My recent blog post, covering Sergeant Ralph Gans of the Bronx, included a list of Jewish soldiers who were military casualties on January 31, 1945. However, that list was not complete.

The names of two American airmen appear in this “separate” post, because one of those aviators – Leonard Winograd – recounted the events of his capture, interrogation, and imprisonment some three decades later, in an essay: “Double Jeopardy What an American Army Officer, a Jew, Remembers of Prison Life in Germany”.

He and his eleven fellow crew members were captured after their B-24 Liberator bomber failed to return from a mission to Moosbierbaum, Austria, on a day which marked the loss of at least thirteen 15th Air Force B-24s. They were members of the 512th Bomb Squadron of the 376th (“Liberandos”) Bomb Group (15th Air Force). The loss of their aircraft, B-24H 41-28911, piloted by 1 Lt. Robert E. Andrus, is covered in MACR 12066, and Luftgaukommando Reports ME 2776 and 2777. The entire crew of 12 survived, with two men evading capture.

Rabbi Winograd’s essay was published in the American Jewish Archives in April of 1976, and reprinted in The Jewish Veteran three months later.

It is presented here, in its entirety.

Rabbi Winograd’s story is one that is marked by elements of irony and humor (well, of a sort…) and more importantly, insights about the challenges and dangers (imagined, and also very genuine) of being a Jewish prisoner of war of the Germans. Let alone, the challenges of simply being a POW – “per se”.

Rabbi Winograd accorded notable attention to the predicament of fellow crewman T/Sgt. Gerald Einhorn, a substitute crew member who was filling in for the Andrus crew’s own (ill) ball turret gunner that January Tuesday. This was particularly so in light of Einhorn’s defiance of the crew’s German captors (which reaction elicited an intriguing comment from another POW) in the context of Einhorn’s status as a refugee from Hitler.

Though Einhorn was never seen again after being wounded during a strafing attack by P-47 Thunderbolt fighters, he did survive the war. The owner of a hardware store in Brooklyn, he died in 1983, at the young age of 61. His wife, Gertrude (“Gittel”) (Yaskransky) Einhorn, passed away in 2005.

One wonders if Gerald Einhorn ever read Rabbi Winograd’s story. I suppose the answer to that question can never be answered. What can be answered and verified is that Einhorn was, as recorded by Rabbi Winograd, from Eastern Europe; born in Romania in July of 1922, his parents were Samuel and Mathilda. Their fate is another question, the answer to which is also unknown.

In a larger sense, Rabbi Winograd’s account is one of the innumerable stories comprising the great body of writing – some fiction; some non-fiction; some, “some”-where between – concerning the experience of prisoners of war during the Second World War. In itself, this literature is but one facet of the vast body of writing covering the experience of prisoners of war, of all military conflicts, “in general”.

What is notable about Rabbi Winograd’s account is that was published relatively “early”, compared to the bulk of such accounts (whether books or articles), which began to appear before the public – at least in the United States – roughly commencing in the mid- to late 1980s.

What is equally notable is that it addresses – albeit through the eyes of one man, over the limited time-frame of four months (well, very much can happen in four months!) – the implications of being a Jewish prisoner of war in the European Theater, in light of the ideological priorities, social and geopolitical aims, and actions of Germany (and to a lesser extent its allies) concerning the Jews.

In that regard, it one among many such stories. But, how many?

From reviewing a very wide variety of sources – books and articles; archival and published; print and digital – I’ve arrived at the following approximate numbers of Jewish soldiers who, having been captured by Axis forces, survived the Second World War as POWs.

United States Army (European, Mediterranean, and Pacific Theaters): 1,530

United States Army Air Force (European, Mediterranean, and Pacific Theaters): 1,310

United States Marine Corps and Navy: 80

Australia (all theaters of war; all branches of service): 80

Canada (all theaters of war; all branches of service): 70

England (all theaters of war; all branches of service): 415

Greece: 70

South Africa (all theaters of war; all branches of service): 360

The Yishuv (pre-1948 Israel): 1,280

(A caveat: The above totals do not include Jewish prisoners of war from Belgium, France, and the Netherlands. They also do not include the extraordinarily few Jewish soldiers of the Polish, and particularly the Soviet armed forces, who survived German captivity. This must be viewed in the context and nature of Germany’s war against the Soviet Union, one aspect of which was the calculated inhumanity of German treatment of Soviet POWs.)

In any event, many if not most of these stories were probably never told; even fewer were probably recorded. Of those that were recorded, how many have been preserved?

Well…a few.

And this is one.

A link to a PDF transcript of Rabbi Winograd’s story follows this post’s list of references.

