There’s a great amount of information about the ordeal and survival of the USS Franklin and her crew on March 19, 1945. This post presents the story of that day as it first appeared in the news media, reported by The New York Times, and appropriately (well, considering the ship’s very name … “Franklin”) the Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia Record, and The Evening Bulletin on May 18, 1945, when news about the carrier’s survival first seems to have “hit the press”. It includes transcripts of the relevant articles published on this date among all three Philadelphia newspapers, and a little from the Times, as well as some of the halftone photos (this being pre-pixel 1945) that accompanied these articles.

But to start, some symbolism in the way of an editorial cartoon from the Bulletin. Better than the fleetingness of “Fame” would I think be “Memory”.

“Enrolled”, by Franklin Osborne Alexander

Philadelphia Bulletin

May 18, 1945

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

“USS Franklin (CV-13) … afire and listing after she was hit by a Japanese air attack while operating off the coast of Japan, 19 March 1945. Photographed from USS Santa Fe (CL-60), which was alongside assisting with firefighting and rescue work. Official U.S. Navy Photograph 80-G-273880, now in the collections of the National Archives.”

As you’ll see as you scroll down through this post, this image appeared “above the fold” on page 1 of the Times, Inquirer, and Record.

“The U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Franklin (CV-13) approaches New York City (USA), while en route to the New York Naval Shipyard for repairs, 26 April 1945. Note the extensive damage to her aft flight deck, received when she was hit by a Japanese air attack off the coast of Japan on 19 March 1945.”

Official U.S. Navy photo 80-G-274014 from the U.S. Navy Naval History and Heritage Command.”

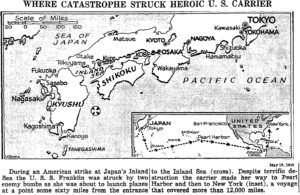

On May 18, 1945, this map accompanied the Times’ articles about the Franklin. Though the map correctly places the carrier’s location on March 19 as east of Kyushu and south of Shikoku, when the ship was struck during the aerial attack, its position was substantially east of that shown here…

… as you can see in these two Oogle Maps. The blue oval shows the position generated by placing the carrier’s reported position – in degrees and minutes – into Oogle Maps’ position locator. (To be specific, 32 01 N, 133 57 E, via Pacific Wrecks.) Here, I’ve replaced Oogle’s “red circle and arrow” with a tiny group of blue pixels (it looks better.) …

…which also appears below, in this view at a far smaller scale.

So, here follow the articles:

Carrier Franklin an Epic of Horror and Heroism

Horror, Heroism In Carrier Epic

The Philadelphia Inquirer

May 18, 1945

(The following story was written by Alvin S. McCoy, of the Kansas City Star, only war correspondent aboard the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Franklin when she was hit by bombs from a Japanese plane March 19 just 66 miles off the coast of Japan.)

By ALVIN S. MCCOY

Representing the Combined U.S. Press

ABOARD THE U.S.S. SANTA FE IN THE WESTERN PACIFIC, March 19 (Delayed) (A.P.) – Japanese bombs struck the huge Essex Class carrier, the U.S.S. Franklin, March 19 off the southern coast of Japan, causing one of the most appalling losses of American lives in our naval history when the carrier’s own bombs and 100-octane gasoline blasted the ship for hours.

SCENES OF HORROR

Scenes of indescribable horror took place on the flattop, a ship almost as long as three city blocks. Men were blown off the flight deck into the sea, burned to a crisp in a searing, white-hot flash of flame that swept the hangar deck, or were trapped in compartments below and suffocated by smoke. Scores drowned in the sea. Other scores were torn by Jagged chunks of shrapnel.

I was the only war correspondent aboard, a dazed survivor of the holocaust only because I was below decks at breakfast at the time in an area that was unhit.

EPIC OF NAVY WAR

The rescue of the crippled carrier, towed flaming and smoking from the very shores of Japan, and the saving of more than 800 men, fished out of the sea by protecting cruisers and destroyers, will be an epic of naval warfare. Heads bobbed in the water for miles behind the carrier. Men floated on life-rafts or swam about in the chilly water to seize lines from the rescue ships and be hauled aboard.

Countless deeds of heroism and superb seamanship saved the carrier and about two-thirds of the ship’s more than 2500 men. The tenacity of the Franklin’s skipper, Captain L.E. Gehres, who refused to abandon it, and the aid of protecting ship and planes virtually snatched the carrier from Japanese waters to be repaired and fight again. Fire and damage control parties who stuck with the ship performed valiantly.

690 REMAIN ABOARD

The carrier was all but abandoned, although the “abandon ship” order never was given. The air group and about 1500 of the crew were sent to the U.S.S. Santa Fe, a light cruiser, which came alongside or were picked out of the sea. A skeleton crew of some 600 remained aboard to try to leave the ship, as it listed nearly 20 degrees. The Franklin’s planes already aloft alighted safely on other carriers. Navy men said the Franklin took more punishment than any other carrier ever received – and still remained afloat. It was her own terrifically destructive bombs and rockets, loaded on planes and decks for a strike against the Japanese Empire that created havoc.

THE PRECISE MOMENT

The Jap plane sneaked in swept across the deck and launched its bombs at the precise moment when they would cause the most destruction. It never has happened before, and probably never will happen again.

The Franklin, one unit of the mighty task force smothering Japanese air power, was participating in her first combat action since last October. Her planes joined the strike against Kyushu Island at the southernmost tip of Japan, March 18. Their first day’s operation ran up a score of 17 Japanese planes shot out of the air, seven destroyed op the ground, and 12 damaged, offset by the loss of four planes and three pilots.

A MENACING SKY

The next morning the Franklin stood 66 miles off Japan. A powerful striking force of planes, loaded with all the munitions they could carry, began launching about 7 o’clock, almost an hour after sunrise. The sky was dull, leaden and overcast, as if glowering forbiddingly. Eight Corsair fighters and eight or nine Helldiver bombers already had roared off the flight deck.

Massed after on the flight deck, engines roaring for the warmup, wings still folded like those of misshapen birds, were more planes – Corsairs, Helldivers and thick-bodied Avenger torpedo planes. Each was loaded with 500-pound bombs, 250-pound bombs, or rockets.

This was the moment, about 7.08 o’clock, that the Japanese plane skimmed in undetected and flew the length of the ship.

OFFICER SEES BOMBS HIT

I was spared seeing the bombs hit. Details were obtained by interviewing witnesses. Standing several thousand yards away on the U.S.S. Santa Fe, Second Lieutenant R.T. Jorvig, of Minneapolis, Minn., Marine gun crew officer, saw the Japanese plane make its run.

“The Franklin Had just launched a Helldiver,” he said, “when I saw the Jap plane, probably a single-engined Jill, coming in. He dived out of an overcast sky at a 30-degree angle, made a perfect bomb run, skimmed about 100 feet over the deck, and dropped his bombs amidships. A great ball of orange flame and smoke shot out of the hangar deck. There were more explosions, and I saw men jumping off the fantail and going down lines.”

22 PLANES SET AFIRE

One bomb crashed through the flight deck forward of the “island” and exploded on the hangar deck below, wrecking the forward elevator. Another big, hole was just aft of the “island” structure.

The initial blast set fire to gasoline and 22 more planes on the hangar deck below, each gassed and armed with bombs and rockets. Instantly the hangar deck became a raging inferno, snuffing out the lives of virtually every man at work on the planes. Bombs and rockets exploded-with shattering blasts.

