“It horrifies and disgusts me to think that the same students that oppose Johnson today –

will rule the nation tomorrow.”

– Corporal Richard E. Marks, July 7, 1965

When I was a young teacher at Cornell,

When I was a young teacher at Cornell,

I once had a debate about education with a professor of psychology.

He said that it was his function to get rid of prejudices of his students.

He knocked them down like tenpins.

I began to wonder what he replaced those prejudices with.

– Alan David Bloom, The Closing of the American Mind, 1987

_____________________________

One of the most compelling forms of literary expression takes the form of correspondence. Whether read by the historian or casual reader, the central value of this form of communication lies in its candor, immediacy, and spontaneity.

Candor, in that – (at least, largely before the advent of digital communication!) the writer could have reasonable certainty of the confidentiality of his words, and feel free to express himself in ways unconstrained by the public eye.

Immediacy, in that – the writer’s thoughts emerge from his participation in or nearness in time and place to most any event, ranging from the mundane to the transcendent: Whether the history of his community or nation; whether experienced by members of his family; within the solitude of his soul.

Spontaneity, in that – a letter can emerge from singular moments of emotional urgency, psychological intensity, and spiritual impact, in ways utterly atypical of the “routine” of one’s life.

Regardless of the era, event, or geographic setting, literary exchanges between friends, comrades, family members, lovers, and certainly even casual acquaintances, can offer a glimpse – typically, far more than a mere glimpse! – into the nature of a historical event, and of greater import, the spirit of an age.

Inevitably, among the most interesting of these written exchanges are those that emerge from military conflicts. Though varying enormously in style, length, and depth, the commonality of such writing is that it offers a view of war unfiltered through the perspective, ideology, or political agenda of those removed from the immediacy, impact, and nature of battle.

A moving example of such literature is the book The Letters of Pfc. Richard E. Marks, USMC, which, published in 1967, is a compilation of the letters sent by Marks – then serving as a machine gunner in Vietnam – to his mother, sister, friends, and teachers.

Within the correspondence comprising the book is this startling passage from July of 1965: “It horrifies and disgusts me to think that the same students that oppose Johnson today – will rule the nation tomorrow. If this is what our colleges and universities are breeding today – I’m just as glad I’m a high school drop out. I just wish there was some way to make those products of higher education realize what fools they really are.”

(The full letter appears below.)

This statement is notable in that it’s one of the very few – if not the only? – occasions on which Richard Marks touched upon politics and “the future”. His words reveal that despite his lack of a formal “higher education” he possessed an intuitive view of a future that by now – in the early 21st Century – has become our present. And which possibly, depending on events and trends yet unknown to us, may – or, may not? – become permanent. Well, perhaps the ability to clearly perceive both the contours of the present and the outlines future is more likely to arise from common sense, intuition, and unfiltered insight, than credentials or inculcated “knowledge”.

Thus, in the words of Rabbi Yosf Hayyim of Baghdad (1835-1909), in his work halakha Ben Ish Ḥai (“Son of Man (who) Lives”), “a collection of the laws of everyday life interspersed with mystical insights and customs, addressed to the masses and arranged by the weekly Torah portion,” regarding The Ethics of the Fathers (Pirke Avot):

“Who is wise? He who sees the future…”

_____________________________

But, who actually was Corporal Richard E. Marks?

Born in New York City on May 31, 1946, he served in 1st Battalion, C Company, 3rd Marine Regiment, 3rd Marine Division. He was one of nine Marines killed on February 14 (Monday), 1966 – or who later died of wounds – when the Amtrac (“Amphibious Tractor”; an LVTP-5) in which they were riding struck a mine and exploded. The location? Five kilometers west-southwest of the Nam-O Bridge, in Quang Nam Province, South Vietnam.

The other eight Marines who were either directly killed in the incident, or died later, were:

Avery, Allen James, Pfc., of Sumner, Ia.

Union Mound Cemetery, Sumner, Ia.

Goggan, Herbert Gary, Cpl., of Houston, Tx.

Forest Park Cemetery (Lawndale), Houston, Tx.

Nichols, Eli Wayne, Pfc., of Lincoln Park, Mi.

Michigan Memorial Park, Flat Rock, Mi.

Wayman, Bobby Ray, L/Cpl., of Huntingburg, In.

Taswell Cemetery, Crawford County, In.

Died February 15, 1966

Stephenson, Waymond Nelson, Pvt., of Anniston, Al.

Forestlawn Cemetery, Anniston, Al.

Died February 16, 1966

Crabbe, Frank Edward, Pfc., of Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Notre-Dame-Des-Neiges Cemetery, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Died February 22, 1966

Olvera, Adan Monsivais, Pfc., of Alice, Tx.

Collins Cemetery, Alice, Tx.

Died February 23, 1966

Rabinovitz, Jack (Yaakov bar Yosef), Cpl., of Dorchester, Ma.

Koretzer Cemetery, West Roxbury, Ma.

Jack Rabinovitz’s matzeva, as photographed by FindAGrave contributor RickD.

Jack Rabinovitz’s matzeva, as photographed by FindAGrave contributor RickD.

_____________________________

As described at July 28/29, 1965 – The Battle for the Ca De River Bridge, at USS Stoddard, “The Ca De (Song) River enters the Bay of DaNang (Vung DaNang) Vietnam from the west. Just off shore the river is spanned by the “Nam O” Bridge, a five span steel structure where “Highway One” and the railroad converge to make the crossing. This is the main route from DaNang to places north such as Phu Bai and Hue.”

