…there had been not just one shell but eleven of them in the gas tanks

– eleven unexploded shells

where only one would have sufficed to blast us out of the sky

with no time for chutes.

It was as if the sea had been parted for us.

Even after thirty-five years so awesome an event leaves me shaken.

But before Bohn finished the story there would be both more and less to wonder at.

He spun it out.

Elmer Bendiner stands before the nose of Flying Fortress Tondelayo (B-17F 42-29896, squadron identification marking “FO * V“). Photo from Silvertail Books.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Elmer Bendiner’s writing of The Fall of Fortresses during the late 1970s doubtless presented him with a literary quandary: How should an author structure his book so that it presents a picture of aerial combat that’s historically accurate in its recounting of history, events, and personalities, and at the same time is intellectually and emotionally compelling. One way would be by recounting the events of each of his twenty-five missions, whether “routine” or singularly memorable, in chronological order, which could lend his book a rote, dry, repetitive air. Another way would be by focusing on those particular missions or events – few in number – which by their significance and unusual nature left indelible impressions upon the author. It’s by following the latter course that Bendiner created his memoir, and in this, three particular missions stand out: A mission to Kassel, Germany on July 30, 1943; a September 6, 1943 mission to Stuttgart, and on November 30, 1943, Bendiner’s final combat mission, to Bremen, Germany, on November 29, 1943.

It’s those three flights that – excerpted from his memoir – will be presented in this series of posts. First, though, it’s time to introduce Elmer Bendiner’s crew.

The Crew of Tondelayo

To begin, here are the very few photographs of Bendiner’s fellow crew members that I know of. The first two come from The Fall of Fortresses.

Here’s his pilot, 2 Lt. Bohn Edgar Fawkes, Jr.

And, his bombardier, 2 Lt. Robert Lawrence Hejny

From Ancestry.com, here’s the 1934 Austin (Texas) high school graduation portrait of “Larry”: T/Sgt. Lawrence Harris Reedman, the crew’s Flight Engineer

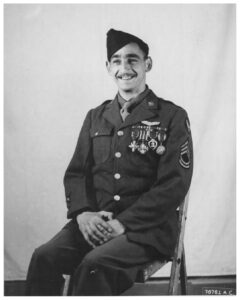

Having started with Fawkes and Hejny in Tondelayo’s “nose”, we’ll symbolically work our way back to Tondelayo’s “tail”: And so, fittingly, here are some pictures of tail gunner T/Sgt. Michael Louis Arooth.

This undated image of T/Sgt. Arooth is Army Air Force photograph 78761AC / A8882. The date of the photo is unknown, but given that he’s wearing the Air Medal, Distinguished Flying Cross, Distinguished Service Cross, and particularly the Purple Heart (he was wounded on July 30 and injured on September 6), the picture was presumably taken at or near the end of his combat tour.

This picture of T/Sgt. Arooth is from the WW II Uncovered Facebook Page (9/29/20) and shows the Sergeant making a radio broadcast, location unknown.

Unfortunately, I don’t have the source of this image, but I’m certain the picture also shows T/Sgt. Arooth. Given that Tondelayo is adorned with several swastikas denoting victory claims over German fighters (unlike in the picture with Elmer Bendiner, where it seems to bear none), the picture was obviously taken before the bomber’s loss on September 6, 1943, during the latter part of its service in the 527th Bomb Squadron.

At the U.S. Militaria Forum, here’s another picture of Sgt. Arooth, probably taken when he was training in the United States.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

If I have any criticism of The Fall of Fortresses, it’s this: Given that Bendiner’s personal records, diary, and letters, and doubtless photographs survived the war, it’s a pity that more of his personal photos weren’t included in the book. Other than the pictures of Fawkes, Hejny, and the author, the memoir is entirely absent of images of the author’s family, the rest of his crew, B-17s, or Kimbolton. It’s a pity. What was G.P. Putnam’s Sons thinking???

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

This photograph, Army Air Force picture C-71023AC / A11454 (it can be found at Fold3 and the American Air Museum in Britain, as UPL 41323), shows Tondelayo and (at least some of) Bendiner’s crew, at the 379th Bomb Group’s base in Kimbolton, England.

