The chronicle of Jewish military casualties for April 2, 1945, is not yet complete, for an additional name must be added: Lieutenant Ernest Willy Rosenstein of the South African Air Force.

But, his story can only be told by way of the life of his father: Leutnant d.R. Willy Rosenstein, who served in the Imperial German Air Service during the First World War…

A cliché; brief, yet valid, describing a perennial aspect of human nature.

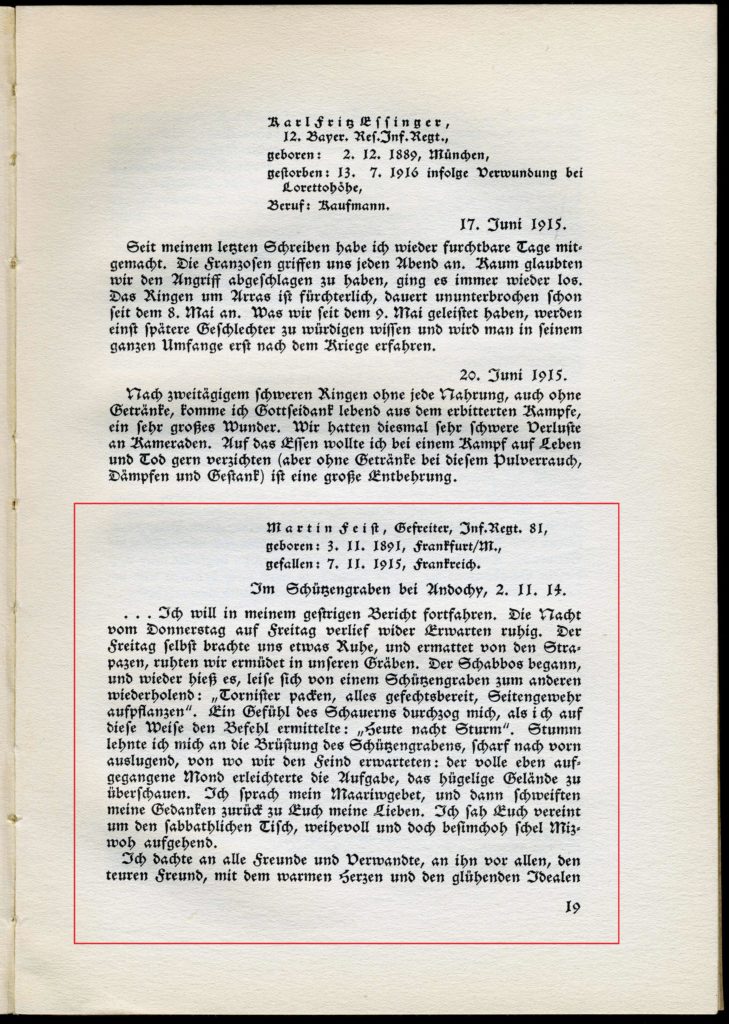

While hardly true for all families, there sometimes occurs striking similarities across the lives of parents and children: Some sons indeed recapitulate the paths of their fathers, as least as much as the intersection between human decision and the spirit of an era will allow. Yet, even as men make choices and “act”, the course of their lives – however fleeting; however lengthy – appear to be carried upon currents of chance: sometimes benevolent; sometimes callous; often puzzling. As noted by World War One Orthodox German-Jewish soldier Martin Feist, contemplated from the finite perspective of man – the decree of God can indeed appear to be unsearchable. Thus for “mankind” in the abstract; thus for men as individuals.

Such was epitomized some seven decades ago, one month before the end of the Second World War in Europe.

On the second of April in 1945, a Royal Air Force Spitfire was lost during a combat mission over Italy. Its pilot, Ernest Willy Rosenstein, a 22-year-old Jew who like his parents had been born in Germany, did not survive.

As had lived the son, so had – for a time – lived the father, Willy Rosenstein.

Born in Stuttgart (1) in 1892, Willy was an aviator and aerial “ace” in Germany’s World War One Air Service, the Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte, in which he attained nine (or ten?) aerial victories in combat against Britain’s Royal Air Force and France’s Armée de l’Air, while flying alongside such figures as Hans Jeschonnek (future Chief of Staff of the Luftwaffe), six-victory ace Herman Gilly, Pour le Mérite winner Carl Degelow, and – with tremendous irony – Herman Göering. A figure within the automotive and especially the aviation worlds of pre-war Germany, he would survive “The Great War” and eventually return to those fields of endeavor, becoming an amateur racing-care driver, while enjoying private flying at Böblingen (a town in Baden-Württemberg). However, technology and military service were not the only; hardly the central, embodiments and definitions of his life. Forced to leave Germany with the advent of the Third Reich, he would in 1936 settle in South Africa with his family. Alas; as a husband and father; as an immigrant whose adopted homeland would eventually be at war with the land of his birth; and as the father of an only son, time and chance never gave him a solid respite from the winds of the twentieth century.

If any respite, at all.

______________________________

The above is a very brief recapitulation of Willy’s life, but rather than present the entirety of his story, “this” post actually serves as a steppingstone for an account of the brief life of his son.

