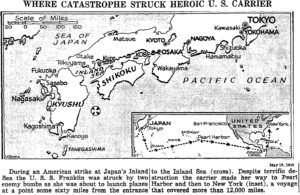

As shown by my other posts, many things occurred on March 19, 1945.

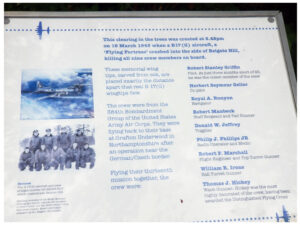

Having reviewed the military service of Jewish soldiers in the ground forces of the Allies – here – “this” post and others to follow now reach nearly eight decades back in time, to venture skyward and recall the experiences of three Jewish airmen in the United States Army Air Force. The strange commonality of their fates was service in the same military unit: The ‘Flyin’ Cowboys’ – the 673rd Bomb Squadron of the “Sky Lancers”, of the 417th Bomb Group of the 5th Air Force. One of the trio survived. Two, did not.

The story actually begins on October 13, 1944, becomes centered upon March 19, 1945, and abruptly concludes four days later: on March 23. Oddly, though assuredly not of concern at the time, in the hindsight of nearly eight decades, their fates were seemingly connected by one particular aircraft.

______________________________

But first… Here’s the comet-in-a-5 (note the five background stars?) insignia of the 5th Air Force. (This is my own patch.)

From The Sky Lancer, here’s the insignia of the 417th Bomb Group…

…and from the same book, the Flyin’ Cowboys emblem of the 673rd Bomb Squadron.

______________________________

The 417th was equipped with Douglas A-20 Havoc light bombers, as shown in this depiction from Roger Freeman’s 1974 book about WW II USAAF camouflage and markings. The group identified its planes via an angled / white-trimmed fin/rudder flash in red, yellow, white, or blue, for the 672nd, 673rd, 674th, and 675th squadrons, respectively. This was accompanied by an individual aircraft letter painted in white on the rudder. Thus, PiZ-DoFF, the plane below, was assigned to the 672nd Bomb Squadron.

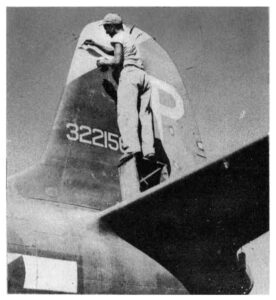

This photo from The Sky Lancer is an excellent view of the tail of 43-22156, “P“, of the 673rd Bomb Squadron…

…while this is 43-22235, “U“, of the 672nd or 675th Bomb Squadrons. There are no MACRs or Accident Reports for either aircraft, which would suggest that they survived the war and were turned over to the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, perhaps to eventually be turned into postwar aluminum siding.

______________________________

On October 13, 1944 … 26 Tishrei 5705

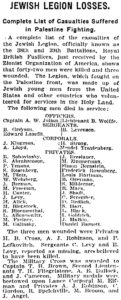

S/Sgt. Jerome Rosoff (12091883) – Killed in Action

– .ת.נ.צ.ב.ה. –

…Tehé Nafshó Tzrurá Bitzrór Haḥayím …

Let’s begin at this story’s beginning, as recorded in the history of the 673rd Bomb Squadron. On October 13, 1944, the squadron participated alongside the 672nd, 674th, and 675th Bomb Squadrons in a strike against Amahai Drome (now Amahai Airport; adjacent to the town of Amahai) on the island of Ceram (now Seram), in Indonesia. Here’s the text of the 673rd’s Mission Report:

12 A-20s and 1 B-25 were scheduled to strike Amahai Drome on 13 October 1944 however one plane had malfunction in bomb release mechanism and failed to take off. 11 planes took off in a coordinated attack with 3 squadrons, all of the 417thBombardment Group (L) participating. Attacking from E.S.E. to W.N.W. bombs were observed hitting across the north 1/3 of runway with 46 bombs bursting in center of Amahai Town and walking across runway to west shore line. Smoke from bomb bursts prevented further observation of results. 5 gun flashes spotted in south central edge of Amahai Town. Medium to heavy and very accurate A/A fire came from a knoll east of the center of strip. A/A holed 4 planes with slight damage to aircraft, however S/Sgt. Jerome Rosoff, A.S.N. 12091883, gunner in plane #155 was fatally injured by anti-aircraft fire. 46 x 500 1b 1/10 second delay tail fusing GP bombs were dropped on target. 2 bombs were jettisoned with none returned.

______________________________

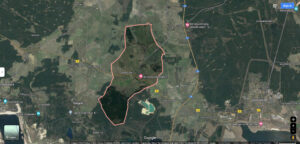

Not 1944, but 2023: Amahai Airport, which I assume occupies the location of the original Amahai Drome.

Zooming out, you can see that the airport is situated south of the present Amahai town. Note the rectangular clump of trees lying beyond the northwestern end of the runway, immediately to the southwest of the town itself. This overgrown area is probably a portion of the original wartime runway which was impacted by the 417th’s bombs on October 13, 1944 (along with Amahai town) and has never been repaired.

