“…I now know that my job in this world is not yet done…”

“As I said at the beginning of this somewhat long winded narrative

my object in writing this story is that you may be able to inform their people

and the story itself brings out how well they all did their job

even when faced with death and how they actually gave their lives doing their duty.”

____________________

Men write for different reasons. Some, to communicate the driest of information, whether vocationally or professionally. in the most nominal sense. Some, to express feelings and emotions that form a natural bond with friends, lovers, family, and even the larger world. Some, to accurately and minutely record their life experiences – whether mundane or unprecedented; to create compelling works of fiction; to describe the world in verse, all with the aim of placing their words before the public for recognition, and (if so favored by lady fortune…?) compensation.

And, there are some, for reasons perhaps arising from happenstance, who are compelled to write simply to place their memories – even of events brief and fleeting – before the world, not for themselves, but for the sake of human memory.

__________

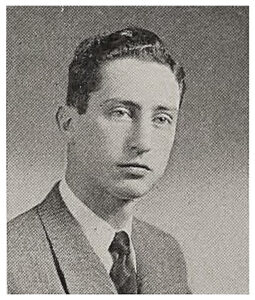

The Canadian Jewish Congress’ 1948 two-volume compilation of biographies of Canadian Jewish soldiers (straightforward title! : Canadian Jews in World War II) is comprised of two volumes, one pertaining to servicemen who received decorations for military service, and the other for servicemen who died during the war, whether through action with enemy forces, in training, accidentally, or other circumstances. Generally, the biographical profiles of the many soldiers covered in these two volumes comprise nominal biographical information about a soldier and his family, his prewar war, and naturally, the events surrounding his military service. The majority of the biographies are accompanied by photographic portraits (half-tone, naturally – we’re talking late 1940s technology, after all!) which lend a sense of reality to these accounts and carry them beyond a dry and rote recitation of mere historical “data”. Overall, the Canadian Jewish Congress did magnificent work in the creation of these two works, taking them to a level of detail vastly beyond that from the nominal state-by-state lists of soldiers’ names in American Jews in World War Two. (Though in fairness, the body of documents the Canadian Jewish Congress had to work with was orders of magnitude less than the number of records held by the American National Jewish Welfare Board.)

Though I’ve extensively reviewed Canadian Jews in World War II in an ongoing effort to identify Jewish military casualties in WW II, recently (how recently? – I’ve no idea!) another source of information about Canadian WW II military casualties (specifically, servicemen who died during the war) has become available. These are Casualty Files for Canadian WW II personnel, which have been made available through Ancestry.com. These documents are of enormous value in terms of genealogy and military history. Though they have no exact analogue – “data-wise” – in terms of the design of American military records, they might be considered as being a composite of the information carried in Attestation Papers for soldiers in the armed forces of the British Commonwealth, plus – from the American perspective – Individual Deceased Personnel Files, and (in the case of aviators) Missing Air Crew Reports. Some of the Casualty files include photographic portraits; a few (for example, for Flying Officer Philip Bosloy, a ferry pilot missing over Nova Scotia on February 24, 1943) include newspaper articles; many include correspondence – whether handwritten original or transcribed – by family, friends, comrades, and others.

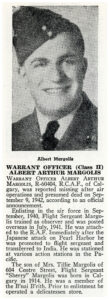

Which leads to the impetus for this post: My search for records concerning Flight Sergeant Albert Abraham Margolis (R/60404) of the Royal Canadian Air Force.

Here’s his biographical profile from Volume II (page 48) of Canadian Jews in World War II. Though the information in his biography is nominally complete, additional details comprise his date of birth: July 29, 1914; his parents’ full names: “Benjamin Max” and “Tillie (Russuck) Margolis”; the report of his “Missing” status in The Jewish Chronicle: October 16, 1942; the memorialization of his name: on Column 420 of the Singapore Memorial, in Singapore.

