“Great fatherland, I intended to die and rest for you!”

But a whirlwind stirred the dead;

they stood at the table one after the other,

captains and medical officers

first and lieutenants and doctors,

sergeants and watch-masters,

non-commissioned officers, privates,

common soldiers.

And the scribe put a dry quill in each hand;

it flowed like a scratched finger;

each one wrote his Hebrew name in small red letters that shone like square seals.

✡ ✡

But a bright cross shone over the forehead of some who were baptized;

the writer asked everyone:

Jew?

And he nodded, he said, “You know”; he said,

“Mosaic denomination”;

“Israelite” he said,

“German of Jewish faith” –

“Jew, yes” some said and stretched,

and the crosses faded from everyone.

✡ ✡

“Oh Akiba,” I cried, “when will the Messiah come?”

His gaze examined my soul.

“At the gates of Rome a hunchbacked beggar,

the Messiah, sits and waits,” said he;

it frightens me like a threat.

“What is he waiting for, Master?” I cried out in fear.

“For you” said the old man and turned.

And I awoke to a sudden, glaring, heart-breaking shock.

✡ ✡ ✡

The lives of men, as much as peoples and nations, are affected by the winds of history in different ways. Some men, entirely unaffected by the even most threatening physical and spiritual challenges, “after the fact” remain much the same as before. Other men, to a greater or lesser degree, may “pause” for a time … weeks, months, years … and eventually, though the trajectory of their lives may be temporarily altered, return to the path previously charted for them by decision and happenstance. Other men are different. An event that for most may have been seen as trivial, or at worst an unintended and soon forgotten diversion, may be perceived in the fullness of its meaning, message, and implications, and symbolically become part of one’s identity, outlook upon life, and vision of the future.

Such seems to have been true of the German writer Arnold Zweig as a soldier in the Deutsches Heer – the Imperial German Army – in the First World War, the course of whose life was strongly influenced by the German Army’s Judenzählung – Census of the Jews – of late 1916.

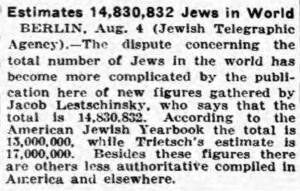

There are many, many sources of information about the Judenzählung, encompassing books and academic papers, focusing on the event in terms of the specific history of Jews in the German military, to the larger scope of German Jewish history, and in an even wider perspective (like that of David Vital), the post-Emancipation history of European Jews as a whole. However, for the sake of brevity, I’ll simply quote the Wikipedia entry for the the Judenzählung. (Yeah, I know it’s Wikipedia, but the information is definitely useful, while the 12 references and 8 extra readings do provide paths for further understanding of the event.)

So…

[The] Judenzählung … was a measure instituted by the German Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL) in October 1916, during the upheaval of World War I. Designed to confirm accusations of the lack of patriotism among German Jews, the census disproved the charges, but its results were not made public. However, its figures were published in an antisemitic brochure. Jewish authorities, who themselves had compiled statistics that considerably exceeded the figures in the brochure, were denied access to government archives, and informed by the Republican Minister of Defense that the brochure’s contents were correct. In the atmosphere of growing antisemitism, many German Jews saw “the Great War” as an opportunity to prove their commitment to the German homeland.

Background

The census was seen as a way to prove that Jews were betraying the Fatherland by shirking military service. According to Amos Elon, “In October 1916, when almost three thousand Jews had already died on the battlefield and more than seven thousand had been decorated, War Minister Wild von Hohenborn saw fit to sanction the growing prejudices. He ordered a “Jew census” in the army to determine the actual number of Jews on the front lines as opposed to those serving in the rear. Ignoring protests in the Reichstag and the press, he proceeded with his head count. The results were not made public, ostensibly to “spare Jewish feelings.” The truth was that the census disproved the accusations: 80 percent served on the front lines.”

Results and Reactions

The results of the census were never officially released by the army and any records of the census were most likely lost when the German military archives were destroyed during the allied bombing campaigns of Berlin and Potsdam. The episode marked a shocking moment for the Jewish community, which had passionately backed the War effort and displayed great patriotism; many Jews saw it as an opportunity to prove their commitment to the German homeland.

…

That their fellow countrymen could turn on them was a source of major dismay for most German Jews, and the moment marked a point of rapid decline in what some historians (Fritz Stern) called “Jewish-German symbiosis.”

(Digressing… Was there a German-Jewish symbiosis? As described by Yehuda Bauer in the Yad Vashem publication ”German-Jewish Symbiosis” – Against The Background Of The 30’s”, interviewed by Amos Goldberg in 1998:

Question: From a historical perspective, was the so-called “German-Jewish symbiosis” real or an illusion?

Answer: People talk today about a Jewish-German symbiosis that existed before Hitler. There was a love affair between Jews and Germans, but it was one-sided: Jews loved Germany and Germans; Germans didn’t love Jews, even if they didn’t hate them. One-sided love affairs usually don’t work very well. In this case, the so-called symbiosis between Jews and Germans is a postfactum invention. It never existed. Jews participated in German life, in German cultural life, but to say that they were accepted, even if the product they produced was accepted…. They were not accepted, even if they converted.”)

You can read much more about the above topic in Alexander Gelley’s essay “On the “Myth of the German-Jewish Dialogue”: Scholem and Benjamin”, particularly noting his reference to Gershon Scholem’s essay, “Against the Myth of the German-Jewish Dialogue,” from On Jews and Judaism in Crisis.

Back to the Judenzählung… Reproduced as the Appendix (pp. 167-168) of Werner Angress’ 1978 Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook article “‘Judenzählung’ of 1916 Genesis – Consequences – Significance”, here’s an image of the questionnaire used for the survey: ‘Nachweisung uber noch nicht zur Einstellung gelangte, auf Reklamation zuriickgestellte und als kr.u. [kriegsuntauglich] befundene Juden’. [‘Proof of items that have not yet been discontinued, are deferred following a complaint and are considered Jews found [unfit for war]’. The document is from the Bundesarchiv Koblenz, Reichskanzlei, Film 2197, No. 161 (Sections A and B); and ibid., No. 161 a (Section C).

