Whether in war or peace, the nature of man has many facets, which, depending on the circumstance and time, can vary as much within the soul of one person as between different individuals: Courage. Fear. Deliberation. Rashness. Boldness. Hesitation. Judgement. Foolhardiness. Discernment. Obtuseness. Bravery. Cowardice. Cunning. Naivete. And so much more.

One way in which these aspects of the human character have been chronicled, whether in fiction, popular culture, or the “historical record”, is in accounts of the escape from captivity of prisoners of war. Whether described in official documents, letters and diaries, family stories, legends, passing anecdotes, or the unexpressed memories of men, there are innumerable such tales. One such account – of very many – from the Second World War, appeared as a three-part series in the New York-published German exile newspaper Aufbau – “Reconstruction” – on October 15, 22, and 29, 1943, under the simple and apropos title “Ich war ein Kriegsgefangener der Nazis” – “I Was a Prisoner of War of the Nazis”.

Written by an un-named Yishuv soldier who escaped from German captivity (the events of the story having transpired in German-occupied Greece) the series commences with the soldier’s interrogation by German officers, continues with fleeting recollections of his life as a POW (always with escape and defiance in mind), follows with accounts of thwarted escape attempts, and concludes with the soldier’s first encounter – while “on the run” after his eventual, successful escape – with Greek civilians.

In terms of the soldier’s escape attempts, the first attempt – well, contemplated escape attempt! – would have involved the author and his friend “Sch.” jumping from a moving freight car during a moonlit night. This plan was aborted at the last moment when rifle fire was heard and a guard entered the car, after which the author and Sch. seem to have been reproached other POWs for jeopardizing the well-being of their comrades. However, during the next train stop, a POW from the adjacent freight car did escape: That man momentarily distracted a guard with the light of a match, and then concealed himself by lying between the rails and allowing the cards to pass over him.

Subsequently, another escape was planned, again involving a night-time train jump by the author and Sch. This was aborted when Sch. pulled the author back into the train, after the author had been “noticed” (again?) … by other POWs?

The second escape attempt occurred as a group of POWs were marching through the pass of Thermopylae: The narrator and Sch. jumped into a nearby ditch during a moment when the column of POWs was temporarily unguarded. Their immediate escape occurred unnoticed, but the uncoordinated, spontaneous “escapes” of other POWs attracted the attention of a lieutenant and some guards. Before the arrival of these German soldiers, Sch. and the author managed – unnoticed – to rejoin the main column of POWs. The other “random” escapees were returned to the POW column to the accompaniment of rifle butts. Tellingly, two escapees never returned.

So, the third time was the charm.

After leaving Thermopylae the POWs were again loaded onto freight cars. At night, alone – Sch. having no further interest or motivation in escaping – the narrator jumped from a moving freight car as the train passed over a bridge. Pursued by rifle fire, he reached the bridge’s railing, and – taking very much of a leap of faith – fell into a stream or river, remaining underwater. Upon reaching the limit of his endurance, unable to hold his breath any longer, he rose to the surface of the water and saw that he had been left behind: The train has crossed the bridge, without him.

He was a free man.

The tale is well-written, compelling, and inspiring, yet also (deliberately?!) enigmatic, for absolutely nothing is revealed about the soldier’s experiences prior to his capture, let alone the events surrounding his post-escape evasion and eventual return to Allied forces – which together almost certainly encompassed a time period vastly longer than the brief duration of his actual captivity. Though I’m certain information about each and every aspect of his escape was recorded, corroborated, and archivally preserved by the British military (and probably still exists somewhere – where?! – within The National Archives (not the National Archives!)) for security reasons, this information obviously could never have been released to the news media in wartime. This, the tale’s “truncated” nature and abrupt end, at least in a literary sense.

Despite the story’s gripping nature and its direct relevance to the nature of the Jewish military service during the Second World War (well, at least in the European Theater…), to the best of my knowledge nothing relating to the tale appeared in any other wartime Jewish periodical. This was probably attributable to lack of awareness on the part of publishers and editors of other English-language organs of the Jewish news media (whether in the United States, England, South Africa, the Yishuv, or elsewhere) to the very venue of the article’s publication – Aufbau, let alone the article having been published in German.

One of the most interesting aspects of the story is apparent from its first installment: The author’s identity is a mystery; neither his rank nor his name are given. His identity is only resolved – and at that, partially resolved – in the third and final part of the series. However, a general idea of his background can be gained from these clues: 1) Quoting from the introduction to the first installment: “The author of the following diary pages fled as a very young man from Nazi Germany to Palestine and became a member of kvutzah [kibbutz]”. 2) The soldier (and three fellow POWs, “S. and D. and R.”) hailed from the kvutzah of Ashdoth-Ya’akov, now known as Kibbutz Ashdot Yaakov (Ihud); just south of Lake Tiberias. 3) He was born in Germany and graduated from high school there, his parents (…alas, alas…) remaining in that country as of the summer of 1941. 4) He was living in Haifa through 1938.

____________________

This Mapple App Apple Map shows the location of Kibbutz Ashdot Yaakov: Designated by the red pointer, it’s just south of Lake Tiberias.

____________________

So, who was this anonymous author? If you scroll to the very end of this post, you’ll see that the series’ final installment (unlike the first and second installments) published on October 29, 1943, concludes with the initials: “F. J-n.” Though – perhaps deliberately? – not an exact match, I am confident that these initials refer to Private Y.M. El-Jo’an (serial number PAL/12083), who was reported in The Palestine Post of August 15, 1943, as having escaped from German captivity. The time-frame of Aufbau’s series fits the August 15 news item perfectly, strongly implying that El-Jo’an evaded (certainly with the assistance of Greek civilians?) for over a remarkable two years, given that the fall of mainland Greece to German forces occurred at the end of April, 1941.

____________________

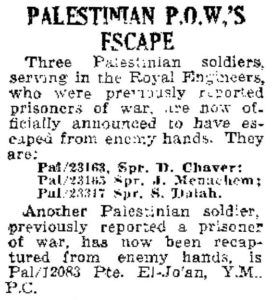

Here’s the Post’s front page for August 15, 1943, with the article highlighted…

…and, here’s the brief article itself:

PALESTINIAN P.O.W.’S

ESCAPE

Three Palestinian soldiers, serving in the Royal Fusiliers, who were previously reported prisoners of war, are now officially announced to have escaped from enemy hands. They are:

Pal/23163, Spr. D. Chaver;

Pal/23183, Spr. J. Menachem;

Pal/23317, Spr. S. Dalah.

Another Palestinian soldier previously reported a prisoner of war, has now been recaptured from enemy hands, is Pal/12083 Pte. El-Jo’an, Y.M., P.C.

____________________

So, assuming “F. J-n.” was in reality Private Y.M. El-Jo’an – as I’m confident he was – I have absolutely no idea of what became of him afterwards. Paralleling this, I have no information about Sappers Chaver, Menchem, or Dalah. Perhaps they, too, evaded or escaped from captivity in Greece. I’m certain their stories would be as compelling as that of Private El-Jo’an, if they could be found.

________________________________________

____________________________________________________________

________________________________________

Of the forty-five Yishuv soldiers captured by the Germans who did not return from or eventually survive captivity, there were thirteen men who attempted to escape, but did not succeed. They were:

Disappeared after escaping

Private Menashe Durani: 9/5/41 – jumped from train

Died while evading capture

Private Abraham Gelbart: 4/25/42

Shot or killed during escape attempt

Sapper Aharon Arman: 1/26/45

Corporal Michael-Chaim Brajer: 1/16/45 or 1/26/45

Sapper Abraham Elimelech: 7/19/41

Private Norbert Gabriel: 11/1/41

Sergeant Itzchak Goldman: 4/29/41

Private Saadia Tzabari: 4/28/41 – jumped from train

Corporal Shlomo Tzarfati: 10/1/41

Private Jakub Weissberg: 10/30/42

L/Cpl. Aaron Weissman: 8/19/41

Escaped; apprehended 5/17/44, but shot shortly after recapture

Private Dov-Berl Eisenberg – died of wounds 6/28/44

Private Eliahu Krauze – died immediately

Of these thirteen soldiers, some of their stories are partially known; some are barely known; and some will never be known. (Well, among men.)

Very brief biographical profiles of these soldiers are presented below, based on information in both volumes of Henry Morris’ invaluable two-volume work We Will Remember Them, random issues of The Jewish Chronicle and The Palestine Post, plus, information available via the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, and, Izkor, The Commemoration Site of The Fallen of the Defense and Security Forces of Israel, where their portraits were found.

Note that eight of the thirteen have no known graves.

