We would have to ditch,

take our chances against riding down with the plane straight to the bottom of the Channel,

and take our further chances on being picked up by friends, not foes, at sea.

I argued for that proposal.

Everyone knew it was a personal matter with me.

I could see no other way to get home

to my wife and shortly forthcoming child before the war’s end.

I might grow old while my child grew up.

“Poor Benny – he’s got to see his kid.”

Real sympathy poured over the intercom disguised as mock tears.

Bohn supported me from the start.

Mike and Duke pitched in, and the others followed cheerfully.

I accepted such sacrifices without a qualm.

I was young then.

Would I now try to persuade others to make so risky a choice on my account?

Not likely.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

This “second” excerpt from Elmer Bendiner’s The Fall of Fortresses covers the ditching of Tondelayo in the English Channel while returning from the 379th Bomb Group mission to Stuttgart on September 6, 1943. Bendiner weaves together his correspondence to his wife, what seems to have been postwar correspondence or personal conversations with his pilot, Bohn Fawkes, perhaps historical records from the 527th Bomb Squadron, and certainly his own memories, into a fast-moving and crisply detailed historical tapestry that captures the mixture of fear, tension, humor, and matter-of-factness inherent to a situation and event where survival was problematic. And, if problematic for one, then ten times more problematic for the crew of a heavy bomber.

In this regard – and viewed from an even higher perspective, whether of time or (quite literally!) altitude – any perusal of official records or serious historical works pertaining to the WW II air war (let alone later conflicts), specifically in terms of the survival of aircrews lost at sea – whether through controlled ditching or mass bailout – will readily reveal how problematic was the survival of airmen during such events. The USAAF’s Missing Air Crew Reports and most any of R.W. Chorley’s series of books covering WW II Bomber Command Losses are replete with accounts of such events – some heart-rending; many sad beyond words and thought; many others inspiring; a tiny few perhaps humorous – that leave one wondering about the unpredictable intersection between training, skill, bravery, and fate. (Yet, in Judaism there is no such thing as “fate”. There I momentarily and theologically digress!) Still, whether you prefer “fate” or fate, all things held equal, repeated training, preparation, and familiarization with both an aircraft’s design, and personal survival gear, could certainly make a difference in the probability of an airman’s survival at sea, whether via bailout or ditching.

Specifically mentioned or alluded to in Bendiner’s story are (of course) pilot Bohn Fawkes, anonymous co-pilot “Chuck”, flight engineer Lawrence H. Reedman, and tail gunner Michael L. Arooth. Of these four men, let alone the entire crew, it seems that the only individuals hurt or injured were Bendiner (unspecified), “Chuck” (wounded in his leg by 20mm cannon fire) and Arooth (badly gashed his head during the ditching.).

The videos below elucidate aspects of survival at sea in terms of successfully ditching a B-17, and, the rate of aircrew survival during such events. Note that the final section of “B-17 Bomber Ditching Survival Rate? Not Good” is “Strong Seasonal dependency on Rescue Stats”. This seems to be borne out by the ditching of the Fawkes’ crew in mid-summer (everyone survived), versus the ditching of the Leonard Rifas crew in mid-winter of 1945 (no-one survived).

Here’s “Ditch at Sea and Live in a Boeing B-17 (1944-Restored)”, at ZenosWarbirds.

“Ditching in water was a fact of life for stricken aircraft in World War 2, from the frozen white tops of the North Sea to the shark infested waters of the South Pacific. “Lt. Reynolds.” played by veteran actor Arthur Kennedy (Lawrence of Arabia), is copilot on a B-17 that ditches at sea. He survives by pure luck, but the rest of the crew is lost due to a lack of preparation. When he gets his own ship, Reynolds vows his crew is thoroughly trained in B-17 ditching. He gives them the straight dope, step by step.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

And, here’s “B-17 Bomber Ditching Survival Rate? Not Good”, at WWII US Bombers.

Topics of the video:

Causes of Ditching

Ditching Vs. Bailout

Range of Bomber VHF communications

Air Sea Steps for aircraft in Distress

Crew Ditching positions

Gibson Girl Usage

Air Sea Rescue Stats for the B-17 and B-24 Bombers

% of Rescues per month

Strong Seasonal dependency on Rescue Stats

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Elmer Bendiner stands before the nose of Flying Fortress “Tondelayo” (B-17F 42-29896, squadron identification marking “FO * V“). Photo from Silvertail Books.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Tondelayo early in her short-lived combat career – during the summer of 1943 – as seen in Army Air Force photograph 60509AC / A45870.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Unfortunately, I’ve no idea of the specific (or approximate) location in the English Channel that marks the undersea resting place of Tondelayo. By definition there’s no Missing Air Crew Report for this incident, and the historical records of the 527th Bomb Squadron I believe only commence in October of 1943. C’est la vie.

