History does not end: It persists.

An ongoing aspect of this blog has been the presentation of information about American Jewish WW II military casualties in the context of news items about Jewish servicemen that appeared in The New York Times between 1941 and 1945. As such, I’ve created and organized such posts in the simplest manner possible – alphabetically, by the soldier’s surname – the posts thus far encompassing servicemen whose surnames began with the letters “A” through “J”.

This information emerged from my research into identifying relevant articles and news items found by manually scrolling through every issue of The New York Times published between 1941 and 1946, on 35mm microfilm. (Microfilm, you ask? Well, this was a few years ago.)

I focused on Times because I initially assumed that the combination of the newspaper’s status, scope of news coverage, and especially its geographic setting in the New York metropolitan area (sort of the symbolic and demographic center of American Jewish life) would have resulted in its featuring information about the role of American Jewish soldiers to a greater degree than other national publications, and this specifically in the context of the Second World War having been – even if it was unrecognized, denied, or ignored at the time – parallel battles for the survival of the Jewish people, and, the Allied nations.

In the process, I discovered I was half right.

Certainly the paper featured many, many (many) such items, as well as – alas, inevitably – many obituaries (particularly from 1944 through 1946) for Jewish soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen who lost their lives in the conflict.

In the same process, I learned I was half wrong.

I was soon disabused of my assumptions about the Times’ coverage of Jewish military service, for Jewish participation in the war never seemed to have been perceived or recognized as such by the newspaper, to begin with. Every article, news item, and (yes, too) obituary about or alluding to Jewish servicemen was absent of any mention of the war’s ideological underpinnings – at least in the European Theater – and its implications in terms of the collective survival of the Jewish people. Then again, among WW II issues of other American newspapers I’ve reviewed (not as thoroughly as the Times, but deeply enough), I found this to have been equally so, and really no differently perceived by Jewish newspapers, as well.

Here’s how this subject was approached by The Jewish Exponent in its issue of August 4, 1944, in which the newspaper began to specifically focus on coverage of the military service of Jewish soldiers from the Philadelphia metropolitan area. In light of the era, that the Exponent attempted to cover this topic in a comprehensive manner to begin with, stands to its credit.

The text of this article follows below. I’ve italicized some key passages….

Our Sons and Daughters In the Armed Forces

Our Sons and Daughters In the Armed Forces

The Day-to-Day Story of Their Valor and Heroism

Please Note

We want to tell the entire community about the heroism, sacrifices and contributions of our Jewish men and women of Philadelphia serving in the armed forces at home and abroad. Mail letters, photographs, citations, communications from the War Department and other items of interest about your son or daughter, husband, relative or friend in the service to the Jewish Exponent, Widener Building, Philadelphia, 7, Pa.

All such data will be documented by the Jewish Welfare Board, and within the uncontrollable limitations of space, will be published in these columns each week.

Today, thousands of Philadelphia’s sons and daughters of Jewish faith are making an imperishable record of American heroism and sacrifice, following in the tradition of their fathers who served with courage, loyalty and devotion in every crisis that has confronted our Nation – a glorious tradition that began with Chyam Solomon and reaffirmed with Meyer Levin.

To them, we respectfully dedicate these columns. Not merely to show the undying patriotism of the Jews of Philadelphia, but that in doing so they are emphasizing their Americanism and the inestimable value of this great country’s heritage of racial and religious freedom.

KILLED IN ACTION

Until entering the service in October, 1942, Private Wallace Jay Epstein, 5034 “D” St., was associated with his father’s business, the Regal Corrugated Box Co. Since March, 1943, he served overseas, and earlier this month, his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Abraham Epstein, were notified that their 19-year-old son died of wounds in France.

Also entering service in October, 1942, was Private First Class Morris Cherry, 100 East Meehan Street, in Germantown. A well-known amateur photographer, he was sent overseas last February. His parents, Mr. and Mrs. B. Cherry, were informed by the War Department that he was killed in France.

Killed in action in France was 10-year-old Private Harold G. Miltenberger, 2208 Bainbridge Street, who first took up arms in September, 1943, and went overseas in April.

WEST POINT GRADUATE

The youngest member of his graduating class at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in June, 1943, Lieutenant Colonel Paul H. Berkowitz, 31, son of Mr. and Mrs. William F. Berkowitz of 434 West Ellett Street, Mt. Airy, has been reported missing since July 26 in the Southwest Pacific area while returning to his base in Australia from a mission in this country.

Nine months after his marriage to the former Jeanne Grandy, of Portland, Me., in April, 1942, he went overseas to command a topographical battalion of Army engineers. He did not return to this country until last June on a mission from the Pacific, where his wife joined him on the West Coast to mark their third wedding anniversary, the first they had been able to celebrate.

His sister, Sylvia, is the husband [sic] of Major Charles S. Morrow, Newark, N.J., heart specialist, serving with the Medical Corps in Panama.

Also “missing in action” is First Class Seaman Raphael Weinstein, 18-year-old hospital attendant, of 621 Parrish Street. A Graduate of Northeast High School, he has a brother, Corporal Joseph, 21 years old, serving in the Army.

FLAME OF HOPE

This is the story of the type of faith to which thousands of parents of sons reported killed or missing in action are clinging. Ordinarily, Samuel Gross and his wife, Freda, 3026 West Susquehanna Avenue, place little credence in “second-hand news”. But a bit of “second-hand news” relayed to them over thousands of miles has kept their spirits buoyed up since July 17.

It was back in January that they received word their 22-year-old son, Technical Sergeant Joseph Gross, was missing in action over France, when the Flying Fortress on which he was a gunner and radio operator was shot down, over Bordeaux. But the flame of hope for their son, one of two in the armed forces, burned feebly.

Then a letter received from the mother of Lt. James Bradley, of Lido, N.M., fanned the flame of hope into a burning conviction that their son was alive. She revealed that she had received a letter from a French woman who told how her son and three other members of the crew of the plane, including Gross, had been picked up by a Frenchman, hidden and smuggled out of France. An then the other day a cable from Sgt. Gross to his parents. It read: “All well and safe.”

Sgt. Gross, an honor graduate of West Philadelphia High School, class of 1939, joined the Air Force in September, 1942. His 18-year-old brother, Morris, is an aviation cadet at San Antonio, Tex., and his wife, Martha, 21, lives at 5405 Walnut Street.

The same flame of hope now burns brightly for Mrs. Rae W. Fleishman, 4600 North Marvine Street, who was officially notified this week that her 20-year-old son, Second Lieutenant Milton H. Fleishman, a navigator on a B-24, who was missing over France, is safe. He has two other brothers in the service, William, a signalman in the Navy, and Leon, a sergeant in the Army Transport Command.

Reported missing in June, Mr. and Mrs. S. Finkelstein, 5814 Montrose Street, were informed this week by the War Department that their 19-year-old son, Private Morris M. Finkelstein, is a prisoner of the German government. A brother, Alex F., is also an Army private.

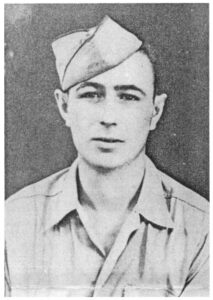

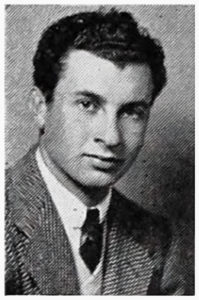

(Portrait of Morris M. (Martin) Finkelstein, from the Honoree Page at the WW II Memorial created in his honor by his daughter. A member of H Company, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, he was captured on D-Day, and spent the remainder of the war at Stalag 4B (Muhlberg). The son of Samuel and Mollie Finkelstein, his name never appeared in American Jews in World War II.)

(Portrait of Morris M. (Martin) Finkelstein, from the Honoree Page at the WW II Memorial created in his honor by his daughter. A member of H Company, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, he was captured on D-Day, and spent the remainder of the war at Stalag 4B (Muhlberg). The son of Samuel and Mollie Finkelstein, his name never appeared in American Jews in World War II.)

THE MARINES ARE IN

The largest group of First Division Marines to be returned from combat duty in the South Pacific landed by transport at San Diego. These were all men from the famous First Division, that fighting group which started America’s offensive against the Japs on August 7, 1942. Among this group was Private First Class Martin S. Rothstein, 24 years of age, husband of Megan Rothstein and son of Mr. and Mrs. Samnuel Rothstein, 6116 Castor Avenue.

WITH THE LADIES

The welcome mat is getting a special dusting at 4550 “D” Street, where Mr. and Mrs. Harry Applebaum are eagerly awaiting the homecoming this week of Corporal Zelda Applenbaum, her first furlough since joining the U.S. Women’s Marine Corps 17 months ago, and stationed at San Francisco. Zelda’s sister, Apprentice Seaman Betty B. Applebaum, is in the WAVES, stationed at Hunters College, New York.

Proud parents are Mr. and Mrs. Nathan Lazar, 424 Tree Street, whose daughter, Seaman First Class Bettye Lazar, graduated this week from the WAVES Naval Training School at Stillwater, Okla.

WOUNDED IN ACTION

Private Gilbert B. Shapiro, 24, husband of Mrs. Claire B. Shapiro, 3864 Poplar Street, was wounded in France. An infantryman, he attended Overbrook and Central High Schools and worked in the fur business until joining the service in October, 1942. He has been overseas since last January. A brother, Milton, is a captain in the Army.

Private Irving I. Bleiman, 17, son of Harry B. Bleiman, 494 North 3rd Street, was wounded on Saipan Island in the Pacific while fighting with the Marine Corps.

Staff Sergeant Morris Krivitsky, husband of Mrs. Charlotte Krivitsky, 5009 “B” Street, was reported wounded in action.

Technical Sergeant Arnold Miller, son of Mrs. Fannie Miller, 2518 South Marshall Street, in the European Theatre.

Private Armand F. Eiseman, son of Mrs. Rose Weiss, 1594 North 52nd Street, in the European theatre.

