As part of my ongoing series of posts about Jewish soldiers who were the subjects of news coverage by The New York Times during the Second World War, “this” post relates stories of Jews who served in the air forces of the WW II Allies, specifically pertaining to events on March 19, 1945. As you’ll see, some of these men survived, and others did not.

I’ll have additional blog posts about Jewish aviators involved in military actions on this day, all of a quite lengthy and detailed nature. These will pertain to 1 Lt. Bernard W. Bail, 1 Lt. Nathan Margolies, and three flyers in the USAAF’s 417th Bomb Group, F/O Samuel Harmell, S/Sgt. Jerome W. Rosoff, and S/Sgt. Seymour Weinbeg.

But, for now…

For those who lost their lives on this date…

Monday, March 19, 1945 / 5 Nisan 5705

– .ת.נ.צ.ב.ה. –

…Tehé Nafshó Tzrurá Bitzrór Haḥayím

May his soul be bound up in the bond of everlasting life.

United States Army Air Force

8th Air Force

452nd Bomb Group

730th Bomb Squadron

From the Roger Freeman collection at the American Air Museum in England is this example of the 730th Bomb Squadron insignia.

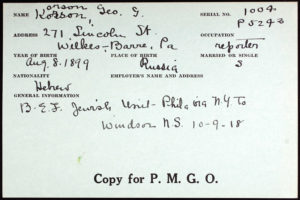

Here is a parallel: F/O Arthur Burstein (T-132844) and 2 Lt. Marvin Rosen (0-2068473) were both navigators in the 452nd Bomb Group’s 730th Bomb Squadron. Their aircraft – B-17G Flying Fortresses – were shot down by Me-262 jet fighters during a mission to Zwickau, Germany, crashing near that city, and both were taken captive. Both men were interned in POW camps – the specific locations of which are unknown – and like their fellow crewmen, both returned to the United States after the war’s end.

Burstein was one of the ten airmen aboard aircraft 43-38368 – “M”, otherwise known as “Daisy Mae”, piloted 2 Lt. Victor L. Ettredge, from which the entire crew survived. As reported in MACT 13562 (it’s a short one; only five pages long), Daisy Mae was struck by fire from the Me-262s just before bombs away. The aircraft left the formation with its right wing aflame and was not seen again. Between one and two crew members were seen parachuting from the plane. (Which would suggest that the entire crew survived by parachuting from the damaged aircraft.)

This photo of Daisy Mae is American Air Museum in Britain image UPL45784.

Rosen was aboard 43-37542, otherwise known as “Smokey Liz II”, piloted by 2 Lt. William C. Caldwell. As reported in MACR 13561, this B-17 was also hit by cannon fire from the jet fighters, and then peeled off to the right with its left wing and one engine aflame. Two parachutes emerged from the bomber, and it was again attacked by an Me-262. Lt. Caldwell then radioed that he had two engines out and was heading for Soviet occupied territory, with his co-pilot – 2 Lt. Walter A. Miller – wounded.

Postwar Casualty Questionnaires in the MACR – one filed by Lt. Rosen, and the other by a unknown crew member in the rear of the aircraft – reveal that ball turret gunner S/Sgt. John S. Unsworth, Jr., was instantly killed when a cannon shell struck his turret, and waist gunner Sgt. David L. Spillman, though uninjured, failed to deploy his parachute after bailing out, probably due to anoxia from leaving his aircraft at an altitude above 10,000 feet. Co-pilot Miller was in reality uninjured, but was still in the cockpit and about to bail out – following his flight engineer – when the bomber exploded.

Otherwise, the MACR lists the specific calendar dates when the seven survivors of “Smokey Liz II” returned to military control after liberation from POW camps. For Lt. Rosen, this occurred on April 29, forty days after the March 19 mission.

F/O Burstein was son of David and Ann B. Burstein, of 198 Cross Street in Malden, Massachusetts, and was born in that city on March 9, 1923. Later promoted to the rank of Second Lieutenant (0-2015029), his name is absent from American Jews in World War II.

Information about Lt. Rosen is far more substantial. He was the husband of Theresa J. Rosen of 713 1/2 North 8th Street in Philadelphia, and, the son of Abraham Rosen of 5144 North 9th St. and Regina (Weiss) Rosen of 1717 Nedro Ave., both of which are also Philadelphia addresses. His name appeared in the Jewish Exponent on May 4, 1945, the Philadelphia Inquirer on April 21, and the Philadelphia Record on April 28. Page 546 of American Jews in World War II notes that he received the Air Medal, indicating the completion of between five and nine combat missions. Born in Philadelphia on May 17, 1925, he passed away at the unfairly young age of forty on July 22, 1965. He’s buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Section 37, Grave 4747.

452nd Bomb Group

729th Bomb Squadron

This example of the 729th Bomb Squadron insignia, item FRE5188, is also from Roger Freeman collection at the American Air Museum in England.

Aboard the 729th Bomb Squadron’s B-17G 42-97901, otherwise known as “Helena”, three crewmen were wounded: flight engineer Jim Rohrer, radio operator John Owens, and co-pilot Stanley G. Elkins. The aircraft, piloted by Lt. Richard J. Koprowicz (later “Kopro“), force landed behind Soviet lines at Radomsko, Poland, and was salvaged on March 28. Lt. Koprowicz and his eight crew members remained with a Russian Commandant in what had previously been a Gestapo quarters. On March 29, the crew flew aboard a C-47 (or a Soviet Lisunov-2?) to Poltava, where they remained until May, eventually returning to Deopham Green on May 15. No MACR was filed pertaining to the loss of Helena.

According to the American Air Museum in Britain, the timing of this event resulted in Lt. Koprowicz and his waist gunner Mountford Griffith completing a total of two missions by the war’s end. For the rest of the crew, the March 19 mission was their first, last, and only mission.

2 Lt. Stanley Garfield Elkins (0-757166) was the husband of Isabel G. Elkins and father of Pamela, 2522 Kensington Ave., Philadelphia, and, the son of Minnie Elkins, who lived at 353 Fairfield Avenue in the adjacent suburb of Upper Darby. His name appeared in a Casualty List published on April 26, and can also be found on page 518 of American Jews in World War II. Born in Philadelphia on August 8, 1921, he died on January 20, 1993, and is buried at Indiantown Gap National Cemetery in Annville, Pa.

Along with Daisy Mae, Helena, and Smokey Lizz II, the 452nd lost two other B-17s on the Zwickau mission, albeit in such circumstances that no MACRs were filed for these incidents. 43-38231, “Try’n Get It”, piloted by Warren Knox (with nine crewmen), force-landed on a farm near Poznan. 43-38205, “Bouncing Babay”, piloted by a pilot surnamed “Daniel”, force-landed at Maastricht Airfield in Belgium. There were no fatalities or injuries among the crewmen of these two planes.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

96th Bomb Group

339th Bomb Squadron

This example of the 339th Bomb Squadron insignia was found at RedBubble.

“I had made so many missions with _____ and the rest of the crew,

that it was just like losing one of your own family.”

(T/Sgt. Steele M. Roberts)

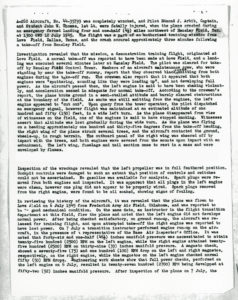

Like most of his fellow crew members on his 25th mission, T/Sgt. Herbert Jack Rotfeld (16135148) was the radio operator aboard B-17G 44-8704 during the 96th Bomb Group’s mission to Ruhland, Germany. The un-nicknamed Flying Fortress was leading either the 339th Bomb Squadron (in particular) or the 96th Bomb Group (in general) when, at 24,000 feet – its bomb-load not yet having been released due to weather conditions – it was struck by flak and its right wing began to burn. Pilot Captain Francis M. Jones and copilot 1 Lt. David L. Thomas pulled the B-17 away from the 96th to the right, and either they or bombardier 1 Lt. George M. Vandruff jettisoned their bombs.

The aircraft then went into a spin, and upon descending to 16,000 feet, broke apart.