And thus, Elmer Bendiner’s account of the mission:

Stuttgart lies some five hundred miles inside Germany. A heavily loaded B-17 flying at a moderate altitude – say, seventeen thousand feet – in formation, zigging and zagging in evasive action, might be expected to make the round trip but would land with fuel tanks perilously close to empty. There would scarcely be a gallon to spare for a foolish mistake or a bit of horseplay.

The mission was being led by Brigadier General Robert Travis. I had nothing against the General before Stuttgart because I knew very little about him except for his legendary talent at poker. After Stuttgart many of us had a great deal against him. He added to our anxieties – or at least to Bohn’s – from the very inception of the mission by announcing his intention of following a newfangled theory developed by someone at Bomber Command. A great deal of fuel was being wasted by climbing to altitude with full tanks, it was reasoned. Why not climb at a later point when the tanks would be lighter?

My second-lieutenant pilot could have told the General why not, but he wasn’t asked. To fly in the thin upper air a plane needs the added strength of its superchargers. If those superchargers are out of order it is best to realize that incapacity when you are over friendly territory and can drop down to a lower altitude and head for home. It is not wise to wait until one is at altitude over enemy territory to find that you cannot stay in formation.

Travis, untroubled by such technical considerations, led us across Europe at ten thousand feet until we were close to Tubingen, from which we would turn onto the target. Then he began to climb steeply and we followed him. Our superchargers worked. The record does not show whether others failed, because how can one distinguish in the fall of a Fortress the various ingredients of disaster – enemy flak or 20-mm. shells or rockets or simple mechanical failure?

We were flying low and on the outside of the formation. Travis and his lead group were in view ahead of us. As we rounded Tubingen I noted clouds moving across the Black Forest. Outside my starboard window the Neckar River was still plainly visible snaking its way to the target.

Stuttgart lay before us in checkered sun and shadow. It was close to noon. The flak came up, but not too heavy. Then as we neared the target white clouds capriciously intervened. Bob had no concerns; he would drop on the leader’s bombs. But those clouds must have disconcerted Travis’s bombardier, all set as he was to fix the primary target on the cross hairs of his bombsight. Could he switch at an instant from visual bombing to instruments?

We read the answer in the spectacle of our lead group passing over the target with bomb-bay doors wide open and no bombs falling amid the furious black flak.

Travis was going around for another try, and the formation would wheel behind him. All very well for Travis and the happy few at the hub of that wheel. They could describe a nice, tight circle. But to us on the outward rim it meant a fearsome strain to keep up with the formation, and a serious drain of gas. We had to fly perhaps an extra forty or fifty miles at full throttle, using gas at very nearly the rate required for a takeoff, just to keep our position in the formation.

We could have come in closer to the hub, shortening the radius of the swing and saving considerable fuel, but we dared not slip under the open bomb-bay doors of Travis and his group. His bomb bays, like ours, were loaded with incendiaries. (This too seems odd, for ball bearings and the machines that make them do not burn.) The incendiaries were ingeniously packaged in clusters with a timing device so set that, at a predetermined distance below the bomber that hatched them, the firebombs would spread out and cover a wider area.

No one could be sure just when those incendiaries would tumble out, their clusters flying apart. We swung out in a wide arc. Why the General did not close his bomb-bay doors is yet another unanswered question of the city.

On the second time around, the incendiaries fluttered down, and smoke billowed up in black clouds from the city.

As we turned away from the target the Luftwaffe made its belated but emphatic appearance. Fighters came at us head on and blazing. Bohn was one of those pilots who believed ardently in evasive action. (There are some contrary schools of thought, which declare that it is better to fly straight and level as if on parade, following the model of the Light Brigade.) As the German planes came at us from high out of the sun, Bohn pushed Tondelayo to climb and pitch. This seemed to throw the attackers off momentarily. But they – or others like them – came at us again, three or four abreast. Bohn recollects that he saw a puff of smoke from the engine of one of the German fighters and in response nosed Tondelayo into her dance. In retrospect he much regrets that he did not accurately interpret the puff as an indication that the German pilot had cut his throttle and was waiting for us to come down from our jump while he slowed his run at us. He caught us cold and raked Tondelayo from nose to tail.

When he left us one of our engines was on fire; our copilot of the day, Chuck, had had his leg torn by a 20-mm. shell; the oxygen lines in the rear of the ship had been cut, and the oil-pressure gauge was down to zero because our oil line had been severed.

Now, it is the oil pressure that enables the pilot to change the pitch of the propellers. And if the pitch cannot be changed the propeller stands like a rigid paddle in the teeth of hurricane winds. If it spins without lubrication the friction can build up enough heat to melt metal. Then the propeller blades might turn into a deadly missile and slash the frame that held us. Our own propellers were poised like axes against us.

