In its issue of November 3, 1916, an article describing the plight of Jewish civilians in Poland – during the advance, occupation by, and retreat of Russian military forces through that country – appeared The Jewish Exponent of Philadelphia. As indicated in the article’s introductory paragraph, this news item was itself derived from a series of reports previously published in The New York Times, with information obtained from “confidential reports”.

The Exponent presented the information in this article under seven major headings. Namely:

1) The Attitude of the Russian General Staff towards Jewish soldiers (400,000 then serving in Russian army)

2) The Situation of the Jewish populace in Poland

3) The Experience of the Jews of Galicia

4) Taking of hostages and expulsion of Jews

5) Treatment of Jews during the retreat of the Russian army

6) Implications and impact of “Kush Incident” on the treatment of Jews by the Russian army, as reported on and instigated by the Russian military periodical Nash Vestnick

7) The Plight of Jewish refugees

The “take-aways” (in the jargon of 2019) from a reading of this article are simple, and, striking:

The seeming irrelevance – at least as perceived at the level of the Russian General Staff – of the dedication and loyalty Jewish soldiers in the Tsar’s army, and the General Staff’s corresponding near-automatic assumption of treachery on the part of all Jews – both soldiers and civilians;

…the generally hostile attitude of non-Jewish Poles towards Polish Jews (albeit not universally and consistently so), which was communicated to and influenced the attitude of Russian military leadership towards Polish Jewry;

…and, the difficulty (if not the practical impossibility) of self-defense – any projection of power, for that matter – by Polish Jews, whether individually or collectively.

Read more, below…

______________________________

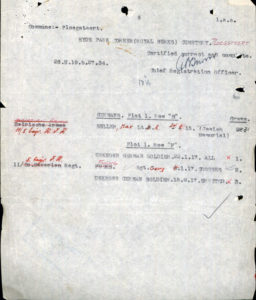

How Russian Jews Suffered In War

Confidential Reports tell of Their Persecution by Military and Civilians

(From the New York Bureau of The Jewish Exponent)

November 3, 1916

THE STORY of what the Jews suffered in Russia during the war, although barred by the censor from the columns of the Russian press, has come to The New York Times in a series of confidential reports, each one bearing open some aspect of the situation.

Soon after war was declared the Jewish people by word and deed offered every assurance of loyalty to Russia and her cause. They responded to the mobilization summons as eagerly as any other element of the population. Great numbers of students, barred from the Russian university because they were Jews, abandoned their courses in foreign institutions and returned to Russia to serve as volunteers.

An examination into the circumstantial sources from which the charges of Jewish treachery and espionage actually sprang about, showed according to a report of the Central Committee, that most of the accusations were made and prosecuted without reference to the ordinary rules of evidence and n utter disregard of the laws governing judicial procedure in such cases. The written records from which it could be ascertained whether or not these charges were supported by legal evidence sworn to by witnesses are conspicuously absent.

On the other hand, the Central Committee found that the military authorities often pursued the most rigorous course on mere hearsay and rumors which they did not ignore even in the absence of sufficient proof for fear that some possible act of espionage or treason might escape unpunished.

The written records of eight typical cases of Jews charged with treason in the early days of the war show that six of these proceedings fell through for want of proof. One defendant, a miller, was accused of guiding German artillery fire with the arms of his windmill. On the day of a certain bombardment the wing kept turning the wheel in the direction of the Russian position under fire from which it was surmised that the miller was transmitting signals to the German gunners. He was acquitted.

Another defendant was accused of possessing a secret telephone in his moving-picture establishment by which he could send information from the Russian lines to the German trenches. The telephone case, which was heard in the town of Lomsch, not only terminated in the vindication of the defendant, but his accuser, a military inspector, was himself convicted of bribery and extortion. It was proved that he deliberately manufactured false evidence in order to have the defendant arrested and obtain money and jewelry from his relatives by pretending to save him from the rope.

Most of the charges alleged nothing more treacherous than conversations in which the defendants either gave information to German soldiers or withheld information from the Russians.