But first, begin with a series of photographs of the Andrus crew…

______________________________

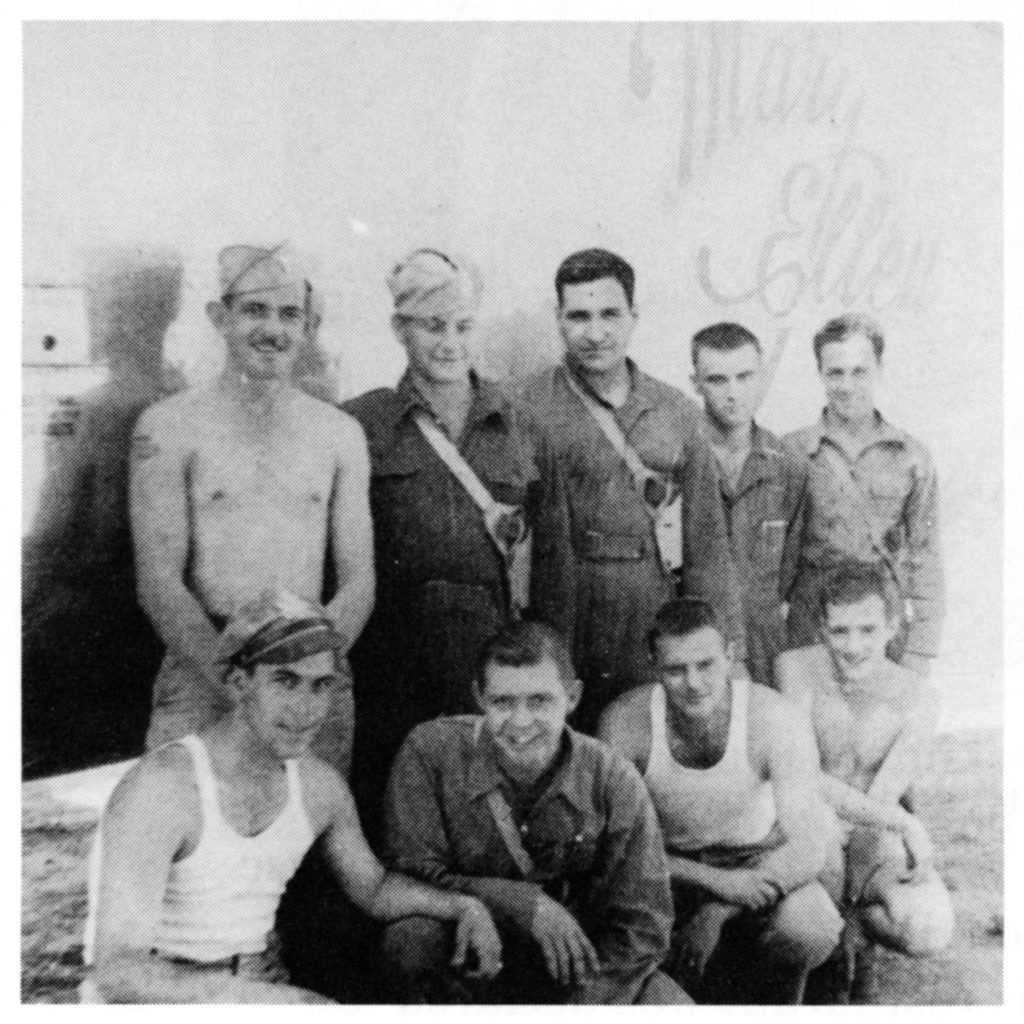

The following image, from the 376th Bomb Group wesbite, also appears in Rabbi Winograd’s book Rabies is Jewish Priests, and depicts his crew after their arrival in North Africa in August, 1944, while en route to Italy.

The men are the following:

Standing, left to right:

Bob Andrus (pilot)

Chappy Campbell (Radio operator)

Len Winograd

Bob Ruetsch (gunner)

Tom Sabatino (gunner)

Kneeling, left to right:

Bob Cartier (bombardier)

Lane Carlton

Carl Rudisill (gunner)

Bob Corbett (flight engineer)

The aircraft – Mary Ellen – was named after the wife of aircraft commander Paul George (not in the photo), who does not appear in the photo.

The same image as above, as it appears in Rabbi Winograd’s book.

The same image as above, as it appears in Rabbi Winograd’s book.

Mary Ellen, B-24J 42-50960, squadron number 85, did not survive the war. The aircraft was lost on November 11, 1944, while taking part in a high-altitude bombing mission to Mezzocorona, Italy.

Mary Ellen, B-24J 42-50960, squadron number 85, did not survive the war. The aircraft was lost on November 11, 1944, while taking part in a high-altitude bombing mission to Mezzocorona, Italy.

As described by 1 Lt. Eugene B. De Fillipo, who was flying on the plane’s right wing, Mary Ellen – piloted by 1 Lt. Walter W. Mader with a crew of ten – was last seen over the Adriatic Sea, about half way between Ancona and the Croatian coastal island of Dugi Otok. The two planes entered clouds at 0925 hours. Fifteen minutes later, when Lieutenant De Fillipo emerged into clear sky, Mary Ellen was missing. The incident is covered in MACR 9858.

______________________________

Another image of the Andrus crew, also from the 376th BG website.

Standing, left to right:

Robert F. Corbett – Flight Engineer

Robert J. Cartier – Bombardier

Robert E. Andrus – Pilot

Leonard Winograd – Navigator

Kneeling, left to right:

Carl P. Rudisill – Nose Gunner

Robert D. Ruetsch – Ball Turret Gunner

Thomas G. Sabatino – Tail Gunner

Emory L. Carlton – Waist Gunner

Robert G. Campbell – Radio Operator

______________________________

______________________________

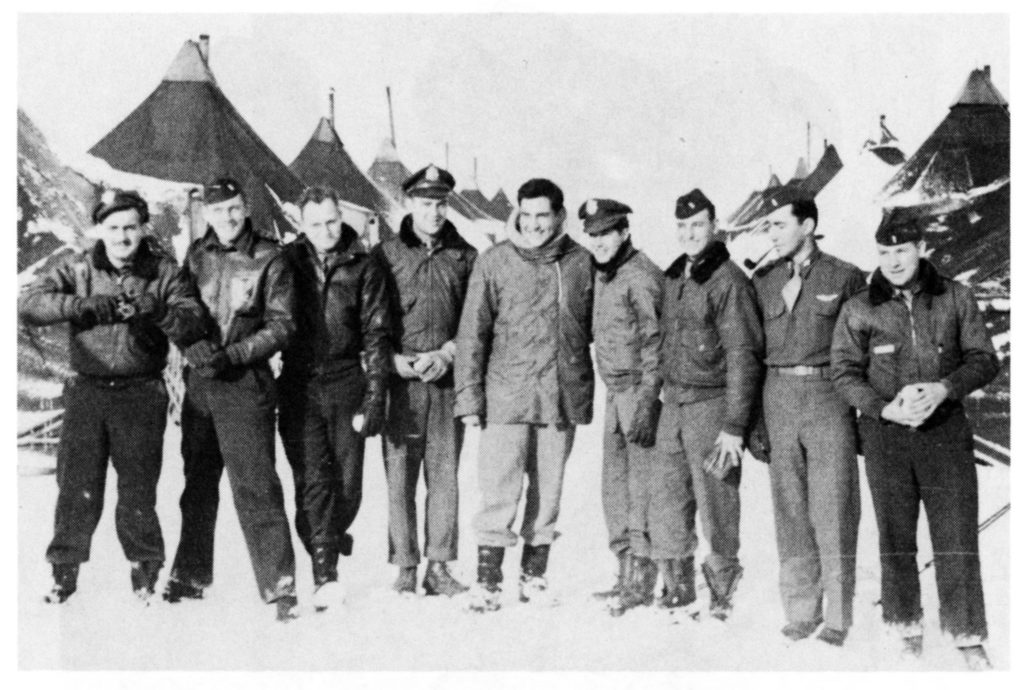

This image of the Andrus crew – taken just after their return from a mission on December 14, 1944 – is from the collection of Robert Ruetsch, seventeen of whose photographs are present at his photo page on the 376th BG website.