Fold3 contributor patootie63 has two entries at listing the names of the men in the photo.

One entry states: “Could be Carnal’ crew : Lt Walter Flower Carnal (pilot) was born on dec 1st, 1918 – passed away on july 28th, 2010 (POW on 14 oct 1943, flying aboard 42-3269 “Picadilly Willy”) Lt William S Davidson (copilot) POW Lt Morris Konier (navigator) POW 1 Lt Leslie M Gross (bombardier) KIA on oct 14th, 1943 T/Sgt Leonard Frederick Cruzan (radio) POW – was born on dec 16th, 1919 – passed away on june 30th, 2014 – Sgt Norbert Stephen Jost (engineer) was born on nov 19th, 1919 – passed away on july 8th, 2002 POW S/Sgt Donald S Sherman (ball turret gunner) was born on nov 29th, 1920 – passed away on june 1st, 1945 POW S/Sgt Nick G Rukavina (right waist gunner) KIA on oct 14th, 1943 S/Sgt Monico R Rodriquez (left waist gunner) POW S/Sgt Milton M Fisher (tail gunner) POW”

The above caption is hyperlinked to four men in the photo. In center rear is Bohn Fawkes, while in front row second from left is S/Sgt. Monico Rodriquez, fourth from left is S/Sgt. Donald Sherman, and fifth from left is Sgt. Arooth.

(The above entry also states that the photo was taken on July 12, 1943. Which makes sense, given that the bomber was lost in early September.)

And the other: “This is Fawkes’ crew : 2Lt Bohn E Fawkes Jr (pilot) 2 Lt Charles A Mauldin (co-pilot) born on sept 2nd, 1919 – passed away on feb 17th, 2007 2 Lt Elmer S Bendiner (navigator) 2 Lt Robert L Hejny (bombardier) born on jan 5th, 1920 – passed away on aug 5th, 1985 T/Sgt Frederick J Reinhard (radio operator) T/Sgt Lawrence H Reedman (engineer) T/Sgt Walter J Gray (ball turret gunner) S/Sgt Harry L Edwards (right waist gunner) S/Sgt John A Leary (left waist gunner) T/Sgt Michael Arooth (tail gunner)”

In Fold 3, the above caption is hyperlinked to three men in the photo. Second from rear is Elmer Bendiner, in center rear is Bohn Fawkes, and at far right front is (again) Sgt. Arooth. The above crew list also accompanies the photo as it appears at the American Air Museum in Britain.

So, in light of both of patootie63’s entries, we have identities in the crew photo for Elmer Bendiner, Bohn Fawkes, Michael Rodriquez, and Michael Arooth. However, based on the Fawkes’ crew list as presented in patootie63’s “second” entry (just above), which is repeated at the American Air Museum in England, and a reading of The Fall of Fortresses, the actual Fawkes’ crew – at least, those men with whom Bendiner flew his missions, and/or are mentioned or alluded to in his book – is listed below. The men’s names are accompanied by their ranks, serial numbers, names of next of kin, wartime residential addresses, date of birth, and (alas) inevitably – this being the year 2024 – date of death. This information is derived from a deep perusal of Ancestry.com, and, FindAGrave, the latter evident via the hyperlinks. In this manner, I was able to find definitive information about all but three men: Radio Operator Frederick Reinhard, Ball Turret Gunner Walter Gray, and replacement Waist Gunner Henry J. Edwards.

An observation: Remarkably, though two members of this crew (waist gunners Herring and Stockman) became POWs, and one man (Michael Arooth) was wounded and injured, every man listed below survived combat, and, survived the war. The last surviving crew member was Charles Augustus Mauldin, who died at the age of eighty-seven in 2009.

Their Names

Pilot: Fawkes, Bohn Edgar, Jr., 2 Lt., 0-410814

Mr. and Mrs. Bohn Edgar (6/12/92-2/8/46) and Inez E. (1893-1959) Fawkes (parents)

2426 Irving St., Minneapolis, Mn.

Born Minneapolis, Mn. 9/2/19 – Died 2/17/07

Co-Pilot: Mauldin, Charles Augustus, 2 Lt., 0-794438

Mr. and Mrs. Charles “Charlie” (9/16/83-1/1/30) and Ethel Charity (Dutherage or Duthridge) (8/31/91-8/22/81) Mauldin (step-parents)

2310 6th Ave., Columbus, Ga.