Jewish Soldiers Suspected

Despite the triviality and collapse of these charges, the story of Jewish treachery continued to gain ground until it even took root in the ranks of the army, bringing the Jewish soldiers themselves, of whom there were about 400,000 in the Russian lines, under suspicion.

The General Staff issued a circular in April, 1915, demanding the careful collection of all available facts pointing to treachery and disloyalty on the part of Jewish soldiers. The same kind of order was issued with reference to Jews who were doing service in the medical, sanitary, and commissary branches of the army.

“This evidence,” a proclamation asserts, “is indispensable in view of the fact that after the war it will be necessary to pass serious judgment upon the question of Jewish service in the ranks of our army; therefore, it is extremely desirable to have at hand the testimony, systematically collected by members of the various military branches who had to tolerate the menacing presence of the Jew in their very midst.”

Aside from inflicting a stigma upon the Semitic soldiers, the General Staff took official cognizance of the alleged acts of Jewish infamy. Numerous proclamations were issued against the crimes of the Jewish populations in the theatre of war. They were accused among other things of refusing to feed the Russian soldiers and of putting poison in the food when they did feed them. They were accused of betraying the movements of Russian troops, by overhead or underground wires, many of which were supposed to emanate direct from the synagogues and Jewish cemeteries. They were accused of transporting secret supplies to the German troops. They were accused of harboring soldiers in their cellars and yards and allowing the Russian to march into traps of destruction. Thus in November the following proclamation was issued from the division headquarters in the region of the fortress of Novoe Georgievsk:

Articles appear in German newspapers to the effect that the German troops have found in the Jew a trustworthy ally who, having access to unknown supplies of food, is often diffident enough to serve the Germans in every way that might do damage to Russian interests. In German victory the Jews saw their escape from the imperial yoke and from Polish oppression.

Information of a similar nature has also been received from the army at the front.

To protect the army against the perfidious activities of the Jewish population, the Commander in Chief hereby orders that in all occupied points hostages be taken from the Jewish inhabitants with a warning that any act of treachery by the Jews while the town was in our hands, or even after its evacuation, would mean the forfeit of the lives of those taken as hostages; that the disclosure in these places of any wireless apparatus or signaling stations or underground telegraph communications, etc., would expose those responsible to the full rigor of the law.

The Situation in Poland

During the occupation of Poland by Russian troops in the opening year of the war the Jews there inspired imperial distrust for several reasons. In the first place, the anti-Semitic Poles, to whom Jewish competition in business was always distasteful, did everything in their power to fan the flames of suspicion and hatred. Secondly, the condition of Jewish life in Poland, very different from that of the Gentiles, or even the Jews of the Russian provinces, also contributed to general uneasiness in the ranks of the army. To quote the report of the Central Committee on this point:

“For the most part, the Jewish population of Poland has not yet emerged from its past, but clings securely to its pristine self-conscious kind of existence. They retain the medieval costumes of the race, which give the men who wear beards and queer, dark clothes an especial alien and ominous aspect. They speak a language that is neither Polish nor Russian, but a jargon, Yiddish, founded a hundred years ago and developed by admixture of Slavic and Hebrew words.

“All these conditions naturally added to the feeling of estrangement between the Jewish inhabitants and Russian soldiers who invaded their territory and who for the first time looked upon people of such peculiar appearance. Naturally, they became suspicious of a people who, though Russian subjects, spoke a language sounding like German, a language understood easily enough by the enemy, but not by the Russians.

“The excuse of suspicion on the one side evoked an attitude of fear and timidity on the other.

“The anti-Semitic element naturally encouraged the hostile attitude of the army, believing that it would result, if not in the extermination of the Jews, at least in their ruin or a radical abridgement of their rights after the restoration of the Imperial Government in Poland.”

The story concerning secret telephone communications with the Germans received the widest audience in military circles and more than once innocent Jews had to pay with their lives for this particular accusation.

Another story which did much damage was to the effect that the Jews were responsible for the scarcity of money throughout the empire, that the Jews were concealing great stores of coinage in their cemeteries, cellars and other secret places. They were even alleged to have carried great sums of money across the border in coffins.