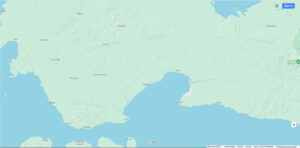

Amahai town – in the lower center of this map – is located at the end of a sort-of-isthmus on the eastern side of Elpaputi (Elpaputih) Bay. (No captions on this map!)

Here’s Seram (Ceram) Island to the east, and Buru Island to the west.

And, the setting of Seram Island within Indonesia.

______________________________

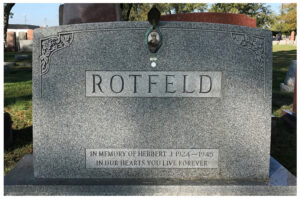

Like so many other American Jewish soldiers described in my prior posts, S/Sgt. Jerome William Rosoff’s name never appeared in the 1947 National Jewish Welfare Board publication American Jews in World War II, though it was published in a War Department Casualty List released on December 9, 1944. Born in Bayonne, New Jersey on January 21, 1922, he was the son of Fannie Rosoff, who resided at 2323 Davidson Ave. (and possibly 2209 Andrews Ave.?) in the Bronx. He was buried at Long Island National Cemetery, in Farmingdale, N.Y. (Section J, Grave 14556) on February 17, 1949.

Given the nature of the air war in the Pacific Theater, this sad event was one of the truly rare occasions when a fallen airmen could actually be accorded a military funeral by his comrades. And so, this picture of S/Sgt. Rosoff’s burial also appears in the historical records of the 673rd. Unfortunately, the names of the airmen appearing in the picture were not recorded. (I’d like thank the AFHRA for this photo: “Thanks, AFHRA!”)

Being that – by definition – neither S/Sgt. Rosoff nor his pilot were actually missing (for 48 hours), no Missing Air Crew Report was ever filed for this incident. (This is verified by the MACR name index card file, which lists “No MACR” for S/Sgt. Rosoff.) Likewise, the 673rd Squadron history doesn’t list the name of the sergeant’s pilot. However, there’s a singular clue concerning the identity of the A-20 they were flying: The serial number ends in the digits “155”. Comparing this number to the “last three” for 417th Bomb Group A-20s listed in Missing Air Crew Reports suggests that this plane was A-20G 43-22155. (About which, much more shortly.) And, the 3rd Attack Group website reveals – definitively – that “155” was indeed 43-22155, otherwise known as “Chadwick 2nd”. Shown in the photo below…

Being that – by definition – neither S/Sgt. Rosoff nor his pilot were actually missing (for 48 hours), no Missing Air Crew Report was ever filed for this incident. (This is verified by the MACR name index card file, which lists “No MACR” for S/Sgt. Rosoff.) Likewise, the 673rd Squadron history doesn’t list the name of the sergeant’s pilot. However, there’s a singular clue concerning the identity of the A-20 they were flying: The serial number ends in the digits “155”. Comparing this number to the “last three” for 417th Bomb Group A-20s listed in Missing Air Crew Reports suggests that this plane was A-20G 43-22155. (About which, much more shortly.) And, the 3rd Attack Group website reveals – definitively – that “155” was indeed 43-22155, otherwise known as “Chadwick 2nd”. Shown in the photo below…

“Caption: “This aircraft is A-20G 43-22155 after assigned to the 673rd Squadron / 417th Bomb Group. This aircraft was most likely transferred from 3rd Bomb Group Headquarters where it flew as the 2nd Chadwick, until the arrival of the A-20Hs. There is no evidence that any other Group in the SWPA used the Wheel marking except the 3rd Bomb Group.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

On March 19, 1945 … 5 Nisan 5705

S/Sgt. Seymour Weinberg (19173661)

Missing in Action and Returned to the Land of the Living

On March 19, 1945 just over five months after the death of S/Sgt. Rosoff aboard Chadwick 2nd, S/Sgt. Seymour Weinberg of Los Angeles occupied the same crew position (…well, there were only two crewmen in the solid-nose A-20G anyway…) as S/Sgt. Rosoff: the aircraft’s dorsal turret, the aircraft piloted by 2 Lt. Ralph Melvin Jennings. While on a bombing strike against targets at the Philippine city of Bacolod, on Negros Island, S/Sgt. Weinberg experienced a fate that – while not at all unheard of among airmen in the Pacific Theater – was in its own way still miraculous: Ditching, survival at sea, being tossed upon a small island, being cared for by natives (one particular native at that), and ultimately, rescue by the Navy. The historical record for these events is detailed and comprehensive, comprising two eyewitness accounts, particularly among them S/Sgt. Weiner’s own testimony.

______________________________

We’ll begin with the report of 2 Lt. Richard M. Fischer, from Missing Air Crew Report 13610; the story of the plane’s loss is summarized at Pacific Wrecks, as well.