Born in Mississippi; 5/5/22 – Died 6/1/09

Navigator: Bendiner, Elmer Stanley, 2 Lt., 0-797240

Mr. and Mrs. William (Wilhelm) [7/31/25] and Lillian (Schwartz) Bendiner (parents)

2664 Grand Concourse, Bronx, N.Y.

187 North Ocean Ave., Freeport, N.Y.

Bertram, Evelyn, Lawrence, Marvin and Milton Bendiner (brothers and sisters)

Born Scottsdale, Pa.; 2/11/16 – Died 9/16/01

Brooklyn Eagle 12/6/44

Bombardier: Hejny, Robert Lawrence, 2 Lt., 0-734342

Mrs. Dorothy Mae Webster (wife); Married 1/26/44 – Divorced 9/3/81

Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Anton (3/19/87-1965) and Elizabeth M. (Spinler) (1901-1994) Hejny (parents); Barbara, Daniel, and Raymond (sister and brothers)

1808 East 7th St., St. Paul, Mn.

Born Pine City, Mn.; 1/5/20 – Died 8/5/85

Flight Engineer: Reedman, Lawrence Harris, T/Sgt., 18089373

Mr. and Mrs. Samuel “Sam” (4/7/89-5/21/74) and Sarah D. (Rosenthroh) (9/15/91-6/27/75) Reedman (parents)

Miss Lilian Charlotte Reedman (sister) (2/8/11-6/18/98)

2515 North Stanton St., El Paso, Tx.

Born St. Louis, Mo.; 2/12/17 – Died 3/29/08

Radio Operator: Reinhard, Frederick W. “Duke“, T/Sgt., 32338340

(Is this him?)

From New York, N.Y.

Born 1916

Gunner (Ball Turret): Gray, Walter J., T/Sgt. (33301215?)

(According to a memorial at Fold3, T/Sgt. Gray, was born in Pittsburgh, Pa., in 1920.)

Gunner (Waist): Herring, George Edwin, Jr., S/Sgt., 19002595, Gunner (Waist)

POW – Stalag 9C (Baz Sulza)

From California

Born Oklahoma City, Ok., 12/9/19 – San Bernardino, Ca., 5/11/92

Gunner (Waist): Stockman, Herbert James, Jr., 16109833

POW – Stalag 17B (Gneixendorf)

Mrs. Murial L. (Stoll) Stockman (wife), 1626 Evans, Detroit, Mi. – Divorced 7/9/46

Mr. and Mrs. James W. and Estella (Hopwood) Stockman (parents)

Born New Castle, Pa.; 2/29/16 – Died 1/18/00

Gunner (Tail): Arooth, Michael Louis, T/Sgt., 31128966

Mr. and Mrs. Salem and Dora Mary Arooth (parents); George, Louis, Peter, and Ruth (brothers and sister)

26 Lorenzo St., Springfield, Ma.

Born Springfield, Ma.; 7/31/19 – Died 2/15/90

Post 7/30/43, Herring and Stockman were presumably replaced by:

Edwards, Henry J., S/Sgt.

Leary, John Anthony, S/Sgt., 13028387

Mrs. George F. Lehman (aunt), 2111 66th Ave., Philadelphia, Pa.

Born Philadelphia, Pa.; 2/3/23 – Died 9/16/99

Separated from active service Feb. 2, 1944, at Tilton Gen. Hosp., Fort Dix, N.J.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

So, we’ll start with the mission of July 30, 1943, which was triply and dramatically significant.

First, the B-17’s wings were struck by eleven 20mm cannon shells fired by attacking Me-109s or FW-190s, none of which, though effectively embedded in the plane’s fuel tanks, failed to explode. (Otherwise Bendiner probably would not have survived to write his memoir, I wouldn’t be bringing you this set of blog posts, and you wouldn’t necessarily be visiting this blog.) The very nature of the damage incurred by the plane, and the actual reason that the several cannon shells failed to detonate, was only revealed to Bendiner during a get-together with Bohn Fawkes in Tarrytown, New York, probably (given the year The Fall of Fortresses was published) in the late 1970s.

