The third and last of three posts presenting excerpts from Face of a Hero, this post presents a transformative point in Louis Falstein’s book: The crash-landing of Ben Isaacs’ crew near Mandia, while returning from a combat mission, due to flight engineer Jack Dula’s misreading of the amount of fuel remaining in their B-24.

____________________

But first, to give an idea, here’s an illustration of a B-24 experiencing a bad landing at Manduria. The aircraft is “Miss Fury“, squadron number 22, 41-29212, a B-24H of the 721st Bomb Squadron, and it’s snapping its port main gear strut while landing on Manduria’s rain-soaked runway on March 13, 1944. Probably manned at the time by Lieutenant Merle W. Emch and his crew, the broken bomber was so badly damaged that it was declared salvage. This set of images taken of the aftermath by the 1st Combat Camera Unit, viewing the aircraft from the left, clearly shows the damage incurred during the landing, and rather watery conditions at the base. (The photo is Army Air Force image 51309AC / A22761.)

As described in the squadron history:

“There was a mission scheduled today to bomb the Gorzia Airdrome in Northern Italy. The mission was scrubbed before the crews were even briefed due to very adverse weather conditions. The rainfall was very consistent and heavy at times. The runway at the present time is very muddy.

“The Squadron received 3 new replacement crews today. Lectures were given to these crews by the Group Operations Officer, Intelligence Section, and Communication Section. Major Davis, the Squadron Commander, gave the crews a general lecture on tactics and military discipline.

“A slight fire broke out in the mess hall at approximately 1600 today but was immediately taken care of. A movie was held at Oria this evening titled, “Presenting Lily Mars”.

The aircraft’s nickname and nose art, shown in the crew and post-crash photos, was inspired by the comic character Miss Fury, created by June Mills (a.k.a. “Tarpé Mills”). Going by Wikipedia (?!) Miss Fury was the first female action hero, appearing in Sunday comic, and, comic book format. She seems to have been a parallel to Batman in not actually possessing super-powers, her strength and speed instead arising from that skin-tight catsuit that she’s wearing. (!)

From MyComicShop, here’s the cover of the second issue of Miss Fury, published in 1942.

____________________

Fortunately in “real life”, it seems that none of Miss Fury’s crew were injured in the plane’s landing accident, unlike the all-too-frequent occasions – in combat or otherwise – which eventuated in the injury, wounding, capture, or deaths of airmen.

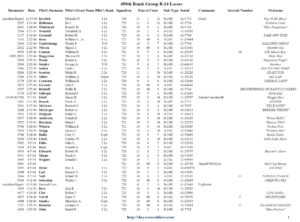

In that regard, “this” blog post includes a list (linked below) of B-24 losses incurred by the Cottontails during the Group’s wartime service, the first page of which is shown here:

Reading from left to right, the data fields comprise:

1) Missing Air Crew Report Number, or secondarily, Accident Report Number

2) Date of Incident

3) Pilot’s surname

4) Pilot’s first (given) name

5) Pilot’s rank

6) Squadron7) Fate of crew, indicated by three-numbers-in-a-row: The “left” number indicates the total number of personnel aboard the aircraft, the “middle” number indicates the total number of survivors, and the “right” number indicates the total number of men who did not survive.

For example, “10-10-0” indicates an aircraft loss in which the entire crew survived; “11-2-9” indicates two survivors of a crew of eleven, and “10-8-2” indicates an aircraft loss where eight crewmen survived.

8) B-24 sub-type (primarily “G”, “H”, “J” versions, with 1 “L”, and 4 “M”s)

9) Aircraft serial number

10) Comments about the plane’s loss, typically for planes lost in accidents

11) Aircraft squadron identification number, as painted on the plane’s rudder

12) Aircraft nickname. In this case, I’ve tried to make the text, whether upper or lower case, or with quotes, identical to that painted on the actual aircraft.

(Next sheet!)