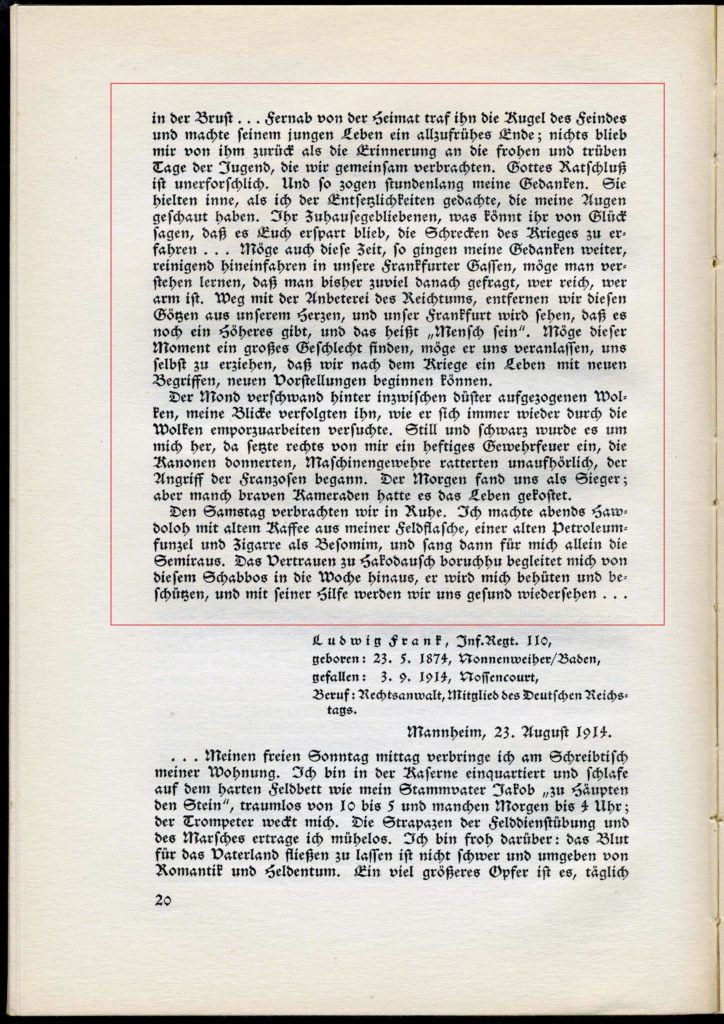

As such, it’s focused upon the central aspects of Willy’s military service, and largely (but not only) based upon what is probably the most detailed account of Willy’s life, which was written by Robert B. Gill some 33 years ago. Published in the Winter, 1984 (Volume 25, Number 4) issue of the Cross & Cockade Journal, “The Albums of Willy Rosenstein – Aviation Pioneer – Jasta Ace”, includes 65 illustrations (2), and is derived from material in Willy Rosenstein’s three photo album scrapbooks, which Mr. Gill received from Jules Loth of Johannesburg, “…who “discovered” Willy Rosenstein’s memorabilia.” As comprehensive as it is detailed, Robert Gill’s article covers Willy’s pre-war life and participation in German aviation, and concludes with a fascinating and moving account of Willy’s eventual emigration to South Africa and all-too-brief postwar life. The issue’s cover is shown below:

The list of cited references at the end of this post includes links to other sources of information about Willy Rosenstein.

The list of cited references at the end of this post includes links to other sources of information about Willy Rosenstein.

______________________________

Photographs

It helps to attach a face to a name, let alone an image to the designation of a military aircraft. So, here are representative images of Willy’s story, beginning with a picture of Willy, himself:

Willy, seated atop an Albatross D.III. This image, which appears on various websites and as a sepia-toned image in the epilogue of Nikolai Müllerschoen’s 2008 movie “The Red Baron”, appears in Robert Gill’s Cross & Cockade article. The caption: “Summer 1917 at Flugplatz Isegehem, in Flanders, with Jasta 27 as Rosenstein poses aboard his Albatross D.III, possibly 163/17.”

Willy, seated atop an Albatross D.III. This image, which appears on various websites and as a sepia-toned image in the epilogue of Nikolai Müllerschoen’s 2008 movie “The Red Baron”, appears in Robert Gill’s Cross & Cockade article. The caption: “Summer 1917 at Flugplatz Isegehem, in Flanders, with Jasta 27 as Rosenstein poses aboard his Albatross D.III, possibly 163/17.”

______________________________

Marek Mincbergr’s 1/48 model of the Pfalz E.1 (215/15) flown by Willy while an Offizier Stellvetreter (Officer Deputy) in FFA (Feldfliegerabteilung) 19. Two photographs of this aircraft, both taken in December of 1915, appear in Robert Gill’s article. One image shows Willy standing in the aircraft’s cockpit.

______________________________

______________________________

Peter Hochstrasser’s 1/72 model of the Fokker D.VII Willy flew while in Jasta 40, bearing his personal “white heart” emblem. A photo of this aircraft (perhaps the only one extant?) also appears in Bob Gill’s article, captioned thusly: “The black Fokker D.VII with der Weisse Harz (The White Heart) personal insignia of Willy Rosenstein. Carl Degelow discussed Rosenstein’s insignia in his memoirs, Germany’s Last Knight of the Air. He stated: “The remarkable choice of this pilot (Rosenstein) clearly indicated a good relationship with the eternal woman. If we had to forgive him for this, we did it gladly, for he was our ‘patron saint,’ performing for us the essential duty of keeping the rear free of our enemies, as he flew last and highest in our formation.” Rosenstein attained seven of his 10 aerial victories after joining Jasta 40 (on July 9, 1918), at least some while flying this aircraft.

______________________________

______________________________

Four Jasta 40 Fokker D.VIIs, each bearing the emblem of its pilot. The aircraft (left to right) are those of: 1) Leutnant Carl Degelow (white stag), 2) Leutnant Frodien (white eagle), 3) Leutnant Willy Rosenstein (white heart), and 4) Leutnant Hans Jeschonnek (white bull). The pilots who would have flown these aircraft were identified through Pheon Decals’ decal sheet for aircraft of Jasta 40 under Leutnant Carl Degelow. (Unfortunately, the identity of the artist (the image being present on Tumbler) is unknown.)

______________________________

______________________________

Postwar: A column from the 1928 telephone book for the post office district of Stuttgart (Amtliches Fernsprechbuch fur den Ober post direktionsbezirk Stuttgart, 1928), from Ancestry.com. This appears to have been a version of what is known as the “Yellow Pages” (if you can still find yellow pages…!); that is, a directory of names, address, and phone numbers of private businesses, retail establishments, and factories.

The entry for Willy is listed as “Fabrikant, Teilnehmer der Fabrik Lederfabrik Zuffenhausen Sihler und Cie. (Fernspech * 807 49), Eduard-Pfeiffer-Strasse 178”. (Manufacturer, Member of Zuffenhausen Sihler Leather Fabric Company (Phone Number * 807 49), 178 Eduard-Pfeiffer Street)

The entry for Willy is listed as “Fabrikant, Teilnehmer der Fabrik Lederfabrik Zuffenhausen Sihler und Cie. (Fernspech * 807 49), Eduard-Pfeiffer-Strasse 178”. (Manufacturer, Member of Zuffenhausen Sihler Leather Fabric Company (Phone Number * 807 49), 178 Eduard-Pfeiffer Street)

Though not specifically mentioned in Robert Gill’s article, this is consistent with Willy’s postwar activity in the leather manufacturing business, in which he was employed – between 1926 and 1929 – by, “the firm that manufactured the world-famous “Salamander” shoe line.”

