Part X: Fragments of Memory

The annals of military aviation – at least in terms of popular culture – by definition and nature tend to focus on aerial combat; victories and losses; interactions with the air arms of allied and enemy nations; survival in the face of daunting odds – and the inexplicable vagaries of fate; the technology of flying and aerial combat; camouflage, unit insignia, and “nose art”; living conditions experienced at remote military bases; interactions with comrades from different regions and cultures; interactions with civilians in foreign lands.

It seems that relatively less attention is accorded to human nature: Personal histories, personalities, and perhaps a flyer’s perspective on the very nature and purpose of his military service. Perhaps this is only natural, for we’re talking about a period in a man’s life in a physical setting hardly conducive (!) to deep thought, and contemplation – but then again, not altogether alien to such feelings either. However, I would think that for most men, introspection typically comes later: years, if not decades, after one’s military service.

With that perspective in mind, and in spite of virtually all of Milton’s personal correspondence having been destroyed decades ago; with relatively little of his military documentation surviving, it is still possible to form a general “picture” of him as a “person” as much as a pilot, based upon recollections of friends and family.

These follow below:

Memories of Milton Joel: Virginia

From Maurice L. Strause, Jr., Milton’s friend from the University of Virginia: “(Milton) came to the University of Virginia as a freshman in my senior year. I knew him to be bright and well spoken, but he did not, in retrospect, seem a fighter pilot type. He was pudgy in those days as were most of us, since out $30.00 per month for meals bought mostly bread and potatoes. It was as about as deep as the depression got.”

“I recall that he was an only child – and the apple of his parent’s eyes. He was a child of their old age – at least that is how it seemed to me. I was four or five years older than he and his parents were considerably older than mine.”

From Sara F. Markham, best friend of Milton’s wife Elaine: “I met Milton Joel when I was about fourteen. He and my brother (who was skipper of a sub chaser in World War II) were dear friends and often spent weekends on the Piankatank River at the Joel’s summer cottage in their youth. Often, too, my parents and I were there. Though Leonard knew Milton from childhood (they grew up in the same neighborhood), I became part of “their crowd” when our interest in the opposite sex prevailed. I grew up in a small town twenty-three miles away.”

Memories of Milton’s wife, Elaine (Ebenstein) Joel

Sara F. Markham, “Elaine [later Friedlich] was my best friend in the world and the one person, perhaps, who deserved to share her life with Milton.”

Milton’s cousin Bettie J. Jacobs recollected that Milton and Elaine (from New York City) met in San Francisco. She was, “Beautiful, charming, blonde, thin, regal. Unfortunately, prior to Elaine’s death from cancer, she destroyed Milton’s letters to her, which probably would have shed a little more insight into this unusual and unbelievably brave man.”

Milton’s Personality

Leonard Kamsky, a childhood friend of Milton and his Milton’s cousin Harold Winston, and who later served in the 8th Air Force: “My most memorable vacation as a teenager was with Milton on the Piankatank River near the Chesapeake Bay. He went off to University of Virginia while I stayed at the University of Richmond. Milton had the strongest personality of anyone of my early acquaintance, in the sense of being a real leader and doer. At the same time he was the nicest guy you would ever meet. I pretty much lost track of Milton when he went into the service, training as a fighter pilot. I have to admit I envied him that glamorous life. I went into the Air Force (Air Corps at that time) as a lowly ground GI, thanks to flat feet and eye glasses.”

Leonard served in the VIII Fighter Command, where he, “…received reports on all the Squadrons at that time.” He served, “…under General Kepner who, I understood, was a great admirer of Milton as a pilot. I contacted Milton immediately [upon my arriving in England] and a few days later [Sunday, November 28, 1943] when he came to Command HQ.”

“That evening, after taking care of his affairs, he came to stay with my English family, John and Nance Russell and their 2 children. I shall never forget how he got on with the Russells – just great, smoking our pipes. John had an especially aromatic tobacco which he shared with us. But, I was almost an aside. Milton had this fantastic ability at repartee and they had become the best of friends in no time. John was head of an engineering firm that, unknown to me then, was producing the units for the artificial harbour used on D-Day on the Normandy coast. They loved Milton and, as you may know, kept in touch with his parents in Richmond long after the war.”

A Question of Motivation

According to Harold Winston, Milton, “Talked about becoming a pilot, in high school. He did not wish to follow in the jewelry business.” This is corroborated by Bettie J. Jacobs, who recalls that Milton, “…joined the service because he wanted to fly; he didn’t necessarily want a military career.” [His V-mail letter of September 3, 1943, to his parents suggests otherwise.]

Maurice L. Strause, Jr., and Leonard Kamsky expressed the same thought concerning Milton’s identity as a Jew, in the context of his military service.

In Mr. Strause’s words, “…neither Milton or I, or Morton Marks Jr., a member of our same Reform Congregation and a winner of the D.S.C ever thought of ourselves in the context of “Jewish Warriors”. We were just American citizens fighting for our country and whether we were in one theatre or the other was luck of the draw.”

And, Mr. Kamsky’s thoughts, “The bottom line is that Milton was a wonderful human being, highly intelligent and devoted to duty. I don’t buy that he was trying to prove anything in the way of being over-daring as a kind of off-set to being Jewish. He did what he did because it was the right thing to do. He was a great leader of men. He had the bad luck of flying a plane so badly designed that no amount of skill could be of much use.”

[As discussed in the prior post, I respectfully disagree with Mr. Kamsky’s characterization of the P-38 Lightning. And, as revealed by a letter below, there may be more depth to the intersection between Milton’s identity as a Jew, and his military service, than was superficially apparent…]

Milton Joel as a Leader of Men

“Major Joel sure is a swell guy. He could just give us orders & not bother to consult us but he’s not like that. Whenever anything comes up, he calls a meeting of the officers & asks our opinion & really wants us to tell him if we disagree with what he says. There aren’t many squadron commanders like him & all the boys are all for him & would do anything for him.”

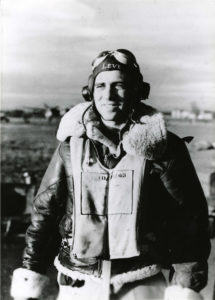

The above comment is an excerpt from a letter penned by 2 Lt. Morris Leve on February 29, 1943, to his parents, Benjamin and Eva (Zisk) Leve, who lived at 1420 Cortelyou Road in Brooklyn, New York. At the time, Lt. Leve was stationed at Paine Field, Washington with the 38th Fighter Squadron.

