Though information about the service and experiences of Jewish soldiers of the United States and British Commonwealth countries during the Second World War is readily available in print, archival, and digital formats, a very wide variety material exists covering what is perhaps the less widely known service of Jewish soldiers in the armies of other Allied nations.

Significant in this sense was the role of Jewish soldiers – both as refugee volunteers, and citizens – in the armed forces of France. Though not covered as systematically as in such books as American Jews in World War Two, the superb two-volume Canadian Jews in World War Two, or Henry Morris’ We Will Remember Them, or even – ironically – the two books covering military service of French Jewish soldiers during “The Great War” (Les Israelites dans l’Armée Française, and, Le Livre d’Or du Judaïsme Algérien – 1914-1918) other sources allow identification of French-Jewish soldiers (casualties, and those who received military awards) of the Second World War.

These are 1) Livre d’Or et de Sang – Les Juifs au Combat: Citations 1939-1945 de Bir-Hakeim au Rhin et Danube, 2) Au Service de la France, 3) le combattant volontaire juif 1939-1945, and, databases found at the website of France’s Secrétariat Général pour l’Administration (SGA).

Au Service de la France, and, le combattant volontaire juif 1939-1945, were published in 1955 and 1971 respectively, by the Union des Engagés Volontaires et Anciens Combattants Juifs 1939-1945 (Union of Military Volunteers and Jewish Veterans of 1939-1945).

Au Service de la France is essentially a photographic anthology covering various aspects of Jewish military service and armed resistance against the Germans during the Second World War. It encompasses military service in 1940, the experiences of prisoners of war, activity in the Resistance, and – consistent with its 1955 publication – social services for Jewish veterans and their families, as well as action against antisemitism.

An invaluable aspect of this book is the presence of lists of names of French Jewish servicemen who received military awards, or, who were killed in military service.

Le combattant volontaire juif 1939-1945 (The Jewish Volunteer Combattant – 1939-1945) was published in 1971, “…on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the Union of Military Volunteers and Jewish Veterans of 1939-1945”, and is significantly different from Au Service de la France. The text is in French and Yiddish (as a single volume) and though many photographs are present, text takes significant priority over images. However, unlike Au Service de la France, the book does not include lists of casualties or recipients of military awards.

Some years ago, I was very fortunate to have been given a copy of Le combattant volontaire juif 1939-1945 through the kindness and generosity of Mr. Albert N. Szyfman of the U.E.V.A.C.J.-E.A. (Union des Engagés Volontaires, Anciens Combattants Juifs 1939-1945 – leurs Enfants et Amis). (Thank you again, Albert!)

____________________

Realizing the importance of these two books – especially the text of Le combattant volontaire juif – in learning about the military service of French Jews during the Second World War, I’ve translated the context of the latter to English.

The purpose of the book is very well stated in its Foreword. Namely:

“AS part of the preparation of the celebrations of the 25th anniversary of the Union of Military Volunteers and Jewish Veterans, our management had initially planned to publish a special issue of “Our Will” which was to trace the activity of Union during the past quarter century.

“This project, practically limited to the history of our activities, was finally abandoned. The Committee took the view that it was necessary to reserve an important place to the testimonies and memories to boldly highlight the massive participation of Jews of foreign origin in the battles of World War II and their contribution to victory of the Allies over Nazi Germany.

“So this is the book that we present to the reader.

“While certain works, concerning this terrible time, tend to portray that the Jews could be lead to death without resistance, our book highlights in largely unpublished stories the courageous battles experienced by these men and women, with or without uniforms, alongside their French brethren.

“It would have been inconceivable that in a book edited by Jewish veterans that the horrible result of Nazi crimes, the extermination of tens of millions of human beings – including six million Jews – as it is only natural that this book speaks of the great historical event of the creation of the State of Israel and the solidarity that the Jewish veterans manifested in this regard.

“Dozens of former prisoners of war, internees in concentration camps, former resistance fighters who fought in the ranks of the F.F.I., survivors of Auschwitz and its crematoria, each, recount living episodes.

“These stories that trace, in most cases, often heroic acts, the testimonies of military leaders who commanded units with a high proportion of Jewish immigrant volunteers, the pages writers were willing to offer us for this work – all of this constitutes a somewhat original anthology.

“The reader will find in the following pages of text and illustrations covering our affairs during the twenty-five years of the existence of our Union such as the rights of veterans, the ongoing effort to preserve the memory of our dead, the struggle for peace, against racism and anti-Semitism, a just and lasting peace between Israel and its Arab neighbors, and our social work.

“One third of the book is written in Yiddish; for many of our comrades, indeed, Yiddish was the mother tongue as it was for most of the six million Jews exterminated by the Nazis.

“We are certain that in the pages of “The Jewish Volunteer Combatant 1938-1945” each member of our generation will be found, while youth will learn the nature of the last war that created immeasurable suffering.”

The book’s editorial board comprised Isi Blum-Cleitman, Dr. Samuel Danowski, Joseph Fridman, Bernard Pons, and Maurice Sisterman, in collaboration with Louis Gronowski.

Its content was supplemented by information and documents provided by the following organizations:

The Office of Decorations of the Ministry of National Defense

The Historical Committee of the Second World War

The Center for Documentation of Contemporary Jewry

The Center for Documentation of Jewish Resistance and Mutual Aid

The Israel Tourism Office

The National Association of Veterans of the French Resistance

Le combattant volontaire juif – 1939-1945 is subdivided into five major sections. These are 1) “Foreign Volunteers”, 2) “Remembrances of War”, 3) “In the Concentration Camps”, 4) “In The Ranks of the F.F.I.”, and, 5) “After the Liberation”.

____________________

In effect and intent, Le combattant volontaire juif – 1939-1945 is not an all-encompassing and minutely detailed and heavily-footnoted history. Rather, through numerous vignettes by a variety of authors, it presents – through vivid prose and great detail – an account of military service and anti-German armed resistance by French Jewry during the Second World War.

Every such account is worthy of commentary and contemplation.

An especially moving story is “Deux parmi d’autres” – “Two Among Others”, by Ilex Beller, who was President of the U.E.V.A.C.J. between 1986 and 2004.

Beller’s story covers the life and fate of Srul and Golda Magalnic, both of whom were from Rumania.

The story is presented below, in French and English.

______________________________

deux parmi d’autres

Ilex Beller

Pendant trois semaines, nous avons manœuvré dans le camp de Larzac. Nous n’avons rien appris de nouveau mais ça a été une occasion d’être débarrassé des puces barcaressiennes, d’habiter comme de vrais soldats dans une véritable caserne, de dormir sur de vraies paillasses.

Pendant trois semaines, nous avons manœuvré dans le camp de Larzac. Nous n’avons rien appris de nouveau mais ça a été une occasion d’être débarrassé des puces barcaressiennes, d’habiter comme de vrais soldats dans une véritable caserne, de dormir sur de vraies paillasses.

En comparaison avec les conditions de vie de Barcarès, les manœuvres ont été pour nous une sinécure.

Mais un ordre est arrivé de retourner à Barcarès; nous refaisons rapidement les bardas et reprenons la route.