Standing, left to right:

Unknown

Leonard Winograd – navigator

Donald H. Boulineu – Pilot

Robert E. Andrus – Co-Pilot

Unknown

Kneeling, left to right:

Unknown

Unknown

Robert D. Ruetsch – Ball Turret Gunner

Unknown

Unknown

According to Robert Ruetsch’s comments, “these other men were probably part of the crew that day”:

Robert F. Corbett – Flight Engineer

Robert J. Cartier – Bombardier

Carl P. Rudisill – Nose Turret Gunner

Thomas G. Sabatino – Tail Turret Gunner

Emory L. Carlton – Waist Gunner

Robert G. Campbell – Radio Operator

The Liberator which serves as the backdrop B-24H 42-95285, squadron number 22, otherwise known as Red Ryder. The plane was lost during a mission to Linz, Austria, on November 7, 1944. Piloted by 2 Lt. Phillip R. Scott, the plane (based on my interpretation of the MACR) either crash-landed on Vis Island, or ditched in the Adriatic Sea. In any event, four of the plane’s eleven crewmen were killed. Three of the plane’s four engines suffered a simultaneous loss of power coupled with mechanical problems: #1 engine was “out”, #2 engine “ran away”, and a third engine had become uncontrollable. The incident is covered in post-war high-numbered “fill in” Missing Air Crew Report: # 16500.

The Liberator which serves as the backdrop B-24H 42-95285, squadron number 22, otherwise known as Red Ryder. The plane was lost during a mission to Linz, Austria, on November 7, 1944. Piloted by 2 Lt. Phillip R. Scott, the plane (based on my interpretation of the MACR) either crash-landed on Vis Island, or ditched in the Adriatic Sea. In any event, four of the plane’s eleven crewmen were killed. Three of the plane’s four engines suffered a simultaneous loss of power coupled with mechanical problems: #1 engine was “out”, #2 engine “ran away”, and a third engine had become uncontrollable. The incident is covered in post-war high-numbered “fill in” Missing Air Crew Report: # 16500.

______________________________

Here is another view of the Andrus crew, also from the Ruetsch photo collection.

Standing, left to right:

Robert J. Cartier

Robert D. Ruetsch

Leonard Winograd

Unknown

Robert F. Corbett

Unknown

Kneeling, left to right:

Donald H. Boulineau

Thomas G. Sabatino

Carl P. Rudisill

Robert G. Campbell

Emory Lane Carlton

Like Red Ryder and Mary Ellen, the B-24 in this image also did not survive the war. The plane B-24H 42-51183, was nicknamed Bad Penny, squadron number 27. The aircraft was lost during a mission to the Moosbierbuam Oil Refineries in Austria on January 31, 1945. Piloted by 1 Lt. Wante J. Bartol, nine of the bomber’s ten crew members survived the mission. The sole casualty was bombardier 2 Lt. Leonard N. Tocco, who was murdered (shot) by German soldiers almost immediately after safely landing by parachute, despite offering no resistance to capture.

Like Red Ryder and Mary Ellen, the B-24 in this image also did not survive the war. The plane B-24H 42-51183, was nicknamed Bad Penny, squadron number 27. The aircraft was lost during a mission to the Moosbierbuam Oil Refineries in Austria on January 31, 1945. Piloted by 1 Lt. Wante J. Bartol, nine of the bomber’s ten crew members survived the mission. The sole casualty was bombardier 2 Lt. Leonard N. Tocco, who was murdered (shot) by German soldiers almost immediately after safely landing by parachute, despite offering no resistance to capture.

The incident is covered in MACR 12067. It is also covered in Luftgaukommando Report ME 204A. Regarding the latter, Luftgaukommando Reports suffixed “A” probably pertained to American air crews from which at least some crew members were known by the Germans to have evaded capture. This would be consistent with the fate of the Bartol crew, for of the plane’s nine survivors, eight seem to have escaped, with T/Sgt. Mark D. Striman (radio operator) being taken prisoner.

______________________________

Another image from Rabbi Winograd’s book: “A group of the neighborhood children in Italy come out to play in the snow, January 30, 1945. It was the first snow in southern Italy in some 25 years. The two without hats are a future rabbi and a future university president. This was the day before our bomber went down. Who would have guessed that in less than 24 hours, our crew would be missing in action.”

______________________________

______________________________

Another image from the Ruetsch collection, showing Lieutenants Boulineau, Winograd, and Cartier, in front of their tent.

______________________________

______________________________

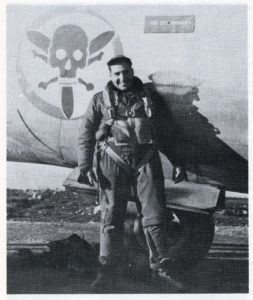

An excellent portrait of Rabbi (then, Lieutenant) Winograd, in front of a 512th Bomb Squadron B-24. The squadron insignia – a skull superimposed on a propeller and cross-bones – is as visually striking as it is symbolic. This picture accompanies Rabbi Winograd’s article in the April, 1976 issue of the American Jewish Archives, but does not appear in either Rabies is Jewish Priests, or, the reprint of the AJA article in the July, 1976 issue of The Jewish Veteran.

______________________________

A uniform patch of the 512th Bomb Squadron insignia.

______________________________

______________________________

The following account, from the 376th BG website, is Lt. Andrus’ story of the loss of B-24H 41-28911.

“With three engines feathered, the B-24’s flight characteristics approximate that of a large, round ball of lead dropped from a great height.”

Much to our surprise on the afternoon of Jan 30, 1944 [should be 1945] I found that my crew was scheduled to fly the next day’s mission. Under the normal rotation we should not have been scheduled for at least two more days. Further, we were to fly the number 7 (slot) position which was usually reserved for newer, less experienced crews. Adding to the confusion was the fact that we not going to fly our usual aircraft but were to take the brand new B-24H that the squadron had received a few days earlier.

