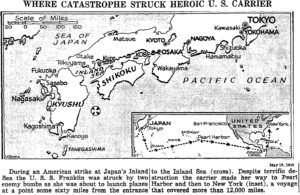

As touched upon in the post “A Minyan of Six? – Jewish Sailors in World War Two: Aboard the USS Franklin and USS Wasp, March 19, 1945 – United States Navy and United States Marine Corps”, Lt. Cdrs. Samuel Robert Sherman of San Francisco and David Berger of Philadelphia both survived the attack on the USS Franklin on that date. Berger received the Silver Star and Sherman the Navy Cross and Purple Heart for their actions, with Lt. Cdr. Sherman’s duty as a flight surgeon including the truly awful task of identifying and “burying” (at sea) very many of the ship’s fallen, not a few of whom he knew personally. He also discusses his extremely difficult interaction with the carrier’s Air Group Commander – the man doesn’t come across too well! – who is left unnamed in his story.

These are the only Jewish crewmen who served on the Franklin whose recollections of that awful day have – as far as I know – been recorded and preserved.

Lt. Cdr. Sherman’s account, which appears at the website of the Naval History and Heritage Command under the heading “Oral Histories – Attacks on Japan, 1945”, with the title “Recollections of LCDR Samuel Robert Sherman, MC, USNR, Flight Surgeon on USS Franklin (CV-13) when it was heavily damaged by a Japanese bomber near the Japanese mainland on 19 March 1945”, was adapted from: “Flight Surgeon on the Spot: Aboard USS Franklin, 19 March 1945,” which was published in the July-August, 1993 (V 84 N 4), issue of Navy Medicine (pp. 4-9).

This (I-assume-1945-ish?) photo, which appears on the cover of Navy Medicine, shows Lt. Cdr. Sherman receiving the Navy Cross. (Photo c/o The National Museum of American Jewish Military History.) …

… while this portrait of a very civilian Dr. Sherman appears in the June, 1962, issue of California Medicine, in an article announcing Dr. Sherman’s April 17, 1962, election as President of the California Medical Association.

Here’s a verbatim transcript of Dr. Sherman’s story:

I joined the Navy the day after Pearl Harbor. Actually, I had been turned down twice before because I had never been in a ROTC [Reserve Officer Training Corps – located at many colleges to train students for officer commissions] reserve unit. Since I had to work my way through college and medical school, I wasn’t able to go to summer camp or the monthly week end drills. Instead, I needed to work in order to earn the money to pay my tuition. Therefore, I could never join a ROTC unit.

When most of my classmates were called up prior to Pearl Harbor, I felt quite guilty, and I went to see if I could get into the Army unit. They flunked me. Then I went to the Navy recruiting office and they flunked me for two minor reasons. One was because I had my nose broken a half dozen times while I was boxing. The inside of my nose was so obstructed and the septum was so crooked that the Navy didn’t think I could breathe well enough. I also had a partial denture because I had lost some front teeth also while boxing.

[An observation: Dr. Sherman’s comments about what seems to have been his extensive experience in boxing are intriguing, for they prompt the question of why someone with his academic background and social status – they had a private airport – would deign to pursue the sport so ardently, to the point of repeated physical injury. To this question I can offer two answers: 1) Samuel Sherman (before he became Dr. Sherman) simply had an innate interest in the sport, and 2) Born in San Francisco in 1906 and a resident of that city, perhaps Samuel Sherman became a boxer – as was not uncommon among Jewish men in American urban environments in the early decades of the twentieth century – as self-defense in the face of antisemitism. Which may become an imperative for American Jews once again, in this world of 2024. And beyond.]

But the day after Pearl Harbor, I went back to the Navy and they welcomed me with open arms. They told me I had 10 days to close my office and get commissioned. At that time, I went to Treasure Island, CA [naval station in San Francisco Bay], for indoctrination. After that, I was sent to Alameda Naval Air Station [east of San Francisco, near Oakland CA] where I was put in charge of surgery and clinical services. One day the Team Medical Officer burst into the operating room and said, “When are you going to get through with this operation?” I answered, “In about a half hour.” He said, “Well, you better hurry up because I just got orders for you to go to Pensacola to get flight surgeon’s training.”

