WW II Army Air Force Captain William Hays Davidow, a pilot in the 12th Ferry Group and relative of Arthur Hays Sulzberger, publisher of The New York Times, was the ironic subject of an article item published in that newspaper on January 27, 1943. The impetus for that news item’s appearance was Captain Davidow’s sad death in a take-off accident at Accra only six days earlier, on January 21, 1943.

In the above-linked post about Captain Davidow, I presented the small measure of information still that exists about him now, in 2022, seventy-nine years later. Given the passages of almost eight decades since the accident in which he lost his life, coupled with the fact that he left no descendants, his correspondence, military records, and related memorabilia probably no longer exists.

At least, that’s what I assumed as of December of 2021, when I last updated that post!

But fortunately, I stand to have been corrected.

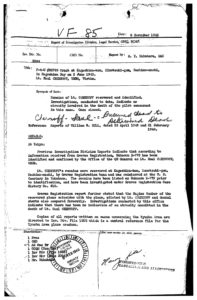

Recently, while researching the Air Force History Index, I was intrigued to come across an entry for an document entitled, “Interview with Capt. W.H. Davidow”, the abstract for which states that the document is an “Interview with Capt Davidow, Pan American World Airway, Covering Clipper Operations in South American, Africa, Middle East, India, and China.” The interview is on AFHRA Microfilm Roll A1272, the document being one of several (I don’t know how many!) categorized under the subject heading, “Intelligence, Army Air Forces”.

Now, that was unexpected.

Comprising twenty-two pages of typewritten text, the document is headed, “Current Intelligence Section, A-2”, and is dated September 23, 1942, and consists of a series of questions by a “Colonel Coiner” to Captain Davidow. Though Colonel Coiner’s full name does not appear in the interview, I think he was Richard T. Coiner, Jr., who eventually rose to the rank of Major General in the Air Force.

Information supporting this suggestion comes from (Major General) Coiner’s biography, which states, “In January 1941, he organized the 19th Transportation Squadron which he commanded until October of the same year when he was named assistant executive to the assistant secretary of war for air. In March 1944 he became the executive.”, and, “From March 1943 until February 1944, he was in Tampa, Fla., first as flying safety officer, Third Air Force, and later at McDill Field as commander of the 21st Bomb Group and then the 397th Bomb Group which he led in its move to England.” The central theme being, that within the time period during which he met Captain Davidow – September of 1942 – he was involved in transportation and flying safety, rather than combat, the latter commencing for him after February of 1944. A West Point graduate like his father, he passed away at the age of 70 in 1980, and is buried at Mission Burial Park South, in San Antonio, Texas.

______________________________

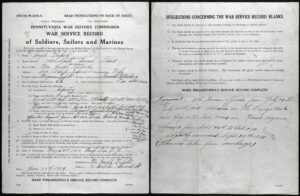

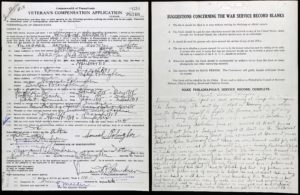

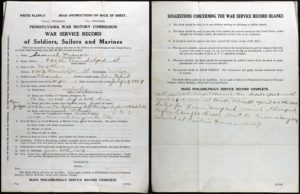

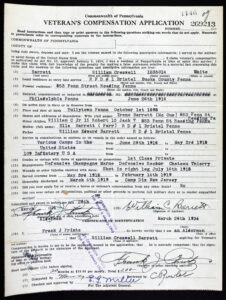

But first, to re-introduce Captain Davidow, here’s some biographical information about him, extracted from and identical to that appearing in the above-mentioned “first” blog post:

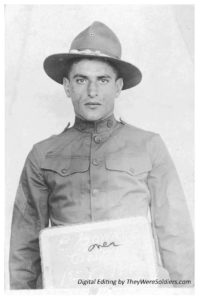

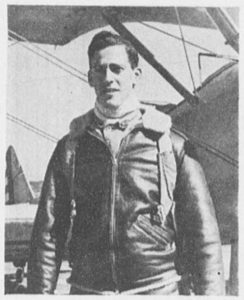

This image of Captain Davidow standing in front a PT-17 Stearman biplane, presumably a semi-official portrait taken during his pilot training, appeared in the Scarsdale Inquirer on November 6, 1942.