Il pleut de nouveau et c’est tout trempés que nous montons dans les wagons à bestiaux. Arrivés à Rivesaltes, nous en descendons et parcourons à pied les 16 kilomètres qui nous séparent du camp. Mais ici une surprise nous attend: dans les rues voisines de la gare se tiennent nos camarades de Barcarès, les 3 000 volontaires du 21e Régiment qui y attendent le train en partance pour le front.

Ils sont habillés de neuf, avec de longs manteaux et des casques de fer. Seuls les bardas et les ficelles n’ont pas changé. On reconnaît à peine leur visage.

La permission nous est accordée d’aller prendre congé de nos camarades qui partent. Alors des groupes se forment à nouveau, comme à Barcarès, un “cercle juif”. On examine les nouveaux uniformes, on frappe sur les casques neufs, on se force à rire, à blaguer, mais ça ne colle pas; quel que chose a changé. Sur tous les visages se lit le même sérieux. “Qui sait, c’est peut-être la dernière fois que je vois mon camarade.”

Le moment de la séparation est arrivé. On s’embrasse. Les soldats du 22e Régiment et ceux du 21e qui partent pour le front. Les visages mal rasés sont tristes: “Fort Gesund”, “Partez en paix, chers camarades!”

Autour de nous, les habitants de Rivesaltes ont le visage préoccupé et triste, comme nous.

Nos camarades sont entassés dans les wagons à bestiaux. Ce sont les derniers serrements de mains, les dernières recommandations:

– Battez les fascistes!

– Sauvez votre peau!

– Josel, s’il m’arrive un malheur, pense à ma mère!

Le train s’ébranle lentement, Je revois Srolek agiter un mouchoir: “Au revoir! n’oublie pas Gol-dale et l’enfant!”

Le 21e Régiment (R.M.V.E.) est parti vers le front d’Alsace, occuper les positions devant la ligne Ma-ginot, dans la région de Minersheim et Alteckendorf. Il a été rattaché à la 35’ division et placé sous les ordres des généraux Decharme et Delais-sey, prenant ainsi la relève du 49’ Régiment d’Infanterie.

***

Printemps 1940. C’est le plus beau mois de mai. Les premières jonquilles dorées fleurissent dans les vertes prairies.

Les hirondelles volent bas et s’amusent parmi les soldats, les cigognes regardent autour d’elles, perchées sur les hautes cheminées des beaux villages alsaciens.

Hitler a déclenché la grande offensive. La puissante armée allemande, pourvue d’un matériel de guerre effroyable, se met en marche à travers la Belgique, contre la France. Les premiers villages français sont ensanglantés avant d’être conquis.

Les trois régiments de volontaires étrangers, formés à Barcarès, sont relevés des positions où ils se trouvaient, pour être lancés dans les secteurs les plus menacés:

– le 22’ régiment dans la Somme (la bataille de Péronne);

– le 23’ régiment dans la région de Soissons;

– le- 21’ dans les Ardennes.

Les avions allemands ne quittent pas le ciel. Ils bombardent les routes, les ponts et les gares.

Le 21’ régiment se déplace avec grande difficulté, voyage en train, en camion et marche beaucoup à pied. Il fait chaque jour des dizaines de kilomètres.

Il n’est pas facile de marcher, chargés de pioches, de pelles, de la musette, et le dos ployant sous le barda, le tout relié par des ficelles (les autres régiments nous appelaient “Régiment ficelle”; il y a les lourds fusils de 1914 aussi…

On se prépare à une guerre des tranchées et il faut creuser des centaines de kilomètres…

On s’approche des Ardennes. L’itinéraire passe par Longchamps, Chaumont, Erize-la-Grande, après Sainte-Ménéhould, Cernay, le Morthome, jusqu’aux environs du village de Boult-aux-Bois. Là, on s’arrête dans le petit bois, non loin du village, et on se trouve face à l’ennemi.

Le village de Boult-aux-Bois est occupé par les Allemands, les nôtres regardent vers les maisonnettes toutes blanches, avec les toits de tuiles rouges, entourées de champs resplendissant de toutes les couleurs.

C’est ici, dans les petits bois que la compagnie de Srolek, la “C.A.1”, va livrer sa première bataille. Les nôtres, bien qu’épuisés par une longue marche, occupent rapidement les positions de combat. Les Allemands commencent par bombarder le bois avec leur artillerie; les bombes explosent de tous côtés, criblent la terre, et projettent en l’air les troncs des arbres. Puis ils attaquent, couverts par le feu des mitrailleuses lourdes. Nous comptons nos premiers morts.

Voici un camarade avec lequel tu as vécu, que tu aimais comme ton frère, il gît ensanglanté dans tes bras, et te confie sa dernière parole… toi, tu dois partir et l’abandonner pour toujours…

Ce fut un combat bref mais sanglant, les nôtres furent obligés de se retirer. Le lendemain, le bataillon occupait de nouvelles positions dans le village des Petites-Armoises, on creusait des trous individuels, on installait le canon 25, et les mortiers, on se fortifiait.

Les Allemands attaquent tous les jours et souvent la nuit, mais les nôtres arrivent à tenir les positions, et cela va durer 12 jours et 12 nuits.

C’est le 10 juin seulement que l’ennemi réussit à percer nos lignes sur les deux flancs.

Nous sommes alors menacés d’encerclement. Aussi, l’ordre est-il donné de se replier sur Vaux-lès-Mourons, Longueval, Vienne-la-Ville, jusqu’à Sainte-Ménéhould.

Le général Delaissey vient personnellement visiter le bataillon: il faut couvrir la retraite du gros de l’armée. Il faut tenir à tout prix Sainte-Ménéhould.

Le bataillon se fortifie autour de ce village. Il fait sauter les ponts de l’Aisne qui coule à proximité, on creuse des tranchées près des lignes de chemin de fer. sur les places des villages.

Les Allemands attaquent le lendemain avec un armement lourd et puissant et s’engage une bataille acharnée, inégale. Ils réussissent à passer la rivière et foncent avec leurs autos blindées sur le village, détruisent le seul canon 25 et les deux mortiers que le bataillon possédait.

13 juin. Le bataillon a perdu presque la moitié de ses effectifs. Dans l’après-midi, le capitaine La-garigue donne l’ordre de se replier. Le groupe des mitrailleurs où se trouve Srolek Magalnik reste sur place pour couvrir la retraite.

Les Allemands ont déjà occupé tout le village de Sainte-Ménéhould, mais près du cimetière, une vieille mitrailleuse française “Hotchkiss” tire encore.

A 16 heures, une balle allemande a traversé le cœur de Srolek et a mit fin à se jeune vie. Il est tombé à Sainte-Ménéhould, en défendant le sol français dont il a tant rêvé et auquel il a voué un véritable amour.

Le lendemain, des réfugiés, des paysans, l’enterrent sur le lieu même où il a donné son dernier souffle.

Ils n’ont pu déchiffrer son nom sur ses papiers militaires criblés de balles…

Le même jour se déroule la bataille de la Grange-aux-Bois, où sont tombés tant des nôtres.

Le régiment se retire en combattant jusqu’à Passavant et puis à Robencourt-aux-Ponts, et Chau-mont qui est en flammes.

Le 19 juin, ce qui reste du 21e Régiment se bat toujours à Colombey-les-Belles, et le 20 juin a lieu la sanglante bataille devant Allain.

Le 21 juin l’ordre arrive de l’état-major de cesser le combat, de détruire les armes.

