When you delve into the past, it soon becomes apparent how rapidly knowledge of “what has come before” recedes into the mists of time … even for events that are, in a relative sense, quite recent. I suppose this has always been true. But, I only began to really appreciate the fragility of memory when I embarked upon searching for historical records, biographical information, and personal recollections concerning soldiers who served in the Second World War. (And the Great War. And the Korean War. And so on…)

Military and personal histories are – true – now readily available at the touch of an icon. But, upon a deeper look, the ambiguities, absences, and gaps inherent to knowledge of the past are striking, boldly contrasting with the way in which the Internet creates the impression – or should we say illusion? – of the immediate availability and depth of historical information.

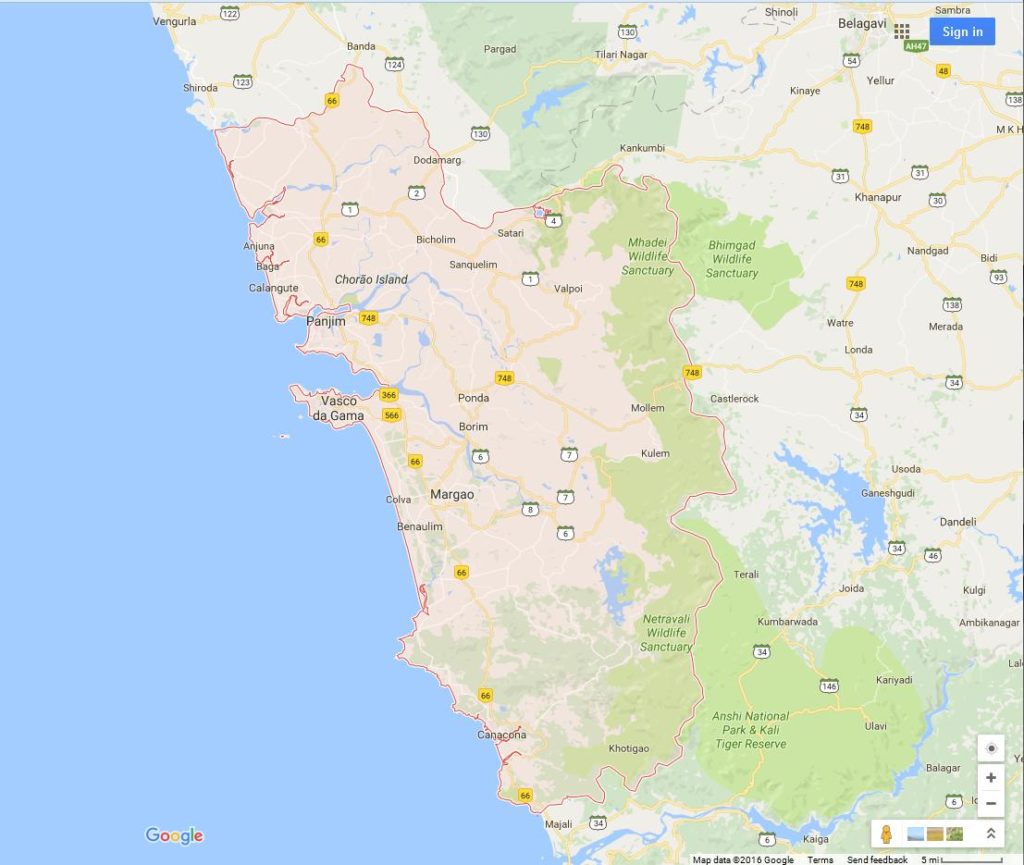

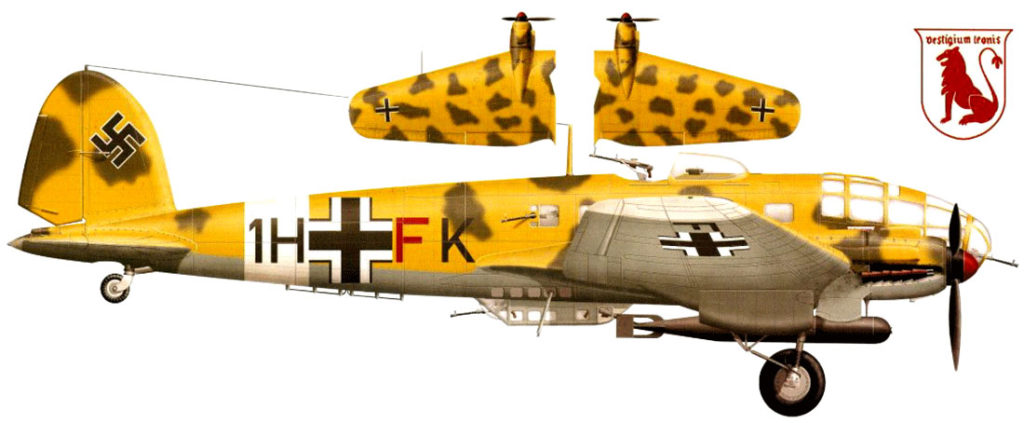

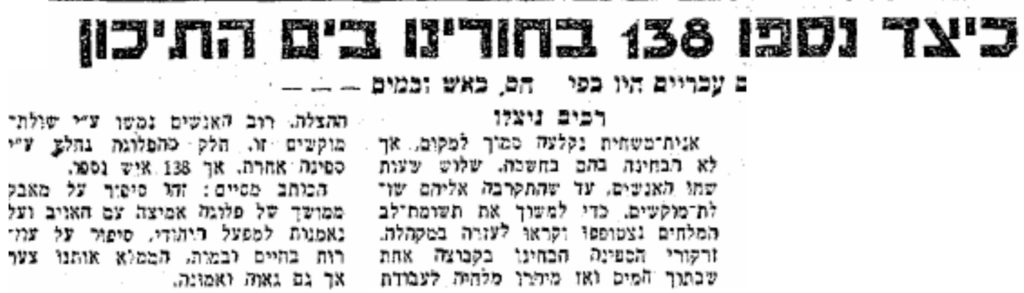

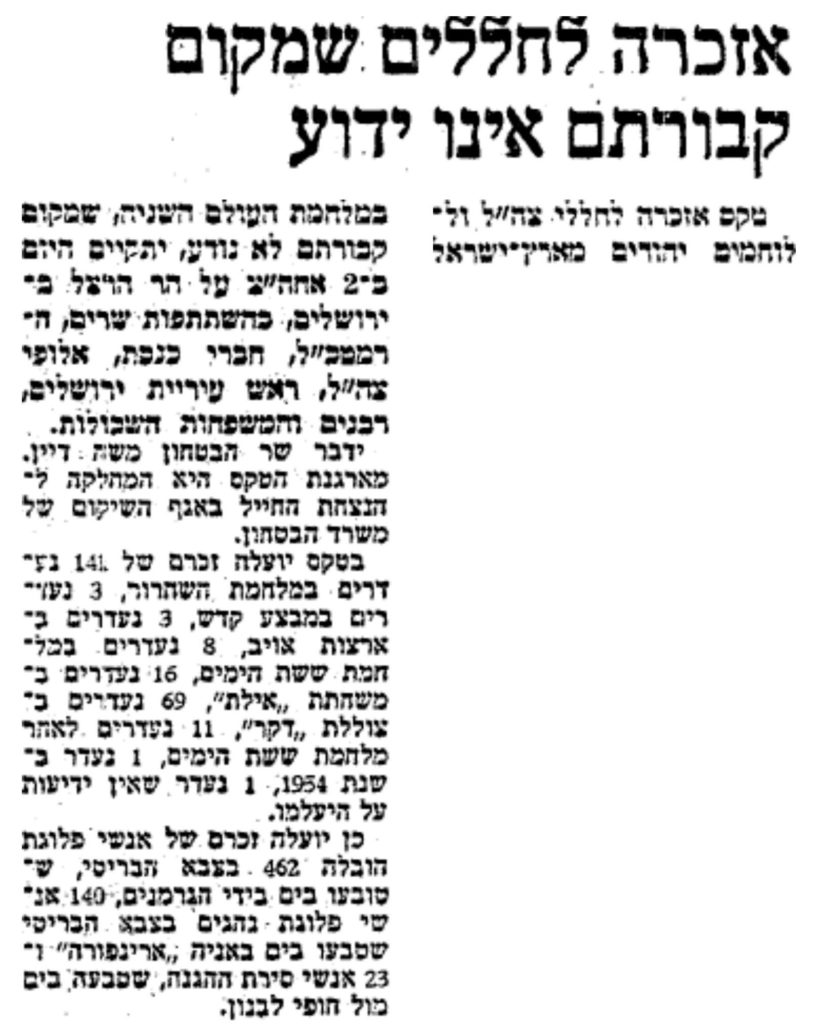

And so, I think back to some of my earliest internet writings concerning Jewish soldiers… These include a series about the S.S. Erinpura, which was sunk by the Luftwaffe of the Libyan coast on May 1, 1943 (Nissan 26, 5703), with the loss of several hundred soldiers from the Yishuv, and, Africa. Of the 138 Jewish troops who were killed in the sinking