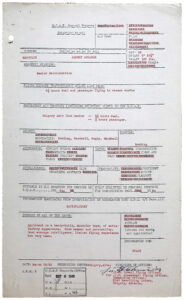

This document’s from his Casualty File: It’s an Interview Report of the kind typically compiled for applicants seeking service as air crew members in the RCAF. Note the fields for “Sports” (first), followed by “Appearance”, “Dress”, “Intelligence”, and “Personality”; and especially, the “Summary” section at the bottom of the form. Albert A. Margolis is described therein in these terms: “Applicant is a heavy-built, muscular type, of satisfactory appearance. Slow manner and personality. Good average intelligence, limited flying experience but very keen.”

As suggested by Albert Margolis’ Interview Report, comments in the Summary Section are frank and direct. In terms of Jews who applied for service in the RCAF, Interview Reports are a window upon the perception of Jews in the Canadian military (and probably not just the Canadian military) in the social and cultural context of Canadian society the early 1940s. Of the comments in Interview Report Summary Sections in the seventy-odd Casualty Files (available via Ancestry.com) I’ve reviewed for Jewish members of the RCAF, most simply focus on those attributes – intelligence, personal rapport, attitude, bearing, enthusiasm, and participation in individual or team sports (that’s a big one) – that would reflect upon most any applicant’s suitability as an air crew (read: team) member, which in effect are pertinent to most any military leadership position. A few Interview Reports definitely allude to an applicant being Jewish, typically in a word or two that accompanies more extensive commentary – whether negative or positive (and sometimes, very positive) – about to an applicant’s suitability for service in the RCA. Other Interview Reports, like that of Albert Margolis’, do not, at all.

____________________

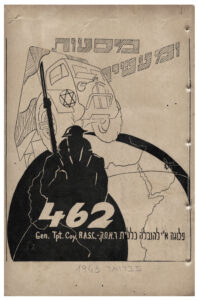

F/Sgt. Officer Margolis’ biographical profile in Volume II of Canadian Jews in World War Two is absent of specific information about the mission on which he was missing. However, though I don’t presently have access to Squadron Summaries or Squadron Records for No. 62 Squadron, this question is largely – albeit not completely – answered by information in Margolis’ Casualty File: He was the observer of an aircraft that was shot down during an attack against Japanese shipping in the harbor adjacent to Akyab, Burma, on September 9, 1942.

First, let’s start with a copy of a letter sent from the Royal Canadian Air Force Casualties Office to Abraham’s mother Tillie in mid-February of 1943:

2152

12th February 1943

C7/CAN/R.60404

Dear Madam,

With reference to the letter from this department dated 16th October 1942, I am directed to inform you, with deep regret, that all efforts to trace your son, No. CAN/R.60404 Flight Sergeant Albert Abraham MARGOLIS, Royal Canadian Air Force, have proved unavailing.

The aircraft of which your son was the Observer took off from base at 10.20 a.m. on 9th September 1942, in conjunction with other aircraft, to carry out an attack against enemy shipping in the harbour at Akyab, Burma. Enemy aircraft were encountered over the target area and your son’s aircraft was seen to break away from the formation, losing height. Your son’s aircraft failed to return to base and nothing further has been heard of him.

In view of the lapse of time, it is felt that there can now be little hope of his being alive, but action to presume that he has lost his life will not be taken until at least six months from the date on which he was reported missing. Such action will then be for official purposes only, and you will be duly informed.

Meanwhile I am to assure you, with the sincere sympathy of the department, that all possible enquiries will continue to be made.

I am,

Dear Madam,

Your obedient Servant,

for Royal Canadian Air Force Casualties Officer,

for Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief R.C.A.F. Overseas.

Mrs. H. Margolis,

604 Centre Street,

Calgary, Alberta,

CANADA.MH.

____________________

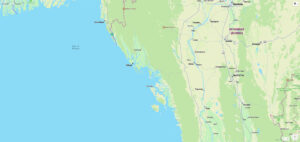

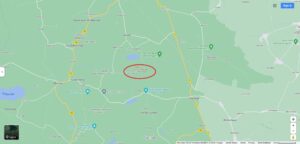

Here’s an Apple Map of the location of Akyab (now known as Sittwe), showing its position on the western coast of Myanmar. The city “…is the capital of Rakhine State, and located on an estuarial island created at the confluence of the Kaladan, Mayu, and Lay Mro rivers where they empty into the Bay of Bengal.” The Bay of Bengal lies to the west, while to the northwest and out of map view, is Bangladesh, which during the year in question – 1942 – would have been part of Colonial India.