______________________________

Historical Accounts

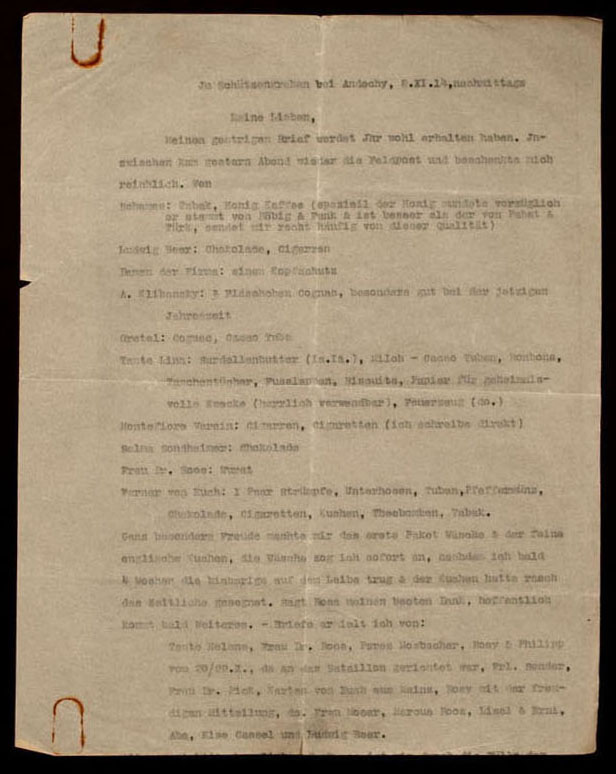

Information about Ernest Willy’s military service appeared as early as 1924, in Dr. Felix A. Theilhaber’s Jüdische Flieger im Weltkrieg, which publication was preceded in 1919 by Dr. Theilhaber’s Jüdische Flieger im Krieg. The text concerning Willy, followed by Adam M. Wait’s 1988 English-language translation, is presented below. Page numbers (from the original 1924 edition) are given in parentheses following the excerpts.

In diesem buch hat Herr Dr. Theilhaber authentisches und wohlgepruftes material zusammengetragen, das der grossen offentlichkeit zum ersten male kenntnis gibt von dem anteil der Juden an der entwicklung und nicht zuletzt an den opfern der fliegerwaffe.

Herausgegriffene beispiele nennen uns die namen der im schulbetrieb wie vor dem feinde gefallelenen. Sie alle fanden ihren tod in frieden unde krieg auf dem flugfeld der ehre. Nie hat je das gemeinsame band eine kampfgruppe inniger umschlungen und gefesselt als die flieger.

Bon diesem grossen horizont aus gesehen schrumpfen politsche, soziale und religiose gegensatze innerhalb der zunft in ein “nichts” zusammen.

Der gedanke, etwa einem der fruhesten vorkampfer im Deutschen flugwesen, Willy Rosenstein, Jablonsky oder Abramowicz, den ihnen gebuhrenden ehrenplatz nicht zu gonnen, entstammt lichtscheuen maulwurfsnaturen, aber nicht fliegerherzen. (page 6)

In this book Herr Theilhaber has compiled authentic and well-scrutinized material which for the first time gives the general public knowledge of the part played by Jews in the development of – and not least, sacrifice to – the aerial weapon.

Selected examples tell us the names of those who died in training as well as in the face of the enemy. They all found their death in peace and war on the field of honor. Never has a common bond bound a fighting force more intimately than in aviation.

Political, social, and religious differences dwindle away to nothing within the fraternity.

The idea of perhaps begrudging one of the earliest pioneers in German aviation, like Willy Rosenstein, Jablonsky or Abramowicz, the place of honor due them comes from lowly characters, but not from the hearts of aviators.

Wohl aber durfen wir den fliegerwerdegang des Willy Rosenstein, sohn der Frau Regierungsrat Dr. Nordlinger (jetzt in Stuttgart wohnhaft) etwas eingehender behandeln.

Mit 18 jahren treffen wir ihn anno 1911 als flugschuler bei Rumpler, am 3 November 1911 besteht er das pilotenexamen und wird bei Rumpler fluglehrer. Er gibt offizieren der ersten ausbildungskurfus auf den beruhmten Rumplertauben.

Der junge pilot flog bei Rumpler einige der flugwochen mit. Da er aber nur ein schulflugzeug uberwiesen bekommen hatte, erzielte er keine besonderen leistungen.

Im jahre 1913 geht er von Rumpler ab, um bei der gothaer waggonfabrik den flugzeugbau einzufuhren. Zuerst war Rosenstein vier monate bei der Zentrale Fur Aviatik in Hamburg, einem spezialunternehmen der gothaer. Dort konnte er bei dem Mecklenburger Rundflug eine gute gothaer taube fliegen, die ihm den ersten preis im gesamtklassement und den gewinn samtlicher ehrenpreise einbringt.

Nach uberfiedelung nach Gotha fliegt Rosenstein die neuen militarmaschinen ein, beteiligt sich bei den neukonstruktionen und nimmt an den abnahmeflugen anteil, sowie an der ausbildung weiterer flugschuler. Wahrend der fluglehrerzeit bildete er 80 offiziere und 40 zivilflieger aus, in Hamburg absolvierte er bereits den 2,000. Flug, in Gotha den 3,000 mit seiner mutter als passagier. Da viele fluge auf unerprobten apparaten vollfuhrt wurden, stellt diese tatigkeit nicht gerade das einfachste, was es auf der welt gab, dar.

1914 meldet er sich als kriegsfreiwilliger und kommt Januar 1915 zum Armeeflugpark V nach Montmedy, im Februar zur Feldfliegerabteilung 19 nach Porcher. Dort flog er mit Leutnant Martin als beobachter. Ein jahr spater wird er Leutnant d. R. der fliegertruppe. Im April 1916 zieht Rosenstein bei einem fernaufklarungsflug jenseits der Maas bei Verdun im kampf mit einem Franzosischen jagdflugzeug den kurzeren. Leutnant Martin erhielt einen schweren oberschenkelknochenschusss und zwei weitere steckschusse in das andere bein und wurde sosort ohnmachtig. Rosenstein hatte drei dumdumschusse in beiden beinen. Mit dem einen bein steuert er jedoch sein flugzeug nach dem flughafen, um noch glatt zu landen. Von der stelle fuhr man ihn ins lazarett. Aus der narkose aufgewacht, findet der operierte auf der bettdecke das E.K. I.

Rosenstein gesundet rascher als sein begleiter. Aber ohne ihn will er nicht mehr beobachtungsfluge ausfuhren. So wird er jagdflieger bei der armeefokkerstaffel in der Champaigne, dann bei der Jadgstaffel 27 in Flandern, bei der er seine zwei ersten abschusse erzielte.

Zur erholung zum Grenzschutz in die heimat (Karlsruhe) kommandiert, erhalt er fur einen abschuss uber Hagenau den “Zahringer Lowen”. Und wieder also gekraftigt, bittet er um ein frontkommando, wo es mehr zu tun gibt. So erscheint er bei der Jagdstaffel 40 bei Lille. Der erste frontflug lasst gleich einen Englander brennend dicht neben ihm niedergehen. Unter der weiteren fuhrung der staffel unter Leutnant Pegelow erzielt Rosenstein sechs weitere anerkannte asbchusse, wofur er zum Hohenzollern-Hausorden eingereicht wurde, dessen aushandigung die revolution verhinderte.

