Within my ongoing series of posts about the military service of Jews in the Second World War, a frequent thread – specifically for events in 1945 – has been reference to the six reference works created by the late Benjamin Meirtchak, covering Jews in the armed forces of Poland. Published in Tel-Aviv between 1995 and 2003, Meirtchak’s books encompass virtually every facet of Jewish military service – and Jewish casualties – in Poland’s armed forces, ranging from men who were officers, members of the Polish Resistance, service in the Polish armed forces in exile, POWs captured in the German campaign of late 1939, and, the over 400 Jewish officers murdered during the Katyn Massacre in April and May of 1940.

While Mr. Meirtchak’s works are as invaluable as they are unique, perhaps inevitably – due to the sheer number of names involved – the information within them is typically limited to a man’s name, rank, military unit (that is, for men who served in infantry and armor) year and place of birth, father’s name, and for those men killed in action or who were murdered as POWs – date of death, and if known, place of burial.

However, there are some men in Meirtchak’s books whose stories – by absence of substantive information – are enigmatic.

One such man is mentioned in my post covering Jewish military casualties on March 15, 1945: Warrant Officer Aleksander Broch (“Soldiers from New York: Jewish Soldiers in The New York Times, in World War Two: Hospital Apprentice 1st Class Stuart E. Adler – March 15, 1945“.), which is limited to the following information:

Polish People’s Army [Ludowe Wojsko Polskie]

Broch, Aleksander, WO, in Poland, at Zachodniopomorskie, Kolobrzeg

Born Sosnowiec, Poland, 1923

Mr. Stanislaw Broch (father)

Kolobrzeg Military Cemetery, Kolobrzeg, Poland

Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II: Vol I, p 73

This is how the record for WO Broch appears in Volume II of Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II, in a format and content consistent with other biographical entries…

…while here’s the book’s cover, the plain appearance of which is identical to that of Volumes I, III, and IV.

I’d long assumed that Broch’s story would remain unknown, but fortunately, that supposition has been proven to be incorrect. The answer to the puzzle was discovered in a very unanticipated source: The database of Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Remembrance Center of the nation of Israel.

Though the central focus of Yad Vashem is upon the fate of the civilian Jews of Europe and North Africa during the Shoah, the Center’s archives, which are a historical repository as much as a museum (and far more than a simple museum, at that) comprise a tremendous variety of artifacts, documents, and photographs, that – hailing from the late 30s through the mid-40s – encompass a wide variety of facets of Jewish life, as a civilization, during that time period

In this sense, Yad Vashem possesses a trove of material relating to the military service of Jews in the Allied armed forces during the Second World War, which is accessible – akin to records directly pertaining to the Shoah – by entering search terms in the dark blue banner atop the Center’s home page. Though the website’s search engine isn’t designed to allow the “Advanced Searches” typical of other digitized archives and repositories, the search records, once returned, can be displayed by order of Relevancy, person’s Name, Photos, the names of Righteous (Among the Nations), Testimonies, Movies and Books, and, Artifacts. Simultaneously, search results can be filtered by Subject, Source, Rescue Mode, Religion, Profession, Collection, and Language, these seven fields being displayed within the web page’s left sidebar. Examples are show below…

✡ ✡

Here’s Yad Vashem’s home page. The search field occupies the horizontal dark blue banner at the top of the page. Clicking on the small magnifying glass symbol at the right end of the banner transforms it into a search box with text stating “Type and press enter…”

…and here are the 120,652 results generated (in November of 2023) by typing “Jewish Soldiers”. As can be seen under “Refine and Filter” in the left sidebar, and, record types listed horizontally, results are filtered after searching.

Here are the total “hits” returned for a variety of searches pertaining to Jews in the military in WW II:

“Jewish Partisans” > 10,600

“Jewish Prisoners of War” > 92,500

“Jewish POWs” > 4,400

“Jewish Brigade” > 3,780

“Jewish Women Soldiers” > 1,695

“Monte Cassino” > 137

“American Jewish Soldiers” > 750

“British Jewish Soldiers” > 2,080

“French Jewish Soldiers” > 880

“Greek Jewish Soldiers” > 145

“Polish Jewish Soldiers” > 13,100

“Russian Jewish Soldiers” > 3,700

An impressive and moving example of the nature of Yad Vashem’s holdings, and, the website’s design and ease directly relate to my June, 2021 post “The Jewish Brigade at War – The Palestine Post, April 13, 1945”, which includes biographical information about Private Asher (Uszer) Goldring [גולדרינג אשר] (PAL/16323). Presumably captured by the Germans after a night-time battle in the Senin Valley of Italy on March 31, 1945, he was never seen again. Seventy-eight years later, he is the only fallen member of the Jewish Brigade whose body has never been found.

