In late April of 1998, Face of a Hero became an object of literary attention as a result of an inquiry to the London Times by Lewis Pollock, concerning the provenance of Catch-22, Pollock correctly noting parallels between the main protagonist, secondary characters, setting, plot, and events of both novels. His letter became the impetus for articles in the Washington Post and New York Times which, accompanied by comments by Joseph Heller himself, delineated these similarities in detail, yet highlighted the marked difference between the two novels in terms of style, structure, and especially – if I can use the word in a literary sense? – the books’ very ethos.

As discussed by Michael Mewshaw and Mel Gussow, there was a genuine commonality of historical and life experience between Falstein and Heller. However, regardless of one’s opinion of the two works as literature, I believe that Joseph Heller was entirely honest in his description of the influences upon and originality of his novel, specifically mentioning being influenced by Louis-Ferdinand Céline (Ironically, “…His bigotry is not incidental to his writing but explicit within it…” an unrepentant Jew-hater. So I ask: Was Joseph Heller aware of this?; So, I also ask: If he had known, would it have mattered?), Evelyn Waugh and Vladimir Nabokov. Even if he had read Face of a Hero in the early 1950s; even if that novel was a spark for the eventual creation of Catch-22, any such spark would only have been as incipient as it was tiny, given what emerged from Heller’s desk eleven years later. In the end, all the parallels between the two novels are far more superficial than structural, just as were the parallels in the lives of their two authors. Though there were parallels in the worlds of Falstein, I believe looked upon “the world” – the world of history; the world of fiction – through vastly different understandings, and thus emerged with literary visions perhaps irreconcilable.

Ten months after the appearance of Mewshaw and Gussow’s articles, The Forward published an essay by Dr. Sanford Pinsker, Professor of English at Franklin and Marshall College, delving into the similarities and differences between the two novels in an effort to establish why Face of a Hero, “…quickly slid down the memory hole.”, in light of the novel’s, “…reissue in paperback by the Steerforth Press.”

One reason attributed to the novel’s reemergence was the late twentieth-century (retrospectively ephemeral) upsurge of interest in the Second World War, through history, fiction, and cinema. In this context, Pinsker cited Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan, Terrence Malik’s The Thin Red Line, and Roberto Benigni’s “bold experiment” Life Is Beautiful (“bold experiment”? – seriously?! – my God, the mind boggles), the latter dubbed by David Denby in his New Yorker film review “Roberto Benigni’s Holocaust Fantasy” as, “…a benign form of Holocaust Denial”.

The other, primary reason, was the above-mentioned controversy generated by Louis Pollock’s letter to the London Times.

More importantly, in his discussion of why Face of a Hero rapidly fell from public and literary consciousness, Pinsker focuses on the novels’ differing approaches to storytelling in the context of the history of the Second World War, and, the experience of Jewish servicemen within that conflict. At heart, Face of a Hero is directly descriptive while Catch-22 is, …built on the scaffolding of the paradoxical,” and thus, far more stylistically vivid, focusing on the absurdities of war and the military, particularly with resonance to the (ahhhh, let’s have a drum roll for the mantra-like incantation of the 60s generation) “war in Vietnam”. While Pinsker appreciated Sergeant Ben Isaacs’ (Louis Falstein’s) empathy with the Jews of Europe, he felt that the direct and explicit treatment of this subject – in terms of dialogue and interior monologue – was an overdone form of “telling”, rather than “showing”, the emphasis upon which left vacant a fuller, deeper treatment of the airman’s experience of war. This is the same point of critique – and yes, it could be argued, a valid one – as mentioned by William DuBois in his New York Times’ “Books of the Times” review of August 17, 1950. “…he has chosen to wander too far from his air-strip. At times (when Ben is sympathizing with refugees in an Italian concentration camp, or cursing discrimination within his own army) one feels that the author is trying to write two novels at once, and muddling his effects. Finally, it’s plain too bad that “Face of a Hero” is bound to suffer from the law of diminishing returns – which operates in the literary market-place even more predictably than in other markets. There have been few war novels that were more deeply felt than this. There have been many that were better planned, many that identified the reader more closely with both cast and background.”

Well, I did not (do not) agree with Pinsker, but I did want to present his viewpoint, especially in light of my own thoughts about Falstein’s novel, some of which were presented in a letter published in The Forward three weeks later. Further insight into Pinsker’s thought about Joseph Heller can be found in his 1991 (republished in 2009) study, Understanding Joseph Heller.

Basically, I suggested that the tenor of the 1950s – the Second World War having ended a half-decade before, the Korean War having just begun, the (first) Cold War in full swing, plus the simple wheel of chance that governs the material success of all literary works, were the principle influences that decided the fate of Face of a Hero. In light of the book’s many positive reviews, “telling” and “aesthetic shaping” had absolutely nothing to do with it.

____________________

Joseph Heller died on December 12, 1999, and more than nominal obituaries was the subject of retrospectives about his literary career and life, two of which follow below. One article is by Peter Carlson (in the Washington Post) and the other (in The Jerusalem Post), is by Michael Mewshaw, who wrote about the Catch-22 / Face of a Hero controversy in mid-1998.

The common element of the reviews, as hinted at by Pinsker in his “war in Vietnam” comment, is the realization that a significant reason for Catch-22’s success was a matter of timing: As related to Carlson by Heller, “At a reading the previous night, a man stood up and publicly thanked Heller for “Calch-22.” “I read your book the day before I got called up for Vietnam,” he said, “and I have to tell you, it helped.” And, as noted by Mewshaw, “…Heller’s book generated popularity and sales by word-of-mouth, eventually tapped into the anti-Vietnam war Zeitgeist of the ‘60s, and now occupies a secure place in the contemporary canon.” It was this, rather than by virtue of its literary quality (or more accurately put, in spite of its literary quality), that it emerged into and has persisted in literary and public consciousness, whether as the book Catch-22, or, the phrase “catch-22”.

So, on to the articles, letters, and retrospectives. These comprise:

April 27, 1998, The Washington Post, Michael Mewshaw, “New Questions Dog ‘Catch-22’ – Joseph Heller Defends Originality of ‘61 Classic”

April 29, 1998, The New York Times, Mel Gussow, “Questioning the Provenance of the Iconic ‘Catch-22’”

February 19, 1999, The Forward, Sanford Pinsker, “Making War Seem Real”

March 5, 1999, The Forward, Michael Moskow, “War Novel Suffered in 1950s”

December 14, 1999, The Washington Post, Peter Carlson, “The Heights of Absurdity – Joseph Heller Drove a World Stark Raving Sane With ‘Catch-22’”

December 31, 1999, The Jerusalem Post, Mike Mewshaw, “Too easy to catch Heller out?”