All my efforts to find out what was going on were non productive. Sqd Ops finally told me that they had been directed by Group Operations to schedule me by name to fly that aircraft in the slot on tomorrows mission and I would probably find out why at the morning briefing. Very strange!

At the morning briefing I learned that the 376th would be the last group in the bomber stream, the target was Moosbierbaum and the flak would be intense. It quickly became apparent that since the 512th box was tail-end Charlie in the group formation, I would be the last ship over the target. It wasn’t until we arrived at the hardstand where our aircraft was parked that I finally found out what was going on.

Both the Gp Ops officer and the Gp Intel. officer were waiting for me and introduced me to my newest crew member: an aerial photographer. I was then briefed that my mission was to bomb the target with the 512th and when they rallied off after they dropped their ordinance I was to make a 180 degree turn and return to the IP and make another run over the target. It seems they suspected the oil refinery had long since been destroyed and was being camouflaged to appear operational. Our second run over the target would hopefully provide bomb damage photography taken before they had an opportunity to reemploy their camouflage. I was then advised that we had been selected to fly this mission because we were experienced and had one of the most competent navigators in the Group, Len Winograd.

The aircraft we were to fly was basically an “H” model that had been modified at the factory during its manufacture. The nose turret was eliminated and a huge, 7-lens mosaic camera which incorporated the bomb sight was installed in its place. The photographer had received over 150 hours of experimental training on a similar camera that had been installed in a modified B-24D back in the states. Although I was introduced to him at the hardstand, I am unable to remember his name.

He and Flight Officer Durham, the bombardier who was receiving his mandatory checkout flight brought the number of crew members on this flight to twelve.

The flight to the target was normal; the aircraft performed beautifully and fuel consumption was less than normal. There was absolutely no indication of the problem we were later to encounter. During this portion of the flight I briefed the crew on intercom about our additional mission. When I finished, there was a moment of silence and then a voice on the intercom said, “hey, I ain’t gonna go unless I get extra mission credit.” This brought on lots of laughter.

As I recall, the bomb run was flown at 23,000 feet and although the flak was very heavy, we received only minimum damage. After the bomb drop, the flight made a descending right turn to clear the area as rapidly as possible. I maintained 23,000 feet and flew a racetrack pattern back to the IP. Once we were established on the track back to the target I turned control of the aircraft over to the photographer who was using the bombsight as a view finder for the camera. While the flak continued to be heavy on this run, we received minimal battle damage.

After completing the photo run I made a right descending turn and picked up the heading for return to base. Almost immediately the right outboard engine started to fail. Fuel pressure fluctuated wildly and although the manifold pressure gauge indicated we were not getting any power, I was unable to control the engine RPMs. This left me no choice but to shut down the engine and feather the prop.

A check of the fuel sight gauges indicated plenty of fuel for the return to base. Despite this, all engine instruments clearly showed the loss of the engine was due to fuel starvation. Just as I made the decision to unfeather the engine, the same problem began with the right inboard engine. Using the feathering button to keep the RPMs from exceeding the max allowable we tried everything we could think of to overcome the power loss. Cross feeding the fuel tanks, swapping the electronic control boxes for the turbo superchargers all failed to correct the problem.

With two engines on the same side feathered, the flying characteristics of a combat configured B-24 left much to be desired. Forced to begin a descent in order to maintain minimum flying speed, I directed the crew to jettison everything in the aircraft not required to maintain flight. While I still held out hope that we would have sufficient altitude to make it over the Alps, the left inboard engine failed inexactly the same manner.

With three engines feathered, the B-24’s flight characteristics approximate that of a large, round ball of lead dropped from a great height. It was very depressing to know that we had all that fuel on board and not be able to access it.

By this time we were down in a box canyon of the generic Alps in northern Yugoslavia and descending through 9,000 feet. Since there was no alternative, I directed the crew to bailout. This was in the vicinity of Bijac, Yugoslavia. I was immediately captured and remained a POW for the duration of the war.

Liberation and return to allied military control came on April 29, 1945. In the latter part of May, 1945 while undergoing processing and rehabilitation at Camp Lucky Strike, LeHavre, France, I was interviewed and debriefed by US Army Intelligence agents. It seems that an identical camera-equipped B-24H had been delivered to the 98th Bomb Group at Lecce and it went down on its first mission under the same circumstances that we had experienced. This raised suspicions of sabotage and an investigation was conducted. It revealed that during manufacture someone had installed pressure-sensitive check valves in the main fuel lines to each engine. The valves remained inoperable until someone removed a small easily accessible pin to activate them. They were designed to remain open while climbing and maintaining constant altitude and close, shutting off the fuel supply, when encountering increasing barometric pressure i.e. a descending aircraft. The saboteur was apprehended and the valves were removed from the remaining four camera-equipped B-24s.

______________________________

And, here is Rabbi Winograd’s story…

DOUBLE JEOPARDY

American Jewish Archives

April, 1976

What an American Army Officer, a Jew,

Remembers of Prison Life in Germany

Dr. Winograd is a member of the Jacob Greenfield Post in McKeesport, Pa. He’s also the rabbi of Temple B’Nai Israel.

They were always things you overheard, things not meant for your ears, not intended for you, not directed at or about you. But the words were in the air. You could hear them at night in that tension before sleep released you from longing. I remember hearing two British or South African pilots talking about a British prisoner whose name may have been Gordon.

“Didn’t you know? He’s a Jew – a Russland Jew?”

“After the war, we’ll fight them.”

I will never know whether he meant that, after the war, England (or South Africa) would have to fight the Jews or the Russians. I heard one of us referred to as a “Kike” because he had argued with the German guards. His name was Einhorn. He was a refugee from Hitler. Hungarian Jews were dying at the rate of 12,000 a day at Auschwitz. Our own belly gunner was in the hospital with pneumonia so Einhorn, Hungarian Jew, had flown with our crew on the day we bailed out. Einhorn was unknown to me before this mission because at our base in Italy, officer flying personnel rarely got to know the enlisted flying personnel socially except, of course, for members of one’s own crew. Einhorn was apparently a fellow with enough guts to tell off the men who captured him or who were taking him on a train to yet another place. This frightened the other men who had been captured with Einhorn, as they were not personally involved in World War II, even if they, too, were prisoners of war in Germany. To the Jew this was deeply personal – no matter how hard you tried to deny it.