Private Herman S. Hershman, 19, son of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Hershman, 4515 North 13th Street, was wounded in France.

Private David Polnerow, son of Mr. and Mrs. Morris Polnerow, 4822 North 9th Street, is recuperating in a hospital in England from wounds received in action in France.

Private Aaron Leibowitz, 5383 Columbia Avenue, was wounded in France, his brother Philip was notified.

Private Alexander Glick, 33, husband of Mrs. Lena Glick, 524 South 60th Street, in the European theatre. Before joining the Army in April, 1943, he worked as a salesman, and went overseas last November.

Staff Sergeant Martin Glickman, son of Boris Glickman, 7919 Harley Avenue.

________________________________________

Anyway, regarding the Times, only over time (accidental pun…) did I arrive at an appreciation of the evolution and ideological orientation of the newspaper, in terms of the collective identity and survival of the Jewish people as a people (not merely a religious group). This was through such works as Laurel Leff’s Buried By the Times, which revealed how strongly the Times’ ethos influenced wartime coverage of the Shoah by the news media, in general. Does this perhaps irrevocably ingrained attitude continue to animate that newspaper’s news reporting concerning the Jewish people and especially the nation-state of Israel? Well,…

Not merely a sign of the Times, but an ongoing sign of our “times”…

________________________________________

In any event, my first post about this topic appeared on April 30, 2017 and pertained to Navy Hospital Apprentice First Class Stuart Adler, who was killed on Okinawa on March 15, 1945.

The post was limited in scope, only covering Jewish naval personnel and Marines who were casualties on that March day. Nearly three years having passed since April of 2017, I thought it worthwhile to revisit the post to correct a few inaccuracies, and of far greater importance, add records about some of that day’s other Jewish military casualties.

As a result, the post is now a little longer than it was three years ago.

________________________________________

Finally, more than a little “off-topic” but very much “on time” (that is, time past): An artifact from March of 1945: That month’s issue of Astounding Science Fiction…

And herewith, back to the post…

And herewith, back to the post…

________________________________________

________________________________________

Notice about Hospital Apprentice Stuart Emanuel Adler (7124266) appeared in a Casualty List published in The New York Times on May 17, 1945. Stuart was attached to the 1st Marine Battalion, 21st Marine Regiment, 3rd Marine Division when he was killed on Iwo Jima by a sniper, while attempting to render medical aid to a wounded Marine. Born on May 2, 1926, he is buried at the Washington Cemetery in Brooklyn, N.Y. (Chevra Anshe Ragole, Section 4, Post 440)

His obituary, transcribed below, was published on August 9, 1945.

__________

Slain Hospital Apprentice Honored by His Comrades

Hospital Apprentice Stuart Adler, 18 years old, who was killed on March 15 on Iwo Island by a Japanese sniper’s bullet, has been honored by his comrades, who have named a company street on Iwo in his memory.

In a recent letter to his mother, Mrs. Betty Lee Adler of 245 East Gunhill Road, Maj. Gen. G.B. Erskine, Marine Corps, praised the youth’s “devotion to duty”.

Enlisting in the Navy on Feb. 8, 1944, shortly after his graduation from DeWitt Clinton High School, he was attached to the First Battalion, Twenty-First Marines, during the Iwo Campaign. He was killed when he went to the aid of a wounded marine.

A younger brother, Robert; a sister, Faith, and his father, David Adler, also survive.

These are contemporary (2010-ish) views – from apartments.com – of the Adler family’s wartime residence: 245 East Gunhill Road, in the Bronx.

These are contemporary (2010-ish) views – from apartments.com – of the Adler family’s wartime residence: 245 East Gunhill Road, in the Bronx.

________________________________________

________________________________________

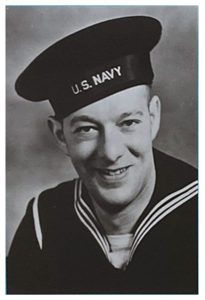

Saperstein, Charles (Yekutiel ben Hayyim), MoMM1C, 6425696, Motor Machinist’s Mate

Born 1921

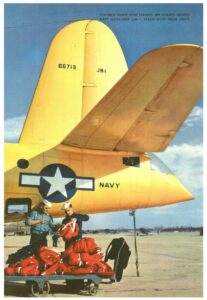

United States Navy, Probably crew member of LCT(6) – #36

Mr. Herman Saperstein (father), 32 Lakeview Drive, Silvermine, Norwalk, Ct.

Memorialized on Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery, Manila, Philippines

Memorial matzeva at Beth Israel Cemetery, Norwalk, Ct.

Casualty List 5/27/45

American Jews in World War II – 69

Finkelstein, Albert Jacob, HA1C, 7109973, Hospital Apprentice

United States Navy, 5th Marine Division, 31st Replacement Battalion (attached)

Mr. Samuel Finkelstein (father), 1445 Saint Marks Ave., Brooklyn, N.Y.

Place of burial unknown

Casualty List 6/30/45

American Jews in World War II – not listed

Photograph via ShaneO

Photograph via ShaneO

Wounded in Action

Percoff, Manuel, PFC, 884682

United States Marine Corps, 5th Marine Division, 28th Marine Regiment, 2nd Battalion, Headquarters Company

Mr. Sam Percoff (father), Laurel, Mississippi

Casualty List 6/6/45

American Jews in World War II – 206

Swarts, John Leonard, Cpl. 863329

United States Marine Corps, 2nd Armored Amphibious Division, C Company

Mrs. Rosalind M. Swarts (wife), 225 West End Ave., New York, N.Y.

Born New York, N.Y. 1/14/12, Died 8/17/03

American Jews in World War II – 459

________________________________________

Some other Jewish military casualties on Thursday, March 15, 1945 (1 Nisan 5705) include…

Killed in Action

– .ת.נ.צ.ב.ה. –

United States Army (Ground Forces)

Amira, Ralph (“Robert”?), S/Sgt., 32398826, Silver Star, Purple Heart

11th Airborne Division, 188th Glider Infantry Regiment, B Company

Mr. and Mrs. Isaac Becky (Rebecca?) Amira (parents), 1920 24th Ave., Astoria, Long Island, N.Y.

Mount Hebron Cemetery, Flushing, N.Y. – (Possibly Block 12, Reference 3, Section A, Line E/F, Grave 12, Society Life & Charity / Source of Life); Buried 4/12/49

Casualty List 4/14/45

Long Island Star Journal 9/23/48

American Jews in World War II – 265

Auerbach, Robert, PFC, 12219224, Infantry, Purple Heart, 1 Oak Leaf Cluster

(Wounded previously, on 12/3/44)

103rd Infantry Division, 410th Infantry Regiment, K Company

Born 1924

Mrs. Mildred Auerbach (mother), 1132 Fulton St., Woodmere, N.Y.

Long Island National Cemetery, Farmingdale, N.Y. – Section J, Grave 16229

Casualty List 4/10/45

American Jews in World War II – 267

Bass, Solomon, M/Sgt., 6667553, Infantry

United States Army, 45th Infantry Division, 157th Infantry Regiment

Born 1922

Mrs. Adelle Bass (wife), 916 Parkwood Drive, Cleveland, Oh.

Pvt. Jack Bass and Mrs. Ann Falcone (brother and sister)

Zachary Taylor National Cemetery, Louisville, Ky. – Section I, Grave 231

Cleveland Press & Plain Dealer 9/10/45

American Jews in World War II – Not Listed

________________________________________

Bernstein, Louis (Levi bar Levi), PFC, 32876996, Infantry, Purple Heart, 1 Oak Leaf Cluster

3rd Infantry Division, 30th Infantry Regiment

(Wounded previously, around 2/25/44 and 10/20/44)

Born 1910

Mrs. Beatrice Bernstein (wife), 1163 President St., Brooklyn, N.Y.

Beth David Cemetery, Elmont, N.Y.

Casualty Lists 3/25/44, 12/20/44, and 4/10/45

American Jews in World War II – 276

Photograph of matzeva by Lainie Cat

Photograph of matzeva by Lainie Cat

________________________________________

Cantor, Alvin D., PFC, 42108329, Infantry, Purple Heart

100th Infantry Division, 397th Infantry Regiment

39 North Park Ave., Buffalo, N.Y.

Lorraine American Cemetery, St. Avold, France – Plot B, Row 18, Grave 56

Buffalo Courier-Express 12/31/44, 5/8/45

American Jews in World War II – 287

________________________________________

Cohn, Jack B. (Yakov Benymain bar David Haayim), PFC, 32923274, Infantry, Purple Heart, on Luzon Island, Philippines

25th Infantry Division, 161st Infantry Regiment

Born 2/19/23

Mrs. Anna Cohn (mother), New Brunswick, N.J.

Poile Zedek Cemetery, New Brunswick, N.J.

Casualty List 5/5/45

American Jews in World War II – 230

Photograph of matzeva by F Priam

Photograph of matzeva by F Priam

________________________________________

Cohn, Jack L., T/5, 37604995, Signal Corps, Purple Heart

103rd Infantry Division, 103rd Signal Company

Born 1913

Mrs. Ida Cohn (mother), 5883 Maffitt Ave., St. Louis, Mo.

Chevra Kadisha Adas B’Nai Israel Vyeshurun, University City, St. Louis, Mo.

Saint Louis Post Dispatch 3/28/45 and 3/29/45

American Jews in World War II – 208

Drucker, Simon, PFC, 32882827, Infantry, Purple Heart

3rd Infantry Division, 7th Infantry Regiment, Headquarters Company, 3rd Battalion

Born 3/30/20

Mrs. Fanny Drucker (mother) and Mr. Morris Drucker (brother), 721 Van Sicklen Ave., Brooklyn, N.Y.

Mount Hebron Cemetery, Flushing, N.Y. – Block 25, Reference 12, Section I, Line 6, Grave 14, Society 1st Toporower S&B

Casualty List 4/14/45

American Jews in World War II – 299

Farash, Solomon, Pvt., 32420791, Infantry, Purple Heart

36th Infantry Division, 142nd Infantry Regiment, Headquarters Company

Born 1921

Mr. Hyman Farash (father), 250 New Lots Ave., Brooklyn, N.Y.