________________________________________

New Questions Dog ‘Catch-22’

Joseph Heller Defends Originality of ‘61 Classic

Because [Lewis] Pollock must have been one of the few people on the planet who had read both books,

he was especially interested to learn that Heller mentioned in his recent autobiography,

“Now and Then,” that he had occasionally “borrowed” the scenes and settings of his early fiction from other authors.

“I did not intend to cause trouble, Mr. Heller,” Pollock told the London Times.

He just wondered whether Heller might have read and been influenced by “The Sky Is a Lonely Place.”

Or, as he mused in his letter, “is this a remarkable example of synchronicity?”

Michael Mewshaw

The Washington Post

April 27, 1998

The inquiry to the London Sunday Times was politely phrased. “Can anyone out there account for the amazing similarity of characters, personality traits, eccentricities, physical descriptions, personnel injuries and incidents in `Catch-22’ (by Joseph Heller) and a novel by Louis Falstein, `The Sky Is a Lonely Place,’ published in 1951?”

The letter to the editor, published two weeks ago, caused ripples throughout literary London and led to an extensive report in today’s London Times. Could one of the 20th century’s best-selling novels — a book whose title became a synonym for paradox, the very hallmark of absurdity and a masterpiece of contemporary black humor — not have been as “wildly original” and “fantastically unique” as critics hailed it?

A reading of Louis Falstein’s novel suggests that somebody from the same background as Heller (the son of a Russian Jewish family), from the same borough of New York City (Brooklyn), from the same branch of the service (an airman on an American bomber squadron) and from the same combat theater (Italy, 1943-45) did write a book tantalizingly like the one Joseph Heller published more than a decade later.

Reached at his home on Long Island today, Heller denied that he ever read “The Sky Is a Lonely Place,” or heard of Louis Falstein, or of Lewis Pollock, the professional artist and amateur bibliophile who queried the London Times. “The similarities come from a common wartime experience,” he said.

“My book came out in 1961,” he added. “I find it funny that nobody else has noticed any similarities, including Falstein himself, who died just last year.”

Although he concedes some surprise at the bits and pieces the novels have in common, Heller pointed out how much war fiction depends on the same elementary variations on themes and characters.

In his book, Falstein described a hospitalized pilot lying in bed “in a white cast, like an Egyptian mummy. His arms were broken; and where his legs had been, there were cotton swathed stumps. Only his face showed out of the cast, and there were openings at the bottom for bodily functions. An orderly or nurse held the cigarette for him when he smoked.”

Heller wrote, “The soldier in white was encased from head to toe in plaster and gauze. He had two useless arms and two useless legs.” A nurse is described inserting a thermometer into his mouth, and he’s subsequently called “a stuffed and sterilized mummy.”

Toward the end of his novel, Falstein dramatized a grotesque Christmas Eve party that dissolves into a bacchanal of singing, screaming, sobbing and lamenting and ends with an outbreak of gunfire that the soldiers mistake for an enemy attack. “There were several more carbine pings, and somebody answered fire with a forty-five pistol.”

Late in “Catch-22,” Heller wrote that a Thanksgiving “celebration lasted long into the night, and the stillness was fractured often by wild, exultant shouts and by cries of people who were merry or sick. There was the recurring sound of retching and moaning, of laughter, greetings, threats and swearing, and of bottles shattering against rock. There were dirty songs in the distance.” It, too, ends with gunfire, and the protagonist Yossarian charges out of his tent with his .45.

“Catch-22” and “The Sky Is a Lonely Place” share another vaguely similar scene in which an Italian woman, who doesn’t understand English and has kept herself apart from the soldiers, is raped.

Asked today about those and other similarities, Heller cited personal experience. “I don’t know how many airmen brought along extra flak jackets, but I did,” he said. “That Thanksgiving scene actually happened — guys got drunk and started shooting. There was a case of rape in Rome. I heard of it. A maid got thrown out a window. I read about it in the military newspaper.” Which, he said, may mean Falstein read the same story.

As for the patient in a full-body cast, “That goes all the way back to Dalton Trumbo’s `Johnny Got His Gun.’ Trumbo’s novel came out not just before `Catch-22,’ but long before Falstein’s. If there’s a literary reference or allusion I’m a bit embarrassed about, it’s the similarity between the first chapter of `Catch-22’ and Celine’s `Journey to the End of Night.’ “

Because Pollock must have been one of the few people on the planet who had read both books, he was especially interested to learn that Heller mentioned in his recent autobiography, “Now and Then,” that he had occasionally “borrowed” the scenes and settings of his early fiction from other authors. “I did not intend to cause trouble, Mr. Heller,” Pollock told the London Times. He just wondered whether Heller might have read and been influenced by “The Sky Is a Lonely Place.” Or, as he mused in his letter, “is this a remarkable example of synchronicity?”

Duff Hart-Davis, son of Falstein’s late British publisher, says his father never met the author, and has raised the possibility that Falstein and Heller are the same person, that “The Sky Is a Lonely Place” was “a practice run for `Catch-22.’ “

But Heller squelched that theory.

“The Sky Is a Lonely Place” is narrated in the first person by a Jewish gunner in a B-24, Ben “Pop” Isaacs; “Catch-22” has an omniscient narrator who recounts the antics of the crew of a B-25.

Just as Heller’s celebrated novel contains a jamboree of characters — Colonel Cathcart, Colonel Korn, Major Major Major Major, Milo Minderbinder, Captain Aarfy Aardvark and, of course, Yossarian — so does Falstein’s, with Mel Ginn, Cosmo Fidanza, Chester Kowalski, Charles Couch, Billy Poat and Jack Doolie Dula.

While “Catch-22” is much longer, more ambitious and more relentlessly comic, Heller is correct that much of what they have in common comes out of the context of World War II, when airmen were eager to fly their 50 missions and get back to the United States.

When not airborne and on the brink of death, characters in both books kill time in scenes familiar to any reader of war fiction. They paint tiny bombs on their flight jackets to mark each mission. They drink, complain, cry, lie, play cruel jokes, fight, frequent brothels and encounter locals who are depicted as childlike and cunning, full of equal measures of Old World wisdom and venality. Children pimp for their sisters. Nurses are ice cold or volcanically hot. Rain plays havoc with the flight schedule, keeping the men safe on the ground, but exposing them to flu, fever, jaundice, hepatitis and fraying nerves.

Like Falstein, Heller focuses on the underbelly of the campaign — on PR officers more interested in publicity and medals than on men, on black marketeers who skim off supplies, leaving troops hungry and in the lurch.

Where Falstein heightens the tension in a conventional, realistic manner with near-misses, crash landings, midair dogfights and fatal miscalculations of fuel, Heller ratchets up the stakes and darkens the laughter by having the high command constantly raise the required number of missions.