Nothing could have been better because airplanes were the love of my life. In fact, both my wife and I were private pilots and I had my own little airfield and two planes. [This was Sherman Acres , “…situated on what used to be Sherman Army Airfield, a small airfield dedicated in 1941 and used during WWII. … The airport was located on the east side of Contra Costa Highway and straddled present day Monument Boulevard. Sherman Field was located northeast of the intersection of Contra Costa Boulevard and Monument Boulevard.”]

Since I wasn’t allowed to be near the planes at Alameda, I had been after the senior medical officer day and night to get me transferred to flight surgeon’s training.

I went to [Naval Air Station] Pensacola [Florida] in April 1943 for my flight surgeon training and finished up in August. Initially, I was told that I was going to be shipped out from the East Coast. But the Navy changed its mind and sent me back to the West Coast in late 1943 to wait for Air Group 5 at Alameda Naval Air Station.

Air Group 5

Air Group 5 soon arrived, but it took about a year or so of training to get up to snuff. Most of the people in it were veterans from other carriers that went down. Three squadrons formed the nucleus of this air group–a fighter, a bomber, and a torpedo bomber squadron. Later, we were given two Marine squadrons; the remnants of Pappy Boyington’s group.

Since the Marine pilots had been land-based, the toughest part of the training was to get them carrier certified. We used the old [USS] Ranger (CV-4) for take-off and landing training. We took the Ranger up and down the coast from San Francisco to San Diego and tried like hell to get these Marines to learn how to make a landing. They had no problem taking off, but they had problems with landings. Luckily, we were close enough to airports so that if they couldn’t get on the ship they’d have a place to land. That way, they wouldn’t have to go in the drink. Anyhow, we eventually got them all certified. Some of our other pilots trained at Fallon Air Station in Nevada and other West Coast bases. By the time the [USS] Franklin [CV-13] came in, we had a very well-trained group of people.

I had two Marine squadrons and three Navy squadrons to take care of. The Marines claimed I was a Marine. The Navy guys claimed I was a Navy man. I used to wear two uniforms. When I would go to the Marine ready rooms [a ready room is a room where air crew squadrons were briefed on upcoming missions and then stood by “ready” to go to their aircraft. Each squadron had a ready room.], I’d put on a Marine uniform and then I’d change quickly and put on my Navy uniform and go to the other one. We had a lot of fun with that. As their physician, I was everything. I had to be a general practitioner with them, but I also was their father, their mother, their spiritual guide, their social director, their psychiatrist, the whole thing. Of course, I was well trained in surgery so I could take care of the various surgical problems. Every once in a while I had to do an appendectomy. I also removed some pilonidal cysts and fixed a few strangulated hernias. Of course, they occasionally got fractures during their training exercises. I took care of everything for them and they considered me their personal physician, every one of them. I was called Dr. Sam and Dr. Sam was their private doctor. No matter what was wrong, I took care of it.

Eventually, the Franklin arrived in early 1945. It had been in Bremerton [Washington] being repaired after it was damaged by a Kamikaze off Leyte [in the Philippine Islands] in October 1944. In mid-February 1945 we left the West Coast and went to [Naval Base] Pearl [Harbor, Hawaii] first and then to Ulithi [in the Caroline Islands, west Pacific Ocean. It was captured by the US in Sept. 1944 and developed into a major advance fleet base.]. By the first week in March, the fleet was ready to sail. It took us about 5 or 6 days to reach the coast of Japan where we began launching aerial attacks on the airbases, ports, and other such targets.

The Attack

Just before dawn on 19 March, 38 of our bombers took off, escorted by about 9 of our fighter planes. The crew of the Franklin was getting ready for another strike, so more planes were on the flight deck. All of a sudden, out of nowhere, a Japanese plane slipped through the fighter screen and popped up just in front of the ship. My battle station was right in the middle of the flight deck because I was the flight surgeon and was supposed to take care of anything that might happen during flight operations. I saw the Japanese plane coming in, but there was nothing I could do but stay there and take it. The plane just flew right in and dropped two bombs on our flight deck.

I was blown about 15 feet into the air and tossed against the steel bulkhead of the island. I got up groggily and saw an enormous fire. All those planes that were lined up to take off were fully armed and fueled. The dive bombers were equipped with this new “Tiny Tim” heavy rocket and they immediately began to explode. Some of the rockets’ motors ignited and took off across the flight deck on their own. A lot of us were just ducking those things. It was pandemonium and chaos for hours and hours. We had 126 separate explosions on that ship; and each explosion would pick the ship up and rock it and then turn it around a little bit. Of course, the ship suffered horrendous casualties from the first moment. I lost my glasses and my shoes. I was wearing a kind of moccasin shoes. I didn’t have time that morning to put on my flight deck shoes and they just went right off immediately. Regardless, there were hundreds and hundreds of crewmen who needed my attention.

