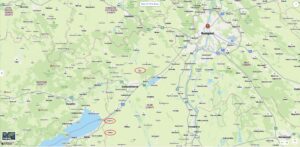

Every man’s life is a tapestry of stories, the majority mundane, some startling and dramatic; some traumatic and transformative; and a few – on rare occasion – inspiring by the very magnitude of their impact. Such were the wartime experiences of First Lieutenant Bernard William Bail (0-807964), who served as a radar navigator in the 66th Bomb Squadron of the 8th Air Force’s 44th Bomb Group.

______________________________

…the insignia of the 66th Bomb Squadron (via US Wars Patches)…

______________________________

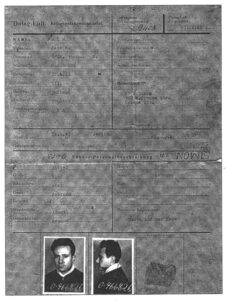

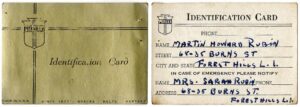

The son of Abraham (3/10/87-7/6/68) and Lillian “Lily” (Miller) (11/3/95-9/28/89) Bail and brother of Private Paul Bail of 2330 South 6th St., in Philadelphia, he was born in that city on November 18, 1920. For the purposes of emergency correspondence, his official contact in the United States was his uncle, Dr. Harry Bail, his who resided at 2547 North 33rd St. in the same city.

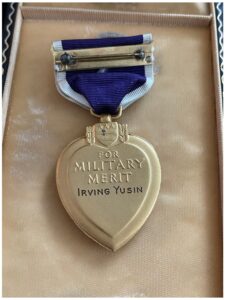

The recipient of the Air Medal with three Oak Leaf Clusters and Purple Heart, his name appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer and Philadelphia Record on May 4 and 3, 1945, respectively. Though his name can be found on page 509 of American Jews in World War II, oddly, absolutely nothing about him ever appeared in wartime issues of The Jewish Exponent, which was (and is) published in that Pennsylvania city.

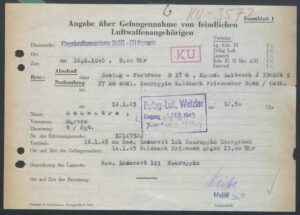

As the radar navigator aboard the 66th Bomb Squadron’s un-nicknamed B-24J Liberator 42-51907 (QK * B+) during the 44th Bomb Group’s March 19, 1945 mission to an Me-262 factory at Neuberg, Germany, Lieutenant Bail was one of the aircraft’s three eventual survivors – from its crew of eleven – after the plane, piloted by 1 Lt. Robert J. Podojil, was shot down by German fighters in the vicinity of Stuttgart, an event covered in Missing Air Crew Report 13574. The very sparse outline of this story is alluded to in the following article from the Philadelphia Inquirer of May 4, 1945. The article also makes reference to Lt. Bail having previously bailed out over the English Channel, about which much (…much…(much!)) more follows further “down” this post.

The text of the article:

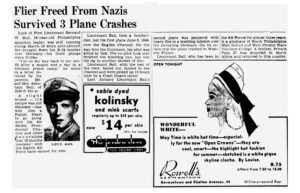

Flier Freed From Nazis Survived 3 Plane Crashes

Luck of First Lieutenant Bernard W. Bail, 24-year-old Philadelphia squadron leader, was still running strong March 19 when anti-aircraft fire brought down his B-24 bomber over Germany – his third plunge since D-Day.

“I’m on my way back to my outfit after a month and a day in a German prison camp,” he wrote in a letter received by his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Abraham Bail, of 2330 S. 6th St.

A slight wound – its nature was not disclosed – has won him a Purple Heart to go along with his Air medal, Presidential Citation and other decorations that 16 months overseas service with the Eighth Air Force have earned for him.

Lieutenant Bail, then a bombardier, lost his first plane June 6, 1944, over the English Channel. On the way into the Continent, his pilot was killed by flak. The co-pilot took over finished the bombing run, but lost his leg in another shower of fire.

Lieutenant Bail, with the rest of the crew, bailed out, landed in the Channel, and were picked up 13 hours later by a Coast Guard cutter.

Last January Lieutenant Bail’s second plane was peppered with heavy fire in a bombing mission over the retreating Germans. On its return trip the plane crashed in Western France.

Lieutenant Bail, who has been in the Air Forces for almost three years, is a graduate of South Philadelphia High School and West Chester State Teacher’s College. A brother, private Paul, 27, was wounded in North Africa and returned to this country.

Here’s the article itself, accompanied by two advertisements that give a random “flavor” of the era…

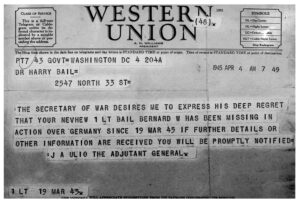

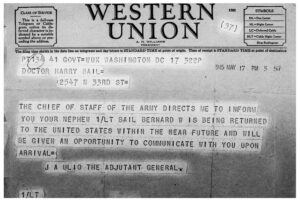

Though Dr. Bail passed away in 2021, his personal website – Bernard W. Bail M.D. – is fortunately still very much “up and running”. His curriculum vitae includes some images and documents from his wartime service, including the Western Union telegrams informing his uncle of his missing in action status, and then, his imminent return to the United States (dated April 4 and May 17, respectively).

Here they are:

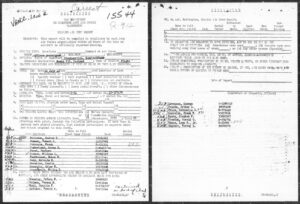

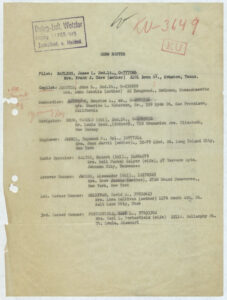

Here’s the crew of 42-51907…

Pilot – Podojil, Robert J., 1 Lt.

Co-Pilot – Ritter, Frederick M., 2 Lt.

Navigator – Chase, Dudley S., 2 Lt.

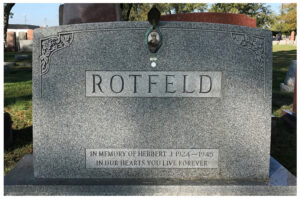

Radar Navigator – Bail, Bernard W., 1 Lt. – Survived (11/18/20-1/26/21)

Bombardier – Crane, Walter W., 2 Lt.

Flight Engineer – Reichenbach, Theodore H., T/Sgt.

Radio Operator- Veitch, Max F., T/Sgt. – Survived (9/23/24-12/4/08)

Gunner (Nose) – Clark, William N., Jr., S/Sgt.

Gunner (Right Waist) – West, John W., S/Sgt.

Gunner (Left Waist) – Mosevich, Walter F., S/Sgt. – Survived

Gunner (Tail) – Schmitz, Norbert J., S/Sgt. – Died of wounds while POW (See here and here)

An uploaded to Ancestry by Kasie Podojil on August 22, 2023, this photo shows the Podojil crew. The men aren’t identified, but I’m certain that Lt. Podojil is one of the men in the front row. Not being a regular member of the crew, Lt. Bail wouldn’t be in the picture. Close examination of the data block and three digits on the forward fuselage reveal that this plane is B-24J 42-50807, which is solidly confirmed via Aviation Archeology.