On 19 March 1945, I was leading the second element of a six ship formation, returning from the target assigned to us by ground controller. We were heading on course (335o) for home after crossing southern tip of Panay. I was flying the bottom box when Lt. Jennings’ right engine puffed black smoke. He gave me a call on B channel, VHF, and said, “I’m having trouble with my right engine but believe I’m going to be all right. Bear with me.” So I replied, “OK, I’ll pull up on your left wing.” He was losing air speed at the time. I reduced speed and criss-crossed above and to the left of him. After seeing him fire his nose guns and turret guns, I knew something serious was wrong. His right engine was feathered. I tried to contact him, but he must have been on D channel or inter-phone. Just a minute or so after that I saw him ditch. There was a small splash, then a great large one. The sea was very rough and he landed approximately into the wind. I was unable to contact the rescue officer, who was my left wingman, so I directed my right wingman, Flt Officer Harmell, circle the area until he ran low on gas and had to return. My left wingman and I made one circle of the wreck at reduced air speed, trying to pick up the formation before returning to base. I saw on survivor, but was unable to identify him. He was wearing his mae west. I returned to the field trying to contact all Playmates and Martinis in the area but no one answered my call. At 1220 I contacted Hammer Tower and told them that the wreck occurred at 1200 on an approximate heading of 160o from San Jose, Midoro Island. I gave them the Squadron number of the plane and told them to notify 673rd Bombardment Squadron. I landed at 1245 and gave mission report to Squadron Intelligence Officer, verifying the location of forced landing as pointed out on the overlay map attached.

Here’s how Lt. Fischer’s statement looks in the MACR:

______________________________

The pilot mentioned in Lt. Fischer’s account as “Flt Officer Harmell” was F/O Samuel Harmell, whose own account in the MACR follows:

On 19 March 1945, I was flying No. 5 in a 6 ship formation led by 1st Lt. Ralph M. Jennings. Returning from the target, Lt. Jennings called on the radio and said that he was having engine trouble, but everything was under control. The element I was flying in then pulled out to his left and cut our air speed. Lt. Jennings emptied nose and turret guns, while we were out to the left, and started a descent. I pealed away from formation when he started to go down. I passed over the top of the spot he hit, approximately 20 or 30 seconds after he hit. I turned very sharp and came right back over and all I saw was an oil slick. I circled the area for about 50 minutes, then had to leave because of fuel. I saw absolutely no one emerge from the plane. Location where plane went down is approximately 18 miles south of Sibay Island and 14 miles west of Maniguin Island, time was approximately 1200 hours.

This is how F/O Harmell’s statement appears in the MACR:

More about F/O Harmell will follow below.

______________________________

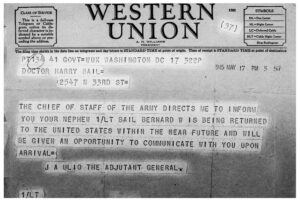

Two days later, on March 21, the Group Rescue Officer of the 417th, Capt. Jack W. Lingo, reported on the extent of the search for Chadwick 2nd’s missing crew, specifically noting the discrepancies in Lt. Fischer’s and F/O Harmell’s statements: “Conflicting reports were received from the aircraft which witnessed the ditching as one pilot reported seeing a raft open and at least one crew member in the raft, while the other piloted reported not having seen any survivors.”

After summarizing the extent of the search for the missing crew by OA-10 Catalinas and 417th BG A-20s on the 20th and 21st, Captain Lingo closed with this statement: “At the time Lt. Jennings ditched there was an extremely heavy sea running with winds in excess of twenty-two knots. The sea current and prevailing winds would have carried any survivors south west toward Palawan Island and adjacent smaller islands. Air Sea Rescue section of Fifth Air Force has contacted Guerilla units in the Palawan Island area to watch for any survivors and advise if sightings are made. The daily search by the Group will be continued at least for one week.”

Captain Lingo’s summary:

______________________________

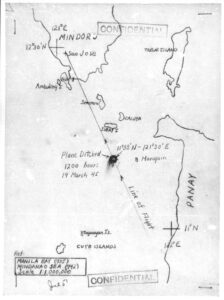

From the Missing Air Crew Report, here’s the map of the approximate location of Chadwick 2nd’s ditching:

______________________________

But, there’s far, far more.

Captain Lingo was entirely correct in suggesting that, “The sea current and prevailing winds would have carried any survivors south west toward Palawan Island and adjacent smaller islands.”

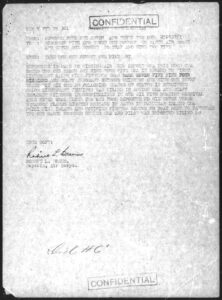

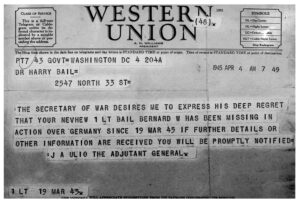

The final page of the Missing Air Crew Report includes via a teletype message which succinctly reveals what befell Lt. Jennings and S/Sgt. Weinberg, and explains the “Chg to Condl / KIA” (Change to Condolence / Killed in Action) and “No Info / SIA” (No Information / seriously injured in action) on MACR 13610: Lt. Jennings was killed in the ditching, and S/Sgt. Weinberg survived after being washed ashore on Patungas Island. The full text of the teletype, I think dated 0837 hours on March 25, follows:

PRIORITY CONFIDENTIAL

FROM: COBOMGR FOUR ONE SEVEN APO THREE TWO ONE 250837/I

TO: COBOMCOM FIVE APO SEVEN ONE NOUGHT CG FIFTH AIR FORCE APO SEVEN ONE NOUGHT CG FEAF APO NINE TWO FIVE

CITE: TARE HOW ONE NOUGHT ONE MIKE BT

REFERENCE IS MADE TO MISSING AIR CREW REPORT CMA THIS HDQS CMA DATED TWO ONE MARCH ONE NINE FOUR FIVE CMA IN REGARD TO FIRST LIEUTEANT RALPH MIKE JENNINGS ZERO DASH SEVEN FIVEN NINE FOUR SIX ZERO AND STAFF SERGEANT SEYMOUR WEINBERG ONE NINE ONE SEVEN THREE SIX SIX ONE PD FOLLOWING CHANGE OF STATUS IS SUBMITTED COLON LIEUTENANT JENNINGS WAS KILLED IN ACTION CMA AND STAFF SERGEANT WEINBERG IS HOSPITALIZED IN ONE SIX FIVE STATION HOSPITAL ABLE PETER OBE THREE TWO ONE FROM EXPOSURE PD SIX SEVEN THREE SQUADRON PLANES SIGHTED MESSAGE IN SANDS IN PATUNGAS ISLAND CMA PHILIPPINE ISLAND AND NOTIFIED FIGHTER SECTOR PD BOAT SENT TO PATUNGAS TWO ONE MARCH RESCUED GUNNER CMA AND PILOT WAS REPORTED KILLED PD

TRUE COPY:

Robert L. Breum

ROBERT L. BREUM

Captain, Air Corps.

Here’s how the teletype looks in the MACR:

______________________________

While the MACR contains no further information about the incident, the presence of the above summary strongly suggested – when I first read it – that the story in its full detail might be found “somehere”: Perhaps in the historical records of the 673rd. This is so; it indeed is. Rather than abstract, summarize, recapitulate, regurgitate, and otherwise “tell” the story in my own words, it’s far better to leave it to S/Sgt. Weinberg himself.

Here his report as dictated to Intelligence Officer of the 673rd, interspersed with photos and a diagram. (It reads much better in the original telling than it ever could by abstracting.)

C O N F I D E N T I A L

673RD BOMBARDMENT SQUADRON (L)

417TH BOMBARDMENT GROUP (L)

APO 321

2 April 1945.

SUBJECT: Rescue in the CUYO ISLAND.

TO: Commanding Officer, 417th Bombardment Group, APO 321.

Attention: Air-Sea Rescue Officer.

On return flight from a bombing mission over Bacolod Airdrome, Negros Island (19 March 1945), my pilot, 1st Lieutenant Ralph M. Jennings, told me over interphone that our right engine was losing power but not to worry as he had the plane well under control. Approximately 75 miles from base the right engine cut off completely with left engine losing power and the plane losing altitude. I crawled out from the turret into the hatch to remove the camera and, getting back into the turret, asked the pilot if I could fire the turret guns. He said okay and proceeded to fire his own nose guns. Then I got out of the turret again to throw out links and empty shells. Closed hatch door and used the gun mount to lock it. Then the pilot, just as I got into the turret, told me that we would have to ditch and to get ready. He said: “Hurry up, we haven’t much time.” I took out my automatic and fired fourteen shots into the turret dome, aiming at the seams of turret guns. The dome cracked, but not enough to facilitate a free exit. With my jungle knife, bare fists, head and shoulders I finally succeeded to remove enough of the dome to enable myself to get out. The plane was going down fast, very fast. I stayed in the turret, placing my left hand on gunsight and the head against it. With my right hand behind the neck, I waited for plane to hit the water.

The plane neither jarred nor bounced upon hitting the water. I crawled onto the left wing and saw the plane submerged way back to the radio hatch. The pilot couldn’t be seen, but I did see blood oozing from the vicinity of cockpit, unidentified articles, stained with blood, floating around me. The life raft was spread out in an overturned position and without being inflated. I struggled to inflate it as the sea was very rough. I pulled the sea marker and got into the raft, inflating it from the inside. When the raft hit the water upside down, the first-aid kit, food and water were lost. Only one can of water was saved, but this was positively foul and made me sick when I drank some of it. Other items, such as paddles, one pair of plyers, bailing bucket, about three wooden plugs, one tube of rubber glue, and a fishing tackle, were found on the raft. I had only my signal mirror with me and the clothes I was wearing. The first thing I did on the raft was to look for any injuries I might have suffered during the ditching. There were scratches on my hands and elbows, caused by pushing out the turret dome. To avoid sunburn, as much as possible, I rolled down my sleeves, buttoned and pulled up the collar, with pants well tucked inside the stockings. In addition, I covered my face with a cloth map. My emergency kit was lost while I tried to inflate the raft. My watch stopped an hour after we ditched and I did not have a compass.

____________________

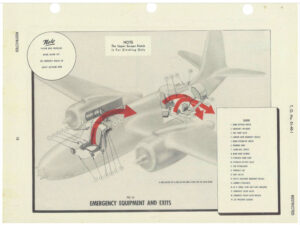

From the A-20GJ and P-70AB Pilots Flight Operating Instructions, this diagram illustrates emergency equipment and exits for G and J series Havocs. Though the diagram indicates that crewmen in the rear of the fuselage should exit from a hatch between the dorsal turret and fin, S/Sgt. Weinberg improvised his escape by not-so-gently removing his turret’s plexiglass by means of his .45, jungle knife, and bare fists. It worked.