Yet Falstein displays a Hellerean fascination for Grand Guignol violence, quirky gags and virulent humor that verves from the slapstick to the surrealistic and sometimes the satanic. Scabrous jokes, racial epithets, savage sexual ribaldry and hair-raising craziness pour out of people. At times, Falstein achieves a sort of demonic poetry, as when a soldier says “Grazie Nazi,” and his friend replies “Prego, dago” — Heller does the same in “Catch-22,” where an exchange runs: “Pass the salt, Walt / Pass the bread, Fred / Shoot me a beet, Pete.”

Paralyzed with fear, Falstein’s characters become preternaturally alert to the absurdity of their situation, the logical lunacy of rules and regulations, the arbitrariness of authority and the emptiness of words. Early in “The Sky Is a Lonely Place,” the narrator learns a lesson in “airwar language” when he’s instructed “never use the word KILLED . . . we say a guy WENT DOWN” — a scene reminiscent of the chaplain in “Catch-22” being ordered to compose a prayer that eliminates God and death.

In both books, a red ribbon on a map marks the advance of American troops and the bomb line. As the ribbon approaches Vienna, a Falstein character comes down with diarrhea. When in “Catch-22” it closes in on Bologna, an epidemic of diarrhea breaks out on Heller’s air base.

Even as the similarities grow more frequent, it’s possible to see them as shards from the same general mosaic. True, Falstein’s bombardier “shrieks,” just as Yossarian does after he drops a bomb. True, there’s a cat that crawls onto a sleeping soldier and has to be peeled away when the man wakes up. True, both books have characters who shuffle and deal cards in a snappy explosive fashion. True, Ben Isaacs, like Yossarian, drags extra flak jackets along on each mission and drapes them all over his body. True, there are common comic scenes involving the idiocies of letter censors and the self-serving circumlocutions of military doctors who sense that the flyboys are sick and/or insane, yet keep sending them on missions.

But several similarities seem to transcend any question of shared experience or literary archetypes. “Catch-22” opens with a chapter titled “The Texan.” In the first chapter of “The Sky Is a Lonely Place,” the narrator introduces a character referred to as “the stringy young Texan.”

Still, the current imbroglio has not reduced Joseph Heller’s pride of authorship and he closes by stressing, “Given the amount of invention in `Catch-22,’ it would be an amazing coincidence if there were fundamental similarities with Falstein’s novel.”

________________________________________

Questioning the Provenance of the Iconic ‘Catch-22’

‘‘Face of a Hero,’’ told in the first person by a gunner named Ben Isaacs,

is a harrowing but relatively straightforward dramatic account of one man’s wartime experiences.

Isaacs, nicknamed Pops because he is older than the other members of the crew,

is obsessed by his hatred of Hitler and Fascism.

‘‘Catch-22’’ is a Dantesque vision, a darkly comic surrealistic portrait of men caught up in the madness of war.

Mr. Heller’s protagonist, Yossarian, is a bombardier who comes to believe –

with some justification –

that everyone is trying to kill him.

With an increasing desperation, he wants to complete his 50 missions so he can go home,

but keeps finding the number of missions needed raised by his commanding officer.

Mel Gussow

The New York Times

April 29, 1998

When Louis Falstein’s ‘‘Face of a Hero’’ was published in 1950, Herbert F. West reviewed it favorably in The New York Times Book Review, calling it ‘‘the most mature novel about the Air Force that has yet appeared. . . . a book that is both exciting and important.’’ Still, the book and its author faded into obscurity.

When Joseph Heller’s ‘‘Catch-22’’ was published 11 years later, Richard G. Stern gave it a negative review in the Times Book Review. He said that it ‘‘gasps for want of craft and sensibility’’ and called it ‘‘an emotional hodgepodge.’’ Despite that indictment, ‘‘Catch-22’’ eventually became a phenomenal success — a best seller, a film and the cornerstone of a major literary career.

Now, in a strange twist, the two books have come together, and their meeting has led to a provocative debate. In a recent letter to The Times of London, Lewis Pollock, a London bibliophile, wondered if anyone could ‘‘account for the amazing similarity of characters, personality traits, eccentricities, physical descriptions, personnel injuries and incidents’’ in the two books.

He asked if this were ‘‘a remarkable example of synchronicity.’’ That letter has sparked conjecture in both Britain and the United States about the origins of ‘‘Catch-22.’’ An article appeared this week in The Sunday Times of London, followed by one the next day on the front page of The Washington Post suggesting that Mr. Heller may have appropriated material from Falstein’s book.

On the telephone from his home on Long Island, Mr. Heller issued a categorical denial. He said he was influenced in his writing by Celine, Waugh and Nabokov, but not by Falstein. ‘‘I never read the book,’’ he said. ‘‘I never heard of the book or the author. To the extent that there are similarities, they are coincidences, and if the similarities are striking then they are striking coincidences.’’

He added, ‘‘If I went through the ‘Iliad’ I would probably find as many similarities to ‘Catch-22’ as other people seem to be finding between Falstein’s book and mine.’’

Robert Gottlieb, who edited ‘‘Catch-22’’ for Simon & Schuster, was astonished at the suggestion that Mr. Heller might have borrowed anything from Falstein or any other writer. ‘‘I’ve never seen, heard or felt Joe Heller doing anything remotely less than honest during our 40-year relationship,’’ he said. ‘‘It is inconceivable that he used any other writer’s work. For one thing, he’s too shrewd to do something so blatant. It’s easier for me to believe that Falstein anticipated ‘Catch-22.’ ‘‘

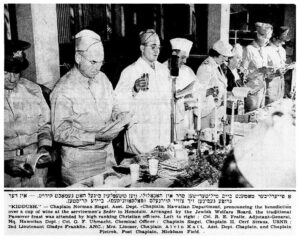

Both authors were in the Army Air Force in Europe during World War II as members of combat crews on bombers. Falstein was stationed in southern Italy, Mr. Heller in Corsica (called Pianosa in his book). For each, this was a first novel. Mr. Falstein died in 1995 at 86.

While it was easy enough for Mr. Heller to be unaware of Mr. Falstein’s book, it is implausible that Falstein was unaware of ‘‘Catch-22,’’ a highly celebrated book that dealt with a closely related subject. ‘‘Where was Mr. Falstein between 1961 and his death?’’ asked Mr. Gottlieb. ‘‘If he felt his book was misused, he should have said something about it.’’ Falstein’s son, Joshua, who is a court stenographer, said this week that his father never mentioned ‘‘Catch-22’’ to him.

From a reading of ‘‘Face of a Hero’’ (published by Harcourt Brace and long out of print), it is clear that each novel stands on its own. Despite the common background in the military and some similar incidents, the books are widely disparate in approach, ambition, style and content.