______________________________

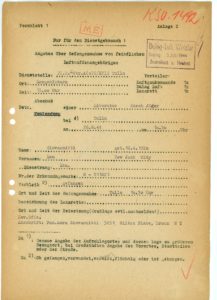

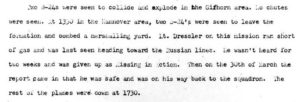

Given the time-frame, though it might be assumed that there’d be an abundance of information about the loss of QK * B+, but strangely there is not. No Luftgaukommando Report – if there even was one – for this incident survives, and, Jan Safarik’s compilation of Luftwaffe fighter victories against B-24s has no entries for this date. In the missing Air Crew Report, observations by other airmen in the 66th are equally enigmatic. The report states: “Very little is known as to exactly what happened to this crew. On this mission six aircraft were originally carried as “not yet returned”, five of which have returned to base. All five of these returned aircraft had left the formation after bombing and landed on the Continent, having run short of gas. At 1503 hours this crew was heard from at a point approximately ten (10 miles southwest of Stuttgart and fifty-five (55) miles east of bombline, at which time the pilot thought he would be able to make it to friendly territory. At this time he was observed to have two (2) feathered engines. No further word was heard over VHR and no additional information has been received at this headquarters.”

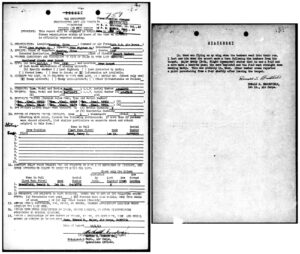

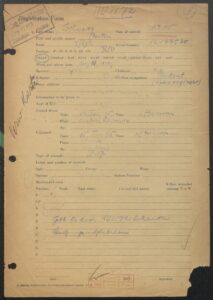

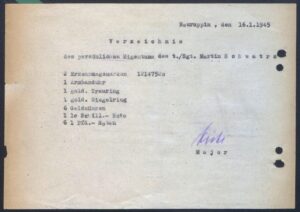

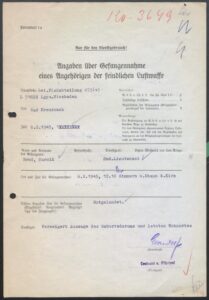

Documents in the MACR – a statement made by Sgt. Mosevich in Miami on August 31, 1945, and, Casualty Questionnaires completed by the three survivors – yield a reconstruction of what befell 42-51907 and her crew: The plane’s #3 engine suffered a loss of power prior to reaching Neuberg due to a loss of oil pressure, with the #1 failing for the same reason after the bomb run. Lagging behind and unable to maintain formation with the rest of the 44th, Lt. Podojil ordered his crew to jettison the plane’s machine guns, ammunition, and other equipment. The defenseless bomber was then shot down by German fighters in an attack that must have been as sudden as it was overwhelming, this eventuating in four airmen abandoning the bomber from 15,000. As Sgt. Mosevich stated in his Casualty Questionnaire form for Lt. Podojil, “The fighter planes attacked us very suddenly, it all seemed to be over in a few seconds.” In his summary Casualty Questionnaire, he wrote that Sgt. Veitch opened the bomb bay doors through which Veitch and Bail jumped, while Mosevich himself jumped out the port waist window. How Sgt. Schmitz escaped the plane is not mentioned; I’d assume through the jettisonable lower tail hatch.

Despite what is reported from other sources (see below…) Sgt. Mosevich saw only three other parachutes in mid-air, and recalled that Clark, Crane, and West didn’t have their parachutes attached when he left the plane.

The conclusion to be drawn from the MACR is that – with the exception of Sgt. Schmitz – none of the seven other crewmen were able to escape the aircraft.

This parallel’s Lt. Bail’s statement in 44th Bomb Group Roll of Honor and Casualties: “On my 25th mission our plane was jumped by a couple of ME 109s. The entire crew, with the exception of four of us, was killed over Germany near Stuttgart. The tail gunner, S/Sgt. N.J. Schmitz, sustained a leg injury that necessitated amputation of his leg, which I witnessed. I, myself, was wounded in my head and neck. The young tail gunner [Schmitz] later died of gangrene. I was present at his burial in the little town of Goppingen.”

______________________________

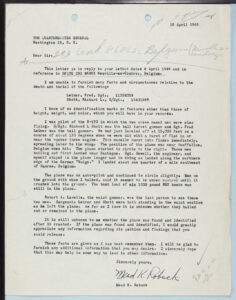

Here’s Lt. Bail’s reply to Major W.R Reed of the Air Corps’ Notification Branch, concerning the latter’s inquiry of June, 1945, pertaining to Lt. Ritter (co-pilot) and Sgt. Clark (nose gunner):

Tuesday – Sept 1945

Dear Major Reed,

I have received your letter asking about Lts. Ritter, Chase, and Crane and Sgts. Reichenbach, West and Clark.

I have written to various depts. already the fact that all of the above men are dead.

The mission was on March 19, 1945 to Ingolstadt; we were attacked on the way back by the Luftwaffe.

The men listed above were unable to get out of the plane, which went down, burning; so it is sure all of them died.

I have written fully to other departments as I’ve said. Should you want further information, I shall be glad to answer any questions you may have.

Sincerely

Bernard W. Bail

Lt. Bail’s letter, as it appears in the MACR:

______________________________

Accompanying Sgt. Mosevich’s Casualty Questionnaire forms in the MACR is this very brief summary of his escape from 42-51907:

Additional Inf:

We were flying on two engines and we had abandoned our guns and ammunition. Our fighter escort hadn’t arrived. German fighters attacked suddenly. When I bailed out the plane seemed to be starting into a spin. As I floated down I saw a column of smoke coming from the ground.

The action happened to fast that I didn’t get a chance to survey the conditions in the plane as I bailed out a few seconds after the plane was attacked.

If I can be of further help please let me know but I have no more information. Any more, would be pure guess work.

Yours truly,

Walter Mosevich

Sgt. Mosevich’s note, as it appears in the MACR:

______________________________

The FindAGrave biographical profile for Sgt. West is very extensive, and includes an account of the loss of QK * B+ written by Max F. Veitch (long after he war, I guess, and I suppose uploaded in 2018 by Donald Winters?) which corroborates the information in the MACR.

Mr. Veitch wrote: “We became a lead crew and were on our 18th mission when we were shot down over Germany. We were flying B+ a PFF ship (#42-51907). We had an 11-man crew on board. We were on the bomb run when we lost our #3 engine. After dropping our bombs on the target, we lost our #1 engine and had to leave the formation as we were losing altitude rapidly.

“We called for fighter support, but none came. Our pilot ordered us to get rid of all the excess weight that we could. We headed back towards our lines. I was in the bomb bay throwing out all the excess stuff that I could, when I felt a large explosion and heat coming toward me from the rear of the ship. I grabbed my chest chute to dive out as the ship started down. I was able to get only one side hooked, but it carried me down okay.

“As I was floating down, I saw three German Me 109s following the ship down. I did not see it crash. I also saw only three other chutes going down on the other side of a river. I did not know who got out until that night when the German civilians got us together and took us to a town and put us in a small jail cell.

“Our tail gunner’s leg [Schmitz] was shot up from his foot to his knee. Mosevich, our waist gunner, was shot in the arm and I was hit below the eye and in the hand. The ‘G’ Navigator, Lt. Bail, had minor injuries.

“After about a week in that jail cell with only a loaf of bread and some water, two German soldiers came and escorted us to the railroad station in Stuggart. We got on a train and were taken to the town of Goppengen where there were four German hospitals. Sgt. Schmitz was operated on April 1 , [two weeks later!] 1945 and died shortly afterwards. He was buried in a cemetery near the hospital.

“We were liberated on 21 April 1945 by the 44th infantry. Sgt. Mosevich died a few years ago. As a side note, our navigator, Lt. James Haney, was in the 44th base hospital at that time and did not fly with us on this mission. Lt. Dudley Chase was his replacement. It was the first time for Lt. Bail to fly with our crew also.”