The Situation in Galicia

The experience of the Russian Army in its invasion of Galicia proved to be another source of anti-Semitic resentment. The Galician Jew differed but slightly in appearance and customs from the Polish Jews. He spoke the same incomprehensible language, only understood by the Germans. There was really nothing to distinguish the two excepting that the Galician Jews were more ferociously hostile to the Russian Army than the Jews under Muscovite rule. True enough, the Galician Jews offered the Russians no cordial reception. For them the ravaging Cossack typified the whole Russian Army.

So it happened that whatever difficulties the Galician Jews created for the Russian Army in its Carpathian campaign reacted directly against the Jews of Poland and Russia.

The tendency to put all Jews, whether Russian or Austrian subjects, in the same unfriendly class first manifested itself officially in a proclamation issued by the General Staff on the southwest front. Subsequently, the same order issued on January, 1915, was sent to all points of the front. It read as follows:

The events of the present war have revealed a decidedly unfriendly attitude toward us on the part of the Jewish inhabitants of Poland, Galicia, and Bukowina. Whenever our forces stopped, the friendly inhabitants open the subsequent occupation of those regions by the Germans have had to endure great hardships because of the lying reports made by the Jews to Austrian and German authorities.

Wherefore, to relieve the inhabitants of Jewish prosecutions and to protect our armies against the espionage in which the Jews are engaged on all our fronts, the Commander in Chief has forbidden the presence of the Jews in the vicinity of our armies and their migration to any point south of the city of Yaroslav; furthermore, in view of the slanders perpetrated by the Jews against the population, and in view of the espionage practiced by the Jews, the Commander in Chief has ordered that hostages be taken who shall be liable to the punishment of death by hanging. For every peaceful inhabitant made a victim of by Jewish slander, and for every instance of Jewish espionage, the lives of two hostages shall be forfeited.

This step is taken top protect the peaceful and friendly inhabitants from suffering as the result of Jewish lies; it is taken on the basis of six months experience which has brought our military authorities to the firm conviction that the Jews have and will continue to display a disloyal and relentless attitude toward the local population.

Taking of Hostages

The taking of hostages was a circumstance which caused the deepest resentment throughout the whole Jewish population of Russia. Hostages were taken beginning with the second month of the war in Prushkov province of Warsaw. Thereafter, the military authorities adopted this policy as a guarantee against Jewish treachery throughout the provinces of Poland, Courland and Kovno. As a rule, the hostages were rabbis and wealthy Jews – the most influential members of the community. They were men not only valuable to their own people, but men who had also proved themselves exceptionally energetic in the humanitarian endeavor of providing and caring for wounded Russian soldiers and their families, irrespective of religious faith.

The report of the Central Committee records the execution of three men held as hostages in Sohachev in December, 1914. The reason for their execution could not be ascertained.

The decree quoted above was only one of a series of similar proclamations which culminated in the anti-Semitic propaganda of 1914 and in the spring of 1915. Shortly after the war began, orders were issued directing the Jews of certain towns on the Polish-German frontier to retire into the interior, taking with them as much of their belongings as they could carry. Beginning with perfunctory proclamations that were to all appearances prompted by military necessity, the policy of the authorities within a few months assumed a relentless course of discrimination against the Jews.

By the end of December, 1914, under the lash of military proclamations, the exodus of Jews had developed into a great upheaval of the whole Semitic population of Poland. On January 25, 1915, a general order was issued expelling the Jews from more than forty towns in the region of Warsaw. More than 100,000 Jews had to abandon their homes under this decree. They were driven from one town to another in rapid succession, and they had no time in most cases to collect the necessities of life, such as food, clothing and utensils. Old men, women and children – all the able-bodied Jews being at the front fighting for Russia – made up this dreary and endless caravan of misery, which the military authorities got into motion.

Once the order to leave was issued, the Jews were expected to comply without a moment’s delay. All considerations of home, family and property had to de abandoned. The rabbis, on behalf of their community, often appealed to the military commander for an extension of the allotted time. Sometimes the appeal was granted; more often it was refused. The police, moreover, being themselves held strictly responsible for the prompt execution of military orders, were right on the heels of the Jews with whips and threats.