✡ ✡

Angress discusses the origin, implications, and impact of the Judenzählung are discussed in great detail, concluding that the contemporary and retrospective significance of the Judenzählung – was it portentous or not? – must understood in the context and contingencies of history:

“We may ask, in conclusion, whether the Judenzdhlung was a watershed, a milestone on the road to Auschwitz as has been occasionally maintained. For those who reject the inevitability of human events – and most historians do – the answer must be in the negative. Antisemitism had been a part of the German scene before the First World War and remained a potent force during the brief life of the Weimar Republic, though here, too, its intensity fluctuated. Granted that during the First World War antisemitism had gained new strength, and that the War Ministry’s Erlass [order] of 11th October 1916 was a direct outgrowth of this trend. But taken by itself, the Judenzdhlung — a tactless blunder committed by a handful of high-ranking and most probably antisemitic army officers – was a symptom, a warning sign that antisemitism in Germany was alive and well, especially in times of stress and national reverses. More than this it did not signify. If the course of German history during the post-war period had taken a different direction from that which it ultimately did take – and this possibility existed at least until 30th January 1933, if not beyond that date – the Judenzdhlung would have remained a mere episode, a humiliation like others before, remembered with distaste, but ultimately shrugged off as just another manifestation of Risches [modernism; radicalism] on the part of Wilhelminian Germany’s military elite.”

Though a subject of straightforward academic interest several decades later (but no longer in the early 21st Century, it seems!) the Judenzählung most definitely impacted German Jewish soldiers on an individual level. Though I don’t know if – and I doubt that – any large-scale research as ever been done into any still-extant letters and diaries of German Jewish veterans of the Great War pertaining to their reactions to the census, the event did have an impact – an extremely significant, life changing impact – upon a writer whose future oeuvre focused upon themes of the First World War, the European Jewish experience in the early twentieth century, and to a lesser extent (*ugh*) socialism (oh well, two out o’ three ain’t bad!): Arnold Zweig.

As variously recounted by Noah William Eisenberg, Martin Grabolle, and Bernd-Rüdiger Hüppauf, Zweig, then a private in the German Army, a, “loyal Vaterlandsverteidiger (defender of the Fatherland),” so patriotic as to have been married in uniform in 1916, was very deeply affected by the implications of the Judenzählung. As he described in a letter of February 15, 1917 to Martin Buber written from the Maas Front (quoted by Martin Grabolle), “Judenzählung war eine Reflexbewegung unerhörter Trauer über Deutschlands Schande und unsere Qual; kein Essay sondern ein Bild… Wenn es keinen Antisemitismus im Heere gabe: die unerträgliche „Dienstpflicht“ wäre fast leicht. Aber: verächtlichen und elenden Kreaturen untergeben zu sein! Ich bezeichne mich vor mir selbst als Zivilgefangen und staatenlosen Ausländer.“ [“’The Census of the Jews’ was a reflex movement of unheard-of grief over Germany’s shame and our torment; not an essay but a picture… If there were no anti-Semitism in the army: the unbearable “duty” would be almost easy. But: to be subordinate to contemptible and miserable creatures! I refer to myself a civil prisoner and a stateless alien.”]

The then twenty-nine year old private’s response was to pen an extraordinarily vivid short fictional piece that was macabre, haunting, grotesque, and yet (with intended irony?) – by the tale’s end – deeply inspirational, entitled “Judenzählung vor Verdun” [The Jewish Census at Verdun].

Inwardly, Zweig was transformed by the census. According to Martin Grabollle, “Where not too long ago Zweig had celebrated the new-found unity of the German people, he now felt himself to be a foreigner without a state (“staatenlose[r] Ausländer). All that remained two years after his embrace of Germany at war was a feeling of “unerhörte Trauer über Deutschlands Schande und unsere Qual” (“enormous grief for Germany’s disgrace and our [the Jews’] pain”).”

Outwardly, Zweig was also transformed. Quoting Eisenberg, “…in June, 1917, he was transferred to the Eastern region of Ober-Ost (in Lithuanian Kovno) to serve in the special wartime press division. There, as he traveled to the various shtetls in Lithuania, Zweig witnessed for the first time the problems that the Eastern Jews faced during the war – animosity and ill-treatment from both sides of the battle – and, more importantly, the unique community they maintained in the face of such contradictions.” One result of his spiritual and intellectual metamorphosis appeared six years later, in the volume Das ostjüdische Antlitz [The Eastern Jewish Face], produced in collaboration with artist Hermann Struck.

The first commentary about the Judenzählung (that I know of!) was a leading page editorial by “M.M.” in the October 27, 1916 issue of Judische Rundschau. M.M. correctly surmises that, “The tendency of those who introduced the resolution is clear. An anti-Semitic suspicion should be given special weight by a parliamentary resolution.” The author then discusses the influence on the position of Jewish citizens in the Allied countries resulting from the Allies’ alliance with Imperial Russia, but notes that such a factor was irrelevant in Germany, since anti-Jewish feeling in that country was in some ways already parallel to – but obviously independent of – Russian influence. The editorial explains that even as early as 1916, despite the valor, sacrifice, and patriotism of German Jewish soldiers, there was, and would be, no commensurate “improvement in the political position of German Jews after the war”. He then correctly explains that antisemitism is entirely unrelated to the actions and beliefs of Jews, instead being primarily “rooted in the consciousness of the surrounding people”. M.M. concludes with the imperative of collectively establishing Jewish life on a common territory, albeit naively concluding (the naivete can be forgiven given the what we know in 2023, let alone what was known in 1948, let alone the 1930s) that a Jewish nation-state would actually reduce antisemitism.

Here’s an English-language translation of “M.M.’s” editorial about the Judenzählung, from the October 27, 1916, issue of Judische Rundschau, via Goethe University.

The Jewish Census [Alternatively, “Count of the Jews”]

On October 19, 1916, the Budget Commission of the German Reichstag resolved to compile statistics on the denomination of the people employed in the wartime societies. The decision is justified by the fact that the survey is intended to refute “a widespread opinion” that there were a particularly large number of “Jewish slackers” in the war societies. The Reichstag plenum has not yet approved the implementation of the resolution, but the symptomatic fact is sufficient that the representatives of all factions belonging to the commission, with the exception of the Liberals and Social Democrats, i.e. also the National Liberals and clericals, voted in favor of the resolution. The tendency of those who introduced the resolution is clear. An anti-Semitic suspicion should be given special weight by a parliamentary resolution. The result of the inquiry will not be according to the applicants’ secret wishes. Because even if, which is by no means certain, a larger number of Jews were to be employed in the German wartime societies, that would still not be proof of “Jewish shirking”. The proportion of Jews in German economic life is proportionately greater than that of the rest of the population, and it has rightly been pointed out that the number of indispensable Jews in other occupations closed to Jews is all the smaller.