Yad Vashem possesses an enormous trove of documents about Asher, as described in this catalog entry: “Letters related to Asher Goldring, born in Konstantinov, Poland in 1910, and other documentation related to him, his wife Hana (Schmuckler) Goldring, born in Strlishche, Poland in 1910, and their family members, dated 1938-1948”. The full entry states: “Letters sent to Hana Goldring, regarding the fate of her husband Asher, who made aliya to Eretz Israel as a pioneer and enlisted in the Jewish Brigade. Included in the letters is notification by the British Ministry of War, dated 13/01/1948, that the soldier Asher Goldring was killed in action; letters sent to Asher and Hana Goldring in the British Mandate for Palestine by their families in Poland in 1938; letters sent by Asher Goldring to his wife Hana while in service as a soldier in the Jewish Brigade, written during 13/01-31/03/1945; poems; a newspaper; drawings by Asher Goldring”.

Comprised of over 200 items (!), a perusal of these documents reveals the magnitude of the Center’s efforts in processing documents for public access: The quality of the scans is really excellent. (I’d like to translate them, as they embody a story that merits telling. But, they’re all in Hebrew. Oh … well.)

A few other examples of Yad Vashem’s records about the military service of Jews in World War Two include documents pertaining to…

Juda Waterman (B-25 Mitchell pilot in No. 320 (Netherlands) Squadron, RAF)

Naum Naumovich Rabinovich (Yak fighter pilot and ace in 513th Fighter Aviation Regiment (see also), 331st Fighter Aviation Division, 2nd Air Army, Soviet Air Force), a “Refusenik” in the 1980s. Possible future post. (Who knows?)

Semion Yakovlevich Krivosheev (Il-2 Shturmovik aerial gunner in 810th Attack Aviation Regiment, 225th Attack Aviation Division, 15th Air Army, Soviet Air Force, who, having been shot down and captured on July 18, 1944, was one of the extraordinarily few Russian Jewish aviators to have survived the war as a POW of the Germans.) Possible future post. (Who knows?)

“Testimony of Miroslav Sigut… (Born in Dobratice, Czechoslovakia, 1917, regarding his experiences in Krakow, as a French Foreign Legion soldier in France and as a Czechoslovakian Army soldier in England.” Includes comments about Squadron Leader Otto Smik of No. 312 and (later) 127 Squadrons, RAF.)

Those just scratch the surface, of the surface. (Of, the surface.)

✡ ✡

And so, what of Aleksander Broch?

On a whim, I searched for information about “Jewish Pilots”, and was more than startled to find the following: “Confirmation of the service of Aleksander Broch as a pilot in the Polish Army and his having been declared missing during a campaign conducted 15 March 1945; excerpt from the “Polska Zbrojna” newspaper regarding the memoirs of Polish pilots, dated 18 March 1947”.

Another document about Broch is the “Page of Testimony” that was filed in his memory by his father Stanislaus (Shmuel Barukh), on July 8, 1955, while the latter was residing in Israel. The aforementioned web page for this document incorrectly lists Aleksander’s date of death as “13/3/1945” and status as “murdered”.

And then… I remembered my post pertaining to the events of March 15, 1945.

And then… I duck-duck-goed “Aleksander Broch”, and was once again startled: A biography of the pilot by Wojciech Zmyślony appears at Polish Air Force.pl, along with Broch’s portrait. Zmyślony’s account being invaluable and unavailable elsewhere, I thought it merited presentation “here”, to make the story relevant to a wider audience.

To that end, a the translation of follows below. This is followed by two documents about Broch at from Yad Vashem, which are alluded to in Mr. Zmyślony’s list of references.

One document is the article “Wings over Kołobrzeg – Memories of the fights of Polish pilots”, published in Polska Zbrojna (Armed Poland) on March 18, 1947, while the other is a letter by chaplain M. Rodzai to W/O Broch’s father Stanislaw. For the purposes of this post, the English-language translation of each document appears first, and then, a transcript of the document in the original. (Well, as best as I could transcribe them!)