And so, they are…

– .ת. נ. צ. ב. ה –

תהא

נפשו

צרורה

בצרור

החיים

Arman, Aharon (אהרון ארמן), Sapper, PAL/23378, Royal Engineers

1039th Port Operating Company

Stalag 344 Lamsdorf

1/26/45: Shot during escape attempt

Born 1921

Mr. and Mrs. Nathan [Natan] and Miriam Arman (parents), Tel Aviv, Israel

Krakow Rakowicki Cemetery, Poland – 2A,C,6

We Will Remember Them II – 42

German POW # 4784; Year of birth: CWGC 1926; izkor.gov.il: 1921

____________________

Brajer, Michael Chaim [Chaim-Michail] (חיים-מיכאל ברייר), Cpl., PAL/23009, Royal Engineers

1039th Port Operating Company

Stalag 8B Teschen

1/16/45 or 1/26/45: Killed while fleeing POW camp

Born Kandesh, Hungary, 9/2/13

Mrs. Malja Brajer (wife), Tel Aviv, Israel

Mr. Batseva [Bat-Sheva] Brajer (father)

Athens Memorial, Athens, Greece – Face 4

The Jewish Chronicle 7/25/41

We Will Remember Them I – 239

German POW # 4334; POW List as “Breyer, Michail Chain”; LJC gives name as “M.C. Breyer”, and rank as “Sapper”; CWGC and Izkor.gov.il. dates differ.

____________________

Durani, Menashe (מנשה דורני), Pvt., PAL/13216

603rd Palestinian Port Company

Stalag 344 Lamsdorf

9/5/41: Jumped off train during transfer of POWs to Austria, and disappeared

Born Peta Tikva, Israel, 1918

Mr. and Mrs. Yosef and Shvedia Durani (parents), Raanana, Israel

Athens Memorial, Athens, Greece – Face 9

The Jewish Chronicle 7/25/41

German POW # 4869

____________________

Eisenberg, Dov [Dov-Berl] (דב-ברל אייזנברג), Pvt., PAL/11797, Mentioned in Despatches

Pioneer Corps

POW in Poland

5/17/44: Escaped

Died while POW 6/28/44 (murdered)

“All the days of his captivity Dov did not fall in his spirit, he tried to escape from his captivity, and at the first opportunity he escaped with a friend and the two hid in secret. Squads of German soldiers set out in search of them and later captured them and led them back to the camp. On the way to the camp, they met a German officer who ordered them to come with him to look for another escaped prisoner. As they walked in front of the officer, [?] pulled out a gun and shot them in the back. Dov’s friend was killed on the spot and Dov was fatally wounded. A [?] asked the Germans to take him to Bloomsdorf Hospital, but they did not comply with his request and brought him to a military camp. On 6/28/44, Dov died of his wounds. He was laid to rest in the British Military Cemetery in Krakow, Poland.”

Born Lodz, Poland, 2/24/21

Mr. and Mrs. Haim and Hava Eisenberg (parents)

Crackow Rakowicki Cemetery, Crackow, Poland – 4,A,9

We Will Remember Them I – 242; We Will Remember Them II – 65

We Will Remember Them I as “Eisenberg, Dov”; CWGC as “Eisenberg, Berl”; Izkor.gov.il as “Dov-Berl Eisenberger”

____________________

Elimelech, Abraham (אברהם אלימלך אל-מלך), Sapper, PAL/23170, Royal Engineers

1039th Port Operating Company

POW in Greece

7/19/41: Wounded and killed while attempting to escape

Born Komotini, Greece, 1915

Mr. Hajim [Haim] and Roza Elimelech (parents), Tel Aviv, Israel

Athens Memorial, Athens, Greece – Face 4

The Jewish Chronicle 7/25/41

We Will Remember Them I – 242

____________________

Gabriel, Norbert [Norbert-Nahum] (נוברט-נחום גבריאל), Pvt., PAL/11574

Palestine Regiment

POW in Greece

11/1/41: Killed while attempting to escape

Born Moglanice, Poland, 5/2/03

Mr. and Mrs. Yaakov and Ernestina Gabriel (parents)

Phaleron War Cemetery, Greece – 12,B,11

The Palestine Post 8/19/41

We Will Remember Them I – 244

We Will Remember Them I as “Gavriel, Norbert”; CWGC as “Gabriel, Norbert”; Name not present in Prisoners of War – Allies and Other Forces of the British Empire

____________________

Gelbart, Avraham [Avraham-Yitzhak] (אברהם-יצחק גלברט), Pvt., PAL/13746

Pioneer Corps

POW in Greece

4/25/42: Died during escape attempt

“Following his service, his unit was transferred to the Kalamata Peninsula in Greece, where he was taken prisoner. They were put on a train and on their way from Athens to Thessaloniki, when slowing down from journey in the mountains Abraham took advantage of the darkness and jumped out. After a few days of wandering in the mountains he arrived at one of the villages where he was warmly received by the residents and also given shelter in an attic room. Stayed with them for about two years, working as a shoemaker and liked all the people of the village. One day, after learning that a patrol of Italian and German soldiers was approaching the village for search purposes, Avraham fled to the forests and took an old shotgun with him. While in the woods a bullet was fired from his rifle and he was wounded in the leg. A few days later, he returned to the village, but in the meantime he lost a lot of blood and developed necrosis in his leg. He died, and was buried in the Christian cemetery in the village. It was written on the monument that he was not afraid of the Germans. In 1945, his body was in the main military cemetery near Athens where he was buried as an unknown soldier. In 1961, when it was clarified beyond any doubt that this was indeed Abraham’s grave; a ceremony was held there. A new monument was erected with a Star of David and an inscription in Hebrew, stating, among other things: “From the depths of the past, you have returned to the bosom of faith that has been restored.””

Born Germany, 5/8/12

Mrs. Penira Gelbart (wife), Herzlia, Israel

Mr. and Mrs. Shlomo and Hana Gelbart (parents)

Phaleron War Cemetery, Greece – 3,C,15

The Jewish Chronicle 10/19/45

We Will Remember Them I – 244

We Will Remember Them I as “Gelbart, Avraham”; CWGC as “Gelbart, Abraham”; Year of birth: CWCGC 1902; izkor.gov.il: 5/8/12

____________________

Goldman, Itzchak [Icchaak] (יצחק גולדמן), Sgt., PAL/10889

Pioneer Corps

POW in Greece

4/29/41: Killed while attempting to escape

Born Yaroslavl, Poland

Mr. Shmuel Goldman (father)

Athens Memorial, Athens, Greece – Face 9

We Will Remember Them I – 244

We Will Remember Them I as “Goldman, Y”; CWGC as “Goldman, Icchaak”; Yad Vashem Studies XIV, p. 90

____________________

Krauze, Eliahu (אליהו קראוזה), Pvt., PAL/11786, Mentioned in Despatches

Pioneer Corps

POW in Poland

5/17/44: Murdered

“On the first day of his internment in the POW camp he began to look for a way to escape and return to the front. After three years in a POW camp in Buiten, Germany, he came to terms with a captive friend, Dov Eisenberg. On 5/17/44 they tried to escape but were immediately captured and returned to the camp. One of the Nazi sergeants ordered them to accompany him on the pretext of searching for a third captive who had disappeared and in the field shot them from behind. Dov was seriously injured and Eliyahu was killed on the spot. He was laid to rest in the British Military Cemetery in Krakow, Poland.”

Born Lodz, Poland, 1920

Mr. and Mrs. Gronem [Gronam] and Frida Krauze (parents)

Mr. Abram Feldman (uncle), Bnai Brak, Israel

Krakow Rakowicki Cemetery, Poland – 4,A,5

We Will Remember Them I – 249

____________________

Tzabari [Zabary], Saadia [Shlomo] (סעדיה צברי), Pvt., PAL/13145

Pioneer Corps

POW in Greece

4/28/41: Jumped off train during transfer to Germany via Yugoslavia; spotted and killed by German guards

Born Sanaa, Yemen, 1925

Mr. and Mrs. Seadya and Zehava Tzabari (parents)

Athens Memorial, Athens, Greece – Face 9

We Will Remember Them I – 260

We Will Remember Them I as “Tzabari, Saadia”; CWGC as “Zabary, Saadia”

____________________

Tzarfati [Zorfati], Shlomo (שלמה צרפתי), Cpl. PAL/23152, Royal Engineers

1039th Port Operating Company

POW in Greece

10/1/41: Killed while attempting to escape

Born Thessalonika, Greece, 1916

Mrs. Sarah Zorfati (wife), Tel Aviv, Israel

Mr. and Mrs. Aron [Aharon] and Bienvenida [Benvenida] Zorfati (parents)

Athens Memorial, Athens, Greece – Face 4

We Will Remember Them I – 260

We Will Remember Them I as “Tzarfati, Shlomo”; CWGC as “Zorfati, Shlomo”

______________

Weissberg [Waisberg], Jakub [Jacob] (יעקב ויסברג), Pvt., PAL/00890

Pioneer Corps

POW in Greece

10/30/42: Killed while attempting to escape

Born Poland, 1903

Mr. Adolf Weissberg (father)

Athens Memorial, Athens, Greece – Face 9

We Will Remember Them I – 261

We Will Remember Them I as “Weissberg, Y”; CWGC as “Waisberg, Jakub”

______________

Weissman, Aaron [Aron] (אהרון וייסמן), L/Cpl., PAL/23026, Royal Engineers

1039th Port Operating Company

Stalag 8B Teschen

8/19/41: Killed while attempting to escape

Born Bucharest, Rumania, 1/1/14

Mr. and Mrs. Itzhak David and Feige Weissman (parents), Tel-Aviv, Israel

Athens Memorial, Athens, Greece – Face 4

We Will Remember Them I – 274

German POW # 4875; POW List as “Weisman, A.”