____________________

This 1:7500 scale map of Akyab, produced in December, 1944, shows the city’s location at the confluence of the three rivers, with its waterfront “facing” east. The map, “A town map of Akyab (Sittwe)”, from the National Library of Australia, can be found at COPP (Combined Operations Pilotage Parties) Survey. As stated in the legend, this map – a first edition of December, 1944 – was drafted based on aerial photographs taken in November of that year. Designated “HIND 1036 AKYAB”, the map was “compiled, draw and printed by Survey Directorate, Main Headquarters, ALFSEA.” (Australian Land Forces South East Asia?)

____________________

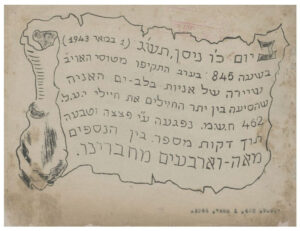

Further information about F/Sgt. Margolis’ fate would wait until August of 1945, when his sister, Miss E. Pearlman, of Regina, Saskatchewan, received a letter from the Royal Canadian Air Force Casualties Office. This revealed that a certain “Pilot Officer White” was the sole survivor of the mission, with Margolis and White’s fellow crewmen (P/O George O. Maughan and Sgt. Neil McNeil) having been killed, the three men’s casualty status now having been changed to “missing believed killed”. This revelation was based on an account of the mission clandestinely written by F/O White while he was a prisoner of war of the Japanese, in Rangoon. Tragically, he was killed in an Allied air raid on November 29, 1943. Miraculously, the document was preserved. Postwar, the document was sent to F/O White’s wife, who in turn forwarded it – I presume a copy and not the original – to the overseas headquarters of the Royal Canadian Air Force Casualties Office. A transcribed copy of the story was then sent to F/Sgt. Margolis’ family (as well as, I’m sure, the families of Maughan and McNeil). And so, almost four years after the fact, the crew’s fate was known.

Here’s the Casualty Office’s letter to Miss Pearlman…

OTTAWA, Canada, 14th August, 1945.

Miss E. Pearlman,

2330 Rose Street,

Regina Saskatchewan

Dear Miss Pearlman:

It is with deep regret that I must confirm our recent telegram informing you that Flight Sergeant Albert Abraham Margolis, previously reported missing on Active Service, is now reported “missing believed killed”.

A complete report which was written by Pilot Officer White, the captain of Flight Sergeant Margolis’s crew, prior to his death in a Rangoon jail as a result of an air raid, was received by his wife and forwarded to our Overseas Headquarters who passed it to us. This report states that Flight Sergeant Margolis, Pilot Officer Maugham [sic] and Sergeant McNeil, two members of the crew who were not of the Royal Canadian Air Force, lost their lives when their aircraft crashed. In view of this information Flight Sergeant Margolis is now reported “missing believed killed”.

I am deeply sorry that this information is so distressing and extend to you my deep and heartfelt sympathy.

Yours sincerely,

R.C.A.F. Casualty Officer,

for Chief of the Air Staff.

____________________

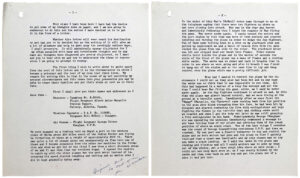

…and here’s a transcript of F/O White’s story. Interspersed between paragraphs are images of the Lockheed Hudson bomber, and, a video showing Hudsons on a training mission in England, in 1940.

White’s words:

Ever since I have been here I have had the desire to put some of my thoughts down on paper, and I am now going to endeavour to do this and the method I have decided on is to put it in the form of a letter.

Whether this letter will ever reach its destination or not has yet to be decided but as the writing of it will give me a lot of pleasure and help to pass away the seemingly endless days, I shall persevere. It will undoubtedly appear disjointed for I am often assailed with many and troublesome thoughts and in any case all thoughts when diagnosed are pretty disjointed, so I must ask you to bear with me and try to understand the ideas or expressions I am going to attempt to convey.