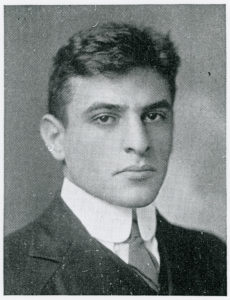

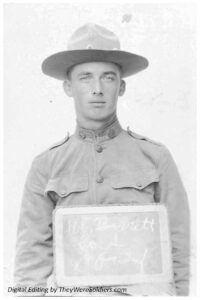

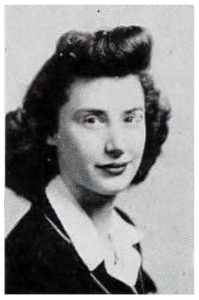

A more formal portrait of William Davidow as a Flying Cadet, from the United States National Archives collection of “Photographic Prints of Air Cadets and Officers, Air Crew, and Notables in the History of Aviation“. (RG 18-PU) Lt. Davidow received his wings on August 15, 1941.

This portrait of William Davidow appeared both in the Times’ obituary and the Lafayette College Book of Remembrance, the latter profiling alumni of Lafayette College (in Easton, Pennsylvania) who lost their lives in World War Two.

______________________________

And so, getting back to the interview?

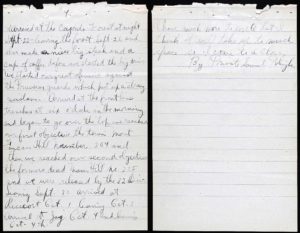

It’s transcribed verbatim, below.

Immediately apparent is the unsurprising but notable fact that the interview focuses on flying, per se, rather than aerial combat, of which – by virtue of Captain Davidow’s assignment as a ferry pilot, geography, and the time-frame of late-1942 – there’s absolutely none. In terms of enemy opposition in general, the only mention is that of being fired upon by the Vichy French while coming in to land at Fort Lamay. (“Fort Lamay”? I think that’s an alternate spelling of Fort-Lamy, which if so (!?) is currently N’Djamena, in the country of Chad, in central Africa.) In a larger sense, the document is an overview of the challenges of flying – in terms of geography, weather conditions, navigation, communications, and the psychological and physical impact of such activity on pilots, in primitive conditions – throughout Africa, and secondarily in south Asia, during an era when flying did not have the naively unwarranted quality of taken-for-grantedness that it does now, in 2022. (At least, for now.)

The document sheds light on Captain Davidow’s sense of conscientiousness and his love of flying, but by definition and nature reveals nothing about him as a “man” … in terms of his personality, beliefs, and opinions. Those thoughts, as they have for all men; as they eventually will for all men, have receded into history.

To enable better comprehension of the interview, I’ve hyperlinked some place names and acronyms, and have provided current or alternate spellings for the names of less commonly known geographic features, cities, or locales. These appear as italicized deep red text, just like “this”.

And so, without further delay…

______________________________

September 23, 1942

Current Intelligence Section, A-2

INTERVIEW WITH CAPTAIN W.H. DAVIDOW

PAN-AMERICAN

oOoOo

Lt. Colonel Coiner: These four captains have just returned from Accra. We are going to ask Captain Davidow, who is to be the spokesman for the group, to tell us about some of their experiences and their operations with Pan-American-African on that route. I believe you fellows also went to India once, didn’t you?

Answer: Yes.

Lt. Colonel Coiner: That was part of the operations. Captain Davidow will lead off and bring us up to the present and the other gentlemen will make such comments as they think appropriate.

Captain Davidow: Well, gentlemen, I will start off with the very beginning. When they first came to get us to go over on this job we were stationed at different fields throughout the country. They came and asked for volunteers to go over for six months, on leave from active duty, to establish this line through Africa. The four of us here today went over from _____ [this word left blank in original document!] School. We were instructors there. We went with Pan-American as co-pilots.