The crew was not at battle stations. Many men, dog-tired from nights of alarms, had been released to go to breakfast.

One of the tragedies was the long line of line of enlisted men, waiting on the hangar deck to enter a hatch leading to their mess hall below. Presumably all were killed instantly when the white-hot flash swept the deck. Their bodies remained in the area for hours, many with their clothing burned off and even dog tags melted.

ROCKETS ARCH OFF DECK

Fifteen minutes later there was another series of heavy explosions that jarred the carrier to her keel. Planes on the flight deck blew up some minutes after the bomb hit, sending rockets arching off the deck like a giant fireworks, display. Some of the pilots escaped by leaping overboard to swim to destroyers.

The “island” control structure was riddled with shrapnel, killing many men. Lieutenant William A. Simon, Jr., of Wilmington, N.C., an air operations officer, was one of several men who escaped from one compartment.

“The first blast stunned me,” he said. “When I recovered consciousness I had to push some plotting boards and radio equipment off to get up. The deck had buckled and had jammed the hatch. Finally I forced open the hatch enough to push my way through, then went out on the flight deck to help fight fire for about 30 minutes.

“Men were screaming: “Let’s go over the side!” Through the darkness of smoke I saw about 25 jump. Smoke was so thick it was more night than day. Then I realized I had been injured.”

ENGINES SMOLDER

Lieutenant H.C. Carr, Carmel, Calif., member of a Navy torpedo plane squadron, went to the hangar deck about an hour after the first explosion when it had cooled enough to permit fire fighting. Engines smoldered about the deck and the forward elevator had collapsed in its pit.

“When I came out on the deck,” he said, “I saw about 20 bodies burned almost beyond recognition. I had to step over one to get down the ladder. One man actually was hanging by his neck from a rafter, where he had been blown from the deck.”

Below decks, conditions were even worse. Hundreds of crewmen were locked in watertight compartments, the doors having been slammed shut instantly when the ship was hit.

SUFFOCATING SMOKE

Added to the horror of the explosions and the overwhelming fear that the carrier was sinking, while being trapped below decks, was the dense suffocating smoke that filled many compartments. Many died from want of air. A great many more were led to safety by courageous members of the crew wearing rescue breathers. Lines of men crawled on hands and knees through smoke-filled compartments below decks to find egress at some welcome scuttle.

About 150 enlisted men were locked in an after mess hall on the third deck below when their compartment filled with smoke. Choking, they wrapped damp handkerchiefs or towels over their nostrils and waited, praying.

LEADS MEN TO SAFETY

An hour and a half later Lieutenant (j.g.) Donald Gary, of Oakland, Calif., fuel and water officer, entered the compartment. He led to a still lower deck to the engine them out by groups, taking the men room so they might climb out an escape vent to the top deck.

This correspondent, who had left the riddled “island” structure 15 minutes before the bombing, was led out to the forecastle deck with a party of 25 others about 40 minutes after the blasts began. There were 400 or 500 men huddled on the deck. Fear showed in their faces.

FEARS TURN TO SMILES

The remark, “I’ve never been so scared in my life,” became so common that everyone grinned when he heard it. Wounded were carried to the deck on litters and covered with blankets. Everyone donned life-jackets from a pile on the deck, while seamen slashed ropes and dropped life rafts and lines over the side. Then the group stood about, waiting interminable hours for orders.

The public address system was blown out immediately, making communication impossible. Shivering in the chill air, men began wrapping blankets around them, or went into an officers area and helped themselves to coats. For some time the ship made headway at eight knots, then finally stood dead in the water.

HANGS HEAD DOWN IN SEA

One man, sliding down a line at the fantail of the carrier, caught his leg near the water line and hung head down, drowned, dipping under and out of the sea as the carrier rolled in the swells. He hung there for several hours. Destroyers and cruisers circled the wounded flattop protectingly while friendly planes droned overhead.

The fight to save the mighty carrier began immediately, although commanding officers on other ships believed it Impossible. Damage and-fire control parties labored indominately amidships, playing fire hoses on the flames while shrapnel burst around them. Captain Gehres, standing on the bridge at the time, was knocked down by the blast and almost suffocated by smoke. He was uninjured.

“I won’t abandon this ship.” he told his commanding officers.

INSPIRATION TO MEN

Commander Joe Taylor, executive officer, standing on the flight deck, also was floored by the blast. He immediately began fighting fires, jettisoning ammunition, assisting the wounded and visiting various parts of the ship to serve as an inspiration to the men aboard. Lieutenant Commander David Berger, of 224 E. Church Road, Elkins Park, Pa., the ship’s public relations officer, reported.

Each succeeding explosion appeared to make the loss of the ship inevitable. The captain, alone, could make the decision and his faith held fast. Two flag officers aboard shortly were transferred to a destroyer by “Travelers.”

RESCUE WORK BEGINS

Captain Harold C. Fitz, commanding the Santa Fe, was ordered to assume command of the rescue operations within an hour after the bombing. Four destroyers were detailed to assist.

The Santa Fe took some lines and came alongside once, her fire hoses playing on the flaming carrier deck, then cast off when there was doubt whether the carrier’s magazines had been flooded. The carrier rocked with a mighty explosion at the stern about 10 o’clock, three hours after the bombing.

Circling quickly, the cruiser charged in across the bow, turned starboard, and stopped, almost rubbing the carrier’s decks. The wholesale evacuation began as the ships pounded together in the swells.

SPILLS FLAMING FUEL

A broken gasoline line in the after part of the hangar deck spilled flaming 100-octane fuel for several hours, turning that part Into a cauldron of fire. Burning gasoline spilled over the side of the carrier and blazed on the sea below. Fire hoses from the cruiser would not reach this area.

“I as watching and saw three men go into that fire and smoke and shut that line off,” L.E. Blair, of Williamsburg, Kas., chief carpenter on the cruiser, related. “I don’t know who they were, but if those boys are alive, they sure deserve a medal.

He said that 40-millimeter shells were going off “like fire-crackers” and, finally, five-inch shells on one of the after-gun-mounts began exploding, cutting two of the cruiser’s five fire hoses. Flames blazed around the mounts, even coming out of gun muzzles. A final explosion at the stern of the carrier rocked her again about 11’ o’clock, four hours after the attack.

By this time the Franklin was listing so steeply to starboard toward the cruiser that it was difficult to keep one’s footing on the decks. Once the wounded were across, men began scrambling to get aboard the cruiser. Some ran frantically over a projecting radio antenna from the carrier to leap to the decks of the cruiser. Others swung agilely across on lines.

826 TAKEN ABOARD

A catwalk was finally placed between the flight deck of the carrier and the top of one of the cruiser’s turrets. The hundreds massed on the flight deck streamed across until the crowd seemed to melt away. Within two hours and a half the Santa Fe had taken 826 persons [and picked] up 212. Scattered among seven ships were more than a thousand of the Franklin’s officers and crew. Still others had landed on various carriers of the task force.

Just before 12.30 o’clock, five and [half hours later, a Japanese] plane slipped through the protecting air patrol and made a bomb run on the carrier. Its bombs sent up a geyser of water at the stern of the ship only 30 minutes after the transfer of personnel was completed. Survivors aboard the Santa Fe, still clinging to lifejackets and steel helmets, dashed below decks as the anti-aircraft fired.

