Stories and depictions of World War One combat, composed both during and after the “Great War”, are abundantly available in print and on the web.

A fascinating source of such accounts – but even moreso a source particularly; poignantly ironic – is the newspaper Der Schild, which was published by the association of German-Jewish war veterans, the “Reichsbundes Jüdischer Frontsoldaten”, from January of 1922 through late 1938, the latter date paralleling the disbandment of the RjF. Der Schild is available as 35mm microfilm at the Dorot Jewish Division of the New York Public Library, and in digital format through Goethe University Frankfurt am Main.

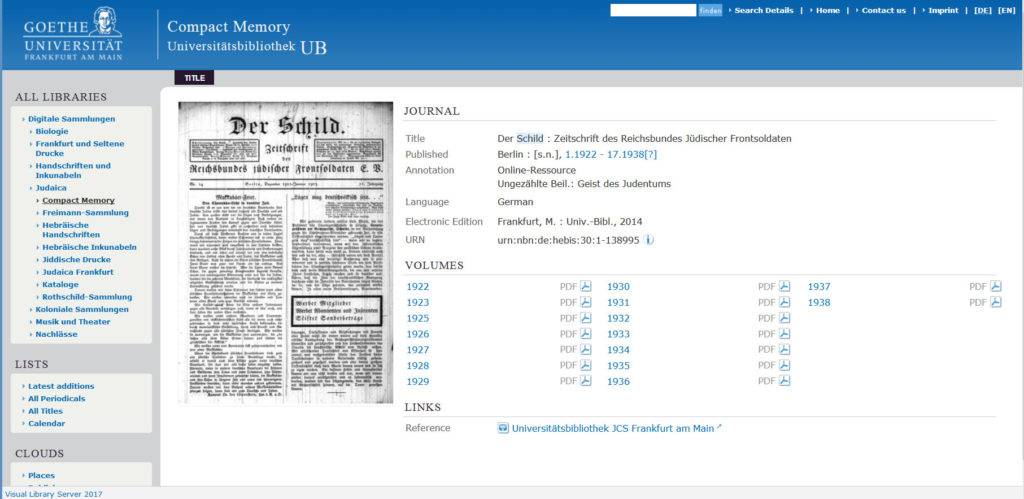

The screen-shot below shows the Goethe University’s catalog entry for Der Schild, which allows for immediate and direct access of the library’s holdings of the newspaper. All years of the publication, with the exception of 1924, are available; all as PDFs.

Of equal (greater?!) importance, accessing digital holdings is as simple as it is intuitive (and easy, too!) In effect and intent, this is a very well designed website! This is shown through this screen-shot, presenting holdings of Der Schild for 1933.

Of equal (greater?!) importance, accessing digital holdings is as simple as it is intuitive (and easy, too!) In effect and intent, this is a very well designed website! This is shown through this screen-shot, presenting holdings of Der Schild for 1933.

The total digitized holdings of Der Schild in the Goethe University’s collection comprise approximately 530 issues. “Gaps” do exist, with 1922 comprising only four issues (9, 10, 13, and 14) and 1923 comprising three issues (14, 15, and 17). However, holdings for all years commencing with 1925 are – I believe – complete, through the final issue (number 44, published November 4, 1938).

The total digitized holdings of Der Schild in the Goethe University’s collection comprise approximately 530 issues. “Gaps” do exist, with 1922 comprising only four issues (9, 10, 13, and 14) and 1923 comprising three issues (14, 15, and 17). However, holdings for all years commencing with 1925 are – I believe – complete, through the final issue (number 44, published November 4, 1938).

Not unexpectedly, Der Schild’s content shed’s fascinating and retrospectively haunting light on Jewish life in Germany during the 1920s and 1930s; on Jewish genealogy; on the military service of German Jews (not only in the First World War but the Franco-Prussian War as well), often focusing on Jewish religious services at “the Front”, rather than “combat”, per se (see the issue of April 3, 1936, with its cover article “Pesach vor Verdun”); on occasion about Jewish military service in the Allied nations during “The Great War”(1); on Jewish history, literature, and religion; on Jewish life and Jewish news outside of Germany.

There is much to be explored.

While reviewing Der Schild at the New York Public Library, I discovered a front-page article – published less than a year before the newspaper’s final issue – which was particularly striking both in its content and prominence: An account of an infantry battle against British tanks, at Cambrai, France, in November of 1917. Certainly Der Schild carried innumerable articles – lengthy and brief – about the military service of German Jews, but these items were not always so boldly displayed as one might assume. The prominence of this article prompted curiosity and in turn, an attempt at translation. Which, is presented below.

