[Update: Created in November of 2020, this post has been updated to reflect information provided by Andrew Garcia, pertaining to the P-38 that serves as a backdrop for the image of Major Joel and Capt. Joseph Myers, Jr. The picture can be seen towards the (very) bottom of the post.]

Part III: On Course

Now in command of the 38th Fighter Squadron, Milton’s promotion to Major was announced in the Richmond Times-Dispatch, on February 2, 1943.

MAJOR AT 23 – Milton Joel (above) son of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Joel, 5 Greenway Lane, is believed to be one of the army’s youngest majors. He completed his civilian pilot’s course at the University of Richmond in 1939 after attending the University of Virginia. He later trained at Tuscaloosa Field, Ala. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in May, 1941, promoted to first lieutenant in February, 1942, and a captain in June. He is now commanding officer of a fighter squadron at Pendleton Field, Ore.

MAJOR AT 23 – Milton Joel (above) son of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Joel, 5 Greenway Lane, is believed to be one of the army’s youngest majors. He completed his civilian pilot’s course at the University of Richmond in 1939 after attending the University of Virginia. He later trained at Tuscaloosa Field, Ala. He was commissioned a second lieutenant in May, 1941, promoted to first lieutenant in February, 1942, and a captain in June. He is now commanding officer of a fighter squadron at Pendleton Field, Ore.

Flying-battle-axe emblem of the 38th Fighter Squadron, digital…

…and physical, as a patch, available from EBay seller EZ.Collect. (Not a “plug” – I simply found this image via duckduckgo!)

…and physical, as a patch, available from EBay seller EZ.Collect. (Not a “plug” – I simply found this image via duckduckgo!)

________________________________________

________________________________________

Three and a half months after taking command of the 38th Fighter Squadron, on February 19, 1943, Milton and several of his squadron’s pilots gathered for this group photograph, under what seems (?) to have been an overcast sky.

Interestingly, at least four pilots in the rear row (thus all perhaps in the rear row?) were members of the 27th Fighter Squadron (Milton’s former squadron) and attained aerial victories in the Mediterranean Theater.

Interestingly, at least four pilots in the rear row (thus all perhaps in the rear row?) were members of the 27th Fighter Squadron (Milton’s former squadron) and attained aerial victories in the Mediterranean Theater.

Though this image is present in the squadron’s historical records (specifically, in AFHRA Microfilm Roll AO 136) inquiries to the National Archives revealed that it’s absent from the WW II U.S. Army Air Force Photo Collection. Thus, it seems to have remained at squadron level, never having been bureaucratically passed “upwards” to any higher organizational level.

From a technical point of view, the photograph clearly illustrates the counter-rotating propellers used in all P-38 Lightnings commencing with the XP-38, with the exception of 22 of the 143 P-38s which had been ordered by the Royal Air Force as Lightning Mark 1s. As such, viewed from the “front”, it can be seen that the propellers rotate outwards, away from the aircraft’s central gondola and toward the wings.

Another point: It appears that the aircraft’s nose has been painted, perhaps as a form of squadron identification.

The text on the photograph states…

“(G868A – 22M – 33AB) (2-19-43) FLYING OFFICERS, 38TH FIGHTER SQUADRON, PN FLD, WN. (RES)”

…while the back of the image bears the notation…

Restricted Photograph

Do not use without permission U.S. Army Air Force

Air Base

Photo Laboratory

…and includes the pilots’ surnames – and their surnames only. However, this clue enables identification of most of these men. They are:

Front row, left to right (All members of the 38th Fighter Squadron)

Wyche, Wilton E., 0-729407

Ayers, Jerry H., 0-659441

Leinweber, Gerald F., 0-659473

Joel, Milton, 0-416308 (KIA 11/29/43 – MACR 1429 – P-38H 42-67020; No Luftgaukommando Report)

Hancock, James H., 0-659122

“Meyer” (Myers?), Joseph, Jr., 0-659166

Leve, Morris, 0-791127 (KIA 1/31/44 – MACR 2110 – P-38J 42-67768; Luftgaukommando Report AV 641/44)

Rear row, left to right (The four identified men were members of the 27th Fighter Squadron)

Ellerbee

Conn, David M., 0-732171

Meikle, James B.