Two hours later another Jap plane appeared in the skies, but did not make a bomb run. Both were reported shot down by protecting combat air patrol planes, as was the Japanese plane which bombed the carrier.

The tortuous tow picked up speed gradually to put nautical miles between it and the Empire. The impossible was happening. The unsinkable Franklin was heading toward safety almost from the shores of Japan.

HAZARDOUS RESCUE

The rescue of the Franklin, and the saving of more than 800 of her crew, provided one of the most amazing epics in American naval history.

Hazards of the rescue work were well known to Captain Fitz, commanding the Santa Fe. If the magazines blew up, his own ship would be hurt. To tie up, dead in the water, gave a perfect target for land-based Japanese planes only minutes away. But several thousand lives were at stake in the event the Franklin went down. Captain Fitz did not hesitate.

Lines were shot to the Franklin, even as a terrific explosion shook the Franklin’s stern. The cruiser, small by comparison, appeared to stand only half the length of the enormous carrier. The first wounded man was received on the cruiser at 10 o’clock, crossing the water gap on a stretcher swinging on the lines, three hours after the bomb hit.

Fifteen minutes later the Santa Fe lost her position on the Franklin. As the lines were cut, consternation showed on the faces of the men on the sloping carrier decks.

The Santa Fe circled the Franklin. Captain Fitz came in cutting across the carrier’s bow at 25 knots, turned hard to starboard, and stopped his ship abruptly, her engines reversed, exactly alongside the carrier. He kept his engines going, forward and in reverse, to maneuver. Every sailor who saw the approach marveled at the seamanship, and it was long the talk of the rescue.

The two ships pounded together in the swell and men immediately began leaving from the main deck of the Franklin to the forward six-Inch gun turrets of the cruiser.

DAMAGED BY CARRIER

Meanwhile another cruiser, the U.S.S. Pittsburgh, picked up some survivors from the water, then approached and cast a line to the Franklin.

The Santa Fe was pounded unmercifully by the carrier’s 40-milll-meter gun mounts and other projecting equipment. Her starboard rails were clipped off, her hull ripped, and a gun was damaged. But she held fast.

Sailors on the Santa Fe gave up their bunks and clothing to survivors from the Franklin. One sailor came aboard wearing ad admiral’s life jacket. Another was wearing a commander’s coat. Completely fagged out, many lay down and quickly fell asleep. It had been five hours of constant fear before I boarded the cruiser.

CLING TO LIFE-JACKET

In the wardroom, virtually every officer from the Franklin continued wearing his life-jacket and steel helmet as items too precious to abandon.

They wore them even while eating.

Everyone kept saying, “I’m glad to be aboard.”

What they really meant, and admitted, was, “I’m glad to be alive.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Carrier Franklin is Home after Bombing Ordeal off Japan with 832 in Crew Dead or Missing

Philadelphia Bulletin

May 18, 1945

(Eyewitness account of the blasting of the Franklin appears on Page 4.)

By The Associated Press

Washington, May 18 – The aircraft carrier Franklin, which miraculously survived one of the severest ordeals of this or any war, is home. She came home, sadly crippled but under her own power, her charred and battered hull manned by a gallant crew of survivors.

Now undergoing repairs at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, she will resume her place in the war against Japan.

Until now, Japanese radio propagandists never knew how close they came to being right when they boasted that the 27,000-ton vessel of the Essex class had been sunk. Without incredible stamina and strength built into her and without the superhuman courage of her personnel, their claim might easily have been true.

As it was the carrier suffered 1,102 casualties – 833 killed and missing and 270 wounded – more than one-third of her total complement.

Jap Scored Direct Hits

Chance played into the hands of the lone enemy dive bomber that streaked suddenly out of the clouds within 60 miles of the Japanese coast on the morning of March 19.

Two 500-pound armor piercing bombs were dropped on the Franklin, which was operating as part of a fast carrier task force in the strike against remnants of the Japanese fleet in Japan’s Inland Sea, Nippon’s “private lake”.

Released from low altitude, both bombs scored direct hits. One exploded beneath the flight deck, on which armed planes were ready for take-off. The other went off on the hangar deck, where other planes, fueled and armed, were waiting to be taken to the flight deck.

The attacking plane was shot down a moment later, but the bombs, exploding where they did, started a train of fires and explosions which for hours were to rend and torture the vessel.

Fires Spread

Large bombs burst and hurled men and planes the length of the ship. Smaller bombs, rockets and machine gun ammunition killed dozens who had survived the major explosions. Spreading fires, fed by thousands of gallons of high-test aviation gasoline, added fury to the holocaust.

But, without panic, those who miraculously had escaped death or injury and the slightly injured moved in to fight the fires. Volunteers, including pilots, mechanics, officers and stewards, took over the job eft regularly assigned damage control parties who had been killed or trapped by flames.

Among those especially sighted by the Navy’s account were the ship’s chaplain, Lieutenant Commander Joseph O’Callahan, Boston, and Lieutenant (jg) Donald A. Gary of Oakland, Calif., both of whom performed superhuman feats of bravery.

Braved Flames

The lean, scholarly Jesuit first moved around the burning, slanting and exposed flight deck administering last rites to the dying. Then he led officers and men into the flames, risking momentary death, to jettison hot bombs and shells. Then he recruited a damage control party and led it into one of the main ammunition magazines to wet it down and prevent an explosion.

The Franklin’s captain, tall, husky Leslie E. Gehres, of Coronado, Calif., who calls Father Timothy “the bravest man I’ve ever known,” himself diplayed a brand of courage that saved his ship under conditions that threatened to kill every man aboard.

Captain Gehres refuted flatly lo order the ship abandoned, declaring: “A ship that won’t be sunk can’t be sunk.”

A few hours after the first attack, the light cruiser Santa Fe came alongside to remove the wounded. These operations were Interrupted, however, when one of the carrier’s forward five-inch gun mounts caught fire and threatened to explode.

Later, after the cruiser’s mercy mission had been completed, survivors of the carrier air group were ordered to leave the ship. Early in the afternoon, after the fires were under control, the Franklin was taken In low by the heavy cruiser Pittsburgh.

Constant Patrol Above

Overhead, fighters flew a constant patrol. By the next morning one of the carrier’s fire rooms had resumed operation and her severe list had been corrected. During the day, more power was recovered and the canter worked up a speed of 23 knots under her own power. On the second day after the attack, 300 of her men were brought back aboard from other vessels which had picked them up, and she headed for home.

Her foreman a jagged stump, her mainmast bent at a sharp angle and her flight deck completely destroyed, the battered, burned carrier limped gallantly into New York on April 26 after a 13,400-mile voyage.

Third Naval District officials said she had lost a greater number of men and sustained more battle damage than any ship ever to enter New York Harbor under her own power.

Her steel decks were buckled and torn in scores of places.

“704 Club” Organized

The Franklin was brought home by 704 resolute Americans who refused to abandon her. They formed the “704 Cub” and agreed to meet after the war ends.

Captain Gehres told how his “704 Club” worked furiously on the way home to make at many repairs as possible.

“While we were coming to New York,” he related, “the hangar deck was cleared and swept down. That saved the Navy Yard two month’s work and probably saved the Government $200,000 in labor charges.”

“She should be taken on a tour of the United States, if that were possible, to show people back home what one or two tiny enemy bombs can do, for that was what started this,” said Marine Corps Major Herbert Elliot, of Pueblo, Colo., of the Franklin’s detachment.