Also Pittsburgh, Pa.

Cemetery unknown

Casualty List 4/14/45

American Jews in World War II – 305

Finer, Morris L., 2 Lt., 0-2005368, Infantry, Purple Heart

99th Infantry Division, 393rd Infantry Regiment

Born 1920

Mr. Miller Finer (father), Greene and Johnson Streets, Philadelphia, Pa.

Mount Sinai Cemetery, Philadelphia, Pa.

The Jewish Exponent 4/20/45

The Philadelphia Record 4/12/45

American Jews in World War II – 520

________________________________________

Fleck, Jack (Yakov bar Pesach HaLevi), Cpl., 35510000, Purple Heart, in Germany

290th Field Artillery Observation Battalion

Born Youngtown, Oh., 7/7/22

Mr. and Mrs. Peter and Getrude (Sachs) Fleck (parents), 741 Kenilworth SE, Niles, Oh.

Also Warren, Oh.

Bernard and Irwin (brothers), Mrs. M. Reisman (sister)

Ohio State University Class of 1945

Beth Israel Cemetery, Warren, Oh.; Buried 11/19/47

Warren Tribune Chronicle 11/17/47

American Jews in World War II – 486

This is Corporal Fleck’s obituary from the Warren Tribune Chronicle of November 17, 1947, provided by FindAGrave contributor Rick Nelson.

________________________________________

________________________________________

Geller, Seymour L., 2 Lt., 0-1329107, Infantry, Purple Heart

36th Infantry Division, 142nd Infantry Regiment, F Company

Born 1921

Mrs. Seymour L. Geller (wife), c/o H. Cohen, 85 McClellan St., Bronx, N.Y.

Also 1727 Walton Ave., New York, N.Y.

Cemetery unknown

Casualty List 4/14/45

The New York Times – Obituary Page (In Memoriam Section) 3/15/46

American Jews in World War II – 319

Gold, Louis, Pvt., 16185802, Infantry, Purple Heart

36th Infantry Division, 142nd Infantry Regiment, G Company

Mr. Charles Gold (father), 6632 South Troy St., Chicago, Il.

Lorraine American Cemetery, St. Avold, France – Plot K, Row 14, Grave 10

Casualty List 6/10/45

American Jews in World War II – 100

Horowitz, Bernard L., 2 Lt., 0-534380, Bronze Star Medal, 2 Oak Leaf Clusters, Purple Heart

9th Infantry Division, 746th Tank Battalion

(Wounded previously, around 12/16/44 and 1/15/45)

Born 2/8/23

Mr. Isaac M. Horowitz (father), 2-12 Sickles St., New York, N.Y.

Mr. Gilbert Horowitz (?), 1155 Walton Ave., c/o Kessler, Bronx, N.Y.

City College of New York Class of 1943

Cedar Park Cemetery, New York, N.Y.

Casualty Lists 2/28/45 and 4/12/45

American Jews in World War II – 348

Klein, Bernard, PFC, 32249842, Infantry, Purple Heart

3rd Infantry Division, 7th Infantry Regiment

Born 3/6/15

Bronx, N.Y.

Long Island National Cemetery, Farmingdale, N.Y. – Section J, Grave 15567

American Jews in World War II – 363

________________________________________

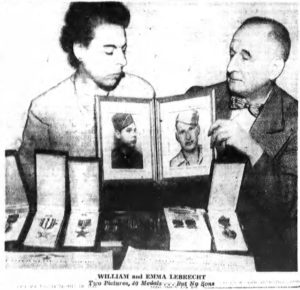

Lebrecht, Alfred W., PFC, 32897544, Infantry, Purple Heart

3rd Infantry Division, 15th Infantry Regiment

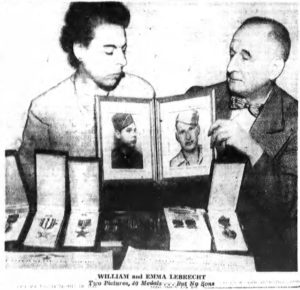

Mr. and Mrs. William and Emma F. Lebrecht (parents), 920 Riverside Drive, New York, N.Y.

Lorraine American Cemetery, St. Avold, France – Plot B, Row 31, Grave 13

Casualty List 4/17/45

New York Post 1/21/51

Jewish Criterion (Pittsburgh) 9/20/46 – “Double Gold Stars”, by Helen Kantzler

American Jews in World War II – 373

Photograph of Alfred’s matzeva by Marc Burba

Photograph of Alfred’s matzeva by Marc Burba

Among the many families who lost multiple sons during the war – profiled in Helen Kantzler’s 1946 Jewish Criterion article “Double Gold Stars” – was that of William and Emma Lebrecht, German refugees who arrived in the United States in 1939. Alfred’s older brother Ferdinand was killed on February 20, 1945, while serving in the 10th Mountain Division.

The brothers (Alfred’s matzeva shown above and Ferdinand’s below) are buried adjacent to one another at the Lorraine American Cemetery in Saint Avold, France.

Lebrecht, Ferdinand, PFC, 32695706, Bronze Star Medal, Silver Star, Purple Heart

10th Mountain Division, 85th Mountain Infantry Regiment, L Company

KIA 2/20/45

Lorraine American Cemetery, St. Avold, France – Plot B, Row 31, Grave 14

Jewish Criterion (Pittsburgh) 9/20/46 – “Double Gold Stars”, by Helen Kantzler

New York Post 1/19/51, 1/21/51

American Jews in World War II – 573

Casualty List 3/20/45

Lorraine American Cemetery, St. Avold, France – Plot B, Row 31, Grave 14

Photograph of Ferdinand’s matzeva by Marc Burba

Photograph of Ferdinand’s matzeva by Marc Burba

The incident in which Ferdinand was killed in action is described at Next Exit History:

18 Feb 45 • On the evening of the 18th, 700 men of the 86th Regiment make a daring night climb and successful assault on Riva Ridge, which rises steeply 1700-2000 feet above the rushing Dardagna River. Using five carefully prepared climbing routes, including two that require fixed ropes, the attack takes the enemy by complete surprise.

American casualties result from fierce counterattacks that occur over the next four days. For their heroism on Riva Ridge, three soldiers receive Silver Stars posthumously:

Pvt. Michael G. Bostonia (33938591, Washington County, Pa.)

Pfc. Ferdinand Lebrecht, and

1st Lt. John A. McCown II (0-1305285, Philadelphia, Pa.)

Eight other Silver Stars are awarded to: Pfc. Jack A. Booh [?], Pfc. Franklyn C. Fairweather, 1st Lt. Frank D. Gorham, Jr., 2nd Lt. Floyd P. Hallett, Lt. Col. Henry J. Hampton, 1st Lt. James W. Loose, Jr., Pfc. Roy Steen, and S/Sgt. Robert P. Thompson.

Two days later, engineers from D. Company of the 126th Engineers complete an aerial tramway to a point near the top of one of Riva’s peaks, Mt. Cappel Buso. On the first day of operation, 30 wounded are evacuated and 5 tons of supplies delivered.

Just before midnight, without artillery preparation, five other battalions of the 10th Mountain Division begin their attack of Mt. Belvedere and its sister peak, Mt. Gorgolesco. Orders are to use only grenades and bayonets until first light. By dawn the positions have been taken.

____________________

Here is another account of Ferdinand’s last battle, from Charles J. Sanders’ The Boys of Winter – Life and Death in the U.S. Ski Troops During the Second World War:

Fortuitously obscured by a dense fog, the climbers attacked the stunned Nazi defenders at dawn. The Germans fell back in confusion as the Tenth Mountaineers charged out of the mist, firing and hurling grenades, and screaming demands for surrender. A number of the enemy capitulated, but the rest quickly regrouped. The Americans then endured fierce counterattacks throughout the following days, as the enemy desperately and unsuccessfully tried to stave off the main attack on Belvedere and its sister peaks by attempting to recapture the heights of Riva. Among the many who would give their lives holding this precious ground was Private Ferdinand Lebrecht of 86 C. He was a big Austrian-born mountaineer who had knelt in prayer with Jacques Parker and the others in the tiny attic at the base of Rive prior to the climb.

____________________

The story of the Lebrecht brothers appeared as two articles in The New York Post in January of 1951. The first article follows (transcribed below)…

Dad Receives 10 Hero Awards For GI Killed in Italy in 1945

Dad Receives 10 Hero Awards For GI Killed in Italy in 1945

The New York Post

January 19, 1951

The father of an Upper Manhattan soldiers killed in World War II near Mt. Sarrasiccia, Italy, on Feb. 20, 1945, today received belated recognition for the heroic feats of his son.

A Silver Star, Bronze Star Medal and eight other awards were presented to William Lebrecht, 920 Riverside Dr., father of PFC Ferdinand Lebrecht, who was 26 at the time of death, by 1st Army officials at a quiet ceremony in his home.

Official notification of the outstanding role played by young Lebrecht was received by the father a month ago in the form of a letter from the Army Dept., office of the Adjutant General, St. Louis, Mo. The letter said that, after five years of search, missing copies of general Army orders had been located, disclosing Lebrecht’s courageous record under fire.

First word of his son’s bravery came to Lebrecht from young men who kept dropping into his home during the past five years. Each said that, “Ferdie helped to save my life.”

The official message, signed by Col. John J. Donovan, said: “During a recent examination of the retained records of the 10th Mountain Division, the missing copies of General Orders announcing the award of the Silver Star to your son, service number 32,695,706, were located.

“Your pride in the gallantry displayed by your son in rendering aid to his wounded comrades while subjected to intense fire, will no doubt alleviate to some extent the grief caused by your great loss and the delay in receiving evidence of his heroism.

“It is hoped that these mementoes of your son’s outstanding service will be a source of comfort to you. They are tangible evidence of his country’s gratitude for the gallantry and devotion to duty that your son so courageously and heroically displayed.”