We left from New York by Clipper. We went down to South America – Natal, and over to Lagos, and then to Accra. Accra was then very different from what it is now. We had about six planes over there and operations were very slow. We only ran one or two trips a week, depending on what we had to move. We didn’t have any brake drums on the planes. One plane would come in and slip the brake drums. They would service the plane that just arrived and take our another one.

Conditions over there at first were very bad. We got over there in the fall just after the rainy season. Malaria held up operations quite a bit. We had no adequate medical facilities at that time, but we managed to get through that all right.

Gradually we got more and more personnel over there – more pilots, more planes. First we would just fly from Accra to Takoradi [Sekondi-Takoradi] and Khartoum and over to Bathurst. As time went on we extended our lines up into Cairo and eventually on over to Karachi, running a schedule three times a week, then seven times a week. When we left they were running something like six planes a day over to Freetown and up the line to Cairo, Tehran, and over to Karachi.

Maintenance problems over there were very tough at first. We didn’t have a supply of anything in any great number. Everybody did a pretty swell job and pitched in.

At first a bunch of us – about 12 – were flying with the R.A.F., who didn’t have too much to do. They had an over-supply of pilots. We ferried some Hurricanes and Blenheims from their base at Takoradi to Cairo.

As we got more planes war was declared, cutting out pilot supply off. We couldn’t get any more pilots from the Army. All the men coming over were called back. When our six months were up, they asked us if we wouldn’t stay on. Then we were flying about 145 hours a month. We were flying almost every day. Some months all but two or three days we would fly. They tried to get pilots over to us. We got some pilots – civilian trained boys – who went in as co-pilots. That is what they are using over there now. All the original Army men are checked out. The co-pilots are all C.P.T. [CP.T.P. – Civilian Pilot Training Program] boys with anywhere from 200 hours on up.

As it stood when we left, operations were running a regular schedule up into Cairo and then, as conditions warranted, branching off and going somewhere else. About the time they were having a lot of trouble out in Burma, a group of our boys with 12 planes were called for by the 10th A.F. to act as transport group out there. They operated all over throughout Burma and China – Leiwing, Lashio, and out of Dinjan, evacuating the Burmese and any supplies around in there. Some of the stories they brought back are pretty remarkable. Three or four of the boys took off with 75 people in DC-3s. They are supposed to have 21 people on board. With this load they flew over mountain peaks, no oxygen, 23,000 or 24,000 feet altitude, icing conditions, on instruments, no de-icers. They take all de-icers off. They brought back some pretty interesting information on what a DC-3 could do.

There was nothing very stereotyped about the work there. A job would come up – they would come in and get a bunch of us and say, “We have such and such a job to do. Let’s go.” Just a little while ago, up in the Western Desert, they needed some fuses and 37mm shells in a hurry. I think they had a 48 hours supply left. Rommel was coming in from Mersa Matruh and they didn’t know whether they were going to stop him. They woke the boys up in Accra and sent them down to Lagos, where they picked up the fuses. They flew from Accra to Cairo in 24 or 25 hours, which is a distance of 3,500 miles. They set a record for that run. Of course, the British were there to pick up the fuses and get them on up. That is fairly typical of the stuff they had to do over there.

We got some P-40s in for the A.V.G. [American Volunteer Group] when they were very hard up out in Burma. A group of our men ferried them out. I went as far as Cairo on that. We flew those all the way up across the desert and into Dinjan and down into Kunming. We only lost one plane which was bombed on the way on the ground. Most of the trips we made with no equipment whatsoever in case we met up with the enemy.

On operations out of Accra our crew consisted of two men on board, the pilot and the co-pilot. No navigator or radio operator. The first group of us that got over there about eleven months ago learned the route pretty well. When we started off we had no radio communications at all, no ground-air communications. All we had was a map which was 1/2,000,000 and not too accurate. We had very fine weather. There is very good weather in the fall and right through to the early spring before you get the rainy season. No clouds at all. We were pretty lucky we got to know the route. Now we have radio at every station and by now we have a D/F signal which they turn on for you when requested, at every one of our stations, Accra, Lagos, and Khartoum. They don’t give you anything in Cairo because of Rommel being so close. They give us a warning if an air raid is on.