Accompanying the Polska Zbrojna article are four maps showing locations of places mentioned in Mr. Zmyślony’s story, and, the Polska Zbrojna article itself.

✡ ✡

So to start, here’s Wojciech Zmyślony’s biography of Aleksander Broch, which includes a portrait of Broch – below – provided by fellow pilot Kazimierz Rutenberg; a fellow pilot in the 1st Fighter Aviation Regiment “Warszawa”; see The Direction Was Clear (Kierunek był Jasny), by Kazimierz Rutenberg. Wojciech’s article in the original Polish can be viewed here, at Polish Air Force.

The biography…

– .ת.נ.צ.ב.ה. –

…Tehé Nafshó Tzrurá Bitzrór Haḥayím

May his soul be bound up in the bond of everlasting life.

Aleksander Broch was born on February 9, 1923 in Przemyśl. His parents were Jews from Warsaw: his father, Samuel Broch, earned his living as a merchant, and his mother, Perla Lea née Pillersdorf, took care of the house. Later, Samuel changed his name to Stanisław, and returned to its original Hebrew form – Szmuel – after emigrating to Israel after the war. The mother later also Hebrewized her name to Pnina. Aleksander, still as a child (at the age of 10 or earlier), moved with his family to Sosnowiec. There he attended a primary school, and then the Jewish Co-educational Gymnasium of doctor Henryk Liberman. The Brochs – parents, Aleksander and his younger sister – lived in a tenement house at the market square in Sosnowiec. The friendship between two later aviators of the 1st Fighter Aviation Regiment “Warszawa”, raised in Sosnowiec, dates from this period: Broch and Kazimierz Rutenberg, a year younger than him.

When in September 1939 the Third Reich invaded Poland, the Brochs fled east. After the September Campaign, they had no reason to return to Sosnowiec, incorporated by Hitler’s decree into the Third Reich. Choosing between two evils, they stayed in Lviv, occupied by the Soviet Union, where at least they did not have to fear Nazi persecution on the basis of their nationality. It is not known what Aleksander Broch did in Lwów; he probably attended school. Less than two years later, he was once again forced to flee from the Germans, when on June 22, 1941, Germany attacked the USSR. Persuaded by his father, he decided to go deep into Russia. When Lviv was occupied by Wehrmacht troops on June 30, the 18-year-old boy was already somewhere else. He was not imprisoned or repressed and presumably worked in kolkhozes. For unknown reasons, he failed to join the Polish Army, formed from July 1941 under the orders of General Władysław Anders (perhaps he was rejected as a Jew). This army finally left the Soviet Union in September 1942, also taking tens of thousands of civilians with it.

After the Polish troops were moved to Persia (i.e. today’s Iran), repressions were intensified against the Polish citizens remaining in the USSR, imposing, among other things, Soviet citizenship and making it impossible to leave Soviet territories. So Broch decided to get to the Polish Armed Forces in the West on his own. He hoped to reach British-controlled India by way of Afghanistan. He failed to implement this idea. He crossed the border of Afghanistan, but was injured by wild animals there and turned back west to the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic.

A few months after the departure of General Anders’ troops to Persia, the formation of the Polish Army began once again. Commanded by General Zygmunt Berling, who was loyal to the Soviets, it was soon to go to the front in accordance with Stalin’s plans. In response to the recruitment to the army, Broch volunteered in the first months of 1943 at the recruitment commission in the city of Jolotan, in the Marian district, on the edge of the Karakum desert. Like all recruits, he was sent to Sielce nad Oką, about 30 km north-west of Ryazan, where the 1st Infantry Division of Tadeusz Kosciuszko. To reach his destination, Broch had to cover a distance of nearly 4,000 kilometers. During the journey he made with a couple of companions, he got rid of the rest of his possessions, replacing, among others, clothes for salt, which he managed to sell at a large profit elsewhere, where it was considered a luxury item. This provided him with the funds needed to reach his destination.

In Sielce, Broch initially joined the infantry. There, he unexpectedly met a friend from his youth, Kazimierz Rutenberg. Their paths parted again, but this time for a short time: Rutenberg was assigned to the anti-tank artillery, and Broch (who could ride a motorcycle) was assigned to the communications service in the 1st Tank Regiment. When the air force recruitment was announced in Sielce, both Broch and Rutenberg applied. After a successful medical examinations, at the beginning of August 1943 they were transferred to the nearby Grigoriewskoje, where the Air Squadron of the 1st Infantry Division named after Tadeusz Kosciuszko. On August 20, the Polish squadron was expanded to a full-time regiment, and on October 6, 1943, it officially adopted the name: 1st Fighter Aviation Regiment “Warszawa”.