13, 14, 15, and 16) Repetition of the four data fields comprising MACR or Accident Report number, date of incident, pilot’s surname, and aircraft serial

14) General (very general) location of aircraft’s loss

15) Luftgaukommando Report number, if pertinent and / or known

This list was initially created by reviewing all pertinent MACRs, “in-person” at the microfilm reading room at NARA, in College Park, Maryland, via Fold3, and in a few cases, as fiche copies obtained from NARA. Aircraft nicknames and squadron identification numbers are from a variety of sources. These comprise MACRs, Wallace Forman’s published compilation of B-24 nicknames, and of course (!) the Cottontails website. Information about aircraft “not-necessarily-lost-in-combat” – in accidents or other not-immediately-combat-related-events – is also from the Cottontails website, and is combined with and corroborated by information from Aviation Archeology.

Viewing this information as a whole reveals that a total of 1,513 airmen comprised the crews of the 156 B-24s listed in the table, of whom 967 (64%, or about two-thirds) survived. Curiously, if you limit personnel losses to the 131 B-24 losses only recorded in MACRs, the proportions remain almost identical: A total of 1,303 airmen were crewmen aboard these Liberators, of whom 821 (63%; again, about two-thirds) survived.

Aircraft losses by squadrons are:

720th: 44

721st: 36

722nd: 36

723rd: 40

Particularly bad days for the Cottontails – when the group lost five or more B-24s (I picked that number arbitrarily) were February 23, March 24, April 5, April 25, May 24 (the single worst day, with eight planes lost), and June 24, of 1944.

You can view this tabulation HERE, and references correlated to specific planes HERE.

____________________

Now, back to fiction and Face of a Hero, and an event far more serious and devastating…

____________________

The nose gunner – Mel Ginn – dies of his injuries, while the pilot – “Casey Jones” Peterson – grievously injured, survives. All the other airmen emerge alive from their demolished Liberator, but with this incident, the crew’s sense of identity as a crew markedly erodes. And from this point on, the crew’s original sense of unity will completely unravel, through the assignment of new men to fill “vacant” crew positions, the loss of original crew members to other crew, and, combat fatigue.

Here, Lou Falstein’s use of language, whether in terms of his description of events, subtleties of speech, or presenting crewmens’ moods and thoughts is superb. The writing is succinct where it need be and descriptive as it need be. And yes, there is a parallel between the predicament of Peterson and that of a character in Catch-22, which has been remarked upon elsewhere. To quote from Falstein’s novel: “ACROSS FROM my cot lay Casey Jones Petersen in a white cast. He looked entombed in the cast, like an Egyptian mummy. His arms were broken, and where his legs had been, there were cotton-swathed stumps. Only his face showed out of the cast, and there were openings at the bottom for bodily functions. He couldn’t move, nothing of him moved except his eyes. An orderly, or nurse, held the cigarette for him when he smoked.”

The parallel character from Catch-22 can be seen for a fleeting moment in the YouTube trailer for 2019 Hulu’s mini-series, fifty-four seconds “in”. Here’s a screen-shot…

…while you can view the full video here…

Given the crispness of Falstein’s prose, and the clarity and detail with which the crash-landing is described, I’ve wondered if this passage is based on the author’s own experience in the 450th Bomb Group. In that regard, Lou Falstein’s name doesn’t appear in any Accident Report filed by the 450th Bomb Group. Similarly, his name is absent from any of the 16,604 WW II Army Air Force Missing Air Crew Reports (MACRs).

______________________________________

“God, you’re a coward!” I lashed out at myself, “You’re like putty.

You must repeat this over and over to yourself:

This is the only positive thing you’ve ever done!

If you quit you’ll never be able to live with yourself.

Nor will Ruth live with you when she finds out the truth.

Look, take stock, think instead of whimpering like a fool.

At thirty-five a man should act grown up.

Others think you’re grown up.

In Chicago they think you’re a hero.

Most of your friends are either on Limited Service in the army or overage and out of the war.

You’re probably the oldest gunner in Group.

It’s not an honor, but nothing to be ashamed of.

You’ve flown thirty missions.

Not an honor, but some people give up much earlier.