The FindAGrave profile also includes the following statement by a Willi Wagner, a civilian lumberjack from Neubaerenthal, which is described as being from “AGRC [American Graves Registration Command] case #4785, Evacuation #1F-1750”.

“On 19 March 1945 while working in the Hagenschiess forest, I observed an American bomber pursued and fired on by three German fighter planes. Thereupon the planes disappeared. Several minutes later, however, the bomber returned flying upside down at an altitude of approximately 40 meters only. As far as I could see a piece of the right wing with one motor had broken off. When the plane was just over the road leading from Wurmberg to Pforzheim-east I saw one crewmember falling out of the plane. On visiting the place where he crashed I discovered one deceased American whose parachute had failed to open. The plane itself continued its flight for approximately 2,000 meters and then crashed into the so-called ‘Hartheimer Rain.’ I heard a strong detonation and saw a dark smoke cloud at the place concerned.

“On the next day I found the charred remains of five or six bodies of the place of crash. The crewmember who had fallen out of the bomber was buried at the spot where he had crashed by Rudolf Sigricht, former postman and two other men from Neubaerenthal three or four days later as I have learned.

“Nothing is known to me with regard to the burial of the five or six bodies found among the plane wreckage.

“In June 1945 the deceased American who fell out of the plane was disinterred, examined and evacuated on a truck most probably to Pforzheim by a French team. I believe no identification was possible.”

Rob Fisk, a navigator who flew thirty missions with Howard Hinshaw’s crew, believes that Dudley Chase was killed by German civilians. Fisk’s son, Bradley Fisk, wrote: “Dudley Chase and my father were good friends at Shipdham. They had adjacent bunks in the same Quonset hut. Mrs. Chase would occasionally send cookies. To keep her son honest she would frost them with a D for Dudley or an R for Robert. Around the time my father rotated home, he received word that Dudley Chase had been shot down. Parachutes were seen, and my father held out hope for his friend. However, after Dad came home, he heard that when that section of Germany was occupied by the Allies, the locals pointed out the location of the graves of several Allied airmen. One of these turned out to be Dudley Chase… Dad had heard that Chase had landed safely near another crewmember but that they had separated for safety. My Mom and Dad were told at Cambridge cemetery [during a 1983 visit] that Chase was captured and killed by civilians. His body was exhumed after the war and Dad was told that he bore the marks of multiple pitchfork wounds.”

Based on this compilation of information, I believe that there was no war crime: A search of NARA’s database reveals no name index card in Records Group 153 (Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General) for Dudley Chase. Similarly, none of the three survivors mentioned encountering Sergeant Chase after bailing out.

______________________________

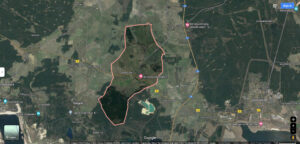

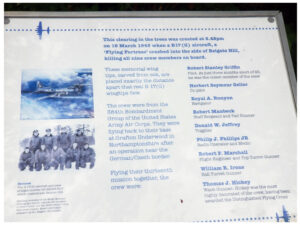

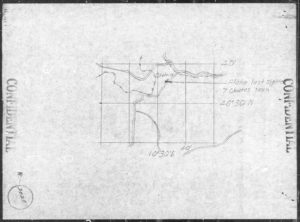

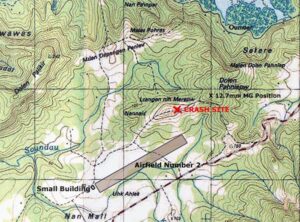

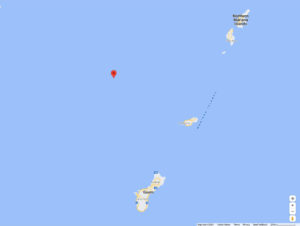

Here’s the map in MACR 13574 showing the last reported position of QK * B+: Somewhere southwest of Stuttgart…

…which corresponds to somewhere between Sindelfingen and Boblingen.

Though the MACR isn’t specific on the point, a clue to the location of QK * B+’s loss lies in lumberjack Wagner’s mention that the bomber crashed into the ‘Hartheimer Rain.’ The closest linguistic match for this phrase is “Hardheimer Hain”, the location of which corresponds to an area between Sindelfingen and Boblingen, as illustrated in this view from MapCarta. (It’s not on Oogle Maps.)

Here’s how the location appears on an Apple Map…

This v e r y large scale map view (note the 750 foot scale in the upper left!) reveals that this location is in a presently forested area…

…while this air photo view of the same locale – at the same scale – suggests (best as I can tell) that this area became the site of a (long since dismantled) Nike missile installation (?) from the first (?!) Cold War.

_____

__________

____________________

__________

_____

Thus for March 19, 1945, Lt. Bail’s 25th and final mission.

Much more happened to him on June 5, 1944, one day before D-Day.

On that June Monday, as a Second Lieutenant, Lt. Bail parachuted from the badly damaged B-24H 41-28690 (Missouri Sue / “QK * B“) piloted by Captain Louis A. Mazure, during a mission against German coastal defenses near Wimereux, France. Eleven of the aircraft’s twelve crew members survived – Captain Mazure having been instantly killed by flak – among them Lt. Col Leon R. Vance, Jr., Deputy Group Commander of the 489th Bomb Group, who received the Medal of Honor (the only such award to go to an 8th Air Force B-24 crewmen) for his actions that day, and one of the fourteen 8th Air Force airmen to have received that award. Lt. Col. Vance has received six “Remembrances” at the National WW II Memorial.

This photo of the Colonel (a few years before he was a Colonel) is from the Congressional Medal of Honor Society. The image probably dates from 1939, the year he graduated from West Point, given that he’s wearing lieutenant’s bars and infantry collar devices.

This undated portrait of the Colonel is from the Air Force Historical Support Division. He’s now in the Air Corps, as evident by his collar devices.

While there’s no Missing Air Crew Report covering this incident – there didn’t need to be; none of the eleven survivors were missing for more than 48 hours, and Capt. Mazure’s fate was immediately known – there’s much information about the event due to its historical significance. Rather than recapitulate and repeat each and every detail through my own write-up, this information is presented below, in the way of: 1) An excerpt from Roger Freeman’s 1970 The Mighty Eighth, 2) A transcript of Lt. Col Vance’s 1945 Medal of Honor citation from Wikipedia, 3) A transcript of a 1944 article from The Gary [Indiana] Post-Tribune found at Captain Mazure’s FindAGrave biographical profile, and, 4) The full (and actual) story of the incident from Will Lundy’s 2004 44th Bomb Group Roll of Honor and Casualties. The latter two sources are particularly revealing.

There appear to be at first subtle, but then – on contemplation – subtle (?) differences, in terms of the specific chain of events and individual actions that occurred aboard Missouri Sue, that emerge when comparing the Colonel’s Award Citation, to the accounts of the mission as reported in the 1944 newspaper article about Captain Mazure, and, the story in 44th Bomb Group Roll of Honor and Casualties, the latter based on reports by Missouri Sue’s bombardier, navigator, radar navigator (Lt. Bail), radio operator, and left waist gunner.

For your consideration, I’ve highlighted these incongruities in dark brown text, like this.

The bomber’s crew comprised:

Command Pilot – Vance, Leon R., Jr., Lt. Col. 0-022050 – Severely wounded (See here and here)

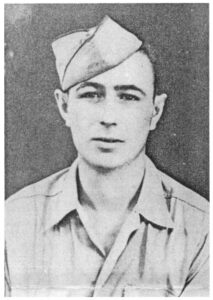

Pilot – Mazure, Louis A., Capt. – Killed in Action

Co-Pilot – Carper, Earl L., 2 Lt. (Is this him…?…(1918-1980)) – Bailed out over English Channel; Rescued

Navigator – Kilgore, John R., 2 Lt. – Injured on landing

Radar Navigator – Bail, Bernard W., 2 Lt.