Mit ausnahme der knappen lazarettzeit und des zweimonatigen oben gekennziechneten heimatkommandos war Rosenstein ununterbrochen also vier jahre lang als flieger an der feindlichen front. (pages 76-77)

Now let’s deal in somewhat more detail with the flying career of Willy Rosenstein, the son of Frau privy councilor Dr. Nordlinger (now residing in Stuttgart).

We meet him in the year 1911 at 18 years of age as a flight pupil with Rumpler, with whom he became a flight instructor after passing the pilot’s exam on 3 November 1911. He gave officers their first training course on the famous Rumpler Taube.

The young pilot flew with Rumpler in some of the Flight Weeks. But since he had only been assigned a school aircraft he achieved no special performances.

In the year 1913 he left Rumpler in order to be initiated into aircraft construction with the Gothaer Waggonfabrik. First Rosenstein spent four months at the Center for Aviation in Hamburg, a special venture of Gotha. There at the Mecklenburg Round Flight he was able to fly a good Gotha Taube, which brought him first prize in general classification and the winning of all first prizes.

After emigrating to Gotha, Rosenstein test-flew the new military machines, participated in new construction, and took part in acceptance flights, as well as the training of further flight pupils. During his period as a flight instructor he trained 80 officers and 40 civilian flyers. In Hamburg he completed his 200th flight and in Gotha his 300th with his mother as passenger. Since many flights were executed on untested machines, this occupation didn’t exactly represent the easiest in the world.

In 1914 he enlisted as a wartime volunteer and in January 1915 arrived at Armeeflugpark 5 at Montmedy. In February 1915 he was assigned to Feldflieger Abteilung 19 at Porcher. There he flew with Leutnant Martin as observer. A year later he became a Leutnant der Reserve in the air service.

On 28 April 1916 during a long-range reconnaissance flight, Rosenstein drew the shorter straw in combat with a French fighter plane on the other side of the Meuse near Verdun. Leutnant Martin received a bad hit in the thigh and two further bullets in the other leg and became faint. Rosenstein had been wounded in both legs by three dum-dum bullets. However, with one leg he steered the aircraft to the aerodrome and managed to make a smooth landing. He was driven from the spot to the hospital. Upon awakening from anesthesia, the patient found on his bed cover the Iron Cross 1st Class.

Rosenstein recovered more quickly than Martin, but didn’t want to carry out any more observation flights without him. He became a fighter pilot with the Armee-Fokker-Staffel in the Champagne and then with Jagdstaffel 27 in Flanders, with whom he achieved his first two victories. [1]

Ordered to the homeland (Karlsruhe) for border protection during recuperation, he received the “Zahringer Lions” for a victory over Hagenau. Restored once more, he asked for assignment to the front, where there was more to do. Thus he appeared at Jagdstaffel 40 near Lille. [2] His first operational patrol with this unit resulted in an Englishman going down in flames close beside him. [3] Under the further leadership of the Staffel by Leutnant Degelow, Rosenstein achieved six further victories, for which he applied for the Hausordern von Hohenzollern, the delivery of which was prevented by the revolution.

With the exception of the brief time in hospital and the above-mentioned two-month home assignment, Rosestein had flown on the enemy front for four years without interruption.

***

Es sind also drei zivilpiloten der vorkriegszeit todlich verungluckt: Abramowitsch, Neufeld, Dunetz; dazu konnen noch absolut sichergestellt: Rosenstein, Jablonsky, Wechsler, zwei Dr. Lisauer, einige andere sind fraglich. Somit waren unter den 500 friedenspiloten sieben, wahrscheinlich mehr Judische piloten gewesen! (page 78)

Three Jewish civilian pilots of the pre-war era crashed fatally: Abramowicz, Neufeld, and Dunetz. Other pilots for certain in addition were Rosenstein, Wechsler, and two Dr. Lissauers. Some others are questionable. So amongst the 500 peacetime pilots there had been in fact seven, probably more, Jewish pilots.

______________________________

Mention of Willy appeared twice in Der Schild, the publication of the association of German-Jewish war veterans, the “Reichsbundes Jüdischer Frontsoldaten”. The first was in the paper’s issue of December 27, 1935, which, under the title “Makkabaer der Lufte – 200 jüdische Kriegsflieger”, presents a list of German-Jewish airmen of the First World War, within many names accompanied by the airmens’ ranks, cities or towns of residence, and for a small few – as in the case of Willy – the identity of the specific military unit(s) in which they served. The brief entry for Willy is presented below:

Der Schild

December 27, 1935

“Juden bei der Luftwaffe”

Rosenstein, Willy

Leutnant der Reserve

Armeeflugpark V

Feldfl.-Abteilung 19 u. Jagdstaffel 27 u. 40

Rosenstein, Willy

Leutnant der Reserve

Armeeflugpark V

Field Flying Unit 19 and Hunting Squadrons 27 and 40

______________________________

A subsequent article under the same title appeared in the February 7, 1936 issue of Der Schild and presented biographical profiles of several German Jewish aviators, among them Willy:

Der Schild

February 7, 1936

“Makkabaer der Lüfte”

Wurttembergische Frontflieger

Von acht fielen vier.

Aus Wurttemberg sind mindestens acht judische Frontflieger fetsgestellt worden. Vier davon sind gefallen: Lt. d.R. Pappenheimer aus Mergentheim, Zurndorfer aus Rexingen, Weil aus Ulm und Kriegsfreiwilliger Flugezugfuhrer Eugen Levi aus Stuttgart.

Aus Stuttgart sind ferner die Kameraden Hermann Schmidt, Willy Rosenstein, Lt. d.R. Wolfenstein und aus Oberdorf-Bopfingen Uffz. Flugzeugfuhrer Siegfried Heimann.