More of the One Than of the Other

We had bailed out over Yugoslavia after bombing a synthetic oil refinery somewhere in Austria. We came down in a part of Bosnia in which there was a great deal of guerilla warfare. Two of the crew were picked up immediately by the Yugoslav Tito Red Partisans. They were back at our base in Italy in five days. [Aerial Gunner S/Sgt. Carl B. Rudisill, and, Observer F/O Edward J. Derham] One of these two men was riding along on a first mission just to see what happens in combat. [Derham] He evaded capture, which indicates how much training, experience, intelligence briefings, and knowledge of escape procedure can accomplish. About five of the crew came down in about the same place and were picked up almost immediately. I think that Einhorn was in that group, along with the crew member who had griped to me that Einhorn was like “those Kikes from Brownsville.” [Name in MACR…] I was reassured that Einhorn was not like me. Another four men or so must have come down in another place because they were captured and brought in after the first group had left for Germany. I was the last one captured and I joined this group at a barracks in the mountains. My capture came after three days and two nights of hiding by day and traveling by night, avoiding all people and also wolves and bears who were after me and had me badly frightened.

The idea was that you hid in the daytime and traveled at night, heading always south until one came to a city or a penguin, in which case you had apparently overdone things again. But, while I was holed up in the snow, with tracks from my boots leading to the hole and no tracks leading from the hole, several German soldiers came by, looking for me, I assume. They had great big dogs with them. They walked within six feet of my hole and never bothered to investigate because, after all, no one wants to fill out all those forms, I guess.

Well, I saw a crucifix on a building and since I had heard about the priests and nuns in Belgium who believed in God and would help Jews trying to evade capture, I decided to chance it. I stood up. (I had been crawling on my belly because according to the movies, that way you became a smaller target.) I started walking toward what I assumed would be a church. Very soon I realized that it was no church at all. In those moments when I still thought it was a church, I had decided that all I would ask for was some hot water. I was freezing. Just some hot water. Very soon I realized that this was no church at all. It was a cemetery chapel. Some little children had seen me and had run to get the German sentries. Two German sentries. Well, Germans are nothing if not thorough. Imagine, two guards in a cemetery!

The guards asked me, Americano?” I answered, “No.” They asked me, “Italiano?” I answered, “Americano.” I felt that since Germany and Italy were allies, I had better hot tell them that I was Italian since I wanted them to like me.

They took me to meet an officer. It might have been a headquarters or an officers’ club or something. I was in a daze. But I remember that they immediately brought in an interpreter who right off the bat asked me if I had ever been to Kaufman’s in Pittsburgh. From the few words I had said, he had spotted my Pittsburgh brogue. The official questions came in correct order – name, rank, serial number, religion. I answered them all to the best of my ability, and when I told them that I was a Jew, I sensed excitement in the room. I am very perceptive that way. All the mouths were wide open now.

Then I remember that even though they kept referring to us as fellow officers, in my case it was not quite the same thing. The major (who was a German major in Bihacs in the winter of ‘45?) claimed to be from Vienna and told me that he had many Jewish friends (my knee jerk reaction being that one was supposed to beware of Gentiles who said that some of their best friends were Jews – as if it would be safer to be with a Nazi who said that some of his worst enemies were Jews!)

Studying Journalism

Meanwhile, they had insisted that I take off some of my wet clothes. This, I assumed, was for the purpose of torturing me. Then they brought me some hot soup – poison no doubt! Anyhow, the soup was about the best I ever ate in my life. It probably did not have the antibiotic potential of chicken soup, but no soup I ever ate tasted as good. As for the clothes, they merely wanted to dry them off. I had recalled the Geneva Convention when I created that sensation by telling them what my religion was, and so I realized that I had better not talk anymore. So I would not talk. The translator had gotten angry with me at one point when I answered a question before he had translated it, despite the fact that I knew no German at all, but, as I explained, German was a lot like Yiddish. Sometimes I could understand the questions without waiting for the translation. I imagine that a lot of German anti-Semitism came from translators who feared that if they were not needed in Yugoslavia, they might have to go to the Russian front where it was just as cold and hot besides. In wartime, that could be hazardous.

One example of how being a Jew affected response to interrogation: When I was asked what I was studying in college, I was ashamed to tell the Germans that I was in the School of Business Administration because in those days anti-Semites thought that all Jews were rich and were in business. So I told them that I was studying journalism. (This only shows how naive I was. Now they could accuse Jews of trying to control the media!)

But from that time on, I was intent on hiding within my group. None of my crew ever discussed this with me nor did I tell them what was on my mind. I always sought the back of formations, covered my face with my hands like a criminal whenever I was visible to Germans, and tried very hard not to be conspicuous.

Our select group soon included a South African pilot with the fantastic name of Paul Kreuger [actually, Lieutenant Peter Krueger (207053)] and there was also a South African observer whom we had seen get shot down one day as Ukrainian SS stood over me with whips in their hands while I cowered on the floor in hopes that they wouldn’t use them. (No congregation really frightens me.) We were escorted by three old men who were given rations for our trip to “someplace.” They kept our cigarette rations for themselves, but did give us enough food and a lot of organic fertilizer. We knew that they were stealing our cigarettes, but we were like Lolita with Humbert. They were all we had. They were kind of old, and we were extremely young, so we carried the guns and they carried the rations. After all, if we escaped, could they eat guns! They wanted to be sure that they would have enough to eat.

The boys from the 512th Squadron of the 376th Bomb Group were carrying German rifles while their guards carried the heavy packages of food. We called them Superman No. 1, Superman No. 2, and Sleeping Jesus. The names had come about so innocently! Bobbie Johnstown was a nineteen-year-old co-pilot who had the face of a Gerber model. We had to carry him everywhere because of his frozen feet. He couldn’t walk. He could run like hell when we were being bombed by our own planes, but he couldn’t walk, so we carried him. Well, it was one of those moments when our guards were totally exhausted. Bobbie had referred to them as “Supermen.” When we gasped, he asked, “Well, aren’t they?” It was all very funny, especially that part about Sleeping Jesus. I, of course, as the Jew in residence, never referred to the Alsatian guard as sleeping Jesus. I left that for the other crew buddies, it wasn’t for me to say. Anyone could tell that I must have been a Jew. I didn’t joke about Jesus. See why it is dumb to object to the Gentile who says that some of his best friends are Jews. If you are any kind of a Jew at all, everyone knows it. For one thing, you don’t joke about Jesus.