Unlike the letter of Martin Feist, Carl Anker’s article neither carries nor imparts any deep spiritual insights or moral messages.

It is simply an utterly direct story about a battle now almost a century gone by.

Erinnerungen an die

Tankschlacht bei Cambrai

Memories of the

Tank Battle at Cambrai

Der Schild

December 10, 1937

Unser Kam. Carl Anker, Hamburg, überlässt uns freundlicherweise seine interessanten Erinnerungen aus der grossen Durchbruchs-Schlacht bei Cambrai 1917 nach seinen Kriegstagebuch-Aufzeichnungen.

Our comrade, Carl Anker, of Hamburg, kindly leaves his interesting memoirs from the great breakthrough battle at Cambrai in 1917 according to the notes in his war diary.

In der Nacht vom 16 zum 17 November kamen wir, die 8. Komp. I.R. 84, von Noyelles nach vorne auf Wache. Ich hatte einen Unteroffizier-Posten, also mit 6 Mann eine Wache für mich. Um 8 Uhr abends kamen wir an, um 1 Uhr zog ich mit meinen 6 Mann nach __rne in die Feldwache. Drei Löcher, jedes für 2 Mann, in Abständen von ca. 30-40 Schritt, nahmen uns auf. Ich, als Wachthabender, hatte beständig von Loch zu Loch zu patrouillieren; dieses Vergnügen dauerte bis früh um 7 ½ Uhr. Dann wurde es so hell, dass man von hinten Uebersicht über das gesamte Gelände hatte, und wir zogen uns auf ein anderes grösseres Loch, das “Gruppennest” ca. 20 Schritte weiter hinten zurück und blieben dort von früh um 7 ½ bis abends 6 Uhr: – dann wurde es wieder so dunkel, dass die Posten besetzt werden mussten. Vom Greppennest wurde durch einen Mann Posten gestanden; von hier aus ging auch ein Verbindungsgraben nach hinten, – ca. 600 m zur Feldwache -, wo ein tiefer Unterstand mit dem Wachthabenden und der Ablösung lag. Von abends 6 Uhr lagen wir wieder vorne auf Posten,

In der Nacht vom 16 zum 17 November kamen wir, die 8. Komp. I.R. 84, von Noyelles nach vorne auf Wache. Ich hatte einen Unteroffizier-Posten, also mit 6 Mann eine Wache für mich. Um 8 Uhr abends kamen wir an, um 1 Uhr zog ich mit meinen 6 Mann nach __rne in die Feldwache. Drei Löcher, jedes für 2 Mann, in Abständen von ca. 30-40 Schritt, nahmen uns auf. Ich, als Wachthabender, hatte beständig von Loch zu Loch zu patrouillieren; dieses Vergnügen dauerte bis früh um 7 ½ Uhr. Dann wurde es so hell, dass man von hinten Uebersicht über das gesamte Gelände hatte, und wir zogen uns auf ein anderes grösseres Loch, das “Gruppennest” ca. 20 Schritte weiter hinten zurück und blieben dort von früh um 7 ½ bis abends 6 Uhr: – dann wurde es wieder so dunkel, dass die Posten besetzt werden mussten. Vom Greppennest wurde durch einen Mann Posten gestanden; von hier aus ging auch ein Verbindungsgraben nach hinten, – ca. 600 m zur Feldwache -, wo ein tiefer Unterstand mit dem Wachthabenden und der Ablösung lag. Von abends 6 Uhr lagen wir wieder vorne auf Posten,

In the night of the 16th to 17th of November we arrived, the 8th Company, 84th Infantry Regiment, forward on guard from Noyelles. I had a non-commissioned officer’s station, with 6 men on guard duty for me. We arrived at eight o’clock in the evening; at 1 o’clock I went with my 6 men to the field guard. Three holes, each for two men, in intervals of about 30-40 paces, were taken by us. I, [keeping watch], had to patrol constantly from hole to hole; this pleasure lasted until early in the morning at 7:30 hours. Then it was so bright, that we had an overview of the whole terrain from behind, and we moved to another larger hole, the “group nest” about 20 paces farther back, and stayed there from early morning at 7: 30 to 6 o’clock in the evening: – then it was again so dark again, that the posts had to be occupied. A man stood post by the group nest; from here a connecting trench also went to the rear – about 600 meters to the field guard -, where there was a deep dugout with the guard and the detachment. From the evening at 6 o’clock we were again located at the post,

ca. 49 Schritte vom englischen Graben entfernt.

about 49 steps from the English trench.