The Franklin, built by the Newport News, Va., Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co, was launched October 14, 1943. and commissioned January 31, 1944.

Was Damaged Before

The Inland Sea action was the second in which the Franklin suffered damages requiring her return to the United States. Last October 14, anniversary of her christening by Captain Mildred McAfee, WAVE director, she was attacked by four Japanese torpedo planes while participating in a two-day strike at Formosa.

She escaped major damage then, but a few days later, at the battle for Leyte Gulf, she took a direct hit on the flight deck. That damage necessitated a return to the Puget Sound, Wash., Navy Yard for repairs. She had just returned to action when the latest attack occurred.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

772 Lost on Blazing U.S. Carrier Hit by Japs Mar. 19, but Ship Is Saved

Philadelphia Record

May 18, 1945

Franklin Rocked by Blasts From Arsenal, Fights Attackers 3 Days and Returns in One of War’s Great Episodes

Philadelphia Record – New York Times Foreign Service

The new 27,000-ton carrier Franklin, a scarred and blackened hull, with fire-crisped decks where hundreds of men died in one of the ugliest naval catastrophes of the war, has reached the Nary Yard in Brooklyn, proudly completing her ghastly 12,000-mile voyage under her own power, in a great display of seamanship and valor.

Releasing stories written weeks ago, the Navy paid tribute today to the ship and her men, the dead and those who survived. More than 1000 were lost or injured, representing roughly a third of her complement, believed the greatest loss of any ship in this war. The official casualty list reports 841 dead, 481 missing and more than 300 wounded.

Joined in Land-Sea Attack

Hit at 7:07 A. M. on March 19, some 60 miles off the Japanese main islands as the fast carrier task force blasted enemy fleet remnants in the Inland Sea, the Franklin became a raging inferno of fire and explosion, and remained so for hours. As she was dispatching planes from her deck, she took two bombs, one forward and one aft.

A lone Japanese dive-bomber, penetrating defense screens, sped over the ship from stem to stem, planting the heavy bombs accurately.

Instantly, the planes on the deck burst into flame, their machine guns firing, their bombs going off. Ready bomb stores exploded and down below, one by one, sections of the ship blossomed into flaming death traps. Rockets were zooming in yellow flashes across the deck. High-octane gasoline spewed forth, ran in cascade over the aides, and to watchers with the rest of the fleet the great ship seemed to disintegrate.

Refuses to Abandon Ship

Adm. Marc A. Mitscher, in command of the force, sent permission to prepare for abandoning ship, but the commanding officer, Capt. Leslie E. Gehres, of Coronado, Calif., shook his head.

“We’re still afloat,” he said, and he and his men, as courageous a crew as ever walked a deck, kept her that way.

All day the ship burned, as rescue parties pushed through choking- smoke, leading trapped men to the decks. Others jumped over or were blown into the sea. Some men were brought out alive 18 hours later from a steaming compartment below aft.

Other warships, the cruiser Santa Fe and the destroyers Hunt and Marshall, stood alongside to give aid, taking off wounded or furnishing their own fire-lines to the floating inferno. Other ships fought off several Japanese air attacks that day and the next.

Controls Gone – Heads for Japan

With her controls gone and her men ordered out of the engine rooms, the big carrier steamed slowly ahead for more than an hour and a half, heading for Japan. And the Fanta Fe, not knowing whether the magazines had been flooded, clung closely by, bumping and crushing her rails, so close that men crawling out on the Franklin’s listing side could fall, as some helpless ones did, into the waiting arms of the Santa Fe’s crew.

Then the cruiser Pittsburgh took her in tow, for a while, until gallant men, knowing what they faced below, went down into the furious boiler and furnace compartments and finally got some of them working. Finally the ship could make headway and maneuver by using the engines.

Rescue Parties Formed

Other men led rescue parties through choking room into compartments where men were huddling without air.

All day the great ship blazed and burst with powder, gasoline and shell, until, as night deepened, the weary officers and men, burned and hungry, brought a semblance of control into the ship that would not sink. Her engine power was stepped up by further repair parties, and she went for home the next day, stopping at Pearl Harbor the first week of April. Then she headed across the Pacific at good speed, like a ghost ship, with a little band of musicians holding forth on the deck, most of them with home-made instruments.

In commission only a little more than a year, the Franklin was not, the Navy stated yesterday, one of the ‘“hero ships.” She had participated in attacks against Japan’s weakening sea power and had done her share, though too young to win the rich laurels worn by her more experienced sisters.

Joins Ranks of Heroes

“But in her hour of travail,” the Navy announcement said, “the American men, young and not so young, who comprised her crew, wrote another bright paragraph in the lone story of naval heroism at sea. The kind of fight they waged to save their ship is typical of what their fellow-seamen have frequently done during the Pacific war.”

The Japanese the next day announced that a big carrier had been sunk. And this time the enemy boast was not unbearable, for the ship by all standards was done, and should be today In the Pacific depths.

Naval officers and others who have seen her, blackened, with holes gaping and her compartments formless masses of twisted steel, expressed wonder she stayed afloat. That she did, they say, was a tribute to high order, to men whose courage and determination would not let her go, and to the designers and builders who put together a stanch vessel able to take unbelievable punishment and still make if home.

She was built by the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, launched in October, 1943, and commissioned the following January.

Priest a Hero

The outstanding hero, according in Capt. Gehres, was a 40-year-old Jesuit priest, Lieut. Comdr. Joseph Timothy O’Callahan, USNR, of Cambridge, Mass, ship chaplain, and, said the captain fervently, “the bravest man I have ever seen.”

Formerly head of the mathematics department at Holy Cross College, Worcester, Mass., a bespectacled, scholarly man with membership in a number of learned societies, Chaplain O’Callahan has been in the Navy since 1940, but Joined the Franklin only 17 days before she was hit.

“Father O’Callahan,” said Capt. Gehres, “was every place, and every place was the toughest. He set up the first receiving station for the wounded and helped the medical corpsmen. He was giving the last rites of the church to badly wounded and went around encouraging men fighting fires. I would look down from the bridge to the deck and see him leading the way into dense smoke clouds. He would reappear and take more men in.

Near Explosion

Once an explosion came right where he stood, and a man on his left was killed. Father O’Callahan came out of it okay. Without hesitating, he took the man on his right and went ahead fighting fire.

“He made several trips below decks as the ship reeled with explosions and turned crisp from the terrific heat. He helped wet down explosives in a magazine, and in another, helped pass out ammunition for Jettisoning. When the crisis was over he led men below for bodies, preparing them for burial.”

Another singled out by the captain was Lt. (J.G.) Donald A. Gray, USN, commissioned two years ago after more than 20 years as an enlisted man.

Attacked East or Inland Sea

Capt. Gehres said the attack occurred at 7.07 A.M. March 19, about 63 miles east of the Japanese Inland Sea, as the Franklin prepared to launch its planes against the Japanese mainland.

The Franklin’s planes were on the flight deck, loaded with bombs and gas for takeoffs. A Japanese plane came out of the cloud so fast he escaped the Franklin’s guns and dropped a bomb that pierced the deck and exploded below.

“We were heavily loaded with bombs, torpedoes and fighter rockets, and flames shot almost immediately from the hangar deck and enveloped the whole forward flight deck,” said Capt Gehres.

“There was another big explosion and I saw we were hit amidships and two or three minutes later the bombs and gasoline tanks of the planes on the flight deck began exploding.