Les Allemands occupent toute la région, désarment les régiments, promettent aux officiers de les traiter en “prisonniers d’honneur” et de leur accorder le droit de porter leurs armes personnelles…

Le 22 juin, jour où le maréchal Pétain signe l’armistice et livre la France à l’ennemi, le vieux général Decharme, chef de la 35’ Division (dont faisait partie le 21” R.M.V.E.) donne son dernier ordre.

Il ordonne de réunir tous les soldats rescapés du 21’ Régiment dans le village de Tuillier-les-Groseilles. A 15 heures de ce même jour, il passe en revue les rangs des soldats sans armes, les habits déchirés et les visages ensanglantés. Il marche lentement, s’arrête souvent, regardant les soldats droit dans les yeux, il sait sans doute ce qui les attend! Puis il fait ses adieux:

“Je vous remercie pour votre héroïsme, pour votre abnégation, pour votre discipline, en mon nom personnel et au nom de la France.”

Le 23 juin, le reste du régiment est amené en captivité en Allemagne.

Le commandant de la C.A.1. (la Compagnie de Srolek) était le lieutenant Belissant, un homme cultivé et doux, qui aimait ses soldats, lesquels l’adoraient.

C’est un de ces Français pour qui les idéaux de la grande Révolution française sont chose sacrée, un de ceux qui ont contribué dans le monde entier à bâtir le renom de la France, comme pays de justice et d’humanité.

Le lieutenant Bellissant aimait beaucoup Srolek, et lorsque Srolek tomba, il pleura à chaudes larmes.

Dans la première lettre qu’il écrivit de captivité à sa femme, il dit: “J’avais un ami très cher, un Juif émigré de Bessarabie, il est tombé en héros. Je sais qu’il a laissé une femme et un enfant à Paris. Trouve-les et tâche de les aider.”

***

Dure était la vie pour Goldale et son enfant dans ce Paris affamé, occupé par les Allemands.

Elle avait trouvé une petite chambre dans une vieille maison de la rue des Gravilliers, y avait transporté sa machine à coudre et travaillait illégalement pour gagner de quoi nourrir elle et sa fille.

Elle vivait continuellement dans la peur, et pleurait chaque nuit Srolek qui était tombé “quelque part en France”.

Mme Bellissant était une brave femme, digne de son mari. Dès qu’elle reçut la lettre de son mari en captivité, elle se mit à la recherche de Goldale. D’une adresse à l’autre, elle grimpait les étages, visitait les mansardes, jusqu’à ce qu’elle trouvât la chambre de la rue des Gravilliers.

Les deux femmes firent vite connaissance et devinrent bientôt amies. Goldale se confia à elle comme à une mère. C’est Mme Bellissant qui retrouva la tombe de Srolek dans le cimetière de Sainte-Ménéhould. Elles partirent ensemble poser une dalle sur la sépulture.

C’est aussi Mme Bellissant qui trouva la vieille concierge de la rue de Rennes, Mme Grimaud, pour cacher chez elle la fille de Goldale, Nelly, et la soustraire ainsi aux rafles allemandes.

***

Cela se passa au début de 1944, par une grise matinée d’hiver, le jour commençait à peine à poindre. Paris dormait encore lorsqu’on entendit dans l’escalier de la vieille maison de la rue des Gravilliers les pas lourds des bottes militaires, les coups frappés brutalement à la porte et le cri: “Ouvrez!”

Avant que Goldale n’eût le temps de descendre du lit, ils enfoncèrent la porte. J’aurais tellement aimé vous dire que c’était la Gestapo ou d’autres formations militaires allemandes organisant la chasse aux Juifs à Paris, qui vinrent arrêter Goldale. Malheureusement, la réalité est tout autre. C’étaient des Français; oui, il s’est trouvé des Français, des âmes vendues qui collaborèrent avec les Allemands, des fascistes déments… ou bien des gens des bas-fonds.

Goldale, en chemise de nuit, maigre, malingre, toute tremblante, essaya d’abord de les raisonner: “Laissez-moi tranquille, mon mari est tombé pour la France, j’ai un petit enfant!”

Lorsqu’ils l’entraînèrent de force dans l’escalier, Goldale se débattit. Elle criait au secours, elle les injuriait, elle pleurait et, finalement, se mit à supplier: “Je n’ai fait aucun mal, je suis une pauvre couturière, laissez-moi tranquille.” Deux grands gaillards s’emparèrent d’elle et l’emportèrent.

Les voisins sortirent, en chemise de nuit, le visage gonflé de sommeil, pour la plupart des vieillards, des femmes et des enfants amaigris, épuisés par quatre années d’occupation.

Plusieurs d’entre eux se tordaient les mains et pleuraient, regardant emporter notre Goldale dans la voiture de la police.

On la déporta de Drancy à Auschwitz, d’où elle n’est jamais revenue…

________________________________________________________________

____________________________ ****** _____________________________

________________________________________________________________

Two Among Others

Ilex Beller

For three weeks we have been active in the Larzac camp. We have learned nothing new but it was an opportunity to be rid of “Barcaressiennes lice”; to live like real soldiers in real barracks, sleeping on real mattresses.

For three weeks we have been active in the Larzac camp. We have learned nothing new but it was an opportunity to be rid of “Barcaressiennes lice”; to live like real soldiers in real barracks, sleeping on real mattresses.

In comparison with the living conditions in Barcarès, maneuvers have been our sinecure.

But an order came to return to Barcarès; we quickly deploy weapons and hit the road.

It’s raining again and all are wet as we get into the cattle cars. Arriving at Rivesaltes, we descend and traverse the 16 mile walk that separates us from the camp. But here a surprise awaits us; in the streets around the station stand our comrades from Barcarès, 3,000 volunteers of the 21st Regiment await the train bound for the front.

They are dressed with new long coats and iron helmets. Only our weapons and threads have not changed. We barely recognize their faces.

Permission is granted to us to take leave of our comrades who are departing. Groups form again; as in Barcarès, a “Jewish circle.” We examine the new uniforms, knock on new helmets; we might laugh, joke, but it does not remain; regardless, things have changed. On every face one reads seriously. “Who knows, maybe this is the last time I see my friend.”

The time of separation happens. We kiss. Soldiers from the 22nd Regiment and the 21st; those who leave for the front. The unshaven faces are sad: “Fort Gesund”, “Go in peace, dear comrades!”

Around us, the inhabitants of Rivesaltes were concerned about the atmosphere and sad, like us.

Our comrades are crammed into cattle cars. These are the last handshakes, the last admonitions:

“Defeat the fascists!”

“Save your skin!”

“Josel, if I encounter misfortune, think of my mother!”

The train moves off slowly; I remember waving a handkerchief to Srolek: “Goodbye! Do not forget Goldale and the child!“

The 21st Regiment (R.M.V.E.) went to the Alsace front, occupying the positions to the Maginot Line, in the region of Minersheim and Alteckendorf. It was attached to the 35th Division and placed under the command of Generals Decharme and Delaissey, thus taking over from the 49 Infantry Regiment.