Medical Equipment

Fortunately, I was well prepared from a medical equipment standpoint. From the time we left San Francisco and then stopped at Pearl and then to Ulithi and so forth, I had done what we call disaster planning. Because I had worked in emergency hospital service and trauma centers, I knew what was needed. Therefore, I had a number of big metal containers, approximately the size of garbage cans, bolted down on the flight deck and the hangar deck. These were full of everything that I needed–splints, burn dressings, sterile dressings of all sorts, sterile surgical instruments, medications, plasma, and intravenous solutions other than plasma. The most important supplies were those used for the treatment of burns and fractures, lacerations, and bleeding. In those days the Navy had a special burn dressing which was very effective. It was a gauze impregnated with Vaseline and some chemicals that were almost like local anesthetics. In addition to treating burns, I also had to deal with numerous casualties suffering from severe bleeding; I even performed some amputations.

Furthermore, I had a specially equipped coat that was similar to those used by duck hunters, with all the little pouches. In addition to the coat, I had a couple of extra-sized money belts which could hold things. In these I carried my morphine syrettes and other small medical items. Due to careful planning I had no problem whatsoever with supplies.

I immediately looked around to see if I had any corpsmen [Hospital Corpsman is an enlisted rating for medical orderlies] left. Most of them were already wounded, dead, or had been blown overboard. Some, I was later told, got panicky and jumped overboard. Therefore, I couldn’t find any corpsmen, but fortunately I found some of the members of the musical band whom I had trained in first aid. I had also given first-aid training to my air group pilots and some of the crew. The first guy I latched onto was LCDR MacGregor Kilpatrick, the skipper of the fighter squadron. He was an Annapolis graduate and a veteran of the[USS] Lexington (CV-2) and the [USS] Yorktown (CV-5) with three Navy Crosses. He stayed with me, helping me take care of the wounded.

I couldn’t find any doctors. There were three ship’s doctors assigned to the Franklin, CDR Francis (Kurt) Smith, LCDR James Fuelling, and LCDR George Fox. I found out later that LCDR Fox was killed in the sick bay by the fires and suffocating smoke. CDR Smith and LCDR Fuelling were trapped below in the warrant officer’s wardroom, and it took 12 or 13 hours to get them out. That’s where LT Donald Gary got his Medal of Honor for finding an escape route for them and 300 men trapped below. Mean while, I had very little medical help.

Finally, a couple of corpsmen who were down below in the hangar deck came up once they recovered from their concussions and shock. Little by little a few of them came up. Originally, the band was my medical help and what pilots I had around.

Evacuation Efforts

I had hundreds and hundreds of patients, obviously more than I could possibly treat. Therefore, the most important thing for me to do was triage. In other words, separate the serious wounded from the not so serious wounded. We’d arranged for evacuation of the serious ones to the cruiser [USS] Santa Fe (CL-60) which had a very well-equipped sick bay and was standing by alongside.

LCDR Kilpatrick was instrumental in the evacuations. He helped me organize all of this and we got people to carry the really badly wounded. Some of them had their hips blown off and arms blown off and other sorts of tremendous damage. All together, I think we evacuated some 800 people to the Santa Fe. Most of them were wounded and the rest were the air group personnel who were on board.

The orders came that all air group personnel had to go on the Santa Fe because they were considered nonexpendable. They had to live to fight again in their airplanes. The ship’s company air officer of the Franklin came up to LCDR Kilpatrick and myself as we were supervising the evacuation between fighting fires, taking care of the wounded, and so forth.

He said, “You two people get your asses over to the Santa Fe as fast as you can.” LCDR Kilpatrick, being an [US Naval Academy at] Annapolis [Maryland] graduate, knew he had to obey the order, but he argued and argued and argued. But this guy wouldn’t take his arguments.

He said, “Get over there. You know better.” Then he said to me, “You get over there too.”

I said, “Who’s going to take care of these people?”

He replied, “We’ll manage.”