The first thing I wish to write about is quite apart from the rest of this letter and it is the circumstances in which I became a prisoner and the rest of my crew lost their lives. My reason for writing this is that in the event of my not surviving my present circumstances and this comes into your possession you may be able to trace their families and put their minds at rest as to their fate.

First I shall give you their names and addresses as I know them –

Observer – Canadian No. R.60404,

Flight Sergeant Albert Asher [Abraham] Margolis

Central Square,

Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

Wireless Operator – R.A.F. No. 110880,

Sergeant Neil McNeil – Glasgow. [CWGC: Son of Daniel and Mary McNeil, of Croftfoot]

Air Gunner – Flight Sergeant George Oliver Maugham [sic – should be “Maughan”], D.F.M. [CWGC: Son of Mr. and Mrs. J. G. Maughan, of Darlington, Co. Durham.]

We were engaged on a bombing raid on Akyab a port on the western coast of Burma about 200 miles south of the Indian Border and flying in formations of three at a height of approximately 2000 ft. There was quite a lot of clouds about and unexpectedly we flew into one of these and I became separated from the other two machines in the formation and when we got out of the cloud I saw them a short distance ahead of me and it was then that our troubles began. I opened the engines to catch up with the other planes but the port motor instead of increasing its speed started coughing and cutting and no matter what I did it kept gradually dying away.

____________________

This illustration, “box art” for Classic Airframes Hudson Mk. III/IV/V/VI/PBO-1 1/48 plastic model (kit #449) is a very nice depiction of a Hudson in flight. The aircraft shown is Mk I Hudson A16-25 of No. 1 “Malaya” Squadron of the Royal Australian Air Force. According to ADF Serials, this plane was lost at 2100 hours on May 7, 1941 over the Straights of Johore, during searchlight practice. The crew comprised F/Lt. A.R. Stevenson, F/O A.H. Brewin and F/O G.D. Robinson, Sgt. F.S. Gildea (403286) and Cpl. A.T. Thompson (2399).

____________________

In the midst of this Mac’s (McNeil) voice came through to me on the telephone saying that there were two fighters up above us and were closing into attack. Mac was in the rear gun turret and immediately following this I heard the crackle of Mac firing his guns. Mac never spoke again. I again opened the motors and the port engine by this time was more or less useless and started twisting and turning the plane in order to dodge the Jap fighters. One of them came belting down in a dive on my starboard side and pulled up underneath me and a burst of cannon fire from its guns rocked the plane from one side to the other. The starboard motor was hit and stopped dead and burst into flames. Other cannon shells burst inside the plane and in the matter of seconds the whole of the front of the plane was a mass of flames and a choking white smoke. The smoke was so dense and hard to breathe that in order to see where we were going and also to breath I was forced to hang out of the window and at the same time to try and keep control over the plane which was a pretty difficult job.

Even had I wanted to control the plane by the instruments I could not as they also had been hit and in any case the smoke was so thick that it was impossible to see them. All this had happened in a matter of a very few seconds and all the time I could hear Mac firing his guns, altho, as I said he never spoke again. As the Jap fighters continued to attack us and, by this time the plane was almost beyond control, and we were diving at the ground at a terrific speed. Immediately after we were first hit “Happy” (Margolis, the Observer) came rushing back from his position in the nose with blood streaming down his face, he had been hit by shrapnel and started combating the fire with extinguishers and kept fighting the flames in the terrific heat and choking smoke until we crashed and when I got his body out later he was still grasping a fire extinguisher In his hand. Simultaneously George (Maugham) who was operating the wireless immediately commenced a message to air base telling them of our plight and advising them of the rough position of where we would crash. One of the last things I remember was the sound of George transmitting continuous S.O.S. and then we crashed. My own part was a frantic endeavour to try and control the plane and as both motors had gone and the plane on fire I quickly realized that a crash was inevitable and my only chance was to try and make a crash landing. As I said the smoke in the plane was choking and blinding and all I could achieve was to poke my head out of the window, get a very rough idea where we were going. I could not see very much even so, as I was nearly blinded by the smoke and then come back in and try and get the plane out of a dive it had got into.