***

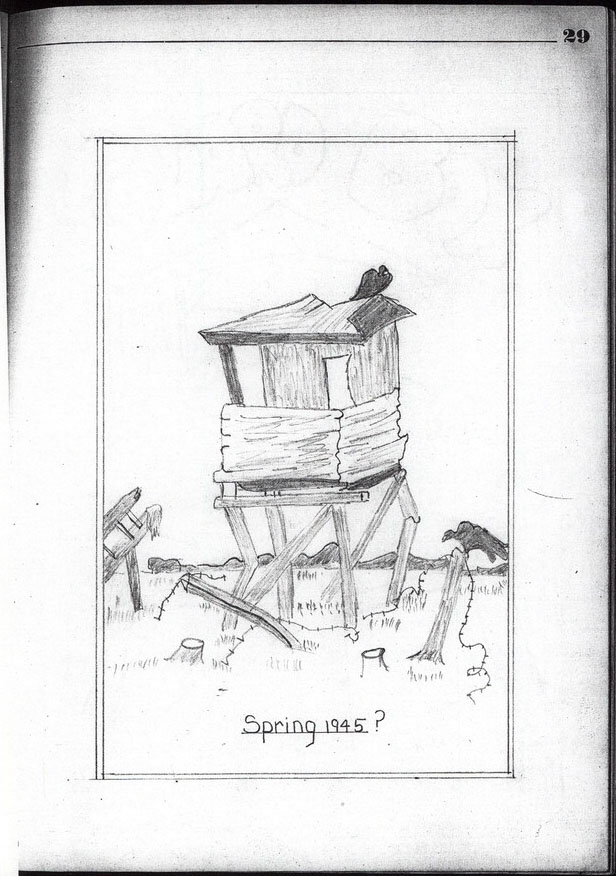

Spring 1940. It is the most beautiful month: May. The first golden daffodils bloom in the green meadows.

The swallows fly low and play among the soldiers, storks look around them, perched on the tall chimneys of beautiful Alsatian villages.

Hitler unleashed the great offensive. The powerful German army, equipped with dreadful war material, starts through Belgium against France. The first French villages are bloodied before being conquered.

The three regiments of foreign volunteers, trained at Barcarès, are advanced to positions where they were to be launched in the most threatened sectors;

22nd regiment in the Somme (The battle of Peronne);

23rd regiment in Soissons region;

21st in the Ardennes.

German planes do not leave the sky. They bombard roads, bridges and railway stations.

The 21st Regiment moves with great difficulty, travel by train, truck and much walking on foot. Every day it makes tens of kilometers.

It is not easy to walk, loaded with picks, shovels, gas mask [?], and back bending under the kit, all connected by cords (the other regiments called us the “Cord Regiment”; there are heavy 1914 guns also…)

Getting ready for a war of the trenches and you have to dig hundreds of miles…

One approaches the Ardennes. The route passes through Longchamps, Chaumont, Erize-la-Grande; after St. Ménéhould, Cernay, le Morthome, to near the village of Boult-aux-Bois. There, we stop in the little wood near the village, and are facing the enemy.

The village of Boult-aux-Bois is occupied by the Germans, ours looks all the white as houses with red tiled roofs, surrounded by glittering fields of all colors.

It is here, in the woods little that the company of Srolek, the “C.A.1” will deliver its first battle. Ours, although exhausted by a long march, quickly occupy fighting positions. The Germans begin by bombing the woods with their artillery; bombs explode in all directions, sift the earth, and cast up the trunks of trees. Then they attack, covered by heavy machine gun fire. We have our first dead.

Here is a comrade with whom you lived, you loved as your brother, who lies bleeding in your arms, and says his last words to you…you; you have to leave and abandon forever…

It was a brief but bloody battle; we were forced to withdraw. The next day, the battalion occupied new positions in the village of Petites-Armoises, dug foxholes, and installed the 25mm cannon and mortars; we became strong.

The Germans attacked every day and often at night, but we came to hold positions and lasted 12 days and 12 nights.

It was only June 10th that the enemy managed to break our lines on both sides.

We are then threatened with encirclement. Also, the order is given to withdraw to Vaux-lès-Mourons, Longueval, Vienne-la-Ville, up to Sainte-Ménéhould.

General Delaissey is personally visiting the battalion, which must cover the retreat of the main army. Sainte-Ménéhould must be taken at any price.

The battalion is strengthened around the village. It blows up the bridges of the Aisne flowing nearby, and digs trenches near the railway lines, on the village squares.

The Germans attack the next day with a heavy, powerful armament and undertake a fierce, uneven battle. They manage to cross the river and with their armored cars darken the village, destroying the only 25mm canon and two mortars that the battalion had.

June 13. The battalion has lost nearly half of its manpower. In the afternoon, Captain Lagarigue gives the order to withdraw. The group of gunners where Srolek Magalnik is situated are to stay behind to cover the retreat.

The Germans had already occupied the entire village of Sainte-Ménéhould but near the cemetery, an old French machine gun “Hotchkiss” still fires.

At 1600 hours, a German bullet pierced the heart of Srolek and put an end to his young life. He fell at St. Ménéhould, defending the French soil of which he dreamed and to which he has devoted his true love.

The next day, refugees; peasants, bury him in the same place where he gave his last breath.

They could not read his name on his military papers riddled with bullets…

The same day unfolds the battle of the Grange-aux-Bois, which fell from us.

The regiment withdrew fighting to Passavant, and then Robencourt-aux-Ponts and Chaumont are in flames.

On June 19, what remains of the 21st Regiment is still fighting at Colombey-les-Belles, and on June 20, held the bloody battle at Allain.

On June 21, the order comes from the staff to stop fighting, and destroy weapons.

The Germans occupied the entire region, disarmed the regiments; the officers promised to treat them as “prisoners of honor” and to grant them the right to their personal weapons…

On June 22, the day the Marshal Pétain signed the armistice and signed France to the enemy, old General Decharme, head of the 35th Division (which included the 21st R.M.V.E.) gave his last order.

He ordered to bring all surviving troops of the 21st Regiment to the village of Tuillier-les-Groseilles. For 15 hours that day, he reviewed the ranks of unarmed soldiers, with torn clothing and bloodied faces. He walked slowly, often stopped, watching the soldiers right in the eye; he will know what to expect! Then he bade farewell:

“Thank you for your heroism, for your sacrifice, your discipline, in my own name and in the name of France.”

On June 23, the rest of the regiment is brought into captivity in Germany.

The commander of the C.A.1. (Srolek’s Company) was Lieutenant Belissant, a cultured and gentle man who loved his soldiers, who adored him.

He is one of those for whom the French ideals of the great French Revolution are a sacred thing, one of those who have contributed over the world to build the reputation of France as a country of justice and humanity.

Lieutenant Bellissant loved Srolek and when Srolek fell, he wept bitterly.

In the first letter he wrote to his wife from captivity, he said: “I had a dear friend, a Jew who emigrated from Bessarabia, he fell as a hero. I know he left a wife and child in Paris. Find them and try to help them.“

***

Life was hard for Goldale and her child in Paris, occupied by the Germans.

She had found a small room in an old house in the Rue des Gravilliers; had transported her sewing machine and was working illegally to earn enough to feed herself and her daughter.

She lived in constant fear, and every night cried for Srolek who fell “somewhere in France”.

Mrs. Bellissant was a good woman, worthy of her husband. As soon as she received the letter from her husband in captivity, she began looking for Goldale. From one address to another, she climbed the floors, visited the attics until she found the room on Gravilliers Street.

