“You have excellent weapons!

Imagine a Jew given an opportunity to fight from an airplane!” …

… “You envy me my weapons and I envy you your hatred which is pure and fiery.”

__________

“…I was determined to carve out at least one clear image that might serve me in time of need,

when my anger faltered again and the corrupt thoughts of survival came to plague me.”

Sergeant Ben Isaacs, Face of a Hero

____________________

Here’s an excellent depiction of a 450th Bomb Group B-24 Liberator, showing the markings carried by the Group’s aircraft in the closing months of the war. The image displayed here, the “box art” of Hobby Boss’ 1/32 B-24J plastic model, shows aircraft 44-40927, “MyAkin?” of the 722nd Bomb Squadron, identified as such by the two-digit plane-in-squadron number, “51”, on the rudder. The panting immediately reveals why Louis Falstein dubbed Sergeant Ben Isaacs’ imaginary Bombardment Group the “Tigertails”: Note the vertical yellow and black stripes on the fin and rudder, and similarly colored horizontal stabilizers and elevators.

Nose art of the real MyAkin?, from the 450th Bomb Group Memorial Association.

The real MyAkin? was flown by the crews of Jack G. Kath and James L. McLain, the latter’s crew including navigator Lieutenant David Fanshel. Dr. Fanshel wrote an absolutely superb memoir of his experiences as a combat aviator in the European (Mediterranean, really) Theater of War, which – as the only Jewish member of his crew – can be viewed as the non-fiction counterpart to Face of a Hero, though obviously from an officer’s vantage point. His substantive, deep, and thoughtful book – Navigating The Course: A Man’s Place in His Time – is still available through Mz.Bezos.Store. Not a plug: Truly a great book.

Lt. David Fanshel in 1944 or 1945, from his biography page at the 450th Bomb Group Memorial Association.

You can gain a glimpse of Dr. Fanshel’s superb writing via his essay, “In the Vortex of History“, at the Cottontails website. He passed away in 2013. Here’s an excerpt, which has remarkable resonance with what Louis Falstein penned decades earlier. I’ve italicized the most telling passages:

When I come to understand my father’s letter it shakes me up. In the mixture of his improvised Yiddish-English writing, he is able to convey an intense anguish. He specifically addresses my status as an active participant in the air war against Germany and defines my purpose in being in Italy. Not having the foggiest notion of my duties as a B-24 navigator on combat missions, he nevertheless wants me to do everything I can to wreak havoc on the enemy. He wants me to kill all the Germans I can. Personally! It is as if he imagines me somehow throwing our 500-pound bombs from our plane.

***

I have not mentioned my father’s letter to any members of my crew. I reason that we are all honorable and have our own individual motives for flying combat missions in Italy. I do not feel comfortable in seeking to define for my crewmates the nature of their motivations for risking their lives. For some men of the 450th Bomb Group it is a macho thing: “It is manly to engage in combat and fight for one’s country. Combat is not for sissies.” … “The guys at school signed up and so did I.” For many others, enlisting in the military is an expression of patriotism: “My country was at risk, and as a good citizen I had to participate in its defense.” Some men present a more self-serving stance: “I was going to be drafted anyway so I chose air combat because something about it was more preferable to fighting in the infantry. It seemed to offer a cleaner life.”

Hyman’s letter is disturbing to me in ways I do not fully fathom. I sense that a paradox is operating within my psyche. Here I am in Italy participating in the death and destruction associated with the Allied bombings taking place over German-occupied Europe. Dozens of flying comrades in the 450th have been killed in the course of a few weeks after our arrival as a replacement crew. And having seen Colonel Snaith’s plane receive a direct hit with the apparent loss of all aboard, I ask myself: Why should the news of the death of two children I have never met create such an intense emotional reaction? [Here, David Fanshel is referring to the loss of the 721st Bomb Squadron B-24H Liberator flown by Lt. Col. William C. Snaith over Rumania on July 15, 1944. The only one survivor of the eleven airmen aboard this aircraft, “Strange Cargo“, serial number 42-51153, the loss of which is covered in MACR 6995, was Lt. Col. Snaith himself, then the Operations Officer of the Cottontails.]

