance fifteen (15) miles

Robert L. Muchow

ROBERT L. MUCHOW,

2nd Lt., Air Corps,

Co-Pilot, 528th Bomb Sq.

380th Bomb Gp (H).

__________

This image of the nose art of Becomin’ Back can be found at the website of the 380th Bomb Group (the “Flying Circus“), in the historical profile of B-24M 44-50390.

__________

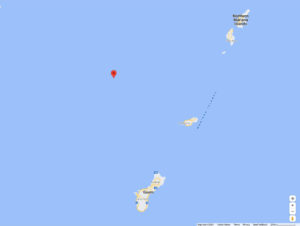

Here’s the 1945 map from MACR 14921 showing the approximate location of the loss of Becomin’ Back…

…while here’s a 2021 Oogle Map showing the crash location, based on longitude and latitude coordinates as listed in the MACR.

____________________

United States Army Air Force

20th Air Force

During the early evening hours of July 12, 1945, the 20th Air Force’s 16th Bomb Group incurred its first combat loss. This happened during the start of a night mission to “Kawasaki”, the name probably meaning the city of Kawasaki, in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. At approximately 1935 to 1940 hours K (kilo)* time, not long after taking off from Guam, three of the four engines of the 16th Bomb Squadron B-29 42-63603 ran away, and, the engines’ propellers could not be feathered.

As the aircraft descended rapidly from 4,500 feet, aircraft commander Lt. Milford Berry ordered his crew to bail out. Though it will never be known if Lt. Berry himself escaped the descending plane, all other crew members in the B-29’s forward section left the airplane.

In the rear crew compartment, all crew members left their bomber with the exception of right blister gunner S/Sgt. Harold I. Schaeffer and tail gunner Sgt. Philip Tripp.

Of the eight men known to have parachuted from their B-29, only three survived: pilot 2 Lt. James Trivette, Jr., bombardier 1 Lt. Rex E. Werring, Jr., and left blister gunner Sgt. Clarence N. Nelson. Four of the other five crewmen were never found. However, Sgt. Tripp’s body was recovered; he is buried at Forest Dale Cemetery in Malden, Massachusetts.

Among the crew members of 42-63603 was Sergeant Morton Finkelstein (32977132) the bomber’s flight engineer. Born in a placed called Brooklyn on June 22, 1925, he was the son of Edward E. (1/30/01-5/21/83) and Rose (Lubchansky) (1900-1/24/85) Finkelstein, their family residing at 32 Joralemon Street.

His name appeared in casualty lists published on August 15, 1945 and April 21, 1946, and can be found on page 309 of American Jews in World War II, where he is recorded as having received the Air Medal and Purple Heart. Like the other four missing crew members, his name can be found in the Tablets of the Missing at the Honolulu Memorial.

(Kilo Time Zone is often used in aviation and the military as another name for UTC +10. Kilo Time Zone is also commonly used at sea between longitudes 142.5° East and 157.5° East.)

__________

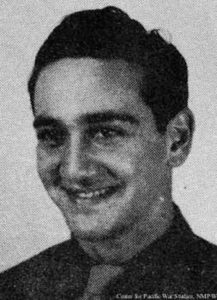

This image of Sgt. Finkelstein, at the archives of the National Museum of the Pacific War, at Fredericksburg, Texas, was uploaded to FindAGrave by Chris McDougal.

__________

Here’s the Record of Casualty for Sergeant Finkelstein, completed by Chaplain Bernard J. Gannon and provided to Major David I. Cedarbaum. This document is from the Honor Roll in the Cedarbaum Files (Folder 5) at the American Jewish Historical Society.

As stated in the Record of Casualty:

“The plane in which Finkelstein was riding was commanded by Lt. Milford A. Berry. At least a portion of the crew bailed out. Finkelstein is known to have left the plane. The plane had three run-away engines and exploded a few feet above the water. Three men were recovered, one body [Sgt. Tripp] was buried at Saipan the identity of which was known.

It is understood that prayers for soldier’s safety were included in your service at the 73rd Air Service Group Chapel, 15 July 1945.”

__________

A symbolic matzeva for Sgt. Finkelstein appears in this image by FindAGrave contributor Mary Lehman. It’s located at Mount Golda Cemetery in South Huntington, New York.

