“Because he was concerned to make sure of everyone’s

safety before bailing out himself.”

A review of the history of the WW II Allied air campaign against the Axis, specifically in terms of missions conducted by aircraft manned by multiple crew members – here we’re largely talking about bombardment aircraft, though such aircraft certainly could be used for photo or weather reconnaissance, or, electronic warfare – reveals a consistent theme in the context of aircraft losses; a theme perhaps second nature and long taken-for-granted. This is revealed for the United States Army Air Force within Missing Air Crew Reports, in R.W. Chorley’s series of books covering Royal Air Force Bomber Command and, in a myriad of other references. In essence, it wasn’t at all unusual for the pilot (and co-pilot, as well) of a bomber to lose their lives in their final efforts to keep a damaged aircraft under some semblance of control in order to grant their fellow crewmen the chance for a safe bailout. There are many Missing Air Crew Report Casualty Questionnaires that are explicit in the descriptions of such events. A comprehensive review of these documents, or, a systematic tabulation of loss records in Chorley’s books, might enable a researcher to actually quantify just how often many otherwise uninjured pilots – who otherwise might have survived – gave their lives in such circumstances.

One such aviator was First Lieutenant Nathan Margolies (0-806295). The son of Moses and Rose (Blatt) Margolies, he was born in Brooklyn on July 6, 1915, and resided with his parents at 8301 Bay Parkway, in that rather well known New York borough. The recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with three Oak Leaf Clusters, and Purple Heart, his name can be found on page 387 of American Jews in World War II. His name appeared in a Casualty List released on April 19, 1945, and can also be found upon the Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery, Manila, Philippines, while a commemorative matzeva bearing his name is present at Section MF, Plot 46-D-12, at Arlington National Cemetery. His name also appears in Robert Dorr’s 7th Bombardment Group / Wing 1918-1995 (page 248) and in Chick Marrs Quinn’s The Aluminum Trail (page 389).

As indicated from this commemorative information and the latter two books – and as you’ll see from this post – he did not survive the war.

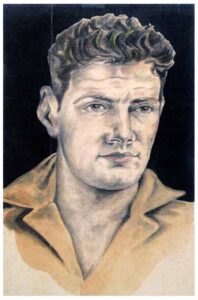

This is him…

A member of the 9th Bomb Squadron of the 10th Air Force’s 7th Bomb Group, Lt. Margolies was reportedly wounded by anti-aircraft fire on March 19, 1945. Thus, his inclusion in “this” series of blog posts concerning Jewish military casualties on March 19, 1945. However…

…he was killed during a combat mission five days later, on March 24, 1945, while in command of B-24L Liberator 44-49607 (tail number 28) during a mission from Pandaveswar, in West Bengal, India, to “Bridge Q633″ on the Burma-Siam Railway.

______________________________

The insignia of the 10th Air Force.

This example of the 9th Bomb Squadron insignia was found at Etsy. Though the gray rays in the upper half of the insignia resemble searchlight beams – as if pinpointing enemy aircraft at night – in reality, they simply form the Roman numeral “IX”, representing the number “9”. As in 9th Squadron.

______________________________

From Edward M. Young’s B-24 Liberator Units of the CBI (Osprey Combat Aircraft 87), this profile, by Mark Styling, is a representative image of the markings carried by 9th Bomb Squadron B-24s slightly before the general time-frame of the Margolies crews’ missions. This plane, B-24J 44-40857, RANGOON RANGLER, shows the squadron’s black & white checkerboard rudder with a horizontal fin band, and, plane-in-squadron number. RANGOON RANGLER survived the war with many combat missions and other sorties, and postwar was turned over to the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC). There’s no record of the Margolies crews’ 44-49607 having a nickname.

______________________________

The names and eventual fates of Lt. Margolies’ crew members on the March 24 mission are listed below:

Co-Pilot – Chaffee, Arthur Richard, 1 Lt., 0-755518, Seattle, Wa. – Survived

Navigator – Scranton, Edwin Ely, 1 Lt., 0-685742, Alliance, Oh. (See here, here, and here) – KIA

Bombardier – Meridith, James M., 1 Lt., 0-889303, Wichita, Ks. – Survived

Flight Engineer – Sadloski, Stanley P., T/Sgt., 11010475, Hartford, Ct. – Survived

Radio Operator – Nelson, James F., T/Sgt., 32086547, Brooklyn, N.Y. – Survived

Gunner – Reed, Edward, S/Sgt., 11090457, Fall River, Ma. – KIA

Gunner – Cunningham, John E., S/Sgt., 14147628, Atlanta, Ga. – KIA

Gunner – Moriarty, Leo, S/Sgt., 32185901, Ware, Ma. – Survived

Gunner – Herald, Kenneth William, S/Sgt., 39559281, Pomona, Ca. – Survived

Unlike most (most; not all) MACRs, the eyewitness statements in MACR 13435 describing 28’s loss were not recounted by crew members of other planes in the 9th’s formation. Rather, they were reported by two of Lt. Margolies’ six surviving crew members: bombardier Lt. Meredith and gunner Sgt. Herald. The MACR also includes Casualty Questionnaires filed by T/Sgt. Sadloski for his four fallen fellow crew members. Through these records, it’s possible to reconstruct what transpired over India that day, seventy-nine years ago.