In Grigorievskoye, students began pilot training in difficult conditions. The pace was very fast – training (including theory) in the field of basic pilotage and fighter specialization was planned for only ten months. Theoretical lectures were conducted in Russian, and the list of subjects included: air navigation, airframe construction, engine construction, theory of flight, aerial shooting, aviation tactics, radio communication and parachute training. After theory, it was time for practice. Basic pilotage was trained on light UT-2 training aircraft. The next step was training on twin-steered Yak-7Vs (similar in construction to the target fighter on which the pilots of “Warszawa” were to fly), and finally launching and training in air combat, shooting and aerobatics on the Yak-1b.

On May 28, 1944, Broch was promoted to ensign, which was the first officer rank in the Polish People’s Army. In August 1944, the regiment was moved to the Gostomel airport near Kiev (now the airport of the capital of Ukraine), and at the beginning of June 1944 to the village of Dys near Lublin. It was the regiment’s first airport in Poland. In Dysa, several more experienced pilots joined the unit, and on August 18, 1944, the planes flew to Zadybie Stary, from which combat flights finally began. When the regiment left for the front, Broch was assigned to the position of the pilot of the 2nd squadron.

On August 23, 1944, the pilots of the 1st Regiment were baptized by fire. Broch had to wait nearly a month for his first combat assignment. On September 19, his plane took off from Zadybie Stary together with five other Yaks to cover eight Il-2s from the 611th Air Assault Regiment, attacking targets in the area of the south-eastern outskirts of Warsaw. The next flight, exactly 10 days later, consisted in the escort of a single Il-2 reconnaissance over the left-bank Warsaw by a pair of Yaks. On this assignment, Broch used his on-board weapons the enemy for the first time, firing at ground targets. It was one of the few tasks that the pilots of the 1st Regiment could perform over the insurgent capital… Unfortunately, it was already dying at the time, as providing effective help to the insurgents was definitely prevented by Stalin’s cynical decisions.

Broch performed another task on October 15, escorting with three other Yaks a group of six Il-2s attacking targets in the area of Nowodwory, Winnica and Jabłonna. During this flight, Focke-Wulf 190s were spotted flying in the distance, but no combat took place. A similar flight – an escort of a pair of Il-2s for reconnaissance of the Poniatów-Suchocin-Jabłonna-Legionowo area – Broch made on October 27, firing again on the ground targets he encountered. On November 8, he flew for reconnaissance north of Warsaw, in the area of Jabłonna, Modlin and Olszewnica. Two Messerschmitt 109s were encountered in the air, but there was no combat as the fighters moved away. Broch, however, dived and strafed the ground targets he spotted. On 20, 22 and 25 November, he flew for visual reconnaissance, respectively: Jabłonna-Nowy Dwór-Leszna-Grądowa, Jabłonna-Nasielska-Kroczewa-Leszna-Warszawy-Błonia and Mokotów-Grodziska-Błonia-Piaseczno. During the second of these flights, he attacked air defense positions, and during the third – German motor vehicles. It was Broch’s last combat task in 1944. The longer break was related to the stopping of the front near Warsaw on the Vistula River.

Broch completed the next three tasks only in 1945, on January 19-20, after the capture of Warsaw. The first was to cover the parade of the 1st Polish Army, which marched along the ruined Aleje Jerozolimskie. Broch flew in a formation of six planes, led by the regiment commander, Lt. Col. Ivan Taldykin. On the same day, he flew to the air cover of his own troops in the area of Warsaw-Błonie and crossing the Vistula north of Warsaw. The next day he conducted another patrol over the capital itself.

After this series of tasks, the regiment again had a break in combat tasks. At that time, it was moved to the Sanniki airport near Gostynin, and then to Bydgoszcz, from where flights were started to support the 1st Army of the Polish Army fighting to break the Pomeranian Wall. On February 20, Broch was covering a pair of Il-2s flying towards Złocieniec. At the local railway station, four trains without steam locomotives were spotted. Broch dived and strafed both the trains and the station. Five days later, he flew for visual and photographic reconnaissance of railway traffic in the area of Szczecinek, Grzmiaca, Barwice, Połczyn Zdrój and Czaplinek. During the task, he attacked trains at Dalęcino and Grzmiąc stations, and two cars near Czaplinek, which were damaged. On February 27, he performed a similar task in the area of Drawsko Pomorskie and Złocieniec. And this time he shot at the train at the station in Złocieniec, defended by a battery of anti-aircraft guns.