The two women quickly became acquainted and soon became friends. Goldale confided in her as a mother. Mrs. Bellissant found Srolek’s tomb in the cemetery of St. Ménéhould. They went there together and placed a memorial slab.

Mrs. Bellissant also found her old concierge of the Rue de Rennes, Mrs. Grimaud, to hide with her Goldale’s daughter Nelly, and thereby evade German roundups.

***

It happened in early 1944, on a gray winter morning, when daylight was just beginning to emerge. Paris was still asleep when they heard on the stairs of the old house on Gravilliers Street heavy military boots; blows brutally beating at the door and crying, “Open!”

Before Goldale had time to get off the bed, they broke down the door. I would have loved to tell you that it was the Gestapo and other German military formations organizing the hunt for Jews in Paris who came to arrest Goldale. Unfortunately, the reality is quite different. They were French; yes, the French, sold-out souls who collaborated with the Germans, demented fascists…or shallow people.

Goldale, in a nightgown, thin, skinny, and trembling, first tried to reason with them: “Leave me, my husband fell for France, I have a small child!”

When dragged by force on the stairs, Goldale struggled. She screamed for help, she swore, she was crying and eventually began to beg: “I have done no wrong, I am a poor seamstress, leave me alone.” Two big fellows seized her and prevailed.

The neighbors came out; in her nightgown, her face swollen with sleep, mostly old men, women and children; emaciated, exhausted by four years of occupation.

Several of them were wringing their hands and crying, looking upon our Goldale taken away in the police car.

Among the deported from Drancy to Auschwitz, from which she never returned…

____________________

Other aspects of the story…

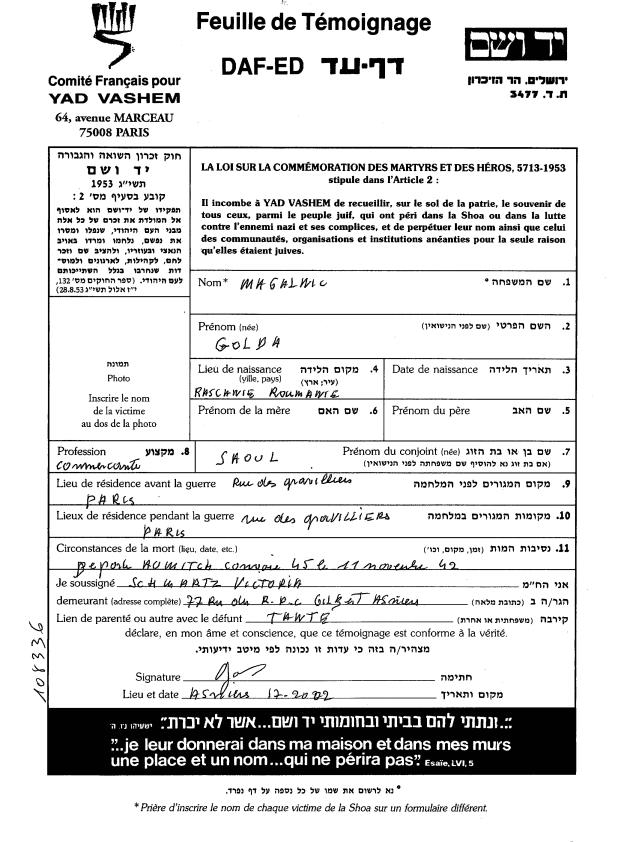

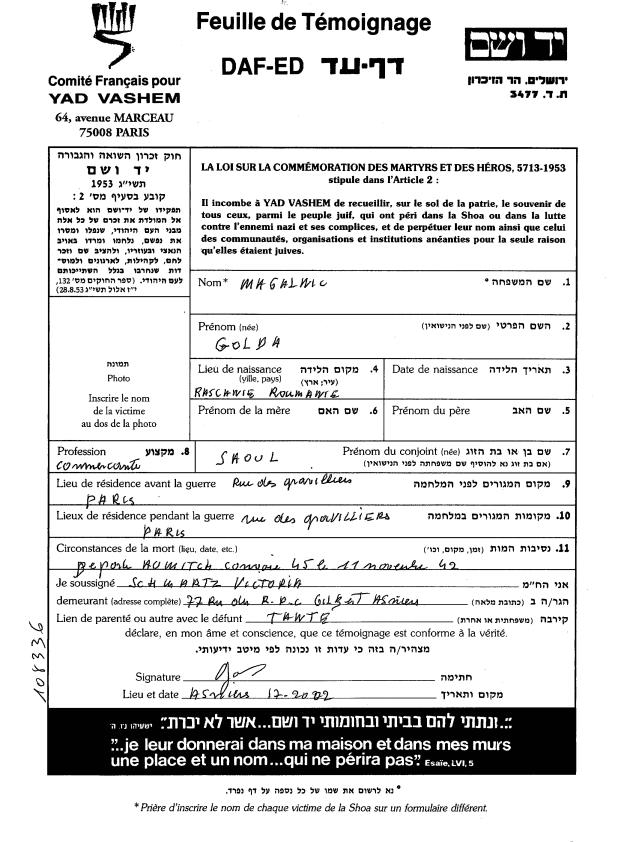

Srul was born in Rezcani, Romania, on August 16, 1912, while Golda (Vozer), also born in 1912, was from Pascani. Srul served in the 21eme Régiment de Marche de Volontaires Etrangers (21st Regiment of Foreign Volunteers).

Srul’s biographical profile at Mémorial Gen Web (Reference Number 1559751) does not specify the date of his death, only listing this as “1940”, and giving his surname as “Magalnick”, while Au Service de la France gives his surname as “Magalnik”.

According to his biographical record in the Secrétariat Général pour l’Administration’s “Base des militaires décédés pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale” database, he died on June 17, 1940, rather than June 13 as given in Ilex’s account. He was killed in action at Saint Menehould, Marne, and is buried at the Bagneux Cemeterty, in Paris.

After Srul’s death, Golda resided in at the Rue des Granvilliers, in Paris’ 3rd Arrondissement. On November 11, 1942, she was deported from Drancy Camp, in France, to the Auschwitz Birkenau Extermination Camp, on Transport 45, Train Da. 901/38. This is a correction to Ilex’s narrative which denotes that she was deported in 1944.

Above all and most important, Beller mentions that Srul and Golda had a “small child” – Nelly; their daughter – who resided with a Mrs. Grimaud, the concierge of Lt. Bellissant’s wife. A search of Yad Vashem’s Central Database of Shoah Victim’s Names reveals – fortunately – no record for “Nelly Magalnic” (at least, using the specific name “Nelly” in the “first name” search field).

Therefore, it seems – one would hope – that Nelly survived the war.

If so, assuming she was born in the mid-1930s, she would now be in her early eighties.

The Central Database of Shoah Victim’s Names reveals something else: A Page of testimony in Golda’s memory, completed in December of 2002, by Victoria Schwartz (her niece?).

____________________

____________________

Some other Jewish military casualties on June 17, 1940, include:

Killed / Tué

– .ת.נ.צ.ב.ה. –

Bach, Andre, Chef d’Escadron, Legion d’Honneur

Armée de Terre, 121eme Regiment d’Infanterie, Groupe de 105 Hippomobile

“Son groupe ayant été coupé du corps d’armée le 7 juin, à continué à combattre avec d’autres éléments jusqu’au 17 juin, date à laquelle il à été mortellement frappé.”

