A Bad Day Over Derben

I previously wrote of the 8th Air Force’s mission to Derben, Germany – specifically focusing on the losses incurred by the 390th “Square J” Bomb Group “here”. But, there’s more…

The references I consulted for that post included both volumes (I, and II) of the 390th Memorial Museum Foundation’s 390th Bomb Group Anthology, which were published in 1983 and 1985, respectively, and edited by Wilbert H. Richarz, Richard H. Perry, and William J. Robinson. The books include five essays about the mission – three in volume one, and three in volume two – and I thought it’d be worthwhile to create another post (“this one”!) – to present their stories and broaden historical memory of the events of January Sunday in the skies west of Berlin, nearly eight decades ago. And so, below are full transcripts of written accounts by T/Sgt. George J. Zadzora and S/Sgt. Ralph K. Spence (members of the same crew), and 2 Lt. Melvin L. Johnson (volume I), as well as Lt. Rafael H. Galceran, Jr., and Sgt. Vincent K. Johnson (volume I). Of these five men, Zadzora, Spence, and Johnson did not return to Framlingham, England; they were shot down and survived as POWs. Galceran and Johnson, members of the same crew, the latter severely wounded and enduring a very long recovery, returned aboard their damaged B-17.

These stories are accompanied by images of the insignia of the 568th, 569th, and 571st Bomb Squadrons. These were scanned from Albert E. Milliken’s The Story of the 390th Bombardment Group (H).

__________

More information about the Derben mission can be found in the prior blog post. In the meantime, here are some Oogle maps and air photos showing the geographic setting of Derben relative to the Berlin metropolitan area, and, two official Army Air Force photos taken during the mission, probably from automatic strike cameras. (These images also appear at the prior post.)

This map shows the location of Derben relative to Berlin. A formerly independent municipality, in September 2001 it merged with the six municipalities of Bergzow, Ferchland, Güsen, Hohenseeden, Parey and Zerben to form the larger municipality of Elbe-Parey, which in 2021 had a population of about 6350.

Oogling in more closely reveals Derben’s street layout. As is more evident in the images below, the target of the 8th Air Force’s January 14 mission – underground petroleum storage tanks – was not located in the town itself, but instead in the undeveloped (and still so today) wooded area adjacent to the eastern edge of the municipality…

…which is revealed below, in an air photo at the same scale as the above map. Currently, the area – designated the Crosstreke Ferchland – is a location for motocross racing, evident by the numerous trails (designated in gray) through the area.

Army Air Force Photo 55871AC / A21154 shows the oil storage tank area near Derben at the beginning or in the midst of the 8th Air Force’s attack. This and the subsequent photo have been rotated, via Photoshop, such that they conform to geographic north, consistent with the maps above.

Also – presumably – photographed from the automatic camera of a higher aircraft, Army Air Force photo (56022AC / A21155) shows a 390th Bomb Group B-17G – notice the square-J on the plane’s starboard wing? – flying north-northwest over the Elbe River. Due to the dispersal of smoke and debris from bomb explosions – obscuring a wider area than in the image above – this photo was probably taken subsequent to picture 55871AC. While the municipality of Derben appears to be undamaged, it looks (?) as if some bombs have fallen onto the uninhabited land to the west of the municipality, which would account for the billowing cloud of smoke rising into the sky from that location.

______________________________

Volume I

“He Endured a 850 Mile Forced P.O.W. March”

George J. Zadzora, Radio Operator-Gunner, 568th Bomb Squadron

“Time was a commodity that we had in abundance.”

THIS was our 34th combat mission. If we completed this mission and one more then our tour of duty would be completed and we would be homeward bound — IF!

Our mission this morning January 14, 1945 took us over Germany flying a south-easterly heading toward Berlin. Our escort Mustangs were above us crisscrossing the formation, and watching over their “big brothers”. The target was underground fuel storage tanks in the Berlin area.

We were about 10 or 15 minutes away from the IP. I was in the radio room monitoring the code messages from the station in England. I looked out the window and saw a P-51 flying about 150 feet below and going in the opposite direction to the flight of the bombers. I immediately signed “off watch” on the radio log, disconnected the oxygen and intercom, went to the right waist position, connected oxygen and intercom, then unhooked the gun from its stored position.

Over the intercom gunners were calling out the location and number of enemy fighters. An FW-190 flew past, then went into a loop with a P-47 on its tail. This is the first time that I saw a Thunderbolt fending off enemy fighters so I assumed that there were a lot of enemy fighters attacking. An ME-109 passed by very close, belly towards me and I let go a long burst from the 50 calibre. The other gunners were blasting away. An FW-190 passed by in the same manner as the 109 and I gave it a long burst. I looked momentarily inside the fuselage and saw there were long openings, about 2 feet in length. These were caused by machine gun and cannon fire from enemy fighters attacking from behind.

The next thing I experienced was a sensation that felt like about a dozen bee stings. I knew I was hit. The left waist gunner, Spence, went down but got up again, so I knew he had been hit. Over the intercom came the words, “Bail out, we’re on fire.”

Horan, the ball-turret gunner, got out of the ball and clipped on his chute as did Spence in the waist. My chute was in the radio room, so I had to go there to get it. As I turned and headed for the radio room, I could see flames and a grayish smoke in the radio room. I had no choice but to go and look for my chute.

As I went into the radio room, the smoke came in contact with my eyes, they began to burn. I inhaled a small amount of smoke and began to cough. The flames were about 3 feet from me. I got down on my hands and knees, eyes closed and began searching for the chute by feeling with my hands. At first, I couldn’t find it so I began moving about on my knees and feeling for a bulge that would be the chute. It wasn’t in the usual position where I kept it, but then I felt it with one hand, then both hands to be sure. I found the chute.

I got out of the radio room fast and to the rear exit door, clipping the chute to the harness as I went. I reached the exit door and without hesitation went out feet first.

Eight or ten seconds after leaving the ship, my right hand grabbed the chute ring and pulled – nothing happened. Pulled again – nothing happened. A few more tries and no results. Thoughts went through my mind – is something stuck? There seemed to be only one thing to do and that was to use both hands on the chute ring and pull hard. This was done and the chute opened at approximately 18,000 or 19,000 feet.

As I drifted down, 2 ME-109s came into view and circled clockwise around me. They descended at the same rate as my descent. After several circles they broke away and disappeared.

The ground was getting closer now and I was drifting toward a wooded area with several open spaces. By this time, I had a good idea of where the landing would take place: in a small clearing with a scattering of small trees.