And the war.

Think!

We’re winning.

The Allies are deep in France and the Russians are in Romania.

You’re part of it.

This is your war, remember?

Rekindle your anger.

You must rekindle your anger.

Remember, your life is like a tracer bullet; let it glow once – just once – briefly.

Let it light up the sky for others to see.

Don’t snafu the deal, oh, brother, don’t snafu the deal.

Tomorrow you must get off the cot, crawl if you have to, but get out of here!”

***

He had not looked for gentleness or even conciliation.

“All right, son,” spoken softly by this woman who looked like a mother,

caught him off guard and he was suddenly defenseless.

She had her arm around his waist, leading him back to his cot.

At first he tried to shake her off but soon he gave up the struggle,

and when she helped him onto his cot and raised his legs after he lay down,

Dooley could stand it no longer and wept like a little child.

Only a man does not weep like a child.

A man’s sobs are sounds of anguish and despair.

They come to the surface with the difficulty of dry heaves.

Casey Jones brought the ship off the target with a sharp turn to the right. The Number Four engine was smoking from a direct hit. We were losing gas.

“We’ll catch up with the formation,” the pilot said to Dooley who was on his guns in the top turret, “then you’ll come down and feather Number Four and transfer the gas to the good engines.”

We did not count the holes in the ship. There were a hundred of those, but that didn’t matter because a checkup revealed that nobody had been hurt. We were worried about the dead engine, which would slow us down. But we anticipated no undue difficulties because our escort of Lightnings and Mustangs picked us up off the target to fly us home.

“You know something,” Martin said, “I think we missed the target.”

“Who gives a s_____?” Petersen said.

Over Lake Baloton [sic – Balaton], in Hungary, Dooley started transferring the gas. When he’d drained Number Four, the engineer went to work transferring the remaining gas from the auxiliary tanks, the Tokios. His pumps indicated that the auxiliaries were all drained. But Dooley didn’t know, at the time, that you could not trust the pumps on a B-24. He computed his gas at six hundred gallons, all that was left of the twenty-seven thousand gallons we’d started out with on the mission.

“Are you sure?” Casey Jones asked, a note of concern in his voice.

“That’s what the pumps say.”

“We couldn’t of lost that much gas,” Casey Jones said. “Take another check, will you, mate?”

The panic crept over us in slow, subtle stages, like water inundating an area.

The formation was streaking for home, there were wounded aboard on many of the ships. And in order to keep up with the pace set by the formations, the pilot was feeding the three remaining engines a rich mixture of gas and oil.

“I don’t know,” Casey Jones said. “Be frank with you, I don’t understand what happened to our gas. There should be more of it in those Tokios.”

“Not according to my pumps,” Dooley said. He wasn’t sure of himself-

“In that case, fellas, it’s going to be a tight squeeze,” the pilot said. “We might even have to bail out over Yugo.”

“Maybe we ought to fly her on auto-lean,” the copilot suggested, “even if we have to leave the formation. Save gas that way.”

We dropped out of formation. Chatter died in the ship. We moved as little as possible, as if hoping that inaction would nurse along our gasoline a little longer. “If Pennington were at the stick,” I thought. The ship held no mystery for him. But Pennington was probably on the ground, in Italy, smiling sardonically at our dilemma. Or so it seemed to me.

Over Yugoslavia, Casey Jones called to say: “My indicator is mighty low, fellas, but I’ll try the Adriatic. Take a chance. Might have to crash-land after we cross it. Unless you want to abandon ship here. What do you say? Rugged either way.”

There was no response to the pilot’s words. The silence indicated that the decision was being left up to him. Only one of us had been in a crash landing before — Charley Couch. He was in the waist section smoking a cigarette when the pilot’s words came over the interphone. Suddenly he seized his head with his hands and started shaking it vigorously.