I said, “Nope. All my life I’ve been trained never to abandon a sick or wounded person. I can’t find any doctors and I don’t know where they are and I only have a few corpsmen and I can’t leave these people.”

He said, “You better go because a military order is a military order.”

I said, “Well what could happen to me if I don’t go?”

He answered, “I could shoot you or I could bring court-martial charges against you.”

I said, “Well, take your choice.” And I went back to work.

As MacGregor Kilpatrick left he told me, “Sam, you’re crazy!”

Getting Franklin Under Way

After the Air Group evacuated, I looked at the ship, I looked at the fires, and I felt the explosions. I thought, well, I better say good-bye right now to my family because I never believed that the ship was going to survive. We were just 50 miles off the coast of Japan (about 15 minutes flying time) and dead in the water. The cruiser [USS] Pittsburgh (CA-72) was trying to get a tow line to us, but it was a difficult job and took hours to accomplish.

Meanwhile, our engineering officers were trying to get the boilers lit off in the engine room. The smoke was so bad that we had to get the Santa Fe to give us a whole batch of gas masks. But the masks didn’t cover the engineers’ eyes. Their eyes became so inflamed from the smoke that they couldn’t see to do their work. So, the XO [Executive Officer, the ship’s second-in-command] came down and said to me, “Do you know where there are any anesthetic eye drops to put in their eyes so they can tolerate the smoke?”

I said, “Yes, I know where they are.” I knew there was a whole stash of them down in the sick bay because I used to have to take foreign bodies out of the eyes of my pilots and some of the crew.

He asked, “Could you go down there (that’s about four or five decks below), get it and give it to the engineering officer?”

I replied, “Sure, give me a flash light and a guide because I may not be able to see my way down there although I used to go down three or four times a day.”

I went down and got a whole batch of them. They were in eyedropper bottles and we gave them to these guys. They put them in their eyes and immediately they could tolerate the smoke. That enabled them to get the boilers going.

Aftermath

It was almost 12 or 13 hours before the doctors who were trapped below were rescued. By that time, I had the majority of the wounded taken care of. However, there still were trapped and injured people in various parts of the ship, like the hangar deck, that hadn’t been discovered. We spent the next 7 days trying to find them all.

I also helped the chaplains take care of the dead. The burial of the dead was terrible. They were all over the ship. The ships’ medical officers put the burial functions on my shoulders. I had to declare them dead, take off their identification, remove, along with the chaplains’ help, whatever possessions that hadn’t been destroyed on them, and then slide them overboard because we had no way of keeping them. A lot of them were my own Air Group people, pilots and aircrew, and I recognized them even though the bodies were busted up and charred. I think we buried about 832 people in the next 7 days. That was terrible, really terrible to bury that many people.

Going Home

It took us 6 days to reach Ulithi. Actually, by the time we got to Ulithi, we were making 14 knots and had cast off the tow line from the Pittsburgh. We had five destroyers assigned to us that kept circling us all the time from the time we left the coast of Japan until we got to Ulithi because we were under constant attack by Japanese bombers. We also had support from two of the new battlecruisers.

At Ulithi, I got word that a lot of my people in the Air Group who were taken off or picked up in the water, were on a hospital ship that was also in Ulithi. I visited them there and was told that many of the dead in the Air Group were killed in their ready rooms, waiting to take off when the bombs exploded. The Marine squadrons were particularly hard hit, having few survivors. I have a list of dead Marines which makes your heart sink.

The survivors of the Air Group then regrouped on Guam. They requested that I be sent back to them. I also wanted to go with them, so I pleaded my case with the chaplain, the XO, and the skipper [ship’s commanding officer]. Although the skipper felt I had earned the right to be part of the ship’s company, he was willing to send me where I wanted to go. Luckily, I rejoined my Air Group just in time to keep the poor derelicts from getting assigned to another carrier.

The Air Group Commander wanted to make captain so bad, that he volunteered these boys for another carrier. Most of them were veterans of the [USS] Yorktown and [USS] Lexington and had seen quite a lot of action. A fair number of them had been blown into the water and many were suffering from the shock of the devastating ordeal. The skipper of the bombing squadron did not think his men were psychologically or physically qualified to go back into combat at that particular time. A hearing was held to determine their combat availability and a flight surgeon was needed to check them over. I assembled the pilots and checked them out and I agreed with the bombing squadron skipper. These men were just not ready to fight yet. Some of them even looked like death warmed over.