‘‘Face of a Hero,’’ told in the first person by a gunner named Ben Isaacs, is a harrowing but relatively straightforward dramatic account of one man’s wartime experiences. Isaacs, nicknamed Pops because he is older than the other members of the crew, is obsessed by his hatred of Hitler and Fascism.

‘‘Catch-22’’ is a Dantesque vision, a darkly comic surrealistic portrait of men caught up in the madness of war. Mr. Heller’s protagonist, Yossarian, is a bombardier who comes to believe — with some justification — that everyone is trying to kill him. With an increasing desperation, he wants to complete his 50 missions so he can go home, but keeps finding the number of missions needed raised by his commanding officer.

An examination of the two books leads this reader to conclude that the similarities between the two can easily be attributed to the shared wartime experiences of the authors. In his first chapter, for instance, Falstein introduces his flight crew, one of whom is identified as ‘‘the stringy young Texan.’’ Coincidentally, Mr. Heller’s first chapter is called ‘‘The Texan’’ and one of the characters is from Texas, but the scene is entirely different. Yossarian is in a hospital. ‘‘It was love at first sight,’’ Mr. Heller begins. ‘‘The first time Yossarian saw the chaplain he fell madly in love with him.’’

In that chapter, Mr. Heller introduces ‘‘the soldier in white’’ who ‘‘was encased from head to toe in plaster and gauze.’’ He continues, ‘‘He had two useless legs and two useless arms’’ and had been smuggled into the ward at night. Later in his book, Falstein also has a soldier in white who ‘‘looked entombed in the cast, like an Egyptian mummy.’’ This invalid is the crew’s new pilot, wounded in action. In ‘‘Catch-22,’’ the figure is as mysterious and as metaphorical as the Unknown Soldier.

In Falstein’s book there is an animal lover who sleeps with five cats. In Mr. Heller’s book, there is Hungry Joe, who ‘‘dreamed that Huple’s cat was sleeping on his face, suffocating him, and when he woke up, Huple’s cat was sleeping on his face.’’ Both Isaacs and Yossarian take extra flak jackets into combat as protection — as apparently did Falstein, Mr. Heller and other members of flight crews in combat. In each book, there is a holiday party that ends in gunfire and there is a rape scene with some similarity.

While ‘‘Face of a Hero’’ holds firmly to a realistic base, ‘‘Catch-22’’ is a transforming act of the imagination, populated by fiercely original characters like Milo Minderbinder, the flamboyant opportunist who bombs his own air base for profit (Falstein has a black marketeer in his company, far smaller in scope than Milo). From Mr. Heller, there is also Major Major Major Major, whose fate is to look like Henry Fonda but not act anything like him. Then there is Doc Daneeka with his theory of ‘‘Catch-22.’’ A man has to be declared crazy to be relieved from combat duty, but ‘‘anyone who wants to get out of combat duty isn’t really crazy.’’

Falstein, who was born in Ukraine and came to the United States in 1925, wrote several other novels, including ‘‘Slaughter Street’’ and ‘‘Sole Survivor,’’ as well as a biography of Sholom Aleichem for young readers. After the war, he attended New York University and later taught there and at City College. He continued to write late in life but his work was not published, his son said.

In his recent memoir, ‘‘Now and Then,’’ Mr. Heller discusses in detail the models for some of his characters. Reviewing the book in The Times of London, J. G. Ballard reflected on the importance of ‘‘Catch-22,’’ calling it ‘‘the last great novel written in English.’’ Paradoxically, it was Mr. Ballard’s piece that led to that questioning letter to the editor and the subsequent controversy.

________________________________________

Making War Seem Real

At the same time, however, a part of me knows

that there is far too much telling rather than showing in Falstein’s novel.

By fastening his imagination to the “facts” of what being a Jewish airman was really like,

he neglects telling details and aesthetic shaping.

As such his novel, admirable though it is in spots,

fails to make a convincing case for the direction in which “Face of a Hero” merely points.

My hunch is that the literary jury has long ago rendered its verdict,

and that nothing in “Face of a Hero” is likely to change it.

Sanford Pinsker

The Forward

February 19, 1999

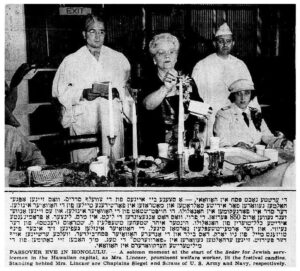

Louis Falstein’s autobiographical World War II novel, “Face of a Hero,” was published in 1950. Despite some good notices in The New York Times and The New Republic, it quickly slid down the memory hole. What, then, accounts for its reissue in paperback by the Steerforth Press? Two answers suggest themselves.

Louis Falstein’s autobiographical World War II novel, “Face of a Hero,” was published in 1950. Despite some good notices in The New York Times and The New Republic, it quickly slid down the memory hole. What, then, accounts for its reissue in paperback by the Steerforth Press? Two answers suggest themselves.

One has to do with speculation about the similarities between Falstein’s account of the war and Joseph Heller’s comic masterpiece, “Catch-22,” which was published 10 years after “Face of a Hero” and covered roughly the same material. The airmen at the center of both novels share their worries about survival in the face of enemy flak and the number of missions they are required to fly, and they watch their fellow squadron members’ increasingly desperate quests for comic or sexual relief as the shadow of death creeps closer. Although the case for Mr. Heller’s unacknowledged appropriation of Falstein’s material seems to have little if any merit, once certain questions have been raised, reprinting a novel such as “Face of a Hero” will follow as the night follows the day. Sadly, Falstein, who died in 1995, is not available for comment or questioning.

The other reason for the reappearance of the book is a renewed interest in seeing World War II through a realistic lens. Steven Spielberg’s “Saving Private Ryan” and Terrence Malick’s “The Thin Red Line,” are part of this trend. Admirers of “Saving Private Ryan” insist that the film is Hollywood storytelling at its best; by capturing essential truths in striking images and a straightforward narrative, it does for World War II cinema, they say, what “Schindler’s List” had done for the Holocaust.

The difference between “Saving Private Ryan,” “The Thin Red Line” and “Face of a Hero” on one hand and “Catch-22” on the other are part of a larger, ongoing debate about hyper-realism and the more inventive – some would say, wackier – possibilities of postmodernist experimentation. A recent example of the latter is Italian comedian Roberto Benigni’s bold experiment, “Life Is Beautiful,” which uses farce to illustrate the horrors of concentration camps. Mr. Benigni’s film is squaring off against “Saving Private Ryan” and “The Thin Red Line” for the Academy Award for Best Picture, and the choice among them is in part a referendum on the relative merits of grim realism and absurd humor.