***

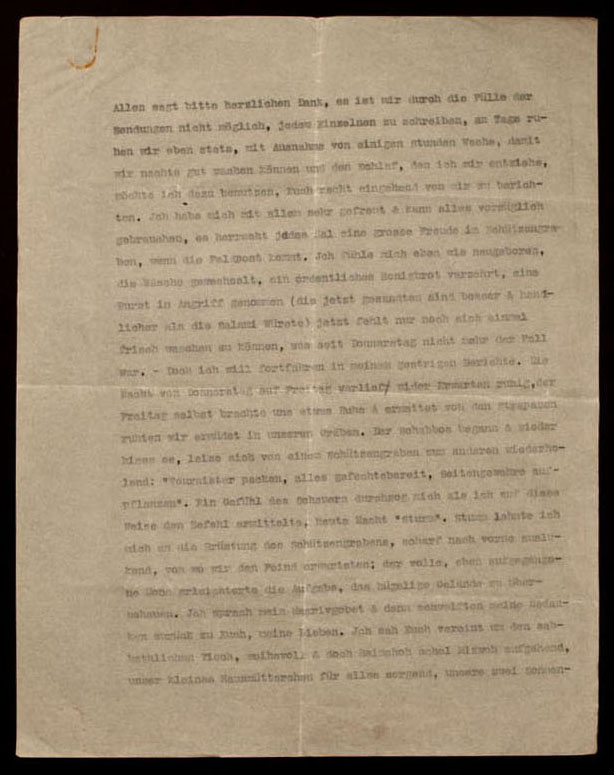

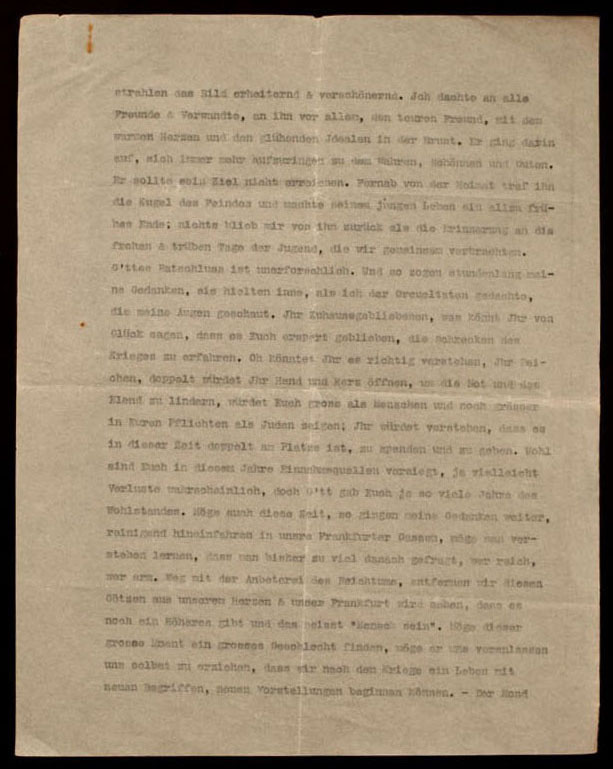

Kam. Willy Rosenstein

Zu der kleinen Zahl der Vorkriegs-piloten gehört unser Kam. Willy Rosenstein – Stuttgart. Schon mit 19 Jahren macht er im Jahre 1911 (!) sein Pilotenexamen bei Rumpler in Berlin. Als junger Pilot fliegt er einige der Flugwochen mit, freilich nur im Schulflugzeug. 1913 geht er von Rumpler ab, um bei der Gothaer Waggonfabrik den Flugzeugbau einzuführen. Zunachst ist er vier Monate bei der Zentrale für Aviatik in Hamburg, ein Spezialunternehmen der “Gothaer”. Dort konnte er bei dem Mecklenburger Rundflug eine Goather Taube fliegen, die ihm den Ersten Preis im Gesamtklassement und den Gewinn samtlicher Ehrenpreise bringt. Nach Uebersiedlung nach Gotha fliegt Kam. Rosenstein die neuen Militärmaschinen ein, ist bei den Neukonstruktionen und an den Abnahmeflügen beteiligt sowie an der Ausbildung weiterer Flugschüler. (Wir haben auf seine Vorkriegstätigkeit schon kurz in der Sonderuasgabe, “Juden bei der Luftwaffe: nom 27 12 1935 auf Seite 2 unter “Jüdische Vorkriegspiloten” hingewiesen.)

Bei Kriegsausbruch meldet sich Kam. Rosenstein sofort als Freiwilliger, muss aber zunachst weiter Offiziere als Flieger ausbilden, und fürchtet schon, nicht mehr rechtzeitig ins Feld zu kommen. Januar 1915 kommt er zum Armeeflugpark V, nach Montmedy, im Februar zur Feldflieger-Abt. 19. Gechzehn Monate flog er mit Leutnant Martin aus Stuttgart als Beobachter, bis beide eines Tages mit erheblicher Verletzung gerade noch ihren Flugpark erreichten. Es war im April 1916 bei einem Fernaufklärungsflug jenseits der Maas bei Verdun, im Kampf mit einem französichen Jadgflugzeug. Leutant Martin erhielt einen schweren Oberschenkel-Knochenschusz und zwei Steckschüsse in das andere Bein; Rosenstein hatte drei Schüsse in beiden Beinen; mit dem einen Bein steuerte er jedoch sein Flugzeug nach dem Flughafen zurück und landete glatt. Von der Stelle fuhr man ihn ins Lazarett. Aus der Narkose erwacht, findet der Operierte auf der Bettbecke das E.K. I. Inzwischen zum Leutnant d. R. befördert, flog er die verkschiedensten Typen bei mannigsachen Formationen. Eines Tages ist er bei der Jagdstaffel 27 in Flandern und vollfuhrt bald seine ersten beiden Abschüsse.

Zur Erholung zum Grenzschutz nach Karlsruhe kommandiert, erhält er für einen Abschüss über Hagenau den “Zähringer Löwen”. Bald bittet er wieder um ein Frontkommando und erschient bei der Jadgstaffel 40 bei Lille. Er bringt es im ganzen auf

neun Abschüsse

Der erfolgreiche, mutige Kampfflieger wird zum Hausorden von Hohenzollern eingereicht, – die Aushandigung wird durch den Ausbruch des Umsturzes verhindert.

***

The Shield

February 7, 1936

Maccabees of the Air

Württemberg Front Flyers

Of eight, four fell.

From Wurttemberg are found at least eight Jewish front airmen. Four of them have fallen: Lt. d.R. Pappenheimer from Mergentheim, Zurndorfer from Rexingen, Weil from Ulm and war volunteer Flugflugfuhrer Eugen Levi from Stuttgart.

From Stuttgart also are comrades Hermann Schmidt, Willy Rosenstein, Lt. d.R. Wolfenstein and from Oberdorf-Bopfingen Corporal Aircraft pilot Siegfried Heimann.

***

Comrade Willy Rosenstein

Among the small number of prewar pilots belongs our comrade Willy Rosenstein – Stuttgart. At the age of 19, in 1911 (!), he completed his pilot exam at Rumpler in Berlin. As a young pilot he flies some weeks with them, but only in a trainer airplane. In 1913 he left Rumpler to import [?] aircraft from the Gotha wagon factory. First, he spent four months with the Hamburg Aviation Office, a specialist company of “Gothaer”. There he was able to fly a Goather Taube on the Mecklenburg sightseeing flight, which gives him the first prize in the overall classification and the winning of all honorary prizes. After moving to Gotha Comrade Rosenstein is involved in flying new military aircraft, the construction of the new designs and test flights, as well as in the training of further flight schools. (We have already referred to his pre-war status in the special edition, “Jews in the Air Force: issue of December 27, 1935 on page 2, under “Jewish Pre-War Pilots”.)