________________________________________

____________________________________________________________

________________________________________

So, here are all three parts of “F. J-n.” / Private Y.M. El-Jo’an’s story as published in Aufbau. Transcribed verbatim and presented in chronological order, each segment is followed by an English-language translation. Note that the first installment of the series is given a prominent “above the fold” presentation, but the last two parts are allocated to the newspaper’s last page.

Ich war ein Kriegsgefangener der Nazis

October 15, 1943

Der Verfasser der folgenden Tagebuch blätter floh als ganz junger Mensch aus Hitler-Deutschland nach Palästina und wurde dort Mitglied einer Kwuzah. Bei Ausbruch des Krieges trat er als Freiwilliger in die britische Armee ein, in der er jetzt einen hohen Offiziersrang bekleidet. Während der Kämpfe in Griechenland geriet er in Nazi-Gefangenschaft, aus der er sich nach kurzer Zeit befreien konnte. Die Schilderung dieser Gefangenschaft und Flucht ist nicht allein als individuelles Schicksal interessant, sondern sie gibt auch Aufschluss über die Art, wie aus Deutschland stammende jüdische Soldaten der alliierten Armeen behandelt werden, wenn sie in Nazi-Gefangenschaft geraten.

Ende Mai war es, als man uns — endlich! — zum Verhör auf die Kommandantur brachte. In der Zwischenzeit hatte die Gestapo alle Dokumente, die sie über uns ehemalige deutsche Juden hatte, herbeigeschafft. Gemäss internationalen Recht sollte uns genau die gleiche Behandlung wie den britischen Gefangenen zuteil werden; dieses Recht wurde in der Weise umgangen, dass versucht wurde, uns nachzuweisen, dass wir uns in Deutschland vor der Flucht irgendwelcher Vergehen schuldig gemacht hatten. Einer der Gefangenen wurde unter Sonderarrest gesetzt, weil in den Gestapo-Akten verzeichnet war, dass er beim Verlassen Deutschlands die letzte Rate für eine gekaufte Schreibmaschine geblieben war. Dies ist ein Beispiel.

Mein Name wird aufgerufen. Ich trete in das Zimmer des Lagerkommandanten und salutiere. Er erwidert den Salut. Die strengen Blicke dreier deutscher Offiziere richten sich auf mich. Just in diesem Augenblick gewinne ich meine ganze Sicherheit wieder: Was kann mir schon Schlimmeres passieren, als dass man mich erschiesst! So muss man mit Deutschen reden.

‘‘Sie haben Eltern in Deutschland?” fragt der Kommandant scharf, ja drohend.

“Ja”, antworte ich ruhig.

“Sie haben ein deutsches Gymnasium absolviert?”

“Ja.”

“Sie kennen Deutschland?”

“Gewiss.”

“1938 hat der deutsche Konsul in Haifa Sie aufgefordert, sich zum Armeedienst zu stellen; wie kommt es, dass Sie als Freiwilliger in der britischen Armee gegen Deutschland gekämpft haben?”

“Weil Deutschland unser Feind ist; ich hasse meinen Feind!”

Wider Erwarten erhob sich der Offizier vom Stuhl, trat auf mich zu und klopfte mir auf die Schulter: “Sehr gut!”

Ich gestehe: aus mir sprach nicht allein verzweifelter Mut, sondern auch Erfahrung. Ich wusste bereits, dass diese Frage uns allen gestellt wird, und dass es das Beste sei, kurz angebunden und wahrhaft zu sein. Einige jüdische Soldaten aus Palästina hatten geantwortet, sie seien in die Armee eingetreten, weil sie arbeitslos waren. Sofort flogen sie zur Tür hinaus, wurden dort von der Wache mit Fusstritten behandelt und weiter befördert. Das gleiche passierte einem jüdischen Offizier, der in England der Armee beigetreten war. Er hatte die Frage mit “Konskription” beantwortet. Er flog alle Treppen hinunter und musste vom Platz getragen werden. Drei meiner Kameraden aus Ashdoth-Jaacov (Name einer Kwuzah in Palästina. D. Uebers.) S. und D. und R. gaben die gleiche Antwort wie ich und kamen glimpflich davon. Ich wurde also nicht hinausgeschmissen, sondern verlies erhobenen Hauptes das Kommandanturzimmer.

Vor dem Abtransport ins Reich

Wir hungerten sehr. Je zwölf von uns erhielten einen Laib Brot. Täglich wurden Tausend von uns aus dem Lager wegtransportiert. Unser Brigadier Plenigton liess uns, bevor man ihn wegtransportierte, den folgenden Befehl zugehen:

“Soldaten der britischen Armee, Australier und Neuseeländer! Euer Schicksal hat es gewollt, dass Ihr in Gefangenschaft geraten seid — für Kriegsdauer. Der Feind war uns an Zahl überlegen. Ihr werdet nun Deutschland mit eigenen Augen zu sehen bekommen. Vielleicht wird Euch vieles dort gefallen; doch hütet Euch vor jeder Beeinflussung. Es sind Gerüchte in Umlauf, dass am Ufer von Corinth unsere Unterseeboote warten, um flüchtige Gefangene aufzunehmen. Ich halte das für ausgeschlossen. Unser Schicksal ist besiegelt. Gefangenschaft.”

Die letzten Tausend zu denen auch ich gehörte, wurden am 9 Juni abtransportiert. Ich hatte wieder einen bösen Malaria-Anfall, und die Hitze war unerträglich. Nackt standen wir vor der Kommandantur. Unsere Kleider und Schuhe hatten wir zur Desinfektion abgeben müssen, jeder bekam einen Fetzen, wie ein Taschentuch gross, um seine Blösse zu bedeken. So schritten wir durch die Gässchen von Corinth zur See, um ein Reinigungsbad zu nehmen. Die Einwohner entsetzten sich, als sie diesen von bewaffneten Deutschen flankierten Zug der Nackten erblickten; sie stürmten, ständig sich bekreuzigend, in die Häuser. Wir aber vergassen, dass wir nackt waren: endlich aus der Baracke heraus und frei marschieren dürfen! Wir vergangen, dass wir bewacht wurden, stürzten in die Gemüsegärten, gruben mit den Fingern die Rüben und Gurken heraus und assen sie mit der Gartenerde. Endlich wieder sich den Magen füllen können, gleichgültig mit was! Schliesslich wurden wir von der aufgeregten Wache wieder zu einem Zug zusammengeprügelt und zum Strand gebracht. Dort wurden wir mit Karbol bespritzt, und die unbarmherzige Sonne briet unsere Haut. Doch als wir endlich in der See “frei” schwimmen durften, vergassen wir alle Not. Wir schrien vor Lust.

Auf dem Rückwege marterte uns wieder der Gedanke: Gefangenschaft. Wir blickten sehnsüchtig zum Meer zurück, das uns mit den Ufern Erez Israels verbindet. Und morgen geht’s nach Deutschland. Bei mir stand der Entschluss fest: Ich werde fliehen. Ich habe meinem Mädel — im Lande dort — versprochen wiederzukommen, ich werde mein Versprechen halten!

Wir beschliessen die Flucht

Die letzte Nacht verbrachten wir im Hofe vor der Kommandantur. Von Corinth her knallten in regelmässigen Abständen Salven. Wer waren die Opfer? Aus unserer Mitte wurden die Kranken und Schwachen ausgesondert und weggebracht. Wir haben sie nie wieder gesehen. Wenige nur hatten sich krank gemeldet, jeder wollte bei den “Seinen” bleiben. Ich und Sch., ein Jugendlicher aus Kfar-Jehoschua, und die vier Brüder S. aus Petach-Tikvah beschlossen, zusammenzuhalten und nach Fluchtmöglichkeiten Ausschau zu halten. Unsere Wasser flaschen sollten immer gefüllt sein und unsere Eiserne Ration, bestehend aus drei Schachteln Biscuit und Kränzen getrockneter Feigen, durfte bis zur Flucht nicht angerührt werden. Mich quälte es, dass ich keine Chinin-Tabletten mehr hatte, denn jeden Tag konnte sich eine Malaria-Attacke einstellen. Das griechische Wörterbuch “Anu Nachsuy arzah” hegte ich wie ein Kind.