There has been much talk lately of the pernicious influence which the alliance of the western powers with Russia had on the position of the Jews of those countries. Conservative and clerical German newspapers also stated that the French and British governments gave in to pressure from St. Petersburg and gave the anti-Semites of both countries a freer hand, not without condemning references to the bad effects of the Russian reaction. The anti-Semites of Germany do not seem to have needed this Russian pressure in order to shame the German Jews by a measure that would do even Russian Jew-baiting credit. The statistics passed by the budget commission of the German Reichstag are in line with some Russian army orders, about which the entire German press, including the conservative and clerical ones, broke the baton. About the Russian secret order that the Russian soldiers should observe the attitude of their Jewish comrades-in-arms very closely and provide information about it for statistical purposes, there was only one voice in the German press of indignation. As much as German Jews should consider it beneath their table dignity to justify themselves against the anti-Semitic insinuation that there is a specifically “Jewish shirking,” they have a duty to protest against this “census.” It is a monstrous violation of the honor and civil equality of German Jewry.

The decision of the German Reich Budget Committee has another meaning. It confirms the fear that German anti-Semitism did not decrease during the war and that hopes for an improvement in the political position of German Jews after the war are premature. Since the outbreak of the war, certain Jewish circles in Germany had been full of high hopes for the post-war period, reveling in envisioning the brilliant civic position which the Jews would enjoy after the war in recognition of their patriotic and military prowess, and could not do enough in apologetic references to the patriotic attitude of German Jewry. They will have to see that anti-Semitism is not, as they think, a reaction to “bad Jewish habits” but a power deeply rooted in the consciousness of the surrounding people, which is even sometimes – and not only in Russia – used to distract attention the masses of burning but uncomfortable domestic issues. This deep-rooted anti-Semitic mood is neither erased by apologies and references to merits, nor even diminished by the striving for conformity. There is only one way to effectively combat hatred of Jews. It is the way of redeeming the Jews from their isolation by concentrating on a common territory. And even if this goal can only be reached through the work of generations, striving for it improves our situation among the peoples. Objectively, in that the virtues of pride and self-dignity, developed through the uncompromising emphasis on Jewish characteristics, wrested more respect for the Jews from the surrounding peoples than the unstable method of assimilation, subjectively, insofar as the defense against anti-Semitism, albeit with all the honorable means of the carried out with passion and acumen, will only make up a modest part of our Jewish life. Only when the work for the restoration of the Jewish people in our own land has become our main Jewish focus will we be able to fight anti-Semitism effectively and at the same time reduce it to the natural degree that its importance in Jewish life is: an annoying defense against intolerance and slander coming from the outside. – M.M.

✡ ✡

Here’s the editorial, in the original German…

Judenzählung

Die Budget-Kommission des Deutschen Reichstags hat am 19. Oktober 1916 den Beschluss gefasst, eine Statistik über die Konfession der in den Kriegsgesellschaften beschäftigten Personen vorzunehmen. Der Beschluss wird damit begründet, dass durch die Erhebung “eine weit im Volke verbreitete Meinung” widerlegt werden soll, wonach in den Kreigsgesellschaften besonders viel “jüdische Drückeberger“ sässen. Noch hat das Reichstagsplenum die Durchführung des Beschlusses nicht genehmigt, aber es genügt die symptomatische Tatsache, dass die Vertreter aller Fraktionen, die der Kommission angehören, mit Ausnahme der Freisinnigen und Sozialdemokraten, also auch die Nationalliberalen und Klerikalen, für die Resolution stimmten. Die Tendenz derer, die den Beschluss einbrachten, liegt klar zutage. Einer antisemitischen Verdächtigung soll durch Parlamentsbeschluss besonders Gewicht gegeben werden. Das Ergebnis der Enquete wird nicht nach den geheimen Wünschen der Antragsteller ausfallen. Denn wenn auch, was durchaus nicht feststeht, in den deutschen Kriegsgesellschaften eine grössere Anzahl Juden angestellt sein sollte, so wäre das noch kein Beweis für die “jüdische Drückebergerei”. Der Anteil der Juden am deutschen Wirtschaftsleben ist verhältnismässig grösser als der der übrigen Bevölkerung und mit Recht hat man darauf hingewiesen, dass die Zahl der jüdischen Unabkömmlichen in anderen, Juden verschlossenen Berufszweigen um so geringer ist.

Man hat in letzter Zeit viel von dem schädlichen Einfluss gesprochen, den das Bündnis der Westmächte mit Russland auf die Lage der Juden dieser Länder hatte. Die französische und englische Regierung hat, so konstatierten auch konservative und klerikale deutsche Blätter nicht ohne verurteilenden Hinweis auf die schlimmen Wirkungen der russischen Reaktion, dem Drucke Petersburgs nachgegeben und den Antisemiten beider Länder freiere Hand gegeben. Dieses russischen Druckes scheinen die Antisemiten Deutschlands nicht bedurft zu haben, um die deutschen Juden durch eine Massnahme an den Schandpfahl zu stellen, die selbst russischen Judenhetzern alle Ehre machen würde. Die von der Budget-Kommission des deutschen Reichstags beschlossene Statistik steht mit manchen russischen Ameebefehlen in einer Reihe, über die die gesamte deutsche Presse auch die konservative und klerikale, seinerzeit den Stab brach. Ueber den russischen Geheimbefehl, die russischen Soldaten sollten die Haltung ihrer jüdischen Mitkämpfer genauestens beobachten und darüber zu statistischen Zwecken Auskunft geben, herrschte im deutschen Blätterwald nur eine Stimme der Entrüstung. So sehr es die deutschen Juden unter ihrer tische Wurde halten sollten, sich gegen die antisemitische Insinuation, es gäbe eine spezifisch “jüdische Drückebergerei,” zu rechtfertigen, so sehr haben sir die Pflicht, gegen diese “Zählung” zu protestieren. Sie ist eine ungeheuerliche Verletzung der Ehre und der bürgerlichen Gleichstellung des deutschen Judentums.