From The Sky Lancer, this photo, entitled “The Old Man”, shows an unidentified Captain of the 673rd Bomb Squadron in the cockpit of his A-20. The plane’s life raft rests on a shelf behind the pilot’s seat, while the canopy, hinged on the right (it could be jettisoned in an emergency), is flipped open. By the time S/Sgt. Weinberg reached this part of the plane it had been fully submerged, and Lt. Jennings – unconscious and probably worse – was still in his seat.

Here’s another view of an A-20G or J cockpit, looking aft. Unlike USAAF heavy bombers where multi-place life rafts were stored, very tightly folded, in specifically designed fuselage compartments from which they could be remotely jettisoned and automatically inflated, the crew life raft in A-20s seems (?) to simply have been loosely folded, with the crew needing to manually extract it from the aircraft after ditching. The horizontal tail band and single letter indicate that this plane is an aircraft of the 312th Bomb Group.

____________________

When the Squadron planes returned to base I rested and waited for rescue. Approximately two hours later, one Catalina and two A-20s were flying several miles beyond my position, evidently trying to locate the floating life raft. I tried to attract their attention with the mirror but somehow they didn’t see it.

Early in the evening the sea became rougher. There wasn’t anything I could do. I fell asleep and slept until a big wave woke me and tossed me overboard. I was able to swim back into the raft, but lost my bailing bucket. In order to assure myself against such a repetition I made use of the fishing tackle by tying one end of its string around my waist and the other end to the raft, so as to prevent losing contact with the raft in case I should be thrown out again. Sure enough, the same thing happened when the raft was overturned for the second time. Just being tied to it made it easier for me to get in. I went back to sleep and, just before early dawn, found myself offshore of a big island, but couldn’t reach it due to a strong current and swelling sea which forced me in the opposite direction.

After sunrise the sea continued rough, but visibility was perfect. There were about seven islands in sight. Meanwhile, I saw planes looking for me throughout the day. The same day, later in the afternoon, I found myself drifting towards one of the islands. This island, I could see, was cultivated and had a few houses on it. On nearing the shore I got out of the raft and clung to the side of it, riding the waves to land on the small beach.

I looked up and saw a young Filipino boy. He looked very frightened as he thought I might be a Jap. I must have been badly weather beaten to convey such an appearance. He told me I had landed on Patunga Island and that there were no Japs on the island. He also said in answer to my question — that there were no guerillas on the island. Then he wanted to know if I carried a gun. When I told him I didn’t he became very calm and took notice of my air corps shoulder patch.

Then he gave out a long whistle to attract the attention of the villagers. The entire population must have come to the scene immediately after his signal, as between 20-30 families came to see me. Amidst their lively talk I collapsed from sheer exhaustion and was picked up and carried to someone’s home. One man, slightly older than the rest spoke English and served as interpreter. I asked for some water, which was brought to me by a very lovely, young girl. The water, however, was boiled and too hot for drinking. The girl brought me several raw eggs but after taking one of them I asked for other eggs to be boiled. Strangely enough, I was neither too thirsty nor hungry. The girl, who watched over me like an angel, spoke only few words of English, but was able to nurse me like a true professional, dignified all the time, and extremely solicitous for my welfare. More food was brought to me, chicken and rice, which I wasn’t able to eat. Food was served on a porcelain plate and silverware was used. The house looked clean and had most of the bare essentials of furnishings. When I asked for a bath, two big bowls of water were brought to me from a nearby well. By that time my hands felt numb from too much paddling, and my right forefinger began to burn and swell. I tried to manage, without the assistance of anyone, to remove my clothing but found I was unable to do so. The girl noticed this and proceeded to chase everyone out of the house after which she undressed and bathed me in a most efficient manner.

After the bath I was completely relaxed, but as soon as I lay down I vomited the small amount of food I had eaten. Shortly after, I felt a little better and was able to eat one egg, however I still felt very weak. Soon after this I began to shake with the chills so another mat was added to my bed and some square knitted towels were spread over me and I slept until sun down. When I woke up the girl brought me some chicken with boiled rice and baked bananas, but again my appetite failed me and I was unable to appreciate this delectable dish. At sunrise the following day I was awakened by pain in one finger which had swollen during the night. I kept soaking my finger in hot water several times during the day to reduce the swelling. Later in the morning they assisted me down to the beach where I found my raft. This activity tired me somewhat so we returned to the village and this time I had no difficulty falling asleep.

About two o’clock in the afternoon the girl awakened me and said there were planes in the distance. Identifying them as A-20s I had the Filipinos carry the raft to the beach. Standing by the raft I again used my signal mirror only this time it worked. The two planes were from my squadron and on their second pass the pilots recognized me but to make certain I printed my name in huge letters in the sand.

Medical supplies were dropped with a message asking me if Lt. Jennings was with me. I wrote the word NO in the sand and upon seeing this the two planes headed homeward. I went back to the house and used the medical kit as best I could.

About an hour later the Filipinos ran into the house and told me that two “Q” boats were approaching the beach. I couldn’t understand what they mean to I hid myself in the bushes until I could identify the boats as friendly. Much to my relief they proved to be PT boats that were on their way to take me off the island. I again used my signal mirror and in no time at all we were on our way to the PT base at CUYO ISLAND.