It was clear that we could not stay in formation. To put out the fire in our engine we would have to work up an airspeed of at least 235 mph. We could have done so only in a dive. (We had been at that deadly extremity before.) In any case we would have to drop to lower altitudes with half our crew deprived of oxygen. (We had been there before as well.)

At the first lull in the fight we waved away our wing man and dived until the fire was out.

Now we can pick up the letter to my wife.

…We had to drop out of formation and fight our way across Europe by ourselves. As it developed, we didn’t so much fight our way out as sneak out, running for every cloud cover we could see. The spot decision right then was up to Fawkes. He could have asked for a course to Switzerland. The lovely snowy, blue-and-white peaks of the Alps were plainly visible, towering almost up to our altitude, although quite a way off….

I must interrupt again. Technically it was up to Bohn, but not actually as it turned out. Bohn was our commander – and a very good one, which is to say that he almost never gave an order. We talked this situation out, weighing the pros and cons as if we were civilians around a table. While we talked we flitted from cloud to cloud over Europe. I had given Bohn a heading, but he could scarcely keep to it while chasing clouds. I had to follow every twist and turn he made, altering our headings accordingly and still aiming for England by the shortest route.

It was plain from the most casual glance at our fuel level, at our ground speed, at our low altitude and at the distance we had to go that we could not make it back to Kimbolton. We had three choices to discuss. We could head for the Alps, where we would be interned for the duration. (General cheers over the intercom.) Choice number two: we could bail out over France. We all carried civilian passport pictures. (I liked mine because I had borrowed a very un-Army, tweedy jacket for the purpose.) We could hope to land amid the French Resistance and follow their lead to the Channel coast, where we might thumb a ride on a fishing boat. Our intelligence captain had described this alternative as an easy walk across occupied Europe for which we were well armed with a snapshot and a .45-caliber pistol. (Dead silence for that option.)

Last possibility: we could fly as far as our fuel would permit. I told everybody I was sure we could reach the Channel. We would have to ditch, take our chances against riding down with the plane straight to the bottom of the Channel, and take our further chances on being picked up by friends, not foes, at sea. I argued for that proposal. Everyone knew it was a personal matter with me. I could see no other way to get home to my wife and shortly forthcoming child before the war’s end. I might grow old while my child grew up.

“Poor Benny – he’s got to see his kid.” Real sympathy poured over the intercom disguised as mock tears. Bohn supported me from the start. Mike and Duke pitched in, and the others followed cheerfully.

I accepted such sacrifices without a qualm. I was young then. Would I now try to persuade others to make so risky a choice on my account? Not likely.

We knew then that our co-pilot’s wounds were superficial, but would not Switzerland have seemed the safest bet for him? We could have made a case for internment. Why didn’t we?

Back to the letter:

…Bohn asked for a heading home and I was glad of it even though with fighting and one thing and another I was a bit vague as to our precise position at the time. We dived down into the loveliest, heaviest cloud imaginable and stayed in it as long as possible, while I feverishly worked away to establish our position and improve on the course I had originally set. The cloud gave out, and for a time we sailed at low altitude over the grain fields, forests, towns and rivers of France. Some of these checkpoints seemed to bear out my theoretically estimated position and some of them contradicted it. It was beautiful country; it seemed to be of a different color from that of England or Holland or Belgium.

We were playing hide-and-seek in the clouds over France. And in the open spaces our gunners were anxiously watching for German fighters who were looking for us but who miraculously failed to see us before other clouds came up to hide us. However, ground radio was tracking us and we had to shift course to clear what I thought would be heavy flak areas. We could see flak on both sides of us, largely to signal fighters, we thought….

At this point I must refer to Bohn, who remembers clearly an incident which I recall only dimly. We had been flying through cloud for some time when he asked me where we were. He says that he could see no way in which I could be sure of anything. And he was right, of course. I had followed our zigs and zags as best I could, but how could I be certain in that fog to which we clung? Then I had my answer from the Germans. The gray-white nothingness was punctured by black flak explosions all around us. “Ah,” I said, “Rouen.” We both laughed.

…Just before we crossed the coast Fawkes called up and suggested that anyone who didn’t want to take his chance in the water could still jump. None of us did. I could see water ahead, but we ran up along the coast to avoid a large seaport and heavy coastal flak. Duke, our radioman, was sending out an SOS and asking radio stations to take a fix on us. They did and he reported it to me, but it seemed to me to be way off. And Duke asked for another, which was just as bad. I realized then that no one in England knew where we were. I gave Duke our estimated position, but he couldn’t get it through….

Actually the British shore stations were asking us to move some thirty miles north where they could get a proper fix on us. They did not know it, but they were asking men to fly without wings. When we crossed the coast we had only one engine working, and in a B-17 that is a few minutes away from none. I gathered a few of my belongings – a chart of the Channel coast, which I folded and slipped into the pocket of my coveralls, a pencil or two, my gloves (gauntlet types that were more elegant than warm) and Esther’s picture. Then I clambered out of the nose, up the hatch behind Bohn, and through the bomb bay to the radio room.