At the outbreak of the war, Comrade Rosenstein reports immediately as a volunteer, but must first continue to train officers as an aviator, and is already afraid not to come into the field [of battle] in time. In January 1915 he comes to Army Flying Park V, to Montmedy; in February to Field Flying Unit 19. He flew with Leutnant Martin from Stuttgart as an observer for a total of sixteen months, until they both just managed to reach their flying park one day with considerable injury. It was in April 1916 during a remote reconnaissance flight beyond the Maas at Verdun; in the fight with a French pursuit plane Leutnant Martin received a heavy shot in the thigh bone and two shots into the other leg; Rosenstein had three bullets in both legs; but with one leg he returned his plane to the airport and landed smoothly. From the place he was taken to the hospital. Awakening from anesthesia, operated upon, he finds on the corner of the bed the Iron Cross First Class. Meanwhile promoted to Leutnant der Reserve, he flew the most diverse types in various formations. One day he is at Hunting Squadron 27 in Flanders and soon executes his first two kills.

Commanded to rest for border protection at Karlsruhe, he receives the “Zahringer Lowen” for a kill over Hagenau. Soon he asks again for a front command and appears at Jadgstaffel 40 at Lille. He gets on the whole

nine kills

The successful, courageous military pilot is submitted for the House Order of Hohenzollern, – the delivery [of the award] is prevented by the outbreak of the revolution.

______________________________

Willy Rosenstein’s Military Assignments and Awards

Robert Gill’s article identifies the units to which Willy Rosenstein was assigned, their locations, and, his military awards, which are summarized below:

Summer, 1914 – Enlisted; assigned to Infantry Regiment No. 95, Gotha

24 August 1914 – Militärische Fliegerschule-Gotha

18 October 1914 – Transferred to Flieger Ersatz Abteitung 5 at Hannover

19 October 1914 – Promoted to Unteroffizier

~ 26 October 1914 – Awarded the Flugzeugführerabzeichen (Military Pilot’s Badge)

24 November 1914 – Promoted to Vizefeldwebel and appointed Offizierstellvertreter (equivalent of Warrant Officer)

January 1915 – Ordered to Ettappen Flieger Park 5 at Montmedy

6 March 1915 – Ordered to first combat unit, Feldfliegerabteilung 19, located at Flugplatz Porcher, northwest of Mars-la-Tour

29 March 1915 – Received Iron Cross 2nd Class

21 August 1915 – Awarded Württemburg Silver Military Service Medal

28 April 1916 – Seriously wounded in action; awarded Iron Cross 1st Class

30 May 1916 – Released from hospital and sent home on reparative leave to Stuttgart

31 May 1916 – Reported to Flieger Ersatz Abteilung 10 at Böblingen

2 June 1916 – Awarded Württemburg Service Medal in Gold

17 September 1916 – Assigned to Armee Flug Park 3

19 September 1916 – Reported to Armee Fokker Staffel A.O.K. 3; redesignation of Armee Fokker Staffel A.O.K. 3 to Jasta 9 effective 7 October 1916

9 November 1916 – Ordered to Jastaschule at Valenciennes for four weeks duty as flight instructor

14 December 1916 – Returned to Jasta 9

21 January 1917 – Ordered to Reserve Officers Course for Flying Troops at Döeritz

13 February 1917 – Ordered to join newly forming Jasta 27, then forming in Flanders

10 December 1917 – Left Jasta 27 for Flieger-Beobachterschule-West

8 January 1918 – Transferred to KEST la (Kampfeinsitzerstaffel) [Home Protection Squadron] Mannheim

4 April 1918 – Transferred to Karlsruhe, joining KEST lb

2 July 1918 – Travelled to Flugplatz Lomme, near Lille, arriving on 2 July 1918. (Jasta 40)

9 July 1918 – First flight with Jasta 40

28 September 1918 – Received the Ritterkreuz zweiter Klasse mit Schwerten des Ordens vo Zaringer Löwen from Grand Duke of Baden for third victory scored over Hagenau on 26 June while with KEST lb

______________________________

Aerial Victories of Leutnant d.R. Willy Rosenstein

Willy’s aerial victories and combat claims follow. This list is supplemented by information concerning the identities (where known) of the pilots of these aircraft. The names of the Allied aviators are from Frank Bailey and Christophe Coney’s The French Air Service War Chronology 1914-1918, and, Trevor Henshaw’s The Sky Their Battlefield, which were published in 2001 and 1995, respectively; over a decade after the appearance of Robert Gill’s article in the Cross and Cockade Bulletin.

Robert Gill’s analysis of Willy’s aerial victory claims follows this list.

No. 1: 21 September 1917

D.H.4

Confirmed as the 33rd victory of Jasta 27, by Kogluft Nr. 113092 dated 11 November 1917.

Possibly a Bristol F2B Fighter of No. 22 Squadron, R.F.C. The victory occurred in the vicinity of Zillebeke Lake.

No. 2: 26 September 1917

Sopwith Single-Seater

Confirmed as the 34th victory of Jasta 27, by Kogluft Nr. 113422, dated 17 November 1917.

The victory occurred in the vicinity of Blankartsee. The enemy aircraft was seen to crash in the flood containment area of the Blankart-See following a very hard twisting and turning fight of 15 minutes duration.

Sopwith Camel B6275, No. 70 Squadron

2 Lt. C.L. Lomax, POW

Offensive patrol, seen low near Passchendaele going southeast to Lines

Left 11:05 a.m., last seen 12:15 p.m. (Henshaw, p. 232)

No. 3: 27 September 1917

Not confirmed

This claim was denied due to deficient ground confirmation. Ltn. Stoltenhoff was denied his claim on the same day, probably in the same fight. No details of aircraft type, location or time have been located.

No. 4: 26 June 1918

D.H.4

Confirmed as the 3rd victory for Rosenstein and the 2nd victory of KEST lb. Aircraft serial A8073. Crew: 2/Lt. F. Bryan, Sgt. A. Boocock, made P.O.W.s. Confirmed by Kogluft Nr. 126995 dated 11 July 1918. This victory is erroneously credited to Jasta 40, as Rosenstein had transferred as the confirmation was being made. He was awarded the Baden Order of the Zäringer Lion for this victory.

DH4 A8073, No. 55 Squadron (L.F.)

2 Lt. F.F.H. Bryan and Sgt. A/ Boocock, both POW

Bombing Karlsruhe, seen in control south of Strassburg landing field near Saverne (Henshaw, p. 345)

No. 5: 14 July 1918

S.E.5A

Confirmed as the 4th victory for Rosenstein by Kogluft Nr. 131153, dated 31 August 1918. The Jasta victory number is not included. The aircraft was most likely one belonging to either No. 64 or 85 Squadrons, R.A.F. (See Text).