Bei Morgengrauen brachen wir auf: tausend Mann in Dreier-Reihen. Wir sangen: “Anu nachasor arzah — libnoth ulebaloth bah” (Wir werden ins Land zurückkehren, es aufzubauen und zu bewohnen). Unsere Stimmen waren die von Verhungernden, doch sie klangen trotzig, ja mutig. Die Häuser von Corinth antworteten uns im Widerhall, die Einwohner rissen Fenster und Türen auf, um uns ein “Victory” – Zeichen zuzuwinken. Wir marschierten wie Sieger, während die Nazi-Wache die Geschäftigkeit nervöser Büffel zeigte und zwangsweise zum Takt unseres Liedes marschieren musste. So sahen uns die Einwohner von Corinth zum letzten Male.

Ein kleines Automobil flog an uns vorbei. Es trug in gotischen Buchstaben die Aufschrift: “Deutsches Konsulat, Kalamata.” Ja, Kalamata war die Stadt, wo wir die britische Flotte vergeblich erwartet hatten — just in der Nacht, da wir palästinensischen Jungens die Deutschen aus dem Ort vertrieben hatten. Das hatte unser Los besiegelt. Oft seither träumte ich, dass vor Kalamata drei Panzerschiffe halten, um uns aufzunehmen.

Durch aufgerissene Strassen, an zerstörten Häusern und niedergebrannten Stadtvierteln vorbei, marschieren wir. Durch Wiesen, Felder und Gärten marschieren wir. “Nach Deutschland” — denken die meisten, ich und Sch. neben mir jedoch denken: in die Freiheit. Heute schon oder morgen wollen wir es versuchen. Unsere Blicke wärmen sich aneinander. Die anderen merken es uns an. Einer der vier Brüder S. flüstert mir zu: “Auch wir sind entschlossen. In Bulgarien oder Rumänien brennen wir durch und schlagen uns von dort nach Russland.” “Meine besten Wünsche”, antworte ich; ‘‘ich bin sicher, es wird euch gelingen. Wir aber machen es schon in Griechenland.”

Hakenkreuz über der Akropolis

In Isthmia am Isthmus werden wir verladen: je 50 Mann in einen Viehwagen. Griechische Frauen sind eifrig bemüht, uns frisches Wasser heranzubringen, unsere Flaschen zu füllen. Es wird aber nicht gewartet, bis alle versorgt sind, man stösst, quetscht uns in die Wagen. Die Hälfte kann sitzen, die andere Hälfte muss stehen. Wie der Zug sich in Bewegung setzt, werden die Türen zugemacht, ein Riegel wird draussen vorgeschoben, doch eine Türspalte bleibt offen, durch die etwas Licht und Luft eindringt. Diese Spalte muss fur uns breiter werden!

Nahe einer Schule halten war. Es ist Unterrichtspause. Die Kinder rufen uns mit hellen Stimmen Grusse zu, auch rufen sie: “Kerenda Mussolini!” Ja, das griechische Volk ist mit uns, das wird unsern Fluchtplan fördern. Man lässt uns aussteigen, wir werden in den Hof einer Kaserne gebracht. Wir merken jetzt: Wir sind in Athen. Wir sind an der gleichen Stelle, von der wir zum Kampf gegen die Deutschen ausgerückt waren. Jetzt aber weht von der Akropolis eine riesige Hakenkreuzfahne.

Wir haben seit einer Woche kaum etwas zu essen bekommen. Jetzt werden jedem Gefangenen ein Stückchen Käse und zwei Biscuits ausgehändigt, das soll für zwei Tage langen. Wann wird das ständige Hungergefühl, ein Ende haben?

Osterreichisch Artilleristen betreten den Hof, lassen sich mit uns in ein Gespräch ein: “Ja, wir können in Deutschland Fachleute gut gebrauchen”, sagt einer. “Ich bin Landwirt”, wehre ich ab. “Auch gut”, fährt er fort. “Auf meinem Hof arbeiten zwei Franzosen und ein Pole, es wird noch Platz sein für einen Engländer. Seien Sie froh, für Sie ist der Krieg zu Ende.”

Grüsse für zuhause

Die Kameraden wissen, was ich im Schilde führe. Sie schleichen sich einzeln zu mir und tragen mir Grüsse für Frau und Kinder auf. D. aus Petach Tickwah händigt mir zwei goldene Manschettenknöpfe ein: “Nutze sie auf deinem Wege auf die beste Art! Sag meiner Freundin, dass ich alles Schwere, was immer es sein mag, ertragen werde, denn ich gebe die Hoffnung nicht auf, sie wieder zu sehen.” Sch. vom Ohel-Theater in Tel-Aviv trägt mir einen Gruss an seine Frau und seinen “Dreikäsehoch” auf. “Du siehst ein bisschen verrückt aus”, witzelt er. “Ich habe meinem Mädel versprochen zurückzukommen; ich muss Wort halten”, murmele ich. “Wir sind verrückt, die wir uns wie Schafe zur Schlachtbank treiben lassen”, gibt er schliesslich zu.

Ein baumlanger Nazi donnert durch den Hof: “Sammeln! Und ohne jüdische Nervosität!”

Wie viele Juden hast du in deinem Deutschland schon gequält und getötet, du Nazihund! denke ich bei mir. Von da her kennst du die jüdische Nervosität. Ich habe sie nicht mehr, mich hat Palästina abgehärtet. Wenn wir uns einmal Auge in Auge gegenüberstehen werden, du Missgeburt, wirst du es sein, der von Nazi-Nervosität geschüttelt werden wird”.

Der erste Fluchtversuch

Wieder auf dem Bahnhof von Athen. Je 50 Mann weiden in einen Viehwagen gepresst. Ich und Sch. nehmen abermals den Platz an der Türspalte ein. Man überlässt ihn uns gern. Auf dem ersten und dem letzten Wagen des Zuges sind Maschinengewehre montiert, in jedem zweiten Wagen sitzt auf einer Kiste ein Nazi mit Gewehr und Revolver. “Wir versuchen es im ersten Tunnel”, flüstere ich Sch. zu. Während der Zug langsam durch die Vorstädte fährt, säumen die Bewohner, in der Mehrzahl Frauen, Mädchen und Kinder, das Geleise zu beiden Seiten, rufen uns ermutigende Wort zu, machen das Victory-Zeichen. Die verärgerten Nazis lassen die Maschinengewehre knallen, doch das schreckt die Athener nicht. Wir strecken unsere Arme durch die Türspalte, rufen und singen, vergessen für eine Weile unsern Hunger. Zur Strafe wird nun auch die schmale Türspalte geschlossen. Die Enge ist unerträglich, die Luft zum Ersticken. Viel später erst wird die Spalte wieder geöffnet, wir fahren an Flugfeldern vorbei; Flugzeuge brennen, Tanks liegen verendet auf den Wegen. Wege und Brücken sind stark bewacht. Man traut den Griechen nicht; das aber macht die Ausführung unseres Planes schwerer als wir es uns dachten. Die Nacht bricht an, es ist starkes Mondlicht. Das ist gut, denke ich mir; wenn der Mond auf der einen Seite scheint, springen wir auf der anderen Seite ab. Es ist abgemacht, dass ich als erster abspringe. Sch. wirft mir das Säckchen zu und springt nach mir. Verlieren wir uns, stosse ich drei Schakalrufe aus, Sch. antwortet mit dem gleichen Signal. Sind wir aber zu weit auseinandergekommen, so treffen wir uns am Morgen vor der Kirche des nächsten Dorfes.

(Wird fortgesetzt)

____________________

I Was a Prisoner of War of The Nazis

October 15, 1943

The author of the following diary pages fled as a very young man from Nazi Germany to Palestine and became a member of kvutzah [kibbutz]. When war broke out, he joined the British army as a volunteer, in which he now occupies a high officer’s rank. During the fighting in Greece he fell into Nazi captivity, from which he was able to free himself after a short time. The description of this captivity and escape is interesting not only as an individual fate, but it is also indicative of the way Jewish soldiers of the Allied armies coming from Germany are handled when they fall into Nazi captivity.

It was at the end of May, when we arrived – finally! – brought to the headquarters for interrogation. In the meantime the Gestapo had all the documents brought in, that they had about us former German Jews. According to international law, we should receive exactly the same treatment as the British prisoners; this law was bypassed in an attempt to prove to us that we were guilty of escaping any misdemeanor in Germany. One of the prisoners was placed under special arrest because it was listed in the Gestapo files, that the last payment remained on a typewriter purchased when leaving Germany. This is an example.