“Oh, God, no,” he whispered. I saw his face drain of the blood and it was almost chalk white. “Not again,” he whispered, rolling his head from side to side. “This time I’m afraid Mama Couch’s boy ain’t gonna make it. Oh, my God, my aching scrotum. I shore musta sinned awful bad.” He sprang to his feet and looked about him in terror as if he’d just awakened from a frightful nightmare. Pressing on his interphone button, he screamed into the mike: “Lieutenant, I’d do anything but crash-land if I wuz you. I done it once, walked away from a ship that hit the dirt, but wasn’t many that walked away with me. We gotta set her down, Lieutenant, why doncha try an’ set her down?”

We’re over water now, Charley,” Casey Jones replied. “But we’ll fly as long as we can. Might even try and make it for home base.”

The mention of home base kindled a brief hope. Momentarily I believed we would make it. We had made it before. Always there was something, but we had made it. Perhaps my caul had something to do with it after all. There were these uncomputed, incalculable, unforeseen factors in war that made the difference between life death. How else explain the incident of the tail gunner who had been shot away from the ship and went hurtling down in his turret and lived to tell the story? And yet, the realization that I was placing my hope on miracles increased my anxiety. I knew that a B-24 was not built for crash landings. (The ship was built to stay on the ground.) But never having been in a crash I did not know what to fear or what to expect. The fact of the matter is, there are all kinds of crash landings. It depends on the space, the terrain, the control of the ship.

We crash-landed suddenly. Six miles from home base. The crash came with such suddenness, our flaps were down only twenty percent. There had been just enough warning from the pilot, who screamed: “DITCHING POSITIONS! HURRY! WE’RE GOING IN FOR A CRASH!”

I was sitting on the floor, leaning my back against the ditching belt, facing to the rear of the ship. Against me, Charley Couch was propped, my legs wrapped around his body, Trent sat between his legs. We were all propping our necks with our hands when the twenty-eight-ton ship telescoped into the ground on its belly. There was a deafening thud accompanied by the anguished cry of crumbling aluminum. I felt as if my insides had been pulled out of me; my eyes were sucked into the back of my head, the delicate fibers dangling, stretched, on fire with pain.

When I was able to open my eyes, I saw dust outside the open waist windows, dust rising on both sides. I listened for explosion or the sound of fire. But I saw only dust. Then I noticed Billy Poat’s lean, bent figure. He rose with difficulty, gripping his middle as if he were holding on to his guts. He moved toward the waist window, leaned over it, and fell out. I heard him shout, call for help. Inside the ship, Trent was bleeding from the head, Charley Couch was moaning softly, trying to get to his feet. He finally succeeded and moved toward the waist window. He was shaking his head like he did when the pilot had made the suggestion about crash landing earlier. His store teeth were dangling, protruding out of his mouth. I saw one of his hands go up, fix his teeth by lodging them in proper place as if he were fixing his toilette before going out to meet a girl. Then he too leaned over the waist window and fell out.

I tried to move, but could not. My hands were feeling about my body for blood; there wasn’t any. I could move my right foot, but not the left one. When I tried to sit up, my body would not give. It seemed nailed to the ship’s belly which was dug into the hard rock.

In the front end of the ship were Casey Jones, Oscar Schiller, Andy Kyle, Dick Martin, Mel Ginn, and Dooley. I heard Dooley’s voice. It was very weak. “We can’t get out up front, you guys. Pilot’s arms, legs broken … in his seat. Mel’s hurt awful bad, unconscious. We’re locked in, you guys. Do something….”

Then I heard the chattering: Italian. And Billy Poat’s voice. “In here,” he said, “mi amicos.” I saw the heads of two Italian laborers.

“Aspetta, aspetta,” one of them said. I pointed toward the front of the ship where the rest of the men were entombed, but the Italians continued saying “Aspetta, aspetta,” and carried Trent and me out and laid us on the ground about fifty feet away from the ship. Then they ran to the front of the plane, led by Billy and Charley who were both bleeding from slight wounds about their faces. They examined the ship carefully, speaking mostly in sign language. One of the Italians took off across the road and came back with an acetylene torch.

“If there’s gas in that plane,” I heard Billy say, “they’ll be blown to hellengone. And so will we,” he added as an afterthought. But he did not move away from the plane.