As I hit the ground, I lost my balance and fell down. I then got up, unfastened the harness, rolled it and the chute into a compact roll and hid it in the nearby woods. It was now apparent that I could walk well. I felt a severe pain in my right arm. It now dawned on me that with a wounded right arm, I didn’t have the strength to open the chute initially.

It was early afternoon, I checked the position of the sun, determined which direction was west and started walking. I found that by supporting the right arm in a position like that of being in a sling, the pain would lessen. Heading westward, I avoided small towns by walking around them, across fields and thru wooded areas staying off the roads until dusk. I came upon a haystack on the edge of a field and slept there the first night in enemy territory.

Surprisingly, I slept well that night and awoke just after dawn. Checking the position of the early sun, I headed in a westerly direction keeping off the roads to be less conspicuous. I was able to avoid people living in the area until late that morning. While crossing a small field, I was approached by 2 boys. One was about 15 years of age, the younger one about 10. I decided not to change direction or start to run but continued walking towards them until we met. The boys noticed my flight suit and asked me if I spoke German. I replied that I did not speak German in one of the few phrases I know of that language. Then I asked the older boy in the Slovak language if he understood what I said and to my astonishment, he replied in Slovak. We spoke for several minutes, then he invited me to go to his brother’s home which I assumed to be a mile or two away.

As we three walked along, we were approached by a German soldier carrying a rifle. He was about 16 years of age and began conversing in German with the two youngsters I met some 10 minutes previously. The young soldier then indicated by pointing his finger in the direction that I was to walk and he followed me, and at no time did he provoke or abuse me. I still carried my right arm as though it was in a sling. It still pained me.

We entered a small town, walked past a number of houses, then the young guard indicated to me to walk through a gateway and to the front door of a house. This house was the Burgomeister’s home.

The Burgomeister answered the door and he and the young soldier talked in German. Then I was asked to go inside the house by a hand sign along with the young soldier.

Inside the house, the Burgomeister dialed a number, presumably to notify the authorities that a prisoner was here in his home and to send a guard escort. He was on the phone for quite some time and it seemed to me that phone connections were difficult to make because of the time lapses between phone conversations and the number of times that he dialed.

The Burgomeister’s wife was there and while her husband was phoning, she indicated to me to be seated at the kitchen table. This I did. She then placed before me, two slices of bread, butter, knife and a cup of black ersatz coffee, that had an acorn-like flavor.

While eating the buttered bread and coffee, she sat down at the table and spoke in German using only basic words and hand gestures rather than long sentences. I believe that she was saying that their son was in the service and that he was about my age.

Shortly afterwards, an army truck stopped in front of the house and two guards came inside while the driver remained in the truck. It was time to go.

As I approached the front door to leave, I turned around to the Burgomeister and his wife who were standing side-by-side, and said two of the very few German words that I knew – “Danke schon” – and departed with the two guards.

We climbed in the back of the truck with a canvas cover and sat on a bench seat facing backwards with myself in the middle and the guards on either side of me. The driver started the truck and we drove off into the night to a temporary cell at a military installation where I stayed that night.

The next morning I was escorted by two guards, taken on a train from Berlin to a camp about 30 or 40 miles south of that city.

After being searched, I was led to a cell that was barricaded with a stout piece of lumber about four feet long resting on steel brackets. Removal of this lumber permitted the door to the cell to be opened and in I went. The cell was about ten feet long by six feet wide with a very small window set high in the wall near the ceiling opposite the door. The only thing that I could see when I looked out the window was the sky.

There was a bed of rough lumber with a carpet on it about four feet long and two feet wide. These were the only items in the cell.

While in the cell, I received one bowl of watery soup in the evening that was delivered to my cell. I was permitted to the latrine three times a day – morning, noon and evening, each time accompanied by a guard. There was no reading material, no one to talk with so I spent my time with my thoughts.

I spent six days at this camp where I was interrogated then taken by train northward through Berlin and Stettin then eastward to a camp somewhere in the northwest or northern part of Poland in an isolated area.

I was taken into a small room and searched by a young English-speaking German. After being searched, he showed me, by pointing, a small wooden railing about 18 inches high and about 15 feet inside the wire enclosure. It was made of about 3/4 inch square wood stock having only a top rail and supported by vertical wooden stakes driven into the ground. He warned me that if I so much as touched that wood railing the guards have orders to shoot to kill.

I was assigned to a room in one of the barracks. This room was about 20 feet square having one door, one window and a single light bulb in the center of the ceiling. The double-decker bunks of rough lumber against each of the four walls provided sleeping facilities for 16 men. With my appearance that made 24 men occupying that room. Eight of us slept on the floor without the straw mattresses.

The first thing mentioned to me by the men with whom I was to share the room was that under no circumstances should I touch the wood railing because the guards have orders to shoot to kill. I was informed that a few of our guys didn’t believe that warning, touched the railing and were shot dead by the guards in the tower.

That evening for our meal one of the fellows in our room was authorized to go to the central kitchen where the meal was prepared, usually soup with potatoes and whatever the G.I. cooks could find to add to the soup. It was brought to our room in a metal bucket and carefully ladled out so that each man would receive an equal portion. There was no meat in the soup but previously there had been. The meat came from occasional large dogs that ran loose in the compound, who were caught and added to the soup except for one tiny dog that was too small to qualify for the soup kettle so it became a pet.

Red Cross parcels were received from time to time that supplemented our evening meal of soup. Depending on the number of parcels determined the distribution to each individual. At times several G.I.s divided a food parcel and each man kept his own food supply along with a ration of bread that was provided by our captors. For anyone to steal another man’s food was considered a most serious matter.

Time was a commodity that we had in abundance. We kept occupied by walking around the compound, playing cards and checkers, reading, keeping diaries, playing soft-ball during warm weather, hand washing the few items of clothing, writing a few letters and cards per month since that is all that was permitted, making pencil sketches on paper when it was available, preparing a snack during the day from our individual food supply, making items from the cans we received in our Red Cross parcels (such as hand-operated mixers for stirring coffee, tea and powdered milk), etc.

In early February, 1945, we were told at evening roll call to be prepared to move out the next morning. Nothing was said about our destination, just pack up and be ready. About a week before I had received some new G.I. clothing and a new pair of G.I. shoes.

Extra clothing was rolled up in a small bundle to be carried along with whatever food we had, plus the blankets that were rolled up and tied with rope or a strip of cloth in such a way as to carry it like a suitcase or over the shoulder like a set of golf clubs. Immediately after morning roll call the guards escorted us out the camp and we were on our way.