Which method gets us closer to the truth – the rigorous attention in “Face of a Hero” to the details as they really were, or the dark comedy of “Catch-22,” a book that turns the horrors of war into a funhouse mirror? Mr. Heller’s novel is built on the scaffolding of the paradoxical Catch-22: “If he flew them he was crazy and didn’t have to; but if he didn’t want to he was sane and had to.” The dark joke at the heart of Mr. Heller’s carpet allows him to raise arbitrarily the number of required missions (by contrast, in Falstein’s treatment, the number never inches higher than 50), or to etch a slapstick world in which language can do more damage than enemy fire. The result is that when the two novels are read side by side, Mr. Heller is not only the more vivid stylist by far, but he also has a deeper, more penetrating grasp of war’s central absurdities. Surrealism, in short, seems a better cultural fit, especially when readers apply Mr. Heller’s deadly logic to the war in Vietnam.

“Catch-22” may contain multitudes, but one figure conspicuously missing is the Jew. John Yossarian, Mr. Heller’s protagonist and wisecracking mouthpiece, prides himself on being an Assyrian, even more foreign and estranged than was Falstein’s literary alter ego, 34-year-old Ben Isaacs. Those of us who have long hectored Mr. Heller about erasing his Jewishness from his war novel will find “Face of a Hero” something of a mixed – and troubling – bag. On one hand, there are passages in which Ben Isaacs not only makes his Jewish identification clear, but also links it to a wider sense of history:

I was here because I hated Hitler, hated fascism, and feared they would come to America. I was here because Hitler made me conscious, again, that as a Jew I must assume the role of scapegoat. I had almost forgotten that being Jewish carried any stigma with it, though I had known anti-Semitism and pogroms as a child [in the Ukraine]. From the age of fifteen when I arrived in America, being Jewish had not stood in the way of my becoming a teacher, of being happily married, of leading the kind of existence that would let me attain my limited aspirations. Only in 1933, with Hitler riding into power, was the old wound reopened.

On the other hand, in novels such as “Face of a Hero” and perhaps even more so in films, the wartime squadron becomes a microcosm of America itself, with its requisite Texas blowhard, apple-cheeked farm boy from Iowa, lone black, and secular Brooklyn Jew. In this sense, “Saving Private Ryan” is so many musty cinematic conventions poured into a visually shocking new treatment – including its Jewish character, who dies as a result of a fellow’s soldier’s paralyzing cowardice in the face of the German army. For better or worse, Mr. Heller’s novel changed the formula, and in the process lifted realism to a new surrealistic level, one where any whiff of the Holocaust had to be consciously edited out. By contrast, Falstein’s Ben Isaacs drags the nights of fog and death onto center stage.

Small wonder, then, that a part of me wants to give Falstein the credit that is his due, not as the unacknowledged model for “Catch22” but rather as a novelistic exploration of its author’s identity that includes passages such as this one: “My guns had spoken for the pogroms I had lived through … for the anguished screams of people, my people, who were this very moment burning in Hitler’s extermination ovens.”

At the same time, however, a part of me knows that there is far too much telling rather than showing in Falstein’s novel. By fastening his imagination to the “facts” of what being a Jewish airman was really like, he neglects telling details and aesthetic shaping. As such his novel, admirable though it is in spots, fails to make a convincing case for the direction in which “Face of a Hero” merely points. My hunch is that the literary jury has long ago rendered its verdict, and that nothing in “Face of a Hero” is likely to change it.

Mr: Pinsker is Shadek professor of humanities at Franklin and Marshall College.

________________________________________

War Novel Suffered in 1950s

Here’s a letter I wrote to The Forward, in response to Pinsker’s essay:

The novel’s lack of success may have had far more to do with the tenor of the 50s than its quality as literature.

*****

Falstein may have felt no desire to engage in experiments in form and style.

Rather, he simply wanted to tell a story…

no more, no less…

about the experiences of a Jewish aerial gunner and his fellow crewmen,

during a time when the 15th Air Force was incurring its heaviest losses of planes and crews.

What Pinsker sees “a lack of aesthetic shaping” is actually simplicity, clarity, and above all, honesty.

The Forward

March 5, 1999

I was happily surprised’ to see The Forward accord Louis Falstein’s “Face of a Hero”‘ attention the novel has long merited (“Making War Seem Real,” February 29). Sadly, though, Sanford Pinsker’s review and comparison of Mr. Falstein’s novel to Joseph Heller’s “Catch 22” does the former a great injustice. It is an injustice in terms of the clarity of Falstein’s depiction of the experiences and thoughts of a Jewish aviator flying missions over German-occupied Europe, the literary style of “Face of a Hero” and the book’s place in the literature of World War II.

I was happily surprised’ to see The Forward accord Louis Falstein’s “Face of a Hero”‘ attention the novel has long merited (“Making War Seem Real,” February 29). Sadly, though, Sanford Pinsker’s review and comparison of Mr. Falstein’s novel to Joseph Heller’s “Catch 22” does the former a great injustice. It is an injustice in terms of the clarity of Falstein’s depiction of the experiences and thoughts of a Jewish aviator flying missions over German-occupied Europe, the literary style of “Face of a Hero” and the book’s place in the literature of World War II.

Mr. Pinsker seems to categorize Falstein’s depiction of a multi-ethnic bomber crew as an exarnple of a hackneyed plot device used by writers and filmmakers since World War II. But a serious look at the composition of most World War II Air Corps bomber crews shows that the air crew of Falstein’s fictional B-24 bomber, the “Flying Foxhole,” has more basis in fact than fiction. As discussed in detail by Gerald Astor in “The Mighty Eighth,” American bomber crews often indeed were random and varied combinations of ethnicities and religions. A look at the historical records of any-odd World War II fighter or bomber group will suffice to prove this. As such, these men naturally experiencecI the gamut off feelings found among people from disparate locales and backgrounds, thrown together at random, in situations of life and death.

In more general terms, Mr. Pinsker takes issue with the way “Face of a Hero” spends too much time “telling, rather than showing,” being enmeshed in details and facts at the expense of style and aesthetics. This, combined with the novel’s allegedly stereotypical and shallow characters, may have contributed to its rapid disappearance from the literary spotlight.

I think the actual reasons for the novel’s lack of recognition are vastly different.

Remember, the story was published in 1950, only five years after the end of World War II and coincident with the start of the Korean War. The American public was psychologically fatigued from a costly victory only five years earlier, yet it found itself at war again, dashing hopes for an era of peace. The novel depicted the psychological effects of war on soldiers, and on aviators, and it presented these men in what some may see as unflattering, but ultimately sympathetic, candor. Finally, the praise given to the novel by The New York Times and The New Republic was by no means universal. For example, an anonymous reviewer in Time magazine blasted Falstein for emphasizing Ben Isaacs’s Jewish identity and perspective of the war, characterizing the book’s hero as a “congenital soul-searcher” and “neurotic.” The novel’s lack of success may have had far more to do with the tenor of the 1950s than its quality as literature.