For days after receiving my father’s letter I have weird dreams about direct encounters with him. Like Hebrew prophets of biblical times he shouts his cry of despair in the language he normally uses with me. In Yiddish, the words enter my inner being in more penetrating fashion than if delivered in his broken English. “Meer muz harginin de Deitcher. Zeyzennen merderers fun kinder. Zoizey farbrendt verren in gehenen!”

Self-conscious and unsure of myself, I do not think I can successfully convey to my crewmates an understanding of the hodge-podge of circumstances, foreign to their experience, that are background to what has taken place in our family. They are more securely rooted in the native soil of our country than I am. In this context, I recognize that the men I am fighting with are not in Italy to save the Jews of Europe. I do not see this as an expression of anti-Semitism but rather as a reflection of the irrelevance of the subject in their lives.

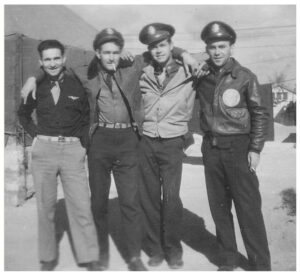

[Lt. David Fanshel (far right) and his fellow officers stand for a snapshot at Manduria. Left to right: Michael J. Heryla – Bombardier, Jim Dunwoody – Co-Pilot, Jim McLain – Pilot. Image from David Fanshel’s biography page at the 450th Bomb Group Memorial Association.]

For all my fitting in with my crewmates – we really do get along with one another quite well – there seems to be a lack of self-confidence that I can convey the history of the Fanshels in a comprehensible form. I sense that the exotic nature of the events experienced by my family would have an aura for them of life taking place on another planet: A family wandering in Europe for a year after the Russian Revolution; a young female child dying on the boat coming across the Atlantic; a brother confined for deportation on Ellis Island and whisked out of a window by the bribery of a guard; an aunt left in Russia whose two children are murdered by the fascists; and Hyman as the conveyor of this information.

For all my fitting in with my crewmates – we really do get along with one another quite well – there seems to be a lack of self-confidence that I can convey the history of the Fanshels in a comprehensible form. I sense that the exotic nature of the events experienced by my family would have an aura for them of life taking place on another planet: A family wandering in Europe for a year after the Russian Revolution; a young female child dying on the boat coming across the Atlantic; a brother confined for deportation on Ellis Island and whisked out of a window by the bribery of a guard; an aunt left in Russia whose two children are murdered by the fascists; and Hyman as the conveyor of this information.

My complicated relationship with my father reverberates within me as I go through the war experience. In my ruminations about my family, Hyman clearly gets defined as the bad guy. And yet I feel there is more to our relationship than my earlier rejection of his letter would indicate and something within me argues for his receiving a better hearing. I realize that I do not understand his thinking very well. I sense that in his growing up in Russia he was exposed to the kind of pain we Fanshel children were spared in America.

____________________

Akin to the experiences of Lieutenant David Fanshel, an unarguably central – but hardly the only – theme of Face of A Hero revolves around Ben Isaacs’ identity as a Jew. So… Segueing from Fanshel’s “real-life” reflections and thoughts to those of fictional Sergeant Ben Isaacs, I’d first like to offer a brief “preface” by way of the evocative, short poem “Then Satan Said,” by Natan Alterman.

Namely:

“How will I overcome

this one who is under siege?

He possesses bravery, ingenuity,

weapons of war and resourcefulness.”

And he said: “I’ll not sap his strength,

Nor fill his heart with cowardice,

nor overwhelm him with discouragement

As in days gone by.

I will only do this:

I will cast a shadow of dullness over his mind

until he forgets that justice is with him.”

__________

This is what the Satan said and it was as if

the heavens trembled in fear

as they saw him rise

to execute his plan.

____________________

____________________

Nathan Alterman, from ynetespanol.

Alterman’s poem remains true, as discussed by Daniel Gordis and Zeev Maghen at Israel from the Inside.

And true, it seems, it shall remain, even in Israel; even in the year 2022.