There I was taken ashore and provided with excellent medical treatment by a detachment of the 165th Station Hospital. The next day the medical unit was to leave for Mindoro but the PT boats ran onto a reef and we were unable to depart. They radioed for a Catalina as the doctors decided that a PT ride would be too rough for me. The Cat arrived but couldn’t land because of the rough condition of the sea. They called and said they would return the next day which they failed to do. So we returned to Mindoro in a PT after all. Four days spent at the 165th Station Hospital had quickly brought back my strength and put me once again on the road to a speedy and complete recovery.

Above is a Narrative account as told by Staff Sergeant Seymour Weinberg to the 673rd Squadron Intelligence Office.

JAMES A. ADAMS,

Captain, Air Corps,

Intelligence Officer.

______________________________

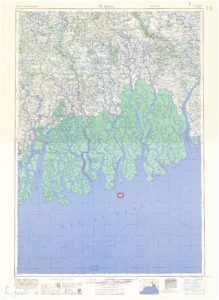

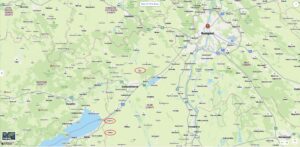

This series of maps, at successively larger scales, recapitulate the loss of Chadwick 2nd and S/Sgt. Weinberg’s rescue.

First, a general map of the Philippine Islands, with the approximate position of Chadwick 2nd’s loss denoted by the small red oval in the center of the map. Bacolod city, also in the center of the map, lies to the southeast.

Here’s a closer view, again with the site of the aircraft’s loss denoted by the red oval in the center of the map, about 117 miles northwest of Bacolod.

The location can be seen to have been in the Sulu Sea. The nearest land, Pucio Point, is 24 miles to the northeast.

This map gives an excellent impression of what really confronted the two airmen: The plane came down in the open sea, with a scattering of islands to the southwest but nothing between.

The raft came to rest on Patungas (Patungas?) Island – here circled in blue – which even at this larger scale is too small to bear a name. Note that the only lands beyond Patungas Island are Lubic and Pamitinan Islands (both currently inhabited) to the southwest. After that absolutely nothing, until Calandagan and Maducang Islands, and finally, several tens of miles further southwest, Palawan.

Here’s Patungas Island as it looks today. It measures roughly 1 mile east-west by a little over 1/2 mile north-south. Note that the only area of habitation (in 2024, and probably in 1945) lies alongside the northern shore, which has an obvious sandy beach and is probably where S/Sgt. Weinberg’s raft grounded. If this is so, he was not only extraordinarily fortunate in simply reaching the little island, he was astonishingly lucky twice over in landing upon the only (?) accessible beach: The island’s three other shores appear to have steep cliffs, and are devoid of any nearby human habitation.

______________________________

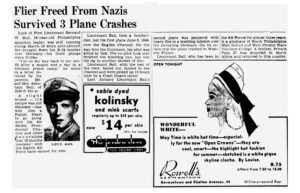

S/Sgt. Weinberg (ASN 19173661) survived the war, but I’ve no information about his life subsequent to 1945. Born in Los Angeles on either August 18 or September 17, 1924, he was the son of Charles B. and Pauline (Fox) Weinberg and brother of Burton and Norman, the family residing at 657 North State Street. His name appeared in a War Department Casualty List released to the news media on May 15, 1945, and can be found on page 56 of American Jews in World War II.

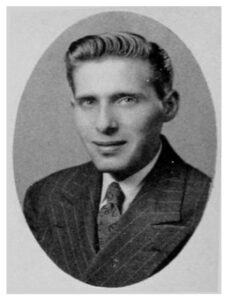

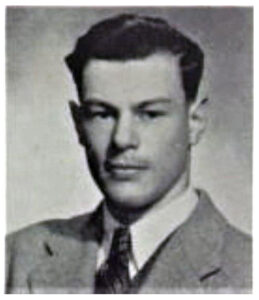

I think (?) he appears in the following two photos, which I found via Ancestry.com. From the 1942 Yearbook of Theodore Roosevelt High School in Los Angeles, he (well, “a”) Seymour Weinberg appears in the photo of members of the school’s Latin Club, at far left in the front row. (Quite remarkable that the high school actually had a Jewish club to begin with. Would they permit one in 2024?…)

Here’s a close-up of the photo. To the right of Seymour Weinberg are Ben Goland and Henrietta Frank.

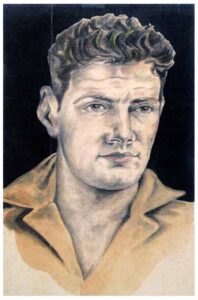

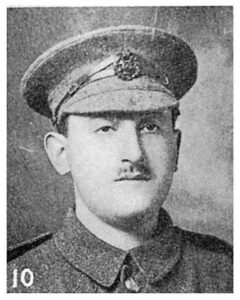

S/Sgt. Weinberg’s pilot, Lt. Ralph Melton Jennings, is the subject of two FindAGrave biographical profiles (here and here). The image below is via Jaap Vermeer…

…while this picture is via Jack Pool:

Like many WW II Casualties whose bodies have never been – could never have been – recovered, Lt. Jennings has a symbolic grave maker. This is at the Norton Cemetery in Norton, Texas. He had a sister, Clarice Dorcas, who died as a young child. I don’t believe his parents had any other children.