Der Beschluss des deutschen Reichshaushaltausschusses hat noch eine andere Bedeutung. Er bestätigt die Befürchtung, dass der deutsche Antisemitismus während des Krieges nicht abgenommen habe und dass die Hoffnungen auf eine Besserung der politischen Stellung der deutschen Juden nach dem Kriege verfrüht seien. Gewisse jüdische Kreise Deutschlands waren seit Ausbruch des Krieges voll hochgespannter Hoffnungen für die Zeit nach dem Weltkrieg, schwelgten im Ausmalen der glänzenden staatsbürgerlichen Stellung, deren sich die Juden in Anerkennung ihrer patriotischen und militärischen Bewährung nach dem Kriege zu erfreuen haben werden, und konnten sich nicht genug tun in apologetischen Hinweisen auf die vaterländische Haltung des deutschen Judentums. Sie werden einsehen müssen, dass der Antisemitismus nicht, wie sie meinen, eine Reaktion auf “schlechte jüdische Gewohnheiten” ist, sondern eine im Bewusstsein des umgebenden Volkes tiefwurzelnde Macht, deren man sich sogar manchmal – und nicht bloss in Russland – zur Ablenkung des Interesses der Massen von brennenden, aber unbequemen innerpolitischen Fragen bedient. Diese tiefwurzelnde antisemitische Grundstimmung wird weder durch Apologie und Hinweis auf Verdienste aus der Welt geschafft, noch durch das Streben nach Anpassung auch nur vermindert. Es gibt nur einen Weg zur wirksamen Bekämpfung des Judenhasses. Es ist der Weg der Erlösung der Juden aus ihrer Vereinzelung durch Konzentrierung auf einem gemeinsamen Territorium. Und wenn dieses Ziel auch erst durch die Arbeit von Generationen erreich bar sein wird: schon das Streben nach ihm bessert unsere Lage unter den Völkern. Objektiv, indem die durch die kompromisslose Betonung der jüdischen Eigenart entwickelten Tugenden des Stolzes und der Selbstwürde den umgebenden Völkern mehr Achtung gegen den Juden abringen als die haltlose Anpassungs-methode, subjektiv, insofern die Abwehr gegen die Judenfeindschaft, wenn auch mit allen ehrenhaften Mitteln der Leidenschaft und des Scharfsinns durchgeführt, nur noch einen bescheidenen Teil unseres jüdischen Lebensinhaltes ausmachen wird. Erst wenn die Arbeit für die Wiederherstellung des jüdischen Volkes im eigenen Lande zu unserem jüdischen Hauptinhalt geworden ist, werden wir den Antisemitismus wirksam bekämpfen und seine Bekämpfung zugleich auf das natürliche Mass zurückführen können, das seiner Bedeutung für das jüdische Leben zukommt: einer lästigen Abwehr gegen Intoleranz und Verleumdung, die von aussen kommt. – M.M.

…and, as it actually appeared in the newspaper…

…where it can be found on the newspaper’s front page, comprising two columns.

✡ ✡ ✡

The first appearance of “Judenzählung vor Verdun” was in the February, 1917 (Volume 13, Issue 1) issue of Die Siegfried Jacobsohn’s Die Schaubühne (The Theater). Here (…drum roll!!…) is an English-language translation of the tale.

The Jewish Census at Verdun

At midnight a soft hand touched me: “Get up”. I stepped in front of the door of the silent bunkhouse and saw: “Azrael, cherub who commands the dead, fell from the night sky – vengeful anger – blew the shofar and cried: “To the count, you dead Jews in the German army!”

Before long the field swarmed with silent figures up to the rolling hills, behind which the Fortress of Verdun roared, fanned anew, and their little bastards roared loudly; flames erupted terribly, twitching and shattering the wailing night on the gun’s horizon. The wind flew from Orion, which hung feebly over the heights in dim veils. Murmurs trembled over the area; a gloomy glow surrounded thousands. A table stood, a large book open, and a clerk in uniform sat behind it, pointy-nosed with yellow hair. He called:

“Line up according to rank! The roll of names of the people is to be recognized!” Then a gentle voice said: “Oh, why don’t you let us sleep, since we were already lying in the restful arms of the earth!” And the writer: “Statistics ask how many of you Jews pressed themselves to their graves from the distant war.” Groans rose from the ground, as if the earth was wailing, and the voice cried out painfully:

“Great fatherland, I intended to die and rest for you!” But a whirlwind stirred the dead; they stood at the table one after the other, captains and medical officers first and lieutenants and doctors, sergeants and watch-masters, non-commissioned officers, privates, common soldiers. And the scribe put a dry quill in each hand; it flowed like a scratched finger; each one wrote his Hebrew name in small red letters that shone like square seals. There the corpses stood patiently and waited, and whoever wrote silently placed on the table the badges he wore and stood back, as one in the crowd. There lay the thick epaulettes of the medical officers and the silver ones of the officers, sword knots like silver eggs, the braids of the non-commissioned officers, the small batons of the Rod of Asclepius, the big buttons of privates; the Iron Crosses of the First Class and like many of the Second Class, other crosses and medals, black and white ribbons in all sorts of colors. But the heap swelled on the table.

The quiet men approached, wrote and became a crowd. The outline of the old body surrounded it like a light aura, phosphorescent like rotten wood; but the darker core was given by the body which was laid in the grave in due time. The bellies were eaten away by typhus and hollowed out by dysentery. Their heads showed holes from bullets, half of their skulls had been carried off by grenades, arms were missing, broken legs and ribs protruded from tattered uniforms; they were bandaged, clothed in rags, without boots; dead eyes looked gloomy, white light fell from lowered foreheads, the dead were silent in shame and mourning. Youngsters stood next to boys and young men next to mature ones. And they stated how old they were and where they were born: everywhere in Germany, and what their professions were: teachers and lawyers, rabbis and doctors, travelers, many students of all faculties, pupils, painters, young poets, merchants, craftsmen and merchants in turn and merchants again and again. And where fallen; where did they lie in the grave? Near Lille, they said, and Pozieres, all along the Somme, Thiaumont it was called and Azannes, Fleury and Vaux, Champagne, Argonne, Vosges, all of Flanders (they lay in the damp ground the longest); Bzuraklangs, East Prussia, the Carpathians, the Slota Lipa (which was called Sanward), Kovno and Dunaburg, Volhynian swamp, Hungarian forest, Serbian mountain, Galician valley: and Azrael, the angel, nodded at everyone, he had sown them like seeds, thrown far away here; there. Everything was written down in the book, the pen moved, small red letters appeared on the pale sheet. But a bright cross shone over the forehead of some who were baptized; the writer asked everyone: Jew? And he nodded, he said, “You know”; he said, “Mosaic denomination”; “Israelite” he said, “German of Jewish faith” – “Jew, yes” some said and stretched, and the crosses faded from everyone. And as the freshest stood at the table, almost still bleeding, blown from Romania, the Dobruja, the Somme…

The moon lost its shine, the wind blew more violently into the darkness, Azrael raised his hand, the field lay empty, overgrown with scattered light. Night fell, all black, blazing at the edge of the forge of Verdun roaring behind the heights.