A few months ago we started operations at night. There were a lot of difficulties caused by it. We had no facilities for that. If we were caught in bad weather and the radio compass went out, we had no way of knowing where we were. Operations were confined to take off at night and flying into daylight so when we got there we had a fair chance of knowing where you were regardless of the weather conditions. They had flown the route actually landing at night. A couple of times they had a little trouble in finding the destination. All of the towers are blacked out. I have come into Kano just after dark and I was close enough to know where I was. If I had been down here (map) on my way up I would have had nothing to check on on a dark night. The native camp fires are all over. There were no beacons and then we didn’t have radio. You can’t just tell – if your dead reckoning is perfect you hit it on the nose.

Weather information over there is very unreliable due to the fact that we have no meteorological stations through the area to give pressure readings and reports daily. We do have stations at Fishermans Lake [Lake Piso or Lake Pisu], Monrovia, and Accra and Khartoum. The rest of them are R.A.F. stations. I would say that their weather reports, on the whole, are fairly unreliable. We can never put too much faith in them. We use them for indications: We go ahead and take a look at it – if it looks good we keep on going … if it looks bad, we go back. The only kind of bad weather you get are the line squalls which can be very severe. In late spring and summer this whole run is made completely on instruments. Ewe make that almost every day. You take off at Accra and climb up over the overcast and go all the way down on instruments and when you get there come in on D/F. If you get a 200 foot ceiling that is fair. If you get a 300 or 350 foot ceiling, it is good. You take off again and come back on instruments. It isn’t very rough; just rain and thick soup.

Weather up here (around Egypt) is mostly sand-storms. Like thunderstorms, with a lot of sand in them. That is about the most rugged thing you meet. That is something we never do try to go through. I tried landing in one at night and it was about the closest I ever came in getting messed up.

Our ground personnel was [sic] very inexperienced at first. We had a bunch of college boys – young boys with no experience with airplanes, or airplane work. They were smart and eager, but they didn’t know very much. You would think sometimes they would give you a fair analysis of the situation that could be depended on. That time I came into Khartoum an hour after dark, they told me there was a 30 mile wind with a little blowing sand. It was dark and all I had was a flare. I landed in a 50 mile cross wind in a sandstorm. I learned a lot. You learned not to trust anything over there except mostly yourself.

The food situation has been all right. We had very good food for the first six months. The second six months the supplies never did come through the way they should have. A lot of stuff spoiled at first because preparations at Accra were not completed at the time the personnel arrived. The generating systems weren’t set up. The housing was bad – no screens and no medical equipment. Sanitary conditions weren’t exactly what they should have been. A lot of meat spoiled and things like that. We always got plenty to eat. Sometimes, though, it was what you might call exotic fare, but on the whole, everything went very well. We all pitched in and everything improved. By the time we left it was a very well-run organization, with trips going out. We kept planes in the air all the time with minimum maintenance. Our loads average up to 90%. Very seldom do you take off without a full load. At first most of them were over-loaded.

If there are any questions at all, I’ll try to answer them.

Question: Your pilots that have been flying across the ocean – did they report seeing any submarines?

Answer: I won’t say many, sir. I guess about ten or twelve. I saw one myself one day I was coming back from Bathurst. I saw one right off Monrovia.

Question: Do they make any attempt to get away from Pan-American ships?

Answer: The one I saw, sir, I don’t know about the others, but one boy said he was fired on. That was pooh-pooed by a lot of the British and Army men over there. They thought it might be that he had been seeing things. The one I saw was sub-surface at periscope depth. I could see the outline of the sub. IU came down fairly close to make sure it was a sub.

Question: Did it dive?