The hearing was conducted by [Fleet] ADM [Chester W.] Nimitz [Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas]. He remembered me from Alameda because I pulled him out of the wreckage of his plane when it crashed during a landing approach in 1942. He simply said, “Unless I hear a medical opinion to the contrary to CDR Sherman’s, I have to agree with CDR Sherman.” He decided that the Air Group should be sent back to the States and rehabilitated as much as possible.

In late April 1945, the Air Group went to Pearl where we briefly reunited with the Franklin. They had to make repairs to the ship so it could make the journey to Brooklyn. After a short stay, we continued on to the Alameda. Then the Navy decided to break up the Air Group, so everyone was sent on their individual way. I was given what I wanted–senior medical officer of a carrier–the [USS] Rendova (CVE-114), which was still outfitting in Portland, OR. But the war ended shortly after we had completed outfitting.

I stayed in the Navy until about Christmas time [1945]. I was mustered out in San Francisco at the same place I was commissioned. As far as the Air Group Officer, who said he would either shoot me or court-martial me, well, he didn’t shoot me. He talked about the court-martial a lot but everybody in higher rank on the ship thought it was a really bad idea and made him sound like a damned fool. He stopped making the threats.

5 June 2000

Lt. Cdr. Samuel R. Sherman (0-130988), was born in San Francisoc to Mrs. Lena Sherman on November 17, 1906. He and his wife, Mrs. Marion A. (Harris) Sherman (4/17/13-6/24/98) resided at 2010 Lyon St. (490 Post Street?) in San Francisco. His name appeared in a War Department Release of October 27, 1944, and can be found on page 54 of American Jews in World War II. He received the Navy Cross and Purple Heart. Dr. Sherman passed away on March 21, 1994.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

As a newspaper article and therefore far more topical than retrospective, William Mensing’s Philadelphia Inquirer article about Lt. Cdr. David Berger is of greater brevity than the Naval Medicine article about Lt. Cdr. Sherman. But, it does have an interesting point in its favor: It features a photograph of the Lt. Cdr. with Captain L.E. Gehres, commander of the Franklin, and Lt. Donald A. Gary, who was instrumental in saving so many men on the wounded warship.

PHILADELPHIAN DISCUSSING EXPERIENCES ON FRANKLIN

The Philadelphia Inquirer

May 18, 1945

Lieutenant Commander David Berger (center), of 224 E. Church Road, Elkins Park, assistant air officer on the U.S.S. Franklin, shown with Captain L.F. Gehres (left), the carrier’s skipper, and Lieutenant Donald A. Gary in New York yesterday.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Phila. Officer’s Story Of Ordeal on Carrier

By LIEUTENANT COMMANDER DAVID BERGER

As told to William Mensing, Inquirer Staff Reporter

Philadelphia Inquirer

May 18, 1945

On the morning of March 19, as assistant air officer aboard the Franklin, I was on the bridge of the ship. We were operating with the Fast Carrier Task Force as an air striking force against the Japanese Fleet.

I was standing by the primary flight control assisting Commander Henry H. Hale, air officer, in launching our planes. Many of our planes were on deck fully loaded and ready for the signal to take off.

KNOCKED TO THE DECK

Suddenly there was a terrific concussion and I was knocked to the deck. I must have been out for a matter of minutes. When I came to I got up and was unable to see anything around me. Huge pillars of acrid black smoke pinned me against the “island” structure.

I managed to grope and climb to the “sky forward;” the highest part of the ship. Smoke and flame seemed to envelope the entire ship. There was a series of explosions that rent the air and the concussion, almost made me lose my, grip on an iron rung.

With several members of the crew I threw a line over the star board side and we slid down.

DROPS THROUGH SMOKE

There was a jump of about four feet from the bottom of the line to the gun deck, on which I landed. The smoke was so thick that I thought I was about to fly through I space. The thud of the deck felt good.

We landed in the midst of a 40-millimer gun buttery. We figured it was quits. Smoke kept billowing around us and somehow the other fellows and myself got separated. I couldn’t get my breath. I coughed and started to choke, when suddenly through the black a little bit of blue appeared.

SHIP CHANGES COURSE

Brother, did that blue look good. The sky never was so welcome to anybody. I crawled toward, the air space on my stomach and sucked in all the air I could get. About that time the captain turned the ship around and by doing so changed the course of the smoke and saved a lot of us from suffocating.