We could only assume that the Russians coming from the east were getting close to this internment camp and in all likelihood we would be marching west.

The weather was cold. After walking 4 or 5 days, it was possible to determine the general direction in which we were going, using the sunrise and sunset as reference points. It was generally west.

About a day later, we crossed the Oder River, south of Stettin.

One week went by, then two weeks. Food was now more scarce. We began to search for anything edible along the road as we travelled westward. Sometimes a potato would be found by an alert pair of eyes, or perhaps a carrot or some other vegetable.

Whenever possible we were given shelter in a barn but some evenings we slept outdoors. Harry had three blankets and so did I. Three blankets were spread on the ground and the other three used to cover us. Sometimes the blankets would be spread on damp ground or damp grass since no dry places were available. Eventually the moisture would be soaked up by the blankets on which we slept which resulted in a soggy and uncomfortable night.

We walked almost every day but occasionally we would get a day’s rest. When we did, a large part of the day was spent lying to conserve our energy for the next day’s march.

During our march we crossed the Elbe river indicating that we were still going west. During the many weeks of the march, the weather varied – snow, rain, sleet, fog, sunshine – but generally cold and at times very cold. We usually travelled 15 to 25 miles per day and several times near 30 miles. Our bodies ached with fatigue and our stomachs pained for food, which was scarce causing loss of weight. We all developed short tempers. Morale was dropping even lower. Those unable to walk rode in horse-drawn wagons.

One clear morning, a few hours after sunrise, a loud noise shattered the calm air. It came from beyond a low ridge some 400 feet to our right. Moments later, a V-2 rocket appeared, accelerated rapidly and disappeared some 20 seconds later. We watched in awe while the guards, pointing fingers at the rocket, cheered loudly until it was out of sight.

We were all very fatigued from so much walking and so little food. We were taken to a P.O.W. camp at Fallingbostel which was occupied by R.A.F. internees. This camp was located about 50 miles south of Hamburg and about 160 miles west of Berlin. The camp was crowded, tents were erected and we stayed there for about 3 or 4 days. The next day an R.A.F. internee came into our tent holding a piece of paper and asked that we gather around him while lookouts were stationed at each end of the tent to notify us in case German guards came near.

He then began to read from the paper in his hand. It was the latest war news from the B.B.C.

After hearing the news, I asked one of the P.O.W.s, a Canadian, how is the news obtained? He explained that when work parties were sent out to cut wood, a few of them drifted off to where a Lancaster bomber was downed and proceeded to bring in radio parts taken from that plane. They had to be careful not to be seen by the guards as they smuggled the parts into camp. In time enough parts had been gathered, a receiver assembled, tuned to the B.B.C. frequency and the news was then handwritten on paper and read to the prisoners at Fallingbostel.

After a short rest, we were then moved out of that camp. The march began again, this time eastward crossing the Elbe River and later the Oder River. This took us back into Poland not far from our original starting point.

Part of this trip we travelled by train. I have no positive way of knowing how far we travelled but I assume it was about 60 or 70 miles. The train would rumble along then stop for hours at a time.

We were jammed into the box cars and doors locked. During the night, it was pitch black inside; during the day only a small amount of light entered the box car and this was from small cracks around the door. Those who had food could eat; those who did not couldn’t. No sanitation facilities were available, not even a bucket.

It was now about the end of March, 1945. Our march continued northward then westward from Poland for the second time. We again crossed the Oder River north of Stettin, followed the Baltic coast line, through the town of Swinemunde, then headed away from the Baltic Sea.

The days were getting longer and the weather became warmer. This was some consolation but we were still captives, hungry, weak, dirty and tired.

As we continued westward for the second time, ominous signs were evident. A flight of four Mustangs flew over at about 4,000 feet unchallenged. We went by an airfield of parked JU-88s none of which were operational; explosives were used to totally destroy the cockpits of these planes. A squadron of B-17s bombed a target several miles away at an altitude of about 4,000 or 5,000 feet with no enemy opposition.

With the Allies coming from the west and the Russians from the east, German controlled areas were considerably reduced and so were the distances that we walked each day. Now it was marches of only 5 to 8 miles each day.

Plodding along at a slow pace, we went past some buildings on a small rise of land that looked familiar. Suddenly the name came to my mind – Fallingbostel. This was the same camp where we rested some 6 weeks previously.

From the morning in early February, 1945, when we began our march, one name comes to mind immediately. The name is Dr. Pollack, an English doctor who with his medical assistants walked every mile of our trek. It was they who carried the medical supplies in addition to their possessions and administered to the wounded and sick during our entire journey.

One day after a tiring march, we stopped just outside of a small town to rest for the night. It was getting dark and we were almost totally exhausted. Dr. Pollack went to the nearby houses, knocked on doors and told the people that there were a lot of sick people in our group and requested that they bring hot water to us which they did. Buckets and buckets of hot water arrived enabling us to have a hot drink.

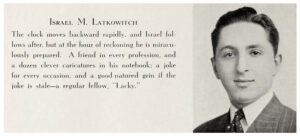

It was April 13, 1945. On this day, we walked through a small town while some of the villagers watched as we passed. One of our guys named Gunzberg spoke German fluently and stopped momentarily to talk with a few of the local inhabitants. Moments later he joined us and gave us the news that he just received and that was that President Roosevelt died yesterday, April 12. (“Gunzberg” was probably T/Sgt. Werner J. Gunzburger, a radio interceptor in 726th Bomb Squadron, 451st Bomb Group, 15th Air Force, shot down and captured July 14, 1944. Born in Landau, Germany, on January 1, 1922, he was the son of Lily Gunzburger, of Holland Street in New Orleans. One of the twelve crew members of Capt. Richard S. Long in B-24G 42-72808 (covered in MACR 6900 and Luftgaukommando Report ME 1724) – all surviving their “shoot-down” – his name does not appear in American Jews in World War II. He died in March of 1996.)

It was now late in April 1945. The outcome of the war was no longer in doubt. Our captors took us to a delousing station, divided us into groups of about 40 where we showered. Our clothing was placed in individual wire baskets and sent to a delouser. I looked at my body, arms and legs and couldn’t believe how frail I was weighing about 75 pounds. I lost nearly 100 pounds during this ordeal of nearly three months. This was the second time that I was able to take a shower. The other shower was taken during the first visit to Fallingbostel.

I wore the same clothes, day and night, during this march from when it began in early February until May 2, 1945, when we were liberated by armored units of the British Second Army.