SE5a C6490, No. 85 Squadron

2 Lt. N.H. (?) Marshall, POW

Offensive patrol, left 8:05 a.m., seen in combat north of Estaires at 8:35 a.m.

Claimed in combat southeast of Vieux Berquin 8:35 by Leutnant C. Degelow

Claimed in combat southeast of Vieux Berquin 8:30 by Leutnant W. Rosenstein

Claimed in combat near Berquin by 8:40 Leutnant H. Gilly (Henshaw, p. 355)

No. 6: 29 September 1918

B.F.

No record of a confirmation order for this victory can be located, although it appears in the Jasta 40 records. Rosenstein stated that “…I shot down in flames a lone flying B.F.” No data concerning time or location.

No. 7: 3 October 1918

Spad XIII

Confirmed by Kogluft Nr. 136591, dated 6 January 1919, as the 6th personal victory for Willy Rosenstein and as the 48th victory of Jasta 40. This was a French aircraft of Escadrille Spa 82, one of four enemy aircraft confirmed to Jasta 40 in the vicinity of Roulers.

Spad VII, Spa 82, over Roulers

Caporal Pilote Henri Jean Marie Francois Fourier (1/3/95, Entrevaux, France), KIA

Caporal Pilote Louis Charles Leon Rolland (2/24/95, Toulle, France), KIA

Caporal Pilote Edmond Pirolley (1/28/96, Marcilly et Dracy, France), KIA (Bailey and Cony, p. 311)

No. 8: 4 October 1918

Sopwith Camel

Confirmed by A.O.K. 4, Kofl. B, Nr. TC72154/51, dated 16 October 1918. This confirmation is unusual in that the entire combat report with original notes of confirmation by Degelow and Jeschonnek, addressed to Kogluft, are present in Rosenstein’s album. It does not appear that this paperwork ever got where it was supposed to go. Further, the personal victory tally has been obliterated and the number “8” written over whatever was there. It is placed in the position of the 8th victory in the album, apparently by Rosenstein.

No. 9: 7 October 1918

Sopwith Camel

No record of confirmation order can be found. This victory is well documented by Carl Degelow, and also in the War Diary. However, Rosenstein had placed Kogluft order for his confirmed victory of 27 October 1918 on the page for his 8th confirmed victory and then wrote that his 9th victory was not confirmed due to the end of the war.

Sopwith Camel E7176, No. 70 Squadron

2 Lt. Herbert David Lackey (formerly Royal Naval Air Service), KIA

Mrs. Elizabeth Lackey (mother), 21 Osgoode St., Ottawa, Canada

Buried at Harlebeke New British Cemetery, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium – XI,B,14

Bombing offensive patrol

Left 8 a.m., last seen near Lichtervelde

Claimed in combat at Ghent 10:30 by Leutnant C. Degelow

Claimed in combat at Ghent by Leutnant W. Rosenstein (Henshaw, p. 435)

No. 10: 27 October 1918

Sopwith Camel

Confirmed by Kogluft Nr. 137400, dated 6 January 1919, as the 7th personal victory for Rosenstein, and as the 49th victory of Jasta 40. The unit and location are not available, although Degelow’s 28th personal victory over a Sopwith Camel occurred on the same date in the vicinity of Wynghene.

Sopwith Camel E4387, No. 204 Squadron

2 Lt. Philip Frederick Cormack, KIA

Buried at Machelen French Military Cemetery, Oost-Vlaanderen, Belgium

High offensive patrol, combat with 30-40 Fokker D VIIs at Saint Denis / Westrem, south of Ghent at 9 – 10 a.m.

Claimed in combat at Wynghene by Leutnant C. Degelow

Claimed in combat at Wynghene at 9:35 a.m. by Leutnant W. Rosenstein (Henshaw, p. 445)

Analysis: The Aerial Victories of Leutnant d.R. Willy Rosenstein

While Rosenstein’s first and second victories cannot be specifically identified, he did receive solid confirmation. This was not the case with his third claim on 27 September 1917. This denied victory has never been an issue. He apparently accepted the deficient ground confirmation ruling without protest. His fourth claim on 26 June 1918, while with KEST lb, is now verified as to victim, but was always a solid third confirmed victory. His fourth confirmed victory, scored with Jasta 40 on 14 July 1918 is also a solid victory with the only debate being who shot down whom. His fifth confirmed victory on 29 September 1918 is a bit shaky – no confirmation in hand, no details of any kind as to who, where or when – but yet it appears on the Jasta 40 list as a confirmed victory for him. Did it appear on the Kogluft records as well? This writer is inclined to believe that it did for Kogluft gave him written credit on 6 January 1919 for his next victory of 3 October 1918 as his sixth personal confirmed.

His seventh claim on 4 October 1918, though well documented in his own records with original combat reports, may never have reached Kogluft for unknown reasons. In Jasta 40 records it is listed as his seventh confirmed. His eighth claim on 7 October 1918 is not supported by written confirmation in his records by Kogluft documentation, although on that day, apparently following the action, Degelow nominated him for the Hohenzollern Haus-orden, stating that he had eight confirmed victories. His ninth, which he shrugged off as not being confirmed due to the end of the war was, in fact, confirmed by Kogluft as his seventh personal victory – and as the 49th victory of Jasta 40. This is the number of official confirmed victories he is usually credited with in most accounts. So, it appears that Rosenstein was victorious on 4 and 7 October 1918, and that these victories were not included in his tally at Kogluft. Therefore, this writer submits to those interested that Willy Rosenstein should have received credit for at least nine confirmed victories, plus one not confirmed moving him from position 240 to new position 183 on the Ace List of German aviators in World War I.

______________________________

History does not end: The past becomes the present.

Nearly a century had passed, and then, Willy Rosenstein once more appeared before the public. Well, to be specific, an image of Willy appeared before the public.

This occurred within Nikolai Müllerschoen’s above-mentioned, movie “The Red Baron”, the epilogue of which reveals the ultimate fates of the film’s protagonists: Manfred von Richtofen, Nurse Käte Otersdorf (about whom “No further records exist on her remaining life”), Captain Roy Brown, Manfred’s brother Lothar and cousin Wolfram, Werner Voss, and, Kurt Wolff. Regardless of the film’s historical inaccuracy and contrived plot (!), all these characters are solidly historical individuals. Obviously, they existed.

But…

…the epilogue includes another central character, who – in a film already largely and deliberately ahistorical in its presentation of events (true, the CGI depictions of aerial combat were superbly done, the aerial action having been depicted in the abrupt, “hand held” style so characteristic of contemporary films) – is revealed to the viewer to be completely fictional.

Who?