After that as many of us as were left after the initial explosions and the all-enveloping inferno formed into volunteer fire fighting groups. We fought the fires all that day and well into the next.

While, some were fighting the fires others formed into rescue squads to reach the men trapped below decks in various compartments.

ATTACKED AGAIN

During the second day of that living hell we were attacked again. I was in a very uncomfortable place in the hangar deck examining the wreckage caused by the fire and explosions. It was one mass of twisted and tangled steel and rubble.

I made my way through the wreckage to the flight deck. We were still being attacked and, brother, it was hot. The deck was hot from the fires, the weather was hot, everybody was hot. I tried to crouch behind the mount of a five-inch gun.

GUN READY TO EXPLODE

It wasn’t very comfortable in the crouching position. I turned and suddenly realized that the gun itself was smoking like the very devil and about ready to explode. Did I clear out!

Finally the attack planes disappeared and we went back to our fire-fighting task. The experience on the Franklin was about the worst thing I have ever gone through. The sinking of the Hornet seemed like nothing in comparison when I look back on the whole nightmare.

PHILA. MAN PRAISED

Every member of the Franklin’s crew was a hero. It seems almost impossible to single out any one man or group of men. However, I can’t help thinking of the heroic work done by one particular Philadelphia boy.

He is Willie Cogman, of 1412 S. Chadwick St., Negro, Steward’s Mate, who was the Captain’s steward. All the survivors performed innumerable, tasks in the emergency. Cogman was one of a group of Negro sailors who, directed by Commander Joe Taylor, rigged the Franklin for tow.

LONG AND TEDIOUS WORK

It was a torturous job and took long and tedious work. Early in the afternoon, the day after we were first bombed, Cogman and his men had the ship ready to be taken in tow by the cruiser Pittsburgh. For his heroic efforts I am given to I understand that he will receive a Navy award.

Throughout the whole ordeal there were countless personal acts of heroism and every member of the Franklin’s crew and officers acted according to the highest traditions of the Navy.

I look forward to the day when I can get back to Philadelphia and tangle in the legal battles, but not until we get back for a final crack at those Japs.

Phila. Lawyer

LIEUTENANT COMMANDER DAVID BERGER, 32, husband of Mrs. Harriet Fleisher Berger, of 224 R. Church Road, Elkins Park, was assistant air officer aboard the carrier Franklin.

He is the son of Mr. and Mrs. Jonas Berger, of Archibald, Pa. A graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Law School, Commander Berger is a member of the Philadelphia Bar. Prior to entering the Navy as a Lieutenant (j.g.) in March, 1942, he served with the Alien Registration Commission.

Commander Berger is one of the survivors of the carrier Hornet, sunk in the Battle of Santa Cruz in 1942. He is also a recipient of a Presidential Unit Citation as an officer on the carrier Enterprise, veteran of Pacific battles.

Lt. Cdr. David Berger (0-136584) was born in Archibald, Pa., on September 6, 1912, to Jonas (7/9/85-2/28/55) and Anna (Raker) (1/88-2/7/60) Berger; his brothers and sister were Ellis, Norman, Shea, Rose, and Leah, the family residing at 224 Church St. in Elkins Park, Pa. A graduate of the law school of the University of Pennsylvania, he was the husband of Harriet M. (Fleisher) Berger, of Archibald. The Assistant Air Officer of the Franklin, he was rescued after the sinking of the USS Hornet on October 26, 1942. Along with the above article and photo in the Philadelphia Inquirer of May 18, 1945, his name appeared in a Casualty List released on May 22, 1945, and can be found on page 510 of American Jews in World War II. He passed away on September 22, 2007.

References

Dublin, Louis I., and Kohs, Samuel C., American Jews in World War II – The Story of 550,000 Fighters for Freedom, The Dial Press, New York, N.Y., 1947

Herman, J.K., Flight Surgeon On the Spot: Aboard USS Franklin 19 March 1945, Navy Medicine, July-August 1993, V 84, N 4, pp. 409

Hoehling, Adolph August, The Franklin Comes Home, Hawthorn Books, New York, N.Y., 1974

Webb, Eugene, Samuel R. Sherman, M.D., C.M.A. President-Elect, California Medicine, June, 1962, V 96, N 6, pp. 429-430