Explosion Follows Explosion

“From then until almost mid-afternoon there was one explosion after another as the planes and then the magazines blew up.

“We had about 50 tons of bombs, torpedoes and rockets and about 50 tons of other stuff aboard and it all went up,” the captain said.

“The first explosion knocked me down and when I got to the bridge the flames were shooting out of the hangar deck and enveloped the whole forward flight deck.

“All the explosions shook the ship pretty badly and knocked a lot of people into the water. Some of the stuff dropped through to the hangar deck and one explosion killed everyone forward on the hangar deck.

“The smaller stuff, the 20 and :5 mm. machine gun ammunition, was popping around the bridge like strings of firecrackers going off.

Staff Transferred

“About 8 o’clock we transferred Adm. Ralph Davidson and his flag staff to another ship. By that time the men in the engine rooms were collapsing: It was about 130 degrees down there and filled with smoke.

“I told them to set all instruments so we could keep steaming, and get out. We were heading straight for Japan and couldn’t do anything about it because we couldn’t steer, but we had to keep moving.

“We kept right on running for about 45 minutes, although there was nobody in the engine rooms. Then we went dead in the water.

Men Blown Overboard

“Many of the men jumped overboard or were blown over board and some were picked up by other ships. The cruiser Santa Fe had come up and we were transferring the stretcher cases and others who were badly wounded. We got the last of the stretcher cases over about noon. The Santa Fe backed away as the two ships were banging together in the rough seas and causing some damage. We had a list of about 14 degrees. Later the Santa Fe came back and helped fight the fire, even though it was a very dangerous thing for them to do. One magazine blew up and threw the fragments over the Santa Fe’s decks.

“I want to be sure Capt. H.C. Fitz, of the Santa Fe, gets credit for what he did. It took nerve.”

Japs Attack Again

Some time later the cruiser Pittsburgh came alongside but it took four hours to get a tow line secured on the Franklin.

During this operation a Japanese plane attacked again, making a low-level strafing and bombing attack that missed the mark.

By this time the worst of the fires were out but some of the rockets were still exploding. Some of them roared across the decks, killing the people in their paths, and shooting out to sea where they narrowly missed other ships. Many men were killed or injured by them. It was a nightmare.

The Japanese sent out many other planes to “finish off” the crippled Franklin.

One Gun Mount Operating

“There was only one twin gun mount, forward, operating,” said Capt. Gehres.

“Many of the gunners had been killed, but this gun was manned by a Marine orderly, two Marine aviation mechanics, a mess cook, a messenger, a bugler and two gunner’s mates.

“They had to operate the mount by hand, but they swung it around on a Jap that attacked and despite all the handicaps, they forced the Jap off his course and his bombs went into the water, a hundred feet off the stern, without damage.”

During the early hour of the attack Capt. Gehres said the chaplain was everywhere” helping wounded, fighting fires and administering last rite to the dying.

Handles Fire Hose

“I saw him in front of a huge billow of smoke holding a fire hose and encouraging other to go in with him while he extinguished flames,” said the captain. “He didn’t hesitate a moment to go where nobody else would go. I even saw him go into an ammunition magazine where there was a fire.

“There was a man killed on each side of him but he was unhurt. A turret began smoking and I yelled down to get a hose and wet down the ammunition locker before It exploded. The chaplain couldn’t hear me in the noise and he came over and asked what I wanted.

“With Lt. Comdr. McGregor Kirkpatrick, he got a hose and stood there and wet the locker, which might have blown up any moment, killing the both of them.

“After that the chaplain went to another gun mount and started jettisoning ammunition.”

Lt. Gary, assistant engineering officer, was at his boiler emergency station when the attack came. Stifling smoke poured in as he stumbled aft to the mess room where 300 seamen were trapped. He was only a few minutes behind Lt. Comdr. Dr. James L. Fuelling.

The situation was desperate, with ventilation growing worse. Looking around, he noticed an opening in an air uptake, and assuring the men he would return, he started up, returning a few minutes later to help the men out.

First he took 10 men, each of them clasping the hands of others to form a chain. Leaving them on the flight deck, he came back for a larger group, and then a third. The canister on his rescue breather was not functioning, and Lt. Gary was choking. Hearing that men had been trapped in an evaporator room for six hours, be donned another breather and went to lead them out.

It was also Lt. Gary who led two others down into the engine room that that first night to try lighting a boiler. They wore rescue-breathers, for the temperature was 130 degrees. Despite the apparent hopelessness, they did get two boilers going, so the Franklin could make headway. In his “spare” time Lt. Gary was seen single-handedly fighting fire on the flight deck, tirelessly organizing fire parties, repeatedly entering dangerous places.

The last man lo leave the mess compartment from which Lt. Gary found an escape route was Dr. Fuelling. Unable to reach his sick bay battle station, he had taken charge in the compartment where, it was said, his voice of command rose above the excited babble of the men, many of whom were novices at war, experiencing their first action. He ordered them to remain quiet, to atop shouting and to relax. As they waited, the ship shook again and again with great explosions.

Start to Pray

“I tried to distract their minds from what was going on,” the doctor said. “Someone suggested that we pray, and pray we did.”

Almost on the verge of exhaustion himself, the doctor, on reaching the deck, fell to the bloody task of giving aid to men suffering from burns and injuries. He directed evacuation of wounded to the Santa Fe and worked ceaselessly for hours.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

CITY MEN SURVIVED FLATTOP BLAST

Sailor Jumped into Sea Blazing with Gas and Swam to Safety

Philadelphia Bulletin

May 18, 1945

A 22-year-old Philadelphia sailor who saw two of his shipmates killed beside him, escaped from the bombed carrier Franklin by jumping into a sea ablaze with spilled gasoline and swimming underwater until he was out of reach of the flames.

Earlier, Harry Arthur Stinger, pharmacist’s mate third class, of 5826 Akron St., missed death when he went to eat dinner in another section of the ship instead of going to his regular mess room.

A bomb landed in the mess room while he was still eating and killed everyone there, Stinger told his mother, Mrs. Rose Stinger. He was wounded by the same shrapnel bursts that killed one of his companions.

Stinger was one of several Philadelphians who survived the bombing.

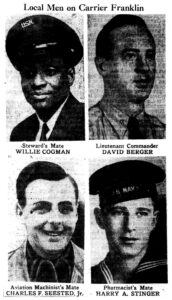

Among the others are Lieutenant Commander David Berger, 32, of 224 E. Church Road, Elkins Park; Charles F. Seested, Jr., aviation machinist’s mate second class, of 449 W. Price St.; Willie Cogman, 30, Negro, a steward’s mate third class, 1412 S. Chadwick St.; Edward G. McGlade, aviation machinist’s mate third class, 402 W. Spencer St., and Michael A. Monte, aviation radioman second class, 3149 N. 23d St.

Stinger, who Is now at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, told his mother that he went to another section of the ship to eat at the invitation of a shipmate.

Things got hot in that section, too. One of the sailors there opened a door just as a bomb exploded overhead, and one of Stinger’s companions was killed in front of him.

Stinger and two other sailors managed to get to the deck by another route, and later the burned bodies of six men were found in the compartment that Stinger and his companions had left. The bodies were on the stairway, indicating that the sailors had made a desperate effort to escape when the compartment caught fire.

Another Companion Killed

On the deck, Stinger and his two companions crawled on their stomachs to avoid bombs. One bomb killed one of the companions. Stinger was struck in the leg by shrapnel.