On March 1, Broch completed the last mission from Sanniki, escorting eight Il-2s to the Wierzchów area. He himself also used on-board weapons, attacking infantry in the trenches near Żabin. Two days later, the 1st Regiment was moved to the recently captured Mirosławiec airport, from which the unit took part in further flights to support the 1st Polish Army fighting to capture Kołobrzeg. From there, on March 11, 1945, Broch flew in the cover of four Il-2s over “Festung Kolberg”, i.e. stubbornly defended by Wehrmacht troops (including navy and air force) and Waffen SS Kołobrzeg. The ground guidance station warned that Focke-Wulfs might appear in the air, but the pilots saw no sign of enemy aircraft.

On March 15, 1945, Broch took off at 11:20 at the controls of Yak-9M No. 81 [serial number 3315381, via ARMA HOBBY News Blog] as side [wingman] to second lieutenant Vsevolod Bobrowski. It was his 17th combat flight and – as it turned out – the last. The task of the pair was to patrol the skies over Kołobrzeg in order to provide cover for Il-2 Shturmoviks, which were to attack ground targets. Over the coast, Broch separated from Bobrowski and disappeared. His leader circled for a long time looking for the wingman, returning to base on the last of the fuel after 2 hours and 45 minutes of flight. To this day, it is not clear what happened to the pilot. For years, it was reported in the literature that he was lost in the waves of the Baltic Sea, which, however, is not true, because his body was found and buried.

Ensign Aleksander Broch rests in a mass grave of soldiers of the Polish People’s Army at the War Cemetery in Kołobrzeg.

Wojciech Zmyślony

Sources:

Photo from the collection of Mr. Kazimierz Rutenberg

Documents from the Registry Office in Przemyśl

Documents from the Yad Vashem Institute in Jerusalem

Bulzacki Z., Logbook of flights and combat and reconnaissance reports of the 1st Regiment “Warszawa”, b.w., Poznań 1976

Sławiński K., The First Hunter, Publishing House MON, Warsaw 1980

✡ ✡

This representative image of Yak-1B fighters (not the Yak-9 which was piloted by Ensign Broch, though the general appearance is very similar) of “Warszawa” is from “Four Fours” at Arma Hobby’s News Blog. Caption: “Jak-1b No 4, 1 eskadra (squadron) of the 1 Regiment piloted by chor. pil. Edward Chromy. In the background is the aeroplane No 13 from 2 eskadra. Artwork by Marcin Górecki.”

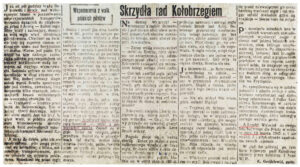

Here’s a translation of Polska Zbrojna’s 1947 article about Broch’s last mission. The translation is followed by four maps, a transcript of the article in Polish, and then, an image of the article.

Wings over Kołobrzeg

Memories of the Fights of Polish Pilots

Armed Poland

March 18, 1947

For half an hour now, Bobrowski and Broch have been cruising over the rough waves, looking for enemy sea transports heading for Kolobrzeg, which is besieged by the First Army. Strong winds and driving winds carrying fog make patrolling difficult. At times the world becomes completely dark with clouds floating low over the horizon. The sea is empty. Don’t see any movement on it. Pilots’ eyes, accustomed to the brightness of the landscape, become tired and tired from constant looking. Second after second, builds into a long rosary of minutes. No; no change. Suddenly, Broch’s hawk-like gaze notices, beneath the dark, blurred horizon, several black, monotonous lines swinging on the perpetually wavering waves.

– Transport! – he shouts over the radio to Bobrowski. In an instant, he notices the barely visible ships. There’s three of them. In the depths of the water, near the ships, the spindly shapes of two submarines escorting the transport glide. Direction: Kolobrzeg.