This photo shows Lt. Leve at Nuthampstead, wearing a B3 sheepskin flying jacket. (Picture via Morris Leve’s nephew, Robert Leve.)

Here’s a contemporary (2014) Oogle Street view of 1420 Cortelyou Road, where the latter intersects with Marlborough Road.

This is Justin O’s photograph of the storefront of King’s County Wines, which now occupies 1420’s Cortelyou Road’s first floor.

This is Justin O’s photograph of the storefront of King’s County Wines, which now occupies 1420’s Cortelyou Road’s first floor.

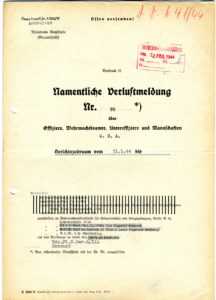

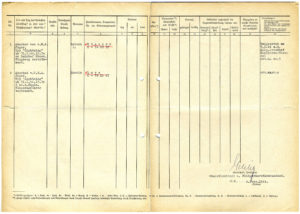

Lieutenant Leve was killed in action on January 31, 1944, during a fighter sweep to Venlo and Arnheim, Holland, while flying P-38J 42-67768 on his thirtieth mission. The plane’s loss is covered in MACR 2110 and Luftgaukommando Report AV 641/44.

Lieutenant Leve was killed in action on January 31, 1944, during a fighter sweep to Venlo and Arnheim, Holland, while flying P-38J 42-67768 on his thirtieth mission. The plane’s loss is covered in MACR 2110 and Luftgaukommando Report AV 641/44.

He had been flying as element leader to 1 Lt. Leroy V. Hokinson, Jr., seen below at Williams Field in 1943, in photo (UPL 19574) from The American Air Museum in Britain. The pair were shot down by FW-190s, probably of Jagdgeschwader 1. Lt. Hokinson, on his sixth mission, shot down two of these enemy planes and then parachuted to safety from his Lightning, P-38J 42-67813 (MACR 2107). He evaded capture and returned to American forces on September 11 of that year, after journeying in a very (very (very!)) roundabout way through various locations in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg.

You can read Lt. Hokinson’s brief account of his experiences in Escape and Evasion Report 1938, while his post-return Encounter Report of January 31, 1944 (from the 55th Fighter Group website) follows:

You can read Lt. Hokinson’s brief account of his experiences in Escape and Evasion Report 1938, while his post-return Encounter Report of January 31, 1944 (from the 55th Fighter Group website) follows:

I was flying Swindle White 4 on Lt. Leve’s wing after we had been separated from the rest of the group in a fight near the vicinity of Venlo. Returning to our base at deck level, we were bounced by seven FW190’s from above at 7 o’clock near Eindhoven, Holland. Lt. Leve and I broke into them at about the same time, I cutting inside. As the Jerries passed over us and made a sharp turn back, we set up two Luftberries about a thousand yards apart. Lt. Leve became engaged with four FW190’s and I with three. They were making diving passes at us and we were turning with flaps to increase deflection. Lt. Leve made about a turn and a half when I observed that he was on fire in the cockpit. I straightened out of my turn and headed after the 190 that was firing on him, but I was too late to help him for he was already headed for the deck blazing all over. I yelled for him to pull up and bail out but I don’t believe he heard me. Meanwhile, closing to about 100 yards of the FW190, I opened up at about 10 degrees deflection and observed strikes immediately. Closing in closer and still firing I saw the E/A begin to pour out smoke. Then he broke and headed down and crashed. I therefor (sic) claim this FW190 destroyed.

At the same time the above E/A crashed I broke, as another was on my tail firing. As I continued a tight turn to the left, I saw Lt. Leve’s plane hit the ground and explode and smoke coming up from the 190 behind some trees. Another 190 was coming in in a shallow diving turn at 11 o’clock. I rolled out once more and began a head-on attack – both of us firing like mad. I observed strikes on his wing roots and cowling. Then he broke and headed along the deck smoking, apparently out of control. This 190 must have hit my gas line, for my left engine was on fire. Deciding to get out, I pushed the throttle full forward and pulled straight up. 190’s were following me all the way and they blew off my left wing tip and were hitting the cockpit right behind me. At about 2000 ft. I was slowed down to about 150 A S [air speed] and let go the canopy. The Jerries stopped firing as I bailed out and landed safely. Later I was informed by the French that the second plane I had hit also crashed a few miles away. I therefore claim two (2) FW190’s destroyed as a result of the above combat.

Traces of War has a contemporary view of the crash site of Morris Leve’s P-38, which is located in the municipality of Neunen.

The May 5, 2010 video “2009-12 The Steiner brothers (USA) in Nuenen (The Netherlands)” at Lokale Omroep Nuenen’s YouTube channel, presents the recollections of civilians who witnessed the loss of Lt. Leve and 38th FS pilot 1 Lt. DeLorn L. Steiner. The video is from the YouTube channel Lokale Omroep Neunen.

The video below, dating from August 18, 2011 – at the YouTube channel of Jacques Braakenburg) – appropriately entitled “The nephew of Morris Leve, the pilot who was killed in Nuenen,” shows Lt. Leve’s nephew Robert (son of Morris’ brother Sol) visiting the crash site of his uncle’s P-38. Unfortunately, the names of the gentlemen accompanying Robert are not listed.

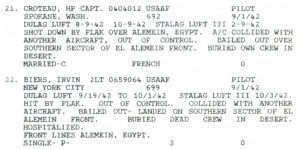

Luftgaukommando Report AV 641/44, pertaining to Lt. Leve and Lt. Steiner, is shown below. (Note that this document is of the same layout and informational format as that used to record information about Lieutenants Gilbride and Hascall.)

Born on September 25, 1921, Morris was buried at New Montefiore Cemetery, in West Babylon, N.Y., on December 5, 1948. His name appears on page 376 of American Jews in World War 2.

Born on September 25, 1921, Morris was buried at New Montefiore Cemetery, in West Babylon, N.Y., on December 5, 1948. His name appears on page 376 of American Jews in World War 2.

Here’s Morris’ matzeva, bearing his Hebrew name Moshe Bar Baruch, at Montefiore Cemetery, in a photograph by FindAGrave contributor RealistState. Note the image of the P-38 Lightning engraved at the upper left of the stone.