__________

The crew of 42-63603:

Berry, Milford Audrain, 1 Lt. – Aircraft Commander (Last seen in aircraft)

Trivette, James, Jr., 2 Lt. – Pilot (Rescued)

Rollins, K. Warren, 1 Lt. – Navigator (Last seen bailing out)

Werring, Rex E., Jr., 1 Lt. – Bombardier (Rescued)

Ameringer, Irving W., 2 Lt. (Last seen bailing out)

Finkelstein, Morton, Sgt. – Flight Engineer (Last seen bailing out)

Lynch, Robert E., Sgt. (Last seen bailing out)

Schaeffer, Harold I., S/Sgt. – Gunner (Right Blister) (Last seen in aircraft)

Nelson, Clarence N., Sgt. – Gunner (Left Blister) (Rescued)

Tripp, Philip Gregory, Sgt. – Gunner (Tail) (Killed (see Cederbaum report)

__________

A flying, bomb-carrying, world-spanning hippo is the central motif of the insignia of the 16th Bomb Squadron, in this image from Pinterest, uploaded by Nikolaos Paliousis.

__________

Here’s a partial transcript of post-war “fill-in” Missing Air Crew Report 15373, which covers the loss of 42-63603:

Time and position of bailout: 1934K, 12 July 1945, approximately 80 miles north of western tip of Orote Peninsula, Guam. Coordinates: 14-36 N, 114-25 E.

The aircraft acted properly during take-off (1940 K) and climb. After leveling off at 6,200 feet, RPMs were reduced but No. 1 engine remained at 2400. The Airplane Commander reduced the RPMs of No. 1 engine to 2000 with the feathering button. Almost immediately however it increased and went wild. The Airplane Commander hit the feathering button but it had no effect, so he pulled the throttle back, told the Bombardier to salvo the bombs and headed for Guam. On the turn, No. 3 engine started building up and again the feathering button was ineffective. The Airplane Commander gave the order to prepare to ditch. Almost immediately, No. 4 engine ran away and the order to bail out was given. The altitude was about 4500 feet, and the aircraft was dropping at about 1000 feet per minute. The Pilot took over the plane was the Airplane Commander fastened his parachute and one-man life raft. The Pilot rang the alarm bell and called the left scanner and tail gunner on the interphone.

The airplane commander attempted to transmit on VHF channel, but it appeared to be dead. He then switched to Channel A. Bombardier reported that Pilot was not getting out on this channel. Also, no word has been received of receipt of any message by any aircraft or ground station.

Bail out:

Exit through forward bomb bay:

The Navigator and Radio Operator went out first (order unknown), and their chutes were seen to open by the Bombardier who was third out. The Radio Operator hesitated but left sometime between the time the Bombardier and Pilot bailed out. The Pilot was next out and saw one chute open just before he left the airplane. With the exception of the Airplane Commander, the front of the airplane was clear when he left, and the altimeter indicated 500 feet. No difficulty was experienced in leaving the hatch. The Bombardier and Pilot put their hands along the edge of the bulkhead door and dove out in one motion.

Exit through rear bomb bay:

The Right Scanner had been briefed to bail out first and was fully geared and ready to go. The Left Scanner motioned him out but he (Right Scanner) “looked blank”. The Left Scanner then asked him to step aside so he (Left Scanner) could go out, thinking that by so doing the Right Scanner might gain confidence. The Right Scanner stepped aside, still mute, and the Left Scanner dove out the pressure bulkhead door. The Right Scanner was never seen to leave the airplane.

Altitude and time for Bail Out:

Between 1500 feet and 500 feet. Time interval approximately 1 ½ minutes between first and last man.

Like some other MACRs for B-29 crews whose members were rescued after parachuting over, or ditching in, the Pacific Ocean, the document accords much attention to the many factors involving aircrew survival, in terms of bailout procedure, safely parachuting, use of a one-man life raft (in terms of deployment, inflation, and how-to-actually-successfully-get-into-the-raft in the first place), physical and psychological factors involved in survival at sea, and, attracting the attention of searching vessels and aircraft.

What’s notable about the bailout from 42-63603 is that this occurred at about 7:40 at night (civilian time). Given that sunset in the Kilo Time Zone on July 12, 1945 would have occurred at 8:30 P.M., the crew would have had less than an hour of light before the arrival of total darkness. At sea; alone.

__________

Akin to the Oogle map illustrating the loss location of Becomin’ Back, this map shows the loss location of B-29 42-63603.