And now let’s get to work, until they are spotted, until they can take a closer look at the German transports, until the on-board artillery responds. They made their way through the fog and rain and went two stones [?] down, straight towards the steamships. – One larger one with a characteristic bulge in the hull – a tanker; two smaller ones, full of equipment and combat reinforcements, filled to the decks – he calculates quickly. Bobrowski and pulls the [control] stick slightly so as not to fall into the ship’s large, smoking stack. And Broch is already playing with his “machines” [machine guns] on the decks; on the sides, on the stacks – a hurricane is breaking through the sky after the Germans who were not expecting an attack. A few more series – a faint flash down below.

The fire smolders for a while; twitches awkwardly. Will it go off? [Will it explode?] As if in response, a terrible shock shook the air; the air heaved and vibrated with smoke and fire. It’s getting hot. The middle ship carrying gasoline disappeared from the sea surface. It sank into the depths. Only in the place where the ship was swinging in front of the waves in the waves, the sea was strangely luminous, full of long spots burning with luxuriant flame. A strange and terrible, unforgettable image of the burning sea.

That’s enough for today! – Bobrowski shouts with joy and, under heavy fire from the artillery of the remaining ships [?], they return to the shore to submit a report to the command.

Sending shturmoviks now! – he says to Broch, strangely unenthusiastic about the success he has just achieved. Bobrowski, concerned about his friend’s silence, exhorts on the radio:

Did the eagle become so silent as if he had drunk German gasoline? But Broch is silent. Only after a while, when they reach the coast, his voice is heard in the host’s headphones: Listen, if something happens to me, write home to [?] parents, okay?

Bobrowski suffers. He thinks for a moment; his thoughts come together. Then he bursts out: Whatever comes to mind, don’t stop the _____! – and listen to the _____. But Broch is silent.

The weather is deteriorating with every moment. Immediately after passing the coastal strip, they fall into such fog that they lose themselves completely. Conscious, attentive to everything, the patrol commander takes a sharp 180-degree turn, trying to turn around and avoid the fog sideways. Broch flies on. Bobrowski, terrified by his friend’s absence, constantly calls on him to change course like he did. The pilot hears him, faintly at first, but he does not respond. And the fog grows and then disappears. Just a moment and you won’t be able to turn back. When this difficult moment passes, Broch is gone.

This is Bobrowski… This is Bobrowski… I’m going to pick up… – Broch… Broch… Where are you? – a dramatic question flies into space. Out of nowhere, as if out of this world, the answer comes back.

No, I can’t see! I don’t know where I am! Light!…

Keep to the seashore! – advises the concerned friend, because in the meantime he is losing his orientation, unable to find any point of support on the ground covered with spring snow. Not a single river down there, but full of ash-covered railway junctions and forests. Forest everywhere. Minute by minute passes. Broch no longer responds to the radio signal at all.

Apparently he went over the sea – Bobrowski thought and, afraid of the tentacles of fog that were covering him more and more and unable to determine exactly where he was – he was heading south.

After ten minutes of flight in difficult weather conditions, he suddenly jumped out of the clouds over a German city, next to which there was a lake. Following the characteristic, broken shoreline of the lake, which he knew from the flight routes in this area, he realized that he was over Walcz, located at the intersection of large roads, 30 km away from the home airport in Frydland [Pravdinsk].

After reporting to the headquarters of the unit and reporting on the flight, attack aircraft of the 3rd Assault Aviation Regiment accompanied by fighters were immediately sent over Kolobrzeg. They destroyed the German sea transport, which sank at the very entrance of the port.

And Broch? He left his combat flight for Poland on Saturday, March 15, 1945, and did not return. And the Baltic Sea jealously guards its secrets.

Five days later, after this combat flight, Kolobrzeg fell and was captured by the soldiers of the First Polish Army.

K. Gozdziewki, second lieutenant

The Baltic Sea relative to Poland, Russia, Latvia, Sweden, Denmark, and Germany, with Kolobrzeg in the map’s lower center.

A “close-up” of Kolobrzeg and nearby Polish coastline.

Kolobrzeg, showing Walcz to the south-southeast.

Kolobrzeg, with Walcz denoted by the circle to the south-southeast, and the location of Frydland (Pravdinsk), southeast of Kaliningrad, to the east. Though the Polska Zbrojna article indicates that the latter two locations are 30 kilometers from one another, in reality, they’re much (much) farther apart.