Nach Einsetzen der Dunkelheit erhielten wir Verpflegung. Um 1 Uhr Nachts kam unsere Ablösung von der Feldwache, nachdem wir also 24 Stunden vorne gewesen.

After darkness we received food. At 1 o’clock in the evening, our detachment came from the field guard, after we had been at the front for 24 hours.

Zwei mal 7 Stunden hintereinander auf Posten, ohne Bewegung, lautlos, in denkbar nächster Nähe des Gegners, am Tage ein Lager auf hartem Brett, in freier Luft, nur ein Stück Wellblech gegen Regen über dem Körper! Nicht rauchen, tagsüber der Qualm, nachts der Feuerschein!

Two times seven hours in a row, without a movement, silently, in the immediate vicinity of the enemy, in the day camping on a hard plank, in the open air, only a piece of corrugated iron over the body against the rain! Do not smoke, smoke during the day, the fire at night!

In der nacht vom 17. zum 18. wurde ich also abgelöst, kam kurz nach 1 Uhr in der Feldwache an und konnte bis früh um 6 Uhr schlafen. Da wurde alles alarmiert. Eine Gewaltspatrouille kam zur Durchführung. Lt. Hegermann, Lt. Störzel, am Tage vorher befordert, und noch einige andere Offiziere leiteten die Sache. Artillerie, Minen- und Granatwerfer riegelten das betreffende englische Grabenstück ab, die Patrouille drang vor, sprengte den Draht und brachte einen Vizefeldwebel und 6 Mann als Gefangene zurück. Wir selbst verloren Lt. Störzel als Toten und mehrere Verwundete. Der Gegner erwiderte unser Feuer sehr lebhaft, und auf einmal kam von vorne der Befehl: “Verstärkung nach vorne, der Feind macht einen Gegenangriff.” Ich musste mit meinen 6 Mann vor, stürmte los, traf aber unterwegs schon die zurückkehrende Patrouille mit den Gefangenen – die Verstärkung sei nicht mehr nötig. Also wieder zurück. Hpt. Soltau verhörte die Gefangenen, die bald nach hinten abgeschoben wurden, und nach einer weiteren Stunde Alarmbereitschaft hatten wir den Tag über wieder Ruhe.

In the night of the 17th to the 18th, I was relieved, came to the field guard shortly after one o’clock, and could sleep until early at 6 o’clock. Everything was alerted. A violent patrol came to pass. Lt. Hegermann, Lt. Störzel, who had been summoned the day before, and still a few other officers lead the affair. Artillery, mines, and mortars cordoned off the English trench, the patrol pushed forward, pulled the wire, and returned with a non-commissioned-officer and six men as prisoners. We ourselves lost Lt. Störzel (2) as dead and several wounded. The enemy repulsed our fire very vigorously, and suddenly the command came from the front: “Reinforcements forward, the enemy is making a counter-attack.” I had to go forward with my 6 men, storm, but on the way I met the returning patrol with the prisoners – the reinforcement was no longer necessary. So back again. Soltau interrogated the prisoners, who were soon shuffled off to the rear, and after a further hour on high alert, we had the rest of the day.

In der Nacht vom 18. zum 19. November musste ich um 1 Uhr nach vorne zur Ablösung. Die Nacht war ruhig, es fiel fast kein Schuss. Am 19. früh 9 Uhr, während wir im Gruppennest standen, bemerkte ich 2 Engländer an ihrem Drahtverhau. Am hellen Tage gingen sie aufrecht herum – für uns unfassbar. Ich beobachtete sie eine Zeitlang und vertrieb sie dann durch ein paar Schüsse.

In the night from the 18th to the 19th of November, I had to move forward at 1 am. The night was quiet, there were almost no shots. On the morning of the 19th, at nine o’clock, while we were standing at the group nest, I noticed two Englishmen at their wire entanglement. In the bright of the day they walked upright – for us incomprehensible. I watched them for a time, and then drove a few shots through them.

Mittags um 12 Ich war unruhig geworden, verliess mich nicht auf meinen Posten, sondern passte selbst auf und sah wieder 5 Mann am Draht herumlaufen. Ob sie die von unserer Patrouille gesprengte Lücke besichtigen oder ausbessern wollten oder was sonst, ich wusste es nicht. Ich alarmierte meine Leute, und wir gaben eine ruhig gezielte Salve ab, worauf sie verschwanden. Ich meldete den Vorfall sofort nach hinten.