Recently I referred to maps of our march to determine the approximate distance that we travelled. After locating the names of familiar towns, I began measuring distances from point to point on a straight line basis; the distances that we walked would be greater since we walked on secondary roads with curves, hills and frequent changes of direction.

The first leg of our journey was from our camp in Poland westward to Fallingbostel, a distance of about 300 miles. From Fallingbostel, we travelled eastward some 250 miles back to Poland. Another 50 miles northward to the coast of the Baltic Sea. Westward again to Fallingbostel for approximately 275 miles and finally about 40 miles to the northeast near the town of Luneberg where we were liberated. This comes to about 915 miles less about 75 miles for the train ride which brings the total of approximately 840 miles point to point distance.

I assume that we walked a minimum of about 850 miles and this distance was walked using a single pair of G.I. shoes.

____________________

“Tribute to Zad”

Ralph K. Spence, Waist Gunner, 568th Bomb Squadron

THIS is about our radio man, George Zadzora. The day we went down 14th January ‘45 near Berlin. I was knocked unconscious. When I came to, Zad was shooting from the right waist gun and he really made a tune on it. I was facing the radio room, the bomb-bay door was open and it looked like a furnace. I hit Zad on the leg and snowed him the fire – our wings were on fire.

He said, “Get the parachute on.” He grabbed me under the armpit and dragged me to the waist door and pulled the pin release. The door fell off and out I went with it.

He went back and got Jim Horan out of the ball turret. He was all shot up – his foot, knee and elbow. He put his parachute on him and dragged him to the door and pushed him out. By that time the smoke was so bad he had to crawl on hands and knees to find his own parachute and bail out.

I don’t think there is any medal high enough to repay Zad for his guts and courage under fire. Jim nor I could never have made it to the door without him. “Thanks again, Zad!”

George Zadzora and Ralph Spence were crewmen aboard B-17G 42-102956, BI * K, otherwise known as “Doc’s Flying Circus” / “Girl of My Dreams“. Unfortunately, there don’t seem to be any photos of this Fortress, which crashed two kilometers south of Vietznitz / three kilometers south-southeast of Friesack. As you can see from the crew list below, Lt. Paul Goodrich and S/Sgt. Losch, the bomber’s pilot and tail gunner, were killed, the bomber’s seven other crew members surviving as POWs. The plane’s loss is covered in MACR 11726 and Luftgaukommando Report KU 3570.

These two Oogle maps show the approximate crash location of Doc’s Flying Circus, based on information in KU 3570.

First, a “close-up” of Vietnitz and Friesack…

…and the crash site’s location, relative to Berlin.

This image of Paul Goodrich’s crew is via the 390th Memorial Museum. Crewmens’ names are listed below the photo.

Rear, left to right

Flight Engineer: Thomas, Jim K., T/Sgt., 38351808 – Survived (12/21/23-6/20/01)

Portales, N.M.

Dallas-Fort Worth National Cemetery, Dallas, Dallas County, Tx. – Section 10, Site 57

Gunner (Waist): In photo: Irwin, J. (Not in this crew on January 14 mission)

Radio Operator: Zadzora, George John, T/Sgt., 13083211 – Survived (4/21/24-5/7/15)

Jenners, Pa.

All Souls Cemetery, Chardon, Oh. – Section 26C, Lot 4204, Grave 2

Gunner (Waist): Spence, Ralph K., S/Sgt., 39334034 – Survived (8/2/13-2/19/91)

Vancouver, Wa.

National Memorial Cemetery of Arizona, Phoenix, Az. – Section 22B, Site 34

Gunner (Ball Turret): Horan, James M., S/Sgt., 35547195 – Survived (1/19/24-11/5/10)

Toledo, Oh.

Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Va. – Section N70QQ, Row 14, Site 1

Gunner (Tail): Losch, Leonard A., S/Sgt., 38494454 – KIA (Born 4/12/23)

New Orleans, La.

Greenwood Cemetery, New Orleans, La. – Plot 21 Lilly Cedar Aloe; Buried 6/14/49

Front, left to right

Pilot: Goodrich, Paul, 1 Lt., 0-748398 – KIA (Born 2/1/22)

Valparaiso, In.

Graceland Memorial Park, Valparaiso, In.

Co-Pilot: Thomas, Raymond E., 1 Lt., 0-771156 – Survived (Possibly 6/26/22-7/27/05)

San Gabriel, Ca.

(Possibly) Hamilton Cemetery, Tulare County, Ca.

Navigator: In photo: Nording, William L. (Not in this crew on January 14 mission)

Navigator: Not in photo: Lutzer, Erwin M., 2 Lt., 0-719973 – Survived (5/28/24-11/9/88)

Kew Gardens, N.Y.

Montefiore Cemetery, Springfield Gardens, N.Y.

Bombardier: In photo: Shipplett, Wallace Blair, 1 Lt. – KIA (Born 2/7/24)

Rowan County, N.C.

Epinal American Cemetery and Memorial, Epinal, France – Section B, Row 39, Grave 44

(Not in this crew on January 14 mission; KIA aboard B-17G 42-31744, Little Butch II)

Togglier: Not in photo: Piston, Frank H., Jr., S/Sgt., 3362401 – Survived

Lansdale, Pa.

______________________________

“Mission 243 – Derben, Germany”

Melvin L. Johnson- Navigator, 571st Squadron

“The next thing I remember I was on the snow-covered ground.”

OUR target for the January 14, 1945 mission was an oil dump near Derben, Germany. I was the navigator and the clear, sunny weather made that job easy, but it also was bad as it provided no cloud cover for our planes. We encountered some light flak at the coast, but everything went fairly well until noon. As we were approaching the IP about 100 FW-190 and ME-109 German fighters hit us. All eight aircraft remaining in the G Squadron and one from A Squadron were shot down.

We were shot down on the first pass. The 20mm shells were exploding in front of the plane and when they hit us we were really knocked around. The plane started spinning and Ross Hanneke called on the intercom, “Bail out! I can’t hold her!” I was wearing my flak vest over my parachute harness so I pulled the quick release on the flak vest. The release worked, but the front half of the vest was hanging from my oxygen mask as I had clipped the oxygen hose to it. I pulled off the oxygen mask and grabbed for the chest chute pack laying by my feet. Instead of the carrying handle I got the rip cord handle and opened the chute in the plane! With no choice, I gathered the chute up and managed to snap it to the harness. Fred Getz, the bombardier, was near me, chute on and ready to bail out.