____________________

Digressing once more… From World War Photos, here’s a great in-flight view of Hudson Mk. I VX * C P5120 of No. 206 Squadron RAF.

____________________

A third digression!… From British Pathé movie channel, this video – appropriately titled “Hudson Bombers (1940)” – coincidentally shows aircraft of No. 206 Squadron, identifiable as such because of the squadron code “VX” visible on an aircraft at 5:08, probably at Bircham Newton. Close-up views of the bulbous Boulton Paul Type C turret and aircraft interior clearly reveal the conditions in which Hudson crews “went to work”.

____________________

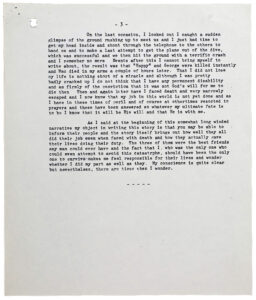

On the last occasion, I looked out I caught a sudden glimpse of the ground rushing up to meet us and I just had time to get my head inside and shout through the telephone to the others to hang on and to make a last attempt to get the plane out of the dive, which was successful and we then hit the ground with a terrific crash and I remember no more. Events after this I cannot bring myself to write about, the result was that “Happy” and George were killed instantly and Mac died in my arms a couple of hours later. That I did not lose my life is nothing short of a miracle and although I was pretty badly cracked up I do not think that I have any permanent disability and am firmly of the conviction that it was not God’s will for me to die then. Then and again later have I faced death and very narrowly escaped and I now know that my job in this world is not yet done and as I have in these times of peril and of course at other times resorted to prayers and these have been answered so whatever my ultimate fate is to be I know that it will be His will and that He is with me.

As I said at the beginning of this somewhat long winded narrative my object in writing this story is that you may be able to inform their people and the story itself brings out how well they all did their job even when faced with death and how they actually gave their lives doing their duty. The three of them were the best friends any man could ever have and the fact that I who was the only one who could even attempt to avoid this catastrophe, should have been the only one to survive makes me feel responsible for their lives and wonder whether I did my part as well as they. My conscience is quite clear but nevertheless, there are times when I wonder.

This is the transcript of F/O White’s story as found within in F/Sgt. Margolis’ Casualty File. Note the handwritten notation at the bottom of the first page: “Original sent to next-of-kin per S/L Westman [sic].” So, the original document remained in possession of F/O White’s widow.

____________________

Though I don’t have the Squadron Records or Squadron Summaries for No. 62 Squadron, it’s obvious from F/O White’s words that Hudson IV “T” AE523 was shot down by Japanese fighters. He doesn’t specify the type of Japanese aircraft involved, but I think, given the location and time-frame (Burma; late 1942) the enemy planes would have been Nakajima Ki.43 Hayabusa (“Peregrine Falcon”; Allied reporting name “Oscar”) aircraft, of the 1st, 11th, 50th, 64th, 77th … or … 204th Burma-based Sentais. For purposes of illustration, this image, from Richard M. Bueschel’s Nakajima Ki.43 Hayabusa I-III in Japanese Army Air Force * RTAF * CAF * IPSF Service shows the camouflage schemes worn by such aircraft in Burma and Thailand from 1941 through 1944.

___________________

Since we’re talking about military units, here’s the emblem of No. 62 Squadron RAF, from RAF Vector Badges…

“INSPERATO” (“UNEXPECTED”)

___________________

And then what happened?

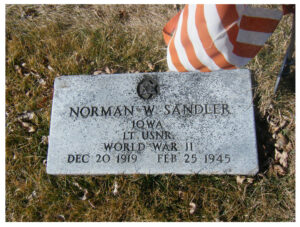

By late 1947, the Research and Enquiry Service (of the Royal Canadian Air Force? – Royal Air Force?) had located the wreckage of Hudson AE523. The aircraft had crashed in hills on the opposite bank of the Kaladan River, near Tatmaw village, which by direction is northeast of Sittwe. However, the burial place of P/O Maughan, F/Sgt. Margolis, and Sgt. McNeil could not be located and remains unknown. This information was conveyed to Tillie Margolis, and I assume the families of Maughan and McNeil, in a letter dated December 10, close to six years after the crew’s last mission. Here it is:

R60404 (RO)

OTTAWA, Canada, December 10th, 1947.