Here’s a view (from USS Stoddard) of the destroyed Ca De River Bridge, as it appeared on April 11, 1967…

…while here’s a view of the (repaired) bridge in 1968, from the flickr Photostream of the Frederick J. Vogel Collection at the USMC Archives.

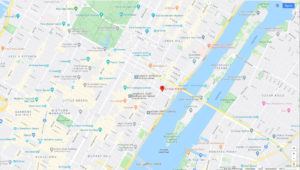

The two Oogle maps below show the location of the Ca De River Bridge with respect to Da Nang, by a blue oval. The lower map also denotes the approximate location of the LVTP’s loss, by a red oval.

The two Oogle maps below show the location of the Ca De River Bridge with respect to Da Nang, by a blue oval. The lower map also denotes the approximate location of the LVTP’s loss, by a red oval.

Here are two views of Marine Corps (LVTP-5) Amtracs, the acronym LVTP standing for “Landing Vehicle, Tracked, Personnel”.

This first image, from Mannhai’s flickr photostream, is captioned, “Delta 1/7 1st MarDiv starts climbing aboard LVTP-5 amphibious tractors to go the Arizona Territory, Vietnam, 2 July 1969. Trucks, jeep, cargo trailers, M149 Water Buffalo trailers in background.” The vehicle in the foreground gives a good impression of an LTVP’s massive size and quite blocky shape. The vehicles had a standard capacity of 34 Marines, but were capable of carrying 45 Marines if necessary. In this image, the viewer is facing the front of the vehicle. Note how the Marine in the lower center of the image is climbing atop the vehicle by a series of built-in foot / handholds.

This image, from the Wikipedia page for the LVPT-5, shows an example on display at the USS Alabama Memorial, in the city of Mobile. The vehicle was photographed in March of 2012 by Vitaly Barsov. In the image, the Amtrac’s front faces left.

This image, from the Wikipedia page for the LVPT-5, shows an example on display at the USS Alabama Memorial, in the city of Mobile. The vehicle was photographed in March of 2012 by Vitaly Barsov. In the image, the Amtrac’s front faces left.

You can view more details of the LVTP-5 at Gun Truck Studios, which shows interior views, probably from the vehicle’s operation or maintenance manual.

You can view more details of the LVTP-5 at Gun Truck Studios, which shows interior views, probably from the vehicle’s operation or maintenance manual.

_____________________________

The genesis of The Letters of Pfc. Richard E. Marks, USMC, published by J.B. Lippincott Company in New York City, is best described in its “Publisher’s Note”.

Namely:

“RICHARD EDWARD MARKS was born in New York City on May 31, 1946. He was raised along with his sister, Susan, in Eastchester, New York, and in California. His father, Robert B. Marks, died in 1963. Shortly afterward, at the close of his sophomore year, Richard left the Hackley School in Tarrytown, New York; subsequently he worked for a time for the Marks Music Company, a family concern.

In the autumn of 1964, Richard E. Marks joined the United States Marines. He was trained at Parris Island and at Camp Geiger in North Carolina, and in May of 1965 he was sent to Vietnam, where he was promoted to Private First Class. On February 14, 1966, he was killed in combat, at the age of nineteen.

During his fifteen months in the Marine Corps, Pfc. Marks wrote almost one hundred letters home. Most of these were to his mother and sister in New York; the rest were to other relatives and friends.

These are the letters of Richard E. Marks as selected and prepared for publication. No corrections have been made as to spelling or other matters of style.”

The book is about 185 pages long, and – comprised of 98 letters written between November 1, 1964 and February 11, 1966 – is organized chronologically, being divided into two sections: 1) “Parris Island: Camp Geiger; Camp Pendleton”, and, 2) “Vietnam”.

As mentioned in the Publisher’s Note, most letters are to Marks’ mother and sister, while the rest were addressed to: Edward Delfino, Peter Whiting, Alfred M. Marks and Family, Herb E. Marks, Steve Kramer, and 2 Lt. Edward Magazine (his brother in law).

Fittingly, Richard’s final letter – not chronologically, but in terms of placement in the book – is his “Last Will and Testament”, penned on December 12, 1965. This letter was held by the Marine Corps and only delivered to Richard’s mother after his burial at Arlington National Cemetery, in mid-February of 1966.

As you can see below, the book’s cover (I believe that publication was limited to this “first” and only hardcover edition) is as symbolic as it is simple, featuring an image of one of Pfc. Marks’ letters, partially removed from an envelope, upon a plain wooden tabletop.

My own copy – you can see the Dewey Decimal number on the cover spine – was once part of the collection of the Southwest Branch of the Arlington Public Library, in Arlington, Texas, and was purchased through ABE Books, prior to the latter’s 2008 absorption by Amazon.com.

As for Richard’s photographic portrait, which appears “above”, at the beginning of this post? That image appears on the back of the cover.

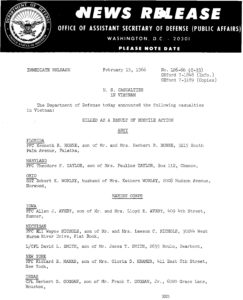

Though the majority of posts at this blog – thus far – have focused on World Wars One and Two and include many historical references from those eras, “this” post provides a view of information – specifically, Department of Defense (formerly War Department) Casualty Lists – from the 1960s.

In the case of Pfc. Marks, his name first appeared on page 34 of Department of Defense News Release “126 / 66 – C-33”, dated 15 February 1966.