Of the ten men aboard the plane (the aircraft being an H2X equipped B-17 it had a radome in place of the ball turret, and thus a radar operator in place of the ball turret gunner) only two succeeded in escaping: Navigator 1 Lt. Harold O. Brown and flight engineer T/Sgt. Steele M. Roberts, whose crew positions were both in the forward fuselage. As reported by Lt. Brown in his postwar Casualty Questionnaire, “Sgt. Roberts flying as top gunner was [the] first one aware of our peril and after being certain he could no longer assist pilot, dove to catwalk under pilot compartment, released door, and jumped,” to be followed by Brown himself.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

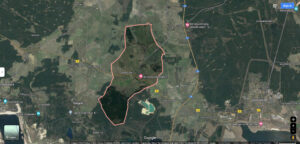

The location of the incident is listed in the MACR as 51-37 N, 13-33 E, but the aircraft actually fell to earth east of that location, crashing 500 meters northeast of the German village of Wormlage.

In this Oogle view, Worlmage lies just to the right, and down a little, from the center of the map, about halfway between Cottbus and Dresden. It’s indicated by the set of red dots just to the west of highway 13.

This is a map view of Wormlage at a vastly larger scale…

…while this is an air photo (or satellite?) view of the village at the same scale as above.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The bomber’s crew comprised:

Command Pilot – Barkalow, Lyman David, Capt., 0-802517

Pilot – Jones, Francis Maurice, Capt., 0-764688

Co-Pilot – Thomas, David L., 1 Lt., 0-713570

Navigator – Brown, Howard O., 1 Lt., 0-2062638 – Survived (jumped second from forward escape hatch)

Bombardier – Vandruff, George Martin, 1 Lt., 0-776834

Mickey Operator – Spiess, Joseph Dominic, 1 Lt., 0-733323

Flight Engineer – Roberts, Steele M., T/Sgt., 33288642 – Survived (jumped first from forward escape hatch)

Radio Operator – Rotfeld, Herbert Jack, T/Sgt., 16135148

Gunner (Waist) – Zajicek, Martin T., S/Sgt., 36698781

Gunner (Tail?) – Fagan, Dale Eugene, S/Sgt., 37539473

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Sgt. Roberts returned to his home in Pittsburgh on June 23, 1945, and on that date or very shortly after, sent the following letter to the families of his eight fallen fellow crew members. The very immediacy of the document … “I just landed in Newport News on Monday … (and) finally reached home late Saturday” … says a great deal about Sgt. Roberts and this crew, while its contents shows a striking degree of tact and sensitivity. Truly, this man was an excellent writer. Sgt. Roberts sent a copy of his letter to the Army Air Force in response to their inquiry about his crew, the document then being incorporated into MACR 13571.

That’s how you’ve come to read it here, nearly eight decades later.

Here it is:

This letter was sent to each of the families.

Am writing you in regards to our ill-fated mission of March 19th. I just landed in Newport News on Monday, June 18th, and after being sent to a couple of camps, finally reached home late Saturday. Knowing your anxiety, I am writing immediately to give you the details as I know them.

Our mission on March 19th was over a district South West of Berlin, and our first target was to have been Ruhland, but the visibility was so poor that we were unable to drop any bombs, however, the enemy flak was quite heavy and finally was successful in hitting one of our wings and set it afire. The ship was maneuvered to take it out of formation so that it would not interfere with the other ships. When a wing is on fire it is hard to steer, and went into a spin. The navigator and myself were the only ones who were able to jump before it went into the spin. When a ship is in a spin, it is practically impossible to move. We left the ship at about 22000 feet and landed in enemy territory, and were held over night in a very small village, the name of which I do not know, about 25 miles S.W. of Ruhland at our rally point.

The next morning I was taken to the scene of the wreckage, apparently to identify the ship and the rest of the crew. I did not give definite information to the enemy, but satisfied myself in regards to the identity of my friends. In a small church yard the entire group of my buddies were laid out peacefully, as is asleep. They did not seem to be married in any way, although this seemed impossible after such a fall. I was in such a daze that I could hardly comprehend the magnitude of sorrow that could confront one so quickly. I had made so many missions with [space for crew member’s name] and the rest of the crew, that it was just like losing one of your own family. Immediately after identification, I was taken to another prisoner camp and the next day I was again moved, and finally taken to Barth, near the Baltic.

I am sorry I cannot give the detailed location of interment, as I was moved about so quickly from one place to another by the Germans. It is possible that Navigator Brown could be more specific in location of towns.

Please excuse any seemingly bluntness in my statements, but I know that you wanted the plain facts. You have my greatest sympathy, and if I can, in any way, be of more assistance to you, do not hesitate to make the request.

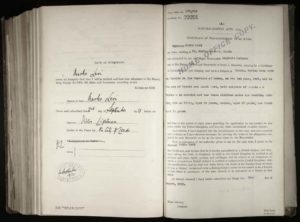

Sgt. Steele Roberts’ letter, as found in MACR 13571:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

T/Sgt. Rotfeld was the son of Morris and Gertrude Rotfeld, the family living at 3625 West Leland Ave. in Chicago, while his brother Isidor lived at 300 South Hamlin Street in the same city. He was born in Chicago on November 16, 1922. The recipient of the Air Medal with three Oak Leaf Clusters and Purple Heart, his name can be found on page 114 of American Jews in World War II.

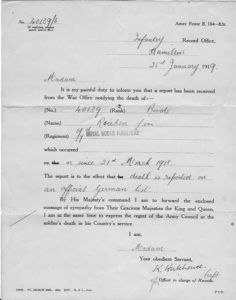

He is buried at Plot A, Row 7, Grave 4 in the Ardennes American Cemetery in Neupre, Belgium, but his burial – specifically in his case on August 4, 1953 – and that of the rest of his fallen crew members) only occurred over nine years after the mission of March 19. This is largely attributable to Wormlage having been within the postwar Soviet occupation zone of Germany in the context of the first (?!) Cold War, which presented huge challenges for the American Graves Registration Command. Evidence of this can be seen in the following letter of 1948, from Sergeant Rotfeld’s Individual Deceased Personnel File:

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

(Germany M-52) 4214

BERLIN DETACHMENT (PROV)

FIRST FIELD COMMAND

AMERICAN GRAVES REGISTRATION COMMAND

EUROPEAN AREA

BERLIN, GERMANY

19 Oct 1948

NARRATIVE OF INVESTIGATION

SENFTENBERG (N-52/A-34)

At 0930 hrs, 19 Oct 1948, the undersigned with Sgt. Altman, a Soviet escort officer from Kalrshorst and a Soviet Major with a German civilian interpreter from the Kommandantura [“military government headquarters; especially a Russian or interallied headquarters in a European city subsequent to World War II”] called on Burgomeister Hans Weiss in his office in Senftenberg. We had asked to be taken to the Standesamt [“German civil registration office, which is responsible for recording births, marriages, and deaths.”] to check the Kreis [“primary administrative subdivision higher than a Gemeinde (municipality)”] records but were refused this request.

The head of the Standesamt, Max Beschoff, was summoned. He brought no records with him but he was sure that, as far as his records were concerned, all Americans who had been buried in cemeteries in his Kreis were disinterred and taken away by American troops. He did, however, say that his records were incomplete because Allied deceased had been buried in Kreis cemeteries and cemetery officials had neglected to furnish the Standesamt with information of all burials, especially during the latter part of 1944 and the early part of 1945.

The Soviets were not cooperative. The Burgomeister’s words were carefully checked by them. He was told that he could help us in a quiet sort of way but that there could be no Bekamtmachungen [public notice] or any inquiries that would attract public attention. It appeared that the Burgeomeister wanted to help us but could do nothing under restriction for he said: that our stay in his Kreis was too short to accomplish our mission; and that people or officials summoned before us would not talk. He said that he would quietly canvass his entire Kreis and that he felt sure that in two weeks he would be able to give us the exact location of any isolated graves in his area.

Accordingly all the pertinent facts in cases in Calau, Drebkau and Gr. Raaschen were given to him.

A report should be received from him in about three weeks.