At 12 o’clock I was restless, did not leave my post, but took care of myself and saw another five men running around the wire. Whether they wanted to see or repair the gap exploded by our patrol, or what else, I did not know. I alerted my people, and we gave a quiet salvo, whereupon they disappeared. I immediately reported back the incident.

Um 6 Uhr abends am 19. zogen wir wieder auf Posten. Bald kam der Feldwachhabende, Vizef. Sörensen und meldete mir, hinten sei alles

At 6 o’clock in the evening on the 19th, we moved back to the post. Soon came the field guard on duty, Senior NCO Sörensen (3), and told me, that everything behind was

in allerhöchster Alarmbereitschaft.

in very high alertness.

Beobachtungen und die Aussagen der Gefangenen liessen vermuten, dass für den kommenden Morgen ein grosser Angriff bevorstände. Die Gräben seien voll, alle Reserven seien herangezogen, auch alle höheren Stäbe etc. seien weit nach vorne geschoben. Dabei gab er mir gleich Instruktion, bei einem Infanterie-Angriff unbedingt zu halten, bei Artillerie-Feuer mich langsam zurückzuziehen. Na, dachte ich, denn man los! Aber die Nacht auf den 20. verlief wieder absolut ruhig. Um 1 Uhr wurde ich abgelöst und fand die Feldwache dicht an dicht besetzt. Hptm. Christiansen, der unsere Kompagnie übernehmen sollte, Lt. Simon und viele Leute hatten jeden Winkel dicht besetzt. So gut es ging, hockte ich mich mit meinen Leuten irgwendo hin zum Schlafen.

Observations and the statements of the prisoners suggested that a major attack would take place on the coming morning. The trenches were full, all the reserves were drawn up, and all the higher staff, etc., were pushed far forward. At the same time, he gave me the instruction, to hold on to an infantry attack, to retire slowly with artillery fire. Well, I thought, because you go! But the night on the 20th proceeded perfectly quiet again. At 1 o’clock I was relieved and found the field guard closely packed. Captain Christiansen, who was to take over our company, Lt. Simon, and many people had crowded [into] each corner. As best I could, I crouched with my people to sleep.

Am 20. früh 6 Uhr alles raus, gefechtsbereit, Handgranaten, Munition, etc. …

On the morning of the 20th at 6 o’clock everything went out, ready at hand, hand grenades, ammunition, etc. …

Ich arbeitete Schützenstände aus, damit für den Fall eines Angriffs jeder Mann Licht- und Schussfeld habe. Es blieb alles ruhig. Um 7 Uhr hiess es, die Alarmbereitschaft sei zu Ende, die Leute könnon zur Ruhe gehen. Ich sprach mit Vizef. Sörensen, na, nun sei es hell, und es sei nichts mehr zu befürchten, es sei wieder mal blinder Alarm gewesen. Da, mitten im Satze – das werde ich wohl nie vergessen – wie ein einziger dauernder riesiger Blitzschlag in allernächster Nähe ein schlagartiger Angriff riesiger Artilleriemassen. Alle Schüsse sausten über uns hinweg, gingen in unsere vorderste Linie und weiter nach hinten zu unseren Reserven und zur Artillerie. Ich sah nach hinten. Es war, als sei Weltuntergang, ein furchtbares Krachen und Sausen; der ganze Horizont war, trotzdem es schon hell war, blutig rot von den platzenden Granaten, berstenden Schrapnells. Im Nu wurde durch diesen schlagartigen Angriff hinten alles zusammengeschossen, – es feuerte eine Unzahl Geschütze gleichzeitig und so andauernd, wie ich nie vorher gehört. “Aha,” sagt Sörensen, “das ist die Vergeltung.” “Nein,” sage ich, “das ist viel mehr, das ist der Angriff!”