The general order itself, dated Nov. 21, 1945, specifying the posthumous award of the Silver Star, told of the uptown soldier’s care for his wounded comrades and how he died in the act of aiding his squad leader and several other men unable to move because of severe wounds suffered during fighting in a “most forward area.”

…while here is the second article, accompanied by a photograph of William, seated with Emma, holding his sons’ portraits. Their sons’ Purple Hearts are on the right, and Ferdinand’s Silver and Bronze Stars on the left.

Father Has 10 Medals For Son Slain in War

Father Has 10 Medals For Son Slain in War

The New York Post

January 21, 1951

It’s official now.

William Lebrecht, 920 Riverside Dr., has 10 medals, including a posthumous Silver Star, to prove that his son, Ferdinand, 26, a private, first class, died a hero on Mt. Sarrasiccia in Italy five years ago.

But the grieving exporter, who fled to this country from Nazi Germany in 1939, also had the sad memory of another son lost in World War II. Both sons had given their lives for the country in which he had hoped they would live in freedom.

The uptown man yesterday told the story of his sons, after an Army major and a captain came to his home last week from First Army Headquarters on Governor’s Island to bring him Ferdinand’s hero citation, which had been lost in heaps of Army records since Feb. 20, 1945.

And in recalling his sorrows, he revealed that the second son, Pfc. Alfred Lebrecht, 21, had been killed by Nazis while fighting on the Metz front in France – just 20 days after the older brother fell in action.

“Within a few short weeks,” the father said yesterday, speaking for himself and for his wife, Emma, “we lost everything we lived for.”

The death of Alfred was an especially bitter blow, since his parents had tried in vain to save him.

Soon after they learned of Ferdinand’s death, they went to Washington and begged that Alfred be withdrawn from the fighting front. War Dept. officials told them, however, that such measures were taken only after two fatal casualties in a family.

The Lebrechts returned home, only to receive word a week later that Alfred too had been killed.

A sergeant in Alfred’s outfit later told the father than the younger brother had been grieving about Ferdinand’s death at the time he was killed.

“He was so downcast,” the sergeant said, “that he just moved about in a daze.”

Told of Son’s Heroism.

The elder Lebrecht might never have known of Ferdinand’s posthumous citation had it not been for one of the beneficiaries of his son’s heroism. One of the eight men the young soldier saved in the action which cost his life visited the father and told him of the citation.

The War Dept., however, at that time reported it had no record of the citation, indicating that the records were lost. But after years of searching, they were turned up a month ago.

I don’t know if the Post reported any further stories about the Lebrecht family.

I don’t know if the Post reported any further stories about the Lebrecht family.

Then again, what more could be said?

________________________________________

Salus, Joseph W., PFC, 42057443, Infantry, Purple Heart

100th Infantry Division, 399th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Joseph Salus (father)

Mr. Francois Salus, Mr. Harry Salus, and Mr. William Salus (sons), 3560 Rochambeau Ave., New York, N.Y.

Harriet Hammer Minde (cousin); Gerson and Miriam Goldman (niece and nephew)

Cemetery unknown; Buried 9/28/48

Casualty List 4/19/45

Long Island Star Journal 4/7/45

The New York Times – Obituary Pages 9/27/48 and 9/28/48

American Jews in World War II – Not Listed

________________________________________

Semansky, Jack, Pvt., 36914179, Infantry, Purple Heart

78th Infantry Division, 311th Infantry Regiment, L Company

Born Detroit, Mi., 3/4/26

Mr. and Mrs. Louis [1891-8/2/60] and Nettie [1895-7/15/69] Semansky (parents), Elmhurst Ave., Detroit, Mi.

Mrs. Ann Gertrude (Semansky) Golden and Clare (Semansky) Tierman (sisters)

Machpelah Cemetery, Ferndale, Mi. – Section 6, Lot 18, Grave 151D; Buried 11/23/47

Detroit Jewish Chronicle 10/31/47

The Jewish News (Detroit) 6/15/45

American Jews in World War II – 195

An article about Private Semansky from the Detroit Jewish Chronicle of October 31, 1947…

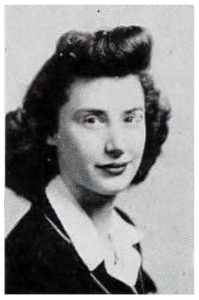

Though genealogical information about soldiers is not difficult to find, locating images of their next of kin is much more problematic. The case of Private Semansky is an exception: The lady below is his mother Nettie, as she appeared in an article in the Detroit Jewish Chronicle of May 7, 1943, at the age of forty-eight.

Though genealogical information about soldiers is not difficult to find, locating images of their next of kin is much more problematic. The case of Private Semansky is an exception: The lady below is his mother Nettie, as she appeared in an article in the Detroit Jewish Chronicle of May 7, 1943, at the age of forty-eight.

________________________________________

________________________________________

Sweet, Albert, S/Sgt., 36715694, Infantry, Purple Heart, in France

103rd Infantry Division, 411th Infantry Regiment, A Company

Born 10/21/05

Mrs. Judy Sweet (daughter)

Mr. and Mrs. Fishel and Rose Swislowsky (parents), Mrs. Annie Lohn (sister), 1542 S. Drake Ave., Chicago, Il.

Waldheim Jewish Cemetery (Ticktin Cemetery), Forest Park, Il.

American Jews in World War II – 118

Photograph of matzeva by Bernie_L

Photograph of matzeva by Bernie_L

________________________________________

Theodore, Julius (Yehuda bar Kasriel), Sgt., 31142262, Medical Corps, Purple Heart

100th Infantry Division, 397th Infantry Regiment, Medical Detachment

Born 1908

Mrs. Fanny Theodore (wife), 6 Vine St., Hartford, Ct.

Beth Alom Cemetery, New Britain, Ct. – Section DB

American Jews in World War II – 71

Photograph of matzeva by Jan Franco

Photograph of matzeva by Jan Franco

Killed Non-Battle

Beckenstein, Charles J., T/5, 33119096, Passenger (Infantry)

40th Infantry Division, Headquarters Company

Flight of C-46D 44-77360 from Elmore Field, Mindoro, to Tarauan, Leyte

Aircraft crashed 4 miles northwest of San Roque, Philippines. Loss covered in Missing Air Crew Report 15996.

The plane’s crew consisted of…

Pilot: 1 Lt. Wilson B. Haslan

Co-Pilot: 2 Lt. Myles V. Reed

Flight Engineer: S/Sgt. Arthur T. Poillucci

Radio Operator: Samuel A. Bruno

…and the aircraft carried 21 passengers, members of the Army ground forces and Army Air Force. There were no survivors.

As reported in MACR 15996: “C-46 (Commando) Transport plane which departed from Elmore Field, Mindoro, P.I., about 1630, 15 March 1945, with intended destination Tarauan, Leyte, P.I. Plane crashed into a mountain approximately 4 miles northwest of San Roque, Leyte, P.I. Accident was apparently due to weather conditions. All members of the crew and passengers were killed.”

An online memorial for 23 of the 25 crew and passengers of C-46D 44-77360 can be viewed at FindAGrave.

Corporal Beckenstein’s parents were Harry and Bella, of 949 Ridgemont Road, Charleston, in West Virginia.

Buried at Manila American Cemetery, Manila, Philippines – Plot F, Row 7, Grave 67

American Jews in World War II – Not Listed

Prisoner of War

Cohen, Jacob, S/Sgt., 33794401, Purple Heart, 1 Oak Leaf Cluster

3rd Infantry Division, 7th Infantry Regiment

(Wounded previously, around 6/6/44)

Born Salonika, Greece, 9/5/19

Mrs. Gertrude Cohen (wife), 412 Monroe St., Philadelphia, Pa.

Mrs. Esther Cohen [Magriso] (mother), 1515 S. 6th St., Philadelphia, Pa.

POW Camp unknown

The Jewish Exponent 4/27/45

The Philadelphia Inquirer 4/17/45

The Philadelphia Record 7/6/44 and 4/7/45

American Jews in World War II – 515

Wounded in Action

Abrahams, Henry G., 0-1328211, 2 Lt., Purple Heart, in France

Born East Orange, N.J., 1920

Mrs. Lola Ruth (Waldman) Abrahams (wife), 36-08 29th St., Astoria, N.Y.

Major Herbert Waldman (brother in law), 29-11 36th Ave., Long Island City, N.Y.

Casualty List 4/10/45

Long Island Star Journal 4/10/45

American Jews in World War II – 262

Pearl, James, S/Sgt., 33050971, Purple Heart, France

Born Philadelphia, Pa., 5/28/13

Mr. Harry Pearl (father), 1014 North 63rd St., Philadelphia, Pa.

Mrs. Elizabeth B. Pearl (mother), Deborah Rose and Rebecca (daughters), 1615 Robinson Ave., Philadelphia, Pa.

The Philadelphia Record 4/12/45

American Jews in World War II – 543

Zlotnick, Leon, Sgt., 33805527, Purple Heart, Germany

Born Philadelphia, Pa., 9/11/26

Mr. and Mrs. Gersin and Anna Zlotnick (parents), 619 Porter St., Philadelphia, Pa.

The Jewish Exponent April 20, 1945

The Philadelphia Inquirer 4/10/45

The Philadelphia Record 4/11/45

American Jews in World War II – 561

United States Army Air Force

8th Air Force

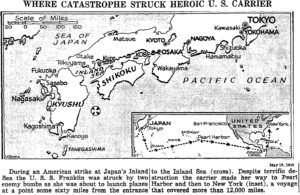

Eighth Air Force losses on March 15, 1945 (8th Air Force Mission 889) occurred during heavy bomber strikes against 1) German Army headquarters at Zossen, 2) marshalling yards at Oranienburg, Stendal, and Birkendwerder, 3) rail sidings and centers at Gardelegen, Wittenberge, and 4) targets at Gusen and Havelburg.