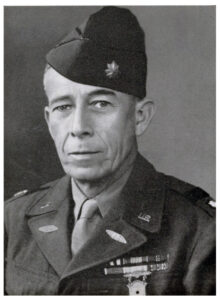

PAUL M. CLARK

Lt. Col. FA

Commanding

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

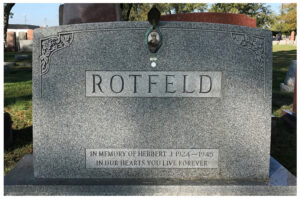

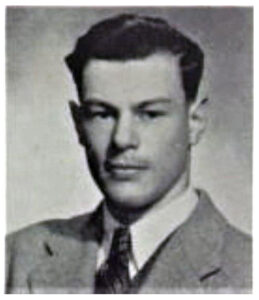

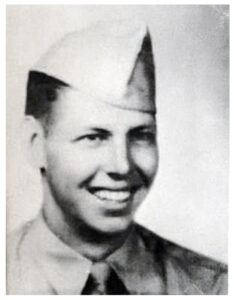

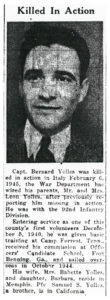

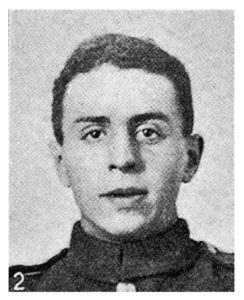

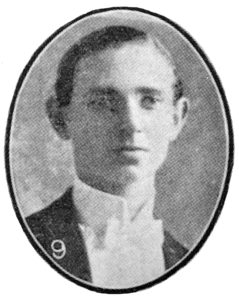

Here’s Sgt. Rotfeld’s portrait, as it appears in a ceramic plaque affixed to the top of his commemorative matzeva, at Waldheim Cemetery in Chicago. The incorporation of ceramic photographs of deceased family members upon tombstones seems to have been a not infrequent practice from the 20s through the 40s. (Photo by Johanna.)

Here’s the matzeva itself, also as photographed by Johanna.

This is Sgt. Rotfeld’s actual matzeva at the Ardennes American Cemetery, as photographed by David L. Gray.

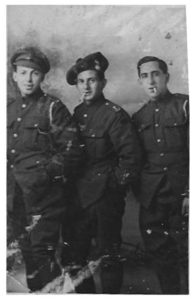

This is photograph UPL 32744 via the American Air Museum in Britain. Waist gunner S/Sgt. Martin J. Zajicek is at center rear, while T/Sgt. Steele M. Roberts is at right. If these four men were the four non-commissioned officers aboard 44-8704 on her final mission (as listed in the MACR), then the airman at far left may be S/Sgt. Dale E. Fagan, and the man in the center T/Sgt. Herbert J. Rotfeld, especially given his esemblance to the portrait in the photo attached to the matzeva in Chicago. (Just an idea, but I think an idea reliable.)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

According to Ancestry.com, Steele M. Roberts was born in Pittsburgh on September 25, 1921, to J.L. and Olive M. Roberts, his address as listed on his draft card as having been 8139 Forbes Street in that city. He passed away on February 11, 2000, and apparently (at least, going by FindAGrave.com) has no place of burial, for he was cremated.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

384th Bomb Group

547th Bomb Squadron

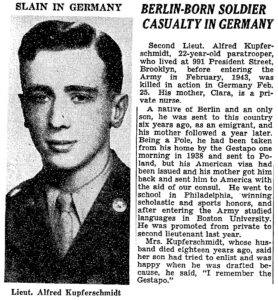

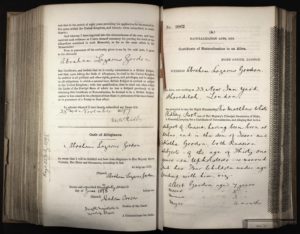

Second Lieutenant Herbert Seymour Geller (Hayyim Shlema bar Yaakov), 2 Lt., 0-2062494, was the son of “Jack” Jacob (4/22/00-2/4/90) and Ruth (Weinberg) (5/8/01-2/17/89) Geller, and brother of Harvey Don Geller (1/12/28-8/5/89), who resided at 18051 Greenlawn St., Detroit, Michigan. He was born in Detroit on March 23, 1923, and – as a B-17 Flying Fortress co-pilot – was killed on an operational mission on March 19, 1945, only four days short of his twenty-second birthday.

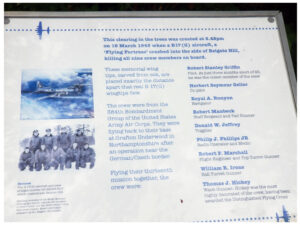

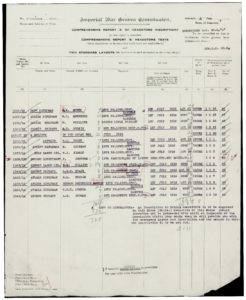

While serving aboard B-17G 43-39035 (“SO * F“), piloted by 2 Lt. Robert S. Griffin, his aircraft crashed into Reigate Hill, Surrey, England, while returning to the 384th’s base at Graton Underwood, Northamptonshire, from a mission to the Braunkhole-Benzin Synthetic Oil Plant at Bohlen, Germany, in an accident attributable to bad weather.

These photos, by FindAGrave contributor Dijo, show the, “Clearing in the trees at Reigate Hill, Surrey, England, created by the crash on 19.3.1945. A permanent reminder of their sacrifice.”…

… and, added by the National Trust, a “Memorial Plaque at the site of the aircrash.”

The Crew?

Pilot: Griffin, Robert Stanley, 2 Lt., 0-779854, San Diego, Ca. / Carson City, Nv.

Co-Pilot: Geller, Herbert S., 2 Lt., 0-2062494, Detroit, Mi.

Navigator: Runyon, Royal Arthur, 2 Lt., 0-806554, Keokuk, Ia.

Togglier: Jeffrey, Donald Walter, Sgt., 35900479, Des Moines, Ia.

Flight Engineer: Marshall, Robert Freeman, Sgt., 16116799, Racine, Wi.

Radio Operator: Phillips, Philip J., Jr., Sgt., 12225719, Highland Park, N.J.

Gunner (Ball Turret); Irons, William Randolph, Sgt., 6874192, N.J.

Gunner (Waist?): Hickey, Thomas J., Sgt., 12032033

Gunner (Tail): Manbeck, Robert Franklin, S/Sgt., 37202047, Moran, Ks.

As is immediately evident from the plaque, none of the nine men aboard Griffin’s bomber survived. The incident is extensively covered at the Wings Museum’s on-line memorial to the crew – “B-17G Tail Number 43-39035” – which features two images of the crew, one seemingly in training, and the other in the snowy winter of 1944-1945 at Grafton Underwood. Though the Museum’s story states that the crew are all buried in England, certainly Lieutenants Griffin and Geller are buried in the United States, with Geller resting alongside his parents and brother at Section L, Row 6, Lot 29, Grave 316D in Machpelah Cemetery, at Ferndale, Michigan.

Regarding the un-nicknamed “SO * F“, the 384th Bomb Group website, an astonishingly comprehensive repository of information about the Group, its men, and planes, has – remarkably – two photos of the B-17 in flight, in a brilliantly contrailed sky. Here they are…

…while the history of the plane is available here...

…and the Griffin crew’s biography is here…

…and you can read the Accident Report for “SO * F’s” final mission (“45-3-19-521”) here.

In a “pattern” that has been seen before, and will be seen again, Lt. Geller’s name is absent from American Jews in World War II. This colorized image of the lieutenant is by FindAGrave contributor James McIsaac.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

15th Air Force

98th Bomb Group

343rd Bomb Squadron

Having thus far presented numerous (several? many? a lot?) of posts recounting the service of Jews in the WW II Army Air Force (and, Royal Air Force, and, Royal Canadian Air Force, and, other WW II Allied air forces), what is apparent is the not uncommon circumstance in which – at least for aircraft with several crew members, such as bombers – multiple crewmen on the same aircraft were Jews. In the overwhelming majority of such cases I think this was attributable to simple chance. But… An 8th Air Force veteran shot down on the Schweinfurt Regensburg mission of August 17, 1943, suggested to me that he surmised – but could never prove – that his 381st Bomb Group crew’s composition (co-pilot, navigator, and bombardier having been Jews) was not at all product of happenstance. Well. Be that as it may, the loss of B-24H Liberator 42-94998 (otherwise known as “white I“; truly otherwise known as “Hell’s Belles“) of the 98th Bomb Group’s 343rd Bomb Squadron on March 19, 1945, exemplifies this situation to an intriguing degree.