The above document (which I created from a PDF) is from one of numerous lists of U.S. Casualties in Vietnam – encompassing release dates January 3, 1966, through December 1, 1969 – which were available some years ago via the South Carolina National Guard, but which no longer seem to be present. (Example: An “original” URL for a list from February, 1966, was “http://www.scguard.com/museum/docs/vietnam/1966/February1966.pdf“. This now generates the response: “404 – Page not found!“.) I’m certain that these Department of Defense “News Releases” were issued through and even beyond 1974, if not longer, but I’ve never seen such documents.

The above document (which I created from a PDF) is from one of numerous lists of U.S. Casualties in Vietnam – encompassing release dates January 3, 1966, through December 1, 1969 – which were available some years ago via the South Carolina National Guard, but which no longer seem to be present. (Example: An “original” URL for a list from February, 1966, was “http://www.scguard.com/museum/docs/vietnam/1966/February1966.pdf“. This now generates the response: “404 – Page not found!“.) I’m certain that these Department of Defense “News Releases” were issued through and even beyond 1974, if not longer, but I’ve never seen such documents.

The “first” list, dated January 3, 1966, is prefaced by explanatory information written by Colonel Julian B. Cross of the Air Force:

The letter reads:

“Very shortly you will start receiving on a weekly basis, the daily Department of Defense News Release listing U.S. casualties in Vietnam.

During World War II and Korea, state Adjutants General were furnished similar casualty information. Adjutants General have found this information invaluable, particularly in later years when requests for the names of local servicemen who died or who were wounded in combat were desired by civic, veteran or other patriotic organizations.

Since the Department of Defense does not retain these lists as part of its permanent records, we strongly urge you to keep these lists, or the applicable portions, as a part of your permanent records for future use. As in the past, we shall continue to refer inquiries addressed to us requesting this information to the Adjutant General of the state concerned.

You will notice in the upper right hand corner of these release a “C” number in parenthesis following the release number. By use of this number you can readily determine if you have missed a listing. If this should occur, write us immediately and we shall supply the missing copy.

We must caution you that there are certain inherent disadvantages in connection with these listings. The information contained therein is based upon current service record information and its accuracy should be treated accordingly. Furthermore, the addresses given are those of next-of-kin as contained in the service record and may not necessarily be the home address of the servicemen.”

_____________________________

Pfc. Marks’ name, and the names of four other Marines and three members of the Army, appeared in The New York Times on February 16, 1966. Though during World War Two newspapers were instructed to publish Casualty Lists and release related information only for servicemen whose next-of-kin resided in the newspapers’ area of geographic coverage – and definitely not the entire United States! – for the Vietnam War, at least during the mid-1960s, the Times – and I suppose other national newspapers? – published all names that appeared in Department of Defense News Releases, regardless of the soldier’s place of residence. Thus, the eight names below, from Florida, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, New York, Ohio, and Texas.

Ironically, though Pfc. Marks’ city of residence is listed as New York City, his residential address is not listed…

…but, his mother’s address, in the above News Release, is listed as “411 East 8th Street”, in Manhattan.

Well, it seems that any apartment or other building at that address no longer exists.

By perusing (the semi-totalitarian panopticon otherwise known as…) Oogle Maps, we arrive – below – at the intersection of East 8th Street and Avenue C in Lower Manhattan, southeast from Tompkins Square Park.

In this view, you’re looking southeast “along” East 8th Street into its intersection with Avenue C. It appears (?) that any section of 8th Street that formerly extended beyond Avenue C no longer exists, having been replaced by a cluster of high-rise residences – New York City Housing Authority apartments? – that now occupy the area between East 8th Street and FDR Drive.

In the below view, you’re looking in the opposite direction: Northwest “into” East 8th Street. DeliCorp is on the corner of 403 East 8th Street.

In the below view, you’re looking in the opposite direction: Northwest “into” East 8th Street. DeliCorp is on the corner of 403 East 8th Street.

But – ! – it turns out that “411 East 8th Street” was not the address of the Marks family. See more below…!

But – ! – it turns out that “411 East 8th Street” was not the address of the Marks family. See more below…!

_____________________________

As for Pfc. Marks himself – as a “person”…?

He was the son of Robert B. and Gloria D. Marks (later Kramer), and had one sister, Susan (later Mrs. Leonard Magazine). His paternal grandfather was Edward B. Marks.

Initially a partner with Joseph W. Stern in the “Joseph W. Stern Music Company”, Edward Marks left that firm in 1894 to found the Marks Music Company, which today exists under the name “Edward B. Marks Music Company – Classical“.

_____________________________

A tribute to Edward B. Marks, from the January 22, 1921, issue of Billboard.

A tribute to Edward B. Marks, from the January 22, 1921, issue of Billboard.

_____________________________

Upon Edward’s passing in 1945, the business was taken over by his son (Richard’s uncle) Herbert. The company was acquired on April 1, 1983, by fellow Brill Building resident Freddy Bienstock (family) Enterprises, and, the estate of Oscar Hammerstein. At least two aspects of the Marks legacy were not only continued but enhanced: the side-by-side publication of popular and serious music, and family ownership. Acquired by both the Bienstock family and the Oscar Hammerstein Estate, Marks Music was held within a group of publishers under Carlin America, Inc. until October, 2017, when Carlin was acquired by Round Hill Music.

You can read the company’s history (from which the above summary was derived) in much greater depth and detail here.

Amidst the information about the Edward B. Marks Music Company and Edward Marks himself, oddly, there’s absolutely no mention of Richard’s own father, Robert.