(I once encountered a YouTube video about this incident, but the URL has since slipped through my pixels and spreadsheets.)

Second, the B-17’s oxygen system was damaged during the fighter attack, eventuating in the plane’s radio operator, ball turret gunner, and both waist gunners experiencing anoxia, with the waist gunners parachuting from the aircraft.

Third, tail gunner Michael Arooth was wounded and also anoxic, yet remained at his position and continued to defend the bomber. This is the incident for which he received the Distinguished Service Cross, as issued in European Theater of Operations U.S. Army General Orders No. 61 of September 10, 1943. Here the text of Arooth’s award citation, as found at Hall of Valor: The Military Medals Database:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Staff Sergeant Michael Arooth (ASN: 31128966), United States Army Air Forces, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy while serving as Tail Gunner in a B-17 Heavy Bomber of the 527th Bombardment Squadron, 379th Bombardment Group (H), EIGHTH Air Force, while participating in a bombing mission on 30 July 1943, against enemy ground targets in Germany. On that date, Sergeant Arooth’s B-17 was attacked by a large force of enemy fighters. During the course of these determined attacks, Sergeant Arooth destroyed three enemy airplanes and, while firing his guns, was wounded by an exploding cannon shell. His left gun was jammed by enemy fire, his oxygen supply line was broken, and the interphone system was inoperative. The pilot was forced to use violent evasive action, and several members of the crew, thinking the airplane was out of control, bailed out. When this occurred, Sergeant Arooth gave up his attempts to reach his emergency oxygen system, returned to his one remaining gun, and continued to fight off enemy attacks. Without oxygen, and with his leg shattered and bleeding, Sergeant Arooth, displaying extraordinary heroism and with complete disregard for his personal safety, remained at his post and defended his airplane and crew with his one good gun. When this gun jammed he skillfully repaired the malfunction, resumed firing, and destroyed his fourth airplane. The extraordinary heroism, coolness, and skill displayed by Sergeant Arooth on this occasion reflect high credit upon himself and the armed forces of the United States.

In the hands of a skilled writer, any of these events could serve as the basis for a chapter (or two), yet Bendiner seamlessly wove them together into a single story. Or, chapter, to be precise.

As for myself, my first encounter with this chapter of Bendiner’s book sparked an interest in obtaining the Missing Air Crew Report (MACR) covering the loss of the plane’s waist gunners, whose full names are not given in Bendiner’s text, with one name is misspelled. (“Herrin”, not the correct “Herring.) I was at first puzzled a few decades ago when an inquiry to NARA revealed that there was no MACR pertaining to this event. Only later did I learn that the time frame of the incident – the summer of 1943 – was coincident with the Army Air Force’s implementation of the use of these documents, this event bureaucratically “falling through the cracks”, as it were, accounting for the absence of a MACR. However, the American Air Museum in Britain revealed that the events in this story occurred aboard Mystic, officially known as B-17F 42-5820. As you can see from the crew list above, both Herring and Stockman survived as POWs. They were apparently replaced by S/Sgts. Henry J. Edwards and John Anthony Leary.

Mystic did not finish the war. The plane was lost during a mission to Gelsenkirchen on August 12, 1943, after having been transferred to the 526th Bomb Squadron as LF * C. It was piloted by 2 Lt. Kurt W. Freund, with seven of its ten crewmen surviving. Having crashed near Leinersdorf (11 km north of Ahrweiler) its loss is covered in MACRs 1359 and 2340, and, Luftgaukommando Report KU 21.

So, here’s Elmer Bendiner’s chronicle the events of eighty-one years ago:

“This is all we can do for you now.”

The following morning we were up again in the cold predawn to find ourselves a broken family. Tondelayo was being fitted with new props. The colonel had commandeered our gunners for his lead ship – a tribute, of course. Bohn was to replace Mike in the tail position, as was the custom when the colonel took over. And since Dutch, the group navigator, would be riding with the colonel, I was fobbed off on a squadron lead.