I worked at gunnery stations, so that in the event of an attack every man had light and a shooting area. Everything remained quiet. At 7 o’clock it was said that the alert was over; the people could go to rest. I spoke with Senior NCO Sörensen, well, now it was bright, and there was nothing to fear, it was once again a blind alarm. There, in the middle of the sentence – I shall never forget – like a single giant lightning bolt in the immediate vicinity, a sudden strike of giant artillery. All the shots rushed over us, went into our front-most line, and farther back to our reserves and artillery. I looked back. It was as if there was an end of the world, a terrible crash and a whirl; the whole horizon was still bright, blood-red from the exploding shells, bursting shrapnel. In an instant, this sudden attack brought everything back to the ground, firing an immense number of guns at the same time, as I never heard before. “Ah,” said Sörensen, “that is the retribution.” “No,” I say, “that is much more, that’s the attack!”

Unsere Leute waren von selbst alle heraus und auf ihren Ständen. Das riesige, nicht zu überbietende Trommelfeuer hielt an; aber auf uns, die wir so weit vorne lagen, fiel nicht ein Schuss. Plötzlich liefen von vorn auf uns Leute zu. Unsere M.G.’s setzten mit rasender Schnelligkeit ein. “Halt, halt!”, brüllte ich, “das sind ja unsere!” Unsere Wachtposten von vorne kamen an, Sörensen stoppte unser M.G.-Feuer und die Leute kamen richtig zu uns in den Graben.

Our people were by themselves all out and on their [firing] stands. The huge barrage [drum-fire], which was not to be surpassed, continued; but not a shot fell on us, who were so far ahead. Suddenly people came running towards us. Our machine guns set in with rapid speed. “Stop, stop!” I yelled, “these are ours!” Our guard posts came from the front, Sörensen stopped our machine gun fire and the people came to us right into the trench.

Wir standen und warteten. Nichts als das andauernde ungeheure, fürchterliche Bombardement nach hinten. Ich bereitete mich auf mein Ende vor; denn dass nach dieser kolossalen Vorbereitung ein gewaltiger Stoss erfolgen würde, war mir gewiss. Die 3 Jahre Krieg zogen blitzschnell in Gedanken vorbei, – na, und dann stand ich da: schussbereit, totbereit. Alles war ruhige. Entschlossenheit, kalte Vernunft, zielbewusste Energie.

We stood and waited. Nothing but the protracted, tremendous, terrible bombardment to the rear. I prepared myself for my end; because after this colossal preparation, a tremendous blow would take place, I was certain. The three years of war passed quickly, and then I stood there, ready to shoot, ready to kill. Everything was quiet. Determination, cold reason, purposeful energy.

Das Feuer liess nicht nach, es lag dauernd in unerhörter Stärke hinter uns. Der Engländer musste hunderte Geschütze aufgefahren haben, die ohne Pause das entsetzlichste Trommerlfeuer unterhielten.

The fire did not stop; it was always behind us, in unheard of strength. The Englishman had had to take hundreds of guns, which kept the most terrible barrage fire [drum fire] without pause.

Da tauchte vor uns aus Nebel und Rauch etwas Dunkles auf.

Then darkness, fog and smoke appeared in front of us.

Ich sah etwas Grosses Schwarzes. “Das ist ein Tank” sagt Sörensen so ruhig wie nur was. Wahrhaftig, jetzt erkenne ich es auch. Langsam aber sicher schiebt sich das Ungeheuer feuernd und krachend auf uns zu, entsetzlich wie ein unabwendbares Verhängnis. Unempfindlich gegen Kugeln und Handgranaten, ist es nur durch Artillerie-Volltreffer zu vernichten. Es kommt näher, vielleicht 50 Schritt noch! Ueber uns, ganz, ganz niedrig, kreisen die Flieger und bestreichen uns mit M.G. Hilfe von hinten ist ausgeschlossen -: durch solch ein Sperr- und Vernichtungsfeuer kommt kein Hund lebendig!

I saw something large and black. “This is a tank,” says Sörensen as quiet as that. Now I also truly recognize it. Slowly but surely, the monster is firing and crashing toward us, terrible as an inevitable doom. Immune to bullets and hand grenades, it is only to be destroyed by artillery hits. It comes closer, maybe no more than 50 paces! Above us, all, very low, airplanes circle and spread machine gun fire. Help from behind is impossible -: by such a block and destructive fire no dog comes [out] alive!

Da, jetzt endlich ist es Zeit! In dichten Massen schreiten aufrecht hinter dem Tank, der sie völlig schützt, die Engländer. Aber der geht an uns vorbei, mehr nach links, er geht geradezu seitlich an uns vorbei, so dass wir die Massen dahinter flankierend fassen können. Natürlich, der Tank geht parallel mit unserem Graben direkt auf unsere Hauptstellung zu.