Bombardier – Segal, Milton, 2 Lt. – Concussion

Bombardier – Glickman, Nathaniel, 2 Lt. (4/18/22-11/15/12)

Flight Engineer – Hoppie, Earl L., T/Sgt. (7/25/22-12/13/90)

Radio Operator – Skufca, Quentin F., T/Sgt. – Severely wounded (5/16-24-1/18/14)

Gunner (Right Waist) – Evans, Davis J., Jr., S/Sgt. – Wounded

Gunner (Left Waist) – Secrist, Harry E., S/Sgt. – Wounded (9/26/15-2/14/01)

Gunner (Tail) – Sallis, Wiley A., S/Sgt. – Wounded

______________________________

Let’s start with The Mighty Eighth (page 144):

On the eve of D-Day when the heavies were pounding coastal defences between the Cherbourg peninsula and the Pas de Calais, the 489th Group was bracketed by flak again. The lead aircraft took a burst near the right side of the cockpit, killing the co-pilot and practically severing the right foot of the air commander, Lt. Col. Leon R. Vance, who was standing on the flight platform between the pilot’s seats. Despite this injury Vance ordered the bomber to be kept on its bomb run for fortifications near Wimereaux. The ailing Liberator, hit in three engines, managed to reach the English coast where Vance ordered the crew to bale out. Told there was an injured man in the rear, who could not jump, Vance remained alone in the wreckage of the cockpit and by some miraculous effort succeeded in the difficult task of ditching a B-24. An explosion as the aircraft settled beneath the waves, blew him clear severing his mutilated foot. Clinging to a piece of wreckage he managed to inflate his life jacket and began to search for the wounded man he believed aboard. Failing to find anyone he began swimming and was picked up 50 minutes later by a rescue craft. Vance survived the extraordinary episode. By the irony of fate, his air evacuation C-54 to the US in late July disappeared without trace on the Iceland-Newfoundland leg. Leon Vance’s unquestionable courage, skill and self-sacrifice brought him the only Medal of Honor to go to a Liberator crewmen engaged on operations from the UK.

______________________________

Next is Lt. Col. Vance’s Medal of Honor citation, dated January 4, 1945:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty on 5 June 1944, when he led a Heavy Bombardment Group, in an attack against defended enemy coastal positions in the vicinity of Wimereaux, France. Approaching the target, his aircraft was hit repeatedly by antiaircraft fire which seriously crippled the ship, killed the pilot, and wounded several members of the crew, including Lt. Col. Vance, whose right foot was practically severed. In spite of his injury, and with 3 engines lost to the flak, he led his formation over the target, bombing it successfully. After applying a tourniquet to his leg with the aid of the radar operator, Lt. Col. Vance, realizing that the ship was approaching a stall altitude with the 1 remaining engine failing, struggled to a semi-upright position beside the copilot and took over control of the ship. Cutting the power and feathering the last engine he put the aircraft in glide sufficiently steep to maintain his airspeed. Gradually losing altitude, he at last reached the English coast, whereupon he ordered all members of the crew to bail out as he knew they would all safely make land. But he received a message over the interphone system which led him to believe 1 of the crew members was unable to jump due to injuries; so he made the decision to ditch the ship in the channel, thereby giving this man a chance for life. To add further to the danger of ditching the ship in his crippled condition, there was a 500-pound bomb hung up in the bomb bay. Unable to climb into the seat vacated by the copilot, since his foot, hanging on to his leg by a few tendons, had become lodged behind the copilot’s seat, he nevertheless made a successful ditching while lying on the floor using only aileron and elevators for control and the side window of the cockpit for visual reference. On coming to rest in the water the aircraft commenced to sink rapidly with Lt. Col. Vance pinned in the cockpit by the upper turret which had crashed in during the landing. As it was settling beneath the waves an explosion occurred which threw Lt. Col. Vance clear of the wreckage. After clinging to a piece of floating wreckage until he could muster enough strength to inflate his life vest he began searching for the crewmember whom he believed to be aboard. Failing to find anyone he began swimming and was found approximately 50 minutes later by an Air-Sea Rescue craft. By his extraordinary flying skill and gallant leadership, despite his grave injury, Lt. Col. Vance led his formation to a successful bombing of the assigned target and returned the crew to a point where they could bail out with safety. His gallant and valorous decision to ditch the aircraft in order to give the crewmember he believed to be aboard a chance for life exemplifies the highest traditions of the U.S. Armed Forces.

______________________________

Here’s the story as it was reported in The Gary Post-Tribune sixteen days later, in a tribute to Captain Mazure:

Capt. Louis Mazure Dies at Controls of B-24 in Epic Story of Heroism

Gary Flier Hit by Flak Over French Target, Co-Pilot “Pushes” Crippled Plane to Coast

Friday, July 21, 1944

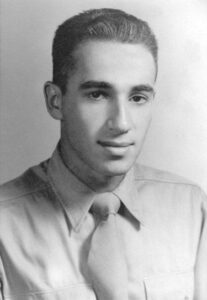

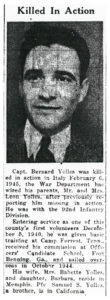

This portrait of Captain Mazure (as a lieutenant) is from his FindAGrave biographical profile, via Elizabeth Rhodes.

Capt. Louis A. Mazure, Froebel high school and Gary college graduate and 28-year-old son of Mrs. Helen Mazure, 110 East 43rd, had been identified today as the pilot of a Liberator bomber who alone among the ship’s complement lost has life June 2 when the plane was riddled with flak and shorn of all its power as it prepared to drop its bombs over a pre-invasion target on the French coast.

The crippled ship was glided all the way back to the English coast by Mazure’s 26-year-old co-pilot, Lieut. Earl L. Carper of 7108 Ingleside, Chicago, under direction of a colonel command pilot whose left foot had been blown off by a shell burst over the target.

Out of deference to the Gary captain’s kin, who had not yet been notified of his death, his name was omitted from an official account of the almost incredible incident released at an 8th air force Liberator station in England a few days after the tragedy.

Family Given Clew

Publication of a fragment of the graphic story in a Chicago newspaper, which named Carper as the co-pilot, gave the Mazure family the clew which led to identification of the Gary captain as the skipper of the ill-fated craft who died at the controls just as his bombardier, Lieut. Milton Segal of Brooklyn, took over the ship for the final run over the target.

In one of his letters home, written in late May, Mazure, who normally piloted Flying Fortress bombers, disclosed he had recently been flying “different types” of four-engine craft, and listed Carper and Segal among the members of his newest crew.

The captain’s brother, Anthony, who lives at 28 Ruth street, Hammond, interviewed the co-pilot’s mother, Mrs. Howard E. Carper, in Chicago, and thereafter said he was convinced that Captain Louis, who had written May 23 that he expected to be back in Gary “soon,” was the pilot of the “Lib” that made history by its motorless escape flight across the English channel.

Held Private License

A former employee of the Gary works electrical maintenance department, Mazure was one of the first CPT graduates turned out by Gary college and the Calumet air service, and had held a private pilot’s license for about two years up to the time of his induction as any army aviation cadet in August 1941.

He won his wings March 18th, 1942, at Mather Field, Calif., and before embarking for overseas served as a gunnery instructor on multi-engine bombers at Las Vegas, NM. He was promoted to first lieutenant April 17th last year, and to a captaincy early this spring.

He received the air medal and presidential citation for his participation in the first U.S. bomber raid upon the Ploesti oil fields in Romania, and is believed to have logged more than 25 combat missions up to the time he last wrote his mother, May 23.