Missing during the 98th’s mission to Landshut, Germany (erroneously listed in MACR 13068 as in Austria), the plane’s pilot, 1 Lt. Donald B. Tennant, radioed at 1400 hours that, “…he had 2 engines feathered and was going to try and make Switzerland. He had called for fighter escort. His altitude was 14,000′ and the coordinates were 47 59 N, 13 39 E.”

The plane was not seen again. It never reached Switzerland, but its entire crew of eleven survived, as revealed in postwar Casualty Questionnaires in the Missing Air Crew Report. In an Instagram post by spartan_warrior.24 on May 6, 2023, pertaining to an Air Medal awarded to Flight Engineer Cpl. George C. Hennington, “All 11 crew members aboard the aircraft bailed out and survived, they were all taken POW on March 19th 1945 and were held at Stalag VIIA in Moosburg, Bavaria. The POW camp was liberated on April 29th 1945 by the 14th Armored Division.”

It seems that through a combination of timing – this was less than two months before the war in Europe ended – and remarkably good happenstance – the entire crew survived, with only one airman (Cpl. Robert V. Wolff) having been injured in the bailout – only the vaguest information is available about where the crew actually landed, and, the plane fell to earth. (There’s no Luftgaukommando Report.) All the men bailed out from the waist escape-hatch except for the pilots, who exited via the bomb-bay. The location of the bailout is given as the Austrian town of “Kirching”, “Kirchino”, and “Kirsching”, none of which can be found via either Oogle or Duck-Duck-Go, the closest match being “Kirchberg an der Pielach”, east-southeast of Linz. Viewing the totality of information, perhaps the best guess is that the plane and crew landed (in very different ways) in a mountain valley halfway between Salzburg and Wels, or, 30 km southeast of Linz.

This map shows the relative locations of Salzburg, Wels, and Linz. Whatever small fragments of 42-94998 that still survive are here. Somewhere.

Here’s the crew:

Pilot – Tennant, Donald Brooks, 2 Lt.

Co-Pilot – Canetti, Isaac B., 2 Lt.

Navigator – Gillespie, Arthur R., 2 Lt.

Bombardier – Marino, Philip A., 2 Lt.

Flight Engineer – Hennington, George C., Cpl.

Flight Engineer – Berger, Sam, T/Sgt.

Radio Operator – Richardson, Almon P., Cpl.

Gunner (Dorsal) – Yaffe, William J., Cpl.

Gunner (Nose) – Woods, Robert K., Cpl.

Gunner – Rapp, Alex, Cpl.

Gunner (Tail) – Wolff, Robert V., Cpl.

This image of Lt. Tennant is from FindAGrave contributor Sylvia Sine Whittaker

The Jewish members of the crew included co-pilot 2 Lt. Isaac S. Canetti, flight engineer Cpl. William Jerry Yaffe, and gunners T/Sgt. Sam Berger and Cpl. Alex Rapp. Though technically they’d be “casualties” by virtue of their MIA / POW status, by virtue of the fact that they were neither wounded nor injured, their names never appeared in the 1947 compilation American Jews in World War II … though strangely, the National Jewish Welfare Board was aware of Rapp’s military service.

Genealogical and other information about these men follows:

Canetti, Isaac S., 2 Lt., 0-2001884, Co-Pilot

Mr. and Mrs. Samuel and Esther Canetti (parents), 1309 Avenue U, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Mr. Jack S. Canetti (brother), 1317 East 15th St., Brooklyn, N.Y.

Born New York, N.Y., 8/29/23 – Died 5/13/04

Casualty List 4/19/45

American Jews in World War II – Not Listed

Yaffe, William Jerry, Cpl., 33796476, Flight Engineer

Mr. and Mrs. David (11/19/93-3/74) and Jeanette (1899-1964) Yaffe (parents), 6106 Washington Ave., Philadelphia, Pa.

Born Philadelphia, Pa., 11/15/24 – Died Florida, 5/29/15

Jewish Exponent 4/20/45, 6/8/45

Philadelphia Inquirer 5/26/45

Philadelphia Record 4/11/45, 5/26/45

American Jews in World War II – Not Listed

Berger, Sam, T/Sgt., 32973643, Gunner

Mr. and Mrs. Isaac (4/18/95-12/20/73) and Rose (Frankel) (6/23/95-7/24/75) Berger (parents), 317 East 178th St., New York, N.Y.

Born Bronx, N.Y., 1/26/25 – Died Turnbull, Ct., 4/15/04

American Jews in World War II – Not Listed

Rapp, Alex, Cpl., 32975594, Gunner

Mr. and Mrs. Leon and Gussie (Duchan) Rapp (parents), 1732 Nostrand Ave., Brooklyn, N.Y.

Born Brooklyn, N.Y., 5/14/20 – Died 10/1/83

Casualty List 4/19/45

American Jews in World War II – Not Listed

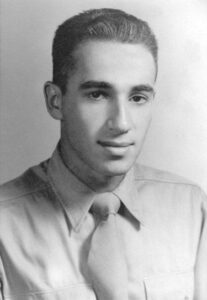

According to the Missing Air Crew Report, the March 19 mission was actually the eleven mens’ first and only mission as a crew, thus, no photograph of the men as a group would have existed. But, there are pictures of one crew member: Lt. Canetti. These come by way of Robin Canetti, his daughter. (Thank you, Robin!) This is her father in a pose quite formal…

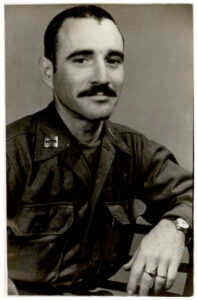

… while this image shows Lt. Canetti and a mostly unknown crew – not his original crew; perhaps in Italy with the 98th Bomb Group? – time and location unknown.

Lt. Canetti stands second from right in rear row, with Jess Bowling (in the middle) to his right. The only other man to whom a name can be attached is second from left in the front row: Wallace Pomerantz. Given the mens’ attire and positions within the photo, and Lt. Canetti’s presence in the rear row, the four (from the right) in the rear are presumably officers, with the the crew’s flight engineer to their right, while the five men in the front row are probably non-commissioned officers: gunners and radio operator.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

20th Air Force

505th Bomb Group

484th Bomb Squadron

According to Combat Squadrons of the Air Force, there exists no insignia for the 484th Bomb Squadron. Of this I am doubtful:: At RW Military Books, this history of the 505th Bomb Group displays what are apparently emblems for the group and its three component squadrons. It seems that these insignia were never incorporated into Army Air Force records.

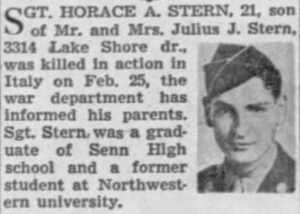

Sergeant Julius Manson (12100796), the son of Morris and Gertrude Manson, was born in New Jersey in 1926. He resided with his parents, and sisters Helen and Phyllis, at 57 Elm Street in Morristown.

A tail gunner in the 505th Bomb Group’s 484th Bomb Squadron, he was a crew member aboard B-29 42-24797, “K triangle 36“, much better known as “JACK POT”. The aircraft, piloted by 1 Lt. (later Colonel) Warren C. Shipp, was ditched 80 miles west of Iwo Jima on March 19, 1945, while returning from a mission to Nagoya, due to flak damage to three of its four engines. Due to a remarkable combination of skill, training, and luck, no members of the crew were seriously injured, all returning to combat duty. MACR 13694, which covers this incident, was presumably filed due to the crew technically being “missing” during the 48-hour time period between March 19, and their return to the 505th on March 21. Sgt. Manson’s very temporary “Missing in Action” status probably accounts tor the appearance of his name in a Casualty List published on April 24, 1945.

While MACR 13694 is straightforward and very brief in its description of the experience of Lt. Shipp’s crew, the historical records of the 505th Bomb Group, which are available on AFHRA (Air Force Historical Research Agency) Microfilm Roll / PDF B0675, include numerous very (very) detailed reports – some with sketches – covering the experiences of 505th crews who had survived ditching in the Pacific: some with outcomes akin to that of the Shipp crew, and others with outcomes tragic and far, far worse.

Here’s the crew:

Pilot: Warren C. Shipp, 1 Lt.