Now, back to Face of A Hero…

____________________

____________________

Sgt. Isaac’s identity as a Jew is manifested in terms of his interactions with his crew members, particularly nose gunner Mel Ginn and flight engineer Jack Dula. There’s a startling character transformation (spoiler alert! – spoiler alert!) in the the latter, who in the novel’s early pages certainly seems to be explicitly and intentionally antisemitic,butt the story’s end has undergone a marked character change, openly expresses entirely sincere concern about Ben’s well being and survival.

A different interaction has an outcome – specifically, a moral and psychological outcome – for which there may be no solution. This occurs through Ben’s encounter with a strangely anonymous crew chief – also a Jew – who poses to Ben a question concerning the implications of flying combat missions over Germany with an “H” (for “Hebrew”) embossed on his dog-tags, which symbol in the eventuality of capture would immediately identify Ben to his Axis (German) captors as a Jew. The crew chief’s encounter with Ben leaves him particularly agitated, for it forces him to confront a possibility that he previously seems to have ignored or calculatedly avoided: The implication of being a Jewish prisoner of war in German captivity. (Well, that’s something I’ve touched upon in numerous prior posts.)

However, paralleling and going far beyond the above two encounters, Ben’s meeting with a group of Jewish refugees is the longest (paragraph wise!), most meaningful, and most emotionally fraught part of Falstein’s novel, at least in terms of the implications of his being a Jew in military service. Obviously based on and extensively elaborated from his real-life encounter (which actually seems to have been very brief!) with Jewish refugees in Italy, as reported in The New Republic in 1945, these passages allow Ben (or, is it Lou Falstein?) to give free expression to his thoughts and beliefs about Jewish identity, and – in the context of the late 1940s – then-contemporary Jewish history.

This primarily emanates from a discussion of the respect and awe with which the refugees hold Ben upon learning that he’s a flier (they incorrectly assume he’s a bombardier, when he’s really an aerial gunner), and, the sense of defiance and pride voiced by a Mr. Weiss, a shoemaker who participated in the Warsaw Ghetto Revolt. The passage is interspersed with Ben’s own thoughts, which are characterized by an empathy for the refugees that is simultaneously mellowed and rendered uncertain by his realization of the sheer distance – not just geographic, but historical; not just historical, but social; not just social, but psychological – between the experiences of Jews of the United States, and, those of Eastern Europe. Specifically, “The victims were the same and so were the sighs. I recognized them and knew them and walked hand in hand with their sorrow. But beyond that, I was a man apart from their world; a “free” Jew, as one of them called me; a stranger from America, the fabulous, safe land where no bombs fell and Jews lived without fear of being massacred, and people ate white bread and meat and slept in peace at night. Were it not for the fact at I was a “bombardier” they would have resented my intrusion.”

Despite all the warmth of the encounter, it does not have an entirely positive outcome. Ben is deeply upset. He goes through a reverie of flashbacks, recalling his youth in the Ukraine, the travails of his family during the Russian Civil War, his grandmother’s suffering and eventual death – in 1920 – after witnessing the terrible suffering of the Jews of the former Pale of Settlement, his own escape from the Ukraine into Bessarabia, and his eventual departure from Europe.

“Stepping back”, it’s difficult to tell here where Lou Falstein ends and Ben Isaacs begins, for I believe that the author imparted knowledge about the Shoah (that was probably available only at the war’s end) into a late-1944, pre-war’s-end scenario. So, while the writing is compelling, in a purely literary sense – in terms of the novel’s flow and sensibility – the feeling is forced and out-of-place. It would’ve made far more sense to set these paragraphs within Ben Isaacs’ postwar, post-retirement reveries about his military service, from the vantage of the 1990s or early 2000s.

Then again, in 1950, for an author to project himself decades forward in time – and then look back – would’ve required a degree of prescience and imagination that would have resulted in a novel immeasurably different from Face of a Hero.

Still, I particularly note the following two sentences, “I wanted to dwell on the story my friend had told me before we parted late in the afternoon. Out of that story of the Uprising I was determined to carve out at least one clear image that might serve me in time of need, when my anger faltered again and the corrupt thoughts of survival came to plague me.”

And within those lines, Ben Isaacs – or was it Louis Falstein? – or was it both? – one can see an anticipation of the thoughts expressed by Nathan Alterman in Alterman’s poem “Then Satan Said”.