Ranked as First Chief

He was a squadron operations officer during the early part of his service in England, and was ranked as a flight commander at the time of his death.

A copy of the official version of Captain Mazure’s last flight and of the epic trans-channel escape of the Liberator and its crew after the pilot died from a flak wound in the temple, was obtained by the pilot’s brother from Mrs. Carper.

It disclosed that the crippled bomber finally was “ditched” in the channel just off the English coast channel by the wounded command pilot after everyone had bailed out over English soil at his orders.

Five of the crew were wounded, but Mazure was the only fatality. The other six men were shaken and bruised, but otherwise uninjured.

“As the Liberator started on its bomb run over coastal France,” said the unidentified author of the official account, “it was subjected to a continuous hail of heavy flak and suffered repeated hits.”

“‘I don’t know at what point each engine got it,’ related Lieutenant Carper, ‘because bursts were getting us right along.’

“Good Boy,” His Last Words

“The bombardier, Lieutenant Segal, was not wearing his flak helmet when the first burst hit the nose of the ship. He left his bombsight for a second to get it, then returned to his position. As he bent over his sight a second burst caught the nose, knocking Segal’s helmet from his head. This time he did not attempt to retrieve it. Over the interphone he informed the pilot (Mazure) that he was ready to take control for the final run. “I’ve got the ship,” he said. “Good boy” replied the pilot. Those were his last words, for a piece of flak struck him in the temple and killed him instantly.

“With the pilot dead, the Liberator continued over the target and the bombs were released.

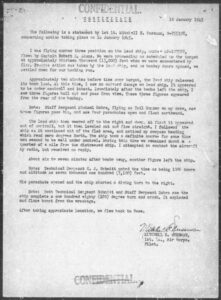

“Meanwhile the entire ship was in an uproar. At approximately the same time the pilot was killed, the command pilot (still unidentified officially) received a hit which blew off his left foot above the ankle. Lieut B.W. Bail of Philadelphia ripped off his heavy gloves when he saw that the foot had been blown off. From the first aid kit he removed bandages, a tourniquet and sulpha.

“Quickly applying the tourniquet to the colonel’s knee, he sprinkled sulpha over the wound and bandaged the bleeding stump. Medical men afterwards credited this action with saving the wounded officer’s life.

4 Others Wounded

“Amid all this confusion, four other crew members had been wounded, the nose of the plane shattered and gasoline was flowing about in streams causing an extreme fire hazard.

“Carper had little chance to see what else was going on in the ship. He took over as the pilot slumped over the controls and when he heard ‘Bombs away!” swung the nose of the ship toward England. At this point the command pilot, who had managed to pull himself to his feet, braced himself between the pilots’ seats and leaned over and pulled the throttles, then pushed them back.

“‘No power,” he told Carper. “Cut all the switches.”

“This Carper did, and they began the long glide back to the British coast.

Dropped 5,000 Feet

“ ‘We dropped 5,000 feet in what seemed a second,’ related Carper. ‘A B-24 isn’t much of a glider, but we got back over England. The colonel (command pilot) was the bravest guy I ever saw. When we got over land, he told all the crew to bail out and then wanted me to try to ditch it.’

“Carper, who had watched the ship lose more and more altitude, wanted the command pilot to bail out but he refused and, instead, ordered Carper to ‘hit the silk’.

“The co-pilot jumped over land, but as they had turned the nose again after the rest of the crew had bailed out, he landed in the channel. The command pilot sat on the edge of the seat and pulled back on the controls, which was all he could do to ‘ditch’ the big ship. The Liberator landed on the water and he was thrown clear.

“In an example of physical stamina that defies explanation, the injured man swam three miles, spending 45 minutes in the icy water, before he was picked up by a rescue boat.

“Meanwhile the other crew members who had bailed out were having plenty of trouble. Carper became entangled in the shroud lines of his chute and had to struggle desperately to keep afloat. It was due only to the alertness of a Spitfire pilot who saw the Liberator as it turned back to sea and kept circling it until it crashed that a rescue ship sped out and picked him up in 25 minutes.

“Segal, the bombardier, had jumped over land, but when he pulled the ripcord nothing happened. Frantically he ripped open the canvas and pulled the silk out by hand, the chute finally blossoming above him.

“Another crew member landed in a minefield and the fact that he broke a leg in the fall and could not move probably saved his life, since a rescue party discovered that he lay within a yard of an antipersonnel mine that would have exploded had he touched it.

“The remainder of the crew made their jumps without incident, although Lieut. Nathaniel Glickman, New York City, wounded in the forehead and arm by flak fragments, complained bitterly because the wind carried him half a mile away from a WAAF camp that he had expected to land in.”

Captain Mazure’s body was not recovered, the crippled Liberator carrying it to the bottom of the channel as it sank after the crash landing.

Other injured crew members were Staff Sergts. Harry E. Secrist, Newark, O., David E. Evans, Jr., Massilon, O., and Wiley A. Sallis, Smithville, Miss.

______________________________

Finally, this complete account of Missouri Sue’s last mission is from Will Lundy’s 44th Bomb Group Roll of Honor and Casualties. This is comprised of statements – made in the 1980s or 1990s? – by Nathaniel Glickman (bombardier), John R. Kilgore (navigator), Bernard W. Bail (radar navigator), Quentin F. Skufca (radio operator), and Harry E. Secrist (left waist gunner).

Captain Mazure was piloting this aircraft, flying lead for the 489th BG and the 2nd Division. The primary target was reported to be coastal installations at Boulogne-sur-Mer but actually was a V1 Site, Wimereaux, North Boulogne.

Briefing was scheduled for 0400, even though Colonel Vance evidently had been held up and was late. So the briefing continued with the information that the bombing would be from 22,500 feet and the bomb load would be 10,500 pound GPs. Stepping away from the map, the officer addressed the bombardiers and stressed the point that should they for any reason fail to drop the bombs on the first run, they were to jettison the load over the English Channel and return to their bases. No second run was to be made over the target.

The meteorologist added that there would be broken clouds over the coast and should be clear sailing in and out. Intelligence reported that we could anticipate flak at the French coast and that no enemy fighters were expected so there would be no fighter escort.

Col. Vance arrived at 0830, apologized for his delay, and asked Capt. Mazure to review the information we had received at the briefing. When he had finished with the flight plan, Lt. Glickman informed him of the instructions regarding the bomb run and the specific order not to make a second run over the target.

Takeoff was at 0900; the mission was rather routine as Lt. Bail, radar-navigator, guided the formation via his radar “Mickey” toward the Pas de Calais sector of French Coast. As they approached the IP, control of the aircraft was turned over to Lt. Segal, bombardier, for the bomb run. Lt. Glickman called out the target and then watched for signs of flak and enemy fighters. There appeared to be flak off to the starboard side but it was of little consequence.

As the target was approached, Lt. Segal ordered the bomb bay doors to be opened, steadied down and then called out “Bombs Away.” Nothing happened! Every bomb was still hanging in the bays. The other aircraft in the formation awaiting our drop, failed to release theirs, too. Either there had been a malfunction in the bombsight, or the arming release switch on the bombardier’s panel had not been activated. So nothing happened due, apparently, to some faulty equipment, and no bombs were dropped by any of the aircraft in our formation.

Lt. Glickman added that “We turned off the target and at that time I notified our pilot, Mazure, that we were to head back over the Channel and jettison our bombs according to the briefing instructions. But Col. Vance countermanded my orders and directed that we make a second run, informing us that he was in command of this flight.”