However, Robert’s perfunctory obituary in The New York Times on May 29, 1963, which states: “We record with dear sorrow the death of Robert B. Marks, president of Piedmont Music Co., Inc., on May 27th, in New York – American Society of Composers Authors and Publishers,” would suggest that Richard’s father “struck out on his own”, and – at least after 1945 – was not affiliated with his brother Edward’s company.

Edward, who passed away on October 4, 1945, and Robert, are both buried at Riverside Cemetery, in Saddle Brook, New Jersey.

As for Richard’s relationship to the family business? He worked at the Edward B. Marks Music Company – then located at 136 West 52nd St., in Manhattan – for one year, under the supervision of Mr. Richard Delfino, prior to his entry into the Marine Corps.

_____________________________

Not long after the publication of the Casualty List listing Richard’s name, the Times published two articles about him (before the appearance of the book itself) by McCandlish Phillips (John McCandlish Phillips, Jr.) and Robert E. Tomasson.

Phillips focused upon Richard’s association with the Hackley School, his experiences in Vietnam, the correspondence with his mother, family, and friends that would eventually form the book, and to a much lesser extent, Richard’s family background. It’s within this review that Richard’s letter of July 7, 1965 is quoted, it seems, with unarticulated approval. Given the history of The New York Times, this was remarkable, considering both the newspaper’s history (see here, here and here) and contemporary ideological agenda (see here and here).

But then again, this was an earlier time, and perhaps an earlier kind of Times.

Tomasson discussed Richard’s last will and testament, which – mentioned above – is the last “item” in his book of collected letters, as well as intimating that Richard’s mother had by then (July of 1966) a publishing firm (unmentioned in the article, but obviously in retrospect Lippincott,) was making financial arrangements with Richard’s mother to publish her son’s letters in book form.

Both articles are, I think, highly at variance with the stereotypical impression of the Times’ coverage of the Vietnam War, in terms of focusing on the life of a specific serviceman – a single Marine – in such depth, detail, and sensitivity.

Why?

Conjecture…

Perhaps because of Richard’s family’s association with the long-established Manhattan-based Edward B. Marks Music Company, of which his father had been vice-president. Perhaps, too (we’ll never know) given the nature of his background and upbringing, Richard did not quite fit any taken-for-granted assumptions (however sometimes valid, and equally, however often invalid) about the nature of those serving in the military, held by the Times‘ editors and writers.

Likewise, strikingly, considering both the “times” and the nature of the Times, the reviews evoke an air of patriotism which seems to be more characteristic of journalism and news reporting from a bygone era: the years of the Second World War.

_____________________________

Another point…

Robert E. Tomasson’s article reveals that information in the Department of Defense News Release about Richard was, simply, incorrect. Tomasson lists the address of Richard’s mother as “411 East 57th Street”, southeast of Central Park in midtown Manhattan, quite some “distance” – geographically and otherwise – from the world of 411 East 8th Street.

An Oogle map and street view showing the actual location of Richard’s mother’s residence are shown below. In the photo, the “411” address refers to the gray high-rise in the center of the image.

And so, on to McCandlish Phillips’ article…

Two Hilltops in a Marine’s Life

One on the Hudson Evoked Memories of Schooldays

Other Was a Lonely Outpost Pounded by Vietcong Fire

By McCANDLISH PHILLIPS

The New York Times

March 6, 1966

While Richard Marks was at the Hackley School in Tarrytown he was a quietly agreeable, serious boy. Sometimes he would roam the school’s wide hilltop clearing and gaze down at the silvery Hudson or climb to the highest outlook to trace the shimmering outlines of the vast city to the south.

Two hilltops became important in Ricky’s life. He loved the high hill at Tarrytown, with its tall shade trees and spell-inducing vistas and the ivy that rustled against the weathered gray stones of the central building. He was one of 380 boys at the preparatory school in 1961 to 1963.

The other hill is just called Hill 69, a combat outpost in Vietnam from which, in the words of one of his letters, “they will probably try to push us off in the next few nights.”

Letters Trace Growth

“It is now dusk and we are observing artillery fire in the area around us – it is truly beautiful in a morbid sort of way,” he wrote to Peter Whiting, a mathematics instructor at Hackley.

This letter, and dozens of others received from combat zones by his mother and Mr. Whiting, tell a story of troopship impressions, excitement at travel, loneliness, yearnings, fright in battle and cherished plans for civilian tomorrows – a story known to thousands of American youths now serving in Vietnam.

The letters of Pfc. Richard E. Marks of the United States Marines – written in small-figured longhand and often running to five pages – trace the expanding consciousness of a young man placed under prolonged and terrible stress.

For Ricky Marks, the transitions from boyhood, to raw Marine recruit, to assault trooper “trained to kill,” to the intensity of battle were very swift.

He was born in New York City and reared in Eastchester and California. His father, Robert B. Marks, vice president of a music publishing firm here, died in 1963.

He entered Hackley as a freshman in 1961, but quit school after his sophomore year. After working briefly, he joined the Marines.

Snapshots sent home show Ricky as a trim, muscular young man 5 feet 10 and 150 pounds, before a low-grade fever began to gnaw him down.

Ricky became a helicopter assault machine gunner in one day (they told him he’d have to learn “the hard way”). At the age of 18 he found what it was to be “scared to death” and to feel his bones “aching all the time.”

The monsoons and combat patrols of Vietnam stripped him of 30 pounds.

Last July his sergeant told him he had nine more months in Vietnam. “I’ll go crazy,” he wrote in a letter to his mother, Mrs. Stephen Kramer.” So far we have already had six Marines in the battalion go crazy, and one Sea Bee. This place is too much for an extended period of time.”