Da, jetzt endlich ist es Zeit! In dichten Massen schreiten aufrecht hinter dem Tank, der sie völlig schützt, die Engländer. Aber der geht an uns vorbei, mehr nach links, er geht geradezu seitlich an uns vorbei, so dass wir die Massen dahinter flankierend fassen können. Natürlich, der Tank geht parallel mit unserem Graben direkt auf unsere Hauptstellung zu.

There, now finally it’s time! In dense masses, the British are standing upright behind the tank, which protects them completely. But it goes past us, more to the left; it goes to the side of us, so that the masses behind it can be flanked. Of course, the tank goes directly to our main position parallel to our trench.

Nun, wir schossen, so lange wir Munition hatten. Bald war der Tank links an uns voruber, die englische Infanterie also vor uns. Gruppenweise kamen sie auf uns zu. Ich nahm mir einen ihrer Führer, der sie mit der Hand auf uns zu dirigierte, aufs Korn. Hinter uns lag noch immer das furchtbare Artilleriefeuer, von dem wir glücklicherweise garnichts abbekamen; rechts zog sich der Graben nach unserem Gruppennest. Langsam rückten wir alle in dieser Richtung vor, immer im Graben entlang und feuernd. Neben mir schrien Verwundete auf. Wir bekamen jetzt starkes Infanteriefeuer. Ich liege auf dem Grabenrand, ziele und schiesse dauernd; da fällt neben mir Sörensen herab; Schuss in die Schädeldecke. Kein Ton, kein Laut. Er wird blau im Gesicht, das Haar raucht vom warmen Blut. Nun denke ich, einer nach dem anderen, heraus kommt hier keiner.

Well, we shot as long as we had ammunition. Soon the tank was on our left; the English infantry before us. They came to use in groups. I took [killed] one of their leaders, who directed them to us with his hand. Behind us still lay the terrific artillery-fire, which we were fortunate not to mention; to the right, the trench moved to our group nest. Slowly we all advanced in this direction, always along the trench and firing. Beside me, the wounded cried. We are now given strong infantry fire. I am lying on the edge of the ditch, aiming and shooting; Sörensen falls next to me; shot in the cranium. No sound, no sound. He becomes blue in the face; the hair fumes of the warm blood. Now I think, one by one, no one comes out here.

Bald hatten wir

Soon we had

keine Munition mehr.

no more ammunition.

Vor uns links bewegte sich der Tank vorwärts und ihm nach die Massen des Gegners; hinten lag dauernd das unheimliche Trommelfeuer, vor uns kam der Gegner in Gruppen heran. Wir zogen uns nach rechts, also nach vorne zu, weiter. So kamen wir bis fast ans Gruppennest. Auch hier bereits alles voll vom Gegner. Unsere Munition war ja verschossen. Da, ein Ruck – und ein leichter Schmerz an der rechten Schulter…

In front of us, on the left, the tank moved forward, and after him the masses of the enemy; in the rear was the eerie barrage [drum] fire, before us the enemy came in groups. We moved to the right, so forward. So we came almost to the group nest. Here too, everything is full of the enemy. Our ammunition was gone. There, a jerk – and a slight pain on the right shoulder …

In unserem Löchern sassen Gruppen des Gegners, die uns mit der Pistole in der Hand den Weg in ihren Graben wiesen…

There were groups of our opponents in our holes, who pointed at us with their pistols in their hands…

*

Ein anderer Kamerad, Dr. Caspary, Stettin, hat die Tankschlacht bei Cambrai beim Inf. Regt. 50 mitgemacht (S. Regt. Gesch. S. 280). Er geriet mit seinen Leuten in die Gewalt der Engländer und wurde in einem der bekannten “Nester” gefangen gehalten, die eine Spezialität der Engländer waren. Kam. Dr. Casparys Plan, mit den Seinen weider Verbindung aufzunehmen, gelang – wie er selbst berichtet – vornehmlich durch die Kaltblütigkeit eines seiner Krankenträger. Zwar war die Situation mehr als schwierig, allein um so schöner der Erfolg, als er ausser der Befreiung noch die Gefangennahme von 3 englischen Offizieren, 46 Mann und 2 Maschinen-Gewehren einbrachte.

Another comrade, Dr. Caspary, Stettin, participated in the tank battles at Cambrai at the 50th Infantry Regiment. He fell into the hands of the British with his men, and was imprisoned in one of the well-known “nests”, which were a specialty of the English. Comrade Dr. Caspary’s plan to connect with his two partners was, as he himself reports, chiefly due to the cold-bloodedness of one of his patients. The situation was more than difficult, but it was all the more successful when, besides the deliverance, he brought in as prisoners three English officers, 46 men, and two machine guns.