303rd Bomb Group, 427th Bomb Squadron: B-17G 43-39220, “GN * G”

MACR 13568, Pilot 2 Lt. Thomas W. Richardson, 8 crew members – all survived

Grossman, Howard Alvin, S/Sgt., 36035598, Radio Operator

Returned to Molesworth with crew after aircraft landed at Okecie Airfield, near Warsaw

Born Chicago, Il., 2/21/19

Mr. and Mrs. Morris and Anna (Marks) Grossman (parents), Chicago, Il.

American Jews in World War II – Not Listed

Tractman, Bernard Lawrence, F/O, T-133026, Navigator, 35 missions

Born Philadelphia, Pa., 6/9/22 (Died 9/15/97)

Mr. and Mrs. Morris and Betty (Saltzman) Tractman (parents), 1515 Elbridge St., Philadelphia, Pa.

Within MACR 13568, listed as a witness to the loss of B-17G 43-39220

American Jews in World War II – Not Listed

____________________

Four B-17G Flying Fortresses of the 447th Bomb Group, comprising one plane of the 709th Bomb Squadron and three of the 711th Bomb Squadron, were lost to flak on this mission. These aircraft were:

709th Bomb Squadron

42-97836, “Bugs Bunny Jr.”, “IE * P”, piloted by 1 Lt. Ralph D. Putnam and hit by flak near Wittenburg. The 447th Bomb Group Battle Damage Report mentions that the aircraft was seen by fighter pilots to have belly-landed in the Steinhuder Lake area. The entire crew of nine survived.

711th Bomb Squadron

44-6016, “TNT KATIE”, “IR * P”, piloted by 1 Lt. Henry M. Chandler, also struck by flak in the vicinity of Wittenburg. Of TNT KATIE’s nine crew members, three survived.

43-38731, “Blythe Spirit”, “IR * Q”. Piloted by 1 Lt. Harluf T. Jessen, the plane exploded after being hit by flak near the I.P. (I.P. – an acronym for “Initial Point”: “…some identifiable land mark about 20 miles more of less from the target. The formation flew there and at that point had to fly straight and level, no evasive action, to the target with the bomb bay doors open, usually under autopilot for the bombardier to do his job. This was sweating time. [Contributed by Wally Blackwell, B-17 pilot, at 398th Bomb Group website].) Only two of Blythe Spirit’s crew of ten survived.

43-38849, “IR * O”, piloted by 2 Lt. Lloyd L. Karst. Also hit by flak in the vicinity of the I.P, seven of the aircraft’s nine crewmen suvived the bomber’s “shoot-down”, but only five actually returned.

More detailed information about these aircraft and their crews is given below.

____________________

711th Bomb Squadron: B-17G 43-38731, “Blythe Spirit”, “IR * Q”

MACR 13044, Pilot: 1 Lt. Harluf T. Jessen, 10 crew members – 2 survivors

Hoffman, Walter Samuel, 2 Lt., 0-2065557, Navigator, Air Medal, Purple Heart

Captured: Wounded and Prisoner of War (Name of POW camp unknown)

Mr. Morris Hoffman (father), 673 Avenue D, Rochester, N.Y.

New York Sun 4/19/45

Rochester Times-Union 2/15/44, 10/13/44

Rome Daily Sentinel 4/18/45

American Jews in World War II – 347

“Blythe Spirit” was struck by flak in the aircraft’s bomb-bay, and, between its #3 and #4 engines. The aircraft fell straight down out of control and exploded. Though no parachutes were observed to emerge from the falling plane, miraculously there were two survivors: co-pilot 2 Lt. Robert P. Dwight (son of Mrs. Isabel Dwight, residing at 1787 Granville Ave., in West Los Angeles, California) and navigator Walter Samuel Hoffman, of Rochester, New York, who both – being shot down over central Germany – were inevitably captured.

The MACR includes Individual Casualty Questionnaires and Casualty Interrogation Forms covering the eight crewmen who did not survive, all these documents having been completed by Lt. Hoffman in late July of 1945, probably while at his home in Rochester. There are no documents in the MACR by Lt. Dwight.

With the exception of togglier S/Sgt. Hary E. Pfautz (probably already injured by flak, and not wearing a parachute) Lt. Hoffman’s comments about his fellow crewmen were all essentially the same: “Plane was hit by flak and went into a spin. The co-pilot and I were thrown out, and the plane broke into pieces. Neither of us [Lt. Dwight] saw any more parachutes. Later a German interrogation officer at Stendal POW Camp, Germany, told us that all eight men had been killed in the crash. He had a correct list of their names.”

According to Lt. Hoffman, the plane crashed approximately 30 nautical miles due west of Oranienburg. Fortunate in already wearing his parachute (he didn’t specify if it was a chest-chute or back-pack – probably the latter), he was thrown out of the B-17 through its shattered plexiglass nose (“after” S/Sgt. Pfautz), while Lt. Dwight, who was wearing a back-pack parachute (about which, see more below…) was also thrown to safety through the bomber’s nose.

Concerning his month in German captivity, there is no information.

____________________

711th Bomb Squadron: B-17G 44-6016, “TNT KATIE”, “IR * P”

MACR 13045, Pilot 1 Lt. Henry M. Chandler, 9 crew members – 3 survivors

The nose art of “TNT Katie”, displaying at least 53 mission symbols. (Image UPL 24300, from the Hutchinson & Cortright collection at the American Air Museum in Britain)

The nose art of “TNT Katie”, displaying at least 53 mission symbols. (Image UPL 24300, from the Hutchinson & Cortright collection at the American Air Museum in Britain)

Murachver, Sidney Albert, 2 Lt., 0-788410, Bombardier, Air Medal, 3 Oak Leaf Clusters, Purple Heart

Captured: Wounded and Prisoner of War (Name of POW camp unknown)

Born 10/30/22 – Died 8/26/05

Mrs. Rose Murachver (mother), 85 Francis St., Everett, Ma.

David, Joanne, and Roberta (children)

https://447bg.smugmug.com

American Jews in World War II – Not Listed

Skalka, David W., 2 Lt., 0-2000413, Navigator, Air Medal, 4 Oak Leaf Clusters, Purple Heart

Captured: Wounded and Prisoner of War (Name of POW camp unknown)

Born 1919

Mrs. Frances Skalka (mother), 265 E. 176th St., New York, N.Y. / Bronx, N.Y.

https://447bg.smugmug.com

American Jews in World War II – 447

The fate of TNT KATIE and her crew was to a degree similar to that which befell Blythe Spirit: The plane was directly struck by flak. Hit under the cockpit and nose, the plane was seen to break apart at the top turret. Airmen in nearby aircraft witnessed between three and four parachutes emerge from the falling plane.

Full information as to the fate of the bomber and its crew would would arrive after the war from the plane’s three survivors: First Lieutenant Henry M. Chandler (pilot), and Second Lieutenants Sidnay A. Murachver (bombardier) and David W. Skalka (navigator), all of whom succinctly and vividly recounted the events of their last mission in Individual Casualty Questionnaires or Casualty Interrogation Forms.

In sum, the flak burst blew the B-17’s bombardier / navigator (nose) compartment directly off the aircraft. Both Sidney Murachver and David Skalka, temporarily rendered unconscious and still within this falling section of the plane, in turn fell away or were blown free, and awakening in mid-air, parachuted to safety. The same flak burst tore away the B-17’s instrument panel, control columns, rudder pedals, throttle controls, and right wing, leaving (what was left) of the falling plane completely uncontrollable and in a near-vertical dive. After vainly attempting to assist co-pilot Velmer Diefe, pilot Henry Chandler was left with no choice but to drop through the wreckage into empty space, to land by parachute.

Notably, the three surviving crewmen specifically attributed their survival to back-pack type parachutes (probably of the “B-8” type; see the photograph below from The Rigger Depot), which by design and form they were already wearing when the plane was struck by flak. As such, unlike Lt. Diefe and their five fellow crewmen, they did not have to rely on chest-type parachutes, which an airman had – in case of emergency – to lift and then attach to double clips on his parachute harness. You can view this design of harness in the photo of Lt. Chandler’s crew (as worn by all five men in the front row) and, in the individual photos of Sergeants Ivos, Swem, Stephens, and Reinartson.

The photo shows a group of American fighter pilots, probably of the 8th or 9th Air Force, standing before the tail of a wrecked Focke-Wulfe FW-190 in the winter of 1944-45. The man on the left wears a back-pack (B-8) parachute, while the pilot on the right is wearing a seat parachute, to which is attached a one-man life-raft.

Text accompanying photo: “Originally designed by the Pioneer Parachute Company as their Model B-3-B, the USAAF’s copy (B-8) was standardized on October 1942. … The B-8 saw operational use in the ETO around late 1943, replacing the rigid B-7 and serving well into the postwar era. It was the standard rig for bomber pilots as well as operational fighter pilots of the P-38 and P-51.”

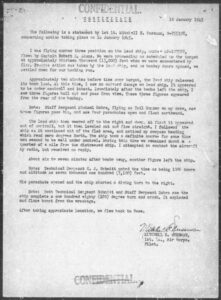

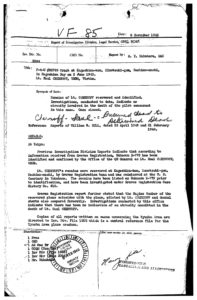

Here’s David Skalka’s statement in Missing Air Crew Report 13035 (not 13045), in reply to an inquiry from the Casualty Branch of January 11, 1946, concerning the loss of his crew:

Here’s David Skalka’s statement in Missing Air Crew Report 13035 (not 13045), in reply to an inquiry from the Casualty Branch of January 11, 1946, concerning the loss of his crew:

“The nose and right wing of the plane were torn away, as the bombardier and myself were blown clear, and the pilot, unlatching his safety belt, dropped out. Having been knocked unconscious, I woke up after falling through the air a few seconds and pulled my chute. I looked around and noticed pieces of the plane falling about me.”