Johnny was assigned as co-pilot with still another crew. We had been operational for almost two months and we had lost seventy-five percent of our original crews. Replacements were arriving, but as Arnold reminded Eaker, we had to salvage what we could. To some Johnny must have looked salvageable.

We do not know precisely what went on inside the cockpit of Johnny’s plane on the mission that day. Some said they saw the plane slip back and drop below the formation with one engine smoking, then blazing. Four chutes opened, they say. I was not there, because the plane on which I rode that day developed one of those mechanical symptoms that used to afflict us in Johnny’s time. Again the cockpit asked me for a heading home, and after five hours we made it back to Kimbolton for coffee and the anxious tally of our wild geese. They came in across a sweep of sky still brilliant in the late afternoon.

I look over my time sheet that has been so scrupulously kept by some company clerk, and I am incredulous. One day follows another in the list of battles. There should have been time to savor and digest our fears. If on a Wednesday one watches other men die and sees one’s own death foreshadowed, it does not seem fitting to watch a similar deadly dance on Thursday and again on Friday and again on Saturday. Such a schedule can make the most awesome event a dull routine and turn battle into a business. If some morning at my present age I saw my friend and neighbor killed or if I felt the whoosh of a bullet pass my head I should want some time to think and then to scream before I faced a similar ordeal. But in those days we were too young to scream and thoughts were easily put off by the exhilaration of death’s presence. Now I can see that death is pallid and often ugly, but I confess it did not seem so then. And so we went up morning after morning in that gentle July, and on the thirtieth of that month we came to a strange milestone on the road to Schweinfurt.

It was a return visit to Kassel. We had been in action for four days running. At 0530 we were gathered in the briefing room, its bustle and its tensions as homey as a country kitchen, so quickly does the shocking become familiar. I do not remember fatigue. I had slept soundly and waked to the usual electric glare. I had bolted the usual eggs which seemed to coat one’s teeth and tongue with fine sandpaper. I had scalded my throat with coffee and smiled at myself picking a poppy. Between a yawn and a sneeze I read our fate in chalk on the battle lineup.

I do not mean to say it was a routine like a ride in the subway betwixt sleep and waking, staring at faces and behinds that are different and yet the same day after day. It would distort the reality and stretch words out of joint to pretend that it could have been so dull. In a subway the imminence of death is conjectural, problematic. In the briefing room it was certain, fierce, palpable and stimulating.

We ten in Tondelayo circled over Yorkshire, warming ourselves in the sun at eleven thousand feet, above a gray expanse of cloud. We crossed Felixstowe heading southeast at 0730, according to the map that has grown old with me for thirty-five years.

We climbed to our bombing altitude, 24,000 feet, over the North Sea and hit the Belgian coast close to the Dutch border. Out the port-side window I could see the Scheldt winding into Holland, and out the starboard window lay Bruges. It was then that our own P-47s and the RAF Bostons waggled their wings and went home. It was 0801, I noted in my log. A scribble nearby I take to mean that there were fighters. They had swarmed up from Woensdrecht Airdrome. Actually some B-26s had preceded us in the hope of drawing them off. I do not know whether those bright-yellow-nosed spitting wonders had risen to the bait of the B-26s and then gone down to gas up in time for us. Perhaps they had wisely sent up only a few to greet our decoys and held the rest in reserve for the main show.

In any case there they were, buzzing up at us from an airfield right on course. This was ideal for the Luftwaffe, because almost all of the fighters’ flying time could be spent in combat. In the previous April the Luftwaffe had fitted auxiliary fuel tanks to its fighters, which gave them perhaps two hours of high-speed, high-altitude flying time. On the day we went to Kassel the German dispatchers displayed their ingenuity by having their fighter squadrons hedge-hop from station to station along our presumed course.

Some came from Lille and arrived in time to give us trouble east of Brussels at 0817. Others came up from an airfield near Poix, too late to catch us on the way in but in plenty of time to ambush us on the way out. Some came from Brittany and Normandy and refueled at Lille.