Co-Pilot: Don La Mallette, 2 Lt.

Navigator: Norman E. Shaw, 2 Lt.

Bombardier: William T. Smith, 2 Lt.

Radio Operator: William W. Tufts, Sgt.

Flight Engineer: Melvin G. Smith, 2 Lt.

Radar Operator: Finis Saunders, S/Sgt.

Gunner (Central Fire Control): Ernest B. Fairweather, Pvt.

Gunner (Right Blister): none

Gunner (Left Blister): Louis Molnar, Sgt.

Gunner (Tail): Julius Manson, Sgt.

The aircraft was ditched at 27-02N, 140-32 E, as shown in this Oogle map:

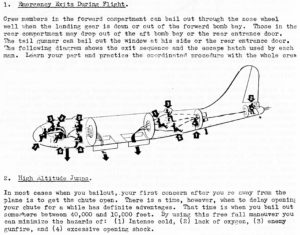

To give you an idea of the nature of such reports, here are excerpts from the ditching report for the Shipp crew and JACK POT:

Prior to Ditching:

While over the target the airplane was picked up by approximately 35 searchlights and although violent evasive action was taken, 50 seconds before bombs away a direct hit was suffered on number 2 engine which caused it to immediately burst into flames.

The engine was successfully feathered and no sooner were the flames put out than number 3 engine was hit and it proceeded to run away at an estimated 6000 to 7000 RPM. Power was reduced to 2300 RPM and 22 inches to keep number 3 engine running. At this time the turn was made off the target in the prescribed manner with the airplane diving to 5000 ft. to maintain an air speed of 160 MPH.

Upon leaving landfall celestial navigation was used to determine position before Loran was out, radar was of little value in that area, and DR was useless because of wavering instruments. With an IAS of 165 MPH the APC climbed to 7500 ft. to clearer weather and then set his course for Iwo Jima.

At approximately 0600 when about 200 miles north of the island number 1 engine lost 60 gallons of oil in ten minutes and started wind-milling at 2175 RPM.

With flight instruments lost, number 1 engine windmilling, number 2 engine feathered, number 3 engine giving limited power, and number 4 engine pulling 2500 RPM and 40 inches it appeared as though ditching were inevitable and after an unsuccessful attempt to start number 2 engine, distress signal procedures were instituted and the crew ordered to prepare for ditching.

Ditching – Airplane:

A let down was made through the undercast to 3000 feet at 500 to 600 feet per minute. The airplane was leveled out just above the water. The APC cut the power, pulled the nose up and stalled in at 95 MPH. (Estimated weight of airplane was 91,000 pounds and with full flaps stall speed was 95 MPH.)

The nose did not go under the water and only one impact was felt which was not too severe. No side deceleration was felt.

Although the airplane sank in 12 minutes water entered comparatively slow. The first man out reported 4” of water on the floor in the forward compartment and, the last man out reported water up to his shoulder.

The airplane broke in the radar room and as wave action took effect the tail broke off and sank. Other damaged to the airplane reported by the crew were the bomb-bay doors torn off at impact, skin was torn from the flaps and the propellers were curled.

The report includes two small diagrams depicting the effects of the ditching upon 42-24797. This one shows how the tail snapped off at the radar room.

Survival:

With the two seven man rafts (E-2) and the one individual raft (C-2) tied together the APC gave orders not to drink water or eat food for 48 hours. It was estimated that enough food and water was on board to last for 10 to 12 days. The navigator checked the drift course, and assisted in bailing water from the raft. He cleaned the emergency equipment, repacked it, and arranged a tarpaulin to protect the men from the constant spray.

The majority of the survivors were sick for the first few hours in the raft because they had swallowed so much sea water. They were constantly soaked to the skin by sea spray and although the water was warm the men were chilled by the cold winds. Ingenuity played its part when the crew had modified the C-1 vest to include a cellophane individual gas cover, M-1 which they used effectively to protect themselves from the weather.

Nine men wore the C-1 survival vest and experienced no difficulty in getting out of the airplane with them.

The Radar Corner Reflector type MX138A was installed in the raft and although the pip was observed on the Dumbo’s scope from a distance of a mile and half, the initial contact with the raft was made visually by use of flares.

Rescue:

When the survivors had been in the rafts from about 2 hours, seven or eight B-29s passed overhead but they were too high to see the rafts. _____ on B-29s flying north passed over at approximately 1000 feet and all attempts to contact them with signal mirrors failed. A constant vigil was maintained all that night.

The co-pilot and bombardier were on watch while the other men were under the tarpaulin when the Navy PBY was first sighted to the East of the rafts at about 1600 on the second day. The A.P.C. fired two flares which attracted the PBY from a distance of 5 miles.

Because there was no sun the signal mirrors were not used and the smoke bombs would not operate.

At 1645 a B-29 arrived on the scene and dropped survival equipment as did the Dumbo. However, because the rafts were drifting faster than the sustenance kits the kits never were retrieved.

As the first PBY and B-29 left, a relief PBY arrived on station and remained until the Destroyer Gatling arrived at 2100.

Contact was maintained by boxing the rafts with smoke bombs and by the use of sea marker. As darkness approached flares were dropped constantly and a floating light which was a part of the life raft equipment proved invaluable in maintaining contact. It was reported by the destroyer that the light was seen from a distance of eight miles.

The survivors were in the raft from 0635 on the 18th of March until 2100 on the 19th of March or approximately 38 hours, when they were rescued by the Destroyer Gatling. The crew was high in their praise of Naval efficiency in the manner of conducting the rescue.

On a level involving bureaucracy rather than military aviation (!), what’s particularly striking about these reports are the huge distribution lists appended to every document.

Here’s the distribution list in the report for 42-24797. (That’s lots of copies. Bureaucracy gone wild.)

DISTRIBUTION:

1 – Chief of Staff.

1 – Deputy Chief of Staff, Operations and Training.

1 – Deputy chief of Staff, Supply and Maintenance.

20 – A-2 (for separate distribution; 2 copies to Wing Historical Officer).

10 – Medical Section (for separate distribution).

15 – Wing Personal Equipment Officer.

1 – Statistical section.

1 – Communications Officer.

1 – Each Commanding Officer, each Bomb Group.

6 – Each Group Personal Equipment Officer.

1 – A-4 Maintenance.

1 – Reports Section.

INFORMATION COPIES TO –

30 – Commanding General, XXI B.C.

1 – Chief of Naval Operations, OP-16-V, Navy Dept., Washington, D.C.

1 – Commander Forward Areas, Central Pacific (Airmail).

1 – Commander Air Force, Pacific Fleet (Airmail).

1 – Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet (Airmail).

3 – Commanding Officer, Air Sea Rescue Unit, NAB Saipan.

3 – Commanding Officer, Marianas Surface patrol and Escort Groups, Saipan.

40 – each, 3rd Photo, 73, 314, 315, 316 Wings.

1 – Air Sea Rescue (CC&R), Washington, D.C.

1 – Air Sea Rescue & Personal Equipment Section, Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio.

1 – Capt. L.B. Carroll, Hqs., AAFPOA, APO 234 (Electronics Section)

20 – Commanding General, XX Air Force, Wash., D.C.

10 – Hqs., 2AF (21 Colorado Sprgs., Colo.).

2 – Air Surgeon Office, Wash., D.C.

5 – AAFTAC, Orlando. Fla.

1 – Commander 3rd Fleet, Fleet Post Office.

1 – Chief of Staff, XX Air Force, Wash., D.C.

1 – Commanding General, VII Fighter Command, APO 86, c/o PM, San Francisco, Calif.

6 – Deputy Commander, XX AF, AAFPOA, APO 953, c/o PM, San Fran., Calif.