The two FindAGrave profiles for Lt. Jennings include transcripts of articles from the Abilene Reporter concerning news of his Missing in Action and Killed in Action status, with the latter – published on May 3, 1945 – indicating that the Lieutenant’s family received a letter from S/Sgt. Weinberg (whose name is obviously not given in the article) having related what transpired on the mens’ last mission.

The latter article states, “The letter stated that Lieutenant Jennings went down with his ship when it crashed in the ocean with one motor gone and the second one shot out. The gunner said he tried to extricate Jennings, but could not and that the officer was knocked unconscious when the plane hit the water. Other crew members were able to get out in rubber rafts.” Though entirely true, it’s clearly obvious – in light of what S/Sgt. Weinberg actually witnessed after he was able to free himself from the sinking wreck of Chadwick 2nd and reach the area of the bomber’s by-then-completely-submerged cockpit – that the Sergeant refrained from communicating information about his pilot’s death that would’ve been unnecessarily distressing to Jennings’ parents.

Here are the two articles:

BALLINGER FLIER MISSING IN ACTION

FRIDAY MORNING, APRIL 20, 1945

BALLINGER, April 29–Lt. Ralph Jennings, son of Mr. and Mrs. Clarence Jennings of Ballinger, has been missing in action since March 19, his parents have been informed.

Pilot of a Mitchell B-25 bomber, Lieutenant Jennings has been in the Southwest Pacific since July and has completed over 50 missions. He recently received his promotion to first lieutenant.

His wife, the former Juanita Hilliard of San Angelo, has been making her home in Houston while the lieutenant was overseas. He was a former player on the San Angelo junior college football team.

MISSING FLIER REPORTED KILLED

THURSDAY EVENING, MAY 3, 1945

BALLINGER, May 3–Mrs. Ralph Jennings has received a letter written by a gunner on the plane piloted by her husband, 1st Lt. Ralph Jennings, who has been reported missing. The letter stated that Lieutenant Jennings went down with his ship when it crashed in the ocean with one motor gone and the second one shot out. The gunner said he tried to extricate Jennings, but could not and that the officer was knocked unconscious when the plane hit the water. Other crew members were able to get out in rubber rafts.

Based on Luzon, Lieutenant Jennings had completed more than 50 missions in a B-25 in the Pacific theatre.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

On March 23, 1945 … 9 Nisan 5705

F/O Samuel Harmell (T-003337) – Killed in Action

– .ת.נ.צ.ב.ה. –

…Tehé Nafshó Tzrurá Bitzrór Haḥayím

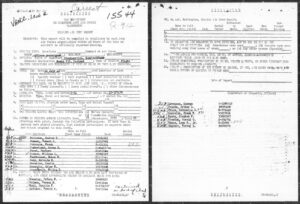

Irony: Four days after making a statement about the loss of Lt. Jennings and S/Sgt. Weinberg, F/O Harmell would himself become the subject of such a document: He and his gunner, Cpl. Harold W. Scott, were killed when their Havoc, A-20G 43-9040, was shot down during a ground support mission in the vicinity of Cebu City, on, Cebu Island, (again) in the Philippines.

As described in the historical records of the 673rd Bomb Squadron:

CEBU CITY (Cebu Island) was hit by nine A-20s in a ground support mission on March 23rd. One bombing and strafing run was made with nine planes abreast and minimum altitude. Small fires were started in the town when 544 twenty-three lb parafrags and sixteen 250 lb Napalm bombs were dropped with 17,400 rounds of .50 caliber ammunition expended in strafing. Speed over target prevented further assessment of damage. One plane returned eighty parafrags and two Napalm bombs owing to electrical failure, while another plane returned 16 parafrags because of pilot error. Propaganda leaflets were dropped and photos taken. Moderate, intense, medium and inaccurate antiaircraft fire were encountered below and behind the flight over MAYONDON POINT. Immediately after starting the bomb run, Flight Officer Samuel Harmell’s plane was hit by antiaircraft fire in the left outboard wing tank which broke into flame. Formation leader instructed the pilot to head for the sea, but he continued to press his attack and then attempted to ditch south of the target. Meanwhile, corporal Harold W. Scott bailed out just before the breakaway from the target and was seen to parachute approximately 1 ½ miles west of CEBU CITY. About thirty seconds later, the left wing tore loose from the plane as it turned on its back and crashed into the water 2 ½ miles southwest of CEBU CITY. The pilot was killed, while nothing more is known about the gunner’s fate.

______________________________

The loss of 43-9040 is covered in Missing Air Crew Report 13532. This statement about the plane’s loss is by Capt. Frank D. Upchurch, Jr. …

On the morning of 23 March 1945 I was leading a formation of A-20s in a strike on Cebu City, Cebu Island. Just as we got within range of the target I glanced over the formation and saw the plane in which Flight Officer Samuel Harmell was pilot, was on fire on the left wing. I observed the plane at several times as we went over the target and it was still burning. As we were leaving the target I was in contact with Flight Officer Harmell at several times and as he asked if his gunner (Sergeant Harold W. Scott) had bailed out, I saw the gunner leave the plane at a very low altitude, approximately 300 miles per hour air speed, and his parachute seemed to open almost at once. After continuing about 1 ½ miles, I saw the left wing of the plane crumple, but did not see the plane actually crash.