…We were over the sea now and our four engines ran out one after another. When I left the nose, two of them were already motionless—a most disconcerting thing to see in an airplane. Back in the radio room we all took our previously assigned positions, bracing ourselves for the shock. I crouched behind the radioman’s armor plating and talked to Mike, who was crouched next to me. Up to the last minute Mike retained his faith in Tondelayo and couldn’t believe we would really have to ditch. He asked me whether we were headed toward England. I said we were but I knew we couldn’t make it. We chatted like that, looking up through the open hatch to the great, gray, swirling clouds, wondering how near the water we were and when the shock would come….

As we dropped closer to the sea Bohn turned to our copilot and asked him whether he had ever landed a plane in water. Chuck shook his head. Would he like to? No. With the last bit of power in Tondelayo Bohn maneuvered to land along the crest of a wave. To hit a wave broadside is very like flying into a stone wall. We skimmed the crest, then sank into the trough of a mountainous wave. We sank, then rose, buoyed by empty gas tanks.

From the cockpit Chuck saw his fondly crushed pilot’s cap in the hatchway leading to the nose and seemed about to try to fish it out. Bohn recalled looking at him doubtfully as if to say, “You’re on your own.” No window in the cockpit of a B-17 is made to allow a grown man to wriggle out of it unless he is in the extremity of desperation. Both Bohn and Chuck made it to the wing.

Someone should have pulled a lever to release the dinghies from the fuselage. No one had. Bohn quickly scanned the directions on the metal plaque above the wing. He pulled the appropriate lever as per instructions, but nothing happened. He and Chuck pulled, twisted and clawed the dinghies out, then started the inflation, which should have been automatic. Could it have been ten seconds or thirty? None of us remembers how long it took to climb out.

…We lit lightly at first and only a bit of spray seemed to come in. Mike stood up, and we all yelled to him to get down. But it was too late. After skipping along the water the ship finally plunged, throwing Mike forward so that he gashed his forehead. Then the green-gray water rushed in. I felt nothing so much as surprise. In drills there had been nothing to suggest such a torrent of ocean running through our airship. I tried to stand, but the force of the water knocked me down, and when I did get up, some of the precious things I had gathered were floating.

Everyone was on his feet, everyone excited and clambering toward the hatch, everyone shouting that there was plenty of time and to keep calm. Mike stood next to me and I saw that his head was bleeding badly. A piece of floating B-17 had clipped me and scratched my forehead. For an awful moment I thought that Mike and I, who were wedged in a corner, would never get out. Mike finally managed it. By that time the water was up to my chest and rising rapidly. Our bombardier, Bob, was still in there. I hoisted myself up on one side while he made for the other. I remember that I failed to make it the first time and I could hear Mike hollering outside, “Where’s Benny?” Then I clambered out. The wings were already under water.

I clung to the fuselage for a second or so and watched Fawkes and the others, who had extracted one of the rubber dinghies and were maneuvering it away from the wings of the sinking plane. Then I plunged into the water. The dinghy was scarcely more than a stroke away from the ship. But I had overlooked one detail that might have proved disastrous. I had neglected to inflate my Mae West….

Actually the dinghy must have been farther off than a swimming stroke or it would have been sucked down by Tondelayo. Obviously a participant in an event is not the most reliable witness when it comes to precise measurements. On the other hand, the raft could not have been too far off, because I have never been a good swimmer and for that occasion I was wearing a full flying suit and boots; my pockets were stuffed with map and pencils, Esther’s picture and odd bits of paraphernalia I thought I might need.

…I clung to the raft while Larry, our engineer, kept shouting, “Hold on, Benny, hold on” – as if I thought of doing anything else or going anywhere else just then. When I turned around Tondelayo had vanished; our dinghy and the other one holding the rest of our crew were the only things left on an apparently limitless sea. After a bit of floundering about I managed to hoist myself into the tossing dinghy. All this took much less time to live through than it does to record.

The Channel was as rough that day as it ever gets, and the swell was dark, towering and fearful to look at. It was worse to feel. We became violently seasick. That is, all except Bob and one gunner, who increased our miseries by remaining obtrusively and volubly high-spirited. There is, however, a measure of providence in the seasickness that plagues the shipwrecked. First, it gives them something to do which relieves the monotony; second; it makes death almost welcome.

Before giving way to utterly abandoned retching and writhing we paddled with our hands toward the other dinghy so that we could lash the rafts together….

Dinghies are equipped with oars, but we could not find them. Eventually they turned up at the very bottom of a heap of tightly stowed, largely unworkable gadgetry.

…In between spasms, when I could lie with my head back and not feel too sick, I could watch the endless seascape and the barren sky. Bob was cranking our portable radio frantically but in vain, because we had lost the kite to raise our aerial; we knew then that we could send no signal at all.