Departing the immediate area, they flew south, circled and flew parallel to the coastline, at the same altitude and airspeed, but as the enemy gunners had zeroed in on them, the first flak burst exploded off their port wing. The pilot, Mazure, was killed when shrapnel sliced in under his helmet, and struck him in the head. Lt. Carper, the co-pilot, immediately took over the controls. When the next blast hit, it tore through the flight deck, hit Col. Vance (who was standing between the dead pilot and Lt. Carper) and nearly severed his right foot so that it was hanging by a shred.

Lt. Bail gave this report, “Our bomb bay doors were still open and I could see that a couple of bombs were still hung up. About this same time, the co-pilot Carper, cut off all four engines and switches, fearing that the plane would catch fire and blow up. He quickly turned our ship for England in a shallow glide. I then began calling the various members of the crew on interphone and was relieved to learn that no others were badly injured.

“As soon as possible, I managed to get Colonel Vance down to my seat, took off my belt and wound it around his thigh as a makeshift tourniquet to reduce the spurting blood.”

Lt. Glickman continued, “At this same instant my nose turret took a series of bursts that shattered the Plexiglas and cut open my forehead, as well as hitting the base of my spine. Our plane continued to be hit as we stayed on the bomb run. My primary concern was the possibility of our bomb bays being hit before the bombs were released.

“The starboard outer engine (#1) had been hit and the propeller was now snapped with the three blades drooping downwards. The top turret had most of the Plexiglass blown off, part of the right rudder and rudder elevator also had been hit. Concerned about the previous inability to release our bombs and now approaching the prior drop point again, I called out that I would drop the bombs using my turret release switch that would bypass the bombardier’s panel. The other bombers following us in our formation unloaded at the same time that I did.

“After I released our bombs, my turret took another hit which not only cut my left hand but blasted off another large portion of the turret Plexiglass. Looking at my pilotage map I advised Carper of our position and gave him the return heading to England. The celestial navigator had his equipment, his desk table and charts destroyed and with Bail aiding Vance, I had maps with which to aid the pilot.

“We continued to get hit; the radio room took flak which severely wounded Sgt. Skufca.” On the flight deck and behind the two pilots and Col. Vance were the two stations for the PFF navigators: Lts. Bail and Kilgore. John Kilgore added these comments, “As we left the south coast of England, the Germans began to jam my ‘G’ set, as usual, so I looked over at Bail to see if his “Mickey” was operating, but he shrugged his shoulders, ‘No.’ This had been the same conditions as from the other two previous missions. We turned at our I.P. (Initial Point) and headed north, and as we approached the target, Glickman said he could see our target through the broken clouds. I assumed that Segal was on the target with his sight.

“At ‘Bombs Away,’ nothing happened! Vance did order a second run on the target. Why we didn’t take some sort of evasive action or change in altitude is still a mystery to me. The second run was uneventful until the bombs were released. Even then, I don’t recall hearing the crump of ack-ack. But I do recall, and very vividly, the left side of the plane pressing inwardly against my right arm. The flak jackets jumped off the flight deck floor, my instrument panel going dead, the sight glasses of the fuel transfer system disintegrating, and raw high-octane gasoline streaming onto the flight deck. Hoppie, our engineer, literally ‘slithered’ out of the top turret, grabbing what I thought was a flight jacket and trying to stem the flow of gasoline with one hand, turning off the fuel transfer valves with the other.

“About this time Glickman came over the intercom announcing that he had been hit in the head and blood was streaming down over his face so that he could not see. One of the waist gunners, Secrist, came over the intercom that Skufca had been hit badly in the legs. As he was calling no one in particular, I answered by telling him of our situation on the flight deck, and asked him and Evans to see about Sallis, our tail gunner, and to assist Skufca out of the plane when the time came.”

“Apparently we had experienced two to three hits or misses – there was no direct hit, for if there were, none of us would be here. The plane seemed to be ‘sailing’ along on an even keel. At no time were there any sudden diving, stalling or yawing motions. I turned to Bail and told him to turn on the I.F.F. (Identification, Friend or Foe) switch was directly above his head, and had a red safety cover over it. As we had left the formation, and we were approaching the English Coast, we must be identified.

“I got up from my seat and looked into the cockpit area, found Mazure slumped in his harness and his instrument panel was covered in blood. Carper was in the co-pilot position, doing what all good co-pilots do, trying to keep the plane flying. I then jumped down into the ‘well’ of the flight deck along side of Hoppie – not that I could assist him in any way, but to be first in line. Hoppie didn’t need any help as he was a true professional and knew his job well.

“As we were standing there looking down at the water, the doors began to close. Hoppie grabbed the manual crank to open them again, and I reconnected my intercom, yelled for someone not to close them again. Apparently the message got through as the doors were never closed again.” Glickman added, “As we headed towards England, the plane took one last blast that cut the gas lines and forced Carper to cut all the switches to prevent any fire and stopped all three remaining engines as well as the power to my nose turret. With that action and starting the no-power glide towards England, I heard the bailout bell and someone calling us to bail out.”

S/Sgt. Harry Secrist, left waist gunner, added his recollections of what took place in the rear of the aircraft: “Skuf was hit while still in his radio room and fell out of it into the waist area ahead of us. He was badly injured and could not stand. Gasoline was spraying all over us in the waist and Skuf was lying on the waist floor in all of that gasoline. So I grabbed a spare parachute and put it under his head. As I stood up, another large burst of flak came through the side of the waist and passed between Skuf and me. It made a hole in the right side about ten inches wide, then made several holes on the left side where it went out.

“All of the tail assembly was intact, but the left rudder and vertical stabilizer had a lot of holes in them. Dave opened the hatch door in the floor and was sweeping some of the gasoline out with his foot.

“When we got near the coast of England, I threw the left waist gun out of the window and turned to get Wiley and Dave to help me lift Skuf to the waist window where he could bail out. But when I turned back from the window, Wiley had Skuf and was going into the bomb bay where they eventually bailed out. Dave went out the right window and I went out the left. I fell about a half mile, it seemed, to get rid of the gasoline on me. We were all soaked with it and wondered about the static electricity when the chutes opened. I think I was the only one of us who bailed out of the rear area to land in a minefield.

“After I opened my chute, I was about a thousand feet above a large cloud and when I came out of the cloud, there was a barrage balloon under it. I missed it by about 100 feet. Then, when I got below the balloon, I was drifting toward the cable, but missed it, too, by about 50 feet. As I got closer to the ground, I saw men running along a dirt road toward me, then came down about 60 to 70 feet from the edge of the cliff next to the Channel, and just a few feet from a fence that ran parallel to the cliff. My parachute fell across this fence and some barbed wire between the fence and the edge of this cliff. This barbed wire was about eight feet high.

After releasing my parachute harness and standing up, I started to walk down to the road. I had taken only a few steps when I understood what the British Sergeant was yelling to me. He was shouting for me to stand still as there were land mines everywhere. Help was on the way with maps to guide me through this field!

After spending a most interesting overnight at this remote cannon emplacement unit, Harry Secrist was driven to the huge British airbase at Manston where he was united with Sgts. Evans and Sallis. None of them were injured in their parachuting.

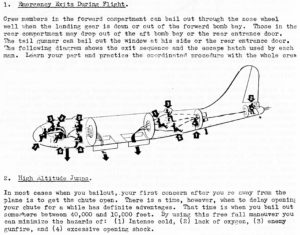

Lt. Bail continued his recollections. “As our plane neared the English coast, still gliding without power and rapidly descending, I directed the crew to start bailing out. When only Colonel Vance and I remained, I told Col. Vance that we must now jump as there was no way to land that damaged plane, especially with those bombs hung up in the bay, armed and ready to explode on impact. Not being a doctor then, I was not fully aware that the Colonel was in shock. When the Colonel shook his head and said he wouldn’t jump, I knew that there was no way I could drag him to the bomb bay, and assist him out. I knew, too, that the plane was losing altitude fast, and we didn’t have much time. I checked his tourniquet, shook his hand and made my plunge through the open bay.