But the dead Jews could no longer stand at the bottom of their graves. They sank; slowly and soullessly the bodies slid deeper down, deeper down. A river, black and soundless, flowed in the veins of the earth, taking it up and rolling it eastward; each one became a round cylinder, shrunk, became as big as a brick and very soft. And it threw them out in the early morning, flowing under palm trees into the light of a jubilant sun that rose from the sea. But a tall man with a broad black beard, a reproachful look and a workman’s apron, the trowel lying to his right and his naked sword to his left, seized each one and pressed it; it became hard as a stone in the sun and laid it into low masonry, and the stream threw roller after roller at his feet. The waller put stone next to stone; he didn’t look up. An old man came up to him and greeted him, a young smile lay like dawn on old rock over the weather-beaten forehead and the aged beard. “Greetings to he who builds the tower,” he said, and: “Thanks to him who has seen the daughter of Zion,” answered the builder and set a stone. “The daughter of Zion is on her way,” said Akiba, and the maker blushed with happiness. But I could no longer contain myself: “Oh Akiba,” I cried, “when will the Messiah come?” His gaze examined my soul. “At the gates of Rome a hunchbacked beggar, the Messiah, sits and waits,” said he; it frightens me like a threat. “What is he waiting for, Master?” I cried out in fear. “For you,” said the old man and turned. And I awoke to a sudden, glaring, heart-breaking shock.

✡ ✡

Some comments…

Note how Zweig introduces the tale with mention of “Azrael”, the angel of death.

Wikipedia reveals that – oddly – while the figure of “Azriel” is mentioned in the Zohar, neither “Azrael” or “Azriel” appear in the Tanach or Talmud, also stating that, “… the name Azrael is suggestive of a Hebrew theophoric עזראל, meaning “the one whom God helps,” and that, “Archeological evidence uncovered in Jewish settlements in Mesopotamia confirm that it was indeed at one time used on an Aramaic incantation bowl from the 7th century. However, as the text thereon only lists names, an association of this angelic name with death cannot be identified in Judaism.”

Azrael is a much more significant figure in Islam, being one of the four archangels, the others being Jibrāʾīl, Mīkāʾīl, and Isrāfīl. The only mention of the name in the context of Christianity is in the Ethiopic version of Apocalypse of Peter (dating to the 16th century), where Azrael – spelled as Ezrā’ël – appears is an angel of hell who avenges those who had been wronged during life.” In a much different sense, Azrael appears in the works of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and G. K. Chesterton’s, and in the world of the Smurfs, as the evil wizard Gargamel’s cat.

And so, the tale…

And then… A “whirlwind” stirs the dead. At Azrael’s command, after a momentary protest, the spirits of fallen Jewish soldiers rise from the sleep of death within in their graves, and stand before the angel.

And then… One after another in line, without regard to rank, the spirits stand before a table upon which lies an open book, upon which they inscribe their names in small, block-like Hebrew letters, with a quill given to them by Azrael.

And then… Nearby, they deposit their insignia of rank and medals in a swelling pile.

And then… Zweig’s tale becomes explicit; macabre, grotesque. The fatal wounds of the fallen are described in graphic detail; then, their professions or vocations are given; then, they state where they fell. This is are also recorded by each man’s spirit. Every fallen soldier appears as a phosphorescent aura with a dark, inner core, the latter vaguely implied to still lie within his grave.

And then… Those Jews who had been baptized are also standing before Azrael, bright crosses shining above their foreheads. As they identify themselves as members of the “Mosaic denomination”, “Israelites”, or “Germans of Jewish faith”, the crosses fade away.

And then… The souls and bodies of the dead are transformed. They sink into the earth, roll eastward, and with this they shrink to the size of bricks, take on the shape of cylinders, become pliable and soft, and move eastward under the sea, until they emerge under a bright sun, in a land of sunlight and palms.

And then… As each brick is taken up by a black-bearded mason with a sword and trowel it hardens, and is pressed into a wall of masonry. And the process continues, brick by brick.

And then… Akiba (Rabbi Akiba) and the anonymous mason greet one another, the former anticipating the arrival of the Daughter of Zion.

And then… The anonymous narrator implores of Akiba to know the date of the Messiah’s arrival. And as Akiba turns away, he reveals that the Messiah’s arrival depends, “on you”: on the narrator himself.

And finally… From nightmare, from dream, from mystical vision, the narrator awakens…

And then…?

Here’s the tale in the original German:

Judenzählung vor Verdun

Um Mitternacht rührte mich eine leise Hand an: “Steh auf”. Ich trat vor die Tür der schweigenden Schlafbaracke und sah: “Azrael, Cherub, der über Tote gebietet, stürzte vom Nachtfirmament herab, rachegeflügelter Zorn, stiess ins Horn Schofar und schrie: “Auf zur Zählung, ihr toten Juden im deutschen Heer!”

Es verging keine Zeit, da wimmelte das Feld von leisen Gestalten bis an die gebogenen Hügel, hinter denen brüllte die Feste Verdun, neu angefacht, und ihre kleinern Essen brüllten laut; Flammen schlugen furchtbar auf, zuckend zerbrach am Horizont des Geschützes die wehklagende Nacht. Der Wind flog vom Orion her, der schwach über den Höhen hing in trüben Schleiern. Raunen bebte übers Gelände, düsterer Schein umwitterte Tausende. Ein Tisch stand, aufgeschlagen ein grosses Buch, ein Schreiber sass in Montur dahinter, spitznäsig mit gelbem Schopf. Er rief:

“Antreten dem Range nach! Die Totenstammrolle ist anzuerkennen!” Da sagte eine milde Stimme: “Oh warum lasst ihr uns nicht schlafen, da wir schon lagen in der Erde Arm ruhevoll!” Und der Schreiber: “Die Statistik fragt, wieviel von euch Juden sich vom fernern Krieg gedrückt ins Grab.” Stöhnen steig auf vom Gelände, als klagte der Boden, und die Stimme rief schmerzlich:

“Grosses Vaterland, ich gedachte für dich zu sterben und zu ruhn!” Aber ein Wirbel bewegte die Toten, sie standen am Tische einer nach dem andern, Hauptleute und Stabsärzte zuvor und Leutnants und Aerzte, Feldwebel und Wachtmeister, Unteroffiziere, Gefreite, Gemeine. Und eine dürre Feder gab der Schreiber in jede Hand, sie floss wie ein geritzter Finger, seinen hebräischen Namen schrieb ein jeder in kleinen roten Lettern, die leuchteten wie quadratische Siegel. Da standen die Leichname geduldig und warteten, und wer geschrieben, der legte schweigend die Abzeichen auf den Tisch, die er trug, und trat zurück, einer in der Menge. Da lagen die dicken Achselstücke der Stabsärzte und die silbernen der Offiziere, Portepees wie silberne Eier, die Tressen der Unteroffiziere, die kleinen Aeskulapstäbe, die grossen Knöpfe der Gefreiten; die Eisernen Kreuze der Ersten Klasse und wie viele der Zweiten, andre Kreuze und Medaillen, schwarzweisse Bänder in allerlei Farben. Der Haufen schwoll aber auf dem Tische.