And, here are Sidney Murachver’s comments, from his Casualty Questionnaire in Missing Air Crew Report 13045…

“The reason I know so little of my crew is that I was unconscious when I left my plane. I was probably knocked out by the concussion of the flak, which struck at the point where the nose of the B-17 joins the fuselage. I know only of the pilot, Lt. Henry Chandler, who bailed out, and the navigator, Lt. David Skalka, who was also blown out. We have never seen or heard any information as to the remaining six members of my crew. We presumed that they never left the plane because we were told that it fell about 1,000 ft & then exploded.”

…while Murachver also replied to the Casualty Branch inquiry of January 11, 1946:

“The nose of the plane was blown off and I was blown out of the nose, or through it, unconscious. I had on the new type back-pack parachute, fortunately. I came to while falling through the air and opened my chute. As for the rest of the crew, they all had chest pack chutes. We never heard of or saw them again. We were told that the plane fell a thousand feet and exploded.”

Likewise, Henry Chandler’s reply to the Casualty Branch, in MACR 13035:

“The action took place over Pearlburg, Germany, on March 15, 1945 at about 3:40 p.m. at which time our group was flying west following the bombing of a railroad yard at Oranianburg, north of Berlin. As out group passed over the same (flak) battery we received at least one direct hit between the nose and cockpit on the right side, completely demolishing the nose section, destroying the instrument panel and the glass enclosure of the cockpit and removing both sets of controls including the throttle quadrant. At the moment we were hit I was knocked unconscious. When I recovered the ship seemed to be in a vertical dive and the condition of the cockpit was as described above. My co-pilot, Lt. Diefe, was still in his seat and as soon as I realized there was no way in which to regain control of the airplane, I attempted to attract his attention and reach his chest pack which was hanging at his side of the seat. However, I was unable to get his attention nor to move far enough to reach his chute and left the wreckage before it crashed. I left the wreckage by releasing my safety belt and falling through the hole in front of me. I was wearing a back pack.”

____________________

1 Lt. Henry M. Chandler and his crew in a happier time: The men gather for an undated (but certainly Winter of 1944-45) group photo before B-17G 42-97836, Bugs Bunny Jr. (IE * P), of the 709th Bomb Squadron, mentioned above as having been lost to flak on March 15. (Image UPL 24298, from the Hutchinson & Cortright collection)

1 Lt. Henry M. Chandler and his crew in a happier time: The men gather for an undated (but certainly Winter of 1944-45) group photo before B-17G 42-97836, Bugs Bunny Jr. (IE * P), of the 709th Bomb Squadron, mentioned above as having been lost to flak on March 15. (Image UPL 24298, from the Hutchinson & Cortright collection)

As I was unable to identify this photograph at Fold3’s collection of WW II USAAF photographs, I suppose it was taken and archivally retained at the level of the 711th Bomb Squadron, and thus never went “further” into the main holdings of the Army Air Force. Notably, the unknown photographer – he had a good photographic eye – took individual portraits of eight of the crewmen, with each man standing near (or for the pilots, sitting within) his crew station. Thus, in the evocative images below, Ivos and Swem stand by a waist gun position, Stephens by the dorsal turret, Reinartson by the ball turret, Chandler and Diefe sit in the pilot’s seat, and Murachver and Skalka by the nose compartment entry / exit hatch.

Front row, left to right…

Sgt. Costas A. Ivos (Radio Operator) (Image UPL 24289, from the Hutchinson & Cortright collection)

Mr. and Mrs. Anthony and Garifelia Ivos (parents), Lowell, Ma.

Westlawn Cemetery, Lowell, Ma.

____________________

____________________

Sgt. Allan B. Swem (Waist Gunner) (Image UPL 24297, from the Hutchinson & Cortright collection)

Mrs. Bella M. Swem (mother), 1006 East Grand Boulevard, Detroit, Mi.

Ardennes American Cemetery and Memorial, Neuville-en-Condroz, Belgium

____________________

____________________

S/Sgt. Robert M. Stephens (Flight Engineer) (Image UPL 24295, from the Hutchinson & Cortright collection)

Mrs. Clara Wilkins Stephens (mother), 3rd Street, Manchester, Ga.

Ardennes American Cemetery and Memorial, Neuville-en-Condroz, Belgium

____________________

____________________

Sgt. Robert C. Reinartson (Ball Turret Gunner) (Image UPL 24296, from the Hutchinson & Cortright collection)

Mrs. Verna M. Reinartson (mother), 1620 12th Avenue South West, Fort Dodge, Ia.

Ardennes American Cemetery and Memorial, Neuville-en-Condroz, Belgium

____________________

____________________

Sgt. Rouse (?) (Not in this crew when aircraft shot down, and, going by records at Fold3.com, probably not a casualty)

____________________

Rear row, left to right:

1 Lt. Henry D. Chandler (Pilot) (Image UPL 24290, from the Hutchinson & Cortright collection) – Survived

Mrs. Marie Chandler (mother), 361 Gates Ave., Brooklyn, N.Y.

____________________

____________________

2 Lt. Velmer M. Diefe (Co-Pilot) (Image UPL 24294, from the Hutchinson & Cortright collection)

Mr. and Mrs. Frederick and Leontina Diefe (parents), Marlin, Wa.

Odessa Cemetery, Odessa, Wa.

____________________

____________________

2 Lt. David Skalka (Navigator) (Image UPL 24291, from the Hutchinson & Cortright collection) – Survived

____________________

____________________

2 Lt. Sidney A. Murachver (Bombardier) (Image UPL 24292, from the Hutchinson & Cortright collection) – Survived

Not in photo:

Not in photo:

Sgt. John R. Piccardo (Tail Gunner)

Mr. Peter J. Piccardo (father), 1701 West Acacia St., Stockton, Ca.

Casa Bonita Mausoleum, Stockton, Ca.

____________________

711th Bomb Squadron: B-17G 43-38849, “IR *O”

MACR 13030, Pilot 2 Lt. Lloyd L. Karst, 9 crew members – 5 survivors

Wiseman, Frank, 2 Lt., 0-926665, Navigator, Purple Heart, First mission

Apparently murdered upon capture. According to statements by fellow crew members and a captured B-24 crew member, he was beaten to death by civilians after safely landing by parachute near the city of Tangerhütte.

Born Lowell, Ma., 5/20/22

City College of New York Class of 1944

Mrs. Evelyn R. Wiseman (wife), 301 West 20th St., New York, N.Y.

Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Solomon [Died 8/4/00] and Anne Wiseman (parents); Ruth (sister); Rifka (sister; 6/20/21-6/29/21), 548 West 164th St., New York, N.Y.

Wellwood Cemetery, Farmingdale, N.Y. – Block 45, Row 4, Section B, Grave 8R; Buried 12/4/49

Casualty List 4/19/45

American Jews in World War II – 473

The crew of IR * Q

Pilot: Karst, Lloyd L., 2 Lt. – Survived (POW)

Co-Pilot: Courtney, Samuel E., F/O – Survived (POW)

Navigator: Wiseman, Frank, 2 Lt. – Murdered upon capture

Bombardier: Corr, Raymond F., Sgt. – Survived (POW)

Radio Operator: O’Connor, William M., Sgt. – Survived (POW)

Flight Engineer: Isham, James M., Jr., Sgt. – Murdered upon capture

Mrs. Florence Isham (mother), Route Number One, Box 13, Buena Park, Ca.

Ardennes American Cemetery, Neupre (Neuville-en-Condroz), Belgium, Plot A, Row 15, Grave 16

Awards: Purple Heart

Gunner (Ball Turret): Hannah, Cecil W., Sgt. – Survived (POW)

Gunner (Waist): Dove, Clyde Sherwood, Jr., Sgt. – Killed in action

Gunner (Tail): Huschka, Bernard F., Sgt. – Killed in action

Though it was assumed by other crews that this B-17 was headed to Russian-occupied territory, the crew, with the plane’s #4 engine feathered and the pilot and co-pilot reportedly wounded, experienced a very sad fate.

As revealed by co-pilot Courtney in post-war documentation, the aircraft never reached the Russian lines, for in reality, the aircraft lost power in all four engines and then caught fire.

Pilot Karst, co-pilot Courtney, navigator Wiseman, togglier Corr, flight engineer Isham, and waist gunner Dove parachuted from the aircraft. Dove, who had been calling for tail-gunner Huschka to parachute, remained too long in the aircraft, and was killed when he jumped at too low an altitude for parachute to fully open. Radio operator O’Connor, ball turret gunner Hannah, and tail gunner Huschka (probably wounded or already dead) “rode the plane in”, the former two when they realized that the plane was already at too low an altitude for a safe parachute jump. Remarkably, they survived the crash of the unpiloted bomber near Tangerhütte, Germany, albeit O’Connor’s back was fractured.

As for Frank Wiseman and Harry Isham?

Though they made successful parachute jumps (Wiseman from 12,000 feet), they did not live to become prisoners of war. According to statements in the MACR, both men were apparently murdered – beaten to death – by civilians upon landing. They were seen lying near one another by an American POW from another aircrew, whose name in the MACR is listed as “Jack Smith”. This man was probably Corporal Jack E. Smith, a radio countermeasures operator in the 565th Bomb Squadron of the 389th Bomb Group, who parachuted north of Magdeburg (52-40 N, 11-33 E) from B-24J 44-10510 (“You Cawn’t Miss It”, “YO * Q”) during a mission to Zossen, after his plane’s #2 engine caught fire from flak. Ironically, pilot 1 Lt. Harold G. Chamberlain flew the bomber back to base.

Based on Individual Casualty Questionnaires in the Missing Air Crew Report, this seems to have been the Karst’s crew’s first mission.

There’s no Case File in NARA Records Group 153 (Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General) concerning Frank Wiseman, probably because the location of the aircraft’s loss – in what would become the Soviet Zone of Occupation of Germany, during the (first) Cold War – prevented American and Allied military investigators from investigating this incident, and identifying and prosecuting the murderers.

Frank Wisemen was one of a number of Jewish WW II servicemen in both the European and Pacific theaters who did not survive their initial capture, and / or their eventual captivity. This was either because of the grim chances of fate that potentially befall all prisoners of war, or – in the European theater, in some cases – calculation: Because they were Jews.