From time to time Larry would bail out some of the water that swept over us in salty waves whenever we thought we might begin to dry out in the sun. Larry would bail a little, get sick, bail some more and get sick again. I tried to help, but as soon as I’d lift my head I’d vomit. I was no help at all. For five hours we tossed like that and in my lucid moments, I would speculate on the direction of our drift. It was impossible to tell with any certainty. I knew what winds had been prevailing all afternoon, but there was much I did not know. In one lucid moment I looked down at the few things I had brought with me. One of these was my Mercator’s Chart. Now, darling, there is nothing quite so useless on a broad ocean as a Mercator on a raft that one cannot steer. I finally threw it overboard.

Toward the end of the afternoon we were all resigning ourselves to spending a night on the water. I, at least, was convinced that no one in England had any idea of where we were. Earlier we had seen a flight of bombers, but they were very high and no one aboard could possibly have seen our signals. It was a little more than five hours after we ditched that we sighted a squadron of fighters. Larry had the flare pistol out and ready to shoot. Duke shouted that they might be Germans. Some of us told him to shoot and others yelled at him not to.

Here I must point out a rare phenomenon. Bohn said, “Fire.” When Larry hesitated Bohn said for the one and only time in my memory, “That’s an order.” Bohn told me later that he was positive they were Spits by the sound of them, which we had heard minutes before we saw them. Actually when we spotted them they were headed like a flight of arrows to England and no one in our position – climbing and sinking amid monstrous waves – could say whether their silhouettes were German or British. They were mere specks and shadows and I could see in them neither friend nor foe. Bohn’s ears for machinery were far subtler than mine. And I am grateful to them.

…Larry fired. The fighters were already past us, but one blessed pilot was looking back for an unknown but providential reason. We watched the fighters fly on and then noted that one peeled off, and the others followed.

They came in low over the water toward our flare – a magnificent affair of parachutes, red balls of fire and smoke like a Fourth of July celebration. Those Spitfires were the most meaningful, beautiful things I have ever seen. They swooped down and circled above us. Sick as we were, we stood up, waved and yelled at them, and came very near to upsetting the dinghies altogether. One of the Spits circled high above us to radio our position while the others continued to make passes over us by way of sustaining our morale. It was wonderful. We would cheer and laugh and get sick again, then laugh some more. I have never been so happy and so miserable at the same time.

After a while the Spits left us, but we felt certain that help would be on its way in no time at all. After a while another Spit did come out….

I am reminded by my pilot that it was not a Spit but a Mosquito.

We set off another display of fireworks and he too came over to circle above us. We were very glad to have him and we were sure that we were practically saved, but the sun set and the swell seemed to grow more ominous and still there was no rescue. We knew that our guardian plane would run out of gas soon. After a final pass he left us. The moon came up, big and yellow over the water. It was a lovely night, cold but full of stars – a few of which I fruitlessly recognized – but, lovely night or no, we continued to be sick. We strained our ears listening for motors. We saw lights where there were none. We told each other that we were sure to be rescued that night. But I think that each of us acknowledged to himself that it was unlikely.

We had been in the water about nine hours when Mike suddenly shouted that he saw a light. Fawkes saw it, too, when we rode the crest of a swell. We sent up another flare and then waited. Then we heard the dull throb of a motor, and a beam of light reached out near us but not quite on us. Dinghies are pitifully small things to spot on an ocean. We fired another flare, this time into the wind so that it fell back directly over our heads. The beam swung around and picked us up. Then while the light came nearer a terrible thought struck me and most of the others, I suppose: What if the vessel were an enemy ship? To have traveled all that distance across Europe alone, to have dived Tondelayo into the sea, to have spent nine agonizing hours on a raft, all to avoid capture and then to be picked up by the wrong ship – that would be too bad. We shouted and soon heard someone answering. “Ahoy,” said a voice behind the light. Apparently our collective Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Texas and New York accents made themselves known, and the voice answered jubilantly, “OK, Yanks, we’re coming.”

We clambered aboard the boat, fumbling awkwardly up the swaying rope ladder. There were a dozen happy angels dressed in blue RAF uniforms and turtleneck sweaters saying, “Bloody good show,” and cinematic things of that sort. They had hot soup and dry clothes ready for us. I couldn’t swallow the soup and, since I paused on deck for one last mighty heave of what was still in my innards, I came down too late for the clothes. But I stripped to the skin and they wrapped me in warm fleecy blankets….

While Bohn and I lingered on the deck we thought we saw a great hulk move out of the sea perilously close. Bohn tapped the shoe of the captain on the deck above us and gestured toward it. “We’ve copped it,” said the captain quietly, but he was wrong. The apparition was another British rescue launch, and together we headed home. The German shore batteries tossed a few shells in our direction, but they were not too serious about the effort.