Falstein may have felt no desire to engage in experiments, in form and style. Rather, he simply wanted to tell a story – no more, no less – about the experiences of a Jewish aerial gunner and his fellow crewmen, during a time when the 15th Air Force was incurring its heaviest losses of planes and crews. What Mr. Pinsker sees as “a lack of aesthetic shaping” is actually simplicity, clarity and, above all, honesty.

[My letter concluded with the following two sentences, which The Forward did not deign to publish: “If anything, Face of a Hero’s release was premature. The verdict of Pinsker’s “literary jury”, as forgetful as it is fickle, may have been equally premature.”]

________________________________________

The Heights of Absurdity

Joseph Heller Drove a World Stark Raving Sane With ‘Catch-22’

I was supposed to be interviewing Heller about his latest book, “Now and Then,”

a chatty, charming memoir of his boyhood in Coney Island and his adventures as a bombardier in World War II.

But I spent most of the time asking him about “Catch-22,”

which is my favorite novel of all time.

It’s a strange, convoluted, grim, hilarious war novel that seems to suggest that the whole world is completely insane.

This message confirmed suspicions I held when I first read it in 1958,

and it has been corroborated countless times since then.

I told Heller that his crazy book had helped keep me sane.

He smiled.

He heard similar comments nearly every lime he ventured out in public.

At a reading the previous night, a man stood up and publicly thanked Heller for “Calch-22.”

“I read your book the day before I got called up for Vietnam,” he said, “and I have to tell you, it helped.”

Peter Carlson

The Washington Post

December 14, 1999

The first time I saw Joseph Heller, back in the late ‘60s, he was delivering a speech at New York University. That night, he revealed his plans for the future. “I’m going to live forever,” he said, “or die trying.”

On Sunday night, he died trying. A heart attack did what Nazi antiaircraft gunners failed to do back in World War II. The author of “Catch-22” and seven other books was 76.

The first and only time I had lunch with Heller was last year. It was the early days of the Monica Lewinsky scandal, which be was enjoying tremendously.

“I love it,” he said, smiling broadly beneath a fluffy halo of bright while hair. “The fact that it’s so ridiculous is what makes it so exquisitely entertaining to me.”

Heller was a connoisseur of the absurd. The scandal was providing delicious new realms of ludicrousness that not even he could have imagined. A few days earlier, Lewinsky’s soon-to be-fired attorney, William Ginsburg, had complained that his client’s life was ruined, that nobody would ever again want to date her or hire her.

“I wanted to call and say, “I’ll date you! I’ll hire you!” he cackled uproariously. Then he went back to his crab cakes. The man loved to eat.

I was supposed to be interviewing Heller about his latest book, “Now and Then,” a chatty, charming memoir of his boyhood in Coney Island and his adventures as a bombardier in World War II. But I spent most of the time asking him about “Catch-22,” which is my favorite novel of all time. It’s a strange, convoluted, grim, hilarious war novel that seems to suggest that the whole world is completely insane. This message confirmed suspicions I held when I first read it in 1958, and it has been corroborated countless times since then.

I told Heller that his crazy book had helped keep me sane. He smiled. He heard similar comments nearly every lime he ventured out in public. At a reading the previous night, a man stood up and publicly thanked Heller for “Calch-22.” “I read your book the day before I got called up for Vietnam,” he said, “and I have to tell you, it helped.”

A year earlier, in Prague, people kept buttonholing Heller to tell him that bootlegged copies of “Catch-22” had served as an antidote to the absurdities of life under communism.

Translated into nearly every written language, “Catch-22” has sold well over 20 million copies. It still sells briskly wherever human beings feel tormented by crazed bosses and mindless bureaucracies – which is to say, just about everywhere on the planet.

It is ostensibly the story of a U.S. bomb squadron In the Mediterranean during World War II and a bombardier named Yossarian who is driven crazy by the Germans, who keep shooting at him when he drops bombs on them, and by his American superiors, who seem less concerned about winning the war than they are about parades, loyalty oaths and getting promoted.

Yossarian is so crazy that he should be excused from combat but, alas, there’s a catch, Catch-22: You can’t be excused unless you ask to be excused, and anybody who asks to get out of combat is obviously sane and therefore ineligible to be excused.

“That’s some catch, that Catch-22,” Yossarian said.

“It’s the best there is,” said his buddy Doc Daneeka.

They were right. The term entered common language and earned a place in the dictionary. I read Heller the official definition from Webster’s: “a paradox in a law, regulation or practice that makes one a victim of its provisions no matter what one does.”

“That’s a better definition than I could give,” he said, smiling.

“Catch-22” begat several of its own Catch-22s. When it was published in 1961, critics complained that it was plotless, repetitive and incomprehensible. When the rest of his novels appeared, critics complained that he had again failed to write a book as good as “Catch-22.” Heller always had an answer for that “Who has?”

In 1998, a letter printed in the London Sunday Times kicked up a brief literary controversy by suggesting that many of the scenes in “Catch-22” were similar to scenes in an earlier war novel. The Sky Is a Lonely Place,” by Louis Falstein. The insinuation was absurd. It wasn’t the depiction of life in a bomber squadron that made Heller’s novel a classic; it was its grand comic vision of the absurdity of modem life.

Heller said he’d never read Falstein’s novel. “I find it funny,” he added, “that nobody else noticed any similarities, including Falstein himself.”

Heller never spent much time in Washington, but his writing revealed that he understood the culture of the federal city as well as any reporter. In “Closing Time,” his 1994 sequel to “Catch-22,” he captured the life of a hotshot K Street lawyer in the fictitious firm of Atwater, Fitzwater, Dishwater, Brown, Jordan, Quack and Capone: “He served often on governmental commissions to exonerate and as coauthor of reports to vindicate.” That novel also provided the most accurate extant definition of the Freedom of Information Act: “a federal regulation obliging government agencies to release all information they had to anyone who made application for it except information they had that they did not want to release.”

Life had a way of tarring Heller’s most outrageous satire into banal realities. In I979”s “Good as Gold,” he invented a president who spent his first year in office writing a book about his first year in office. This seemed far-fetched until New York Mayor Ed Koch and Minnesota Gov. Jesse Ventura spent their time m office writing books. In “Catch-22,” Milo Minderbinder, the wheeler-dealer supply officer, actually contracts with his enemies to bomb his own squadron. Critics considered this ridiculous until Oliver North, a Marine working for the United States government sold missiles to the same Iranian government that had earlier supported the terrorists who bombed a Marine barracks in Lebanon.