Mission Is Vetoed

“As he saw men die,” whole companies almost wiped out, Ricky, however, came deeply to believe in the military job of “restoring peace to this troubled land.”

From a combat perspective in Vietnam, the letters show, the matters that began perplexing Ricky early were the student demonstrations here in support of Vietcong ambitions and – in his view – political interference with pursuit of the enemy in Vietnam.

“The only complaint I have about our work here is that we cannot do a complete job,” his letter last July 30 to Mr. Whiting said. He cited “red tape” that prevented seizing strategic advantages.

“I have seen on more than one occasion when artillery targets (a large number of V.C. troops) were left unfired upon because the permission to fire had to be okayed by so many people and finally approved by the local Vietnamese official – who in many cases have been proven to be working for the V.C.”

He expressed anger when an air strike was banned against “a meeting of local V.C. leaders and some Chinese advisers … in a valley just outside our [area].”

“The local Vietnamese officials vetoed the mission because there were some cows in the area that might be killed. With foolish circumstances such as this, our forces in Vietnam will never be effective. We will only be effective here when the decision power is returned to the battalion and to company commanders and taken out of the hands of the politically polite, nonmilltant and usually V.C.-oriented men who now have it.”

On July 7 he asked Mr. Whiting:

“How can these people [college and university demonstrators] be serious? Don’t they realize we are fighting the same type of bid for world take-over, here in Vietnam, as we did against Hitler in Europe, and Japan in the Pacific? … We can fight the war now in Vietnam, or in 10 years in Mexico or South America, and maybe even in our own United States.”

Counting the Days

This winter, Ricky began to count the days – 120, 90, 75 – until his time in Vietnam would be up. His letters show increasing eagerness to get back to the States and to visit the Tarry-town campus.

His mother has 77 letters and Mr. Whiting has 11. The first of the letters are filled with Ricky’s impressions of his first ocean voyage.

From the Pacific, after half a day in Honolulu on April 7, 1965, he wrote his mother and his married sister, Sue, that “Waikiki Beach is all and more than it is described as – the beaches are beautiful and the water is a clear, pale blue. The surfers are at it from sunup to past sundown – the bikinis are all, and less, than described.”

On April 8, while at sea, he wrote:

“Tonight I went topside at about 10 P.M., and it is beautiful out – it is a half moon, and the night is clear and warm. The moonbeams were dancing on the water, which is calm as a summer lake. … It makes me feel good to know from here on out there is no one to fall back on but myself – I must accept the responsibilities for all my faults now.

“One of the guys here just asked me where I was from – where is my home? The more I think of it I haven’t really any home to call my own, except the Marine Corps. Being on board ship gives a person a lot of time to think about things. I’ve done a lot of thinking, and have a lot to do.”

On April 14, still at sea, he wrote his mother:

“Last night. I saw ‘Charade.’ Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn – an A.O.K. flick. We will land in Okinawa on Monday morning. … According to rumor we are going to Vietnam.”

Things moved fast then. He thought he would have a month’s special combat training in Okinawa. The reality of war began to come into sharp focus. On April 24, he wrote Mr. Whiting:

“Well yesterday it all came out. Two companies of our sister battalion were almost wiped out by the Vietcong. For the first time I finally realized how serious Vietnam is. Guys I had been with the week before aboard ship were now dead. At first I was sad, then I was angry, and finally I became scared – I still am.

“We are scheduled to leave next Monday and I will be in Vietnam on Wednesday. That means contact by next Friday. That is one day I do not look forward to – I would rather face Mr. Bridges when he was furious. [A reference to the guidance director at Hackley who had remonstrated with Ricky about his grades.]

Learning the Hard Way

“I am attached to an M60 machine-gun team, and I know nothing about machine guns – the way my platoon commander put it: ‘You’ll have to learn the hard way.’ At any rate, this is one time I will not fall asleep in class. I’m going to make the first helicopter assault landing, and I don’t want to miss my chance to practice.”

In one letter to his mother there is this request:

“Send me one bottle of Scotch, packed in popcorn – not only can I eat the popcorn, but it also absorbs much of the shock to the package.”

He joined the Book Find Club from Vietnam, asked his mother for the Old Testament and some plays of Shakespeare and for “Sam Durell” books because “he is a modified James Bond.”

“We love to get pictures of pretty girls, as you must know,” he wrote from Manhdong. “We have all been without the pleasure of female companionship for four months.” Later he wrote that he was “a real monsoon veteran – it has rained for 16 days straight now.”

As the young Marine went through frequent combat and saw men die, he became surer and surer of why he was there.

“I, as a member of the Fourth Marines, am not only helping to further Marine tradition, but I am also, in a small and important way, helping to write 20th century history,” he wrote proudly from the front.

“Each night they probe our lines and throw hand grenades,” he wrote Mr. Whiting from Chulai on July 30. “Due to the noise of the rain and the wind, it is extremely hard to hear them moving in the brush – and obviously much harder to see them. Some day soon, the V.C. will mass and overrun our outposts and then try to destroy the airfield we are guarding.

“Many lives will be lost on both sides, but the airfield will not fall. We are outnumbered here, but we are also’ determined.”

Tired and Aching

“My bones are aching all the time, and I am always tired,” he wrote on Aug. 15, 1965, after four months in Vietnam. He had lost 30 pounds;

His mother wrote to Senator Jacob K. Javits expressing worry about her son. Ricky wrote her that the letter “made me seem like the only person over here involved in the war.”