A P-38 is similarly engraved on Lt. Steiner’s tombstone.

Morris’ correspondence with his parents yields fascinating and moving insight into his experiences in England. His letters (Vmails, actually) touch upon such subjects as attending Rosh Hashonah services with Major Joel, his “personal” P-38, and particularly his relationship with a British Jewish family, the Kosmins, who resided at Denmark Hill in London. Her are some excerpts.

Rosh Hashanah services in Cambridge…

9/30/43 (Thursday)

Dear Mom & Pop,

Everything is still going along well & I’m feeling fine. I finally received a letter from you dated Sept. 10 & sure was glad to hear that everything is O.K. We’re all happy cause today was payday. Sure was funny being paid in English pounds. Will have a chance to spend it when I go to London again next week. I went to services [Rosh Hashanah] in Cambridge last night [September 29, Wednesday] with the Major & met some swell people. Should get some good dinner invitations etc. out of it. A home cooked meal really will be a treat.

His “personal” P-38H, the “Flatbush Flash”…

10/15/43

Dear Mom & Pop,

Am feeling fine & having a lot of fun. I can tell you a little about what’s going on now. I have my own plane which I’ve named the “Flatbush Flash”. I have the name painted on the side of my plane & will send you some pictures soon. I also have my own crew chief & armorer. They’re all good men & work hard to keep the plane in shape. I can’t tell you yet about what I’m doing but you’ll be reading about us, I’m sure. Please don’t worry about me & take care of yourselves. Regards to Sol, Henrietta, & family.

Meeting the Kosmin family and their daughter Sheila…

October 19, 1943

Dear Mom & Pop,

I just got back from another 48 hour pass which I spent in London. Had a wonderful time. I met a cute little girl who surprisingly enough turned out to be Jewish. Her name is Sheila Kosmin. I spent one evening at her home & really had a feast. Her mom gave me the best meal I’ve had since I left the States. Her folks insisted I spend the night there & I even got my breakfast in bed. I’m going back there a week from Friday on my next pass. Mrs. Kosmin promised to make “gefilte fish” & fried chicken. They’re all swell people & I’m sure lucky I met them. Give my best to Sol, Henrietta & all.

Hospitality at the Kosmins…

11/12/43

Dear Mom & Pop,

I wrote you about the packages so I’ll tell you about my pass in this letter. As I told you, I spent most of the time with the Kosmin family. I had two wonderful delicious dinners & went out both evenings with Sheila Kosmin, the 18 year old daughter I told you about. I stayed at their house both nights & had breakfast in bed both mornings. I really enjoyed myself very much the whole time. They’re all very nice to me & go to a lot of trouble for me. I’ll give you their address, & you can write them if you like.

The Kosmins resided in Brixton at 175 Denmark Hill.

Here’s a March, 2019 Oogle Street view of that address, where is presently situated a four-story apartment or condominium. I have no idea if this is the building in which the Kosmin family actually resided, or if – as evident from the architectural style of the buildings on the opposite side of the street – it was constructed after the war. But, it is the correct address.

It’s my understanding that postwar, Sheila Kosmin considered a trip to the United States to meet Morris’ parents in Brooklyn. However, that journey never took place.

________________________________________

________________________________________

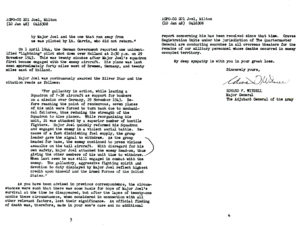

This last recollection about Major Joel is of a different sort: It’s a letter by Captain Robert W. Wood, the 38th Fighter Squadron’s Executive Officer and member of the Squadron since its formation. Captain Wood signed the “lead” page of each the four MACRs covering the squadron’s losses (Lieutenants Albino, Carroll, Garvin, and Major Joel) of November 29, 1943.

Written on January 2, 1947, a year and a half after the Second World War ended and over four years since Milton’s death, it was composed in reply to an inquiry by Milton’s father Joseph concerning the nature of his son’s death in particular, and his military career in general. Robert Wood’s thoughts are compassionate and enlightening; inspiring and comforting. Paralleling this, his letter – composed while the events of the war were still relatively fresh in memory; just over three years since Major Joel’s death, is in some respects – how else to phrase it? – quite disillusioning, especially so if the “Greatest Generation” (I’m using the quotes intentionally) is only perceived through the lenses of romanticism and nostalgia, rather than an appreciation of the often disconcerting reality of human nature.

____________________

The text of Mr. Wood’s letter follows, with images of the actual text below. This is followed by a brief discussion, where I discuss his lines of text, and of equal importance, what I believe lies “between the lines”.

Dear Mr. Joel:

Your thoughtful letter reached us just today, and I’d be a very small person indeed to put off the answer to that.

You know from Elaine that to me Milton was rather more than a Squadron Commander, he was a fine example of a true American – above all he was a man. Have you ever read any Western Stories? The heroes are always strong, silent, extremely courageous men – none of those fictional characters ever excelled “The Major” in clear thinking or in a determination to make truth and righteousness triumph. No story hero ever displayed the courage that your son did – that’s not so much blarney, I feel it is absolutely true. I’ve thought that my personal affection for “Gummy” had made his deeds more outstanding than they really were, but time and a greater knowledge of what others did have assured me that if anything I underrated his accomplishments.

His leadership and superb control of his emotions were outstanding – even though there were those who still slurringly referred to him as a Jew. These people never bothered the “The Major”. In fact he seemed glad of the chance to show them that his was a bigger soul than theirs. Here’s a little story about that that will show you what I mean. Upon arriving at our station in England Major Joel informed the Engineering Officer that the crew chief he wanted was a Technical Sgt. who I’ll just call “Shorty”. To this everyone objected and several of us asked “Gum” why he had insisted on a crew chief who had openly stated that he disliked the Major – in fact all Jews. “The Major” replied, “He’s as good if not the best crew chief in the Squadron, isn’t he?” Since this was actually so there was no further arguing that matter and your son proved to us all the truth of his claim that he didn’t care what one of his men thought of him personally as long as they did their job. Shorty crewed (by crewed I mean he took care of the airplane on the ground to make sure it was in fine mechanical condition) the Major’s airplane for 1 ½ months and during that time Shorty didn’t say anything for or against the Squadron Commander – yet, when Major Joel failed to return on that day in November 1943 Shorty broke down and cried and very nearly became a mental case. For Shorty had learned that Major Joel was above all petty likes and dislikes and that his courage and devotion to duty were unexcelled. That story may seem small to you but to me that’s just a typical example from the many such deeds of your son that placed him head and shoulders above the ordinary.