At 0836 we were south of the Ruhr. We had weathered three heavy fighter attacks. Most of them came in from the rear of the formation, often four abreast. We in the nose felt their presence and heard the ping of shrapnel, but it was Mike who saw most of the action on the way in. Being a tail gunner is a lonely job. “It’s a good spot for praying,” Mike had said once. “You’re on your knees all the time.” The only spot that’s worse is the ball turret, where the gunner is wrapped around his gun like an anchovy or a fetus in a womb too small.

The tail usually saw more action than the belly. “The fuckin’ Germans must think all tail gunners are stupid,” Mike used to say. They came in again and again, firing, turning bottoms up and slipping away.

From Gladbeck and Cologne swarms of FWs and MEs shot up and barreled through our formation. Near Remagen I noted the fall of two enemy fighters. I fired at those arrows in the sky, but I knew that I was merely making noise to let them know we were alive on the port side. Bob’s gun kept up a ceaseless chatter and the top turret pounded like a jackhammer inside my head. Then quite suddenly the fighters vanished and left us to our bomb run and the accompanying flak. We came up on Kassel from the south. I peered over Bob’s shoulder and saw the city. We were rocked by flak. Still the motors ground on. There could be no evasive action. We would fly unswervingly through a sky of angry black shell bursts.

The bomb-bay doors of the plane ahead of us swung open. I watched the bombs tumble out helter-skelter at first, then straightening to a purposive plunge. When ours were gone, lost in the black smoke far below, Bob called out that the doors were closed and Bohn banked Tondelayo sharply to starboard. As we headed north and then west for home the flak slackened off and the fighters came back. They had been gathering all morning. It had been one hour and eleven minutes since we had entered Europe, and the Germans had had time to assemble a massive fleet of fighters, gassed up and ready.

It must have been somewhere near Recklinghausen that disaster struck. Mike called in to say he was hit in his right hand and left leg. Then followed a jumble of static and for a while we couldn’t raise him at all. Tondelayo was being knocked about the sky. Actually Bohn was climbing, diving and making corkscrew patterns in a crazy choreography designed to unsettle the fighters, who were pressing in from all sides. I kept my mind on the zigzag line we were taking across Europe. When I tried to stand, my feet slipped from under me. I clung to my desk and the gun, waiting for the attack to subside. When at last Mike came on again his words were jumbled and he sounded as if he were calling from a painfully long distance.

We drove across Germany trying to keep up with the formation, which had a ragged look, with gaping holes where planes had been. I had seen two of the group go down. The formation was turning more to the south in a beeline out of Germany, when we became aware of an alteration in the sound of flight. When Larry in the top turret eased up and when Bob’s guns stopped momentarily, Tondelayo seemed unnaturally quiet. The roar from the waist was missing. No one sang out to claim a kill or warn of fighters coming in. Bob and I looked at each other across the tops of our masks and he opened up his mike, ripping into my headset, “Bombardier to waist gunners, bombardier to waist gunners. Come in, come in.” Silence. Tondelayo climbed and plunged. “Stockman, Herrin, come in, Goddammit. Come in. Do you read me? Duke, come in. Bombardier to radio. Duke, come in.”

Tondelayd’s motors whined. Then came Mike’s voice, vague, blurred, with an odd calm: “They’re gone. Gone.”

We were 25,000 feet above Germany and they were gone. One imagines a switchboard operator saying, “Sorry, sir. They’re gone.” At the time the word itself with its nonsensical associations filled my head and left no room for irony. They had gone four miles down to the patchwork of farms I could barely see. Fighters were swarming about us, coming in at three, four, seven and eight o’clock where our guns were silent. Now and then we thought we heard a long burst from the tail, but that was all.

Bob disentangled his headset and oxygen hose. He lurched past me. His face was neither sad nor scared. I realized that he was in a rage. He went up the stepway to the cockpit. We were still in formation. I put down my pencil, unplugged my oxygen hose and my headset. I chucked my helmet aside and clambered after him. Behind the cockpit Bohn pointed to a green oxygen bottle, into which I plugged my hose like the antenna of an insect. We ducked under the turret, which was rattling in uninterrupted air-shattering streams of fire that had the sound of panic. We passed through the bomb bay along the narrow steel catwalk, past the racks that had held the bombs, and into the radio compartment. Duke was gone. We went into the waist, where blasts of cold air bit into my face. Herrin and Stockman were gone. Their masks, still attached to the oxygen outlet, flapped against the metal wall. The door had been jettisoned. Through it we stared at windy space. As Tondelayo banked and rolled I could see the distant, detached world below. Then I saw Duke. He was sitting on the floor, one leg dangling beyond the open hatch. Bob and I pulled him in across the floor past the waist ports, where the wind howled as in an arctic blizzard, where one could see the silvery wings of our enemies curvetting and spitting sparks.