Skrzydła nad Kołobrzegiem

Wspomnienia z walk polskich pilotów

Polska Zbrojna

March 18, 1947

Już od pól godziny kraża Bobrowski i Broch nad wzburzonymi falami w poszukiwaniu nieprzyjacielskich transportów morskich dażacych do oblężonego przez l Armie – Kolobrzegu. Silny wiatr i zacinajacy, niosacy ze soba mgle wiatr ultrudniaja patrolowanie. Chwilami na świecie robi sie zupelnie ciemno od sunacych nisko nad horzyontem – chmur. Morze jest puste. Nie wiadę na nim zadnego ruchu. Oczy pilotów przyzwyczajene od zrólany krajobrazow nuża sie i mecza od ciaglego wypatrywania. Sekunda uplywa za sekunda narastajac w dlugi różaniec minut. Nie, żadnej zmainy. Nagle sokoli wrzok Brocha sposlrzega hen pod ciemna, zamazana linia horyzontu kilka czarnych, jednostajnych kresek rozhuśtanych na wieczystej chwiejbie fal.

– Transport! – krzyczy przez radio do Bobrowskiego. Ten w jednej chwili dostrzega, ledwie widocżene statki. Jest ich trzy. W glebi wody, w poblizu statków suna wrzecionowete ksztnity dwóch lodzi podwodnych eskortujacych transport. Kiorunek: Kolobrzeg.

A teraz do dziela, póki ich nie spostrzezono, póki moga przyjrzeć sie dokladniej, z bliska, niemieckim transportowcom, poki nie odezwie sie artyleria pokladowa. Przerżneli sie przez mgly i deszcz i poszli jak dwa kamienie w dól, prosto na sunace parowce. – Jeden wiekszy z charakterystycznym wybrzuszeniem kadluba – cysterna, dwa mniejsze, pelne sprzetu i posilków bojowych, zapelnione aż po pklady – oblicza szybko. Bobrowski i sciaga lekko drazek na siebie azeby nie wpakować sie na wielki, dymiacy komin statku. A Broch już gra ze swoich „maszynek“ po pokladach; po burtach, po kominach – przewala sie pak nuragan po niesposdziewajacych sie ataku szwabach. Jeszece kilka serii – nikly blysk w dole.

Ogień tli sie chwile, pelza niezdarnie drga. Zgaśnie? Jakby w ódpowiedzi powietrzem targa potworny wstrzas powietme laluje i drga od dymu j zara. Robi sie goraco. Środkowy statek wiozacy benzyne – znikl z powierzchni morza. Zapadl sie w glab. Tylko na mieiscu, gdzie przedtyni huśtal sie w przyplywach fal statek, morze bylo dziwnie świetliste, pelne dlustych plam palacych sie bujnyn piomieniem. Dziwny i straszny, mezapomnlany obraz palacego sie morza.

Na dzisiaj wyzarczy! – wrzeszczy z radoni Bobrowski i pod silnym obstnalem artyleril pozostalych okreów zawracajo do brzegu, ażeb zlożyć raport dowództwu.

Zaraz wyśla szurmowców! – mówi do Brocha, dóry dziwnie nie entuzjazmuje sie odniesionym przed chwila sukcesem. Bobrowski zaniepokoony milczeniem kolegi nalega przez radio:

Cos tak zamilkl ragle jakbyś napil sie benzyny nienieckiej? Lecz Broch milczy. Dopiero po chwili, gdy dolatuja uż do wybrzeża odzywa sie jego glos w sluchawkach prowadzicego: Sluchajl Gdyby _e ze mna cós stalo napisz do domu, do rodżicow, dobrze?

Bobrowski cierpnie. Chwile zastanawia sie, zbiena myśli. Po tym wybucha: Co_i_do glowy przyszlo nie zawrazaj gitary! – i nadsluchuje pinie. Lecz Broch milczy.

Pogoda psuje sie z każda chwila Zaraz po minec u pasa nadbrzeznego wpadaja w takamgle, że traca siebie z oezu zupelnie Przytomny baczny n wszystko dowodea patrolu kiadze sie w ostry skreto 180 st. próbujac zawrócić i ominać mgle bokiem. Broch leci dalej. Bobrowski przerażony nieobecnościa kolegi nawoluje go bez przerwy, ażeby zmienil tak jak i on kurs. Pilot sluszy go, wptawdzie slabo, ale slyszy i nie odpowida. A mgla rośnie, poteż nieje. Jeszcze chwila i nie bedzie można już zawrocic. Gdy mija ta ciezka chwila, Broche nie ma.