Answer: No sir. It just kept going. He was headed for Marshall where there were 25 ships in the harbor. He was coming down the coast about eight miles off shore. Of course, we didn’t have any guns or anything. I didn’t have any code or any radio operator. I just went back and radioed by voice. I didn’t think I could get them, but I did. I spoke to Accra and Kano, 1,700 miles away. I reported a sub headed for Marshall. They sent out word for the R.A.F. We never heard what happened. That is the way most of it goes. We spot very few. We fly down the coast here all the time. There was the one I saw and one other. Of the Air Ferries and the Army boys coming across, one said he saw four at one time all together. But those cases are fairly isolated.

Question: The reason we asked is that we heard they made no effort to avoid the Clippers at all.

Answer: I don’t believe they did submerge when they saw them.

Question: Are your ships camouflaged like Army ships?

Answer: They were, sir, after December 7. At first they were silver. Some of them were painted desert tan, a sort of yellow, almost. Now they are all green – dark green. It doesn’t help very much in the desert, but it does in flying over this country (map) here.

One other thing I forgot to say – one thing that bothered us a lot – after we had this built up and we were getting 25, 35 or 40 ships on field at a time, B-24s – and up to 40 or 60 P-40s – I don’t remember how many planes, but one night we had about 90 planes on the field and we had four little pop guns for defense and they were handled by native troops of the English Army. We had no defense whatsoever as far as combat aircraft went. Colonel Harden said, “If they don’t come in and bomb us tonight, they are a lot stupider than I think they are.” We didn’t have a thing. We never had any planes capable of going up and engaging any enemy aircraft at all. They could have come in any afternoon, or the middle of the day, and knocked down our operations, that is our headquarters there, which would have disrupted the line for I don’t know how long.

Question: We hear the weather is much worse in Monrovia than Accra. Why would that be?

Answer: I don’t know, sir. All weather charts list heavy rain all the way down and right at Accra there is a little clear circle. It’s pretty bad right in through there, it’s true. In the last three months, before I got back, I hadn’t been into Marshall on a clear day.

It was a circus coming in there. You would have planes coming across the ocean. You would get in there at 1,000 feet and call the radio and ask them if it was clear to come in for a landing. “Yes, the wind is calm in any direction you want.” Just a boy on the radio. I remember one time when he told me that. I took plenty of time to get an approach set and came in and made a landing. No sooner was I on the ground than four planes came right down on the field. They had been right up there with me. One of them was on the field ready to take off. He took off half way down the runway. He looked up and saw a plane landing in the opposite direction on the same runway and so he headed off the runway and burned up.

There was a little confusion down there in had weather before we had any sort of control.

Question: There is a small circle of good weather at Accra?

Answer: Yes, along the West coast there.

Question: Have they got a good control officer in Monrovia now?

Answer: I think the main trouble was that the radio was located in a spot where he couldn’t possibly see the field and wouldn’t be able to see whether it was clear or not. If he didn’t hear anybody else coming in – and many pilots didn’t report or check in with the tower – he would say it was clear for a take-off. They probably have a tower out there now, so that they have a view of the field. It was a pretty bad situation out there then.

Question: Is the emergency landing field at Roberts Port [Robertsport] valuable to you at all?

Answer: We use it a lot, sir. The Clippers all come in at Fisherman’s Lake. We had a good runway there – one end was unusable, because it was raining so much. We would go over there to pick up freight – high priority freight – and passengers coming in by Clipper. That is about twenty minutes flight from Montreal. We would stop at Marshall going over to Fisherman’s Lake on a little runway – nothing but one single sand runway, and pick them up there. If it rains a lot you can’t use it very well. We use it as a regular field, not an emergency field.

Question: What is the largest plane that has been taken in there?

Answer: We took a DC-3 in there with 30 inches of mercury on a damp day. I wouldn’t want to fly in anything heavier. It is just sand. We had a couple of planes stuck there for awhile. In really bad weather we get a lot of rain there. There is no surfacing at all.

Question: What is the Lagos-Calcutta Ferry?