“I’m for trying it!” Charley counseled. “Ain’t no other way to get ‘em out. By the time the field sends down the meat wagon, fellas are liable to be dead.”

“Okay, paisan,” Billy nudged the Italian. “Drill!”

Did the two Italians realize that they were endangering their own lives by applying the torch to an Americano plane which was full of 100 octane, volatile, highly explosive fumes? If they did, they gave absolutely no indication of it. They seemed completely concentrated on the gun bit which was chewing away at the aluminum body of the plane. Billy and Charley were shouting to Dooley whose face appeared in the glass over the copilot’s seat. The glass had not shattered. “Hold on … Just hold on,” Billy yelled.

The two Italians changed off on the torch. Both of them were dipping sweat from the heat of the hot July sun. Both of them smiled as they worked. Their smiles reached across to us like warm handshakes. Without these two Italians, two men working on a casa six miles away from the airfield, without them my comrades would have perished. By the time the ambulance arrived with Doc Brown and three medics, the two strange Italians, or gooks, as we American called them, sawed off enough of the ship to reach the entombed men. Schiller and Andy almost made it on their own power but Casey Jones was carried out like a sack of broken limbs, and Mel Ginn was an unconscious, bloody mess.

***

ACROSS FROM my cot lay Casey Jones Petersen in a white cast. He looked entombed in the cast, like an Egyptian mummy. His arms were broken, and where his legs had been, there were cotton-swathed stumps. Only his face showed out of the cast, and there were openings at the bottom for bodily functions. He couldn’t move, nothing of him moved except his eyes. An orderly, or nurse, held the cigarette for him when he smoked. “The Doc said I’ll be like a new man after one year in the cast,” the pilot said to Billy, who was on the next cot. “A year won’t take long.” He didn’t know his legs had been amputated. “Looks like you fellows might start shopping around for a new pilot. What do you think, Poatska?”

“Oh, you’ll make it, Lieutenant,” Billy said.

“I sure busted you guys up real bad,” Petersen said. “I’m awful sorry.

“Did the best you could,” Andy said. He and Schiller had walked away from the crash, suffering from shock. An MP had found them wandering on the road and returned them to the base. Every day Andy came to visit us at the hospital.

“How’s Mel?” Dooley asked continually. He could hardly sit up on account of his bruised back, and his eyes were still half shut from the lacerations and cuts. He kept repeating the question in his sleep: “How’s Mel?” When awake he couldn’t keep his eyes off the stumps which had been Casey Jones’s legs. When Dooley discovered Mel was on the Critical List with an internal hemorrhage and busted kidney, he said, “If that kid dies, it’ll be on account of me. The whole thing’s on account of me.” He was sure now the crash had been his fault, but somehow he couldn’t put his finger on it. “I f_____ up some place,” he muttered. He was constantly striving to get up from the cot to be nearer Mel, but the nurse forbade it. “You aren’t ready for it yet,” she said.

“Please, nurse, can I talk to him one minute?”

“Somebody ask for me?” Mel inquired. His eyes didn’t focus any longer and he wasn’t able to see, but his voice was still clear, though weak. “I don’t look my best today,” he would say by way of a joke, “but I’ll be okay by tomorra when you come to see me, I guarantee ya that.”

“Sure you will,” said Mel’s neighbor. He was a Negro from Engineers, with a busted arm that was in a white cast. He was able to walk around, and when the orderlies were not in the ward he offered his help cheerfully. “Anything you want?”

“Wanna write a letter to my wife, Sharon,” Mel said. “I ain’t wrote to her in a coon’s age. Trouble is, fella — “ He hesitated, looked at the colored boy without seeing him and said: “What’s your name, fella?”

“Phil.”

‘You’re my buddy, Phil, my good buddy. Trouble is, Phil, I don’t know what to write half the time. Feel queer as a three-dollar bill ever’ time I sit down to write. Why don’t you just write and tell her I’m doing fine. Just doing dandy. I’ll be much obliged to ya….” He slumped in his bed as if the effort of speaking and the attempt at humor was too much for him. He looked so thin, emaciated, and his skin had the pallor of death.