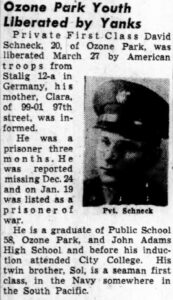

This portrait of Sgt. Manson, as he appeared in the 1943 edition of the Morristown High School Yearbook, is via Sam Pennartz (at FindAGrave)

The picture of “JACK POT” is from world war photos

This photo of “JACK POT” (along with other images of this aircraft, as well as other B-29s, like Slick’s Chicks) can be viewed at Jesse Bowers’ JustACarGuy’s blog. The caption: “Painter 1/C Edmund D. Wright, USNR, completed cartoon decoration of the plane, with nickname “Jackpot” and turns it over to Army air corps corporals Eugene H. Rees (center) and Marion V. Lewis (right), at Tinian, 1944-45. Wright was a member of the Navy 107th Seabee battalion which sponsored the plane and adopted its crew.” According to the Naval History and Heritage Command, the picture is NARA Catalog Number 80-G-K-2980. Another image of the bomber’s nose art is available at WorthPoint. The number of photographs of this B-29 suggest that (unsurprisingly) it was a rather popular aircraft, for an obvious reason.

Sergeant Manson survived the war, but in a tragic irony, he never returned.

He was one of the seven crewmen aboard B-29 44-70122, which – piloted by 2 Lt. Bernard J. Benson, Jr. – crashed in the Pacific Ocean on October 10, 1945, one of at least thirteen B-29s lost after hostilities with Japan ended. The loss of this 484th Bomb Squadron aircraft is covered in MACR 14951, which – like more than a few MACRs digitized by Fold3 – is (* ahem *) unavailable via NARA.

The recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with two Oak Leaf Clusters and Purple Heart, Sgt. Manson is commemorated upon the Tablets of the Missing at the Honolulu Memorial, Honolulu, Hawaii. His name can be found on page 245 of American Jews in World War II.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Air Transport Command

India China Division (formerly India China Wing)

This example of the Air Transport Command insignia is from the National Air and Space Museum.

This contemporary reproduction of the ICWATC insignia is from FiveStarLeather.

There’s a pattern here, a pattern evident in many – most? – all? – of my prior posts about Second World War military casualties, particularly those involving aviation: Akin to the stories of 2 Lt. Herbert S. Geller and Sgt. Julius Mason, and as will be seen “below” for F/Sgt. Saul David Lazarus of the Royal Air Force, are other men who were were involved in events that did not at all – directly – entail combat with the enemy. Such is the case of six Air Transport Command aircraft which were lost in the China-Burma-India Theater on March 19, 1945.

Of the six planes, Missing Air Crew Reports (from which the three following accounts are taken) were filed for two C-46As (43-47114 & 41-24716) and one B-24D (42-41253)), while Accident Reports were probably (?) filed for the those C-46s, as well as two C-47s and a C-109, the losses of the latter three planes not having been covered in MACRs.

Of the total of ten airmen aboard the C-46s and B-24, all six C-46 crewmen survived, by parachuting. The entire B-24 crew was lost.

In compiling these three accounts, of particular importance have been the historical records of the 1352nd Army Air Force Base Unit – India-China Detachment, which can be found in AFHRA microfilm roll / PDF A0159. The records of this unit, whose central mission was search and rescue, are astonishingly detailed by both wartime and even contemporary (as in 2024) standards, and might be deemed a kind of aviation archeology in “real-time”, for they include very detailed information about the search for and especially the identification of missing aircraft and airmen. This includes aircraft serial numbers, the specific location (as much as could have been determined given the technology of 1944 and 1945) of losses, descriptions of the condition of aircraft wreckage, and most importantly, the names, serial numbers, and fates of missing airmen. A few entries even cover the identification, description, and examination of crashed Japanese twin-engine bombers. Central to the 1352nd’s activities was Lieutenant William F. Diebold, whose wartime memoirs were transformed into the book Hell Is So Green: Search and Rescue Over The Hump In World War II, edited by Richard Matthews and published in 2012. A man of great physical courage with a love for adventure, Diebold – the veteran; the man; the person – was a very descriptive, perceptive, and sensitive writer. Alas, perhaps deeply affected by his war experiences, he had a very turbulent if not deeply unhappy postwar life, and, born in 1917, passed away in his late 40s, in 1965. His portrait, below, is from the dust jacket of Hell is So Green.

As for the lost C-46s and B-24, they were operated by the 1330th and 1333rd Army Air Force Base Units.

1330th Army Air Force Base Unit (7th Bomb Group)

On a cargo mission from Jorhat, India, to Chengking (Chungking) China, B-24D 42-41253 was last contacted by radio at 2200Z. At the time, weather conditions were reported as “600 ft. – Overcast 300 ft., scattered clouds, 3 miles visibility with rain shower. Light turbulence.”

Missing Air Crew Report 13130 and the records of the 1352nd AAFBU contain parallel information about the aircraft’s loss, the latter source being particularly detailed.

The MACR reports, “Aircraft #42-41253, B-24 type, was located through native reports of a crash approximately five miles west of the village of Shakchi, India, in the Naga hills. Distance from Jorhat, India is sixty miles on a heading of 125 degrees.”

The 1352nd’s records state that, “The aircraft struck the side of a ridge at about 4,500’ feet altitude while flying a heading of between 220o and 250o degrees.” … Aircraft having trouble, and was returning to Jorhat, in contact with Jorhat tower, last contact at 2200 at 10,500 ft. Aircraft crashed into side of a ridge at about 4,500 feet, 20 miles ENE of Mokokchung, and 5 miles W of Shakchi, India.

At the time MACR was compiled, the aircraft was believed to have been lost as a result of “Mechanical Trouble and Weather.” Given the fate of the crew and condition of the wreckage, the specific cause was – and will forever be – unknown: None of the aircraft’s four crew members survived.

The crew were:

Pilot: Armoska, Raymond M., Capt. 0-724666, Sterling, Il.

Co-Pilot: Gilliam, Bryan R., F/O, T-223731, Columbia, Tn.

Radio Operator: Schipior, Seymour, PFC, 32886005, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Flight Engineer: Paruck, Frank G., Sgt., 16142902, Chicago, Il.

Capt. Armoska and F/O Gilliam are buried in a common grave at Zachary Taylor National Cemetery, Louisville, Ky. (Section E, Grave 31) while Armoska’s name is also commemorated upon the Monument to Aviation Martyrs Nanjing Memorial, Nanjing, China. Sgt. Paruck is buried at Rock Island National Cemetery, Rock Island, Il. (Section D, Grave 316).

Private Schipior (Shlema Zalman bar Yehiel Meer ha Levi) is buried at Beth David Cemetery, in Elmont, N.Y. Born in Brooklyn on July 23, 1924, he was the son of Herman and Pearl, and brother of Nately and Scharlet. The family resided at 375 Pulaski Ave (possibly 794 Levis Ave.) Brooklyn. His name can be found on page 430 of American Jews in World War II.

7th Bombardment Group / Wing 1918-1995, pp. 247-248

The Aluminum Trail, p. 382

(Data from AFHRA Microfilm Roll A0159, Frame 620)

The red circle on the map below shows the approximate crash location of 42-41253: 5 miles west of the village or town of Shakchi, which itself is situated on this map at the “NH 702B” road symbol. Unsurprisingly, this region remains sparsely inhabited today, 79 years later.

Here’s an air photo view of the above area, with the crash location again designated by a red circle. A very rugged landscape.

With this photo, we’ve zoomed in close enough for Shakchi (at the right center of the map, as “Sakshi”) to be vaguely visible. The ridge into which 42-41253 crashed can clearly be seen.

A even closer view. The scale bar at upper left showing a distance of 0.25 miles. The terrain clearly suggests the difficulty of the search, rescue, and recovery of missing air crews.

1333rd Army Air Force Base Unit

PFC Morris Louis “Merny” Paster (12020499) was a radio operator aboard C-46A 41-24746, which went missing on a cargo flight between Chabua, India, and Kunming, China. Neither document gives a specific explanation for the aircraft’s loss, the MACR simply attributing the reason to “Weather of Mechanical Failure”.

Missing Air Crew Report 13171 is entirely absent of information about what befell the plane and crew, but does reveal that PFC Paster, his pilot (1 Lt. John J. Magurany, 0-802594) and co-pilot F/O William N. Hanahan (T-130416) all returned to military control. The two uninjured officers reached Chabua on March 22, while PFC Paster, hospitalized at Shingbwyiang with minor injuries, returned to duty at the 1333rd by March 24.