Ja Bobrowski… ja Bobrowski… przechodze na odbiór… – Broch… Broch… gdzie jesteś? – leci w przestrzeń dramatyezne pytanie. Skadś z daieka, jakby juz nie z tego świata wraca odpowiedż.

Nie nie widze! Nie wiem, gdzie jestem! Bladze!

Trzymaj sie brzegu morskiego morza! – radzi zatroskany kolega, bo w miedzyczasie sam traci orientacje, nie mogac znależć na zasnutej wiosenna sazruga ziemi żadnego punktu oparcia. Ani jednej rzeki, tam w dole, pelno zato popiatanych wezlów kolejowych i lasy. Wszedzie las. Mija minuta za minuta. Broch nie odpowiada juz wcale na sygnal radia.

Widocznie poszedi nad morze – mysil Bobrowski i rainiac sie przed zalewajacymi go coraz bardziej mackami mgly i nie mogac ustalić dokladnie gdzie sie znajudje – bierze kurs na poludnie.

Po dziesieciu minutach lotu w cieżkich warunkach atmosferycznych wyskoczyi nagle z chmur nad jakims miastem niemieckim, obok ktorego znajdowalo sie jezioro. Po charakterystycznej, lamanej linii brzegow jeziora, ktore znat z poprze laieb przelotow w tym rejonie uzmyslowil sobie, że znajduje sie nad Walczem leżacym na skrzyzowaniu wielkich dróg w odlegiośei 30 km. od [błąd!] macierzystgo iotniska we Frydladzie [Pravdinsk].

Po zameldowaniu sie w sztabie jednosiki i zadniu relacji z lotu, wyslano natychmiast nad Kolobrzeg szturmowce 3 Pulku Lotnictwa Szturmowego w asyśnie mysliwców. Dokonaly one dziela zniszczenia niemieckiego transportu morskiego, który zatonal u samego wejścia portu.

A Broch? Wylecial do swego lotu bojovego dla Polski w sebote dnia 15 marca 1945 r. i nie wrócil. A Baltyk strzeże zazdrośnie swoich tajemnic.

W pieć dni póżniej po tym locie bojowym padl Kolobrzeg zdobyty przez żolnierzy I Armi W.P.

K. Gożdziewki, ppor.

The article, from Yad Vashem…

✡ ✡

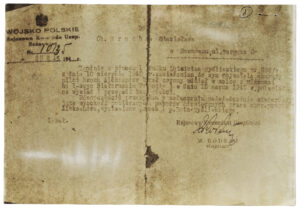

Here’s Chaplain Rozdai’s letter to Aleksander father Stanislaus…

For

Citizen Stanislaw Broch

in Sosnowiec, 20 Targowa Street

According to the letter of the 1st Fighter Aviation Regiment No. 898/I of August 10, 1945 I will inform you that the son of the citizen, ensign pilot Broch Aleksander, took an active part in the fight against the Germans in the 1st Belarusian Front and on March 15, 1945, he flew on reconnaissance and disappeared without a trace.

At the same time, I am enclosing a certificate attesting to the amount of monthly salaries received by warrant officer Aleksander, issued by Lieutenant Myśliwski.

1 enclosure

Supplementary District Commandant

M. RODZAI

Chaplain

…and, the document in the original Polish.

Do

Ob. [Obywatel] Brocha Stanisława

w Sosnowcu, ul. [ulica] Targowa 20

Zgndnie z pismem l Pulku Lotnictwa Myśliwskiego Nr 898/I z dnia 10 sierpnia 1945 Pr. zawiadsmiem, że syn Obywatela chorazy pilot Broch Aleksander brał czynny udział w walce z Niemcami na l-szym Białoruskim Froncie i w dniu 15 marca 1945 r. poleciał na wywiad i przepad ł ben wieści.

Równocześnie przesyłam w załaczeniu zaświadczenie atwierd za jace wysokość pobiernayc_ poborów miesioczynch przez chor. proc__ Aleksandra, wystawione przez l p. Letn-Myśliwskiego.

1 zał. [załącznik]

Rejenowy Komedant Uzupełnienie

M. RODZAI

Kaplian

The original document, from Yad Vashem…

One reference…

Meirtchak, Benjamin, Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II: I – Jewish Soldiers and Officers of the Polish People’s Army Killed and Missing in Action 1943-1945, World Federation of Jewish Fighters Partisans and Camp Inmates: Association of Jewish War Veterans of the Polish Armies in Israel, Tel Aviv, Israel, 1994