Joe Heller is dead but “Catch-22” will live forever. He would have preferred the opposite, but what can you do? Death is the ultimate Catch-22.

________________________________________

Too easy to catch Heller out?

Initially published in 1961 to mixed reviews,

Catch-22 might well have met the fate of most novels which,

regardless of literary merit, soon go out of print and disappear.

But Heller’s book generated popularity and sales by word-of-mouth,

eventually tapped into the anti-Vietnam war Zeitgeist of the ‘60s,

and now occupies a secure place in the contemporary canon.

It has sold more than 10 million copies in the US and has, from the start,

been popular in the UK where even its satirical anti-establishment tone

didn’t prevent the Financial Times from declaring:

“No one has ever written a book like this.”

As a critical assessment, however, claims concerning Catch-22’s originality have

always smacked of amnesia or ignorance.

And-war novels,

plenty of them coruscatingly funny and witheringly iconoclastic,

have appeared in every language,

and Heller himself has acknowledged his debt to

Evelyn Waugh

Celine’s Journey to the End of the Night

and Dalton Trumbo’s And Johnny Got His Gun.

Mike Mewshaw

The Jerusalem Post

December 31, 1999

Joseph Heller’s death at the age of 76 earlier this month naturally refocused attention on his literary legacy, especially his first novel, Catch-22. Hailed as “wildly original,” “fantastically unique,” and one of the finest works of American fiction this century, Catch-22 quickly became more than a literary title. The phrase entered the modern lexicon as the hallmark of paradox, existential absurdity and black humor. As a comic exploration of logical lunacy on a cosmic scale, the novel presented its protagonist, Yossarian, as an Everyman trapped by a nightmarish “catch” or legal loophole. While officially a World War II airman who went insane could be grounded for medical reasons, anyone who asked to be scratched from bombing missions was automatically considered sane and forced to keep flying.

Joseph Heller’s death at the age of 76 earlier this month naturally refocused attention on his literary legacy, especially his first novel, Catch-22. Hailed as “wildly original,” “fantastically unique,” and one of the finest works of American fiction this century, Catch-22 quickly became more than a literary title. The phrase entered the modern lexicon as the hallmark of paradox, existential absurdity and black humor. As a comic exploration of logical lunacy on a cosmic scale, the novel presented its protagonist, Yossarian, as an Everyman trapped by a nightmarish “catch” or legal loophole. While officially a World War II airman who went insane could be grounded for medical reasons, anyone who asked to be scratched from bombing missions was automatically considered sane and forced to keep flying.

Initially published in 1961 to mixed reviews, Catch-22 might well have met the fate of most novels which, regardless of literary merit, soon go out of print and disappear. But Heller’s book generated popularity and sales by word-of-mouth, eventually tapped into the anti-Vietnam war Zeitgeist of the ‘60s, and now occupies a secure place in the contemporary canon. It has sold more than 10 million copies in the US and has, from the start, been popular in the UK where even its satirical anti-establishment tone didn’t prevent the Financial Times from declaring: “No one has ever written a book like this.” As a critical assessment, however, claims concerning Catch-22’s originality have always smacked of amnesia or ignorance. And-war novels, plenty of them corruscatingly funny and witheringly iconoclastic, have appeared in every language, and Heller himself has acknowledged his debt to Evelyn Waugh, Celine’s Journey to the End of the Night and Dalton Trumbo’s And Johnny Got His Gun.

Then almost two years ago a British bibliophile wrote to the London Sunday Times: “Can anyone out there account for the amazing similarity of characters, personality traits, eccentricities, physical descriptions, personnel injuries and incidents in Catch-22 and a novel by Louis Falstein, The Sky Is a Lonely Place [published a decade earlier]?” In a subsequent article, the Times noted a passage in both books that describes a bedridden, badly injured pilot. In Falstein’s book, the pilot lies “in a white cast. He looked entombed … like an Egyptian mummy. His arms were broken, and where his legs had been, there were cotton-swathed stumps. Only his face showed out of the cast, and there were openings at the bottom for bodily functions… An orderly, or nurse, held a cigarette for him when he smoked.” In Heller’s novel. “The soldier in white was encased from head to toe in plaster and gauze… A silent zinc pipe rose from the cement on his groin and was coupled to a slim rubber hose that carried waste from his kidneys.” Twice a day a nurse inserts a thermometer into the mouth of this “stuffed and sterilized mummy.”

Apparently dumbstruck by the correspondences, the Times attributed the Falstein passage to Heller, and vice versa. It did, however, provide accurate biographical information about the deceased and long forgotten Falstein who, it turns out, came from the same background as Heller. Both were sons of Russian Jewish emigre parents, came from the same borough of New York, Brooklyn, and served in Italy as airmen in American bomber squadrons. Duff Hart-Davis, son of Rupert Hart-Davis who published Falstein in England, speculated that Falstein and Heller were the same person, and The Sky Is a Lonely Place was “a practice run for Catch-22.”

Heller dismissed this as ridiculous and denied having heard of Louis Falstein or having read his work. “The similarities,” he explained to the Tunes, “come from a common wartime experience.” But then Heller turned around and questioned whether Falstein truly experienced what he wrote about. “Born in 1909, he would have been too old to fly [in WWII]. I don’t know what he was up to. There were a lot of strange people around.”

Days later, in an interview with the Washington Post, Heller insisted, “Given the amount of invention in Catch-22 it would be an amazing coincidence if there were fundamental similarities with Falstein’s novel.”

There the matter rested. No one appears to have read the two books closely and analyzed the comparisons. But in fact, whether through “amazing coincidence” or “common wartime experience,” there are indeed fundamental similarities between Catch-22 and The Sky Is a Lonely Place. While they don’t rise to the level of plagiarism, they do suggest that Heller might have been aware of Falstein’s work and that his fellow Brooklynite was as influential as the internationally renowned authors Heller cited as his sources of inspiration. Far from diminishing the achievement of Catch-22, this places it in its proper context as a distinctly American expression of New York Jewish sensibility, with an emphasis on manic exuberance, verbal pyrotechnics and slapstick comedy.

Falstein’s first person narrator, Ben “Pop” Isaacs, a gunner aboard a B-24, is Jewish, Heller’s central character, Yossarian, is an “Assyrian” crewman on a B-25. While Isaacs is far more earnest and less flamboyant than Yossarian – essentially he’s realistic rather than surrealistic – he is just as determined not to die, just as eager to finish 50 missions and go home – or, alternatively, convince a doctor that he’s too ill and emotionally unstable to go back into the air again. But just as Doc Daneeka bluntly tells Yossarian, “It’s not my business to save lives,” Doc Brown tells Isaacs, “My job is to keep the men in fighting shape, not on ground status.”