The report of the expulsion of the Jews from Smorgon, province of Vilna, in September, 1913, [sic] cites an occurrence where a Cossack officer, on finding that two sons and an aged father had not vacated their homes with the rest of the Jews, demanded to know the reason why. The sons declared that they did not know what to do because their old father was lying very ill in bed and could not possibly be moved without endangering his life. The officer asked to see the old man. On being brought to his bedside the officer drew a revolver, put a bullet through the sick man’s brain and remarked to his sons, “Now you are free to go.”

On many occasions Jewish inhabitants fleeing from their native towns saw the sky illuminated that night with the flames of their burning homes. They had no redress unless the commanding officer happened to be especially humane. Thus, in Ynova [sic]. the military commander, Gabrilowitsch [sic], in checking the instigation of a pogrom against the Jews, reminded the Cossacks and peasants that he knew “neither Jew nor Gentile, only Russian subjects”. Very often, too, especially during a period of Russian advance, soldiers who engaged in pillage, even of the Jews, were punished with the full rigor of the law.

Crimes Following the Retreat

When the Russians were thrown back into Poland, the protection of the Jewish inhabitants along the line of retreat became so extremely lax that they were at the mercy of Cossacks and peasants. The cry was, “All Jews are traitors.” The following is reported to have taken place in the town of Lokachi, province of Volinski:

“On July 24 the Cossacks and Dragoons, in order to distinguish between the Gentiles and Jews of the village, ordered the former to display ikons in their windows. This being done, they hastened to destroy and plunder Jewish property. The pogrom began in the shop of a Jew when a Cossack demanded a pound of tobacco, costing not less than four roubles. The Jew replied that he did not keep such high-priced tobacco in stock, whereupon the Cossack pierced him with his lance and killed him. Following this occurrence the whole Jewish population fled and encamped in the open about two miles from the village. For the three following days the destruction of property continued without cessation. When their was nothing else to destroy the Cossacks rode out to the spot where the Jews had encamped under the open sky. They lined up the Jews and robbed them of all their money and valuables. One of the Jews, Gershon Pfeffer, resisted their violence. They dragged him into the woods and he never returned. On August 11 a gendarme found his coat there all covered with blood.”

A Cossack, in a letter to his brother concerning conditions in a town he had helped to sack, wrote as follows:

“The people here are very poor, not sure of getting anything, and you spend very quickly whatever you get. With 70 cents a months you can’t go very far, when you have to put up for the horses’ feed, too. Bread you get wherever you can. Kill a Jew and he has not got anything, and we club them like dogs, only there is nothing to be had; they are starving of hunger themselves.”

The Kush Episode

The wholesale and systematic expulsion of the Jews did not begin until May, 1915, when it was practically coincidental with the publication of what is termed the most vicious canard of the war. On May 5, the official military organ, Nash Vestnick, published a dispatch which read as follows:

“On the night of April 28, in the village of Kush, southwest of Shavie, the Germans made a successful attack upon a detachment of our infantry which was resting in that vicinity. The occurrence revealed sedition and treachery of the part of certain elements of the population, especially the Jews. Before the appearance of our troops in this village, the Jews had concealed German soldiers in many of their cellars. At a given shot, the Germans poured in on us from every direction. Rushing out of the cellars they attacked the house occupied by the commander of our infantry regiment. This disastrous event demonstrates the military necessity of taking the most diligent precautions in places which the Germans had formerly occupied and of which the inhabitants are largely Jews.”

Distributed by the Petrograd Agency to all the important newspapers, this dispatch created a tremendous wave of anti-Semitic feeling even among the more intelligent people. The Kush dispatch, furthermore, was placarded in and posted in nearly all the large cities and in all towns near the war zone.