The next thing I remember I was on the snow-covered ground. I had a bloody nose, a contusion of my right knee, no gloves, no flying boots or heated inserts and most of the wires were pulled out of the right leg of my heated suit. There was airplane wreckage in the field about 1/4 mile from me, large chunks of aluminum but no definite part I could recognize. The German Home Guards, wearing arm bands and carrying shotguns, were approaching. I believe the plane had exploded and I had been knocked unconscious. The open parachute must have pulled me out of the nose section at some fairly low altitude, as I did not have frozen fingers or toes. The temperature was about minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit at the 29,000 ft. altitude where we encountered the fighters, and well below freezing at ground level. When hit we still had our bomb load and a large amount of gas. I know we were hit many times on their initial pass and I assume the German fighters continued the attack until something drastic happened. It’s hard to believe no one else survived of our 10 man crew unless the plane had exploded.

The home guards ordered me to carry my parachute to a farm house near-by and sit on the parachute to await the military authorities. I had a “Mae West” life vest on and decided to see if the CO2 cylinders worked. Only one side inflated but that scared the German Guards as they thought I was going to blow myself up. Later a German looked me over, took out his pocket knife, grabbed my wrist, then cut the cloth band on my wristwatch. It was about this point I found I still had my 45 automatic in the shoulder holster, and I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t speak German and the guards didn’t speak English. When I tried to talk they indicated that I should just sit still and be quiet, that someone was going for an interpreter. The interpreter finally arrived and I stood up to tell him I still had my pistol. “Pistol” they all understood and it really upset them. The interpreter took the pistol and cut the holster harness to remove it, but it wouldn’t pull off as the bottom was snapped around my belt. After several jerks I managed to have him allow me to open my coat and unsnap the holster. If they were trying to impress me with their sharp knives, it worked, but I expected them to shoot me anyway.

An hour or so later a German Air Force enlisted man came along on his bicycle. He had me walk to another farm house where he searched me and made a list of all my belongings. At this farm I met two other U.S. airmen. One had a bad leg wound while the other was uninjured. At dusk we were told to climb onto a horse drawn wagon which I believed to be loaded with parachutes, coats, and other items of Air Force issue. We rode for some time and were told to unload the wagon. It was then I discovered the equipment on which we were riding was covering the bodies of eight or nine dead airmen. I didn’t recognize any of the dead, but they must have been from our Group. The two of us lined the bodies up in the garage area and the guards then put us in separate jail cells and gave us ersatz coffee and black bread. I hadn’t eaten since breakfast, and I was hungry, but just couldn’t eat that hard, sour, black bread. The coffee was almost as bad. However, after a few days that black bread ranked almost at the angel food cake level!

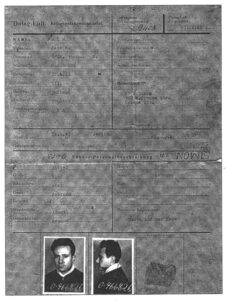

The next day we were taken to Berlin by train and by double-decker bus to the German Airport (probably Tempelhof). The wounded man was kept in the hospital there. I was given first aid and held in the air raid shelter area with the other flyer. The next day we were taken on a 17 hour passenger train trip to Frankfurt-on-the-Main for interrogation. There I was placed in solitary confinement in a small cell with one little, very high, barred window. We were not allowed to talk to anyone except the interrogator. Our cells had a “flag” arrangement to signal the guards that we had to use the toilet. They wouldn’t talk to us and made since no one else was in the toilet area when we were allowed its use. The food was very meager. The interrogator insisted that I was a spy because no one else had reported me as a crew member. They knew more about our base than I did! Even used our “secret and confidential” code number, 153, to identify the base. They knew most of the permanent personnel as well as all the Squadron Flight Leaders. Alter 10 days and several rounds with the interrogator they decided I didn’t know much and shipped me out with about 200 other P.O.W.s being transferred to Luft I Camp at Barth.

We were loaded into boxcars and I thought we “had it made” with about 50 men in each car, but then the guards took over the center third of the car. We were so crowded that we had to take turns lying down. The trip was to take five days but on the fifth day we reached Berlin in time for the nightly air raid. The British did a fine job of bombing Berlin every night for the five nights we were there. When the air raid sirens sounded the guards would head for the shelter leaving us locked in the cars. It is very scary when bombs are exploding all around and you know you are in one of the target areas. We could see the parachute flares used by the Royal Air Force to mark targets for the following planes to drop their bombs. The marshalling yards suffered a great deal of damage but none of our boxcars were hit. Some of the prisoners developed fever. We had exhausted the food supply by the time we reached Berlin, so the authorities finally decided to forget Barth and take us to Stalag III A at Luckenwalde about 30 miles to the south. A day or two after arriving there we watched the 8th AF hit Berlin. We were thankful to be out of Berlin but envious of those crews that would be back in England in a few hours.

A few hungry, cold, bed bug bitten months later we were liberated by the Russians but still confined to the camp. The Russians talked about taking us back through Russia to Odessa. The Germans strafed us a few times, so when we heard the Americans and Russians had linked up at the Elbe River, only fifty miles away, five of us decided to try to walk there. It took three days and was rather difficult but we all made it to the American Troops. Two months later I still had big blisters on my feet.

A few weeks later we were on a Victory ship, the Marine Dragon, headed for Boston and home. As mess officer on the trip back I managed to put on lots of weight. It’s a wonder we didn’t run out of food!

Melvin Johnson was a member of the Emory Hanneke crew aboard B-17G 43-38665 FC * Z, otherwise known as “Queen of the Skies“. According to Luftgaukommando Report KU 3575 and MACR 11723 (which of course includes translations of KU 3575), the bomber crashed 40 kilometers southwest or west of Neuruppin, at Bartschendorf. As indicated in Johnson’s account, he was the crew’s sole survivor.

This set of Oogle maps show the approximate crash location of Queen of the Skies, based on Luftgaukommando Report KU 3570.

First, a “close-up” centered on Bartschendorf…

…and the crash site, relative to Friesack, Neuruppin, and Berlin.

The picture of Queen of the Skies is American Air Museum in Britain photo UPL 30452, contributed by Lucy May.

This image of the Hanneke crew is via Lenny Andrews, nephew of flight engineer Leonard E. Andrews. As captioned, “Their Boeing B-17G Fortress went down approx 40km WestSouthWest of Neuruppin [at “Bartschendorf”], Germany. All crew (except Pilot Hanneke & Navigator Johnson), were reported dead at crash site by German Command at Neuruppin Air Base. Hanneke’s body was not recovered (at the time), and Melvin Johnson was captured as a POW. The bodies were buried in Common grave #1 of the Municipal Cemetery Bartschendorf, District of Ruppin southeast corner on 15 Jan 1945.” The photo caption also includes the men’s names, which are listed below. The names of their towns and cities of residence are via the next-of-kin roster in the Missing Air Crew Report.