Connors

Dickie

Crane, Edwin R., 0-728980

McIntosh, Robert L., 0-802054

Harris

Smoot

Hammond

Purvis

Here’s another 38th Fighter Squadron photo, from Robert M. Littlefield’s Double Nickel, Double Trouble. Taken on June 4, 1943 at McChord Field, Washington, these seven men comprise the original squadron commanders of the 38th Fighter Squadron, and, the four officers heading the 55th Fighter Group. Akin to the preceding photograph, an inquiry to NARA revealed that this photograph is absent from the WW II U.S. Army Air Force Photo Collection. Also paralleling the above photo, this P-38’s nose (the plane is a P-38G-15) has been painted – probably – in white or yellow, and bears a (plane-in-squadron?) identification number. Unusually for a stateside warplane, this aircraft bears nose art. This takes the form of Walt Disney’s “Thumper” holding a machine gun, and the appropos nickname “WABBIT”. (Albeit no relation to Elmer Fudd…)

…left to right:

Major Richard W. (“R. Dick”) Busching, 0-427516, Commanding Officer of the 338th Fighter Squadron

Major Milton Joel, 0-416308, Commanding Officer of the 38th Fighter Squadron

Wendell Kelly, Group Operations Officer

Colonel Frank A. James, Commanding Officer of the 55th Fighter Group

Lt. Colonel Jack S. Jenkins, 0-22606, Group Executive Officer

George Crowell, Group Operation Officer

Major Dallas W. (“Spider”) Webb, Commanding Officer of the 343rd Fighter Squadron

________________________________________

This third image, from the collection of 38th Fighter Squadron pilot (and only survivor among the four 38th Fighter Squadron pilots shot down on November 29, 1943 – but we’ll get to that in a subsequent post) John J. Carroll, was taken on July 20, 1943. From The American Air Museum in Britain (image UPL 40377) the photo shows the original members of the 38th Fighter Squadron sent to England in late summer of 1943. (This picture also appears in Double Nickel, Double Trouble.)

Paralleling the above pictures, this photograph is absent from the WW II U.S. Army Air Force Photo Collection. The text on the image as published in Double Nickel, Double Trouble (but not visible on this web image) states:

Paralleling the above pictures, this photograph is absent from the WW II U.S. Army Air Force Photo Collection. The text on the image as published in Double Nickel, Double Trouble (but not visible on this web image) states:

“(G1067 – 22M – 33AB) (7-20-43) FLYING OFFICERS, 38TH FTR. SQDN. (RES)”

The men are:

Front, left to right

Shipman, Mark K., 0-431166

Wyche, Wilton E., 0-729407

Ayers, Jerry H., 0-659441

“Meyers” (Myers?), Joseph, Jr., 0-659166

Joel, Milton, 0-416308 (KIA 11/29/43 – MACR 1429 – P-38H 42-67020; No Luftgaukommando Report)

Meyer, Robert J.

Leinweber, Gerald F., 0-659473

Hancock, James H., 0-659122

Unknown

Rear, left to right

Albino, Albert A., 0-743330 (KIA 11/29/43 – MACR 1428 – P-38H 42-67051; Luftgaukommando Report J 307?)

Fisher, D., (“David D.”), (T-1046) (KIA 1/31/44 – MACR 2106 – P-38J 42-67757; Luftgaukommando Report Unknown)

Brown, Gerald, 0-740139

Unknown

Kreft, Willard L., 0-740219

Erickson, Wilton G., 0-748934 (KIA 12/1/43 – MACR 1430 – P-38H 42-67033; Luftgaukommando Report Unknown)

Erickson, Robert E., 0-743324

Gillette, Hugh E., 2 Lt., 0-740169 (KIA 10/18/43 – MACR 1040 – P-38H 42-66719; No Luftgaukommando Report)

Steiner, Delorn L., 0-740297 (KIA 1/31/44 – MACR 2105 – P-38J 42-67711; Luftgaukommando Report Unknown)

Fisher, (Paul, Jr.), (0-740149)

Peters, Edward F., 0-746168

Peters, Allen R., 0-743368

Carroll, John J., 0-743313 (POW 11/29/43 – MACR 1431 – P-38H 42-67090; Luftgaukommando Report Unknown)

Unknown

Garvin, James M., 0-740164 (KIA 11/29/43 – MACR 1427 – P-38H 42-67046; Luftgaukommando Reports J 338 and AV 513 / 44)