The 1352nd’s records reveal more about the loss of the aircraft and the return of its crew: Specifically listed as being on a flight from Tingkawk Sakan to Dergaon, the men parachuted 18 miles from Nawsing village, 260 degrees from Shingbwiyang. The crew “…made it a point to jump in rapid succession in order to be near each other on the ground.” Private Paster, “Walked into Shingbwiyang after spending one night with natives, and [was] hospitalized at there with minor injuries, returning on 3/24/45. Pilot and co-pilot were located by a ground party from 1352nd AAFBU and returned to unit on March 22.”

Like so very many American Jewish soldiers mentioned in my previous posts, PFC Paster’s name never appeared in American Jews in World War II, presumably because he simply neither received any military awards, nor was he specifically injured (or worse) in the first place. Born in Bukovina, Bulgaria on November 2, 1917, the twenty-seven year old airman resided with his mother Bertha (Tenenbaum) Paster at 744 Dumont Ave. in Brooklyn. Twenty-three years ago, he passed into history in the way of all men: He died on November 28, 2001, and is buried at Mount Zion Cemetery in Queens, New York.

(Data from AFHRA Microfilm Roll A0159, Frames 618-619)

This map shows 41-24746’s last reported position: 2 miles south of Shingbwyiang, Burma…

…while this air photo (at a slightly larger scale) reveals the rugged nature of the surrounding terrain.

The crew of the other 1333rd AAFBU C-46 lost on March 19 – 43-47114 – had an experience similar to that of 41-24746. Though MACR offers no real information about the aircraft’s loss other than the general explanation “Mechanical Failure”, the 1352nd’s records reveal what actually happened. On a flight from Chabua to Kunming, a Mayday call was sent, “…stating that one engine was out and they were losing altitude. Crew parachuted 15 miles west of Yunglung, China, led into Tengchung on 27th, and evacuated on 28th March.” The aircraft’s crash location is listed as 25-14 N, 98-51 E, which is in the flood plain of the Salween (Nu Jiang) River.

The aircraft was piloted by 1 Lt. Stanley W. Zancho, 0-508455, who, “…was a retired captain from Pan American World Airways. He served in the Army Air Corps from 1942 to 1946. and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal and the Soldier’s Medal.” The co-pilot was 2 Lt. D.T. Spinkle (0-781440) and the radio operator Sgt. M.B. Rothchild (15097139). Probably because the crew was recovered after just over one week and their “Missing” status therefore resolved, the MACR is very perfunctory – at best – and doesn’t list the full names of the crewmen.

Sgt. Rothchild’s surname is uncertain. He’s listed in the MACR as “M. Rothchild Jr.”, but this name is crossed out and followed by the name “Rothschild”, while the records of the 1352nd AAFBU list his name as “M.B. Rothchild”. If the latter is correct, this man was very likely “Marvin B. Rothchild” (2/7/10-7/19/17) who’s buried at King David Memorial Park, in Bucks County, Pa. Like Morris Paster, his name is absent from American Jews in World War II.

(Data from AFHRA Microfilm Roll A0159, Frame 620)

The red circle on this map – the location of which was generated by inputting the coordinates of 43-47114’s loss (25-14 N, 98-51 E) into Oogle Maps’ latitude-longitude locator – reveals the location of the transport’s crash to have been northwest of Baoshan, on the bank of the Salween (Nu Jiang) River.

An air photo view of the same area. This terrain is not flat!

Let’s have a closer map view…

…and, a closer air photo view. Again, an abundance of mountains, hills, and ridges.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

While the aviators mentioned in this and related “March 19, 1945”-type blog posts served in bombers or transport aircraft, two other men, both fighter pilots, need be mentioned for the events of this long-forgotten Monday. They are Lieutenant Efim Aronovich Rukhovets of the Soviet Union’s Military Air Forces (VVS), and Flight Sergeant Saul David Lazarus of the Royal Air Force. Neither survived: Rukhovets was shot down, and Lazarus was lost during a practice mission.

U.S.S.R. (C.C.C.Р.)

Military Air Forces – VVS

(Военно-воздушные cилы России – ВВС)

Born in Minsk on February 22, 1921, Lieutenant (Лейтенант) Efim Aronovich Rukhovets (Ефим Аронович Руховец) was the husband of Vera Aleksandrovna, who resided in House (Building) 39 on Nakhichevanskaya Street, in Rostov-on-Don.

A member of the 848th Fighter Aviation Regiment of the 6th Air Army (848 Истребительного Авиационного Полка, 6-я Воздушная Армия) Rukhovets was shot down by anti-aircraft fire while while flying an La-5 fighter (…see also…) on his 46th mission, while attacking anti-aircraft positions during an escort of Il-2 Shturmoviks to a place called “Okhodosh”, which is probably near Lake Balaton. He’s buried only a few kilometers from where he (literally) fell to earth: In the Roman Catholic Cemetery at Patka, just northeast of Székesfehérvár, in Fejér County (specifically 2nd row, grave 2).

The following document – an english-language translation of Lt. Rukhovets’ posthumous award citation of the “Order of the Second World War” – covers his military service as a whole, including information about his aerial victory on March 17, and, his final mission of March 19.

Comrade Rukhovets especially distinguished himself in March 1945 during a period of our aviation’s intense combat work, which contributed to the defeat of the German tank group southwest of Budapest. He showed great skill in performing combat missions to escort attack and reconnaissance aircraft. Tactically competently maneuvering in the air always provided reliable cover for attack aircraft.

A difficult situation arose on March 17, 1945. Together with the leading pilot, Rukhovets covered an Il-2 group. This group was attacked by 5 ME-109s in an unequal air battle that ensued; when a threatening position was created for his leader, one ME-109 went onto the [leader’s] tail, Rukhovets quickly flew up to him from right behind and knocked him down from a pitch-up from a distance of 40 meters. The ME-109 rolled over, caught fire and crashed 2-3 km south of Mokha.

In total, during the Second World War, he made 46 successful sorties and shot down one ME-109.

On March 19, 1945, he died heroically while protecting attack aircraft from enemy anti-aircraft fire. In the Okhodosh area, an enemy anti-aircraft battery always interfered with the work of our aircraft. Rukhovets dived on it and suppressed it with dropped bombs. But his plane caught fire from anti-aircraft fire. Unable to save the craft and himself, he directed the burning plane onto the road and crashed into a column of enemy tanks moving along it.

FOR THE PERFORMANCE OF 46 SUCCESSFUL COMBAT FLIGHTS AND THE DESTRUCTION OF ONE ME-109 WORTHY OF A GOVERNMENT AWARD –

ORDER OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR – POSTHUMOUS

COMMANDER 848 IAP MAJOR / [STEPAN ILYICH] PRUSAKOV /

April 10, 1945.

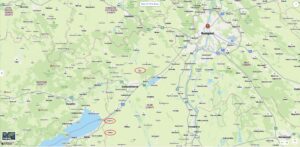

The following three maps show the assumed area of Lieutenant Rukhovets’ final mission, and, place of burial.

Though Okhodosh – wherever or whatever that is – cannot be identified either through Oogle or Duck-Duck-Go, the towns of Lepseny and Enying – the general vicinity where Lt. Rukhovets was shot down – are very much extant. They’re situated just inland from the northeast corner of Lake Balaton, near the contemporary M7 Motorway.

In the next map – zooming out and moving to the northeast – the northeastern part of Lake Balaton is still visible, while at the upper center we can see the approximate crash location of the Me-109 claimed by Lt. Rukhovets on March 17 (black circle), and the location of his place of burial (red circle): Just a few ironic miles northeast of Moha, at the Patka Catholic cemetery.

In the next map – zooming out and moving to the northeast – the northeastern part of Lake Balaton is still visible, while at the upper center we can see the approximate crash location of the Me-109 claimed by Lt. Rukhovets on March 17 (black circle), and the location of his place of burial (red circle): Just a few ironic miles northeast of Moha, at the Patka Catholic cemetery.

Zooming much further out, this map provides a view of Lepseny, Enying, Moha, and Patka (the latter two north of Székesfehérvár) in relation to Budapest.

Zooming much further out, this map provides a view of Lepseny, Enying, Moha, and Patka (the latter two north of Székesfehérvár) in relation to Budapest.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Another example of a Soviet WW II-era military award citation can be found at my brother blog (WordsEnvisioned), in a post pertaining to writer and novelist Vasiliy Semenovich Grossman – perhaps best known for his magisterial epic Life and Fate – within a post illustrating “The Years of War”. The latter book is a 1946 compilation of Grossman’s wartime reporting, published in English by the Soviet Union’s Foreign Languages Publishing House.