“Just don’t write anymore – O.K.?” he asked, “There are 45,000 other Marines over here who had stood watch, run patrols, lost weight, had fevers, and seen action, and a hell of a lot of them will never see home again.”

The letters express a deep contempt for the aims and acts of the Vietcong, particularly rape, and a determination to drive them out. But in the gung-ho Marine, the letters show, the civilian remained.

To Mr. Whiting he wrote of a classmate:

“I have been corresponding with Roger B. He told me he has left the University of Pittsburgh, and is joining the Marine Corps. No, I did not suggest it. As a matter of fact, I think he is a damn fool.”

The letters are of dreams, too. Several tell of his decision to get a high school diploma and then to study law in night classes after his discharge.

On Feb. 5 he wrote: “I have just returned today from a patrol that lasted seven nights and six days … the whole time out there I was scared to death … today I was overjoyed at being alive …”

And Now In Print

Not long ago, Mr. Whiting wrote to tell Ricky that excerpts from his letters were to run in the Hackley alumni journal. The Marine replied that he had never been able to get any work of his into the school literary or newspapers “and now, out of a rainy Vietnamese sky, I’m in print. … It is hard to find words to tell you how wonderful that makes me feel.”

At Danang he enjoyed an unexpected-breather. “All of the helicopters have been diverted, therefore our patrol today, which would have required helicopters, has been canceled, thank God,” he wrote. “I figured this patrol I would get a Purple Heart. Nothing serious – just enough to shake the in-sides out of me.”

As the days on his calendar of combat duty in Vietnam dropped from many to few, he wrote Mr. Whiting:

“Please put me down to attend all the events of the Homecoming. From the invitations I realize that many additions have come to the school. … But the old traditional rivalry of Riverdale and Hackley has not changed. I suppose there are some things in the world that never change.”

Ricky was invited by Mr. Whiting to address the student body on April 4. He will not be there.

Instead, a memorial service for him will be held in King Chapel at the school next Sunday afternoon.

Ricky’s Marine dog tag rests now on a table in an apartment in Manhattan: “MARKS. R.E. 2030503 USMC A M JEWISH.”

Last Feb. 14 he was riding in an amphibious tractor near Danang. The machine touched a mine. Light flashed up all around it and he “sustained multiple extreme burns of the entire body,” as the military telegram said.

Ricky was buried on Feb. 21 at Arlington National Cemetery on a gentle slope just below the crest of a hill. He was 19 years old.

_____________________________

And, Robert Tomasson’s…

A Letter Marine Never Wanted Read: His Will

19-Year-Old Vietnam Veteran Killed in Action by Mine

Mother Here Had Received 77 Epistles on the War

The New York Times

July 16, 1966

By ROBERT E. TOMASSON

Tucked away in Pfc. Richard E. Marks’s sea bag in Danang, South Vietnam, was a letter the 19-year-old marine had written but had hoped would never be read.

The three pages from a writing pad were neatly folded and sealed in an airmail envelope addressed to his mother in Manhattan. Instead of a return address at the top, he had written, “Last Will and Testament of Pfc. Richard E. Marks.”

Last Feb. 14 Private Marks was killed in action, and the letter, in which he had written “in the event that I am killed,” has been filed for probate in Surrogate’s Court for the supervised distribution of his remaining possessions.

“First of all,” Private Marks wrote two months before his death, “I want to say, that I am here as a result of my own desire … I am here because I have always wanted to be a marine and because I always wanted to see combat.

“Since I have been here, I have done my job to the best of my ability. I have been scared many times, but I have also been proud an equal number of times.

Fighting for His Beliefs

“I am fighting to protect and maintain what I believe in and what I want to live in – a democratic society.

“If I am killed while carrying out this mission, I want no one to cry or mourn for me. I want people to hold their heads high and be proud of me for the job I did.”

“I don’t like being over here, but I am doing a job that must be done – I am fighting an inevitable enemy that must be fought – now or later.”

According to the court papers, Private Marks estate was estimated at about $5,000, including $500 in savings, four shares of American Telephone & Telegraph stock and about $500 in back pay.

In an affidavit submitted by Private Marks’s mother, Mrs. Gloria D. Kramer of 411 East 57th Street, a publishing firm has agreed to pay $3,500 to the estate for a book based on the scores of letters the young marine sent home.

The 77 letters received by his mother trace the emotions and attitudes of a young man placed under almost continuous combat strain for a cause he felt to be just.

Sister Gets Life Insurance

The standard $10,000 life insurance policy issued to servicemen will be paid to Private Marks’s sister, Mrs. Leonard Magazine of Charleston, S. C.

His sister and mother will also share in $750 in Government bonds, which were not included in the provision of the will since they had previously been named beneficiaries.

His mother will receive 25 per cent of the estate and Mrs. Magazine and her husband the rest.

Private Marks’s father, Robert B. Marks, who had been vice president of a music publishing firm here, died in 1963.

More than a month after Private Marks wrote his will last Dec. 12 he added a note saying that he had named his sister beneficiary of his life insurance policy.

“The reason I am adding this on now,” he wrote, “is because we are about to go on a problem that will be pretty big, and I just want to be sure all this is settled before I go out on the problem.”

It was signed, “Love and kisses, Rick.”

Two weeks later, while out on the “problem,” the amphibious tractor in which he was riding hit a land mine, and he “sustained multiple extreme burns of the entire body,” the telegram to his mother said.

Pfc. Richard E. Marks was buried Feb. 21 at Arlington National Cemetery.