So, some excerpts from the novel…

________________________________________

Ben’s perception of himself as an American, then as a Jew, and then as an American Jew, serving in combat against Germany…

Like a young person who rejects thoughts of death,

I tried not to speculate on what would happen to me if I were shot down over Germany.

But for some reason which I could not explain to myself,

being executed as a spy did not hold as much terror for me as being put to death as a Jew.

The Jewish crew chief, whose ship Violent Virgin we were flying on the mission to Munich, whispered to me as I was taking the last nervous puffs on a cigarette before takeoff, “If I was you, Isaacs,” he said, “I wouldn’t take along your dog tags to Germany. If the Nazis bring you down and see that H for Hebrew on them tags, it’ll be tough on you.”

“That’s nonsense,” I said, taking offense quickly, although momentarily I was grateful for his solicitude. “There’s the Geneva Convention setting down behavior toward prisoners of war.” Then I proceeded to explain to him that according to this convention, signed in Geneva by the present belligerents, a prisoner of war was required to give only his name rank, and serial number. And no more. The Germans, we understood, had ways of coaxing information by intimidation, ruse, threats, and physical violence. They threatened to inject recalcitrants with syphilis and other diseases; they put men in solitary confinement, and on occasion they killed “while the prisoner was trying to escape.” I never dwelled on these matters or I could not go on flying. Like a young person who rejects thoughts of death, I tried not to speculate on what would happen to me if I were shot down over Germany.

“But you’re a Jew,” the crew chief said significantly.

“That hasn’t a thing to do with it,” I said, resenting his reminder. “I’m an American.” I suddenly disliked this chubby, inoffensive man for adding fuel to my already considerable fears, for spreading rumors for which he had no proof, and for displaying a persecution complex which always surprised me when I found it among American-born Jews.

I dismissed his warning and thought no more about it until we started crossing the Alps into Germany proper. Suddenly I took off my identification tags, without any thought or reason, and dropped them in one of the dark crevices on the turret floor where nobody would find them. My action was completely irrational, influenced no little by the terrifying mountain peaks that rose to a height of sixteen thousand feet. The Alps looked like a monstrous forest of jagged rocks jabbing up at us, as if they were the first harbinger of what was to follow once we entered the enemy land.

Aside from the dog tags I had no other identification with me, and according to the same Geneva Convention which I had quoted to the ground man earlier that morning, my captors were entitled to execute me as a spy. But for some reason which I could not explain to myself, being executed as a spy did not hold as much terror for me as being put to death as a Jew. I hadn’t the slightest idea what they did to captured American soldiers of Jewish extraction. I started cursing the crew chief who was safe, back in Italy. I ground the metal dog tags with my fleece-lined boot, mumbling crazily to myself: So the Nazis will inject syphilis in my veins. They’ll kill me. They’ve killed six million Jews already; this will make it six million and one. The point is: one must act with dignity. Remember: in the face of threats or intimidations you tell them only name, rank, serial number; name, rank, serial number; name, rank, serial number… (pp. 54-55)

***

Ben’s encounter with Jewish refugees in Italy…

Twenty-five years!

And nothing had changed.

The victims were the same and so were the sighs.

I recognized them and knew them and walked hand in hand with their sorrow.

But beyond that, I was a man apart from their world;

a “free” Jew,

as one of them called me; a stranger from America,

the fabulous, safe land where no bombs fell and Jews lived without fear of being massacred,

and people ate white bread and meat and slept in peace at night.

Were it not for the fact at I was a “bombardier” they would have resented my intrusion.

“You have excellent weapons!

Imagine a Jew given an opportunity to fight from an airplane!”

You envy me my weapons and I envy you your hatred which is pure and fiery.

On the way to the camp along the rocky coast of the Adriatic while the jeep was churning our breakfasts inside of us, I almost told the driver to turn back and forget about this mission. But something drew me irresistably to these people.