Forsblad, Richard W., 0-740153

Des Voignes, Clair W., 0-743425 (KIA 7/13/44 – MACR 6709, 6717 – P-38J 42-28279; Luftgaukommando Report J 1635)

________________________________________

The 55th Fighter Group departed McChord Field, Washington, for England on 23 August 1943. The Group reached Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, on August 27, remaining there until September 4, when the Group boarded the H.M.T. Orion (a 24,000 ton ocean liner launched in 1934) in New York Harbor, the burned-out wreck of the SS Normandie – renamed the USS Lafayette – visible nearby. The Orion departed the next day, reaching its English base at Nuthampstead on September 14. Milton’s diary verifies these dates and locations.

In this image () a Coast Guard J4F Widgeon flies near the wreckage of the Lafayette, with the Empire State Building faintly visible in the distance. This area is probably the location of the Orion’s departure for England.

In this image () a Coast Guard J4F Widgeon flies near the wreckage of the Lafayette, with the Empire State Building faintly visible in the distance. This area is probably the location of the Orion’s departure for England.

________________________________________

During this hectic interval, Milton kept a diary covering the 18-day trans-Atlantic journey, in which he recorded observations and impressions of people, places, and events, noting the controlled chaos associated with the rapid movement of his squadron and group to a foreign shores. Specifically mentioned (albeit not including first names!) are pilots Willard L. Kreft, Gerald F. Leinweber, Mark K. Shipman, Albert A. Albino, Colonel Frank A. James, and ground officers Octavian R. Tuckerman (Ordnance), and Arthur S. Weinberger (Personnel).

The first two pages of Milton’s diary are shown below, followed by a transcript of all diary entries. Milton’s penmanship was not (!) the best, so the text includes some “gaps” (thus [“_____”]). But, enough of his writing is legible such that the sequence of events, his impressions of people (one observation of human behavior is quite frank by the standards of the 1940s) and sense of activity emerge from the document’s pages, as do his pride in his squadron.

Aug 23-1943 En Route Paine Field to NY P of E

Aug 23-1943 En Route Paine Field to NY P of E

This first entry in the daily record of events and sidelights of my participation in the action toward victory is made with the hope that it will not suffer the ignominity of becoming merely another bit of evidence of slovenly performance & tasks undertaken. At 08:30 AM left Mukilteo Washington in command of the 38th Fighter Squadron. Everyone eager and straining at the bit just as I am. Feel sure we can do a good job of it since I know we are better in a hundred ways than any outfit that has previously left the cont. for foreign duty both in efficiency and spirit. Wish Elaine could have been there to see us off but that would have been an anticlimax. Then too make it a first not to see her after the men were placed incommunicado. What’s good enough for them is good enough for me.

Aug 24 ’43

Trip so far completely uneventful, train shakes so cannot write.

Aug 25th ’43 No change. All serene.

All the men really on the ball – violent bridge game constantly in progress involving _____ _____ [Willard L.] Kreft & [Gerald F.] Leinweber. They have screamed themselves hoarse. Particularly Leinweber now sounds like a fog horn. Sporadic poker games continue on. [Mark K.] Shipman is like a kid just bubbles over with enthusiasm. He wrangled a ride on the engine & stayed there some four or five hours.

Aug 26th Everyone thoroughly encrusted in soot.

We look like miners not soldiers. [Albert A.] Albino & his _____ _____ _____ _____. Shipman worried about poker games _____ as though we should see that pilots learn to take care of their money. Losses haven’t been heavy. _____ (_____) & I talk him out of it. Is indignant when we try to explain that paternalism should not be carried that far. Am proud as pink over the conduct & appearance of the outfit at exercise time at stop by the wayside. Even though they are grimy they are sharp. Leinweber spends waking hour looking for a spoon from his mess kit – 200 pounds of almost _____ _____.

Aug 27th Camp Kilmer, N.J.

– arrived here at 08:05 from then on it was nit & tuck – nip a breath & tuck it away to last for an hour or two when you may or may not be able to catch another. Was met at the station with everything but the brass band.