The floor of the fuselage was torn in spots, the metal peeled back. Multicolored cables were in shreds. We sat Duke up in the radio room and looked to see whether he was bleeding. He was untouched, but his eyes were dreamy and he wore a smile of absurd serenity.

There was no oxygen in the rear of the plane. Mike had seen the waist gunners as they jumped, driven by lack of oxygen to illusions of impending disaster. Mike had watched their chutes open. One of them had barely cleared the horizontal stabilizer. Mike himself did not know whether the plane was actually going down. In any case there was nothing he could do about it. His arm and leg were torn and, though he was not in pain, he was groggy. He must have felt the cold, because the wires that hooked his electric suit had been cut. With his good arm he had changed the belt of ammo in his gun and eased his nerves by firing. He recalls seeing a Messerschmitt. He waited until it was two hundred yards from us, just the point, he thought, where the German would open up and blast us out of the sky. Mike let go a stream of fire that caught the fighter. It turned yellow and red, nosed upward, then spun in.

Bob hooked Duke to an oxygen bottle and stayed to take care of Mike as best he could. I hurried down to the nose, told Bohn the situation and began to work out a heading home. We had to drop to an inhabitable altitude regardless of the dangers of straggling in enemy skies. I remember looking at my watch, the minute and second hands whirling as unconcernedly as if I were on a street corner waiting for Esther. I looked out the window and, without seeming to grasp the significance of the phenomenon, noted that the propeller on engine Number Four was rigidly stationary. It had been feathered, disconnected to keep it from tearing the engine out of the wing. Black smoke streamed behind it. I drew a course that would take us across Holland dodging the flak zones listed in my flight plans. I hoped the information was reliable. I did not know. I only pretended to know. The plane dropped closer to the land. When I identified the Willems Canal in Holland, I called the cockpit to correct our heading. Our formation was above and ahead. We were alone. Mike’s gun rattled, but I did not know whether he was firing at something or to keep himself awake. The top turret answered with a roar. But then came the blessed moment when I could tear off my tin hat and my mask and breathe real air. The plexiglass of the nose had several gaping holes. We had one man wounded. We were missing two others. But we were going home. We were going to drink something hot. We were going to sleep in a bed.

The ball-turret gunner, undoubtedly anoxic as were the others in the rear of the plane, could not easily raise his turret to extricate himself without hydraulic pressure, and that had been lost when the lines were severed. Curled up in Tondelayo’s steel ball, impotent, Leary had survived because he could not follow the waist gunners out of the plane. He was barely nineteen years old, the youngest in the crew. I do not know how he withstood that torture wrapped within himself, powerless amid bullets and explosions, oppressed by the realization that at any instant he might be spattered to a mass of ugly tissue, like a cat run over on the highway. That might happen to any man in the crew, but the rest of us had the illusion of motion, of elbow room to give us security. There was nothing that Leary could do about his fate. He was as powerless as a rivet in his ball turret. He had been reduced to a neuter.

We could have brought up the ball turret by hand and released him, but we needed his gun as we needed Mike’s. When we reached the North Sea and saw the gliding shapes of friendly P-47s we brought him up. I calculated an ETA and gave it to Bohn. His voice was as even as if we were sitting on our bunks. “Roger. Thank you, Benny.”

With flares rising like Roman candles we came to Kimbolton. We bumped to a halt on the grass where we had come before when our brakes were undependable. We were late, but we were home. Mike was not badly hurt, according to our cheerful obstetrician.

“Our waist gunners are gone,” we told the debriefing officer.

“Are what?”

“Are gone.”

“What?”

“Gone.”