We came upon the camp suddenly. There weren’t any wires or compound. The camp headquarters, workshops, and synagogue were all located in a large villa overlooking the sea. Almost two hundred Jewish refugees, escapees from Germany, Austria, Yugoslavia, concentration camps, and the Warsaw ghetto, worked in or about the crumbling old villa. The general manager of the camp, a Mr. Weiss, introduced himself to me in a soft Yiddish. He had been a shoe manufacturer in Belgrade. For some inexplicable reason he wore a mustache which had a painful resemblance to Hitler’s. He marched me into the hall holding my arm and telling me proudly how their workshops were all busy and producing. “Would you believe it,” he exclaimed, “our co-operative here is self-sufficient? Yes, absolutely self-sufficient! We take your American and British discarded articles, like clothing, shoes, wires – but only discarded – and create new clothes and shoes and bedsprings and toys. We depend on no one.” He kept squeezing my arm, emphasizing the self-sufficiency of the camp as if that was of paramount importance. “All those who can work are busy. But we have many old people who cannot work any longer. Most of our young people have been slaughtered by him. Oh, what great woes he has caused us!” The word Hitler was not mentioned; Hitler was referred to as he or him.

Mr. Weiss let go of my arm and summoned the few old people who were wandering about aimlessly in the hall and corridors of the villa. “Follow me,” he said eagerly. “We are honored today. An American Jew has come to see how his brothers live.” The old people stirred. They followed Mr. Weiss into the hall reluctantly. Curiosity had been wrung out of them, as was the zest for living, I thought, watching them move slowly in response to the manager’s summons. At that moment I was sorry I had come; I felt like an intruder; I felt looked upon as an intruder from another world that did not know the smell of crematoria and the yellow Star of David. And if they resented me I did not blame them. They were the survivors of the six million slaughtered Jews, not we American Jews.

Mr. Weiss said something about “the guest,” referring to me, and a few of the old people began to show some curiosity. They formed a circle, touching me, fingering my gunner’s silver wings and my chevrons; all this performed in grim silence. Finally an old man with little goatee murmured, “A Jew … A free Jew, yes?” He whispered the words, weighing them on his tongue as if the sound of them was the proof of his surmise.

“He’s a flyer,” said Mr. Weiss proudly, “and he’s been bombing him!”

“A bombardier!” a little old lady exclaimed. “A bombardier, God bless him!” She suddenly began to weep, grabbed her skirts and ran out summoning the younger folks in the shops down the corridor. “A Jewish bombardier who has been bombing him has come to visit us!” She screamed and pointed toward us. “There he is! May he live to one hundred and twenty, Riboinoy shel Oilom. Come, Jews, behold him!”

I stood in the center of the hall surrounded by people who were hurling questions at me; people, particularly the old ones, touching me as if I were a curio or a statue, a man from another world, a world from which they had been torn. They kept hurling the word bombardier at me and I nodded, realizing how silly it would be to tell them I was a gunner who fired bullets and not the man who dropped bombs. They wanted a bombardier for that was the symbol of striking back at him. The bomb! I remembered how while we were in Tunis some black Jews had stopped us on the street and inquired: “And which one of you is the bombardier?” And when Dick Martin had responded, rather sheepishly, they had blessed him and promised to say a prayer for him.

“Do you know, son,” said an old man tugging at my sleeve, “six million of your brothers and sisters are slain? Remember that, my son, when you drop those bombs on him.” He pulled at my sleeve as if he had a secret to tell me which could not be shared with the crowd. “I see your bombers going over the Adriatic each morning,” he whispered. “I make my business to get up early to see them. Everybody asks me: ‘Chaim, why do you rise so early, almost in the middle of the night?’ But that’s my job. I guide you across the Adriatic by saying a prayer to the Lord. And when you’re safely across, I go back to bed. It’s the least I can do.”

I’m from Vienna,” a middle-aged man with thick-lensed glasses said to me. “I make bedsprings out of telephone wire. In Vienna I had one of the largest furniture stores. Have you ever bombed Vienna?” I nodded. His face lit up. “Ah, gut! Gut! I have a great house there, but I do not care. Bomb it. He is there! I do not care if you destroy the house so long as you wipe out the evil genius. I don’t care about the house at all.” Suddenly he grasped my hand and cried: “Thank you! Thank you very much!” (pp. 152-154)

***

“Young man,” a little wizened woman piped, “would you do me the honor and visit our casa? My husband can no longer walk. I would like for him to see a Jewish bombardier.” At the casa, in the one room occupied by two army cots, they offered me an orange. It was the only food they had. “Take it, take it,” the old woman insisted. “You need the strength.”