Mr. Joel you’ve asked me a question that I nor any one else can tell you much about. I was not there and neither were any of the heroes of the 55th Group, but I can give you my opinion of Milton’s disappearance. The day’s mission was a bomber escort to Bremen, Germany, and Maj. Joel was flying as Group Leader which meant that he had under his direction his own plus two other squadrons. By following his instructions “Gum” led the Group to the meeting point with the bombers just as large numbers of enemy fighters were attacking. The job of protecting the bombers looked pretty hopeless, but Joel called the bombers to tell them help had come and their answer was, “Thank God!” Gum then instructed the other squadrons of the deployment for attack. At this point a Captain in another squadron, later made a Lt. Col. and quite a hero decided that it was time to go home as the fight looked tough, so he assumed command of the Group (later told that Joel lost contact with the other two squadrons) and with the 338th and 343rd Squadrons returned to England. That noble deed was what a General like Patton would have had a man shot for, but our Group made him a brilliant and heroic pilot – what a lie! From this point Gum drove on to assist the bombers with his 16 ship Squadron, but engine trouble or cowardice caused 8 of his own Squadron’s planes to turn back. Milton and his wingman (2 planes) dove into the attack with Capt. Ayers and a wingman about 300 yards behind. This was the last that was seen of those two planes as all planes came under severe attack from the enemy. Joel’s wingman was Lt. James Garvin and he was reported killed in action on that day. Capt. Ayers kept fighting his way forward but could never catch sight of Joel, and was finally forced to turn and fight his way out of the area. The 38th Squadron lost four of the 8 ships that had courage at their controls that day. – The Capt. who deserted with 2 squadrons with his story of saving the Group, came home and no one killed him. Mr. Joel, believe me, murder was a very attractive thought to me at that time. But he was allowed to go on doing heroic deeds of this nature. I can’t remember how many times he saved his squadron after that, but on Jan. 31, 1944 he saved the day in the same manner – our Squadron lost 6 brave boys that day. And so on. The Air Corps refused to let me fly, for to them I was too old, therefore I never have had the right to anymore than think these things.

That in my opinion is actually what happened. I also had an idea Gum was active in the Underground, for he had information that he told me he dare not divulge that day before the mission. However, there should no longer be any doubt about the War Dept.’s notification. I wish I could tell you more, but there is none to tell.

There was no braver, more heroic soldier in this war than your son. His example of unselfish devotion to an ideal will always be a great inspiration and the ultimate goal for me. His wonderful insight into problems both large and small, and his superb, calculated thinking were in small measure passed on to me – for that I’ll be eternally grateful. The World would be a wonderful place if all men were of your son’s caliber. I can only thank god for the opportunity even though short that he granted me with “Gummy”.

Best wishes to you, Mrs. Joel and Elaine. Don’t think I’d not like to come to Richmond to see you swell people. Do you remember our unlucky fishing trip in Washington? Gee, I wished you could catch a big salmon.

Sincerely,

Bob Wood

P.S. Am enclosing some pictures that you may not have copies of.

Okay, here’s the actual letter:

____________________

Some comments…

In the letter’s second paragraph, Robert Wood (by 1947, no longer a Captain) describes Milton’s character as a soldier and leader of men, generally in terms of his interaction with members of his squadron, and specifically in the context of being a Jew.

In his third paragraph, Wood directly addresses what appears to have been Joseph Joel’s obvious and central question: What, actually, happened to his son on November 29, 1943?

Albeit sincere, frank, and well-meaning in his intention of informing Milton’s parents of what transpired that day, some parts of his account – particularly about Milton contacting the B-17s and eliciting a reply of “Thank God!” from them – are incorrect, for none of the 55th Fighter Group’s three squadrons actually made contact with the bombers on that mission. And, I most seriously doubt that a communication of this nature would ever have been transmitted from a bomber formation to its fighter escort.

As for Mr. Wood’s explanation of specifically why the 38th Fighter Squadron had been reduced to nearly half strength (“…engine trouble or cowardice…”) by the time it was intercepted by III./JG I? I addressed the former topic – the performance of the P-38 in the context of its (perceived) suitability for use by the Eighth Air Force – in the post A Battle in The Air, by means of excerpts from Bert Kinzey’s two Detail & Scale books about the P-38, and, Dr. Carlo Kopp’s analysis of the P-38 at Air Power Australia.

In terms of the latter topic – using the term “cowardice” to characterize the pilots who left the 38th’s formation and returned to Nuthampstead “early” – a review of the biographies of those seven pilots based on information at the 55th Fighter Group website shows the following, from which the reader can arrive at a contrary judgement. (Well, John Stanaway’s 1986 book Peter Three Eight: The Pilot’s Story does include a very pointed statement specifically about this topic.)

Lead Section

(Lead Flight)

2 Lt. Ernest R. Marcy – Element Leader (Engine Trouble)

19 missions

Returned early three times (twice from engine trouble and once from losing a drop tank)

April 1944 – Temporary Duty at Goxhill

9/7/44 – Transferred to Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron VIII Fighter Command

Survived War (Final rank 1 Lt.)

2 Lt. Robert F. Maloney – Wingman to Marcy (Unknown)

Remained in Squadron

Promoted to Captain by January 1945

2.5 victories (air)

Survived War (Final rank Capt.)

(Second Flight)

2 Lt. William K. Birch – Element Leader – Engine Trouble

10 missions

December 1943 – Promoted to 1 Lt.

12/16/43 – Killed in Action (not directly due to enemy action – probably oxygen problems and / or vertigo) in P-38H 42-67077 (Capt. Jerry Ayers’ “Mountain Ayers” / “CG * Q”)

Buried at Holy Cross Cemetery, Culver City, Ca.

High Section

(Lead Flight)

Capt. James H. Hancock – Element Leader (Engine Trouble)

2 victories (air)

3/15/44 – Crashed on take-off in P-38J 42-67811 (“CG * H”). Aircraft flipped on back and totaled by fire. Crash caused by failure of one engine. Uninjured.