I.F. a billeting officer, a supply officer, a medical man, a rail transportation man & truck transport man and two or three others for good measure. We whisked the men off the train & marched them off to their barracks. I stayed behind with _____ (Exec. Off) & went through the train with a rail officer & train Rep. & a Pullman Rep. to check for damage. There was none. Dashed madly to new quarters while the rain started to pour. Have a piece of paper shoved at me telling me that I and the whole staff report at 9:00 AM for instruction – Do not have time to even wash off the weeks soot & grime or change clothes.

We report, Larry (_____) S-2, _____ S-1, Shipman S-3 & _____ S-4 & I _____ _____ officer _____ who gives us 2 hours instruction & a thousand sheets of paper (S.O.P. – Standard Operating Procedures).

We receive a schedule for the day which is a killer. Return to barracks Four & officers are just settling down. Tuckerman & Weinberger have just returned with the baggage detail & the baggage and it is all stowed away in our building – Rush away to lunch. Return & going to quit as too tired to continue.

Sept 1 Have decided that war is hell.

If the battling will be as rough as the getting to it. We’ve had at least 6 countermanding orders on our load list, we pack them then unpack. Then pack. Then unpack. That’s the way it goes. Everyone is beginning to get thoroughly disgusted but that’s the way they said it would be.

This camp is tremendous place thousands & 10’s of thousands of men pour through here each week. They are practically re-equipped. It’s amazing really. We had a meeting today and there were at least 300 unit commanders and adjutants. This is going to be a tremendous deal, but big rumors are rampant. Morale however is getting very low. Pilots like a bunch of race horses. They’re tense & at each others throats practically. Mainly due to hanging around with nothing to do & hangovers, everyone having gone to New York last night & night before. I went in. Had a big lobster dinner & a fried chicken but was too tired to stay late.

Sept 14 Haven’t had a moment to do more than write a few words to Elaine.

Left Camp Kilmer on the 4th in the morning for Embarkation. Our B-4 bags & packs were so damned heavy don’t know how we made it. Rode the train to ferry & thence off the harbor to the pier and boarded H.M.T. Orion. Saw the Normandie still lying serenely on her side like some tired old man refusing to get up & go to work. As soon as all the men were aboard I managed to drag my raincoat, briefcase, blanket roll, mussette bag, gas mask, pistol, web belt and canteen aboard half carrying & half falling over my B-4 bag to my stateroom. This was pleasantly surprised by a Staff Sergeant Symanoff who brought me four letters from Elaine. She had a hunch – the _____ _____ _____ that I would come to New York and had contacted Gene Symanoff who worked in the port. That was to prove the greatest treat to date aboard this tub.

No sooner did I get on board ship then was I summoned to Col. James’ [Frank James] room – where I found a great stir & dither. I was informed that I was to be Deck Commander of “E” Deck, which at this time didn’t seem so bad. Was soon to find out just what a rough deal it really turned out to be. Col. James was the senior line officer slated to come aboard and was then made troop commander. We were informed that there had never previously been American troops board ship and in addition there were 2000 more of them than the British had ever conceived of placing aboard. I.E. We had 7000 troops placed helter skelter on the ship and no one with us had ever had any experience of either handling troops aboard ship or _____ _____ any permanent _____. Men had been loaded helter skelter like sardines thrown into the can and then lid forced down. There were not even any set instructions orders or the like. This looks like the goddamnedest mess the brass hats could dream up & was. Went below & found my deck was “double loaded” I.E. 1500 men eat & sleep below deck & 1500 sleep & two above on another deck for 24 hours. All eat below in double shifts of 2 sittings each man shifting the _____ _____ for each of the 2 meals and again in the middle of the day. At night there wasn’t room either below or above to move an inch without stepping on someone’s face 1/2 _____ staying below slept on mattresses on the floor and tables the other half in hammocks. Those above decks slept on blankets on hard decks rain or shine – oh rough – To add to it all compartments on all decks had to pass through my deck to go to & from the galley also the twice daily canteen details also went through all the latrines for EMs aboard ship were also located _____. At meal times shift it looked like 42nd & Broadway on New Year’s Eve. How we ever got any organization is still a mystery to me.