Then she sat on the cot and rocked slowly, and the wrinkled face and the shawl on her head suddenly made me think of my grandmother. The similarity was striking and overwhelming. My grandmother had died twenty-four years ago, but the sigh was the same and the rocking motion, the upper part of the body moving forward and back, was the same. The sigh was a lament passed on with generations like a cherished heirloom. Listening to the old woman sigh I remembered my grandmother. And strangely enough, the only audible sounds I remembered about my grandmother were her sighs. She had sighed more than she talked. She had sat in the marketplace in that small Ukrainian town, clad in coarse, patched clothes, huddling over a container of coal, her frozen red hands buried in the sleeves. She had sat there and rocked and sighed, and waited for someone to buy her clay pots. I had never seen her make a sale. Once, when I asked my grandmother why she sighed, she regarded me soberly and replied, “My child, a Jew who does not sigh is not a Jew.” I was five or six at the time and the explanation puzzled me. “But I’m a Jew, and I don’t sigh,” I said. “One becomes a Jew slowly,” she said in her kindly, patient voice. “One is not only born into it. One is beaten into it.”

And now again I was tempted and I asked the question: “Tante, why are you sighing?”

The little old woman considered my question with that rocking motion and replied, “I do not need to sigh. After all these years of woe it sighs by itself.”

A quarter of a century separated my grandmother from the little old woman who sat rocking despondently on an army cot in a Displaced Persons Camp somewhere in Italy; twenty-five years and another war and a continuous flood of tears. But little else differed between them. My grandmother had died in 1920, soon after her offspring fled from the Ukraine. Hers had been a life of woe, poverty of the crudest kind, denial, and ghetto. In her declining years she had seen her people decimated by mercenary bands of Petlura, Denikin, and others. In one aspect my grandmother had been lucky. Her children had fled to America, to a haven. Later, death had come as a merciful gift from God. My grandmother had been more fortunate than the little woman in the DP camp. This one lived to see six million of her people exterminated; her own kin burned in his ovens while she and her husband had been spared. My grandmother had found her haven in merciful death. But this poor woman had no home. Her home was where she could sigh and rock, sigh and rock.

Had nothing changed? Across the space of twenty-five years the memory of the camps and depots and hiding places choked with refugees came back to me. The gaunt, terrified faces hurled me back to the days when we ourselves lived in fear and slept with our clothes on in attics and cellars ready to flee when the alarm sounded. From 1917 until 1920, when civil war raged in the Ukraine, it was a time of hiding in dark places and learning bewilderedly that for some reason a Jew must cower and hide and fear for his life. I had learned this before I learned my ABCs. And after that there were five long tortured years as a refugee. There was the crossing of forbidden borders from the Ukraine into Bessarabia, and the hunger for bread and home, of being separated from my parents, of being consumed by lice and vermin, of drinking water out of scummy puddles, of sleeping in gutters and haystacks and caves, of begging, of stealing food. And all along the route there were the gaunt, terrified faces in the refugee camps where old people sighed and rocked, sighed and rocked. And after that, how many years had it taken to shed the word “refugee”?

Twenty-five years! And nothing had changed. The victims were the same and so were the sighs. I recognized them and knew them and walked hand in hand with their sorrow. But beyond that, I was a man apart from their world; a “free” Jew, as one of them called me; a stranger from America, the fabulous, safe land where no bombs fell and Jews lived without fear of being massacred, and people ate white bread and meat and slept in peace at night. Were it not for the fact at I was a “bombardier” they would have resented my intrusion.

Mr. Weiss led me to the shoe-repair shop. “I want you to meet a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising,” he said. “One of the very few. You do know about the Uprising,” he said, looking at me dubiously. (pp. 154-155)

***

“Of course I do,” I said.