…It was a long voyage home and we dodged minefields all the way. The skipper told us that we had drifted from our original position some twenty miles off the French coast to well within the patrol lanes of the Germans and in easy shelling distance of their coastal guns. By morning we would have been in enemy hands.

When we hit the coast town of Dover there was an ambulance waiting at the end of the stone walk. But Bendiner had no pants, nothing but a couple of blankets. I was panicky. I had read much about this town and it hurt my dignity to think that I would make my triumphal entry pantless. But I did. I clambered up the ancient stone steps of the wharf, clutching my blanket and looking like a refugee from a raid on a Turkish bath. It was very embarrassing. Those who were hurt were taken to a hospital. The rest of us – the cut on my forehead had thoroughly healed – went to the local officers’ barracks of the Royal Navy, where gold-braided commodores served us rum and scotch, hot soup and bully beef. They fussed about us and sought in a thousand ways to make us happy. But still I had no pants. At last some kind lieutenant dug up an outfit for me and I regained my dignity. As a matter of fact he provided civilian clothes for me – slacks and a sweater – so that for that night and the next day I felt like a civilian and looked like Don Budge….

***

Bohn, although a mere second lieutenant, was commander of the crew and therefore shared the quarters – and the razor – of the Admiral of the Port of Dover. He woke on the following morning to see the Admiral staring out to sea. That dignitary invited Bohn to join him for a morning dip in the Channel, then, hastily recollecting the circumstances, added, “I suppose not.” Bohn confessed during our day of rehashing the events to a slight twinge of embarrassment over the fact that he had not been the last to leave Tondelayo in keeping with his position. I told him of the commander of the Royal Indian Navy who testified at a board of inquiry, “I did not leave the ship. The ship left me.” That cheered Bohn.

On the following day, after we saw our co-pilot at the hospital and said a cheery farewell all around, our operations officer flew down to bring us back to Kimbolton. This time the groundlings had rolled our bedding and gathered our personal possessions into pathetically small packages suitably tagged. We unpacked and rejoined the living.

… I expect that shortly we will be shipped off to spend a quiet recuperative week at a seaside resort. Some of the boys who have been watching me furiously pounding away have become curious, and I have shown them most of this letter. They are now anxiously waiting for the last page to roll off the press so they can find out whether or not they were saved.

All my love,

ELMER

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

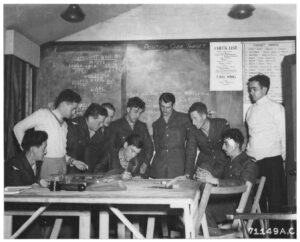

This truly remarkable image, Army Air Force photograph 71149AC / A14028, shows Bohn Fawkes’ crew (with the exception of co-pilot “Chuck”, recovering in hospital) at Kimbolton on September 7, 1943, the day of their return to their base. As described in Bendiner’s account, all are wearing British clothing. At the center of the photo, focused – perhaps – on writing an account of their experience, is (probably) Lt. Fawkes. Fourth from right is Lt. Bendiner, while seated at far right with bandaged head is Sgt. Michael Arooth.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The “quiet, recuperative week” mentioned by my young self did not come at once. We were being handled according to the latest authoritative study by Eighth Air Force psychiatrists. A crew that had had a very rough mission a month or so earlier had been dispatched to a “flak house” for rest and rehabilitation. They came back rested but scarcely rehabilitated. They had used their week off to mull over their collective past and unpromising future. On their return they announced their unanimous decision to quit the war. They would not fly combat again together or singly. It was not mutiny, merely combat fatigue.

Colonel Mo was taking no chances with us. He and a few psychologists who had been studying combat crews to see what ordinary creatures would do under extraordinary stress decided on a policy well known to everyone who has tried to train young equestrians. If they are thrown, toss them into the saddle at once. If they have escaped a broken neck they must be encouraged to try again.

Unfortunately, Kimbolton was socked in for ten days after Stuttgart, and the dark memory of the ditching seeped into our bones while we trudged through the mud to the mess hall or down to the line to accept without joy Tondelayo’s replacement – a plane named Duffy’s Tavern.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Not every WW II Army Air Force aircraft was bedecked with elaborate nose art, some planes simply bearing a nickname and nothing more. Such is the case of B-17F 42-31040 DUFFY’S TAVERN (otherwise known by its squadron code FO * A), seen here at Kimbolton on November 11, 1943, in Army Air Force photo B-71044AC / A11536. The plane’s nickname was doubtless inspired by – going by Wikipedia-ology – the CBS and NBC radio program of that name, which was broadcast between 1941 and 1951.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The recollection of Tondelayo sinking through green depths to the bottom of the Channel worked upon us. We saw our flesh within her skeleton, bloated, rising and sagging with ghastly swells, skin shredding in the eternal wash. Images teased us like sea-green sirens stirring an invitation to madness amid the autumnal swish of the fields around Kimbolton.