On the trains, our guards were supposed to protect us from the German populace. One of these guards, Superman No. 1, had an uncle in Milwaukee. This guard told a German passenger combat soldier that I was a Jew. The soldier gave me a cigarette without comment and without any show of anger or hatred. And cigarettes were very scarce in that time and place.

Big Generals and Jews

Finally, we arrived at Frankfurt on the Main. We went directly to the cellar of the railroad station to sweat out a night bombing. There we met a Russian prisoner, a Pole, and several Frenchmen. We joked that the Russian had surrounded Vienna, but the German army had apparently broken his siege and captured him. Seriously, though, it was quite touching. The Russian, on learning that I was an American, took out a silver cigarette case and held it close to his body so that I could not see what was in it. What was in the silver cigarette case? About a half dozen cigarette butts. For some reason, he did not want me to know that he was giving me the largest cigarette butt he owned. It could have meant many things, but it was wonderful to taste the appreciation of an ally.

A few minutes later, euphoric because of the swig of wine which I had gotten from the newly captured French prisoner, I opened my heart a fraction of an inch to him. I really thought that all Frenchmen were libertarian, egalitarian, and fraternal, like in Warner Brothers war films. So I told this brand new comrade in incarceration that I was a Jew and that I was afraid that they would kill me. Then he let me know that he could not believe that I was a Jew because I was a soldier. Just about then the German who was guarding the Russian, the Pole, and the Frenchmen became chummy and philosophical. Being in a cellar during an air raid does that for you. War, he said, was no good. We all agreed. Then he went on to refine his statement. War, he now said, was good only for the big generals and the Jews. It had been different at the prison camp for French prisoners in Vienna. A French POW there had been in Poland and had seen the Nazi death camps where Jews were exterminated, and he had told me what was going on. He probably would not have agreed that war was good for the Jews.

Finally, we left the cellar of the railroad station and went to an air force interrogation center near Frankfurt. I was put in solitary confinement. We all were, I think. They made the room so hot that I could not stand it and so removed most of my clothing. As soon as I did that, they made it so cold that I had to put all the clothing back on again. This happened several times over several hours. Then I was taken to interrogation where, for the first time, the fact that I was a Jew became a weapon in the hands of the Germans. By now I had been a prisoner for about a month.

The interrogator was a one man Mutt-and-Jeff act. You know, in prison work, one detective is the good guy and one is the bad guy. Well, this was the good guy. The bad guy would bet me if I did not play along with the good guy. It worked like this: I refused to give any information other than my name, rank, and serial number. I refused because the Geneva Convention promised that no one was allowed to require more than such information of me. All he wanted was for me to tell him one thing to establish the fact that I was not an underground terrorist or, as he put it, a “bandit.”

Sorry. No luck.

So, he went on to tell me how he had had good childhood friends who were Jews, but who had gone to America because of the Nazis. He, of course, was no Nazi. Perhaps I knew his friends? He told me their names. No, I did not know them. Well, the officer explained, that was too bad because he certainly had nothing against Jews, but the Gestapo was in charge of all suspected underground terrorists and, unless I talked, he would have to turn me over to the Gestapo. He advised me that they would not be as considerate of my feelings or my safety as the German Air Force would be. If I could get myself registered as an air force prisoner of war, the Luftwaffe, the German air force, would be responsible for me. Otherwise, the Gestapo would get me. This was the second big fact about being a Jew in this situation. It gave the Germans an additional weapon for interrogation of prisoners. I told him that I could not do what he wanted me to do. He then had a photographer brought in who did a frontal mug and profile with numbers. This, I was told, was for the Gestapo. The interrogator’s last words to me were that he felt very sorry for me. He really did not think that I was an underground bandit, but I had been very foolish and had not helped him at all.

I went back to my room thinking or really feeling kind of, “So, this is how it is all going to end,” and being afraid only that I would not act like a big boy when they tortured me. I had been well indoctrinated with the idea that if you revealed anything at all other than your name, rank, and serial number, they would never let you out of the interrogation center. Apparently, those interrogation centers existed only for the sake of the occasional blabbermouth who would give them one small piece of a puzzle which they could fit into a larger puzzle where it would mesh with the gleanings from other blabbermouths. Anyhow, they would have no further use for me because I would not tell them anything. I could always say that I had met the enemy and “my head was bloody but unbowed” – except that it wasn’t even bloody. It was cold and it was sweaty, but it was not at all bloody.

After an eternity, which may have been only fifteen minutes, there was a knock at the door. A German NCO with a smile on his face said, “Lt. Winograd we are sending a movement of prisoners today to a Red Cross camp and would like you to be in command of the group.” He told me how many hundreds of officers and NCOs would be involved. I agreed to do it. He explained also that, looking as I did, I could not properly command men. I needed a shave. Would I like to use his razor and soap? I agreed to do that, too. So he brought me a razor, soap, and a brush, and while I was shaving, he explained that I would have to do something else to guarantee the comfort of our men. According to the articles of war, you are not allowed to force a prisoner to give his consent or parole, meaning you cannot force a prisoner to give his word that he will not attempt escape. I would have to violate the entire civilized world’s conception of POW life and give parole for several hundred prisoners. If did not? If I refused? Then winter, shminter-they would remove the shoes and belts of all the men on the train! But supposing I gave parole for these men and one of them escaped? Oh, in that case the Germans would shoot me. Seemed like an air-tight plan! I love to see all the ends dovetail neatly.

But look. When you have been expecting the Gestapo to take you off somewhere to a torture chamber, a minor violation of an international covenant is insignificant. I agreed. He also explained that the German people were extremely sensitive people. Well, who didn’t know that? He meant that they were sensitive about their homes being bombed, so there was to be no laughter, no frivolity, no singing in the presence of German civilians. If there were, there might be an attack on the prisoners by the civilians, and I would be responsible for that, too. Looked like a good setup for me to lose weight. I agreed, of course. Then I was taken to a large room, and all of the prisoners were brought in, including a few members of my own crew who looked at me with awe and wonders as though it were my bar mitzvah. You know the look: Lenny is going to make a speech!