Standing, left to right

Radio Operator – Gurbindo, Julian J. “Slim”, Sgt.

Fresno, Ca.

Golden Gate National Cemetery, San Bruno, Ca. – O, 0, 995

Gunner (Ball Turret) – Carlson, Harry Dean, Sgt., 19012859

Turlock, Ca.

Turlock Memorial Park, Turlock, Ca. – Lot 190 Block 20

Flight Engineer – Andrews, Leonard E., Sgt., 31299231

Attleboro, Ma.

Ardennes American Cemetery and Memorial, Neuville-en-Condroz, Belgium – Plot C Row 1 Grave 24

Spot Jammer – Miles, Eugene, Sgt., 18126764

Chicago, Il.

Ardennes American Cemetery and Memorial, Neuville-en-Condroz, Belgium – Plot A Row 41 Grave 30

Seated, left to right

Gunner (Tail) – Mosley, Walterine “Tex”, Sgt., 38629775

Burleson, Tx.

Ardennes American Cemetery and Memorial, Neuville-en-Condroz, Belgium – Plot A Row 32 Grave 36

Gunner (Waist) – Johnson, Eugene M., Sgt., 37524607

Picher, Ok.

Grand Army of the Republic Cemeter, Miami, Ok.

Co-Pilot – Kendall, Victor James, 2 Lt., 0-2062217

Kirkwood, Mo.

Mount Hope Cemetery, Webb City, Mo.

Pilot – Hanneke, Emory Ross, 2 Lt., 0-829011

Abbotsford, Mi.

Lakeside Cemetery, Port Huron, Mi.

Bombardier – Getz, Fred K., 2 Lt., 0-2068024

Lewisburg, Pa.

Ardennes American Cemetery and Memorial, Neuville-en-Condroz, Belgium – Plot A Row 41 Grave 44

Inset, upper left

Navigator – Johnson, Melvin L., 2 Lt., 0-2069029

Lagrange, In.

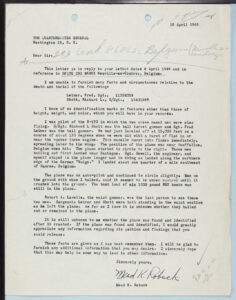

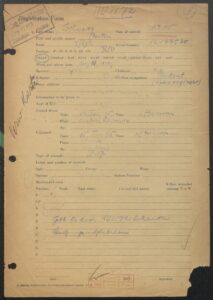

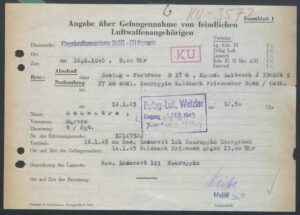

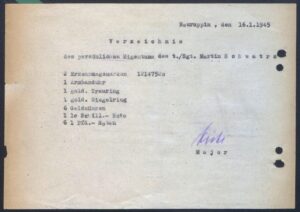

From Luftgaukommando Report KU 3575, this “Angabe über Gefangennahne von feindlichen Luftwaffenangehörigen” (“Information on the capture of enemy air force members”) form records Lt. Johnson’s capture by local gendarmes at the scene of his bomber’s crash, 35 kilometers west-southwest of Neuruppin. Interestingly, German investigators incorrectly identified Johnson’s bomber as 43-38337 “BI * N” / “Cloud Hopper” of the 568th Bomb Squadron, rather than the correct 43-38665 “FC * Z” / “Queen of the Skies” of the 571st.

______________________________

______________________________

Volume II

“Group Mission #243 – Derben Germany”

Rafael H. Galceran, Pilot, 569th Bomb Squadron

“…if this had been a milk run we sure as hell did not want to be on a rough one.”

IT was 25 December 1944, a cold wet afternoon when the British Railway train pulled into Ipswich Station to off-load its cargo of combat crews who were assigned to nearby groups of the 3rd Air Division by the replacement depot at Stone, England. A number of 2 1/2-ton G.I. trucks, canvas-topped and camouflage-painted, were lined up awaiting their passengers. A driver from the 390th Bomb Group called my name and crew number informing us that he would transport us to our new unit, the 569th Bomb Squadron. We loaded our gear, B-4 bags and baggage, in the back. My crew climbed in for the journey to Station 153 – Framlingham. It was raining lightly when we arrived and once again off-loaded our possessions in the front area near the Squadron orderly room and headquarters. We dutifully signed in on the unit roster. The C.Q. gave us our quarters assignment and directed us to the supply building where we would draw our bedding and a ration of coal. Since it was Christmas day, we thought that it was the reason that the area seemed deserted. However, we soon learned the 569th was participating that day on the mission to Morscheid Bridge, Germany, in an effort to slow the German forces in the Battle of the Bulge.

On the following morning the 390th had a stand-down so at 0800 hours my crew lined up to meet our new Squadron Commander, Lt. Colonel Joe P. Walters. A snappy salute, “Reporting as ordered sir!!”

The formalities over, we were placed at ease and our new leader then gave us a brief history of the unit and a lecture on what was to be expected of us. We learned that training never stopped, and that we would go through a short course of training in ground school and flight checks to demonstrate our ability to takeoff, fly formation, navigate a timed course, find the airfield, and land safely. This all had to be accomplished in-between the Squadron’s participation in almost daily bombing missions. On the next Squadron stand-down we had our check ride leading to certification as being combat ready on 10 January 1945. However, we still had to wait a few days for our first mission assignment. Lt. Colonel Walters explained this short delay as his desire for us to start with a “milk run” for our combat baptism. Thus it was that fate determined our first mission would be what was later described as one of the 390th’s greatest air battles.