of this vessel – all members of the 462nd General Transport Company – nominal references or historical records are available for most, primarily in Volume I of Henry Morris’ We Will Remember Them (and a few in its companion Volume II), and, the Israeli Government’s Izkor website, for “The Commemoration Site of Fallen Defense and Security Forces of Israel”. (Very little news about this event appeared in the English-language news media, and – entirely unsurprisingly – nothing whatsoever in the American Jewish press.) After plumbing those sources, I found that there was a small number of soldiers – eleven men in total – for whom genealogical information was unavailable, or, for whom – in eight cases – information was limited to a soldier’s date and/or place of birth.

But of the eleven, one man – the focus of this post – is “anonymous” no more. He was; he is; he remains Driver Victor Chaim Hananel, PAL/31222, born in Istanbul in 1922. This is due to the interest and enthusiasm of his family, particularly Tony Hananel, the daughter-in-law of Victor’s brother Isak (Tony’s husband is Leon, the nephew Victor Chaim never knew), I’m now able to present a picture of Victor’s life through images and words. Though his biography is incomplete, it is a biography nonetheless.

As so, the other soldiers; the currently “unknown” ten, are:

Bohary, Tzvi, Cpl., PAL/10203

Ben-Tzvi, Yaacov, Driver, PAL/32277 – Givat Hashlosha, Israel; Poland, 1922

Buchbinder, Reuben, Driver, PAL/01993 – Iasi, Romania

Chayim, Mordechai / Mordehai (Max), Cpl., PAL/00464 – Kibbutz Givat Brenner, Israel; Czechoslovakia, 1911

Cohen, Raphael, Driver, ME/10670905

Feldman/ Platzman, Yisrael, Driver, PAL/00522 – 1919

Goldshtein / Goldstein, Paul, L/Cpl., PAL/00650 – 1905

Proper, Joseph, Cpl., PAL/00191 – Dinow, Poland, 1915

Schlesinger / Shlezinger, Michael, Driver, PAL/32377 – Jordan Valley, Israel; Vienna, Austria, 4/1/23

Yaacobson (Yaakobson), Hans, Driver, PAL/01206 – Kfar Yedidya, Israel

In that, as suggested by Zelda Mishkovsky’s poem “Every Man Has A Name” – at the “end” of this post – let this account stand as a symbol for those whose life stories remain, for now, unknown.

____________________

____________________

The origins of the Hananel family probably lie in the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, the exiled family eventually settling in Budin (Budin Eyalet). As explained at Wikipedia, “Budin Eyalet (also known as Province of Budin/Buda or Pashalik of Budin/Buda, Ottoman Turkish: ایالت بودین) was an administrative territorial entity of the Ottoman Empire in Central Europe and the Balkans. It was formed on the territories that the Ottoman Empire conquered from the medieval Kingdom of Hungary and Serbian Desperate. The capital of the Budin Province was Budin (Hungarian: Buda).”