So weather and decrepit planes permitting, the two men continue to fly off to bomb unseen enemies for unknown reasons. Like Isaacs, Yossarian doesn’t wear a single flak jacket to protect his chest. He swaddles his whole body in flak jackets. Whenever they’re not airborne and on the brink of death, the characters in both books pass their time drinking, complaining, fretting, crying, playing cards, playing cruel jokes, fighting, visiting brothels and meeting Italians who are either childlike or cunning, venal or full of old world wisdom. Rain occasionally plays havoc with the flight schedule, keeping airmen safe on the ground, but this exposes them to the dangers of jaundice, hepatitis, deadly fevers and the fraying nerves of barracks mates who throw knives and fire off guns.

Focusing on the underbelly of war, Falstein, no less than Heller, populates his fictional world with bizarrely named characters. Mel Ginn, Cosmo Fidanza, Chester Kowalski, Charles Couch, Billy Poat and Jack “Doolie” Dula might have been transformed by Heller into Colonel Cathcart, Colonel Korn, Major Major Major Major and Captain “Aarfy” Aardvark. Falstein’s Master Sergeant Sawyer, like Heller’s Milo Minderbinder, skims off military supplies and foodstuffs to sell them on the black market, while at the same time hustling pornographic photographs. Men in both books have pet cats that sleep on their faces and have to be peeled off each morning. One of Falstein’s characters drives everybody crazy by tinkering with a broken radio, just as a Heller character puts Yossarian into a homicidal rage by disassembling and reassembling a stove. On the first page, Ben Isaacs meets a “stringy young Texan” who never misses an opportunity to fulminate about “niggers.” The title of Heller’s first chapter is “The Texan” and this character exhibits the same savage vocal racism. In both books, a man shrieks every time a bomb drops from the plane, another deals cards in a snappy explosive fashion, and yet another paints a bomb on his flight jacket to mark each successful mission. Everybody watches the red ribbon on the map that marks the advance of American troops and the bomb-line. As the ribbon approaches Vienna, a Falstein character comes down with diarrhea that keeps him from flying. When the ribbon in Catch-22 closes in on Bologna, an epidemic of diarrhea breaks out on the airbase.

In a sense, this best exemplifies the difference between The Sky Is a Lonely Place and Catch-22. In every instance, Heller pushes things further.

Taking as its motto, Whatever is worth doing is worth doing to excess, his novel is three times longer, more ambitious and relendessly comic, but also more repetitive and, in its weaker sections, sophomoric. Where Falstein heightens tension and sustains the narrative momentum in a conventional manner with crash landings, mid-air dogfights and fatal miscalculations, Heller raises the stakes and darkens the laughter in phantasmagorical scenes. Yet it must be remarked that compared to almost any author except Heller, Falstein displays an unparalleled gift for grand guignol violence and subversive humor. He describes military censors who delete words and reduce every letter, even the most banal love note, to gibberish (Heller does the same). He writes of a sergeant who is broken “to the rank of private for being apprehended in a House of Prostitution…without his identification tags” – not unlike Heller’s Yossarian, who is arrested in a brothel for being off base without a pass.

In The Sky Is a Lonely Place, a Christmas party dissolves into a bacchanal of singing, screaming and sobbing, and ends with an outbreak of gunfire that the men mistake for an enemy attack. “There were several more carbine pings, and somebody answered fire with a forty-five pistol.” Late in Catch-22, there’s a Thanksgiving “celebration [that] lasted long into the night, and the stillness was fractured often by wild, exultant shouts and by cries of people who were merry or sick. There was the recurring sound of retching and moaning, of laughter, greetings, threats and swearing, and of bottles shattering against rock.” Heller ends his scene, too, in gunfire as Yossarian charges out of his tent with a forty-five.

Finally, for fans of the X-Files, on page 128 of the British edition of Falstein’s novel, a plane carrying 10 men crashes onto the runway, disappearing so completely medics “couldn’t even find dog tags.” On the same page in the British paperback of Catch-22, a plane flies into a cloud, “disappearing … mysteriously into thin air with every member of the crew.” Coincidence? Or imitation as the sincerest form of flattery?

Granted, Heller had a point when he responded to questions about these similarities by observing that a great deal of war fiction depends on variations on the same themes and archetypes. But a careful reader of both texts could be forgiven for concluding that even at the level of language and linguistic play Heller has written an oblique homage to Falstein. Both authors chronicle the absurdity of existence, the capriciousness of authority and the emptiness of words leeched of meaning by constant abuse. Like the chaplain in Catch-22 who is ordered to compose a funeral prayer that doesn’t mention God or death, the narrator in The Sky Is a Lonely Place learns an early lesson in “airwar language” when he is warned, “never use the word Killed … we say a guy Went Down.”

On every page, the books uncannily echo one another as scabrous jokes, racial epithets, sexual ribaldry and sheer hair-curling craziness pour out of people. Again, Heller pushes it over the top, taking each trope to its limit. But both authors achieve a kind of demotic poetry, as when Falstein writes, “Grazie, Nazi,” and another soldier replies, “Prego, dago.” In Heller there’s rhyming dinner table dialogue, ‘Pass the salt, Walt/ Pass the bread, Fred/ Shoot me a beet, Pete.”

Of course, in a universe of pure contingency where chaos reigns and wars are won or lost by accident, not design, and soldiers survive or perish despite their courage or cowardice, it’s perhaps perfectly possible that two men, neighbors no less, would write hauntingly similar novels, would never meet or read one another and would then slip under the lid of the earth at the far ends of a spectrum that runs from utter obscurity to universal recognition. Talk about Catch-22!

[One of the principal characters in The Thin Red Line, Captain “Bugger” Stein, a career infantry officer and company commander, in an event clearly motivated by antisemitism, is unfairly relieved of his command and sent back to the “Zone of the Interior”, his military career effectively ruined. He vanishes from the story well prior to the novel’s end. Throughout James Jones’ novel, in his depiction of Stein’s personality, character, and confrontation with antisemitism, the author displayed a remarkable degree of perception, if not empathy, with the Captain’s predicament. How does this relate to Malick’s film? Well, though I haven’t viewed it (and have no plans to do so), it’s my understanding that Stein’s identity as a Jew – not entirely central to, but nonetheless a critical part of the novel’s plot and intentionally so – was entirely eliminated from the film, something remarked upon in only a few 1998 reviews. Just sayin’.]

Mentioned Above…

Falstein, Louis, Face of a Hero, Harcourt, Brace & Company, New York, N.Y., 1950

Falstein, Louis, Face of a Hero, Steerforth Press, South Royalton, Vt., 1999

Heller, Joseph, Catch-22, Dell Publishing, New York, N.Y., 1968