To add to it all men consisted of the raunchiest crew I had ever seen. A larger proportion was criminals most of whom had 2 to 3 court martials against them some of whom even brought on board by armed guard. It was utter chaos. For first 3 days there was utter chaos and it took some days to eliminate the confusion. Many groups had one unexperienced 2nd Lt. in command who had just picked them up the day before. There was a group of 80 officers all _____ aboard who much like the men here were as motley as Joseph’s Coat and had an equivalent record. We found the total officers straight aboard to be 700 including eighty very recently commissioned and very eager nurses. These turned out to be as big a problem the 2nd Lts went after them like hound-dogs after a bitch in heat. I believe most of these girls were actually in heat because it seemed they were very cooperative. Ended up by picking a staff from the staff of the squadron & assigning each squadron officer a job with the men. Had about 150 officers assigned me and to other deck commander and took them down into Compartment Commanders and watch officers so that officer would be with the men 24 hours a day.

Morale for the first four days was the lowest I’ve ever seen it. The confusion was unimaginable. At meal time the corridor looked like 42nd & Broadway on New Year Eve. Only thing that made it satisfactory were boat drills weren’t always went over in first order.

There is a Moving Picture version of a British Colonel aboard as permanent Liaison Officer. Had been troop C.O. for two years aboard same ship. Knows every knook and cranny. Knows every argument that comes up with ships company before it comes up. Without his help this tub would have sunk in this chaos. He is one of the shrewdest men I have ever met & just as humorous. Whenever an argument in Staff Meeting is going the wrong way he can draw a red herring through the conversation so fast that it makes your head swim or tell some fantastic typical statement. “Ships officers are dead from 2 PM til’ four. If you attempted to wake one up the ruddy funnel will fall off.”

Took about seven days to get things afoot so that trip became very pleasant U.S.O. shows helped immensely. Billy Gilbert the Hollywood _____ artist is aboard with a troop and his shows have done wonders for morale. After the first three days the men’s spirits raised and remained amazingly high considering the hardships of sleeping in stinking holds & open but cold decks.

No excitement yet other than an incident the seventh night out. A Swedish ship blasted through the entire convoy at perpendicular courses & all ships had to make a sweeping torn to avoid her she was completely lighted & must have completely silhouetted us also made sub contact at the same time & depth charges were dropped well over the place which sit up a “ruddy din”.

About 1/3 of the men were thoroughly sick the second & third day out when it got fairly rough out water has been like a mild pond ever since.

Units were so spilt up _____ Lord knows how we will debark them. Tuckerman has been made garbage disposal officer and has taken a hell of a beating. Trash & garbage has to be disposed of only at a _____ _____ prior to black out to prevent causing a trail so it’s a hell of a job. Carroll is official announcer on P.A. system and as _____ that an official ____ for everyone aboard when he announces _____ time. Typical crack “Dumping time tonight will be at _ _ o’clock. Stick out your cans for the scrounger man. Tuckerman the garbage man.”

Cards & crap games fill every deck & latrine. Officers and men at it 24 hours a day. One EM cleared $ 1300 one day. Some even have set up boards with numbers on them carnival fashion & have this game in the canteen.

________________________________________

The 55th Fighter Group, the first P-38 equipped 8th Air Force Fighter Group to enter combat with the Luftwaffe, moved to Wormingford, England, on April 16, 1944.

________________________________________

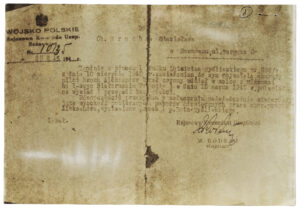

During the 55th’s movement to England Milton managed to send a single V-Mail letter to his parents in Richmond, in which he commented on the hectic nature of the Group’s inter-continental journey, a sea-food dinner in Manhattan, and expressed pride in his wife, Elaine.

In light of Milton’s then as-yet-unknown future, the letter closes with the unintentionally (or not?…) prophetic statement, “It will probably be some time until you hear from me again so don’t worry. This is my real opportunity. Think of it in that light. I’m really on my way home in a way that this is what I had to get under my belt before I could do that.”

Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Joel

Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Joel

1119 Hull Street

Richmond, 21, Va.

Milton Joel, Major AC

38 Fighter Sq 55th Fighter Group

APO #4833 c/o Postmaster New York

Sept. 3, 1943

Dear Folks,

Have been here “somewhere” in New Jersey. Have never had such an exasperating or busy few days in my life. It’s just like recruit camp all over again. Quite an experience. We’ve been held incommunicado so didn’t have time to call anyone in N.Y. Managed to get in one evening long enough for a lobster and a drink. Wonderful to eat Eastern sea food again.