The family’s presence in Budin is confirmed by their possession of an Imperial Edict from the 16th Century. This document (see the image below) expresses gratitude to the Hananels and other Jewish families who opened the doors of fortress Budin in 1526, when the Ottoman Empire conquered the city.

In time, the family moved to Constantinople.

In further time, we come to the twentieth century.

Victor Chaim’s father Yuda Leon was the owner of a textile business. He and his wife Rebeka had four sons – oldest to youngest David Danny, Emil, Isak, and Victor Chaim – all of whom attended a French Jesuit School in Istanbul. The three elder brothers were sent to either France or Belgium where they finished their high school studies, subsequently returning to Turkey, where they and their parents survived the Second World War. (Turkey didn’t become an Allied combatant until February 23, 1945.) By the time that Chaim Victor – the youngest – was in middle school, the Second World War had commenced. As a result, he was forced to remain in Istanbul, from where he graduated from high school.

What happened next? In Tony Hananel’s words, “Apparently Victor Chaim fell in love with a young Christian woman and wanted to marry her. His parents objected to the wedding citing that the elder brothers were not yet married and that he had to wait for his turn. Frustrated … he … left Turkey, travelled to Palestine and joined the Jewish Brigade.”

Ironically, though no actual letters remain from Victor Chaim’s sojourn in the Yishuv, with great irony, four bare envelopes which probably contained correspondence replying to the brothers’ inquiries to British military authorities about the fate of their youngest sibling, still exist. Alas, any and all inquiries bore no fruit. As Tony has written, “…Victor’s parents died not even sure of their son’s fate. The brothers clearly knew that he had somehow met his death but nothing of the circumstances.”

As Tony explained, “Had there been any [correspondence between Victor Chaim and his family] though, they would surely not have been in Hebrew as his parents did not speak any Hebrew, but … French, the “lingua franca” of the educated members of the Jewish community,” which was studied in schools of the Alliance Israelite. Alternatively spoken was Ladino, the lingua franca of Sephardi Jews since the late-fifteenth century Spanish expulsion, which would have been the conversational language of Yuda Leon and Rebeka.

The envelopes appear below. All are written in Turkish, with the envelope postmarked May 15, 1944 bearing Turkish postal stamps. Three of the four envelopes are addressed to Victor Chaim’s elder brothers: two to David Danny and one to Isak.

(All images below – with the exception of the first two, both via Geni.com – are via Tony Hananel, for whose work and generosity I want to express my thanks and appreciation.)

____________________

____________________

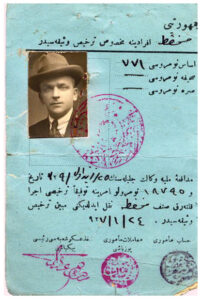

Yuda Leon Hananel, in a photo appearing in a Turkish document – his passport? He died in 1950. (From Geni.com)

____________________

Rebeka (Rivkah) Hananel. (Also from Geni.com)

____________________

The couple’s four sons in 1924: From left to right, David Danny, Victor Chaim, Emil, and Isak.

____________________

Three sons in 1927: Isak, Emil, and Victor Chaim.

____________________

Again in 1927: The four sons.

____________________

Victor Chaim at the age of five in 1927, looking older and wiser than his years.

____________________

Also 1927: Isak and Victor Chaim.

____________________

1928: Yuda Leon and Rebeka with Emil, Isak, Victor Chaim, and David Danny.

____________________

1932 – four years later: Victor Chaim playfully perches atop a pyramid of brothers; Emil is at right.

____________________

The brothers in 1934.

____________________

A pensive Victor Chaim at the age of thirteen, in 1935.