(His group was cut off from the Corps on June 7, and continued to fight with other elements until June 17, when he was fatally struck.)

LODS, p. 126

Not in SGA Seconde Guerre mondiale website; Not in Sepultures du Guerre database

Place of Burial Unknown

Baum, Alfred Isaac, Pvt., 6288801, Killed at St. Nazaire

The Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment), 2nd Battalion

Born 1919

WWRT I, p. 60

Prefailles Communal Cemetery, France – Grave 25

Boos, Emile (AC-21P-27054), Blessures de Guerre; Rancourt

Armée de Terre, 70eme Régiment d’infanterie de Forteresse

France, Bas-Rhin, Nessenheim; 3/16/09 / France, Saverne

ASDLF, p. 138

SGA “Seconde guerre mondiale” website lists unit as “70e RI Forteresse” – SGA “Sepultures de Guerre” website lists Unite as “70eme R.I.F.”

Carre militaire “Navenne”, Navenne, Haute-Saone, France – Tombe Individuelle, No. 59

Bronstein, Georges Youry (AC-21P-34431), Tué à l’ennemi; Yonne, Arthonnay

Armée de Terre, 42eme Régiment d’Infanterie, 5eme Compagnie

Born Russie, Saint Petersburg; 11/23/14

Place of Burial Unknown

Bucholz, Kalmann (AC-21P-35484)

Born Pologne; 1/29/97

ASDLF – 138

Listed in SGA “Seconde guerre mondiale” website, but not SGA “Sepultures de Guerre” website; http://www.memorial-genweb.org/html/fr/resultcommune.php3?id_source=33507&ntable=bp05

(Gives first name as “Kalman”)

Bagneux Cemetery, Bagneux, Paris, France

Fleisher, Soloman, Pvt.,

Royal Army Service Corps, 2nd Field Bakery

Mr. and Mrs. Morris and Ann Fleisher (parents)

Not listed in either WWRT or WWRT II

Dunkirk Memorial, Nord, France – Column 140

Freeman, Leslie, Pvt., 6466563, Passenger aboard S.S. Lancastria, which received direct hit by enemy bomb at Dunkirk.

The Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment), 2nd Battalion

Born 1918

WWRT – I, p. 88

Dunkirk Memorial, Nord, France – Column 38

Goldinberg (Goldenberg), Albert, Soldat (AC-21P-195701), Tué au combat; Cote d’Or, Billy les Chanceaux

Armée de Terre, 232eme Régiment d’Artillerie Divisionnaire

Born France, Paris; 10/25/17

Information from SGA “Sepultures de Guerre” website. Not in SGA “Seconde guerre mondiale” database.

Nécropole nationale “La Doua”, Villeurbanne, Rhone, France – Tombe individuelle, Carre E, Rang 14, No. 2

Harris, Stanley Louis, Sgt., 751759, Passenger aboard S.S. Lancastria, which received direct hit by enemy bomb at Dunkirk

Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, Number 98 Squadron

Born 1920

Mr. and Mrs. Louis and Minnie A. Harris (parents), Freemantle, Southampton, England

WWRT II, p. 27

http://www.rafweb.org/SqnMark098.htm

http://www.lancastria.org.uk/Victim_List/victim_list.html

Runnymede Memorial, Surrey, England – Panel 15

Jungwitz, Mendel Juda, (AC-21P-58140), Tué au combat; Meuse, Sagny sur Meuse

Armée de Terre, 73eme Groupe de Reconnaissance de Division d’Infanterie

Born Pologne, Monwy Dwor; 12/22/03

First name from SGA “Seconde guerre mondiale” website – SGA “Sepultures de Guerre” website gives first name as “Mendel”; other information is identical in both databases.

Nécropole nationale “Faubourg Pave”, Verdun, Meuse, France – Tombe individuelle, Carre 39/45, No. 160

Khan, Peter, Cpl., 13000584

Pioneer Corps, 53rd Company, Auxiliary Military

Born 1905

WWRT II, p. 16

Escoublac-la-Baule War Cemetery, Loire-Atlantique, France – 1,E,33

Levy, Clement Nahman, (AC-21P-76681), “En mission”

Born Israel, Safad; 8/2/15

Place of Burial Unknown

Levy, Francois (AC-21P-76688), Meurthe-et-Moselle, Juvelize

Armée de Terre, 291eme Regiment d’Infanterie

France, Doubs, Besancon; 1/31/18

Place of Burial Unknown

Levy, Roger (AC-21P-78641), Bombardement; Ille-et-Vilaine, Rennes

Armée de Terre, 212eme Regiment d’Artillerie

France, Bas-Rhin, Benfeld; 8/11/06

Place of Burial Unknown

Lewis, Albert, Pvt., 4188602

Cheshire Regiment

Born 1902

Mr. and Mrs. Mark and Sarah Lewis (parents)

WWRT II, p. 18

Pornic War Cemetery, Loire-Atlantique, France – 1,C,6

Saks, Tobiasz (AC-21P-151240), Tué au combat; Marne, Saint Menehould

Armée de Terre, 21eme Régiment de Marche Etranger

Born Pologne, Fedrzejow; 9/29/07

ASDLF, p. 143

Listed in SGA “Seconde guerre mondiale” website – not listed in SGA “Sepultures de Guerre” website; http://www.memorial-genweb.org/html/fr/resultcommune.php3?id_source=33507&ntable=bp05 (Gives first name as “Tobjasz”)

Bagneux Cemetery, Bagneux, Paris, France

Weil, Francois Charles David, Lieutenant (AC-21P-169180), Legion d’Honneur; Vienne, Poitiers / Villampuy

Armée de Terre, Cavalerie / A.B.C. / 2eme // 3eme Bataillon de Chars de Combat

“Grièvement blessé le 17/06/1940 à Villampuy (28) par un coup direct sur son char.”

(Seriously wounded on 17/06/1940 in Villampuy (28) by a direct hit on his tank.)

“Lors de l’attaque de Crécy, le 19 mai 1940 à conduit sa section à l’objectif définitif et à contenu l’ennemi pendant sept heures malgré de violente bombardements d’aviation. Après avoir brillamment participé aux contre-attaques du bataillon du 24 au 31 mai en direction d’Abbevville, à été grièvement blessé le 17 juin au carrefour de Villampuy en assurant la liaison entre ses sections. Est mort des suites de ses blessures.”

(During the attack on Crécy, May 19, 1940 led his section to the final objective and contained the enemy for seven hours despite violent bombing by aircraft. After brilliantly participating in the battalion’s counter-attacks from May 24th to 31st in the direction of Abbeville, he was seriously wounded on June 17th at the crossroads of Villampuy by linking his sections. Died from his wounds.)

Born France, Paris; 10/2/13

LODS, p. 125

SGA gives date as 7/5/40; http://www.memorialgenweb.org/memorial3/html/fr/complementter.php?table=bp&id=112905

Place of Burial Unknown

Winer, Jack George, Pvt., 7659901, Killed in Dunkirk Evacuation

Royal Army Pay Corps

Born 1905

Mr. and Mrs. Joseph and Rose Winer (parents)

WWRT I, p. 174

Dunkirk Memorial, Nord, France – Column 148

Zadoc Khan, Roger Bertrand, (AC-21P-172107), “Non mort pour France”, Creuse, Mas d’Arviges

Born France, Paris; 11/20/01

Place of Burial Unknown

Zapp, Victor Irving, Sgt., 147889, Passenger aboard S.S. Lancastria, which received direct hit by enemy bomb at Dunkirk.