This battle is distinguished by a postscript which was appended some thirty-five years after the event. Bohn and I were sitting on a porch in Tarrytown, New York, on a summer evening. We were rehashing the war as ex-warriors have done since civilization invented wars. We were not seeking to dress our memories in cinematic glories or dissolve them in an alcoholic haze as veterans do. We were seeking rather to collapse the wind out of nostalgia, to see the war plain. We were trying to mount our recollections on pins so that we could study them in various lights from various angles. We were seeking to approximate an objective account of what we had seen and done.

We were reconciling scrawls from our respective logs. For example, after a raid on Münster Bohn had written: “This will make a lot of Dutch Nazis.” He no longer remembered what that meant. And I had scribbled on that day the one word “Eindhoven.” I had forgotten why. We looked at a map and saw that Eindhoven was a Dutch town not far from the German border. At the ground speed of those antique planes we flew it would have been perhaps ten minutes from Münster.

Our memories fed each other. As we talked, the scrawls unlocked cobwebbed files in our minds until at last the two comments made sense. Münster had been cloud-covered, and our formation had turned away from the target. The bomb-bay doors of our group leader were open. So were ours. Suddenly the undercast rolled away, revealing a flat green and tawny countryside. I recognized the pattern of rivers and canals. When I saw the formation prepare to bomb I yelled into the intercom that we were over Holland. As I yelled the bombs fell, and I noted that we had hit Eindhoven. It was then that Bohn had summed up in his log the political consequences. (Incidentally, I have subsequently talked with several Dutchmen who graciously forgave us, but then, none of them was under our bombs at Eindhoven.)

In any case it was in this search of the past that we came to the Kassel raid and the disappearance of our waist gunners. Over Bohn’s face came a characteristically odd, slightly mischievous grin. “You remember,” said he, “that we were hit by twenty-millimeter shells.”

That was not a singular experience for us, I pointed out. But these had hit our gas tanks, he recalled. That did indeed stir something in the archives of my brain. Somewhere I had even made a note of shell holes in gas tanks. I reflected on the miracle of a 20-mm. shell piercing the fuel tank without touching off an explosion.

Now Bohn licked his chops so that I could see that a revelation was on the verge. It was not the case of an unexploded shell in a gas tank, he said. It was not so simple a miracle. At the time Bohn too had thought it was no more than that. On the morning following Kassel, while I slept late and missed my breakfast, Bohn had gone down to ask our crew chief for that shell, as a souvenir of unbelievable luck. Marsden told Bohn that there had been not just one shell but eleven of them in the gas tanks – eleven unexploded shells where only one would have sufficed to blast us out of the sky with no time for chutes. It was as if the sea had been parted for us. Even after thirty-five years so awesome an event leaves me shaken. But before Bohn finished the story there would be both more and less to wonder at. He spun it out.

Bohn was told that the shells had been sent to the armorers to be defused. The armorers told him that Intelligence had picked them up. They could not say why.

The professorial captain of intelligence confirmed the story. Eleven shells were in fact found in Tondelayo’s tanks. No, he could not give one to Bohn. Sorry, he could not say why.

Eventually the captain broke down. Perhaps it was difficult to refuse a man like Bohn the evidence of a highly personal miracle. Perhaps it was because this captain of intelligence had briefed so many who had not come back that he treasured the one before him as a fragile relic. Or perhaps he told Bohn the truth because it was too delicious to keep to himself. He swore Bohn to secrecy.

The armorers who opened each of those shells had found no explosive charge. They were as clean as a whistle and as harmless. Empty? Not quite, said the captain, tantalizing Bohn as Bohn tantalized me.

One was not empty. It contained a carefully rolled piece of paper. On it was a scrawl in Czech. The intelligence captain had scoured Kimbolton for a man who could read Czech. The captain dropped his voice to a whisper before he repeated the message. Bohn imitated that whisper, and it set us to marveling as if the revelation were fresh and potent, not thirty-five years old and on its way to being a legend. Translated, the note read: “This is all we can do for you now.”

Here’s the Book

Bendiner, Elmer S., The Fall of Fortresses, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, N.Y., 1980

Here’s Another Book

Freeman, Roger A., The B-17 Flying Fortress Story: Design – Production – History, Arms & Armour Press, London, England, 1998