Despite his injuries, Stinger leaned over to administer a sedative to the fatally injured man and fell over him, overcome by the thick smoke.

He regained his senses and made his way to the railing. Peering into the water, he saw it was a sea of flames. There was no other means of escape, so he plunged overboard into the blazing gasoline and swam under water.

Soon he was out of reach of the flames and came to the surface. Another sailor helped support him, and the two remained in the water 40 minutes until rescued by the cruiser Santa Fe. He was in the Santa Fe’s sick bay six days under treatment for his wounds.

Commander Berger, who was one of the survivors of the aircraft carrier Hornet, sunk in the Battle of Santa Cruz in 1942, said that his experiences aboard the Franklin seemed like a nightmare, by comparison.

Smoke Hid View

Commander Berger related that he was on the bridge of the Franklin on the morning of March 19, standing by the primary flight control, when a terrific explosion shook the ship. He was knocked to the deck.

The concussion knocked him out for a few minutes, and when he regained his senses he was unable to see anything around him because of the acrid black smoke billowing around him

Smoke and flames, he said, seemed to envelop the entire ship, and the subsequent series of explosions almost caused him to lose his grip on the iron rung to which he clung.

Finally he lowered himself by a rope from the bridge to a point four feet above the gun deck. He let go of the rope and fell to the deck. Several other members of the crew did likewise.

Coughing and choking. Commander Berger crawled toward a spot through which he could see the blue sky.

After breathing fresh air he joined other units in fighting the heavy fire that raged through the ship.

The next day was a “living hell,” he said. Enemy planes attacked again and his position on the hangar deck was a very uncomfortable place. He crawled through wreckage and rubble to the flight deck, and tried to crouch behind a five-inch gun only to realize suddenly that the weapon itself was smoking “like the very devil” and seemed ready to explode. He beat a hasty retreat.

Worst Thing Yet

Finally the attacking planes disappeared, and the men went back to their fire fighting.

“The experience on the Franklin was about the worst thing that I have ever gone through,” he said.

He praised Cogman, who was a member of a group of Negro sailors who rigged up the Franklin for towing after the attack. Cogman, he said, did the work of a hero and undoubtedly will receive a Navy award.

Seested, whose wife Ann, lives at the Price St. address, told his story aboard a rescue vessel, and his account was made public by the Navy in Washington.

He said that he had just returned to his work shop, located aft between the flight and hangar decks when the bomb struck. He had just taken off his life jacket for the first time in 36 hours.

Escapes Through Port Hole

“The whole ship vibrated,” he said. “Men were knocked off their feet and everything was a mess. I rushed to my life jacket. By the time I had it on, the shop was filled with smoke. We began to choke, our eyes burned.

“I tried to get out through a hatch on the starboard side, but the second I stepped out, I felt intense heat. I groped my way back to the shop and found a port hole had to remove my life jacket to climb through, then I had to climb down the stern of the ship about 35 feet to reach the fan tail. I did this by letting myself drop twice. I was holding my life jacket in one hand.

“As I reached the fan tail there were two terrible explosions. Wood and metal were flying in every direction. Then another blast occurred. Something hit my head. That’s all I remember until I came to in the water. The ship was a long way off.”

Seested was picked up by a destroyer and was later transferred to the cruiser.

Berger In law Firm

Commander Berger, whose wife, Harriet, lives at the Church Road address, enlisted In the Navy March 15, 1942. At that time he was a partner in the law firm of Woolston and Berger, and be also served with the Alien Registration Commission.

He was graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1932 and from the University’s Law School in 1938. His parents, Mr. and Mrs. Jonas Berger, live in Archibald, Pa.

He also served on the carrier Enterprise and is the recipient of the Presidential Unit Citation.

Seested, who is 25, entered the service in May, 1943, while employed at the Bendix Aviation Corp. On April 26, his wife received word that he had been seriously wounded. He was graduated from Waltham, Mass, High School and is now awaiting an operation at a San Diego Naval Hospital according to word received by his wife last week.

Cogman was inducted October 21, 1943. He has a daughter, Catherine, 11, who is staying with his sister, Mrs. Williernae Mitchell, at the Chadwick St. address.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Crew Rescued After Praying

The Philadelphia Inquirer

By ALVIN S. McCOY

May 18, 1945

ABOARD THE U.S.S. SANTA FE IN THE WESTERN PACIFIC, March 19 (Delayed) – At least 150 enlisted men, who were trapped in the smoke-filled mess hall on the U.S.S. Franklin after the huge Essex Class carrier had taken a direct Japanese bomb hit, testified today that their prayers were answered by Divine Providence, and a lieutenant.

The survivors were tolling their mates of the frantic hour and a half they spent below decks on the Franklin, waiting for- someone to show them a way out.

“A doctor was with us,” said B.J. Moore, Seaman First Class, Claremore, Okla., “and he, really took care of us. He was Lieutenant Commander J.L. Fuelling, of Indianapolis. He said, “If anyone knows any prayers, he’d better say them.”

BOW IN SILENT PRAYER

The men bowed their heads and prayed, silently.

In a few minutes the door opened and in came Lieutenant J.G. Donald Gary, of Oakland. Calif., fuel and water officer. He told them he believed he could find a way but. He would try it first and then return and lead them.

About twenty minutes later Lieutenant Gary returned, took ten men with him crawling on their hands and knees through water. They went down a ladder-to the engine room a deck below, and then climbed up through an escape vent.

The remaining men said prayers again. Lieutenant Gary returned and escorted ten more out the devious passageway. There were more I prayers, the lieutenant returned, and the entire remaining group departed, each man crawling and holding the belt of the man ahead.

“It seemed like every time we prayed, somebody came in that door,” Seaman Moore said.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Jazz Concert For Survivors

The Philadelphia Inquirer

May 18, 1945

WASHINGTON, May 17 (U.P.) Survivors of the Japanese bombing attack which almost sank the aircraft carrier Franklin were treated to a concert by one of the strangest collections of musical instruments ever put together – but they loved it.

It began soon after the fires were put out. Musician First Class Saxte Dowell, featured performer in the late Hal Kemp’s hand and composer of “Three Little Fishes,” rounded up some men to play in mess halls, knee deep in water.

Their instruments and music were ruined. An empty gallon jug served as a bass horn, fire buckets and spoons were used by the drummer, and “Frisco horns,” not further identified, took the place of clarinets.

“We tried to play everything the boys asked for,” Musician Dowell said. “Most of them wanted to hear “Don’t Fence Me In.” When we got to the part of the lyrics that read ‘Give Me Land, Lot of Land’ – well, I don’t have to tell you that the entire ship’s company joined in.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Loss of 772 on Carrier Revealed; Ship Saved After Battle Off Japan

Survivors Refused to Quit Craft

By JOHN M. McCULLOUGH

The Philadelphia Inquirer

Inquirer Washington Bureau

May 18, 1945

WASHINGTON, May 17. – Bomb-wracked, fire-blackened but unconquerable, the 27,000-ton Essex class aircraft carrier Franklin is home from the consuming fury of the Pacific war.

Her flight deck Is an empty concourse. Her mainmast is leaning at a drunken angle. Her foremast is a ragged stump.

341 OF CREW KILLED

Out of her total complement of more than 2500 men, 341 are dead. 431 are missing in action, and mora than 300 are wounded.

She went out a princess of the carrier fleet to hurl aerial destruction at the Jap; she came home a weary and a bedraggled harridan, a soot-stained fugitive from hell.