First, as described by Lt. Meredith…

Were flying indicated altitude of 2500’. We were one hour and forty minutes out from the field when the oil pressure started dropping off on #1 engine [left outer engine, as viewed from above] very fast. Lt. Margolies told me to go down in the nose and salvo the bombs which I immediately did. When I crawled back up to the flight deck the engineer was salvoing the bomb bay [fuel] tank. The pilot could only get the engine partly feathered causing a terrific drag on the left side. We were losing about a thousand feet a minute so the pilot yelled “bail out”. I buckled on my chute and went out the right front bomb bay. I saw only one other parachute beside my own and did not see the plane crash.

…and then, S/Sgt. Herald:

At 11:15 it was reported that number one engine had bad oil pressure and Lt. Margolies proceeded to feather it. Due to some mechanical failure, the prop would not feather, which caused an excess of drag on our left wing forcing us to lose altitude even after out bombs and gas tank were dropped. Our pilot fought it but to no avail. The first order was to prepare for a ditching and as soon as that was given another order was to put on chutes, and there came the bail out order. The waist windows had been broken out, so as soon as we were told to bail out, I went through the right waist and hit the ground very soon after my chute opened. The altitude we went out at was about 700 ft. I hit the trees and soon joined out co-pilot and radio operator.

As indicated above, the bomber was already flying at the low altitude of 2,500 feet (remarkably low by the standards of the 8th or 15th Air Forces, but perhaps typical for a 10th Air Force mission of this nature…?) when mechanical failure – a drop in oil pressure – was encountered in the number 1 engine. (Interestingly, the header page of the MACR attributes the aircraft loss to carburetor icing, but I don’t how know (or if) such a problem could contribute to low oil pressure. Especially at low altitude. Especially in the climate of India and Burma!) Regardless, Lt. Margolies’ first command was for the crew to prepare for ditching. Immediately afterwards came an order to bail out, in light of the plane’s very rapid loss of altitude and the danger inherent to ditching a B-24 with very limited control and very little time for preparation. (Not that ditching a B-24 was easy under optimal circumstances, to begin with.)

Six crewmen left the plane: Lt. Margolies’ officers, and, Sergeants Nelson, Cunningham, and Herald.

Of the six, the parachutes of Lt. Scranton and Sgt. Cunningham were either deployed too low and too late, or, failed to open.

Four crewmen remained in the aircraft: Lt. Margolies, and Sergeants Sadloski, Reed, and Moriarty.

Of these men, Lt. Margolies, severely injured in the ditching, was unable to escape the sinking aircraft. Sgt. Reed managed to leave the wreck, but he did not survive.

Thus, from a crew of ten, six returned. Of the four who did not survive, only Sergeant Reed’s body was recovered to eventually have a place of burial.

Photos of the fallen appear below. They, and several images of Lt. Margolies, as well, have been contributed to the mens’ biographical profiles at FindAGrave by Mr. Walter N. Webb (cousin of Lt. Scranton) about whom you can read more here.

______________________________

2 Lt. Edwin F. Scranton, Navigator

______________________________

S/Sgt. John E. Cunningham, Gunner

______________________________

S/Sgt. Edward Reed, Gunner

Sgt. Reed was also “an amateur artist and wood carver and played the guitar.” This is his water-color self-portrait.

______________________________

But wait (!) there’s even more…(!!)…

In the early 2000s, Mr. Walter N. Webb, who had been researching the histories of 7th Bomb Group crews lost in WW II – with a focus on his cousin, Lt. Scranton – posted the results of his investigation at the website of the 7th Bomb Group (“7th Bombardment Group (H)”), which in 2024 is no longer “up and running”. The title of his work was: “A Special Tribute to the Margolies Crew – Photos and research by Walt Webb”.