Elaine is in L.A. Got a letter from her yesterday. She’s done a swell job of taking care of our affairs and getting home. Her attitude about this whole thing, I tried to give you a hint about two weeks ago but you couldn’t catch on evidently.

Did Elaine send you some pictures that we took? I’m proud of them particularly the ones taken in the house. Got a swell letter from Elaine’s father. Our two weeks of living together you know showed Elaine to be every thing that I thought her to be plus a great deal.

It will probably be some time until you hear from me again so don’t worry. This is my real opportunity. Think of it in that light. I’m really on my way home in a way that this is what I had to get under my belt before I could do that. Don’t send any thing until I ask for it. Use “V” mail.

Love to all

Milton

________________________________________

This Oogle map below shows the location of Nuthampstead (indicated by Oogle’s emblematic red pointer) in relation to London.

This British Government Royal Ordnance Survey aerial photo shows Nuthampstead Airfield as it appeared on July 9, 1946. Annotations on the photo are from Roger Freeman’s 1978 Airfields Of The Eighth, Then And Now. The original image has been photoshopifically “rotated” from its original orientation such that the north arrow points “up”. As such, the orientation of the airfield is congruent with the area as seen in the contemporary Oogle Earth photo, below.

This British Government Royal Ordnance Survey aerial photo shows Nuthampstead Airfield as it appeared on July 9, 1946. Annotations on the photo are from Roger Freeman’s 1978 Airfields Of The Eighth, Then And Now. The original image has been photoshopifically “rotated” from its original orientation such that the north arrow points “up”. As such, the orientation of the airfield is congruent with the area as seen in the contemporary Oogle Earth photo, below.

Here’s a contemporary Oogle air photo view of the area of Nuthampstead airfield and its surrounding terrain. Practically all the land upon which the air base was situated has been turned over to agricultural use.

Here’s a contemporary Oogle air photo view of the area of Nuthampstead airfield and its surrounding terrain. Practically all the land upon which the air base was situated has been turned over to agricultural use.

________________________________________

________________________________________

Newly arrived at Nuthampstead, the 55th Fighter Group’s Commanders are visited by Major General William E. Kepner (far left), then head of the Eighth Fighter Command.

To General Kepner’s own left in the photo (left to right) are:

To General Kepner’s own left in the photo (left to right) are:

Col. Frank B. James

Lt. Col. Jack S. Jenkins, 0-22606

Major Dallas W. Webb

Major Milton Joel, 0-416308

Major Richard W. (Dick) Busching, 0-427516

Though I don’t recall the specific source of this image as used “here” in this post, this picture can also be viewed at the 55th Fighter Group website. It also appeared in print in the October, 1997, issue of Wings magazine (V 7, N 5, p. 13), where it’s noted as having been part of Jack Jenkins’ photo collection, from which the names above are taken. There, Milton’s name is incorrectly listed as “Walton”. Wings mentions that General Kepner, then in his 50s “…flew his personal P-47D everywhere, including an occasional sortie into combat. Kepner was a strong and successful commander.”

________________________________________

The following Army Air Force photographs, taken some time between the 55th Fighter Group’s arrival at Nuthampstead in September of 1943, and November 29, 1943 (that sad day will be covered in detail in subsequent posts…) may be well known to those with an interest in the history of Eighth Air Force fighter operations, and, the P-38 Lightning. But, for those newly acquainted with this story:

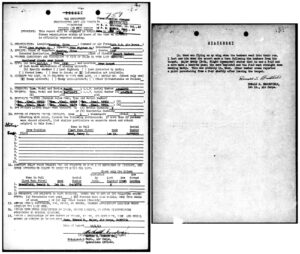

First, image A1 79829 AC / A14144 1A. The photo caption states:

“Flight leaders of the 38th Fighter Squadron, based at Nuthampstead, England, gather for an informal briefing by Major Milton Joel of Richmond, Virginia just before a mission over enemy territory. They are, left to right: 1st Lt. James Hancock of Sebring, Fla., 1st Lt. Gerald Leinweber of Houston, Texas, 1st Lt. Joseph Myers of Canton, Ohio, and 1st Lt. Jerry Ayers of Shelbyville, Tenn.”