Mrs. Tillie Margolis

604 Centre St.,

Calgary, Alta.

Dear Mrs. Margolis:

It is with regret that I must renew your grief by again referring to your son, Warrant Officer Class II Albert Abraham Margolis, but you will wish to know of a communication which was received from our missing Research and Enquiry Service.

The report states that the wreckage of your son’s aircraft was located near the snail village of Tatmaw, a few miles northeast of Akyab, Burma. The exact location of the crash as given on the report is 20° 13′ north, 93° 01′ east. Although the villagers believed that three of the crew had been buried, an intensive search failed to reveal any graves.

Pilot Officer White, who survived the crash only to lose his life later whilst a prisoner-of-war in Japanese hands, is buried in the British Military Cemetery at Rangoon.

Permanent commemoration to the memory of all the gallant airmen who lost their lives in our fight for freedom will be carried out as soon as details are complete and conditions permit. Unhappily, the task of preparing and erecting permanent memorials to our Fallen is a very great one and it will be some time before all of the work can be completed, but notification of your son’s permanent commemoration will be sent to you when the information becomes available.

I realise that this is an extremely distressing letter, and that it is quite impossible to convey this information to you in any manner which will not add to the heartaches of you and the members of your family, and I am keenly aware that nothing I may say will lessen your great sorrow, but I would like to express my deepest sympathy in the irreparable loss of your gallant son.

Yours sincerely,

R.C.A.F. Casualty Officer

for Chief of the Air Staff

FFF: JIF

____________________

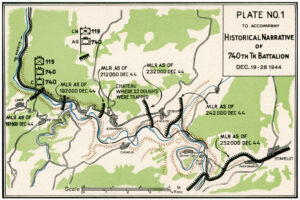

This succession of a single (Apple) map and a few air photos, at larger and larger scales as you move “down” this post, shows what I believe is the approximate location of the crash of Hudson AE523.

First, the map below shows Sittwe (Akyab), at the confluence of the Kaladan, Mayu, and Lay Mro rivers. The Hudson’s crash location is designated by the red circle, which is centered upon latitude and longitude coordinates given in the letter of 10 December 1947. Given that coordinates are listed with figures for “degrees” and “minutes” but not “seconds”, one can conclude that the aircraft came to earth within an area no more precise than the length of the lowest unit of measurement: a minute. At the latitude and longitude specified in the letter, a minute of latitude is about 1.85 km, while a minute of latitude is about 1.75 km. (This is based on the “Length Of A Degree Of Latitude And Longitude Calculator” at CGSNetwork.com.) Given this level of uncertainty, if the center of the Hudson’s crash location is taken as 20° 13′ north, 93° 01′ east, then the aircraft came to earth somewhere – somewhere – within an area of 3.22 square kilometers around this point.

This air photo – at the scale as the above image – reveals that the bomber crashed within hilly terrain, rather than the flat terrain of the flood plain.

Even closer. The range of hills is very prominent at this scale. Tatmaw village lies within the western edge of the circle.

Here’s a much closer view. Tatmaw village immediately stands out as the array of five rows of evenly-spaced buildings (individual homes?), adjacent to cultivated land on the left. Most of the area where AE523 crashed is obviously hilly and uninhabited terrain to the east of the village.

The position of 20° 13′ north 93° 01′ east lies at the center of this image. The rugged nature of this terrain is suggested by the presence of only two man-made structures, which are in the middle of the image. Otherwise, ridges and stream channels are prominent across the landscape.

____________________

Here are additional map and aerial photo views of contemporary Sittwe (Akyab), at successively smaller scales, as you move “down” this post.

This map reveals that the city is serviced by an airport with a single runway, though I don’t know if, in 1942, any airfield even existed in the area in the first place. Wharfs have unsurprisingly expanded since 1944, and extensive residential development has occurred to the west.