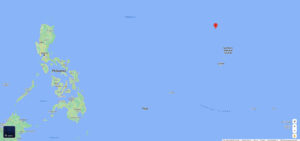

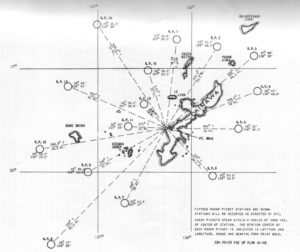

This map shows the location of Tangerhütte in relation to Berlin….

…and here’s a map view of Tangerhütte and nearby towns at a larger scale…

…and here’s a map view of Tangerhütte and nearby towns at a larger scale…

…while this is an air photo view of the above map, at the same scale.

…while this is an air photo view of the above map, at the same scale.

____________________

____________________

487th Bomb Group, 838th Bomb Squadron: B-17G 43-38028, “High Tailed Lady”, “2C * O”

Pilot: 2 Lt. William C. Sylvernal. 9 crew members – all survived. Aircraft crash-landed in Russian-occupied Poland; Entire crew eventually returned to squadron.

Forgotson, Donald, T/Sgt., 32992703, Flight Engineer, Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal, 2 Oak Leaf Clusters, Purple Heart

487th Bomb Group, 838th Bomb Squadron

Injured in crash-landing.

No Missing Air Crew Report

Born 1917

Mrs. Roslin Forgotson (wife), 2055 Anthony Ave., Bronx, N.Y.

Mr. Jerry Garavuso (son-in-law)

487th Bomb Group.org – Photo – High Tailed Lady

487th Bomb Group.org – Aircraft Roster

487th Bomb Group.org – 838th Bomb Squadron Roster

American Jews in World War II – 311

This is the probable loading list (crew roster) for mission of March 15, 1945, based on information at 487th Bomb Group wesbite:

Sylvernal, William C., 2 Lt. – Pilot

Peachey, Jim L., 2 Lt. – Co-Pilot

Personette, Chester A., 1 Lt. – Navigator

Forgotson, Donald, S/Sgt. – Flight Engineer

Taylor, Harold F., Cpl. – Radio Operator

Montague, Paul M., Cpl. – Gunner (Ball Turret) (and, Hughey, Henry W., S/Sgt.?)

Kennedy, Harold L., Cpl. – Gunner (Waist)

Payne, Harold L., Cpl. (or) Walsh, George P., Cpl. – Gunner (Tail)

____________________

The High-Tailed Lady amidst flak bursts over Germany. (Image FRE 8544, from the Roger Freeman collection)

The High-Tailed Lady amidst flak bursts over Germany. (Image FRE 8544, from the Roger Freeman collection)

The rather fragmented wreck of the High-Tailed Lady, behind Soviet lines in Poland. (Photo from 487th Bomb Group wesbite.)

The rather fragmented wreck of the High-Tailed Lady, behind Soviet lines in Poland. (Photo from 487th Bomb Group wesbite.)

____________________

The following account of the High Tailed Lady’s final mission and the return of her crew was written by ball turret gunner Paul M. Montague (this was his 17th mission), and appears Martin Bowman’s Castles in the Air – The Story of the B-17 Flying Fortress Crews of the US 8th Air Force.

“This mission was another long haul into and out of Germany. Our crew in the High Tailed Lady had made it before. All went well until we approached the turning point toward the IP west of Berlin. We were flying at 24,000 feet when, suddenly, an accurate burst of flak hit our ship. The co-pilot was seriously wounded, one engine quit, the intercom only functioned sporadically and all the control cables on the port side, except the rudder, were severed. This caused us to bank to starboard at about 30 degrees. We dropped from formation, apparently unseen, lost altitude and turned toward Berlin. At only 12,000 feet over Berlin a second flak burst smashed part of the Plexiglas nose, stopped a second engine, ruptured the oxygen system and started a fire in the bomb bay. Twelve 500 pounders stuck there would neither jettison or toggle. Several crew members were hit by shrapnel. Our pilot gave us the alternative of baling out or staying while he attempted to ride the Lady down to a crash landing in Poland. As we gazed directly down at the Tiergarten, no-one had the nerve to jump! The fire in the bomb bay was finally extinguished and we managed to jettison our bombs into a lake below. Thankfully, we were alone. No German fighters appeared. As we crossed the Oder River at only a few thousand feet, our Russian allies fired on us but no hits were sustained.

“Our pilot did a magnificent job of approach to what appeared to be a level field enclosed on three sides by woods. We had no flaps, gear, air speed indicator and many other vital instruments but all the crew survived the crash landing. The co-pilot and the engineer were later placed in a hospital for Russian wounded and the seven remaining crew were ‘looked after’ by their Russian army hosts. The crew were disrobed by some Russian army women who then proceeded to wash them with cloths and basins of water. Their uniforms were taken away and replaced with ‘pyjamas’ (the type worn in concentration and prison camps). Paul Montague continues. Little did we seven suspect that everything would be pantomime for two ensuing weeks and these pyjamas would be our clothes. We were under constant guard. We were prisoners – not guests of our ‘allies’. Just as we were falling asleep several of us heard the unmistakable click of the lock in our door.

“Next morning we had our first breakfast. I recall being very thirsty and I spotted a large cut-glass container of water in the centre of the oval breakfast table. After pouring a glass-full, I took a large swallow and my breath was whisked away! Pure vodka at 05:30! I tried to warn the crew members but was speechless. A few others made the same error. The Russians roared with laughter. For the next two weeks we used vodka in our cigarette lighters; it worked marvelously – like an acetylene torch!”

Montague and his fellow crew members were finally transported to Poznan and on through Poland to Lodz where they continued to Kiev. They finally reached a Russian fighter base near Poltava where a Lend-Lease C-46 flew them nearer freedom. Paul Montague recalls. ‘After flying for quite a time we noticed the co-pilot coming back to the area where the wing joins the fuselage. He unscrewed a cap of some sort, removed a rubber siphon from his jacket and proceeded to drink something. Could this possibly be de-icer fluid? Our pilot, his head still bandaged from our crash, remarked, ‘My God! I may have to end up flying this plane’. After flying some hours at high altitude over some mountain ranges, we began our descent and finally made a very rough landing in Tehran, Persia. This was the last we were to see of any Russians. After spending a few days at the American base in Tehran we were flown on to Abadan by an American pilot in a C-47 transport. From then on it was shuttle hops by American pilots to Cairo, a nearly deserted base in the Libyan desert, on to Athens, Paris and finally to Lavenham. Since we were due for “R&R” about this time, we were granted a week’s leave and spent a most pleasant time in Girvan, Scotland, before returning to base to fly two more missions.”

“Crew of the High Tailed Lady pose with their Russian hosts. Paul Montague, the ball turret gunner, is second from left in the back row. (Montague)”

“Crew of the High Tailed Lady pose with their Russian hosts. Paul Montague, the ball turret gunner, is second from left in the back row. (Montague)”

________________________________________

Dressler, Jacob (“Jack”) Harry, 2 Lt., 0-824608, Fighter Pilot, Air Medal

355th Fighter Group, 357th Fighter Squadron

“Lieutenant Dressler on this mission ran short of gas and was last seen heading toward the Russian lines. He wasn’t heard for two weeks and was given up as missing in action. Then on the 30th of March the report came in that he was safe and was on his way back to the squadron.”

No MACR; Aircraft P-51D 44-14314 “Sexless Stella / One More Time”, “OS * L”

Born Brooklyn, N.Y., 4/25/23, Died 11/2/17

Mr. and Mrs. Morris [12/27/95] and Anna (Braunfeld) Dressler (parents), 81-21 20th Ave., New York, N.Y.

Jack, Miriam [8/22/26-3/19/06], and Paul (sister and brothers)

American Jews in World War II – 299

Information about Jack Dressler – identical to the record above – appears in an earlier blog post, concerning the experiences of Lieutenant William Stanley Lyons as a fighter pilot, both having served in the 357th Fighter Squadron of the 355th Fighter Group.

________________________________________

15th Air Force

Dobkin, Joseph, F/O, T-129423, Bombardier, Air Medal, Purple Heart

98th Bomb Group, 415th Bomb Squadron

MACR 12998, Aircraft B-24L 44-50225, “red T”, Pilot 1 Lt. Charles H. Estes, 11 crew members – all survived

WIA; Returned with crew (presumably after parachuting over, or landing in, Yugoslavia)

Mrs. Rose Dobkin (mother), 3054 Pingree, Detroit, Mi.

American Jews in World War II – 189

Koty, Gerald, T/Sgt., 20251634, Radio Operator

463rd Bomb Group, 772nd Bomb Squadron

MACR 12999, Aircraft B-17G 44-6555, Pilot 1 Lt. Walter R. Griffith, 11 crew members – all survived

Returned with crew (possibly after presumably parachuting over, or landing in, Yugoslavia)

Mr. and Mrs. Morris and Florence Koty (parents), 465 National Blvd., Long Beach, N.Y.