At 0300 hours on 14 January 1945 the front door of our Nissen hut opened to allow a cold blast of air and the wake-up artist from the orderly room to rouse our crew. I was already seated on the edge of my bunk with my feet on the cold floor when he reached me in the front corner alcove. My eagerness of the days anticipated experience had made sleep virtually impossible. We dressed and, following the morning ablutions in a nearby building, we walked the few hundred feet to the combat mess hall. We were to discover that combat crews were served fresh eggs, any way you liked them, and real ham or bacon, potatoes, toast and coffee. This was a far cry from the powdered eggs and spam that was the fare on non-combat days and to the remainder of the personnel. (I would soon locate a private source of fresh eggs for those days that I was not scheduled to fly.) We then returned to the barracks to get into our flying clothing before hopping aboard a vehicle for the ride to the Group briefing room on the flight line. The briefing began with remarks by Col. Moller, our Group Commander. He informed us that even though Higher Headquarters considered this a low priority target, it was, none the less important in the overall strategy of the war to continue the interruption of any semblance of a steady flow of petroleum products to the German military machine. Derben was a synthetic oil refinery with many underground storage tanks. Again we mounted waiting vehicles of every description that delivered us to a hardstand where we found our assigned aircraft fully loaded and ready for pre-flight. Twelve blades were pulled through and then we climbed in to watch the tower for the green-green Very pistol flares to light up the sky. On this mission I would have 2nd Lt. Benny Meyers (later killed-in-action on another mission) as my co-pilot for his experience, and Bob Barritt would fly as the co-pilot with his crew. The signal to start engines soon came. The steady hum of 36 B-17s filled the early morning air. I often wondered what went through the minds of all of the nearby farm people whose buildings we would literally fly between on our taxi and take-off rolls. The noise must have been deafening. As our turn came, we taxied into the line of slow zig-zagging aircraft headed for the main runway. At the precise brief moment the Group Leader began his roll and one by one, at fifteen-second intervals, each of us roared down the runway lifting off and circling in a pattern to cut off the aircraft upon whose wing we would fly. We were in the number five spot, flying the right wing of the slot lead, and directly under the Squadron leader’s right wingman. The 569th was flying “B” Squadron, placing our 12 aircraft flight to the right, slightly higher and ever-so-slightly behind the Group Leader or “A” flight. “C” flight, the 568th, was slightly below the leader and the same distance behind as we were. All 36 aircraft of the 390th sported the tail insignia of a black “J” in a white square. We then joined the square “D” 100th and the square “B” 95th Bomb Groups thus forming the 13th Combat Wing of the 3rd Air Division of the 8th Air Force. This mission would have a total of 841 bombers in the battle fleet. I have been told that when the 8th Air Force put up a maximum effort this would amount to 1250 to 1300 bombers. When all were in battle line the bomber column covered a distance of 75 miles from lead aircraft to “tail-end charlie” and stretched 25 miles in width. Awesome, simply awesome.

The flight had been routine as briefed. We flew across the channel to Holland. We then turned right over occupied territory and headed generally towards Berlin. It was still a piece of cake, a “milk run”. Approximately 15 minutes short of the IP, the point we would turn onto the bombing run, the alarm came, “Bandits at 9 o’clock”. This was a group of about 75 Folke Wolff 190s and they engaged our friendly fighter escort who immediately dropped their tip tanks to engage in a great aerial dogfight. The enemy soon broke off and our fighters turned for home because without the extra gas, jettisoned in the tip tanks to improve their maneuverability, they could not stay with us until our next fighter escort arrived. Our fears turned to reality when we saw the second enemy wave attack our “C” Squadron whose leader had lost his turbo supercharger. They were now about 2000 feet below and to the rear of flights “A” and “B”. The eight or nine aircraft still in their formation were all quickly shot down. We watched helplessly as each left the sky and counted parachutes as best we could. “B” Flight was attacked by about 40 Me 109’s, coming in from the 4 o’clock position. We were now on the bomb run flying straight and level, no evasive action, so as not to interfere with the bombardier’s accuracy. I looked out the co-pilot’s window to see the silhouette of an Me 109 and could see what appeared to be a flashing light in the nose spinner. This meant only one thing, we were his target and we were seeing the muzzle flashes of each round of 20 mm cannon exiting the barrel of his gun. Those projectiles were headed straight for our ship. “God, they were attempting to shoot me down too.” The sequence of the ammo was: tracer-armor piercing, incendiary, then explosive, and this line fingered its way through the sky towards us. Then it hit. We could hear the rattle of the shrapnel bouncing around inside the plane like so much hail on the roof, and the chatter of our own 50 caliber machine guns firing in short bursts as he bore in on us. We then smelt the acrid smell of fire, something we dreaded most, coming from the aft section. An Me 109 passed about 150 yards below us where he exploded in a ball of fire. Our Ball Turret Gunner, Joe Lawless, had scored a hit (a confirmed kill). A second Me 109 crossed behind us trailing black smoke. We saw the German pilot bail out. This second kill was credited to our Tail Gunner, Jimmy Stewart. They also shared a “probable” during that terrible ten minutes.

As sudden and furious as it came, and though it seemed at the moment to be an eternity, the Germans abandoned their attack and turned north. They apparently saw a flight of P-51 Mustangs high on our left. Sergeant Vince Johnson, Radio Operator, early during the battle had called on the intercom to tell me that there were wounded in the rear, in the waist compartment. When the unmistakable lurch came from the release of our bomb load, I sent our Bombardier, Frank Zier, to the rear to assist and report concerning the damage and wounded. He soon returned with the news that all in the radio and aft section was under control. The following article by our gallant Radio Operator, Vince Johnson, provides his recollections of what was going on back in the radio room and waist section while we were on the bomb run.

We would learn later that an armor piercing shell had ricocheted off Sergeant Phillipson’s gun barrel nearly severing his right arm. The force knocked him to the floor of the waist section where Vince found him and re-connected his oxygen line. The same shell had cut the center support for the ball turret completely through requiring the Ball Turret Gunner, Joe Lawless, to evacuate that bubble. An incendiary had started the radio on fire, and an explosive had gone off in back and below Vince knocking him off his seat. He still, to this day, has pieces of shrapnel in his body. A parachute was popped to provide cover for Sgt. Phillipson after Lt. Zier had given him two vials of morphine for his pain. We did not know Sgt. Johnson was wounded until we were nearly home.

After we became stabilized in good steady formation, and the danger of attack remote, I turned the controls over to the Copilot and went aft to follow up on Lt. Zier’s report. I was satisfied that all had been done that could be until we were on the ground. It wasn’t until much later, in the barracks after de-briefing, that we discovered that Lt. Zier had received a sliver of shrapnel in a most unglamorous location of the derriere while he was seated over his Norden bomb-sight on the bomb run. His bloody shorts told the tale. We whisked him to the Dispensary for its removal while we laughed how he would tell his grandchildren where he was wounded.