This air photo view, at the same scale as the above map, gives a clearer impression of the extent of the city’s growth.

Zooming out reveals the city’s setting within the Bay of Bengal…

…while this map shows the rather sparse interior of Myanmar (Burma) to the east. (Well, at least at this map scale!)

____________________

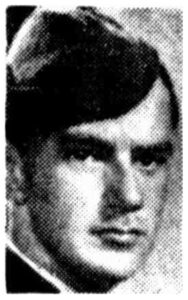

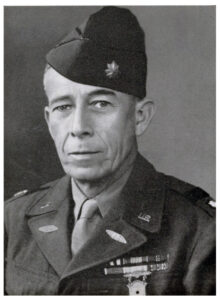

This portrait of Flying Officer Kenneth McKellar White, at his FindAGrave biographical profile, is via researcher Digger.

As revealed in the letters of August, 1945, and December, 1947, F/O White survived the crash of AE523 and the loss of his crew, only to die a little over one year later, when the Rangoon POW camp was struck by bombs dropped by 10th Air Force B-24s during a raid against the Botataung docks at Rangoon. From a variety of internet sources, it’s revealed that White and seven other POWs (three Americans and four British) took shelter in a slit-trench which collapsed upon them, probably from the concussion of bombs which struck in or near the camp.

The seven other men were:

Americans

10th Air Force, 7th Bomb Group, 88th Bomb Squadron

Captured June 4, 1942

Aircraft: B-17E; Pilot: Capt. Frank D. Sharp; eight men in crew.

One crewman (Pvt. Francis J. Teehan) was killed aboard the aircraft. Five were captured, of whom (see below) three killed while POWs. Two others survived captivity, while the pilot and co-pilot evaded capture and returned to duty.

Cummings, Harold Benjamin, Sgt., 6970825

Gonsalves, Elias E., Sgt., 6570123

Malok (“Malock”), Albert L., S/Sgt. 6942456

British

No. 99 Squadron

Manser, William Albert James, Sgt., 915429, RAFVR

Captured Feb. 12, 1943, Wellington IC HD975; Six men in crew

Pilot F/O Richard E. Watson and four other crew members survived as POWs

No. 139 Squadron

Flower, Albert, Sgt., 919720, RAFVR

Jackson, Gordon Henry, W/O, 1284578, RAFVR

Captured April 18, 1942, Hudson III V9221; Four men in crew

One crew member (Sgt. John R. Frehner) killed in aircraft; one other (Sgt. Percy W.G. Hall) survived as a POW

Gloucester Commando

Martin, Alexander George, Pvt., 5182332

Captured in India, May 17, 1942

F/O White, Sergeants Manser and Flower, W/O Jackson, and Pvt. Martin are buried at Collective Grave 6,E,1-6 at the Rangoon War Cemetery in Myanmar. Though Flying Officer White’s Attestation Papers and Casualty file (at the National Archives of Australia) have not been scanned as of this post – June, 2023 – the CWGC reveals that his wife was Liliane Yvonne White, of Lindfield, New South Wales, and his parents, Stanley McKellar White and Florence Amy White, information which can also be found at his biographical profile at FindAGrave.

What’s also revealed at FindAGrave is that F/O White’s brother (and only sibling?) Captain Captain Stanley Boyd McKellar White, NX70920, also lost his life in the Second World War, but under circumstances – it they can so be described – horrifically worse than those of his younger brother. Captured on February 2, 1942 during the fall of Ambon, it was only discovered after the war’s end that he was among some 300 Australian and Dutch POWs who were executed (murdered) within that same month during what became known as the Laha Massacre. His grave is listed as plot 23,D,4 at the Ambon War Cemetery, in Indonesia. He was twenty-six years old.

His portrait below, via Peter Holm, can be found at his FindAGrave biographical profile.

Captain Stanley White was a physician before the war, having attained his medical degree at Sydney University. His biography can be found at Tasmanian War Casualties, which features this photograph – probably from May of 1940 – of the Captain with his (then) new wife, Christine (Dickey) White, at an immeasurably happier time.

____________________

Eighty-one years have transpired since the loss of Hudson AE523.