The heat was unbearable. Though the rooms of this former high school turned hospital were without doors, the air stood still and heavy. Everywhere there were army cots placed so close together there was hardly any room for a patient to put his feet down on the cement floor. The severe cases, like Mel and Petersen, lay in real hospital beds. Above some of the beds were pulleys and weights and limbs dangling from them in the real stateside manner. There were about thirty men in our large room. Nurses flitted in and out, looking Very busy, always looking busy and solemn and just a bit surly as if they disapproved of the goings-on. And always there was a captain from Public Relations walking forlornly among the cots with a stack of Purple Hearts and a list of names. When Dooley saw the captain for the first time he said, “When they write me up for one of them things, I don’t want it. I want no part of it.” The captain was about say something, but he turned away and left the ward.

The only comic aspect in this unbearable place was Leo’s shaven head. His golden hair had been cut right on top of the head where his wound was. A bandage covered the spot. Charley, in the cot next to Leo’s, slept most of the time. Dick Martin hobbled about on a crutch I, too, was promised a crutch.

***

Pennington came to visit us in the evening. I was sorry he came and was relieved when he left. I knew it wasn’t fair to blame him for our disaster. But I couldn’t help feeling it was on account of his heroics that this thing had happened. I watched his face while he talked to us, but he was genuinely sorry and wanted to be helpful. Nevertheless, I hoped he would not come again.

***

The nurse brought me the only book she found on the premises: Salsette Discovers America, by Jules Romains. One passage in the book fascinated me to such an extent I couldn’t get over it: “Your cooks don’t like to prepare sauces [said the protagonist, about America]. Now, sauce is cooking, sauce, I mean, in the broadest sense.” Sauce in the broadest sense!

***

There was no question about it: our crew was finito. They would send Casey Jones back to the States to be placed in a hospital somewhere near Duluth where his wife might come to see him, and hold his cigarette for him. Mel was bleeding internally and there was no way to stop that bleeding. The doctors, majors and lieutenant-colonels stood over him, consulting. But nobody could help him. Mel was bleeding to death. “Phil, where’s Phil?” he chattered feverishly. “Have you wrote that letter to my wife, Phil?”

“I’m working on it —”

“That’s my good buddy.” The words came with difficulty now. “You’re my buddy for life. After I get up — “

Billy Poat lay on his back, stiff, unmoving, staring at the dirty ceiling that had once been pink-colored. Billy stared at the ceiling with a feverish concentration as if he were entranced by the dirt and the flies scampering over it. When he looked at you, his eyes were far away, as if he were contemplating some terrible decision. Dooley hardly spoke at all. The guilt for the crash seeped slowly into him, like a poison. He was sure the crash had been his fault, although he didn’t know what he had done wrong. But at the field, the crew chiefs were not long in determining the cause. They said if Dooley had advised the pilot to raise the bomber’s wings alternately and drain the gas from the wing tanks, instead of relying on the faulty pumps, there would have been no crash. An investigation of the ship disclosed 200 gallons of gas in the auxiliary tanks – after the crash. But Dooley was not told about it while in the hospital. Nothing existed for him except Mel’s thin moans. His own injuries did not concern him. He couldn’t lie still. He couldn’t sleep at night. He was forever watching Mel’s bed. It was like a deathwatch. When he thought Mel needed attention he shouted for a nurse, doctor, or orderly.

***

I had always associated hospitals with the color white. Hospitals were quiet, cool, drowsy places, with long, clean corridors and muted bells and effortless efficiency. Nurses and doctors and even orderlies all worked with purposeful concentration. Ruth had been in such hospitals in Chicago. I’d always loathed them because my wife spent so much time in them, but now I reflected on how restful it would be to lie in one of those quiet, cool, white rooms. And sleep. I had an insatiable need for sleep. Sleep to shut out thoughts of tomorrow and of the chaos here. I would sleep around the clock if they let me. But even in a hospital one was still in the army.