An investigation of the German raid on Kush by two members of the Duma, Kerensky and Friedman, established beyond a doubt, according to a report of the Central Committee, that the Kush dispatch was a lie from beginning to end. The facts as developed by this inquiry showed that out of forty houses there were only two occupied by Jews which had cellars. These cellars, moreover, were merely very small basements, which could not have possibly accommodated any German soldiers. On April 26, in the evening, a detachment of Russian infantry moved into the town. Owing to the presence in the village on that very morning of a German scouting party, the Russians were warned by one of the inhabitants that the Germans were not more than four versts away, but they merely laughed at the suggestion and paid no attention to it. On the same night a bombardment set the village on fire. On the 27th the commanding officer advised all the inhabitants to leave the town, so that when the German attack took place on the 28th there was not a single Jew in the village.

Plight of the Refugees

This Kush dispatch had a very pointed effect upon the Gentile population of Russia when the exodus of the Jews reached its climax in the wholesale expulsion of about 200,000 Jews from the provinces of Kovno and Courland. They met with hatred and contempt all along the route of their flight.

Furthermore, although the problem of transporting so large a mass of people across the country was a very serious one, neither the railroad nor military officials gave it much consideration. The refugees were packed into freight and cattle trains and kept there for many days at a time with disease and filth and epidemic in their midst. In the beginning, the railroad officials, taking advantage of their misfortune, tried to charge third-class rates for accommodations in box cars. This abuse, however, was quickly checked by the Provincial Government.

Part of the refugees were transferred without delay to the districts of the provinces of Poltava Ekaterinoslav designated as a new pale of settlement by the authorities; others fled to other villages and towns of adjoining provinces, hiding in synagogues, barns, or under the open sky. Some had passports and documents, which would entitle them to retain residential rights; others had nothing, and they were continually hounded from place to place. Freight cars packed with Jews poured into the provinces of Poltava, Ekaterinoslav, and Tavrich and soon evoked from these districts a clamor of protest.

“In Homel,” reads the report of the Central Committee, “the members of the Jewish committee organized to give aid to the refugees as they passed through the town were ordered not to approach the cars with provisions under the threat of being shot. They were strictly prohibited from giving any food to the refugees. In connection with the circumstance, the Gentile population of the town was also very hostile to the refugees. There were times when stones were thrown at the Jews and several were killed, and there were also times when the Gentiles, seeing that the ‘criminals’ were merely old, trembling men and women and children, immediately changed their entire attitude.

“It may be noted with satisfaction,” reads the committee’s report, “that in those provinces where the influence of the Black Hundred was not allowed to dominate the Gentile inhabitants showed no enmity toward the Jews, but, on the contrary, displayed on many occasions the warmest sympathy.”

The expulsion of the Jews took place on the eve for the call for recruits of the class of 1916. Hence, thousands of young Jews who had been driven out as “spies” were ordered to return to their native provinces at once to fulfill their military obligations.

The expulsion of the Jews was followed by economic demoralization of business in all the provinces from which they were driven. Although the nationalistic paper of Kovno, Litovskaya Russ, urged the Gentiles to take advantage of their economic opportunities after the Jews were gone, business remained at an absolute standstill. The shops in all the main streets of Kovno remained shut. There was hardly a grocer, butcher, or delicatessen store to be found. Jewish industries and factories were shut down and thousands of men were thrown out of employment.

Towards the end of May the Government and military authorities realized that the expulsion of Jews had been a great mistake. But in order to retain the political effect of this movement and continue the distinction between the Jews and the rest of the population, the authorities agreed to have them return provided that they gave hostages as a guarantee that there would be no treachery. Feeling it impossible to accept a condition which was based on a presumption that they were capable of treachery, most of the Jewish communities rejected the invitation and the situation remained unchanged. – New York Times

Readings and References

Lohr, Eric, The Russian Army and the Jews: Mass Deportations, Hostages, and Violence During World War I, Russian Review, V 60, N 3, July, 2001, pp. 404-419

Petrovsky-Shtern, Yohanan, The “Jewish Policy” of the Late Imperial War Ministry: The Impact of the Russian Right, Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History, V 3, N 2, Spring, 2002, pp. 217-254

Vital, David, A People Apart – A Political History of the Jews in Europe, 1789-1939, Oxford University Press, N.Y., 2001