Beschnitten

I explained the conditions of the trip. We were going to a Red Cross center for war prisoners where we would receive new clothing and the other toilet articles and supplies we would require for our new life. Then I had them arrange themselves into a military formation, and I marched the group to the train from the building. I have no idea how far we went but Jeez that was fun! So another peculiarity of being a Jew in a German POW camp was that the only time in my three years of active duty in the Armed Forces of the USA that I ever commanded a marching formation of any size or of any kind whatsoever was at that prison interrogation rogation center in Nazi Germany where it was either a reward for being a brave or an impressive soldier or, an attempt at harassment so that I should not enjoy the train ride like everyone else.

At the Red Cross place – Wetzlar, I think it was – the commanding officer explained that we would get the things we needed. He suggested that we all watch the maps for an American crossing of the Rhine River any day now at a certain point. He informed us that there would be “mass for the mackerel munchers at 6:30 and services for the other league at 8 o’clock.” We would have some papers to fill out for the Red Cross. I realized that the Red Cross had nothing to do with these papers when the uniformed German filling out my information sheet insisted that I had a “birth mark or scar” which was beschnitten – cut off. This, he explained, was because I was circumcised. That was my identifying birthmark or scar.

From Wetzlar we went to Nuremberg. It was at Nuremberg that we were finally home. They had been telling us that, “For you the war is over.” They told us that again. As prisoners, now that the war was over for us, we slept in cellars and in barns, and once I awoke at night to find a large rat sitting on my face, staring at me. Now we were safely registered as prisoners, and the food was just enough to keep one barely alive. Men fell into the latrines and lacked the strength to pull themselves out of the fecal slime. For them the war really was over. A most appropriate way to go. We were home. We were safe from the civilians who tried to grab us in Vienna when my own bomber group attacked the city just as we reached a Red Cross soup kitchen. There was not enough to eat, but Nuremberg was something to be proud of. After all, it was the only major bombing target that could be reached by both the entire 15th Air Force based in Italy and the entire 8th Air Force based in England. We were bombed all day by the Americans and all night by the British. But they were not bombing our prison. They were bombing other things such as rail junctions.

A Moment Embedded in Stars

In the midst of this confusion, one night the British sent the whole damned Royal Air Force to bomb, and they dropped flares right on the camp, which meant to us experienced air men that we were the target for tonight. Actually they had dropped the flares so their bombardiers (bomb-aimers, they called them) would not hit us, but would hit the rail junction about a mile away. We did not know that though, and so we thought that we were it. I prayed for my mother, my father, my sister, and my brother as was my custom. I sensed that I must not be selfish or God would ignore me altogether. And I lay in that filth on my belly on the floor of the barracks and told God that if He could get me out of that mess I would dedicate my life to Him. That was when I decided to become a rabbi. Seriously, that was it. I joke a lot, especially in anxiety-laden situations, but I am serious about this moment and the rabbinate.

Finally, the day came that we marched out of Nuremberg because the American infantry was getting too close. On the first or second day of our long march, we were attacked by American P-47 dive bombers. Einhorn had his leg ripped open, and I never saw him again. Our next camp was Moosburg, which we reached after marching mostly in the rain for something like 125 kilometers (eighty-five miles), sleeping at night in the open or on farms or in bitterly cold churches. When no one else would have us the churches always would let us in out of the rain. The Germans, during this march, were neither mean nor cruel. They were kind and helpful. Can you handle that last sentence? We must have looked horrible. Old ladies carried buckets of water for us and brought us food. We were everywhere throughout the countryside. A hundred thousand of us. Finally, I arrived at the desk of the British prisoner whose job was to fill out a new informational form on me. All of the old records had been lost. We found them a couple of weeks later. This British prisoner asked me again the same weary questions I had answered so many times before. I answered them again.

I did not want to give my parents’ address, as I always feared that they might be blackmailed by German agents in the United States. Still, I did give the address of my parents because, after all, there was no way to write home without addressing the postcards. But when I told this man that I was a Jew, he said that he would not write that down because he had been a prisoner for five years and had seen too many Jews disappear.

We were now only twelve miles from Dachau, where the Germans had been known to separate Jews from the other military prisoners. I answered that I would not lie about my Jewishness. He suggested that he write down Protestant for my religion. I refused. He told me that I was signing my own death warrant. I told him that I had not come halfway around the world to lie about my religion; that was what the war was all about, and if I did what he asked and we won the war, I would still be the loser. He wrote it down and told me that he was sorry for me. I know that he meant that. I felt his pain. I didn’t smile either. I was out of the habit.

A nun in Philadelphia has written, “Hope is a moment embedded in stars that shine when your courage is gone.” A few weeks later we were liberated.

______________________________

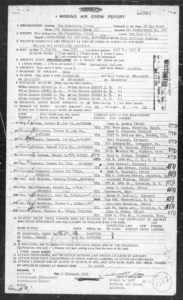

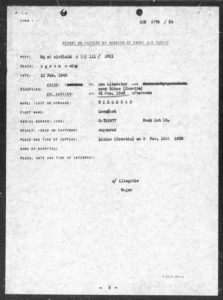

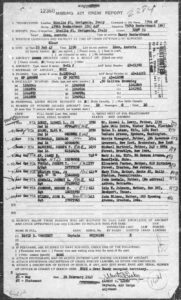

Here are some images of MACR 12066, which covers the loss of B-24H 41-28911.

Information about the mission, technical information about the aircraft, and information about the plane’s crew appear below.

As mentioned by Rabbi Winograd, two crew members escaped capture. One was S/Sgt. Carl B. Rudisill, an aerial gunner. Having returned to Allied lines by February 8, here is his report – based on then-available information – about the status of his fellow crew members.

As mentioned by Rabbi Winograd, two crew members escaped capture. One was S/Sgt. Carl B. Rudisill, an aerial gunner. Having returned to Allied lines by February 8, here is his report – based on then-available information – about the status of his fellow crew members.