Promoted to Major

Became commanding officer of 38th Fighter Squadron; Ended tour by 7/16/44

Survived War (Final rank Major)

2 Lt. Edward F. Peters – Wingman to Hancock (Engine Trouble)

Shot down 1/5/44 in P-38J 42-67650 (MACR 1746)

Survived as Prisoner of war at Stalag Luft I

(Second Flight)

1 Lt. Morris Leve – Element Leader (Blew Inner Cooler)

KIA 1/31/44 (see above and below)

F/O David D. Fisher – Wingman to Leve (Escort for Leve)

22 missions

December, 1943 – Promoted to 2 Lt.

KIA 1/31/44 (see below)

Another point: There is no evidence that Major Joel had any association with the Underground, the possibility of which was – in any event – a moot point by day’s end on November 29, 1943.

____________________

However, there are aspects of Robert Wood’s account that are correct. Lt. Garvin was killed in action (perhaps Mr. Wood learned this through the International Red Cross, or, the War Department); Capt. Ayers did attempt to provide cover to Major Joel (and Lt. Carroll, not Lt. Garvin) until forced to break off upon further attacks by III./JG 1; the 38th Fighter Squadron did lose a total of four planes that day.

And, within Mr. Wood’s account of the November 29 mission, stands an event (or, a “non-event”?) that seems to be consistent with the mission as it actually transpired.

First, the relevant text from Mr. Wood’s letter:

At this point a Captain in another squadron, later made a Lt. Col. and quite a hero decided that it was time to go home as the fight looked tough, so he assumed command of the Group (later told that Joel lost contact with the other two squadrons) and with the 338th and 343rd Squadrons returned to England.

First, compare the above statement with the following excerpt from Captain Franklin’s statement in the Missing Air Crew Report (MACR 1429) for Major Joel:

The main body of the group was proceeding toward home when Major Joel was heard calling for help from far behind us. Lt. Gilbride and I turned back to help but it took several minutes for us to reach the fight.

Second, consider this account in the Missing Air Crew Report (MACR 1272) pertaining to Capt. Franklin’s wingman, Lt. Gilbride. (I’ve broken the text into paragraphs for easier comprehension.):

At approximately 1210 hours, I reported many bandits approaching from below at 3 o’clock; this was about in the target area.

Colonel James had started a right turn to meet the enemy aircraft when we met about 16 enemy aircraft head-on at about 29 to 30,000 feet. The main body of the Group went into a right Lufberry Circle for approximately two complete turns. Colonel James was [not] leading the Group at or from this time, as he was having engine trouble and was below us.

My second element disappeared about this time as Lieutenant Bauer was having trouble losing his belly tanks. Lieutenant Gilbride stayed with me in an excellent manner, calling in enemy aircraft calmly and doing a good job of covering. The main Group stayed in their Lufberry but I would break out momentarily from time to time to get my wing out of the sun so that I could see if another attack was imminent.

About this time, after two complete turns, the main Group started home and I, thinking that the Group Commander had resumed the lead, followed along. As we left the area there were several people calling for help from far behind. The main Group continued on away until we were at least seven miles from this fight.

Just as I had almost decided to go back and help the boys calling repeatedly, the Group started a turn and appeared to be going back but instead made a tight 360 degree turn and went away from the fight again. I could see the fight behind us as the Group made the turn and I broke out – Lt. Gilbride and I went back to help.

Third, this statement by Lt. Erickson, one of the three 38th Fighter Squadron pilots who were saved through the combined efforts of Captain Franklin and Lt. Gilbride:

Captain Ayers called for help and Captain Franklin and Lt. Gilbride of the 343rd came back.

Fourth and last, a summation of this phase of the 38th’s engagement with the Luftwaffe, from the post A Battle in the Air:

Captain Franklin reported that at 1210 (probably an error, the time likely having been 1410) “many bandits” were approaching from a lower altitude in the “target area”. At that point, Group Commander Col. Frank B. James started a turn to meet the German planes. The “main body of the group” (whether by this Capt. Franklin meant the 343rd alone, or, the 343rd and 338th both, is unspecified) then went into a right Lufbery Circle.

Though Captain Franklin had by this time lost his second element, Lt. Gilbride remained with him in an “excellent manner”. The main “group” remained in the Lufbery Circle, but Captain Franklin and Lt. Gilbride would “break out” from time to time to see if another attack was imminent.

After two complete turns, the “group” started back to England.

Captain Franklin and Lt. Gilbride followed, assuming that Colonel James was leading. However, the Colonel was not: Captain Franklin specifically mentions that from this moment on, Colonel James was no longer leading the group (intriguingly, he does not specify who was…), which is consistent with the 338th’s Mission Report of the Colonel having returned to England alone.

Captain Franklin reported that as the main body of planes headed back to Nuthampstead, pilots were heard, “calling for help from “far behind us,” specifically noting Major Joel’s voice. Later, Lt. Erickson, in his own Encounter Report, mentioned that Captain Ayers was also radioing for help.

The rest of “group” continued on its way.

Then, “Just as I had almost decided to go back and help the boys calling repeatedly, the Group started a turn and appeared to be going back but instead made a tight 360 degree turn and went away from the fight again. I could see the fight behind us as the Group made the turn and I broke out – Lt. Gilbride and I went back to help.”

It took Franklin and Gilbride “several minutes” to reach the fight.

As the pair neared the 38th Fighter Squadron’s P-38s, they saw, “five P-38’s engaged and each had from one to three ME 109s on its tail. Just before we went into the fight one P-38 rolled over and went down with its left engine leaving a very long and very heavy trail of black smoke and with a 109 directly behind.” (They had witnessed the fall of either Lt. Carroll or Lt. Albino.)

Franklin and Gilbride flew directly into the midst of the gaggle, the surprised German pilots rolling and climbing away from the P-38s.

Summing up? The group went into a Lufbery, made two complete turns, headed back to England, and then started a third turn as if returning to aid the 38th Fighter Squadron. But, the turn continued for a full 360 degrees. Then – quoting Captain Franklin – the group “went away from the fight again” – by which time the 38th’s engagement with III./JG 1 was visible in the distance.

Then, Captain Franklin and Lt. Gilbride left the safety of the group to go to the aid of their comrades, from which Lt. Gilbride did not return.

____________________

I’ll not comment about Bob Wood’s characterization of the person leading the 55th Fighter Group’s “other squadron” (squadrons?) that day – whether in terms of his actions, or, his eventual “place” in the 55th Fighter Group, other than to say that while problems with the 38th Fighter Squadron’s (and 55th Fighter Group’s) P-38’s undeniably contributed to the Group’s debacle, I think leadership was an equal factor.