My name is called. I step into the room of the camp commandant and salute. He returns the salute. The strict glances of three German officers are directed at me. Just at that moment, I regain all my confidence: What possibly worse can happen to me, than being shot! So, you have to talk to Germans.

“Do you have parents in Germany?” asks the Commandant sharply, even threateningly.

“Yes,” I answer calmly.

“You graduated from a German high school?”

“Yes.”

“You know Germany?”

“Certainly.”

“In 1938 the German consul in Haifa asked you to join the army service; how is it that as a volunteer in the British army you fought against Germany?”

“Because Germany is our enemy; I hate my enemy!”

Contrary to expectations, the officer rose from his chair, came up to me and patted me on the shoulder: “Very good!”

I confess: that not only desperate courage but also experience spoke to me. I already knew, that this question is asked of all of us, and that it is best, to be short and to be true. Some Jewish soldiers from Palestine had replied, that they had joined the army, because they were unemployed. Immediately they flew out the door, were treated there with footsteps by the guard and further “promoted”. The same happened to a Jewish officer, who had joined the army in England. He had answered the question with “Conscription”. He flew down all the stairs and had to be carried off the square. Three of my comrades from Ashdoth-Ya’akov (name of a kvutzah in Palestine, D. Uebers.) S. and D. and R. gave the same answer as me and got off lightly. So I was not thrown out, but left the commandant’s room with head held high.

Before Transport to the Reich

We were very hungry. The twelve of us were given a loaf of bread. Every day, thousands of us were taken away from the camp. Our brigadier Plenigton sent us the following order, before being transported away:

“Soldiers of the British Army, Australians and New Zealanders! Your fate has willed it that you are in captivity – for the war period. The enemy was superior to us in numbers. You will now see Germany with your own eyes. Maybe you will like a lot there; but beware of any influence. There are rumors circulating that on the shores of Corinth our submarines are waiting to pick up fleeing prisoners. I think that is out of the question. Our fate is sealed. Captivity.”

The last thousand to which I belonged, were transported on 9 June [1941]. I had another bad attack of malaria, and the heat was unbearable. We stood in front of headquarters naked. We had to hand over our clothes and shoes for disinfection; everyone got a rag, like a large handkerchief, to cover his nakedness. So we walked through the streets of Corinth to the sea to take a cleaning. The inhabitants were horrified when they saw this train of naked men, flanked by armed Germans; they stormed into the houses, constantly crossing each other. But we forgot that we were naked: finally out of the barracks out and allowed to march freely! We passed that we were guarded, rushed into the vegetable gardens, dug out the turnips and cucumbers with the fingers, and ate them with the garden soil. Finally to be able to fill your stomach again, no matter what! Finally, we were beaten up again by the excited guards to a train and taken to the beach. There we were splashed with carbolic, and the merciless sun roasted our skin. But when we finally were allowed to swim “freely” in the sea, we forgot all hardship. We shouted for joy.

On the way back we were tortured again by the thought: imprisonment. We looked back longingly to the sea, which connects us to the banks of the Land of Israel. And tomorrow we go to Germany. The decision was made for me: I will flee. I promised my girl – back home – I will keep my promise!

We Decide to Escape

The last night we spent in the courtyard in front of headquarters. From Corinth burst salvos at regular intervals. Who were the victims? From our midst the sick and the weak were separated and taken away. We never saw them again. Few people had called in sick; everyone wanted to remain with “his”. I and Sh., a youth from Kfar-Yehoshua, and the four brothers S. from Petach-Tikvah decided to stick together and look for escape opportunities. Our water bottles should always be filled, and our iron ration, consisting of three boxes of biscuits and wreaths of dried figs, was not to be touched until the flight. It tormented me, that I did not have any quinine tablets any more, because every day a malaria attack could set in. The Greek dictionary “Anu Nachsuy arzah” I cherished as a child.

At dawn we started: a thousand men in rows of three. We sang: “Anu nachasor arzah – libnoth ulebaloth bah.” (We will return to the land to build and inhabit it.) Our voices were those of starving people, but they sounded defiant, even courageous. The houses of Corinth responded to us, the inhabitants broke open windows and doors, to wave a “Victory” sign to us. We marched as victors, while the Nazi guard showed the activity of nervous buffalo and was forced to march to the beat of our song. So we saw the people of Corinth for the last time.

A small automobile flew past us. It bore in Gothic letters the inscription: “German Consulate, Kalamata.” Yes, Kalamata was the city where we had waited in vain for the British fleet – just at night, when we Palestinian boys drove the Germans out of the village. That had sealed our lot. Many times since then I dreamed that three battleships are stopping before Kalamata to receive us.

We are marching through torn-up streets, past destroyed houses and burnt-down neighborhoods. Through meadows, fields and gardens we march. “To Germany” – think most, me and Sch. thinking next to me: into freedom. Today or tomorrow we want to try it. Our eyes warm each other. The others notice us. One of the four S. brothers whispers to me: “We are also determined. In Bulgaria or Romania, we burn through and beat ourselves from there to Russia.” “My best wishes,” I reply; ‘‘I am sure you will succeed. But we already do it in Greece.”

Swastika on the Acropolis

In Isthmia on the isthmus we are loaded: 50 men in each cattle car. Greek women are eager to bring us fresh water; to fill our bottles. But it is not waited until all are supplied; you push; squeezes us in the car. Half can sit; the other half must stand. As the train begins to move, the doors are closed, a bolt is pushed out, but a door gap remains open through which some light and air penetrate. This crack must be wider for us!

A school was holding [class] near us. It is class break. The children greet us with bright voices, they also shout: “Kerenda Mussolini!” Yes, the Greek people are with us, that will promote our escape plan. We are dropped off, we are brought into the yard of a barracks. We now note: we are in Athens. We are in the same place from which we were debarked to fight the Germans. But now blowing from the Acropolis a huge swastika flag.

We have hardly had anything to eat for a week. Now, each prisoner is given a piece of cheese and two biscuits, which will last for two days. When will the constant feeling of hunger come to an end?

Austrian artillerymen enter the yard; engage in a conversation with us: “Yes, we can make good use of experts in Germany,” says one. “I am a farmer”, I refuse. “Also good,” he continues. “On my farm there are working two Frenchmen and a Pole, there will still be room for an Englishman. Be glad, the war is over for you.”

Greetings for Home

The comrades know what I’m up to. They sneak up to me individually and give me greetings for wife and children. D. from Peta Tikva handed me two gold cufflinks: “Use them on your way in the best manner! Tell my girlfriend that I will endure all hardship, whatever it may be, because I will not give up hope to see her again.” Sch. from the Ohel Theater in Tel-Aviv gives me a greeting to his wife and his “Drei Käse Hoch”. “You look a bit crazy,” he jokes. “I promised my girl to come back; I have to keep my word,” I mutter. “We are crazy, we drive like sheep to the slaughter,” he finally admits.

A skinny Nazi thunders through the yard: “Gather! And without Jewish nervousness!”

“How many Jews have you already tormented and killed in your Germany, you Nazi dog!”, I think to myself. From there you know the Jewish nervousness. I no longer have it; Palestine hardened me. When we meet face to face, you freak, it will be you who will be shaken by Nazi nervousness.”

The First Escape Attempt

Back at the station of Athens. 50 men pressed in every cattle car. Sch and I take the place again at the the door crack. You leave it to us. Machine guns are mounted on the first and last cars of the train; in every second car sitting on a box a Nazi with rifle and revolver. “We try in the first tunnel,” I whisper to Sch. As the train slowly drives through the suburbs, the inhabitants, mostly women, girls and children, line the tracks on both sides, calling encouraging words, making the victory sign. The angry Nazis crack the machine guns, but that does not scare the Athenians. We stretch our arms through the crack in the door, shout and sing, forget our hunger for a while. As a punishment, the narrow doorway is now closed. The narrowness is unbearable; the air suffocating. Much later, the crack is opened again; we drive past airfields; burning aircraft; destroyed tanks lying on the roads. Paths and bridges are heavily guarded. One does not trust the Greeks; but that makes the execution of our plan harder than we thought it would be. The night is breaking, it’s strong moonlight. That’s good, I think; when the moon shines on one side, we jump on the other side. It’s settled that I’ll jump first. Sch. throws me the little bag and jumps after me. If we lose ourselves, I’ll make three jackal calls, Sch. responds with the same signal. But if we have come too far apart, we meet in the morning in front of the church of the next village.