Die stillen Männer traten heran, schrieben und wurden Menge. Wie eine leichte Aura umgab sie der Umriss des alten Leibes, phosphoreszierend wie faules Holz; aber den dunklern Kern gab der Körper, den man ins Grab gelegt zu seiner Zeit. Die Bäuche waren zerfressen vom Flecktyphus und ausgehöhlt von Ruhr. Ihre Köpfe wiesen Löcher auf vom Geschoss, halbe Schädel hatten Granaten entführt, Arme mangelten, Beine, Rippen zerbrochen drangen aus zerfetzten Uniformen; sie waren mit Verbänden umwickelt, mit Lumpen bekleidet, ohne Stiefel; erloschene Augen blickten düster, von gesenkten Stirnen fiel weisser Schein, die Toten schwiegen in Scham und Trauer. Da standen Jünglinge bei Knaben und junge Männer neben reifen. Und sie gaben an, wie alt sie seien und wo geboren: überall im deutschen Land, und was für Berufe: Lehrer und Rechtsanwälte, Rabbiner und Aerzte, Reisende, viele Studenten aller Fakultäten, Schüler, Maler, junge Dichter, Kaufleute, Handwerker und Kaufleute wiederum und immer wieder Kaufleute. Und wo gefallen, wo lagen sie im Grabe? Bei Lille, sagten sie, und Pozieres, die ganze Somme entlang, Thiaumont hiess es und Azannes, Fleury und Vaux, Champagne, Argonnen, Vogesen, ganz Flandern, die lagen am längsten im feuchten Grund; Bzura klangs, Ostpreussen, Karpathen, die Slota Lipa, der San ward genannt, Kowno und Dünaburg, wolhynischer Sumpf, ungarischer Wald, serbischer Berg, galizisches Tal: und Azrael nickte, der Engel, bei jedem, er hatte sie ausgesät wie Samenkörner, weit geworfen, hierhin, dorthin. Alles stand verzeichnet im Buche, die Feder bewegte sich, kleine rote Buchstaben erschienen auf dem bleichen Blatte. Manchen aber leuchtete ein helles Kreuz über der Stirn, die waren getauft; der Schreiber fragte jeden: Jude? Und er nickte, er sagte: “Sie wissen doch”; er sagte: “Mosaischer Konfession”; “Israelit” sagte er, “Deutscher jüdischen Glaubens” – “Jude, ja” sprach mancher und streckte sich, und die Kreuze verblichen jedem. Und wie die frischesten am Tische standen, fast noch blutend, aus Rumänien hergeweht, der Dobrudscha, der Somme…

Der Mond verlor der Schein, Wind wehte heftiger ins Dunkel, Azrael hob die Hand, das Feld lag leer, überbuscht von zerstiebendem Scheine. Nacht brach herein, ganz schwarz, am Rande zerloht von der Esse Verdun brüllend hinter den Höhen.

Aber es war den toten Juden kein Halt mehr auf dem Grund ihrer Gräber. Sie sanken, langsam glitten und seelenlos tiefer die Körper abwärts, tiefer hinab. Ein Strom, schwarz und lautlos, floss in den Adern der Erde, er nahm sie auf und wälzte sie ostwärts; runde Walze wurde jeder, schrumpfte, ward gross wie ein Ziegel und ganz weich. Und er warf sie aus im frühen Morgen, mündend unter Palmen ans Licht einer jubelnden Sonne, die stieg aus dem Meer. Ein grosser Mann aber mit schwarzem, breitem Bart, dem rügenden Blick und der Schürze des Werkmannes, die Kelle rechts neben sich liegend und links das nackte Schwert, ergriff einen jeden und presste ihn, er ward in der Sonne hart zum Stein und gefüat in ein niederes Mauerwerk, und Walze neben Walze warf der Strom ihm zu Füssen. Stein neben Stein setzte der Mauernde, er sah nicht auf. Ein Greis trat zu ihm und grüsste ihn, ein junges Lächeln lag wie Morgenrot auf altem Fels über verwitterter Stirn und dem greisen Barte. “Gegrüsst sei, der am Turme mauert”, sagte er, und: “Gedankt dem, der die Tochter Zions erblickt hat”, antwortete der Baumeister und setzte einen Stein. “Die Tochter Zions ist auf dem Wege”, sprach Akiba, und der Schaffer errötete vor Glück. Ich aber konnte nicht mehr an mich halten: “Oh Akiba”, rief ich, “wann kommt der Messias!” Sein Blick prüfte meine Seele. “Vor den Toren Roms sitzt ein buckliger Bettler, der Messias, und wartet”, sprach er; mich erschreckt’ es wie Drohung. “Worauf wartet er, Meister? rief ich voll Angst. “Auf dich” sprach der Greis und wandte sich. Und ich erwachte vor jähem, grellem, herzerneuerndem Schreck.

This is Zweig’s text as published in Siegfried Jacobsohn’s Die Schaubühne (Band 13, Ausgabe 1 [Volume 13, Issue 1]). You can see that it appears on three successive pages.

And…here are the cover and title pages of the same issue of Die Schaubühne, which can be found at OogleBooks.

✡ ✡ ✡

Zweig’s tale is as vivid, as it is haunting, as it is compelling. Below, I’ve transformed it into a prose poem, the appearance of which, though entirely identical in content to the original text, perhaps lends it a degree of visual impact not apparent in the text in the original paragraph format.

The Jewish Census at Verdun

At midnight a soft hand touched me:

“Get up”.

I stepped in front of the door of the silent bunkhouse and saw:

“Azrael, cherub who commands the dead, fell from the night sky –

vengeful anger –

blew the shofar and cried:

“To the count, you dead Jews in the German army!”

Before long the field swarmed with silent figures up to the rolling hills,

behind which the Fortress of Verdun roared,

fanned anew,

and their little bastards roared loudly;

flames erupted terribly, twitching and shattering the wailing night on the gun’s horizon.