Lew Koty and Helen (Koty) Globus (brother and sister)

American Jews in World War II – Not Listed

Polish People’s Army [Ludowe Wojsko Polskie]

Broch, Aleksander, WO, in Poland, at Zachodniopomorskie, Kolobrzeg

Born Sosnowiec, Poland, 1923

Mr. Stanislaw Broch (father)

Kolobrzeg Military Cemetery, Kolobrzeg, Poland

Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II: Vol I, p 73

Chuszycer, Szaul, Pvt., during Operation Pomeranian Wall

4th Infantry Regiment

Mr. Jakub Chuszycer (father)

Place of burial unknown

Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II: Vol I, p 13

Gotszalek, Wlodzimierz, WO, in Poland, at Pomorskie, Reda, during Operation Pomeranian Wall

1st Tank Brigade

Born Brodniki, Kujawsko-Pomorskie, Poland, 1912

Mr. Stefan Gotszalek (father)

Place of burial unknown

Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II: Vol I, p 25

Lelkowski, A., Sergeant Major, in Poland, at Zachodniopomorskie, Walcz (died at Walcz Hospital)

11th Infantry Regiment

Kochanowka, Poland, 1922

Mr. Szmuel Lelkowski (father)

Place of burial unknown

Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II: Vol I, p 44

Rad, Ben Zion, Cpl., in Poland, at Zachodniopomorskie, Kolobrzeg

11th Infantry Regiment

Born Lodz, Poland, 1909

Mr. Michael Rad (father)

Place of burial unknown

Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II: Vol I, p 95

Sajort, Icek, Pvt., in Poland, at Zachodniopomorskie, Gryfice

Kamien Pomorski Military Cemetery, Kamien Pomorski, Poland

Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II: Vol IV, p 103

Suchopar, Jozef, Pvt., in Germany, at Kolberg

Born Milkiewicze (d. Nowogrodek), Poland, 1924

Mr. Seymour Suchopar (father)

Kolobrzeg Military Cemetery, Kolobrzeg, Poland

Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II: Vol I, p 64

Widomlawski, Nachum, at Field Hospital 45, during Operation Pomeranian Wall

Born 1913

Mr. Icchak Widomlawski (father)

Place of burial unknown

Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II: Vol I, p 74

Soviet Union

Army Ground Forces / Red Army

Killed in Action

Gekhtman, llya Natanovich (Гехтман, Илья Натанович), Junior Sergeant (Младший Сержант)

Cannon Commander (Командир Орудия)

55th Guards Rifle Division, 213th Tank Battalion

Wounded 3/15/45; Died of wounds (умер от ран) 3/20/45

Born: 1914

Wife: Sofya Aleksandrovna Valoshina

Memorial Book of Jewish Soldiers Who Died in Battles Against Nazism – 1941-1945 – Volume V – 452 [Книги Памяти евреев-воинов, павших в боях с нацизхмом в 1941-1945 гг – Том V – 452]

Gerber, Abram Kelmanovich (Герберь, Абрам Кельманович), Guards Lieutenant (Гвардии Лейтенант)

Tank Platoon Commander (Командира Танкового Взвода)

31st Tank Corps, 237th Tank Brigade, 3rd Tank Battalion

Killed in action (убит в бою)

Born: 1912; Wife: Frida Markovna Gerber

Memorial Book of Jewish Soldiers Who Died in Battles Against Nazism – 1941-1945 – Volume V – 443 [Книги Памяти евреев-воинов, павших в боях с нацизхмом в 1941-1945 гг – Том V – 443]

Krolik, Iosif Peysakhovich (Кролик, Иосиф Пейсахович), Guards Junior Lieutenant (Гвардии Младший Лейтенант)

Rifle Platoon Commander (Командир Стрелкового Взвода)

18th Guards Rifle Division, 53rd Guards Rifle Regiment

Killed (убит)

Born 1922, Tolochinskiy raion, Vitebsk oblast

Friend / Acquaintance: Nina Mikhaylovna Savinich

Levin, Boris Mikhaylovich (Левин, Борис Михайлович) Guards Junior Lieutenant (Гвардии Младший Лейтенант)

Rifle Platoon Commander (Командир Стрелкового Взвода]

1st Guards Tank Army, 19th Guards Motorized Brigade

Died of wounds (умер от ран), at Mobile Field Hospital 470 (Полевой Подвижной Госпиталь (ППГ) 470)

Born 1925, city of Omsk

Father: Mikhail Iosifovich Levin

Levin, Solomon Iosifovich (Левин, Соломон Иосифович), Lieutenant (Лейтенант)

Rifle Platoon Commander (Командира Взвода)

313th Rifle Division, 1072nd Rifle Regiment

Killed (убит)

Born 1908, city of Borisov, Minsk oblast, Belorussian SSR

Sister: Anna Iosifovna Levin

Magid, Leonid Moiseevich (Магид, Леонид Моисеевич), Junior Lieutenant (Младший Лейтенант)

Rifle Platoon Commander (Командир Стрелкового Взвода)

5th Rifle Division, 190th Rifle Regiment

Killed (убит)

Born 1923, city of Simferopol

Mother: Juliya Magid

Milner, Zinoviy Abramovich (Мильнер, Зиновий Абрамович), Guards Senior Lieutenant (Гвардии Старший Лейтенант)

Rifle Platoon Commander (Командир Стрелкового Взвода)

60th Guards Rifle Division, 180th Guards Rifle Regiment

Killed (убит)

Born 1912, City of Polotsk, Vitebsk oblast

Pritsman, Isaak Samuilovich (Прицман, Исаак Самуилович), Junior Lieutenant (Младший Лейтенант)

Self-Propelled Gun Commander (Командир Самоходной Установии) SU-100 (СУ-100)

17th Guards Tank Brigade, 1st Tank Battalion

Killed (убит)

Born: 1922

Father: Samuil Borisovich Polikarpov

Memorial Book of Jewish Soldiers Who Died in Battles Against Nazism – 1941-1945 – Volume III – 168 [Книги Памяти евреев-воинов, павших в боях с нацизхмом в 1941-1945 гг – Том III – 168]

Reytburg (or) Roytburd, Boris Avisheevich (Рейтбург (или) Ройтбурд, Борис Авишеевич), Guards Lieutenant (Гвардии Лейтенант)

Company Commander (Командир Танковой Роты)

10th Guards Tank Corps, 62nd Guards Tank Brigade, 3rd Tank Battalion

Killed (убит), in Lower Silesia, Gross Brizen, Germany (Германия, Гросс Бризен, Нижняя Силезия)

Born: 1922 or 1924

Father: Avishim Berkovich Reytburg (or) Roytburd, Vinnitskaya Oblast, Bershad, Uritskiy Street, Building 1

Memorial Book of Jewish Soldiers Who Died in Battles Against Nazism – 1941-1945 – Volume VI – 248; Volume XI – 282 [Книги Памяти евреев–воинов, павших в боях с нацизхмом в 1941-1945 гг – Том VI – 248, Том XI – 282]

Military Air Forces – VVS

Beylin, Sakhno Ayzikovich (Бейлин, Сахно Айзикович), Senior Technician-Lieutenant (Старший Техник-Лейтенант) Senior Technician / Construction (Старший Техник по Строительству)

2nd Air Army, 26th Air Base Area, 83rd Airfield Engineer Battalion

Killed in plane crash (Погиб при Катастрофе самолета)

Born: 1920

Sister: Anna Ayzikovna Beylin

Passenger in Po-2 (По-2) piloted by Junior Lieutenant Dmitriy Fedorovich Popov (Младший Лейтенант Дмитрий Федорович Попов); Both Killed

Memorial Book of Jewish Soldiers Who Died in Battles Against Nazism – 1941-1945 – Volume V – 160 [Книги Памяти евреев-воинов, павших в боях с нацизхмом в 1941-1945 гг – Том V – 160]

Images of the Po-2 / U-2 are abundant, which is hardly surprising given the aircraft’s long history, versatility, and lengthy production run, over 33,500 having been constructed between 1928 and 1954. However, one of the better representations of the aircraft is actually plastic-model “box-art” painting for the ICM Model Company’s 1/72 kit of the U-2 / Po-2VS. The painting clearly shows significant features of the aircraft (the depicted example, aircraft “white 19” of the 889th Night Light Bomber “Novorossiysk” Regiment (former 889th Composite / Aviation Attack Regiment, 654th Night Light Bomber Regiment) flown by a female crew) – like its five-cylinder Shvetsov M-11 engine – more clearly than many photographs. While the camouflage and markings of the plane crewed by Beylin and Popov are unknown, the painting nonetheless gives a nice depiction of the aircraft’s general appearance.

United Kingdom

Died of Illness

Ohrenstein, Edward, LAC, 3003850

Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (probably stationed at RAF Stornoway)

Died of illness in Yishuv

Born 1926

Mr. and Mrs. Isaac and Bluma Ohrenstein (parents), Petach Tikva, Israel

Miss S. Ohrenstein (sister), 20 Charles Ave., Thornbury, Bradford, England

Bradford (Scholemoor) Jewish Cemetery, Yorkshire, England – Grave 166

The Jewish Chronicle – 3/30/45

We Will Remember Them Volume I, p 218

“VICTIM OF GERMAN FASCISM – DEEPLY MOURNED BY PARENTS AND SISTERS”

Photograph of matzeva by Bob the Greenacre Cat

Photograph of matzeva by Bob the Greenacre Cat

Killed in Action

Martin, Felix Mondschein, Trooper, 13053492

Royal Armoured Corps, 3rd Carabiniers (POW Dragoon Guards)

Born 1920

Mr. and Mrs. Max and Eugenia Mondschein (parents)

Taukkyan War Cemetery, Taukkyan, Rangoon, Myanmar – 19,J,19

We Will Remember Them Volume I, p 218

“HE GAVE HIS LIFE FOR THE SALVATION OF HIS OPPRESSED PEOPLE”

Finkelstein, Hans, Sapper, PAL/13194

Finkelstein, Hans, Sapper, PAL/13194

Royal Engineers

Died in Yishuv

WWRT I as “Finkelstein (Funkel), Hans”; CWGC as “Funkenstein, Hans”

Heliopolis War Cemetery, Heliopolis, Cairo, Egypt – 4,A,27

We Will Remember Them Volume I, p 243

________________________________________

________________________________________

References

Bowman, Martin W., Castles in the Air – The Story of the B-17 Flying Fortress Crews of the US 8th Air Force, Patrick Stephens, Wellingborough, Northants, England, 1985

Dublin, Louis I., and Kohs, Samuel C., American Jews in World War II – The Story of 550,000 Fighters for Freedom, The Dial Press, New York, N.Y., 1947

Meirtchak, Benjamin, Jewish Military Casualties in the Polish Armies in World War II: I – Jewish Soldiers and Officers of the Polish People’s Army Killed and Missing in Action 1943-1945, World Federation of Jewish Fighters Partisans and Camp Inmates: Association of Jewish War Veterans of the Polish Armies in Israel, Tel Aviv, Israel, 1994