The color was khaki: the cots, the blankets. There were no sheets. The food was served on plates instead of mess kits, but it was still c ration food. Vy-ennas. The orderlies wandered about indolently in the manner of overworked PFCs and corporals who have learned in the Army that the best way to avoid doing anything was to pay no attention to the world about you. And there was the noise, constant noise. Noise and unbearable heat and somber-faced nurses, and naked, peeling walls and hard cement floors. The only note of onerousness was supplied by the venereals who were billeted in tents out in the courtyard. There was no order in the place. There was only chaos and confusion. It was amazing that anybody ever got well there.

***

Through my constant half sleep I heard planes overhead. I knew they were coming back from a raid because it was late afternoon and the heat was suffocating and my cot was wet with perspiration. I wondered what target they’d struck today. I wondered what day it was. It didn’t really matter what day it was. I was lost in the vastness of time. Time and events were a swift whirlpool and I was spinning on the rim of it and there was never an end. I had been in this whirlpool all the conscious years of my remembrance. There had been no other existence. Perhaps there had been a time once, when the hour, the day, the year was of import, when one moved of one’s own volition. But that must have been long ago. Before the army was invented. Before merciful sleep was invented. It was T.S. Eliot who wrote in that poem: “Good night, ladies … good night, sweet ladies … goonight…” A very profound line! When I got out of the army I would sleep forever.

I had a most alarming dream. I dreamed I shot off my big toe on the right foot quite by accident while cleaning my pistol. My comrades took me to the medics’ casa where Doc Brown examined the wound and said: “I’ll give you a letter to the Adjudication Board in Bari, recommending that you be grounded. You can’t fight any more. It’ll take that wound some time to heal, and after it heals that stump will bother you in altitude. Besides, you’ve had enough, Ben.” He put his hand on my shoulder, kindly and warmly. “You’re too old to fly anyway. It was all a fluke, letting you fly in the first place. How many missions have you now? Thirty? That’s good enough. You’re a hero. Fought a good war. My comrades nodded agreement and said: “Doc, he tried his best. Accidents happen, though. He didn’t mean to shoot off that toe. He’s an okay guy, Doc. Nothing phoney about pop.” We all got in a jeep, and suddenly I was alone on the road to Bari. I was abreast of the big sign: AMERICAN MILITARY CEMETERY. Suddenly Cosmo came out on the road and stared at me. “Where you going, doc?” he asked. “No place,” I said. I woke up-What alarmed me was that my subconscious had gone berserk with neat schemes of escape. So the vacillations had been there all the time, lurking where one could not reach for them and tear them out by the roots. The dream frightened me; in fact, it terrified me; in it grasped too eagerly for safety, abandoning my comrades. I was ashamed, and yet it was no lie: I wished it were reality, not a dream. I was tired of endlessly fighting, trying to reconcile my fears with my beliefs and fighting against the army. The struggle had sapped all my energies. The crash had capped it all. I was too old, too tired, too sick…. I wanted to go to sleep and never wake up again. I was tired of this life of conflict and violence. I almost envied Casey Jones. For him there was no more violence. He would be cared for the rest of his life.

But Petersen was a cripple! What would Casey Jones say if he were in mv position? “God, you’re a coward!” I lashed out at myself, “You’re like putty. You must repeat this over and over to yourself: This is the only positive thing you’ve ever done! If you quit you’ll never be able to live with yourself. Nor will Ruth live with you when she finds out the truth. Look, take stock, think instead of whimpering like a fool. At thirty-five a man should act grown up. Others think you’re grown up. In Chicago they think you’re a hero. Most of your friends are either on Limited Service in the army or overage and out of the war. You’re probably the oldest gunner in Group. It’s not an honor, but nothing to be ashamed of. You’ve flown thirty missions. Not an honor, but some people give up much earlier. And the war. Think! We’re winning. The Allies are deep in France and the Russians are in Romania. You’re part of it. This is your war, remember? Rekindle your anger. You must rekindle your anger. Remember, your life is like a tracer bullet; let it glow once – just once – briefly. Let it light up the sky for others to see. Don’t snafu the deal, oh, brother, don’t snafu the deal. Tomorrow you must get off the cot, crawl if you have to, but get out of here!”