Mr. Webb’s post includes speculation about the location where B-24 28 and her crew – both the survivors and those killed – came to earth, and, photos of the Margolies crew (and another 9th BS crew, that of 1 Lt. John F. Albert), the above-mentioned photographs of Lieutenants Margolies and Scranton, and, Sergeants Cunningham and Reed, two Google Earth images simulating the probable final course of 28, and finally, a symbolic memorial ceremony that he arranged in honor of Lieutenants Margolies and Scranton, and Sgt. Cunningham, that took place at Arlington National Cemetery on May 26, 2005.

Well, to quote from Mr. Webb’s post…

I’ve been researching a 9th Squadron crew, four of whom were killed in a March 24, 1945, air accident en route to Thailand. Three of those men still are missing in the Ganges Delta region along with their B-24. One of them was a cousin I never really knew (Lt. Edwin E. Scranton). These photos are about this crew, the last two photos are of the Arlington ceremony that I arranged for the families of the three MIAs.

I was able to download Google Earth and use it in an unusual way–to simulate the Margolies B-24 final descent route across the Ganges Delta (Mar. 24, 1945) and to visualize what the pilots saw as they crossed these islands at altitudes of 1,000 feet and below. Google Earth allows you to “fly” to any point on a 3D globe, drop to any altitude, tilt to get an oblique view, and even rotate around the target! The earth coverage comes from satellite imagery. The detail varies; major cities have the highest resolution. Since I saved the entire descent path, all I have to do to revisit is to press the “Tour” button and then watch as the path automatically runs!

I’ve used information in Mr. Webb’s post, specifically his two Google Earth maps, to build “this” post a little further, in terms of mapping and illustrating the final flight of 28 and her four fallen airmen.

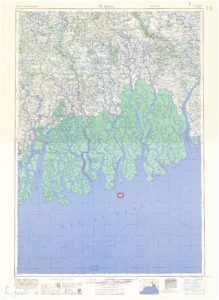

This map, included in MACR 13435, shows the last witnessed location of 28: Over the Bay of Bengal, just a few miles south of the coast of modern day Bangladesh. Note that the map is only a snippet cut from the much larger “Army / Air” 1:1,000,000 map: “NF-45”, which you’ll see with just a quick mouse scroll down.

Based on the MACR map, the map below, at a vastly smaller scale, shows the aircraft’s last reported position in the wider geographic context of the Bay of Bengal, India, Bangladesh, and Burma. It’s designated by the miniscule, almost-invisible (and really tiny) red oval in the center of the map.

Going to a larger scale, here’s 28’s last reported position in the context of the Ganges-Brahamputra Delta.

A tiny section of map NF-45 in MACR 13435 is shown above. Below, via the University of Texas, is a complete version of a later edition of the same map – “NF-45-12” (“Putney Island, Pakistan; India”) – spliced via photoshop with the adjoining map to the north, “NF-45-8” (“Khula, Pakistan; India”). These two adjoining maps, at 1:250,000 scale, were compiled in 1955 from the 1923-1942, and, 1924 Surveys of India, and are October, 1959 editions prepared by the Army Map Service and printed by the Corps of Engineers. For the purposes of this post, this photoshopped Army composite map illustrates the setting of 28’s loss in a detailed context, and clarifies a Google Earth image from Mr. Webb, which follows…

And so, more from Mr. Webb:

[Two] photos are … sample scenes from the simulation, both overviews in tilt mode. I also have views from the lower heights actually flown by the crippled aircraft along its final path.

[The first scene … (not illustrated here!) looks S to N across the bailout island where 6 of the crew jumped.] Scranton and Cunningham (chutes didn’t open) fell under the plane’s path, while the 4 on chutes probably drifted a bit to the NNE, thus shown displaced slightly in that direction. Cunningham delayed his jump and so is separated from the rest. (A British air-sea rescue eyewitness recalled seeing the parachutes hanging in the trees “in a perfectly straight line.”) Thirteen miles to the N, the 3 distant targets represent the general area where I believe the plane actually may have ditched with 4 on board (Margolies and Reed perished; only Reed was recovered.)

[This] scene … (image below!) shows approximately where the 3 crew MIAs may be located. Although the B-24 may have ditched somewhere along that stretch of the river, it’s uncertain whether the submerged wreckage still is there, lodged in the mud (the B-24 broke into 3 sections), or has drifted farther downstream.

Using Mr. Webb’s Google Earth map as a basis, here are the probable locations of Cunningham’s and Scranton’s bailout and 28’s crash, shown on Maps NF-45-12 and NF-45-8 (you can see where I spliced them by the difference in the intensity of shading), as respectively indicated by the blue circles.

A much, much closer view. Assuming that the crash location is correct, the aircraft came down in the vicinity of or in the Jamuna River.

This air photo view of the plane’s probable crash location is at the same scale as the NF-45 composite maps above….