_____________________________

A Monument to Our Vietnam Dead

THE LETTERS OF PFC. RICHARD E. MARKS, U.S.M.C. 185 pages. Lippincott. $3.95.

Courier-Post (Camden, N.J.)

April 22, 1967

The author of this book is dead. He was 19 when the enemy’s bullet tore through his flesh, ending forever his dreams for the future.

Pfc. Richard E. Marks joined the U.S. Marine Corps in November 1964 at the age of 18. In the hectic months that followed, the young Marine was headed, and being trained, for death. He was earmarked for a bullet in Vietnam. During the months of training and through combat, Marks poured out his heart and hopes in a hundred letters, most of them addressed to his widowed mother and his sister. Others were directed to friends, former employers and educators.

The young, impetuous recruit wrote with pride; he lay bare his soul without reservation for he did not write for publication. The missives are intimate, immature, philosophical, didactic, all at once. The collection shows a brave, young American who paid a supreme price for his beliefs.

Under the careful direction of the boy’s mother and the publishers, this collection represents the most graphic description of Marks. They are a reproduction, unedited, of the young man’s thoughts and dreams, his views on politics, economics, religion, sex, marriage – all from the inexperienced position of a teenager who was being made to grow up fast.

The reader will find he immediately identifies with the young Marine whose letters are mostly homey and direct, mostly unaffected, classics of simplicity and directness.

The majority reproduced in this modern “Red Badge of Courage” begin simply “Dear Mom and Sue.” The letters are presented in chronological sequence, divided into two major phases of the boy’s life as a Marine. The first group deals with his training and developing philosophy of the Marine Corps. They are written from Parris Island, S.C., Camp Geiger, N.C., and Camp Pendleton, Calif. The second series come from foxholes and gun emplacements somewhere in Vietnam.

The author had some doubts about his abilities as a new Marine, reflecting on his lack of a high school education. In a letter while in basic training, dated Nov. 19, Marks wrote:

“My hopes for security were shot yesterday – we had a battery of tests and we were told our duty stations would be decided on the results of these tests – so from here on it’s pot luck.”

His letter of Nov. 29, 1964 states in part:

“We had a civilian rabbi, and we said the prayers and lit the candles – it was all very comfortable – just a bunch of guys (20) sitting around and trying to pay homage to God in their own way. I think it is the first real service I have ever seen – no one was forced to be there – and everyone took part – there was something unexplainable about it that was real and wonderful.”

After advanced training, Marks was stationed at Chu Lai Airfield about 100 miles from Da Nang. In a letter addressed to a friend, he wrote:

“This airfield is now protected by nine infantry companies, and an assortment of armored equipment and artillery and God knows what else. All this building up is for one reason – when monsoon season begins in about two months they expect about a division of VCs and Communist Chinese to try and attack and destroy the airfield. It’ll be a damn good fight if they try.”

Although some of his letters lack the luster and polish of a grammarian, they are dynamic because of their mistakes, their simplicity, and their expressions of hope for the future. The only veering from this is that the young author does become somewhat affected in his letters when writing to his former teacher.

This collection of letters, published yesterday, is a fitting monument to all who will not return to the land for which they gave their lives. – WAYNE E. GIBBS

_____________________________

And so, here is Richard’s letter of July 7, 1965, in its entirety:

July 7, 1965

I got a card from you today, and to my knowledge the V.C. have not begun the push yet – at least if they have we have not felt it yet.

Mom, I want to get back to the states just as much as you want me to, but there are no short cuts – I do my tour here just like the other 4,000 Marines I came here with, and we will all leave here at the same time. We should both know by now that there are no short cuts, or easy ways, that pay off – so let’s just forget about Army Special Forces – I’m an FMF Marine.

I also received a letter from Tony today, and he told me you were sending some Bay Rum – I hope it is of the rare J.B. variety. Regiment has lost 18 loads of mail so I hope you didn’t send it before June 28.

The more I read about people opposing the American action in V.N., the more I realize what a short memory people have – we are fighting the same type of world takeover now that we fought in the late 30’s & 40’s, except Johnson is no Chamberlain – we can either fight the war here and now in VN, or in 10 years in Mexico, and South America, or maybe even in our own United States of America. It horrifies and disgusts me to think that the same students that oppose Johnson today – will rule the nation tomorrow. If this is what our colleges and universities are breeding today – I’m just as glad I’m a high school drop out. I just wish there was some way to make those products of higher education realize what fools they really are.

I plan writing Mr. Whiting, and thanking him for his interest in me, and also for making me so happy by knowing that I am still a part of Hackley.

There is no more of interest to write, without entering on the realm of rumor. There are a lot of rumors about when we will be back in the states, and one is we will be home for Christmas – but they told that to the Marines in Korea too.

I close here by saying I am in good health, and have a great tan, and miss you both.

Love & Kisses,

_____________________________

Though I began work on this post in April, I actually first read The Letters of Pfc. Richard E. Marks, USMC in 2009, at which time I was struck – among many aspects of the book – by the prescience of Richard’s observations. Albeit, they’ve not been entirely (entirely) correct about future political developments in Central and South America.

Some years later, I read Alan Bloom’s The Closing of The American Mind.

Though by definition one can’t draw a direct parallel between a few lines within a letter, and, an entire book, taken as a whole, I was nonetheless immediately struck by the consilience of thought between the two: In 1965, Richard saw the direction of the future, while in the mid-1980s, Alan Bloom located the nature of the present – our present – within the recent past.

_____________________________

Below, under “Reflections I”, I’ve provided links to blogs where you can read further, deeper discussions about Bloom’s observations.