Though the precise location of the aircraft’s crash site is unknown, assuming any wreckage still exists (if so, probably by now limited to corroded remnants of engines and landing gear) and hasn’t been removed by the inhabitants of Tatmaw village for salvage or household use, these small fragments of the plane can probably only be located by consulting native lore (is there any?), or, through a helicopter-borne aerial magnetometer survey.

But, the point is moot. There is no incentive for this, and it will not happen.

Much more importantly, as for the burial location of Flying Sergeant Margolis, Pilot Officer Maughan, and Sergeant McNeil … taking into account the remote location of the crash; given the area’s subtropical to tropical geography and vegetation; in light of the Japanese attitude towards Allied military casualties; considering the probable absence, loss, or destruction of Japanese records about the crash (assuming records were even kept to begin with) … that, too, will probably never be known among men.

Time has moved on, and the men, or to be more specific, the memories of these men, and even those who knew and remembered them personally, have passed into history.

But, is the point moot?

I find it remarkable that Flight Officer White made the attempt at leaving a written record about his final mission; let alone that the record was preserved; let alone that the record survived to be returned to his wife, and in the course of time, made publicly available. But, there does seem to have been more to the original document: The typed transcript as found in F/Sgt. Margolis’ Casualty File very strongly suggests that this text was only part of a much lengthier document that may have only been intended for F/O White’s wife or family. Specifically note the statement, “The first thing I wish to write about is quite apart from the rest of this letter…” Thus, due to its private nature, the entire document never became incorporated into RAF or RCAF records, Casualty Files for F/Sgt. Margolis, P/O Maughan, and Sgt. McNeil, or eventually the “public record”.

Unfortunately, information about specifically how his account was created and preserved – in terms of writing materials, ink, the mechanics of how and where within the Rangoon POW camp the letter was hidden and concealed, and under whose auspices the document was preserved until the war’s end – is unknown.

In practical terms, the most impressive fact about the letter’s creation is simply the extraordinary risk F/O White was taking in the eventuality (which never came to pass) that the letter would be discovered by the Japanese. Though I’m unable to cite references corroborating this supposition, it’s my anecdotal understanding that the discovery by the Japanese of written information recorded by a POW, even about the most innocuous, mundane, entirely “un”-military topic, would eventuate in extraordinarily severe punishment. (Being euphemistic, there…) Considering the level of intelligence and sensitivity displayed in the letter, certainly F/O White was perceptive and realistic enough to appreciate the risk he was taking by making a written record of his experiences.

Finally, one cannot help but wonder if he had an intuition – whether from rational calculation, intuition, or otherwise – that he would not survive the war. Regardless, it is clear that for F/O White, remembering the past was of greater priority than the safety of the present.

Perhaps the point was not moot, after all. The past was remembered.

____________________

____________________

Sittwe today: Here’s a video from Oung Oo’s YouTube channel (“Oung Oo – Photography – Cinematography“), entitled ““Sittwe 4K, Rakhine, Myanmar” – August 10, 2020“.

Another contemporary view of Sittwe: From the “In Locum Mundo” YouTube channel, this video is entitled ““Sittwe, Myanmar” – April 16, 2019“.

Some Books

Abella, Irving, and Troper, Harold, None Is Too Many – Canada and the Jews of Europe 1933-1948, Random House, New York, N.Y., 1983

Bueschel, Richard M., Nakajima Ki.43 Hayabusa I-III in Japanese Army Air Force * RTAF * CAF * IPSF Service, Arco Publishing Company, Inc., New York, N.Y., 1970

Canadian Jews in World War II – Part II: Casualties, Canadian Jewish Congress, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, 1948

Some Websites

Canadian Jews in World War II

… Bill Gladstone Genealogy (“Canadian Jews in World War II, Part II — Casualties”)

… Ellen Bessner (“Double Threat: Canadian Jews, the Military, and World War II”)

The Crew

F/Sgt. Albert Abraham Margolis

Sgt. Kenneth McKellar “Ken” White

Lockheed Hudson

… Grubby Fingers Shop (“Lockheed Hudson Walkaround Gallery”)