______________________________

… while this statement is by 2 Lt. Richard M. Fischer:

On the morning of 23 March 1945 I was leading a flight of A-20s in a strike at Cebu City, Cebu Island. As we started over the target, my left wingman, Flight Officer Samuel Harmell, must have been hit in his No. 1 outboard tank by the first burst of antiaircraft fire. I saw a long string of yellow flame coming from his left wing, and immediately ordered him to ditch the plane. We passed over the target and just at the edge of the sea, the left wing dropped off the damaged plane, causing it to crash immediately from a very low altitude, at a location approximately 2 ½ miles southwest of Cebu City on Cebu Island. I did not see the gunner of the plane bail out.

______________________________

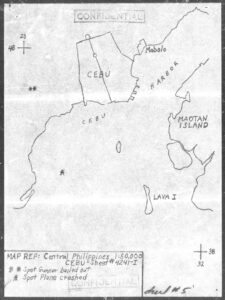

From MACR 13532, here’s a map indicating where 43-9040 was lost. The plane crashed into Cebu Harbor at a location denoted by the lower asterisk, while the location of Cpl. Harold W. Scott’s bailout is indicated by the asterisk in the upper left center.

Another small scale map of the Philippines, this time indicating the general location of the 417th’s destination on March 23, 1945: Cebu City, on the island of Cebu.

This map shows a closer view of the location of Cebu City…

…while this map, at a vastly larger scale – based on the map in the MACR – shows the approximate locations where Cpl. Scott parachuted from 43-9040, and, where the aircraft crashed into Cebu Harbor.

Here’s an even closer view of the above map. Comparing the MACR map of 1945 with this contemporary map of 2023 reveals the creation of an area known as the Cebu South Road Properties, a reclamation area extending into Cebu Harbor from the original shoreline.

This six-minute-long video – “South Road Properties | Cebu City Philippines | Aerial 4K Cinematic Drone Shots” (from September 24, 2021) – from Open Doors, a YouTube channel covering Philippine real estate, provides aerial views of the South Road Properties reclamation area. Though certainly not the subject of the video, its several views of the South Road Properties waterfront include scenes of the area where Chadwick 2nd crashed into the harbor. I’ve cued the video to commence at such a point – specifically, 1:33 – where a small ship headed northeast and parallel to the waterfront lies in the center of the image. Granting uncertainty, I believe the location of the ship at this point is very close to “the”, or indeed “the” area of Chadwick 2nd’s fall.

Though I don’t have access to his IDPF, it would seem that Cpl. Harold W. Scott’s fate was never determined, for he is still listed as missing in action and his name is commemorated on the Tablets of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery. From Allendale, New Jersey (according to FindAGrave), based on a Draft Card found at Ancestry.com he may have been born in Brooklyn in 1919 (?), resided in Hackensack, and been employed by the New York Central Railroad. Even granting the vanishingly low probability that he survived a low-altitude, high-speed bailout from his burning Havoc, in light of the treatment accorded by the Japanese to captured Allied airmen, he would absolutely never have survived – for long, if at all – capture in such a situation.

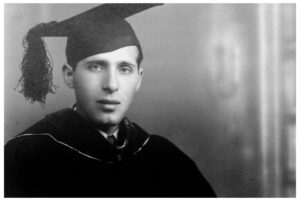

Born in Los Angeles on June 10, 1924, Flight Officer Samuel Harmell was the son of Louis (“Larry”) (10/13/00-4/83) and Etta (Herman) (1906-8/17/89) Harmell and brother of Harold, the family residing at 1214 Ridgeley Drive in L.A. Commemorated on the Tablets of the Missing in Manila, he was awarded the Air Medal and Purple Heart, implying that he’d completed between five and ten combat missions. His name appears on page 45 of American Jews in World War II. Though his high school graduation portrait can be found at Ancestry.com, the resolution and quality of the image are too poor to merit inclusion in this post.

Given the passage of decades, the only surviving records of his existence on this earth may be his statements in the two Missing Air Crew Reports quoted in this post.

References

Dublin, Louis I., and Kohs, Samuel C., American Jews in World War II – The Story of 550,000 Fighters for Freedom, The Dial Press, New York, N.Y., 1947

Freeman, Roger, Camouflage & Markings – United States Army Air Force 1937-1945, Ducimus Books Limited, London, England, 1974 (“Douglas A-20 Havoc U.S.A.A.F., 1940-1945”, pp. 169-192)

Green, Eugene L.; Keane, Paul A.; Callahan, Lewis E., The Sky Lancer – 417th Bomb Group, published in Sydney, Australia, 1946 (publisher unknown)

Green, William, Famous Bombers of the Second World War – Second Series, Doubleday & Company, Inc., Garden City, N.Y., 1969 (“The Douglas A-20”, pp. 59-71)

Rust, Kenn C., Fifth Air Force Story, Historical Aviation Album, Temple City, Ca., 1973

And otherwise…

AFHRA Microfilm Roll A0652, frames 453-455