We did not describe to each other the atrocious look of death we ten might have worn within the twisted wreckage where our names, lettered on the metal frame, would serve as tombstones and where the flying limbs, swelling breasts and much venerated crotch of Tondelayo would be raped by pulsing tides and left to lie derelict.

We did not speak of her or the sea or of ourselves. I waited for a cablegram from Esther that would make me a father and seduce me from such visions. No message came for me.

We did hear from the void, though. Bohn had a note from Johnny, courtesy of the Red Cross. It was written in a breezy, wish-you-were-here mood from a Stalag Luft. He had floated down to earth safely but landed among people who did not recognize the war as a game. Rendered mindless by the rain of bombs or perhaps by earlier horrors, they spoke of lynching the bomb crews who came to earth. Johnny was rescued by German airmen who, in 1943, saw him as a member of their fraternity. They understood the bombing and the killing of total strangers in ways that a civilian could never appreciate. They installed Johnny safely in a POW camp where the war was quite tolerable, it seemed. He was out of it at last.

I cannot now recall whether there were any who envied him.

We came to know Duffy s Tavern. It was no more than a soulless collection of B-17 parts. We inhabited it as if it were a furnished room. It was serviceable but no more. And this despite some energetic efforts to pretend that it had a spirit. Duffy himself, our flyer-turned-publican, broke a bottle over its wing and we drank to it in a mood of abstracted gaiety.

We ourselves had chilled the beer for that celebration by flying a case or two up to altitude – undoubtedly the most expensively cooled beer ever consumed. I watched myself celebrate. As I recall, we all seemed to have an air of odd detachment. We said and did familiar things, but I, at least, sat far back in my head, which had grown to the size of earth and heaven. I beheld myself with bemused interest while I waited word from Esther and my child.

On the sixteenth of September we piled into Duffy’s Tavern and headed for Nantes to take yet another whack at the impervious submarine pens. We made it back with only minor damage. I believe that our nerves then had been insulated by a sheath of ice so that they carried no messages of pain or fear. Perhaps we could have finished our missions or even done many more in that strange condition, operating by mechanical reflex, beyond or beneath sensation.

However, the day after we came back from Nantes we were shipped to Blackpool as if we were machine parts that had been chipped and needed to be overhauled. We did not work our passage across England but rode as so much functionless freight. I did not regard as a luxury the situation of a passenger on a free ride. I chafed at it.

When our plane rolled to a stop and the engines were cut we leaped out on the hardstand at Blackpool. The sky was cloudless, full of the possibilities of combat. I slung my musette bag over my shoulder and waited for the others. They emerged from the waist of the plane carrying something. They gathered in a circle around whatever it was. I elbowed into the group and saw at our feet our ball-turret gunner, Leary, the youngest of the crew. His hands clutched empty air. His eyes rolled back beneath his lids, exposing a fish-white vitreous. His shirt was pulled away from his trousers, and the belt pinched the skin of his belly purple. His neck and face were splotched.

“Keep him warm … give him air,” people shouted.

Bohn and Mike were kneeling at Leary’s side. Bohn was trying to take hold of Leary’s tongue to keep his airway open. Someone asked for a coat. I took mine off and handed it to Bohn, who covered Leary. Then some RAF groundlings tore up in an ambulance and loaded Leary aboard a stretcher. He too vanished as had our waist gunners on the Kassel raid, and as Johnny had earlier. Now Leary was asserting, with purple epileptic emphasis, that he would fly and fight no more. He was to go home, we learned later that day. And so he did and lived to become a cop in Philadelphia.

The rest of us, left to refresh ourselves amid the delights of Blackpool, felt our throats constrict with Leary’s. We commingled our fears in long unspoken dialogues, inarticulate as the plop and twang of the lobbing of our tennis balls on the clay courts.

My mind’s eye sees Blackpool as fully inhabited yet deserted like a beach resort out of season. The shops have merchandise in the window left over from a summer that has passed. Chill winds blow scraps of dead newspapers across the boardwalk. A soft malaise hangs in the air around the red-brown brick of the crenellated pseudo-Gothic castle that is the scene of our rest and recreation.

The pubs are warm and cozy, but the conversation is like the fluttering of the dead newspapers on the boardwalk. There are pretty girls in the pubs. I see them clearly, but I think I was restrained by thoughts of Esther’s labor and the impending arrival of my child. Who would screw in the presence of his baby?

Bohn had his own inhibitory mechanism, and so we talked with tennis balls, plunking the gut of a racket, plopping on the clay, until we had talked ourselves out.