***

At night Mel cried feverishly. The nurse kept coming back armed with a hypodermic needle. She had ceased counting three-hour intervals. The doctor had instructed her to give him the needle. “Might as well keep him as comfortable as possible,” he had said. “The poor fellow won’t last much longer.”

“And when you write that letter to Sharon,” Mel whispered hoarsely, his mind already wandering on the periphery of death, “I wancha to say I’m a faithful husban’ to her. And if she stick by me I’m gonna make it up to her. ‘Cause I don’t care any for them Eyetie gals. I guarantee ya that… Just put down ever’thing I say, Phil, ’cause I’m busy right now fixing to shoot down that there ME-109 —”

Dooley crept off his cot and started toward Mel’s bed. The engineer’s face was frozen with terror. “Mel —”

“What is it, Phil? You writing down things like I said?”

“It’s your buddy, Dooley —”

“Well, you just tell her I meant to write alia time, but somehow — didn’t ever get ’round to it. She’ll unnerstan’. She knows I’ll make it up to her. When I git back home — “

The nurse came in the ward and saw Dooley standing over Mel’s bed and said: “You had no business getting off your cot, soldier. You’re not well enough to —”

Dooley paid no attention to her, concentrating his stare, his whole being, on the dying man.

“Soldier, go back to your cot!”

“I gotta help him,” Dooley muttered, talking to himself.

“You can’t do a thing for him,” said the middle-aged, sallow-faced woman who walked with a slow and tired gait and looked so out of place among the young, sturdy, swift-moving nurses. “You can’t do a thing for him, boy. And you’re liable to injure yourself — “

“Somebody’s got to help him, you can’t let him —” He seemed afraid to mention the word “die.”

“We’re trying to make him as comfortable as possible,” the nurse said. “As for you — “

“Comfortable!” Dooley cried. “You’re letting my buddy die! If my buddy dies it’ll be all your fault. It’ll be the army’s fault! I’ll hold you all responsible!” He was suddenly hysterical, hurling his own feeling of guilt at the army, transferring the guilt that had been on him like a terrible weight since the crash. “I’m warning you!” he cried, waving his arms. “I’m — “

“All right, son,” she said gently.

Her words struck him like an unexpected blow. He had not looked for gentleness or even conciliation. “All right, son,” spoken softly by this woman who looked like a mother, caught him off guard and he was suddenly defenseless. She had her arm around his waist, leading him back to his cot. At first he tried to shake her off but soon he gave up the struggle, and when she helped him onto his cot and raised his legs after he lay down, Dooley could stand it no longer and wept like a little child. Only a man does not weep like a child. A man’s sobs are sounds of anguish and despair. They come to the surface with the difficulty of dry heaves.

The ward was silent a moment, then Mel resumed his chatter. “Tell her when I get back home, Sharon and me is going in for ourselves. Ain’t gonna have to live with my old folks no more. Gonna get us some cattle and start in for ourselves, like we said. I do declare, if n there’s one thing I miss in this Eyetieland, that’s seeing cattle. Sure is funny, a land without no cattle. Now you take western Texas —” He sniggered, amused at the thought. He coughed. He lay still for a while. I heard the roar of engines, away in the distant sky. Dooley’s cot creaked. He sat up. We were all sitting up, our eyes glued on Mel’s bed, listening to the last thin fibers of his voice. “I can’t breathe so good … must be my oxygen hose working loose … Damn … Nose gunner to bombardier, nose to bombardier, over; open my turret door and check my hose, I can’t breathe….” He coughed. “Oh, God … oh, God, oh, God —” He died before morning. (pp. 128-139)

Just One Little Reference…

Falstein, Louis, Face of a Hero, Steerforth Press, South Royalton, Vt., 1999