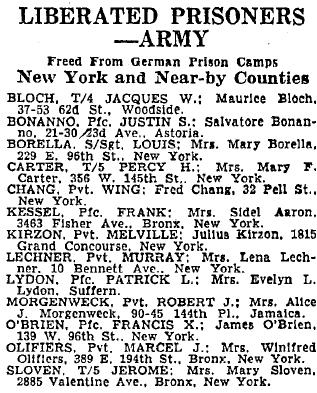

Throughout the Second World War, The New York Times, like other American newspapers, published official Casualty Lists issued by the War (Army) and Navy Departments. These documents followed the same format for both military branches, presenting a serviceman’s surname, first name and middle initial, military rank, and the name and address (whether residential, or place of employment) of the person – usually his next-of-kin – designated to be contacted if he were to become a casualty.

The names which appeared in these lists were only supplied to the news media after notifications had already been sent to their next of kin. Generally, roughly through the summer of 1944, the name of a casualty would appear in a Casualty List approximately one month after the actual date on which he was wounded, declared missing, or known to have been killed in action. In many cases,a serviceman’s name might appear on multiple Casualty Lists. For example, a soldier might be reported missing in action, then confirmed as a POW, and finally – at the war’s end – liberated from a POW camp. In such a case, his name could appear on three Casualty Lists, each pertaining to verification of these successive changes in his status.

A notable difference between Army and Navy Casualty Lists was the Army’s policy of listing casualties by the theater of military operations. Such designations included Africa, Asia, the Central Pacific, Europe, the Mediterranean, North America (during the Aleutian campaign), and the Southwest Pacific, the theater varying with the progression of the war. However, Navy Casualty Lists did not present mens’ names by combat theater.

As issued to the press, Casualty Lists encompassed military casualties from all (then 48) states, as well as the Territories of Alaska and Hawaii. Accordingly, very early in the war, the War and Navy Departments instituted a policy such that newspapers should only publish lists of casualties pertaining to the geographic area of their established news coverage. For example, a newspaper in Saint Louis would not publish names of casualties from Denver or New Orleans; a newspaper in Phoenix would not publish names of servicemen from Nashville or Beaumont; a paper in Denver would not publish names from Lexington or Duluth.

Like other newspapers, such too was the case for The New York Times. In a general – and very reliable – sense, casualty lists in the Times encompassed the five Boroughs of New York (Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens, Staten Island, and the Bronx), Nassau and Suffolk Counties; the metropolitan areas of northern New Jersey; and, southwestern Connecticut.

The lengthiest list, which occupied most of two successive pages, was published on March 29, 1945, based on a nationwide Casualty List that listed the names of 14,443 soldiers and 221 sailors. This list is shown below.

The last Second World War Casualty List carried by the Times, published on June 9, 1946 and illustrated below, was issued by the Navy, and comprised the names of five sailors from New York and two from Connecticut.

The last Second World War Casualty List carried by the Times, published on June 9, 1946 and illustrated below, was issued by the Navy, and comprised the names of five sailors from New York and two from Connecticut.

Though – at the moment of creating this blog post – the pertinent reference is not immediately at hand, Casualty Lists covering the above-mentioned areas of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut probably encompass an unusually large proportion of the 407,316 American military casualties incurred during the war, due to the density and distribution of the American population in the 1940s.

Though – at the moment of creating this blog post – the pertinent reference is not immediately at hand, Casualty Lists covering the above-mentioned areas of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut probably encompass an unusually large proportion of the 407,316 American military casualties incurred during the war, due to the density and distribution of the American population in the 1940s.

__________

There is much more that can be said about this topic, which may be discussed in a future blog post. Or, posts.

__________

And so we arrive at an accidental intersection: Between The New York Times, Jewish military history, and Jewish genealogy.

Related to its publication of Casualty Lists and its reporting of New York Metropolitan area news, the Times published – with a frequency that sadly; inevitably increased as the war progressed – full and often detailed obituaries of military personnel who lost their lives in combat, or, in non-combat related military service. Though obituaries of servicemen would on occasion be published as “stand alone” items in the main section of the paper, they were much more often published within Casualty Lists.

Such obituaries typically included a serviceman’s photographic portrait, whether as a professional studio image, or, a snapshot taken in a more casual setting. Depending on the media and format in which you view back issues of the Times – 35mm microfilm, or PDFs – these images vary greatly in quality. This is due to the quality of the original photograph supplied to the Times, and, the technical limitations then inherent to printing photographs in newspapers. Digital images and 35mm microfilm have unique advantages and disadvantages, depending on the physical nature of these formats themselves, the equipment used to view them, and, equipment and material used to copy and reproduce digital or print (physical) images from them.