Obviously posed (Lt. Ayers and Major Joel have wry smiles) it’s still a great photo. Notice that Lt. Hancock and Major Joel are – gadzooks! – smoking! (In the world of 2020, how … er … uh … um … ironically, dare I say “refreshing ”… as it were?)

Second, image: B1 79830AC / A14145 1A.

Second, image: B1 79830AC / A14145 1A.

The caption?

“Lt. Albert A. Albino of Aberdeen, Wash., and Lt. John J. Carroll of Detroit, Mich., both members of the 38th Fighter Squadron stationed at Nuthampstead, England, discuss the map of a future target in the squadron pilot room.”

Like the above image, this photo is almost certainly posed, but it’s still an excellent study. While Lt. Albino wears a classic leather flight jacket, it looks as if Lt. Carroll sports a home-made (?) sweater.

By day’s end on November 29, 1943, Lt. Albino would no longer be among the living, and Lt. Carroll would be a prisoner of war.

________________________________________

________________________________________

After Major Joel failed to return from the mission of November 29, Captain Mark K. Shipman of Fresno, California, took command of the 38th, until replaced in that role by Capt. Joseph Myers.

The below portrait of Major Shipman (long before he became a Major!) is from the United States National Archives’ collection “Photographic Prints of Air Cadets and Officers, Air Crew, and Notables in the History of Aviation”, in NARA Records Group 18-PU, which also includes (see prior post) a Flying Cadet portrait of Major Joel. Major Shipman’s photo is from Box 84 of the collection. You can read about the collection at The Past Presented.

This image, from The American Air Museum in Britain, shows Captain Shipman in front of his personal P-38, 42-67080, “Skylark IV”, “CG * S”. This photograph appears on page 93 of Roger Freeman’s The Mighty Eighth, albeit in cropped form, and transposed (a mirror-image) from the actual print. Major Shipman was officially credited with 2.5 aerial victories: One in North Africa, and two in Europe.

This image, from The American Air Museum in Britain, shows Captain Shipman in front of his personal P-38, 42-67080, “Skylark IV”, “CG * S”. This photograph appears on page 93 of Roger Freeman’s The Mighty Eighth, albeit in cropped form, and transposed (a mirror-image) from the actual print. Major Shipman was officially credited with 2.5 aerial victories: One in North Africa, and two in Europe.

This image of the aircraft and ground crew was photographed by Sgt. Robert T. Sand, who not-so-coincidentally completed Skylark IV’s nose art. Note that the 20mm cannon has been removed from the plane’s nose.

This image of the aircraft and ground crew was photographed by Sgt. Robert T. Sand, who not-so-coincidentally completed Skylark IV’s nose art. Note that the 20mm cannon has been removed from the plane’s nose.

The below article about Major Shipman appeared in the Pittsburgh Press on February 6, 1943, and pertains to his experience on January 23, 1943, while he was serving as a lieutenant in the 48th Fighter Squadron of the 14th Fighter Group. Accounts of this mission, in which the 48th lost six pilots – of whom Lt. Shipman turned out to be the sole survivor – can be found at emedals.com and Rob Brown’s RAF 112 Squadron.org.

The below article about Major Shipman appeared in the Pittsburgh Press on February 6, 1943, and pertains to his experience on January 23, 1943, while he was serving as a lieutenant in the 48th Fighter Squadron of the 14th Fighter Group. Accounts of this mission, in which the 48th lost six pilots – of whom Lt. Shipman turned out to be the sole survivor – can be found at emedals.com and Rob Brown’s RAF 112 Squadron.org.

U.S. Flier Walks 2 Days Through Italian Positions

Pilot’s Clothes Stolen, So He Wraps Feet in Rags; Brings Back Valuable Information

By the United Press

ALLIED HEADQUARTERS, North Africa. Feb. 6 – For two days Lt. Mark K. Shipman, 22, Fresno, Cal., wandered over desert and mountains, his feet bound with shreds of his uniform, but when he finally reached an American outpost he brought with him valuable reconnaissance information.

The lieutenant told about his experience today.

His Lightning fighter plane was shot down on the morning of Jan 23 when he left formation to help a comrade fighting a cluster of Messerschmitts. Lieut. Shipman said he made a belly landing.