This is the 16th Century Imperial Edict received by the Hananels and other Jewish families in Budin. If you look very closely (right-click and save…), you’ll see that the text appears as twelve double-lines of elegant, miniscule Arabic script, written as if “rising” from right to left, eventually surmounted by a golden key.

____________________

Here are the four envelopes testifying to Victor Chaim’s all-too-brief life. Sent to the Hananel family by British military authorities in the Yishuv or Cairo, the correspondence which they held has long since been lost, but presumably pertained to inquiries from the Hananel family concerning Victor Chaim’s fate. The address on each envelope is written in Turkish. Two of the envelopes are addressed to the Rehber Shop, a department store in Istanbul of which Yuda Leon was a partner.

Sent from Cairo to the Rehber Shop on March 28, 1944, this envelope was addressed to “Marko Levi, Anafartalar Caddesi. Rehber Tuhafiye Mağazası.Ankara”. The envelope bears no return address.

____________________

“On His Majesty’s Service”: The cancellation mark appears to indicate a date of May 15, 1944. This envelope contained a letter that was sent from the “Combined Local Record Office, (“palestine” Section), M.E.F., Filistin”, to David (Danny Hananel?), at Cicek Pazar in Istanbul. Though I’m entirely unfamiliar with Ottoman or Turkish geography (!), Cicek Pazar might actually be – as described at Wikipedia – “Çiçek Pasajı (Turkish: Flower Passage), originally called the Cité de Péra … a famous historic passage (galleria or arcade) on İstiklal Avenue in the Beyoğlu district of Istanbul, Turkey. A covered arcade with rows of historic cafes, winehouses and restaurants, it connects İstiklal Avenue with Sahne Street and has a side entrance opening onto the Balık Pazarı (Fish Market).”

____________________

Another letter to brother David, though with a different address than before: “c/o Elvaşvili. Fındıklayan Han. Cier Pazor, Istanbul.” But, there’s no return address.

____________________

A fragment of a fragment: Sent from Cairo to the Rehber Shop on an unknown date, this letter is addressed to “Tünel _____ No. 5, Rehber, Zolata, Istanbul”.