The wind flew from Orion, which hung feebly over the heights in dim veils.

Murmurs trembled over the area; a gloomy glow surrounded thousands.

A table stood, a large book open,

and a clerk in uniform sat behind it, pointy-nosed with yellow hair.

He called:

“Line up according to rank!

The roll of names of the people is to be recognized!”

Then a gentle voice said:

“Oh, why don’t you let us sleep,

since we were already lying in the restful arms of the earth!”

And the writer:

“Statistics ask how many of you Jews pressed themselves to their graves from the distant war.” Groans rose from the ground,

as if the earth was wailing, and the voice cried out painfully:

“Great fatherland, I intended to die and rest for you!”

But a whirlwind stirred the dead;

they stood at the table one after the other,

captains and medical officers

first and lieutenants and doctors,

sergeants and watch-masters,

non-commissioned officers, privates,

common soldiers.

And the scribe put a dry quill in each hand;

it flowed like a scratched finger;

each one wrote his Hebrew name in small red letters that shone like square seals.

There the corpses stood patiently and waited,

and whoever wrote silently placed on the table the badges he wore and stood back,

as one in the crowd.

There lay the thick epaulettes of the medical officers and the silver ones of the officers,

sword knots like silver eggs,

the braids of the non-commissioned officers,

the small batons of the Rod of Asclepius,

the big buttons of privates;

the Iron Crosses of the First Class and like many of the Second Class,

other crosses and medals, black and white ribbons in all sorts of colors.

But the heap swelled on the table.

The quiet men approached, wrote and became a crowd.

The outline of the old body surrounded it like a light aura,

phosphorescent like rotten wood;

but the darker core was given by the body which was laid in the grave in due time.

The bellies were eaten away by typhus and hollowed out by dysentery.

Their heads showed holes from bullets,

half of their skulls had been carried off by grenades,

arms were missing,

broken legs and ribs protruded from tattered uniforms;

they were bandaged, clothed in rags,

without boots;

dead eyes looked gloomy,

white light fell from lowered foreheads,

the dead were silent in shame and mourning.

Youngsters stood next to boys and young men next to mature ones.

And they stated how old they were and where they were born:

everywhere in Germany,

and what their professions were:

teachers and lawyers,

rabbis and doctors,

travelers,

many students of all faculties,

pupils,

painters,

young poets,

merchants,

craftsmen and merchants in turn and merchants again and again.

And where fallen; where did they lie in the grave?

Near Lille, they said, and Pozieres, all along the Somme,

Thiaumont it was called and Azannes,

Fleury and Vaux,

Champagne,

Argonne,

Vosges,

all of Flanders (they lay in the damp ground the longest);

Bzuraklangs,

East Prussia,

the Carpathians,

the Slota Lipa (which was called Sanward),

Kovno and Dunaburg,

Volhynian swamp,

Hungarian forest,

Serbian mountain,

Galician valley:

and Azrael, the angel, nodded at everyone,

he had sown them like seeds, thrown far away here; there.

Everything was written down in the book,

the pen moved, small red letters appeared on the pale sheet.

But a bright cross shone over the forehead of some who were baptized;

the writer asked everyone:

Jew?

And he nodded, he said, “You know”; he said,

“Mosaic denomination”;

“Israelite” he said,

“German of Jewish faith” –

“Jew, yes” some said and stretched, and the crosses faded from everyone.

And as the freshest stood at the table, almost still bleeding,

blown from Romania, the Dobruja, the Somme…

The moon lost its shine,

the wind blew more violently into the darkness,

Azrael raised his hand,

the field lay empty, overgrown with scattered light.

Night fell, all black,

blazing at the edge of the forge of Verdun roaring behind the heights.

But the dead Jews could no longer stand at the bottom of their graves.

They sank; slowly and soullessly the bodies slid deeper down, deeper down.

A river, black and soundless, flowed in the veins of the earth,

taking it up and rolling it eastward;

each one became a round cylinder, shrunk, became as big as a brick and very soft.

And it threw them out in the early morning,

flowing under palm trees into the light of a jubilant sun that rose from the sea.

But a tall man with a broad black beard,

a reproachful look and a workman’s apron,

the trowel lying to his right and his naked sword to his left,

seized each one and pressed it;

it became hard as a stone in the sun and laid it into low masonry,

and the stream threw roller after roller at his feet.

The waller put stone next to stone; he didn’t look up.

An old man came up to him and greeted him,

a young smile lay like dawn on old rock over the weather-beaten forehead and the aged beard. “Greetings to he who builds the tower,” he said, and:

“Thanks to him who has seen the daughter of Zion,” answered the builder and set a stone.

“The daughter of Zion is on her way,” said Akiba, and the maker blushed with happiness.

But I could no longer contain myself:

“Oh Akiba,” I cried, “when will the Messiah come?”

His gaze examined my soul.

“At the gates of Rome a hunchbacked beggar, the Messiah, sits and waits,” said he;

it frightens me like a threat.

“What is he waiting for, Master?” I cried out in fear.

“For you” said the old man and turned.

And I awoke to a sudden, glaring, heart-breaking shock.

An observation…

Zweig’s concluding paragraph struck a distant chord of memory within me. I vaguely remembered that I’d encountered a legend concerning the resurrection of the dead in Messianic days, to the effect that they will literally roll across land and under sea to reach Eretz Israel. My memory was correct, and was verified at Jack Zaientz’s blog, “Jewish Monster Hunting: A Practical Guide to Jewish Magic, Monsters, and Mayhem”, in his post “First we die. Then we roll. A “Rolling To Jerusalem” Subway Map.” This references Talmud, Kettubot 111a (3) at Sefaria, in which the following debate is recorded:

וּלְרַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר, צַדִּיקִים שֶׁבְּחוּץ לָאָרֶץ אֵינָם חַיִּים?! אָמַר רַבִּי אִילְעָא: עַל יְדֵי גִּלְגּוּל. מַתְקֵיף לַהּ רַבִּי אַבָּא סַלָּא רַבָּא: גִּלְגּוּל לְצַדִּיקִים צַעַר הוּא! אָמַר אַבָּיֵי: מְחִילּוֹת נַעֲשׂוֹת לָהֶם בַּקַּרְקַע.