For if the sudden, “last moment” arrival of only two pilots saved the remnants of the 38th Fighter Squadron – after that squadron had already been intercepted by the Luftwaffe – then a question arises: What might have happened had the 38th’s brother squadrons gone back to help when calls for assistance had first been radioed?

As an astute reader of this series of posts has suggested, Major Joel died, probably thinking; probably assuming; certainly hoping (while Lieutenants Albino, Garvin, and Gilbride died too), that his squadron would receive support when needed. But, that was not to be.

____________________

Bob Wood mentioned the 55th Fighter Group’s mission of January 31, 1944. Here, it is notable that the 38th Fighter Squadron’ Mission Report for that day (presented in full below) recounts a scenario which parallels that of November 29, 1943: The “main body” of the 55th Fighter Group (this is perhaps deliberately ambiguous – does this mean the 338th and 343rd Fighter Squadrons both? – it seems to; neither squadron incurred losses that day) going into a Lufbery circle, with the 38th Fighter Squadron engaging the enemy alone, and then being numerically overwhelmed by Me 109s attacking from “all angles and altitudes”.

38th Fighter Squadron losses on January 31, 1944, comprised:

Killed in Action

1 Lt. David D. Fisher, P-38J 42-67757, “CG * C”, MACR 2106 (mentioned just above)

1 Lt. Morris Leve, P-38J 42-67768, MACR 2110, Luftgaukommando Report AV 641/44 (see above)

2 Lt. Martin B. Miller, P-38J 42-67221, MACR 2108

1 Lt. Delorn L. Steiner, P-38J 42-67711, MACR 2105, Luftgaukommando Report AV 641/44

Survived

2 Lt. Leon M. Patterson, P-38J 42-67301, “CG * Z”, MACR 2109 (Prisoner of War)

1 Lt. Leroy V. Hokinson, Jr., P-38J 42-67813, MACR 2107 (Evaded – see above)

____________________

So, here’s the verbatim text of Major Mark Shipman’s Encounter Report for the 31 January mission, which chronicles the 38th Fighter Squadron’s engagement with the Luftwaffe (I think JG 1 again; this time around its Second Gruppe) that day in great detail. Note particularly the German tactic of combining the advantages of the greater high-altitude performance of the Me 109G versus the P-38H, and simply the use of altitude per se, in combating the 38th Fighter Squadron. Paralleling this is Major Shipman’s most (* ahem *) vivid (!) description of losing all visibility as canopy froze internally when he rapidly descended from 10,000 to 2,000 feet. While the problem with cockpit heating in early versions of the P-38 has often been remarked upon in popular and technical histories of the P-38, these three sentences make something abstract very real! (The italics are my own.)

I was leading Swindle White Flight in the vicinity of Venlo when 15 smoke trails were sighted at approximately 30,000 ft. or 12,000 ft. above us. At the time we had about 48 P-38’s with us, but all we could do was to start spiralling up to their altitude. With this action, the E/A, later proved to be Me109’s, started losing altitude slightly, but at all times keeping their forces above our own, usually with about 3 to 4,000 ft to spare. As we gained altitude they also went up, until some 15 minutes later we were at about 30,000 ft. with some eight, and with the corresponding difference in altitude between us and the E/A. During this time the Me109’s kept making passes at us when the opportunity was present, but with each pass they would zoom back up to their original altitude. Never at any time did they send down more than 5 at one time, so that during the entire engagement there were always E/A above us. All had rounded wing tips and were painted a shiny silver color.

As stated, during the whole engagement the E/A stayed above us even though we did try to get to their altitude. At one time, about ten minutes after we sighted them, one E/A made a bounce on a P38 so I started after him, closing to about 600 yards. At that time he half-rolled, and since I was still intent on trying to get above the rest of the E/A I did not follow him down. I did not see any strikes on him, but when last sighted he seemed to be somewhat out of control. As stated, I make no claims pending assessment of the combat films.

At this time it was evident that all we were doing was running ourselves out of gas, so I called and told everyone to start home. I tried to get an eight ship section together, but with all the confusion it was not successful.

About that time, when there were then only seven of us left in the area, I looked back and saw eight E/A behind us, four coming in from the right, and five above us so I called and told everyone to hit the deck from our altitude of approximately 18,000 ft. Obviously it was hopeless for us to try to fight our way out with them so down we went with full power. At about 10,000 ft. I got a violent buffet in the ship and had to pull back on the throttle. Then, as we got lower the entire canopy started to ice up from the inside. At around 2000 ft. it got so bad that I absolutely couldn’t see where I was going so all I could do was to level off by the altimeter. After some hectic five minutes of wiping with my gloves I managed to get most of the ice off, at least enough that I could see where we were going; so we went on down to the deck and started home. There was a heavy haze layer at two thousand feet which helped to conceal our position from E/A and so far as I could tell none of those in the engagement area tried to follow us down. At the time when I called to hit the deck the eight E/A in back of us had their backs turned, trying to get around the circle and chase us and the five above us were too high to see us once we started for the deck. As for the four on the right I couldn’t be sure, but I can’t believe an attempt was made to follow us down.

Obviously, the tactics of the E/A were to keep us in there with their limited number of aircraft, try to get the group scattered and then bring in a fresh force. In this attempt they succeeded indeed for when I last looked back there were certainly a lot more E/A than there were to begin with. All the ships were painted with the same colors, and were piloted by a smart bunch of Jerries.

____________________

Finally, here’s an excerpt from the Squadron’s Mission Report for that day; a reproduction of which follows:

Mission: Landfall Onerflakee at 1456 at 22,000 feet, Nelvo at 1615 at 22,000 feet. Out Ostend area at 1625 deck to 18,000 feet. Group of P-47’s sighted at 2 o’clock flying northwest near Asten at 1512. Two squadrons of P-47’s observed enroute to bombing target at coast by Captain Hancock returning shortly before rest of Group. Made port turn at Venlo. Main body of group flattened out and formed a luftberry, Major Shipman led the 38th up into the enemy aircraft, Major Shipman finding himself out numbered by enemy aircraft, gave the order to return on the deck. Some of the squadron returned with the main body of the group, others followed Major Shipman order. Landfall out vicinity Ostend at 1625, deck to 18,000. (Flight Plan Attached).