Answer: I don’t know, sir. We operate into Karachi. From Karachi on the regular operations are by Trans-India transport. C.N.A.C. [China National Aviation Corporation] picks it up from there, I think. The only operations we used to do – we tried going through here (map) for awhile – the Southern Route through Arabia. I went through there once and I almost got interned. I made the mistake of staying overnight in a tent and almost got interned. The Sultan wanted to know why I was there. They closed that route – or they had when I left. We ran occasionally to Calcutta [also “Kolkata”]. Ferry some DC-3s out there and stuff like that. I think Pan-American comes in and fly [sic] their planes all the way there themselves. Some of them get out as far as Kunming.

Question: What is your opinion of the route across the north of the Belgian Congo? In case the other line is cut off?

Answer: I have never flown over that country, sir. All of our operations have been up in here (map). I don’t know what the fields are. I know Captain Greenwood surveyed some of that stuff. The airfields when he went there were quite small – in fact he barely got in and out of them.

Question: Do you have any suggestions to make on these operations – things that would make it easier or things that have been done wrong and should be corrected?

Answer: It would help a great deal if we could get competent weather information from men who know their job. Of course, a place like Marshall, with a control system like they have, should be corrected. I guess it is by now. The main trouble at first, from the entrance of the war on, was such a shortage of personnel of our own and of the Army over there. Men were taking over jobs they knew nothing about. Army control officers would be boys who had been meteorologists here and made second lieutenants and were sent over, and the only personnel around some major control officer at a field. The pilots coming through – the Army pilots – didn’t feel they were competent personnel to give orders and to advise them as to what conditions were along the route as far as briefing and everything else went. They were probably excellent meteorologists, or whatever their special field was. I think that condition no longer exists the way it was then.

Question: How about communications? Air-ground radio?

Answer: It started off very poorly. We all had to break in and just before we left it had gotten quite good. Occasionally you would have a little trouble. The thing is so important over there – it’s the only navigation aid we have – if a plane get off course, there are so few little check points throughout there. You may go 300 miles without seeing a check point. You come in on D/F. If you call the station and can’t get him – the operator is asleep or busy, or on another wire. There is a terrific amount of traffic and not enough channels. They are using voice and C.W. [continuous wave Morse Code] on the same channel. They are handling it very well considering the equipment. They need more of it. The airway are jammed most of the time.

Question: How about maps now? Are they better maps?

Answer: The same maps.

Question: Are they putting out any photographs of the route to people at all now?

Answer: No, they haven’t any at all. They are planning to make up new maps though. They requested all captains of the ships to write up a list of their own personal check points, just where they are located, and turn them in to the chief pilot’s office so they may draw up more accurate maps.

Question: I have heard that a lot of the civilian maintenance personnel belonging to Pan-American-Africa are coming back. Do you think that they would go back if they were asked to go?

Answer: I have heard they would, sir. The top foreman over there, who has been over there ever since they got organized – I saw in New York – said all the boys wanted to come back almost 100% for at least a vacation. They were all stuck in one spot and while there most of them were working up to 18 hours a day. In places like Khartoum, were it gets to be 135o, they would work all day in the sun until they just dropped, literally. They lost weight and were in pretty rotten shape. They did a wonderful job and had a swell spirit de corps. They wanted to get home. If they went into the Army now, the Army told them they would try to give them leave as soon as possible. They don’t feel they want to get into the Army until they know exactly. I hear they are coming home and Ryan, the foreman, said he thinks at least 90% of them are perfectly willing to go back if they are asked.

Question: What is the general character of the country between Accra and Khartoum as you fly over it?

Answer: Right in here (map) we fly over water. (All this with map:) This is all jungle. This is Vichy territory. All of this in here is jungle. You come on up here. About in here it starts to think out a little – more bush. It stays bush country all in through here to Port Lamy [N’Djamena], getting dryer and hotter all the time. When you get up to El Fashir [Al Fashir, Al-Fashir or El Fasher] it starts to get desert with occasional bush. Sandy country. From Khartoum on up to Cairo, of course, it is nothing but sand and rock. As far as the terrain goes, in here you have quite a mountain range, goes up to 12,000 feet. You have in between Kano and Lagos various hills, not going up that high. Down south of it, southeast, there are some mountains there. This is all just flat desert, nothing to distinguish it very much.