The long flight home was eased somewhat by the fact that we had fighter escort, saw no flak nor enemy fighters. Upon our arrival near home base we were allowed to peel off from the formation for a straight-in approach. We fired our Very pistol red-red flares to indicate wounded aboard. This alerted the tower and ambulances. The propellers were still windmilling as the medics climbed in through the waist door to attach plasma bottles to Phil and Vince. This was the first we knew of the extent of injury suffered by our Radio Operator, a real gutsy guy. The stretchers were loaded into the ambulances and as they rolled off towards a nearby field hospital the remainder of the crew prayed not only for them but for ourselves as well, because if this had been a milk run we sure as hell did not want to be on a rough one.

______________________________

“Group Mission #243 — Derben Germany”

Vincent K. Johnson, Radio Operator, 569th Bomb Squadron

“It wasn’t long before they detected I had been wounded

and only the “Good Lord” knows the element of pain in those ensuing hours.”

I was a youngster of nineteen and now about to “lift off in the Wild Blue Yonder” with the “family,” known as the crew, that I had trained with to qualify for this difficult task. The assembly of all the crews and the dispatching of the individual crafts were enough to make this youngster agog of the “might” of this Air Force that he was a part of. What a scene to see all those crafts taking off and then assembling in their respective places within the formation before then pointing toward the given target.

Being the Radio Operator I had certain responsibilities, even in the face of all this mass movement, to convey communications to the pilot, navigator, or whatever communications dealt with our little “family”. Now that this was the “real” thing the communications were primarily directed to the pilot or pilot to radio operator if he needed information. I mention these responsibilities because it seemed like the things that happened within the plane were the priority items. Happenings outside the plane were another world.

Before reaching the target on 14 January 1945, radio silence was declared and, therefore, I, at my radio seat, was gazing into “that other world” on the outside of the plane. We were still approaching the target when little-by-little the “flak” and the enemy fighters became more prominent in that outside world. Even then in one’s young mind he doesn’t comprehend the dangers on the outside, as long as “our family” was OK inside the plane.

Suddenly, and one cannot describe it in terms of time, that outside world was inside our plane, “our home”. While at my radio chair and turned toward the table, my body just exploded, stunned, and in pain. I found myself on my hands and knees in the radio room, my oxygen mask off and the radio chair still facing the table. The mission was at about 29,000 feet so the first instinct was to replenish my system with oxygen. Then I realized we had another member of our family and He was the Man way upstairs. I say this because something told me to check visibly before calling in, and sure enough in the waist was Phil, one of “the family”, bloody and laying on his back with no oxygen. After some shifting and adjusting I was able to get him oxygenized so that he was back in the real world. We got back to the radio room and I then originated a call to the pilot that we had a wounded person aboard. Why I wasn’t able to admit that I had also been hit must have been fear that maybe I didn’t do the job and I would lose my place in “the family”. It wasn’t long before they detected I had been wounded and only the “Good Lord” knows the element of pain in those ensuing hours. Certainly the crew was aware of it and majestically tried everything to comfort Phil and I on the flight home.

During one year and two days, and many, many operations, in the hospital, I frequently told hospital personnel and other patients about our “little family”. Certainly it was a structure and an adventure in one’s life. Of those that served in World War II, the ones who had the privilege of being part of the crew of a mighty B-17 had to be the lucky guys. I always felt close to those who were part of our little unit and I think we were all so very proud to say “our plane”.

Based on the 390th Memorial Museum database, the Galceran crew flew aboard B-17G 43-38663, CC * M / “The Great McGinty” on this mission. According to B-17 Flying Fortress.de, the aircraft survived the war and was returned to the United States on June 30, 1945. It was sold for scrap metal, and presumably reduced to pots and pans, aluminum siding, etc., on December 8 of that year.

This image of the Galceran crew is via the 390th Memorial Museum. Crewmens’ names are listed below the photo.

Standing, left to right

Flight Engineer – Kidwell, Gordon W.

Radio Operator – Johnson, Vincent K. (3/15/25-11/15/95)

Gunner (Waist) – Phillipson, Emmett D.

Gunner (Ball Turret) – Lawless, Joseph P.

Gunner (Waist) – Kunz, M.

Gunner (Tail) – Stewart, James H.

Crouching, left to right

Pilot – Galceran, Rafael Hipple, Jr. (5/21/21-11/3/92)

Co-Pilot – Barritt, Robert E.

Navigator – Wooten, John D.

Bombardier – Zier, Frank M., Jr. (9/15/19-7/10/05?)

________________________________________

References, to Keep You Busy (and Happily Distracted!?)

Books

Astor, Gerald, The Mighty Eighth: The Air War in Europe as Told by the Men Who Fought It, Dell Publishing, New York, N.Y., 1997

Freeman, Roger A., The Mighty Eighth – A History of the U.S. 8th Army Air Force, Doubleday and Company, Inc., New York, N.Y., 1970

Freeman, Roger A., The B-17 Flying Fortress Story – Design – Production – History, Arms & Armour Press, London, England, 1998

Milliken, Albert E. (editor), The Story of the 390th Bombardment Group (H), N.Y., 1947

Richarz, Wilbert H., Perry, Richard H., and Robinson, William J., The 390th Bomb Group Anthology – Volume I, 390th Memorial Museum Foundation Inc., P.O. Box 15087, Tuscon, Az., 1983

Richarz, Wilbert H., Perry, Richard H., and Robinson, William J., The 390th Bomb Group Anthology – Volume II, 390th Memorial Museum Foundation Inc., P.O. Box 15087, Tuscon, Az., 1985

Websites

Wayne’s Journal – A life of a B-25 tail gunner with the 42nd Bombardment Group in the South Pacific – January 14, 1945

WW2Aircraft.net – Details of air battles over the West on January 14, 1945 (Primary emphasis on encounter between fighter aircraft of Eighth Air Force and Luftwaffe)

WW II Aircraft Performance – Encounter Reports of P-51 Mustang Pilots (Includes reports for January 14, 1945)

Tempest V Performance – Combat Reports (Includes four Reports for January 14, 1945)

390th Memorial Museum Foundation – Database (390th Memorial Museum’s Research Portal)

-and-

390th Bomb Group Works Cited

The Story of the 390th Bombardment Group (Paducah: Turner Publishing Company, 1947), 65-66.

“390th Bomb Group: History of Aircraft Assigned.” Unpublished manuscript. 390th Memorial Museum. Joseph A. Moller Library.

“390th Bomb Group Tower Log: November 22, 1944 – June 27, 1945.” Unpublished manuscript. 390th Memorial Museum. Joseph A. Moller Library.

“Mission – No. 243, Target – Derben, Germany, Date – 14 January 1945.” Mission Reports Part I, MISSION_REPORTS_03, file no. 1266-1267. Digital Repositories. 390th Memorial Museum. Joseph A. Moller Library.