Action: On southern leg of triangle contrails first sighted approaching high in the distance from 10 o’clock. After making port turn at Venlo these were identified as 13 ME 109’s flying in flights of four. Group started turning and climbing to meet attacks, but enemy aircraft went up with them until latter were at an altitude of 32,000 feet. As main body of group flattened out and formed a luftberry, Major Shipman led the 38th up into the enemy aircraft. In the ensuing engagements, the tactics of the Hun were to send down sleepers to break up the friendly formation, and the reason was soon evident. At approximately 1545, 30 plus additional ME 109’s attacked from all angles and altitudes.

The Mission Report:

________________________________________

As I mentioned in prior posts, of Milton’s writing, only a single V-mail letter and a few diary entries have survived, for Elaine destroyed her first husband’s letters before she passed away in 1981. Perhaps likewise for Milton’s military papers? His pilot’s flight record survived the war and was given to his parents, but whatever became of that document and the small myriad of other records associated with his military service is unknown.

But, something else has remained: Two letters that Milton sent to the Richmond Times-Dispatch while still a teenager; a few years before he entered the military.

This letter, from May 12, 1939, written six months after Kristallnacht, concerns the admittance of refugees to the United States, specifically within the criteria of American law according to the Immigration Act of 1917. In the latter part of the letter, Milton specifically focuses on refugee physicians, obviously as this pertains to German Jews. Though the word “Jew” does not appear in his letter, his concerns and focus are obvious.

At 19 years of age, here is no question that Milton Joel was cognizant of what was confronting the Jewish people.

The Founding Refugees

Editor of The Times-Dispatch:

Sir, – Recently you published a letter regarding refugees seeking haven within our shores. That letter expressed a type of sentiment which I believe warrants some serious criticism. Following much the same illogical course as do the opinions and propaganda of such questionable patriots as Senator “Bunkum Bill” Reynolds and his vigilantes, the writer suggests that we should lock our nations’ gates to all foreign refugees.

Our republic’s very foundations were built by refugees. As many as eight of the signers of the Declaration of Independence were men in that category and many other of the signers were the sons or more distant descendants of those who had come here to escape religious or political persecution in other lands. Many greater heads than mine have contended that the success and perseverance of our democracy and the concepts of liberty and freedom, which prevail in it, can be attributed to the fact that the great mass of our citizens grew out of an ancestry which knew an opposite sort of life.

The most often quoted argument of the antialienists, is that we have enough of our own public charges without importing more. On the surface this is a logical argument; however, a look at section three of the Immigration Act of 1917 will refute it. This section provides that “persons likely to become a public charge,” in order to receive a visa, must furnish appropriate evidence that he will have sufficient assurance that he will not become a public charge.” The applicant must show that either he has sufficient funds to be self sustaining or furnish an affidavit by which a sponsor takes complete responsibility of his not becoming a “public charge.” The sponsor, in addition, must himself prove that he is financially able to accept that responsibility. The above applies to all immigrants, save those from nations in this hemisphere, and professors and ministers of a religious faith, who desire to enter the country for the sole purpose of carrying on such vocations.

In a recent 12-page pamphlet, sent to all physicians, among other things the senator from North Carolina makes an attempt to show that the medical profession is being seriously threatened by an exaggerated influx of refugee doctors. It is, however, an established fact that rural United States has a crying need for medical men. Rural districts in this country have ample room for more physicians than the demigods of Europe can chase out.

Moreover, to top off the whole matter, our nation has had a negative immigration since 1932, wherein there were more people leaving our shores permanently, than entering. The United States has nothing to lose and everything to gain by humanely offering shelter to minds and bodies which are strong enough to be feared by Europe’s authoritarian states.

MILTON JOEL

____________________

This letter, from December 8, 1939, of a much lighter and perhaps paranormal (!) sort, reveals something a little extra-ordinary: Milton’s curiosity about extrasensory perception, or at least its possibility. Co-authored with fellow University of Richmond Psychology Club officer Austin Griggs, this communication to the Times-Dispatch was itself inspired by a letter by Richmond resident Gaston Lichtenstein, Richmond resident and “researcher, writer, and historian”, whose interests focused on Southern history (his father presumably having served in the Confederate military), and, the history of the Jews of Richmond.

For E.S.P. Please R.S.V.P.

Editor of The Times-Dispatch:

Sir, – Gaston Lichtenstein’s recent letter interested us considerably. This matter of extrasensory perception has been frequently discussed by our Psychology Club hero at the university, and our laboratory has even conducted elementary experiments in this parapsychological field.

Perhaps we might be able to cooperate with Mr. Lichtenstein in testing his psychical powers or those of any whom he might recommend, in order that we might come to some conclusion as to the reality of this mystical phenomenon. We possess the standard parapsychological equipment, and feel that the experiments should prove Interesting to Mr. Lichtenstein or any of his friends.

While we are not ready to admit the absolute plausibility of Rhine’s [Joseph Banks Rhine] theory, and therefore hold some doubt as to the scientific merits of the cases sighted by Mr. Lichtenstein and most others whom we have contacted to date, we stand ready to be convinced and therefore can promise to be unbiased in our testing of any interested party.

AUSTIN GRIGGS

MILTON JOEL

Executive Officers, University Richmond Psychology Club, Box 17, University of Richmond

________________________________________

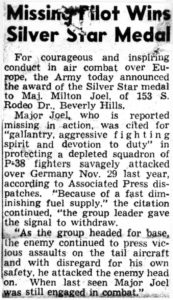

Many names have been mentioned in this series of posts. But, in terms of the mission of November 29, 1943, the most notable is obviously that of Captain Rufus Clarence Franklin, Jr.. Though (fortunately?!) I’ll never have to adjudicate military awards, it seems that he more than deserved at last some kind of recognition – a Silver Star? – for leaving the formation of the 343rd Fighter Squadron with Lt. Gilbride (who was killed for his bravery) and turning back to go to the aid of the beleaguered pilots of the 38th Fighter Squadron. But, in the context of the events of that mission, such recognition would have been impossible: Two Silver Stars in one Fighter Group, for the same mission? Given the circumstances of what actually transpired on November 29, such an award would inevitably have required an explanatory citation which in turn could have been the impetus for a complete and honest explanation of the day’s events. Perhaps it was better just to move on.

Thus for Captain Franklin’s participation in the events of the 29th of November.