______________________________

I’ve been unable to find any record “Carl Anker” – or even an approximation of his name – in Yad Vashem’s Central Database of Shoah Victims Names. This would suggest, though not definitively confirm, that he was able to escape Nazi Germany and perhaps German-Occupied Europe, “in time”. To where, and when, is unknown.

What happened to him after 1937?

Notes

(1) See the issue of June 24, 1938, which includes coverage of the Evian Conference (as did three issues in July), and – on the first page – an illustrated article about the commemoration of a memorial to French Jewish soldiers fallen at the Battle or Verdun.

(2) “Lt. Storzel” was probably Leutnant Georg Storzel, who is listed as having been killed on November 18, 1917. He is buried at Kriegsgräberstätte in Neuville-St.Vaast (France), Block 1 Grab 516.

(3) “Sorensen” was probably Offiziersstellvertreter Friedrich Sørensen. He was born in Haderslav, Denmark, on October 25, 1889.

These men were identified from reference works (listed below) available at denstorekrig1914-1918.

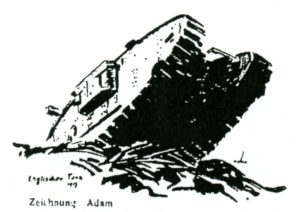

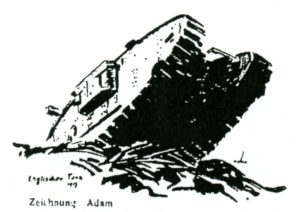

The three images of displayed above are scans of photocopies made at the Dorot Jewish Division of the NYPL, Photoshop-“ed” for clarity. Ironically, the quality of these images – derived from a physical media: paper, from a plain ‘ole microfilm photocopier – is better than that of the PDF available via the Goethe University’s Website. Notably, the article is appropriately headed with a sketch of a British Mark I tank (drawn by “Adam Zeichnung” and…simply and aptly labeled as “Englisher Tank ’17”) advancing over the lip of a trench.

Some other German Jewish military casualties on March 20, 1917 include…

– .ת. נ. צ. ב. ה –

Hagedorn, Josef, Soldat, Garde-Schutz Bataillon 2

Born in Padberg 6/28/97 / Resided in Giershagen

Casualty Message (Verlustmeldung) 820

Die Jüdischen Gefallenen des Deutschen Heeres, Deutschen Marine und der Deutschen Schutztruppen 1914-1918 – Ein Gedenkbuch – page 314

Rosenthal, Isak, Soldat, Garde Regiment 11, Bataillon 3, Kompagnie 9

Born in Beuthen (O.S.) 1/7/88 / Resided in Bitschin / Gleiwitz

Casualty Message (Verlustmeldung) 814

Die Jüdischen Gefallenen des Deutschen Heeres, Deutschen Marine und der Deutschen Schutztruppen 1914-1918 – Ein Gedenkbuch – page 169

Simmenauer (first name unknown), Soldat, Garde Regiment 11, Bataillon 3, Kompagnie 9

Born in Breslau 8/4/95 / Resided in Halle / S.

Casualty Message (Verlustmeldung) 814

Die Jüdischen Gefallenen des Deutschen Heeres, Deutschen Marine und der Deutschen Schutztruppen 1914-1918 – Ein Gedenkbuch – page 182

Westheimer, Heinrich, Soldat (Landsturmrekrut), Reserve Infanterie Regiment 263, Bataillon 3, Kompagnie 10

Born in Grosseicholzheim 2/19/81 / Resided in Grosseicholzheim

Kriegsgräberstätte in Neuville-St.Vaast (Frankreich), Block 9, Grab 315

Casualty Message (Verlustmeldung) 851

Die Jüdischen Gefallenen des Deutschen Heeres, Deutschen Marine und der Deutschen Schutztruppen 1914-1918 – Ein Gedenkbuch – page 230

References

Books

Banks, Arthur, A Military Atlas of the First World War, Leo Cooper (Pen & Sword Books), Barnsley, South Yorkshire, England, 2001.

Chamberlain, Peter, and Ellis, Chris, Pictorial History of Tanks of the World 1915-1945, Galahad, Books, Harrisburg, Pa., 1972.