The Jewish pilot: Friedrich Sternberg. Tellingly, while the epilogue presents photographic images of the above-mentioned aviators, as well as Käte Otersdorf, Sternberg is not represented with the image of actor who played him, Maxim Mehmet. Rather; strikingly, the viewer is presented with the image – the same image at the “top” of this post – of Willy Rosenstein seated upon the fuselage of his black Albatross. This sepia-toned photo is accompanied by the following text:

DURING WW I MANY JEWISH PILOTS FOUGHT

FOR THE GERMAN EMPIRE.

MANY OF THEM WERE HIGHLY DECORATED

FIGHTER ACES.

THEY ARE REPRESENTED

BY THE FICTITIOUS CHARACTER OF

FRIEDRICH STERNBERG

You can view this “snippet” from the movie (the full film, uploaded by teo7121941, is available here) below:

This following sequence, which appears immediately after the movie’s opening scene (showing the childhood incident which allegedly inspired Manfred von Richtofen to become an aviator – well, hey, it makes a nice story) portrays von Richtofen leading a trio of pilots, as the group salutes – literally and symbolically – a fallen British aviator. Note that while the camera fleetingly captures – very quickly! – the personal insignia on all four Albatross fighters, the very first insignia to be shown is a Magen David on Sternberg’s aircraft.

The next two clips are fraught. Very, highly, fraught. They depict Sternberg and his comrades engaged in aerial combat with British bombers and fighters near Ypres. And then, Sternberg is shot down and killed.

In terms of Sternberg’s ultimate fate, let alone a bevy of minor and fleeting details which are not at all that minor (the Magen David upon Sternberg’s black Albatross, the fuselage of which is dotted with stars; the Hebrew characters painted upon the horizontal elevator of his plane; the revelation that Sternberg had been awarded the Pour le Mérite) this entire sequence is deeply symbolic and intentionally so, and in terms of actual history, more than a little ironic.

This kind of symbolism has been manifest in other military-themed movies and literary works featuring Jewish characters. A few examples: Sands of Iwo Jima; Objective Burma; Destination Tokyo (where the role of “Tin Can”, played by Dane Clark [Bernard Elliot Zanville], merits a blog post unto itself!); Steven Spielberg’s over-rated (like the bulk of his oeuvre, but I’ll leave that for another discussion…) Saving Private Ryan; Enemy at The Gates; James Jomes’ superb The Thin Red Line; Norman Mailer’s The Naked and The Dead; MacKinlay Kantor’s extraordinary Andersonville.

But, I digress. Perhaps I’ll save that topic for a future blog post. (Posts? There is lots of material there…)

*

* * *

* * * * * * *

* * *

*

Robert Gill’s article concludes with a single paragraph about Willy’s son, Ernest Willy. In its starkly enigmatic brevity this account stands in striking contrast to the information available about his father:

“The final irony was yet to come. His son, Ernest Willy, enlisted in the South African Air Force when he was 19 year of age. Following in his father’s footsteps, he became a fighter pilot. He was seconded to the Royal Air Force and assigned to No. 185 Squadron in Italy. While flying a Spitfire, this expatriot, German-born Jew was posted Missing in Action, later confirmed Killed in Action, on 2 April 1945, flying against his former countrymen. (3) He was 22 years of age. This writer has attempted, without success, to obtain the details concerning the young Ernest’s combat record and his last mission.”

Robert Gill was correct. This was the embodiment of irony; a deep and powerful irony. But, it was even more than mere irony – as seen in conventional terms. This was “unfair”, solidly unfair. But, it was far more than simple unfairness – as in everyday life. Rather, it seemed to be unjust, at an almost inexpressible, if not poetic level.

I became curious about this, and contacted Robert Gill for information about Ernest Willy. He replied rapidly, favorably, and with great generousity, providing me with photocopies of Ernest Willy’s Log Book, photographs, Attestation Papers, and related documents.

That material – which has been the impetus for “this” post, about the father – has become the basis of the “next” post, about the son…

______________________________

References

First and foremost, my sincere and deep thanks to Robert B. Gill, for providing me with material about Ernest Willy Rosenstein, and, for his research into the life of Willy Rosenstein.

______________________________

Willy Rosenstein (General)

Biography of Willy Rosenstein (at Wikipedia)

Genealogy of Willy Rosenstein, by Alex Calzareth (at geni)

Genealogy of Willy Rosenstein, by Rolf Hofmann (“Family Sheet Willy Rosenstein of Stuttgart + South Africa”) (at Alemannia Judaica)

Willy Rosenstein as pilot and racing car driver (“Karriere als Pilot und Autorennfahrer”) (at Wikiwand)

German Jewish Aces (at Militarian Military History Forum)

Willy Rosenstein in his Hansa Taub (postcard) (at ansichtskarten-center)

Matzeva of Willy Rosenstein (at Jewish Photo Library)

Cross & Cockade Journal, Winter 1984 (at Flying Tiger Antiques)

Willy Rosenstein (Aerial Victories)

List of aerial victories (at The Aerodrome)

Discussion of aerial victories (at The Aerodrome)

Willy Rosenstein (Aircraft)

Willy Rosenstein’s Pfalz E.1 (Marek Mincbergr)

Willy Rosenstein’s Fokker D.VII (at Modellversium)

Jasta 40’s Fokker D.VIIs

Pheon Decals – Decal Set 48005: Jasta 40 under Degelow (at Pheon Decals)

The Red Baron (Movie)

The Red Baron (at Internet Movie Database)

The Red Baron (at Wikipedia)

The Red Baron (at Rotten Tomatoes) – Tomatometer currently stands at 20%

The Red Baron (Discussion at A.E. Larsen’s blog)

Other References

World War One Luftstreitkraefte (at Wikipedia)

Jewish Knights of the Air (German Jewish aviators in the First World War) (at Dayton Holocaust Resource Center)

Kurt Katzenstein (at Wikiwand)

Keeping Faith: A Letter from an Orthodox Jewish Soldiers in the Germany Army During the Great War (at They Were Soldiers)

Books

Bailey, Frank W., and Coney, Christophe, The French Air Service War Chronology 1914-1918 – Day-to-Day Claims and Losses by French Fighter, Bomber and Two-Seat Pilots on the Western Front, Grub Street, London, 2001

Henshaw, Trevor, The Sky Their Battlefield: Air Fighting and The Complete List of Allied Air Casualties From Enemy Action in the First War (British, Commonwealth, and United States Air Services 1914 to 1918), Grub Street, London, 1995

Theilahber, Felix, Jüdische Flieger im Weltkrieg, 1924, Verlag der Schild, Berlin.

Wait, Adam M., Jewish Flyers in the World War, Original Title “Judische Flieger im Weltktrieg” – English-Language Translation, Adam M. Wait, 1988.

Notes

(1) Rolf Hofmann lists his birthplace as Wiesbaden.

(2) 55 photographs and 10 documents.

(3) Whether Ernest Willy would have been perceived as a fellow countryman – in 1945, let alone 2018 – remains open to conjecture.