The post includes images of Grossman’s award citation for the Order of the Red Star, and, text of the citation in Russian, with English translation.

The blog also includes Grossman’s (ironically brief – in light of his posthumous fame) obituary from The New York Times of September 18, 1964 and three reviews of Life and Fate. These reviews are paralleled by three reviews of Grossman’s somewhat political, perhaps philosophical, tangentially mystical semi-stream-of-consciousness short novel, Forever Flowing, which – far more than in length alone – is vastly different in style and structure from Life and Fate.

As you’ll find mentioned in some of the reviews, and as discussed elsewhere, Grossman’s wartime prominence eventually availed him little, for after the war he grew increasingly disillusioned by the Soviet system. Central to his transformation – and the increasing importance of his identity as a Jew – were the suppression of the Black Book of Soviet Jewry, his reflections on the collectivization that led to the Holdomor (which is clearly addressed in several passages in Forever Flowing), and the political repression inherent to the Soviet system, which he personally experienced in the form of confiscation of the manuscript (and much, much more) of Life and Fate. In all, the primary and parallel themes to his his body of work – themes which were not exclusive of other aspects of life – proved to be the imperative of human freedom (even moreso when repressed), and, the centrality of his identity as a Jew.

Here are the posts:

Obituary

The New York Times, September 18, 1964

“Life and Fate” – Book Reviews

“Life and Fate”, The New York Times, November 22, 1985

“Life and Fate”, December 19, 1985

“Life and Fate” (1987 Harper & Row Edition, with cover by Christopher Zacharow), The New York Times, March 9, 1986

“Forever Flowing” – Book Reviews

”Forever Flowing”, The New York Times, March 26, 1972

“Forever Flowing”, The New York Times, April 1, 1972

“Forever Flowing”, February 23, 1973

Forever Flowing – Cover Art

“Forever Flowing”, by Vasily Grossman – 1970 (1986) [Christopher Zacharow]

(Okay… Yes, I know, I know! The topic is entirely unrelated to Jewish aviators in WW II, but in the far indirect context of that topic, I thought it worthy of mention. Sometimes, there’s virtue in inconsistency.

And now, this post shall conclude with a brief biography of one last Jewish aviator: Saul David Lazarus.)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

British Commonwealth

Royal Air Force

No. 322 (Dutch) Squadron

This version of No. 322 Squadron’s coat-of-arms is from Leeuwarden Air Base Squadrons (Squadrons Vliegbasis Leeuwarden).

As described at Remembering the Jews of WW 2, F/Sgt. (1437557) Saul David Lazarus (Shaul bar Rav Avraham Yakov), RAFVR, a member of No. 322 (Dutch) Squadron, was on a, “Bombing practice from airfield B.85 Schijndel in Netherlands. He flew to the target area but even though his plane was too close to the target he dived to the ground to drop his bomb. He released the bomb but because of the steep angle the bomb ended up between the aircraft propellers and exploded in mid-air killing Saul instantly.” This parallels information at All Spitfire Pilots, which in its entry for F/Sgt. Lazarus’ Spitfire LFXVI (serial RR205) states: “Form 540 – No operational flying but some practice bombing at the range, during which one of the Squadron’s new pilots, F/SGT LAZARUS, was killed in the Spitfire RR.205. The machine was seen to explode in the air the pilot being killed instantaneously. Even though F/SGT LAZARUS had only been with us a few days, he had made himself very popular with the pilots and groundcrew.” As described at Aviation Safety, the accident occurred at the Achterdijk-Kruisstraat Road, Rosmalen, Noord-Brabant, in the Netherlands.

As described at Remembering the Jews of WW 2, F/Sgt. (1437557) Saul David Lazarus (Shaul bar Rav Avraham Yakov), RAFVR, a member of No. 322 (Dutch) Squadron, was on a, “Bombing practice from airfield B.85 Schijndel in Netherlands. He flew to the target area but even though his plane was too close to the target he dived to the ground to drop his bomb. He released the bomb but because of the steep angle the bomb ended up between the aircraft propellers and exploded in mid-air killing Saul instantly.” This parallels information at All Spitfire Pilots, which in its entry for F/Sgt. Lazarus’ Spitfire LFXVI (serial RR205) states: “Form 540 – No operational flying but some practice bombing at the range, during which one of the Squadron’s new pilots, F/SGT LAZARUS, was killed in the Spitfire RR.205. The machine was seen to explode in the air the pilot being killed instantaneously. Even though F/SGT LAZARUS had only been with us a few days, he had made himself very popular with the pilots and groundcrew.” As described at Aviation Safety, the accident occurred at the Achterdijk-Kruisstraat Road, Rosmalen, Noord-Brabant, in the Netherlands.

This Oogle map shows Rosmalen, with Kruisstraat to the east-northeast. RR205 presumably crashed somewhere between.

F/Sgt. Lazarus was the son of Abraham (1886-2/8/48) and Fanny (Cosovski) Lazarus, and brother of Joseph and May, his family residing at 22 Tetlow Lane, Salford, 7, Lancashire. He is buried in plot 13,B,4 at Bergen-op-Zoom War Cemetery, Noord-Brabant, Netherlands. Born in Salford, Manchester, on June 8, 1921, his name appeared in The Jewish Chronicle on March 30 and June 22, 1945.

This image of F/Sgt. Lazarus’ matzeva is by FindAGrave contributor John Kirk …

… while this picture of a commemorative plaque in memory of F/Sgt. Lazarus, at the Lazarus family memorial (Failsworth Jewish Cemetery, Manchester) is by Bob the Greenacre Cat.

The inscription on the right states: A TOKEN OF LOVE FROM MOTHER JOE MAE BELLA AND CLAIRE.

Though there’s no specific photograph of Spitfire RR205, the aircraft would have born markings and camouflage identical to Spitfire XVI TD322 – squadron code “3W” – as depicted by in the illustration below, from Flightsim.to:

The aircraft, “…had the Dutch orange inverted triangle painted beneath its port windscreen quarter light. It also had nose art on the port engine cowling of the squadron mascot, Polly Grey, a red-tailed grey parrot, perched on a hand with the thumb raised.”

Specifically being an XVI Spitfire, RR205 was probably identical in design and outline to Czechoslovakian ace Otto Smik’s RR227, an early model “high-back” version of the Mark XVI Spitfire, which is shown below.

To conclude, from the Nederlands Instituut voor Militaire Historie, No. 322 Squadron Spitfires in 1945…

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

And so, we leave the skies of March 19, 1945.

References

Books

Dorr, Robert F., 7th Bombardment Group / Wing 1918-1995, Turner Publishing Company, Paducah, Ky., 1996

Dublin, Louis I., and Kohs, Samuel C., American Jews in World War II – The Story of 550,000 Fighters for Freedom, The Dial Press, New York, N.Y., 1947

Morris, Henry, Edited by Gerald Smith, We Will Remember Them – A Record of the Jews Who Died in the Armed Forces of the Crown 1939 – 1945 – Volume I, Brassey’s, London, England, 1989 (“WWRT I”)

Morris, Henry, Edited by Hilary Halter, We Will Remember Them – A Record of the Jews Who Died in the Armed Forces of the Crown 1939 – 1945 – Volume II – An Addendum, AJEX, London, England, 1994 (“WWRT II”)

Quinn, Chick Marrs, The Aluminum Trail – How & Where They Died – China-Burma-India World War II 1942-1945, Chick Marrs Quinn, 1989

Scutts, Jerry, Spitfire in Action, Squadron / Signal Publications, Carrollton, Tx., 1980

Magazines

Geiger, Geo John, Red Star Ascending – The Story of WW II Soviet Russia’s Premier and Last Piston-Engined Interceptor and Air Superiority Fighter, the Lavochkin LaGG!, Airpower, November, 1984, V 14, N 6, pp. 10-21, 50-54

No author, LaGG-3 – Lavochkin’s Timber Termagant, Air International, January, 1981, V 20, N 1, pp. 23-30, 41-43 (The La-5’s progenitor…)

No author, Last of the Wartime Lavochkins, Air International, November, 1976, V 11, N 5, pp. 241-247 (…the La-5’s successor.)