__________

This cutaway image from Boeing’s B-29 Maintenance and Familiarization Manuel (HS1006A-HS1006D) shows the interior arrangement of a B-29’s forward crew compartment. The location of the flight engineer’s station, on the right side of the compartment, is directly behind the co-pilot.

This panoramic 360-degree-view, at 360Cities, gives a high resolution, clear view of the B-29’s front crew compartment. Upon going to the link you’ll arrive at a view of the interior of a B-29’s forward crew compartment, facing forward. Rotate the view 90 degrees to the right (use the right arrow), and you’ll see the flight engineer’s station with it’s small myriad of dials and switches, as well as throttle leavers.

__________

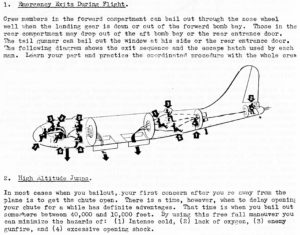

The following diagram, from the XXI Bomber Command Combat Crew Manual, specifically Section XII – “Emergency Procedures” – depicts the sequence by which the members of a Superfortress crew were to bail out of their bomber during an in-flight emergency.

In the nose, the bailout sequence was: 1) bombardier, 2) flight engineer, 3) co-pilot, 4) navigator, 5) radio operator, and 6, pilot. Escape could be made through a hatch in the cockpit floor situated directly above the nose wheel (by definition, necessitating that the nose wheel be lowered), or, through the bomb bay, the latter option requiring that the crew compartment to be depressurized so that the bomb bay could be accessed through a circular hatch.

____________________

British Army

Died while Prisoner of War

The fact that four of the five servicemen mentioned in this post were aviators, all members of the United States Army Air Force, is a coincidence of the timing of July 12, 1945. The war in Europe had ended on May 8 (or May 9, in the former Soviet Union), and combat, as such, was now only occurring in the Pacific Theater. Along with Captain Arbib, Lieutenants Schwartz and Stark, and Sgt. Finkelstein, the fifth (known) Jewish soldier who was a casualty on July 12 was – as mentioned in the “intro” to this post – a member of the British Army. Probably captured during the fall of Java on March 12 1942, he was Gunner Solomon Rosen (1827101).

Born in 1914, he was the husband of Henrietta Rosen, of Heathway, Dagenham, Essex, and the son of Sam and Annie. A member of the 78th Battery, 35th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, he arrived in Singapore aboard the ship Nishi Maru on September 14, 1942, and then in Kuching, Borneo, aboard the Hiteru Maru on October 9 of the same year.

It was there that he died, in tragic irony only a little over one month before the end of the Second World War. Then again, more than a few POWs of the Japanese succumbed to illness, starvation, mistreatment, or appallingly worse, through and even after the last day of hostilities in the Pacific Theater of War. (Such, as…)

Gunner Rosen, whose name appears on page 148 of Volume I of Henry Morris’ We Will Remember Them, is buried at the Labuan War Cemetery, in Malaysia; Plot N,C,6. His name appears in the Roll of Honor – Java Index.

Gunner Rosen’s matzeva, with the Hebrew abbreviation .ת.נ.צ.ב.ה. (Tehé Nafshó Tzrurá Bitzrór Haḥayím – May his soul be bound up in the bond of life) inside the Magen David, appears in this photo by FindAGrave contributor GulfportBob.

References

Bernstein, Jonathan, P-47 Thunderbolt Units of the Twelfth Air Force, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, New York, N.Y., 2012

Dublin, Louis I., and Kohs, Samuel C., American Jews in World War II – The Story of 550,000 Fighters for Freedom, The Dial Press, New York, N.Y., 1947.

Mireles, Anthony J., Fatal Army Air Forces Aviation Accidents in the United States, 1941-1945 – Volume 3: August 1944 – December 1945, McFarland & Company Inc., Publishers, Jefferson, N.C., 2006

Morris, Henry, Edited by Gerald Smith, We Will Remember Them – A Record of the Jews Who Died in the Armed Forces of the Crown 1939 – 1945, Brassey’s, United Kingdom, London, 1989

Rust, Kenn C., Twelfth Air Force Story, Historical Aviation Album, Temple City, Ca., 1975

No Specific Author Listed

XXI Bomber Command Combat Crew Manual, A.P.O. 234, May, 1945 (reprint obtained via EBay)

Jonas Phillips (wikipedia), at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jonas_Phillips