Here is an English-language translation of the “Report on Capture of Members of Enemy Air Forces” form, which is typical of Luftgaukommando Reports. This report covers the capture of Lieutenant Winograd…

Here is an English-language translation of the “Report on Capture of Members of Enemy Air Forces” form, which is typical of Luftgaukommando Reports. This report covers the capture of Lieutenant Winograd…

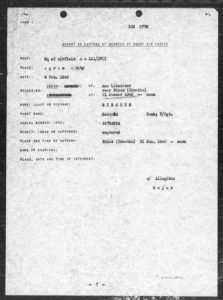

…while this report covers the capture of S/Sgt. Gerald Einhorn, who was serving as ball turret gunner. Note that Sgt. Einhorn was captured the day be bailed out – January 31 – while Lt. Winograd was captured on February 2.

…while this report covers the capture of S/Sgt. Gerald Einhorn, who was serving as ball turret gunner. Note that Sgt. Einhorn was captured the day be bailed out – January 31 – while Lt. Winograd was captured on February 2.

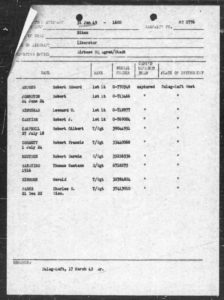

This document, dated 13 February, pertains to the transportation of several Allied POWs to Oberursel, including six members of the Andrus crew. Notable in the list is an entry for South African serviceman Lieutenant Peter Krueger (207053), named in Rabbi Winograd’s account as “Paul Kreuger”.

This document, dated 13 February, pertains to the transportation of several Allied POWs to Oberursel, including six members of the Andrus crew. Notable in the list is an entry for South African serviceman Lieutenant Peter Krueger (207053), named in Rabbi Winograd’s account as “Paul Kreuger”.

And, the final crew roster of 41-28911, generated by German investigators after identification and correlation of the captured airmen. Notably and understandably absent are the names of S/Sgt. Carl B. Robert Rudisill and F/O Edward J. Derham. They “got away”…

And, the final crew roster of 41-28911, generated by German investigators after identification and correlation of the captured airmen. Notably and understandably absent are the names of S/Sgt. Carl B. Robert Rudisill and F/O Edward J. Derham. They “got away”…

______________________________

______________________________

Biographical and genealogical information about Gerald Einhorn and Leonard Winograd follows below:

Einhorn, Gerald, T/Sgt., 32784824, Ball-Turret Gunner, Air Medal, Purple Heart

Originally member of 493rd BG (8th Air Force)

POW Camp unknown

Born in Romania, 7/18/22; Died 2/5/83

Mrs. Gertrude (“Gittel”) (Yaskransky) Einhorn (wife) [6/24/24-6/5/05], 577 E. 98th St., Brooklyn, N.Y.

Mr. and Mrs. Samuel and Mathilda Einhorn (parents) (presumably remained in Rumania during war; eventual fate unknown)

Married 1/25/43

Postwar, owned a hardware store in Brooklyn

Died 2/5/83

Buried at New Montefiore Cemetery, Farmingdale, N.Y.

American Jews in World War II – 301

Winograd, Leonard, 1 Lt., 0-712977, Navigator, Air Medal, 3 Oak Leaf Clusters, Purple Heart

POW at Stalag 7A (Moosburg, Germany)

Mr. Emil Winograd (father), 299 Jackson St., Rochester, Pa.

Casualty List (Liberated POW) 6/7/45

American Jews in World War II – 560

______________________________

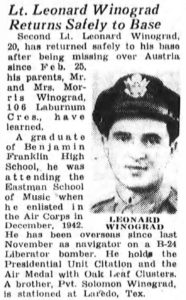

Coincidence upon coincidence: There was another Leonard Winograd who served in the Army Air Force in World War Two.

He was an aerial navigator.

He served on B-24s in the 15th Air Force.

His aircraft was lost on a combat mission.

He, and his entire crew, survived the war.

This “other” Leonard Winograd, who hailed from Laburnum Crescent, in Rochester, New York, was the son of Morris Winograd, and the brother of Pvt. Solomon Winograd.

His aircraft, B-24J 42-51382 of the 758th Bomb Squadron, 459th Bomb Group, piloted by 2 Lt. Lionel L. Lowry, Jr., failed to return from a mission to Linz, Austria on February 25, 1945, the plane’s loss being covered in MACR 12360. Though I do not know the details, I would assume that the men returned to their squadron with the aid of Yugoslav partisans.

A brief article about Lt. Winograd from the Rochester Times Union of April 18, 1945, appears below, followed by the crew list.

______________________________

______________________________

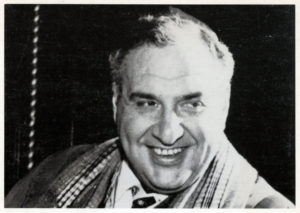

Postwar: Once Lieutenant Winograd, now Rabbi Winograd. (Portrait from Rabies is Jewish Priests)

______________________________

______________________________

References

Books

Dublin, Louis I., and Kohs, Samuel C., American Jews in World War II – The Story of 550,000 Fighters for Freedom, The Dial Press, New York, N.Y., 1947

Winograd, Leonard, “Double Jeopardy: What an American Army Officer, a Jew, Remembers of Prison Life in Germany,” American Jewish Archives, V 28, N 1, p. 3-17

Winograd, Leonard, Rabies is Jewish Priests – And Other Zeydeh Myses, Leonard Winograd, Pittsburgh, Pa., 1990

Gerald Einhorn

Mention of Gerald Einhorn serving in 493rd Bomb Group (at American Air Museum website)

Robert Andrus

Robert Andrus’ Account of loss of B-24H 41-28911 (at 376th BG Website)

Robert Andrus Crew Members

Crew Photo – North Africa, in front of B-24J 42-50960 (Mary Ellen) (at 376th BG website)

Crew Photos from collection of aerial gunner Robert D. Reutsch (at 376th BG website)

Crew Photo – Wearing uniforms in front of building (at 376th BG website)

Crew Photo – In front of B-24H 42-95285 (#22 – Red Ryder) (at 376th BG website)

Crew Photo – In front of B-24H 42-51183 (#27 – Bad Penny) (at 376th BG website)

Crewmen – Donald H. Boulineau, Donald H., Leonard Winograd, and Robert J. Cartier (at 376th BG Website)

A PDF transcript of Rabbi Winograd’s story is available here.