…while this air photo is a very (very (very)) close view of this branch of the Jamuna River.

Between 2011 and 2013, the missing men and plane were the subject of discussion at Wikimapia, under the heading “crash site, invisible“.

There, this message appears: “B-24 Liberator piloted by Lt. Nathan Margolies crashed here after others bailed out(but not all survived). They were on their way to bomb a bridge on the infamous Burma-Siam Railway on 24 March 1945. Still missing are Pilot Margolies, Navigator Lt. Edwin E. Scranton, and a Gunner S/Sgt. John E. Cunningham. Navigator’s cousin still is searching for remains of both aircraft and personnel. Contact wwebb24@verizon.net. The plane took off from Pandaveswar, West Bengal, India.

Coordinates: 21°55’11″N 89°10’22″E”

This inquiry generated three comments – by Bangladesh citizens “TurboProp”, “asisdutta_jc”, and “ershadahmed”, which are presented verbatim below:

TurboProp (2011)

CALLING OFFICERS OF BANGLADESH NAVY OR COAST GUARD TO COMMENT ON THIS. THERE ARE 2 ESTABLISHMENTS–ONE WITHIN THE MARKED AREA, ONE LITTLE UPSTREAM. MAY BE THESE PEOPLE WILL HAVE SOME IDEA

13 years ago

asisdutta_jc (2012)

Condoled by SDutta: +919593000434

12 years ago

ershadahmed (2014)

Inaccessible and isolated mangrove remains inundated. Officers of Bangladesh Navy or Forest Deptt should try to locate the spot and help them finding. Its two years already, the request has been made by the US air force persons to Bangladesh Navy. Engr. Ershad Ahmed +(88-02)-01711548879 9 (cell)

10 years ago

______________________________

And, two pictures from time ago.

As mentioned above, Mr. Webb’s post from the early 2000s at the 7th Bomb Group’s website includes a photo of Lt. Margolies crew, and, a photo of the crew of 1 Lt. John F. Albert. These photos, and several other images of 9th Bomb Squadron crews, can be found in the historical records of the 9th Bomb Squadron for March, 1945.

This image shows the Margolies crew in front of B-24 squadron number 33 prior to takeoff on February 5, 1945. The mission was to bomb the pair of bridges at Kanchanaburi, Thailand. The crew had to abort and return.

The men are:

Back row, left to right:

1 Lt. James M. Meredith

S/Sgt. Edward Reed

T/Sgt. James F. Nelson

S/Sgt. John E. Cunningham

S/Sgt. Kenneth W. Herald

S/Sgt. Leo Moriarty

Cpl. John L. Sulgrove

Front row, left to right:

1 Lt. Arthur R. Chaffee

Lieutenant Margolies

T/Sgt. Stanley P. Sadloski

1 Lt. Edwin E. Scranton

This photo was also taken on February 5, 1945, and is significant in showing 44-49607, with, “…a hand-painted “28”, an indicator of its recent arrival to the squadron.”

The men are, left to right:

1 Lt. Donald P. Funk – Co-Pilot

2 Lt. Owen H. Brownfield – Bombardier

T/Sgt. Arthur L. Burdette – Flight Engineer

1 Lt. Bernard D. Kahn – Navigator

1 Lt. John F. Albert – Pilot

T/Sgt. Lyle L. Vralsted – Radio Operator

S/Sgt. H.Q. Smith – Gunner

S/Sgt. Gordon Greenberg – Gunner

S/Sgt. Paul R. Hon – Gunner

Almost seventy-nine years have transpired since the loss of “28” and her four crew members. Given the passage of time, let alone the very nature of the terrain and climate where the 44-49607 came to earth (and actually, sea) it must be accepted that the missing men and their plane will never be found. Still, a measure of memory, even if belated, is better than no memory at all.

Some Books

Dorr, Robert F., 7th Bombardment Group / Wing 1918-1995, Turner Publishing Company, Paducah, Ky., 1996

Dublin, Louis I., and Kohs, Samuel C., American Jews in World War II – The Story of 550,000 Fighters for Freedom, The Dial Press, New York, N.Y., 1947

Quinn, Chick Marrs, The Aluminum Trail – How & Where They Died – China-Burma-India World War II 1942-1945, Chick Marrs Quinn, 1989

Rust, Kenn C, Tenth Air Force Story, Historical Aviation Album, Temple City, Ca., 1980

Young, Edward M., B-24 Liberator Units of the CBI, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, England, 2011

And otherwise…

I want to express my thanks to the Air Force Historical Research Agency for the Albert and Margolies crew photos: “Thanks very much!”

AFHRA Microfilm Roll A0538