Die Jüdischen Gefallenen Des Deutschen Heeres, Deutschen Marine Und Der Deutschen Schutztruppen 1914-1918 – Ein Gedenkbuch, Reichsbund Jüdischer Frontsoldaten, Forward by Dr. Leo Löwenstein, Berlin, Germany, 1932

Erindringsboger tyske regimenter Udgivet under medvirken af Rigsarkivet – Infanterie-haefte 11 – Infanterie-Regiment von Manstein (Schleswigsches) Nr. 84, Oldenburg i.O/Berlin, 1922 / Dansk udgave: Jørgen Flinthom – 2016 (“Memorial Books of German Regiments, Published under the auspices of the National Archives – Infantry – Record Book 11 – Manstein 84th Infantry Regiment“) (denstorekrig1914-1918.dk/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/IR-84-kampkalender-udvidet.pdf) (at Den Store Krig 1914-1918)

Geschichte des Infanterie-Regiments von Manstein (Schleswigsches) Nr. 84, 1914-1918, in Einzeldarstellungen von Frontkämpfern, Band III – herausgegben von Hülsemann, Oberstleutnant a.D., im felde Hauptmann und Komp.-Chef. 6./84 und Fuhrer des II. Bataillons / Revideret udgave: Jørgen Flinthom – 2011 (“History of the Manstein 84th Infantry Regiment, 1914-1918, Volume 3“) (at Den Store Krig 1914-1918)

Geschichte des Infanterie-Regiments von Manstein (Schleswigsches) Nr. 84, 1914-1918, in Einzeldarstellungen von Frontkämpfern, Band IV – herausgegben von Hülsemann, Oberstleutnant a.D., im felde Hauptmann und Komp.-Chef. 6./84 und Fuhrer des II. Bataillons / Revideret udgave: Jørgen Flinthom – 2011 (“History of the Manstein 84th Infantry Regiment, 1914-1918, Volume 4“) (at den Store Krig 1914-1918)

Sønderyjske Soldatengrave 1914-1918 – Sorteret efter efternavn (“Soldiers’ Graves 1914-1918 – Sorted by Surname“) (at Den Store Krig 1914-1918)

Web

Bund jüdischer Soldaten (Home Page – dead link as of 2025)

Bund jüdischer Soldaten (YouTube Channel)

Den Store Krig 1914-1918 (“Danes in the German Army – 1914-1918”)

Der Schild (digital version) (at Goethe University Frankfurt website)

German War Graves (at Volksbund.de)

Reichsbund jüdischer Frontsoldaten (at Wikipedia)

Vaterländischer Bund jüdischer Frontsoldaten (Patriotic Union of Jewish Front-Line Soldiers”)

Yav Vashem – Central Database of Shoah Victim’s Names (at Yad Vashem)

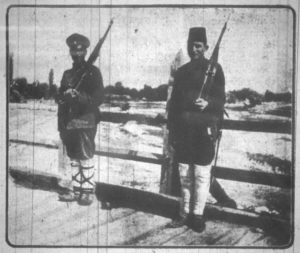

September 16, 1914: “On the frontier between Turkish and Russian territory. Both soldiers on guard are Jews.”

September 16, 1914: “On the frontier between Turkish and Russian territory. Both soldiers on guard are Jews.” February 17, 1915: “A portrait of the Russian Jewish Volunteer, Bogdanoff, who had been awarded the Order of St. George for bravery.”

February 17, 1915: “A portrait of the Russian Jewish Volunteer, Bogdanoff, who had been awarded the Order of St. George for bravery.” April 28, 1915: “S.R. Persitz, who has been awarded a Military Order for bravery.”

April 28, 1915: “S.R. Persitz, who has been awarded a Military Order for bravery.” May 5, 1915: Russo-Jewish Hero: “Jacob Dubov, who received a Russian order for bravery, was killed on the field of battle.”

May 5, 1915: Russo-Jewish Hero: “Jacob Dubov, who received a Russian order for bravery, was killed on the field of battle.” June 2, 1915: Head Doctor: “Samuel Williamovsky, who has attained the highest doctor’s rank in the Russian Field Hospitals.”

June 2, 1915: Head Doctor: “Samuel Williamovsky, who has attained the highest doctor’s rank in the Russian Field Hospitals.” March 8, 1916: “Samuel Mlaver, Russian prisoner of war in Wittenberg.

March 8, 1916: “Samuel Mlaver, Russian prisoner of war in Wittenberg.