(To be continued)

____________________

________________________________________

____________________

Ich war ein Kriegsgefangener der Nazis

October 22, 1943

In unserem Artikel in der vorigen Nummer wurde berichtet, wie ein in Deutschland geborener Palästinenser, der in der britischen Armee diente, von den Nazis gefangen genommen wird und nach Deutshland abtransportiert werden soll. Im ersten Artikel beschrieb er das Verhör vor Nazi- Offizieren, die Behandlung der Gefangenen, die Reise im Viehwagen durch Griechenland und seinen ersten missglückten Fluchtversuch.

II.

Einer schaffts

Bei der ersten Weg krümmung strecke ich die Hand heraus, um den Riegel zurückzuschieben und drücke dabei den Körper nach. Da schiesst man auch schon. Auf der nächsten Haltestelle betritt eine Wache unsern Wagen. Wer war es gewesen? Wir stellen uns alle schlafend; doch als die Wache den Wagen verlässt, setzt es Vorwürfe von allen Seiten: Um der Verrücktheit des Einen willen dürfen licht alle gefährdet werden! Jetzt dringt Geschrei aus dem benachbarten Wagen. Dort hat einer Magenkrämpfe. Seit Athen hat man uns keine Gelegenheit gegeben, unsere Bedürfnisse zu verrichten. Jetzt schreien auch andere. Hier eröffnet sich eine Möglichkeit…, denke ich mir. Endlich wird der Zug zum Halten gebracht, man erlaubt uns, in kleinen Gruppen auszusteigen. Nein, da ist keine Fluchtmöglichkeit. Doch ich sollte beschämt werden: Als der Zug sich schon weiter bewegte und die wenigen Gefangenen draussen brutal in die Wagen zurückgestossen wurden, fiel es einem ein, sich eine Zigarette anzuzünden. Er hielt das Streichholz so, dass es dem Nazi für eine Sekunde die Augen blendete. Diese Sekunde benützte er, um zu verschwinden. Wie aber verschwand er? Plötzlich war er selber wie ein Zündholz erloschen. Es war uns allen ein Rätsel. Später einmal traf ich ihn in Corditza, und da erzählte er mir, er sei einfach durch die Räder zwischen die Schienen geschlüpft, habe sich längelang ausgestreckt, bis der ganze Zug über ihn hinweggefahren war. Ja, so war er: ein geborener Palästinenser, ein “Sabre” (hartes, Palästina eigentümliches Kaktus-Gewächs; Bezeichnung für das unverwüstliche Landeskind).

Als der Zug den ersten Tunnel passierte, machte ich abermals einen Versuch herunterzuspringen; auch diesmal wurde ich bemerkt, Sch. zog mich in den Wagen zurück. Ich war sehr enttäuscht, denn bald kamen wir in das Flachland hinter Larissa, wo die Möglichkeit zu einer Flucht stark gemindert war. Müdigkeit übermannte mich nach all der Anspannung. Die meisten Insassen waren krank nach der ganztägigen Fahrt im überfüllten Viehwagen. An der Haltestelle Gradia stiegen wir aus: Wir durften marschieren. Wie das gut tat! Doch, ach, wie weh das tat, als wir viele, viele Stunden lang auf steinigen Wegen über das Massiv der Termopylen marschieren mussten. Eine wundervolle Landschaft! Auf jenem hohen Pass, den wir bald betreten werden, hat, 480 Jahre v. Chr. Leonidas mit dreihundert Spartanern Xerxes. Riesenheer aufgehalten. Man kann nur mit schmerzenden Augen in die Landschaft sehen, nur mit schmerzendem Kopf an ihre grosse Geschichte denken. Hätte man uns Palästinenser an dieser Stelle eingesetzt, wir hätten wie Leonidas gekämpft; jetzt führt man uns, stösst man uns mit Gewehrkolben durch den Termopylenpass in die Gefangenschaft nach Deutschland. Ja, man stösst uns; denn die Nazi- Wachmannschaft fühlt sich in dieser Einsamkeit, fern von einer Militärbasis, nicht ganz wohl. Rennen müssen wir, schnell, schnell!

Vor dem ersten Dorf jenseits des Passes kommen uns die Bauern entgegen und helfen uns die Packe tragen. Manche von uns haben nichts mehr von ihren Sachen, sie hatten in ihrer Müdigkeit alles auf dem Wege von sich geworfen. Wir dürfen rasten. Wenn wir uns hinlegen, zittern unsere Knie. Wir sind auf einer Bergspitze. Eine deutsche Aufschrift am Wege lautet: “Vorsicht! 18 Kilometer bergab.”

Zweiter Fluchtversuch

Ich gebrauche die Ausrede, dass ich ein Bedürfnis verrichten will, gehe seitwärts und beschliesse, den abschüssigen Hang hinunterzurollen. Sch. schleicht mir nach, will das gleiche tun. Schon aber steht ein deutscher Soldat an meiner Seite. Ich flüstere Sch. zu: “Ich versuche es bei der nächsten Krümmung des Weges, du hinter mir. Die erste Wache wird uns nicht mehr, die zweite noch nicht sehen.”

Wie gesagt, so getan. Ich springe, verschwinde in einem Graben; Sch. und einige andere folgten meinem Beispiel. Diese anderen verdarben uns den Brei. Denn durch sie, die spontan und ohne Ueberlegung und Vorsicht handelten, wurde die Aufmerksamkeit der Wache auf uns gelenkt. Ein Soldat schrie: “Herr Leutnant, es ist was passiert!’’ Der Leutnant und einige seiner Leute umzingelten mit gestreckter Waffe den Graben; bis aber die Aktion durchgeführt werden konnte, hatten die meisten von uns Zeit in die Reihen zurück zuschleichen. Die Nazis schössen in den Graben hinein, brachten einige Flüchtlinge mit Kolbenstössen zuruck. Zwei fehlten. Waren sie von den Kugeln getroffen worden?

Jetzt ist die Stimmimg unter den Kameraden einheitlich gegen uns. Man hetzt gegen uns, doch man verrät uns nicht der untersuchenden Wachmannschaft. Sch. flüstert mir zu, ich dürfe nicht mehr auf ihn rechnen, er sei mit seinen Nerven zu Ende. Schliesslich wolle er noch einmal sein Mädchen wiedersehen. Dann mache ich’s allein, erwiderte ich ihm; auch ich will meine Geliebte wiedersehen.

Wir marschieren, marschieren; es ist keine Kraft mehr in uns, automatisch tun die Beine ihren Dienst. Auch die Wachmannschaft ist vollkommen erschöpft. Wir haben die Thermopylen bereits hinter uns und bewegen uns auf Lamia zu. Auf dem Bahnhof angelangt, sinken wir wie leere Säcke zu Boden. Doch nein, auf müssen wir und schnell in die Wagen hinein je 50 in einen Viehwagen. Wir bilden alle einen einzigen verworrenen Knäuel. Ich habe mir meinen Platz an der Türspalte zu wahren gewusst.

Frei!

Jetzt fahren wir über eine Brücke. Ist das Wasser tief genug? Kann man springen? — geht es mir durch den Kopf. Ich warte nicht, bis ich mir selbst eine Antwort gegeben habe. Riegel weg, Tür auf und an das Geländer gesprungen! Die ersten Schüsse knallen. Ich schwinge mich über das Geländer und springe. Ja, das Wasser war tief genug. Ich bleibe unter der Fläche, solange mein Atem es verträgt, dann tauche ich auf: der Zug ist über die Brücke hinweg und fährt in seinem normalen Tempo weiter. Wahrscheinlich hat man mich nicht wieder auftauchen gesehen. Ich bin ein freier Mann!

Ich schwimme zum Ufer zurück, strecke mich hin und trockne in der Sonne. Ich sollte eigentlich ein Versteck suchen, doch ich bin zu müde dazu. Ich liege zwischen hohen Weiden, ich entwerfe einen Plan für weitere Handlungen. Ich bin jetzt meine eigene Armee und mein eigener Kommandant. Ich unterstehe keinem Gesetz ausser dem meines Gewissens; ich werde stehlen, wenn nötig rauben, um mich in der Freiheit zu behaupten. Mir ist gut. Nur tut mir Sch. leid. Er ist ein feiner Kerl.

Ich hole meine Eiserne Ration hervor; es ist alles durchnässt, die Feigen schmecken trotzdem gut. Die Nacht ist angebrochen, Schlaf will mich übermannen, ich kämpfe mit allen Kräften dagegen. Die Nacht ist die Wanderzeit für den Flüchtling. Bis zum Morgen muss ich aus der Zone von Lamia heraus sein. Ich wandere zurück zu den Thermopylen — quer durch Weingärten und Felder und längs enger Stege. Alles kann Gefahr bedeuten, jeden darfst du verdächtigen, sage ich mir. Irgendwo werde ich eindringen und mir zivile Kleider verschaffen, in meiner britischen Uniform darf ich nicht mehr gesehen werden. Nach mehreren Stunden Wanderung falle ich entkräftet hin. Mosquitos peinigen mich, doch ich habe nicht die Kraft, sie abzuwehren. Ich sinke in Schlaf.