“We Jews must be very proud of it!” the manager said hastily as if to appease any indignation that might have been aroused in me by his patronizing question. “It ranks with the feats of the Maccabees and Bar Kochba. It shattered once and for all the false legend about Jews not being fighters. This nonsense about the Jews being passive!” he said, stopping in the middle of the road. “We must tear that word passive out of our vocabulary. Enough! We’ve had enough of it! Our fathers raised us on it; we got it with the milk of our mothers, and it was all false. The meek shall not inherit the earth! Often our people were massacred while they were in their temples praying. Slaughtered like sheep. Our wise men taught us to respect the Word; to love the Word. But while we sat in our yeshivas and learned the Word, the enemies were building cannon.” He broke off the tirade and ran ahead, as if he were done with the nonsense of emotion and was in a hurry to lead me to another of the many interesting points in the camp. “Come on, you will meet this man who fought in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Let him tell you about it!”

I followed Mr. Weiss into the small alcove which had been turned into a shoe-repair shop. A young man in his late twenties sat on a low stool, driving nails into shoes. He looked up and stared at me; after we’d been introduced he went back to his nail-pounding. I sat down and reached for a cigarette and offered him one. He took it unsmilingly and his eyes rested on me again. His eyes were hard and they made him appear old. I started the conversation, about shoes, of all things, while, in fact, I wanted to hear about the Uprising. But I felt as soon as I’d sat down that he resented me and would not talk about that event. I pound nails into shoes,” he said to me harshly, “but it is a gun I want!

“You were in the Warsaw ghetto,” I said.

“That’s a pile of rubble!”

“You were in the Uprising,” I said, trying to bring him around.

“So were forty thousand others,” he said.

“Why are you interested in the past? Tell me better how I can throw away these nails and shoes and get a gun and fight those who murdered my wife and child. The past does not interest me. Why are you here?”

I told him about our crash landing, the hospital, and three-day rest.

He was silent for a while, ignoring me completely. Then he said, “You have excellent weapons! Imagine a Jew given an opportunity to fight from an airplane!” His blue eyes suddenly lost their hardness and the webs on his face melted and there was a suggestion of a smile, but it wasn’t really a smile. Nobody in the DP camp smiled, not even once; perhaps their facial muscles were no longer capable of smiling; time and circumstance atrophied those muscles. “You have wonderful weapons!” he said, pounding the nails fiercely on the shoe leather. “What more could a man ask for?” He looked at me across the little wooden partition and I wondered whether this man from another world, this stranger and yet brother, suspected that I was unworthy of the wonderful weapons. Perhaps he was aware why I was there, seeking courage from him and the others, trying to rekindle my anger and sustain my passion.

“A man needs much more than weapons,” I wanted to tell him. “Hatred, like love, is a delicate thing. It must be nourished and tended; it must be fanned and kept glowing. Strange, how very strange. You envy me my weapons and I envy you your hatred which is pure and fiery. The crematoria has robbed you of your loved ones, and the barbed-wire fences of the concentration camps and DP camps removed you from the world, but you took with you that pure anger and fanned it and made it into a glowing, searing flame. Your wives bore children in the shadow of the death ovens – in defiance – and suckled your young ones on the milk of anger. I envy you because for you there is no rationalizing, no choice, no retreat. For you the essence of living is resistance – and if I could achieve that state I might indeed consider myself fortunate.”

The shoemaker hardly said another word. But when I got up to leave, he followed me outside the villa and ran down the road after me.

“I didn’t want to talk in the presence of the others,” he said. “But you must do me a favor. There is a Jewish brigade fighting up north. I’d like to get in that brigade. Will you help me? Perhaps you can prevail upon the higher-ups to assign me. I’m an excellent shot, a sharpshooter, in fact. Please, I’ll be forever grateful to you, I, I’ll never forget you. If I remain here, pounding nails into shoes, I’ll go insane.” We stopped on the road. Around us were the soft, tender little noises of peace: the birds, the lazy palms, and the sparkling Adriatic. And we stood there momentarily, oblivious of the peace. The fact is,” my friend said, “we have enough young people right here in this camp to make up a squad. But the British will become suspicious if many of us run away. And I can’t wait. If you could arrange to smuggle me up to Naples in one of your trucks, I’ll get up to the Brigade somehow.