Question: How do you fly that country from Khartoum to Cairo? Did you ever lose any planes on that route – get lost with all that sand and crap?

Answer: You can’t get lost, sir, if you remember which side of the Nile you are on. The Nile goes right on up. We go straight up. Here you meet the Nile. You meet it again here and here and at Cairo. If you don’t meet it here for awhile, you keep heading in left. If you don’t meet it up here you lose heading in right.

Question: There aren’t any check points?

Answer: The worst place is between Khartoum and El Fashir. There you have nothing. Our check points here – the first place you get a check point is a little mountain 45 minutes out. Then the sand turns white in a spot out here. That is a check point. That is the last check point you have until you hit El Fashir. That is 525 miles, two check points. Actually only one, the mountain is almost at Khartoum. That is the place where we had the most trouble when we had no radio. El Fashir is a tiny little town, must [sic] little black mud huts along the river bank. It is not a river, but a little stream. Streams like that are every 50 yards throughout the country. If you don’t get within five or ten miles of El Fashir, you have no idea where you are. Of course, going up the other way, you always hit the Nile. I know a bunch of our pilots wandered around for a couple of hours trying to find the place. All the airports are so hard to distinguish. You can fly right over top of an airport and never see it. They are not actually towns, just a group of huts, and they look like any other river bank. Most of the river banks in the summer are black with black shrubs. The huts look the same in the air. You can’t see them at all.

Question: Did you have any contact with the Vichy French?

Answer: Yes, at Fort Lamy. Of course, they used to shoot at us.

Question: I mean, did you get a chance to talk to them?

Answer: Yes, but I don’t speak good French.

Question: What, in general, was their attitude toward the Americans?

Answer: They like us. They are a fine bunch. We had several in Fort Lamay. Our of our planes operated with the French for awhile up into the desert.

Question: You are talking about the Free French. How about the Vichy French?

Answer: No contact at all with them. The Free French and not the Vichy French shot at us. They had been bombed and they fired at us even if we were coming in to land.

Wait a minute, I was shot at, and I think somebody else reported they were shot at.

Question: In Vichy territory.

Answer: We were supposed to stay away from all Vichy territories.

Question: There aren’t any spots for emergency landings on the Western end of the route are there?

Answer: Only the coast, sir – the beach.

They have little fields in between Lagos and Kano. They have one field at Oshogbo [Osogbo (also Oṣogbo, rarely Oshogbo]] which you practically never see. It is always overcast, but it is there and a very good field. In here (map) you have little tiny clearings in the sand that are spotted on some maps and aren’t spotted on others. All the way up they have little cleared places and they have been used. B-24s and B-25s have come down there and waited for daylight to find out where they were and go again. Up here (map), of course, you land almost anywhere you want to. They have a fair number of little auxiliary fields, but you can’t bring good equipment in really safely. They are there, but I don’t think you could find them when you needed them.

Question: Do you know from where the airplanes took off that bombed Fort Lamy?

Answer: I don’t believe so, sir. They think they came from Zinder [also Sinder]. That is where they though they came from at one time – I don’t know whether they ever verified this.

It was just one plane that came. Everybody was at lunch. It just flew in and dropped its bombs.

Question: Did you have any trouble over there because the route wasn’t militarized, or have you had any thoughts on that at all?

Answer: I never experienced any personally, but I think the only difficulties were due to a civilian agency working along with the Army in later stages. That comes up anytime you have one group that thinks it is doing a swell job and there is a little rivalry in between. There was a liaison problem there. But as far as we were concerned, we were half and half anyway.

The only thing was they were needing pilots badly there for operations expected of them. Just couldn’t get them anywhere. They were getting a few now and then – also maintenance men and new equipment. That was the chief problem as far as operations and line and equipment. They were doing the best they could. They expected to double their operations and couldn’t do it as a civilian company. Couldn’t just go out and hire the people.

Question: Merely personnel and supply problem rather than personal?

Answer: That was the whole trouble.