“The ship was practically undamaged,” he said. “I ran about 40 yards away because I knew the Messerschmitts would strafe me. Three of them riddled the plane with three dives. Then I went back to it and took out a helmet, canteen and pistol and started hiking for the mountains.”

Clothes Stolen

Lieut. Shipman said all his clothes except his trousers and undershirt were stolen from him, although he managed to retain a wedding ring and Crucifix which were presents from his wife. (The dispatch did not say who did the looting.)

“I found I couldn’t walk in my bare feet,” Lieut. Shipman continued. “So I cut off my trousers below the knees and wrapped the cloth around my feet. I walked over a mountain knowing by the sun I was traveling toward the American lines. I found a narrow dirt road and started making better time but my feet were getting sore.

Fixes Crude Bed

“So I took off mv trousers and managed to cut off more cloth above the knees, which I added to the strips I already had tied about, my feet. I turned off the trail and went over to a creek bed and fixed a crude bed in a hole. I got kind of warm and rested.

“After a while the moon came up and I got out and started down the creek bed. About 10 o’clock I passed what I believed were some Italian tents and snaked along silently, finally getting into the open.

“I ran along a dirt road for a while and was hiding in a ditch when a motorcyclist came along. He was Italian. I decided it was safer to keep off the road. My feet were so sore I could scarcely stand so I made a sort of fox hole about a hundred yards from the road.

Crosses Road

“When daylight came I positively identified other passing vehicles as Italian. I crossed the road and crept along, finally reaching three Italian road blocks. I took off my white cotton undershirt so I wouldn’t be conspicuous.

“By that time I was getting desperate and I decided on a break. I got into ravines and at times I saw Italian sentries on both sides. After I sneaked along for about five miles I didn’t see any more Italians. About 5 p.m. I approached an American outpost. They recognized me.”

________________________________________

Capt. Joseph Myers, Jr. and Major Joel stand before a P-38. The date and location of the image are unknown. Thanks to information from Andrew Garcia in November of 2023, I’ve been able to correlate the four-digit Lockheed Aircraft Company factory production number “1526” on the fighter’s nose to its Army Air Force serial: The aircraft is P-38H 42-67015. Being that this aircraft isn’t listed at the Aviation Archeology database and there is no Missing Air Crew Report for it, it seems that it survived the war, I assume to be turned into aluminum siding or pots & pans after 1945. (Photo c/o Harold Winston)

Another image of Capt. Myers, this time in front of his personal aircraft, P-38J 42-67685 “Journey’s End’ / “CG * O”, with ground crew members Sergeants K.P. Bartozeck and J. D. “Dee Dee” Durnin. The image presumably dates from very late 1943, as “Journey’s End” was destroyed during a single-engine crash-landing on January 4, 1944.

Another image of Capt. Myers, this time in front of his personal aircraft, P-38J 42-67685 “Journey’s End’ / “CG * O”, with ground crew members Sergeants K.P. Bartozeck and J. D. “Dee Dee” Durnin. The image presumably dates from very late 1943, as “Journey’s End” was destroyed during a single-engine crash-landing on January 4, 1944.

This image, from The American Air Museum in Britain, can also be found on page 93 of Roger Freeman’s The Mighty Eighth.

This image shows Lt. Col. Joseph Myers, seated in a P-51D Mustang, to which the 55th Fighter Group began converting in July, 1944. He commanded the 38th Fighter Squadron between February 10 and April 22 of that year. This image is from the collection of Dave Jewell.

This image shows Lt. Col. Joseph Myers, seated in a P-51D Mustang, to which the 55th Fighter Group began converting in July, 1944. He commanded the 38th Fighter Squadron between February 10 and April 22 of that year. This image is from the collection of Dave Jewell.

________________________________________

________________________________________

Another pilot whose P-38 sports distinctive nose art: Capt. Jerry H. Ayers and ground crew in front of his personal aircraft, P-38J 42-67077, “Mountain Ayers” / “CG * Q”. Like many examples of 55th Fighter Group nose art, this painting was completed by Sergeant Robert T. Sand.

Just One Reference!

Maloney, Edwatd T., Lockheed P-38 “Lightning”, Aero Publishers, Inc., Fallbrook, Ca., 1968 (The book includes a table correlating Lockheed Aircraft Company serials to Army Air Force serials.)

Next: Part IV (1) – Autumn Over Europe

11/13/20 – 1,634