But she’s a “fighting lady.” Her men, living and dead, made her so.

The Navy Department today told the almost unbelievable story of the Franklin, only 59 days after she took her all but mortal wounds from an enemy dive bomber only 66 miles off the coast of Japan.

DAMAGED MARCH II

When the mere wraith of a great carrier was nudged into her berth in the Brooklyn Navy Yard a few days ago, by official Navy pronouncement “She had lost a greater number of men and sustained more battle damage than any ship ever to enter New York Harbor under her own power.”

On March 19, the Franklin was one of the powerful combat ships in the immortal Task Force 58 which was going for what was left of the Japanese fleet, huddled dejectedly In the ports and anchorages of Japan’s Inland Sea.

‘DIGGING ‘ EM OUT

Admiral William F. Halsey. Jr., commander-in-chief of the Third Fleet, only a few days before had declared in Washington that if the enemy fleet did not choose to come out and fight, the Pacific Fleet would “go in after ‘em and dig ‘em out.”

The Franklin and her sister ships, comprising one of the fastest, most deadly and most powerful combinations of naval offensive strength ever gathered in a single attack formation, were “digging “em out.”

Most of the Franklin’s flight deck was packed with planes, ready to take off. Scores of others were aligned handy to the elevators on the hangar deck, gassed up. loaded with ammunition and bombs to deliver their devastating strikes against the enemy.

HIT BY TWO BOMBS

Suddenly, out of the lowering overcast, a Japanese dive bomber streaked, too swiftly and unexpectedly for the carrier’s protecting fighter patrol to intervene. One 500-pound armor-piercing bomb plunged through the flight deck, exploding beneath; a second penetrated to the hangar deck.

Within a matter of seconds, the proud carrier was an indescribable creature of Hades. Gas tanks, bands of high-caliber ammunition, bombs and rockets detonated and foamed in a red fury. Hopelessly trapped, men were reduced to ashes or blown to atoms in the tick of a watch.

BLASTS ROCK SHIP

All of the pent-up destruction which was to have deluged the enemy roared and thundered and shrieked in the steel-plated confines of the Franklin.

It was this very incident which had hopelessly crippled America’s early carriers — the Lexington, the Wasp, the Hornet, the Yorktown: The instantaneous and uncontrollable ignition and detonation of their own gasoline and explosives. It didn’t destroy the Franklin.

ATTACKER IS DESTROYED

American fighter planes pounced upon the daring Japanese dive bomber and tore it into unrecognizable fragments with a hail of fire – but the carrier herself seemed doomed.

She was only 66 miles off the coast of Japan, dead in the water, her communications system shattered, her steering mechanism gone, her highly integrated complement of officers and men chopped in half. .

In the midst of such confusion and dreadful scenes as few men upon her had ever witnessed, the ship’s discipline barely wavered.

THERE WAS NO PANIC

The Navy’s announcement said:

“There was no panic.”

A hint of the situation aboard the carrier was contained in the only story issued by the Navy from the lips of a Philadelphian surviving the ‘holocaust. He is Charles F. Seested, Jr., at 449 West Price St., Germantown, an aviation machinist’s mate, second class, who was reported to be recovering comfortably from his injuries in the sick bay of a battle cruiser.

‘WHOLE SHIP VIBRATED’

“I had Just returned to my workshop, which is located aft between the flight deck and the hangar deck,” he was quoted as saying. “I had just taken off my life jacket for the first time in 36 hours. Then the bomb struck.

“The whole ship vibrated. Men were knocked off their feet, everything was a mess. I rushed to my life-jacket. By the time I had it on, the ship was filled with smoke. We began to choke, our eyes burned.

“I made an attempt to get out through a hatch on the starboard side, but the second I stepped out, I felt intense heat. I groped my way back to the shop and found a porthole. I had to remove my life-jacket to climb through, then I had to climb down the stern of the ship about 35 feet to reach the fantail. I did this by letting myself drop twice. I was holding to my life-jacket, with one hand.

‘TERRIFIC EXPLOSIONS’

“As I reached the fantail, there were two terrific explosions. Wood and metal were flying in every direction. I put on my jacket and made a grab for a lifeline. Sometime during all this time, my steel helmet had been blown off.

“Then another blast occurred. Something hit my head. That’s all I remember until I came to in the water. The ship was a long way off.

He was picked tip by al destroyer – the U.S.S. Hunt, one of four which with the light cruiser Santa Fe boldly moved in until flames blistered the paint on their plates, to lend aid and rescue the survivors.

ALL LEND A HAND

The Philadelphians story is only lone of 50 which were relased by the Navy today – all testifying to conditions from which it seemed almost impossible, that any human being could escape with his life.

Every living man, including many who had been blistered and almost denuded by the intense heat, turned airless, smoke-choked passages, reached the controls which flooded as yet unexploded magazines.

After the cruiser Santa Fe had taken off the last of the injured, according to the Navy story, “the surviving members of the carrier’s air group were ordered to leave the ship.”

Whether this order was tantamount to “abandon ship” is not made clear, but if so, it was ignored.

REFUSE TO BUDGE

Deep in the fire-rooms, seamen donned gas masks and refused to budge. Some of them died of suffocation. Others were cremated. Still others doubtless were drowned. But the survivors wouldn’t quit. By early afternoon, the carrier, wallowing drunkenly. was taken in tow by the heavy cruiser Pittsburgh while a security patrol of fighter planes circled constantly overhead.

Twenty-four hours after the attack, the indomitable engineers had one fire room in operation, adding three knots to the Franklin’s towing speed. An ingenious seaman had rigged up an Army “walkie-talkie” for short-range communication. The carrier was steered with her main engines.

WORK DAY AND NIGHT

Men worked day and night, without sleep, with little food, with only hastily-dressed wounds. Little by little, the debris was cleared away, other fire rooms restored to operation. By end of the second day, the tow – line was dropped and the Franklin, a fantastic caricature of a ship, was on her own, eastward bound.

On March 21, 300 men who had been evacuated from the ship returned to reinforce her skeleton crew. Ships of the escort radioed to the Franklin, offering more crewmen, food and equipment.

‘PLENTY OF MEN’

The carrier’s little “walkie-talkie,” screeching and squawking like a badly worn victorola record, had the answer.

“We have plenty of men and food,” came the message. “All we want to do is get the hell out of here.” Surging along in the wake of her many-gunned cruiser escort, the Franklin headed for home, 12,000 miles away.

She made it, under her own power. She’s a “Fighting Lady.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Pal’s Invitation to Mess Saved Mate on Franklin

Philadelphia Record

May 18, 1945

Pharmacist’s mate 3/c Harry Arthur Stinger, 22, of 5826 Akron St., a survivor of the USS Franklin, probably owes his life to a chance invitation from another shipmate to eat elsewhere than in the main mess hall.

A few minutes after he and his friend went to another section of the big carrier, a bomb landed in the mess hall, killing all who were there, Stinger told his mother, Mrs. Rose Stinger.

Sailor Nearby Killed

Even so, he narrowly escaped death from another bomb that exploded over the place where Stinger and his friends were sitting. A sailor sitting in front of him was killed instantly, but Stinger and two others managed to reach the deck. Six others in the compartment were burned to death while struggling up a companionway.

On the deck, Stinger received a shrapnel wound in the leg. While attempting to give a sedative to a fatally injured man, Stinger was overcome by smoke. When he regained consciousness, he made his way to the rail.