“But how is it possible?” I said helplessly. “Naples is two hundred miles north of here. Besides, the Brigade consists largely of Palestinian Jews, under British command. And they’re up around the Po Valley – “

“You can’t refuse me,” he implored, “I’ll die if I remain here.”

I shrugged my shoulders impotently and lied, saying, “I’ll speak to people. I’ll try.” And we shook hands, my friend and I, and suddenly we embraced. We walked up the alien road, arm in arm, and he told me about the Warsaw ghetto… (pp. 156-157)

***

The impact of this encounter upon Ben…

This was the one reassuring aspect:

waves rolling against the shore sounded alike everywhere.

Closing your eyes

you could well imagine yourself listening to the waves of Lake Michigan beating against the dunes,

or the slightly more angry variety of waves at Miami Beach in late September.

They were like the South Atlantic waves I heard in Belem and Natal in Brazil,

or the Tyrrhenian Sea waves licking the shores not far from our base.

Theirs was the kind of Esperanto you understood and did not need to translate.

But everything else seemed out of joint, unreal, incongruous.

I wanted to dwell on the story my friend had told me before we parted late in the afternoon. Out of that story of the Uprising I was determined to carve out at least one clear image that might serve me in time of need, when my anger faltered again and the corrupt thoughts of survival came to plague me.

In the evening there was a moving picture on the terrace of the officers’ hotel. The dialogue and the music reached up to our room and mingled in my mind with thoughts of the Jewish DPs. It was a most fantastic setting: dialogue of a Western thriller, thoughts of refugees, Santa Casada. I lay in bed, my eyes shut, but I could not sleep. The only aspect in the whole mosaic that did not seem fantastic was the roll of the waves against the shore. This was the one reassuring aspect: waves rolling against the shore sounded alike everywhere. Closing your eyes you could well imagine yourself listening to the waves of Lake Michigan beating against the dunes, or the slightly more angry variety of waves at Miami Beach in late September. They were like the South Atlantic waves I heard in Belem and Natal in Brazil, or the Tyrrhenian Sea waves licking the shores not far from our base. Theirs was the kind of Esperanto you understood and did not need to translate. But everything else seemed out of joint, unreal, incongruous. In the movie the bad men were riding, and I could hear the gallop of the horses on the sound track, but before my eyes were the gaunt faces of the refugees and the survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, savagely pounding nails into shoe leather. I pulled the pillow over my head and stuffed the ends of it in my ears to shut out the noises coming from the terrace. I wanted to dwell on the story my friend had told me before we parted late in the afternoon. Out of that story of the Uprising I was determined to carve out at least one clear image that might serve me in time of need, when my anger faltered again and the corrupt thoughts of survival came to plague me. But the picture was vague: for twenty-eight days several thousand Jews, the remains of three hundred thousand, rose against the might of his armies that were hemming in the ghetto. Only forty thousand were left by that time, too late, too late, but suddenly they rose in a final magnificent gesture and struck back. They were entombed behind the ghetto walls and underneath the rubble and corpses of their people. They fought, famished and skeletal, out of the holes in the ground, fought barehanded, but with a fury and a passion that came only from knowing there was no other choice. For a month the whole Nazi garrison of Warsaw blasted at the entombed Jews. But they burrowed in the ground, deep into the death caverns, emerging periodically to hurl their defiance. But soon their homemade grenades and rifle bullets gave out and soon their strength gave out and when the incredulous Nazis finally stormed the ghetto walls, after a month, they found smoldering rubble; not a Jew alive, not a Jew in sight, only a huge, slow pyre with the smoke curling toward heaven the last active token of resistance. “Too late,” my friend had said, “we rose much too late. But at least we fought. And we stunned them. And we killed them.” (pp. 158-159)

Some References…

Falstein, Louis, Face of a Hero, Steerforth Press, South Royalton, Vt., 1999

Fanshel, David, Navigating the Course – A Man’s Place in His Time (ISBN 978-0-972369-6-4), Valley Meadow Press, San Geronimo, Ca., 2010

_____, Navigating the Course – All to the Good (ISBN 978-0-9836786-5-6), Valley Meadow Press, San Geronimo, Ca., 2013

Nathan Alterman…