Royal Army Service Corps

WWRT II, p. 23

Pornic War Cemetery, Loire-Atlantique, France – 2,C,15

Zerbib, Raymond Fredj Rahsmin, Soldat (Zouave), (AC-21P-167211), Legion d’Honneur; Seine-et-Oise, Saint Cheron (environs)

Armée de Terre, 3eme Regiment de Zouaves

“Mortellement blessé le 17 juin 1940 en résistant courageusement aux attaques ennemies aux environs de Saint-Cheron.”

(Fatally wounded on 17 June 1940 by courageously resisting enemy attacks near Saint-Cheron.)

Born Algerie, Ain-Beida; 9/4/14

LODS, p. 128

First name and Date de deces from SGA “Seconde guerre mondiale” website – SGA “Sepultures de Guerre” website gives first name as “Raymond”, and lists Date de deces as “6/15/40”.

Nécropole nationale “Fleury-les-Aubrais”, Fleury-les-Aubrais, Loiret, France – Tombe individuelle, Carre 43, Rang 4, No. 58

Prisoners of War / Prisonniers de Guerre

Journo, Raoul, Zouave de 1ere Classe, Citation à l’ordre du Régiment

Armée de Terre, 10ème Corps d’Armée, 84ème D.I.N.A.

Prisoner of War (Prisonnier de guerre); Liberated 4/29/45

LODS, p. 99

Khelifi, Simon, Soldat de 1ere Classe

Armée de Terre, 57eme Régiment d’Infanterie Coloniale (Mixte Sénégalais)

Prisoner of War (Prisonnier de guerre); Frontstalag 230 (France, Vienne, Poitiers)

“Evadé le 22 août 1944 (zone de combat Calvados). Rejoint le bataillon 31éme de Pionnier.”

(Escaped on 22 August 1944 (Calvados combat zone). Joined the 31st Pioneer Battalion.)

Born Tunisie, Tunis; 5/17/15

LODS, p. 111

Liste officielle No. 46 De Prisonniers Francais (11/30/40), p. 33, Liste officielle No. 63 De Prisonniers Francais (1/13/41), p. 33

Wounded (Survived) / Blessé (Survécu)

Sahagian, Abraham, Soldat, Medaille Militaire

Armée de Terre, 107eme Regiment d’Infanterie

“A été grièvement blessé par balle le 17 juin 1940 à son poste de combat aux environs de Laon.”

(He was seriously wounded by a bullet on 17 June 1940 at his combat post near Laon.)

LODS, p. 145

____________________

References

Books

“WWRT I”

Morris, Henry, Edited by Gerald Smith, We Will Remember Them – A Record of the Jews Who Died in the Armed Forces of the Crown 1939 – 1945, Brassey’s, United Kingdom, London, 1989

“WWRT II”

Morris, Henry, Edited by Hilary Halter, We Will Remember Them – A Record of the Jews Who Died in the Armed Forces of the Crown 1939 – 1945 – An Addendum, AJEX, United Kingdom, London, 1994

“LODS”

Chiche, F., Livre d’Or et de Sang – Les Juifs au Combat: Citations 1939-1945 de Bir-Hakeim au Rhin et Danube, Edition Brith Israel, Tunis, Tunisie, 1946

“ASDLF”

Au Service de la France (Edité à l’occasion du 10ème anniversaire de l’Union des Engagés Volontaires et Anciens Combattants Juifs 1939-1945), l’Union Des Engagés Volontaires Et Anciens Combattants Juifs, Paris (?), France, 1955

Web

Ilex Beller (wikipedia entry), at https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ilex_Beller

Ilex Beller (JewishGen KehilaLinks), at https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ilex_Beller

U.E.V.A.C.J. (Union des Engagés Volontaires et Anciens Combattants Juifs 1939-1945 (Union of Military Volunteers and Jewish Veterans of 1939-1945) (home page), at http://www.combattantvolontairejuif.org/160.html

Rue de Gravilliers (wikipedia entry), at https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rue_des_Gravilliers

Golda Magalnic (under surname of “Magalnik”) – biographical information at genweb.org

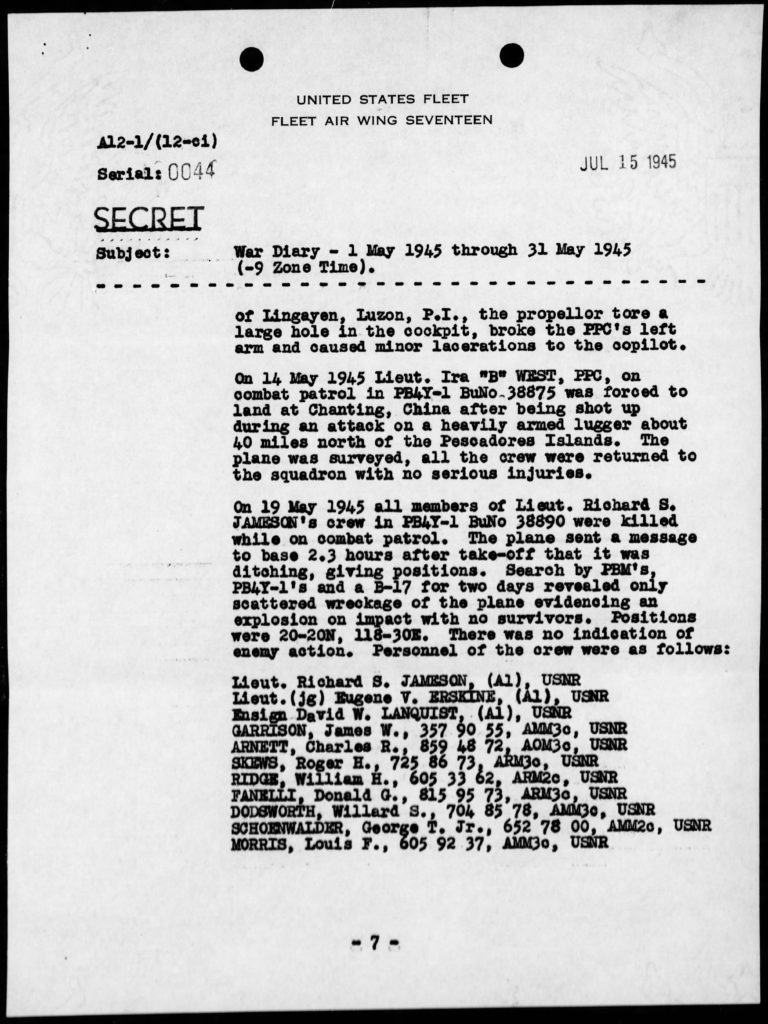

The image below shows Eugene Erskine as a student at Johns Hopkins University.

The image below shows Eugene Erskine as a student at Johns Hopkins University. Lieut. (j.g.) Eugene V. Erskine of the Navy, a pilot with Bombing Squadron 104, was killed in action in the Pacific theatre on May 19, the Navy Department has informed his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Max Erskine, of 2173 East Twenty-Third Street, Brooklyn. He was 24 years old and a native of New York.