____________________

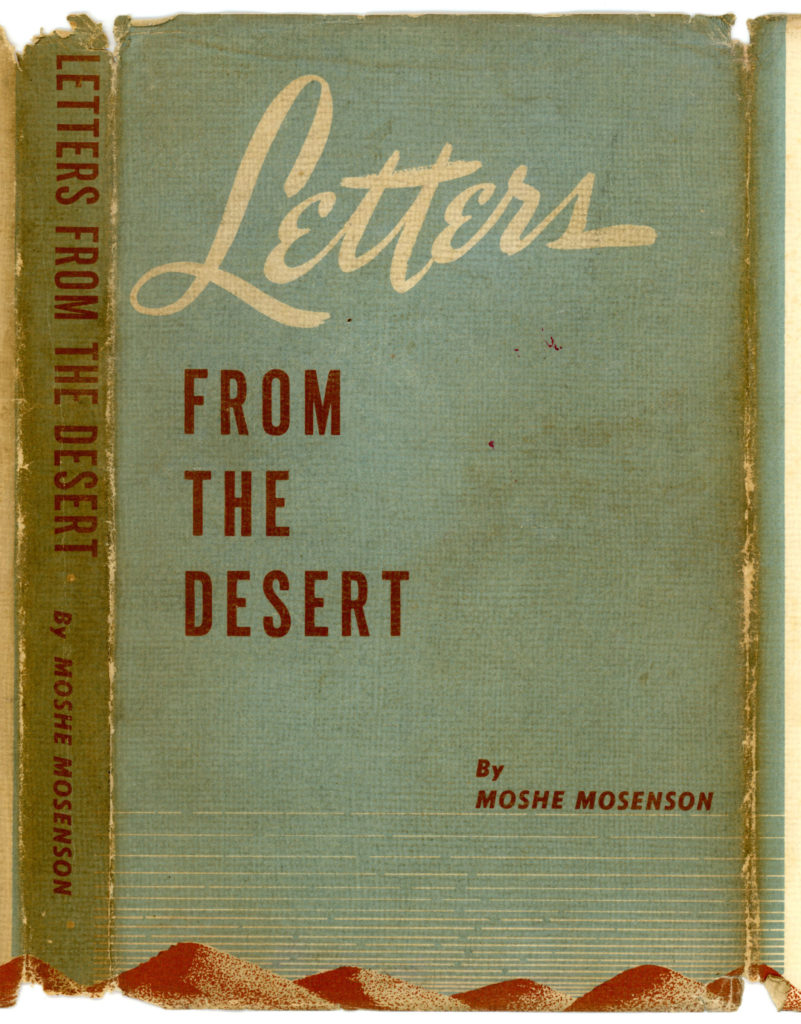

The only direct record of Victor Chaim’s military service in the Yishuv comprises the following four images. Other than his nominal presence in the photos, and, the fact that each picture had (by definition) to have been taken prior to May 1, 1943, each image remains an enigma.

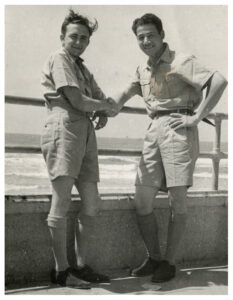

Chaim Victor, holding a cigarette, shakes hands with a friend on a sidewalk overlooking the Mediterranean Sea. Given that the men are wearing shorts, perhaps it’s the summer of 1941 or ’42?

____________________

In the next three images, Victor’s attire (long pants – not shorts), the setting, and the angle of the sun’s illumination suggest that the pictures were taken at the same time and place. Given that the seaside railing in the final two images is identical to that in the image above, it would seem that Victor and the other two soldiers took a liking to this coastal location.

Posing with another soldier at a city street….

____________________

,,,and seated with another soldier. Victor’s shirt bears a shoulder-flash with the word “palestine”.

____________________

I think it’s best to conclude with this fine and evocative photo: Victor Chaim, seated on the railing, with the Mediterranean Sea behind him, is looking directly directly at the unknown photographer (a fellow soldier?).

In the early 1940s, Victor Chaim is looking into the future.

In 2023, we are looking into the past.

And so, two worlds meet, in memory.

1922 – Saturday, May 1, 1943 / Shabbat, 26 Nissan 5703

– .ת.נ.צ.ב.ה. –

____________________

Like other casualties aboard the Erinpura, Victor Chaim’s name is memorialized at the Brookwood Memorial in Surrey, England (specifically at Panel 16, Column 3). Being a Jewish soldier from the Yishuv, he’s also commemorated at the Mount Herzl Military Cemetery, specifically at the memorial to those lost in the Erinpura. His name is also engraved in this stone at Mount Herzl, photographed in 1993.

____________________

____________________

To conclude, a poem.

Every Man Has a Name (לכל איש יש שם)

Every man has a name

Given him by God

And given by his father and his mother

Every man has a name

Given him by his stature and his way of smiling,

And given him by his clothes.

Every man has a name

Given him by the mountains

And given him by his walls

Every man has a name

Given him by the planets

And given him by his neighbors

Every man has a name

Given him by his sins

And given him by his longing

Every man has a name given him by those who hate him

And given him by his love

Every man has a name

Given him by his holidays

And given him by his handiwork

Every man has a name

Given him by the seasons of the year

And given him by his blindness

Every man has a name

Given him by the sea

And given him

By his death.

Zelda Schneurson Mishkovsky

Зельда Шнеерсон-Мишковски

זלדה שניאורסון-מישקובסקי

____________________

____________________

Some References

Leon Hananel, at Geni.com

Rebeka Hananel, at Geni.com

____________________

An Acknowledgement

My sincere thanks to Tony Hananel for her time and effort in providing me with information about Victor Chaim and his (her!) family, as well as excellent scans of photographs and documents from the Hananel family collection. This post would not exist without her interest, enthusiasm, and help.