He would be promoted from Captain to Major in February of 1944. On the 23rd of that month, after having been a member of the 343rd Fighter Squadron since February 1, 1943, he would be transferred to the 79th Fighter Squadron of the 20th Fighter Group, where I believe he spent the remainder of the war. Postwar, he remained in the Army Air Force and in turn the United States Air Force, ultimately being promoted to Colonel by 1955.

Given his skill as a fighter pilot, physical bravery, sense of responsibility (so amply demonstrated on November 29), I find this to have been very strange. He would by early 1944 – and probably earlier – have become invaluable as a pilot and leader of men. Which begs the question: Why would a person of such skill, embodying such qualities, be transferred out of his squadron, given that he’d probably by this time become solidly integrated into the unit, and, doubtless knowledgeable of the strengths and weaknesses of his fellow pilots, let alone the squadron’s operations and activities as a military unit?

I can only offer conjecture: Could Captain Franklin’s departure from his squadron have been because, and not in spite, of his obvious value as a combat pilot, let alone – and this I think may be critical – the singular independence of thought, action and leadership he demonstrated on the 29th of November? The answer, perhaps, could be best addressed in terms of fiction, for fiction has its own way of elucidating fact.

Some images of Rufus C. Franklin, Jr., appear below.

When other men went in one direction, he went in another: He looked back to where help was needed, and gave that help.

____________________

Rufus C. Franklin, Jr., as a Flying Cadet, from the American Air Museum in Britain.

– Rufus C. Franklin, Jr., probably as a Lieutenant or Captain, in the cockpit of a P-38G or H Lightning. The plane is identifiable as such by its canopy configuration, most obviously the pane of armored glass mounted below the windshield. In Lightnings from the “J” version on, the canopy was redesigned to incorporate armored glass as the central, forward window. (This image also from the American Air Museum in Britain.)

– The Captain has become a Major: Rufus C. Franklin, Jr., serving in the 79th Fighter Squadron, 20th Fighter Group, in front of his P-38J 42-68037 “Strictly Stella’s Baby” / “MC * F”. The aircraft was presumably named after Major Franklin’s wife (or girlfriend or fiancee?): Stella. (American Air Museum in Britain photo UPL24002.)

–

– Standing before his F-86 Sabre Jet, Colonel Rufus C. Franklin, Jr., and Airman 1st Class Juxor Carr, possibly photographed when Franklin commanded the 4520th Combat Group Training Wing. (Photo UPL 23998 from American Air Museum in Britain)

–Born in 1921, Colonel Rufus Clarence Franklin, Jr., passed away at the very young age of 48 in July of 1969. He is buried at Del City, Oklahoma. During the war and especially (especially!) after he received nowhere near the attention of some other pilots (and another pilot) he served with, but that is “in the way of the world”. Then again, there have always been other scales in which the deeds of men are measured. And, remembered.

The memory of man is ever fickle and fleeting, but there are other forms of memory, that even if silent, are permanent.

________________________________________

Sometimes, the nature and outcome of a man’s life – and the impact he leaves upon those around him – makes sense only in retrospect: after the fact. Sometimes life confronts us with situations that on the human scale; that on any honest scale – whether intuitive or intellectual; whether in terms of morality and justice – are by any understanding simply unfair; simply not right; simply unamendable to reason.

For some situations and events, we can only have questions, and for some questions, we can only answer in silence. But perhaps in its own way, that silence provides its own answer. Well, one would hope so.

When I learned about Major Joel’s story, I could not but be be struck by the inherent unfairness of the tale: A husband and wife, at a point in their lives when children no longer seemed a possibility, were blessed with a son who would be their sole progeny. Their son grew into a man of great potential, in terms of intellect and leadership; courage and promise.

And, then their son was taken from them.

And then, their son would never have a place of burial.

And here, I am reminded of the tale of Rabbi Meir (one of the Rabbinic sages who lived during the time of the compilation of the Mishnah) and his wife Beruriah, from the Midrash Proverbs 37 (76-29). To quote the Jewish Encyclopedia, “This story, which has found a home in all modern literatures, can be traced to no earlier source than the Yalḳuṭ [13th century]. (Prov. 964, quotation from a Midrash).”

The tale follows:

The most touching and most famous story about the piety,

wisdom and courage of Beruriah describes the death of her two beloved sons.

One Sabbath while Rabbi Meir was in the Beth Hamidrosh,

sudden sickness struck their children and they passed away before anything could be done for them.

Beruriah covered them up in the bedroom and did not say a word to anyone.

After nightfall Rabbi Meir returned from the House of Learning and asked for his sons.

Casually, Beruriah remarked that they had gone out.

She calmly prepared the Havdalah, the cup of wine, the light and the spices.

She also distracted him while she prepared and served the Melaveh Malkah,

the evening meal with which a Jew accompanies the departing “Sabbath Queen.”

Then, after Rabbi Meir had finished eating,

Beruriah asked him for an answer to the following problem:

“Tell me, my husband, what shall I do?

Some time ago something was left with me for safe-keeping.

Now the owner has returned to claim it.

Must I return it?”

“That is a very strange question indeed.

How can you doubt the right of the owner to claim what belongs to him?”

Rabbi Meir exclaimed in astonishment.

“Well, I did not want to return it without letting you know of it,” replied Beruriah.

She then led her husband into the bedroom where their two sons lay in their eternal sleep.

She removed the bedcovers from their still bodies.

Rabbi Meir, seeing his beloved sons, and realizing that they had passed away, burst out into bitter weeping.

“My dear husband,” Beruriah gently reminded him.

“Didn’t you yourself say a moment ago that the owner has the right to claim his property?

G‑d gave and has taken away; blessed be the name of G‑d.”

Milton Joel was one of the several hundred Jews who served as fighter pilots in the aerial arms of every one of the major (and some “minor”) Allied combatant nations in the Second World War. May this account this account stand for all of them: All who were killed or missing in action, and all who survived. Those who are known, and those who are unknown.

________________________________________

Having come to the end – for now – of the story of Major Milton Joel, there are many other subjects I hope to address here, at TheyWereSoldiers. But (? – !) for the time being, I plan to return to my other blogs – WordsEnvisioned, ThePastPresented, and TheVisibleWorld – to bring you images, imaginations, investigations – and a thought or two (or three or more?) – of another nature.

Next: Part XI – References (No pictures, just lots of citations and links.)