“We bailed out between Ramsgate and Dover in Kent, most of the earlier ones out landing near the water, but on land. I, being the last to parachute, came down a bit further inland, but not too far away from them. Lt. Kilgore broke one leg in two places when he hit the ground.

______________________________

This map shows the English Channel / North Sea between Calais and Dover. Ramsgate is northeast of Dover, on the British coast.

______________________________

Lt. Glickman continued, “I was the last man to bail out inasmuch as I was trapped in the nose turret after it had been shattered by flak and the power to turn it in position for me to fall backward had been cut off. I was forced to break my way out although I was wounded and hit in several places. The Air Force Telex indicated that I was blinded by blood and was led to the bomb bay simply was not true.

“When the bailout bell rang, you can imagine the mass exodus! But now I crawled to the nose wheel area, snapped on my chest chute, and because my legs were useless, crawled through the tunnel under the flight deck to the bomb bay catwalk. The only men I saw on board at that time on the flight deck were Col. Vance and the dead pilot, Captain Mazure. In fact, I had to push the bombardier, Milton Segal off the catwalk before I rolled off the catwalk myself.

“I withheld opening of my chute for a time until I was sure no other aircraft was in the vicinity, and also I was very close to the Channel, with the breeze bringing me back over land. I was lucky in that I landed on the lawn of the Royal Marine Hospital at Deal, on the cliffs of Dover.”

Lt. Bail continued, “When I visited Col. Vance in the hospital, he told me that he had worked himself forward, crawled into the co-pilot’s seat, and turned the aircraft away from that populated area and back out to sea. Captain Mazure’s body was still in the pilot’s seat so he was forced to get into the co-pilot’s position. When the ship hit water, the bombs exploded and destroyed the aircraft, somehow not killing the Colonel. Finding himself still alive and conscious, the Colonel began swimming toward the shore, injured leg and all, until rescued by a ship in that vicinity. “Later at the hospital, the Colonel told me that he was eager to get back into combat, and would as soon as he recovered. Most unfortunately, the Colonel was killed when he was being returned to the States and his airplane was lost at sea. After the war, I was invited to attend the ceremonies when the Colonel’s widow was presented with his Medal of Honor.”

On the 19th of March, 1945, Lt. Bail, with another crew, was shot down over Germany and became a POW.

Lt. Nathaniel Glickman added, “A number of years ago I attended a reunion of our Second Division at the Air Force Academy. There, I met a co-pilot of one of the Wing crews on our flight who related the following story, which added a new bit of drama to the end of this flight. He had witnessed the damage to our plane and had counted the number of our crew that had bailed out. Our plane was still airborne and headed inland, but as you know, was losing altitude. Someone had contacted the authorities, which, in turn, were concerned that the plane might crash into a built up area and allegedly, gave orders to them to shoot it down. Just as they turned to follow those instructions, our plane began its very slow turn to the left back towards the Channel where both Segal and I bailed out. The order, of course, was canceled, when it was noted that the plane was still under control and attempting to turn. You can imagine my feelings when I heard this story!”

“I, too, visited Col. Vance at his hospital as soon as I was able to get around with a cane. He informed me that he had submitted my name for the Silver Star which I was informed a month later had been approved. However, the medal was not given to me until this past May (1986) at a formal dress parade at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

“I returned to combat within a month. I had a sergeant carry the bombsight to the ship and I limped along with a cane during my first few flights. Later, I was listed as Pilotage Navigator/Bombardier and 66th Squadron’s Lead Bombardier, and completed 19 more missions.”

Only Lts. Bail and Glickman and the two waist gunners flew additional operational missions! T/Sgt. Skufca was sent to Station 93 Hospital near Oxford for treatment of his shattered ankle and leg wounds. Skin grafts were necessary, so he remained there for several months. Eventually he was moved to Station #318 near Norwich while his severed Achilles tendon healed. On December 18, 1944, he was evacuated to the U.S. for further grafts and treatment. He never walked normally again.

This mission was the subject of a lengthy article called “Sometimes I Can’t Believe It” in True magazine. The author was Carl B. Wall. Wall describes MISSOURI SUE as “a plain, businesslike aircraft…no fancy lettering on its sides…no pictures of pretty girls.” Wall also tells a story about Vance’s recovery after losing his foot: “During one of the depressed stages, he was crutching along a London street when an eight-year-old boy yelled at him: ‘You’ll never miss it, Yank!’ The kid’s mother came up to me and apologized, says Vance. Then she explained that he had lost his own foot in the blitz and was getting along fine with an artificial one. That was the biggest boost I got. Felt a devil of a lot better after that.”

______________________________

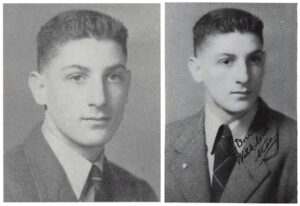

Dr. Bail’s curriculum vitae includes two images of his fellow crew members. While unfortunately the pictures are absent of captions, it’s still possible to identify three men in the photos. Given that none of his fellow crewmen – with the exception of Lieutenant Glickman and Sergeants Evans and Secrist – continued to fly combat missions after the flight of June 5, 1944, and that Lt. Bail was new to the Podojil crew on March 19, 1945, it can be assumed that this was Lt. Bail’s original crew, and therefore the men who were aboard Missouri Sue on June 5, 1944.

In the picture below, Lt. Bail is third from left, Lt. Segal second from left, and I think (by comparing photos) that Lt. Mazure is at far left. Therefore, the officer on the right is probably Lt. Carper.

This image shows nine members of Lt. Bail’s crew; was the photo taken by the tenth men – whoever he was? Lt. Bail is second from right, and Lt. Segal probably third from right, smoking a cigarette.

______________________________

Of the two other Jewish crewmen aboard Missouri Sue, the name of one appeared in American Jews in World War II, and the other, not.

2 Lt. Nathaniel Glickman (0-751902), son of Mrs. Getrude Glickman, was born on April 18, 1922, and resided at 225 East Moshulu Parkway in Brooklyn. The recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with three Oak Leaf Clusters, and Purple Heart, his name appears on page 323 of the above volume. He passed away on November 15, 2012.

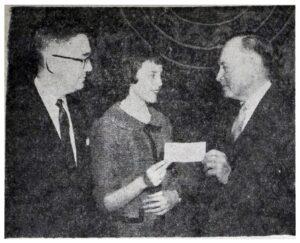

Like very many other American Jewish servicemen who were casualties, or, received military awards, the name of 2 Lt. Milton Segal (0-685854) was not recorded in American Jews in World War II. However, he was mentioned in passing in the Brooklyn Eagle on August 4, 1943, and, July 14 and November 15 of 1944. Born in Manhattan on October 7, 1915, he was the son of Solomon and Mollie Segal, and the brother of Fritzi, Joseph, Renee, and Rhonda, the family residing at 8729 14th Avenue in Brooklyn.

To my surprise, I discovered (via FultonHistory) that by early 1945 he’d become a convalescent patient at the Army Air Force Hospital in Florence, Kentucky (southwest of Cincinnati). This is revealed in articles published in The Boone County Recorder and Walton Advertiser of March, 1945, which describe an appearance and speech by Lt. Segal and Lt. Leonard A. Charpentier at a Red Cross rally in Florence on February 28, 1945.

This suggests that although he was not visibly – directly – injured by flak during the downing of Missouri Sue, the concussion from the flak burst that blew the helmet from his head resulted in a long-term injury, the effects of which weren’t immediately apparent after the mission of June 5. As recorded by Lt. Glickman in his 1986 communication, like most of the crew of June 5, Segal never flew another combat mission.