(Schluss folgt)

____________________

I Was a Prisoner of War of The Nazis

October 22, 1943

In our article in the previous issue, it was reported how a German-born Palestinian serving in the British Army was captured by the Nazis and was to be transported to Germany. In the first article he described the interrogation before Nazi officers, the treatment of prisoners, the journey in the cattle car through Greece and his first unsuccessful escape attempt.

II.

One [Escape Attempt] Is Made

At the curve of the route, I stretch my hand out to push back the latch, while pushing the body forward. [There are already shots.] At the next stop, a guard enters our car. Who was it? We all go to sleep; but when the guard leaves the car, reproaches from all sides: For the sake of the madness of one, all will be endangered! Now shouting comes from the neighboring car. There are stomach cramps. Since Athens we have been given no opportunity to meet our needs. Now others are screaming too. This opens up a possibility…, I think. Finally the train is stopped, we are allowed to get off in small groups. No, there is no escape. But I should be ashamed: As the train moved on and the few prisoners outside were brutally pushed back into the cars, it occurred to one to light a cigarette. He held the match in such a way that it blinded the Nazi for a second. He used that second to disappear. But how did he disappear? Suddenly he was extinguished like a match. It was a mystery to all of us. Later, I met him in Corditza, and he told me that he had simply slipped through the wheels between the rails, stretching himself out for a long time, until the whole train had passed over him. Yes, that’s how he was: a born Palestinian, a “Sabra” (a tough, peculiar Palestinian cactus plant; a nickname for the indestructible child of the land).

As the train passed the first tunnel, I made another attempt to jump off; I was also noticed this time, Sch. pulled me back in the car. I was very disappointed, because soon we came to the plain behind Larissa, where the possibility of an escape was greatly reduced. Fatigue overwhelmed me after all the tension. Most of the inmates were ill after the full day’s journey in the crowded cattle car. At the Gradia station we got out: we were allowed to march. How that did good! But, alas, how much it hurt when we had to walk for many, many hours on rocky paths over the massif of Thermopylae. A wonderful landscape! On that high pass, which we will soon enter, 480 years before Christ Leonidas stopped Xerxes’ giant army with three hundred Spartans. One can only look with aching eyes into the landscape, only think of their great story with an aching head. If Palestinians had been used here, we would have fought like Leonidas; now they lead us, they push us with rifle butts through the pass of pass of Thermopylae into German captivity. Yes, they push us; because the Nazi guards do not feel well in this solitude, far from a military base. We have to race, fast, fast!

In front of the first village on the other side of the pass, the farmers meet us and help us carry packs. Some of us have nothing left of their belongings; they had thrown everything off in their fatigue. We are allowed to rest. When we lie down, our knees are shaking. We are on a mountaintop. A German inscription on the way reads: “Caution! 18 kilometers downhill.”

Second Escape Attempt

I use the excuse that I want to do something; go sideways and decide, to roll down the steep slope. Sch. sneaking after me, wants to do the same. But a German soldier already stands by my side. I whisper to Sch.: “I will try at the next bend of the path, you behind me. The first guard will not be with us any more, the second will not yet see us.”

As I said, so is done. I jump; disappear in a ditch; Sch. and some others followed my example. These others spoiled the porridge. Because by those, who acted spontaneously and without thought and caution, the attention of the guard was directed to us. A soldier shouted, “Lieutenant, something has happened!” The lieutenant and some of his men surrounded the ditch with their weapons outstretched, but until the action could be carried out, most of us had time to sneak back into the ranks. The Nazis shot into the ditch, bringing back some fugitives with piston-like thrusts. Two were missing. Were they struck by the bullets?

Now the voice among the comrades is uniformly against us. One agitates against us, but we are not betrayed to the investigating guards. Sch. whispered to me, I should not count on him anymore; he was over his nerves. He wanted to finally to see his girl again. Then I’ll do it alone, I told him; I too want to see my beloved again.

We march, march; there is no power left in us, the legs automatically do their job. The guards are also completely exhausted. We already have Thermopylae behind us and are moving towards Lamia. Arriving at the station, we sink to the ground like empty sacks. But no, we have to quickly get into the cars, 50 in each cattle car. We all form a single tangled ball. I’ve been able to save my place at the door crack.

Free!

Now we drive over a bridge. Is the water deep enough? Can you jump? – it goes through my head. I will not wait until I have given myself an answer. The latch is off; open the door and jump to the railing! The first shots crack. I swing myself over the railing and jump. Yes, the water was deep enough. I stay under the surface as long as my breath can withstand it, then I emerge: the train is across the bridge and continues at its normal pace. I guess they did not see me resurface. I am a free man!

I swim back to the shore, stretch myself and dry in the sun. I should be looking for a hiding place, but I’m too tired. I lie between high pastures; I design a plan for further action. I am now my own army and my own commander. I am not subject to any law except that of my conscience; I will steal, rob if necessary, to maintain myself in freedom. I am good. Now my Sch. Is suffering. He is a fine fellow.

I bring out my Iron Ration; everything is soaked, but the figs taste good anyway. The night has come, sleep wants to overwhelm me, I fight against it with all my strength. The night is the walking time for the fugitive. I have to be out of the zone of Lamia by morning. I walk back to Thermopylae – across vineyards and fields and along narrow walkways. Everything can be dangerous, you can suspect anyone, I tell myself. I will enter somewhere and get civilian clothes; I can not be seen anymore in my British uniform. After several hours of hiking, I fall over exhausted. Mosquitoes torment me, but I do not have the strength to fight them off. I sink into sleep.

(Conclusion follows)

____________________

________________________________________

____________________

Ich war ein Kriegsgefangener der Nazis

(Schluss)

Der Morgen danach

October 29, 1943

Das Geräusch eines Motors weckt mich am Morgen. Das Klopfen eines Motors, der mit Ersatzmaterialien angetrieben wird. Ein deutscher Motor also. Und ich trage noch meine englische Uniform! Ich verkrieche mich, und obwohl ich am Verdursten bin, rühre ich mich nicht von der Stelle. Wieder sinke ich in Schlaf. Der Hall von Axtschlägen weckt mich. Ich richte mich auf, der Holzfäller erblickt mich, kommt unschlüssig auf mich zu. ‘‘Ich bin ein britischer Soldat, aus der Gefangenschaft entflohen”, sage ich in meinem Wörterbuch – Griechisch. Er hat mich verstanden, drückt mir fest die Hand, küsst mich. Er überlässt mir seinen Krug Wasser, etwas Wein und Brot; gibt mir zu verstehen, dass ich den Tag über hier bleiben müsse. Am Abend werde er kommen und mich holen.

Er kam mit seinem Esel. “Andaki”, flüstert er mir zu. Das heisst: “alles in Ordnung.” Er stülpt mir einen Riesen hut auf und wirft einen Shawl über meine Schulter, um die Uniform zu verdecken. Er geht voraus, ich in Sehweite hinter ihm. Wir machen einen Umweg durch das Dorf, gelangen durch Gärten und Hecken zu seinem Haus. Ein kleines Mädchen fasst meine Hand, ich spüre, wie ihr Herzchen in freudiger Erregung pocht. Es bringt mich ins Haus: Mutter und Kinder, sowie andere Familienmitglieder begrüssen mich herzlich. Er ist dunkel, der ganze grosse Raum wird von dem Lichtlein am Hausaltar schwach erhellt. Die Holzfällerfrau bringt einen alten schweien Stuhl heran, ladet mich zum Sitzen ein, und alle kauern auf der Diele um mich herum. Ein Mädchen zieht mir die Schuhe ab, wäscht und trocknet mir die Füsse. Ich bin verlegen, doch lasse ich es geschehen. Mir fällt ein: das war Tradition im alten Griechenland. Soll sich seither hier nichts geändert haben?

“Lechajim”

Der Bauer-Holzfäller tritt ein: freudig und stolz, dass ich mich in seinem Hause befinde. Er bringt Kuchen und Wein. Wir trinken. Mir fällt das nötige griechische Wort nicht ein, ich sage das hebräische “Lechajim” (Trinkgruss: “zum Leben”). Sie sprechen mir das Wort schlecht und recht nach, in der Meinung wohl, es sei der englische Trinkgruss. Die Bäuerin bringt Brot und warme Suppe. Obwohl die Suppe nur massig warm ist, brennt sie mir im Magen, der so lange schon nichts Warmes gespürt hat. Der Bauer schneidet das Brot, teilt jedem sein Stück zu: mir zuerst, dann der Bäuerin, dann den übrigen Familienmitgliedern. Nach dem Essen bringt er ein paar abgetragene Hosen und einen Rucksack. Er weist mir ein Holzgestell zum Schlafen an und verspricht mir, mich vor Morgengrauen zu wecken.