The sea was a mass of flaming gasoline, but Stinger plunged overboard, swimming under water until he was outside the blazing area. He and another sailor were in the water 40 minutes until their rescue by the Santa Fe.

Survivor of Hornet

Comdr. David Berger, 32, of 224 E. Church Rd., Elkins Park, a survivor of the carrier Hornet, sunk in 1942, was knocked to the deck of the Franklin by the first explosion. After lowering himself by a rope from the bridge, he joined other crew members in fighting the flames.

Berger said that in comparison with the Hornet sinking, the Franklin disaster was a nightmare.

Other Philadelphians saved after the bombing on March 19 included Steward’s Mate 3 c Willie Cogman, 30, of 1412 S Chadwick St.; Aviation Machinist’s Mate 3 c Edward G. Mc Glade, 402 W. Spencer St., and Aviation Radioman 2 c Michael A. Monte, 3149 N. 23d St.

Letter to Father

In a letter to his father, Leo Burt, 242 W. 11th Ave., Conshohocken, Aviation Machinist’s’ Mate 3 c Edward J. Burt, 19, told of swimming 5 1/2 hours before being rescued. “I thought my number was up,” he wrote. “But I kept thinking of how you’d feel if you got a telegram, and that kept me up.”

Others from this area known to have been aboard the Franklin are Machinist’s Mate 1/C Leon Ellis, 24, of 564 Pine St., Camden, saved after being trapped below decks for 15 hours, and Torpedo man 3c Russell E Vasey, 20, of 2906 Buren Ave., Camden, listed as missing.

From Cape May yesterday came the story of the meeting, in the Franklin disaster, of two local boys who had not seen each other since their school days. When Seaman 2 c Jonathan C. Trout, a gunner on the carrier, was rescued, he found his former chum, Belford Lemunyon of West Cape May, aboard the destroyer.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Philadelphian Trapped on Carrier Tells of Escape Through Porthole

Philadelphia Record

May 18, 1945

WASHINGTON. May 17 (AP) – Charles F. Seested. Jr., aviation machinist mate second class, today told how he escaped from the aircraft carrier Franklin.

Seested, whose wife, Mrs. Ann G. Seested. lives at 449 W. Price St., Philadelphia, told his story aboard a cruiser in the Pacific where he is recovering from his injuries.

“Whole Ship Vibrated”

“I had just returned to my work shop, which is located aft between the flight deck and the hangar deck,” he said. “I had just taken off my life Jacket for the first time in 36 hours. Then the bomb struck.

“The whole ship vibrated. Men were knocked off their feet, everything was a mess. I rushed to my life Jacket. By the time I had It on, the shop was filled with smoke. We began to choke, our eyes burned.

“I made an attempt to get out through a hatch on the starboard side, but the second I stepped out, I felt intense heat. I groped my way back to the shop and found a porthole. I had to remove my life jacket to climb through, then I had to climb down the stern of the ship about 35 feet to reach the fantail. I did this by letting myself drop twice. I was holding my life Jacket in one hand.

“Two Terrible Explosions”

“As I reached the fantail there were two terrible explosions. Wood and metal were flying in every direction. Then another blast occurred. Something hit my head. That’s all I remember until I came to in the water. The ship was a long way off.”

Seested was picked up by a destroyer and later was transferred to the cruiser.

Another Philadelphian among the Franklin survivors was Lt. Comdr. David Berger, 32-year-old lawyer, of Elkins Park, who served as assistant air officer.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

MARINES WIN FOOTHOLD IN NAHA;

INFANTRY GAINS IN EAST OKINAWA;

LOSS OF 832 ON U.S. SHIP REVEALED

The New York Times

May 18, 1945

SMASHED CARRIER SAVED BY BRAVERY

Skipper and Officers Say They Never Entertained Thought of Quitting Blazing Craft

The New York Times

May 18, 1945

Despite the tremendous explosions and fires that swept the 27,000-ton aircraft carrier Franklin after she was hit by two bombs sixty miles off the Japanese coast, the thought of abandoning ship never was considered for a moment, the carrier’s skipper, Capt. Leslie E. Gehres, declared yesterday.

Interviewed with some thirty of his officers and enlisted men at the Navy Public Relations Office, 90 Church Street, Captain Gehres was liberal in his praise of the heroism and ability of the Franklin’s personnel. Only their efforts and the aid of the accompanying warships, he said, made it possible for the carrier to reach port.

“The attack was an aviator’s dream,” the 47-year-old veteran skipper said. “We were caught while we were launching the second flight of the day.

“Great sheets of flame enveloped the flight deck and the anti-aircraft batteries,” he continued. “The forward elevator rose up in the air land then disappeared and dense smoke rolled skyward. Then things started exploding all over the forward part of the ship.”

Praises Heroism of Crew

The rest, Captain Gehres said, is a story of a heroic crew that refused to believe that the Franklin, only sixteen months after she was commissioned at Newport News, Va., was destined to end her career on the floor of the Japanese seas. It is also a story, he said, of the great work of such ships as the cruisers Santa Fe and Pittsburgh and many destroyers, including the Miller and the Hickock, which towed and protected the Franklin while she was dead in the water.

Of her crew of more than 3,000 officers and men Captain Genres disclosed, 832 are dead or missing and 270 wounded, ninety of them seriously.

Comdr. Henry H. Hale of Gary, Ind., the carrier’s air officer, was busy launching planes when the first bomb struck.

“Flame seemed to cover the whole forward part of the ship,” he said.

“The plane on the runway was picked up and turned over on its back, but the pilot, I found out, later escaped unhurt.”

All Planes Lost, 4 Jeeps Saved

“Every plane on the ship was lost,” Commander Hale said, “but oddly enough four jeeps used ordinarily to pull planes into position for take-offs were unscathed. These jeeps came in handy later when we went to work clearing the wreckage.”

The ship’s executive officer, Comdr. Joseph Taylor of Danville, Ill., was standing next to the wave-off officer when the first explosion tore through the ship, he said. He was blown across the deck against the starboard lifelines, but was unhurt.

“Finding myself in one piece,” he said, “I immediately made for the bridge to see how the captain was. The captain was shaken but unhurt and ordered me to ascertain the extent of damage. I spent the rest of that nightmare supervising fire control parties and arranging for a tow by the cruiser Pittsburgh.”

Lieut. (j.g.) W.R. Wassman, 24 years old, of New Rochelle, N.Y., who was assistant navigator on the carrier, told of his part in the rescue of five men trapped aft in the steering engine room.

New Rochelle Man Hero

“As soon as we could get aft,” he said, “we worked our wav over the hot and twisted steel to the fantail. I heard a boy moaning and after a search found him, badly hurt, lying among a group of dead. Aided by another sailor, I got the man to the safety of the deck and then went back again.”

“We had rescue breathers with us this time,” Lieutenant Wassman continued, “and, holding them above the sloshing water, we worked out way through four compartments, toward the trapped engine-room men. By shifting the water from a compartment above the engine room to another compartment we were able to get the men out.”

Shipfitter, first class, Herman Friedman, 29, of 817 East 175th Street, the Bronx, was in his quarters when the attack occurred, he revealed. He went to his battle station – repair and damage control – but stayed there only a short time, when he found the communications system out.

“I went forward for orders then,” he said, “and later when organization developed went below to counter-flood compartments to correct the ship’s list. I was not hurt, but I was certainly scared.”