“The Gemara asks: And according to the opinion of Rabbi Elazar, will the righteous outside of Eretz Yisrael not come alive at the time of the resurrection of the dead? Rabbi Ile’a said: They will be resurrected by means of rolling, i.e., they will roll until they reach Eretz Yisrael, where they will be brought back to life. Rabbi Abba Salla Rava strongly objects to this: Rolling is an ordeal that entails suffering for the righteous. Abaye said: Tunnels are prepared for them in the ground, through which they pass to Eretz Yisrael.”

Another observation…

There’s “something” about the concluding three sentences of Zweig’s text:

“What is he waiting for, Master?” I cried out in fear.

“For you” said the old man and turned.

And I awoke to a sudden, glaring, heart-breaking shock.

Specifically, there’s a remarkable similarity to the closing lines of Franz Kafka’s “Before the Law”:

“What do you still want to know, then?” asks the gatekeeper.

“You are insatiable.”

“Everyone strives after the law,” says the man,

“so how is that in these many years no one except me has requested entry?”

The gatekeeper sees that the man is already dying and,

in order to reach his diminishing sense of hearing, he shouts at him,

“Here no one else can gain entry, since this entrance was assigned only to you.

I’m going now to close it.”

In both cases, the anonymous narrator implores of an authority figure – Rabbi Akiva, or, “the gatekeeper” – that his future course of action, or, secret knowledge, be revealed. The two answers lead to dramatically different outcomes: In Zweig’s tale, the narrator lives, and, transformed, faces a perhaps revised future, which is entirely dependent on his choice of action. In Kafka’s story, the narrator is at the point of death, the outcome of events – perhaps preordained by circumstance or providence? – having already been preordained for him.

I have no idea of the degree of Kafka and Zweig’s familiarity with one another’s works, but they were contemporaries, the former having been 29 years old in 1916, and the latter 32. Being that “Before the Law” (“Vor dem Gesetz”) was published in the 1915 New Year’s edition of the independent Jewish weekly Selbstwehr, the possibility exists that the final lines of “Judenzählung vor Verdun” were inspired by Zweig’s reading of Kafka’s tale.

Having come this far, one can readily appreciate Zweig’s literary talents. The piece is short – a little less than a thousand words in length – yet even with this economy of words, the imagery of the tale is stunning in its clarity, in terms of physical setting, atmosphere, mood, and the description of the fallen as both spirit and body; spirit in body.

✡ ✡ ✡

Arnold Zweig, 1916 (From deutsche-kinemathek)

✡ ✡

Arnold Zweig, New York City, 1939 (Photo by Eric Schaal)

✡ ✡

Arnold Zweig, Haifa, Yishuv, 1939 (Photographer Unknown)

✡ ✡ ✡

I’ve not read any other works by Zweig, but given his skill and imagination; his ability to so powerfully craft scene and mood; the era in which he was active – the first half of the twentieth century – I can readily envision him – if the trajectory of his life had been different, having been a masterful and successful writer of pulp fiction, perhaps in the genres of adventure, fantasy, or horror. Perhaps his work would have appeared in such pulps as The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction; Weird Tales; Unknown; Fantastic Novels. It’s nice to speculate…

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, December, 1950 (Absolutely wonderful cover art! – by Chesley Bonestell) (From my own collection.)

Fantastic Novels, July, 1950 (Cover art by “Lawrence” (Lawrence Sterne Stevens)), illustrating Moore and Kuttner’s “Earth’s Last Citadel”) (Also from my own collection. (Shameless self-promotion!) See more of such, here.)

✡ ✡ ✡

Zweig’s macabre story concludes by transitioning to a scene of transformative and mystical renewal – an explicitly collective renewal – with startling abruptness, revealing to the narrator; to the reader – to us, even and especially in this year of 2023 – that to the Jews is granted the ability to return.

And so, in symbolic answer to the anonymous narrator’s awakening, let’s wordlessly conclude with an allegorical image entitled “Der Jüdische Mai” [“The Jewish May”], from Ephraim Moses Lilien’s, Sein Werk, published in 1903 in Berlin. (Specifically, page 280 in volume 2.)

For your consideration: Some references…

Arnold Zweig, at…

… United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

… Kuenste im Exil [Art in Exile]

… Deutsche Kiemathek [German Cinema Library]

… University of Massachusetts DEFA Film Library

… Geni.com

Die Schaubühne [“The Stage”], at …

… Wikipedia (Die Weltbühne)

… University of Michigan Digital Library

Die Schaubühne (Band 13, Ausgabe 1 [Volume 13, Issue 1]), pages 115-117…

…at OogleBooks

Siegfried Jacobsohn, at…

Franz Kafka, at…

“Before the Law”, at…

Azrael, at…

Some books…

Eisenberg, Noah William, Between Redemption and Doom – The Strains of German-Jewish Modernism, University of Nebraska Press, 1999

Grabolle, Harro, Verdun And the Somme, Akademiai Kiado, Budapest, Hungary, 2004

Hüppauf, Bernd-Rüdiger, War, Violence, and the Modern Condition, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, Germany, 1997

Franz Kafka – The Complete Stories

Lilien, Ephraim Mose, and Zweig, Stefan, E. M. Lilien, Sein Werk, mit einer Emleitung von Stefan Zweig, band zwei, Schuster & Loeffler, Berlin, Germany, 1903, OCLC 7720842

Vital, David, A People Apart – A Political History of the Jews in Europe, 1789-1939, Oxford University Press, 2001

Vital, David, A People Apart – A Political History of the Jews in Europe, 1789-1939, at GoodReads.com

Wenzel, Georg, Arnold Zweig, 1887-1968 : Werk und Leben in Dokumenten und Bildern : mit unveröffentlichten Manuskripten und Briefen aus dem Nachlass [Arnold Zweig, 1887-1968: Work and life in documents and images: with unpublished manuscripts and letters from the estate], Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin, 1978

Zweig, Arnold, and Struck, Hermann, Das ostjüdische Antlitz [The Eastern Jewish Face], Berlin Weltverlag, Berlin, Germany, 1922

(Das ostjüdische Antlitz includes many, many thematic sketches by Hermann Struck, none of which, unfortunately, have captions. (Oh, well!) This drawing of a young woman appears on page 112.)

Some articles…

Angress, Werner T., The German Army’s “Judenzahlung” of 1916 Genesis – Consequences – Significance, Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook, V 23, N 1, 1978

Gelley, Alexander, On the “Myth of the German-Jewish Dialogue”: Scholem and Benjamin, University of California, Irvine, 1999

Goldberg, Amos, “German-Jewish Symbiosis” – Against the Background of the 30s – Excerpt from interview with Professor Yehuda Bauer, Director of the International Center for Holocaust Studies of Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, Israel

And, otherwise…