Als er mich weckt, springe ich erfrischt auf. Ich bin trunken vor Freude: ich bin ein freier Mann, habe Zivilkleider an, mich werden “sie” nicht kriegen. Die Bäuerin segnet mich, wünscht mir Schutz vor dem Antichrist, dem “Germanus”. Ich verneige mich tief und schreite los.

Ich schreite durch fruchtbares Gebirgsland. Bächlein rieseln. Alle 500 Schritte fülle ich meine Flasche neu. Ich bin wassertrunken, ich spiele mit Wasser. Ich erinnere mich, wie wir britische Soldaten in der lybischen Wüste nach Wasser vergebens lechzten. Ich esse von dem Brot und dem Käse, die mir von der Holz fäller-Familie als Wegzehrung mitgegeben worden waren. Ich brauche mir nicht mehr den Bissen von. Munde zu sparen. Arbeten werde ich — als Viehjunge oder un Stall, ich hab’s ja in Palastina gelernt – bis ich mich wieder zur Armee durchschlagen kann.

In Sicherheit

Durch Weingärten geht es. In einem sehe ich einen zerschmette_ten Junkers, einige Grabkreuze daneben: deutsche Namen und der Zusatz: “Gefallen für Grossdeutschland.” Mit “Deutschland erwache, Juda verrecke” hat es begonnen und mit “Gefallen” endet es.

Ich nähere mich einem Dorf. Dort sind Deutsche. Ich sehe Spuren von Autorädern, höre Hupen und Klingeln. Ich schlage einen aufwärts führenden Steg ein, verstecke mich nahe einem Brunnen mit Heiligenbild. Gegen meinen Willen schlafe ich ein. Als ich aufwache, kniet eine Frau vor dem Altar. Ich frage sie: “T’unoma hurian?” (Wie heisst das Dorf?) “Germanus messo?” (Sind Deutsche hier?) Sie erwidert mit einer Frage: “Ssiss stratiatus?” (Bist du Soldat?)

Als ich ihr sage, ich sei ein aus der Gefangenschaft entflohener britischer Soldat, eilt sie auf mich zu, drückt mir die Hände, weint, erzählt, ihr Mann und ihr Sohn seien in Albanien gefallen. Sie geht, kommt nach kurzer Zeit mit einem Esel zurück, gibt mir zu essen. Dann lässt sie mich aufsitzen und schreitet neben mir her. Aufwärts geht es. Sie lehnt entschieden ab, aufzusitzen und mich den Esel antreiben zu lassen. Sie bedeutet mir, ich brauche die Kraft gegen diesen verfluchten “Italius”. Ich blicke ins Dorf hinunter: im Zentrum flattert die Nazi-Fahne. Diesen Weg zurück werde ich nicht gehen – steht bei mir fest.

Immer aufwärts geht es durch Gärten und Tabakfelder. Plötzlich bietet sich ein schönes Bergdorf zwischen Obst- und Weingärten meinen Blicken dar. Die Frau weist auf eine Bergspitze, auf der ein Kloster — “Monastir” sagt sie — steht. Ich steige ab, atme froh die dünne Bergluft ein.

Einige Minuten später betreten meine Füsse den Boden des Bergdorfes “Ypati”. Gesegnet sei es.

F. J-n.

____________________

I Was a Prisoner of War of The Nazis

(Conclusion)

October 29, 1943

The sound of an engine wakes me in the morning. The knocking of a motor, powered by substitute materials. So, a German engine. And I still wear my English uniform! I crawl, and although I’m dying of thirst, I do not move. Again I fall asleep. The echo of an ax-strike awakens me. I sit up, the wood cutter sees me, comes hesitantly toward me. ‘‘I am a British soldier, escaped from captivity,” I say in my dictionary – Greek. He has understood me, presses my hand firmly, kisses me. He leaves me his jug of water, some wine and bread; gives me to understand that I have to stay here all day. In the evening he will come and get me.

He came with his donkey. “Andaki,” he whispers to me. That means “all right.” He puts on a giant hat and throws a shawl over my shoulder to cover the uniform. He goes ahead, I in sight behind him. We make a detour through the village, passing through gardens and hedges to his house. A little girl holds my hand; I feel her heart beating in joyful excitement. He brings me into the house: Mother and children, as well as other family members greet me warmly. It is dark, the whole big room is dimly lit by the little light at the family altar. The wood cutter’s wife pulls up an old sweaty chair, invites me to sit, and everyone in the hallway is huddled around me. A girl takes off my shoes; washes and dries my feet. I am embarrassed, but I let it happen. I remember: that was a tradition in ancient Greece. Should anything not have changed here since then?

“Lechaim”

The farmer-wood cutter enters: happy and proud that I am in his house. He brings cake and wine. We drink. I do not remember the necessary Greek word; I say the Hebrew “Lechaim” (drinking greeting: “to life”). The word is spoken to me badly and right after, in the sentiment probably, it is the English drinking greeting. The farmer’s wife brings bread and warm soup. Although the soup is just moderately warm, it burns in my stomach, which has not felt anything warm for so long. The farmer cuts the bread, distributing to each his piece: me first, then the farmer’s wife, then the other family members. After dinner, he brings a pair of worn pants and a backpack. He instructs me to sleep on a wooden frame and promises to wake me up before dawn.

When he wakes me, I jump up refreshed. I am drunk with joy: I am a free man, have on civilian clothes, “they” will not get me. The farmer’s wife blesses me, wishing me protection from the Antichrist, the “Germanus”. I bow deeply and start walking.

I walk through fertile mountain land. Trickling brooks. Every 500 steps, I refill my bottle. I drink water; I’m drunk on water. I remember how, as thirsting British soldiers we craved in vain for water in the Libyan desert. I eat the bread and cheese that I got from the wood cutter’s family as a treat for the way. I do not need the bite of it. To save money. I will work – as a cattle boy or in a stable; I learned it in Palestine – until I can make my way back to the army.

In Safety

I go through vineyards. In one I see a smashed Junkers, some grave crosses next to it: German names and the addition: “Fallen for Grossdeutschland.” It started with “Germany awake, Judah perish” and ends with “Fallen”.

I’m approaching a village. There are Germans. I see traces of car wheels, hear horns and ringing. I strike an up-leading footbridge, hide myself near a fountain with a holy image. Against my will I fall asleep. When I wake up, a woman kneels before the altar. I ask her: “T’unoma hurian?” (What’s the name of the village?) “Germanus messo?” (Are Germans here?) She replies with a question: “Ssiss stratiatus?” (Are you a soldier?)

When I tell her that I am a British soldier escaped from imprisonment, she rushes towards me, shaking my hands, crying, telling me that her husband and son have died in Albania. She leaves, comes back after a short time with a donkey, gives me food. Then she lets me sit up and walks next to me. It goes uphill. She resolutely refuses to sit, and let me drive the donkey. It means to me, I need the strength against this accursed “Italius”. I look down into the village: in the center the Nazi flag flutters. I will not go back this way – I am sure.

It always goes uphill through gardens and tobacco fields. Suddenly, my view of a beautiful mountain village between orchards and vineyards. The woman points to a mountain top on which is a monastery – “Monastir” she says – stands. I climb off, breathe in the thin mountain air.

A few minutes later my feet enter the bottom of the mountain village “Ypati”. Blessed be it.

F. J-n.

________________________________________

____________________________________________________________

________________________________________

References

“Gelber 1984” – Gelber, Yoav, Jewish Palestinian Volunteering in the British Army During the Second World War – Volume IV – Jewish Volunteers in British Forces, World War II, Yav Izhak Ben-Zvi Publications, Jerusalem, Israel, 1984

Gelber, Yoav, Palestinian POWs in German Captivity, Yad Vashem Studies, Jerusalem Israel, 1981, Volume XIV, pp. 89-137

“We Will Remember Them I” – Morris, Henry, Edited by Gerald Smith, We Will Remember Them – A Record of the Jews Who Died in the Armed Forces of the Crown 1939 – 1945, Brassey’s, London, England, 1989

“We Will Remember Them II” – Morris, Henry, Edited by Hilary Halter, We Will Remember Them – A Record of the Jews Who Died in the Armed Forces of the Crown 1939 – 1945 – An Addendum, AJEX, London, England, 1994

Prisoners of War – Armies and Other Land Forces of The British Empire, 1939-1945 (“All Lists Corrected Generally Up to 30th March 1945″), J.B. Hayward & Son, in Association with The Imperial War Museum Department of Printed Books, Polstead, Suffolk, England, 1990 (First published in 1945 by His Majesty’s Stationary Office)