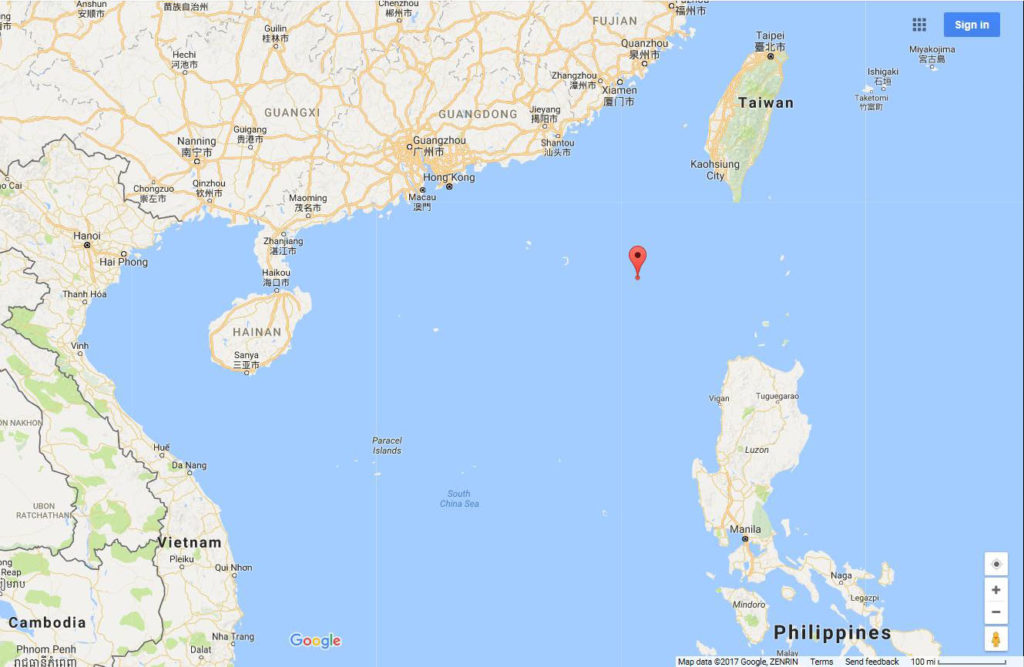

Lieut. (j.g.) Eugene V. Erskine of the Navy, a pilot with Bombing Squadron 104, was killed in action in the Pacific theatre on May 19, the Navy Department has informed his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Max Erskine, of 2173 East Twenty-Third Street, Brooklyn. He was 24 years old and a native of New York. Some other Jewish military casualties on Saturday, May 19, 1945, include…

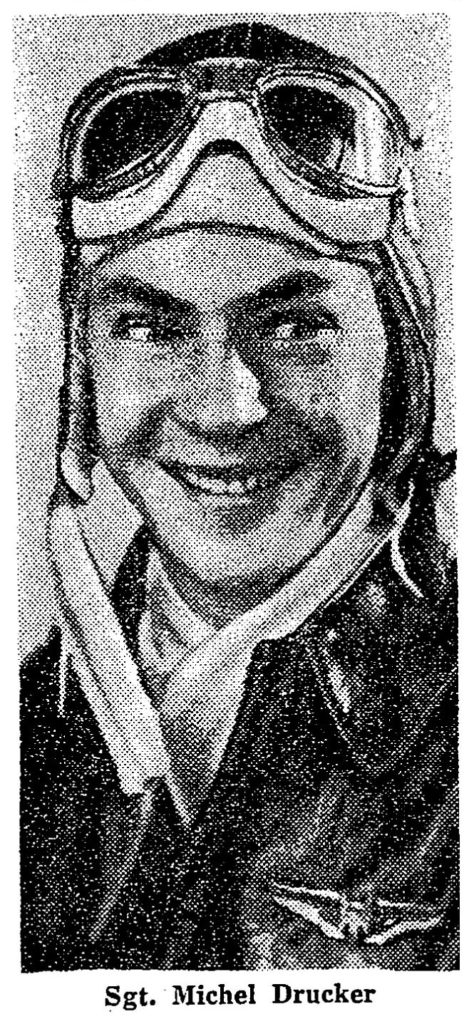

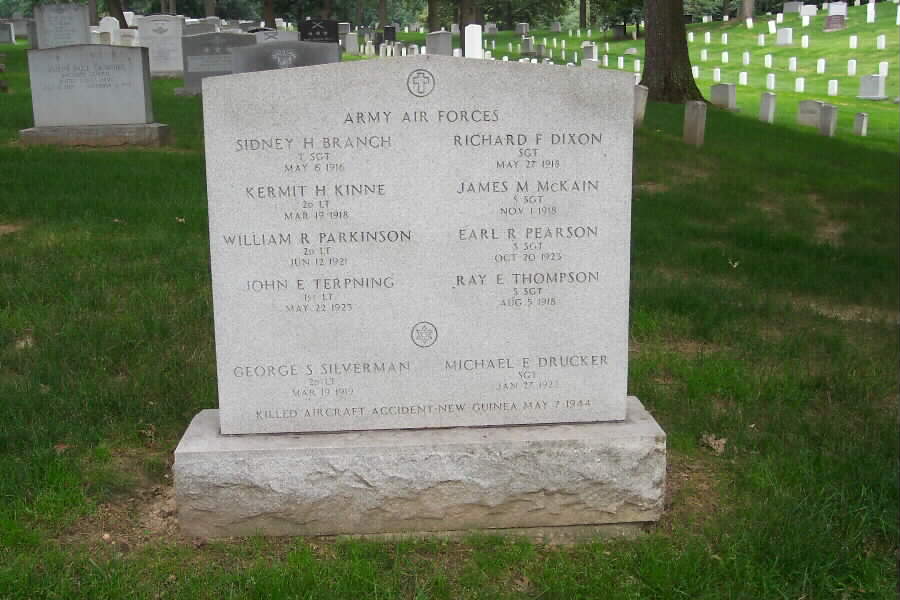

Some other Jewish military casualties on Saturday, May 19, 1945, include… The image below, at the website of the Center for Research: Allied POWs Under the Japanese (created by the late Roger Mansell) shows Milton and his fellow crewmen in happier times.

The image below, at the website of the Center for Research: Allied POWs Under the Japanese (created by the late Roger Mansell) shows Milton and his fellow crewmen in happier times.  Lt. Lewis and F/O Burrows are also seen in this photo.

Lt. Lewis and F/O Burrows are also seen in this photo. Paralleling Milton’s story, Walter Bailey’s account of his military (and postwar) experiences – transcribed from audiotape – is also available at the Center for Research: Allied POWs Under the Japanese website, under the appropriate title Walter Bailey: B-25 Crewman – Zack crewman. Walter’s story is very detailed, profoundly moving, and quite explicit about the physical and emotional nature of capture by – and captivity under – the Japanese in the Second World war.

Paralleling Milton’s story, Walter Bailey’s account of his military (and postwar) experiences – transcribed from audiotape – is also available at the Center for Research: Allied POWs Under the Japanese website, under the appropriate title Walter Bailey: B-25 Crewman – Zack crewman. Walter’s story is very detailed, profoundly moving, and quite explicit about the physical and emotional nature of capture by – and captivity under – the Japanese in the Second World war.