Such obituaries were published well into 1946, the “last” such item, for Second Lieutenant Burton H. Roth – a navigator in the 600th Bomb Squadron of 8th Air Force’s 398th Bomb Group, whose B-17 bomber was shot down over Germany on April 10, 1945 – appearing on April 25, 1946.

The criterion – or criteria – the Times used in selecting soldiers who were so covered is unknown. Perhaps some soldiers were chosen at random. Perhaps others had connections – professional; academic; familial – with the Times; perhaps some were members of established and prominent New York area families. (Well, not all seem to have been…)

In any event, what becomes readily apparent upon surveying the Times is at first startling, and then – after a moment’s contemplation – entirely unsurprising: Given the population distribution of American Jewry in the 1940s, many, many of these obituaries pertain to Jewish servicemen in the Army ground forces, Army Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps. As such, these news items provide a moving and illuminating sociological “window” upon Jews of the New York metropolitan area in particular, and Jewish military service in general, in the 1940s.

__________

There are ironies in the lives of nations; there are many ironies in the lives of peoples; ironies abound in the lives of men.

An irony about the appearance of so many obituaries for Jewish servicemen in the Times’ during the Second Wold War is that these news items were published – through a confluence of genealogy, geography, and history – in a periodical whose publisher adhered to a system of belief – classical Reform Judaism – that negated the concept of Jewish peoplehood, and which in terms of the historical legacy of the Times, animated the nature of his newspaper’s reporting of the Shoah.

A vast amount of research and insight – much ink and innumerable pixels – has been generated about this topic. Probably the most outstanding such work is Laurel Leff’s Buried By The Times (prefigured by her American Jewish History article “A Tragic “Fight in the Family”: The New York Times, Reform Judaism and the Holocaust in 2000″). However, the attitude of the Times was obvious to some even as the Second World War was occurring, for it merited scathing coverage in the Labor League for Palestine / Jewish Frontier Association’s publication The Jewish Frontier, through William Cohen’s February, 1942 article “The Strange Case of the New York Times”.

In light of this mindset, the abundance of Jewish military casualties whose obituaries appeared in the pages of the Times may have been perceived by the newspaper’s staff as a simple coincidence, at best. In all likelihood, however, it probably was not perceived – intellectually or emotionally – at all.

Then again… Then again…

Why did the Times, between 1942 and 1951, accord at least 36 news items – including on occasion front-page coverage – to the life, death, and legacy of one specific Jewish serviceman – Army Air Force Sergeant Meyer Levin?

Could this have been because the life and example of Sgt. Levin – at a time when much of American Jewry, even and especially among the most assimilated Jews, perhaps uncertain of the viability of their status as Americans – was viewed as validation of their own patriotism, and a harbinger of their eventual – postwar – acceptance?

Could this have been because the Sergeant’s military service, though he lost his life in the Pacific Theater of War, was perceived as an indirect symbol of Jewish resistance against Germany?

Perhaps both reasons; perhaps more.

Perhaps this, as suggested by Gulie Ne’eman Arad in America, Its Jews, and The Rise of Nazism: “The Americanization experience played a more powerful role in determining American Jewry’s response to the atrocities in Europe than the events themselves, and it is to their American context that American Jews resonated and responded most readily. Their need and desire to conform to their environment were more powerful than other factors, and, once established, the patterns of the behavior that resulted could not be breached until after the apocalypse.”

Much more could be written about this topic; perhaps I’ll do so in the future.

But for now, I hope to bring you posts about Jewish military casualties who were reported upon in The New York Times.

References

Books

Arad, Gulie Ne’eman, America, Its Jews, and The Rise of Nazism, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, In., 2000.

Leff, Laurel, Buried by the Times: The Holocaust and America’s Most Important Newspaper, Cambridge University Press, New York, N.Y., 2005

Journal Articles

Leff, Laurel, A Tragic “Fight in the Family”: The New York Times, Reform Judaism and the Holocaust, American Jewish History, V 88, N 1, March, 2000, pp. 3-51.

Other Articles

Cohen, William, The Strange Case of The New York Times, Jewish Frontier, V 9, N 2, February, 1942, pp. 8-11.

Grodzensky, Shlomo, United Front Against Zionism, Jewish Frontier, V X, N 1, January, 1943, pp. 8-10.

Tifft, Susan E. and Jones, Alex S., The Family – How Being Jewish Shaped the Dynasty That Runs the Times, The New Yorker, April 19, 1999, pp. 44-52

Other References

DeBruyne, Nese F. and Leland, Anne, American War and Military Operations Casualties (Congressional Research Service Publication 7-5700 / RL 32492), at https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RL32492.pdf

World War II Casualties (Wikipedia), at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_War_II_casualties#cite_note-ConResRep_AWuMOC_2010-298