_____________________________

In closing, here are two quotes from The Closing of The American Mind (many are apt!) that explain “how we got here” – as a society; as a country; potentially as a civilization.

As to where we’re going, perhaps fortunately, that is yet unknown.

Certainly compassion and the idea of the vanguard

were essentially democratic covers for elitist self-assertion.

…

They themselves wanted to be the leaders of a revolution of compassion.

The great objects of their contempt and fury were the members of the American middle class, professionals, workers, white collar and blue, farmers –

all of those vulgarians who made up the American majority

and who did not need or want either the compassion or the leadership of the students.

They dared to think themselves equal to the students

and to resist having their consciousness raised by them.

It is very difficult to distinguish oneself in America,

and in order to do so the students substituted conspicuous compassion

for their parents’ conspicuous consumption.

They specialized in being the advocates of all those in America and the Third World

who did not challenge their sense of superiority and who,

they imagined,

would accept their leadership.

None of the exquisite thrills of egalitarian vanity were alien to them.

Thus the true elitists of the university have been able to stay

on the good side of the forces of history

without having to suffer any of the consequences.

_____________________________

An advertisement for The Letters of Pfc. Richard E. Marks, published in the Chicago Tribune on April 23, 1967.

______________________________

______________________________

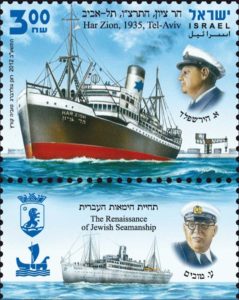

Pfc. Marks’ matzeva (Section 38, Grave 389) in Arlington National Cemetery, photographed by FindAGrave contributor A Horan. He was buried on February 21, 1966.

_______________________________

_______________________________

Reflections I

Michael Kennedy – “The Closing of the American Mind; and worse.” (September 25, 2015)

The New Neo (formerly NeoNeocon)

Harvard and Ronald Sullivan: the dancing bears of the university give in to student pressure (May 16, 2019)

Allan Bloom Quotes to Ponder (November 24, 2018)

Allan Bloom on Undermining the American Vision (March 28, 2018)

Allan Bloom Redux: Education for Tolerance (June 1, 2017)

Allan Bloom on Undermining the American Vision (May 2, 2016)

Allan Bloom: on learning history and cultural relativism (August 26, 2013)

Allan Bloom and the struggle for the soul of the university (June 5, 2009)

Had Enough Therapy? (Stuart Schneiderman)

The American Mind on Therapy (August 29, 2018)

Fabius Maximus (Larry Kumer)

The Founders’ error dooms our Republic, but not the next (January 13, 2020)

SHAZAM! It’s fun indoctrination for kids. (April 8, 2019)

Romance is dying. Intellectuals no longer find it funny. (December 27, 2018)

Origin of the Gender Wars (February 29, 2018)

______________________________

Reflections II

There exists at least one other collection of correspondence by a Jewish Marine who served in the Vietnam War: That of Second Lieutenant Marion Lee Kempner.

A platoon commander in M Company, 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines, 1st Marine Division, Lieutenant Kempner lost his life on November 11, 1966, during “Operation Golden Fleece”, when he detonated a boobytrap while crossing a stream near Binh Son, in Hua Nghia Province.

Born in Galveston on April 16, 1942, he was son of Harris L. and Ruth (Levy) Kempner, and brother of Harris L. Kempner, Jr.

A Graduate of Duke University and a member of the University of Texas Law School Class of 1965, his ashes were scattered at sea near Galveston.

Thirteen years after his death, his father compiled his letters as a lengthy article which appeared in the April, 1979, issue of the American Jewish Archives, under the appropriate title Lt. Marion E. “Sandy” Kempner – Letters from Sandy, by Marion Lee Kempner. This work had been available in PDF format at the American Jewish Archives, but I’m presently – in 2021 – uncertain of its availability.

Very different in total length, literary style, and underlying “mood” from Richard Marks’ writings, Marion’s letters add another dimension to the recollections and reflections of Jewish servicemen in the Vietnam War.

Marion Lee Kempner biographical profile, at FindAGrave

Marion Lee Kempner, at Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund Wall of Faces

Marion Lee Kempner, at Virtual Wall

References, and, Readings-at-not-so-Random

Bloom, Allan, The Closing of the American Mind, Simon and Schuster, New York, N.Y., 1987

Kramer, Gloria D., Editor, The Letters of Pfc. Richard E. Marks, USMC, J.B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia, Pa., 1967

Rubin, Barry, Silent Revolution – How the Left Rose to Political Power and Cultural Dominance, HarperCollins Publishers, New York, N.Y., 2014

Winograd, Leonard, Jungle Jews of Vietnam, Rabbi Leonard Winograd, D.H.L., 1993

The Battle for the Ca De River Bridge, at USS Stoddard

LVTP-5 (Landing Vehicle, Tracked, Personnel), at Wikipedia

LVTP-5s in Vietnam, at flickr photostream of mannhai

LVTP-5 Interior Views, at GunTruck Studios

Rabbi Yosef Hayyim, at Wikipedia

Daily Review of Pirke Avot / Ethics of The Fathers (specifically, Chapter 2, Mishna 3) at DafYomiReview

Blogs

TheNewNeo (formerly NeoNeocon)

Buying (physical ?-!) Books

Letters from Sandy (at ABE Books)

The Letters of Pfc. Richard E. Marks, USMC (at ABE Books) (Like all else in the world of 2020, owned by an oligopoly otherwise known as Amazon(azon(azon)).com.)