Here are the articles from the Recorder:

LARGE CROWRDS ATTEND RALLY

OF RED CROSS HELP AT FLORENCE SCHOOL WEDNESDAY NIGHT, FEBRUARY 28 – FLYERS HEARD ON PROGRAM.

March 1, 1945

Office of Chairman, Boone County, ARC, Feb. 28 – A large crowd is expected to attend the Red Cross rally to be held Wednesday night, February 28, at 7:30 in the Florence school house. There is no admissions charge, and an interesting program has been planned.

The Boone County school band will furnish music, and a War movie will be shown.

Lt. Milton Segal and Lt. Leonard A. Charpentier, convalescents at the AAF Hospital, Ft. Thomas, will talk about their personal experiences with the Red Cross. Lt. Segal was a navigator on a B-24 Liberator Bomber, and served with the Eighth Air Force in England. Lt. Christopher was a P-47 Thunderbolt pilot and served with the Twelfth Air Force in Italy.

____________________

AAF Patients Heard at Meet

March 8, 1945

OF RED CROSS HELD AT FLORENCE WEDNESDAY NIGHT – QUOTA OF $6,800.00 IS SET FOR BOONE COUNTRY

“The Red Cross was in touch with me constantly,” said Lt. Leonard A. Charpentier, when he spoke at the Red Cross Rally Wednesday night, February 28 in the Florence school house.

Lt. Charpentier was a pilot of a P-47 Thunderbolt, stationed in Italy and was shot down in German territory. The first person he saw when he regained consciousness was a Red Cross worker ready to serve him in any way. He said, “The Red Cross hasn’t missed a job – they are everywhere helping the service men in many ways. Naturally, such service must have organization and organization needs funds. I hope your Drive is a complete success. It has been a pleasure to speak for the Red Cross, which has done so much for me.”

Lt. Milton Segal, Navigator on a B-24 Bomber, stationed in England, told how the Red Cross stood by him, when he was shot down over the English Channel. He mentioned the coffee and food the workers always had ready for the men, no matter at what hour they started on a mission. He emphasized the morale value of the Red Cross to Service men. He said, “It really makes you feel the folks at home are backing you up.”

He told about the rest camps and clubs maintained by the Red Cross, and said the only place a soldier could really sleep in London was at the Red Cross club. He told about the good American food and company of American people, and emphasized how important those things are to a soldier overseas.

He stated that he was glad to be able to speak for the Red Cross. It is a wonderful organization – it can go where no other group can go, and it forms the link with home so essential to a Service Man’s peace of mind. Both officers had been entertained at the home of Mr. and Mrs. J.B. Heiser.

Lt. Charpentier was 1 Lt. Leonard A. Charpentier, a Thunderbolt pilot in the 86th Fighter Squadron of the 79th Fighter Group, who was seriously wounded, and then captured, when he was shot down by flak on August 29, 1944, near Valence, France in aircraft 42-26376. The incident is covered in MACR 8384. Subsequent to WW II he had a long career as a physician.

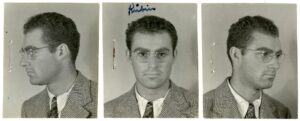

Via the Army Air Forces Collection, here’s Lt. Segal as he appeared in Bombs Away, the graduation book for Bombardier Class 43-10 at Childress, Texas. This portrait also appeared (albeit as a miniscule half-tone image) in the Brooklyn Eagle on August 4, 1943.

A survey of documents and books pertaining to the Allied air forces of WW II reveals several instances where the crews of multi-place – typically, bomber – aircraft included three Jewish aviators (there’s one with four), and many, many more instances – I won’t even bother to tabulate the total number – with two.

Of these, the case of Missouri Sue is only one example.

About Lt. Segal’s postwar life I have no knowledge.

______________________________

Missing Air Crew Report 15544 (a post-war “filler” MACR), which covers the July 26, 1944, loss of C-54 42-107470, on which Lt. Col. Vance was a passenger, is a very bare-bones document, by nature due to the absence of information of what befell the plane, its crew, and passengers. The report lists the crew and passengers by surname, the aircraft have been commanded by Robert W. Funkhouser with the other civilians probably comprising his crew. Catherine Price was the aircraft’s flight nurse. Though the document lists the point of departure as Newfoundland and the destination as Meeks Field, this is an obvious error. As described at Aviation Safety, “The Douglas Skymaster departed the U.K., flying American service personnel back home. Intermediate stops were planned at Keflavík, Iceland and Stephenville, Canada. Last radio contact with the flight was three hours after takeoff from Keflavík, when over the North Atlantic Ocean off Greenland. The aircraft did not arrive at Stephenville and was declared missing. No trace of the plane was ever found.”

Though nothing about the loss of the C-54 will ever be known among men, I do find it of significance that there’s no record of a distress call from the aircraft (assuming one was broadcast) having been received by airfields or monitoring stations in Iceland, Greenland, Canada, or the United States. This would suggest a sudden and catastrophic event that permitted neither opportunity nor time to relay a “Mayday” call. A thorough discussion of the possible reasons for the plane’s loss can be found in the IDPF for passenger PFC Robert C. Bowman, the document suggesting that the loss of this aircraft was under investigation as recently as 2008.

______________________________

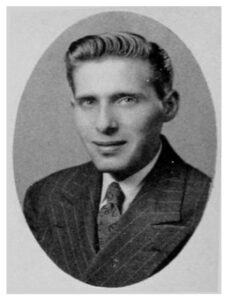

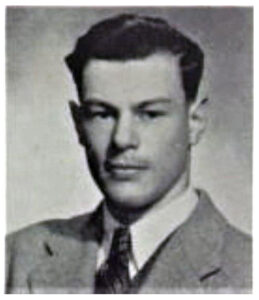

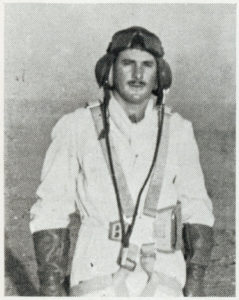

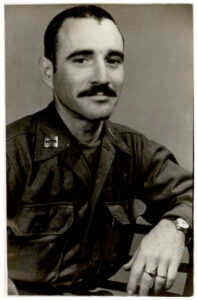

Via Ancestry.com, here’s Bernard Bail’s 1942 graduation portrait from West Chester State Teacher’s College, in Westchester, Pennsylvania, now known as Westchester University…

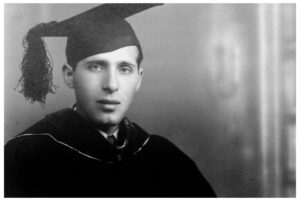

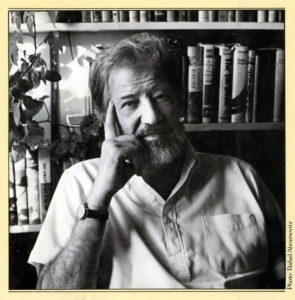

…while this image, via his curriculum vitae, is his 1952 graduation portrait from Temple University’s School of Medicine.

One last photo: Dr. Bail later in life, also from his website.

Three Books

Dublin, Louis I., and Kohs, Samuel C., American Jews in World War II – The Story of 550,000 Fighters for Freedom, The Dial Press, New York, N.Y., 1947

Freeman, Roger, The Mighty Eighth – Units, Men and Machines (A History of the US 8th Army Air Force), Doubleday and Company, Inc., Garden City, N.Y., 1970

Lundy, Will, 44th Bomb Group Roll of Honor and Casualties, 1987, 2004 (via Green Harbor Publications)