When we mentioned the war we talked as civilians and strategists do, as if it were all a matter of grand movements by armies and navies, of encirclements and flanking maneuvers, of siege and statistics. The U.S. Army was battling its way inland from Salerno. Montgomery’s Eighth Army was inching up the Calabrian toe. Field Marshal Rommel was flooding northern Italy with German troops to replace the wavering Italians. We could not know that Rommel even then was conspiring with the Oberburgomeister of Stuttgart to overthrow Hitler, unlock the concentration camps, construct a liberal facade and lead the Western world against Russia. If we had known, would we have spared Stuttgart to save the promising Oberburgomeister? And would we in Blackpool, concerned with our own drowned Tondelayo and with our odds for survival – would we have discussed such fascinating matters with the animation we can so easily muster now after thirty-five years of civilian life? I doubt it, for war is not a matter of news bulletins. It is the image of oneself inside a plane at the bottom of the sea. It is the face of an epileptic seizure. It is that shameful zest that death gives to life. It is not, assuredly, grand strategy.

Our conversation was confined to tennis sounds and the swish of curling waves on a bleak strand. We rode in a horse-drawn buggy with girls whom we caressed abstractedly. Photographers sold us snapshots of ourselves, the whereabouts of which I do not know, but I fancy that they still blow endlessly across the boardwalks of Blackpool.

It was on the last day of our rest and rehabilitation that a cablegram arrived telling me that I had a daughter. The information came complete with the usual statistics such as weight, as if she were a prize fish. Whether it was an error of transmission or my addled brain, or my unfamiliarity with babies, I do not know, but I cabled back to ask whether “14 pounds 6 ounces was good weight for one so young.” We drank to her and to Esther. The crew – or what was left of it – felt, and still feel, a proprietary interest in that daughter because it was for her sake they had chosen to take their chances with the sea rather than fly to the safety of Switzerland.

I wrote my daughter a letter and another to my wife, wore fatherhood as a poppy in my buttonhole, and climbed aboard a plane sent down to fetch us home to Kimbolton.

Three days later we were over Emden, where a German battleship we had not expected to find in the harbor tossed up something like a rocket. We brought home Duffy’s Tavern with gaping holes in wing, nose and fuselage. It was my seventeenth completed mission. Counting all the false starts and aborts it was very likely my fiftieth venture into battle. Half the original crew were no longer with us – though Mike would soon return. Three quarters of the original squadron were missing or dead or had withdrawn from combat.

I had a third of the way still to go to the magic number of twenty-five. All the military portents spoke of a bloody autumn to come.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

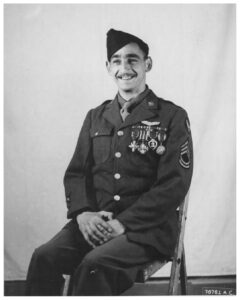

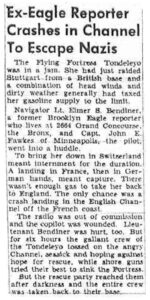

Presumably because he hailed from the Bronx, and, pre-war was employed as a reporter for the Brooklyn Eagle, a brief account of Elmer Bendiner’s experience in September of 1943 appeared in that newspaper, albeit over a year later: On December 6, 1944. Here’s the article as published in the Eagle, and, a full image of page 22, on which it appeared. As to why this news item appeared so long after the fact is a matter of conjecture.

The Eagle typically reserved its latter – or very last – page(s) for items covering news information about servicemen, or, casualty lists. This article was found via Tom Tryniski’s Fulton History website.

Ex-Eagle Reporter Crashes in Channel To Escape Nazis

The Brooklyn Eagle

December 6, 1944

The Flying Fortress Tondelayo was in a jam. She had just raided Stuttgart from a British base and a combination of head winds and dirty weather generally had taxed her gasoline supply to the limit.

Navigator Lt. Elmer S. Bendiner, a former Brooklyn Eagle reporter, who lives at 2664 Grand Concourse, the Bronx, and Capt. John E. Fawkes of Minneapolis, the pilot, went into a huddle.

To bring her down in Switzerland meant internment for the duration. A landing in France, then in German hands, meant capture. There wasn’t enough gas to take her back to England. The only chance was a crash landing in the English Channel off the French coast.

The radio was out of commission and the copilot was wounded. Lieutenant Bendiner was hurt, too. But for six hours the gallant crew of the Tondelayo tossed on the angry Chanel, seasick and hoping against hope for rescue, while shore guns tried their best to sink the Fortress.

But the rescue party reached them after darkness and the entire crew was taken back to their base.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Next post, Elmer Bendiner’s final mission, and, his quiet revelation.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Here’s the Book

Bendiner, Elmer S., The Fall of Fortresses, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, N.Y., 1980

Here’s Another Book

Freeman, Roger A., The B-17 Flying Fortress Story: Design – Production – History, Arms & Armour Press, London, England, 1998

Guess what? – Another book!

Forman, Wallace R., B-17 Nose Art Name Directory, Phalanx Publishing Co., Ltd., North Branch, Mn., 1996